-

Heavy metal pollution has escalated into a worldwide crisis, with agricultural soils serving as the frontline[1]. Though some heavy metals are essential elements for the human body under low concentrations, such as Cu and Zn[2]. Most heavy metals, including chromium (Cr), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and arsenic (As), can cause irreversible harm to human health via the food chain. For instance, long-term exposure to Pb and As can result in cumulative damage to the brain and kidneys[3]. Moreover, Cd is related to osteoporosis, blood pressure disorders, and cancer[4]. Once released, these heavy metals migrate continuously through multiple pathways, exerting severe negative effects on the hydrosphere, atmosphere, and pedosphere. Agricultural soils contaminated by heavy metals may rapidly lose their ability to sustain safe food production[5].

Soil provides the fundamental conditions and essential substances, which human beings, plants, and animals depend on for their survival. With the exponential growth of the global economy and population, there is an increasing demand for advanced agricultural production, which encompasses both sufficient crop yield and benign crop quality, to ensure balanced society development[6]. However, heavy metals pollution has emerged in agricultural soils via pathways such as the application of organic manure, irrigation with industrial wastewater containing excessive heavy metals, and other activities, ultimately resulting in a significant degradation of both agricultural product quality, and cultivated soil fertility[7]. Therefore, effective measures for the remediation of soil contaminated by heavy metals are urgently required.

Various methods for the remediation of heavy metals, such as chemical stabilization[8], thermal treatment[9], electrokinetic remediation[10], and adsorption[11], have been developed by previous studies to address the aforementioned challenges. Among these technologies, adsorption stands out for its operational simplicity, wide practicability, cost-effectiveness, and minimal secondary disturbance to the soil environment, making it a suitable and promising strategy for the remediation of agricultural soils[12]. Over the decades, diverse adsorbents have been employed in the remediation of heavy metal-polluted farmland soils, such as chitosan-based composites, clay minerals, and biochar (BC)[13]. Among them, BC, an adsorbent that has attracted widespread attention due to its high specific surface area (SSA), porous structure, and low expense, is considered a more favorable material for the in-situ passivation process of heavy metals[14]. Meanwhile, systematic investigations have revealed the abundant biomass sources for BC, primarily including agricultural residues such as pomegranate peel[15], rice husk[16], bagasse[17], etc, thereby offering outstanding economic and environmental benefits[18]. The adsorption performance on heavy metals and the corresponding treatment parameters of BC derived from various resources are summarized in Table 1. However, due to the undiscriminating adsorption behaviour and mediocre chemicophysical characteristics of BC, the direct employment of pristine BC in the process of heavy metals passivation exhibits unsatisfactory outcomes, resulting in an insufficient practical value in terms of in-situ heavy metal remediation of cultivated soils[30].

Table 1. Summary of removal mechanisms for BC-based adsorbents and various feedstocks

BC/material Pyrolysis parameters Heavy

metalsMaximum adsorption

capacity (mg/g)Kinetic model Isotherm Removal mechanism Ref. Hickory wood 600 °C Pb(II) 153.1 Richie Langmuir Surface adsorption [19] Cu(II) 34.2 Elovich Langmuir Cd(II) 28.1 Richie Langmuir Coconut shells 800 W microwave Pb(II) 4.77 Pseudo-second-order (PSO) Langmuir Surface adsorption and Van der Waals forces [20] Cd(II) 4.96 PSO Langmuir Oleifera shells 550 °C Pb(II) 52.9 PSO Langmuir Chemisorption [21] Waste-art-paper 600 °C Pb(II) 1,555 PSO Langmuir Precipitation [22] Corn straw 500 + 800 °C Cr(VI) 116.97 Avrami fractional-order (AFO) Langmuir Electrostatic attraction, complexation, ion exchange and reduction action [23] Douglas fir 900–1,000 °C Pb(II) 140 PSO Langmuir Chelation, electrostatic-attraction, and ion exchange [24] Cr(VI) 127.2 PSO Langmuir Cd(II) 29 PSO Langmuir Rice husks 450 °C Cr(VI) 195.24 PSO Langmuir Ion exchange [25] Tea waste 450 °C Cr(VI) 197.5 PSO Langmuir Nitrogenous bone 600 °C Pb(II) 558.88 PSO Langmuir Surface complexation, cation exchange, chemical precipitation, electrostatic interaction and cation-π bonding [26] Cu(II) 287.58 PSO Langmuir Cd(II) 165.77 PSO Langmuir Water hyacinths 700 °C Cd(II) 35.1 Pseudo-first-order (PFO) Langmuir Precipitation [27] nZVI-BC 600 °C Cu(II) 31.53 PSO Langmuir Precipitation [28] Swine manure, sawdust 400 °C Pb(II) 268 PSO Langmuir Electrostatic attraction and ion exchange [29] Therefore, to further enhance the selectivity and efficacy of pristine BC, which refers to BC without modification, various modification approaches have been developed, including chemical activation[31], surface grafting[32], and heteroatom doping[33]. Among these modified BCs, element-doped BC (EDBC) emerges as an exceptional material for heavy metal passivation due to the increase in additional adsorption sites. Heteroatom doping can modulate the electron charge density and enhance the dispersion of EDBCs[34]. Moreover, different functional groups (FGs) are introduced to either directly or indirectly improve the passivation performance of EDBCs on specific heavy metals while maintaining the original surface defect structure of this material[35]. For instance, nitrogen doping introduces nitrogen-containing FGs, such as pyridinic N, pyrrolic N, and graphitic N. These groups can serve as active centers for the adsorption of heavy metals through complexation reactions. The lone pair electrons in the nitrogen atoms can bind with metal ions, increasing the adsorption capacity[36,37]. Thus, wide attention has been drawn to EDBCs. However, to date, few reviews have elucidated EDBCs and the underlying mechanisms for heavy metals remediation in farmland soils.

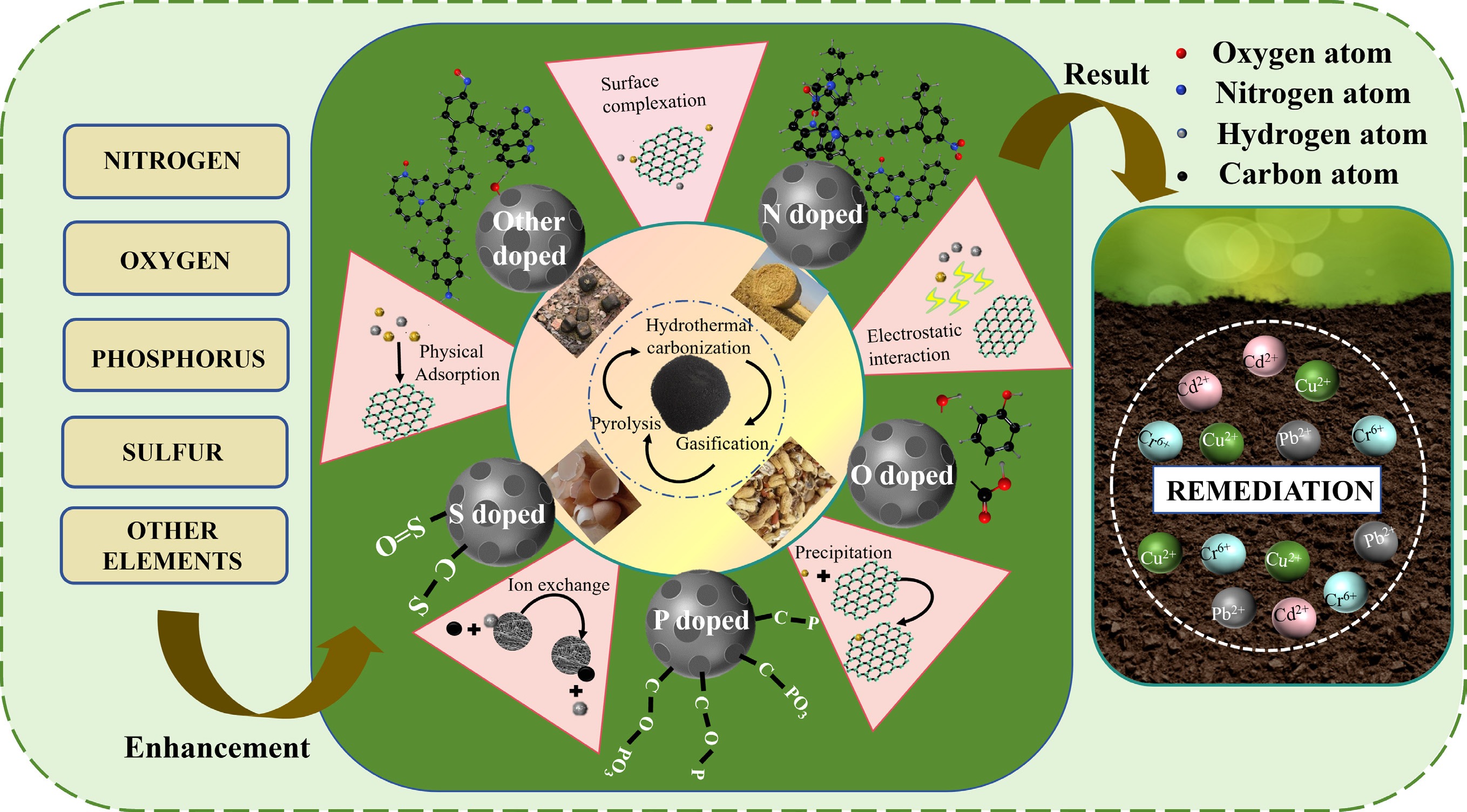

Herein, this article is systematically organized into the following sections: (i) Various methods for the preparation of pristine BC; (ii) Adsorption mechanisms of heavy metal ions by pristine BC; (iii) Modification approaches of the doping of different elements (mainly N, O, S, and P) to enhance adsorption properties, along with the corresponding mechanisms for the heavy metals passivation; (iv) Roles and effects of different FGs on the passivation of heavy metal ions on modified BC; (v) Different application strategies of EDBCs for farmland soils, and the future prospects of EDBCs development are also discussed.

-

Pyrolysis refers to the decomposition process of biomass by heating under oxygen-limited conditions, thereby converting raw materials into bio-oil, gases, and BC. As the predominant preparation method of BC, there are many pyrolysis-derived technologies are developed in recent applications, including catalytic co-pyrolysis, negative pressure pyrolysis, etc.[38]. For example, microwave-assisted pyrolysis is a rather convenient and high-yielding method compared with sole pyrolysis, which greatly decreases the energy expense[39]. Meanwhile, biomass composition has an effect on BC yield. For example, a higher concentration of cellulose, lignin, and ash content in feedstock is positively correlated with enhanced BC yield. Moreover, existing evidence suggests that through controlled pyrolysis temperature, BC with tailored surface area, total pore volume, and high mass fraction of carbon could be achieved[40]. The properties of BC are also distinctly influenced by the duration of pyrolysis. It has been reported that prolonged pyrolysis duration could produce BC with reduced detrimental substances[41].

Gasification

-

Gasification refers to a thermochemical process in which biomass is oxidized to produce BC, syngas, and biomass extracts under oxygen-deficient conditions at elevated temperatures (higher than 500 °C)[42]. Same as the pyrolysis technique, its products are prone to being affected by reaction conditions. For example, the SSA and porosity of BC prepared by gasification under high temperature and pressure are more superior to those of conventional synthesis[43]. Previously, BC was considered a byproduct with intentionally limited yield to ensure the high conversion rate of carbon monoxide[44]. Recently, the advantage of gasification, its high BC production efficiency, has garnered significant research attention. Moreover, gasification could achieve a continuous feedstock treatment, providing higher throughput than other techniques[45].

Hydrothermal carbonization

-

Hydrothermal carbonization is a moderate method that realizes the conversion and carbonization of feedstock at a relatively low temperature (150–300 °C), and ordinary pressure[46]. Hydrothermal carbonization is carried out at relatively low temperatures (180–260 °C) under autogenous pressure in an aqueous environment. This allows direct use of high-moisture organic residues—green algae, kitchen waste, and other water-rich solid wastes—thereby eliminating the energy otherwise required for predrying[47]. Moreover, the hydrochar could be customized by a simple adjustment in synthesis parameters, including solution medium, reacting temperature, heating time, etc., hence minimizing the economic expense of negative emission treatment of waste[48].

Adsorption mechanisms of heavy metals on pristine BC

Physical adsorption

-

Physical adsorption refers to the weak reaction in which contaminants diffuse into the surface holes of the adsorbent and deposit on its surface to remove heavy metals without forming chemical bonds. The increase in the number of micropores on BC can significantly enlarge SSA, thus facilitating the physical adsorption process[49]. Moreover, the pore structure of BC is significantly influenced by the sources of materials and synthetic parameters. For example, under the same pyrolysis temperature, the SSA and pore size of orange bagasse-derived BC (SSA = 99.1 m2/g, PS = 6.75 nm) were significantly higher than those of BC derived from coconut husks (SSA = 77.2 m2/g, PS = 3.91 nm), and pine woodchips (SSA = 72.2 m2/g, PS = 4.15 nm). The adsorption capacity of hydrochar is twice that of BC prepared by ordinary pyrolysis[50].

Electrostatic interaction

-

Electrostatic attraction is the mutual interactive force caused by the difference in charge distribution between adsorbents and heavy metals, acting as a secondary driving force for the adsorption of heavy metals[51]. The zero charge point of BC and the solution pH are the main factors determining the electrostatic interaction performance. BC carries negative charges when the solution pH exceeds BC zero charge point, positively charged when the pH is below that point[52]. On the other hand, when H+ concentration is high, protonation reaction occurs on the surface of BC, specifically through the ionization of hydroxyl (-OH) and carboxyl (-COOH) groups, resulting in a positive charge on its surface. For example, when the environment pH was 2, BC's adsorption capacity for negatively charged Cr ions through electrostatic attraction soared to 123 mg/g[53].

Ion exchange

-

Another common mechanism is the adsorption of heavy metals by the ion exchange between protons/cations, and metal ions on BC[54]. The alkali metal ions and FGs on BC are essential components in ion exchange[55]. Through ion exchange, BC effectively adsorbs and immobilizes heavy metal ions in soil. Many analyses have been conducted to quantify the contribution of ion exchange. For instance, employing BC as the remediation agent, the predominant mechanism for Cd passivation in soil was identified to be ion exchange (44.65%) under a pH range of 3–7[56].

Surface complexation

-

Various complexes could be formed via interactions between electron donors and electron accepters. In terms of heavy metals, their interactions with ligands leads to the appearance of an organic complex structure, resulting in heterogeneous adsorption[57]. The -COOH and -OH groups on BC surface can effectively bind heavy metals. For instance, these groups serve as complexing agents for Cu ions, affecting the passivation performance of BC[58]. Similarly, Lu et al.[59] demonstrated that Pb ions, which were passivated by -COOH and -OH groups, accounted for 38.2%–42.3% of the total Pb amount, showing their negligible role. In addition to -COOH and -OH, other functional groups such as -NH2, -PO3H2, -SO3H, and quinone-like structures (-O-O-C=O) can also participate in surface complexation. -NH2 groups can form coordination bonds with heavy metals through their lone pair electrons. -PO3H2 and -SO3H groups contribute to adsorption via electrostatic attraction and ligand exchange mechanisms. Quinone-like structures can undergo redox reactions with certain heavy metals, further enhancing the adsorption capacity of BC[60]. These diverse functional groups collectively contribute to the efficient immobilization of heavy metals by EDBC.

Precipitation

-

Precipitation refers to the formation of solid products (either within the solid matrix or liquid phase) during pollutant adsorption, a process that often operates synergistically with other removal mechanisms. The content of ash elements in feedstocks positively relates to the passivation performance of BC. Meanwhile, it was observed that with a minor diameter of BC particles, there would be an interference of the precipitation compared with a larger counterpart, due to its higher heterogeneous formation energy (21.90 mJ/m2)[61]. Besides, the FGs on the BC surface can influence other adsorption mechanisms to accelerate the precipitation. For example, in BC adsorption of Cu ions and Cd ions, two new peaks were found by analyzing the differences between the XRD results of fore-reaction and after-reaction BC. The newly formed peaks confirmed the complexation of heavy metals with FGs on BC surface, which ultimately facilitates the precipitation process[62].

-

The passivation performance of pristine BC on heavy metals is insufficient, so element doping of it is required. A variety of methods have been frequently applied, introducing different surface FGs on BC to increase the passivation capacity toward different heavy metals, mainly involving nitrogen-, oxygen-, sulfur-, and phosphorus-doping[63]. However, few studies have conclusively identified an effective doping element for BC in agricultural soil remediation. Herein, a systematic summary of how element-doped BC synthesize and the reactivity of various elements toward contaminants in farmland soils is conducted.

Nitrogen-doped BC

-

Nitrogen (N) doping serves as an efficacious approach to enhance the performance of BC. One of the advantages of N-doping is that additional active sites on the BC surface could be created with N atom addition, enhancing the hydrophilicity to facilitate complexation reaction. Simultaneously, elevated basicity of BC surfaces enhances electrostatic interactions[64], thereby boosting the passivation of heavy metals in farmland soils.

The preparation of N-doped BC typically involves the doping with an external N-precursor, which is utilized to form N-containing FGs onto the surface of BC. Thermal treatment processes often involve the addition of exogenous reagents to introduce N at varying temperatures[65], as the preparation of BC typically relies on N-containing precursors. For example, the N-doped graphite-like BC showed that the BC surface was uniformly distributed with N atoms and abundant nitrogenous species (e.g., pyrrolic N and graphitic N). In particular, the total N content, which was measured at 17.7%, was nearly ten times as much as that of the pristine BC[66]. By substituting carbon atoms within the graphitic lattice, nitrogen creates lattice defects and curvature that open up additional slit pores, raising the specific surface area by up to 35% while generating a hierarchical micro-/meso-pore network beneficial for rapid heavy-metal diffusion[67].

The FGs adhered to the surface of BC are common exogenous N, such as aminated groups[64]. Aminated groups serve as preferential adsorption sites in contact with BC due to their electron-rich feature, facilitating the removal of pollutants through the protonation process and complexation reactivity. For example, the amidogen (-NH2) on the surface of BC greatly improves the adsorption effect through complexation with heavy metals (e.g., Cd2+)[68]. Besides, oxynitride introduced on BC can generate aminated groups through a series of acquired electron processes, which is conclusive to improve heavy metal adsorption capacity[69].

In addition to aminated groups and oxynitrides which possess fundamental FG characteristics of doped N, the substitution of carbon atoms from the edges of ordered carbon units by doped N atoms are energetically preferable in the atomic scale[70], including pyridinic N, pyrrolic N, and graphitic N. Remarkably, N atoms were of great significance in promoting the redox process of heavy metals to diminish toxicity through complexation reactions between FGs and contaminants[71]. Moreover, the lone pair electrons in the graphite N atom were able to supply extra adsorption sites for the complexation between pollutants and BC, enhancing the hydrophilicity of BC to promote the contact between the adsorbent and heavy metals.

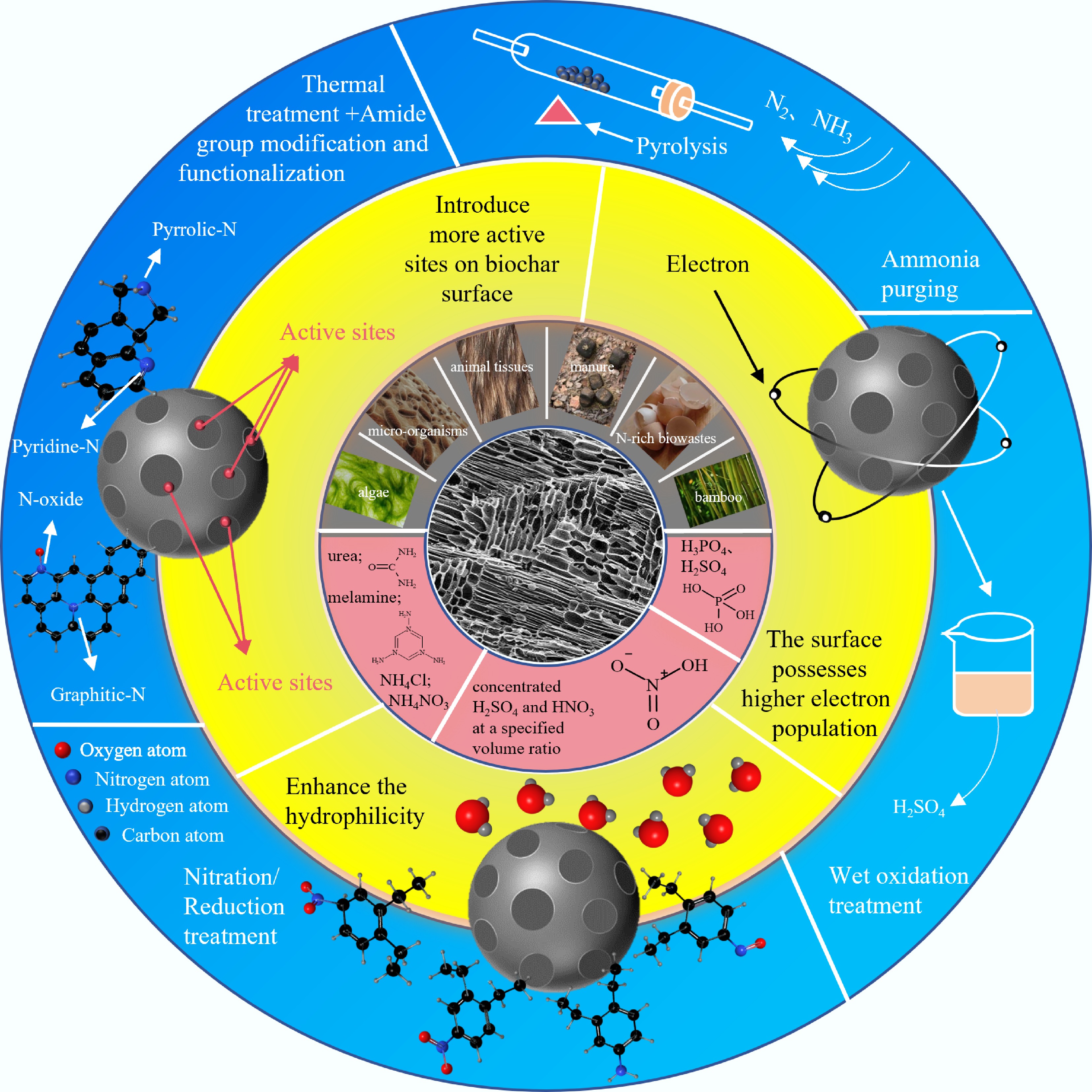

In summary, numerous studies suggested that N-doping BC with external modification showed high passivation efficiency to heavy metals through introducing N-containing groups or providing and activating new reaction sites. The N introduction of BC for heavy metal passivation was summarized into three points: (1) The incorporation of typical base sites can readily supply lone pair electrons, enabling the adsorption of a greater number of metal cations on BC via electrostatic attraction; (2) N-doping enhances surface hydrophilicity, promoting the coordination of graphite N with heavy metals; (3) The surface possesses higher electron population, exhibiting favorable affinity towards heavy metals. To better exhibit the significance of N-doping for heavy metals passivation, frontier studies from recent years were collected, and the passivation classifications of heavy metals as well as the adsorption properties of different N-doped BC are listed in Table 2. Meanwhile, preparation of biomass, synthesis technology, and performance regulation toward nitrogen doped-BC are also summarized in Fig. 1.

Table 2. BC adsorbents doped with N for heavy metal removal

BC Preparation technology Contaminant Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g)—Langmuir Adsorption mechanism Ref. Oleifera shells Ammonium polyphosphate pretreatment, high temperature carbonization Pb(II) 723.6 Chemisorption [21] Coffee shells (NH4)3PO4 pretreatment, in-situ doping Cr(VI) 235.5 Adsorption/reduction [72] Rice straw Nitrification and nitro reduction method Cd(II) 84.266 Complexation [68] Lignocellulosic biomass Nitrification and nitro reduction method Cu(II) 17.12 Complexation, onexchange, chelation, and microprecipitation [69] Wood dust HNO3 pretreatment, autoclave heating Cr(VI) 107.2939 Ion exchange, electrostatic effect [73] Sb(V) 167.2042 N-enriching hydrophyte biomass Biomass of N-rich aquatic plants loaded with MgCl2 by rapid pyrolysis, endogenous doping Pb(II) 893 Ion-exchange, surface adsorption [74] Shrimp shells Microwave-assisted self-modification of nitrogen doped oxygen graphene hydrogels Cr(VI) 360.05 Electrostatic adsorption (ion-pair), pore filling, reduction and coordination. [75]

Figure 1.

Preparation of BC, synthesis technology, and performance regulation toward nitrogen-doped BC.

Oxygen-doped BC

-

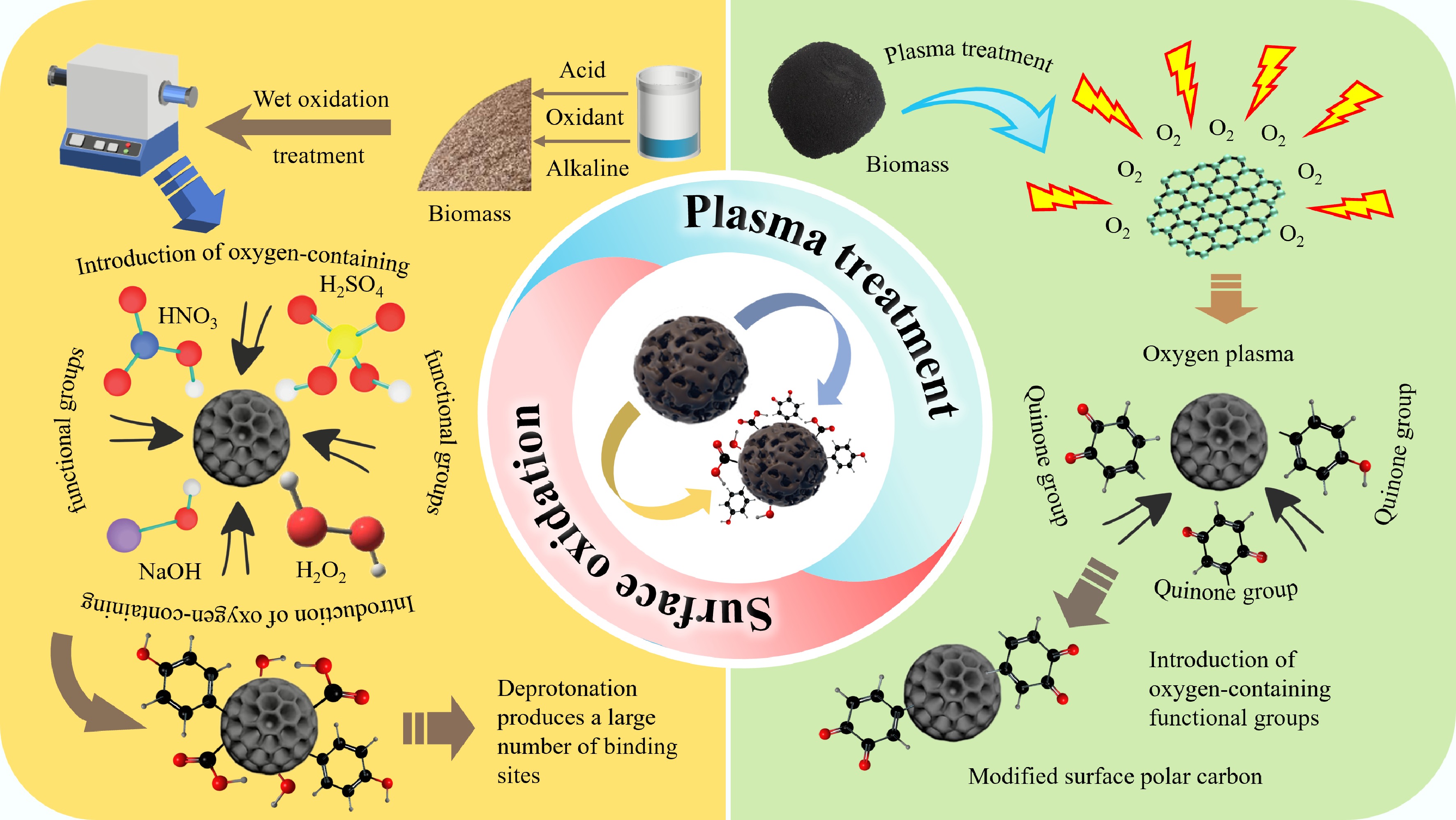

The main purpose of oxygen (O) doping for BC is to introduce various O-containing FGs, which have substantial impacts on surface reaction, hydrophilicity, and electricity of BC[76]. Specifically, O doping can affect the electron transfer and significantly increase active sites through deprotonation, thus effectively enhancing the passivation performance for heavy metals. The carboxyl and hydroxyl groups are commonly considered to be the main groups promoting the surface coordination between heavy metals and adsorbents[77]. Therefore, O doping serves as an effective method to alleviate the remediation performance of BC in farmland.

Surface oxidation and plasma treatment are the main methods of O doping[39]. In general, surface oxidation represents the most prevalent and straightforward method for creating abundant O-containing FGs. This involves the utilization of oxidants to augment the quantity of O-containing FGs present on the BC surface. Common oxidants include acid (e.g., HNO3 and H3PO4)[78], alkali (e.g., NaOH and KOH)[79], or some oxidant reagents (e.g., H2O2 and KMnO4)[80].

Acid modification can effectively introduce FGs into BC, such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups. Moreover, the concentration of modifying agent and temperature of BC preparation have a profound impact on the modification effect[81,82]. Besides, H2SO4 treatment could oxidize aromatic ring side chains in BC, thus introducing a substantial quantity of acidic FGs (mainly -COOH group). Instead, different H2SO4 treatments showed distinct oxidation effects, and the oxidation effect reached its maximum when the H2SO4 concentration was 97%[83]. Moreover, BC modified with HNO3 exhibited excellent adsorption performance toward Cr(VI), which is 9.72% higher than those without modification[81]. This acid modification method could effectively improve the surface FGs of BC. However, it should be noted that BC is relatively difficult to oxidize by acid at higher temperatures. In addition to the above acidic oxidation, alkaline oxidation is also a conventional method for O doping to remove heavy metals. BC modified with NaOH and H2O2 resulted in the SSA of the BC increased by 126% compared with the pristine BC, and O-containing FGs played an important role in removing Cd(II) through complexation[82]. Moreover, alkali-modified BC can enhance the adsorption capacity of BC for removing heavy metals with its activated surface, which rose the SSA from 256 to 873 m2/g[84].

Equally, O plasma treatment is another excellent method to introduce O-containing FGs, by which O-containing FGs are appended to the BC surface with the internal structure remaining intact. Moreover, the O-containing FGs (e.g. carbonyl, hydroxyl, and carboxyl) increased greatly with the process of plasma treatment, which oxidized Hg0 to HgO and improved the removal rate of Hg[85]. Surface-bonded oxygen, mainly as ether and carbonyl groups, thermally cleaves at 400–600 °C and releases CO/CO2, leaving behind a high density of ultra-micropores (< 1 nm) that enlarge the SSA and sharpen the pore-size distribution without collapsing the carbon skeleton[86].

Overall, O-doping technology can introduce a large quantity of O-containing FGs onto BC, while simultaneously enhancing both the SSA and pore structures of BC to adsorb heavy metals effectively. Importantly, -COOH and -OH groups have a vital effect on passivating heavy metals, which generate negative charges through deprotonation and adsorb heavy metals through electrostatic attraction. To better explain the significance of O-doped BC for passivating heavy metals, frontier studies in the past few years had been collected and were listed to illustrate the passivation properties of different O-doped BC toward heavy metals in Table 3. Meanwhile, a graphic summary outlining the preparation process is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 3. BC adsorbents doped with O for heavy metal removal

BC Preparation technology Contaminant Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g)—Langmuir Adsorption mechanism Ref. Dried hickory chips Heating with NaOH solution, alkali modification Pb(II) 19.1 Chemisorption [84] Cu(II) 17.9 Cd(II) 0.98 Corn straw Soaking in water and HNO3 activation, wet chemical oxidation Cr(VI) 36.365 Adsorption/reduction [87] Rice straw Modification of biochar with equal volume mixture of H2O2 and HNO3, wet chemical oxidation Cd(II) 117.975 Electrostatic attraction, chemisorption [88] Rice straw KMnO4 reacts with pyrolytic biochar to form MnO coating, wet chemical oxidation Pb(II) 305.25 Chemical adsorption, complexation, precipitation, ion interaction [89] Corn straw In-situ doping, acid ammonium persulfate oxidation method Cu(II) 151.67 Surface complexation, chemical reduction [90] Camellia seed husks Soaking in HCl, wet chemical oxidation, endogenous doping Pb(II) 141.86 Electrostatic attraction, sedimentation, coordination [91] Cd(II) 54.3 Pecan nut shells (Caryaillinoinensis) Irradiation heating in H2O steam atmosphere Pb(II) 129.86 Complexation, strong interaction, ion interaction [92] Cu(II) 57.83 Cd(II) 21.69 Sulfur-doped BC

-

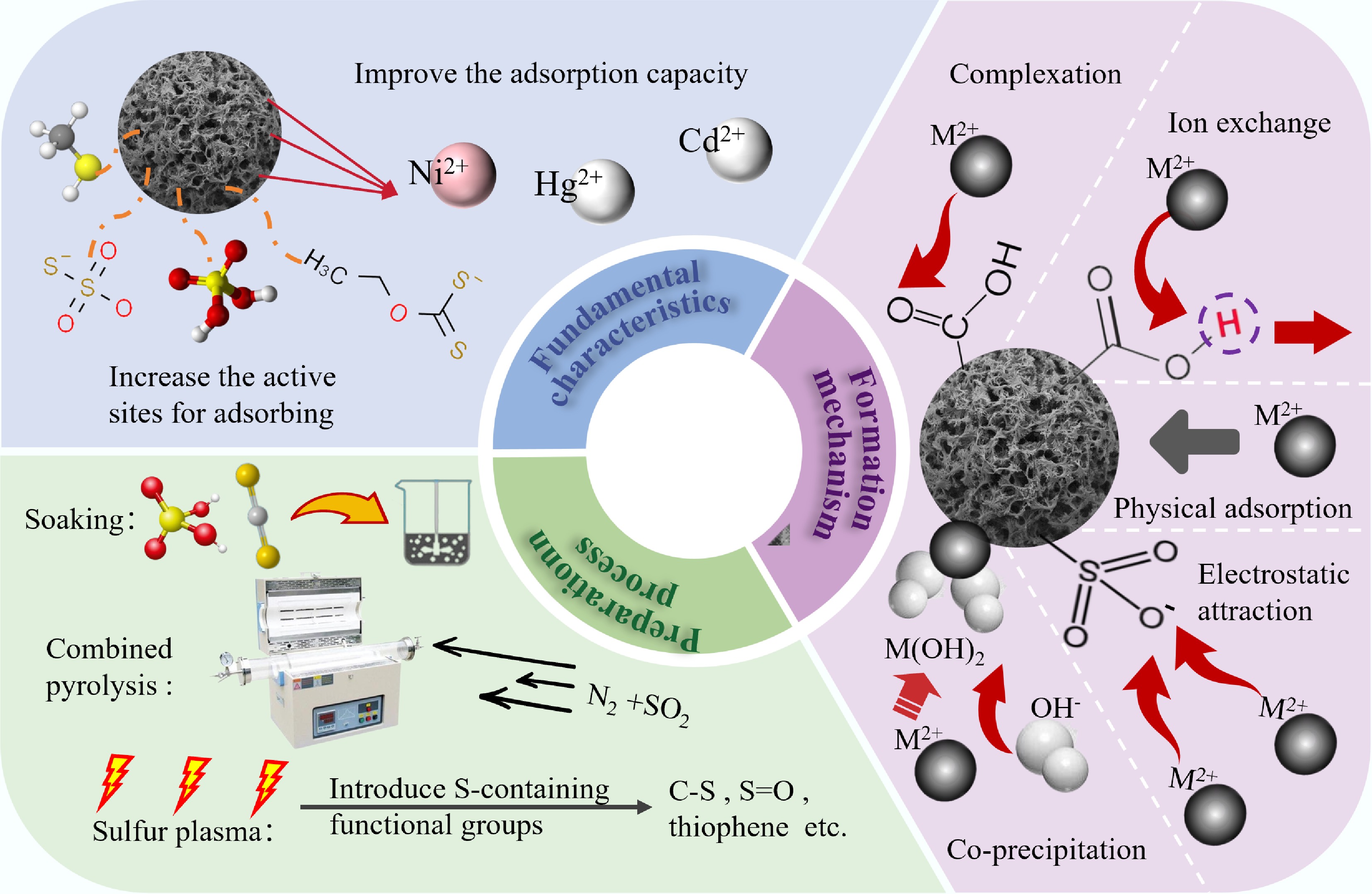

Sulfur (S) doping is also meaningful for the improvement of BC, in terms of the passivation performance for heavy metals. Firstly, the S-containing FGs can form stable metal-sulfur coordination bonds with heavy metals, with bond energies higher than those of conventional O/N functional groups. Meanwhile, the thiophene sulfur (C-S-C) and sulfoxide/sulfonic acid (-SO3H) generated during the preparation process donate electrons to the π-conjugated system, increasing the surface negative charge density and enhancing electrostatic adsorption and ion exchange capacity[93]. Aforementioned mechanisms facilitate the remediation of agricultural soils contaminated with heavy metals. Sulfur radicals generated at moderate temperatures insert into aromatic rings, forming thiophenic bridges that kink the carbon layers and generate abundant wedge-shaped macropores (> 50 nm) interconnected with mesopores, thereby enlarging the overall surface area and improving mass-transfer kinetics for soil contaminants[94].

During the co-pyrolysis process, the sublimated S was converted to S radicals at the appropriate temperature, which could easily react with the biomass lignin component and form S FGs after pyrolysis[95]. S FGs, as a positive factor for improving the adsorption performance of BC, can be divided into organic S (e.g., C-S, -C-S-C-, and thiophene), and inorganic S (e.g., sulfate, sulfite, and sulfide)[96]. Methods for introducing S sources are elemental S, CS2, SO2, and H2SO4. Notably, SO2 is added to the pyrolysis atmosphere, which is easier to fix in BC than adding a liquid or solid reagent[97]. Besides, different sources for introducing S result in significant changes. For instance, the BC derived from impregnation exhibited a high abundance of FGs (-SO3H), which was nearly twice that obtained through treatment with concentrated S-containing reagents.

Simultaneously, S-containing BC had a greater adsorption efficiency for Hg0 and Hg2+ than S-free BC. Specifically, Na2S-modified BC showed a high adsorption efficiency for Hg(II), which was 1.77 times higher than that of the pristine BC. BC impregnation with Na2S and KOH enhanced its adsorption performance for pollutants due to the development of precipitate substance and FGs on the surface, and more active sites also contributed to its adsorption[98]. Similarly, CS2 and corn straw were co-heated at low temperature to prepare sulfurized BC passivator, and the findings indicated that the contents of bioavailable-Pb and -Cd in soil decreased by 59.22% and 70.28% by S modified BC[99]. This process introduced more S-containing groups with greater affinity to metal due to complexation, such as -OH, C=S groups that can form Hg-S and Hg-O bond.

Furthermore, S-containing FGs can enhance passivation capabilities of Cd ions by BC. For example, a novel Na2S-modified BC was prepared by one-step pyrolysis method to passivate Cd ions in soil, showing a passivation performance (37.27%), nearly three times that of raw BC[98]. The presence of S-containing FGs on BC surface facilitated removal efficiency by creating an electrostatic attraction to Cd ions and forming strong complexes with Cd-S. In addition, S FGs on the BC surface facilitated the adsorption of nickel ions. BC introduced C-S, and S-H using S(α) as a doping reagent, reducing the bioavailability of Hg by 56.8 % and Pb by 34.1 % in soil[100]. This might be due to weak acid (heavy metal) and weak base (S) interaction, which increased the affinity of S to heavy metals[101]. Figure 3 describes the preparation and formation mechanisms of S doping in detail.

In conclusion, S-doped BC presents strong attraction to heavy metals (particularly Hg ions and Cd ions), and many advanced studies have verified that BCs with S modification are potential green adsorbents. In addition, various treatment methods and reagents can affect the adsorption properties and physical structures of BC. Based on the above points, relevant studies are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. BC adsorbents doped with S for heavy metal removal

BC Preparation technology Contaminant Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g)—Langmuir Adsorption mechanism Ref. Corn straw Acid ammonium persulfate oxidation process, hydrophilic treatment Pb(II) 184.5 Surface complexation, precipitation and reduction reactions [90] Corn straw Mixing and stirring modification of biochar with Na2S solution Hg(II) 5.71 Precipitation, chemisorption, electrostatic interaction, chemical interaction mechanism, ion exchange [98] Corn straw Adding ammonium tetrathiomolybdate solution to calcined biochar, heating in autoclave Cd(II) 139 Surface complexation, electrostatic attraction, ion exchange, chelation [100] Wood chips S element impregnation pyrolysis, sulfurization Hg(II) 107.5 Surface adsorption, functional groups and chemical bonds [102] Sugarcane bagasse Single step reaction with isothiocyanates during pyrolysis Cd(II) 87.5 Surface complexation, coprecipitation, ion exchange, electrostatic attraction [103] Cr(III) 25.5 Ni(II) 41.0 Pb(II) 41.2 Pomelo peel H2SO4 treated biochar and chloroacetyl chloride mixed with N, N- two methylformamide and reflux 24 h at 100 °C Pb(II) 420 Coordination, ion exchange, chelation [104] Phosphorus-doped BC

-

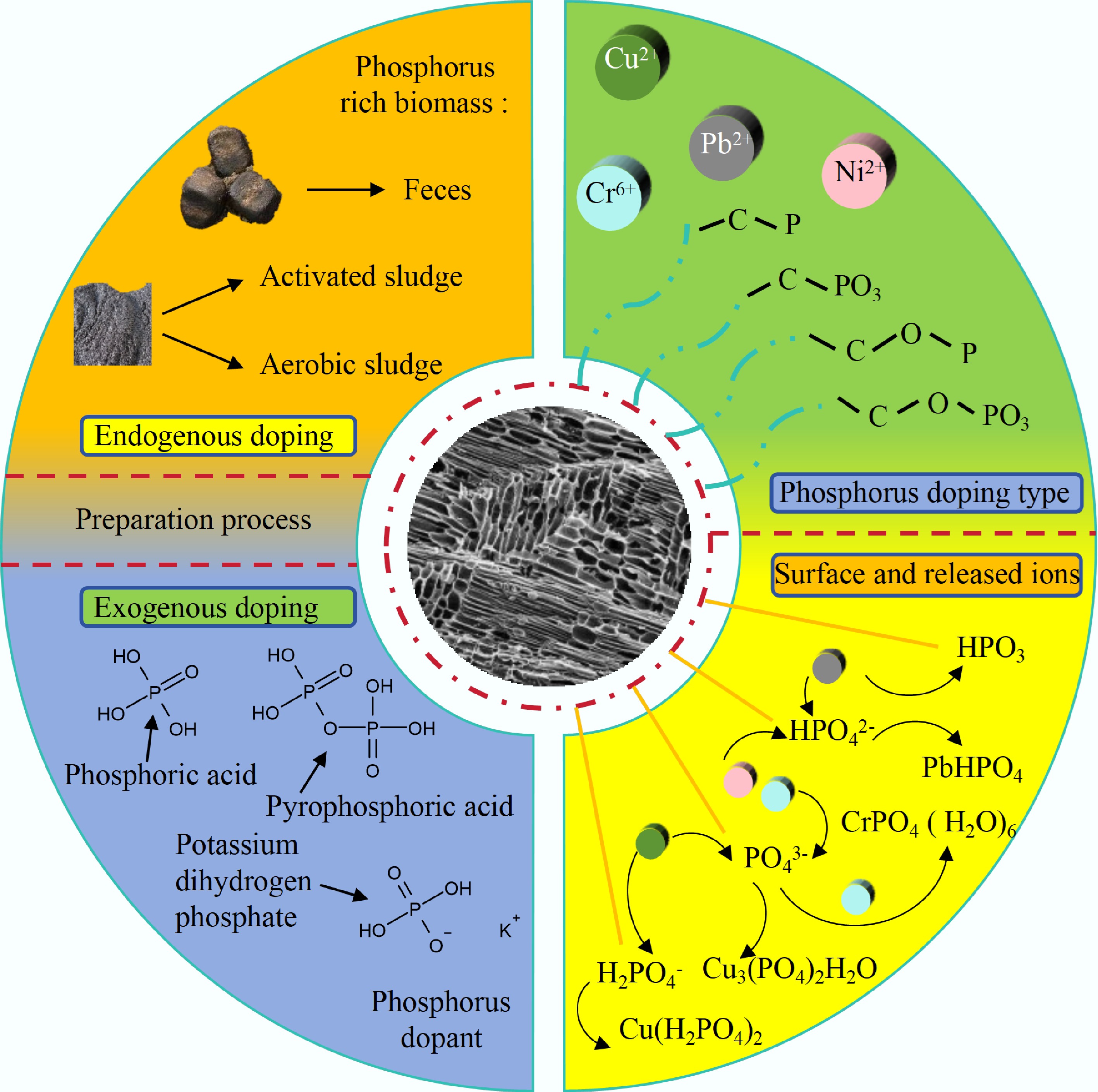

Compared with pristine BC, phosphorus—whether surface-loaded or internally doped—generates additional adsorption sites for heavy-metal removal via ligand complexation or precipitation, and concurrently increases the specific surface area by refining the internal pore structure. Moreover, P-rich BC not only contributes to environmental restoration and plant growth but also alleviates the potential negative impacts of excess phosphorus in the environment[105]. Phosphate precursors decompose into P–O–C linkages that act as rigid spacers during pyrolysis, preventing layer restacking and creating interlayer voids; this results in a 2–3-fold increase in mesopore volume and a concomitant enhancement in SSA, while maintaining structural integrity under wetting–drying cycles[106].

Metaphosphates and polyphosphates, as P-rich reagents, can provide abundant FGs for BC. Metaphosphate doping introduces phosphorus-containing functional groups—such as P–OH and P=O onto the BC surface. The incorporation of metaphosphate markedly increases the specific surface area and simultaneously elevates the densities of –COOH and –PO3 moieties. These combined modifications create abundant active sites that effectively passivate heavy metals from environmental media[107]. For instance, BC modified with metaphosphates could efficiently enhance the passivation capacity for heavy metals by the linkage[108]. Furthermore, precipitation formed by polyphosphate (mainly PO43–, HPO42–, and H2PO4–) and heavy metal ions (such as Cd, Cu, and Cr(VI) ions) was one of the primary processes for heavy metals passivation[109]. Simultaneously, P-doped BC could release various phosphate ions to combine with heavy metals that also take part in the establishment of Cd(H2PO4)2, Cu3(PO4)2H2O, and CrPO4(H2O)6 through complexation reaction.

The preparation methodology is categorized into endogenous and exogenous approaches based on the elemental composition of the biomass feedstock. Biomass materials rich in P, such as manure and sludge, can be directly prepared into P-containing BC, which is termed as endogenous doping. For instance, the dried manure containing rich P element was utilized to synthesize PBC to passivate Pb ions in soil. The result indicated that Pb ions passivation was primarily caused by the creation of phosphate precipitation (Pb9[PO4]6)[110]. Additionally, the exogenous approach, as an important means of P doping, has achieved element introduction through a variety of P-containing reagents, including H3PO4, pyrophosphoric acid (H4P2O7), and monopotassium phosphate (KH2PO4). H3PO4 activation not only can create -C-P-C- linkage to enhance the peculiarity of structure, but also improve the performance of BC passivation for heavy metals. Significantly, P-loaded BC derived from fiber that possessed rich P FGs was synthesized, which was utilized for the elimination of Cr(VI) through the redox reaction between Cr(VI) with electron-rich C-O, P-O, and C-P bonds[111].

In conclusion, there are three main points of the influences of P doping on BC and the applications of heavy metal adsorption: (1) The introduction of P enhances the cross-linking structure of C, promotes the formation of developed pore, and improves SSA; (2) The immersion treatment of P-containing chemical reagents is the main method of exogenous doping and introduces various P-containing FGs; (3) Fundamental processes of P contribution involved in the adsorption of heavy metals are complexation, precipitation with metal ions, and ion exchange. The co-precipitation of phosphate released from BC and complexation of chemical bonds with metal ions greatly enhance the adsorption performance. The application of P-doped BC for heavy metal passivation is shown clearly in the Table 5. A basic introduction and description of the P-doped BC is given in Fig. 4.

Table 5. BC adsorbents doped with P for heavy metal removal

BC Preparation technology Contaminant Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g)—Langmuir Adsorption mechanism Ref. Oleifera shells Ammonium polyphosphate pretreatment, high temperature carbonization Pb(II) 723.6 Chemisorption [21] Coffee shells (NH4)3PO4 pretreatment, in situ pyrolysis Cr(VI) 235.5 Adsorption, reduction [72] Apricot stones H3PO4 thermochemical activation Pb(II) 179.48 Surface adsorption, chemisorption, ion exchange, ion capture [112] Cd(II) 105.84 Ni(II) 78.8 Undaria pinnatifida roots Ca (NO3)2·4H2O and (NH4) 2·HPO4 mixed, one pot hydrothermal Cu(II) 99.01 Surface complexation and cation exchange [113] Other element-doped BC

-

Apart from N, O, P, and S doping, other element doping and multi-element co-doping BC can demonstrate effective removal of heavy metals by enhancing its pore structure and introducing various FGs on its surface[114,115]. For example, it could be inferred that the ion exchange of K+ in K-rich BC made a significant addition to the passivation process of heavy metal ions by comparing the changes of peak values before and after adsorption[114].

Nevertheless, most element-doped BC is prepared through external doping. For instance, magnetic BC doped with Ce by the chemical coprecipitation method was rich in magnetite structures and had more surface hydroxyl groups (-OH), enhancing the adsorption of Sb(V)[116]. Similarly, magnetic BC doped with La by the chemical co-precipitation method, in which surface -OH increased significantly, exhibited 7.52 times adsorption capacity for Sb(V) compared to the pristine BC[115].

In recent years, many multi-elements co-doped BCs have shown excellent removal effects for heavy metals compared to single atom doping due to multi-atom synergy. Unlike single-element doping, the simultaneous introduction of two or more heteroatoms creates a heterogeneous yet complementary array of functional groups on the BC surface. Previous researchers used coffee and (NH4)3PO4 to obtain N/P co-doped BC through one-step pyrolysis, and the SSA was significantly increased to 1,130 m2/g. Meanwhile, the peak values of quaternary nitrogen (N-Q) and C-P bonds decreased significantly before and after the reaction, indicating that both of them served as electron donors to reduce Cr(VI)[72]. Similarly, N/S/Fe tri-doped BC achieved high Cr(VI) removal through the combined reduction by pyridinic-N and Fe2+, coupled with strong electrostatic attraction between surface functional groups and the contaminants[117]. In addition, Fe/N co-doped BC was prepared with pomelo peel and FePc (C32H16FeN8). The successful doping of Fe and N provided a substantial amount of active sites and significantly enhanced the electron transfer efficiency. Compared with the sole introduction of N, the additional doping of Fe brought more reduction ability, thereby exhibiting superior performance[118]. Consequently, multi-element doping represents a readily accessible route for fabricating high-performance EDBC.

In summary, most of the doping is realized through external doping with relatively complicated steps, while for some protoplasm or raw materials that meet specific requirements, self-doping can be carried out through simple one-step pyrolysis. Element doping has many positive effects on BC. In addition, various groups can be introduced into BC during element doping, thus affecting the number of active sites and electron transfer, finally showing excellent removal performance toward heavy metals. Table 6 clarifies the preparation methods, the maximum uptake amount, and corresponding mechanisms of heteroatom-doped BC over the past 5 years.

Table 6. BC adsorbents doped with other elementals for heavy metal removal

BC Preparation technology Contaminant Maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g)—Langmuir Adsorption mechanism Ref. Phragmites australis Synthesis of Ce doped magnetic battery by chemical co-precipitation and dissolution thermal method Sb(V) 25 Hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attraction and ligand exchange, intrasphere complexation [116] Corn straw Biomass and boric acid were mixed, pyrolyzed, in-situ doping Fe(II) 132.78 Chemical complexation, ions exchange, and co-precipitation [119] Rice straw Iron and (3- amino propyl) triethoxy silane (APTES) complex, doped with Fe and NH2 radicals. Cr(VI) 100.59 Precipitation, surface complexation [120] Zn(II) 83.92 Electrostatic attraction, reduction, complexation Rice husks Pyrolysis, endogenous doping Cd(II) 154.22 Complexation, electrostatic attraction, sedimentation, cation exchange [121] -

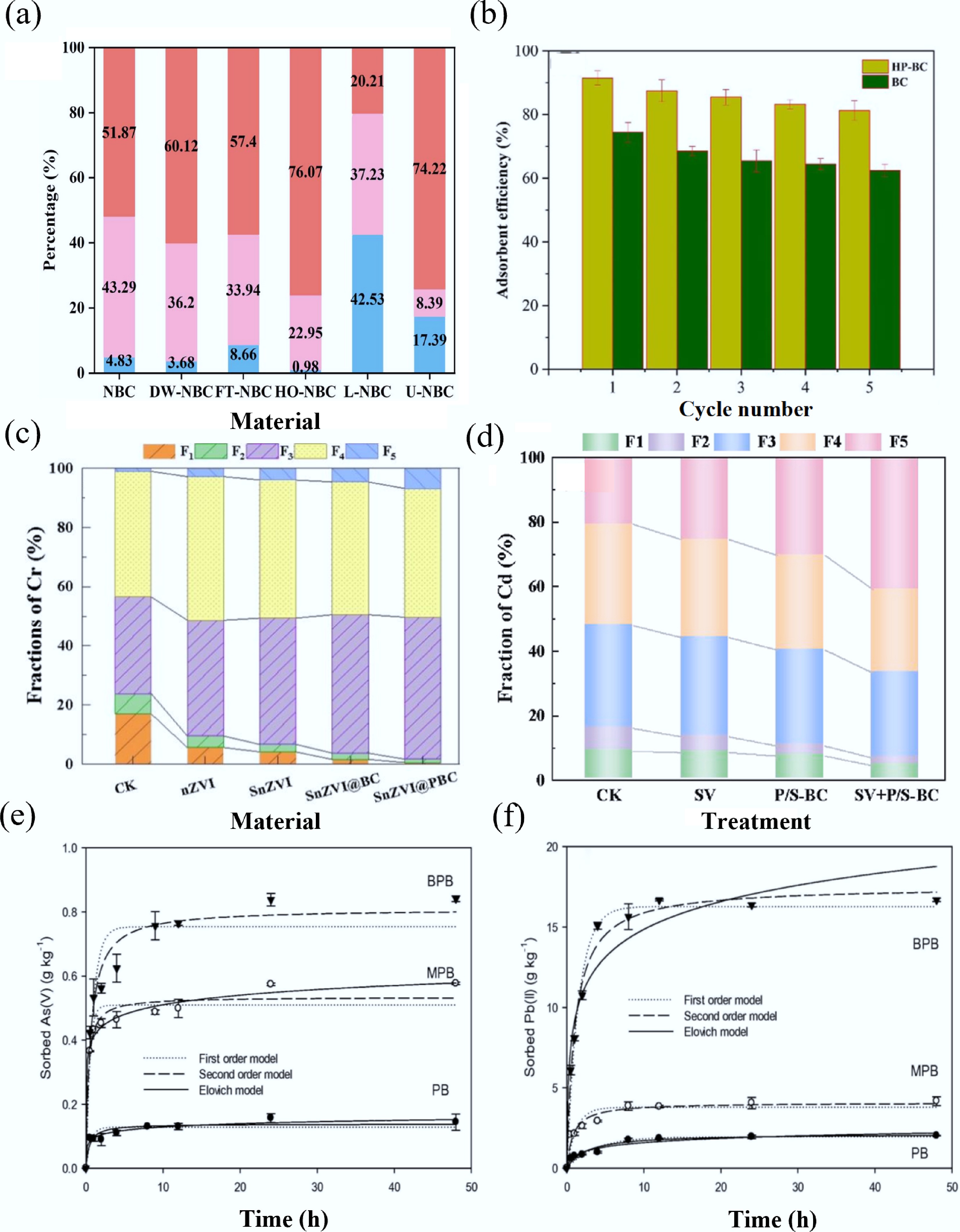

N-containing FGs mainly refer to the amino FGs attached to the periphery of materials, which can improve the basic properties of BC[122]. Because of the rich electronic properties of unpaired electrons, amine groups can be used as a preferred adsorption center for BC/substrate contact, which promotes the adsorption of heavy metals[123]. In general, N FGs do not significantly enhance BC structural properties, but they can effectively passivate heavy metals through multiple mechanisms, including complexation, electrostatic attraction, and ion exchange[122]. Earlier research has indicated that amino groups are powerful complex FGs that could effectively interact with heavy metal complexes because of their high stability constants. For example, the number of pyridine N groups decreased significantly after the adsorption reaction, suggesting that it played a role in surface complexation with Cu ions[124]. In addition, for N-doped BC obtained from in-situ pyrolysis of pretreated coffee shells with (NH4)3PO4, the N-containing FGs on its surface could not only serve as electron donors to reduce Cr(VI), but also participate in passivating Cr(VI) as active sites[72]. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 5a, Wang et al. investigated the outstanding passivation property of Cd ions by N-doped BC, which was mainly due to the low hydrophilicity and high alkalinity caused by N-containing FGs on the BC surface[125]. Table 7 provides a summary of the maximum adsorption capacity of N-containing FGs for the passivation of heavy metals using carbon passivators.

Figure 5.

(a) Percentage distribution of Cd speciation on NBC and aged NBC[125]. (b) Regeneration and reusability of biochars[129]. (c) Influence of various materials on percentage variation of Cr fractions in the contaminated soil[112]. (d) Effects of different passivators on the morphology distribution of Cd[134]. (e) As(V), (f) Pb(II) adsorption kinetics data[143].

Table 7. Effects of nitrogen-functional carbon adsorbents on heavy metal removal

Material Heavy metal Qmax (mg/g) Kinetic model Isotherm Functional groups (FGs) Ref. Coffee shells Cr(VI) 95% Pseudo-second-order (PSO) Slips -N–Q [72] Agarpowder 1,5-Diphenylcarbazide, FeCl3 Cr(VI) 144.86 PSO Langmuir -NH2, -NH3+ [64] Rice straw Cd(II) 69.3 PSO Langmuir -NH2 [68] Rice husks, chlorella pyrenoidosa Cu(VI) 29.11 PSO Langmuir -NH2 [126] Plant waste and aquatic animal waste Ni(II) 44.78 PSO Freundlich -NH2, -NH3+ [127] Oxygen-containing FGs

-

O-containing FGs are important factors affecting the surface reaction, hydrophilicity, electrical properties, and catalytic properties of carbon[127]. -OH, -COOH, epoxy (-COC-), and carbonyl (-C=O) groups are the most common FGs, which can act as functional active sites to create composites that include metals, organic molecules, or other different atoms[128]. Additionally, the O-containing compounds such as -OH and -COOH groups from adsorbents can easily interact with heavy metal ions, thereby enhancing the passivation performance[98]. For example, -OH and -COOH groups served as the primary influencing factors for Pb ions passivation, and they could combine with Pb ions to form complex compounds[107]. As shown in Fig. 5b, BC doped with oxygen-containing FGs also demonstrates long-term stability in heavy metal passivation[129]. Moreover, the quantity of O-containing FGs of BC was greatly increased after acid modification, and many -OH and -COOH groups were involved in the complexation with Pb and Cd ions[91]. Table 8 provides a summary of the excellent passivation property of oxygen-containing FGs for the passivation of heavy metals using carbon passivators.

Table 8. Effects of oxygen-containing carbon adsorbents on heavy metal removal

Material Heavy metal Qmax (mg/g) Kinetic model Isotherm Functional groups (FG) Ref. Pines Pb(II) 55 Pseudo second-order (PSO) Freundlich -OH, -COOH [83] Rice straw Cd(II) 117 PSO Freundlich -C=O, -OH, -C-O [88] Sawdust Cr(VI) 45.88 PSO Freundlich -OH, -C=O, -C-O [130] Grape pomace Pb(II) 137 PSO Sips -OH [131] Sulfur-containing FGs

-

S-containing FGs are of great significance for heavy metals adsorption by BC. Compared with C atoms, S atoms have increased electron attraction, which increases the surface polarity and makes the surface more negative electrically, thereby attracting positively charged heavy metal ions[132]. Earlier studies have shown that the polarization of lone pair electrons of S could enhance the chemical reactivity of S-doped carbon materials, significantly enhancing the attraction toward heavy metals[133]. Based on Pearson's theory, S functional groups can act as a soft base and interact with heavy metal ions (which are soft acids) to improve the removal effect[123]. As shown in Fig. 5d, Bi et al. explored the use of NaS in the molten salt medium to introduce an S-containing motif on BC to promote the process of passivation of Cd ions within the soil system[134]. Besides, through the analysis of XPS before and after the adsorption of NaS-modified BC, it was found that the peak became larger after adsorption. Qu et al. introduced high concentrations of S-containing groups on BC surface by grafting magnesium xanthate, which greatly improved the ability to passivate Cd ions[135]. The abundant pore structures of S-modified BC provided sites that facilitate passivation, and the processes with ion exchange and π-π interaction increased, providing additional chances for binding of heavy metal ions with S-containing FGs, thus resulting in excellent passivation properties (Table 9).

Table 9. Effects of sulfur-containing carbon adsorbents on heavy metal removal

Material Heavy metal Qmax (mg/g) Kinetic model Isotherm Functional groups (FG) Ref. Corn straw Cd(II) 139 Pseudo-second-order (PSO) Langmuir Mo-S [100] Wood Hg(II) 107.5 PSO Langmuir C-SOx- [102] Rice husks Cd(II) 137.16 PSO Langmuir C=S [135] Luffa sponge Cr(VI) 312.50 PSO Langmuir C-SH [136] Sugarcane bagasse Pb(II) 95.7 PSO Langmuir -N=C=S [103] Cr(III) 90.7 Cd(II) 87.5 Pine-tree needle Hg(II) 48.2 PSO Freundlich C-S [137] Wheat straw Hg(II) 95.5% PSO Langmuir C-S [138] Phosphorus-containing FGs

-

Research shows that introducing P heteroatoms can create extra adsorption sites for BC and promote significant electron delocalization, which improves the reduction of Cr(VI) ions by offering Lewis base sites and enhancing the hydrophilicity of the surfaces[109]. P can be introduced into BC by H3PO4 impregnation, which maintains the porous composition of original materials and enhances the SSA of the BC by creating micropores[111]. Modified BC can precipitate with metal ions and improve the adsorption ability. Simultaneously, H3PO4 can promote the dehydration, aromatization, crosslinking, and porous action of biomass during carbonization. As shown in Fig. 5c, H3PO4-modified BC demonstrated strong Cr(VI) reduction capability toward KOH-modified BC. Moreover, phosphate and polyphosphate salt bridges formed on BC through the thermochemical treatment of H3PO4 significantly enhanced carbon crosslinking, resulting in an improved adsorption structure[112]. Table 10 summarizes the maximum adsorption capacity of P-containing FGs used in carbon adsorbents for removing heavy metals, including the most suitable kinetic and isothermal models, as well as the impact of particular FGs on the adsorption process of heavy metals.

Table 10. Effects of phosphorus-containing carbon adsorbents on heavy metal removal

Material Heavy metal Qmax (mg/g) Kinetic model Isotherm Functional groups (FGs) Ref. Camellia oleifera shells Pb(II) 723.6 Pseudo-second-order (PSO) Langmuir O-P-O, P=O, P-N-C, P-O-C [21] Corn stalk Ce(III) 177.26 PSO Langmuir P-O [139] Lotus leaves Pb(II) 321.52 PSO Freundlich P=O, P-O-C, HO-P=O [140] Fish scales Cu(II) 505.8 PSO Langmuir P-O, P=O [141] Cd(II) 327.2 Pb(II) 661.2 Olive oil mill press waste Pb(II) 57.78 PSO − PO43−, ester sulphate [142] Other FGs

-

FGs involving the above elements significantly contribute to the absorption of heavy metals, while some other heteroatom-doped FGs also have a remarkable impact on promoting the removal of heavy metals by BC. As shown in Fig. 5e, f, Wang et al. prepared birnessite-modified BC, in which sodium-manganese hydroxide particles had an intense influence on As(V) and Pb(II), and the adsorption efficiency was notably enhanced[143]. Similarly, Zhang et al. confirmed that the surface of BC with loaded MnO2 was rich in Mn-OH groups, which had a high ability to adsorb heavy metal ions and could be used as an efficient adsorbent for the removal of heavy metal ions from the water system[144]. Besides, MgO nanoparticle- embedded, N-self-doped BC showed excellent Pb(II) removal efficiency. The remarkable adsorption capability was strongly linked to the plentiful surface FGs present in the materials[74]. Furthermore, the addition of iron can also introduce related groups to facilitate the removal efficiency of BC. Agrafioti et al. showed that the Fe(OH)3 group in Fe-impregnated BC could promote the adsorption of As by co-precipitation[145]. Table 11 summarizes the highest removal capacity of heteroatom FGs for the removal of heavy metals by carbon adsorbents, including the most suitable kinetic and isothermal models, as well as the impact of particular FGs on the adsorption process of heavy metals.

Table 11. Effects of heteroatom-containing carbon adsorbents on heavy metal removal

Material Heavy metal Qmax (mg/g) Kinetic model Isotherm Functional groups (FG) Ref. Rice husks Cd(II) 154.22 Pseudo-second-order (PSO) Freundlich -OH, -COOH, C=N, -NH2 [121] Chicken manure Cu(II) 258.22 PSO Langmuir Fe-O, Fe-OH, C-OH [146] Pb(II) 390.60 As(V) 5.78 Rice husks Cd(II) 104.68 PSO Langmuir Mg-O, -OH [147] Cu(II) 173.22 Zn(II) 104.38 Cr(VI) 47.02 -

Resorting to the aforementioned mechanisms, the application of EDBC is a method to achieve the conspicuous passivation efficacy of the heavy metal in soil through materials-soil interactions. Furthermore, it is also feasible to utilize EDBC to improve the physical and chemical properties of soil, thereby resulting in a reduced activity of heavy metals indirectly. For instance, with P-doped BC, Li et al. conducted a 90-d soil incubation experiment to elucidate the changes in the migration tendency of Pb and Ce in soil. The addition of P-doped BC brought an obvious enhancement of the passivation content of Pb and Ce (161.4% and 43.9% respectively), which demonstrated a favorable inhibition of Cd leaching under different conditions[148]. Liu et al. fabricated nano-TiO2-doped BC and employed it in a Cd-contaminated plant system. The results showed that by facilitating the formation of humid substance and the increase of soil cation exchange capacity, the Cd passivation performance was double[149]. Meanwhile, added into agricultural soils, EDBC presented further growth promotion capacity for agricultural plants by alleviating environmental stress. For example, restraining Cd and Zn activity (which declined by 57.79% and 35.64% respectively), Mn/Fe co-doped BC effectively decreased their bio-toxicity and thereby boosted the vigorousness in photosynthesis and other life activities of foxtail millet[150].

EDBC also possesses superior applicability in heavy metal-contaminated farmland soils. In the in-situ experiments, alginate and FeCl3 were pyrolyzed to prepare magnetic Fe-doped BC, and the product exhibited a macroporous structure, guaranteeing the adsorption ability for total Cd and As (dropped to 49.46% and 45.39%, respectively) in soil. Meanwhile, by adding water, the magnetic BC sphere could float above the mixture of soil and water, thus realizing an effective separation from the polluted soil body (with an 87.67% recovery rate)[151]. Wang et al. conducted an incubation experiment followed by freeze-thaw-cycle experiment to illustrate the stability and ageing resistance ability of Mn-doped BC. The toxicity characteristic leaching procedure (TCLP) concentrations of Cd, Zn, and Pb decreased significantly by 66.80%, 25.39%, and 99.68%, respectively, demonstrating effective attenuation in the bio-toxicity of heavy metals attributed to the repressed mobility[152].

EDBC combined with phytoremediation

-

Phytoremediation refers to a plant-centered technique, utilizing the absorption characteristics and the transport process of plants to realize the transfer process of heavy metals from the soil environment to stems, leaf, and other aboveground parts of the plant body. Subsequently, through unified harvest and management, the content and toxicity of heavy metals can be diminished[153]. Compared with using EDBC alone, the combined application of BC remediation and phytoremediation is an advanced strategy that leverages synergistic effects: it enhances key soil physicochemical properties—particularly aeration and aggregate structure—thereby creating more favorable conditions for subsequent plant growth[154]. Concurrently, the organic substances secreted by plant roots can augment the immobilization of heavy metals in the soil, facilitated by BCs. This dual facilitation constitutes the mutual reinforcement between phytoremediation and BC amendment in diminishing heavy metal bio-availability[155]. In pot experiments, P/S co-doped BC was fabricated through one-pot pyrolysis technology. During the contaminated farmland simulation experiments, P/S co-doped BC was applied in conjunction with crushed smooth vetch, a green manure crop. After treatment, soil organic matter (SOM) and available P (AP) contents surged (increased by 34.52% for SOM and 86.17% for AP) compared with untreated soil, while returned smooth vetch could further boost the increase in AP content. Therefore, the tolerance of smooth vetch to Cd stress was significantly enhanced[134].

With the characteristic of multi-valence, Cr exhibits a more complicated behavior in agricultural soils, and more detrimental intermediate products tend to be generated during the remediation process, which impedes the application of the phytoremediation technique[156]. To overcome such a dilemma, Jia et al. selected O-doped BC synthesized by calcining corn stalk, and explored the underlying mechanism of BC and reactive oxygen species (ROSs) generated by plants through analyzing the concentration of different Cr species and the detoxification led by pennisetum and ROSs it produced[157]. The result implied that decreased concentration of ROSs activated the uptake of Cr ions (80.60%, increased by 14.46% compared to sole phytoremediation). On the other hand, the antioxidase system of pennisetum was provoked to facilitate the cell wall fixation of Cr ions (Cr content proportion of the cell walls and vacuoles was increased by 18.12%), thus suppressing the intracellular damage inflicted. Therefore, a collaborative resistance mechanism of BC and plants was presented.

EDBC combined with microbial remediation

-

For farmland soil, in-situ immobilization of heavy metal pollutants, without interrupting normal cultivation and agricultural production routine, is crucial for the sustainability and cost-effectiveness[158]. Microbial remediation, referring to a heavy metal immobilization strategy that takes a specific microbial community as the core executor, is further explored in contaminated agricultural soils[101]. The common techniques of cooperative immobilization by BC and microorganisms are mainly classified into two methods: one is to bio-immobilize heavy metals by regulating the indigenous functional microbial communities in soil[159]; the other is to concurrently apply BC along with microbial agents, namely introducing exogenous microbial communities to intensify the suppression of soil heavy metal contaminants[160].

The increase in indigenous functional microbes count primarily ascribes to the restriction of heavy metals activity and a more appropriate living environment for them. These enhanced microbial communities cooperate with EDBC in the immobilization of heavy metals. For instance, Shang et al. prepared rice husk-derived BC, which could be regarded as Si-doped BC due to the high content of Si-based compound. A simulation experiment was conducted, and the variation that occurred in the bacterial community was also observed. The outcome showed that as the incubation proceeded, the diversity and abundance of microbes related to the immobilization of Zn ions and Cr ions were significantly boosted (up to 69.01%–76.76%)[161]. In another study, S-doped BC was prepared for Cd passivation in agricultural soils. Pot experiment results showed a significant decrease in soil bio-available Cd (by 91.4%), which was attributed to the S-doped BC, and the corresponding changes occurred in the soil bacteria community. An activated mutual benefit among microorganism species was induced, collectively reducing the plant-available fraction of Cd ions[162].

For remediation involving exogenous bacterial species, EDBC with its characteristically large specific surface area (SSA) serves as an effective microbial carrier, facilitating microbial-mediated remediation[163]. Moreover, EDBC provides both essential nutrients and protective habitats for the colonization of microorganisms from environmental stress, therefore enhancing the abundance and activity of the introduced microbial agents[164]. Wei et al. prepared Fe/S-doped BC and consequently coupled it with the microbe agent to explore its performance on soil Pb immobilization and plant growth promotion. The results revealed that with the addition of Fe/S-doped BC, the fraction of unstable Pb was diminished (by 55.43%). Moreover, the application of BC-bacteria composite could improve soil fertility (AK and AP elevated to 26.79 and 52.25 mg/kg, respectively). In this way, EDBC, combined with microbe, presented a superior immobilization capacity for heavy metals and an outstanding amelioration of agricultural soil fertility[165].

-

EDBC exhibited superior remediation performance and overcame the disadvantages of the pristine BC in the remediation of heavy metals in agricultural soils. Herein, various synthesis methods of EDBC were summarized, along with its adsorption mechanisms for heavy metals, including physical adsorption, electrostatic interaction, ion exchange, and others. The work systematically discussed how introducing different functional groups further regulates the physicochemical properties of EDBC, thereby influencing the passivation mechanisms and the performance of different EDBC. Meanwhile, several application strategies of EDBC for agricultural soils were comprehensively reviewed. Overall, EDBC has shown wide applicability and enormous potential in environmental and agricultural fields. However, there are still some limitations and deficiencies in the utilization of EDBC to resolve the contamination of agricultural soils. Therefore, to further propel its application, future work should focus on: (i) Introducing target functional groups. More doping strategies should be developed to accurately prepare functional BC as required, fitting various contamination backgrounds; (ii) Addressing the potential of metal release. The risk of secondary heavy metals leaching needs to be addressed to ensure the sustainability and safety of this strategy; (iii) Expanding passivation studies. Current adsorption research is significantly insufficient in terms of anionic metal groups (such as SbO3– and FeO42– groups), thus corresponding analyses should be conducted to clarify the remediation performance of EDBC on them.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, methodology: Qu J, Chu H; investigation, formal analysis: Yu R; visualization, writing − review and editing: Wang S, Liu T, Tao Y, Han S, Zhang Y; writing − original draft preparation: Qu J, Chu H, Wang M; supervision and funding acquisition: Zhang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was supported by the Hainan Province Key Research and Development Program (ZDYF2024SHFZ144), the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFD1501005), and Heilongjiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Soil Protection and Remediation.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Preparation methods and characteristics of EDBCs are reviewed.

Passivation mechanisms of heavy metals by EDBCs are systematically analyzed by discussing different roles of functional groups on the surface of EDBCs.

The applications of EDBCs for farmland soils with heavy metals contamination are introduced.

Future prospects for the further development of EDBCs are proposed.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Qu J, Chu H, Wang M, Yu R, Wang S, et al. 2025. Synthesis, mechanism, and application of element-doped biochar for heavy metal contamination in agricultural soils. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 1: e002 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0004

Synthesis, mechanism, and application of element-doped biochar for heavy metal contamination in agricultural soils

- Received: 05 July 2025

- Revised: 09 August 2025

- Accepted: 27 August 2025

- Published online: 17 September 2025

Abstract: Biochar exhibits excellent passivation properties, is readily available from abundant sources, and is environmentally friendly, making it a promising option for remediating soils contaminated with heavy metals. However, the limited adsorption efficacy of pristine biochar hinders its application in practical remediation. This work systematically introduces pristine biochar and its adsorption mechanisms for heavy metals, including physical adsorption and electrostatic interaction. For nitrogen-, oxygen-, sulfur-, and phosphorus-doped biochar, the enhanced passivation performance and synthesis methods of these element-doped biochar were presented. Meanwhile, to elucidate the differences in the passivation performance and mechanisms of those biochar doped with different elements, the roles of functional groups were further discussed, and the application strategies of element-doped biochar in actual agricultural soils are presented to offer practical reference. Furthermore, some research prospects on elements-doped biochar were also proposed. This work provides a guideline for the application of biochar in the remediation of polluted agricultural soils.