-

Fulvic acid (FA), a vital component of humic acids (HA), is primarily derived from the long-term transformation of plant residues and microbial metabolites. It is ubiquitously present in soils, sediments, and surface waters[1]. FA possesses a complex macromolecular structure with significant heterogeneity[2], containing abundant functional groups such as aromatic moieties, carboxyl groups, and phenolic hydroxyl groups[3]. These functional groups enable FA to form stable complexes with metal ions (e.g., heavy metals including Fe, Cu, and Pb), thereby altering the mobility and bioavailability of the metal ions[4,5]. Furthermore, FA can interact with various organic pollutants, including antibiotics, pesticides, and pharmaceutical residues[6,7]. In water treatment systems, FA is often regarded as a key precursor of disinfection by-products (DBPs). Its presence can lead to the formation of harmful by-products, such as trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids, which pose potential risks to drinking water safety[8−10]. Consequently, the effective removal of FA from aqueous systems to mitigate its interference with subsequent treatment processes has become a critical focus in environmental research.

Photocatalytic technology exhibits multi-dimensional core advantages in pollutant degradation: it is driven by clean energy such as solar energy, with reusable catalysts and no secondary pollution; the highly oxidative reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in the reaction can break the stable chemical bonds of complex and refractory pollutants, achieving deep mineralization; meanwhile, it has extremely strong synergistic potential and can be flexibly coupled with other AOPs to significantly enhance efficiency. The fundamental mechanism involves the excitation of semiconductor catalysts under light irradiation to generate electron–hole pairs, which subsequently produce ROS such as •OH and O2•− for pollutant oxidation[11,12]. However, under practical conditions, photocatalytic oxidation faces several challenges, including wide bandgap limitations, low quantum efficiency, and the rapid recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs[13]. Particularly, for the degradation of complex and refractory organic compounds like FA, a single photocatalytic oxidation process often fails to achieve complete mineralization[14]. Therefore, it is necessary to combine photocatalytic oxidation with other AOPs to improve degradation efficiency. Compared with traditional pollutant removal methods, AOPs exhibit stronger treatment capacity for refractory organic pollutants. While traditional biological treatment technologies rely on microbial metabolism, AOPs can avoid 'transfer-type' pollution, achieve pollutant mineralization, and reduce the risk of secondary pollution. In contrast, traditional methods are highly susceptible to factors such as water pH, temperature, and pollutant concentration, whereas some AOPs can operate stably within a wide pH range and temperature interval[15,16], demonstrating higher adaptability for the treatment of high-concentration organic wastewater with complex components. Among these, the integration of photocatalytic oxidation with persulfate (PS)-based activation has gained growing attention, as it can simultaneously utilize photogenerated charge carriers and sulfate radicals (SO4•−) to achieve superior oxidative performance.

Persulfate, including PMS and peroxydisulfate (PDS), is an ideal oxidant precursor with high stability and controllability. Under appropriate conditions, PMS can be activated to generate SO4•−[17]. Typical activation methods include thermal activation[18], carbon-based material activation[19], transition metal activation[20], and photocatalytic activation[21,22]. Compared with single persulfate or photocatalytic systems, photocatalytic PMS activation more effectively promotes S-O bond cleavage via photogenerated electrons, facilitating rapid SO4•− generation and enhanced oxidation capacity[23]. For instance, Liu et al. synthesized a novel S-scheme 2D/3D g-C3N5/BiVO4 heterojunction photocatalyst that activated the Fe2+/PMS system under visible light for the degradation of tetracycline (TC), achieving a removal efficiency of 96.80%[24]. Similarly, Mg-doped ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles coupled with PMS activation exhibited a high degradation efficiency of 89% for 4-nitrophenol (4-NP)[25]. These studies highlight the remarkable potential of PMS activation systems for the degradation of refractory organics. SO4•− is one of the active species with the strongest oxidizing capacity, featuring a standard redox potential as high as 2.6 V. This potential is significantly higher than that of most other ROS, enabling it to efficiently attack electron-rich functional groups of organic pollutants (such as aromatic rings and double bonds) and achieve deep degradation of refractory pollutants. The high redox potential and anti-interference ability of sulfate radicals are its core advantages[26], while PMS has become the preferred oxidant for generating this radical in experiments, due to its high yield of dual active radicals after activation, pH-controllable stability, and efficient synergistic activation with ultrasound (US).

Among various photocatalysts, bismuth-based materials have attracted increasing interest due to their unique electronic structures and superior light response properties. In particular, bismuth-based halides (BiOX, X = Cl, Br, I) have attracted special attention among numerous photocatalysts due to their layered structure and excellent charge separation properties, with BiOCl being the most widely studied representative material[27]. BiOCl consists of alternating [Bi2O2]2+ layers and halogen anions, a structure that facilitates efficient separation of photogenerated charge carriers. Additionally, BiOCl possesses a suitable bandgap, enabling it to respond effectively to both UV and partial visible light ranges, thereby enhancing photocatalytic efficiency[28,29]. Under light irradiation, BiOCl can effectively activate PMS to generate both SO4•− and •OH[30], exhibiting synergistic oxidation effects toward antibiotics, dyes, and organic pollutants[31,32]. For example, Yu et al. prepared an S-scheme Co3O4/BiOCl heterojunction with enriched oxygen vacancies (OVs) to enhance photocatalytic PDS activation for TC degradation, achieving 92.3% TC removal and 66.2% TOC elimination[33,34]. Despite its promising properties, pure BiOCl still suffers from rapid electron-hole recombination and limited visible-light absorption, which constrain its practical application. Therefore, rationally designing composite photocatalysts to enhance charge separation and extend light utilization remains a key research direction.

In this study, a recyclable BiOCl/MXene heterojunction photocatalyst was synthesized via a conventional hydrothermal method and employed for PMS activation to degrade FA. The catalyst design aimed to enhance FA degradation efficiency, elucidate interfacial charge-transfer behavior, and reveal degradation pathways. Comprehensive structural and photoelectrochemical characterizations clarified the structure-activity relationship and stability. Meanwhile, the stability and applicability of the material were investigated. Radical trapping and EPR analyses identified dominant reactive species and confirmed the mechanism of the synergistic oxidation effect between photocatalysis and PMS. Combined UV-vis and 3D-EEM analyses further elucidated degradation pathways.

-

All chemical reagents and solvents used in this study were of analytical grade, and deionized water was employed throughout the experiment (Supplementary Text S1).

Fabrication of BiOCl/MXene

-

As shown in Supplementary Fig. S1, the BiOCl/MXene photocatalyst was synthesized via a traditional hydrothermal method (Supplementary Text S2).

Characterization

-

The microscopic morphology of the material was observed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). The crystal structure and surface elemental chemical states of the material were characterized by XRD and XPS (Supplementary Text S3).

Evaluation of catalytic performance

-

The experiment on the degradation of FA via photocatalytic activation of PMS by BiOCl/MXene was conducted in a photochemical reactor (Supplementary Fig. S2 & Supplementary Text S4).

Analytical methods

-

To investigate the evolution patterns of FA during degradation (including its decomposition mechanism and changes in chemical composition), a fluorescence spectrophotometer was used to perform 3D-EEM fluorescence spectral analysis (Supplementary Text S5). A TOC analyzer was employed to monitor the dynamic changes in dissolved organic carbon (DOC) concentration throughout the degradation reaction, and this indicator can serve as a quantitative basis for evaluating the mineralization degree of FA[35]. In addition, the specific ultraviolet absorbance at a target wavelength (SUVAx) is a key parameter reflecting the aromaticity and molecular weight characteristics of FA. It is calculated as the ratio of the ultraviolet absorbance at the target wavelength (Ax, measured by an ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer) to the corresponding DOC concentration at the same reaction time point[36]. To study the mechanism of FA degradation via photocatalytic activation of PMS, the light absorption performance of the material and the separation efficiency of photogenerated electron-hole pairs were tested. The mechanism of photocatalytic PMS activation was inferred through the analysis of the FA solution degradation process (Supplementary Text S6).

-

The 3D microtopography of the material was characterized by SEM. As shown in Fig. 1a, pure BiOCl nanoparticles exhibit a typical nanosheet-like structure with irregular arrangement and agglomeration. Pure MXene resembles an accordion-like morphology (Fig. 1b), presenting a layered structure. Its glaze surface contains narrow slits, which are conducive to the dispersion of BiOCl nanoparticles[37]. When BiOCl is combined with MXene to form the BiOCl/MXene composite, it can be observed that BiOCl is loaded onto MXene (Fig. 1c). Combined with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS, Fig. 1d) and elemental mapping (Fig. 1e), the mass and atomic percentages of each element were obtained. This further confirms the successful introduction of Bi, O, Ti, C, Cl, and other elements in BiOCl/MXene, verifying the uniform distribution of BiOCl on MXene. To further explore the internal structure of BiOCl/MXene, TEM characterization was performed on this photocatalytic material (Fig. 1f, g). In the HRTEM image of the catalyst (Fig. 1h), the (101) and (110) crystal planes of BiOCl (PDF#06-0249) can be observed, with their interplanar spacings (d-values) of approximately 2.848 Å and 3.882 Å, respectively[38,39]. Meanwhile, the (002) crystal plane of MXene (Ti3C2) was also observed, and the interplanar spacing of this crystal plane is approximately 4.696 Å[40]. Based on the above, this confirms the successful synthesis of the BiOCl/MXene catalyst.

Figure 1.

(a) SEM Image of BiOCl. (b) SEM image of MXene. (c) SEM image of BiOCl/MXene. (d) EDS. (e) Elemental mapping of BiOCl/MXene. (f) TEM image. (g) HRTEM image. (h) Elemental lattice of BiOCl/MXene.

To further analyze the crystal structure of the as-prepared BiOCl/MXene powder catalyst, XRD analysis was performed. Figure 2a presents the XRD patterns of the powder catalysts. The MXene used in the experiment was purchased directly, with Ti3C2 as its main component. The diffraction peaks at 34.1°, 36.7°, 60.7°, and 72.1° correspond to the standard MXene card (PDF#98-000-0264). The peaks at 12.1°, 24.2°, 25.9°, 32.6°, and 33.5° are consistent with the standard BiOCl card (PDF#06-0249)[41]. Although the low MXene content results in less distinct characteristic peaks, the presence of MXene is confirmed by the characteristic peaks at 42.6° and 60.6°. The coexistence of diffraction peaks of BiOCl and MXene in the composite indicates good integration between the two components, verifying the successful preparation of the composite. Specific surface area and pore size distribution are critical properties affecting the catalytic performance of catalysts[42]. The pore size and surface characteristics of the catalysts were analyzed via nitrogen adsorption-desorption experiments. As shown in Fig. 2b, the adsorption isotherm of MXene belongs to Type III with an H3-type hysteresis loop, indicating the presence of large pores formed by vertical smooth pores—this is also confirmed by its SEM images[43]. In addition, the isotherms of BiOCl and BiOCl/MXene are classified as typical Type IV curves (IUPAC classification) with H3-type hysteresis loops, demonstrating that the catalysts possess a mesoporous structure, which is beneficial for enhancing catalytic performance. As shown in the inset, the pore sizes of all three materials are concentrated in the range of 2 to 10 nm. The average pore sizes of BiOCl, MXene, and BiOCl/MXene are 8.59, 5.01, and 9.34 nm, respectively—further confirming their mesoporous nature. The specific surface area of BiOCl/MXene (41.73 m2 g−1) is larger than that of BiOCl (9.17 m2 g−1) and MXene (9.72 m2 g−1). A higher specific surface area provides more active sites, thereby improving the catalytic performance of the as-prepared catalyst[44]. The Ti3C4 characteristic peaks of MXene are retained in the composite, which confirms that MXene can form a stable crystalline composite structure with BiOCl, preventing excessive agglomeration of BiOCl nanoparticles. In addition, its own macroporous structure can complement the mesoporous structure of BiOCl, significantly increasing the specific surface area of the composite catalyst to 4.5 times that of BiOCl and 4.3 times that of MXene, and increasing the number of active sites for catalytic reactions. The pore structure of MXene can also act as 'mass transfer channels', facilitating the contact between reaction substrates and active sites, and further enhancing the catalytic performance of the composite.

Figure 2.

(a) XRD patterns. (b) Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms with pore size distribution curves (inset). (c) XPS survey spectra of different materials. (d) Bi 4f. (e) O 1s. (f) Cl 2p. (g) Ti 2p. (h) C 1s high-resolution XPS spectra.

To further investigate the atomic valence states, bonding characteristics, and electron transfer behavior in the material, XPS measurements were conducted on the photocatalytic material. In the full XPS spectrum of BiOCl/MXene (Fig. 2c), the presence of Bi, O, Cl, Ti, and C elements is clearly observed—confirming the successful synthesis of the BiOCl/MXene composite catalyst. Under hydrothermal conditions (160 °C, 10 h), effective interfacial interactions are formed between BiOCl and MXene. Since the work function of BiOCl is lower than that of MXene, electrons transfer from BiOCl to MXene, resulting in an increased electron cloud density around Bi, O, and Cl atoms in BiOCl. XPS analysis reveals that the binding energies of Bi 4f, O 1s, and Cl 2p all shift toward lower energies, confirming the effective transfer of interfacial charges. Meanwhile, the oxygen-containing functional groups (–O, –OH) on the MXene surface undergo a coordination interaction with Bi3+ in BiOCl, and a characteristic peak attributed to the C–O bond appears at 288.06 eV in the C 1s spectrum, indicating the formation of Bi–O–C bonds. This chemical bonding not only enhances the interfacial bonding strength between BiOCl and MXene, preventing the detachment of components during the reaction process, but also further promotes the transfer of interfacial charges. As shown in Fig. 2d, two strong characteristic peaks of Bi 4f appear at 159.20 and 164.51 eV, corresponding to the orbital electron transitions of Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2, respectively. In the O 1s spectrum (Fig. 2e), the binding energy peaks at 529.92 and 530.84 eV indicate the presence of surface-adsorbed oxygen and the formation of Bi–O bonds in BiOCl. The surface-adsorbed oxygen is associated with water molecules or hydroxyl groups on the BiOCl surface. Furthermore, in Fig. 2f, binding energy peaks at 197.91 and 199.50 eV are observed, which result from the spin-orbit splitting of the Cl 2p orbital—corresponding to the energy levels of Cl 2p3/2 and Cl 2p1/2, respectively. After the introduction of MXene, the characteristic peaks of Bi 4f, O 1s, and Cl 2p in BiOCl all shift toward lower binding energies, indicating electron transfer and strong interfacial interaction between BiOCl and MXene[45]. Fig. 2g shows the XPS spectrum of Ti 2p. The characteristic peaks of Ti 2p in BiOCl/MXene appear at 459.56 (Ti 2p3/2) and 465.69 eV (Ti 2p1/2), which are the characteristic peaks of Ti in MXene—further confirming that MXene was successfully incorporated into the composite[46]. The Ti 2p spectrum of pure MXene is dominated by characteristic peaks of Ti3+, accompanied by a small amount of Ti4+ formed by surface oxidation. After compositing, the distinctive peaks of both Ti3+ and Ti4+ shift toward higher binding energy by approximately 0.3–0.5 eV, and the proportion of Ti3+ increases from 75% to 82%. This indicates that electrons transfer from Ti atoms of MXene to BiOCl, resulting in a decrease in the electron cloud density of Ti. This process originates from the migration of electrons from the conduction band of BiOCl to MXene, which not only induces the reconstruction of the Ti electronic state but also forms a Schottky junction at the interface. The Schottky junction effectively promotes photogenerated charge separation and inhibits electron backtransfer, laying the foundation for subsequent PMS activation. Figure 2h presents the XPS spectrum of C 1s. The C 1s peaks of MXene are located at 282.00 and 284.88 eV (corresponding to C-C bonds). For BiOCl/MXene, the C 1s peaks appear at 284.84 (C-C bonds) and 288.06 eV, with obvious changes. These shifts and variations in elemental characteristic peaks further confirm the successful synthesis of the BiOCl/MXene composite photocatalyst. The C 1s spectrum further confirms the existence of Bi–O–C covalent bonds at the interface. Compared with the dominant C–C and C–O peaks in pure MXene, the composite material exhibits a characteristic C–O–Bi peak at 288.2 eV, and the intensity of the C–O peak is significantly enhanced. This change is attributed to the coordination reaction between Bi3+ in BiOCl and the –OH groups on the MXene surface, forming stable chemical bonding. The C–O–Bi bond not only enhances the interfacial binding strength and maintains the stability of the Schottky junction structure but also constructs an efficient electron transport channel from BiOCl through the interfacial bond bridge to the MXene framework. This accelerates the migration of electrons to the MXene surface, promotes the reduction of PMS to generate •O2−, and ultimately improves the FA degradation performance.

Performance of the photocatalytic-PMS system

Photocatalysis-PMS synergistic effect

-

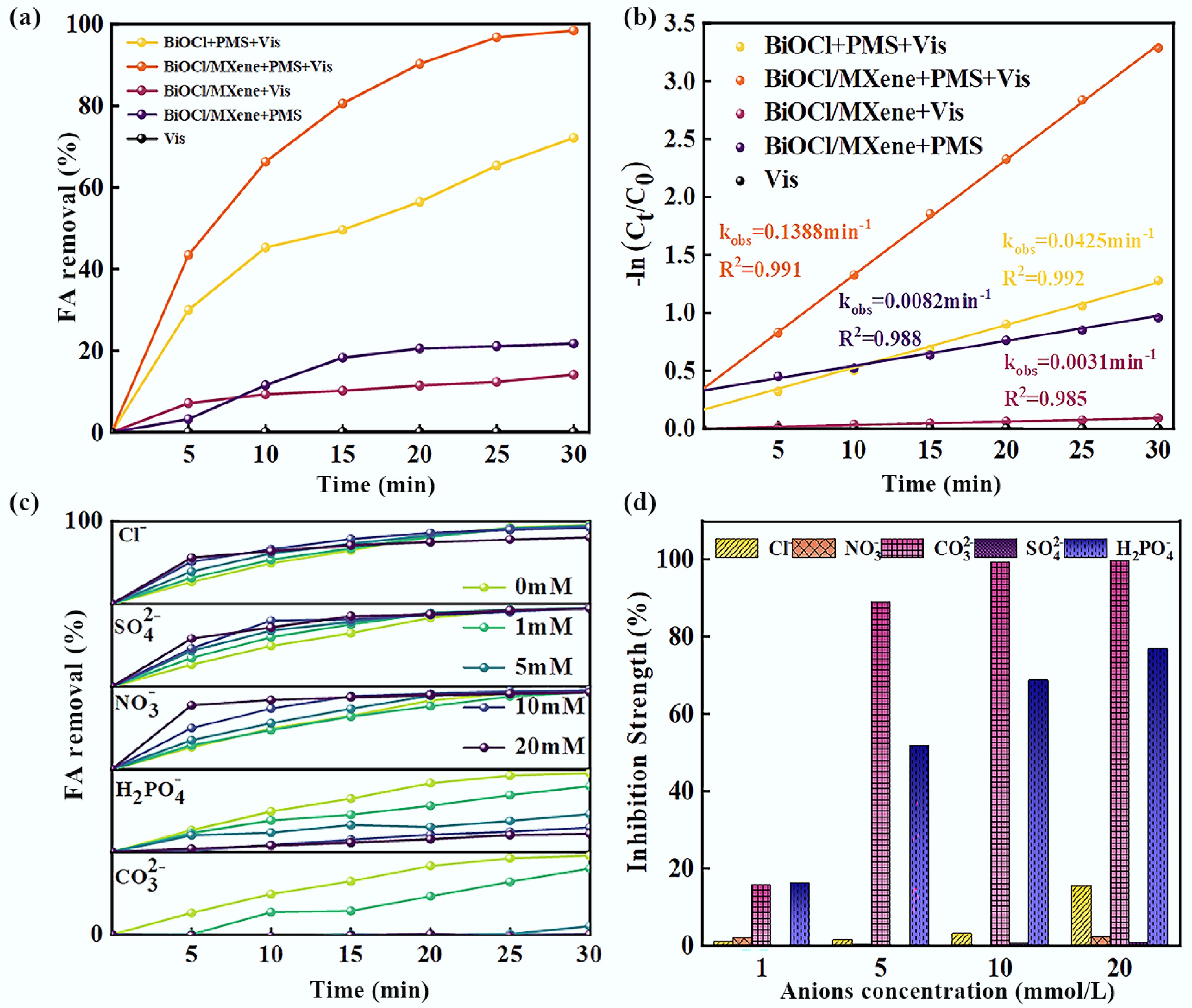

To clarify the synergistic mechanism of BiOCl/MXene for photocatalytic activation of PMS, this study evaluated the catalytic performance of the photocatalytic material by measuring the degradation efficiency of FA. First, the synthesis conditions of the BiOCl/MXene composite catalyst were optimized, with synthesis temperature, synthesis time, and MXene dosage as variables to screen for the optimal parameters (Supplementary Text S7). The results of a series of experiments showed that the optimal synthesis conditions were a synthesis temperature of 160 °C, a synthesis time of 10 h (It can meet the requirements of short-term degradation efficiency and support subsequent synergistic catalytic mechanism exploration as well as cyclic usability verification)[47], and a MXene dosage of 15% (Supplementary Fig. S3). This optimization result is consistent with findings from similar studies. After preparing the composite catalyst under the optimal conditions, the FA removal performance of different reaction systems was compared (Fig. 3a). The results showed that the BiOCl/MXene + PMS + Vis system exhibited the highest catalytic activity, achieving a FA removal rate of 98.43% within 30 min. In contrast, the FA removal rate of the BiOCl + PMS + Vis system was only 72.16%. The FA degradation rates of the sole photocatalysis system (14.16%) and PMS-only system (21.77%) were much lower than those of the photocatalysis-PMS synergistic systems. Notably, no FA degradation occurred under sole visible light irradiation. Kinetic analysis revealed (Fig. 3b) that the degradation rate constant (k) of the BiOCl + PMS + Vis system was 0.0425 min−1. After compositing with MXene, the k value of the BiOCl/MXene system increased by 3.27-fold (k = 0.1388 min–1), confirming that the introduction of MXene can significantly promote the process of BiOCl-mediated photocatalytic activation of PMS for FA degradation. Additionally, the k value of the sole photocatalysis system (0.0031 min−1) accounted for only 2.23% of that of the Vis + PMS system, indicating that PMS is the core donor of ROS in this synergistic system. Without PMS, sole photocatalysis cannot achieve effective FA degradation. The k value of the PMS-only system (0.0232 min–1) was only 16.7% of that of the Vis + PMS system, demonstrating that visible light can excite the catalyst to generate photogenerated carriers. Furthermore, this study evaluated the photo-Fenton synergistic effect by comparing the degradation rates of the photocatalytic system and the heterogeneous Fenton-like reaction. To further elaborate on the synergistic mechanism between photocatalysis and Fenton-like reaction, a synergy equation was used to quantify the synergistic effect, which is presented as follows:

$ Synergy\; index=\dfrac{k}{k_p+k_F} $ (1) where, k, kP, and kF are defined as the degradation rate constant of the photo-Fenton system, the heterogeneous photocatalytic system, and the PMS-only system, respectively[48]. The calculation result showed that the synergy factor of the BiOCl/MXene system was 5.28, indicating a significant synergistic effect between the photocatalytic and PMS oxidative degradation processes. From the perspective of the photocatalytic mechanism, Wang et al. reported the 'hole-dominated degradation' phenomenon in TCNQ-modified BiOIO3, which confirms the core role of carriers (holes) in photocatalytic reactions[49]. In this study, the rapid transfer of photogenerated carriers in the BiOCl/MXene system may synergistically activate the photo-Fenton process and accelerate degradation through a similar 'carrier-driven reaction' mechanism.

Figure 3.

(a) Degradation efficiency profiles, (b) pseudo-first-order kinetic plots of FA in different reaction systems, (c) effects of anions on FA degradation experiment, and (d) comparison of inhibition strength based on the percentage decrease in fa removal efficiency (Experimental conditions: pH = 5.28, UV = 300 W; FA = 100 mg/L; BiOCl/MXene = 0.8 g/L; PMS = 2.0 mmol L−1).

For the photocatalytic activation of the PMS degradation experiment, the volume of the reaction solution was 100 mL, the light intensity was 296 mW cm–2, the wavelength (λ) of the light source was 420 nm, and the illumination area was approximately 44.2 cm2. The photocatalytic apparent quantum yield (AQY) was calculated according to the following formula:

$ \mathrm{AQY}=\dfrac{{\text{N}}_{\text{e}}}{{\text{N}}_{\text{p}}}\times \mathrm{100}{\text{%}} $ (2) $ {\text{N}}_{\text{e}}={\text{n}}_{\text{FA,degraded}}\times {\mathrm{n}}_{\mathrm{e}/\text{FA}}\times {\text{N}}_{\text{A}} $ (3) $ {\text{n}}_{\text{FA,degraded}}=\dfrac{{\text{C}}_{\text{FA,0}}\times {\rm V}\times {\eta}}{{\text{M}}_{\text{FA}}}$ (4) ${\text{N}}_{\text{P}}=\dfrac{\text{E}\lambda}{\text{hc}}$ (5) where, Ne refers to the total number of effective electrons involved in the FA degradation reaction; Np represents the total number of photons incident on the catalyst surface; nFA, degraded is the moles of FA degraded within 30 min; ne/FA is the number of electron transfers required for the degradation of each FA molecule; NA is Avogadro's constant (6.02 × 1023 mol−1); CFA, 0 denotes the initial concentration of FA; ƞ represents the FA degradation rate; h is Planck's constant (6.62 × 10−34 J·s); c is the speed of light (3.0 × 108 m s−1); E stands for the total energy of incident light, with the incident light wavelength λ being 420 nm. Finally, the AQY was calculated to be approximately 1.33%, which indirectly confirms the effectiveness of the photocatalysis-PMS synergistic mechanism. The presence of PMS not only acts as a precursor of ROS but also reduces carrier recombination by capturing photogenerated electrons, further improving the effective utilisation efficiency of carriers, thereby achieving stable high degradation efficiency and excellent reaction kinetic performance.

Influence and optimization of reaction conditions

-

To systematically clarify the regulation laws and intrinsic mechanisms of different experimental conditions on the efficiency of BiOCl/MXene composite catalyst for photocatalytic activation of PMS to degrade FA, this study focused on investigating the effects of four key variables: catalyst dosage, initial FA concentration, solution pH value, and PMS dosage. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S4a, with the BiOCl/MXene composite catalyst dosage increasing from 0.2 to 1.0 g L−1, the FA degradation rate exhibited a characteristic trend of first increasing and then decreasing. When the dosage reached 0.8 g L−1, the FA degradation efficiency peaked at 98.43%; a further increase in dosage to 1.0 g L−1 resulted in a slight decline. The essence of this phenomenon lies in the fact that an appropriate dosage enhances the exposure density of active sites on the catalyst surface, providing sufficient reaction sites for PMS activation and efficient separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs. However, excessive dosage intensifies the light scattering effect in the system, impairs the effective excitation efficiency of incident light, and simultaneously increases the mass transfer resistance of the solution, ultimately inhibiting the reaction kinetic process[50]. When the initial FA concentration increased from 20 to 100 mg L−1 (Supplementary Fig. S4b), its degradation rate remained above 90% throughout, fully demonstrating that the BiOCl/MXene composite catalyst possesses excellent resistance to pollutant concentration interference and stable, high-efficiency degradation performance. Nevertheless, the degradation rate showed a negative correlation trend of gradual decline with increasing concentration. The core mechanism can be attributed to the fact that high-concentration FA molecules compete with PMS for adsorption on the catalyst's active sites; meanwhile, they exacerbate the light attenuation effect in the solution, leading to a reduction in the generation of photogenerated reactive oxygen species (ROS, e.g., •OH, SO4•−), thereby decreasing the degradation efficiency[51]. For the effect of solution pH, data in Supplementary Fig. S4c show that the FA removal rate is significantly dependent on pH. Within the range from strong acidity to weak alkalinity (pH 3–9), the degradation rate remained above 90%, which was significantly higher than that in the strong alkaline environment (pH 11, degradation rate 88.78%). The intrinsic reason is that pH regulates the zeta potential of the BiOCl/MXene surface, the dissociation forms of PMS (H2O2, HO2−, O22−), and the distribution of FA occurrence forms. This directly affects the interfacial interaction intensity among the catalyst, pollutant, and PMS, the selectivity of ROS generation pathways, and the contact efficiency between FA molecules and active sites[52]. Results in Supplementary Fig. S4d indicate that there is a clear optimal value of PMS concentration for degradation performance. When the concentration increased from 1 to 2 mmol L−1, the FA removal rate improved significantly; a further increase to 3 mmol L−1 led to a decrease instead. The regulation mechanism of this phenomenon is that an appropriate amount of PMS can act as an efficient ROS precursor to enhance the oxidative activity of the system, while excessive PMS triggers quenching reactions between ROS[53], resulting in a reduction in the concentration of effective ROS and ultimately inhibiting the FA degradation process.

Figure 3c shows the effect of different anion concentrations on FA removal efficiency. Cl− exerted a slight inhibitory effect on FA removal, and this inhibition became more pronounced when the Cl− concentration ranged from 10–20 mM. Cl− can react with •OH to form chlorohydroxyl radicals (ClOH•−), which then decompose rapidly into) •OH and Cl−. At this stage, the reaction rates of these two species are comparable, resulting in minimal impact on pollutant degradation. However, under acidic conditions, ClOH•− can further react with H+ to generate Cl•, and the presence of Cl− thus exerts a certain inhibitory effect on pollutant degradation[54]. Nitrate ions (NO3−) had no negative effect on FA removal; in fact, the FA degradation efficiency increased slightly when the NO3− concentration was 10 mM. This is because nitrate exhibits a certain degree of photosensitivity—under light irradiation, it induces the generation of •OH and nitrogen-containing radicals. This process increases the radical concentration in the system, thereby accelerating the FA removal rate[55]. CO32− inhibited FA removal: when the CO32− concentration reached 1 mM, the FA removal rate was only 80.13% after 30 min; when the concentration increased to 5–20 mM, almost no FA degradation occurred. This is mainly due to the hydrolysis of CO32−, which increases the solution pH and further reduces photocatalytic efficiency. Additionally, CO32− can act as a h+ scavenger—its presence consumes h+, leading to a decrease in photocatalytic activity. Increased CO32− concentration also disrupts the buffering capacity of the system, causing changes in the types and concentrations of active species during the reaction[56]. SO42− exerted a certain inhibitory effect on the photocatalytic degradation of FA by the catalyst, but the effect was not significant. When the SO42− concentration was ≤ 20 mM, there was no obvious difference in the final FA removal rate[57]. H2PO4− inhibited the photocatalytic degradation of FA by the catalyst, and the inhibitory effect strengthened with increasing H2PO4− concentration. This is because H2PO4− has high reactivity—it can react with both h+ and •OH, resulting in the scavenging of active species in the system[58]. Figure 3d indicates that different anions had varying effects on the performance of BiOCl/MXene for photocatalytic FA degradation. The order of inhibition strength is: CO32− > H2PO4− > Cl− > SO42−, while NO3− had almost no impact. Notably, under the condition of low-concentration coexisting substances, the photocatalytic performance of BiOCl/MXene was not significantly interfered with, and the degradation rate remained above 80%. This phenomenon confirms that the composite photocatalyst possesses excellent anti-interference ability and system stability.

Reusability and universality

-

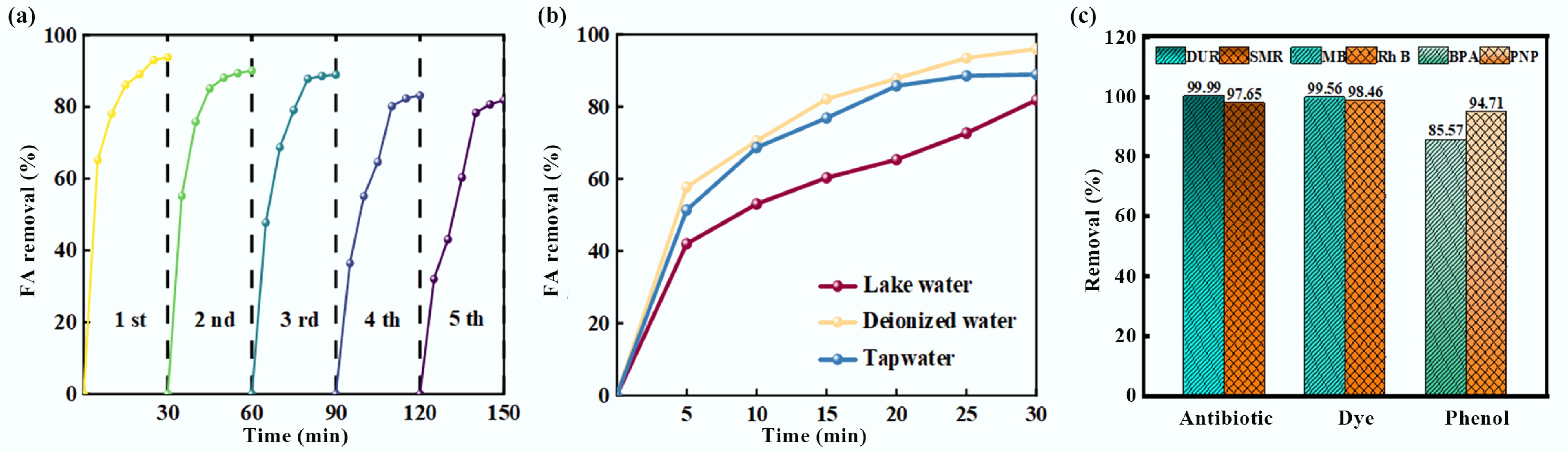

To comprehensively clarify the practical application value of the BiOCl/MXene photocatalytic PMS activation system, this study conducted a systematic evaluation from three dimensions: cycling stability, water matrix adaptability, and substrate universality. Since BiOCl/MXene is non-magnetic (Supplementary Fig. S5), the material was recovered via the precipitation method. Figure 4a shows that after five cycles of use, the composite still maintained high efficiency for FA degradation, with no significant decline in the overall removal rate (the FA degradation rate remained above 80% in the 5th cycle). Combined with material characterization, this confirms the structural integrity and catalytic activity persistence of the composite, effectively overcoming the common challenges of active site loss and structural collapse faced by photocatalysts during cyclic use[59]. To assess the system's water matrix adaptability, the degradation behavior of FA in deionized water, tap water, and lake water systems was compared (Fig. 4b). The FA removal rate was the highest in deionized water (98.43%), followed by tap water. In the lake water system, the degradation rate decreased slightly due to the presence of high-concentration natural organic matter (NOM) and coexisting ions (e.g., HCO3−, Ca2+)[60]. However, the removal rate still reached over 70% within 30 min, indicating that the system has excellent resistance to complex matrix interference and can meet the purification needs of various practical water bodies. For substrate universality evaluation, Fig. 4c shows that the system exhibited high-efficiency degradation performance for three types of typical organic pollutants: antibiotics (doxycycline, DUR; sulfamethoxazole, SMR), dyes (methylene blue, MB; rhodamine B, RhB), and phenols (bisphenol A, BPA; nonylphenol, NP). The removal rates of antibiotics reached up to 99.99% (DUR) and 97.65% (SMR); the removal rates of dyes were 99.56% (MB) and 98.46% (RhB); although the phenols had slightly lower removal rates due to the stability of their molecular structures, the removal rates of BPA and NP still reached 85.57% and 94.71%, respectively. This broad-spectrum degradation property originates from the synergistic oxidation of multiple active species in the system, such as •OH, SO4•−, and 1O2[61], enabling the system to address complex and diverse organic pollution scenarios in water bodies.

Figure 4.

(a) Cycling performance, (b) FA degradation rates in different water matrices, and (c) degradation rates of different pollutants for the BiOCl/MXene photocatalytic PMS activation system (Experimental conditions: pH = 5.28, UV = 300 W; FA = 100 mg L−1; BiOCl/MXene = 0.8 g L−1; PMS = 2.0 mmol L−1).

Mechanistic insights into the photocatalytic-PMS system

Band structure and charge separation efficiency

-

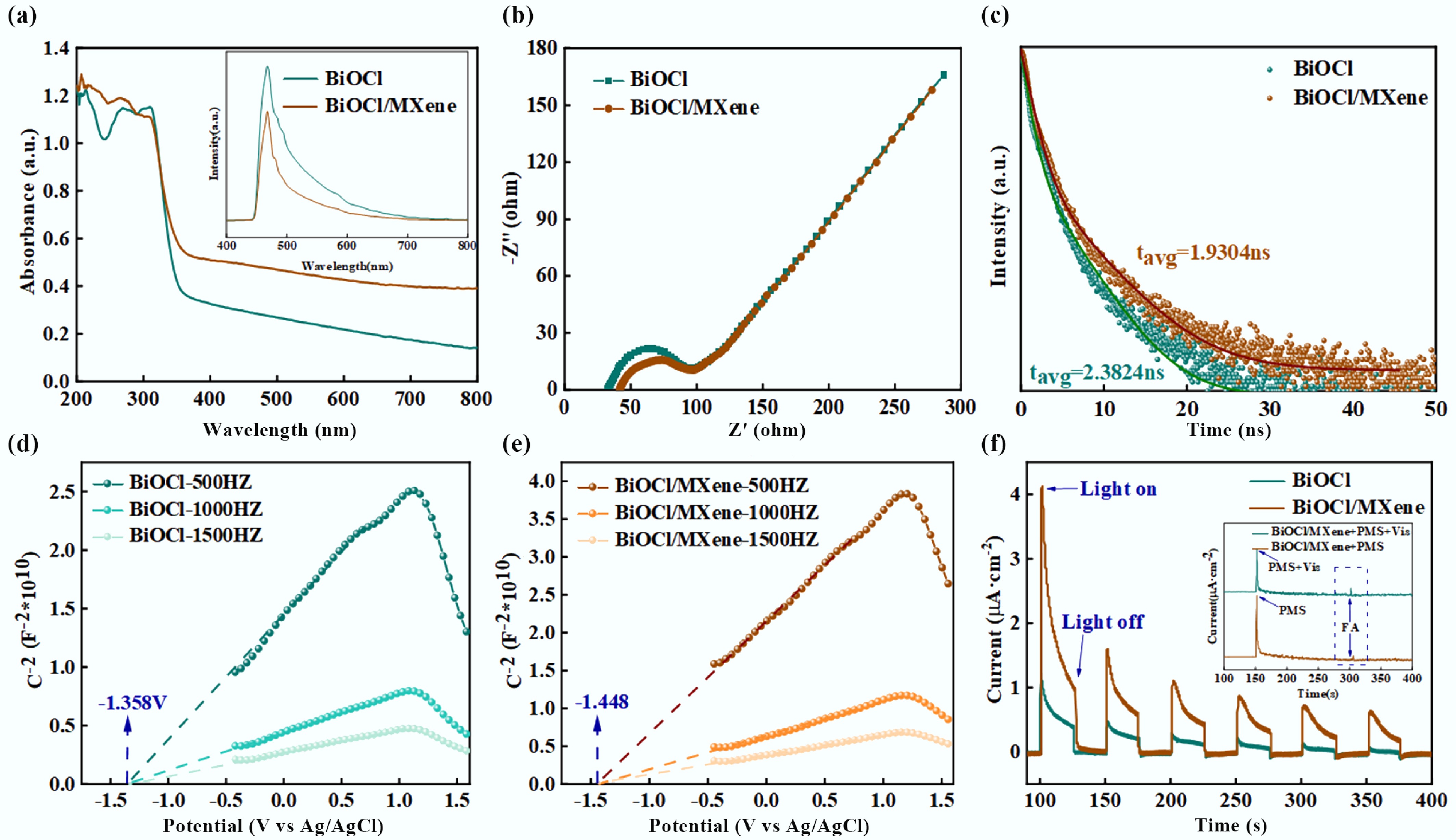

In photocatalytic reactions, photocatalytic efficiency is determined by three key factors: light absorption efficiency, photogenerated carrier separation efficiency, and interfacial catalytic reactions. The energy band structure significantly influences both the redox capacity and light absorption performance of photocatalysts. Figure 5a presents the UV-Vis absorption spectra of BiOCl and BiOCl/MXene. Both BiOCl and BiOCl/MXene exhibit strong absorption in the UV region (200–350 nm), reflecting their ability to absorb UV light. The absorbance decreases beyond 350 nm, with a more pronounced decline for BiOCl. In contrast, BiOCl/MXene shows significantly higher absorbance in the visible light region (400–800 nm) compared to BiOCl, indicating that the introduction of MXene effectively enhances the visible light absorption capacity of the composite[62]. To evaluate the separation efficiency of photogenerated carriers, photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were performed on the catalysts. As shown in the inset, BiOCl exhibits the strongest fluorescence intensity, while the BiOCl/MXene composite shows the weakest. Generally, fluorescence emission intensity is inversely proportional to the density of recombination centers—i.e., weaker fluorescence intensity indicates higher electron-hole pair separation efficiency. The significantly reduced PL intensity of BiOCl/MXene composite confirms that MXene introduction effectively promotes the separation of photogenerated carriers, enabling more carriers to participate actively in the photocatalytic reaction process. Typically, a smaller arc radius in the Nyquist plot indicates lower charge transfer resistance, which is more favorable for electron transfer[63]. As shown in Fig. 5b, the arc radius of BiOCl/MXene composite is smaller than that of pure BiOCl, demonstrating the superior charge transfer capability of BiOCl/MXene. In summary, the BiOCl/MXene composite exhibits excellent photocatalytic performance due to its efficient carrier separation efficiency and superior charge transfer ability. Time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) spectroscopy was used to investigate photogenerated carrier lifetime and recombination kinetics. In Fig. 5c, both BiOCl and BiOCl/MXene were fitted with a double-exponential model. The fitting parameters and R2 values (0.9929 for BiOCl and 0.9914 for BiOCl/MXene) indicate good model adaptability. In comparison, BiOCl/MXene shows faster decay of luminescence intensity. Combined with the fitted carrier lifetime parameters, this suggests that MXene introduction accelerates the recombination or migration of photogenerated carriers, alters carrier dynamics, and facilitates improved carrier utilization efficiency in applications such as photocatalysis.

Figure 5.

(a) UV–vis DRS with inset PL spectra, (b) EIS Nyquist plots, (c) time-resolved fluorescence decay curves, (d), (e) Mott-Schottky plots, (f) photocurrent response curves with inset photocurrent responses under different conditions.

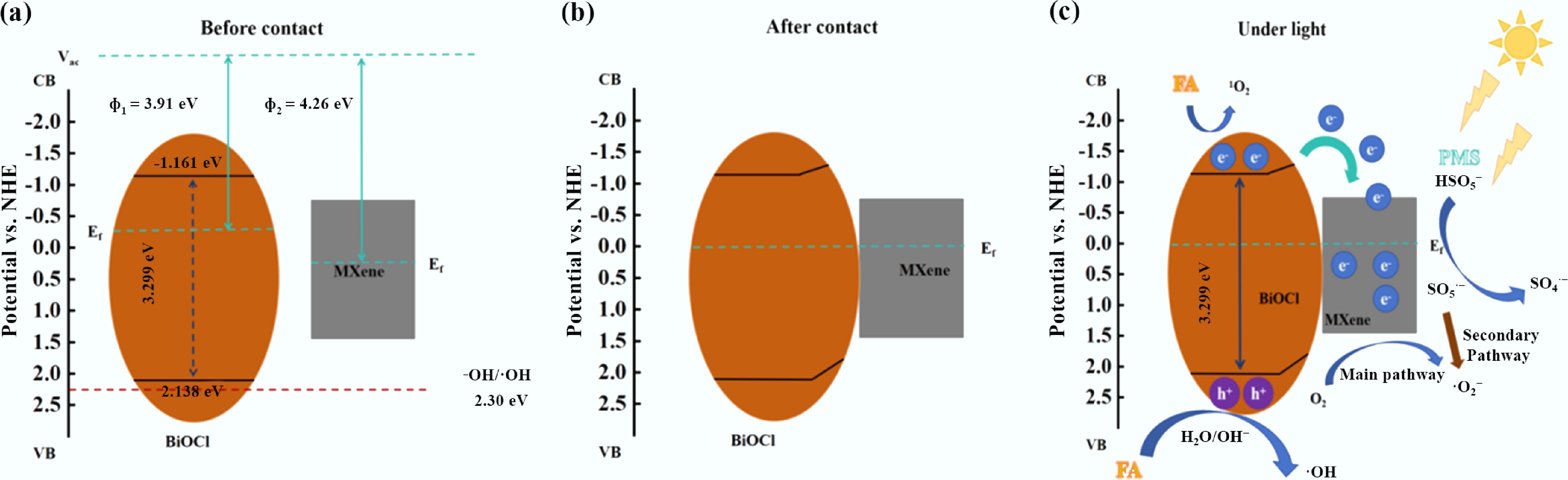

From the Mott-Schottky curves in Fig. 5d, e, the positive slopes of both BiOCl and BiOCl/MXene indicate that they are n-type semiconductors. The flat band potentials were determined from the intersection of the curves with the potential axis: BiOCl has a flat band potential of approximately –1.358 V vs Ag/AgCl, and BiOCl/MXene has approximately –1.448 V vs Ag/AgCl. Using the conversion formula E(NHE) = E(Ag/AgCl) + 0.197 (V), these were converted to potentials vs the normal hydrogen electrode (NHE): BiOCl is approximately –1.358 + 0.197 = –1.161 eV, and BiOCl/MXene is approximately –1.448 + 0.197 = –1.251 eV. For n-type semiconductors, the flat band potential (EFB) is close to the conduction band potential (ECB) and lies approximately 0.1–0.3 eV below the conduction band. Thus, the conduction band potential of BiOCl (ECB, BiOCl) is estimated to be between –1.061 (0.1 eV above the flat band potential) and –1.261 eV (0.3 eV above the flat band potential), while that of BiOCl/MXene (ECB, BiOCl/MXene) is between –1.151 and –1.351 eV. BiOCl shows the most significant increase at 500 Hz with the highest peak, and its initial reduction potential is approximately –1.358 V; as the frequency increases (1,000, 1,500 Hz), the amplitude of the increase and peak value gradually decrease. BiOCl/MXene also exhibits a noticeable increase at 500 Hz, with an initial reduction potential of approximately –1.448 V, which is more negative than that of BiOCl—indicating that the reduction reaction occurs more readily after BiOCl is composited with MXene. Additionally, BiOCl/MXene shows higher values than BiOCl at all frequencies, suggesting that MXene compositing enhances capacitance-related properties, promotes electron transport, or provides more active sites. The photocurrent response data in Fig. 5f show that the photocurrent intensity of the BiOCl/MXene composite is significantly higher than that of pure BiOCl. It also exhibits faster response kinetics and better cyclic stability in 'on-off' light cycles. This is attributed to the high electron conductivity and 2D layered structure of MXene, which not only provides rapid migration channels for photogenerated electrons and enhance carrier separation through the heterojunction interface but also inhibits particle agglomeration and phase structure changes of BiOCl. The inset clarifies, through condition comparison, the synergistic promotion effect of PMS-mediated electron trapping and FA-induced hole consumption on carrier separation. This directly corresponds to the electron transfer chain of 'photogenerated carriers-reactive species-target pollutants' in the process of photocatalytic PMS activation for FA degradation, providing critical electrical performance support for the high-efficiency degradation mechanism of this system[64]. Moreover, the relationship between Zeta potential and pH for BiOCl and BiOCl/MXene was discussed (Supplementary Fig. S6). The isoelectric point of pure BiOCl is 5.29, and that of BiOCl/MXene is 5.48, indicating that MXene introduction shifts the isoelectric point. As pH increases, the Zeta potential of both materials decreases from positive to negative: the materials are positively charged when pH is below the isoelectric point and negatively charged when pH is above it. This change in surface charge properties is related to the protonation/deprotonation behavior of functional groups on the MXene surface.

Identification of dominant reactive species

-

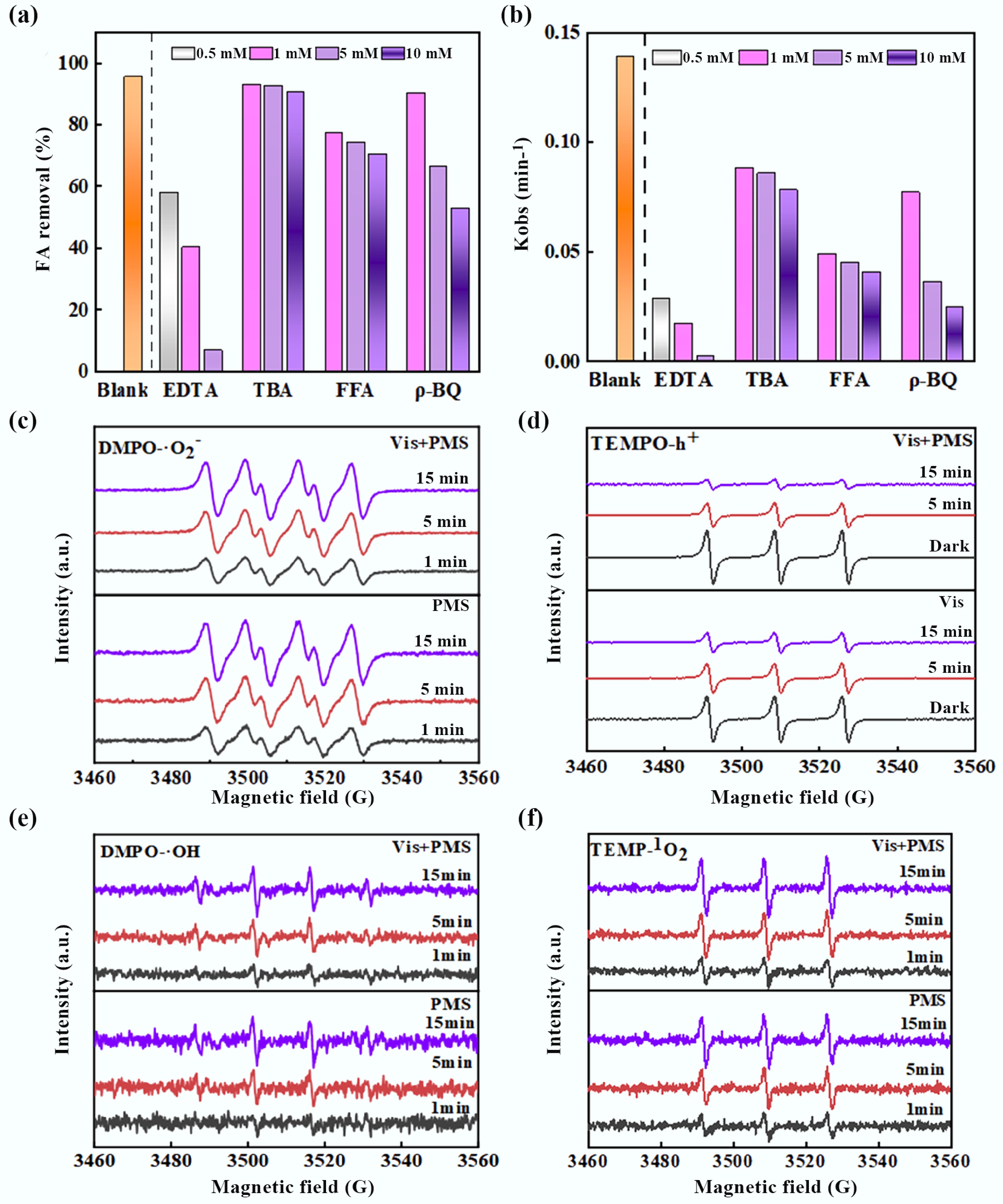

To elucidate the core advantages of the BiOCl/MXene photocatalytic PMS activation system and the contributions of active species, this study systematically investigated the regulatory mechanism of PMS activation on the generation of reactive species through scavenging experiments and EPR characterization. Specific scavengers—tert-butanol (TBA) for •OH, disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA-2Na) for h+, p-benzoquinone (ρ-BQ) for •O2−, and FFA for 1O2—were employed to conduct degradation inhibition experiments. As depicted in Fig. 6a, the FA removal efficiency decreased dramatically from 98.43% to 6.80% with increasing EDTA-2Na concentration, underscoring the dominant role of h+ in the degradation process. Concurrently, the addition of ρ-BQ reduced the FA removal rate from 98.43% to 52.67%, confirming the critical contribution of •O2−. Although TBA and FFA exhibited relatively moderate impacts on the final removal efficiency, the gradual decline in FA degradation rate with increasing scavenger concentrations indicated the synergistic involvement of multiple reactive species in the reaction. This synergistic effect originates from the efficient activation characteristics of PMS[65]. As shown in Fig. 6b, for the EDTA group, the apparent rate constant (kobs) dropped sharply from 0.0171 min−1 to nearly 0 as the concentration increased from 0.5 to 10 mM, indicating high dependency of the system on metal catalytic sites. For the TBA group, kobs continuously decreased from 0.0491 to 0.0363 min−1, confirming that •OH is one of the key reactive species. In the FFA group, kobs declined from 0.0780 min−1 (at 0.5 mM) to 0.0452 min−1 (at 10 mM), with a weaker inhibitory effect compared to the TBA group, suggesting that •OH participates in the reaction but is not the sole active species, and the contribution of 1O2 is relatively limited. For the ρ-BQ group, kobs decreased from 0.0857 to 0.0771 min−1, and this notable inhibitory trend verifies that •O2− is one of the core reactive species. To further verify and highlight the advantages of PMS, EPR characterization was performed on the material (Fig. 6c–f). 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) and 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) were utilized as spin-trapping agents to detect the generation behavior of h+ and •O2−, respectively. In the visible-light PMS system, the characteristic peaks of DMPO-•O2− adducts intensified significantly with prolonged irradiation time, and the signal intensity was substantially higher than that in the dark control, demonstrating that PMS activation continuously drives the generation and participation of •O2−. In contrast, the TEMPO-h+ signal was strong in the dark and gradually weakened under light irradiation[66], which can be attributed to the continuous generation of h+ under illumination and its subsequent reaction with the scavenger, further confirming that PMS acts in synergy with photocatalysis to promote h+ involvement in the reaction. The EPR results are highly consistent with the scavenging experiments, confirming that h+ and •O2− are the primary active species in this system[67]. Their efficient generation directly benefits from the superior activation performance of PMS: PMS not only serves as an oxidation precursor but also enhances the separation of photogenerated carriers and drives the synergistic generation of multiple reactive species through interfacial interaction with BiOCl/MXene[68]. This represents the core advantage of PMS in this photocatalytic system, providing a sufficient oxidative driving force for the highly efficient degradation of FA.

Figure 6.

(a) Active species quenching experiments, (b) corresponding pseudo-first-order rate constant, and (c)–(f) EPR radical trapping spectra during FA removal process (Experimental conditions: pH = 5.28, UV = 300 W, FA = 100 mg L−1, BiOCl/MXene = 0.8 g L−1, PMS = 2.0 mmol L−1).

Proposed synergistic mechanism

-

From three dimensions—band structure, interfacial charge regulation, and synergy of multiple active species—the core mechanism of photocatalytic activation of PMS for FA degradation by the BiOCl/MXene Schottky junction is systematically elaborated. Before contact (Fig. 7a), the CB potential of BiOCl is –1.16 eV (vs NHE), its VB potential is +2.138 eV, and its work function (Φ1) is 3.91 eV; the work function of MXene (Φ2) is 4.26 eV. MXene exhibits metal-like high conductivity and forms a Schottky junction with the semiconductor BiOCl. XPS characterization shows that MXene is dominated by metallic Ti3+, and its high conductivity is the core prerequisite for activating PMS. To further investigate the formation mechanism of the BiOCl/MXene heterojunction, after optimizing the crystal structure model of BiOCl, the band structure (Supplementary Fig. S7a) and Fermi level (Supplementary Fig. S7b) were calculated separately. The Fermi level of BiOCl is 6.99 eV, with the conduction band located below it and the valence band above it. The conduction band bottom and valence band top are distributed at different high-symmetry points (K points), confirming that it is an indirect-band-gap semiconductor structure, and the calculated band gap width is 2.69 eV. The difference in their work functions provides the driving force for interfacial charge transfer. After BiOCl comes into contact with MXene (Fig. 7b), electrons migrate from BiOCl (with a lower work function) to MXene (with a higher work function), causing the energy bands of BiOCl to bend and the Fermi levels to tend toward equilibrium. After MXene forms a Schottky junction with BiOCl, its high work function enables it to enrich photogenerated electrons, which then directionally attack the S-O bonds to weaken their energy. Ti atoms with unsaturated coordination on the surface reduce the cleavage energy barrier through coordination adsorption and valence-variable electron transfer. Additionally, the Schottky junction regulates band alignment to enhance electron injection efficiency, and experiments such as EPR have verified the increased generation of SO4•−. In the process of MXene activating PMS, its metallic-level high conductivity serves as the core premise and dominant factor determining reaction efficiency. It constructs a 'main thoroughfare' for electron transfer, which can rapidly weaken the molecular bond energy of PMS and lay the foundation for activation. In contrast, surface functional groups primarily play an auxiliary optimization role, enhancing practical efficiency by improving PMS adsorption and local activation configurations, but their function is highly dependent on the conductive framework's electron supply capacity. These two factors synergistically enhance efficiency with clear primary and secondary roles: metallic conductivity is an indispensable condition for ensuring reaction feasibility and the upper limit of reaction rate[69]. At the same time, surface functional groups are an optimization method to further improve performance on this basis. By integrating material characterization, active species verification, and degradation performance data, the core mechanism of FA degradation via photocatalytic activation of PMS by BiOCl/MXene is proposed as 'visible light-excited Schottky junction → directional charge transfer → multi-path PMS activation → synergistic oxidation by multiple active species'. The specific process is as follows (Fig. 7c): Initially, visible light irradiation on the BiOCl/MXene composite provides photon energy, exciting electrons from the VB to the CB of BiOCl, thereby generating photogenerated e−−h+ pairs. Owing to the formed Schottky junction between BiOCl and MXene, the MXene (Ti3C2 layered structure) acts as an 'electron channel', directing the transfer of electrons from the CB of BiOCl to its own surface, which significantly suppresses e−−h+ recombination. The activated charge carriers facilitate PMS activation and ROS generation through three primary pathways: The electrons enriched on MXene attack the S–O bond of PMS (HSO5−), leading to its cleavage and the generation of SO4•−. The consumption of electrons further inhibits charge recombination, as evidenced by the enhanced SO4•− signal in the EPR spectrum under the Vis + PMS system. The holes retained on BiOCl directly oxidize FA molecules (the removal efficiency of FA plummeted from 98.43% to 6.80% upon h+ scavenging by EDTA-2Na) and can also react with surface H2O/OH− to generate •OH, supplementing the oxidative capacity. Electrons on the MXene surface that do not participate directly in PMS activation can react with dissolved O2 to form superoxide •O2−, as indicated by the time-dependent enhancement of the DMPO-•O2− adduct signal in EPR. In this system, •O2− are synergistically generated through two pathways—'direct reduction' and 'PMS-mediated'—ensuring a stable supply. The direct reduction pathway provides thermodynamic driving force via the negative shift of the conduction band potential of BiOCl, achieved by the formation of BiOCl/MXene Schottky junctions. Combined with the adsorption of O2 by Ti sites on the MXene surface, which lowers the kinetic energy barrier, this pathway serves as the basic source of •O2−. The PMS-mediated pathway involves PMS capturing photogenerated electrons to form SO5•− radicals, whose disproportionation reaction efficiently increases the •O2− concentration and accounts for the majority of production, with a small amount of secondary reactions supplementing the rest. The synergistic effect can be indirectly verified experimentally: EPR measurements show that the signal intensity of •O2− in the PMS-added system is 2.3 times that in the PMS-free system, confirming the contribution of the PMS-mediated pathway. In the quenching experiment, the reduction in FA degradation rate after ρ-BQ quenching in the PMS-added system (46.5%) is significantly greater than that in the PMS-free system (less than 30%). This difference indicates that the additional •O2− generated by the PMS-mediated pathway enhances the synergistic oxidation effect with other active species, supporting the rationality of the dual-pathway synergistic mechanism for •O2− generation. The •O2− radicals directly contribute to FA oxidation (the FA removal efficiency decreased to 52.67% after •O2− scavenging by ρ-BQ) and can further disproportionate to yield 1O2. The h+ and •O2− preferentially attack the conjugated structures (e.g., aromatic rings, carboxyl groups) of FA, as evidenced by the decrease in SUVA280 (indicating aromaticity) from 2.478 to 0.264 and SUVA436 (indicating chromophores) from 0.73 to 0.008. 3D-EEM fluorescence spectra showed a strong fluorescence in Region V (humic-like substances) at 0 min, which significantly weakened after 5 min, accompanied by the emergence of weak fluorescence in Regions I/II (protein-like, small molecular intermediates), demonstrating the breakdown of macromolecular FA into smaller intermediates. Subsequently, SO4•− and •OH further oxidize these intermediates, progressively decomposing them into low-molecular-weight organic acids, and ultimately achieving partial mineralization to CO2 and H2O. TOC analysis confirmed this mineralization, showing a decrease in TOC from 78.54 to 39.31 mg L–1 after 30 min of reaction with 100 mg L–1 FA, corresponding to a mineralization efficiency of 49.95%. The involved reactions can be summarized as:

$ \rm{BiOCl}/\mathrm{MXene} + \mathrm{h}\nu \rightarrow \mathrm{BiOCl}(\mathrm{h}{^+})+\mathrm{MXene}(\mathrm{e}{^-}) $ (6) $ \mathrm{MXene}(\mathrm{e}{^-})+\mathrm{O}{_{2}}\rightarrow {\text •} \mathrm{O}{_{2}}{^-} $ (7) $ \mathrm{MXene}(\mathrm{e}{^-})+\mathrm{HSO}{_{5}}{^-}\rightarrow \mathrm{SO}{_{4}}{^{\text •}{^{ -}}}+\mathrm{OH}{^-}$ (8) $ \mathrm{BiOCl}(\mathrm{h}{^+})+\mathrm{H}{_{2}}\mathrm{O}\rightarrow {\text •} \mathrm{OH}+\mathrm{H}{^+} $ (9) $ \mathrm{BiOCl}(\mathrm{h}{^+})+\mathrm{FA}\rightarrow \mathrm{Oxidized}\;\mathrm{FA}\;\mathrm{intermediates}+\mathrm{H}{^+} $ (10) $ {\text •}\mathrm{O}{_{2}}{^-}/\mathrm{SO}{_{4}} {{^{\text •}}^-}/{\text •} \mathrm{OH}+\mathrm{FA}\rightarrow \mathrm{CO}{_{2}}+\mathrm{H}{_{2}}\mathrm{O}+\mathrm{Small}\;\mathrm{molecular}\;\mathrm{by}{\text-}\mathrm{products} $ (11)

Figure 7.

(a)–(c) Mechanism of photocatalytic activation of PMS by BiOCl/MXene catalyst for FA degradation.

Degradation process analysis of FA

Aromaticity loss and mineralization

-

SUVA is commonly used to characterize NOM. Among them, SUVA254 (specific ultraviolet absorbance at 254 nm) can predict the molecular weight and mineralization degree of organic matter; SUVA280 is used to evaluate the integrity of aromatic structures in organic matter; SUVA365 represents the molecular volume of organic matter; and SUVA436 denotes the chromophore status in NOM. TOC is often employed as an indicator to assess the degradation effect of organic matter. By measuring the difference in TOC concentration in water samples before and after treatment, the removal efficiency and mineralization degree of organic matter can be determined[70]. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S8, this study investigated the variation patterns of SUVAₓ and TOC with time in the BiOCl/MXene-PMS process system under light. The results reveal that all four SUVAₓ values exhibit a decreasing trend over time, with an extremely fast decline rate within the initial 5 min of the reaction. This indicates that most of the FA degradation and chromophore destruction can be completed rapidly after the reaction initiates—when samples were collected 5 min into the reaction, the solution was observed to become more transparent. After 30 min of reaction: SUVA254 decreased from 2.592 to 0.520, and SUVA365 decreased from 1.374 to 0.048, suggesting a continuous reduction in the molecular weight and molecular volume of FA; SUVA280 decreased from 2.478 to 0.264, and SUVA436 decreased from 0.73 to 0.008, indicating the destruction of chromophores and aromatic structures in FA. Meanwhile, the TOC of the solution also showed a decreasing trend (Supplementary Fig. S8). After reacting with 100 mg L–1 FA for 30 min, the TOC decreased from an initial 78.54 to 39.31 mg L–1, achieving a mineralization rate of 49.95%. This demonstrates that FA has been mineralized into water, carbon dioxide, and some small organic molecules.

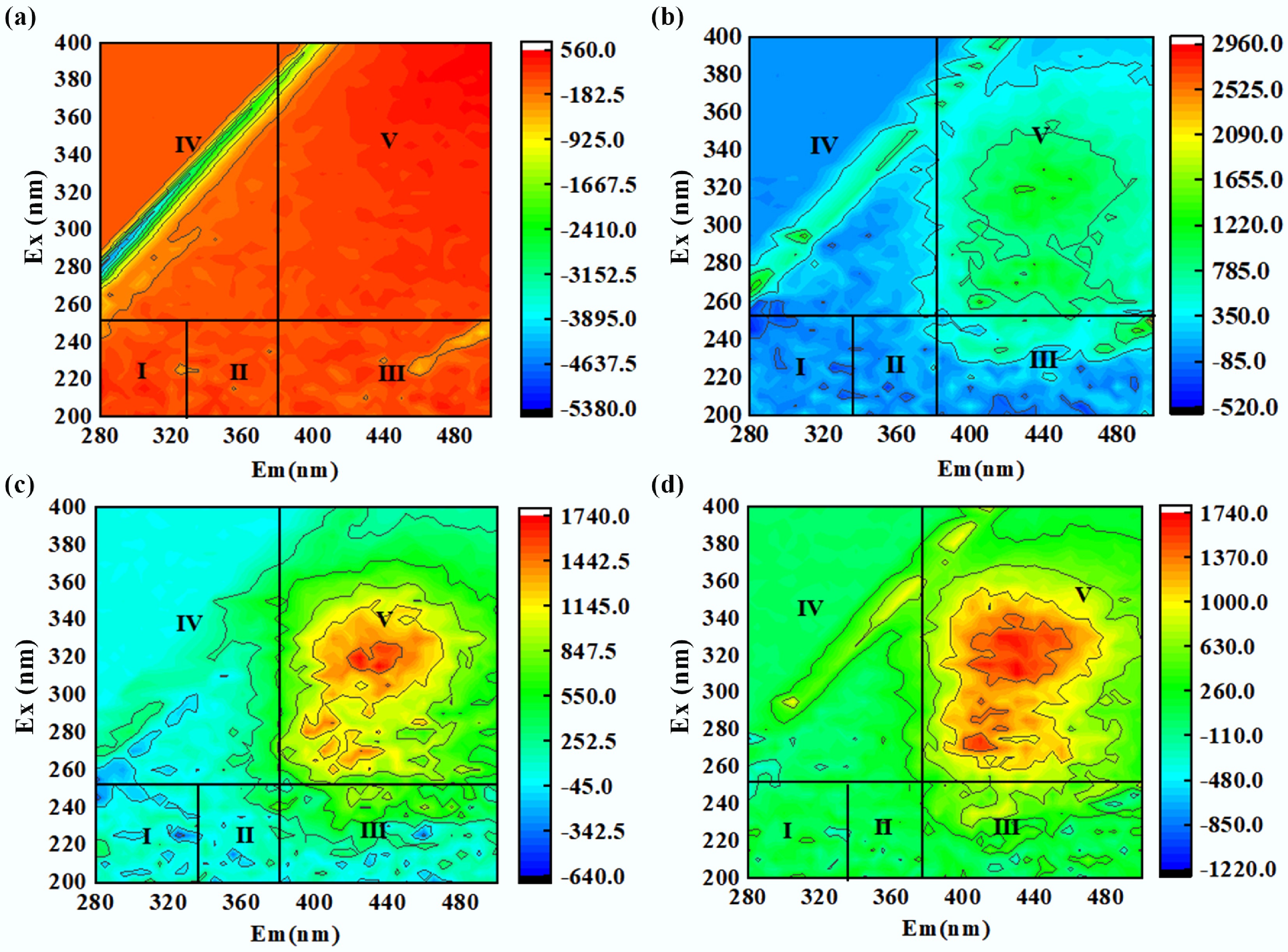

Fluorescence spectral evolution of intermediate products

-

The occurrence of fluorescence peaks is attributed to the molecular structure, chemical composition, or other properties of substances. To simplify spectral response analysis and sample scanning, the scanned spectra were divided into five regions, with the corresponding substance types for each region as follows: Regions I and II: Represent aromatic proteins in organic compounds, which are related to the structure of aromatic amino acids in NOM. Region III: Corresponds to substances containing –OH and –COOH groups in humic-like structures, including FA. Region IV: Corresponds to small-molecular structures of organic matter, such as soluble microbial metabolic by-products. Region V: Represents humic-like fluorescence[71]. At the initial reaction stage (Fig. 8a), Region V exhibited strong red fluorescence, while the fluorescence signals in Regions I and II were extremely weak. This indicates that the original FA system was dominated by humic-like components, with abundant stable conjugated aromatic structures in the molecules—these are the main structural characteristics of FA. After 5 min of reaction (Fig. 8b), the fluorescence intensity of humic-like substances in Region V decreased significantly, and at the same time, a weak increase in fluorescence was observed in Regions I and II. This change was attributed to the efficient activation of PMS by BiOCl/MXene under photocatalysis, which generated active species such as •OH and SO4•–. These active species preferentially attacked the conjugated aromatic structures of FA, breaking down macromolecular humic-like substances into a small amount of protein-like small molecular intermediates. When the reaction proceeded to 15 min (Fig. 8c), the fluorescence in Region V further attenuated, and the protein-like fluorescence in Regions I and II also began to weaken. This suggests that the active species in the system were not exhausted as the reaction progressed; they could still continuously oxidize and degrade the remaining humic-like components, while gradually decomposing the intermediates generated in the early stage. At 30 min of reaction (Fig. 8d), the fluorescence signals in all regions faded significantly—especially the characteristic red fluorescence of FA in Region V, which almost completely disappeared. This implies that the conjugated aromatic core structure of FA molecules was deeply destroyed: not only were the original humic-like components completely degraded, but the intermediates were also further converted into small molecules with no fluorescent activity (e.g., CO2, H2O, and low-molecular-weight organic acids).

Figure 8.

(a)–(d) 3D-EEM fluorescence spectra of FA during its degradation by BiOCl/MXene photocatalytic PMS activation at 0, 5, 15, and 30 min.

Combined with experimental SUVA and 3D-EEM, data and the general research conclusions on the degradation of humic substances, the degradation process of FA in the BiOCl/MXene-PMS-Vis system was analyzed[72]. In the initial stage of degradation (0–5 min), a critical period for the rapid destruction of FA structure, the core driving active species are h+ and •O2−. From the spectral data, SUVA280 decreased rapidly from the initial 2.478, and SUVA436 plummeted from 0.73 to below 0.1, indicating that the conjugated system maintaining aromaticity in FA molecules was directly attacked. Meanwhile, in the 3D-EEM spectrum, the strong red fluorescence in Region V weakened significantly at 5 min (Fig. 8a, b), further confirming the cleavage of the three-dimensional conjugated skeleton of FA macromolecules. In terms of reaction mechanism, h+ preferentially oxidises the phenolic hydroxyl groups with higher electron density in FA molecules, while •O2− specifically targets conjugated double bonds. The two synergistically disrupt the macromolecular aggregated state of FA, decomposing it into small molecule fragments containing local aromatic rings. The light transmittance of the solution is significantly improved, laying the foundation for subsequent deep oxidation. As FA degradation proceeds (5–15 min), under the continuous action of h+, •O2−, and SO4•− (PMS-activated product), the cleaved FA fragments enter the stage of aromatic ring opening. Spectrally, SUVA254 further decreased from 2.592 to below 0.8, and SUVA365 dropped from 1.374 to 0.05, indicating the destruction of aromatic ring structures and the continuous reduction of molecular volume and molecular weight. In the 3D-EEM spectrum, while the fluorescence in Region V further attenuated, weak fluorescence appeared in Region I/II (Fig. 8b, c), suggesting the formation of small molecule intermediates containing amino and carboxyl groups after aromatic ring opening. From the reaction mechanism, SO4•− (standard reduction potential 2.6 V) attacks the para/ortho C–C bonds of aromatic rings with its high oxidation capacity, triggering ring-opening reactions. •OH assists in oxidising ring-opening products to generate small molecules with multiple carboxyl groups. The TOC removal rate reaches 30%–40% at this stage, indicating that part of the organic carbon has begun to convert to inorganic carbon. In the late stage (15–30 min), the core process is the deep oxidation and partial mineralization of small molecule intermediates, reflecting the mineralisation capacity of the system. Spectral data show that all SUVAₓ values drop to low levels, indicating the almost complete destruction of the aromatic structure of FA. In the 3D-EEM spectrum, the fluorescence signals in all regions almost disappear (Fig. 8c, d), demonstrating that the fluorescently active intermediates are completely oxidised into non-fluorescent low-molecular-weight substances. In terms of products, the carboxyl and hydroxyl groups in small molecule intermediates are continuously oxidized by h+ and SO4•−, and the C–C bonds are further cleaved, with part converting into CO2 and H2O. The incompletely mineralised part exists in the form of short-chain organic acids such as acetic acid and formic acid (non-fluorescent and undetectable by 3D-EEM). Therefore, the FA removal rate reaches 98.43% while the TOC removal rate is only 49.95%.

The complete degradation pathway of FA in the system can be summarised as: FA (macromolecular aromatic conjugated structure) → h+/•O2−-driven skeleton cleavage (chromophore destruction) → SO4•−/•OH-mediated aromatic ring opening (small molecule intermediate formation) → synergistic oxidation by active species (partial mineralisation into CO2 + H2O, residual short-chain organic acids).

-

A BiOCl/MXene Schottky junction photocatalyst was successfully developed for PMS activation and efficient FA degradation under visible light. The introduction of MXene significantly increases the specific surface area from 9.17 to 41.73 m2 g–1 and optimized the band structure, facilitating charge separation and transfer. The composite achieved nearly complete FA removal (98.43%) within 30 min, exhibiting a reaction rate constant over three times higher than that of pure BiOCl, while maintaining stable activity in real water matrices and under complex ion conditions. Quenching experiments and EPR analysis confirm that h+ and •O2− were the dominant active species, revealing multi-pathway PMS activation at the heterojunction interface. UV absorption and 3D-EEM analysis demonstrated effective destruction of aromatic structures, with a TOC removal efficiency of 49.95%, evidencing strong mineralization capacity. Overall, this work offers an effective strategy for designing recyclable and stable photocatalysts and provides theoretical and technical support for advanced oxidation of refractory organics in complex water environments.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/aee-0025-0014.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Chenglong Sun: writing – original draft, methodology, formal analysis, data curation; Chunyan Yang: writing – review & editing, supervision, formal analysis; Guie Li: validation; Qiu Yang: methodology; Changhong Zhan: formal analysis; Guangshan Zhang: writing – review & editing, conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 52370174, 52500009), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (Grant No. ZR2022ME128), and Harbin Institute of Technology (Weihai) Qingdao Research Institute (Grant No. IQTA10100026).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Hydrothermally synthesized visible-light-responsive BiOCl/MXene Schottky junction photocatalysts.

Rapid and efficient fulvic acid degradation achieved via PMS activation under visible light.

The catalyst demonstrates excellent stability, recyclability and adaptability to various water conditions.

Mechanistic insights reveal key reactive species and pathways driving FA mineralization.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sun C, Yang C, Li G, Yang Q, Zhan C, et al. 2026. Synergistic photocatalysis of BiOCl/MXene activates peroxymonosulfate for enhanced fulvic acid degradation: performance and mechanism insights. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 2: e001 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0014

Synergistic photocatalysis of BiOCl/MXene activates peroxymonosulfate for enhanced fulvic acid degradation: performance and mechanism insights

- Received: 23 October 2025

- Revised: 12 December 2025

- Accepted: 23 December 2025

- Published online: 20 January 2026

Abstract: Fulvic acid (FA), a key constituent of humic substances, not only contributes to the color of aqueous environments but also leads to the formation of carcinogenic disinfection by-products during chlorination, posing serious ecological and health risks. In this study, a recyclable BiOCl/MXene Schottky junction photocatalyst was successfully synthesized via a conventional hydrothermal method and employed for the photocatalytic activation of Peroxymonosulfate (PMS) to degrade FA efficiently. The BiOCl/MXene composite achieved a high FA removal efficiency of 98.43% within 30 min under visible light. The apparent rate constant (0.1388 min−1) was 3.27 times higher than that of pure BiOCl (0.0425 min−1), revealing a remarkable photocatalysis-PMS synergistic effect (synergy factor = 5.28). The composite maintained excellent performance over a broad pH range (3–9) and at various FA concentrations (20–100 mg L−1), showing strong resistance to ionic interference and outstanding recyclability, with above 80% efficiency retained after five cycles. Characterization and mechanistic studies indicated that the incorporation of MXene significantly increased the specific surface area (41.73 m2 g−1) and improved charge separation efficiency. Trapping experiments and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) tests confirmed that h+ and O2•– serve as the dominant reactive species in the degradation process. UV-vis absorption and three-dimensional excitation–emission matrix (3D-EEM) fluorescence spectroscopy revealed the effective disruption of the aromatic structure and chromophores in FA, leading to a total organic carbon (TOC) removal rate of 49.95%. This work provides new mechanistic insights into PMS-assisted stable composite photocatalysts and offers a novel technical strategy for the removal of refractory organic pollutants.

-

Key words:

- BiOCl/MXene /

- Fulvic acid /

- Photocatalysis /

- Peroxymonosulfate /

- Synergistic effect