-

Enzymes are biomolecules that consist of amino acid subunits linked together by amide bonds. They are highly discerning biocatalysts that accelerate the rate and specificity of biological reactions by reducing the activation energy without any structural modification[1−3]. The active site of these macromolecules is domiciled within hydrophobic pockets, which determines their specificity for substrate[4]. Enzymes are secreted by living organisms and are required to sustain life. Enzymes play a crucial role in numerous biotechnological applications. Currently, the most commonly used (more than 75%) enzymes for commercial applications are hydrolases, which catalyze the hydrolysis of various natural molecules[5]. However, proteases are recognized as the leading enzyme due to their versatility in biotechnology[2,6].

Proteases are the largest and the most complex group of enzymes that catalyze the breakdown of proteins by cleaving of peptide bonds that exist between amino acid residues in a polypeptide chain[7,8]. They constitute one of the most important groups of enzymes, accounting for more than 65% of the total industrial enzyme market[9−14]. They are ubiquitous in nature and obtained from a wide variety of sources, including plants[15−20], animals[21−23] and microorganisms[24]. However, the failure of plant and animal proteases to meet global demands has led to an increased interest in microbial proteases.

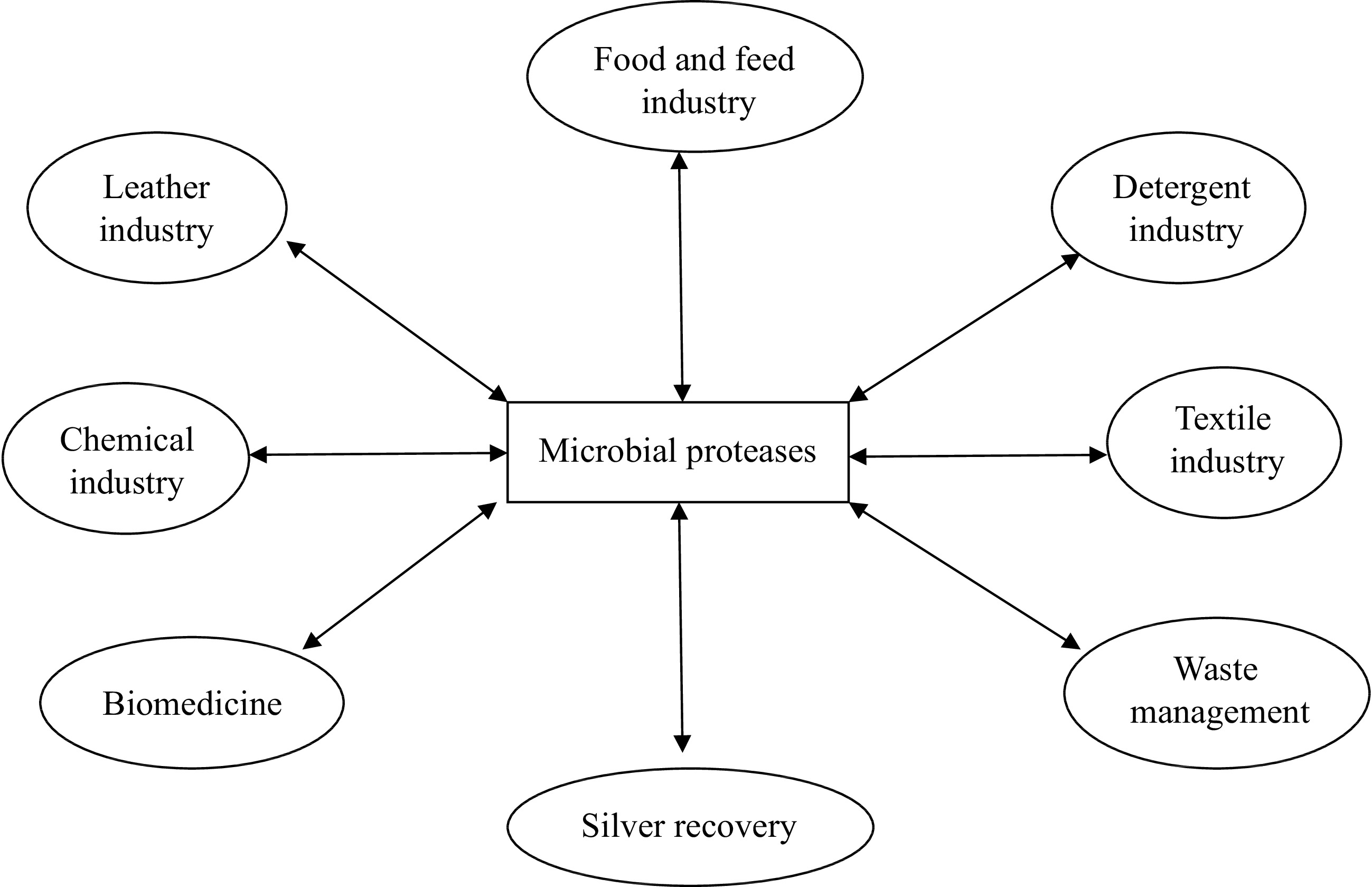

Microbial proteases are among the most important and extensively studied hydrolytic enzymes since the beginning of enzymology[24]. They constitute more than 40% of the total worldwide production of enzymes[25,26]. They are produced by a large number of microbes, including bacteria, fungi, and yeasts (Table 1)[27,28]. The microorganisms represent an excellent source of proteases due to their rapid growth, broad biochemical diversity, ease of genetic manipulation, and limited space requirements for cultivation. In addition, the microorganisms can be cultivated in large amounts in a relatively short time by an established fermentation process for mass production of the enzymes[61]. Microbial proteases are secreted directly into the fermentation medium by the producing organisms, thus shortening the downstream processing of the enzyme[24]. They have a longer shelf life and can be preserved for a long period of time without significant loss of activity. However, of all microbial sources, bacterial proteases are of particular interest due to their high catalytic activity and stability at optimal pH and temperature and broad substrate specificity[62−66]. Furthermore, microbial proteases are employed in various biotechnological applications, including detergent, chemical, pharmaceutical, textile, food and feed and leather industries, as well as in silver recovery and waste management (Fig. 1)[11−14,27,67−76]. This review, therefore, focuses on microbial proteases with special emphasis on bioprocess parameters influencing microbial protease production coupled with techniques for downstream purification of proteases. In addition, strategies employed for immobilization of the biocatalysts in or on appropriate support materials as well as the biochemical properties of the enzymes were also discussed for a proper understanding of the potential of the biocatalysts for industrial, environmental, and biomedical applications.

Table 1. Some protease-producing microorganisms.

Microorganism Reference Bacteria Bacillus sp. CL18 [29] Bacillus aryabhattai Ab15-ES [30] Bacillus stearothermophilus [31] Bacillus amyloliquefaciens [32] Geobacillus toebii LBT 77 [33] Pseudomonas fluorescens BJ-10 [34] Streptomyces sp. DPUA 1576 [35] Vibrio mimicus VM 573 [36] Lactobacillus helveticus M92 [37] Microbacterium sp. HSL10 [38] Serratia marcescens RSPB 11 [39] Listeria monocytogenes [40] Brevibacterium linens ATCC 9174 [41] Alteromonas sp. [42] Halobacillus blutaparonensis M9 [43] Staphylococcus epidermidis [44] Yersinia ruckeri [45] Geobacillus stearothermophilus [46] Stenotrophomonas sp. [47] Aeromonas veronii OB3 [48] Fungi Alternaria solani [49] Aspergillus niger DEF 1 [50] Penicillium sp. LCJ228 [51] Fusarium solani [52] Rhizopus stolonifer [53] Trichoderma viridiae VPG12 [54] Mucor sp. [55] Moorella speciosa [56] Beauveria sp. [7] Cephalosporium sp. KSM 388 [57] Yeasts Wickerhamomyces anomalus 227 [58] Metschnikovia pulcherrima 446 [58] Candida spp. [13] Yarrowia lipolytica [59] Rhototorula mucilaginosa KKU-M12C [60] Cryptococcus albidus KKU-M13C [60] -

Microbial proteases are produced by submerged fermentation and to a lesser extent by solid-state fermentation processes during the post-exponential or stationary growth phase[77−79]. However, submerged fermentation is mostly preferred due to its easy engineering and improved process control. In addition, submerged fermentation permits ease of enzyme reclamation for downstream processing, even distribution of microbial cells in the culture medium, and reduced fermentation time[77,78]. Protease production from microorganisms is constitutive or partially inducible in nature, and the type of substrate utilized in the fermentation medium mostly influences their synthesis. The selection of appropriate inducible substrates and microbial strains is paramount for the production of the desired metabolite[30,80−84].

-

Various bioprocess parameters (such as carbon and nitrogen sources, pH, temperature, metal ions, inoculum volume, incubation period, agitation speed, etc.) affect protease secretion by microorganisms. Each microbe requires optimum conditions of the parameters for maximum protease production[30]. These nutritional and physicochemical parameters are discussed below.

Carbon sources

-

Extracellular protease production by microorganisms is strongly influenced by the presence of suitable carbon sources in the culture medium. Enhanced yields of protease synthesis by addition of different carbon sources have been reported by different authors[30,85]. For instance, Sharma et al.[86] recorded maximum protease production by a bacterial strain AKS-4 when glucose was used as a carbon source in the growth media at a concentration of 1% (w/v), resulting in a maximum activity of 59.10 U/ml. In another study, Adetunji & Olaniran[30] investigated the influence of different carbon sources including fructose, galactose, mannose, maltose, sucrose, lactose, and soluble starch on protease production by Bacillus aryabhattai Ab15-ES. Maximum protease production (67.73 U/ml) was recorded in the presence of maltose.

Nitrogen sources

-

Microbial protease production is greatly influenced by the presence of a variety of nitrogen sources in the fermentation medium[24]. Although complex nitrogen sources are commonly utilized for protease secretion by most microorganisms, the requirement for a particular nitrogen supplement differs from one organism to another[13,27]. In most microorganisms, both organic and inorganic nitrogen sources are metabolized to produce amino acids, nucleic acids, proteins and other cell wall components[27,67]. Several authors have employed organic (simple or complex) and inorganic nitrogen sources for enhancement of protease production. These nitrogen sources have regulatory effects on protease synthesis. Kumar et al.[87] studied the effect of organic and inorganic nitrogen sources on protease production by Marinobacter sp. GA CAS9. Results obtained revealed that organic nitrogen sources induced higher protease production than inorganic nitrogen sources, with maximum protease production (249.18 U/ml) recorded in the presence of beef extract. Badhe et al.[88] studied the influence of nitrogen sources namely, ammonium nitrate, ammonium chloride, ammonium sulphate, yeast extract, potassium nitrate, and sodium nitrate on extracellular protease production by Bacillus subtilis. Yeast extract was found to be the best nitrogen source to stimulate maximum protease production. Urea and sodium nitrate have been reported as the best organic and inorganic nitrogen sources, respectively for extracellular protease production by Bacillus licheniformis ATCC 12759[89].

Physicochemical parameters

-

Several physicochemical parameters including pH, temperature, agitation speed, incubation period, metal ions, inoculum volume etc. influence protease secretion[90−92]. These parameters are essential to promote the growth of microorganisms for protease production. For instance, slightly acidic medium with pH range of 6.3−6.5 has been found as optimum for protease production by Bacillus sp. MIG and Bacillus cereus SIU1[93,94]. Maximum protease production by Bacillus subtilis NS and Pseudomonas fluorescens was recorded when the initial pH of the fermentation media was 9.0[95,96]. Higher initial pH values of 12.0 (Bacillus cereus S8), 10.5 (Bacillus circulans), and 10.7 (Bacillus sp. 2-5)[97−99] have also been reported for maximum protease production.

In addition, incubation temperature is a crucial environmental parameter for the production of proteases, since it affects microbial growth and synthesis of the enzyme by changing the properties of the cell wall[100]. Optimum temperatures of 30, 37, 40, and 60 °C for protease production by Pseudomonas aeruginosa MCM B-327[101], Bacillus subtilis AKRS3[102], Bacillus sp. NPST-AK15[100], and Bacillus polymyxa[103], respectively have been reported. Agitation speed influences the degree of mixing of fermentation media in shake flasks or bioreactor for the supply of dissolved oxygen needed for the growth of microorganisms for protease production[104,105]. Maximum protease production has been reported at agitation speed of 150 rpm (Bacillus sp. CR-179; Aspergillus ochraceus BT21) and 200 rpm (Bacillus mojavensis SA)[106−108]. Incubation period considerably affects microbial protease production, and varies (24 h to 1 week), based on the microorganism type and culture conditions[109]. Metal ions promote microbial protease production. For instance, Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and Ba2+ enhance protease secretion by Bacillus cereus BG1, Bacillus subtilis NS, Brevibacillus sp. OA30, and Bacillus sp. NPST-AK15, respectively[95,100,110,111]. However, metal ions can render inhibitory effects on protease production by microorganisms[112].

-

After fermentative production of enzymes, the cell-free culture supernatant (regarded as crude enzyme) is purified for the reclamation of value-added enzyme products using a variety of techniques[61,113]. The selection of suitable purification methods is dependent on the source of the biocatalyst (extracellular or intracellular). Such techniques should be cost-effective and efficient for high-value enzyme purification[114,115]. The advantages and disadvantages of these techniques are highlighted in Table 2 and described below.

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of protease purification methods.

Purification method Advantage Disadvantage Ultrafiltration High product throughput; lower complexity; economical; low maintenance; requires no chemicals Clogging of membrane hinders purification process Precipitation Simple; reduces enzyme solubility in aqueous solution Not efficient for complete enzyme purification; time consuming; difficult to use for large-scale enzyme purification Ion-exchange chromatography High separation efficiency; simple; controllable Buffer requirement; pH dependence; inconsistency in columns; expensive columns Affinity chromatography High sensitivity and specificity; gives high degree of enzyme purity Difficult to handle; requires limited sample volume; low productivity; uses expensive ligands; non-specific adsorption Hydrophobic interaction chromatography Versatile; non-denaturing Requirement for non-volatile mobile phase Ultrafiltration

-

Because of the low amounts of enzyme in the cell-free supernatant, excess water is usually removed for the recovery of the enzyme. This is achieved via membrane separation processes such as ultrafiltration. This pressure-driven separation process is inexpensive and leads to a slight loss of enzyme activity. It is used for purification, concentration, and diafiltration of enzyme, or for changing the salt composition of a given sample[27,116,117]. However, the major drawbacks of this technique include fouling or clogging of membranes, resulting from precipitates formed by the final product[118].

Precipitation

-

Precipitation is the most frequently used technique for the separation of enzymes from crude culture supernatants[31,119]. It is carried out by the addition of inorganic salt (ammonium sulphate) or organic solvent (acetone or ethanol), which reduces the solubility of the desired enzymes in an aqueous solution[120,121].

Ion exchange chromatography

-

Ion exchange chromatography is employed for the production of purified proteases. The enzymes are positively charged biomolecules and are not bound to anion exchangers[27,122]. As a result, cation exchangers are a rational choice for the elution of the bound molecules from the column by increasing the salt or pH gradient[24]. The commonly employed matrices for ion-exchange chromatography include diethyl amino ethyl and carboxy methyl, which, upon binding to the charged enzyme molecules, adsorb the proteins to the matrices. Elution of the adsorbed protein molecule is achieved by a gradient change in pH or ionic strength of the eluting buffer[24,123].

Affinity chromatography

-

The most commonly used adsorbents for protease purification by affinity chromatography include hydroxyapatite, immobilized N-benzoyloxycarbonyl phenylalanine agarose, immobilized casein glutamic acid, aprotinin-agarose, and casein-agarose[124,125]. However, the ultimate disadvantage of this technique is the high costs of enzyme supports and the labile nature of some affinity ligands, thus reducing its use on a large scale[24,27,126].

Hydrophobic interaction chromatography

-

Hydrophobic interaction chromatography is based on the variation of external hydrophobic amino acid residues on different proteins, resulting in protein interaction[127]. In aqueous solvents, hydrophobic patches on proteins preferentially interrelate with other hydrophobic surfaces[128]. These hydrophobic interactions are reinforced by high salt concentrations and higher temperatures and are weakened by the presence of detergents or miscible organic solvents[129]. The degree of binding of a hydrophobic protein depends on the type and density of substitution of the matrix as well as on the nature of buffer conditions[24].

-

Enzyme immobilization refers to the physical confinement of enzymes in a defined region (matrix) to retain the activity of the biocatalysts[130,131]. Immobilization of enzymes in appropriate insoluble supports is a vital tool to fabricate biomolecules with a variety of functional properties[132,133]. It offers many distinct advantages, including reusability of immobilized biocatalysts, rapid termination of reactions, controlled product formation, and ease of reclamation of insolubilized enzymes from reaction mixture[134−136]. In addition, insolubilization of enzymes by attachment to a matrix provides several benefits, such as enhanced stability, possible modulation of the catalytic properties, reduction in the cost of enzymes and enzyme products, and adaptability to various engineering designs[137−142].

The characteristics of a matrix are crucial in determining the effectiveness of the immobilized enzyme system[130]. The characteristics of a good matrix include hydrophilicity, non-toxicity, biodegradability, resistance to microbial invasion and compression, biocompatibility, inertness towards enzymes, and affordability[143]. The selection of appropriate support materials influences the immobilization process. The support materials can be grouped into two categories namely, organic and inorganic based on their chemical components, or natural and synthetic polymers. These include porous glass[144], aluminium oxide, titanium, hydroxyapatite, ceramics, celite[130,134, 145,146], carboxymethyl cellulose, starch, collagen, sepharose, resins, silica[147], agarose[148,149], clay[150], and some mesoporous polymers[151].

The choice of a suitable immobilization technique is paramount for the immobilization process, as it determines the activity and characteristics of the enzyme in a particular biochemical reaction[56,130]. Methods such as entrapment, adsorption, cross-linking, and covalent bonding are commonly used for enzyme immobilization[152−155]. Immobilization of protease from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SP1 by entrapment in various matrices, including alginate, agar, and polyacrylamide has been reported[156]. The immobilized enzyme showed enhanced protease activity and reusability with beads prepared with different polymers. In addition, Bacillus subtilis M-11 protease immobilized on polysulfone membrane (containing silica gel-3 aminopropyltriethoxysilane) by physical adsorption displayed improved stability and retention of its activity (77.3%) after ten consecutive batches[155]. Ibrahim et al.[157] immobilized protease from Bacillus sp. NPST-AK15 onto hollow core-mesoporous shell silica nanospheres by covalent attachment and physical adsorption. The immobilized enzyme recorded significant thermal and organic solvent stability with a considerable catalytic activity for 12 consecutive batches. Silva et al.[158] studied the immobilization of protease (Esperase) by covelent bonding to Eudragit S-100 through carbodiimide coupling. The immobilized enzyme exhibited a good thermal and storage stability and reusability in comparison to the native enzyme.

-

Proteases from different microorganisms have been extensively studied for suitability for various specific applications based on their properties[27,159]. For biotechnological applications, proteases must possess higher activity and stability at relatively extreme temperatures, pH, and in organic solvents, oxidizing agents, detergents, etc.[48,160]. The essential properties of some microbial proteases are presented in Table 3 and discussed below.

Table 3. Biochemical properties of some microbial proteases.

Microorganism pH optima Temperature optima (°C) Kinetics parameter

(Km and Vmax)Substrate specificity Reference Bacillus sp. CL18 8.0 55 − Casein and soy protein [29] Bacillus caseinilyticus 8.0 60 − Casein, bovine serum albumin, gelatin and egg albumin [161] Bacillus licheniformis A10 9.0 70 0.033 mg/ml & 8.17 µmol/ml/min Casein [162] Bacillus licheniformis UV-9 11.0 60 5 mg/ml & 61.58 µM/ml/min Casein, haemoglobin and bovine albumin [163] Bacillus pumilus MCAS8 9.0 60 − Bovine serum albumin, casein, haemoglobin, skim milk, azocasein and gelatin [164] Bacillus pseudofirmus 10 50 0.08 mg/ml & 6.346 µM/min Casein [26] Bacillus circulans MTCC 7942 10 60 3.1 mg/ml & 1.8 µmol/min Casein [165] Bacillus circulans M34 11 50 0.96 mg/ml & 9.548 µmol/ml/min Casein, ovalbumin and bovine serum albumin [166] Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SP1 8.0 60 0.125 mg/ml & 12820 µg/ml Casein [156] Bacillus sp. NPST-AK15 10.5 60 2.5 mg/ml & 42.5 µM/min/mg Gelatin, bovine serum albumin and casein [8] Stenotrophomonas maltophilia SK 9.0 40 − Bovine serum albumin, casein and gelatin [167] Stenotrophomonas sp. IIIM-ST045 10.0 15 − − [47] Aeribacillus pallidus C10 9.0 60 0.197 mg/ml & 7.29 µmol/ml/min Casein [168] Geobacillus toebii LBT 77 13.0 95 1 mg/ml & 217.5 U/ml − [33] Streptomyces sp. M30 9.0 80 35.7 mg/ml & 5 × 104 U/mg Casein, bovine serum albumin, bovine serum fibrin [169] Alternaria solani 9.0 50 − − [49] Beauveria bassiana AM-118 8.0 35−40 0.216 and 0.7184 mM & 3.33 and 1.17 U/mg − [170] Effect of pH on activity and stability of microbial proteases

-

A significant level of proteolytic activity over a broad range of pH is required for protease to be employed for various biotechnological applications[46,171]. In general, microbial proteases exhibit high activity at an optimum pH range of between 8.0 and 12.0[28]. Optimum pH and stability of protease from Aeribacillus pallidus C10 have been reported[168]. The enzyme was found to be active within a broad pH range of 7.0−10.0, with maximum activity recorded at pH 9.0. The protease retained its activity by more than 70% in the range of pH 6.0−10.5 after 2 h of incubation. Proteases from Bacillus pumilus CBS, Bacillus strain HUTBS71, and Bacillus licheniformis with similar pH stability profiles have been reported[172−174]. Ibrahim et al.[8] assessed the influence of pH on the activity and stability of the protease produced by Bacillus sp. NPST-AK15. The enzyme was active in a wide pH range (7.0−12.0), with maximum activity recorded at pH 10.5. The protease was 100% stable at pH 9.0−10.5, retaining 96.6 and 92.3% of its activity at pH 8.0 and 11.0, respectively, and more than 80% of its initial activity retained at pH 12.0 after 2 h. Protease from Bacillus circulans MTCC 7942 exhibited activity in the range of 8.0−13.0 with optimum activity recorded at pH 10.0. The enzyme maintained its stability in a wide range of pH (7.0−12.0) for 24 h, retaining 90% activity in the pH range (8.0−12.0)[165]. Similar results have also been reported for proteases from Bacillus tequilensis P15[175], Bacillus subtilis AP-MSU6[176], Bacillus circulans[177], Bacillus lehensis[178], and Bacillus alveayuensis CAS 5[179] showing optimal pH in the range of 8.0−12.0. Maximum activity of protease from Bacillus pumilus MCAS8 at pH 9.0 and stability in the range of 7.0−11.0 after 30 min have been observed[164]. Remarkably, protease from Bacillus circulans M34 showed maximum activity at an optimum pH of 11.0 and was found to be active over a broad pH range (4.0−12.0)[166]. The enzyme was stable over a wide pH range, maintaining 97% of its original activity at pH 8.0−11.0 after 1 h.

Effect of temperature on activity and stability of microbial proteases

-

Most of the microbial proteases are active and stable at a broad range of temperatures (50-70 °C). The activity of proteases at broad temperatures and thermostability form a crucial feature required for employability of the enzyme in industries[32]. Proteases from Bacillus sp., Streptomyces sp., and Thermus sp. are stable at high temperatures; the addition of calcium chloride further improves the enzyme’s thermostability[180]. In addition, some proteases possess exceptionally high thermostability with no decrease in activity at 60−70 °C for up to 3 h[171]. Ahmetoglu et al.[181] investigated the characteristics of protease from Bacillus sp. KG5. The enzyme was found to be active at 40−45 °C and stable at 50 °C in the presence of 2 mM CaCl2 after 120 min. Thebti et al.[33] characterized a haloalkaline protease from Geobacillus toebii LBT 77 newly isolated from a Tunisian hot spring. The enzyme was active between 70 and 100 °C with an optimum activity recorded at 95 °C. The protease was extremely stable at 90 °C after 180 min. Similar results have also been reported for protease from Bacillus sp. MLA64[182]. This activation and stability at higher temperatures were probably due to the partial thermal inactivation of the protease. Protease from Bacillus caseinilyticus was found to be active at 30−60 °C, with maximum activity attained at 60 °C, indicating the thermotolerant nature of the enzyme[161]. Maximum proteolytic activity of Bacillus strains HR-08 and KR-8102 isolated in the soil of western and northern parts of Iran has been recorded at 65 and 50 °C, respectively[183]. Protease from Bacillus subtilis DR8806 showed the highest activity at 45 °C and was stable up to 70 °C[184]. Bacillus cohnii APT5 protease has been reported to be active at a broad range of temperatures, between 30 and 75 °C with maximum activity attained at 50 °C[185]. The enzyme was found to be stable from 40 to 70 °C.

-

Since enzymes are natural catalysts that accelerate chemical reactions, the speed of any fastidious reaction being catalyzed by a particular enzyme can only reach a certain maximum value. This is known as the maximum velocity (Vmax) whereas the Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) is the concentration of substrate at which half of the maximal velocity was attained[31,186]. The relationship between the rate of reaction and the concentration of substrate depends on the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate; this is usually expressed as the Km[186]. An enzyme with a low Km has a greater affinity for its substrate. Both Km and Vmax are important for developing an enzyme-based process[187]. Knowledge of such parameters is essential for assessing the commercial applications of protease under different conditions[24,188]. Substrates including casein, azocasein, etc. are employed to determine the kinetic properties of proteases. Different Km and Vmax values have been reported for proteases. The Km and Vmax values of protease from Bacillus licheniformis A10 were determined to be 0.033 mg/ml and 8.17 µmol/ml/min, respectively in the presence of casein[162]. This Km value was found to be lower when compared to that of proteases from Bacillus licheniformis UV-9[163], Bacillus circulans[189] and Bacillus sp.[190], suggesting a high affinity of the enzyme for the substrate. In another study, Km and Vmax values of 0.626 mM and 0.0523 mM/min, respectively were recorded for protease from Bacillus licheniformis BBRC 100053 using casein[191]. Protease from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SP1 showed Km and Vmax values of 0.125 mg/ml and 12,820 µg/min, respectively in the presence of casein, indicating high affinity and efficient catalytic activity of the enzyme[156].

-

Microbial proteases are robust enzymes with significant biotechnological applications in detergents, leather processing, silver recovery, pharmaceutical, dairy, baking, beverages, feeds, and chemical industries, as well as in several bioremediation processes, contributing to the formation of high value-added products (Fig. 1)[28, 192]. In addition, the proteases are employed in degumming of silk and biopolishing of wool in the textile industry and as an essential tool in peptide synthesis as well as in molecular biology and genetic engineering experiments[193]. The various applications of microbial proteases are elucidated in Table 4 and discussed explicitly below.

Table 4. Some potential biotechnological applications of microbial proteases

Industry Application Product Detergent Remove proteinaceous stains from clothes

Improve washing performance in domestic laundryClean fabrics Leather Soaking, dehairing and bating

Enhance leather quality

Reduce or eliminate dependence on toxic chemicalsSoft, supple and pliable leather Food Meat tenderization; modification of wheat gluten; cheese-making; preparation of soy hydrolysates; improves extensibility and strength of dough Protein hydrolysate; cheese; soy sauce and soy products; meat products; enhanced dough volume Waste management Solubilize (degrade) proteinaceous wastes Additives in feeds and fertilizer Biomedicine Antimicrobial agents, anti-inflammatory agents, anti-cancer agents, anti-tumor agents, thrombolytic agents Therapeutics and pharmaceuticals Photographic Recover silver from X-ray films Secondary silver Textile Silk degumming High strength silk fibre; sericin powder Detergent industry

-

The detergent industry forms the largest industrial application of enzymes, accounting for 25%−30% of the total worldwide markets for enzymes[194]. Microbial proteases are dominant in commercial applications, with a substantial share of the market utilized in laundry detergent[27,195]. They are used as additives in detergent formulations for the removal of proteinaceous stains from clothes, resulting from food, blood, and other body secretions as well as to improve washing performance in domestic laundry and cleaning of contact lenses or dentures[19,196,197]. The use of proteases in detergent products offers colossal advantages since these products contain fewer bleaching agents and phosphates, thus, rendering beneficial effects on public and environmental health[198,199]. Generally, an ideal protease used as detergent additives should have a long shelf life as well as high activity and stability over a wide range of pH and temperature[48]. In addition, the enzymes should be efficient at low amounts and compatible with various detergent components along with chelating and oxidizing agents[19,27,61]. This is noteworthy because proteases from Bacillus cereus, Bacillus pumilus CBS, Bacillus licheniformis, Bacillus brevis, and Bacillus subtilis AG-1 have been reported to exhibit robust detergent compatibility in the presence of calcium chloride and glycine (used as stabilizers)[200−204].

Leather industry

-

Leather processing involves a series of stages including, curing, soaking, liming, dehairing, bating, pickling, degreasing, and tanning[205,206]. Conventional approaches of leather processing involving the use of hazardous chemicals such as sodium sulfide, lime, and amines generate severe health hazards and environmental pollution[207,208]. As a result, the use of biodegradable enzymes as substitutes for chemicals has proved successful in enhancing leather quality and reducing environmental pollution[19,209−211]. Enzymatic dehairing processes are attractive for preserving the hair and contribute to a fall in the organic load discharged into effluent. In addition, it minimizes or eliminates the dependence on toxic chemicals[212,213]. Due to their elastolytic and keratinolytic activity, proteases are employed for selective breakdown of non-collagenous constituents of the skin and for elimination of non-fibrillar proteins during soaking and bating, thus producing soft, supple, and pliable leather[69]. Furthermore, microbial proteases are employed for quick absorption of water thus, reducing soaking time[214]. Proteases from Bacillus sp. with keratinolytic activity have been reported for dehairing properties[29,215−217].

Food industry

-

In the food industry, proteases are usually employed for a variety of purposes, including cheesemaking, baking, the preparation of soya hydrolysates, meat tenderization, etc.[61]. The catalytic function of these enzymes is utilized in the preparation of high nutritional value protein hydrolysate, used as components of dietetic and health products; in infant formulae and clinical nutritional supplements, and as flavoring agents[24,46,218]. However, the bitter taste of protein hydrolysate formed a crucial barrier to its use in food and health care products. Therefore, proteases (carboxypeptidases A) have a high specificity for debittering protein hydrolysates. A key application of protease in the dairy industry is in cheese manufacturing, where the primary role of the enzymes is to hydrolyze specific peptides to generate casein and macropeptides[19,219,220]. In addition, proteases play a significant role in meat tenderization (e.g., beef) since they possess the potential to hydrolyze connective tissue proteins as well as muscle fiber proteins[27,221]. Endo- and exoproteinases are used in the baking industry to modify wheat gluten. The addition of proteases reduces the mixing time, improves extensibility and strength of dough, and results in enhanced loaf volume[19,222]. Proteases are also employed in the processing of soy sauce and soy products and in the enzymatic synthesis of aspartame (sweetening agent)[61,223].

Waste management

-

Proteases are used in the treatment of waste from various food processing industries and household activities[224]. These enzymes solubilize proteinaceous wastes via a multistep process for the recovery of liquid concentrates or dry solids of nutritional value for fish or livestock[225,226]. This is achieved by initial adsorption of the enzyme on the solid substrates followed by cleavage of polypeptide chain that is loosely bound to the surface. Thereafter, the solubilization of the more compact core occurs at a slower rate, depending on the diffusion of the enzyme surface active sites and core particles[227]. Enzymatic degradation of waste using proteases with keratinolytic activity is an attractive method[228,229]. Among microbial species, some members of the genus Bacillus are regarded as keratinase producers for feather degradation[230−233]. Enzymatic treatment of waste feathers from poultry slaughterhouses using protease from Bacillus subtilis has been reported[234]. Pretreatment with NaOH, mechanical disintegration, and enzymatic hydrolysis resulted in complete solubilization of the feathers, releasing a heavy, grayish powder with high protein content that could be used as an additive in feeds, fertilizers, etc. In addition, proteases with keratinolytic activity are used for the degradation of waste material in household refuse, and as a depilatory agent for the removal of hairs in bathtub drains which cause unpleasant odors[235−237].

Biomedicine

-

The diversity and specificity of proteases are utilized for the development of a broad range of therapeutic agents[223]. The involvement of these biocatalysts in the life cycle of pathogens characterizes them as a possible target for the development of antimicrobial agents against acute diseases[238]. For instance, elastoterase from Bacillus subtilis 316M immobilized on a bandage is used for the treatment of burns, purulent wounds, carbuncles, furuncles, and deep abscesses[239]. In addition, fibrinolytic protease is employed as a thrombolytic agent[240]. Serratiopeptidase, a protease produced by Serratia sp., is the most effective protease for treatment of acute and chronic inflammation and as an antimicrobial agent against acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), hepatitis B and C etc.[241,242]. In addition, serrazime, a proteolytic enzyme from Aspergillus sp. is utilized in dietary supplements as anti-inflammatory; cardiovascular or immune support[243]. Collagenases with alkaline protease activity are used for the preparation of slow-release dosage forms as well as in wound healing, the treatment of sciatica in herniated intervertebral discs, the treatment of retained placenta, and as a pretreatment for enhancing adenovirus-mediated cancer gene therapy[244,245]. Furthermore, lysostaphin, an extracellular protease from Staphylococcus simulans exhibited therapeutic activity against a broad spectrum of infections such as endocarditis, abscesses, septicaemia, and septic emboli, caused by Staphylococcus sp. This is achieved by secreting toxins, which cause puncture of the Staphylococcal cell wall, resulting in cell death[246−248]. More so, L-asparaginase from Escherichia coli and Erwinia chrysanthemi is used for the treatment of malignant tumours, lymphoblastic lymphoma, and lymphoblastic leukaemia in children[238,249]. Streptokinases (Streptococcus sp.) and collagenases (Clostridium histolyticum and Aspergillus oryzae) are employed as therapeutic agents against myocardial infection, coronary thrombosis; supplements in the treatment of lytic enzyme deficiency syndromes, burns, and wounds[238]. The cytotoxic nature of several proteases allows the enzymes to be used as efficient antimicrobial agents for clinical purposes[250].

-

Microbial proteases are leading catalysts with a tremendous increase in global demand in the last few decades. They are produced by bacteria, fungi, and yeasts. However, bacterial proteases are mostly preferred due to their high catalytic activity and stability at broad pH and temperature ranges. The production of these biocatalysts is influenced by nutritional and physicochemical parameters. Insolubilization of the purified enzymes in appropriate support materials is a very useful approach for efficient bicatalysis. It enhances the recovery and reuse potential of the enzymes, thus reducing overall costs. The robust versatility and specificity of microbial proteases warrant their employability as green catalysts in the detergent, food, leather, and pharmaceutical industries, as well as in waste management.

Due to the growing and multi-functional applications of microbial proteases, further discovery and engineering of novel enzymes with robust catalytic efficiency suitable for commercial applications should be carried out through metagenomics, site-directed mutagenesis, or in vitro evolutionary modification of protein primary structures. More research should be carried out on the use of microbial proteases as an alternative to classical antibiotics for the development of novel therapeutic agents against emerging infectious diseases.

The financial support of the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2023 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Adetunji AI, Olaitan MO, Erasmus M, Olaniran AO. 2023. Microbial proteases: A next generation green catalyst for industrial, environmental and biomedical sustainability. Food Materials Research 3:12 doi: 10.48130/FMR-2023-0012

Microbial proteases: A next generation green catalyst for industrial, environmental and biomedical sustainability

- Received: 15 February 2023

- Accepted: 22 May 2023

- Published online: 07 July 2023

Abstract: Proteases are among the most important classes of hydrolytic enzymes and occupy a key position due to their applicability in both physiological and commercial fields. They are essential constituents of all forms of life, including plants, animals, and microorganisms. However, microorganisms represent an attractive source for protease secretion due to their high productivity in a relatively short time and limited space requirements for cultivation, amongst others. Microbial proteases are produced by submerged or solid-state fermentation process during post-exponential or stationary growth phase. The production of these biocatalysts by microbes is influenced by nutritional and physicochemical parameters. Downstream recovery of high-value enzyme products from culture supernatant using suitable techniques is imperative prior to further use of the biocatalysts. Immobilization of these enzymes in appropriate matrices permits reusability, reclamation, enhanced stability and cost-effectiveness of the biocatalysts. The catalytic properties of microbial proteases help in the discovery of enzymes with high activity and stability, over extreme temperatures and pH for utilization in large-scale bioprocesses. This review provides insights into microbial proteases taking cognizance of the bioprocess parameters influencing microbial proteases production coupled with methods employed for protease purification as well as the immobilization and biochemical properties of the biocatalysts for potential biotechnological applications.