-

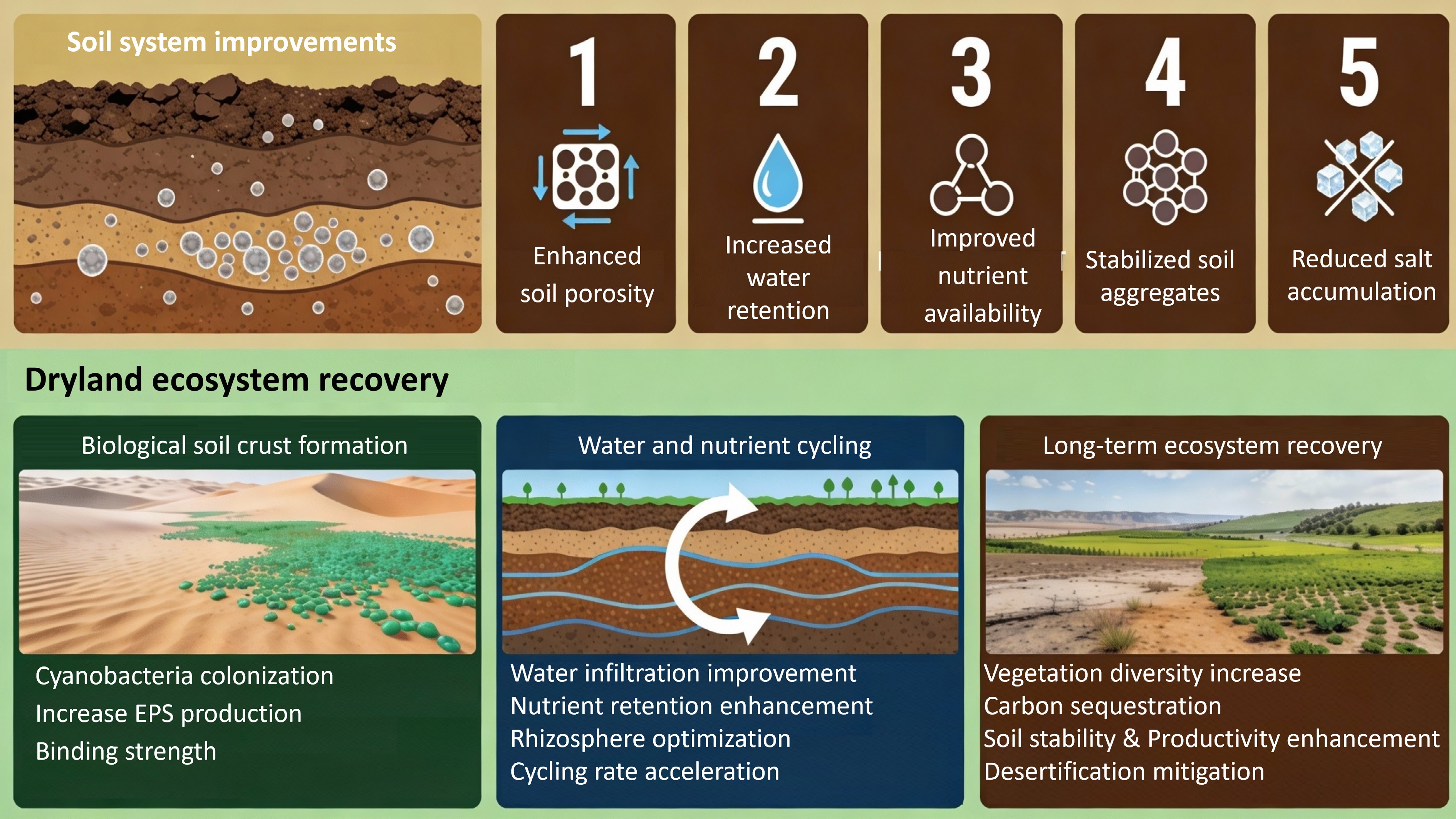

Figure 1.

Multifunctional benefits of biochar: physical, chemical, and biological soil improvements.

-

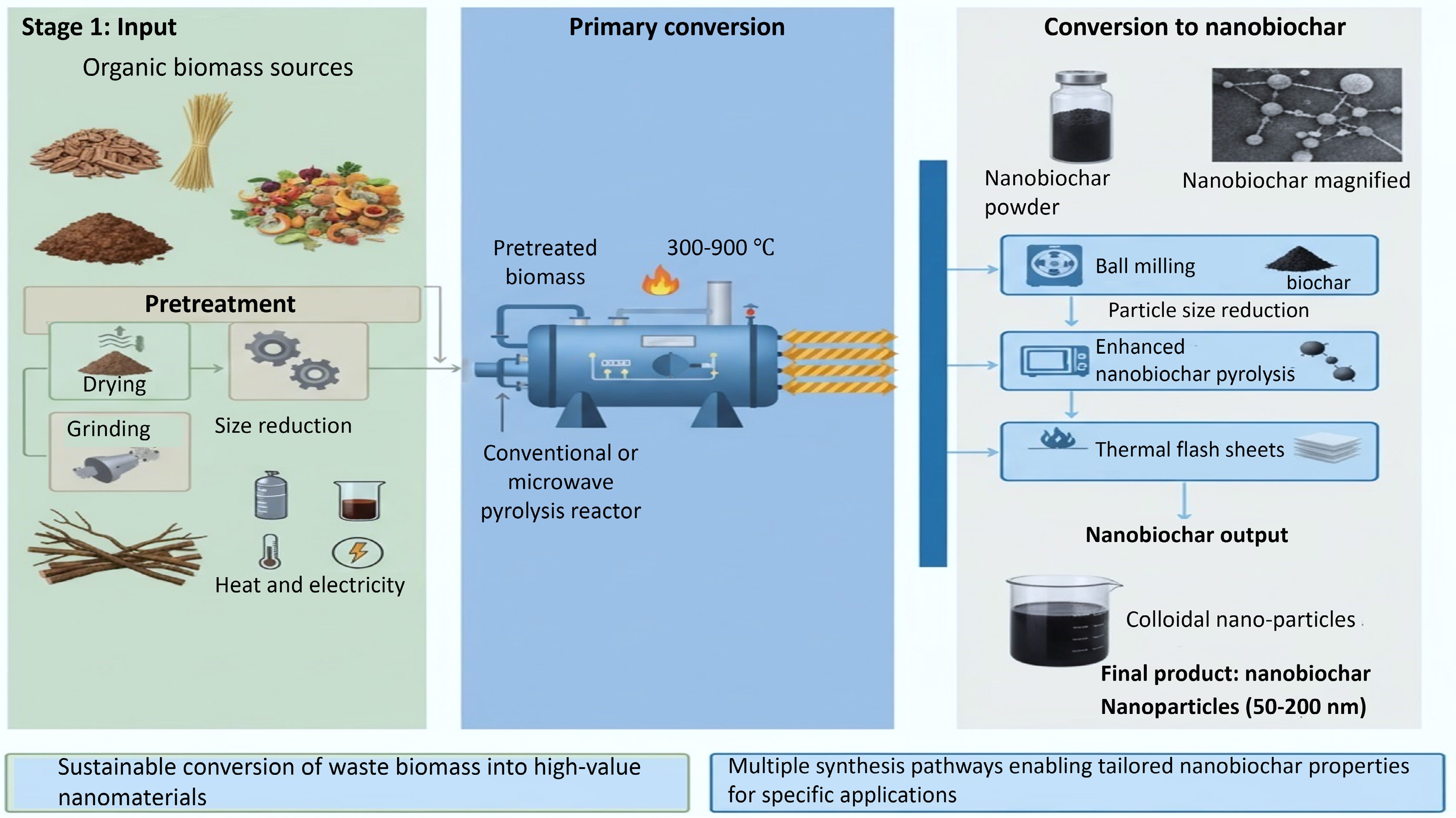

Figure 2.

Biochar production and nanobiochar synthesis: integration of multiple pathways.

-

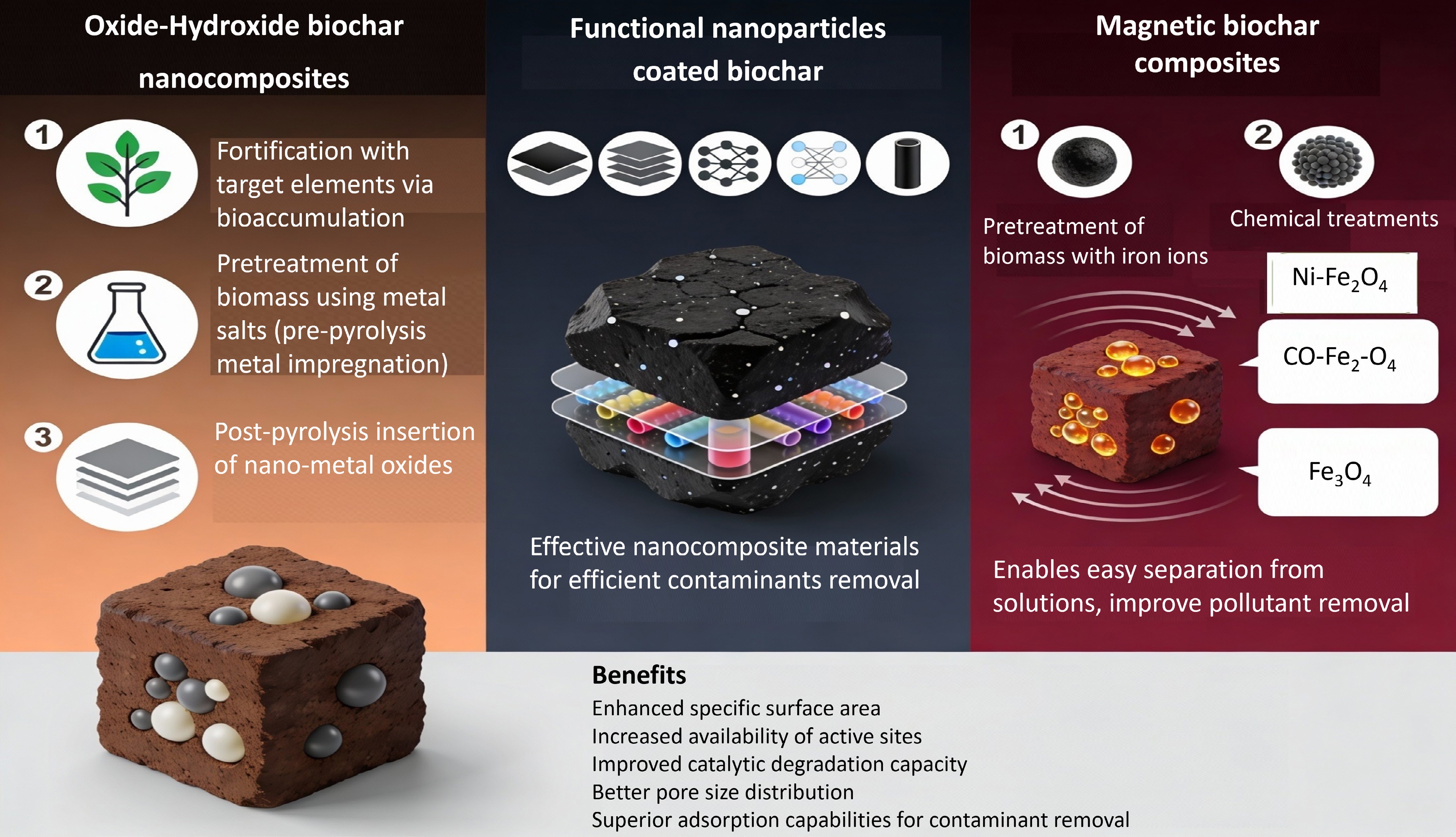

Figure 3.

Engineering biochar nanocomposites: synthesis methods for metal oxide, graphene, and magnetic systems.

-

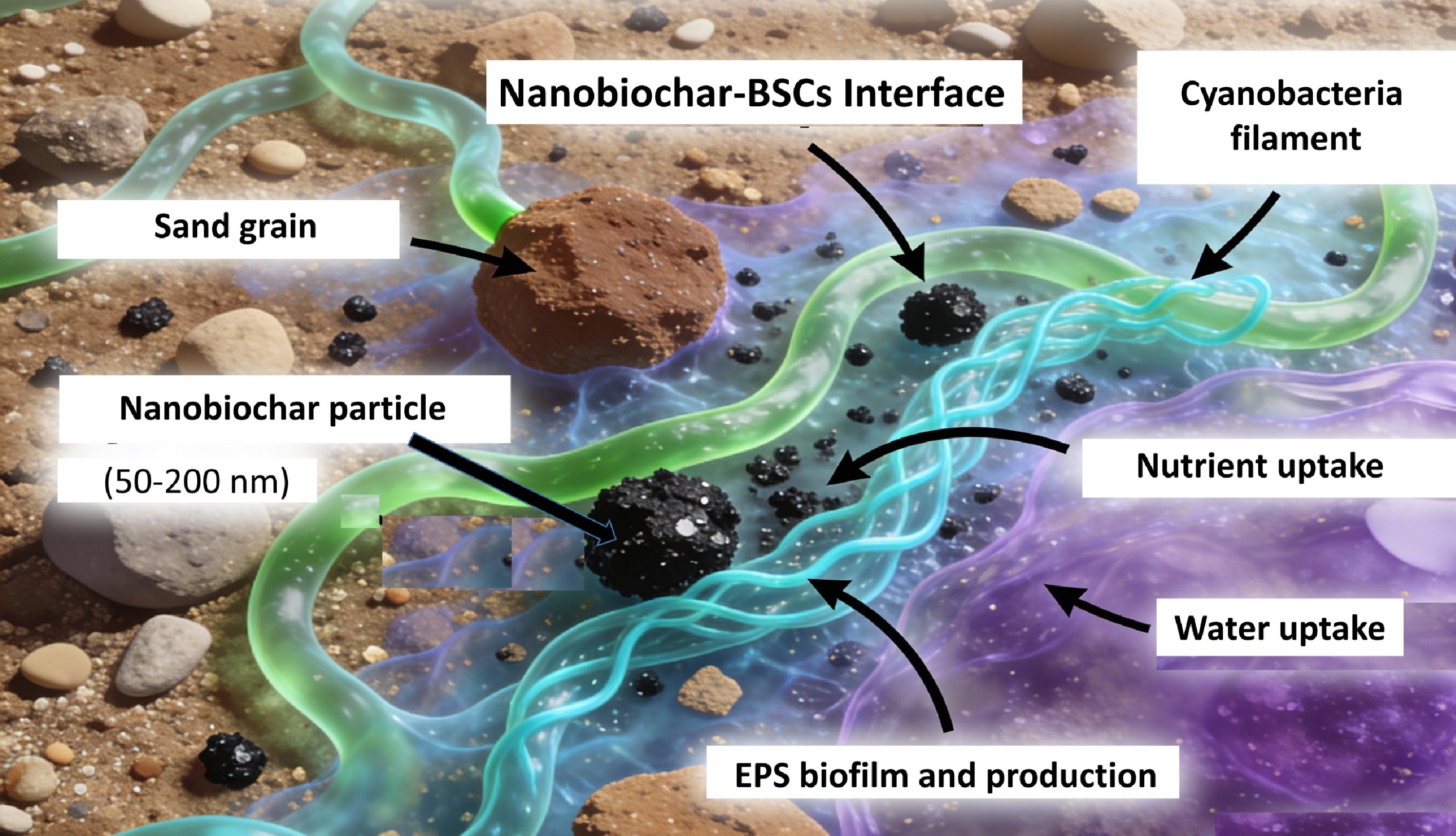

Figure 4.

Nanobiochar-mediated bio-Ink formation: nano-microbe-EPS interface in BSCs.

-

Synthesis method Classification and process description Key advantages Limitations Ref. Ball milling (Top-down) Mechanical grinding of bulk biochar using planetary mills; repeated impacts and friction induce particle size reduction; parameters include milling time, rotational speed, and ball-to-material ratio Eco-friendly; solvent-free; significantly increases surface area (up to 15-fold); creates acidic and oxygen-containing functional groups crucial for water retention; can be integrated into existing biochar supply chains High energy consumption; long processing times; potential contamination from milling media; particle size distribution variability; requires careful optimization of milling parameters [56−62] Hydrothermal carbonization (Bottom-up) Thermochemical conversion of wet biomass in water at high pressure and temperature (using concentrated sulfuric and nitric acid in high-pressure reactor) Produces uniform, spherical hydrochar nanoparticles; rich in surface functional groups; ideal for coating seeds or bacteria; superior control over surface functionality; enhanced water-retention Lower porosity compared to pyrolysis chars; requires post-synthesis activation; expensive reactor infrastructure; higher capital costs; more complex operational parameters [34,59] Pyrolysis + sonication (Hybrid) Conventional pyrolysis at 500–700 °C followed by high-intensity ultrasonic exfoliation; ultrasonic vibration physically disintegrates biochar to facilitate nanosized particle formation Effectively separates graphitic layers; improves aqueous dispersion; ideal for hydro-seeding applications; carbon enrichment through selective ash removal; enhanced dispersion in water Lower yield of nanoscale fraction; difficulty achieving uniform particle size distribution; energy-intensive sonication stage; incomplete particle separation [20,40,63] Vibration disc milling (Top-down) Similar to ball milling but uses vibrating disc mechanism instead of planetary mills; mechanical particle reduction through disc oscillation Superior results compared to ball milling in uniform shape and size generation; higher quantity of nanobiochar produced; consistent particle morphology Higher operational costs than planetary ball milling; less widely available equipment; similar energy demands [34,41] Double-disc milling (Top-down) Mechanical grinding between rotating discs; two-stage milling process for particle size reduction Produces fine particles; alternative to ball milling; suitable for specific feedstock types Higher operational costs; limited industrial adoption; requires specialized equipment maintenance [34] Table 1.

Comprehensive comparison of nanobiochar synthesis methods: production pathways and performance metrics

-

Feedstock type Synthesis method

and conditionsParticle size transformation Surface area (m2/g) Moisture (%) Ash (%) H/C ratio Ref. Wheat straw Pyrolysis at 700 °C followed by sonication Bulk biochar reduced to nanoparticles via ultrasonic exfoliation Bulk: 56.65;

Nano: 88.4Bulk: 41.14;

Nano: 52.35Bulk: 53.87;

Nano: 27.88Bulk: 0.39;

Nano: 0.67[40] Dairy manure Pyrolysis at 500 °C with sonication

(30 min) and centrifugationBulk biochar transformed to nanoparticles through ultrasonic separation − Bulk: 38.5;

Nano: 56.6Bulk: 50.5;

Nano: 6.58Bulk: 0.12;

Nano: 3.65[64] Corn straw Pyrolysis at 500 °C with planetary ball milling (600 rpm, 150 min) Bulk biochar mechanically milled to approximately 60 nm particle size Bulk: 8.1;

Nano: 7.9Bulk: 5.13;

Nano: 6.27Bulk: 78.96;

Nano: 77.62Bulk: 0.72;

Nano: 0.51[53] Rice husk Pyrolysis at 500 °C with planetary ball milling (600 rpm, 150 min) Bulk biochar ground to nanoparticles via mechanical attrition Bulk: 8.6;

Nano: 8.7Bulk: 31.55;

Nano: 31.51Bulk: 54.62;

Nano: 53.05Bulk: 0.77;

Nano: 0.78[53] Pine wood Pyrolysis at 525 °C with ball milling (575 rpm, 100 min) Bulk biochar mechanically reduced to nanoscale particles Bulk: 47.25;

Nano: higher valuesBulk: 2;

Nano: 2.11− Bulk: 1.0;

Nano: 0.5[65] Rice hull Carbonization at 600 °C with centrifugation (10,000 rpm, 30 min) and freeze-drying Bulk biochar processed to nanoparticles through centrifugal separation Bulk: 27.1;

Nano: 123.2Bulk: 79.62;

Nano: 80.87Bulk: 1.08;

Nano: 1.27− [66] Rice husk Pyrolysis at 600 °C with planetary ball milling and chemical amendment

(Iron Oxide nanobiochar)Bulk biochar converted to nanoparticles Bulk: —;

Nano: 1,736− − − [67] A dash (—) indicates that specific data for that property were not reported. H/C: Hydrogen-to-Carbon ratio. Table 2.

Comprehensive physicochemical characterization of biochar and nanobiochar: transformation of properties by feedstock type and production method

-

Pollutants removed Pollutant category Composite composition Adsorption mechanism Application scope Ref. Pb2+, Cu2+, Zn2+ Heavy metals Biochar + hydroxyapatite mineral coating Chelation bonding with phosphate groups; ion exchange Industrial wastewater treatment; Contaminated water remediation [126] Cr6+, Cu2+, Pb2+ Heavy metals (hexavalent chromium) Biochar integrated with zinc oxide and zinc sulfide nanoparticles Redox reduction of Cr6+ to Cr3+; electrostatic adsorption; complexation Chromium-contaminated wastewater; Metal-rich industrial effluents [125] Pb2+ Heavy metal (lead) Biochar surface coated with manganese oxide nanoparticles Oxidation-adsorption synergy; manganese oxide sorption sites; ion exchange Lead contamination in aqueous solutions; Mining wastewater [69] Metformin hydrochloride (MFH) Pharmaceutical pollutant (antidiabetic drug metabolite) Biochar treated with sodium hydroxide creating alkaline surface Electrostatic attraction to basic sites; hydrogen bonding; pore filling Pharmaceutical wastewater [127] Tetracycline and Hg2+ Antibiotic + toxic metal Biochar with embedded magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4 or CoFe2O4) Magnetic adsorption; surface functional group binding; chelation Antibiotic-contaminated agricultural runoff; Mercury-contaminated water; Easy magnetic recovery [128] Fluoride (inorganic) Inorganic anion pollutant Biochar derived from corn stover with iron oxide modification Ion exchange mechanism with iron oxide sites; adsorption to hydroxyl groups Fluoride-contaminated groundwater; Industrial fluoride-containing wastewater [129] Cu2+, Cd2+, Pb2+ Multiple heavy metals Biochar surface treated with potassium permanganate creating nanometal oxide sites Oxidative adsorption from permanganate sites; ion exchange; complexation Multi-metal contaminated solutions; Electroplating industry wastewater [130] Phosphate (inorganic) Nutrient ion pollutant (eutrophication control) Biochar with magnesium oxide and magnesium hydroxide nanoparticles Precipitation reaction with magnesium species; Lewis acid-base interactions Nutrient-rich wastewater treatment; Eutrophication prevention; Agricultural runoff [131] Table 3.

Comprehensive assessment of pollutant elimination through adsorption using nanobiochar and biochar nanocomposites

Figures

(4)

Tables

(3)