-

The corpus luteum (CL) is a transient endocrine gland that typically regresses following the estrous cycle in non-pregnant animals, allowing the initiation of a new estrous cycle. However, during pregnancy, luteolysis is prevented through molecular mechanisms that maintain CL structural integrity and endocrine function. This results in the transformation of the cyclic CL into a pregnancy-sustaining CL, which secretes progesterone (P4) to support pregnancy. The primary function of CL is to secrete P4, a hormone essential for the elongation of the conceptus, establishing early pregnancy, supporting embryo implantation, and maintaining pregnancy[1,2]. Maintenance of luteal function is mainly dependent on its continuous P4 synthesis and support from an abundant vascular system[3]. The important causes of pregnancy failure in ruminants are failure of embryo attachment, early or late abortion due to the failure of CL formation, and luteal phase deficiency. The CL originates from follicles. Post ovulation, the CL is formed through luteinization, in which endometrial and granulosa cells differentiate into small and large luteal cells, respectively[4]. In addition, the CL contains endothelial cells, fibroblasts, various immune cells, and blood cells[5]; therefore, the process of CL formation is accompanied by a variety of physiological changes such as vascularization and inflammation. Before embryo implantation, P4 induces the expression of abundant receptivity-related genes in the maternal uterus, ensuring the establishment of a receptivity window[6]. This allows the blastocyst, which has undergone early development, to develop further into an elongated conceptus and engage in a series of conversations with the maternal uterus to induce maternal recognition of pregnancy (MRP)[7,8].

Interferon-τ (IFNT) is a type I interferon unique to ruminants and is the only known pregnancy recognition signal in ruminants. IFNT is produced by trophectoderm cells and induces MRP via a paracrine action on the endometrium[9]. In addition to inducing MRP, IFNT also inhibits the expression of the estrogen receptor (ESR1), and oxytocin receptor (OXTR) in the endometrium via paracrine signaling, thereby inhibiting the release of PGF2α pulses and protecting the CL from degeneration[10]. This is the conventional view that IFNT protects the CL from degeneration caused by the PGF2α pulse. However, with a deeper understanding of the IFNT, its mode of action has been further explored. Researchers have detected IFNT signals in the uterine vein and the expression of ISGs, such as ISG15, IFI6, and MX1, in the CL, liver, and other peripheral tissues[11,12]. Injecting IFNT through the uterine or jugular vein was found to block endogenous luteolysis and prolong the estrus cycle in sheep[13−15]. This suggests that, in addition to inhibiting the PGF2α pulse through intrauterine paracrine signaling, IFNT also plays a luteal protective role through endocrine secretion.

Although interest in luteolysis and functional maintenance studies in ruminants has grown rapidly, reviews on the biology of IFNT remain scarce. In this review, we discuss the latest advances in our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the effects of IFNT on luteal fate through paracrine and endocrine actions.

-

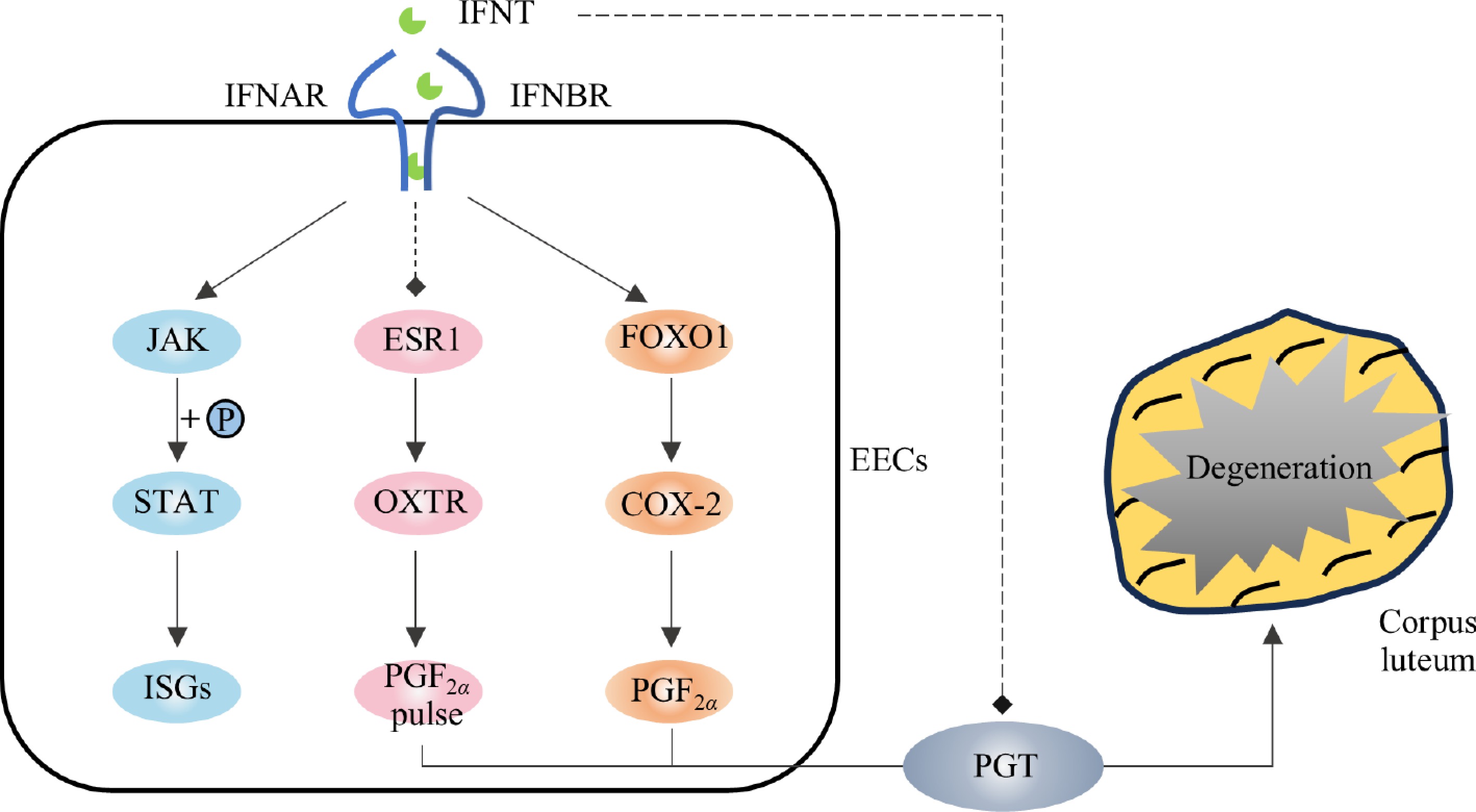

In species where the CL persists throughout pregnancy, the PGF2α pulse serves as a key regulator of luteolysis, and IFNT exerts a protective effect by paracrinely suppressing PGF2α pulses, thereby facilitating the transition of the cyclic CL into pregnant CL. On the 6th day post-fertilization, the conceptus began to express IFNT mRNA. In the conceptuses of sheep and cattle, IFNT mRNA levels peaked on the 14th and 20th days, respectively. At this time, the expression of OXTR in the endometrium has not yet been established, and high concentrations of IFNT prevent the PGF2α pulse from the endometrium by inhibiting the expression of ESR1 and OXTR (only OXTR was affected in cattle), thereby preventing CL from degradation and continuing pregnancy (Fig. 1). Recent studies have shown that the release of PGF2α pulses is regulated by a PGT-mediated mechanism[16]. IFNT inhibits PGT-mediated PGF2α pulse release through the JAK/EGFR/ERK/EGR1 signaling pathway, thereby protecting CL from degradation[17,18]. In addition to inhibiting the PGF2α pulse, IFNT induces the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in the uterus and increases the expression of PGE receptors (EP2 and EP4). PGE2 acts as a protective agent for the CL by extending its life and promoting P4 secretion[19−21]. Suppressing the expression of prostaglandin E synthase (PTGES) in uterine reinstates PGF2α pulses, triggering CL luteolysis[22].

IFNT inhibited the pulsing release of PGF2α but did not inhibit the expression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), and the production of PGF2α[23]. It has been reported that IFNT can upregulate the activity of COX-2 in the uterus of early pregnant cattle and induce the synthesis of PGF2α through the IFNT/FOXO1/COX-2 axis[23,24] (Fig. 1). This may explain the higher PGF2α base yield in pregnant ewes than in cyclic ewes[25,26]. However, studies have shown that the release patterns and concentrations of PGF2α in pregnant sheep are not significantly different from those in non-pregnant sheep[27]. This suggests that, in addition to paracrine action, there are other mechanisms or additional mechanisms that protect the CL from degeneration during luteolysis.

-

Ruiz-Gonzalez et al. used a radioimmunoassay to detect IFNT in uterine venous blood[28]. After being produced by the conceptus, IFNT reaches the CL via the utero ovarian plexus (paracrine) and systemic circulation and reaches peripheral tissues such as the liver through the systemic circulation to induce the expression of ISGs[29−31]. In addition, the induced expression levels of ISGs in the periphery were closely related to the size of the conceptus and the amount of IFNT[32]. These results indicated that IFNT acts on all tissues through endocrine secretion. Bott et al. investigated the endocrine effects of IFNT by injecting it into either the uterine or jugular vein of sheep; they discovered that it blocked endogenous luteolysis and extended the estrus cycle[14,33]. Therefore, the IFNT endocrine system may be another form of protecting pregnant CL formation during pregnancy, in addition to the paracrine manner. In this paper, we summarize relevant studies on endocrine-mediated luteum protection by IFNT.

IFNT induces the expression of ISGs in luteum

-

The JAK/STAT signaling pathway plays a crucial role in enabling IFNT to exert its downstream effects[34], with genes encoding the STAT family, key transcription factors of this pathway, being strongly expressed in the CL during early pregnancy[35]. After activating the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, IFNT promotes the expression of a large number of type I ISGs (MX1, ISG15, OAS1, and IRF3) (Fig. 2). These ISGs are key genes that are expressed significantly more in both the CL and uterus during early pregnancy than in cyclic subjects during the same period[36,37]. Luteal cells (LCs), endothelial cells, and endometrial cells respond to IFNT[38−40]. Therefore, the protective effects of IFNT on the luteus may be related to ISG expression. Indeed, the mRNA expression of ISG15 was detected in the CL, endometrium, and liver on both the same and opposite sides of the injection site after IFNT was administered to the uterine or jugular veins of sheep[41]. Similarly, we detected the expression of ISG15 mRNA and protein in the CL of pregnant goats, and the expression level was highest on the 18th day of pregnancy, which was consistent with the secretion trend of IFNT (data not published). These results suggest that IFNT induces ISG expression in CL, and ISGs induction may be an important mediator by which IFNT promotes the transition from the cyclic CL to the pregnant CL in ruminants.

IFNT regulates the production and metabolism of PGs in CL

-

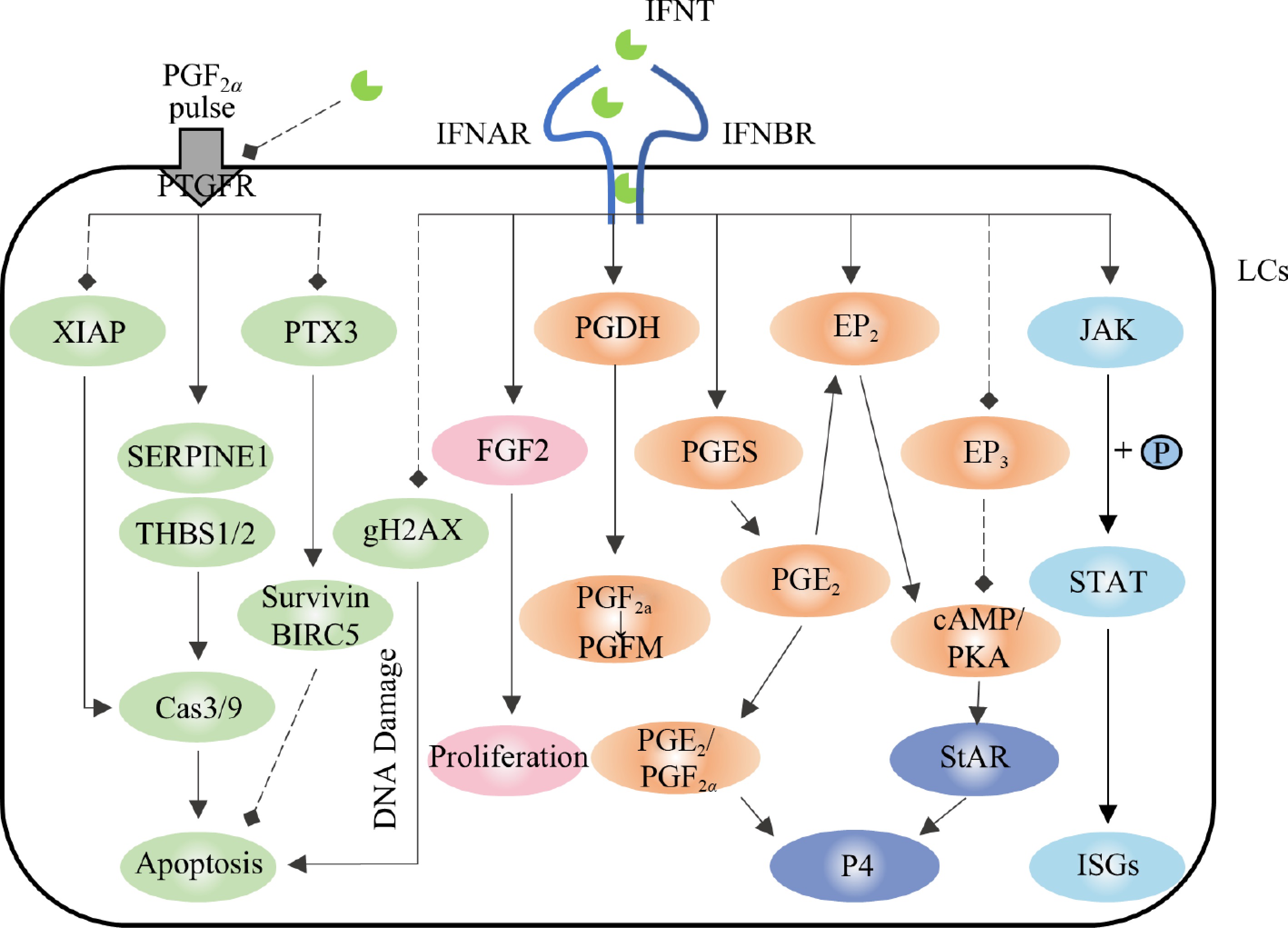

The prostaglandin (PG) auto-amplification pathway is present in the CL. PG biosynthesis in the CL selectively directs PGF2α during luteolysis and selectively directs PGE2 during pregnancy[22,42]. PGF2α significantly increased the expression of COX-2, PTGFS, and carbonyl reductase 1 (CBR1) and the synthesis of PGF2α in luteal cells via the NFKB signaling pathway[43,44]. Many reactions induced by PGF2α, such as decreased P4 synthesis and increased endothelin-1 (EDN1) and cytokines, also increase PGF2α production in the CL[45]. During pregnancy, endometrial PGE2 is transported to ovaries, further inducing the synthesis of PGE2 in the CL and activating the signaling of EP2 and EP4 in the CL while inhibiting the expression of PTGFR and playing a protective role in the CL[42,46]. Thus, the regulation of PG production in the CL may contribute to the activation or amplification of physiological signals in the CL, thereby affecting its fate.

Although the PGF2α pulse induces luteolysis, the combination of the PGF2α pulse and prostaglandin E1 (a subtype of PGE) can rescue luteal function[20], suggesting that PGE antagonizes the luteolytic effect of PGF2α, and PGE may be another important medium promoting the transition from cyclic CL to pregnant CL[47]. PGE2 has been widely recognized as a luteal protective hormone[47], intrauterine infusions of IFNT and PTGES inhibitors can re-establish endometrial PGF2α pulses to induce luteolysis, whereas simultaneous infusions of PGE2 into the ovaries can salvage the CL[22]. Additionally, PGE2 stimulates P4 secretion in the CL of cattle and sheep[48−51]. Studies have shown that IFNT induces PGE2 synthesis by stimulating PTGES expression without affecting PTGFS expression[48−51], thereby enhancing the PGE2/PGF2α ratio to protect the CL[23,52]. In addition, IFNT induces EP2 expression (without affecting the FP)[23,52]. EP2 signaling activates the cAMP/PKA pathway, which regulates the expression of steroid synthase steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR)[53], which further regulates P4 synthesis (Fig. 2). Therefore, the increased EP2 expression enhances the conduction of the P4 synthesis signal. However, EP3, another PGE receptor, mediates the downregulation of cAMP signaling, and its expression in the CL is inhibited by IFNT[23].

In addition to the PG synthesis pathway, genes related to the prostaglandin response and metabolism are regulated by IFNT[54] (Fig. 2). Compared to non-pregnant cattle, PTGFR and its inhibitor, prostaglandin F2 receptor negative regulator (PTGFRN), are negatively regulated in pregnant cattle[54], indicating that IFNT inhibits the PGF2α pathway and prevents CL degeneration stimulated by PGF2α. At the same time, IFNT induces the expression of the PGF2α-degrading enzyme phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH)[54] and promotes the degradation of PGF2α in the CL to reduce the concentration of PGF2α, thereby protecting the CL.

IFNT protects the function of P4 synthesis

-

The main function of CL is to secrete P4, P4 concentration affects the fate of the embryo. In early pregnancy of ruminants, the protective effect of IFNT on the CL is mainly achieved by inhibiting the release of PGF2α pulses, inhibiting apoptosis, and maintaining vascular stability. IFNT indirectly increases the secretion of P4 in vitro by stimulating IL-8 expression and neutrophil migration in the CL but does not directly affect the secretion of P4[55]. During embryo attachment, the plasma P4 concentration was not significantly different between pregnant and non-pregnant animals[56], and the serum P4 concentration was not significantly affected by the intravenous administration of IFNT in the jugular and uterine veins[14,33]. Similarly, no changes in the expression of StAR, 3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc), and peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) were found in the luteal transcriptome during IFNT secretion and non-IFNT secretion[57], which are key enzymes in P4 synthesis. In addition, there was no difference in nuclear receptor subfamily 5 group A member 1/2 (NR5A1/2) expression between pregnant and non-pregnant luteal transcriptomes, transcription factors that control steroid gene expression[57,58], and their expression in vitro was not regulated by IFNT[59]. Surprisingly, the treatment by Bott et al. of the CL with PGF2α for 12 h resulted in decreased mRNA expressions of StAR, PBR, and 3β-HSD regardless of subsequent IFNT treatment. The expressions of StAR and 3β-HSD were also inhibited by IFNT alone[14]. This may be a direct result of the endocrine action of IFNT since IFN-γ, one of a type I IFN, also reduces the activity of STAR and P450scc in various cells[60,61].

Although IFNT could not stimulate further P4 secretion from normal CL, it could salvage (more than twice) the dramatic decrease in P4 concentration induced by PGF2α[33]. Additionally, IFNT inhibited the expression of the vasoconstrictive peptide EDN1 in LCs, luteinized granular cells (LGCs), and luteal endothelial cells (LECs)[38,39,54]. EDN1 is a negative regulator of CL function. EDN1 inhibits the secretion of P4 by LCs through the endothelin type A receptor (ETR-A) and stimulates the secretion of PGF2α, disrupting CL function. The EDN1 signaling pathway is inhibited in the CL of pregnant cattle[54].

Figure 2.

Regulation of prostaglandin synthesis, progesterone synthesis, and apoptosis in the corpus luteum by IFNT. The solid arrows represent promotion, the dotted arrows represent inhibition. Light blue represents the JAK/STAT pathway, orange represents the prostaglandin synthesis and metabolism pathway, pink represents the cell proliferation pathway, green represents the apoptosis pathway, and dark blue represents the progesterone synthesis pathway.

In conclusion, IFNT protects CL function by negatively regulating genes that inhibit P4 synthesis, stabilizing key enzyme expression for P4 production, and maintaining P4 secretion rather than increasing its synthesis. Importantly, other mechanisms may also contribute to the regulation of P4 secretion in luteum cells.

IFNT maintains the vascular stability of CL

-

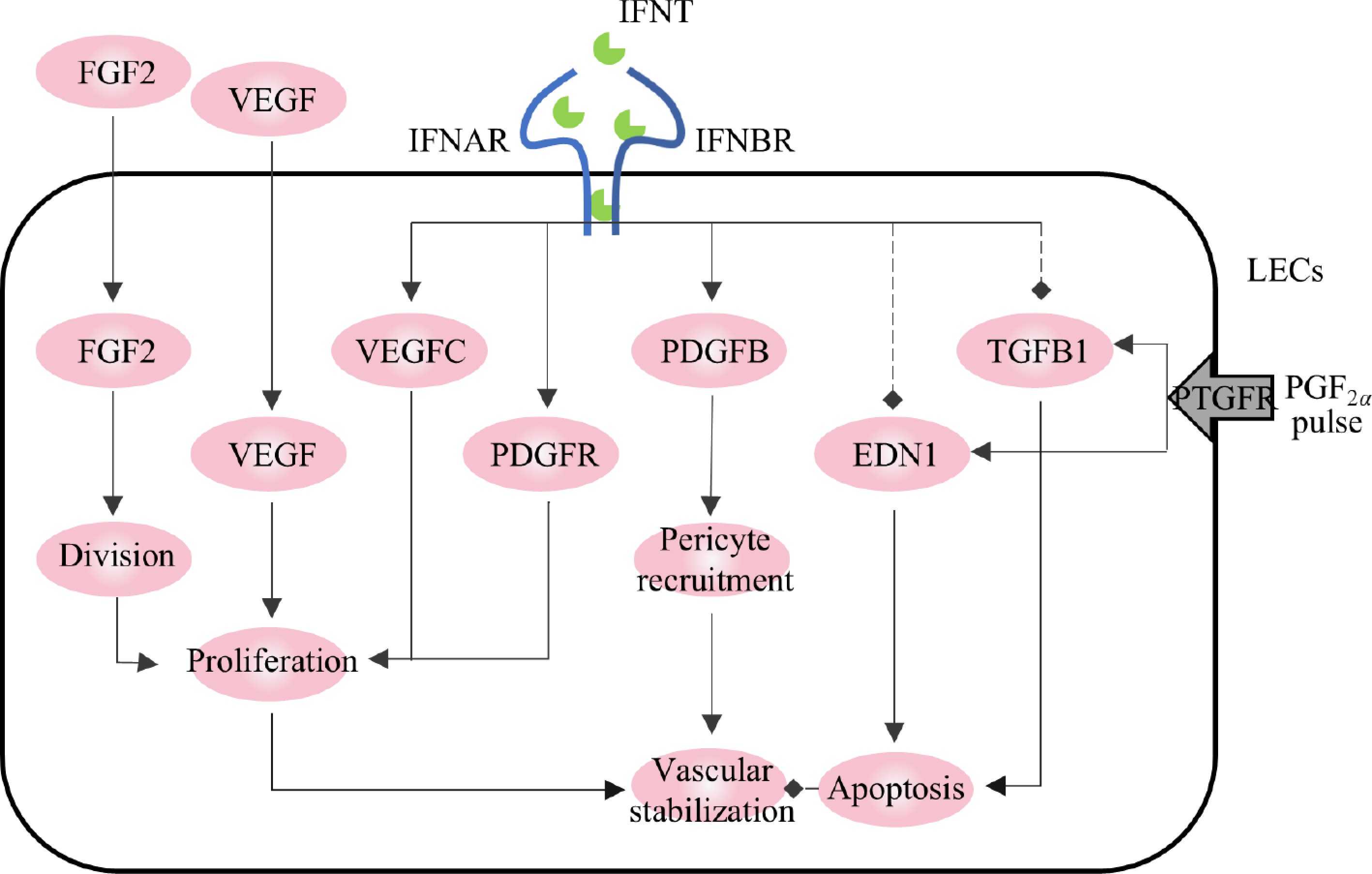

Maintenance of CL function relies on a rich vascular system[62]. IFNT can stabilize the luteal vascular system, facilitating the acquisition of P4 synthetic substrates and P4 transport. The main genes involved in the positive regulation of luteal vascular stability in early pregnancy are VEGF and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), while the main negative regulatory factors are transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGFB1) and EDN1, both of which are regulated to varying degrees by IFNT (Fig. 3).

VEGF and FGF2 are involved in LC proliferation and angiogenesis[63]. VEGF promotes the proliferation, migration, and branching of microvascular endothelial cells and enhances their permeability[64]. FGF2 induces rapid phosphorylation of the proliferation-related signaling pathway (ERK/AKT/STAT1) and is a mitogen in luteal fibroblasts. VEGF and FGF2 expression are activated during luteal formation in pregnancy[65]. During pregnancy in ruminants, IFNT secreted by the conceptus may induce the expression of VEGF and FGF2 to maintain vascular stability and protect the CL[38]. In vitro, IFNT induces the expression of VEGFC and the proliferation of lymphoendothelial cells in lymphocytes and further induces the formation of capillaries[66]. When VEGF and/or FGF2 were blocked with antibodies, the proliferation of endothelial cells was inhibited, the volume of the CL decreased, and P4 decreased. Moreover, FGF2 blocking also increases the ANG2/ANG1 ratio, which disrupts vascular stability[67,68]. TGFB1 and EDN1, critical luteolytic genes, are induced by PGF2α. TGFB1 is involved in the luteal degeneration pathway by promoting apoptosis and destroying capillary morphology[69,70]. IFNT can inhibit the expression of TGFB1 and its receptors, TGFBR1 and TGFBR2, and shut down TGFB1 signal transduction in the CL during pregnancy[39,54]. Consequently, the CL is maintained, and the pregnancy continues. The expression of EDN1 was also inhibited by IFNT[39]. Additionally, IFNT stimulated the expression of other pro-angiogenic genes, such as FGF1, platelet-derived growth factor subunit B (PDGFB), and platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFAR); their expression levels were significantly higher in the CL of cows on the 18th day of pregnancy than in the cyclic CL during the same period[38,57].

In conclusion, IFNT plays a crucial role in regulating vascular stability by universally stimulating or stabilizing the expression of key factors that promote vascular integrity while inhibiting genes associated with vasoconstriction and vascular destruction. This action protects the vascular structure of the CL.

Figure 3.

Regulation of vascular stability in corpus luteum by IFNT. The solid arrows represent promotion, the dotted arrows represent inhibition.

IFNT protects LCs from apoptosis

-

Apoptosis is the main internal mechanism of luteolysis. IFNT has been widely demonstrated to be a survival factor for LCs and LECs, inhibiting apoptotic signals and enhancing the transduction of signaling pathways related to cell survival.

XIAP plays a key anti-apoptotic role by chelating caspase9 and caspase3 to inhibit their activities. On day 18, XIAP expression in the pregnant CL of cattle was significantly higher than that in the non-pregnant CL, which may be the result of the endocrine effect of IFNT occurring on the 18th day of pregnancy. Basavaraja et al. confirmed this finding[38]. Treatment of LCs with IFNT significantly induced protein expression of XIAP, and continuous intravenous injection of 200 μg IFNT on days 7 and 10 of sheep's estrus cycle could significantly induce XIAP expression in CL and prolong the luteal lifespan to more than 32 d[33]. Additionally, IFNT increased the viability of LECs in a STAT-independent manner[39].

Serpin family E member 1 (SERPINE1), thrombospondin 1 (THBS1), THBS2, and TGFB1 are widely studied luteolytic factors. SERPINE1 is a natural proapoptotic gene expressed as PAI-1, which inhibits cell adhesion and angiogenesis[69]. SERPINE1 expression was significantly increased in the CL of cattle treated with PGF2α for 12 h[69,71]. THBS1 and THBS2 are endogenous anti-angiogenic molecules that are widely expressed in degraded CL. Inhibiting the expression of FGF2 and XIAP causes THBS1 and THBS2 to activate the caspase-3 pathway, exerting strong proapoptotic activity[72,73]. A feedforward cycle exists between THBS1, TGFB1, and SERPINE1, whose gene products promote apoptosis and matrix remodeling, ultimately leading to luteolysis[69] (Fig. 2). Therefore, all three are inhibited during MRP. As an MRP signal, IFNT reduces the stimulation of PGF2α on THBS1 and SERPINE1, thereby reversing the negative effects of THBS1, THBS2, SERPINE1, and TGFB1 on LGC activity and reducing the numbers of apoptotic and dead cells[39]. Additionally, IFNT rescues the apoptosis in LGCs mediated by THBS1[38]. These positive effects of IFNT may be achieved by inhibiting the expression of THBS1 and THBS2 and by enhancing the activity of FGF2. Since THBS1 and THBS2 chelate FGF2 to impair its biological activity, inhibiting them may release more biologically active FGF2, thereby increasing overall FGF2 levels[72].

In addition to the above genes, apoptosis-related factors, such as Bcl-2 and pentraxin 3 (PTX3), are also regulated by IFNT (Fig. 2). The Bcl-2 family of proteins is involved in the regulation of various apoptotic pathways. According to a previous report, the expression of the survival genes BCL2L1, Bcl-xL, AKT, MCL1, and PARP in the LC of ewes was upregulated by endocrine delivery of IFNT[33,35], which was inhibited by PGF2α during the luteolytic period. PTX3 is a polysaccharide protein that is highly expressed in the CL during early pregnancy and is negatively correlated with THBS1. Deletion of endogenous PTX3 can lead to cell death. IFNT induces the expression of PTX3 in LGCs, LECs, and luteum sections and upregulates the expression of the anti-apoptotic proteins BIRC5 and survivin, thereby protecting cells from apoptosis[74]. Additionally, IFNT inhibited the expression of PTGFR and histone 2AX (gH2AX), in which gH2AX is a marker of DNA damage that is closely related to apoptosis[75].

In conclusion, the role of IFNT in protecting LCs from apoptosis has been widely validated. However, the underlying mechanism requires further exploration.

IFNT regulates inflammatory response during the formation of pregnant CL

-

Immune cells and cytokines are important regulators of steroid hormone production and vascular function in the CL. When the state of the CL changes, immune cells are recruited to produce and secrete various cytokines that regulate their function and organizational structure[76]. Zhao et al. identified a variety of immune cells in the CL, such as macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils, and indicated that these immune cells accumulate and support angiogenesis and P4 production during CL development[77]. During luteolysis, PGF2α stimulates the production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and accelerates CL decomposition by enhancing the inflammatory response[77]. IFNT can act as an immune modulator during pregnancy and participate in regulating the activation and recruitment of immune cells, thereby calibrating defense, inducing an anti-inflammatory state, preventing autoimmunity, and preventing CL injury[41,78,79].

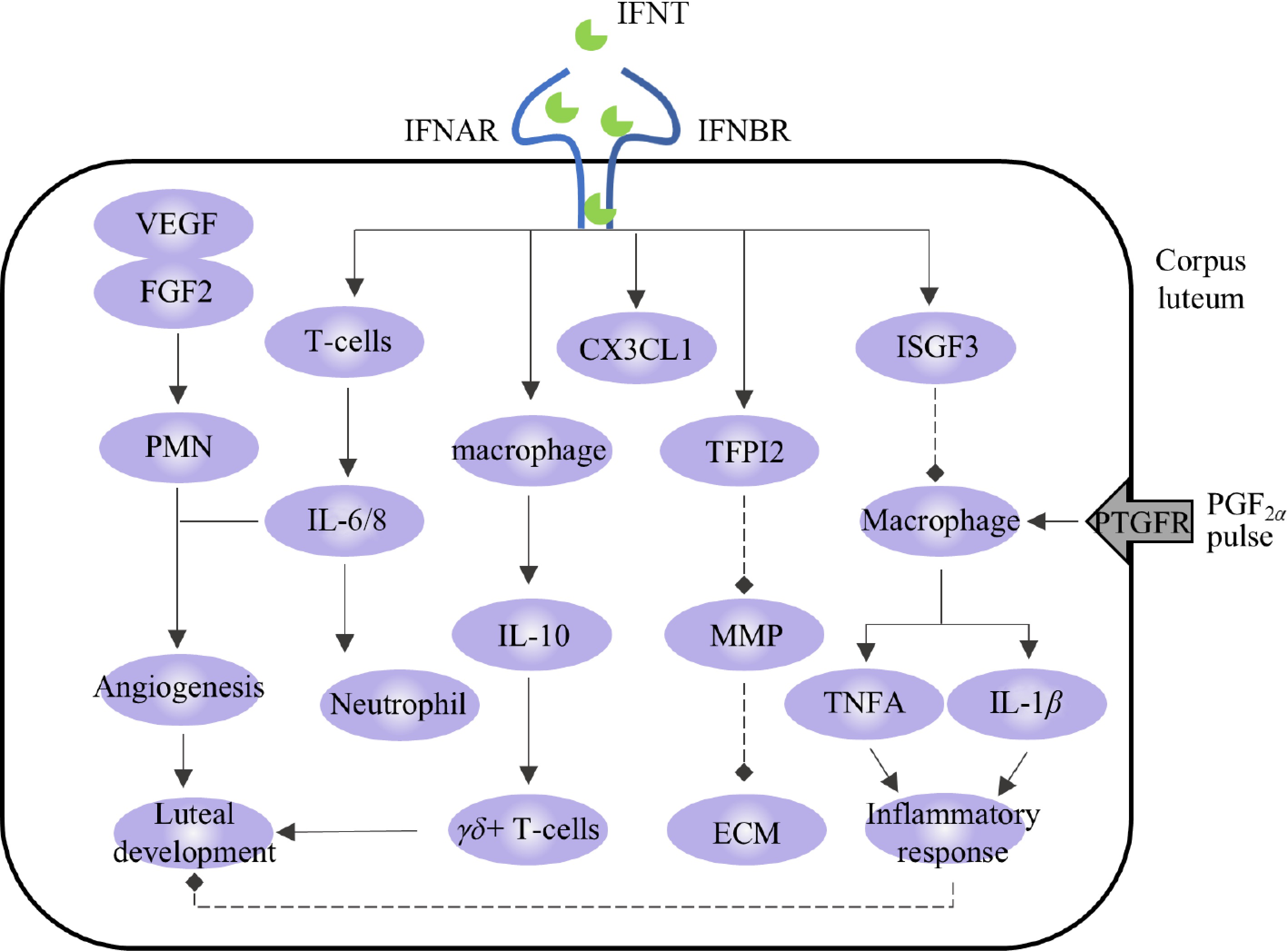

The proliferating T cells in the functional CL are mainly gamma-delta T cells (γδ+ T cells), and the CL exerts an immunosuppressive effect on the proliferation of γδ+ T cells in the CL through the production of IL-10[80]. Studies have shown that the expression level of IL-10 in the transcripts of the uterine flushing fluid of pregnant cattle is upregulated, and IFNT-blocking antibodies inhibit this change[81], indicating that IFNT may induce the expression of IL-10. In addition, the expression of CX3C chemokine ligand 1 (CX3CL1) and TFPI2 is stimulated by IFNT in the CL and is highly expressed in the CL during pregnancy. CX3CL1 acts as an adhesion molecule that regulates the interactions between LCs and immune cells[82]. TFPI2 is an MMP inhibitor that may maintain the stability of the extracellular matrix (ECM) components of the CL by interfering with MMP signaling in pregnant CL[83].

We described how FGF2 and VEGF are induced by IFNT and thus regulate angiogenesis in the CL. Beyond their pro-angiogenic roles, FGF2 and VEGF act as chemoattractants for polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs). In synergy with IL-8, these recruited PMNs further enhance vascular and lymphatic angiogenesis within CL, thereby supporting its structural formation and functional development[84]. PMN also promotes immune transfer and facilitates communication between the CL and other organs. During early pregnancy in cattle, IFNT regulates the reconstruction of the luteal lymphatic system via the VEGFC/VEGFD-VEGFR3 system[66] and enhances neutrophil function and numbers in the CL by promoting IL-6 and IL-8 secretion[85]. This upregulation of IL-8 and neutrophils by IFNT contributes to sustained P4 production during MRP[55] (Fig. 4).

In addition, IFNT regulates the state of immune cells and the secretion of cytokines. Macrophages are necessary for maintaining luteal function; however, they are also recruited in large numbers during the early stages of luteolysis[86]. In addition to macrophages, immune cells that are highly recruited during luteolysis include CD4+ and CD8+ T cells[87]. PGF2α stimulates the proliferation of these immune cells, while P4 inhibits them[88]. The secreted inflammatory factors (tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFA), IL-1β, and IFN-γ) and chemokines (CCL2) from these cells contribute to luteolysis[89]. Upon the initiation of luteolysis, there is further recruitment of macrophages and T lymphocytes. Macrophages secrete TNFA and other pro-inflammatory cytokines to promote inflammation and immune reactions, thereby enhancing the luteolysis cascade. TNFA is a pro-inflammatory factor secreted mainly by macrophages and strongly expressed during luteolysis[90,91]. IFNT inhibits the activation of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages in vitro by controlling the activation of the ISGF3 complex and STAT3 pathway. It also inhibits the secretion of TNFA, thus playing a role in inhibiting inflammation[53,92], which is consistent with the downregulation of the TNFA enrichment pathway in the CL of pregnant cattle[54]. IL-1β is a classical proinflammatory factor. When the CL is stimulated by the PGF2α pulse or its function is inhibited by other pathways, the expression level of IL-1β increases[93,94], while IFNT can downregulate the secretion of IL-1β and inhibit the inflammatory response[52,95] (Fig. 4). Beyond the factors described above, the expressions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), and arginase 1 (ARG1), which are involved in the regulation of inflammatory responses, were also regulated by IFNT to varying degrees[85,96].

-

In summary, we have comprehensively elucidated the intrinsic mechanisms by which IFNT regulates the formation of the pregnant CL through modulation of apoptosis, immune responses, vascular stabilization, and other key processes. This study establishes a theoretical foundation for fully unraveling the mechanisms underlying CL formation in ruminants and improving their pregnancy rates. Future research should focus on further investigating IFNT-mediated regulatory mechanisms while developing targeted pharmaceuticals or therapeutic strategies to safeguard CL formation, thereby enhancing reproductive efficiency and economic outcomes.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: manuscript conception: Shang C, Liu H; manuscript edition: Shang C, Liu H, Li Z; manuscript revision: Lin P, Jin Y, Wang A; figure preparation: Zhang R, Niu H, Liu S, Mou Y. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This study received no external fundings. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for the English language editing.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Shang C, Liu H, Zhang R, Li Z, Niu H, et al. 2025. New insights into interferon-τ mediated luteal regulation during ruminant pregnancy. Animal Advances 2: e029 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0025

New insights into interferon-τ mediated luteal regulation during ruminant pregnancy

- Received: 11 February 2025

- Revised: 07 April 2025

- Accepted: 28 May 2025

- Published online: 24 October 2025

Abstract: Main pregnancy failures in ruminants arise from two causes: failure of the embryon to attach, and early or late abortions, which are due to failure of the corpus luteum and luteal phase deficiency. Interferon-τ is a type I interferon mainly produced by the trophectoderm of ruminants, which acts on all body tissues and organs by paracrine and endocrine actions during embryo attachment as a pregnancy recognition signal. Among them, interferon-τ inhibits the pulse release of prostaglandin F2α in the endometrium through paracrine action, avoids luteolysis, protects luteal formation in pregnancy, and enables pregnancy to continue. Recent studies have shown that interferon-τ extends luteal lifespan through endocrine action; however, the specific mechanism is unclear. In this review, we provide new insights into a series of interferon-τ-regulated physiological changes that occur during the formation of the pregnant corpus luteum, covering its functional, structural, and immunological features.

-

Key words:

- Interferon-τ /

- Corpus luteum /

- Ruminant reproduction /

- Pregnancy maintenance