-

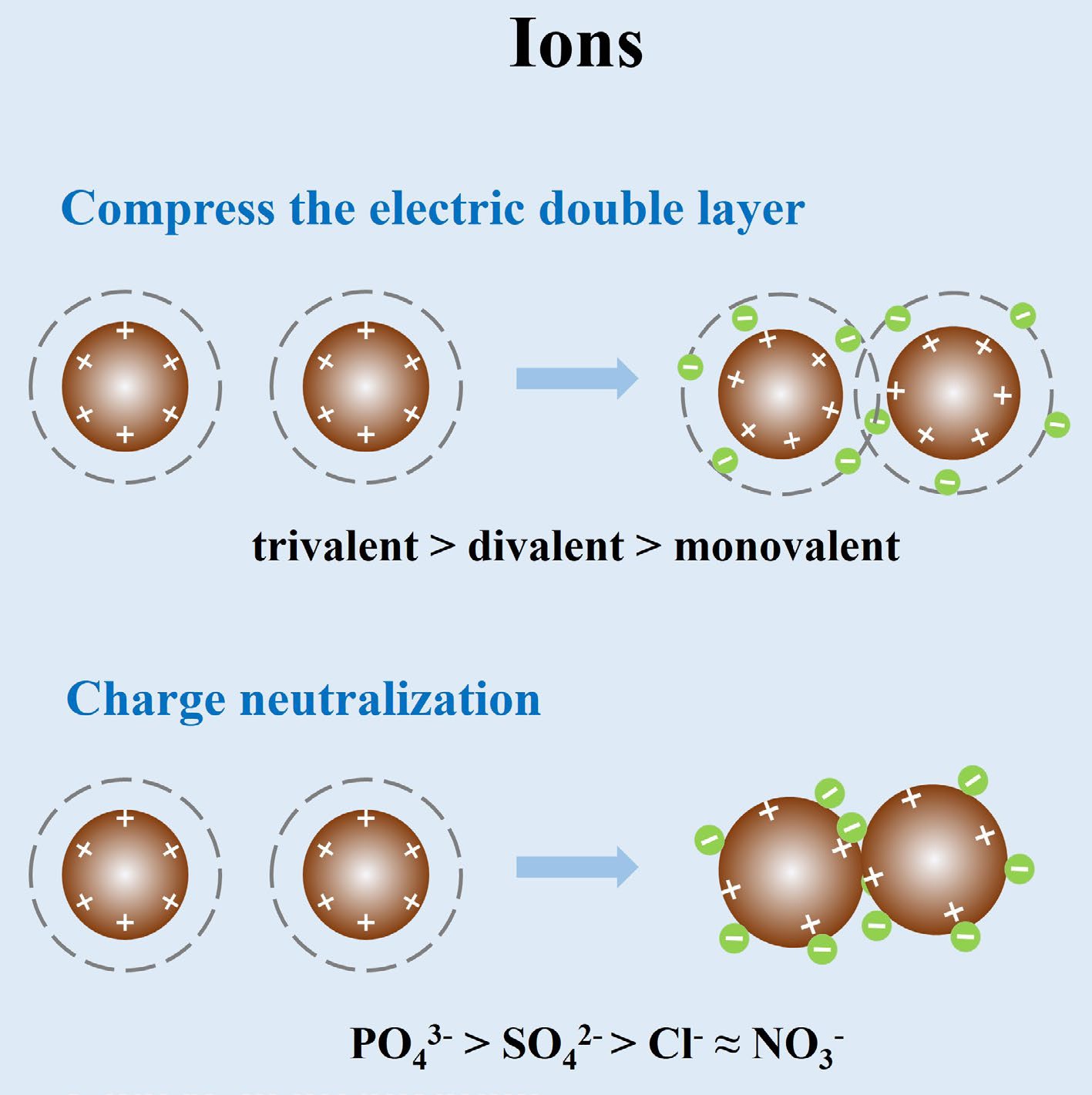

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the mechanisms by which metal ions influence IONPs aggregation.

-

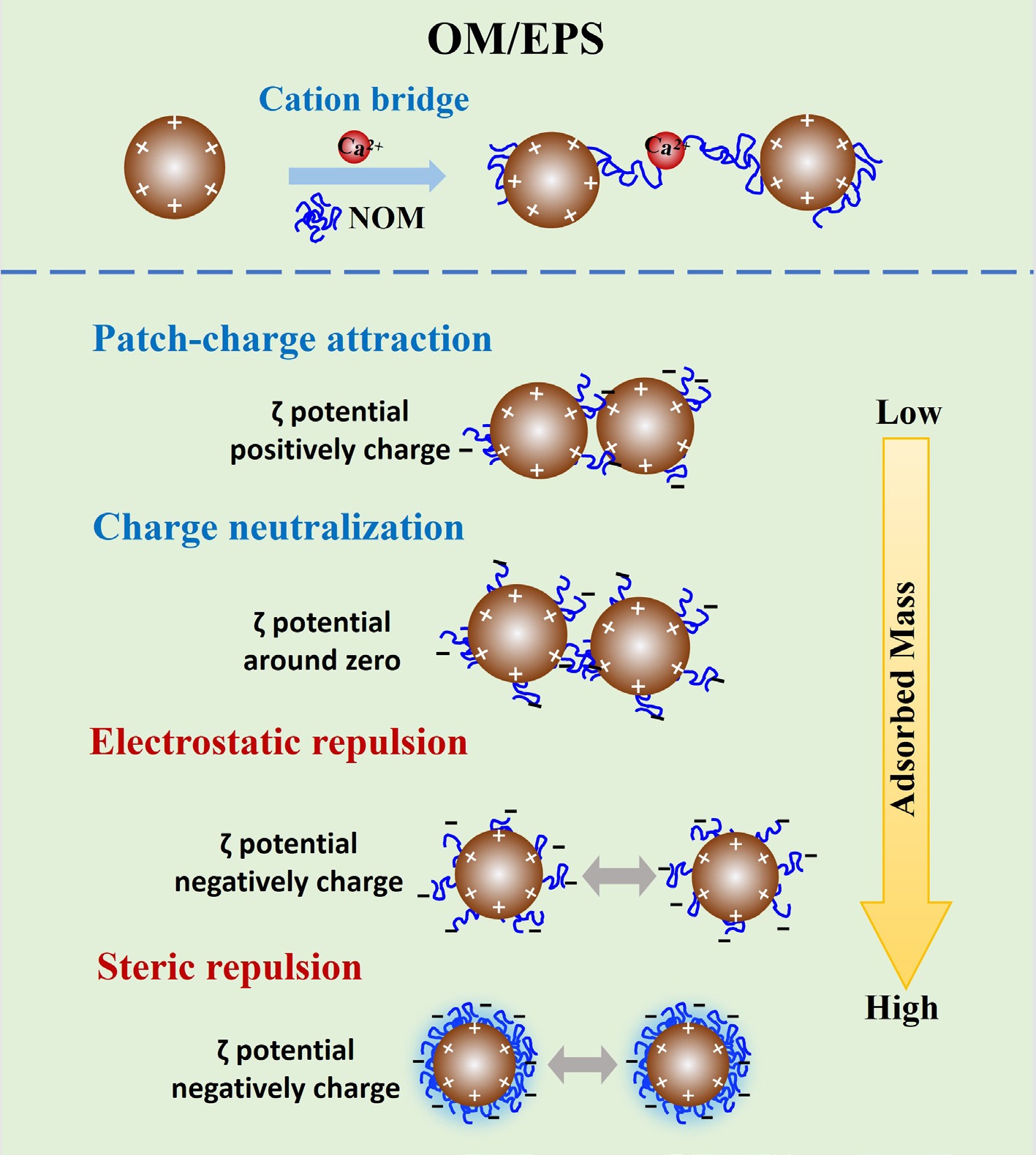

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the mechanisms by which OMs and microbes influence IONP aggregation.

-

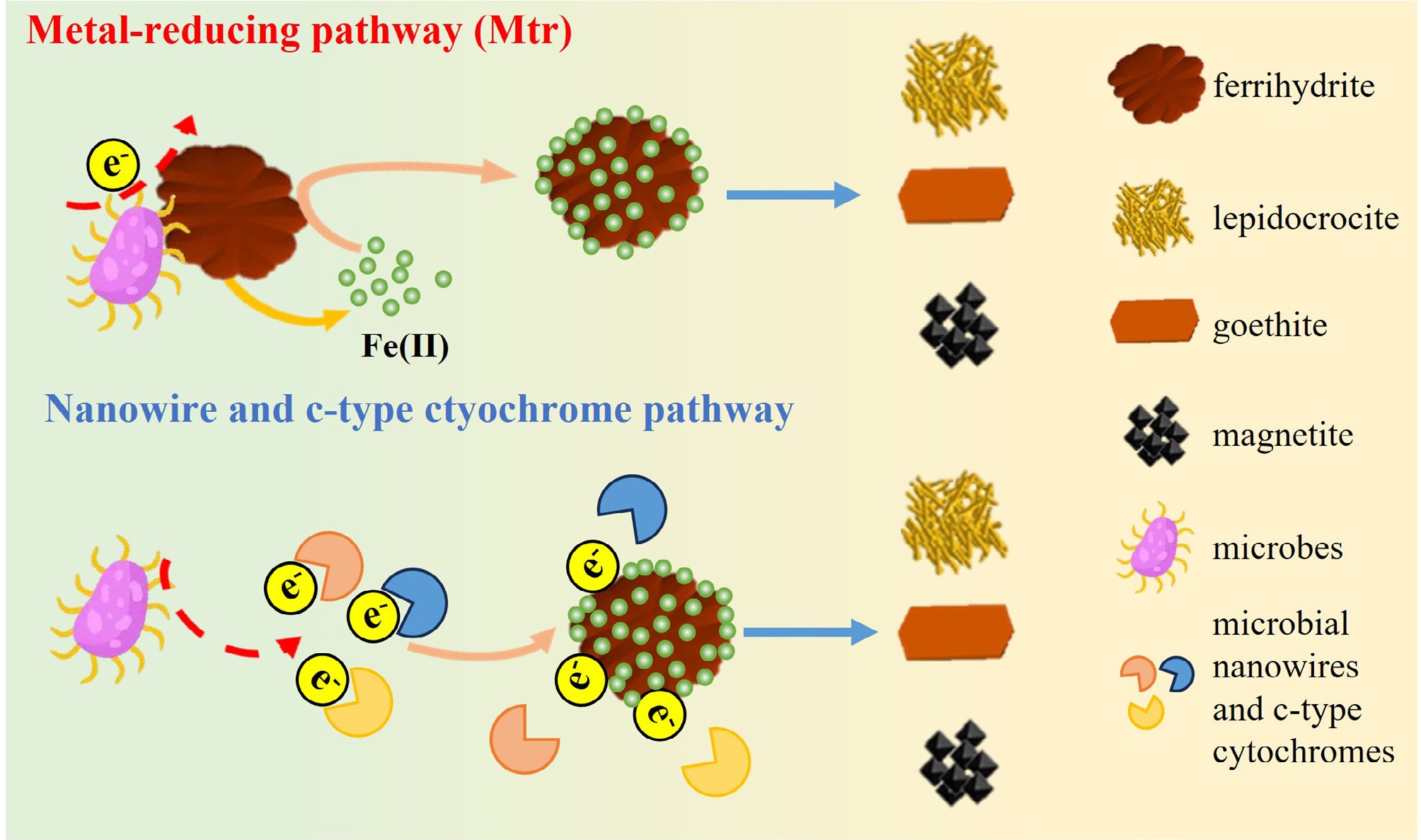

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of microbial effects on IONP transformation.

-

Ion Inhibitory effect Mechanism Impact on transformation pathway Redox behavior during transformation Cd2+[67−69] Strong inhibition at high concentrations Substitution into goethite > lepidocrocite; defect-related sorption Delays ferrihydrite transform to goethite/lepidocrocite; favors

ferrihydrite retentionNo significant redox change; immobilized by structural incorporation As(V/III)[75,77,92] Strong inhibition, especially As(V) Surface complexation and structural incorporation Stabilizes lepidocrocite, inhibits

goethite crystallizationAs(V) → As(III) (under reducing conditions); re-adsorption occurs Cr(VI)[81−83] Moderate inhibition Formation of Fe(III)-Cr(III) coprecipitates Enhances lepidocrocite/goethite formation if reduction is partial Cr(VI) → Cr(III), with Cr(V) intermediate; Cr(III) incorporated Si (H4SiO4)[85,89,91] Strong inhibition Surface complexation (Si–O–Fe), charge reversal Suppresses lepidocrocite/goethite/hematite crystallization; stabilizes ferrihydrite No redox role; purely structural/surface interference Mo(VI)[93] Dose-dependent effect Surface-sorbed; potential incorporation Low Mo: favors magnetite; high Mo: favors goethite Reduced to Mo(IV) (e.g., MoO2); retained in solid Co2+[94] Inhibits magnetite formation Incorporated into tetra-/

octahedral Fe sitesAlters Fe(II)-to-magnetite pathway; enhances goethite instead Incorporated without redox change; modifies magnetic properties Ce(III)[95] No inhibition; facilitates retention Strong association with Fe mineral surface Promotes Ce retention; less release Oxidized to Ce(IV) during transformation Sb(V)[96] Minor inhibition Adsorption/incorporation

in Fe mineralsNo significant pathway shift No redox change; remains Sb(V), structurally trapped V(V)[97] Inhibitory at high concentrations Substitution into Fe2+/Fe3+ sites Favors goethite over magnetite V(V) → V(IV)/V(III) reduction under microbial mediation Table 1.

Effects of aqueous ions on Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite/lepidocrocite transformation

-

OM property Effect on transformation Mechanism Carboxyl group richness[27,98] Inhibits Fh and Lp crystallization; stabilizes Fh Strong Fe–carboxylate binding; complexation with labile Fe(III) C/Fe molar ratio[28,114] Higher C/Fe inhibits Gt and Mt formation; favors Fh retention Controls surface coverage and Fe(II) interaction; not sufficient alone to predict outcome Molecular weight (MW)[30,31] Low MW + carboxyl-rich → inhibit; High MW →

promote Gt formationBinding affinity to labile Fe(III) varies with MW; steric/bridging effects at high MW Labile Fe(III) complexation[17,56,57] Prevents nucleation/crystallization of secondary minerals Fe(III)-ligand complexation inhibits polymerization Surface site blocking[28,101] Minor/secondary effect in some systems Blocks Fe(II) adsorption and electron transfer Thiol (–SH) and amino (–NH2) ligands[102,103] Promote Gt over Hm via dissolution–reprecipitation Reduce surface Fe(III) and shift transformation pathway Sulfide (S2–) + OM systems[105,106] OM modulates identity of Fe–S minerals formed (e.g., greigite vs pyrite) Carboxyl ligand effects on Fe–S–OM interactions Table 2.

Effects of organic matter on Fe(II)-catalyzed ferrihydrite transformation

Figures

(3)

Tables

(2)