-

Coffee stands as one of the globe's most beloved beverages, with its consumption constantly on the rise. The development of coffee-based products can be attributed to its delightful taste, invigorating effects, and the numerous health advantages it offers individuals[1]. Polyphenols, especially chlorogenic acids in coffee, show properties such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and anti-atherosclerotic effects[2,3]. Coffee beverages are made from roasted coffee beans[4]. Roasting plays a crucial role in coffee production as it fosters the enhancement of flavor, aroma, and color. The time and temperature of roasting significantly impacts the formation of flavor elements[5].

Coffee beans come from the coffee plant. Two types of Coffea arabica, commonly known as Arabica, and C. canephora, commonly known as Robusca, are cultivated for this purpose[4].

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are produced by the incomplete combustion or decomposition of organic matter[4]. PAHs are a collection of over 200 hydrophobic compounds composed of two or more fused aromatic rings[4]. Based on the number of aromatic rings, PAHs can be categorized as either light compounds (2–3 rings) or heavy compounds (4–6 rings)[6]. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has categorized 16 PAHs based on their prevalence and toxicity. These include benzo[a]anthracene (BaA), benzo[b]fluoranthene (BbF), indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene (IND), benzo[k]fluoranthene (BkF), dibenzo[a,h]anthracene (DBA), acenaphthene (Acp), acenaphthylene (AcPy), fluorene (Flu), phenanthrene (PA), anthracene (Ant), fluoranthene (FL), pyrene (Pyr), naphthalene (Nap), chrysene (CHR), benzo[a]pyrene (BaP), and benzo[g,h,i]perylene (BghiP)[7].

Many PAHs are recognized as carcinogens, mutagens, and teratogens, presenting significant risks to human health and well-being[8,9]. These compounds lead to colon, breast, and lung cancers[4]. These compounds are also endocrine disruptors and increase the risk of cardiovascular disease[8,10].

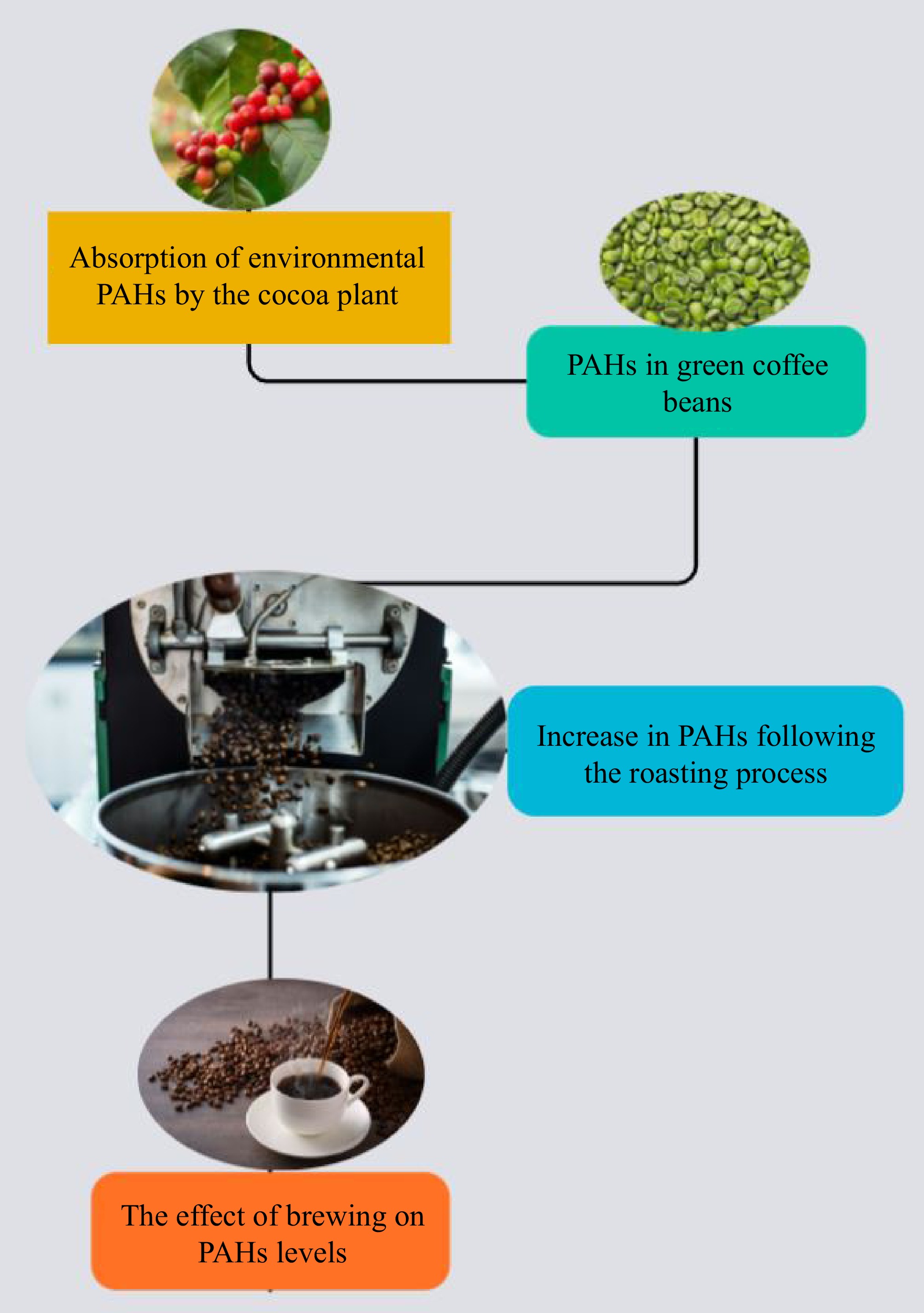

The most important human exposure to PAHs is through food[11]. They are formed in foods during several processes such as roasting, frying, and grilling. The coffee roasting process can lead to the formation of PAHs[12]. The procedure commonly occurs within the temperature range of 120 to 230 °C[3]. Roasting time is usually 15 to 18 min[13]. During coffee roasting, various processes occur including Maillard reactions, sugar decompositions, lipid oxidations, and pyrolysis. These reactions are responsible for the creation of the aroma, flavor, and color of coffee[14]. During the roasting process of coffee beans, existing compounds such as fat, carbohydrates and amino acids are pyrolyzed and PAHs are formed[4]. In addition, the coffee plant also receives PAH compounds through air, water, and soil[15] (Fig. 1).

Various coffee sample preparation and analytical methods have been studied for PAH determination. These methods should demonstrate high specificity, repeatability, and reproducibility[16]. Typically, traditional sample preparation methods involve extracting different solvents and then performing a suitable cleanup process[3]. Some extraction methods are QuEChERS (quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe), sonication, alkaline hydrolysis, supramolecular solvent microextraction (SUPRAS), Soxhlet extraction together with saponification, liquid–liquid extraction, accelerated solvent extraction, and ultrasound-assisted extraction. For the detection and quantification of PAH in coffee, commonly used methods include gas chromatography (GC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)[3,17−20].

This systematic review aims to comprehensively examine the presence and levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in coffee, factors affecting PAH levels, review analytical methods, sample preparation, compare PAH levels in coffee with other similar products, and summarize the risk assessments conducted.

-

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, two authors performed all the steps based on the PRISMA checklist to prevent bias.

Search strategy

-

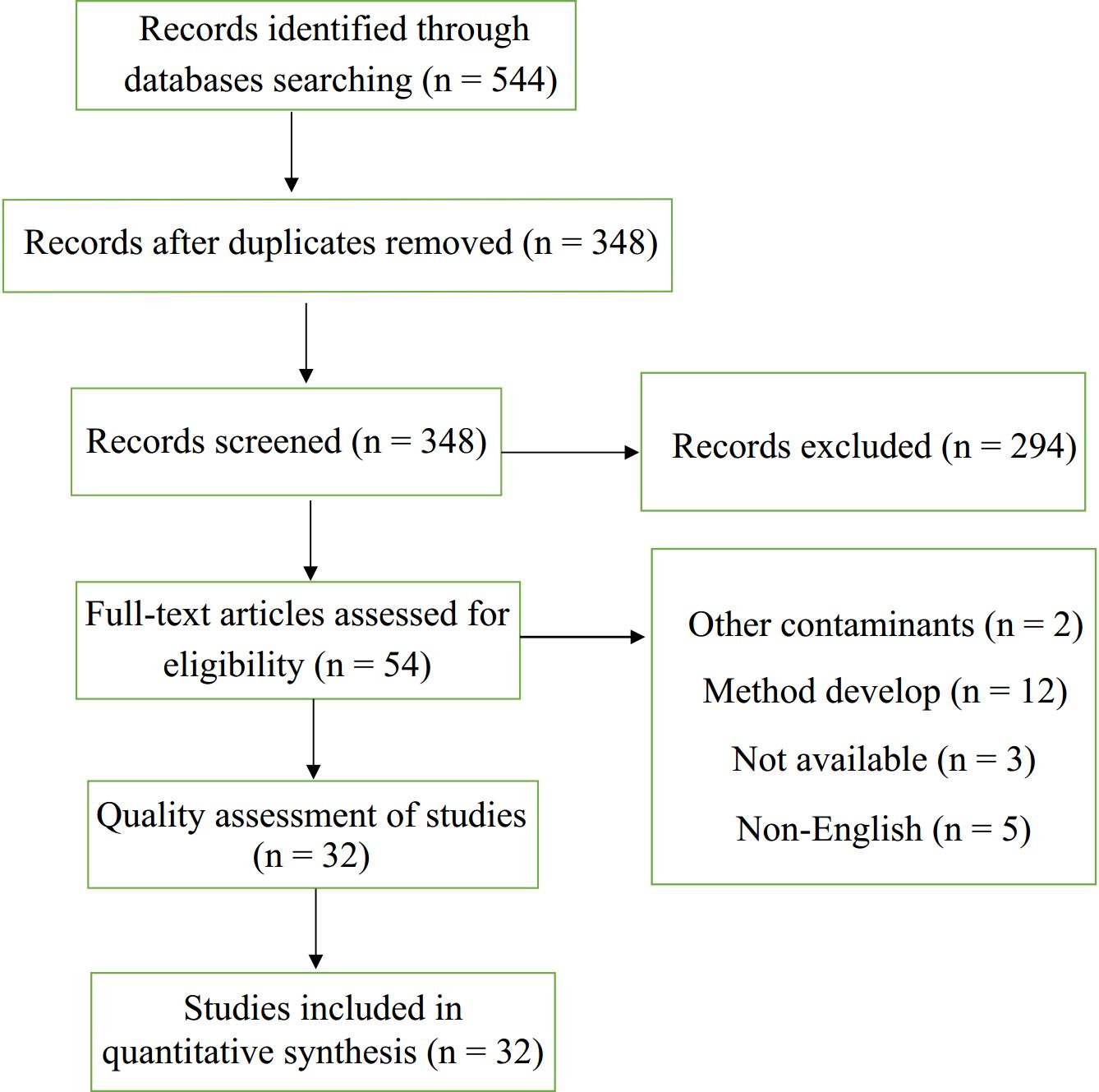

On July 22, 2024, English articles from PubMed databases, Science Direct, Web of Science, and Scopus were received. This study was performed without a time limit. Five hundred and fourty four articles were received based on the search keywords including (PAHs or 'polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon') and (coffee). The title and abstract were checked in the first stage, and according to the criteria, articles unrelated to the main topic were removed. Three authors, including AA, BM, and PS reviewed the studies to extract valuable information.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

-

During the manuscript screening stage, the title and abstract were carefully read, and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded from this study. Exclusion criteria included review articles, book chapters, non-English articles, clinical studies, animal studies, and reviews of other contaminants. Inclusion criteria include all original articles that investigated the amount of PAHs in coffee. Furthermore, special attention was also paid to analytical methods and sample preparation to determine the PAH levels in different coffee samples. This information was extracted from the manuscripts and entered into this systematic study and discussed.

-

Figure 2 shows a diagram of the study. Five hundred and fourty four articles were obtained from the review of four databases. After removing the similar ones, 348 articles remained for title and abstract review. Two hundred and ninety four articles were excluded due to the use of animal studies, clinical studies, book chapters, review articles, and other contaminants. The full text of 54 articles was received, and in the final stage, 32 studies were selected for data extraction and inclusion in the systematic article.

Descriptive results of screened manuscripts

-

Authors Amirhossein Abedini and Bahare Mohamadi extracted important data shown in Table 1, and if a conflict arose, it was corrected by the third author (PS). Country, type of PAHs, PAH measurement method and main findings in Table 1 were extracted from 32 articles. The analytical method for determining the PAH levels in coffees was based on both liquid chromatography and gas chromatography.

Table 1. Total PAHs in coffee products according to the extracted data.

Country Coffee/types Analytical method Main finding Ref. Italy Ground coffee; Espresso coffee GC-MS Benzo[a]pyrene was identified as a harmful compound in two samples (9.0 ng/g in coffee grounds). [15] Brazil Coffee brew GC-MS The identified PAHs included benzo(k)fluoranthene, benzo(b)fluoranthene, pyrene, acenaphthylene and acenaphthene. The most abundant amount was reported in oxy-PAH and nitro-PAH, 5,12-naphthacenequinone and 1-nitropyrene, respectively. [17] China Coffee GC-MS NiFe2O4@Ti3C2TX improved the detection efficiency. [21] Taiwan, China Coffee beans;

Coffee brewsHPLC and GC-MS With increasing degree of roasting, the content of PAHs increased significantly. [18] Thailand Coffee drink GC-FID Poly(o-phenylenediamine)-Zn composite improved PAHs extraction. PAHs values for Benzo(a)anthracene, chrysene, benzo(b)fluoranthene, and benzo(a)pyrene were 1.4 ± 0.4 to 16.5 ± 0.8 μg/L, 0.5 ± 0.2 to 2.1 ± 0.5 μg/L, 2.2 ± 0.6 μg/L, and 6.2 ± 1.0 μg/L, respectively. [22] Chile Coffee HPLC 6–31 μg/L range of PAHs in all samples was reported. [23] Vietnam Roasted coffee beans GC-MS/MS Among 100 samples the amount of PAHs in naphthalene, anthracene, pyrene, fluorene, phenanthrene, and benz[a]anthracene, was 943.7 ± 40.3, 195.1 ± 4.9, 36.1 ± 1.1, 33.3 ± 2.2, 28.2 ± 1.7, and 2.0 ± 0.1 μg/L, respectively. Increasing the coffee roasting time and temperature had the highest effect on increasing the amount of PAHs. There was no risk after assessing the carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks. [24] Iran Coffee GC-MS Among 150 imported coffee maximum and minimum mean levels of PAHs were found in samples from country A (20.78 ± 3.11 μg/kg dry mass (dm)) and F (13.00 ± 2.21 μg/kg dm), respectively. There was no carcinogenic risks. [25] Brazil Brewed coffee GC-MS Fluoranthene was measured only in two samples including 0.1 ± 15 and 22 ± 0.1 μg/L. Benzo[α]pyrene was measured in eight samples with a range of 0.0 ± 12 to 46 ± 0.6 μg/L. Other PAHs were not detected. [26] Iran Coffee GC–MS The maximum mean of PAHs in coffee samples was 13.75 ± 2.90 μg/kg, while the minimum mean PAHs in tea samples was 4.77 ± 1.01 μg/kg. 0.64 to 2.07 μg/kg was reported for average benzo[α]pyrene. There was negligible carcinogenicity. [27] Republic of Korea Roasted coffee beans HPLC-FLD The amount of benzopyrene in dark-roasted coffee beans samples was reported to be 1.27 μg/kg. The use of corona discharge plasma jet decreased the level of 53.6% of benzopyrene. [28] Thailand Robusta coffee beans roasted GC-MSD Only acenaphthylene, acenaphthene, fluorene, phenanthrene, and anthracene were found in the samples. This shows that the hot air method did not have a high effect on the production of PAHs. But increasing the temperature of the Superheated steam method could reduce the content of PAHs. [29] India Coffee HPLC- UV The total amount of PAHs was reported as 16.47 to 18.24 μg/L, in different brands. [30] Taiwan, China Coffee HPLC- UV Environmental migration and cooking method have a direct effect on the amount of PAHs. In unroasted coffee bean brewing solution, benzo[c]fluorene, dibenzo[a,i]pyrene, and dibenzo[a,h]pyrene values were reported as 0.02 ± 0.28, 0.02 ± 0.45, and 0.05 ± 0.05 μg/kg, respectively. Other PAHs were not measured. [31] Poland Arabica and Robusta coffee beans HPLC-FLD/DAD The level of 4.29 to 16.17 μg/kg was observed in roasted coffee beans. [32] Romania Roasted coffee beans HPLC-FLD Benzo[a]anthracene was not measured in Robusta coffee and Arabica coffee samples. Naphthalene had the highest amount of PAHs in all samples. [33] Denmark Coffee GC-MS The total sum of 25 PAHs in coffee samples was reported to be 5.1 μg/kg. PAH4 were not detected in instant coffee. [34] Spain Instant coffee HPLC The results of the analysis showed that benzo-[a]pyrene value was acceptable for EU Directives and was reported below 1 μg/kg. [35] India Grounded coffee brands GC-MS Range of PAHs was 831.7–1,589.7 μg/kg and benzo[a]pyrene was detected in all samples. [7] Mexico Roasted coffee GC-MS The summation of PAHs in coffee samples was from 3.5 to 16.4 mg/kg. [36] France Ground coffee GC-MS The amount of benzo[a]pyrene was low and was not in the range of carcinogenicity. [37] France Ground Arabica coffee brew HPLC Phenanthrene, anthracene, and benzo[a]anthracene was formed at a temperature higher than 220 °C, but the formation of pyrene and chrysene was reported at a temperature of 260 °C. They reported that increasing temperature resulted in the production of high molecular weight PAHs. [38] Nigeria Coffee based drinks GC-FID The amount of three- and four-ring PAHs was higher in the samples. [39] Taiwan, China Coffee HPLC The formation of PAHs increased with increasing roasting of coffee beans. The high pressure of the coffee machine significantly increased the production of PAHs. By calculating the risk assessment, a low level of concern was observed. [20] USA Roasted coffee HPLC Naphthalene, acenaphthylene, pyrene and chrysene were the most abundant in samples. The highest amount of PAHs was reported in dark roasted coffee samples and the lowest in light roasted coffee. [40] Spain Coffee brew HPLC The level of *8PAH was detected in 2.1 ng/L roasted coffees. * Fluoranthene, pyrene, benzo[a]anthracene, chrysene, benzo[e]pyrene,benzo[a]pyrene, benzo[g,h,i]perylene, and, dibenzo[a,h]anthracene. [41] Korea Roasted coffee Beans HPLC The 10 investigated coffee samples showed that concentrations of PAHs were reported between 0.08 ± 0.62 to 9.38 ± 53.25 μg/kg. BaP was reported as harmful PAHs at harmless levels for humans. [42] China Coffee HPLC-UV The range of PAHs in the samples was reported from 2.54 to 50.68 mg/L. The highest was related to benzo(b)fluoranthene and the lowest was related to benzo(k)fluoranthene. [43] Brazil Coffee brew samples HPLC-FLD The type of coffee, the degree of roasting and the brewing process are factors affecting the amount of PAHs. In C. arabica brews, the amount of total PAHs was in the range of 0.015 to 0.105 mg/L, and in C. canephora brews, the amount of 0.011 to 0.111 mg/L was reported. [9] Brazil C. arabica cv. Catuaí Amarelo

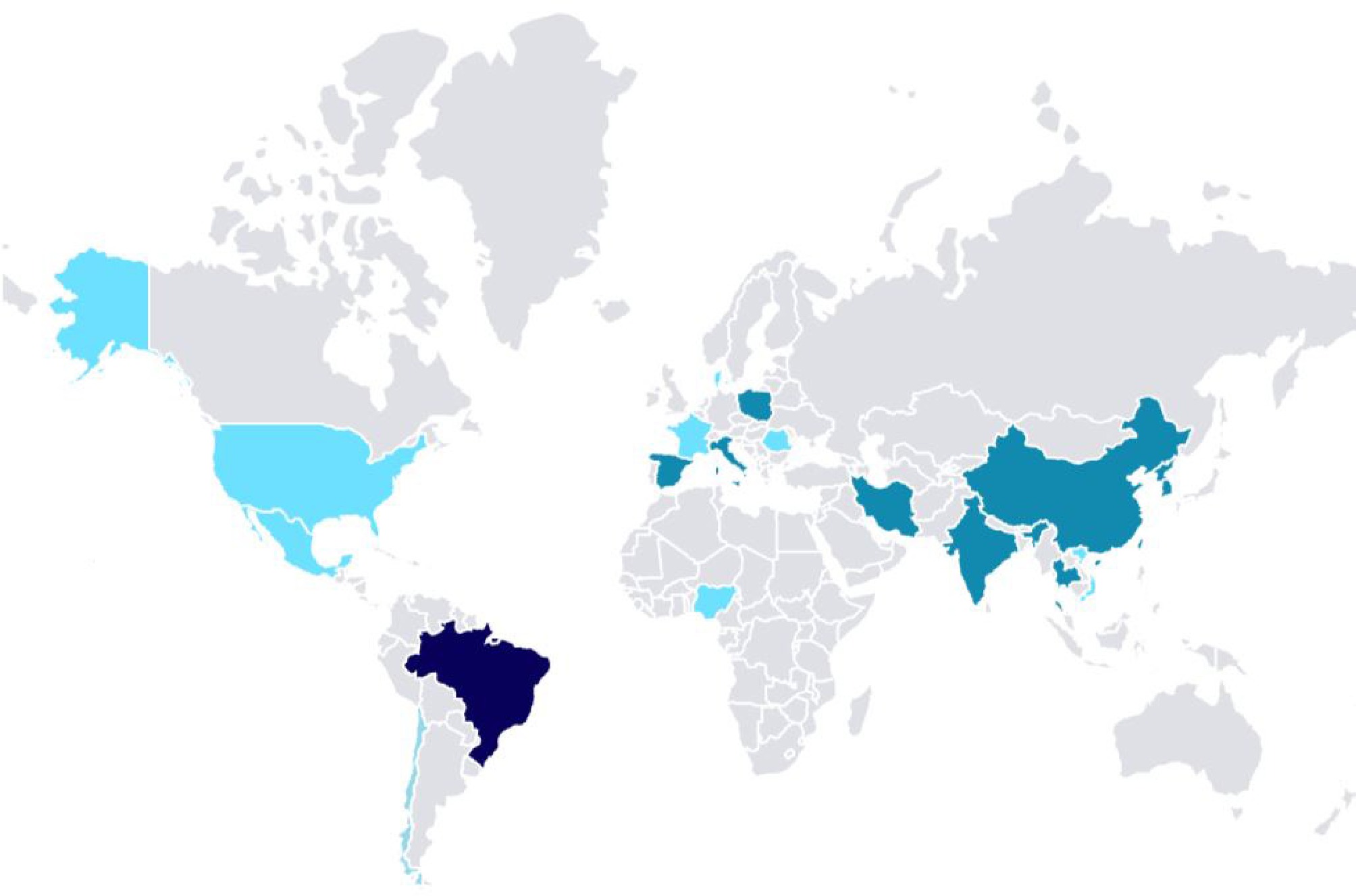

IAC-62 and C. canephora cv. Apoatã IAC-2258HPLC-FLD Medium roasting showed the highest amount of Benz(a)anthracene and total PAHs, but dark roasting showed the highest amount of benzo(b)fluoranthene and benzo(k)fluoranthene. [44] Poland Natural roasted coffee, instant coffee, cereal coffee GC-MS 7.20–68.15 μg/kg for natural roasted coffee and 2.97–19.55 μg/kg for instant coffee and 8.15–15.35 μg/kg for cereal coffee was reported. [3] Italy Coffee brew samples GC-MS Range of sum of PAHs was 0.52 to 1.8 μg/L. [45] GC-MS: Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, HPLC: High-performance liquid chromatography. Figure 3 shows the geographical distribution of studies. The most studies were conducted in Asia Pacific, followed by Europe and South America. Among countries, the most studies were conducted in Brazil. Brazil is one of the exporting countries and one of the largest consumers of coffee[46,47].

-

This systematic review provides a comprehensive overview of current research on the prevalence and levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in coffee. The analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in coffee from various countries shows significant variation in the types and concentrations of these compounds. These differences are due to several factors, especially the roasting conditions of the coffee beans. Roasting is done at different temperatures and for different lengths of time. As a rule, the higher the temperature and length of roasting, the greater the amount of PAHs produced[36]. The health implications of these findings are substantial, especially considering the universal popularity of coffee. The detection of carcinogenic PAHs raises serious concerns regarding potential health risks, highlighting the need for careful monitoring and regulatory interventions to safeguard consumers.

Factors affecting the concentration of PAHs in coffee

-

Some studies have tracked the levels of benzo[a]pyrene in coffee. A notable finding is that benzo[a]pyrene, a carcinogenic PAH, was detected in varying amounts in the samples. For instance, its concentration in coffee grounds from Italy was measured at 9.0 ng/g[15]. While brewed coffee from Brazil showed levels ranging from 0.0 to 46 ± 0.6 μg/L[26]. In another study, the level of benzo[a]pyrene in instant coffee samples was reported to be around 0.1–0.4 μg/kg[35].

Most studies considered total PAHs. In a study, the total PAH levels in roasted coffees was detected in the range of 13.75 ± 2.90 μg/kg[27]. In another study, total PAH levels ranging from 3.5 to 16.4 μg/kg were detected in roasted coffee[36]. The PAH levels in foods depend greatly on cooking conditions and temperature[31]. A study revealed that higher roasting temperatures were correlated with increased PAH concentrations[18]. Similarly, research conducted by Nguyen et al., from Vietnam indicated that longer roasting times and higher temperatures resulted in elevated levels of various PAHs[24]. The authors of this study considered a temperature of 200 °C for 50 min to be appropriate[24]. In a previous study, increasing the roasting temperature of coffee to 260 °C resulted in the formation of two PAHs, pyrene and chrysene[38].

These findings highlight the importance of carefully controlling the roasting processes to reduce PAH formation. Therefore, manufacturers should adopt standardized roasting protocols to alleviate health risks. It has been observed that coffee beans roasted at lower temperatures and lighter colors have lower PAHs than darker coffee beans roasted at higher temperatures[38]. Similar to the results of this study, research conducted in the United States found that darker roasted coffees had higher levels of PAHs than their lighter counterparts[40]. Another study also observed that as the roasting temperature increased, heavier molecular-weight PAHs were formed[39]. Research undertaken in Brazil has shown that PAH profiles can differ significantly depending on the degree of roasting[44]. The authors of a study stated that if mild roasting is done, the PAH levels will not increase. They also emphasize the use of electric heating systems[32]. Also, to reduce the amount of PAHs during roasting, some researchers have suggested roasting in hot steam. Under these conditions, only five PAHs were detected, including acenaphthene, fluorene, phenanthrene, and anthracene acenaphthylene[29].

The region where the coffee is produced also affects the PAH levels. Plants obtain PAHs from their environment, which includes water, soil, and air, so environmental conditions also affect the PAH levels of the environment[18]. Research conducted in Iran showed that PAH levels differ depending on the coffee's country of origin, indicating that geographical sourcing plays a significant role in PAH contamination[25,27]. It was also observed that the PAH levels of green Arabica coffee samples from different countries were different[32].

Regarding the effect of species on PAHs, a study measured both roasted coffee species, Arabica and Robusta. B[a]P levels were reported in both ND[33]. However, this topic is suggested for future research. In particular, one research study found that the Robusca species had higher levels of caffeine, suggesting the formation of a caffeine-PAH complex that may facilitate the transfer of these compounds to the brew[44]. Therefore, there are some ambiguities in this regard.

The brewing conditions also affect the PAH levels. In the study, the total PAH levels in brewed coffee samples was detected in the range of 0.52 to 1.8 μg/L[45]. Analyses of the extracted data show that different brewing methods affect PAH levels[3,4,9,37,38,42,43]. It has been observed that if a coffee maker is used to brew coffee, greater amounts of PAHs are released from the coffee than when the coffee beans are immersed in boiling water[18,20].

Some studies have been conducted on instant coffee. In a study by Grover et al., the PAH levels of four popular brands of instant coffee were measured. Significant differences were observed between the PAHs levels of different brands. The values ranged from 831.7–1,589.7 μg/kg. The authors attribute the observed difference to the manufacturing process[7]. In a study, roasted coffee and instant coffee were compared. The sum of 25 PAHs was higher in instant coffee[34]. This difference is due to the instant coffee production process, which increases the concentration of PAHs. However, PAHs increase with lower molecular weight, which are less dangerous[34].

Health risk assessment

-

A few studies have conducted a risk assessment. Most studies did not identify any risk to the consumer by calculating carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks[24]. In another similar study, the carcinogenic risk was calculated after measuring the PAHs of coffees and no risk was observed for coffee consumers[25]. In a study by Roudbari et al., after determining the amount of PAHs in roasted coffee samples, the carcinogenic risk was calculated, and the values were negligible[27]. In one study, the carcinogenic risk for four carcinogenic PAHs was calculated for roasted coffee and no results of concern were found[34]. In addition, in the study by Wan et al., a risk assessment was also conducted for brewed coffee samples, which found a low level of concern[20].

The PAH levels in roasted coffee is lower than in some grilled and smoked foods. In a study that looked at the PAH levels in a variety of foods, the total PAHs in roasted coffee was lower than in charcoal-grilled sausages and smoked fish[31]. In a previous study, the PAH levels of three beverages based on coffee, tea, and cocoa were measured. Coffee had lower PAH levels than tea and cocoa[39].

Analytical method and sample preparation for determining PAHs

-

Given that an acceptable limit for determining the PAH values in coffees has not been established, a valid measurement method must be used to measure these compounds[15]. The choice of analytical method significantly influences the reported concentrations of PAHs and is probably one of the reasons for the heterogeneity between the results of different studies. The analytical method in most studies was either GC-MS or HPLC-based (Table 1). Regarding the analytical method, a relatively high recovery of the present compounds was observed with the gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS) in studies. The recovery percentage in one study using this method was reported to be around 94% to 106%[34]. In two studies, GC with a FID detector was used. The recovery percentages were relatively good but lower than with GC-MS[22,39]. Both UV and FLD detectors have been used in HPLC. However, the use of FLD detectors is more common[28,35]. In two studies, the recovery rate using HPLC was about 87%[33,35]. This method has been shown to have good sensitivity in measuring PAHs in coffee beans and brewed coffee[18]. A study has shown that HPLC with an FLD detector performs analysis quicker and with greater sensitivity than GC-MS[31].

Coffee has a complex matrix, so the sample preparation for the analytical method plays an important role in determining the PAH values[4]. Regarding sample preparation, SPE cartridges were used in some studies[35,45]. In some studies, the liquid–liquid extraction method was used and C-18 columns were used for the clean-up step[30,32]. Some studies also used the QuEChERS method[20,31]. This method is both accurate and reproducible[31]. In some cases, the saponification process with alkalis was carried out to remove fatty acids[36,37]. Coffee contains 15% fat. Therefore, saponification is an effective method for removing fat[42]. In a study by Guatemala-Morales et al., it was observed that the percentage recovery increased after saponification[36].

In more recent studies, synthetic adsorbents were used in the extraction step. In one study, Poly(o-phenylenediamine)-Zn composite was used for this purpose[22]. Furthermore, the magnetic composite NiFe2O4@Ti3C2TX was used to prepare the samples. Under these conditions, the recovery percentage was about 84.5% to 112.6%[21]. Also, in another study, a (Fe3O4@COF (Tp-NDA), which is a magnetic covalent organic framework nanocomposite was used for the preparation. The percentage recovery range was recorded as 74.6%–101.8%[43].

-

In this systematic review, the detected levels of PAHs in coffee varieties were investigated. In almost all studies, it was concluded that, with increasing roasting temperature and duration, the amount of PAHs with higher molecular weight was higher. Information and education on the need for gentle roasting are essential. Continuous monitoring and improvements in brewing techniques may also help reduce the potential health risks associated with PAHs in coffee. The method of brewing coffee will also affect the amount of PAHs in the cup. Brewing with a coffee machine is usually higher. The location of the coffee is also an influence. This is due to environmental contamination of unprocessed green coffee. The measurement method was mostly based on GC-MS, but HPLC with a fluorescence detector is also sensitive. Risk assessments conducted in some studies indicated that the risk was negligible. For future studies, the difference between the PAH levels in the two types of coffee, Arabica, and Robusta, under the same roasting conditions is recommended.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: performing database search and and initial screen of articles: Abedini A, Mohamadi B; extracting data from the articles: Abedini A, Irshad N; writing manuscript: Sadighara P, Ghanati K; manuscript revision: Sadighara P, Shavali-gilani P, Akbari-Adergani B. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors would like to thank Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ghanati K, Akbari-Adergani B, Irshad N, Mohamadi B, Abedini A, et al. 2025. Concentration of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in roasted coffee beans: a systematic review. Beverage Plant Research 5: e018 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0006

Concentration of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in roasted coffee beans: a systematic review

- Received: 31 October 2024

- Revised: 24 January 2025

- Accepted: 21 February 2025

- Published online: 07 July 2025

Abstract: Coffee is one of the most popular beverages worldwide, and its consumption continues to rise. Coffee beans can be sold as roasted coffee or as green beans. The high temperatures used during roasting can produce various toxic compounds, particularly polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). The aim of this systematic review was to examine the presence and concentration of PAHs in coffee as well as the methods used for sample preparation and analysis. Relevant research literature was searched from databases such as PubMed, Science Direct, Web of Science, and Scopus. The analysis of the extracted data covered PAH types, risk assessment, sample preparation, and analytical methods. The study found significant variability in PAH levels in coffee, influenced by factors such as roasting techniques, origin of coffee, and analytical methods. This underscores the urgent need for standardized analytical protocols to assess PAH in roasted coffee. Furthermore, minimizing the temperature during roasting is a prominent strategy for reducing PAH in coffee.

-

Key words:

- Roasted coffee /

- PAHs /

- Analytical techniques