-

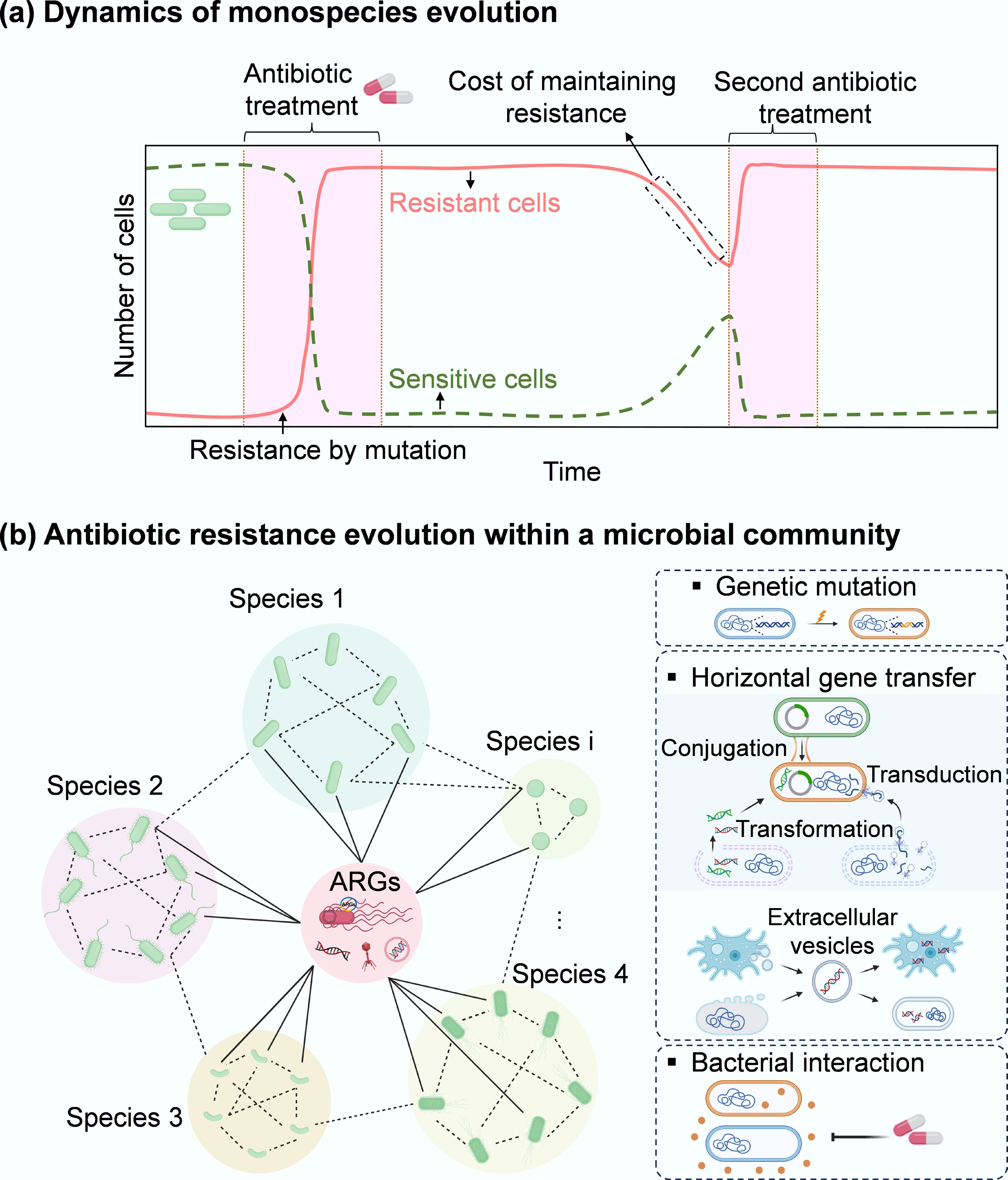

Figure 1.

Microbial evolution dynamics. (a) Temporal dynamics of external stressor(s) exposure and antibiotic resistance in monospecies or individuals. When exposed to stressors such as antibiotics, the dominant susceptible cells are rapidly removed, while a small number of sensitive cells can acquire antibiotic resistance via genetic mutations. Upon ceasing the selective stress, sensitive cells can recover to a peak. Some resistant cells can become sensitive due to the fitness cost associated with the acquired resistance. This cost can be offset by re-exposing to antibiotics, inducing compensatory mutations, or typically selecting for a resistant cell as the dominant population. In contrast, sensitive strains show an opposite evolutionary pattern. (b) Antibiotic resistance evolution within a microbial community comprising diverse bacterial species and their protist predators (e.g., amoebas). Here, three representative pathways (mutation, HGT, and inter-species interactions) for the evolution of antibiotic resistance in a microbial community are presented. Under antibiotic exposure, sensitive species (green) in a microbial community can develop antibiotic resistance via more diverse strategies, including HGT and inter-species interactions, that do not occur in monospecies. Through HGT, the pre-existing resistant bacteria (red) can share ARGs with different phylogenetic species. Free and mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including plasmids, transposons, integrons, insertion sequences, and phages that encode ARGs, can also be taken up by different members of the community. Extracellular vesicles produced from a range of community members (bacterial species and their predators) package their parental DNA (vesicular DNA) and can also contribute to horizontal transfer of vesicular ARGs within the bacterial kingdom or even between bacterial species and their protists (across the kingdom). In addition, interspecies interactions can shape the pattern of antibiotic resistance within microbial communities through co-resistance, cross-resistance, and co-regulation. For example, some sensitive species may survive antibiotics through interactions with resistant bacteria that can detoxify antibiotics.

-

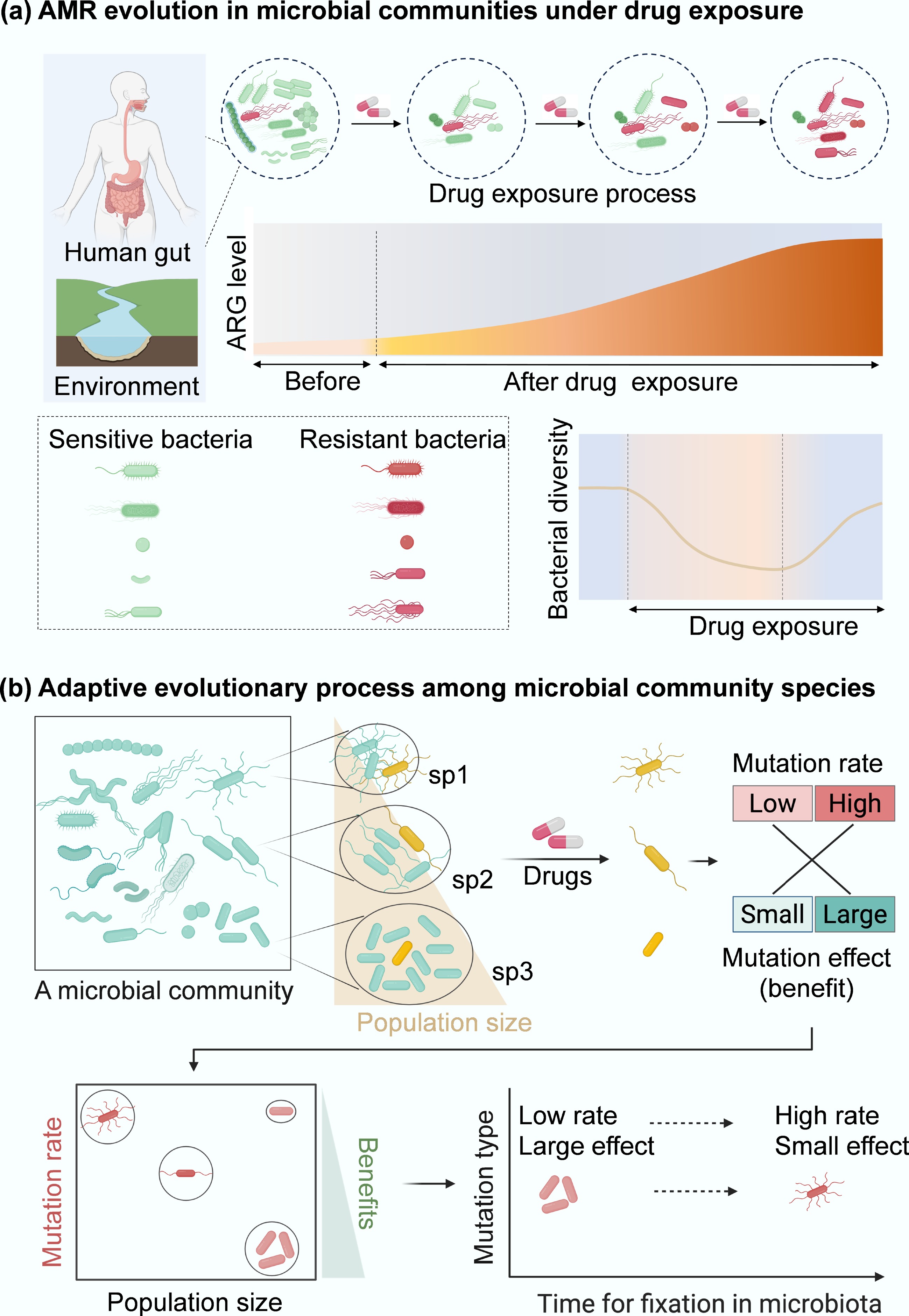

Figure 2.

Resistance evolution of microbial community. (a) Conceptual diagram of how antibiotic exposure shapes human gut and environment microbiota and ARG profiles (red curve area). (b) Evolution paths of antibiotic resistance within microbial communities. Persisters (e.g., cells from different species, sp1, sp2, and sp3; in yellow) spontaneously occur at low frequencies in microbial communities. In communities composed of diverse species with different population sizes, the evolution of resistance becomes more complicated under drug exposure. Compared to monospecies[54], more persisters from different genotypes within a microbial community can be selected by drugs, which can subsequently induce genetic mutations (cells in red). These mutations can be grouped into low- or high-rate categories with minor or significant effects. In species with sp3, where population sizes are relatively large, large-effect mutations can be dominant because small-effect mutations are filtered out by clonal interference. In contrast, in a small population, high-rate and small-effect mutations are more likely to establish. Therefore, the low-rate, large-effect beneficial mutations from sp3 can be more easily fixed in microbial communities than mutations from other species populations (sp1, sp2). These mutations drive bacterial adaptive evolution and will promote the development of antibiotic resistance within a microbial community.

-

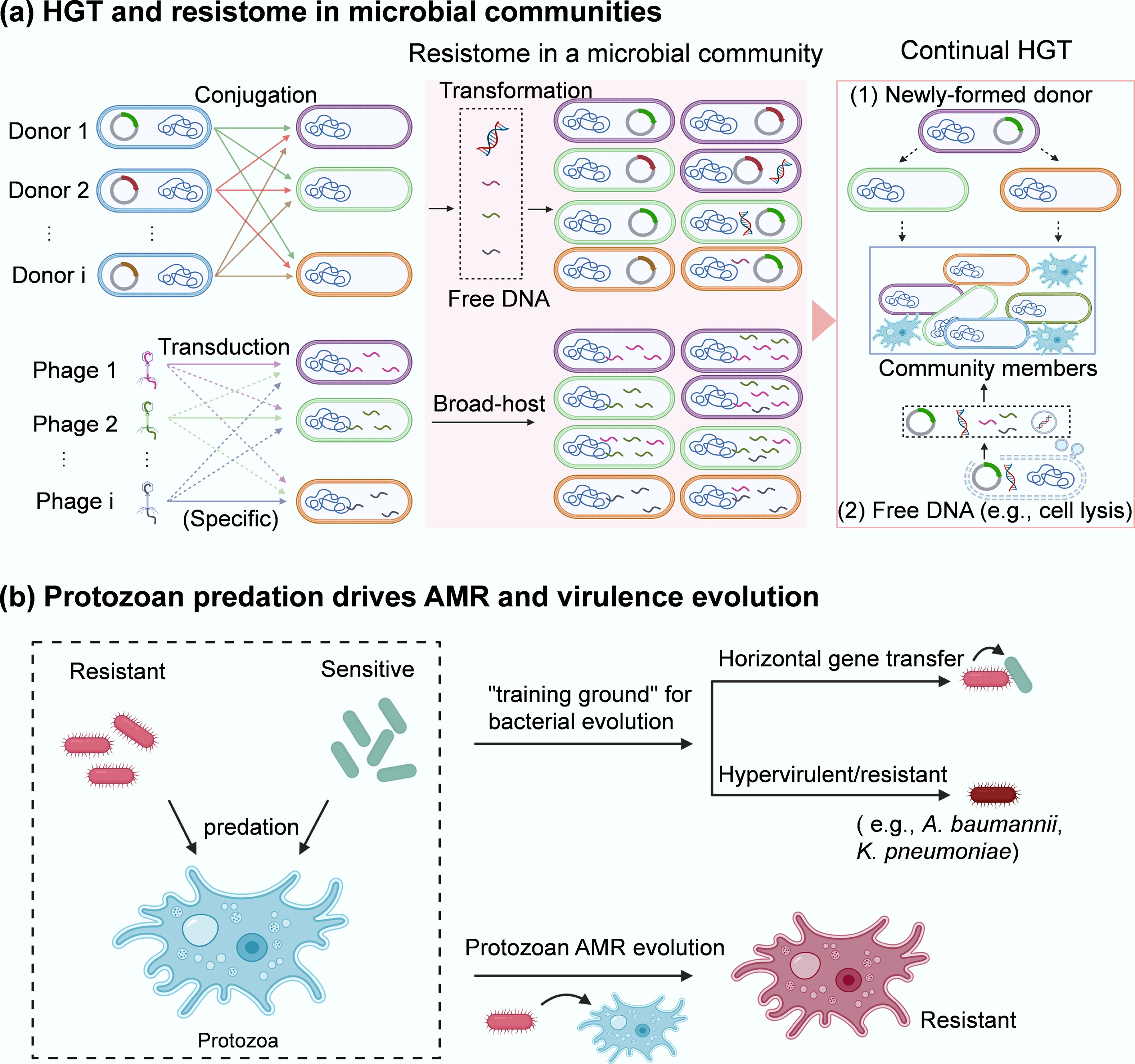

Figure 3.

AMR transmission in microbial communities. (a) HGT and resistome in a microbial community. Three key pathways of HGT (conjugation, transformation, and transduction) occur among different community members. The broad-host range plasmid-bearing bacterial species (i.e., Donor 1, Donor 2, …, Donor i that contain different plasmids or are different species can deliver plasmid-encoded ARGs via conjugation (1st) to the neighbours within a microbial community. Some of them may also take up free DNA (encoding ARGs) released from resistant bacteria via transformation or vesicle-mediated transfer. In addition, there are various types of phages (i.e., Phage 1, Phage 2, …, Phage i) that are either specific or nonspecific (broad-host range) to the target bacteria within a microbial community. These phages can serve as shuttles to transport ARGs across species via transduction, thereby enriching the resistome (red area) in the community. The second, more widespread transfer (via conjugation, transformation, transduction, and vesicle-mediated spread) of ARGs from newly formed donors or lysed cells to other members can further facilitate their spread within microbial communities. (b) Protozoan predation drives the evolution of AMR in both encapsulated bacteria and the host.

-

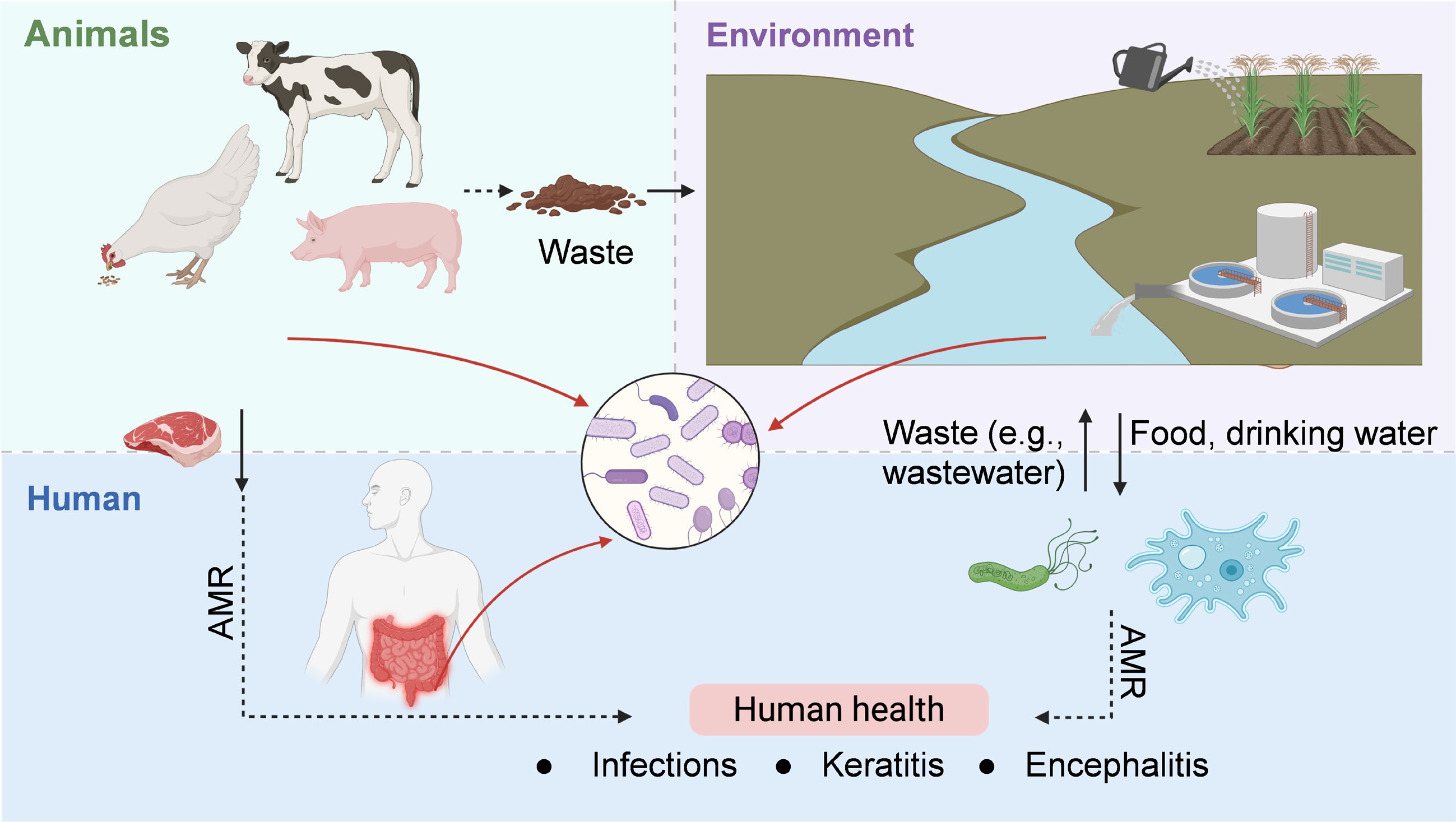

Figure 4.

Health implications of AMR evolution in microbial communities, framed within the One Health paradigm.

Figures

(4)

Tables

(0)