-

Galloylated flavan-3-ols (galloylated catechins) are characteristic flavor components in tea. Tea is an important source of dietary intake of galloylated catechins. Because of the health benefits of galloylated catechins, tea-containing beverages are popular worldwide. At present, the bioefficacy of galloylated catechins is mainly focused on anti-cancer, anti-cardiovascular disease, anti-diabetes, neuroprotection, skin health, and so on. A large number of in vitro and animal experiments have shown that epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) or green tea catechins with EGCG as its main component can prevent a variety of cancers[1−3]. The anticancer mechanism of EGCG involves many pathways, including its antioxidant and pro-oxidative effects, high affinity with a variety of biological target molecules, deactivation of important cellular enzymes, and inhibition of receptor-dependent signaling pathways, and angiogenesis. A large number of epidemiological studies have shown that the intake of green tea and oolong tea rich in polyphenols contributes to the body's resistance to cardiovascular disease[4−6]. Due to antioxidant effects, polyphenols can reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol oxidation and lipid peroxidation, and inhibit the formation of atherosclerotic plaque[7,8]. The mechanism of tea to prevent and alleviate diabetes involves many pathways, including adiponectin regulating fat and carbohydrate metabolism[9,10]. EGCG and green tea extract have also been reported to prevent Alzheimer's disease by inhibiting the formation of β amyloid, alleviating synaptic damage, and improving learning and memory ability[11].

In addition to health effects, phenolic compounds such as EGCG are closely related to the astringent quality of tea beverages[12,13]. Phenolic compounds are considered to be the main compounds that make up the astringent taste of fruits, vegetables, tea, wine, and other foods. Many researchers have reported the mechanism of phenolic compounds and astringent sensation formation in fruits, vegetables, tea, and wine[12,14,15]. The galloyl group of phenolic compounds contributes more to the astringency. The binding experiments of salivary proteins to phenolic compounds showed that the protein binding ability of flavan-3-ols (EGCG, GCG, CG) containing galloyl groups was significantly higher than that of catechin and proanthocyanidin B2 without galloyl groups, while phenolic acids and flavonol glycosides even had no protein binding ability[16,17]. With the increase in the proportion of galloyl groups in PAs, the bitter and astringent taste of wine increased[14]. In addition, the researchers also found that the astringency characteristics and intensity of grapes were affected by the type, content, mean degree of polymerization, and the ratio of galloyl- and trihydroxyl- flavan-3-ols. The taste of tea made in different seasons will also be different due to the difference in the content of polymerized catechins, galloyl catechins, and other gallate compounds in leaves harvested in different seasons. For example, tea samples made in autumn with a coarse and astringent taste were most significantly affected by polymerized catechins, and tea samples made in early spring with a heavier grassy and astringent taste had higher hydrolyzable tannin[12].

As galloylated catechins are important health and quality components, the biosynthesis, and regulation of catechins in tea plants is also a hot research topic. For plants with strong astringencies, such as tea plant, grape and persimmon, it is of great application value to de- or reduces the astringent taste of fruits or tea beverages by regulating the content of phenolic compounds. In this paper, the important progress of catechins biosynthesis and regulation in tea plants in the last decade was reviewed.

-

In recent decades, the detection technology of phenolic compounds in tea and other plants has developed rapidly. The commonly used qualitative and quantitative detection techniques include Q-Exactive Focus Orbitrap LC-MS/MS, Q-TOF-LC/MS, and LC-QQQ-MS/MS technology[18,19]. Based on the retention time, maximum absorption wavelength, mass spectrum deionization peak, mass-to-charge ratio, and secondary fragment ion characteristics, standards, and references were used for qualitative and quantitative analysis. A total of 86 polyphenols were identified from 47 green tea samples with varying astringency scores, of which 76 compounds were relatively quantified, including 13 phenolic acids, 24 oligomeric proanthocyanidins, 14 flavanols, and 31 flavonols, and their glycosides[12]. Metabolome detection technology is increasingly applied to detect the secondary metabolism of tea plants, and hundreds of phenolic compounds can be detected. However, absolute qualitation and quantitation of these compounds remains a challenge. In the future, the number of phenolic compounds identified and quantified in tea plants will continue to increase.

The distribution of phenolic compounds in tea plants showed obvious tissue and organ specificity. Although oligomeric catechins (proanthocyanidins) are relatively common in plants, for tea plants, the polymerized catechins are mainly distributed in tea roots (about 85 mg/g), while the monomeric catechins, especially galloylated catechins are mainly accumulated in the young leaves, and decreased with the development of leaves[20]. Zhang et al. analyzed the monomeric catechins in 176 tea accessions, the results showed that several compounds were affected by leaf size or subpopulation, but there was no significant difference between arbor and shrub types[21]. They also reported that EGCG was significantly higher in ancient trees in Tukey’s test but this significance was not detected in mixed linear regression[21].

Even in the leaves, the distribution of tea polyphenols showed significant spatial differences. Recent advances in spatial metabolite detection have provided clear insights into the distribution differences of phenolic compounds within tea plants. For example, research by Liao et al. demonstrated that epicatechin gallate (ECG)/catechin gallate (CG), epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG)/gallocatechin gallate (GCG), and gallic acid (GA) were evenly distributed on both sides of the leaves, while epicatechin (EC)/catechin (C), epigallocatechin (EGC)/gallocatechin (GC), and assamicain A were distributed near the leaf vein[22].

-

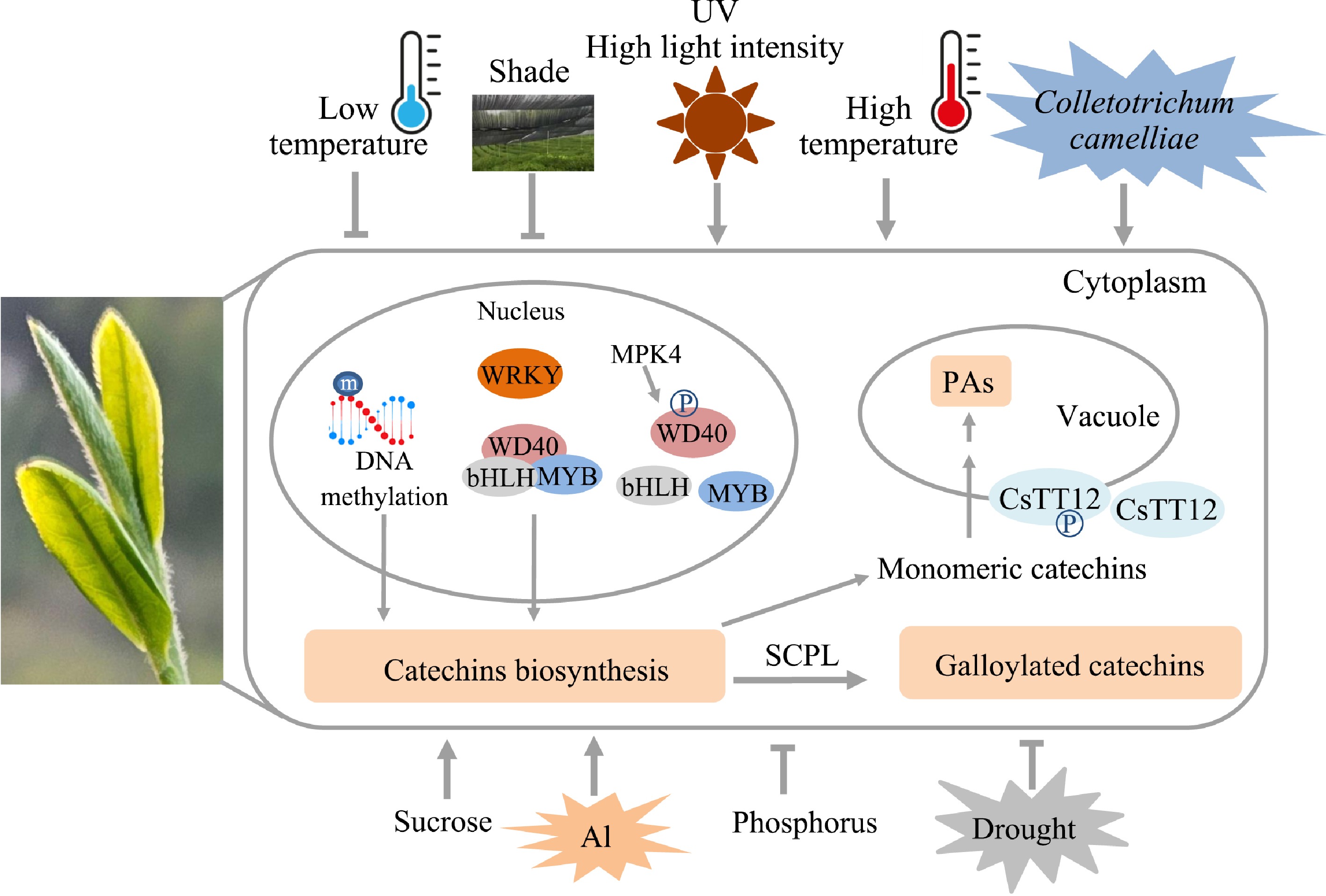

The structure of galloylated catechin contains two parts: flavan-3-ol structure and galloyl group. The biosynthesis of flavan-3-ols and other flavonoid compounds is through the main Shikimic acid-phenylpropanoid-flavonoid pathway and four main derivatization reactions, including hydroxylation, glycosylation, acylation, and condensation reactions of polyphenols[12] (Fig. 1). At least 36 transcripts of 12 structural gene families involved in the biosynthesis of catechins have been identified[23]. In the early steps of the flavonoid pathway, the genes (such as CHS) are generally dispersed across multiple orthogroups, possibly due to their functional specialization toward a wider range of substrates, reflected in a greater amino acid divergence. In the late steps of the pathway, the genes in the tea genomes (F3′5′H, DFR, ANS, and LAR) generally exhibit a higher gene copy number than Arabidopsis[21].

Figure 1.

Profiling of the polyphenol biosynthesis pathway and derivatization reactions in tea plants[12].

Anthocyanidin reductase (ANR) and leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR) are the two terminal enzymes of cis- and trans-flavan-3-ol synthesis, respectively. It is generally believed that ANR is responsible for cis-flavan-3-ol synthesis in plants, while LAR catalyse leucoanthocyanidin to trans-flavan-3-ols[24,25]. However, the reality is more complicated. Our group's preliminary research suggested that there are differences in the function of ANR in vitro and in vivo. Recombinant ANR overexpressed in E. coli catalyzed the production of cis-flavan-3-ol (EC), while this product was not detectable in ANR overexpressed tobacco[26]. Further studies have shown that ANR enzymes directly produce a class of unstable catechin intermediates in plants, serving as carbocations for the synthesis of polymerized catechins (proanthocyanidins). The results of this study reinterpreted the function of the ANR enzyme and further elucidated the biosynthesis mechanism of plant proanthocyanidins[26]. Plant LAR enzymes could be categorized into three types: G, A, and S. Although the product of CsLARs overexpressed in recombinant E. coli was trans-flavan-3-ol (C), overexpression of CsLARs in tobacco results in the production of cis-flavan-3-ol (EC) along with a decrease in the polymerized catechins[27].

Catechins could be accumulated in the root, callus, or mature leaves of tea plants in the form of polymerization[20,28]. The polymerization of monomeric catechins is a condensation reaction, and whether this reaction is enzymatic or non-enzymatic has been controversial. Our results indicate that there are non-enzymatic condensation reactions in plants. The LAR product is the starting unit, and the ANR product carbocation is the extension unit[20,26].

-

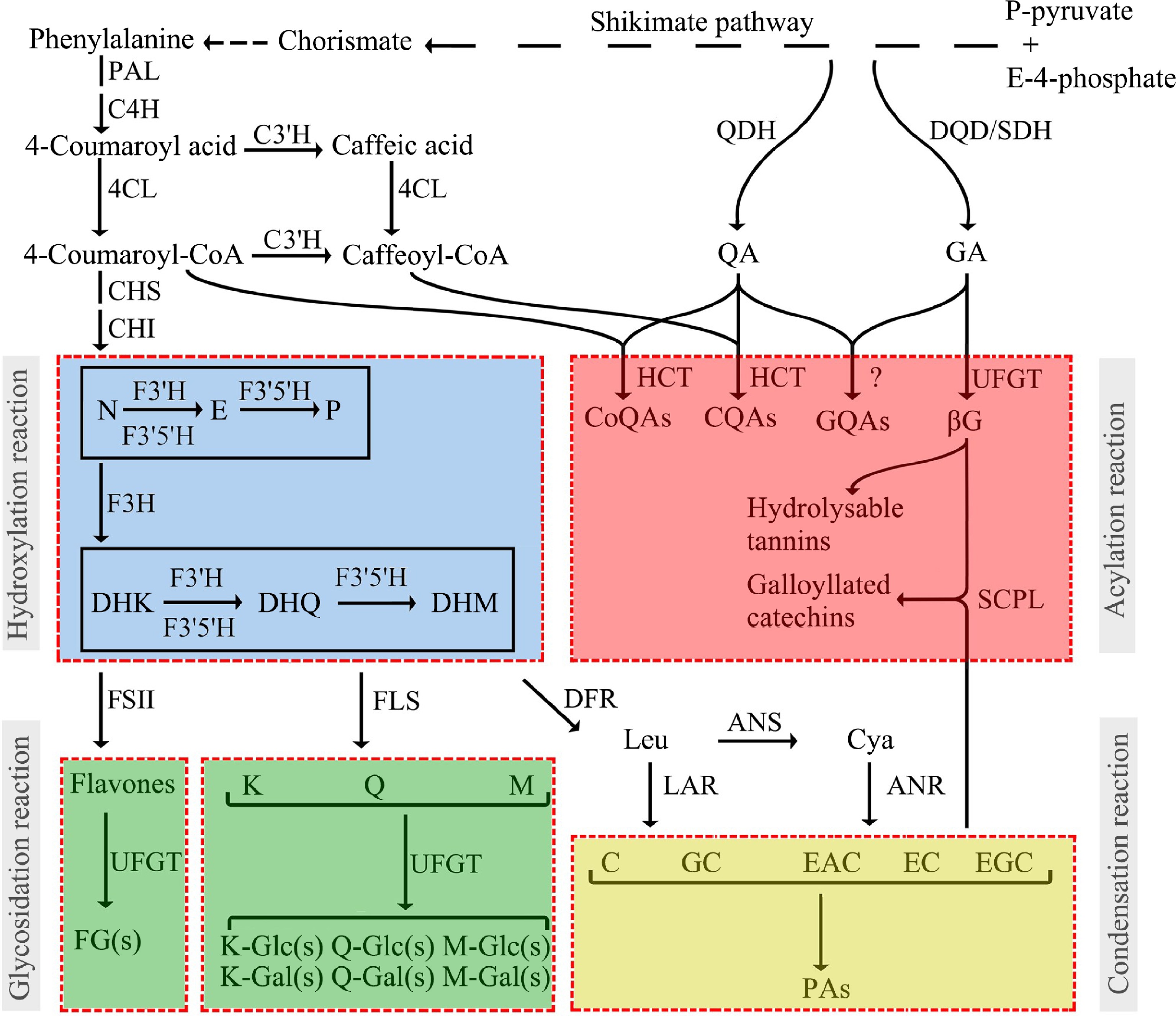

In tea leaves, catechins mainly exist in the galloylated form, which accounts for 70% of the total catechins. Therefore, the galloylation of catechins is the key step to uncover the biosynthesis of catechins. Liu et al. used UDP-glucose (UDPG) as a sugar donor, gallic acid (GA), and non-galloylated catechins epigallocatechin (EGC) or epicatechins (EC) as the receptor substrates for in vitro dual enzyme assays employing crude enzyme extracted from tea plants[29]. Galloylated catechins products EGCG or ECG were detected. Further research indicated that the synthesis of galloylated catechins in tea plants involved two enzymes, UDP-glucose: galloyl-1-O-β-D-glucosyltransferase (UGGT), and epicatechin: 1-O-galloyl-β-D-glucose O-galloyltransferase (ECGT).

To determine the UGGT gene, nine UGTs belonging to the L group in 132 CsUGTs were selected to explore their catalytic function[30]. The results of in vitro enzymatic experiments showed that only CsUGT84A22 recombinant protein had specific activity toward hydroxybenzoic acid and hydroxyphenylpropionic acid. Among these substrates, CsUGT84A22 exhibited the highest activity towards p-coumaric acid and GA. That is to say, CsUGT84A22 is the UGGT gene. In many tannin-rich plants, the enzymes of the CsUGT84A22 homolog have been shown to catalyze GA glycosidylation[30,31].

In the experiment of Liu et al.[29], the ECGT gene has been predicted to be the serine carboxypeptidase-like acyltransferase (SCPL-AT) gene. After ten years of exploration, Yao et al. discovered that only the co-expression of two homologous SCPL-ATs in tobacco could obtain recombinant proteins with catalytic activity. CsSCPL4 had a conserved catalytic tri-residue S-D-H, while its homologous protein CsSCPL5 acted as non-catalytic companion paralogs (NCCP)[32]. Substrate specificity research showed that the recombinant proteins co-expressed by CsSCPL4-1 and CsSCPL5 had specificity for the cis-flavan-3-ols, and could not catalyze the galloylation reaction of trans-flavan-3-ols[32]. In another paper from the same group, the recombinant proteins co-expressed by CsSCPL4-2 (a homolog of CsSCPL4-1) and CsSCPL5 were found to have a weak ability at galloylation of trans-flavan-3-ol[33].

Enzymes involved in degalloylation of catechins were confirmed to be tannases belonging to the carboxylesterases in the hydrolase superfamily[34]. Based on amino acid sequence alignment, the molecular weight and conserved motifs of tea plants were similar to those of microbial feruloyl esterase/tannase with 'non-CS-D-HC' motifs, although sequence identity was low. According to enzyme kinetic parameters Kcat/Km, galloylated catechins, and penta-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranose (PGG) were the optimal substrates for CsTA. Based on homology alignment and enzymatic identification, a plant tannase family was excavated in Theaceae, Vitaceae, Myrtaceae, Punicaceae, Actinidiaceae, Juglandaceae, Fagaceae, Rosaceae, and others. These plant tannases, unlike microbial tannases, have independent phylogenetic origins (from approximately 120 million years ago)[34]. Further analysis by transient overexpression and RNA interference experiments in strawberry showed that the expression of FaTA regulated the balance between hydrolyzable tannin and anthocyanin accumulation in strawberry fruits[34].

Recently, our research showed that CsTA could perform the dual functions of hydrolase and acyltransferase, which are responsible for catalyzing galloylation and degalloylation, respectively[35]. In the first step, CsTA hydrolyzed the galloylated compounds EGCG or PGG into their degalloylated forms, and a long-lived covalently bound Ser159-linked galloyl–enzyme intermediate was formed. Under nucleophilic attack, the galloyl group on the intermediate was cleaved and transferred to the nucleophilic acyl acceptors, including water, methanol, flavan-3-ols, and hydrolyzable tannins. In this study, the promiscuous acyltransferase activity of plant tannase was reported for the first time. TA catalyzed degalloylation and galoylation can indeed occur simultaneously in plants[35].

Based on the collinearity analysis, a TA-UGT-SCPL-AT gene cluster was identified in the Chinese Rubus genome, which is rich in hydrolyzable tannins[36]. The gene cluster contains 11 CXEs (including tannase gene), eight UGTs (including UGT82), and six SCPL-ATs (including SCPL4 and SCPL5 homologous genes). Collinearity analysis indicated that this gene cluster also existed in the genomes of many tannin-rich plants, including Myrtaceae, Pomegranaceae, Kiwiaceae, Juglans, Bucketaceae, and Rosaceae[33,36].

The divergence time and divergence type between SCPL-AT genes could also be estimated by non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site (Ka) and synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) and their ratios (Ka/Ks). The Ka/Ks between genes can be used to explore the evolutionary timing of tea galloylated catechin biosynthesis. For example, the Ka/Ks between SCPL4-1 and SCPL4-2 genes responsible for cis- and trans- catechins galloylation were 5.35 Mya. Based on the comparative transcriptome analysis and metabolic analysis of 113 Camellia plants, it was found that Camellia plants originated from 14.30 mya, the diversification of section thea plants originated from 6.67 mya, and the diversification divergence between the two types of cultivated tea plants occurred from 0.82 to 2.160 mya[38]. The results displayed that the differentiation time of SCPL4-1 and SCPL4-2 was closer to diversification of section thea plants.

Tea plants, persimmons, and bayberry leaves are known to be very high in galloylated catechins. According to the data, EGCG accounts for 70% of the total catechins in tea plants, that is, the galloylation percentage of catechins reaches 70%[18]. The same percentage can be achieved in persimmon fruits, which can also reach 10%−20% in grape seeds[39,40]. Catalytic residue mutations occurred in the SCPL5 homologous genes in tea plants, persimmons, and grapes, indicating that the mutation of CsSCPL5 pseudoenzyme was positively correlated with the accumulation of galloylated catechins. So the occurrence of CsSCPL5 orthologous pseudoenzyme was indeed related to the high accumulation of gallaloyl catechins. The Ka/Ks values of the total catalytic residues of Camellia oleifera SCPL5 and C. sinensis SCPL5 pseudoenzymes were 3.79 Mya. Can we calculate the evolutionary origin of galloylated catechins from this?

In a word, the SCPL neofunctionalization and subfunctionalization mutations in the gene cluster provide genetic and biochemical evidence to explain the differential accumulation of galloylated catechins in different Camellia species and the high accumulation of galloylated catechins in tea plants (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Galloylation-degalloylation cycle involves in galloylated catechin and hydrolyzable tannin synthesis[37].

-

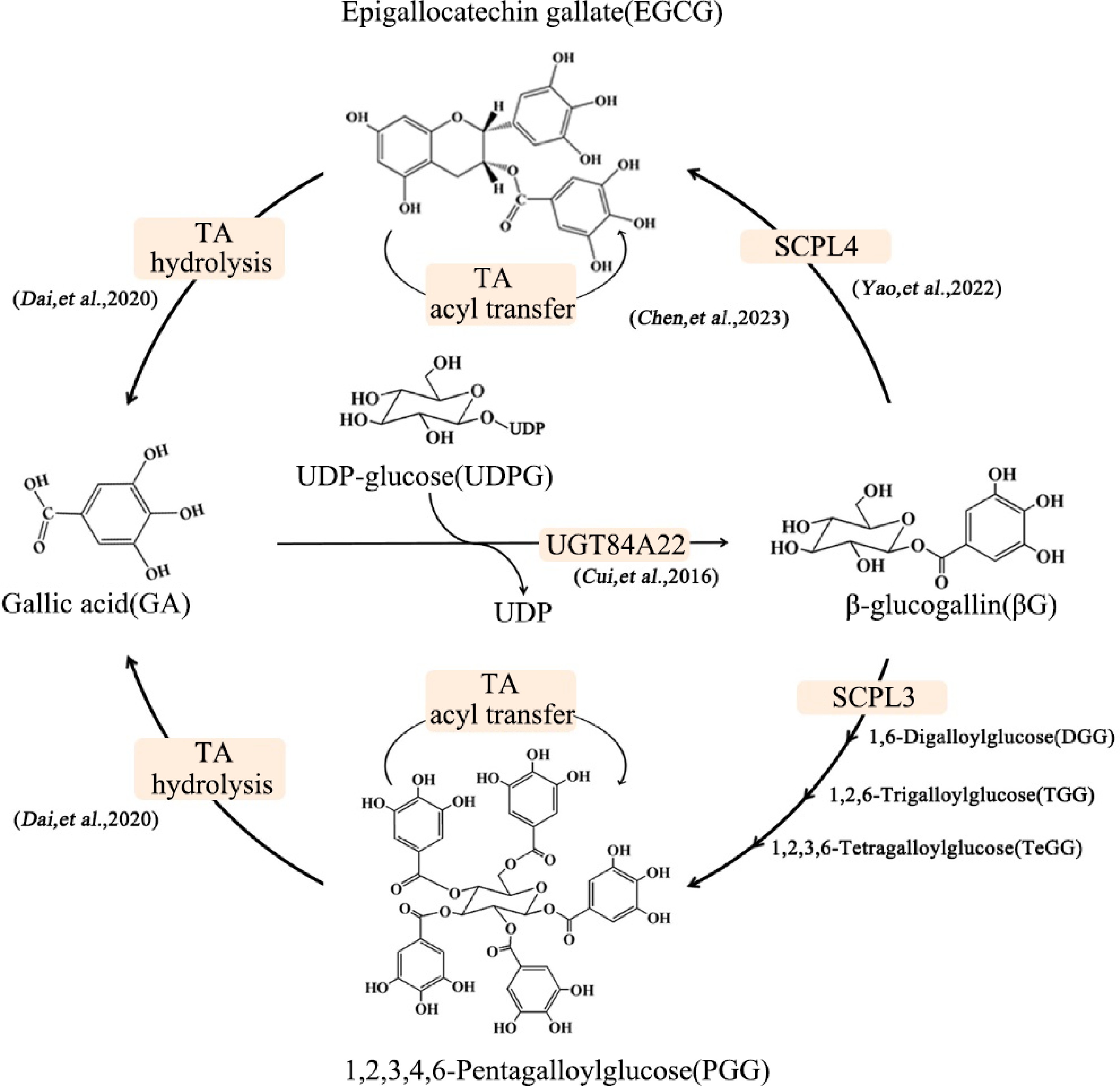

Many studies have shown that biotic and abiotic stresses have impact on the accumulation of catechins by affecting gene transcription expression, epigenetic modifications of genes, protein translation, and post-translational modifications (Fig. 3).

Regulation at the transcription level

-

A series of studies focused on the MBW triple complex, which includes various MYB subgroups, bHLH, and WD40 transcription factors. It has been shown that these proteins play a crucial role in catechin biosynthesis in tea plants[41−45]. Notably, the functions of these transcription factors are largely conserved compared to their counterparts in model plants, although distinct expression differences are evident. For example, among the nine CsMYB5 members regulating the biosynthesis of flavan-3-ols - the precursors of galloylated catechins - CsMYB5a, CsMYB5b, and CsMYB5e are responsive to high-intensity light, high temperatures, methyl jasmonate (MeJA), and mechanical damage. In contrast, CsMYB5f and CsMYB5g specifically respond to damage induction[41]. These findings highlight the significant role of upstream regulators in modulating the MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) triple complex, providing insights into the unique metabolic pathways of tea plants compared to model species.

The accumulation of flavonoids is also regulated by epigenetic regulation, for example, DNA methylation[46]. In different seasons, the epigenetic mark DNA methylation (5mC)-mediated response of gene expression is highly correlated with the accumulation of flavonoids in the new shoots[46].

Regulation at the protein level

-

Recent studies have shown that the proteins that regulate the synthesis and transport of flavonoid compounds are regulated by phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and other protein levels in tea plants[43,47,48].

Monomeric proanthocyanidins are transported to vacuoles and condensed to form polymeric compounds by MATE family transporter CsTT12. Phosphorylation enhanced the localization of CsTT12 in the vacuole membrane, promoted its transport function, and enhanced proanthocyanidin polymer biosynthesis, while dephosphorylation changed its localization and reduced its transport function[47]. Biosynthesis of flavonoids in tea plants is positively regulated by the MYB-bHLH-WD40 complex involving multiple R2R3-MYB members of subgroup 5 and 6. WD40 regulatory protein in the phosphorylated state catalyzed by MPK4a could not participate in the formation of the MYB-BHLH-WD40 complex, thereby negatively regulating the biosynthesis of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins under drought stress in tea plants[43]. The subgroup 4 R2R3-MYBs are negative regulators of lignin and flavonoid biosynthesis pathways. Phosphorylation by MPK3-2 not only weakened the transcriptional inhibitory activity of CsMYB4a on key genes in the lignin and phenylpropanoid pathways but also activated the expression of YABBY5, a transcription factor associated with the adaxial–abaxial polarity of the leaf[49].

CsMYB90 and CsGSTa are related to anthocyanin accumulation. At the post-translational modification level, the RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase CsMIEL1 interact with CsMYB90 and CsGSTa, inhibits the accumulation of anthocyanins under low temperatures in tea plants[48].

Regulation by biological and abiotic stress

-

Many researchers have reported that the accumulation of catechins was regulated by various biological and abiotic stresses. Disease (anthracnose) and pest (Ectropis grisescens) induced gene expression of the flavonoid pathway, thus enhancing the flavonoid accumulation in tea leaves[50,51]. In vitro feeding experiments exhibited that Ectropis grisescens displayed more significant antifeeding against acylated catechins, for example (−)-epicatechin-3-O-caffeoate[51].

Various abiotic stresses affect the yield and quality of tea plants[52]. Low temperatures, salinity, drought, and shading generally suppress the synthesis of flavonoid compounds in tea plants[43,48,53,54], while the presence of metal ions, sucrose, ultraviolet light, and heat appear to stimulate flavonoid accumulation[50,55−62].

Shading can improve the quality of tea by increasing the content of theanine and reducing the accumulation of flavonoids, which have been widely studied. In recent years, many studies have focused on the comprehensive effects of shading with light quality, light intensity, and temperature on tea yield and quality, and the results showed that the influence of shading on tea is a complex process[54]. A low concentration of aluminum promotes the growth of tea plants, and a high concentration of aluminum inhibits the growth of tea plants. Aluminum treatment promotes the accumulation of flavan-3-ols and flavonols, and their complexation with aluminum enhances the aluminum tolerance of tea plants[56−58]. Sucrose acts as both a carbon source and a signaling molecule, regulating plant metabolism. Sucrose treatment can significantly increase the accumulation of flavonoids, especially the anthocyanidins and polymerized proanthocyanidins[55,62].

-

Although research on the regulation of catechins biosynthesis has made great progress, there are still many problems to be solved. Especially for the 'G-DG cycle', there is almost no research on the regulation, and its role in coping with biological and abiotic stresses is almost unknown. In the future, the transcriptional regulation of galloylated catechins needs further research. Although several transcription factors that regulate catechins biosynthesis have been reported, for example, MYB, bHLH, WD40, and WRKY, little is known about the regulation of galloylated catechins. Moreover, whether the biosynthesis of catechins, especially for the 'G-DG cycle', is regulated by epigenetic regulation, for example DNA methylation, or modified at protein levels, such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination, also requires further study. In addition, various environmental factors affect the biosynthesis of galloylated catechins, such as low temperature and drought, high temperature and high light intensity, etc. The impact of single factors in greenhouses is well studied, but the impact of comprehensive factors in field environments needs to be further analyzed.

This work was supported by the Joint Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20232), and the Natural Science Foundation of China (32372758 and 32372756).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: the presented paper was conducted in collaboration by all authors; writing the original draft: Jiang X, Liu N; manuscript review: Xia T, Liu Y, Gao L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang X, Liu N, Liu Y, Gao L, Xia T. 2025. Exploration of the biosynthesis of galloylated catechins in tea plants. Beverage Plant Research 5: e023 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0009

Exploration of the biosynthesis of galloylated catechins in tea plants

- Received: 21 January 2025

- Revised: 27 February 2025

- Accepted: 10 March 2025

- Published online: 04 August 2025

Abstract: Galloylated flavan-3-ols (galloylated catechins) are not only the functional components that are beneficial to human health but also the characteristic components that endow tea flavor. Tea is an important source for people to ingest galloylated catechins. The galloylated catechin contains the basic structure of flavan-3-ol and a galloyl group. Thus, their biosynthetic pathway involves flavan-3-ol biosynthesis and galloylation and degalloylation reactions. The biosynthetic pathway of flavan-3-ol and its regulation have been studied intensively. Regarding the source of galloyl groups, we propose that there exists a 'galloylation-degalloylation cycle (G-DG)' pathway in tannin-rich plants, which consists of three catalytic steps controlled by gallic acid glucosyltransferase (UGT84A22), serine carboxypeptidyase-like acyltransferase (SCPL-AT), and tannase (TA). It is not only the main terminal pathway for galloylated catechin biosynthesis, but also the main initiation pathway for hydrolyzable tannin biosynthesis. In this paper, we review the research progress on the biosynthesis and regulation of the flavan-3-ol, and G-DG pathways.

-

Key words:

- Flavan-3-ols /

- Galloylated catechins /

- Tea plants