-

Angiosperms have evolved a unique mode of sexual reproduction known as siphonogamy, in which nonmotile sperm cells are delivered to the ovule via a pollen tube for fertilization[1,2]. This adaptation eliminates the dependency on water for gamete transfer and represents a key evolutionary innovation that facilitated the rapid diversification and widespread colonization of terrestrial habitats by flowering plants[1,3]. A distinctive feature of the pollen tube in most angiosperms is the tight physical association of the two sperm cells with the vegetative nucleus, forming a functional entity termed the male germ unit (MGU). The formation of the MGU is essential for successful double fertilization, as it ensures that the two sperm cells are consistently positioned, along with the vegetative nucleus, close to the apical region of a growing pollen tube. This positioning guarantees their timely release along with the pollen tube's contents to the vicinity of the egg and central cells upon rupture of the pollen tube[3,4]. In contrast, if the sperm cells remain confined within the pollen grain or are located at the rear region of the pollen tube, they may fail to be discharged when the tube bursts, potentially compromising fertilization efficiency. First proposed over four decades ago, the MGU has been traditionally thought to migrate over long distances within the pollen tube through actin cytoskeleton dynamics and myosin-driven cytoplasmic streaming, with microtubules playing a secondary and supportive role[5,6]. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanisms underlying the MGU's assembly and its precise biological functions remain poorly understood[7,8].

A recent advancement in understanding the structural features of the MGU involves the identification of a specialized membrane surrounding the germ cells. Over the past five decades, this structure has been examined in numerous studies; however, because of discrepancies in the reported origins and molecular compositions, it has been assigned multiple names and described with varying characteristics, leading to considerable confusion[9]. In a recent collaborative study, Daisuke Maruyama (Yokohama City University, Japan), Thomas Widiez (CNRS, INRAE, France), and 42 researchers from 34 institutions across 14 countries formally proposed the term "peri-germ cell membrane (PGCM)" to unify its nomenclature[9]. This designation reflects the distinctive "cell-within-a-cell" architecture and highlights this membrane's critical role in maintaining the MGU's integrity. Notably, in the vegetative cell, established plasma membrane markers were shown to not localize to the PGCM, clearly differentiating it from the conventional plasma membrane[9]. Accumulating evidence suggests that the PGCM is not only a passive barrier but a highly specialized membrane structure with unique lipid and protein compositions that is essential for both structural stability and intercellular communication between the vegetative cell and germ cells[9]. By redefining the MGU as a dynamic membrane-dependent functional unit, the PGCM provides a conceptual framework for future investigation into the organization and physiological functions of the MGU.

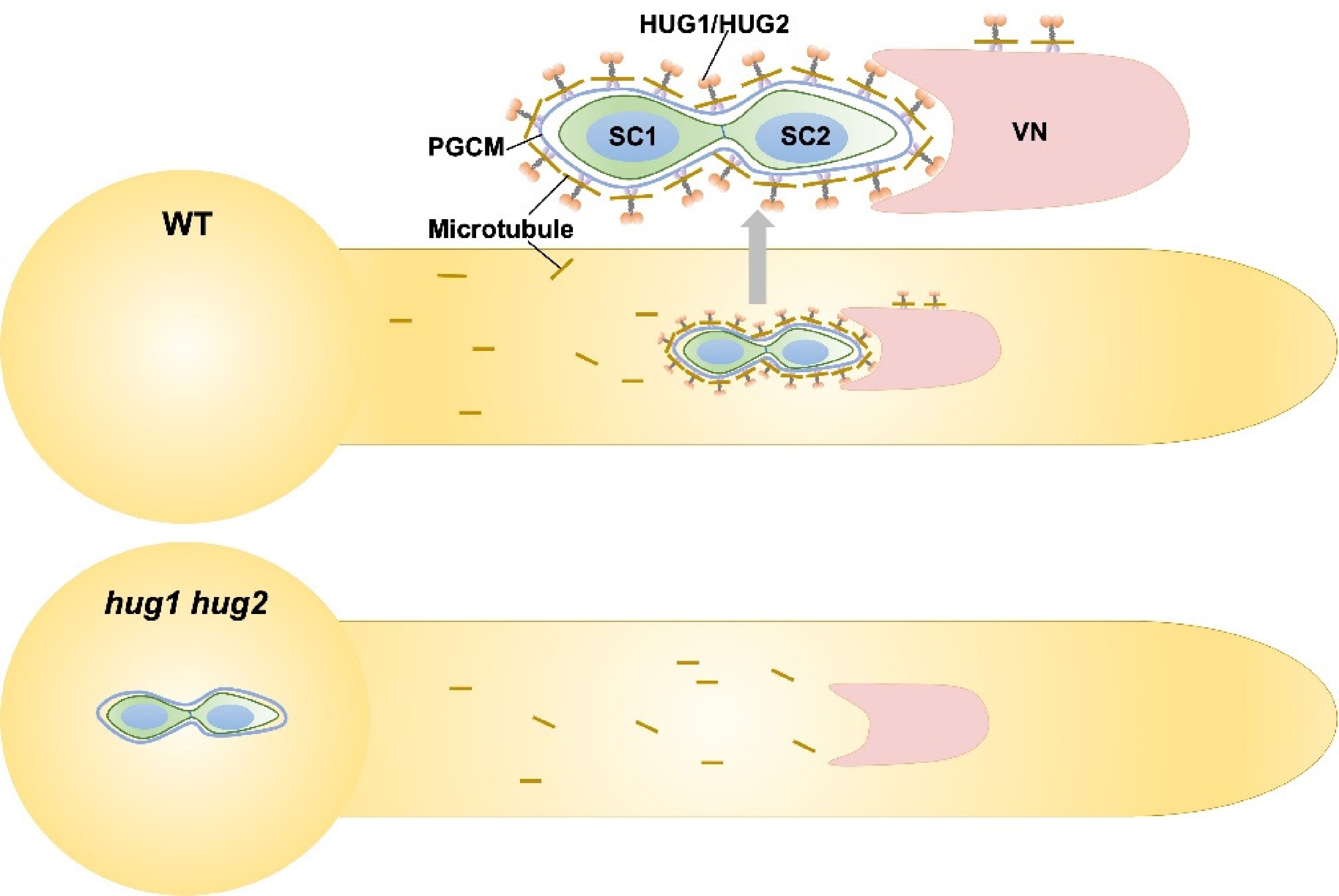

Recently, more significant breakthroughs have been made in elucidating the MGU's assembly mechanism, which greatly enhanced our understanding of the MGU's structure. Two studies by Chang et al. and Yan et al. demonstrated that the microtubules and the associated kinesins play a central role in the directed transport and precise positioning of the MGU[10,11]. Both studies identified two kinesins that are essential for maintaining the physical connection and coordinated movement between the vegetative nucleus and sperm cells. The two kinesins, designated as HUG1 and HUG2, were localized in the vegetative nuclear envelope and outside the PGCM. Genetic and cytological evidence revealed that loss of function in the two kinesins disrupts the connection between the sperm cells and the vegetative nucleus, resulting in the sperm cells being trapped within the pollen grain or at the basal region of the pollen tube. Consequently, the sperm cells fail to be transported to the embryo sac, leading to defective double fertilization and male sterility[10,11] (Fig. 1). Chang et al. also reported that HUG proteins and microtubules formed a unique dual-layer cage surrounding the PGCM, which exhibits greater stability than the dynamic microtubules typically found in the cytoplasm[10]. A more in-depth investigation into the biophysical and biochemical properties of this specialized cage is expected to yield critical insights into the structural basis of the MGU. Although cytoplasmic streaming provides a basic propulsive force resembling a random "flow", the microtubule–kinesin system acts more like a "navigation system" or "stabilizing tether" to ensure the structural integrity of the MGU and guide its precise directed migration in coordination with growth of the pollen tube tip for enabling successful double fertilization. Furthermore, the mechanical forces generated by these motor proteins are likely anchored by and transduced through the PGCM, thereby coordinating the movement of the entire MGU. Collectively, these results highlight that the MGU's assembly, stability, and transport constitute a tightly coordinated process dependent on specific membrane domains and integrated cytoskeletal dynamics during rapid pollen tube elongation.

Figure 1.

Working model of HUG1/2-mediated assembly of the MGU. Two immobile sperm cells (SC) are physically connected to a vegetative nucleus (VN), forming the MGU, which is transported as a single unit to the female gametophyte for fertilization. External to the peri-germ cell membrane (PGCM), a dual-layered cage structure comprising an inner microtubule cage and an outer HUG protein cage is required for the assembly of the MGU. Short brown lines indicate the microtubules.

This recent progress has significantly advanced our understanding of pollen biology. The MGU must undergo precise assembly and dynamic regulation to function as a coordinated reproductive entity. Both the accurate formation and controlled migration of the MGU within the pollen tube are essential for the final delivery of sperm cells to the ovule and thus for successful fertilization. The intracellular transport system in pollen tubes operates as a collaborative network: actin filaments mediate bulk cytoplasmic streaming, providing general cellular motility, whereas microtubules along with the associated kinesin motors provide precisely targeted delivery of the critical MGU components. This ensures that while actin supports large-scale cytoplasmic dynamics, microtubules provide the spatial accuracy required for the proper localization and function of key structures such as the MGU.

Nevertheless, there are more intriguing scientific questions to be addressed in the future. For instance, how are the establishment of the PGCM and the recruitment of kinesins such as HUG1 and HUG2 specifically coordinated after Pollen Mitosis I (PMI)? One plausible model is that the newly formed PGCM serves as a specialized membrane platform, whose unique lipid or protein composition facilitates the formation of anchoring sites for HUG1 and HUG2. Conversely, HUG proteins might actively participate in the final maturation and stabilization of the PGCM's structure by interacting with other scaffold proteins. Deciphering the initial signals and molecular details of this coordinated assembly process will be an important direction for future research. Furthermore, another unresolved puzzle is how the maintenance of the PGCM and its attachment to HUG proteins are coordinated with generative cell division during Pollen Mitosis II (PMII). The division of the generative cell represents a dramatic cellular remodeling event, yet the integrity of the MGU must be maintained during the entire process. This suggests the existence of precise regulatory mechanisms, potentially involving cross-talk between generative cells and the PGCM, to ensure that the supportive structure of PGCM–HUG protein–microtubule can undergo the necessary remodeling without disassembly during cell division. Investigating this coordination is important for understanding how the MGU is inherited as an integrated unit. Moreover, other questions remain, such as what upstream regulatory signals govern this recruitment process, why the vegetative nucleus consistently precedes the sperm cells during the pollen tube's growth, and how this spatial arrangement is established and maintained. Exploring the biological implications of this ordered configuration also deserves further consideration by researchers. Collectively, recent studies have addressed the long-standing question of how the MGU is accurately formed and transported, integrating insights from cytoskeletal mechanics, membrane biology, and intercellular communication into reproductive biology. These advances not only enhance our understanding of the fundamental organization of the MGU but also provide a robust theoretical framework for future agricultural applications, where precise control over reproductive processes may lead to improved crop yields.

HTML

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Programme of China (Grant No. 2022YFF1002100 to S.Z.). We thank Prof. Li-Jia Qu (Peking University) for advice and suggestions.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: draft manuscript preparation, diagram drawing: Liu P, Zhong S. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Liu P, Zhong S. 2026. A unique microtubule–kinesin cage: structural and mechanistic insights into the male germ unit. Seed Biology 5: e001 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0028 |