-

Tobacco use among youths represents a critical public health challenge, posing both immediate and long-term health consequences. Young smokers face heightened risks of compromised pulmonary function, premature cardiovascular deterioration, and accelerated nicotine dependence development, which may deepen addiction, and reduce future quit success[1]. Therefore, promoting and achieving smoking cessation at an early age is essential for reversing early health damage but also for establishing healthier long-term behavioral patterns and maximizing lifetime wellness.

According to the 2019 National Youth Tobacco Survey in China, 5.9% of secondary school students aged 12–18 reported cigarette use within the preceding 30 d[2]. Among young adults aged 15–24, the 2018 China Adult Tobacco Survey revealed a current smoking prevalence of 18.6%[3]. Despite these concerning figures, there are signs of substantial quit motivation: 74.2% of adolescent current smokers, and 23.6% of young adult smokers had attempted to quit within the past year[2,3]. This demonstrated willingness to cease tobacco use highlights a critical window of opportunity for effective public health intervention.

However, significant gaps remain in translating this motivation into sustained abstinence. Currently, smoking cessation interventions provided by SCCs are largely adapted from protocols developed and validated in adult populations, given the larger evidence base for adult cessation[4]. It remains unclear whether these adult-oriented approaches are equally effective for young smokers, who differ substantially in smoking patterns, social environments, and reasons for tobacco use. Furthermore, key questions persist regarding which demographic, behavioral, and clinical factors predict successful quitting among youth, and young adult SCC attendees.

To address these evidence gaps, this study aimed to evaluate the real-world effectiveness of SCC-delivered interventions among youth smokers in China, and to identify factors associated with successful smoking cessation outcomes in this population. By analyzing data from a multi-center cohort, the aim of the present study it to provide evidence that can inform the development of tailored, effective, and scalable cessation strategies for young tobacco users.

-

The present study was a retrospective cohort study conducted across 385 SCCs in 28 of mainland China's 31 provinces (excluding Beijing, Shandong, and Qinghai due to data limitations), and included youth patients (≤ 24 years of age) who visited SCCs between June 2019 and December 2023. All participating SCCs utilized a unified computer-based data management system specifically designed for smoking cessation care starting in 2019.

Procedures and data source

-

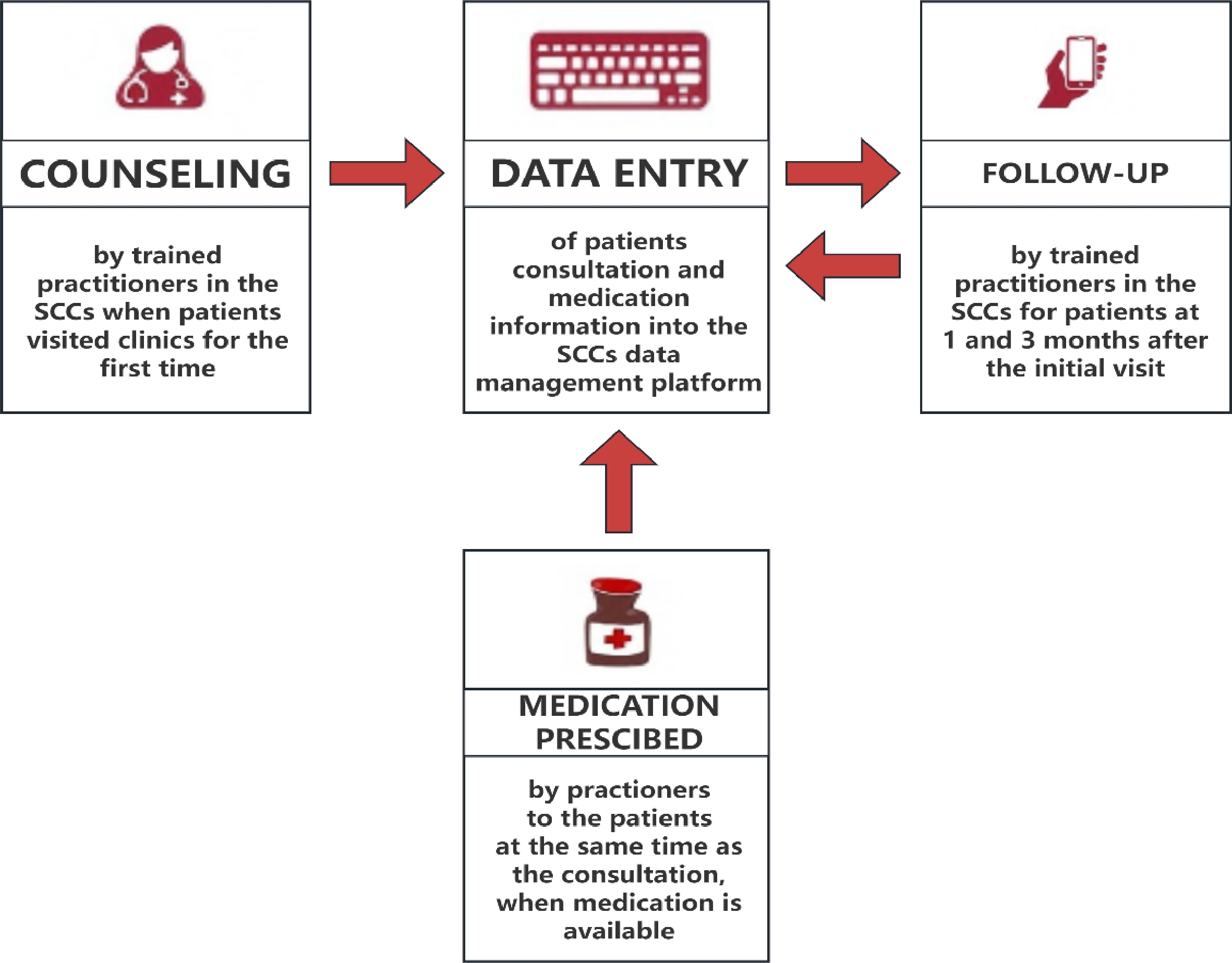

Trained practitioners at each site delivered cessation interventions and conducted structured follow-ups. Patients attending SCCs received structured counseling interventions at three time points: the initial visit, 1-month follow-up, and 3-month follow-up. Smoking cessation interventions comprised three main approaches: counseling alone, counseling combined with first-line medications [Varenicline, Bupropion, and Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT)][5], or counseling combined with traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Counseling was based on the established theoretical frameworks of the 5As (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange follow-up), and the 5Rs (Relevance, Risks, Rewards, Roadblocks, and Repetition), with each session lasting ≥ 10 min[5]. During the initial visit, clinicians prescribed medications based on availability and patient acceptability. During the patient's initial visit, medical staff instruct the patient to take a deep breath and exhale completely into a disposable mouthpiece at a steady, slow pace until the lungs are fully emptied. The results are then read and interpreted, typically measured in parts per million (ppm). A reading of 10 ppm or higher is considered indicative of smoking. Data including patients' demographic characteristics, smoking status, and other relevant information were collected during initial visits and follow-ups and entered into the data management system. The smoking cessation clinic consultation process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Outcome measures

-

Smoking status was assessed through self-report measures. At the 1-month and 3-month follow-up assessments, patients were asked to report their smoking status by answering the question: 'Have you smoked within the past 7 d?' Those who responded 'no' were categorized as abstinent. Individuals lost to follow-up were presumed to be smokers. Inactive occupational status included patients who were students, retired, unemployed, and so on. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) was utilized to measure nicotine dependence degree. Scores of 0–3, 4–6, and ≥ 7 represent low, moderate, and high nicotine dependence, respectively. Patients who were willing to quit within 30 d were considered to have a strong willingness to quit.

Data analysis

-

Demographic characteristics and tobacco use assessments were summarized using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables are reported as means with standard deviations, while categorical variables are summarized as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons were performed using chi-squared tests. Multivariate logistic regression was employed to construct the analytical model. Variable selection was based on preliminary candidate variable sets determined by prior research evidence, and clinical expertise. Univariate analysis (set at a significance level of p < 0.1) was first conducted for initial screening. Variables ultimately included in the multivariate model comprised age, gender, educational attainment, nicotine dependence level, smoking cessation history, intensity of cessation motivation, whether exhaled carbon monoxide monitoring was received, and intervention type. Forward likelihood ratio selection was employed for variable screening. All retained variables demonstrated statistical significance (p < 0.05), or clinical importance. The strength of association between each factor and smoking cessation outcomes was quantified using odds ratios (OR), and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Data were cleaned and analyzed with SPSS (version 28, IBM Corporation, Armonk, USA).

Ethical review

-

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Identification No.: 202214. Approval Date: June 30, 2022. During the initial visit, practitioners thoroughly explained the informed consent process to the patient.

-

Between 2019 and 2023, 3,167 youth patients visited 385 SCCs across 28 PLADs, representing 3.0% of all patients served during this period. The follow-up rates at 1 month and 3 months were 67.7% and 50.2%, respectively. The demographic characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1. Among the participants, 94.7% were male, 91.3% were young adults aged 18–24 years, 54.0% held a college degree, and 61.9% were inactive occupational status. (Table 1)

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and predictors of abstinence rates at 1- and 3-month follow-ups of patients visiting SCCs in China, 2019–2023.

Characteristic Sample PPAR at 1-month PPAR at 3-month N (%) OR (95%CI) p value OR p value Overall abstinent rate 3,167 (100%) 26.5 26.1 Demographic characteristics Age group < 18 276 (8.7%) 1 1 18–24 2,891 (91.3%) 0.895 (0.660–1.213) 0.474 1.127 (0.822–1.543) 0.458 Gender Male 3,000 (94.7%) 1 1 Female 167 (5.3) 1.339 (0.950–1.888) 0.095 1.035 (0.725–1.476) 0.851 Education status Primary school or below 80 (2.5%) 1 1 High school 1,378 (43.5%) 1.281 (0.710–2.310) 0.411 1.056 (0.603–1.849) 0.849 College degree or above 1,709 (54.0%) 1.390 (0.771–2.505) 0.273 1.297 (0.742–2.268) 0.361 Occupational status Active 1,206 (38.1%) 1 1 Inactive 1,961 (61.9%) 0.891 (0.752–1.056) 0.183 1.074 (0.906–1.273) 0.408 Smoking status Nicotine dependence group (score) 0–3 (low) 1,951 (61.6%) 1 1 4–6 (moderate) 913 (28.8%) 0.936 (0.778–1.126) 0.484 1.089 (0.907–1.308) 0.359 ≥ 7 (high) 303 (9.6%) 0.488 (0.351–0.680) < 0.001 0.684 (0.500–0.935) 0.017 Past-year quit attempts None 1,942 (61.3%) 1 1 1–5 times 1,097 (34.6%) 0.763 (0.640–0.910) 0.003 0.879 (0.739–1.045) 0.144 > 5 times 128 (4.0%) 0.825 (0.537–1.268) 0.380 0.698 (0.447–1.090) 0.114 Willingness to quit Within 30 d 2,402 (75.8%) 1 1 30 d later 765 (24.2%) 0.398 (0.317–0.500) <0.001 0.457 (0.367–0.569) < 0.001 Intervention Exhaled carbon monoxide test No 2,008 (63.4%) 1 1 Yes 1,159 (36.6%) 1.401 (1.182–1.660) < 0.001 1.212 (1.023–1.437) 0.027 Intervention methods Counseling 2,771 (87.5%) 1 1 First-line medication and counseling 289 (9.1%) 1.354 (1.025–1.788) 0.033 1.094 (0.824–1.451) 0.535 TCM and counseling 107 (3.4%) 0.821 (0.511–1.320) 0.416 0.902 (0.569–1.429) 0.660 Regarding smoking characteristics, 61.6% demonstrated low nicotine dependence, while 38.6% of patients had a quit attempt at least once in the past, and 75.8% expressed a strong intention to quit. Only 36.6% of patients underwent ECO testing, and merely 9.1% received the recommended combination of behavioral counseling with first-line smoking cessation medications. The self-reported 7-d PPAR at 1-month and 3-month follow-up were 26.5% and 26.1%, respectively (Table 1).

The logistic regression analysis revealed that at both 1-month and 3-month follow-up assessments, patients with high nicotine dependence (OR = 0.488; 95% CI: 0.351−0.680; OR = 0.684; 95% CI: 0.500−0.935, respectively) and those with weak willingness to quit (OR = 0.398; 95% CI: 0.317−0.500; OR = 0.457; 95% CI: 0.367−0.569, respectively) demonstrated significantly lower quit rates. Conversely, patients who underwent exhaled carbon monoxide (ECO) testing (OR = 1.401; 95% CI: 1.182−1.660; OR = 1.212; 95% CI: 1.023−1.437, respectively) showed significantly higher abstinence rates.

Additionally, at the 1-month follow-up, patients with 1−5 previous quit attempts in the past years (OR = 0.763; 95% CI: 0.640−0.910) were less likely to achieve abstinence, while those prescribed first-line cessation medications (OR = 1.354; 95% CI: 1.025−1.788) demonstrated improved quit rates. (Table 1)

-

Smoking cessation clinic interventions demonstrate effectiveness among young smokers compared with the general population study[6], the young patients exhibited higher PPAR at both follow-up—26.5% at 1 month, and 26.1% at 3 months—surpassing the general population rates of 26.2% and 23.5%, respectively. The observed difference may stem from distinct nicotine dependence: young smokers predominantly show low dependence (61.6%), reflecting their experimental-to-habitual transition phase, compared to the general population's 37.6% prevalence of low dependence. This dependence gradient likely contributes to differential relapse risks.

Research on youth smoking cessation shows considerable variation internationally. For example, in 2020, the American Academy of Pediatrics' Center for Pediatric Research implemented a 5As counseling intervention targeting adolescent tobacco users. The program yielded smoking cessation success rates of 57% and 46% at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, respectively. It showed that professional smoking cessation interventions have demonstrated significant efficacy in supporting smoking cessation among young smokers[7]. The present study was consistent with research carried out in Hong Kong from 2016 to 2019, which also employed the 5As counseling model for smoking cessation among young smokers under age 25, reported a 7-d PPAR of 34.2% at the 6-month follow-up[8]. An analysis of research conducted between the 1980s and 2000 revealed that interventions using motivation enhancement or contingency-based reinforcement had 19% and 17% quit rates, respectively[9]. The relatively low smoking cessation rates observed may be attributed to the fact that cessation interventions were not yet fully developed at the time.

According to the model of behavior change, the duration for which smokers express a desire to quit reflects distinct stages within their smoking cessation journey[10]. This model categorizes the process into five sequential stages: pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. Individuals who plan to quit smoking within the next 30 d were classified as being in the preparation stage, which signifies a strong commitment to change and an imminent intention to undertake quitting actions. This study indicates that 75.8% of patients expressed a desire to quit smoking within one month, suggesting that the majority of young smokers attending smoking cessation clinics possess a strong motivation to quit. And it also confirmed that youth smokers with stronger quit intention demonstrate significantly higher cessation rates, consistent with patterns observed among the general population[6].

Exhaled carbon monoxide (ECO) serves as a biological marker for smoking, with its concentration directly reflecting an individual's recent smoking status. A 2023 study conducted among adult patients at SCCs in China[11] demonstrated that regular ECO testing can enhance participants' motivation to quit and improve smoking cessation rates. This study further supports the utility of ECO monitoring in supporting quit among young smokers. It may be because visual evidence of carbon monoxide accumulation enhances motivation and increases the likelihood of quitting.

Previous research has demonstrated the efficacy of pharmacotherapies—such as varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine replacement therapy—in supporting smoking cessation among adolescents[12,13]. Although combining first-line pharmacotherapy with behavioral counseling significantly enhances smoking cessation outcomes[14], current clinical guidelines do not recommend these medications for adolescents[5]. In this study, underage participants (< 18 years old) represented only 8.7% of the total participants, meaning the majority of participents were appropriate for first-line pharmacotherapy. However, only 9.1% of patients actually received these medications. This underutilization may be attributed to financial barriers, as these treatments are expensive and not covered by health insurance. Beyond economic considerations, the lower level of nicotine dependence among young smokers may also influence practitioners' decisions to prescribe medication for them. Furthermore, in actual clinical practice, SCCs often employ similar intervention protocols for minors and young adult smokers, reflecting current gaps in training for differentiated interventions tailored to smokers of different age groups.

Although smoking cessation at a young age yields greater health benefits[14,15], and evidence demonstrates that young smokers attempt to quit more frequently[2,3], their utilization of cessation clinics remains disproportionately low relative to their representation in the smoking population[3]. This disparity suggests that young smokers significantly underutilize clinic-based cessation services. To enhance smoking cessation among young people, it is crucial to identify which motivational strategies are effective across different subgroups of young smokers. One key barrier may be a simple lack of awareness of available cessation services[16]. Therefore, it is important to enhance targeted awareness campaigns for young smokers. Furthermore, conventional cessation interventions often fail to align with the values and communication preferences of young populations. This also explains why the loss rate is relatively high. Research indicates that existing services are perceived as unattractive by youths, making recruitment and engagement particularly challenging[17,18]. Studies revealed a stronger preference for digital interventions—including internet-based programs and social media support were more attractive for youths[19]. These findings underscore the urgent need for tailored smoking cessation strategies that align with the technological preferences and communication patterns of young smokers.

A limitation of this study is that smoking status and cessation were determined by self-report without laboratory confirmation, which may introduce reporting bias. Influenced by our cultural context, female smokers are less likely to seek smoking cessation clinics, resulting in a predominantly male sample in this study. This limitation may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other population subgroups. Additionally, the quality of smoking cessation interventions across 385 clinics may vary, particularly given that counseling is provided by practitioners with differing training backgrounds and varying levels of program adherence, thereby influencing the study findings.

-

This study confirms the effectiveness of SCC interventions for young smokers, yet reveals low engagement with conventional cessation clinic services. This highlights the imperative to develop innovative, youth-centered cessation programs, that combine clinical efficacy with appealing delivery formats to better reach this population. In addition, it is recommended to develop differentiated treatment plans for adolescent and young adult smokers, and to enhance standardized training for healthcare professionals in smoking cessation clinics.

We appreciate the valuable feedback and constructive critique from reviewers and editors. This study did not receive any specific funding from any funding agency (commercial or nonprofit).

-

The Ethical Review Committee of Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention has reviewed the project. It is recognized that the right and the welfare of the subject are adequately protected; the potential risks are outweighed by potential benefits.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization and methodology: Xie L; formal analysis and writing: Xie L; review and revision: Xiao L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of themanuscript.

-

The data will not be made public as it contains information that may compromise the privacy of research participants. The results of the data analysis have been presented in this paper.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xie L, Xiao L. 2025. Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among youth smokers of smoking cessation clinics in China, 2019–2023. Journal of Smoking Cessation 20: e011 doi: 10.48130/jsc-0025-0011

Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among youth smokers of smoking cessation clinics in China, 2019–2023

- Received: 03 September 2025

- Revised: 25 September 2025

- Accepted: 05 November 2025

- Published online: 28 November 2025

Abstract: The use of tobacco among young people represents a substantial challenge to public health systems, and early cessation is crucial for ensuring long-term health. This study assessed smoking cessation outcomes and associated influencing factors among youth smokers (≤ 24 years old) seeking treatment at smoking cessation clinics (SCCs) in China. Data was analyzed from patients who visited SCCs between June 2019 and December 2023 in China. 3,167 youth smokers were included. The self-reported 7-d point prevalence abstinence rates (PPAR) were 26.5% at 1 month, and 26.1% at 3 months. The logistic regression analysis revealed that at both 1-month and 3-month follow-up assessments, patients with high nicotine dependence and those with weak willingness to quit demonstrated significantly lower quit rates. Conversely, patients who underwent exhaled carbon monoxide (ECO) testing showed significantly higher abstinence rates. SCC-based interventions demonstrate effectiveness for youth smokers. Low engagement with cessation clinic services highlights the imperative to develop innovative, youth-centered cessation programs that combine clinical efficacy with appealing delivery formats to better reach this population. Additionally, it is essential to improve smoking cessation awareness campaigns targeting youth smokers.

-

Key words:

- Effectiveness /

- Youth smokers /

- Smoking cessation /

- Risk factors