-

During the peripartum period, the sow experiences three physiological stages, namely pregnancy, farrowing, and lactation, and their hormones change drastically. The peripartum period has a crucial impact on the reproductive performance of sows and the growth of piglets, although it is relatively short in the overall production cycle[1,2]. A previous study showed that the duration of parturition can extend from 1.5–2 to 7–8 h if the sow gives birth to an extra piglet[3]. The prolonged parturition duration in sows probably leads to piglet asphyxia and reduced colostrum intake, thereby decreasing piglet survival rates and the economic efficiency of pig farms[4−8]. Therefore management of the peripartum to improve reproductive performance is crucial.

During the transitional stage from late pregnancy to lactation, farrowing stress leads to prolonged farrowing duration and increases the risk of postpartum diseases[9,10]. Mild stress triggers glucocorticoid secretion through the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, which, in turn, promotes the synthesis of immunoglobulins[11]. However, prolonged stress can impair the immune system's function and suppress the production of immunoglobulins[12]. The stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokine production by stressors generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to a decline in immune function[13]. In addition, farrowing sows are easily affected by factors such as nutrition, the environment, and disease, which lead to increased secretion of serum cortisol, resulting in dystocia in sows[14,15].

Studies have shown that the uterine myometrium of sows contains adrenergic and cholinergic fibers. When α-adrenergic receptors dominate, adrenaline increases the tension in the uterine myometrium, whereas when β-adrenergic receptors dominate, it leads to a reduction in tension[16,17]. The myoepithelial cells of sows' mammary glands also contain β-adrenergic receptors, and an increase in the serum cortisol concentration during stress can inhibit oxytocin-induced milk secretion[18,19]. In farrowing sows, it is evident that during stress, the primary effect is an increase in β-adrenergic receptors, leading to a decrease in uterine muscle tension, inhibiting uterine contractions and milk secretion. Therefore, it is necessary to use a β-adrenergic receptor blocker during the perinatal period of farrowing sows to improve farrowing performance and piglet growth.

Carazolol is a β-adrenergic receptor blocker characterized by its wide safety margin, high binding affinity, and prolonged duration of action. It is commonly administered to prevent sudden death in sows caused by stress during mating and farrowing[20]. Studies have shown that carazolol significantly improves the farrowing rate and shortens the duration of labor by alleviating stress[21]. Another study showed that an intramuscular injection of 0.05 mg/kg carazolol significantly shortened the farrowing time, reduced the stillbirth rate, and significantly decreased the incidence of postpartum diseases in gilts. However, this effect was not significant in multiparous sows[22]. However, to date, no studies have been reported on the effects of carazolol on piglets' growth performance or sows' return to estrus intervals after weaning.

Therefore, in present study we investigated the effects of injecting carazolol at different sites during farrowing on perinatal sows' farrowing performance and return to estrus after weaning, and piglets' growth performance.

-

Carazolol (230201) was provided by Ningbo Sansheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Ningbo, China).

Experimental animals and design

-

The experiment was conducted in March 2023 at Hebei Yongqing Ruijia Agricultural Development Co., Ltd. (Hebei, China). A total of 198 Large White × Landrace crossbred sows were randomly selected, including 99 primiparous sows and 99 multiparous sows. The primiparous sows were randomly divided into three groups: The primiparous control group (32 sows), the primiparous intramuscular group (33 sows), and the primiparous vulvar group (34 sows). The multiparous sows were randomly divided into the multiparous control group (32 sows), the multiparous intramuscular group (33 sows), and the multiparous vulva group (34 sows). Under the same feeding and management conditions, both primiparous and multiparous sows were injected with 0.02 mL/kg of carazolol after delivery of the first piglet. For the control group, normal saline was injected. The control group received a saline injection into the neck muscles, the muscular group was administered carazolol by injection into the neck muscle, and the vulvar group received an injection at the base of the vulva.

Experimental feeding and management

-

During the experiment, the sows in each group were managed in the same gestation house. They were transferred to the delivery room 7 d before the expected delivery date. The feed intake of pregnant sows was reduced to 2 kg/d during the 2–3 d before parturition. The diet used was a compound feed for periparturient sows. Lactating sows were fed 3 times a day, with 2–2.5 kg fed each time. The diet used was a compound feed for lactating sows. All experimental sows had free access to water.

Sample collection and processing

-

One hour after the injection of carazolol, we randomly selected 10 sows from each group for blood collection. The blood collection site was wiped with an alcohol swab to disinfect it. A disposable blood collection needle was inserted into the auricular vein. Once blood flow was observed, the other end of the needle was connected to a pro-coagulation tube. After the tube filled with blood, a cotton ball was pressed onto the puncture site to apply pressure and stop the bleeding.

We randomly collected umbilical cord blood from five litters of piglets. For each litter, we selected six piglets, specifically the first, second, third, sixth, sevent, and eighth piglets. We starte by gently squeezing blood from the piglet's umbilical cord into a 5-mL pro-coagulation tube, being gentle during the process to avoid damage. If the blood vessels in the umbilical cord were blocked and blood could not be easily expressed, we used scissors to cut the blood-filled bulge in the umbilical cord and then collected the blood from this spot. The collected blood samples were allowed to stand for 30 minutes at room temperature for clotting then centrifuged at 4,000 r/min for 10 minutes to separate the serum. The serum was transferred into storage tubes and stored at −20 °C until further analysis for subsequent measurements.

Measurement indicators and methods

-

The average farrowing interval, duration of farrowing, and time of final placenta expulsion were recorded separately for primiparous and multiparous sows. The total number of piglets born per litter, the number of live-born piglets, the number of stillbirths, the number of assisted births, the number of piglets with meconium staining, and the number of piglets with umbilical cord rupture were also documented. Additionally, the incidence of postpartum diseases in sows was recorded.

Data were separately recorded for primiparous and multiparous sows, including litter birth weight, average birth weight per piglet, average number of piglets weaned per litter, average weaning weight per piglet at 21 d, average daily gain (ADG), and pre-weaning mortality rate.

$ \begin{gathered}\mathrm{ADG}=\sum_{ }^{ }\mathrm{\dfrac{Weaning\ litter\ weight\ -\ Birth\ litter\ weight}{Number\ of\ trial\ day}}\end{gathered} $ (1) $ \begin{split}&\text{Pre-weaning mortality rate}=\\ &\dfrac{\text{No. of piglets that died before weaning}}{\text{Total no. of live-Born piglets per litter}}\times100\text{%} \end{split}$ (2) Serum concentrations of cortisol and haptoglobin in sows, as well as lactate in piglets, were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The ELISA kit used was a product of Jiangsu Jingmei Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (JM-01237P1) (Jiangsu, China). The measurement indicators were strictly determined following the operating procedures outlined in the kit's manual. The coefficients of variation (CV) for the intra-batch precision of samples at different concentrations were all ≤ 10%, demonstrating the good linearity of the method.

Statistical analysis

-

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using SPSS 21.0 statistical software, and the graphs were created using GraphPad Prism 8. In the experiment, the incidence of postpartum diseases in sows and the estrus rate at 7 d post-weaning were analyzed using the χ2 test. Data such as the average farrowing interval, duration of farrowing, and time of final placenta expulsion were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan's multiple range test for post hoc comparisons. The results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation; p \lt 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

-

The injection sites of carazolol had effects on sows' reproductive performance. The intramuscular and vulvar injection groups had a significantly shorter average interval between piglets, farrowing duration, and time of expulsion of the final placenta (p \lt 0.05). There were no significant differences in total litter size, the stillbirth rate, the number of assisted deliveries, piglets with meconium staining and ruptured umbilical cords, and the number of live piglets among the three groups (p \gt 0.05). However, the gilt vulvar group had a slightly shorter farrowing duration than the other two groups (p \gt 0.05) (Table 1). These results indicates that using carazolol significantly reduces farrowing duration in primiparous sows.

Table 1. Effects of injection of carazolol at different sites on farrowing performance in primiparous sows

Index Primiparous control group Primiparous muscular group Primiparous vulvar group No. of test sows 32 33 34 Average litter spacing (min) 26.88 ± 11.08a 18.14 ± 5.80b 14.99 ± 3.95b Parturition stage of labor (min) 259.59 ± 114.25a 174.42 ± 58.56b 126.85 ± 39.92c Time of final discharge (min) 325.37 ± 109.11a 226.97 ± 68.18b 185.09 ± 52.74c Total piglets born (n) 12.34 ± 3.81 12.64 ± 2.99 12.62 ± 2.85 Piglets born alive (n) 10.75 ± 3.49 11.58 ± 2.69 11.97 ± 2.82 Intrapartum stillbirths (n) 0.59 ± 0.76 0.42 ± 0.61 0.35 ± 0.54 Piglets assisted at birth (n) 0.31 ± 0.59 0.21 ± 0.49 0.15 ± 0.36 Piglets infected with meconium (n) 0.34 ± 0.87 0.30 ± 0.53 0.29 ± 0.68 Piglets with ruptured umbilical cord (n) 0.44 ± 0.80 0.21 ± 0.48 0.17 ± 0.46 Values with different lowercase letters within columns were significantly different (p \lt 0.05). Values with the same letters within columns were statistically insignificant ( p >0.05). The same applies in the tables below. Effects of injecting carazolol injection at different sites on stress response in primiparous sows

-

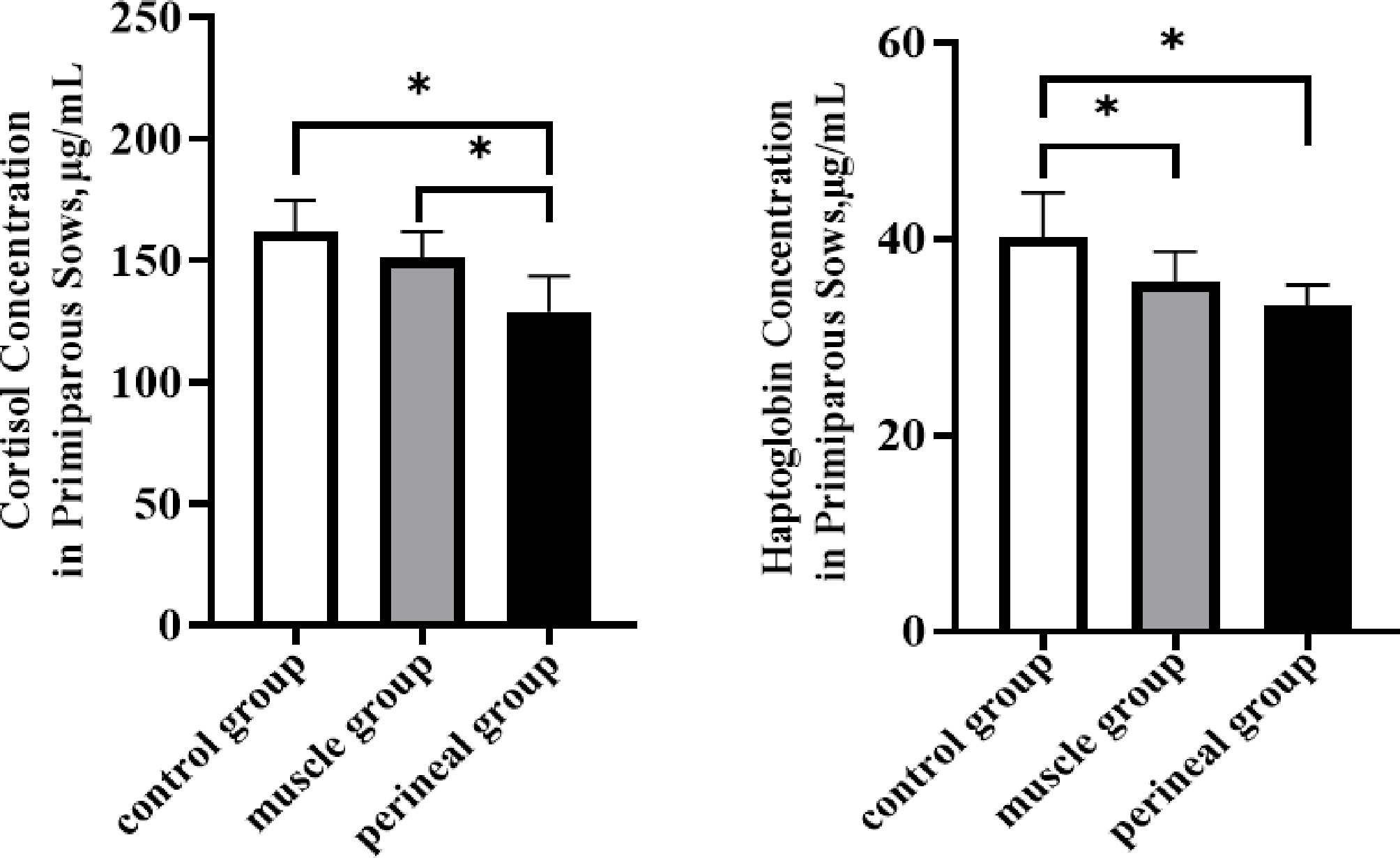

To investigate the effects of carazolol on farrowing stress in primiparous sows, the serum cortisol concentrations in sows injected with ccarazolol intramuscularly and at the vulva were significantly lower than in the control group (p \lt 0.05). Additionally, the haptoglobin concentrations were also significantly reduced (p \lt 0.05) in these groups (Fig. 1). Therefore, the marked reduction in sows' stress responses further validates that attenuated maternal stress is a mechanistic contributor to shortened farrowing duration.

Figure 1.

Effects of carazolol injection at different sites on the stress response in primiparous sows. Note: * indicates a significant difference (p \lt 0.05), while the absence of * indicates no significant difference (p \gt 0.05). The same applies in the figures below.

Effects of injecting carazolol at different sites on estrus induction in primiparous weaned sows within 7 d

-

To investigate the effects of carazolol injection at different sites on estrus, we collected data on the onset of estrus in gilts within 7 d after weaning. Compared with the control, the incidence of postpartum diseases in sows from the intramuscular and vulvar injection groups was significantly lower (p \lt 0.05). The estrus rate within 7 d post-weaning was significantly higher in both the intramuscular and vulvar injection groups (p \lt 0.05). Additionally, the interval from weaning to estrus was significantly shorter in the vulvar group compared with the control (p \lt 0.05) (Table 2). These results demonstrated that the reduction in puerperal diseases in primiparous sows significantly shortened their weaning-to-estrus interval.

Table 2. Effects of injecting carazolol injection at different sites on estrus induction within 7 d in weaned primiparous sows.

Index Primiparous control group Primiparous muscular group Primiparous vulvar group No. of test sows 32 33 34 Common postpartum diseases in sows (%) 25.00a (8/32) 12.12b (4/33) 8.82b (3/34) Estrus rate within 7 d post-weaning (%) 68.75c (22/32) 78.13b (25/32) 84.38a (27/32) Weaning to estrus interval (d) 5.27 ± 1.12a 4.88±0.93ab 4.63±0.84b Effects of injecting carazolol at different sites on farrowing performance in multiparous sows

-

There were no significant differences among the three groups in terms of the average interval between piglets, the duration of farrowing, and the time of expulsion of the final placenta in multiparous sows (p \gt 0.05). Additionally, there were no significant differences among the groups in the incidence of stillbirths, the number of assisted deliveries, the number of piglets stained with meconium, and the number of piglets with umbilical cord rupture (p \gt 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3. Effects of injection of carazolol at different sites on farrowing performance in multiparous sows.

Index Multiparous control group Multiparous muscular group Multiparous vulvar group No. of test sows 32 33 34 Average litter spacing (min) 22.00 ± 7.56 18.98 ± 7.01 18.49 ± 6.09 Parturition stage of labor (min) 266.03 ± 85.84 227.64 ± 101.02 223.97 ± 87.56 Time of final discharge (min) 330.59 ± 89.29 297.85 ± 102.03 287.47 ± 94.73 Total piglets born (n) 15.84 ± 3.20 15.82 ± 2.81 15.56 ± 3.01 Piglets born alive (n) 14.22 ± 2.94 14.21 ± 2.71 14.29 ± 2.91 Intrapartum stillborn (n) 0.78 ± 0.66 0.70 ± 0.77 0.85 ± 0.82 Piglets assisted at birth (n) 0.31 ± 0.64 0.18 ± 0.58 0.24 ± 0.65 Piglets infected with meconium (n) 0.41 ± 0.67 0.27 ± 0.45 0.32 ± 0.68 Piglets ruptured umbilical cord (n) 0.44 ± 0.67 0.33 ± 0.65 0.47 ± 0.79 Effects of injecting carazolol at different sites on estrus induction in multiparous weaned sows within 7 d

-

There were no significant differences in the incidence of postpartum diseases among the three groups in multiparous sows (p \gt 0.05). The estrus rate within 7 d post-weaning also showed no significant differences among the groups (p \gt 0.05), although there was an increasing trend in the intramuscular and vulvar groups. The interval from weaning to estrus did not differ significantly among the three groups (p \gt 0.05), but there was a trend toward a shorter interval in the intramuscular and vulvar groups (Table 4).

Table 4. Effects of injecting carazolol at different sites on estrus induction within 7 d in weaned multiparous sows.

Index Multiparous control group Multiparous muscular group Multiparous vulvar group No. of test sows 32 33 34 Common postpartum diseases in sows (%) 28.13 (9/32) 15.15 (5/33) 26.47 (9/34) Estrus rate within 7 d post-weaning (%) 68.75 (22/32) 75.76 (28/33) 69.70 (23/33) Weaning to estrus interval (d) 4.73 ± 0.94 4.29 ± 0.60 4.43 ± 0.90 Effects of injecting carazolol at different sites on lactic acid and growth performance of weaned piglets

-

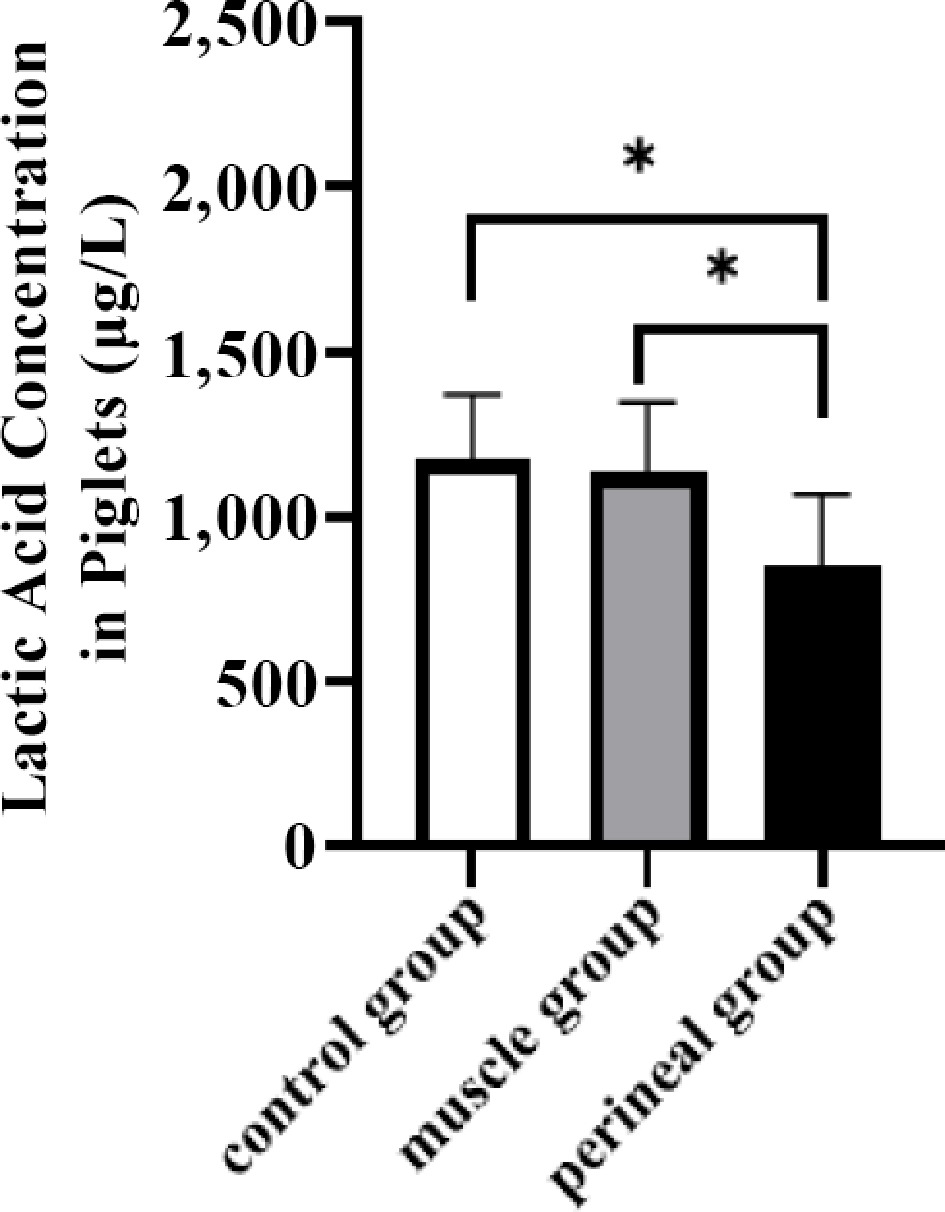

To further evaluate the effects of carazolol injection sites on piglet asphyxia, the lactic acid concentration in piglets from primiparous sows was measured. No significant differences in the lactic acid concentrations of piglets were found between the intramuscular and vulvar injection groups (p \gt 0.05). However, a downward trend in lactic acid concentrations were found in the piglets from both the intramuscular and vulvar groups (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effects of injecting carazolol at different sites on lactic acid concentration in piglets from primiparous sows.

Effects of injecting carazolol at different sites on the growth performance of weaned piglets

-

Regarding the effects of carazolol on the piglets' growth performance of primiparous sows, no significant differences among the three groups were found in terms of total litter size, number of live-born piglets per litter, birth litter weight, and average individual birth weight (p \gt 0.05). Similarly, no significant differences were found among the groups in number of piglets weaned per litter, weaning litter weight, average individual weaning weight at 21 d, and average daily gain (p \gt 0.05), although there was an increasing trend observed in the vulvar injection group (Table 5).

Table 5. Effects of injecting carazolol at different sites on the growth performance of piglets from primiparous sows.

Index Primiparous control group Primiparous muscular group Primiparous vulvar group Litter number 11 10 11 Total piglets born (n) 13.82 ± 0.98 13.50 ± 1.43 14.00 ± 1.18 Piglets born alive (n) 12.27 ± 1.90 12.40 ± 0.97 12.45 ± 1.63 Litter birth weight of piglets (kg) 18.36 ± 3.83 19.44 ± 3.39 17.64 ± 4.36 Average birth weight of piglets (kg) 1.50 ± 0.23 1.58 ± 0.34 1.41 ± 0.28 Weaning litter size at 21 d (n) 9.90 ± 1.22 10.00 ± 1.15 10.45 ± 1.81 Weaning litter weight (kg) 59.54 ± 6.11 60.26 ± 6.38 62.74 ± 9.32 Average weaning weigh (kg) 6.03 ± 0.31 6.05 ± 0.46 6.07 ± 0.71 Average daily weight gain of piglets (g/d) 215.69 ± 21.15 212.64 ± 31.08 222.07 ± 38.13 Pre-weaning mortality rate of piglets (%) 19.26 (26/135) 15.32 (19/124) 16.06 (22/137) -

As the demand for increased litter size and piglet survival rates, more precise control of the farrowing time becomes increasingly critical[23]. Shortening the duration of farrowing can reduce the perinatal piglet mortality rate[24]. Studies have shown that the duration of farrowing is positively correlated with the incidence of stillbirths and perinatal piglet mortality[25]. In the present study, we firstly selected optimal parity sows for carazolol treatment and found that it significantly shortened the duration of labor in primiparous sows and improved estrus performance 7 d after weaning. Carazolol can promote oxytocin release and inhibit pain and excitation responses in sows during parturition caused by endogenous adrenaline, thereby reducing the sow's stress response and shortening the duration of labor[26].

In present study, vulvar injection of carazolol in gilts significantly shortened the average inter-piglet delivery interval, the duration of labor, and the time for placenta expulsion. Meanwhile, there was a tendency for a decrease in the number of assisted deliveries, piglets with meconium-stained feces, and piglets with ruptured umbilical cords. Previous research has shown that intramuscular injection of carazolol significantly shortens the duration of labor in gilts. The reason may be that the sow's reproductive tract is closely connected to the lymphatic and venous vessels, and the absence of a pulmonary first-pass effect with vulvar injection allows for higher drug concentrations. This method, compared with intramuscular injection in the neck, more rapidly exerts an anti-stress effect. A possible reason is that the lymphatic vessels in the sow's reproductive tract are closely connected to the venous blood vessels. The vulvar injection method avoids the first-pass effect through the lungs, allowing the local concentration to reach a very high level[27].

The sows receiving vulvar injection showed a decreasing trend in the average litter interval, duration of labor, and time for expulsion of the placenta (Table 2). However, the number of stillbirths was relatively higher in this group. As the number of farrowings and the age of the sows increase, their physical functions gradually decline, and postpartum reproductive performance is difficult to recover to optimal state. Moreover, the muscular function of the sows also deteriorates over time, which is manifested by a significant reduction in abdominal pressure and uterine muscle contraction strength, ultimately leading to prolonged labor[28,29]. Prolonged labor can cause the fetus to remain in the uterus for an extended period, increasing the risk of conditions of hypoxia, which, in turn, raises the incidence of stillbirths in piglets[8,30,31].

In our study, postpartum diseases in gilts and the weaning-to-estrus interval were significantly reduced by 16.18% and 0.64 d, respectively. As a result of the increase in litter size and the duration of labor, the incidence of postpartum diseases may rise to 34%[32]. When labor increases from 2 to 4 h, the probability of fever within the first 24 h postpartum increases from 40% to 100%[33]. Previous studies have shown that prolonged labor can affect the expulsion of the placenta in sows, while prolonged cervical dilation significantly increases the risk of endometritis[31]. Another study indicates that prolonged labor and postpartum diseases are associated with reduced estrus performance in sows after weaning[34]. The estrus rate on Day 7 after weaning increased significantly by 15.63%. The effect was not obvious in older sows because parturition can induce central nervous system changes in multiparous sows, increasing their sensitivity to postpartum pain. Additionally, the loss of uterine muscle tone in multiparous sows prolongs the duration of labor, ultimately leading to poor estrus performance in sows after weaning[35].

Cortisol is one of the most widely used biomarkers for detecting stress in pigs and is the primary glucocorticoid in this species. Haptoglobin, an acute-phase protein, serves as a tool for detecting acute inflammation in pigs and is an important indicator of stress in farrowing sows[36,37,38]. The process of labor and lactation is very physically demanding for sows, leading to increased energy requirements. This increase in energy demand helps explain the rise in blood cortisol levels, particularly when considering the feeding restrictions faced by sows[39]. Tantasuparuk et al. found that elevated cortisol levels in sows decreased litter size, the farrowing rate, and the weaning-to-first service interval[40]. However, in present study, it was found that the serum cortisol and haptoglobin concentrations were significantly reduced in the primiparous vulvar injection group, which may, in turn, reduce the incidence of postpartum diseases. Elevated cortisol and haptoglobin levels antagonize the effects of oxytocin, leading to prolonged labor in farrowing sows and increasing the risk of stillbirths and postpartum diseases[41,42]. These results suggest that carazolol can inhibit excessive cortisol secretion and haptoglobin during farrowing, reducing the dystocia in sows caused by stress.

During labor, hypoxia may be caused by umbilical cord rupture, leading to acute hypoxia and sudden death[43]. Even brief episodes of hypoxia can cause permanent damage to the central nervous system of piglets, which may disrupt their normal suckling instincts, reduce colostrum intake, and impair growth performance[44,45]. In this experiment, it was found that carazolol had effects on primiparous sows' delivery. A decreasing trend in pre-weaning piglet mortality was observed, with no negative impact on the piglets, which is consistent with previous studies[46]. Muns et al.[47] reported that the total number of piglets born per litter in sows was 19.0, with an average farrowing duration of 580 minutes. However, prolonged farrowing not only harms the health of the sow but also significantly increases the risk of piglet asphyxiation caused by oxygen deprivation during delivery. Currently, elevated lactate concentrations in piglet umbilical cord blood are an important indicator of hypoxia during farrowing[48]. In primiparous sows, lactate concentrations were measured in piglets' umbilical cord blood. The results showed a decreasing trend in lactate levels for the muscular and vulva rinjection groups; however, the effect was not statistically significant. Therefore, carazolol has a minimal impact on blood flow during uterine contractions in sows, thereby reducing the risk of piglet mortality.

-

In conclusion, the results in present study indicate that administering a vulvar injection of carazolol to primiparous sows after the birth of the first piglet effectively shortens the duration of farrowing, reduces the stress response, and accelerates postpartum recovery.

-

All procedures were reviewed and preapproved by the ethical review committee or equivalent, which approved the use of animals (identification number: 2025145, approval date: 2025.6.9). The research followed the "replacement, reduction, and refinement" principles to minimize harm to animals. This article provides details on the housing conditions, care, and pain management used for the animals, ensuring that the impact on the animals was minimized during the experiment.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: data curation, writing – original draft: Yao C; validation: Tian X; writing – review & editing: Tian X, Xia W, Zhao S, Qi Y, Tao C, Li J; software: Tao C; conceptualization, funding acquisition: Li J; methodology: Qin T, Yao C, Li J; investigation: Tian X, Tao C. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data supporting our findings are included in the manuscript. The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories: NCBI SRA (BioProject lD. PRJNA1215573).

-

This work was supported by grants from the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD1300303), and Hebei Agriculture Research System (HBCT2024220202).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Congcong Yao, Wei Xia

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yao C, Xia W, Tian X, Qin T, Zhao S, et al. 2026. Effect of carazolol on parturition performance of sows and piglet growth during the peripartum period. Animal Advances 3: e005 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0044

Effect of carazolol on parturition performance of sows and piglet growth during the peripartum period

- Received: 08 June 2025

- Accepted: 01 September 2025

- Published online: 30 January 2026

Abstract: Perinatal intervention for sows holds immense significance in maintaining sows' health and ensuring optimal reproductive performance. However, because of the influence of various factors, during parturition, sows often suffer stress, affecting both the sows and the piglets. Carazolol is an adrenergic receptor blocker, but little research has reported on the effects of its administration at different injection sites on sows' farrowing performance and piglet growth. Therefore, this study investigated the effects of carazolol administration at different injection sites on both sows' farrowing performance and piglets' growth characteristics. The results indicated that, in comparison with the gilts, both the sow muscular injection group and the primiparous vulvar injection group exhibited significantly shorter average intervals between piglet births, shorter farrowing durations, quicker expulsion of the final placenta, and a shorter weaning-to-estrus interval (p \lt 0.05). The incidence of postpartum diseases was notably decreased (p \lt 0.05). The estrus rate within 7 d post-weaning was significantly elevated in both the muscular and vulvar injection group (p \lt 0.05). Furthermore, the serum cortisol and haptoglobin concentrations in sows, as well as the lactic acid concentrations in the umbilical cord blood of piglets, were notably lower in both the muscular and the vulvar injection groups (p \lt 0.05). Among multiparous sows, the vulvar injection group exhibited a tendency for shorter average intervals between piglet births, a decreased farrowing duration, and faster expulsion of the final placenta. In conclusion, injecting 0.02 mL/kg of carazolol after birth in gilts can effectively improve farrowing performance. Compared with injections in the muscle, injections in the vulva demonstrated a more significant effect.

-

Key words:

- Peripartum period /

- Sows /

- Carazolol /

- Parturition /

- Piglet growth performance