-

Figure 1.

The interactions in plant-based food systems. This figure illustrates the interactions formed between plant macromolecules through adsorption, migration, solubilization, and oxidation reactions during plant tissue processing treatments. Case 1 reveals the release of polyphenols from plant tissues and into beverages during the production of wines and juices, a process significantly influenced by the degree of polyphenols binding to the cell wall. Case 2 describes the interaction between procyanidins and cell walls, a key phenomenon that leads to pink discoloration in the canning of pear slices. Case 3 shows how salivary proteins are involved in the interaction of macromolecules in food during oral mastication. Case 4 illustrates the process of food in the digestive system and the interaction between polyphenols and gut microorganisms. The bottom of the figure shows the food sources, processing history, and applications of plant macromolecule interactions in food and how these macromolecules relate to regulating the gut microbial community.

-

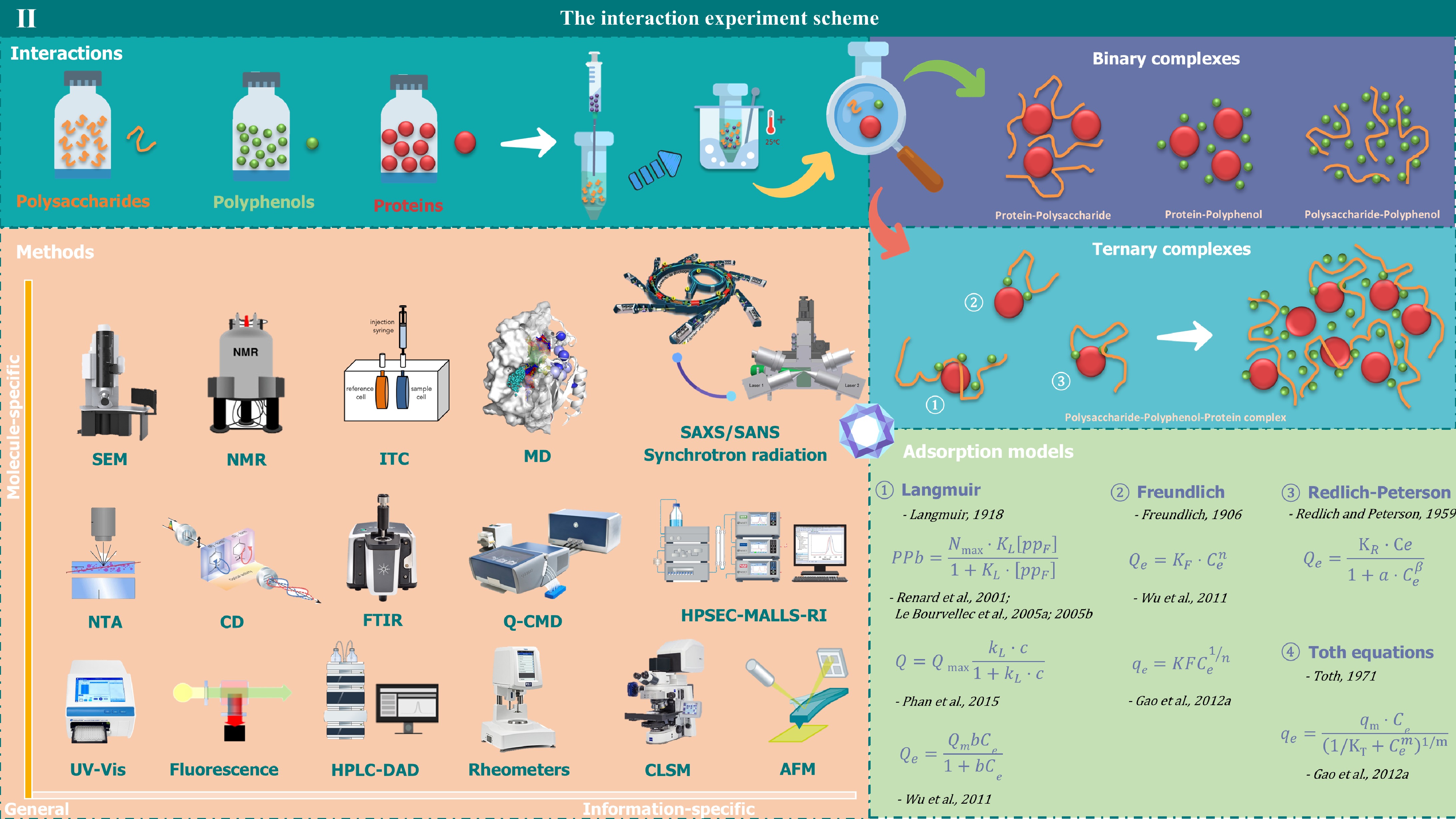

Figure 2.

The interaction experiment scheme. Under specific conditions, polysaccharides, polyphenols, and proteins can interact with each other to form binary or ternary complexes. In the initial state, these molecules exist as separate entities in solution. However upon mixing, they spontaneously interact and form complexes. After being heated in a water bath and with adjustments to environmental factors, these complexes can further interact with surrounding components, thereby constructing a complex and well-structured system. The figure displays the measurement methods for their interactions and the adsorption models. Interactions are measured by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), Molecular Dynamics (MD), Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), Circular Dichroism (CD), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation Monitoring (Q-CMD), Ultraviolet-visible Spectroscopy (UV), Fluorescence Spectroscopy, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection (HPLC-DAD), Rheological Measurement Instruments, Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM), Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), Small Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS), Small Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS) and High-Performance Size-Exclusion Chromatography combined with Multi-Angle Laser Light Scattering (HPSEC-MALLS-RI) and Refractive Index detection. The adsorption models have Langmuir, Freundlich, Redlich-Peterson, and Toth equations.

-

Figure 3.

The proposed interaction mechanisms. Case 1 describes a non-covalent interaction between polysaccharide and polyphenol. Common non-covalent forces include hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and van der Waals forces. Non-covalent interactions lead to three possible consequences: maintaining a non-aggregated and soluble state, formation of aggregates leading to turbidity, and formation of insoluble precipitates. Case 2 describes a covalent interaction between polysaccharide and protein. The Maillard reaction, chemical cross-linking, and enzymatic covalent binding are the primary factors that determine covalent bonding between polysaccharides and proteins. This figure depicts the effect of thermodynamic quantization ((ΔH) and (ΔS)) on the interaction, and also depicts the physical constraints that act as regulators of interactions. Porosity and pore morphology have a major impact on macromolecular interactions in plants.

-

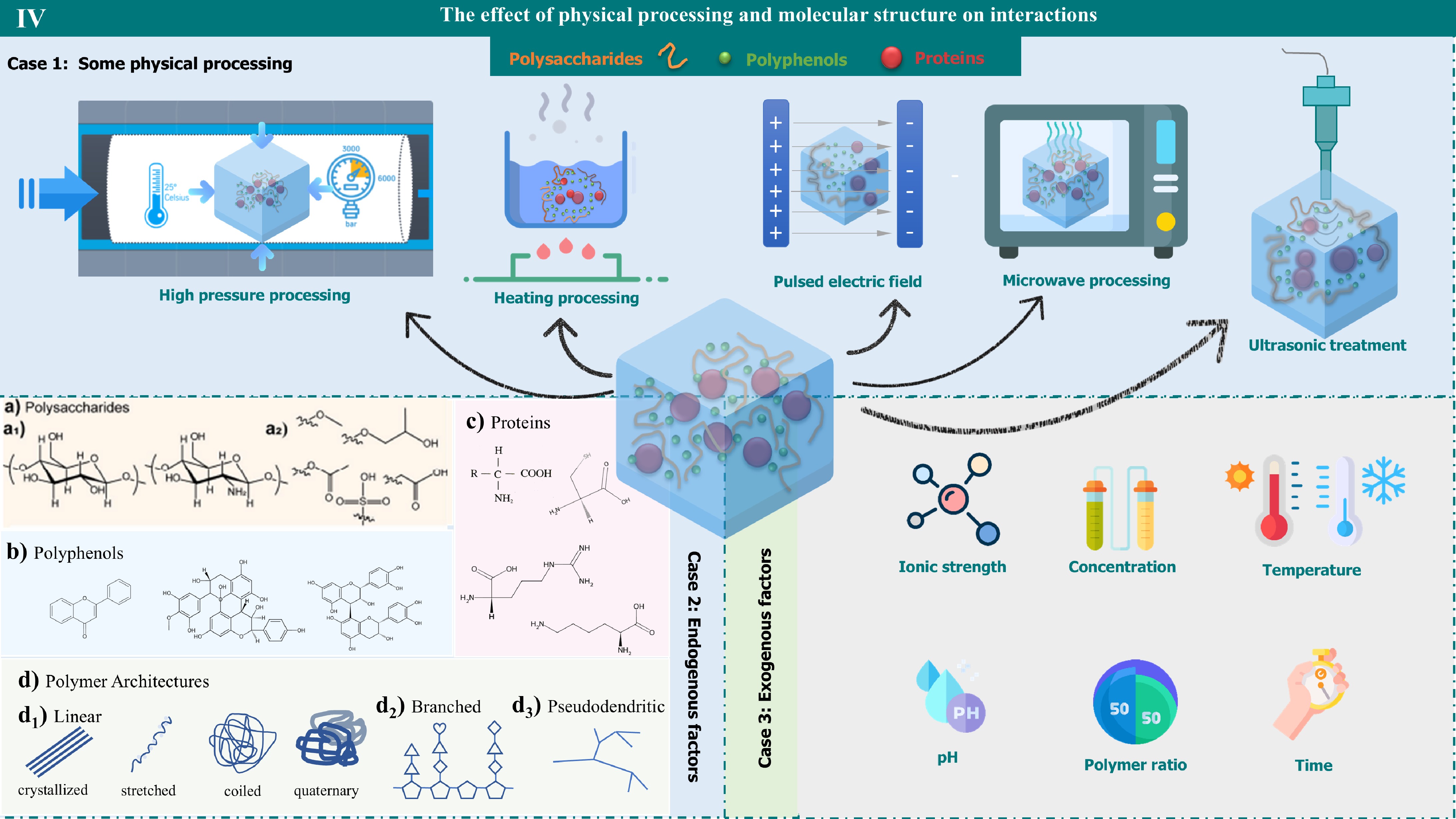

Figure 4.

The effect of physical processing and molecular structure on interactions. It reveals how the physical treatment steps and molecular structure affect the interactions. A variety of physical treatment techniques, including high-pressure, heating, pulsed-electric fields, microwaves, and ultrasound, are demonstrated. In addition, the role of molecular structure in interactions can be divided into two main categories: endogenous and exogenous. Endogenous factors involve the structural properties of polysaccharides, polyphenols, proteins, and polymer architectures, while exogenous factors include the effects of ionic strength, concentration, temperature, pH, polymer ratio, and time.

-

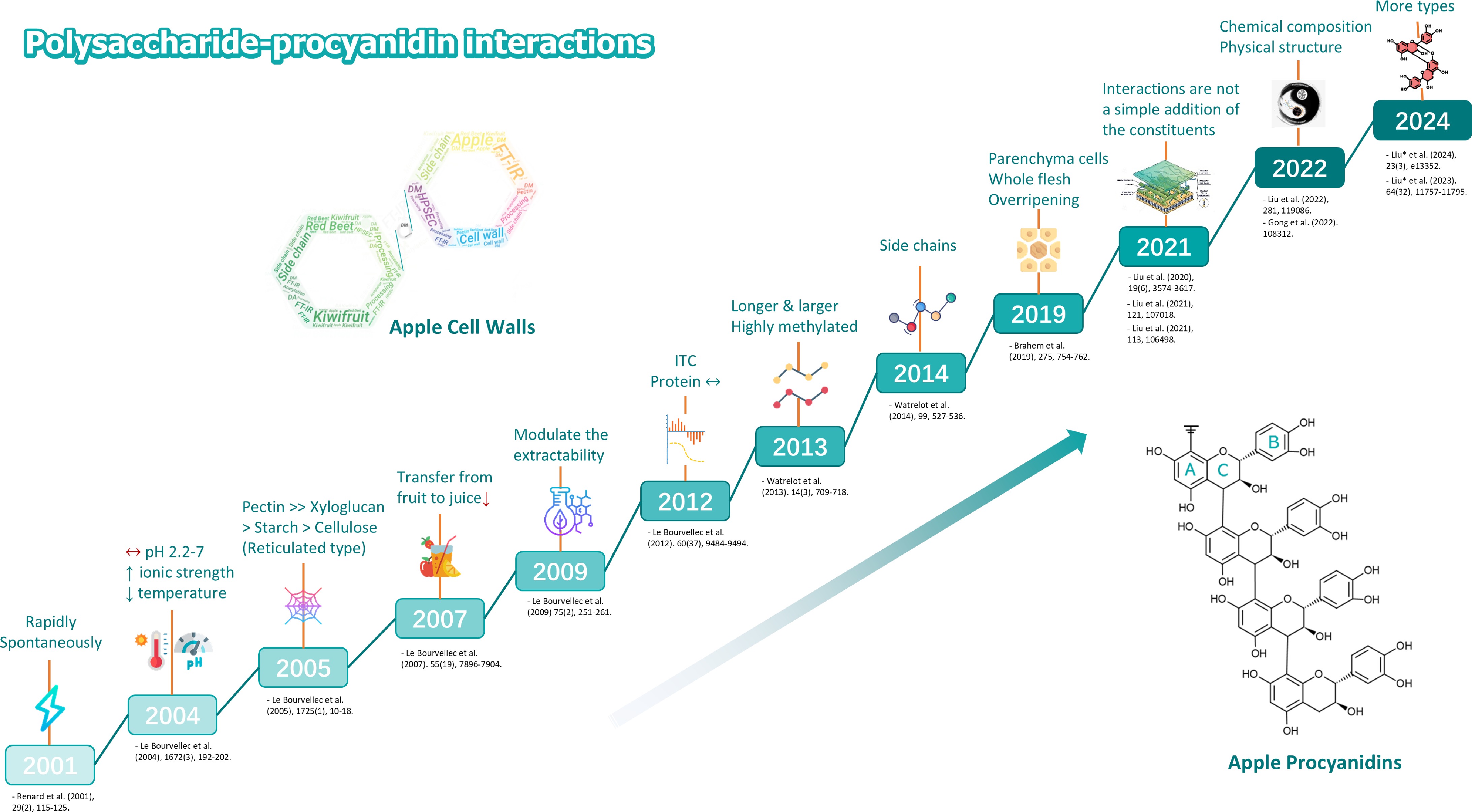

Figure 5.

As an example: Cell wall polysaccharide-procyanidin interactions. At beginning study by Renard et al.[51], the apple cell walls experiences immediate and automatic attachment to procyanidins originating from apples. Le Bourvellec et al.[13] explained that environmental factors (pH, ionic strength, temperature) affect the non-covalent interactions between procyanidins and apple cell walls. Le Bourvellec et al.[58] studied the adsorption of procyanidins on cell walls, taking into account the effects of polymerization degree. Le Bourvellec et al.[43] explored the interaction between apple procyanidins and cell walls and its role in the transformation from the fruit state to the juice phase. Le Bourvellec et al.[188] identified that the interaction of procyanidins with the cell walls influences the yield of polysaccharide extraction. Le Bourvellec et al.[189] examined how the cell wall composition and structure of apples influence the binding of procyanidins. Watrelot et al.[190] examined the interaction between procyanidins and pectin using isothermal titration calorimetry and turbidity analysis, focusing on the impact of pectin methylation and side chain length. Watrelot et al.[191] revealed that the binding of procyanidins to pectin's hairy regions depends on the neutral sugar side chains' makeup and structure. Brahem et al.[192] investigated that maturity and tissue type of pear pulp affects procyanidin-cell wall interactions, with higher adsorption of highly polymerized procyanidins by overripe pulp cell walls. Liu et al.[136] was conducted to evaluate the interaction properties between xylose-containing hemicelluloses and procyanidins. Liu et al.[193] investigated that the total interactions are not a simple summation of different component interactions. Physical factors are as important as chemical ones for interaction[193]. They[194,195] also summarize the physicochemical and structural changes of A-type proanthocyanidins during extraction, processing and storage. Future work would be devoted to the interaction between more types of polysaccharides and polyphenols.

Figures

(5)

Tables

(0)