-

The increasing discharge of organic wastewater from expanding industrial activities, particularly in textile dyeing and printing, has become a major environmental concern. Globally, the annual production of synthetic dyes exceeds 700,000 tons, involving over 100,000 different commercial varieties[1]. Inadequate wastewater treatment facilities allow approximately 10% of these dyes to enter aquatic ecosystems, where their high solubility and structural stability contribute to their remarkable environmental persistence[2]. These compounds resist natural degradation and challenge conventional treatment methods, creating long-term contamination issues[3]. Even at minimal concentrations (1 mg L−1), dyes cause visible water discoloration while simultaneously suppressing phytoplankton photosynthesis and reducing dissolved oxygen levels, effects particularly evident in triphenylmethane and azo dyes. Furthermore, bioaccumulation of carcinogenic metabolites such as aromatic amines from azo dye breakdown can induce hepatic injury, gastrointestinal complications, and neurodevelopmental impairments[4,5]. Consequently, regulatory frameworks such as the EU Water Framework Directive have established stringent discharge limits, requiring dye concentrations to remain below 0.05 mg L−1[6]. Among common dye pollutants, methylene blue (MB, C16H18ClN3S), a heterocyclic aromatic compound, finds extensive application in chemical indicators, textile manufacturing, biological staining, and pharmaceutical products[7], necessitating efficient treatment solutions for MB-contaminated wastewater. Current remediation technologies include adsorption[8], membrane filtration[9], electrochemical treatment[10], chemical oxidation[11], and biological degradation[12]. Notably, adsorption has gained particular prominence due to its cost efficiency, operational simplicity, high removal capacity, and minimal risk of secondary pollution.

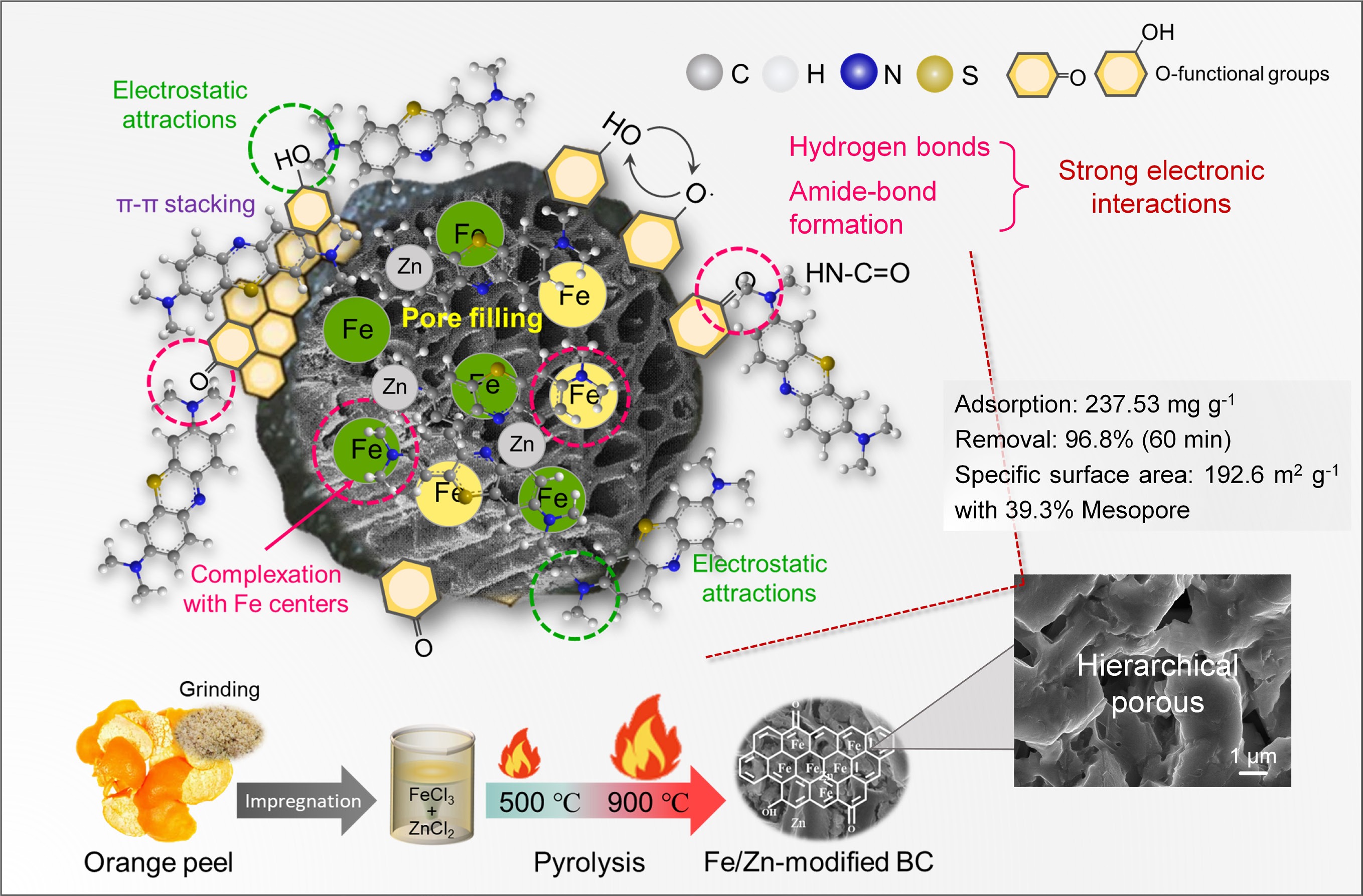

The conversion of biomass waste into biochar represents a promising strategy for sustainable wastewater treatment[13]; however, the practical implementation of unmodified biochar faces significant limitations, including solid-liquid separation challenges, and constrained adsorption capacity[14]. To address these constraints, iron impregnation has emerged as an effective modification approach that significantly enhances removal performance for diverse contaminants, particularly synthetic dyes[15,16]. Typical synthesis involves impregnating biomass precursors with iron salts such as FeCl3, followed by pyrolysis under an inert atmosphere, simultaneously carbonizing the biomass and generating iron oxide nanoparticles through in-situ crystallization. The introduced iron species act as efficient porogens, working synergistically with chemical activators to construct hierarchical porous structures, thereby significantly enhancing the specific surface area[17−19]. The composite surface is further modified with iron oxides and oxygen-containing functional groups that provide active sites for contaminant binding. For cationic dyes like methylene blue, adsorption involves multiple complementary processes: pore filling within the developed porosity, electrostatic attraction between negatively charged surface sites and dye cations, surface complexation at iron active centers, and π-π interactions with the carbon matrix[20,21]. The integration of high surface area with multifunctional surface chemistry renders iron-loaded biochar both efficient and practical for dye wastewater remediation. Future research should prioritize developing regeneration protocols that minimize secondary pollution, alongside designing novel biomass-derived materials with enhanced reusability[22].

China maintains a prominent position in global citrus production, with annual harvests exceeding 45 million tons. During processing, approximately 40%–50% of the total fruit mass, consisting mainly of peel, is generated as agricultural residue[23]. Current disposal methods such as landfilling and uncontrolled incineration not only represent inefficient resource utilization but also contribute to secondary pollution. Orange peel exhibits a characteristic lignocellulosic profile comprising 15–20 wt% cellulose, 10–15 wt% lignin, and 10–15 wt% hemicellulose, alongside substantial volatile content[24]. This composition confers a natural porous framework and abundant surface functional groups, rendering the material particularly suitable as a precursor for engineered biochar production[25]. Thermal treatment at 400–600 °C transforms this biomass into biochar possessing developed porosity, oxygen-rich functional groups, and inherent alkaline mineral content, which collectively facilitate synergistic adsorption mechanisms[26]. Nevertheless, existing research has primarily focused on conventional pyrolysis conditions and fundamental activation parameters, overlooking the strategic integration of pore structure with impregnation activation to enhance adsorptive functionality[27]. While ZnCl2 activation significantly enhances the specific surface area and porosity of biochar, and FeCl3 modification introduces iron-based active sites and improves surface affinity, single-modification strategies often struggle to simultaneously optimize pore structure and surface reactivity. Materials derived from ZnCl2 activation may exhibit limited chemisorption capacity due to their chemically inert surfaces, whereas Fe-modified biochars can suffer from metal aggregation or underdeveloped porosity, which compromises mass transfer efficiency and site accessibility. This research gap highlights the critical need to synergistically engineer both pore architecture and surface chemistry to advance the practical application of biochar in treating dye-contaminated wastewater.

This study aimed to develop functional biochar from orange peel through pyrolysis under a nitrogen atmosphere for sustainable waste valorization. A dual-modification strategy was employed by co-impregnating the biomass with ZnCl2 as a chemical activator and FeCl3 as both an iron source and a graphitization catalyst, thus creating a hierarchically porous composite, leveraging the pore-forming effect and surface modification for integrated control of porosity and active sites. During carbonization, iron species facilitated graphitic ordering while ZnCl2 activation generated well-developed porosity, resulting in the creation of adsorbents with a combination of high capacity, rapid kinetics, and good regenerability. Methylene blue (MB), a representative aromatic dye prevalent in industrial effluents, was selected as the target pollutant to evaluate adsorption performance. The investigation systematically examined key parameters, including solution pH, initial dye concentration, contact time, and coexisting ions, for their effects on MB removal efficiency. Material characterization utilized scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and Raman spectroscopy. Adsorption mechanisms were further elucidated by fitting experimental data to established isotherm and kinetic models. This work provides valuable insights into high-value utilization of citrus waste while advancing functional biochar applications in organic wastewater treatment.

-

First, the collected fresh orange peels were thoroughly washed with deionized water to remove surface impurities. The cleaned peels were cut into 1–2 cm fragments, and dried in a forced-air drying oven at 80 °C. Subsequently, the dried material was ground using a mechanical grinder and sieved through a 100-mesh sieve to obtain uniformly pretreated powder. A predetermined amount of the pretreated orange peel powder was placed in a quartz boat and subjected to carbonization in a tube furnace under a nitrogen atmosphere at 500 or 900 °C for 4 h, with a heating rate of 5 °C min−1, followed by an isothermal hold at the target temperature for 1 h. After natural cooling to room temperature, the resulting product was ground and sieved to yield orange peel biochar, designated as OPBC500 and OPBC900, respectively.

The orange peel powder (50 g L−1) was mixed with a 3 mol L−1 aqueous solution of anhydrous FeCl3 (corresponding to 486.6 g L−1), supplemented with ZnCl2 (20 g L−1) in a predetermined ratio, and then stirred continuously on a magnetic stirrer at 80 °C for 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting slurry was dried in an oven to obtain solid particles. These particles were ground and loaded into a quartz boat, which was subsequently placed in a tube furnace. Under a continuous nitrogen atmosphere, the samples were carbonized at either 500/900 °C (heating rate: 5 °C min−1) for 4 h, followed by isothermal holding at the target temperature for 1 h. After carbonization, the samples were allowed to cool naturally to room temperature, then ground and sieved to yield iron-loaded orange peel biochar, designated as Fe/Zn-OPBC500 and Fe/Zn-OPBC900, respectively.

Characterization of OPBCs

-

The chemical functional groups of the synthesized biochar samples were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (Bruker VECTOR-22). Morphological characteristics were examined using field emission scanning electron microscopy (HITACHI SU4800) and transmission electron microscopy (FEI TF20). Crystalline structures were determined through X-ray diffraction (Rigaku D/max2200PC) with data processed in JADE 6.5. Textural properties, including specific surface area and pore size distribution, were analyzed via N2 physisorption at 77 K (Micromeritics ASAP 2460). The point of zero charge was determined via zeta potential measurements across pH 1–10 (Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS). The surface elemental composition and chemical states were characterized by XPS using a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha instrument, with spectral data calibrated to the C 1s peak, at a binding energy of 284.8 eV.

Adsorption experiments

Adsorption efficiency experiments

-

All experiments were conducted at 25 °C using a 40 mg L−1 MB solution with 10 mg of adsorbent in a 10 mL volume, shaken at 180 rpm. The study evaluated several parameters affecting adsorption efficiency, including adsorbent dosage (0.05–0.5 g L−1). Solution pH was adjusted using 0.1 M HCl or 0.1 M NaOH, and ionic strength was assessed with NaCl, CaCl2, FeCl3, NH4HCO3, and KH2PO4. After filtration through a 0.22 μm membrane, residual MB concentrations were measured by UV-Vis spectrophotometry at λmax = 664 nm.

The adsorption capacity was calculated as:

$ {{Q}}_{{e}}=\dfrac{\left({{C}}_{{0}}-{{C}}_{{e}}\right){V}}{{m}} $ (1) where, V (L) denotes the total volume of the solution; C0 and Cₑ (mg L−1) represent the initial and equilibrium concentrations of MB, respectively; and m (g) refers to the mass of OPBC employed.

Adsorption isotherm experiments

-

A quantity of 10 mg of OPBCs was introduced into 50 mL glass conical flasks, each containing 10 mL of MB solutions with concentrations ranging from 10–100 mg L−1, and the mixtures were incubated for 24 h under specific pH conditions (acidic at pH = 3, alkaline at pH = 11). The residual concentration of MB was measured at predetermined time intervals to monitor the adsorption kinetics. The kinetic data were fitted to both the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models according to the following equations:

$ \ln \left({q}_{e}-{q}_{t}\right)=\ln{q}_{e}-{k}_{1}t $ (2) $ \dfrac{t}{{q}_{t}}=\dfrac{1}{{k}_{2}q_{e}^{2}}+\dfrac{t}{{q}_{e}} $ (3) where, k1, k2, and k3 are the rate constants of the pseudo-first-order model, the pseudo-second-order model, and the intraparticle diffusion model, respectively.

Furthermore, the adsorption isotherms were analyzed using the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin models, and the corresponding equations are presented as follows:

$ {{Q}}_{{e}}=\dfrac{{{Q}}_{{m}}{{K}}_{{L}}{{C}}_{{e}}}{{1}+{{bc}}_{{e}}} $ (4) $ {{Q}}_{{e}}={{K}}_{{F}}{C}_{{e}}^{{1/{{n}}}} $ (5) $ {Q}_{e}=\frac{RT\ln({K}_{T}{C}_{e})}{\beta } $ (6) where, Qm (mg g−1) is the maximum adsorption capacity of OPBCs, KL (L mg−1) is the Langmuir constant indicating binding site affinity and adsorption free energy, KF (L mg−1) reflects adsorption capacity, and n is the heterogeneity factor indicating adsorption intensity.

-

The yield of biochar obtained from orange peel (OPBC) exhibited significant stability and low mass loss during the carbonization process, which can be attributed to the combined effect of ZnCl2 activation and the intrinsic structural properties of the raw material. Under optimized preparation conditions, the coordinated modification strategy effectively preserved the carbon framework integrity while simultaneously developing hierarchical porosity. With increasing ZnCl2 impregnation ratios, the OPBC yield progressively decreased from 36.42 wt% to 28.76 wt%, reflecting the dual functionality of ZnCl2 as both a dehydrating agent and a structural template during pyrolysis. The loadings of Fe and Zn are now provided (Table 1), which reveals a temperature-dependent retention pattern. Due to the low initial content of ZnCl2 (in a 3 mol L−1 aqueous solution of anhydrous FeCl3, equivalent to 486.6 g L−1, with ZnCl2 (20 g L−1) supplemented in a predetermined ratio) and its volatility at high temperatures, Fe was effectively retained (e.g., approximately 7.8 at% at 500 °C, as determined by XPS analysis). In contrast, Zn underwent significant volatilization (Table 1), commencing from 500 °C (approximately 3.2 at% as determined by XPS analysis), and dropping to 0.8% at 900 °C. This clarifies their distinct roles as a stable active site and a volatile pore-former. This systematic mass reduction originated from three concurrent physicochemical processes: (1) ZnCl2-induced dehydration promoting cross-linking reactions that enhance carbon matrix stability; (2) molten salt etching generating hierarchical pore structures through controlled carbon consumption; and (3) accelerated decomposition of biomass components (cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin), enhancing volatile release. Furthermore, FeCl3 incorporation contributed to additional mass reduction through its catalytic effect on graphitization while introducing iron-based functionality to the composite material[27].

Table 1. Specific surface areas, distributions of pore volumes and specific atomic percentage of Fe/Zn-OPBC

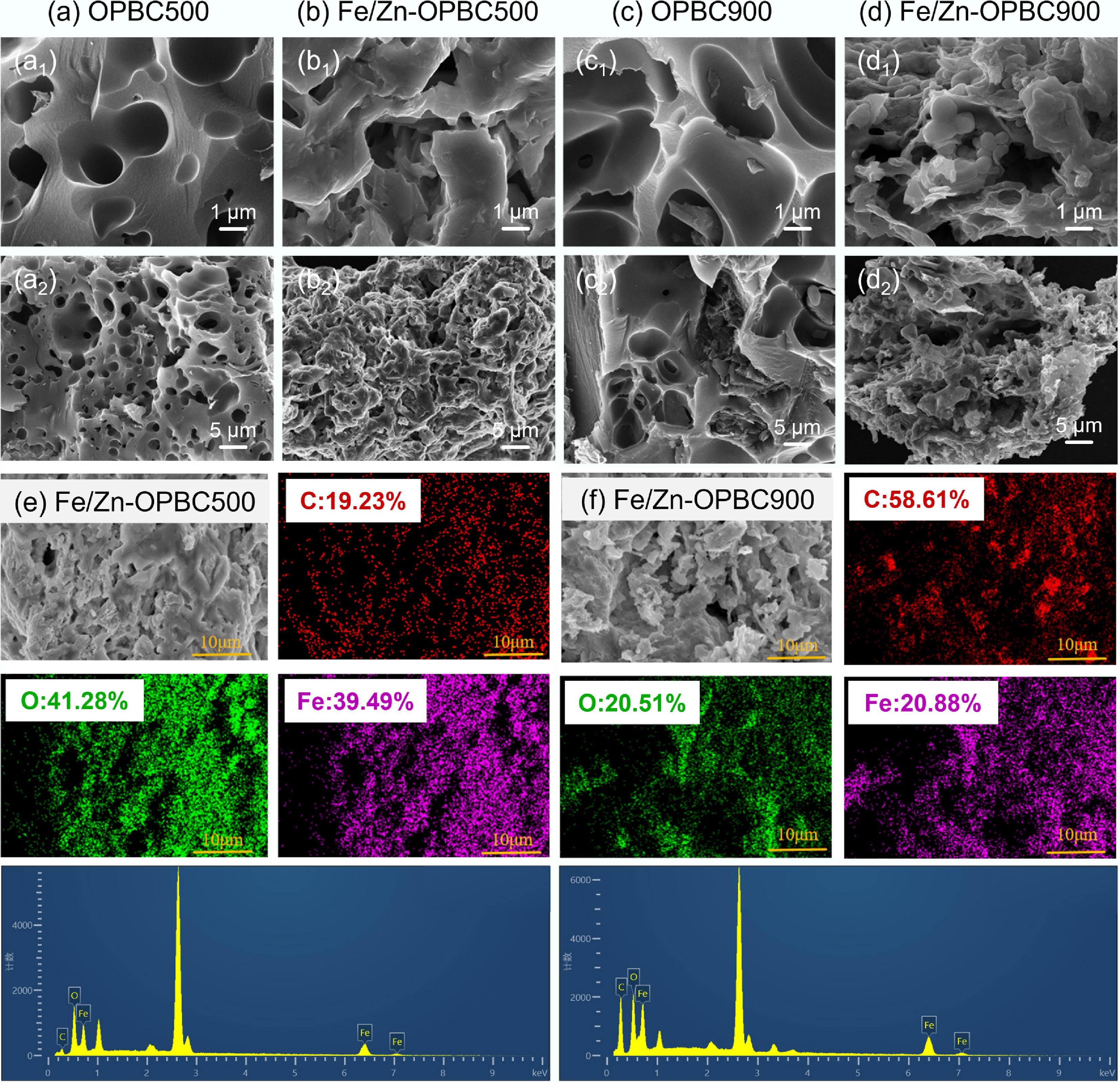

Sample N2 physisorption C/O ratio Atomic percentage SBETa (m2 g–1) Vtotalb (cm3 g–1) Mesoporec (%) Micropored (%) C (%) O (%) Fe (%) Zn (%) Fe/Zn-OPBC500 192.6 0.104 39.3 60.7 1.92 57.3 31.7 7.8 3.2 Fe/Zn-OPBC900 367.5 0.245 26.2 74.8 4.10 76.7 18.4 4.1 0.8 OPBC500 12.03 0.018 90.8 9.2 5.76 85.2 14.8 / / OPBC900 44.9 0.082 46.3 53.7 16.5 94.3 5.7 / / a Calculated via the BET method based on adsorption data within the p/p0 range of 0.05 to 0.30. b Total pore volume measured at a relative pressure (p/p0) of 0.99. c Proportion of pore volume attributed to mesopores. d The proportion of pore volume associated with micropores. Micropores are defined as pores with diameters less than 2 nm, whereas mesopores refer to those ranging from 2 to 50 nm. Multi-scale SEM imaging combined with elemental mapping analysis (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1) provides a comprehensive understanding of the microstructural changes in biochar. Unmodified orange peel biochar (OPBC) displays a relatively smooth surface morphology characterized by large cavity-like pores with limited microporous development (Fig. 1a, c). Following ZnCl2 activation and FeCl3 modification, substantial structural reconstruction occurs, resulting in an open-cell three-dimensional architecture[28] with uniformly distributed iron oxide nanoparticles anchored within the carbon matrix (Fig. 1b, d). High-resolution SEM imaging confirms the formation of well-defined hierarchical pores spanning micrometer to nanometer dimensions, substantially increasing both specific surface area and total pore volume. Comprehensive elemental mapping analysis (Fig. 1e, f) demonstrates homogeneous distribution of iron species throughout the carbon matrix, verifying successful metallic incorporation during the modification process. This strategically engineered microstructure, characterized by its optimized porosity and surface chemistry, establishes an advanced platform for efficient contaminant adsorption while maintaining excellent structural stability for practical environmental applications.

Figure 1.

SEM images of the samples at various magnifications: (a) OPBC500, (b) Fe/Zn-OPBC500, (c) OPBC900, and (d) Fe/Zn-OPBC900. Elemental mapping and compositional analysis for (e) Fe/Zn-OPBC500, and (f) Fe/Zn-OPBC900 are also presented.

Physical structure

-

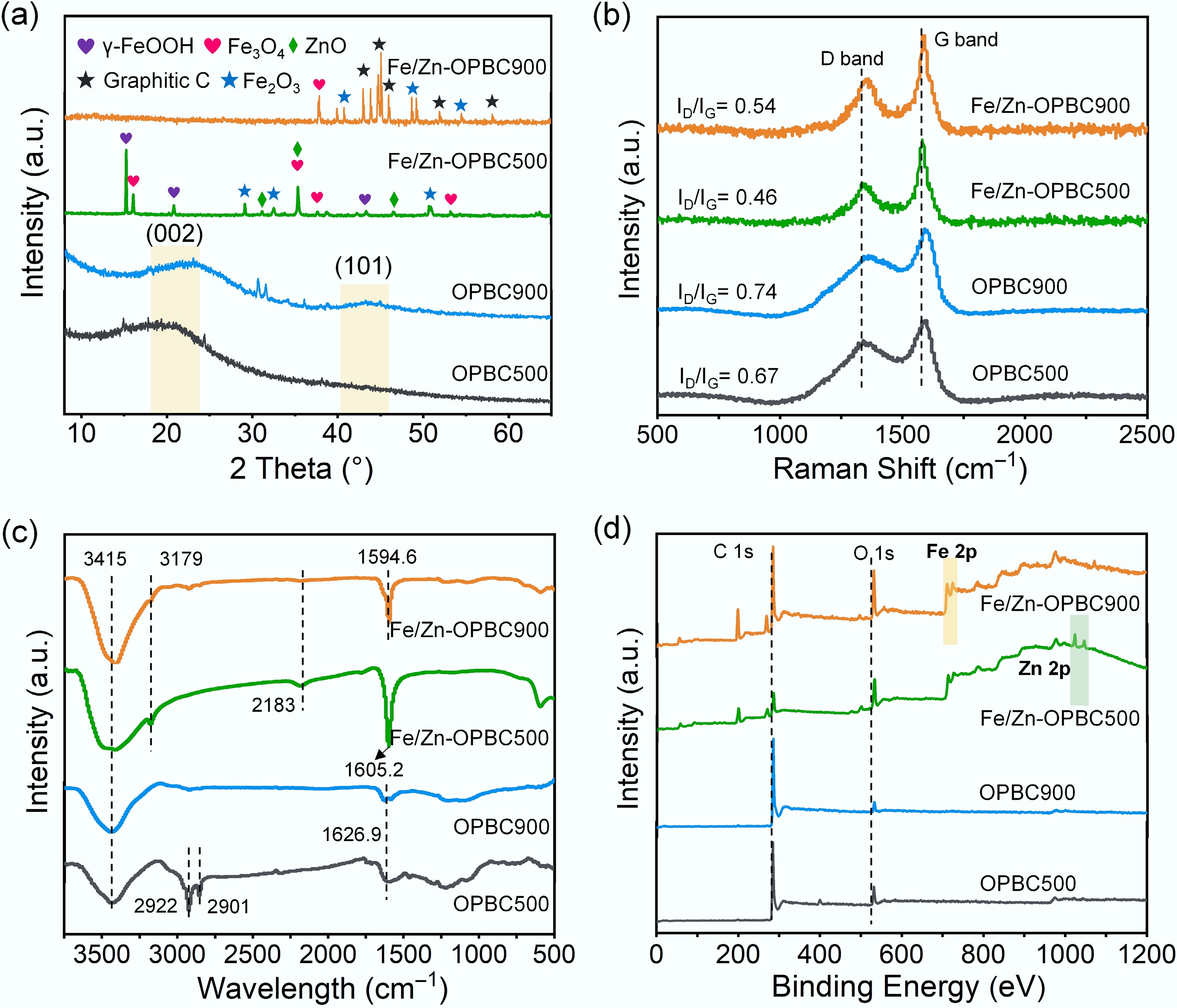

The crystalline phases of the synthesized biochar materials were analyzed using X-ray diffraction, and the resulting patterns are comparatively displayed in Fig. 2a. All samples display two distinct diffraction peaks: a broad, asymmetric peak centered at 2θ = 23.2°, which is attributed to the (002) plane of graphitic carbon regions[29,30], and a less intense peak at 2θ = 43.6°, associated with the (101) plane of sp3-hybridized carbon frameworks[31]. This spectral profile indicates the coexistence of ordered and disordered carbon structures, which is characteristic of lignocellulosic-derived BC. Notably, distinct differences between the Fe/Zn-OPBC500 and Fe/Zn-OPBC900 spectra reveal a temperature-dependent iron-carbon evolution mechanism. In Fe/Zn-OPBC500, preserved multiphase iron species (Fe3O4, γ-FeOOH, α-Fe2O3) act as structural modifiers that disrupt graphitic ordering while introducing structural defects and oxygen-containing functional groups. In contrast, Fe/Zn-OPBC900 undergoes phase purification through the volatilization of unstable iron compounds, with residual Fe3O4 and α-Fe2O3 particles catalyzing the growth of graphitic domains via dissolution-precipitation mechanisms. This iron-carbon interaction accounts for the enhanced surface reactivity of Fe/Zn-OPBC500, which arises from iron-induced structural disorder, while Fe/Zn-OPBC900 exhibits more ordered yet chemically inert carbon matrices.

Figure 2.

(a) XRD patterns, (b) Raman spectra, (c) FTIR spectra, and (d) XPS spectra of various OPBCs.

Raman spectroscopy was employed to investigate the structural characteristics and defect evolution of the carbon matrices (Fig. 2b). All samples exhibited distinct D (~1,350 cm−1, A1g), and G (~1,590 cm−1, E2g) bands[32], corresponding to disordered carbon and in-plane vibrations of sp2-hybridized carbon, respectively. The intensity ratio (ID/IG) indicated significant modulation of structural defects by iron incorporation and pyrolysis temperature. Fe/Zn-OPBC500 showed the lowest ID/IG (0.46), while Fe/Zn-OPBC900 exhibited a higher value (0.54), reflecting an increased defect density[33]. This contrast reveals distinct structural evolution pathways: at 500 °C, well-dispersed iron nanoparticles promote graphitic ordering while retaining moderate defects; at 900 °C, iron volatilization and particle aggregation induce extensive disorder despite limited graphitization. These Raman results align with XRD and SEM data, confirming a coherent structure–property relationship governed by iron–carbon interactions. Consequently, Fe/Zn-OPBC500 features an optimized architecture with balanced graphitic domains and hierarchical porosity, providing abundant active sites and leading to superior methylene blue adsorption. This well-balanced structure highlights the importance of synchronizing crystallinity and defect engineering in designing advanced biochar materials.

Surface property and porous structure

-

The surface chemical properties of the prepared biochars were characterized by FTIR spectroscopy (Fig. 2c and Table 1), which indicated notable changes in functional groups following iron modification. Both pristine and iron-modified samples exhibited a broad absorption band near ~3,415 cm−1, indicating O–H stretching vibrations from hydroxyl groups and adsorbed water. The increased intensities of oxygen-containing functional groups in Fe/Zn-OPBC suggest extensive surface complexation between iron nanoparticles and oxygenated moieties, demonstrating that iron functionalization effectively engineered the biochar surface chemistry with an optimized distribution of functional groups. The FTIR spectrum of unmodified OPBC500 showed distinct aliphatic C–H stretching vibrations at 2,922 and 2,901 cm−1. Following iron modification, several notable changes emerged: new peaks appeared at 3,179 and 2,183 cm−1, attributable to strongly hydrogen-bonded hydroxyl groups and C≡N stretching vibrations, respectively; the absorption intensity in the range of 1,594.6–1,605.2 cm−1, corresponding to C=C skeletal vibrations, significantly increased; and a clear peak at 622 cm−1 was observed, assigned to Fe–O stretching vibrations, providing direct evidence of successful iron incorporation. Additional characteristic bands were consistently detected across all samples at approximately 1,705 cm−1 (C=O stretching), 1,420 cm−1 (C–H bending), and 1,075 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching).

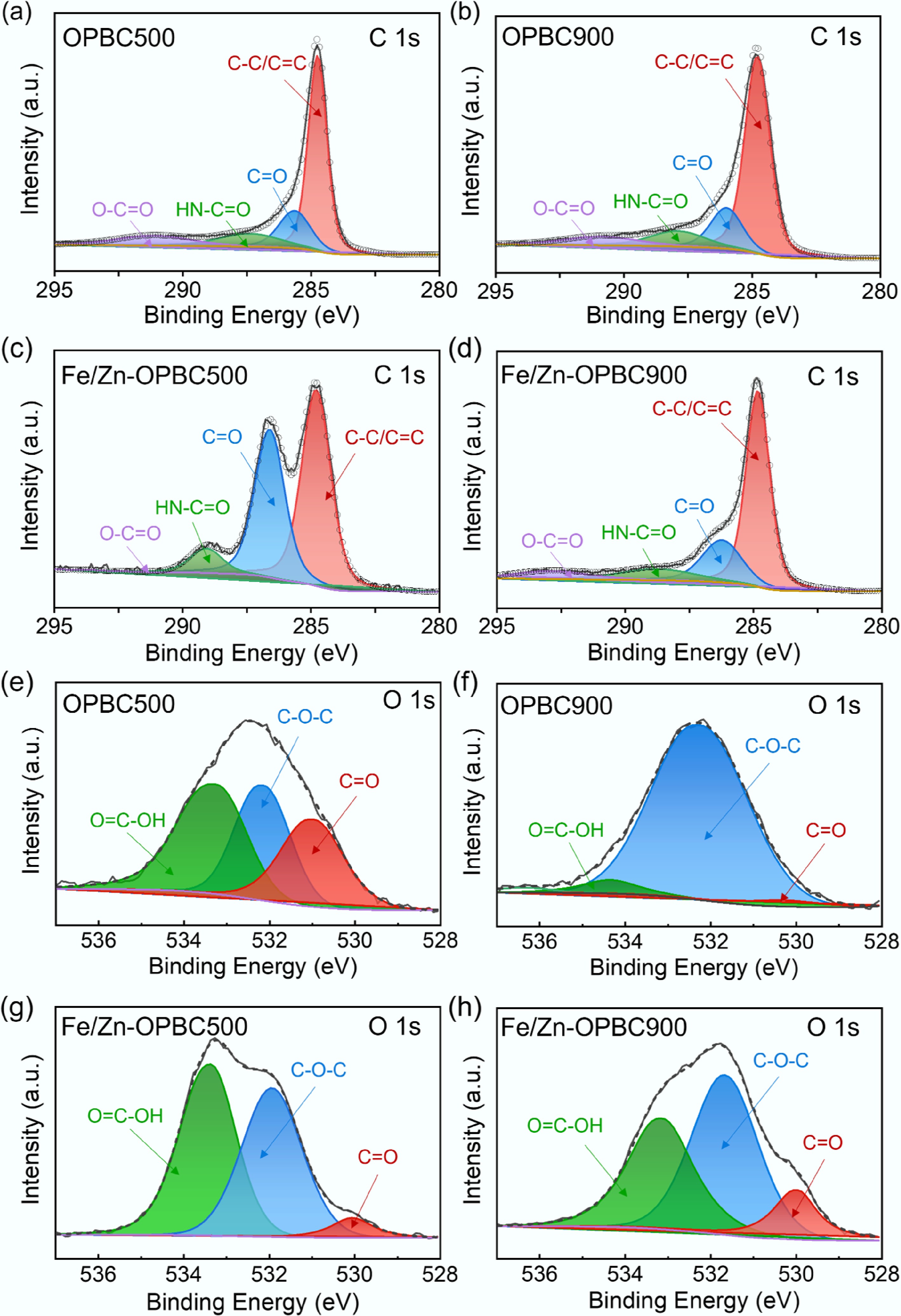

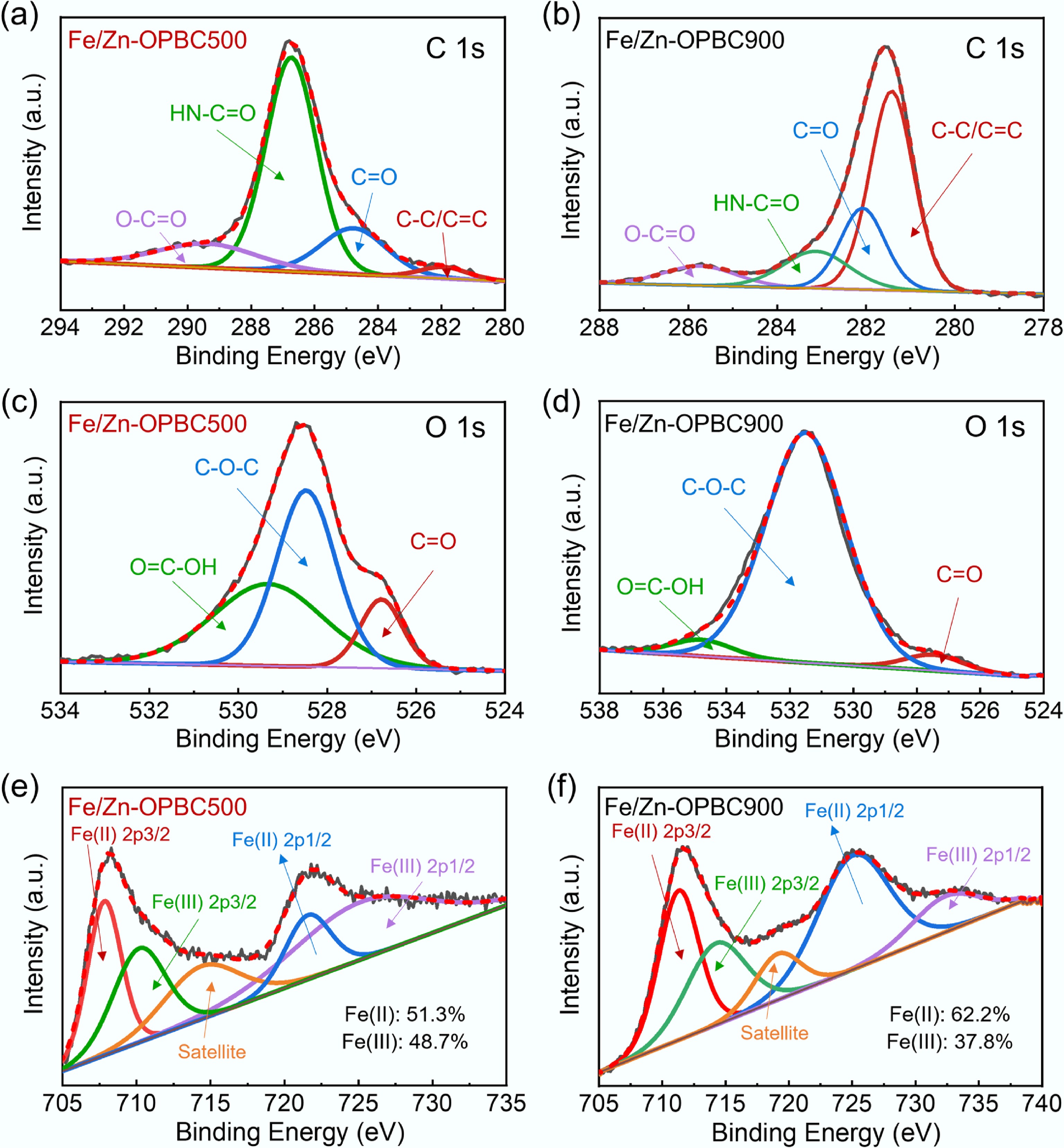

XPS analysis was employed to systematically investigate the elemental composition and surface chemical characteristics of the synthesized biochar (Fig. 2d). Survey spectra confirmed the presence of characteristic C 1s (284 eV), and O 1s (532 eV) signals in all samples, while iron-modified biochars exhibited distinct Fe 2p3/2 and Fe 2p1/2 peaks at 711 and 725 eV, respectively, confirming successful incorporation of iron. High-resolution spectral analysis provided detailed insights into the chemical bonding environment. The C 1s spectrum of Fe/Zn-OPBC500 was fitted with four distinct peaks: a major peak at 284.8 eV attributed to graphitic carbon (C–C/C=C), along with three oxygen-functionalized species observed at 287.1 eV (corresponding to amide or carbamate groups, HN–C=O), 289.5 eV (assigned to protonated carboxyl moieties, –COOH), and a small peak at 283.6 eV, which may arise from contaminant carbon or structural defects[34]. Notably, Fe/Zn-OPBC500 exhibited a significantly higher proportion of C=O groups compared to other samples (Fig. 3a−d). Consistently, the O 1s spectrum revealed three characteristic peaks corresponding to 530.5 eV (C=O in ketonic/quinone groups), 532.4 eV (ether linkages, C–O–C), and 535.2 eV (–COOH), with Fe/Zn-OPBC500 demonstrating a markedly enhanced contribution from C=O species (Fig. 3e−h). The consistent increase in carbonyl and carboxyl groups in both C 1s and O 1s spectra (Table 2), along with higher oxygen content in low-temperature OPBC, shows a clear link between moderate pyrolysis and preserved oxygen-rich surface chemistry. In addition, Fe/Zn-OPBC500 exhibited a weak yet detectable Zn 2p signal (Supplementary Fig. S2). The high-resolution spectrum disclosed oxidized Zn species, such as ZnO or ZnClxOy complexes, which is consistent with its role as a Lewis acid in the activation process. In contrast, this signal was significantly diminished in Fe/Zn-OPBC900 (Fig. 2d). Collectively, these results suggest that 500 °C optimally balances iron incorporation and the retention of reactive oxygen functional groups.

Table 2. Specific distributions of C 1s and O 1s bonding states of OPBCs

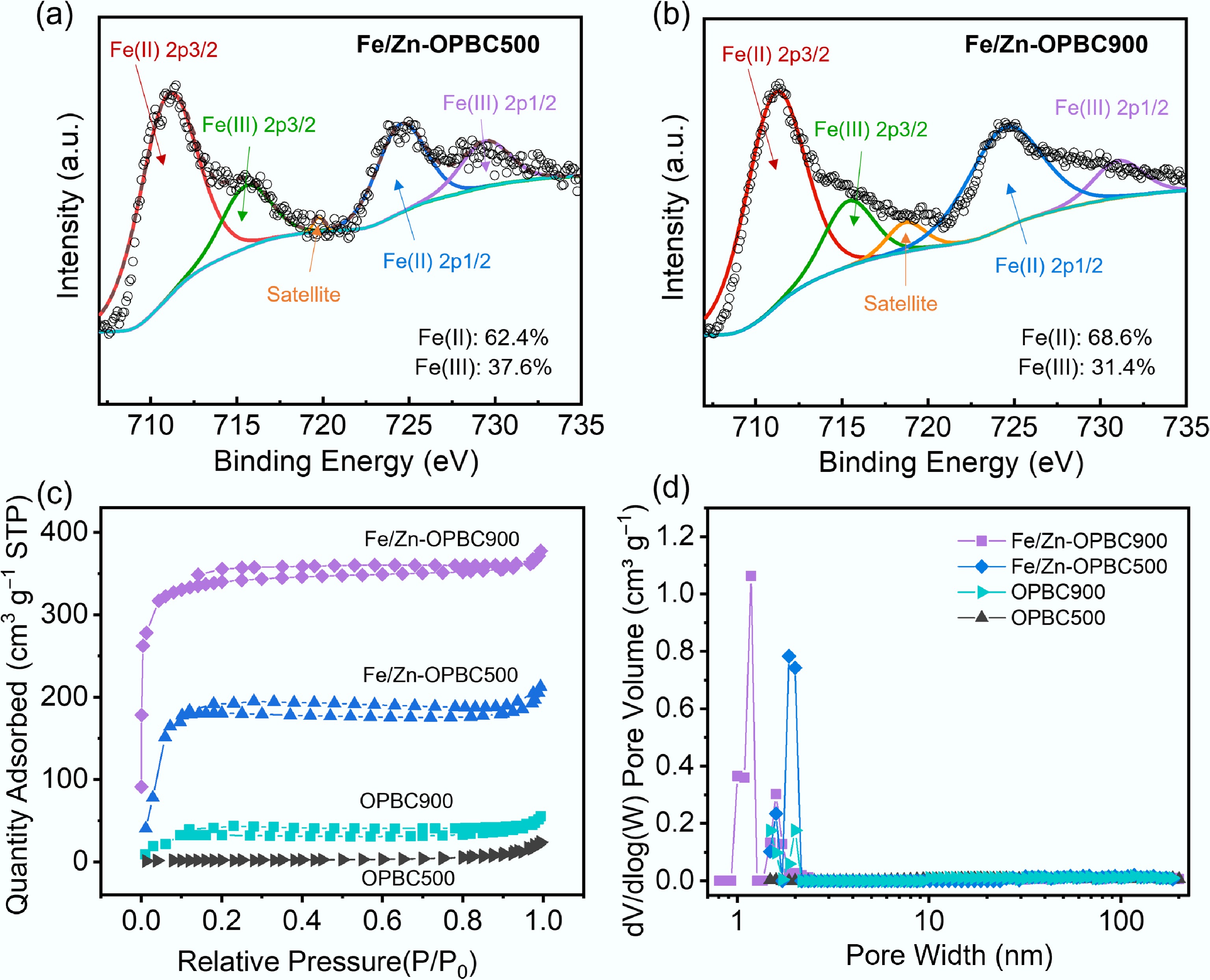

Sample Percentage of area C–C/C=C (%) C=O (%) HN–C=O (%) O–C=O (%) O=C–OH (%) C–O–C (%) C=O (%) Fe/Zn-OPBC500 40.8 37.5 18.3 3.4 42.9 45.7 11.4 Fe/Zn-OPBC900 43.6 31.4 15.5 9.5 38.5 44.9 16.6 OPBC500 40.9 27.3 16.6 15.2 36.2 30.7 33.1 OPBC900 48.7 28.6 13.8 8.9 6.8 90.6 2.6 XPS analysis confirmed iron incorporation into modified OPBCs, with Fe/Zn-OPBC500 showing higher iron content (Table 1). The high-resolution Fe 2p spectrum (Fig. 4a, b) revealed both Fe(III) (711.2, 724.8 eV) and Fe(II) (710.2, 723.6 eV), indicating the presence of Fe3O4 and γ-FeOOH/α-Fe2O3. Deconvolution of Fe 2p peaks showed an increase in Fe(II) fraction from 62.1% in Fe/Zn-OPBC900 to 68.6% in Fe/Zn-OPBC500, reflecting temperature-dependent iron speciation. These results offer valuable insights into thecoordination structure of iron species, and their interaction with the carbon matrix. Temperature-controlled synthesis allows tuning of biochar surface properties: Fe/Zn-OPBC500, prepared at 500 °C, retains abundant oxygen-containing groups (C=O, –COOH), leading to lower pKa and more negative zeta potential[35], enhancing electrostatic attraction to cationic MB. In contrast, Fe/Zn-OPBC900 exhibits decomposed functional groups and increased graphitization, resulting in chemically inert surfaces. The optimized surface of Fe/Zn-OPBC500 enables synergistic adsorption, iron oxides act as Lewis acid sites for dye nitrogen coordination, oxygen groups facilitate hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, and graphitic domains support π–π stacking[36,37].

Figure 4.

High-resolution XPS spectra of Fe 2p for (a) Fe/Zn-OPBC500 and (b) Fe/Zn-OPBC900. (c) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms. (d) Corresponding pore size distribution curves.

In addition, the porous structure of the synthesized OPBCs was analyzed through N2 physisorption measurements at 77 K (Fig. 4c). Each sample exhibited a Type-IV isotherm accompanied by an H4 hysteresis loop, which suggests the presence of well-defined mesoporous architectures. Pore size distributions from QSDFT analysis (Fig. 4d) revealed hierarchical networks of mesopores (2–50 nm) and micropores (< 2 nm). Co-modification improved textural properties, with temperature-dependent effects: Fe/Zn-OPBC900 exhibited higher microporosity and surface area (367.5 m2 g−1), while Fe/Zn-OPBC500 developed more mesopores. This structural evolution shifted capillary condensation to higher relative pressures (P/P0 = 0.7–0.9), and increased mesopore sizes from 3.5–28.6 to 5.8–35.2 nm. Compared to pristine biochar, both modified samples showed large improvements, 16.1-fold and 5.7-fold increases in surface area and pore volume (Table 1), highlighting the effectiveness of dual-metal modification in optimizing porous architecture for enhanced adsorption.

Collectively, integrated characterization through SEM, XRD, XPS, and N2 physisorption demonstrates that ZnCl2/FeCl3 co-modification effectively regulates both iron functionalization and hierarchical porosity development in orange peel-derived biochar[38]. During pyrolysis under a nitrogen atmosphere, the dual modifiers undergo synergistic transformations where ZnCl2 serves as a chemical activator creating hierarchical pores through dehydration and template mechanisms, while FeCl3 decomposes to form iron oxide species while simultaneously catalyzing carbon graphitization. This coordinated modification strategy establishes an optimal balance between iron-mediated active sites and porous architecture, enabling precise control over surface functionality and textural properties[39,40]. The resulting Fe/Zn-OPBC materials exhibit tunable surface chemistry combining iron-oxygen groups with oxygen-containing functionalities, along with well-developed micro-mesoporous networks that collectively enhance methylene blue adsorption performance. The complementary characterization techniques provide comprehensive evidence that the engineered surface chemistry and optimized pore structure work synergistically to create highly efficient adsorbents for wastewater treatment applications.

Adsorption properties

-

Batch experiments were conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of both unmodified and modified OPBC in removing MB from aqueous solutions. Among the samples, Fe/Zn-OPBC exhibited excellent adsorption performance and was therefore selected for detailed investigation of MB adsorption kinetics, isotherms, and thermodynamics.

Effect of OPBC type and dosage

-

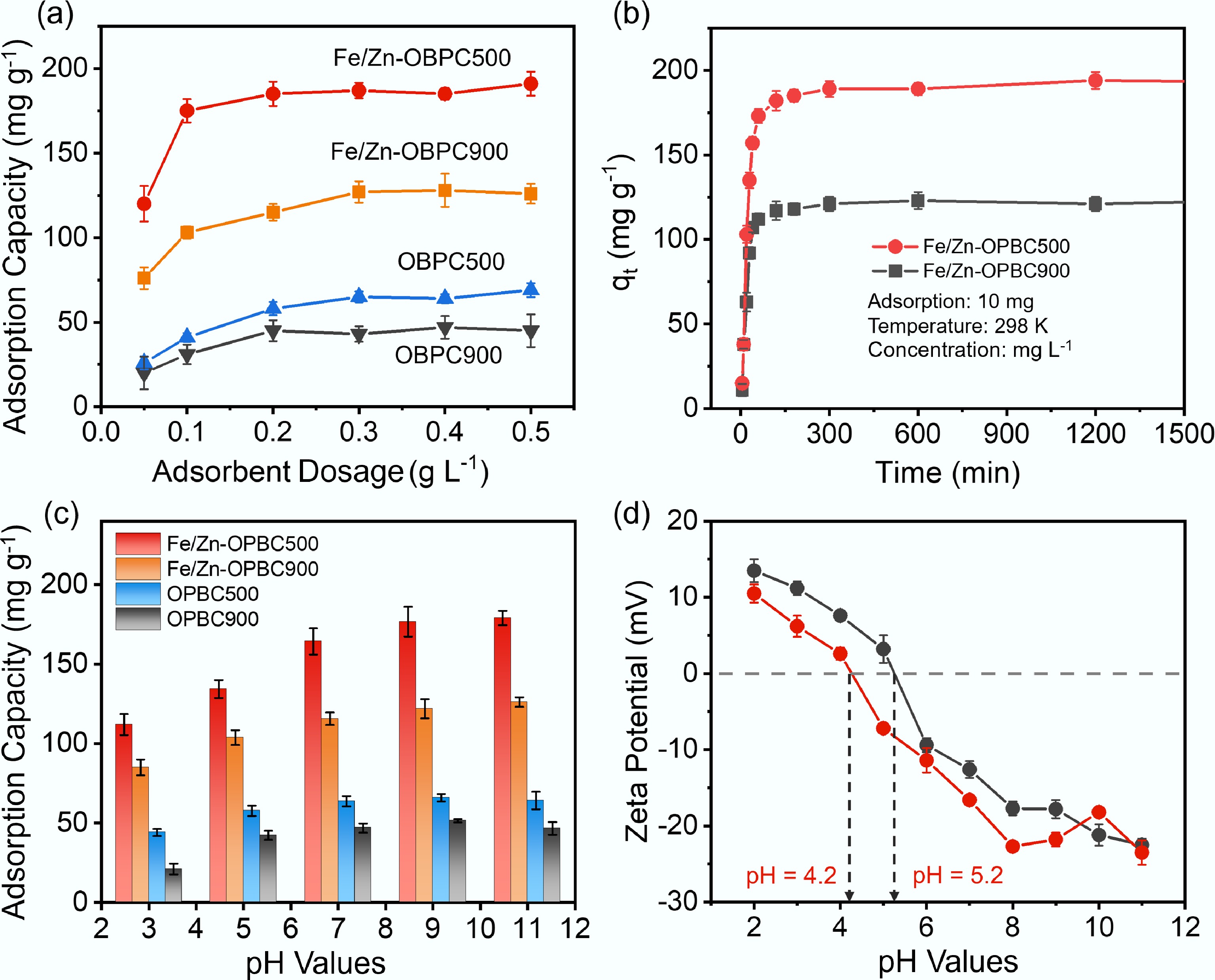

Initial tests under standardized conditions showed that adsorbent dosage critically influences MB removal. As shown in Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. S3, both pristine and iron-modified OPBCs achieve higher MB removal with increasing dosage, but adsorption capacity per unit mass decreases accordingly. The optimal balance between removal efficiency and material utilization is achieved at approximately 0.1 g L−1, where iron modification markedly enhances performance. While pristine OPBC exhibits an adsorption capacity of 26.8–28.1 mg g−1, Fe/Zn-OPBC500 reaches 194.5 mg g−1, significantly surpassing the 128.7 mg g−1 observed for Fe/Zn-OPBC900. This improved performance is primarily attributed to the optimized hierarchical porosity, enhanced surface functionalization, and a more balanced graphitic structure resulting from iron incorporation, along with abundant surface active sites, all of which synergistically facilitate mass transfer and enhance molecular accessibility. Notably, Fe/Zn-OPBC500 achieves rapid MB removal under mild conditions (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. S4), attaining a 96.8% elimination rate within 60 min. When the dosage is increased to 0.2 g L−1, complete removal (~100%) is achieved within 30 min. Based on the obtained results, Fe/Zn-OPBC500 with a concentration of 0.1 g L−1 was chosen for in-depth analysis of adsorption isotherms, kinetic behavior, thermodynamic parameters, and the mechanisms involved.

Figure 5.

(a) Effect of adsorbent dosage on adsorption capacity of MB; (b) Effect of reaction time; (c) Effect of pH on MB adsorption capacity; (d) Zeta potentials of Fe/Zn-OPBCs at different pH. Adsorption conditions: C0 = 40 mg L−1, V = 10 mL, pH = 7, and T = 298 K.

Effect of pH

-

The surface charge characteristics of Fe/Zn-OPBCs exhibit strong pH dependence, which fundamentally governs their methylene blue (MB) adsorption behavior. Potentiometric titration revealed points of zero charge (pHpzc) at pH 4.2 for Fe/Zn-OPBC500, and pH 5.2 for Fe/Zn-OPBC900 (Fig. 5d), reflecting distinct surface chemistries resulting from differences in iron speciation and the distribution of functional groups. A systematic evaluation conducted over the pH range of 3 to 11 revealed that the adsorption capacity of both materials for MB markedly increases as the pH rises from 3 to 7, after which the uptake remains nearly constant under alkaline conditions (Fig. 5c). The superior performance of Fe/Zn-OPBC500 over the entire pH range can be attributed to its higher content of oxygen-containing functional groups and iron oxyhydroxide species, which deprotonate at neutral and alkaline pH to generate negatively charged surface sites (e.g., –COO−, –O−, Fe–O−) that strongly attract cationic MB molecules. The lower pHpzc of Fe/Zn-OPBC500 indicates increased surface acidity and an earlier shift to a negatively charged surface, thereby enhancing electrostatic attraction. These results demonstrate that electrostatic interactions are the primary mechanism governing MB adsorption, with optimized surface chemistry contributing to superior adsorption capacity over a broad pH range.

Effect of reaction time and adsorption kinetics

-

Figure 5b illustrates the adsorption kinetics of MB on Fe/Zn-OPBC500 at a concentration of 40 mg L−1, revealing a two-stage process: an initial rapid uptake followed by a gradual approach to equilibrium. This kinetic profile can be attributed to the hierarchical pore structure and abundant surface functional groups of the material, which offer numerous active sites and promote efficient mass transfer. The initial rapid phase involves mesopore adsorption and iron-site complexation, while the subsequent slower phase includes micropore diffusion and interactions with oxygen-containing groups.

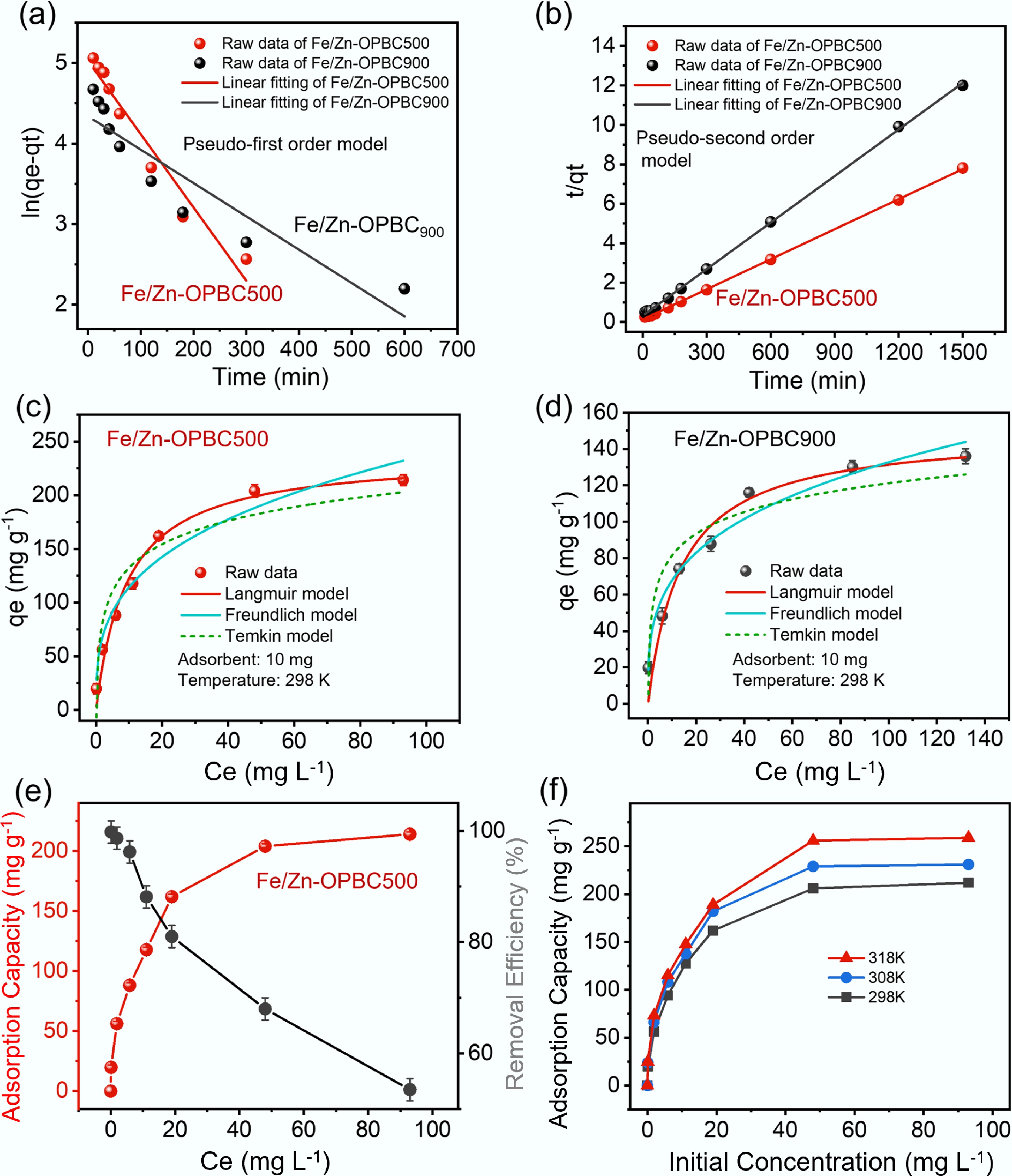

Further, the adsorption kinetics were investigated using the pseudo-first-order (P-fo), and pseudo-second-order (P-so) models (Fig. 6a, b and Table 3). The P-so model describes chemisorption governed by chemical reaction rates, while the P-fo model represents physisorption controlled by adsorbent surface properties[37]. For Fe/Zn-OPBC500, kinetic analysis demonstrates a superior fit with the P-so model (R2 = 0.9995) compared to the P-fo model (R2 = 0.9487), indicating that chemisorption is the dominant mechanism in the rate-controlling step, driven by coordination interactions between MB molecules and iron active sites, as well as electron transfer promoted by oxygen-containing functional groups. The short equilibrium time reflects exceptional adsorption kinetics, though steric hindrance may occur post-equilibrium as hydrated MB molecules compete for remaining sites. With rapid kinetics and high capacity (194.5 mg g−1), this orange peel-derived biochar shows great promise for practical wastewater treatment. These findings provide crucial insights for designing advanced biomass-derived adsorbents with optimized iron-carbon architectures.

Figure 6.

Kinetic and isotherm modeling of methylene blue adsorption using Fe/Zn-OPBCs. (a) Pseudo-first-order linear fitting, (b) pseudo-second-order linear fitting, and nonlinear isotherm models for adsorption on (c) Fe/Zn-OPBC500, and (d) Fe/Zn-OPBC900; (e) Effect of initial methylene blue concentration on removal efficiency using Fe/Zn-OPBC500; (f) Temperature dependence of methylene blue adsorption.

Table 3. The parameters of the P-fo and P-so kinetic models

Kinetic model Parameter Value Fe/Zn-OPBC900 Fe/Zn-OPBC500 P-fo qe 76.566 152.37 k1 –0.004 –0.009 R2 0.84616 0.94875 P-so qe 127.23 196.85 k2 0.005 0.008 R2 0.99097 0.9995 Effect of temperature and the adsorption isotherm

-

Isotherm modeling (Table 4) offered fundamental insights into the adsorption mechanism: the Langmuir model (R2 = 0.974) indicated monolayer adsorption on homogeneous surfaces, the Freundlich model (R2 = 0.951) suggested multilayer adsorption on heterogeneous sites, and the Temkin model revealed uniformly distributed binding energies with a decrease in adsorption heat[41,42]. The mass transfer is governed by the gradient in chemical potential existing between the adsorbent surface and the bulk solution, which is evidenced by the adsorption behavior dependent on concentration as illustrated in Fig. 6c, d. Fe/Zn-OPBC500 exhibits high adsorption efficiency, reaching over 82% of its maximum capacity within 60 min at concentrations below 40 mg L−1 (Fig. 6e), which can be attributed to the abundance of active sites and steep concentration gradients. However, once this threshold concentration is exceeded, adsorption approaches saturation, as indicated by only an 8.2% increase in uptake despite a fivefold rise in concentration, reflecting the progressive occupation of available adsorption sites and a corresponding reduction in the driving force for adsorption. This concentration-dependent trend is characteristic of Langmuir-type monolayer adsorption, consistent with a homogeneous distribution of active sites resulting from ZnCl2 activation and iron modification, thereby supporting the dominance of chemisorption via coordination mechanisms.

Table 4. The fitting parameters of isotherm models

Model Parameter Value Fe/Zn-OPBC900 Fe/Zn-OPBC500 Langmuir qm (mg g−1) 149.5790 237.53 KL (L g−1) 0.07229 0.1069 R2 0.9499 0.9738 Freundlich KF (mg g−1 (L mg−1)1/n) 34.6367 55.0039 1/n 0.2916 0.3176 R2 0.9631 0.9514 Temkin β 17.2570 31.5193 KT (L g−1) 11.2210 6.6814 R2 0.8545 0.8873 The adsorption capacity of Fe/Zn-OPBC500 exhibits significant temperature dependence (Fig. 6f), reaching a maximum methylene blue uptake of 263.9 mg g−1 at 318 K, with a moderate enhancement rate (Δqe/ΔT = 1.32 mg g−1 K−1) (Supplementary Table S1). The excellent fit to the Langmuir model (R2 = 0.987) suggests monolayer adsorption on energetically uniform surfaces, corroborated by favorable separation factors (KL = 0.152) and moderate surface heterogeneity (1/n = 0.347). Thermodynamically, the negative ΔG° values (–2.38 to –1.96 kJ mol−1 across 298–318 K) confirm a spontaneous adsorption process. The positive ΔH° (4.31 kJ mol−1) indicates an endothermic nature, while the positive ΔS° (0.021 kJ mol−1 K−1) reflects an increase in randomness at the solid–liquid interface. The rising adsorption capacity with temperature is attributed to the thermal activation of latent adsorption sites and enhanced molecular mobility.

Effect of ionic strength and regeneration property

-

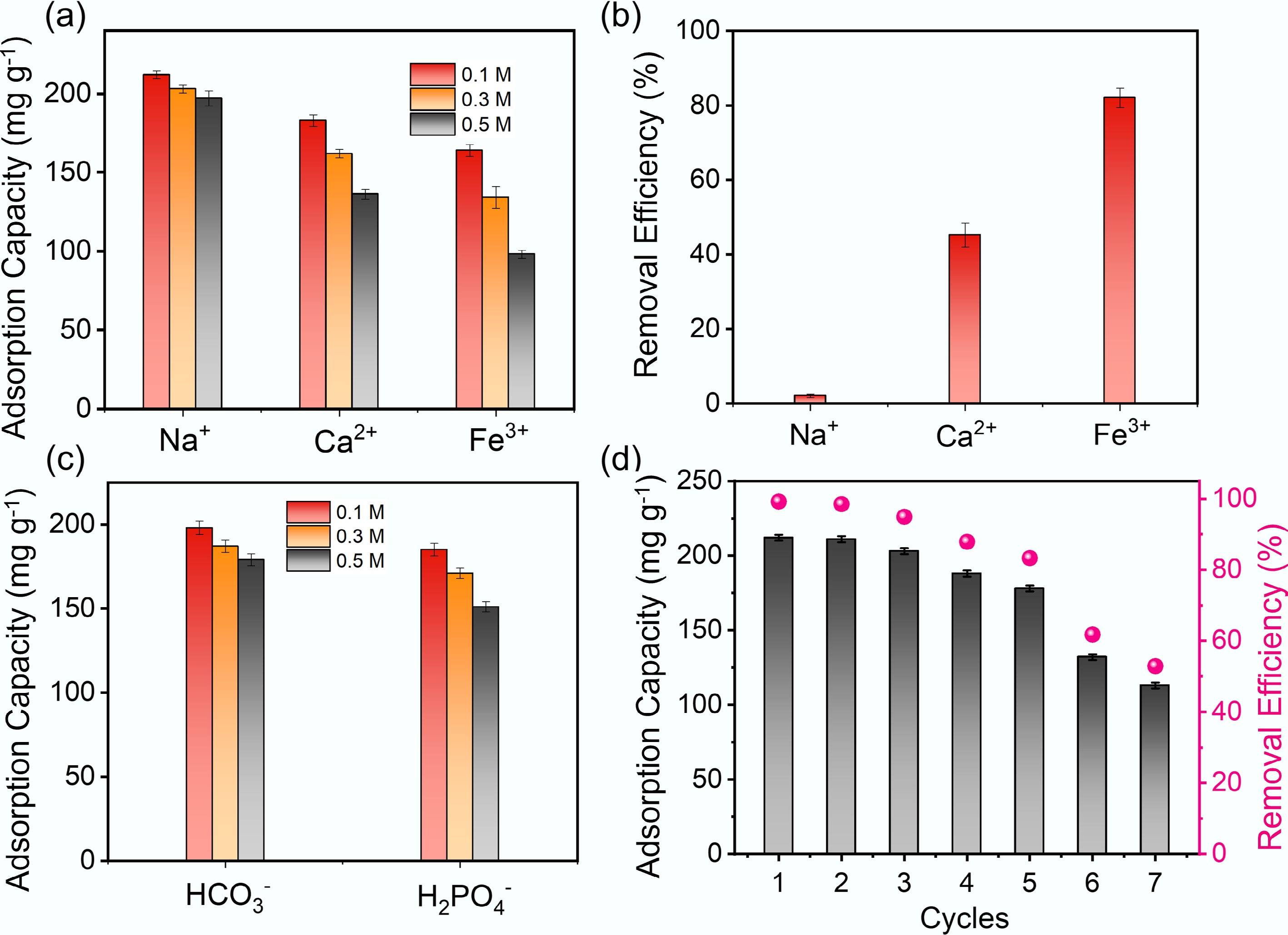

Competitive adsorption studies in complex aqueous environments reveal distinct ion-specific effects on MB removal by Fe/Zn-OPBC500. In the ionic strength range of 0.1–0.5 M (equivalent to NaCl), monovalent Na+ ions have minimal impact on adsorption, while multivalent cations such as Ca2+ and Fe3+ markedly decrease the adsorption capacity (Fig. 7a). A systematic evaluation reveals a valence-dependent affinity sequence: Fe3+ > Ca2+ >> Na+ (< 5%) (Fig. 7b), which aligns with Eisenman's selectivity principles. This trend arises from preferential ion exchange between multivalent cations, characterized by smaller hydration radii (Ca2+: 0.412 nm; Fe3+: 0.337 nm), and the negatively charged surface functional groups (e.g., carboxyl and iron–oxygen complexes) of the biochar, in contrast to the strongly hydrated Na+ (hydration radius: 0.358 nm).

Figure 7.

(a) Effect of cation concentration on the adsorption equilibrium of MB by Fe/Zn-OPBC500. (b) Adsorption behavior of cations with different valences. (c) Influence of anion concentration on adsorption performance. (d) Reusability of Fe/Zn-OPBC500 for MB removal.

Notably, co-existing anions exert considerably weaker influences due to electrostatic repulsion from the negatively charged biochar surface under operational pH conditions. Specifically, HCO3− exerts a mild promotional effect by buffering the solution pH, thereby enhancing surface deprotonation, whereas H2PO4− causes moderate inhibition (15%–40% reduction in adsorption capacity) owing to its strong specific adsorption onto iron active sites (Fig. 7c). The significantly reduced interference from anions, compared to multivalent cations, mainly arises from their limited competition with MB for identical adsorption sites, in addition to prevailing electrostatic repulsion. These results underscore the high selectivity of Fe/Zn-OPBC500 in complex ionic environments, affirming its promise for practical wastewater treatment applications.

Regeneration experiments provide valuable insights into the adsorption mechanism and practical applicability of Fe/Zn-OPBC500. While common eluents such as ethanol and 0.1 M NaOH achieved minimal desorption of MB, 0.1 M HCl effectively disrupted both cation-π interactions and coordination bonds at the iron active sites. The material demonstrates exceptional cycling stability, retaining above 100 mg g–1 over seven regeneration cycles (Fig. 7d), attributable to irreversible occupation of only a small fraction of high-affinity sites. Fe/Zn-OPBC500 preserves operational effectiveness under ambient conditions without energy-intensive reactivation. The pH-responsive regeneration behavior, combined with inherent material stability and minimal secondary contamination risk, establishes Fe/Zn-OPBC500 as a sustainable and economically viable adsorbent for practical wastewater treatment applications.

Adsorption mechanism analysis

-

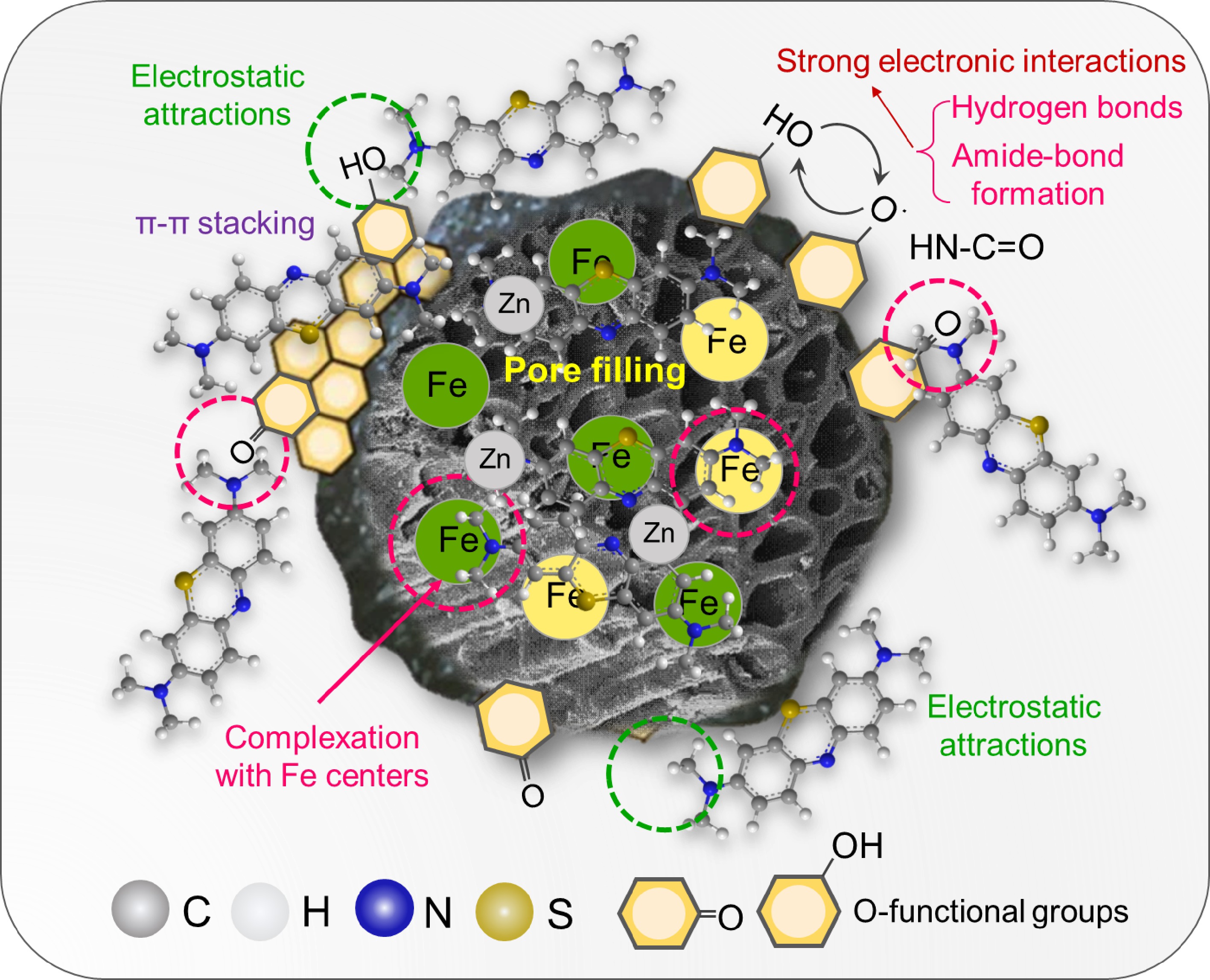

The surface chemical evolution following MB adsorption was elucidated through high-resolution XPS analysis, revealing distinct adsorption mechanisms between the differently modified BCs. In the C 1s spectra, Fe/Zn-OPBC500 exhibited a substantial increase in the HN–C=O component to 74.3% alongside dramatic decreases in C=O and C–C/C=C proportions (as shown in Supplementary Table S1). This remarkable increase in amide functionality originates from three primary mechanisms: (1) strong electronic interactions between the nitrogen-containing groups in the MB molecule and the oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of biochar, including strong hydrogen bonds, ion pairing or amide-like bonds; (2) electrostatic attraction between the cationic dye and negatively charged surface sites; and (3) surface complexation at iron active centers coupled with π−π interactions with the carbon matrix.

Complementing these findings, Fe/Zn-OPBC900 showed only minor functional group variations with a slight reduction in C–C/C=C content (Fig. 8a, b). The O 1s spectra demonstrated a general shift toward higher binding energies after adsorption, with Fe/Zn-OPBC500 displaying a particularly sharp rise in C–O–C content, whereas Fe/Zn-OPBC900 exhibited negligible changes in oxygen speciation (Fig. 8c, d and Supplementary Table S2). Most notably, the Fe 2p region revealed significant chemical state alterations: Fe/Zn-OPBC500 showed an increased Fe(III) proportion (48.7%) following MB adsorption (Fig. 8e, f), indicating electron transfer from MB molecules to iron centers and confirming strong surface complexation through Lewis acid-base interactions[43]. These spectroscopic transformations demonstrate that MB adsorption proceeds through multiple complementary pathways, with Fe/Zn-OPBC500 exhibiting enhanced performance due to its superior capacity for covalent amide bond formation, surface complexation at iron active sites, electrostatic interactions with oxygen functional groups, and π−π interactions with the carbon matrix. The prominent complexation and covalent amide bond formation constitute a key chemisorption mechanism, significantly enhancing the adsorption capacity of Fe/Zn-OPBC500 relative to other modified biochar adsorbents[44−49] (Supplementary Table S3). Compared to other advanced adsorbents, Fe/Zn-OPBC500 demonstrates an integrated performance profile that is crucial for practical application. It combines rapid kinetics, excellent regenerability, and sustainable synthesis from orange peel waste at a moderate temperature. This combination of high efficiency, stability, and eco-friendly production positions it as a promising candidate for scalable wastewater treatment.

Figure 8.

XPS spectra of Fe/Zn-OPBCs after MB adsorption: (a), (b) C 1s, (c), (d) O 1s, and (e), (f) Fe 2p.

To validate the synergistic effect of ZnCl2/FeCl3 co-modification, control BCs (Zn-OPBC500, Fe-OPBC500, Fe/Zn-OPBC700) were synthesized and compared with Fe/Zn-OPBC500. XPS analysis indicated Zn-OPBC500 was rich in oxygen groups, Fe-OPBC500 in Fe–O species, and Fe/Zn-OPBC500 uniquely combined both characteristics (Supplementary Fig. S5). Consequently, the MB adsorption capacity of Fe/Zn-OPBC500 (237.53 mg g−1) significantly exceeded that of Zn-OPBC500 (70.02 mg g−1), Fe-OPBC500 (117.10 mg g−1), and Fe/Zn-OPBC700 (176.15 mg g−1) (as shown in Supplementary Figs S6 and S7). This synergy originates from the complementary roles where ZnCl2 creates an accessible porous scaffold, which in turn facilitates the dispersion and efficacy of the iron-based active sites introduced by FeCl3, culminating in a material with integrated structural and chemical advantages for adsorption.

The adsorption system exhibited rapid kinetics well-described by pseudo-second-order kinetics, confirming chemisorption as the rate-determining step. Thermodynamic analysis verified the spontaneous nature of the adsorption process. Structural characterization revealed the material basis for the superior performance: well-dispersed iron species and preserved oxygen-containing functional groups (particularly C=O and –COOH) collectively creating multiple active sites. Furthermore, the post-adsorption XRD patterns reveal clear differences in structural stability and reaction pathways (Supplementary Fig. S8). Fe/Zn-OPBC500 shows only minor changes, consistent with multimodal MB adsorption mechanisms that preserve the host structure. In contrast, Fe/Zn-OPBC900 exhibits new diffraction peaks (e.g., at 37.3, 36.2, and 30.7°), and reduced background features, indicating significant surface reconstruction and the formation of a new crystalline phase via interfacial reactions. This process consumes active iron sites and potentially blocks micropores, which accounts for the fact that a high surface area does not necessarily lead to the highest adsorption capacity. The remarkable adsorption efficiency primarily stems from four complementary mechanisms: (1) strong electronic interactions between the nitrogen-containing groups in the MB molecule and the oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of biochar, including strong hydrogen bonds, ion pairing or amide-like bonds; (2) electrostatic attraction between the cationic dye and negatively charged surface sites; and (3) surface complexation at iron active centers coupled with π-π interactions with the carbon matrix.

pH-dependent studies identified a point of zero charge at pH 4.2, below which proton competition (H+/MB+) reduces adsorption efficiency. Investigation of ionic interference demonstrated Eisenman selectivity (Fe3+ > Ca2+ >> Na+), further confirming the significance of electrostatic and complexation mechanisms. Regeneration via acidic elution achieved efficient MB recovery through proton-mediated disruption of coordination bonds and hydrogen bonds. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 9, the adsorption mechanism evolves with solution chemistry: under acidic conditions, hydrogen bonding and π−π interactions dominate, while electrostatic attraction prevails under alkaline conditions, with the covalent amide linkage formation and iron-mediated surface complexation remaining operative across the entire pH range. The synergistic combination of these multiple mechanisms, coupled with the hierarchical porous structure of the orange peel-derived biochar, collectively enables the superior adsorption performance of Fe/Zn-OPBC500.

-

This study successfully developed iron-modified hierarchical porous biochar (Fe/Zn-OPBC500) via a co-activation method using ZnCl2 and FeCl3 from orange peel waste. The synergistic effects of the pore development and iron incorporation resulted in an optimized porous architecture with enhanced surface reactivity, delivering a high methylene blue adsorption capacity of 237.53 mg g−1, rapid adsorption equilibrium, and excellent regenerability (retaining above 100 mg g−1 over seven regeneration cycles and maintaining performance across a broad pH range and in the presence of common ions). Thermodynamic analysis and fitting to the Langmuir and pseudo-second-order models indicate that the adsorption process is spontaneous and predominantly monolayer. Multiple synergistic mechanisms contribute to MB removal: covalent amide bond formation between amine groups of methylene blue and carbonyl groups on the biochar, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, surface complexation with iron species, π–π electron donor–acceptor interactions, and hierarchical pore confinement. The superior performance arises from three key structural features: (1) well-developed hierarchical porosity facilitating efficient mass transfer; (2) retained iron species and oxygen-containing functional groups providing abundant active sites; and (3) balanced graphitization preserving both structural stability and surface reactivity. This balance of efficient pollutant removal, operational stability, and eco-friendly synthesis positions the material as a promising and competitive adsorbent for potential application in dye-contaminated wastewater treatment, while providing a viable pathway for the valorization of citrus processing waste.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/bchax-0026-0001.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: writing − review and editing, writing − original draft, funding acquisition: Lei Zhang; methodology, experiment, conceptualization: Xin Liu; investigation, data curation: Wenbo Liu; data curation: Hongying Du; writing − review and editing, funding acquisition: Junkang Guo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42207464), Young Talent Fund of Xi'an Association for Science and Technology (959202413043), Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Provincial Department of Education (24JK0353), Key Research and Development Program of Shaanxi (2025SF-YBXM-511), and the Key Industrial Chain Project of Shaanxi Province (2024NC-ZDCYL-02-15).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Synergistic ZnCl2/FeCl3 activation converts orange waste into hierarchical porous biochar.

Exceptional methylene blue uptake of 237.53 mg g−1 and above 113.24 mg g−1 after seven cycles.

Pyrolysis at 500 °C optimally balances porous structure and surface functional groups.

Synergistic adsorption mechanisms involve complexation, amide bonding, electrostatic, and π–π interactions.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang L, Liu X, Liu W, Du H, Guo J. 2026. Hierarchical porous biochar with Fe/Zn co-activation derived from orange waste: enhanced methylene blue adsorption and mechanistic insights. Biochar X 2: e004 doi: 10.48130/bchax-0026-0001

Hierarchical porous biochar with Fe/Zn co-activation derived from orange waste: enhanced methylene blue adsorption and mechanistic insights

- Received: 10 November 2025

- Revised: 16 December 2025

- Accepted: 03 January 2026

- Published online: 30 January 2026

Abstract: This study presents an innovative and eco-friendly method to convert citrus processing waste into advanced biochar adsorbents via a tailored ZnCl2/FeCl3 co-modification strategy. This dual-activation strategy simultaneously generates hierarchical porous architectures (a 16.1-fold increase in specific surface area and a 5.7-fold rise in total pore volume compared to the pristine biochar), and integrates active surface sites (through FeCl3 modification), thereby leading to substantial structural enhancements. Comprehensive analysis confirmed the formation of iron oxide species alongside preserved oxygen-containing functional groups, collectively generating multifunctional active sites. The optimized Fe/Zn-OPBC500, which balances tailored surface chemistry and hierarchical porous structure, exhibits exceptional methylene blue adsorption, with a capacity of 237.53 mg g−1, and a 96.8% removal rate within 60 min. The adsorption process predominantly adhered to the Langmuir isotherm model, and followed pseudo-second-order kinetic behavior, with thermodynamics confirming spontaneous chemisorption. This high efficiency is governed by multiple synergistic mechanisms, including surface complexation with iron sites, strong electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions, π–π stacking, and pore confinement. Remarkably, the Fe/Zn-OPBC500 also demonstrates excellent practicality, retaining 113.24 mg g−1 over seven regeneration cycles, and maintaining performance across a broad pH range and in the presence of common ions. This study presents a practical approach for citrus waste valorization and provides fundamental insights into the multi-mechanistic adsorption processes, thereby guiding the rational design of advanced carbon-based adsorbents.