-

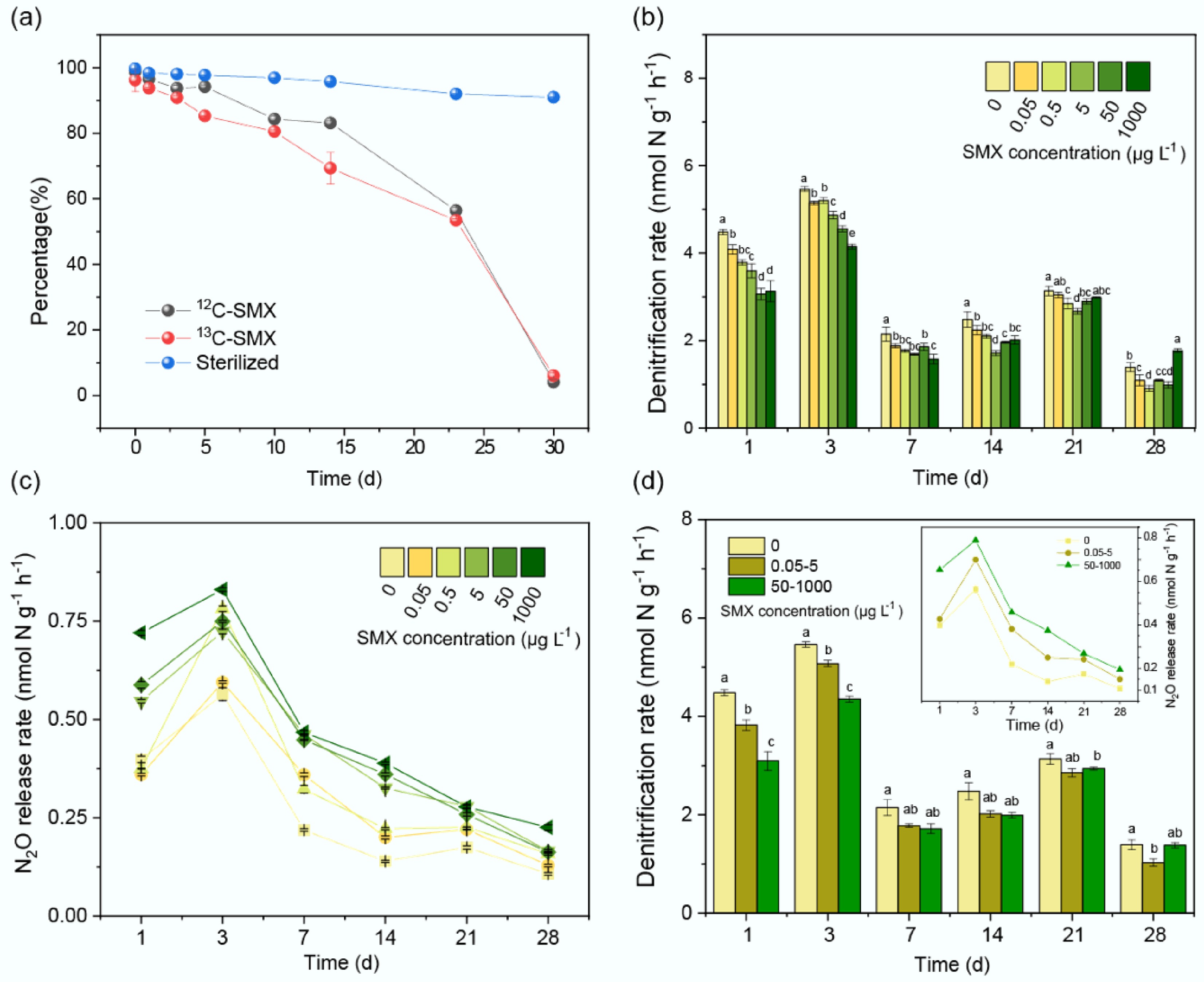

Figure 1.

Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) degradation dynamics and effects on denitrification and N2O emissions. (a) Degradation of 13C- and 12C-SMX in active vs sterilized sediments over 30 d. Time-course changes in (b) denitrification rates, and (c) N2O release under SMX gradients (0–1,000 μg L−1). (d) Time-course changes in denitrification rates and N2O release among blank (0), environmental concentrations (0.05–5 μg L−1), and therapeutic concentrations (50–1,000 μg L−1). Error bars represent standard deviations (n = 3). Lowercase letters denote significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05).

-

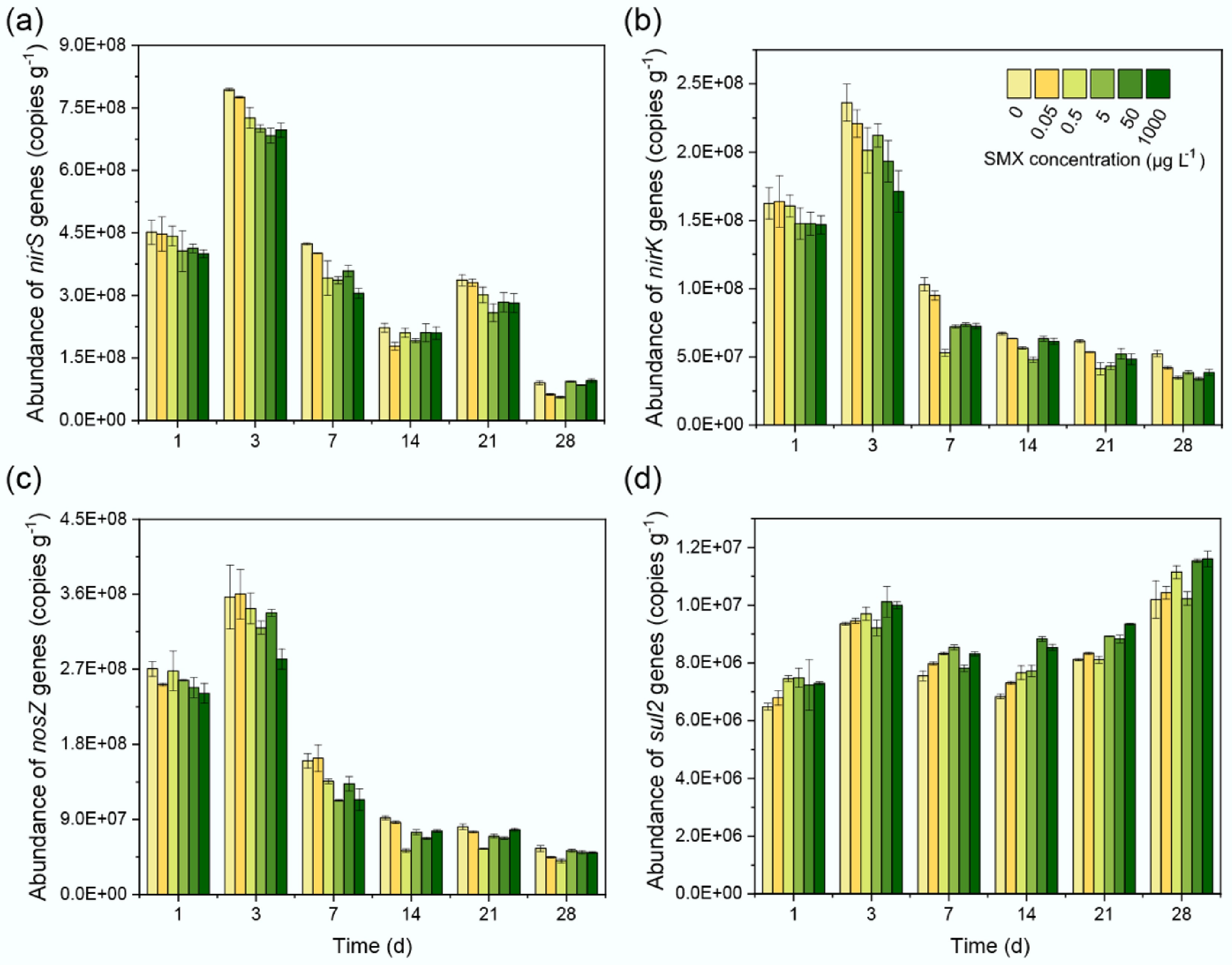

Figure 2.

SMX effects on denitrification and sulfonamide resistance gene abundances. Temporal changes in (a) nirS, (b) nirK, (c) nosZ, and (d) sul2 gene copy numbers across SMX concentrations (0–1,000 μg L−1). Error bars represent standard deviations (n = 3). Lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

-

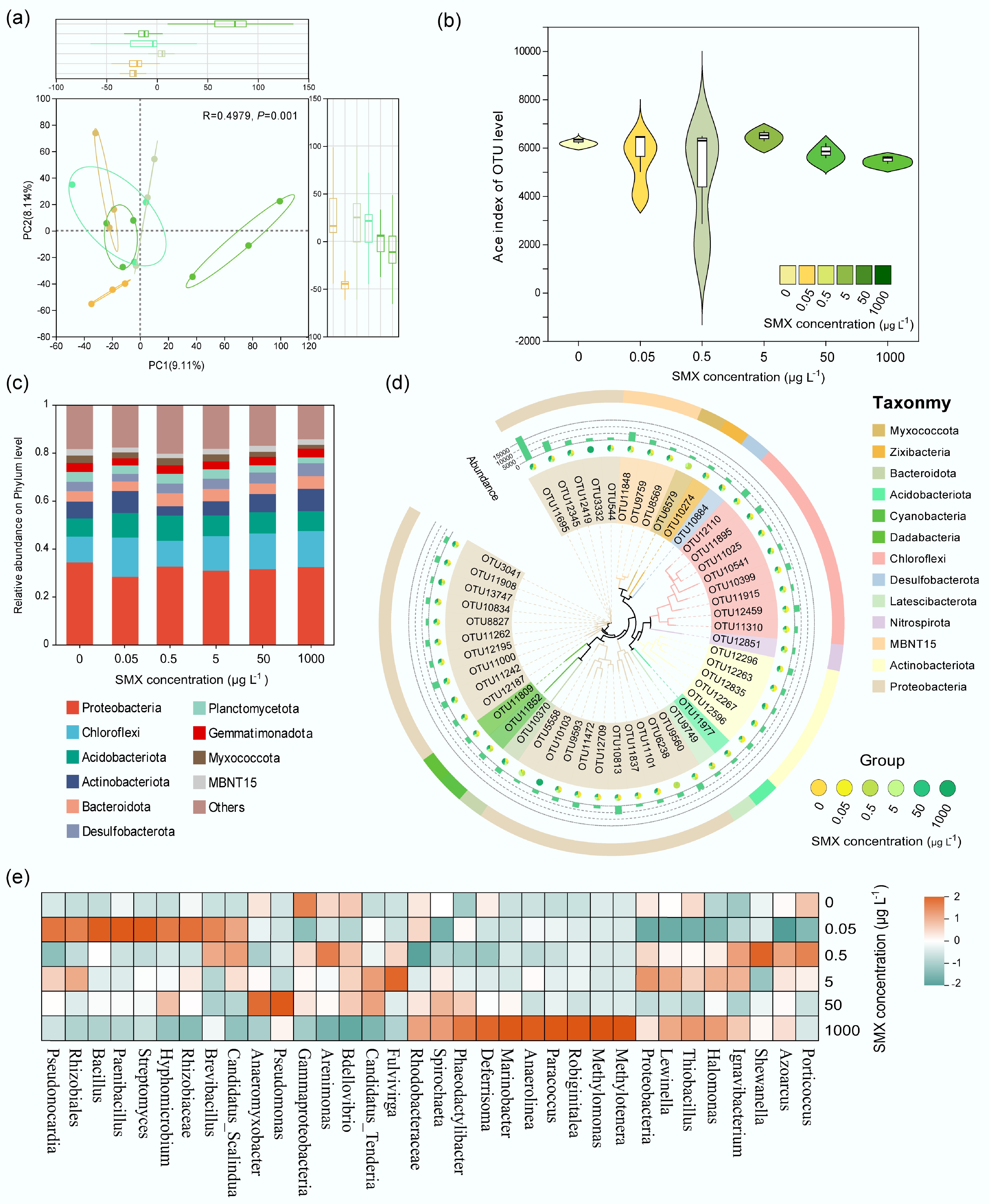

Figure 3.

SMX-driven shifts in sediment bacterial communities. (a) PCoA (Bray-Curtis) showing community separation by SMX (PERMANOVA, R = 0.4979, p = 0.001). (b) ACE index (richness) response to SMX concentration. (c) Phylum-level composition highlighting Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Chloroflexi. (d) Phylogenetic cladogram of SMX-sensitive OTUs (LEfSe; p < 0.05). (e) Heatmap of SMX-responsive genera; color = log-fold change vs control.

-

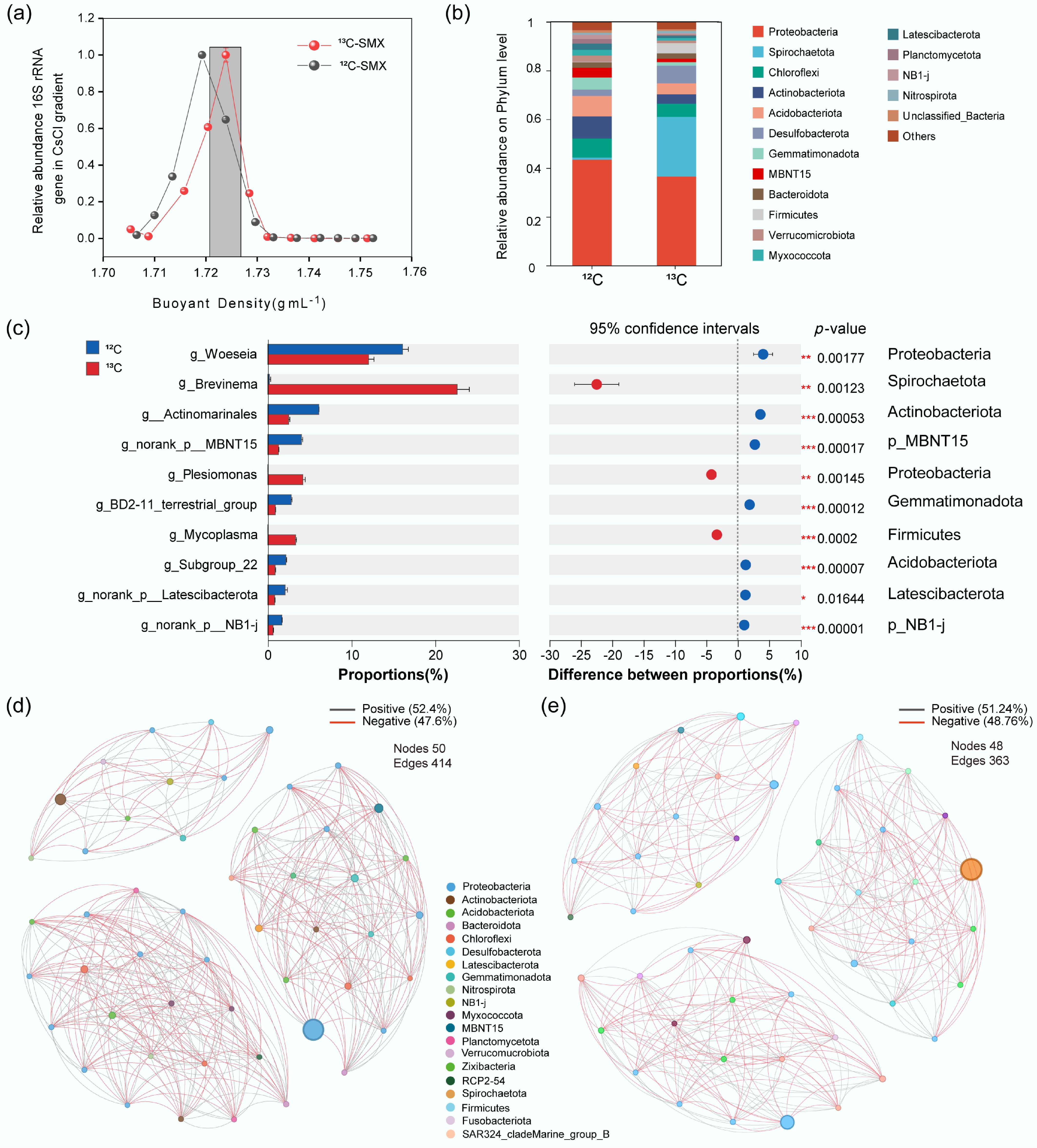

Figure 4.

Active SMX-assimilating taxa and microbial interactions identified by DNA-SIP. (a) Relative abundance of 16S rRNA gene in CsCl density fractions (13C- vs 12C-SMX). (b) Phylum composition of 13C- and 12C-labeled DNA. (c) Differentially enriched genera and phyla in 13C-DNA; bars = mean abundance, diamonds = proportional difference (*** p < 0.001). Co-occurrence networks for (d) 12C-, and (e) 13C-communities. Nodes: taxa (phylum-colored); edges: positive (gray)/negative (red) correlations.

-

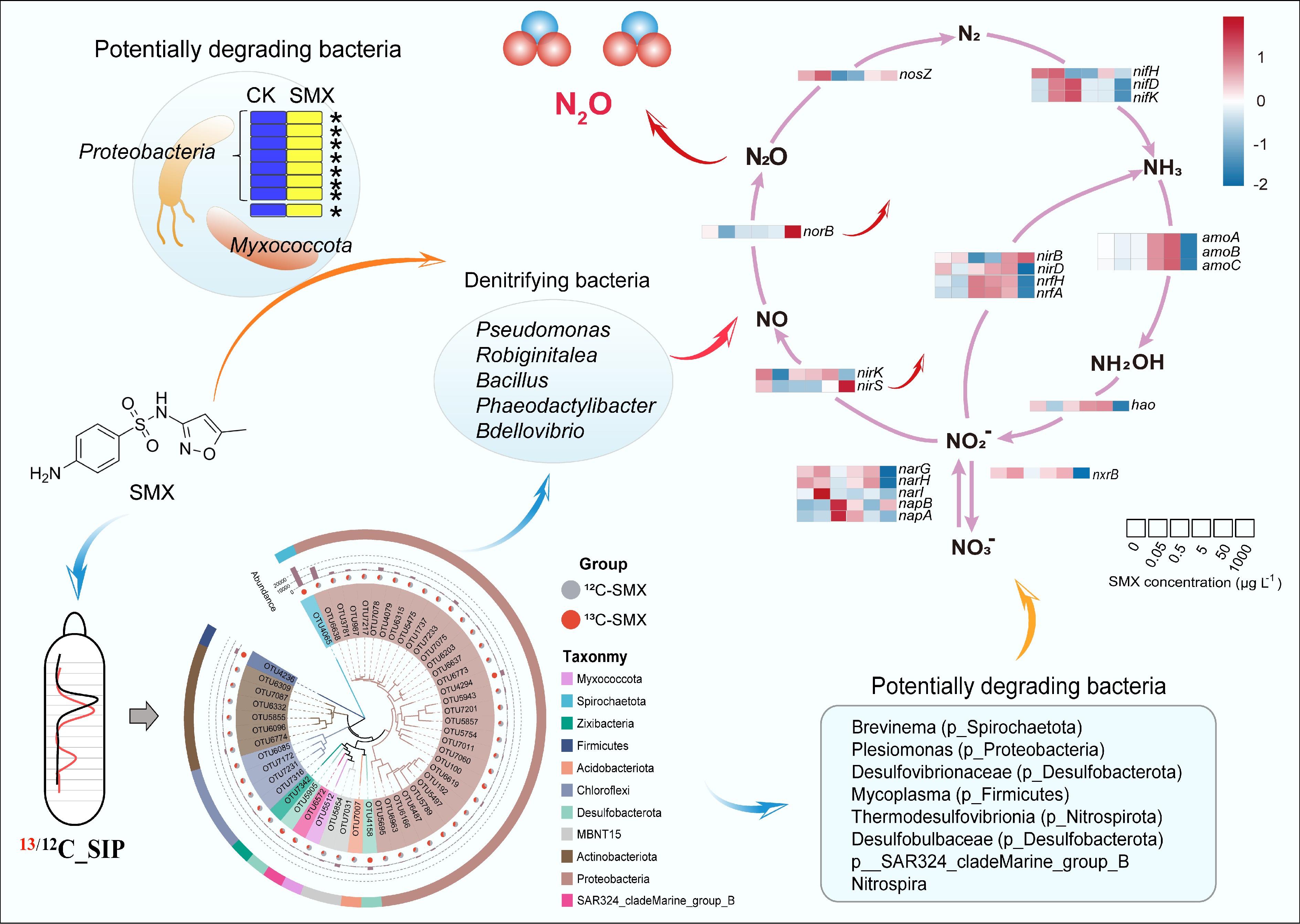

Figure 5.

Mechanistic link between active SMX-degrading bacteria and denitrification. (Center) DNA-based stable isotope probing (DNA-SIP) with 13C-SMX identified denitrifying bacteria (Pseudomonas, Bacillus, Bdellovibrio) as primary assimilators of the antibiotic. (Upper left) Dominant bacterial phyla responsible for SMX assimilation (Proteobacteria, Myxococcota). (Bottom center) Phylogenetic distribution of 13C-enriched operational taxonomic units (OTUs), highlighting additional key degraders (Spirochaetota, Desulfobacterota). (Right) Heatmap showing SMX concentration-dependent responses of key nitrogen (N) cycling genes, linking antibiotic stress to disrupted N-cycling pathways. The genes analyzed include those for nitrogen fixation (nif, nitrogenase), which converts dinitrogen gas to ammonia; nitrification (amo, ammonia monooxygenase; hao, hydroxylamine oxidoreductase; nxr, nitrite oxidoreductase), which oxidizes ammonia to nitrate; the complete denitrification pathway (nar, nitrate reductase; nirK/nirS, nitrite reductase; norB, nitric oxide reductase; nosZ, nitrous oxide reductase), which reduces nitrate to dinitrogen gas; dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) (nrfA/H, cytochrome c nitrite reductase complex), which reduces nitrite to ammonia; and assimilatory nitrate reduction (nirB/D, assimilatory nitrite reductase), which incorporates nitrogen into biomass.

Figures

(5)

Tables

(0)