-

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.), a key root crop in the Caribbean from the Convolvulaceae family, stands as the seventh most crucial globally, after wheat, rice, maize, potato, barley, and cassava, in annual production among tropical foods[1]. At present, sweet potatoes are cultivated in tropical regions as well as in temperate zones with warmer climates[2]. Asia stands as the foremost producer globally, yielding over 125 million tons of fresh roots annually[3]. China is said to produce over 100 million tons, constituting 85% of global sweet potato production[4]. African farmers yield approximately 7 million tons of sweet potatoes each year, with the majority intended for human consumption[5]. Sweet potato is both a primary and secondary food crop in numerous sub-Saharan African countries, including Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, and other East African societies[6]. On average, annual per capita consumption of fresh roots in Africa is around 9−10 kg, with Rwanda reporting 160 kg and Burundi exceeding 100 kg[7]. The sweet potato root serves as a staple, offering a wealth of nutrients including beta-carotene, vitamins, iron, calcium, magnesium, manganese, and potassium crucial for health, while also providing significant dietary fiber, particularly when consumed with its peel[8]. Sweet potato roots, with their varied tastes, textures, and colors like white, cream, yellow, orange, and purple, are rich in nutrients and can help boost vitamin A intake, potentially addressing deficiencies in developing nations like Ethiopia[9]. Currently, malnutrition is becoming a cross-cutting issue worldwide and it is reported to start before birth, endures into adolescence and adult life, and can also span to generations[10]. Stunting and micronutrient shortage are cited as some of the foremost causes of premature death and disease in Ethiopia[11]. Undernourishment is indicated to upset both the mental and physical growth of survivors, which in turn affect the performance and economic evolution[12]. In developing countries, over one million deaths are recorded each year among children under the age of five due to issues related to malnutrition[13]. For example, only 14% of Ethiopian children partake in a varied diet, making it one of the least diverse diets among those in Sub-Saharan Africa[14, 15]. Consequently, in Ethiopia, the consumption of foods rich in vitamin A or iron remains low among young children, with only 39% of children aged 6−23 months were reported to have consumed vitamin A-rich foods and 24% iron-rich items in the preceding 24 h[16]. In Ethiopia, monotonous diets contribute to high rates of stunting, wasting, and Vitamin A deficiency (VAD), affecting around 37% severely stunted, 12% severely wasted, and 47% deficient in Vitamin A among young children[17]. Moreover, 22% of women of reproductive age are under nourished in Ethiopia[18]. On the other hand, the consumption and utilization of sweet potato as a normal item or fortified form were abandoned in Ethiopia. The societal awareness and government commitment to employ sweet potato in the wider community is very low in the country. Despite Ethiopia being a highly affected country by extensive malnutrition problems, the cultivation and consumption of sweet potato crops are not largely practiced by different stakeholders including the government. Moreover, the potential and nutritional values of the crop to overcome malnutrition complications is not adequately addressed in Ethiopia. Thus, the aim of this work was to review the potential contribution of sweet potato in Ethiopia towards alleviating malnutrition.

-

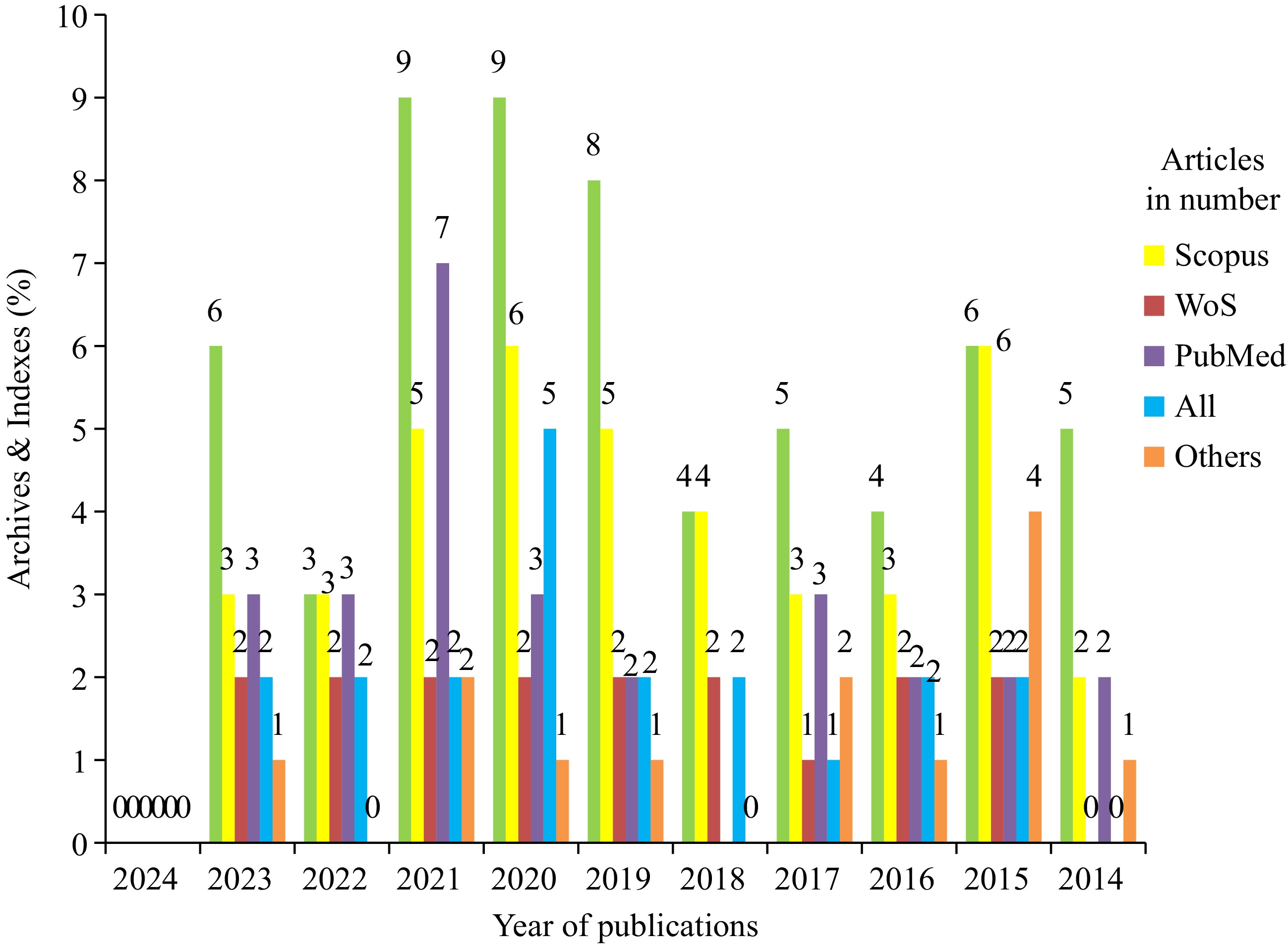

In this review of the literature, diverse approaches were employed. Respected journals sourced from Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed databases were referenced. The selection criteria largely targeted articles released post-2019, while omitting pertinent data and books (Fig. 1). So, the review materials were selected spanning the years, led by indexes and respective protocols. Overall, more than 80 papers were reviewed to write this article. Of which 40 articles (47%), 17 articles (20%), 27 articles (31.7%), 20 articles (23.5%), and 13 articles (15.29%) were sourced from Scopus, WoS, PubMed, All, and other databases (between 2014 to 2023) respectively. However, the year-wise-scrutiny shows that most of the articles were published between 2019 and 2023 (Fig. 1). In addition, the majority of the reviewed papers determined that sweet potato can be a potential solution for nutritional challenges globally including sub-Saharan areas such as Ethiopia.

-

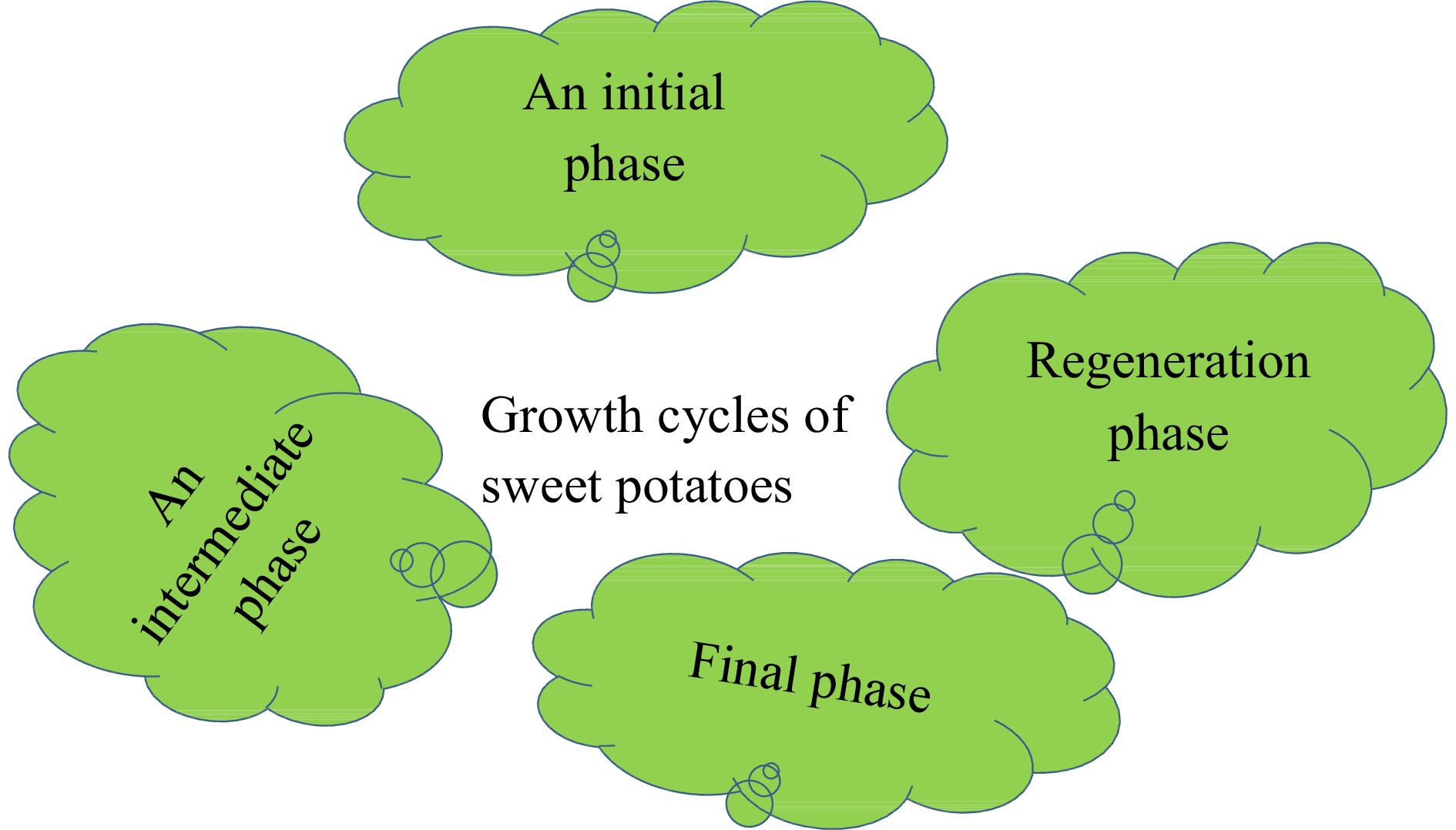

According to reports, the sweet potato is said to have originated in Mexico and Venezuela[19]. The Convolvulaceae family includes climbing sweet potato species found in diverse habitats across temperate and tropical regions, characterized by long trailing stems[20]. Sweet potatoes have alternate and simple leaves, with bisexual flowers characterized by five free sepals, five fused petals, five stamens, all fused at the base of the corolla tube[21]. The elongated and slender stems that extend across the surface are noted for generating roots wherever nodes come into contact with the soil[22]. The stem length of sweet potato can vary between 1 and 5 m, contingent upon its genotype[23]. The sweet potato is also known for generating a broad, fibrous network of roots that originates from the nodes of the cutting[24]. Trailing stems, upon soil contact, develop roots at nodes, producing five to ten storage roots per plant by thickening adventitious roots below the basal stem level[24]. Sweet potato yield depends on growing period length, influenced by foliage characteristics, storage root growth patterns, and their size and shape, crucial for breeders[25]. Sweet potato growth involves four phases: rapid root and vine growth, followed by storage root bulking, and finally, regeneration through sprouting for new plant growth[26] (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, there are also instances of intersections among the four stages of growth when the duration significantly fluctuates, contingent upon the cultivar and environmental conditions.

Sweet potatoes, a versatile staple crop grown globally, thrive in diverse climates with their adaptability to various soils and low water needs[21]. Globally, with over 5,000 varieties ranging in color and texture, sweet potatoes such as Beauregard, Jewel, and Garnet offers diverse flavors and textures[27].

Integral to Africa's food security and agriculture, sweet potatoes thrive in regions vulnerable to drought and famine, boasting diverse cultivars distinguished by variations in color, shape, and taste[28]. Sweet potatoes play a crucial role in traditional cuisine across countries like Nigeria, Ghana, and Uganda, used in various dishes from soups to snacks, while African farmers employ innovative planting techniques like intercropping and ridge/mound systems to maximize space and soil fertility[8].

Ethiopia, known for its agricultural potential, stands as a leading producer of sweet potatoes in Africa, cultivating diverse varieties, including indigenous landraces preserved through generations[29]. Sweet potatoes are cultivated across diverse agroecological zones in Ethiopia, utilizing methods like vine cuttings, slips, and tubers, with ongoing initiatives to improve cultivation techniques, bolstering food security and rural livelihoods[30].

-

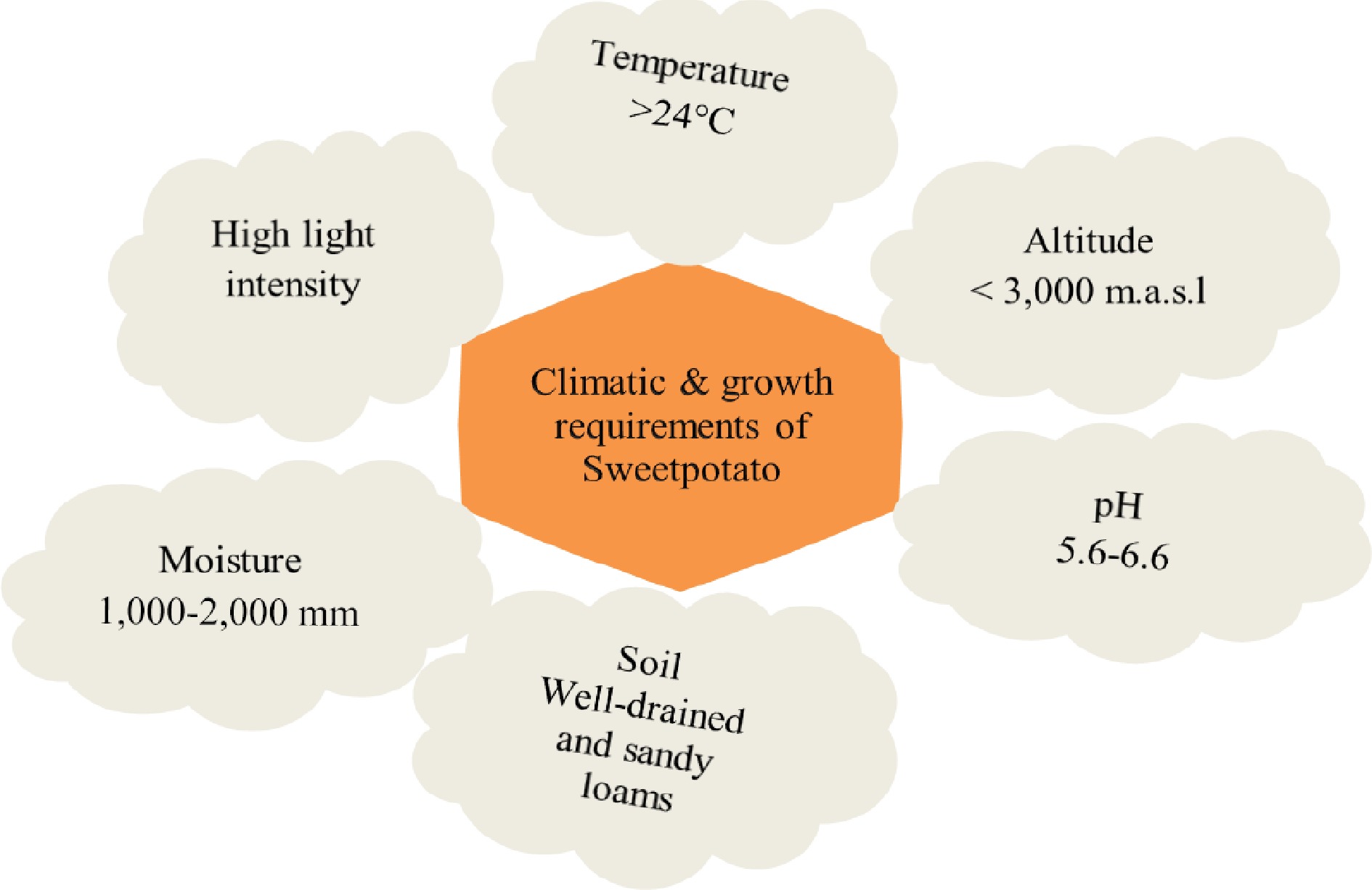

It's been noted that sweet potatoes thrive in sunny conditions, performing at their peak when exposed to high light intensity[31]. It has been observed that when intercropped with perennials, its performance is poor, with day length identified as influencing both flowering and the storage roots directly[32]. The greatest level of light intensity was reported to stimulate the generation of a greater quantity of storage roots, along with an elevation in the dry weight of fibrous roots and overall foliage[33]. Sweet potatoes thrive as a warm-weather crop across a broad range from 40° N to 32° S and from sea level to elevations of 3,000 m in the tropics (Fig. 3), with optimal growth above 24 °C and hindrance below 10 °C[31]. The frost-sensitive plant thrives in regions without frost for 4−6 months, while sweet potatoes excel in storage root weight with constant soil temperatures of 30 °C and nighttime air temperatures of 25 °C[34]. A specific type of sweet potato cultivar is said to experience significant yield improvements with only a slight increase in essential nutrients[35]. Despite limited foliage, plants deficient in nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, sulfur, magnesium, calcium, and iron show symptoms like impaired storage root formation, with recommended nitrogen fertilizers ranging between 30 and 90 kg N/ha[36]. The exportation of nutrients is influenced by crop yield and the distribution of both foliage and storage roots, with nitrogen abundance favoring foliage development to enhance carbohydrate supply[37]. Potassium is recognized as essential for optimal storage root development, with light, dry, compact, and waterlogged soils high in nitrogen being identified as promoting lignification and hindering storage root growth[38]. On the other hand, it has been observed that dark environments rich in potassium, well-ventilated soil conditions, and cooler temperatures contribute positively to growth enhancement[39]. Generally, sweet potatoes thrive in soils with a pH of 5.6−6.6 (Fig. 3), with high-quality tubers being best produced on fertile, well-drained, sandy loams[40]. Rainfall requirements vary by location, evaporation rates, and cultivar characteristics, with adequate water supply (1,000−2,000 mm) crucial for optimal storage root development, but excess water can hinder aeration[41]. As the storage root displaces soil by compressing it, it is suggested that this compression may hinder the development of storage roots by reducing the physical resistance of the soil[42]. Therefore, the rise in root weight is said to rely on leaf photosynthesis (source effect) and the movement of nutrients from the leaves to the root system (sink strength)[43].

-

Cultivating and promoting sweet potatoes in Ethiopia holds significant potential for addressing food security challenges, particularly in regions prone to drought and poor soil conditions (Table 1). Promoting sweet potatoes in Ethiopia offers a dual benefit: their resilience to climate challenges aids farmers, while their nutritional richness addresses malnutrition and improves public health.

Table 1. Importance of cultivating and promoting sweet potatoes in Ethiopia.

Advancing sweet potato cultivation and the descriptors in Ethiopia Ref. Enhancing food security Cultivating sweet potatoes, a rich source of essential vitamins and minerals, can help address food security challenges in Ethiopia by enhancing nutritional intake. [9] Diversification of diets Integrating sweet potatoes into diets diversifies nutrition, potentially mitigating malnutrition and associated health concerns. [44] Climate resilience Promoting the cultivation of resilient sweet potatoes in diverse Ethiopian regions can enhance climate change resilience. [45] Economic opportunities Cultivating sweet potatoes can generate income for rural farmers, especially where agriculture is predominant. [46] Soil health improvement Sweet potatoes enhance soil health by reducing erosion and boosting fertility through their root systems. [47] Livestock feed Utilizing sweet potato foliage and vines as livestock feed enhances animal health and productivity through their rich nutritional content. [48] Sustainable agriculture Sweet potato farming promotes sustainable practices by reducing reliance on chemicals and embracing agroecology. [49] Cultural significance Promoting sweet potato cultivation in Ethiopia preserves cultural heritage and boosts nutrition. [50] Market potential Promoting sweet potato cultivation meets rising demand, boosting agricultural incomes and exports. [46] Health benefits Sweet potatoes, rich in nutrients like vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, may enhance immunity and reduce chronic disease risks. [51] -

Sweet potato is documented that sweet potatoes are cultivated across a wide geographic range, spanning from 40° north to 32° south latitude globally, and are grown in over 114 countries[52]. According to reports in 2014, global sweet potato production totaled approximately 106.60 million metric tons (MMT), with Africa contributing roughly 21% of this production[33]. In 2014, Ethiopia contributed 2.7 million metric tons (MMT) of sweet potatoes with an average yield of 8.1 tons per hectare, while the global average yield for sweet potatoes stood at approximately 14 tons per hectare[33]. In Africa, sweet potato yields average 4.7 metric tons per hectare, significantly lower than the 20−26 metric tons per hectare in China, Japan, and the United States; however, South Africa has achieved yields of 40−50 tons per hectare under superior management, with variations attributed to factors such as planting material quality and crop management practices[53]. Despite Ethiopia's favorable conditions for sweet potato cultivation, including climate and soil suitability, production and consumption gaps persist, while sweet potato holds importance in various African nations bordering the Great Lakes and in West Africa[54]. In Nigeria and Ghana, sweet potato is considered the fourth essential root and tuber crop, following cassava, yam, and taro, while in Tanzania, Uganda, Mozambique, and Malawi, it is regarded as the second most significant root crop after cassava.

-

Despite achievements, Ethiopia still grapples with food and nutrition security, marked by inadequate food supply, lack of nutrition, and high rates of stunting (40%), wasting (9%), and underweight (27%) among children aged 6 to 59 months[55]. Ethiopia's malnutrition issue primarily stems from inadequate intake of four essential vitamins: vitamin A, zinc, iodine, and iron[56]. In Ethiopia, insufficient calorie intake and vitamin deficiencies contribute to widespread food poverty, underscoring the importance of a national nutrition program promoting vitamin-rich foods like sweet potatoes, with research indicating the need to transition from conventional potato cultivation to address vitamin A deficiency[57]. Sweet potatoes offer significantly higher nutritional value with 107% of the daily recommended intake of Vitamin A, whereas regular potatoes contain only 0.1%. Moreover, an investigation into food security and nutrition in Ethiopia conducted to evaluate the 1999-2000 food security status and relief efforts, and to assess the necessity for a national food and nutrition policy, highlighted the requirement for sustainable investments to enhance food security and eliminate famine[58]. In Ethiopia, advocating for a national food and nutrition policy underscores the need to address acute malnutrition, wasting, and stunting alongside relief efforts and underlying famine factors.

-

In Africa, sweet potato is dubbed the 'crop of the poor', cultivated primarily by women at a small scale for subsistence, highlighting its economic significance globally[59]. Additionally, Sub-Saharan African farmers respond to dwindling cultivable land due to population growth by favoring root and tuber crops, which offer higher yields per unit area than grains[60]. Sweet potato is viewed as a low-labor and low-risk crop, offering support to families affected by illnesses like HIV/AIDS by reducing care needs and resource losses[61]. In Sub-Saharan Africa, sweet potato cultivation is said to alleviate poverty, stimulate cash flow, mitigate food insecurity, and preserve ecosystems[62]. Africa's urbanization is progressing swiftly, with projections suggesting that by 2030, the continent will be home to more than 759 million urban residents[63]. Africa's urbanization and changing food systems are projected to boost demand for fresh sweet potato roots and value-added products due to their recognized nutritional benefits, including high levels of vitamins, minerals, and fiber across all varieties[64]. Orange-fleshed sweet potato varieties are valued for their high beta-carotene content and potential health benefits, serving as alternatives for consumers with grain allergies, while in Eastern and Southern Africa, over 3 million children under 5 suffer from Xerophthalmia, leading to blindness[65]. The lack of vitamin A in children's diets often results in death within months of blindness onset, underscoring the potential of incorporating orange-fleshed sweet potato varieties to address vitamin A deficiency in both children and adults through beta-carotene intake[66]. Moreover, American researchers have recently engineered genetically modified sweet potato plants that produce edible vaccines targeting hepatitis B and the Norwalk virus[67]. Furthermore, sweet potato leaves are recognized for their nutritional value and are commonly consumed as a vegetable dish in various regions globally[68]. Sweet potato is utilized worldwide for various purposes, with all parts of the plant—roots, vines, and young leaves—being consumed as food, fodder for animals, and in traditional medicine[69]. In Asia and Africa, sweet potato leaves are commonly consumed as green vegetables, with nutrient content varying by variety, harvest time, and cooking method, typically containing protein, carbohydrates, fat, fiber, ascorbic acid, and carotene on a dry weight basis[33]. Similarly, sweet potato greens contain high levels of lutein, ranging from 38 to 51 mg/100 g in fresh leaves, surpassing the lutein content found in other vegetables traditionally recognized as rich sources of lutein, such as kale (38 mg/100 g) and spinach (12 mg/100 g)[70]. A health review assessing the benefits of sweet potato suggests that it could enhance insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes, regulate blood pressure, promote digestive health, support eye health, bolster immunity, and reduce inflammation, contributing positively to overall health[71]. Obtaining antioxidants from dietary sources, such as sweet potatoes, may help prevent diseases like cancer, while the fiber content in sweet potatoes aid in preventing constipation and promoting regularity in a healthy digestive tract. A study assessing the use of orange-fleshed sweet potato in complementary foods for infants aged 6−12 months in Ghana found that incorporating it as an ingredient can effectively enhance the vitamin A content of these foods, ensuring a sufficient intake of this essential nutrient[72]. A study conducted in India to assess the Sweet potato Biofortification Priority Index, a strategic tool for scaling up biofortified varieties concluded that β-carotene-rich orange-fleshed sweet potato varieties have the potential to alleviate vitamin A deficiency in rural and tribal regions[73]. Research conducted in San Francisco (USA) determined that soybean is the most effective carrier for fortifying sweet potato flour with legumes, with purple sweet potato flours fortified with 10% soybean exhibiting the highest nutritional properties, including protein (8.65%), lipid (3.02%), and amylose (32.09%)[74].

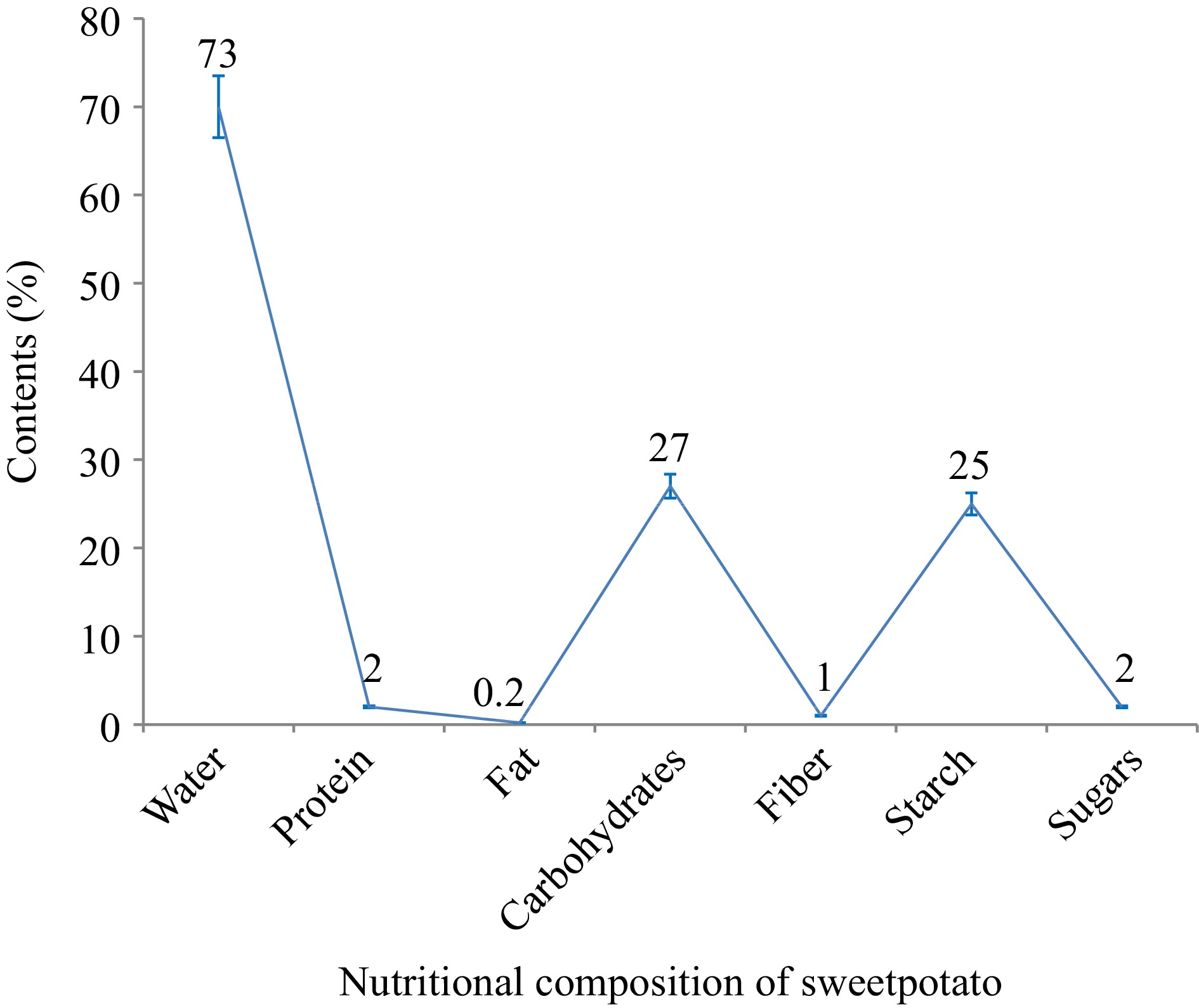

A study conducted in Myanmar to assess the nutrient content and protein extraction from two sweet potato varieties, yellow and purple, revealed that yellow sweet potatoes had higher energy values compared to purple sweet potatoes, and consuming yellow sweet potatoes provided more energy than consuming purple sweet potatoes[75]. A significant large-scale pilot project was carried out between 2006 and 2009 in Mozambique and Uganda, aiming to introduce provitamin-A-rich orange-fleshed sweet potatoes to 24,000 farming households as a means to combat vitamin A deficiency and the project's broader message emphasizing the health benefits of consuming orange-fleshed sweet potatoes was a key factor in encouraging younger children to consume the crop[33, 76]. Typically, sweet potatoes are said to comprise predominantly water (over 70%), carbohydrates (more than 25%), protein (around 2%), fiber (approximately 1%), starch (over 20%), sugars (about 2%), and minimal fat (Fig. 4).

-

Despite Ethiopia's significant potential for large-scale sweet potato production, challenges such as limited access to clean planting materials, lack of improved varieties, sweet potato weevils, insufficient knowledge, poor practices, and underdeveloped markets hinder progress. In sub-Saharan Africa, including Ethiopia, numerous sweet potato plants are affected by viral diseases, and employing clean, healthy planting materials is reported to yield immediate benefits ranging from 30% to 60%[77]. Nevertheless, preserving planting materials during the prolonged dry season poses a challenge, leading to delayed planting, while ample planting materials are being duplicated[78]. Primarily, innovative approaches to vine maintenance, resilient drought-tolerant varieties, small-scale irrigation during dry spells, and the utilization of root sprouting techniques are noted to offer significant amounts of planting materials at the onset of rainy seasons[79]. Furthermore, it is reported that insect pests are attracted to areas where vine multiplication occurs during the dry period, emphasizing the need for effective pest control methods to ensure the propagation of pest- and virus-free materials[80]. It is suggested that enhanced sweet potato varieties exhibit yield enhancements of approximately 20% when compared to robust local landraces[81]. Sweet potato weevils are described as the most economically significant pests affecting sweet potato crops both in Africa and globally, with production losses often ranging from 60% to 100%[82]. Efficient weevil management extends storage in drier zones, and enhances food security, while adopting good agronomic practices significantly boosts yields by up to 60%[83]. Furthermore, studies conducted in Mozambique and Kenya have shown that farmers are more likely to engage in labor- and input-intensive technologies only when there is a market to absorb excess root production[84]. However, transporting large products such as sweet potato roots is noted to be relatively costly, underscoring the importance of improved post-harvest practices to ensure extended shelf-life[85]. Ethiopia's agricultural development, notably sweet potato cultivation, grapples with challenges such as scarcity of planting materials, climate change, low input use, and weak market systems. Additionally, factors like pests, disease pressures, infrastructure deficits, and institutional shortcomings further impede progress in this sector.

-

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the value-added use of sweet potato is still emerging, necessitating efforts to improve product quality and streamline market efficiency, especially in biofortification. Advocacy is essential to promote understanding and utilization of orange-fleshed sweet potato as a sustainable and low-cost biofortification tool to combat vitamin A deficiency, particularly in Ethiopia. Furthermore, there is a lack of research on potential negative effects of sweet potato and limited attention to societal perspectives and variety improvements in Ethiopia. Investigating the potential impacts of climate change on sweet potato cultivation and production, along with developing integrated management approaches and postharvest technologies are critical areas that require further exploration.

-

The review result reveals that sweet potato holds significant importance as a vegetable crop globally, prized for its economic, nutritional, and health advantages. Although the global yield stands at approximately 14 tons per hectare, in Ethiopia, it averages 8.1 tons per hectare. Sweet potato is rich in essential nutrients including vitamins C and E, B vitamins, iron, zinc, potassium, and fiber. It is also valued for its versatile use of leaves in Ethiopia, serving as food, animal feed, and traditional medicine. Notably, sweet potato leaves boast high levels of lutein, surpassing those found in kale and spinach. Additionally, the leaves contain substantial protein, carbohydrates, fats, fiber, ascorbic acid, and carotene. Despite Ethiopia's abundant potential for sweet potato production and utilization, challenges such as lack of clean planting materials, pest and disease pressures, knowledge gaps, and deficient market systems persist. Thus, to address malnutrition effectively, concerted efforts are needed, including regular training and robust market linkages across all relevant sectors.

-

Yohannes Gelaye conducted all aspects of the review study, encompassing conception, design, data analysis and synthesis, interpretation, drafting, and final write-up of the paper.

-

The dataset that supports the findings of this review is included in the article.

-

The author acknowledges the anonymous editors and potential reviewers for their valuable input on the script.

-

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Gelaye Y. 2024. Sweet potato: a versatile solution for nutritional challenges in Ethiopia. Technology in Agronomy 4: e014 doi: 10.48130/tia-0024-0011

Sweet potato: a versatile solution for nutritional challenges in Ethiopia

- Received: 26 February 2024

- Revised: 10 April 2024

- Accepted: 26 April 2024

- Published online: 12 June 2024

Abstract: Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) holds significant promise in addressing economic challenges and malnutrition issues. However, various factors in Ethiopia impede its production and consumption. This review investigates sweet potato potential as a versatile solution for nutritional challenges in Ethiopia. Although the global yield of sweet potato reaches 14 tons/ha, in Ethiopia, it stands at approximately 8.1 tons/ha. In Africa, sweet potato is known as the 'poor person’s crop' and is primarily grown on a small scale by women for subsistence. Sweet potatoes are rich in essential nutrients such as vitamins C and E, B vitamins, iron, zinc, potassium, and fiber. Additionally, in Ethiopia, sweet potato leaves are utilized as food, animal feed, and traditional medicine. Notably, they contain high levels of lutein (ranging from 38-51 mg/100 g), surpassing those found in kale (38 mg/100 g) and spinach (12 mg/100 g). Leaves encompass protein (25%−37%), carbohydrate (42%−61%), crude fat (2%−5%), fiber (23%−38%), ascorbic acid (60−200 mg/100 g), and carotene (60−120 mg/100g). Malnutrition is continued as a major hurdle for millions of Ethiopians. Currently, stunting, wasting, and vitamin A deficiency (VAD) stand as the primary factors contributing to premature mortality in Ethiopia. Despite the country's considerable potential for sweet potato cultivation and utilization, both yields and consumption remain remarkably low. Lack of clean planting materials, pests and diseases, knowledge gap, and poor market system are the key challenges of sweet potato production in Ethiopia. Hence, to ease the malnutrition problems in Ethiopia, sweet potato production and utilization should be adept in a broader range.

-

Key words:

- Challenges /

- Consumption /

- Dietary /

- Production /

- Storage roots /

- Vitamins.