-

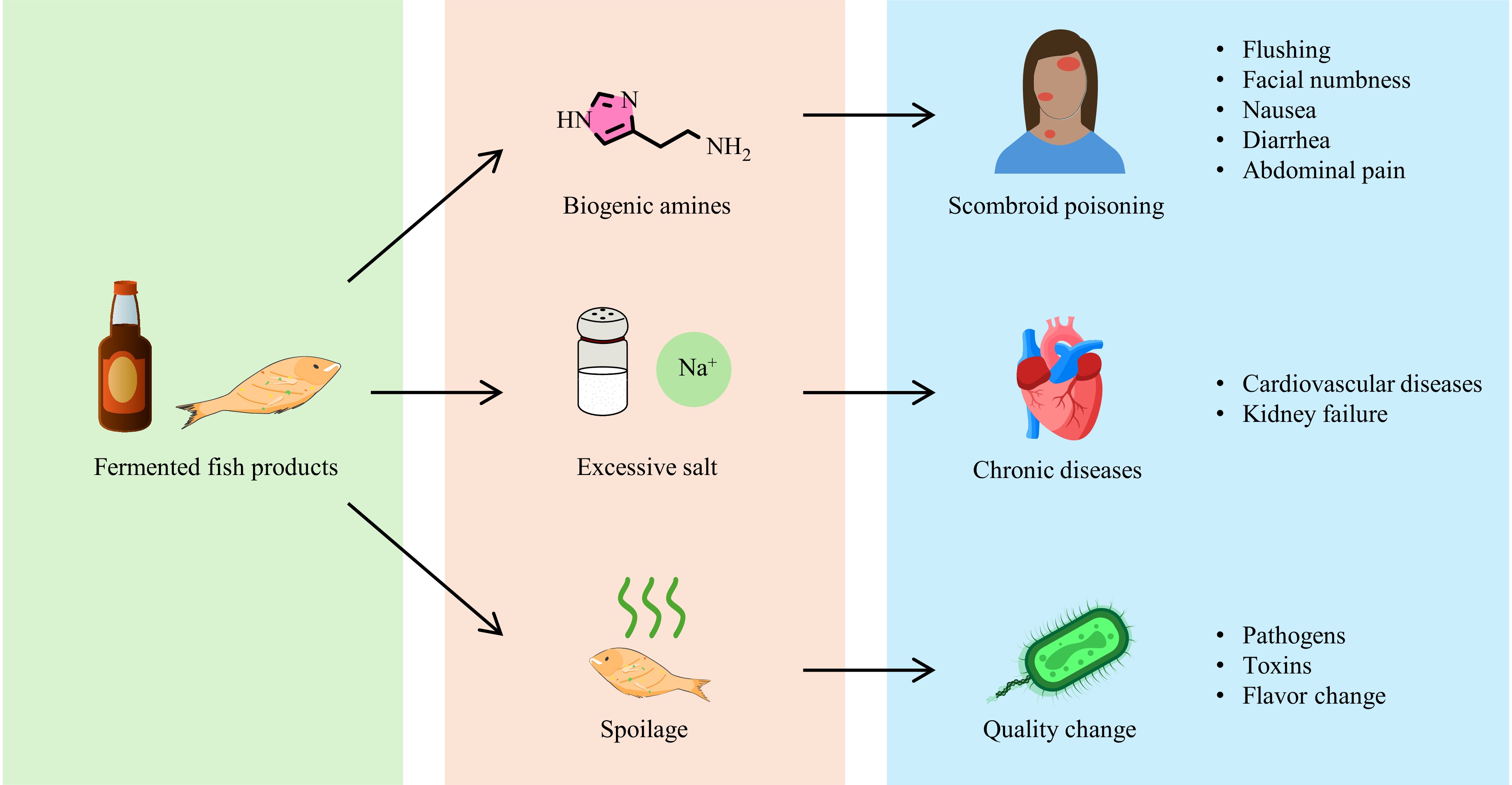

Fermentation has long served as a valuable technique for preserving fish catches while simultaneously enhancing their sensory attributes[1]. The fermentation process not only prolongs the shelf-life of fish products but also enhances their taste complexity through interactions between naturally occurring and microbial enzymes. Fermented fish products come in various forms, from whole fish or fish pieces like hákarl in Iceland[2] and chouguiyu[3] in China to liquid products such as yulu in China[4] and colatura di alici in Italy[5]. Diverse fermented fish products not only highlight the cultural heritage and ingenuity surrounding food preservation but also underscore the importance of understanding the intricate biochemical processes and microbial communities that underpin these diverse transformations. While fermented fish products offer culinary appeal, they also pose significant health risks. These include biogenic amine accumulation, excessive salt content, and potential spoilage during storage (Fig. 1).

Biogenic amines accumulate during microbial metabolic processes[6]. Fish products are particularly susceptible to the decarboxylation of free amino acids induced by microbial activities, leading to the elevation of biogenic amine levels, which can serve as indicators of the freshness and safety of these products. The growth of spoilage bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli) can significantly increase the content of biogenic amines, with histamine (also known as scombrotoxin) being the most toxic[6]. Excessive consumption of histamine can lead to a severe allergy-like condition called histamine poisoning or scombroid poisoning. Scombroid poisoning is a significant foodborne illness. For instance, during the period from 2006 to 2016, it was identified as the most frequent non-recall-related foodborne illness outbreak in the United States[7]. This illness is characterized by symptoms such as flushing, facial numbness, nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal pain[8]. The potential for spoilage and the severe consequences of histamine poisoning pose significant challenges to the production and commercialization of fermented fish products. Diverse strategies have been developed to control the biogenic amines in fermented fish products[9−11]. Despite progress in this area, a comprehensive summary of current knowledge and strategies to control biogenic amines in fermented fish products is still needed.

While biogenic amines present an immediate health concern, the long-term health risks associated with excessive sodium intake, particularly from fermented fish products, are also significant. Traditionally, high salinity is required to modify the microbial growth conditions in fish muscle, inhibiting the growth of spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms while promoting the growth of halophilic microorganisms. For example, the initial ratio of fish to salt in the raw materials used to produce traditional fish sauce may be as high as 2:1[12]. Additionally, commercial Italian[5] and Thai[13] fish sauces contained substantial amounts of salt, reaching about 20% and 25%, respectively. The World Health Organization recommends a daily sodium intake of less than 2 g (about 5 g of NaCl) for adults, but none of the countries have achieved this target[14]. In numerous regions across China, the average daily sodium intake exceeds 5 g, significantly surpassing the recommended guidelines. This excessive consumption has been directly linked to a rising incidence of stroke[14]. Furthermore, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) stated that high intake of sodium was the leading dietary risk for deaths and disability-adjusted life-years in China, Japan, and Thailand[15]. Reducing the salt content of fermented fish products could contribute to a healthier diet and help minimize the negative health impacts associated with excessive sodium consumption. Crafting effective strategies to reduce salt content in fermented fish products without compromising their safety, quality, and consumer appeal presents a formidable challenge that demands continued research and innovative development. Currently, methods to reduce salt in fermented fish products are fragmented and lack a comprehensive review, hindering the development of innovative and effective strategies.

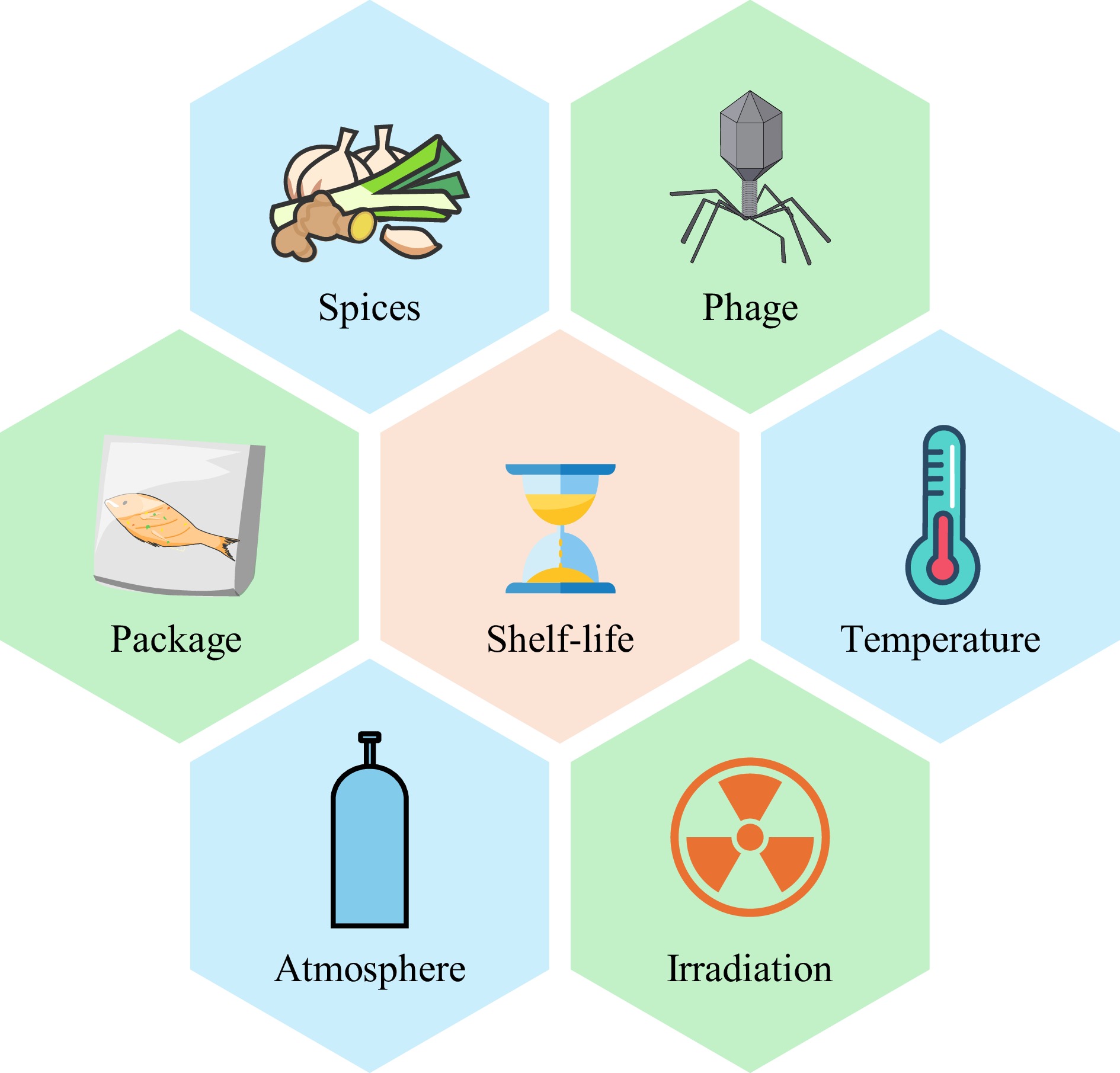

In addition to managing biogenic amine levels and sodium content, preserving fermented fish products is another critical aspect. These products are highly susceptible to spoilage during storage, which poses significant health risks to consumers. The quality and safety of fermented fish products during storage are influenced by multiple factors. For example, storage temperature critically regulates microbial activity and enzymatic reactions, directly impacting spoilage rates[16]. Natural preservatives, such as spices and bacteriocins, further inhibit undesirable microbial growth and mitigate biogenic amine formation[17]. The use of packaging materials can delay oxidative degradation and microbial contamination[18]. Processing technologies like heating and irradiation enhance safety by reducing pathogen loads and extending shelf-life[16]. Understanding how these factors interact and impact the final product is essential for maintaining the cultural significance, economic viability, and consumer appeal of fermented fish.

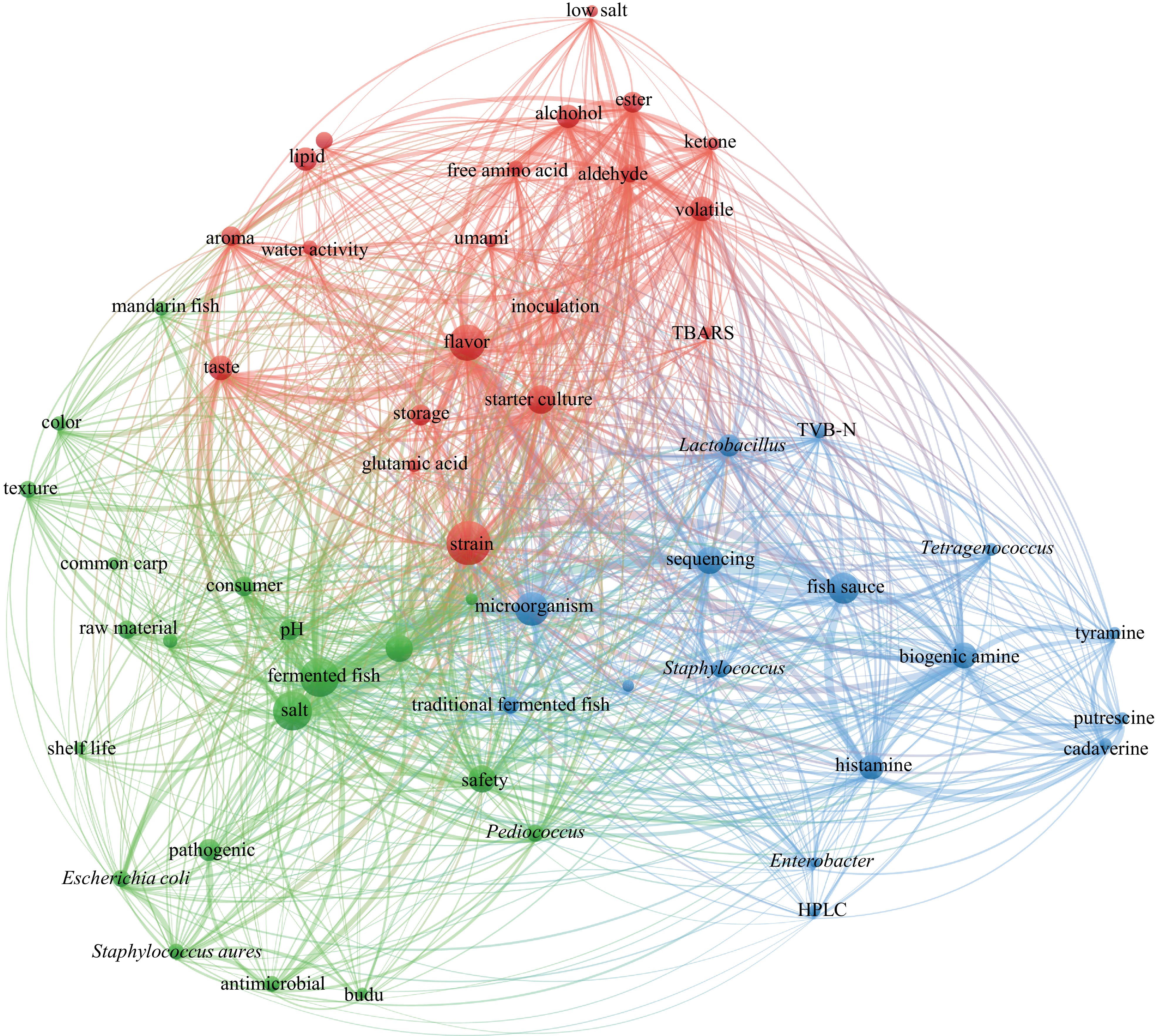

To gain deeper insights into the interconnections and dynamics of scholarly research within this topic, a bibliometric network map (Fig. 2) was created by VOSviewer (version 1.6.19)[19]. The analysis was based on recent publications (2020 onwards) retrieved from Scopus using the search string 'fermented AND fish'. The largest nodes indicate the most frequently occurring terms in recent publications, such as 'strain', 'flavor', 'salt', 'safety', 'starter culture', and 'biogenic amine'. The clustering of these terms reveals three main research themes: (1) organoleptic properties (red cluster), (2) biogenic amines and related microorganisms (blue cluster), and (3) microbial diversity and raw materials (green cluster). The bibliometric analysis provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of research on fermented fish products, thereby setting the stage for a more in-depth exploration of the topic in the subsequent sections of the review.

Figure 2.

Bibliometric network map based on co-occurrences of terms. Note: Size of nodes indicates the importance or frequency of the term. The distance between nodes represents the degree of similarity or relatedness between the nodes. Thickness of edges indicates the strength or frequency of the relationship.

Recent review articles have provided insights into fermented fish products from various perspectives. The aromatic and flavor-presenting substances (e.g., alcohols, aldehydes, and peptides) in fermented fish products and their relationship with microorganisms have been reviewed[20]. Additionally, recent studies have highlighted the potential beneficial effects of fermented fish, including their nutritional and health-related properties (e.g., anti-diabetic effect)[20−22]. Despite these contributions, significant gaps remain in the current understanding of the mechanisms driving the quality and safety challenges associated with these traditional foods. This review seeks to stimulate further research and innovation in this field, ultimately contributing to the development of fermented fish products that meet the evolving demands of consumers while upholding the rich cultural heritage and diversity of these traditional foods.

-

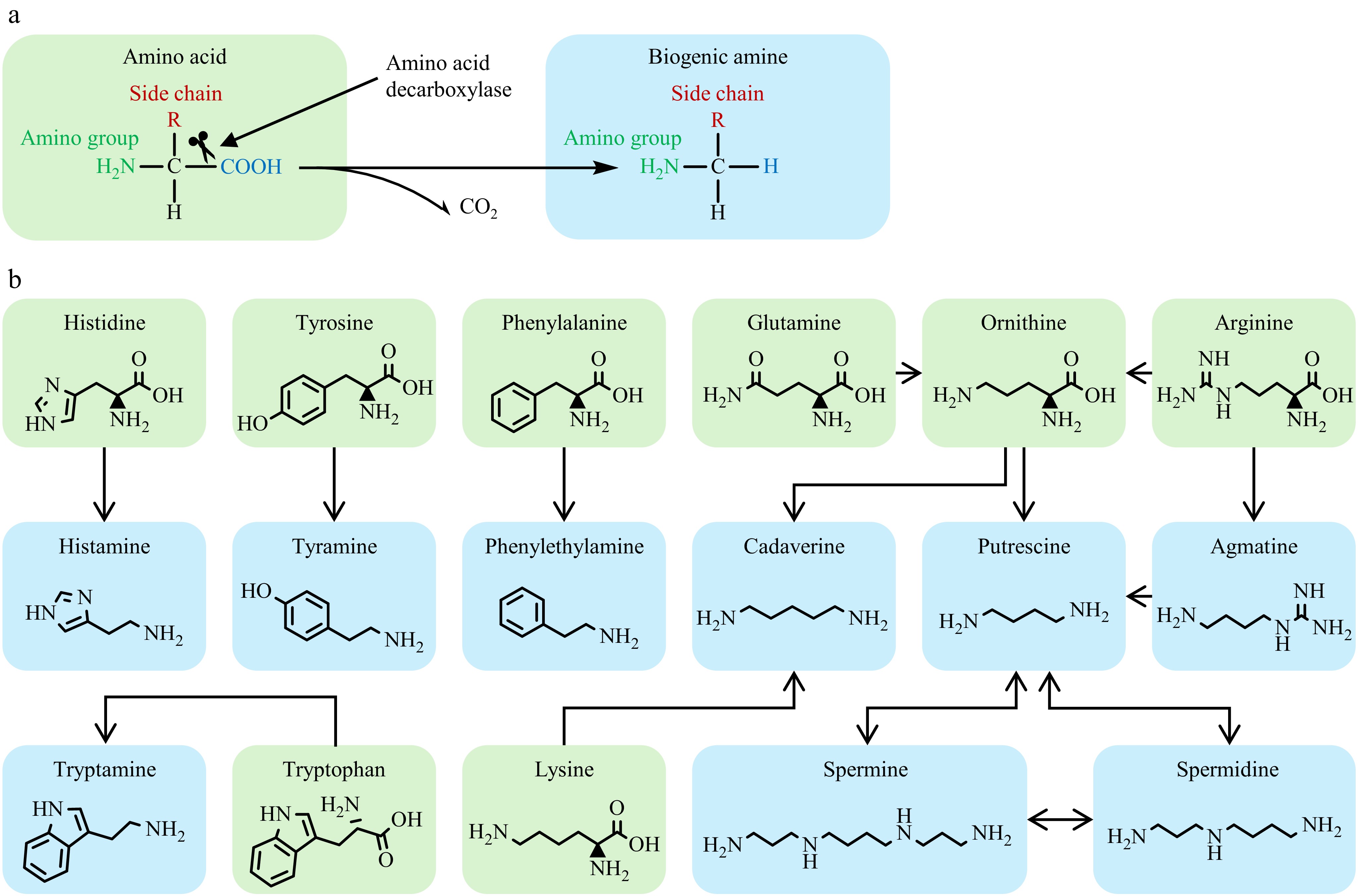

Biogenic amines are low-molecular-weight organic compounds formed mainly through the decarboxylation of free amino acids by the action of microbial amino acid decarboxylases. Based on their chemical structures, biogenic amines can be categorized into aliphatic (e.g., agmatine, cadaverine, and putrescine), aromatic (e.g., phenylethylamine and tyramine), and heterocyclic compounds (e.g., histamine and tryptamine) (Fig. 3)[23]. The formation of biogenic amines in fermented fish products is influenced by various factors, including the availability of free amino acids, the presence of amino acid decarboxylase-producing microorganisms, and the fermentation conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, and salt concentration). The presence of biogenic amines in fermented fish products often indicates poor hygienic conditions during production and storage or the use of spoiled or contaminated raw materials[24].

Figure 3.

Formation of biogenic amines. (a) The action of amino acid decarboxylase. (b) Formation of specific biogenic amines.

Limits of biogenic amines in fermented products

-

Biogenic amines in fermented products are mainly produced by the action of microbial amino acid decarboxylase on free amino acids[25]. Histamine, the decarboxylated product of histidine, is the most toxic biogenic amine[6]. Authorities around the world have set allowable limits on histamine. In the European Union, the maximum allowable histamine content in fish sauce and brine-fermented histidine-susceptible fish (e.g., Scombridae, Clupeidae, Engraulidae, Coryfenidae, Pomatomidae, and Scombresosidae) is 400 mg/kg[26]. In Canada, the maximum allowable histamine content in fermented fish sauces and pastes is 200 mg/kg[27]. Similarly, Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) rules that the maximum allowable histamine content in fish and fish products is 200 mg/kg[28]. In China, the maximum allowable content of histamine in fishery products is 50 mg/kg[29]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) considers fish samples adulterated if they contain histamine levels of 35 ppm or higher due to decomposition or unsanitary production conditions, as this indicates spoilage[30]. Additionally, samples with histamine levels of 200 ppm or higher are deemed to pose a health risk due to potentially harmful concentrations, according to a recent draft Compliance Policy Guide[30]. However, studies have revealed considerable fluctuations in histamine levels within fermented products. For instance, the histamine content in the laboratory-made fermented mackerel was up to 228.52 mg/kg[10]. The histamine content of commercial Cambodian fermented fish paork chav ranged from 32 to 840 mg/kg, while that in Cambodian fish pastes prahok was 35–408 mg/kg[31]. Ten commercial fish sauce products (five of them were imported products) in China contained 0–249.3 mg/kg histamine with a median number of 52.4 mg/kg according to a survey[32]. In a survey of various fish product samples collected in Italy from 2010 to 2015, about 2.90% (135 out of 4,615) of them exceeded the histamine limits set by EC Regulation No 2073/2005, with street vendors accounting for approximately 80% of these non-compliant samples[33]. These findings underscore the need for continued monitoring and potential adjustments to production practices to ensure consumer safety and regulatory compliance (Table 1).

Table 1. Histamine limits for fermented fish products by region.

Region Limit (mg/kg) Product type Ref. Europe Union 400 Fish sauce and brine-fermented histidine-susceptible fish [26] Canada 200 Fermented fish sauces and pastes [27] Australia and

New Zealand200 Fish and fish products [28] China 50 Fishery products [29] United States* 200 Scombrotoxin-forming fish and fishery products [30] * Currently a final Compliance Policy Guide. Factors influencing biogenic amine formation

Environmental conditions

-

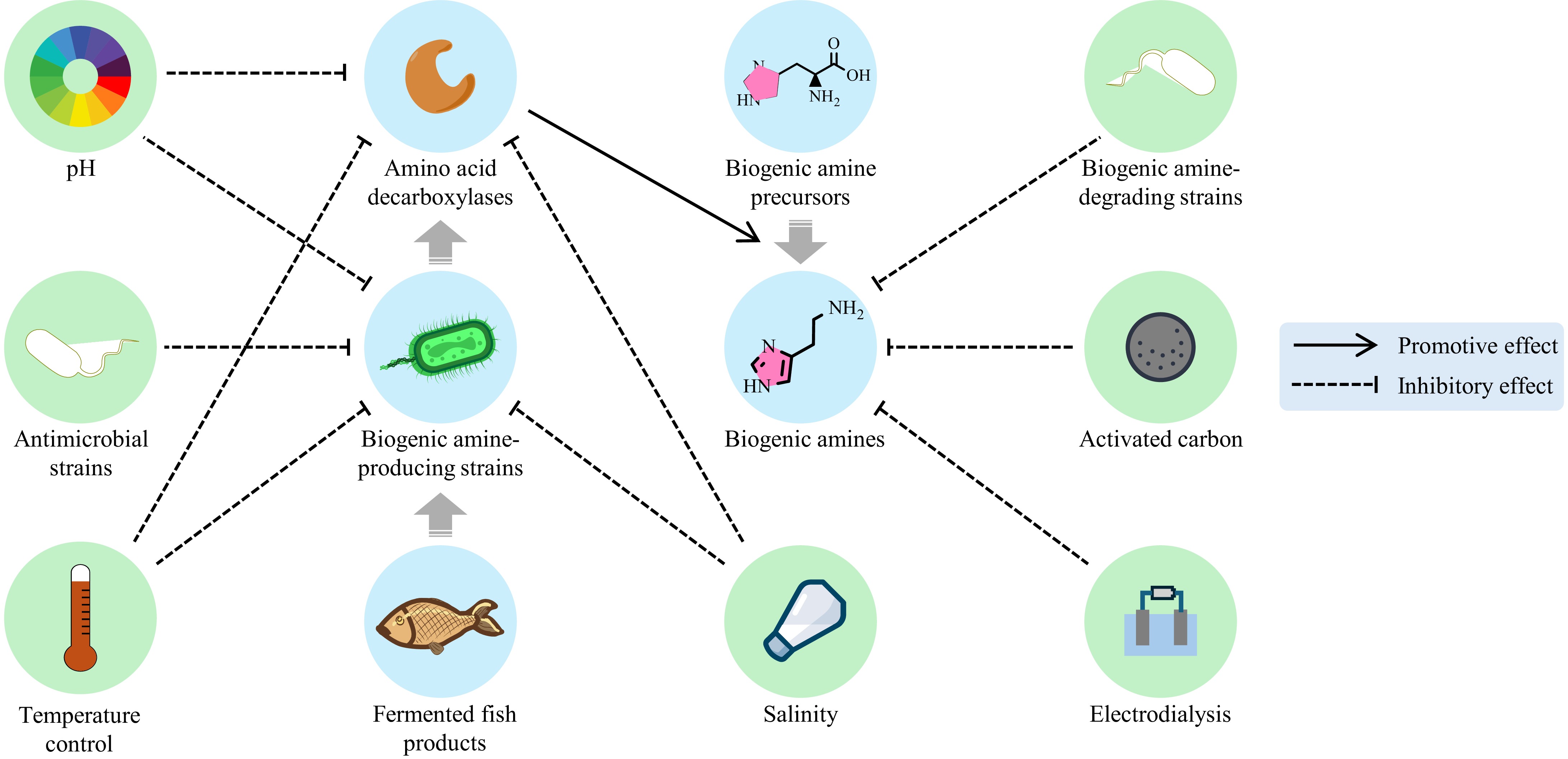

Research has shown that elevated salinity and reduced pH levels can significantly suppress the growth of microorganisms responsible for biogenic amine production. Additionally, these conditions inhibit the activity of amino acid decarboxylases, the enzymes involved in their synthesis. As a result, the final product exhibits notably lower concentrations of biogenic amines[34−36]. For example, padaek fermented with an initial salinity of 6.5%–10% showed significant histamine accumulation within six months (> 1,000 mg/kg), whereas the product fermented with an initial salinity of 18% did not show detectable histamine during the same period[34]. The Codex Alimentarius recommends a minimum NaCl concentration of 200 g/L in fish sauce[37]. The inhibitory effect of high salinity against biogenic amine-producing microorganisms contributes to lowering the formation of biogenic amines. Specifically, the osmotic stress caused by elevated salt concentrations limits the growth and survival of these microorganisms[34,38]. The interaction mechanism between sodium ions and amino acid decarboxylases remains uncharacterized and requires targeted investigation.

The accumulation of biogenic amines is also significantly influenced by acidity. The Codex Alimentarius recommends a pH range of 5.0–6.5 for traditional fish sauce[37]. The growth and metabolism of biogenic amine-producing microorganisms are highly dependent on the acidity of the fermentation environment. Low pH conditions, typically achieved through the production of organic acids by lactic acid bacteria (LAB), can inhibit the growth of spoilage bacteria and other undesirable microorganisms, thereby reducing the risk of biogenic amine formation[35]. Furthermore, low pH environments can also inhibit the activity of amino acid decarboxylases. For instance, a recent study revealed that the enzymatic activity of histidine decarboxylase, isolated from Morganella psychrotolerans, exhibited its maximum efficiency at pH 7, achieving a relative activity of 100%. However, this activity significantly declined to 16%, 49%, 76%, and 48% at pH levels of 4, 5, 6, and 8, respectively, demonstrating a clear pH-dependent behavior. This finding underscores the enzyme's optimal performance under neutral conditions and its sensitivity to deviations from this pH range[39]. Thus, maintaining an acidic environment during the fermentation process is important to suppress the growth of biogenic amine-producing microorganisms and inhibit the activity of amino acid decarboxylases.

Previous studies have reported a positive correlation between fermentation temperature and biogenic amine production, with higher temperatures (typically 25–35 °C) promoting greater accumulation[11,40]. For instance, the fermentation of bream at 4, 10, and 20 °C for 4 d increased its content of biogenic amines by 1.04, 1.60, and 4.18 times, respectively[11]. Another study found that increased fermentation temperature from 25 to 35 °C significantly increased the content of biogenic amines from 56.92 to 266.15 mg/kg in fish sauce[40]. The authors attributed this increase to the enhanced growth of biogenic amine-generating bacteria at higher temperatures, such as Enterobacteriaceae[35] and Lentibacillus[40]. It was suggested that the optimal temperature for biogenic amine-generating bacteria was 25–35 °C, although few specific strains still exhibited a strong amine-producing capacity at low temperatures (4–15 °C)[35]. In addition to its impact on microbial growth, temperature also directly influences the activity of amino acid decarboxylases. The relative activity of the histidine decarboxylase extracted from Morganella psychrotolerans at 10, 20, and 40 °C was 50%, 50%, and 30% of its activity at 30 °C, respectively[39]. This suggests that fermented fish products processed at ambient temperatures (25–35 °C) are particularly prone to biogenic amine accumulation, as these conditions favor both the growth of amine-producing microorganisms and the heightened activity of amino acid decarboxylases. To ensure the safety and quality of fermented fish products, it is essential to maintain controlled fermentation temperatures, ideally below 25 °C, throughout the process to limit the growth of biogenic amine-producing microorganisms and reduce decarboxylase activity[11,35].

Microbial influences

-

Several bacterial genera are positively correlated with the accumulation of biogenic amines in fermented fish products, contributing to safety concerns. Previous studies have identified Pseudomonas, Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, Lactiplantibacillus, Psychrobacter, Peptostreptococcus, Fusobacterium, and Tetragenococcus as key contributors[4,41,42]. Specifically, histamine production is strongly associated with Vibrio, Halomonas, Enterococcus, Tetragenococcus, Macrococcus, and Weissella[42,43]. For instance, in 36 salted fish samples from south China, dominant histamine-forming bacteria included Lactococcus lactis, Morganella morganii, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Staphylococcus xylosus, Vibrio alginolyticus, and Vibrio rumoiensis, with Vibrio alginolyticus being the most prevalent[44]. The underlying mechanism involves the expression of amino acid decarboxylase genes, such as the histidine decarboxylase gene (hdc) that encoded histidine decarboxylase, the enzyme that converts histidine to histamine in Gram-positive bacteria[45]. In Enterobacteriaceae, genes like ornithine decarboxylase (odc), biosynthetic arginine decarboxylase (speA), agmatinase (speB), biodegradative arginine decarboxylase (adiA), and lysine decarboxylase (ldc) are prevalent, driving biogenic amine production[35,46].

In contrast, certain bacterial genera exhibit a negative correlation with biogenic amine levels, offering the potential for improving product safety. Staphylococcus and Tetragenococcus, for example, have been shown to reduce biogenic amine accumulation in some contexts[17,42]. This variability may stem from strain-specific differences, as not all strains within these genera produce decarboxylases. For instance, among 42 dominant LAB strains isolated from suanyu, eight strains (GenBank ID: LC379973.1, MH844891.1, MK203024.1, FJ532360.1, KX139194.1, MG383778.1, and JQ043368.1) exhibited amino acid decarboxylase activity, while others did not[47]. The mechanisms reducing biogenic amine levels may include competitive exclusion of amine-producing bacteria or the absence of decarboxylase genes in specific strains. Therefore, minimizing the presence of Enterobacteriaceae and selecting LAB strains with low decarboxylase activity are critical strategies for enhancing the safety of fermented fish products.

Inoculation strategies

-

Inoculation of appropriate starter cultures has emerged as a promising method for minimizing the formation of biogenic amines in fermented fish products. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of starter culture inoculation in reducing biogenic amine levels compared to spontaneous fermentation[10,48]. The mechanism by which starter cultures inhibit biogenic amine formation is through the rapid acidification of the fermentation medium, which retards the propagation of bacteria with amino acid decarboxylase activities. For instance, the inoculation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CP-134 (GenBank ID: MK601693.1), a salt-tolerant LAB strain isolated from suanyu, resulted in a rapid decrease in pH to 3.6 within 3 d. This acidification effectively inhibited the growth of competitive bacteria, making this strain a promising candidate for the production of high-salt fermented fish products with reduced biogenic amine content[47]. Similarly, the total biogenic amine content in spontaneously fermented carp pastes (1,885.28 mg/kg) was up to 4.87 times higher than that in products inoculated with a mixture of LAB and yeast starter cultures due to the significant inhibition of biogenic amine-producing microorganisms (Enterbacteriaceae)[49]. The histamine contents in the fermented mackerel inoculated with two Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strains also decreased by 86.5%–96.9% compared with that in spontaneously fermented mackerel due to the inhibition of histamine-producing bacteria Morganella morganii[10]. The authors also noted that the Lactiplantibacillus plantarum strains used in the study harbored plantaricin EF and JK genes, which may contribute to the inhibition of undesired bacteria[10].

In addition to LAB strains, other microbial groups have shown promise as starter cultures for reducing biogenic amine formation in fermented fish products. Halophilic archaea and bacteria isolated from fermented anchovy, such as members of the family Halobacteriaceae and the genera Halomonas and Chromohalobacter, have demonstrated histamine-degrading capabilities[50]. Similarly, the archaea including Halobacterium salinarum (GenBank ID: MK634472 and MK634473), and bacteria including Halomonas utahensis (GenBank ID: MK634470) and Halovibrio denitrificans (GenBank ID: MK634471) showed histamine-degrading capacity[51]. Halomonas utahensis (GenBank ID: MK634470) is known to produce off-odor volatile compounds, including indoles and hydrogen sulfide (H2S)[51]. These byproducts can significantly impact the sensory quality of fermented fish products, potentially limiting the practical application of this bacterium in fish fermentation processes. An archaeal histamine oxidase isolated from Natronobeatus ordinarius (CGMCC 1.13785) can retain at least half of its maximum activity within the NaCl concentrations from 0.5 to 2.5 M[52]. Notably, 100 μg of this enzyme in 10 g of fish sauce could degrade 37.9% of the histamine within 24 h at 50 °C[52]. A previous study found that Staphylococcus nepalensis 5-5 may metabolize histidine into compounds other than histamine, thereby reducing the accumulation of biogenic amines in fish sauce[53]. Similarly, Lentibacillus has also been reported to have biogenic amine-degrading ability in fermented fish products[41,42]. In addition, Virgibacillus campisalis demonstrated the capability to degrade 17.6%–26.9% of histamine present in fish sauce products within a 24-hour period under static culture conditions[54].

Other strategies

-

Essential oils also showed inhibitory effects on biogenic amines[9]. The addition of Bunium persicum essential oil (0.1%) and garlic essential oil (0.1%) decreased the histamine content in fish sauce from 16,339.00 mg/kg to 8,403.05 and 10,596.15 mg/kg, respectively[9]. Various types of activated carbon products have been employed to remove biogenic amines from fermented fish products[55]. The reduction of biogenic amines (e.g., tryptamine and phenethylamine) in anchovy fish sauce ranged from 86.1% to 100% with the use of activated carbon products, while the reduction of histamine was comparably lower, with 13%–42%[55]. In another study involving industrial-scale fish sauce production, treatment with 2% activated carbon and 0.9% diatomite at 27 °C for 97 min effectively reduced tryptamine, tyramine, histamine, and cadaverine by 100%, 96%, 61%, and 10%, respectively[56]. Activated carbon's lower efficiency in removing histamine compared to other biogenic amines (e.g., tryptamine and phenylethylamine) emphasizes the need for further research to enhance its adsorption properties. Electrodialysis can be used for histamine removal in fermented fish sauce[57]. The optimal conditions of electrodialysis (pH 3.8, 5.1 A input current, and 40 L/h flow velocity) reduced histamine content by 53.41%, while it minimized the loss of amino nitrogen (15.46%). In addition, the histamine content in the final product was below the allowable limit (400 mg/kg)[57].

General discussion on biogenic amines

-

The occurrence of biogenic amines in fermented fish products poses a significant food safety concern. The formation of biogenic amines is influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including the availability of precursor amino acids, the presence of biogenic amine-producing microorganisms, and the fermentation conditions, such as temperature, pH, and salt concentration (Fig. 4). In conclusion, managing fermentation conditions, such as salinity and pH, offers a practical approach to controlling biogenic amine formation; however overcoming the associated challenges remains critical for ensuring product safety and quality.

Although studies have identified correlations between certain microbial genera and biogenic amine levels, the actual ability to produce these compounds varies among strains within the same genus. The application of starter cultures may not consistently lower biogenic amine levels, as their effectiveness depends on the specific strains used and fermentation conditions. This highlights the importance of comprehensive screening and characterization of the microbial population in fermented fish products to identify the specific strains responsible for biogenic amine formation.

-

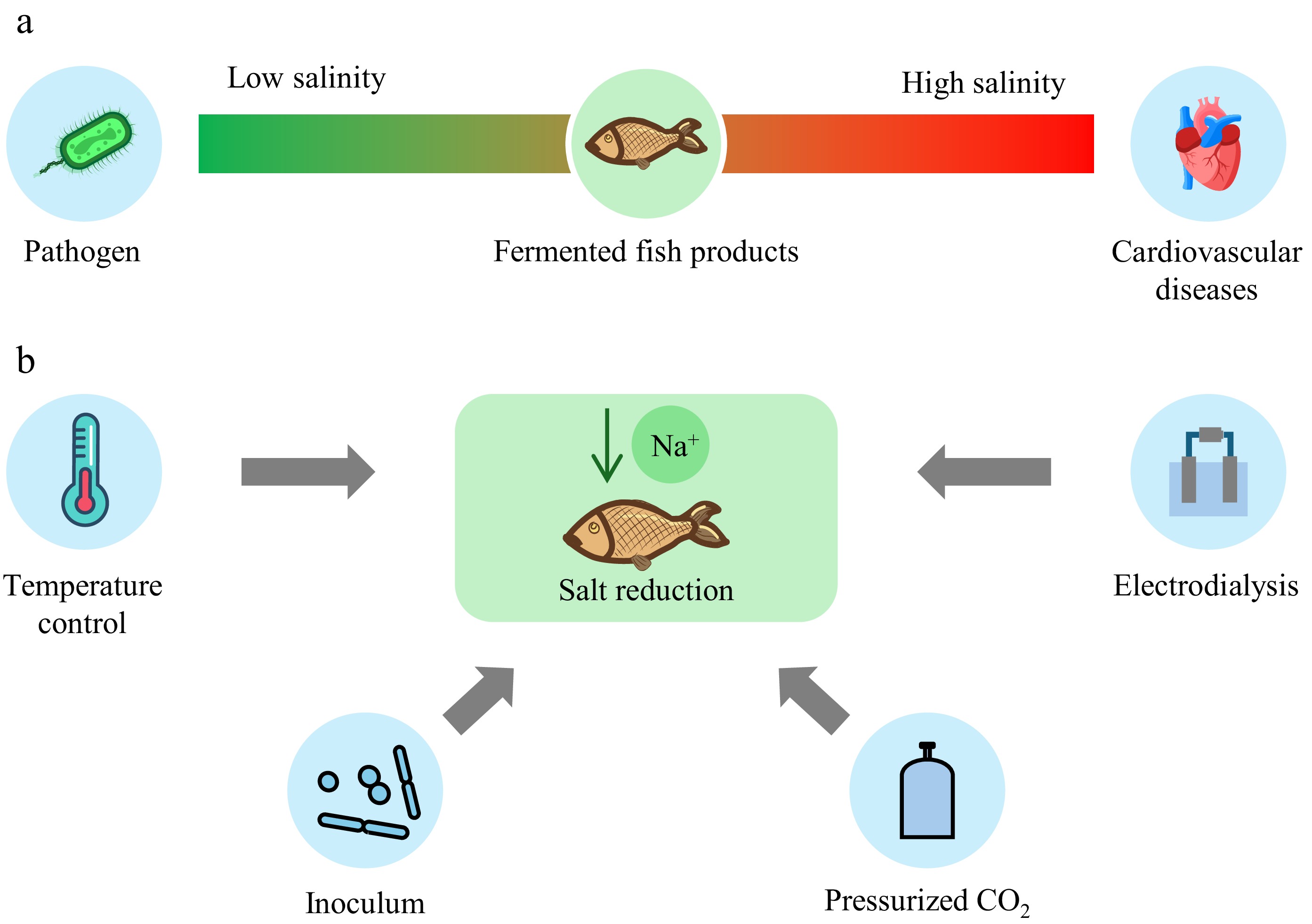

In addition to biogenic amines, another significant health concern associated with fermented fish products is their high salt content. As discussed previously, salt plays a critical role in inhibiting the growth of spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms, promoting the growth of desirable halophilic bacteria, and contributing to the development of characteristic flavor compounds. For instance, omitting salt during the production of ayu-narezushi from Japanese sweetfish (Plecoglossus altivelis) allowed the growth of Aeromonadaceae, a bacterial family linked to foodborne illnesses[58]. In contrast, adding 9% salt to fermented Spanish mackerel reduced total volatile basic nitrogen, which indicates spoilage, by nearly half compared to the sample with 3% salt after 2 d of fermentation[38]. However, the high salt content of these products has become a growing concern due to the well-established link between excessive sodium intake and adverse health effects. Reducing the salt content of fermented fish products is, therefore, an important public concern to promote healthier diets and reduce the burden of non-communicable diseases. Balancing food safety and salt reduction in fermented fish products is essential, as lower salt levels may compromise microbial control while addressing consumer health concerns.

Methods to reduce salt content

Fermentation conditions

-

Meticulously regulating fermentation conditions can effectively reduce salt content in fermented fish products. Temperature is a key factor affecting the proliferation of microorganisms, and it can be manipulated to compensate for the reduced inhibitory effect of lower salt concentrations on spoilage and pathogenic bacteria. A lower fermentation temperature can slow down microbial growth, allowing for the production of safe and salt-reduced products. The Listeria monocytogenes growth on rakfisk (fermented stout and char) fermented with 4.6% NaCl at 4 °C was significantly inhibited compared with that on the rakfisk fermented with 6.3% NaCl at 7 °C during a 91-day fermentation process[59], indicating that lower temperature could compensate for the reduced salt content in controlling the growth of this pathogenic bacterium. However, the authors observed that rakfisk fermented at 4 °C required a longer fermentation time (at least five months) than at 7 °C (three months), illustrating the trade-off between temperature and extended processing duration[59]. A two-stage fermentation process—10 °C for 2 d followed by 20 °C for 2 d—has been shown to enhance flavor complexity while maintaining biogenic amine levels below safety thresholds[11]. However, not all studies have reported consistent results regarding the effects of temperature on salt reduction in fermented fish products. For example, a negative correlation was observed between fermentation temperature (25–50 °C) and the levels of biogenic amines in low-salt fish sauce, suggesting that higher temperatures could inhibit the growth of biogenic amine-producing bacteria[12] These findings highlight the complexity of the relationship between temperature and salt reduction in fermented fish products.

Inoculation strategies

-

The inoculation of starter cultures is another promising strategy to produce low-salt fermented fish products. One notable example is the use of Bacillus velezensis DZ11, a non-halophilic bacterium that can grow well at the salinity range of 0–10% but cannot tolerate the salinity higher than 10%[60]. This strain was successively applied for the production of low-salt (9% NaCl) fermented fish paste, resulting in improved sensory quality compared to those spontaneously fermented with 9% and 25% salt[60]. LAB strains have also shown potential as starter cultures for low-salt fermented fish products. For example, LAB strains such as Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 11, Lactiplantibacillus 69, and Lactiplantibacillus DSM1055 have been applied to produce low salt (4%) fermented croaker products[61]. The authors found that these LAB strains also reduced fermentation time, as the lower salt content exerted less inhibitory effects on lipase activity[61]. Similarly, mixed starter cultures containing LAB strains (Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 120 and Staphylococcus xylosus 135) and yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae 31) have been employed in the production of low-salt suanyu[62] and fish paste[63], resulting in enriched aromatic profiles.

The application of starter cultures has also been explored in the production of low-salt fish sauce. Three non-halophilic LAB strains (Limosilactobacillus fermentum PCC, Lactiplantibacillus plantarum 299v, and Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris 20069) were tested for their ability to produce salt-reduced fish sauce using Nile tilapia heads[64]. Limosilactobacillus fermentum PCC produced the most significant levels of volatile compounds among the tested strains in the fish sauce during 3-d fermentation at 37 °C[64]. The research group subsequently investigated the effects of the inoculation with Lactiplantibacillus pentosus 1 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae 31 on the catfish (Ietalurus punetaus) bone for the production of salt-reduced fish sauce[65]. The co-inoculation of these two strains resulted in a faster rate of acid production and amino nitrogen generation compared to the single-strain inoculation, as well as improved sensory attributes of the final product. In addition to salt-reduced fermentation, the inoculation of Planococcus maritimus XJ2, a strain with high protease activity at low salt concentrations (0–9% NaCl), in the fermentation of Chinese longsnout catfish (Leiocassis longirostris) with 8% salt at 21 °C for 15 d resulted in significantly higher levels of characteristic flavor compounds (e.g., alcohols, ketones, acids, esters, and pyrazines) compared to the uninoculated control[66]. Another study developed a low-salt fermented Nile tilapia using 5% NaCl and a starter culture containing Bacillus and Virgibacillus strains, which was compared to traditionally fermented fish, which used 20% NaCl without added cultures[67]. The low-salt fermentation process with starter cultures significantly accelerated production, reducing the fermentation time of Nile tilapia from months to just four weeks[67]. The collective evidence from these studies demonstrates that carefully selected starter cultures can effectively facilitate salt reduction in fermented fish products through multiple mechanisms.

Novel processing technologies

-

Apart from the fermentation conditions, advanced techniques were also used to produce low-salt fish products. Pressurized carbon dioxide (CO2) was applied in the production of salt-reduced fish sauce, which suppressed the growth of anaerobic bacteria and inhibited the oxidation of lipids, thus preventing the production of undesired compounds[68]. In this study, the treatment of sardine with 10% salt and 3–5 MPa pressurized carbon dioxide at 30 °C for six months resulted in higher free amino acid content and the absence of certain biogenic amines, such as putrescine, histamine, and tyramine, which were present in the fish sauce prepared with 20% salt under ambient conditions[68]. The research group further applied pressurized CO2 (5 MPa) in the production of low-salt (10%) fish sauce using single fish species and their mixtures[69]. Following a two-month fermentation at 30 °C, the viable mesophilic bacteria count in the control samples (20% NaCl at ambient pressure) ranged from 104 to 107 CFU/mL. In contrast, no viable bacteria were detected in any of the CO2-pressurized samples, demonstrating the inhibitory effect of pressurized CO2 on microbial growth. Additionally, the CO2-pressurized samples exhibited similar aromatic profiles to their non-pressurized counterparts but with increased levels of free amino acids[69]. Another emerging technology that has been applied to the production of low-salt fermented fish products is electrodialysis, a membrane-based process that utilizes an electric current to remove ions from a solution selectively. The electrodialysis was used for the reduction of salt content in fish sauce[57]. The authors found that increasing the input current applied to the electrodialysis system from 3.0 to 7.0 A resulted in an increased salt reduction rate, ranging from 33% to 75%. However, the electrodialysis treatment altered the volatile composition of the fish sauce, reducing alcohols and aldehydes, and increasing ketones and organic acids, potentially affecting flavor profiles[57].

General discussion on salt reduction

-

This section explores different strategies for achieving salt reduction (Fig. 5), such as the optimization of the fermentation conditions and the application of emerging technologies[60,62−64,66]. The reduction of salt content in fermented fish products remains a complex challenge especially considering the various roles that salt plays in ensuring product safety, quality, and sensory acceptability. One of the main challenges in salt reduction is maintaining the safety of fermented fish products. The use of starter cultures has been proposed to compensate for the reduced salt content by promoting the rapid growth of desirable microorganisms that can outcompete potential contaminants. However, the success of this approach relies heavily on the careful selection and optimization of starter cultures that can thrive in low-salt environments while producing the desired sensory attributes and inhibiting the growth of undesirable microorganisms. Moreover, the economic availability and practicality of implementing salt reduction strategies in the fermented fish industry are also important considerations. Many of the approaches discussed in this section, such as the use of lower temperatures, pressurized carbon dioxide, and electrodialysis, require specialized equipment, knowledge, and resources that may not be readily available or affordable for small-scale producers.

-

The effects of heating (85 °C for 30 min) and irradiation (7 kGy) on the quality and safety of vacuum-packed suanyu during storage at an ambient temperature were studied[16]. Both techniques accelerated the oxidation of lipids, suggested by the respective 1.26- and 1.15-fold increases in thiobarbituric acid reactive substances for the heated and irradiated samples compared with the untreated sample at day 90. The total biogenic amine contents of all samples at day 90 were not statistically different, but the total biogenic amine contents of the irradiated sample of days 1, 30, and 60 were much lower than those of the heated samples and the untreated samples[16]. More processing technologies should be investigated in the future.

Storage condition

-

Storage time and temperature significantly influence the quality and safety of fermented fish products. Microbial and enzymatic activities persist in post-fermentation, driving ongoing biogenic amine formation. For instance, histamine content in anchovy fish sauce increased from 43.3 mg/100 mL to 89.7, 102.6, and 116.8 mg/100 mL after one year of storage at 10, 25, and 35 °C, respectively[70]. Notably, higher temperatures accelerated histamine accumulation over the same period, demonstrating that histamine levels rise with both prolonged storage duration and elevated temperatures. Similarly, the suanyu stored at 4 °C for up to three months had lower thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances values, total volatile basic nitrogen, proteolytic activities, and less changes in odor quality than the samples stored at 25 and 35 °C[71]. This indicates that low storage temperatures are preferable for the maintenance of sensory attributes.

Packing methods

-

The choice of packaging materials and methods can affect the rate of chemical and enzymatic reactions, the growth of microorganisms, and the retention of volatile flavor compounds. A previous study compared the effects of different packaging methods and modified atmosphere packaging with 90% CO2 on the shelf-life of pla-duk-ra, a Thai fermented catfish product, during storage at ambient temperature[18]. The pla-duk-ra packed with polypropylene bags and nylon/linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE) bags were spoiled within 30 and 60 d, respectively. The shelf-life of pla-duk-ra with modified atmosphere packing (90% CO2) and vacuum packing was extended to 90 d. Especially, the product with atmosphere compressing of 90% of CO2 and 10% N2 had the highest sensory scores[18]. The research group further investigated the application of different packaging materials and sous vide on the shelf-life of pla-khem-neur-som (Thai dried sour-salted fish)[72]. In this study, samples were vacuum-sealed in nylon/LLDPE bags and subsequently subjected to sous vide cooking (40–60 °C, 15–120 min). After storage at 28–30 °C, the samples packed with polypropylene bags spoiled within one week, but the shelf-life of sous vide-cooked samples in the vacuum-packed nylon/LLDPE bags ranged from three to four weeks[72].

Natural preservatives

-

The addition of natural preservatives has gained increasing attention as a sustainable and consumer-friendly approach to improving the preservation and storage of fish products[73]. ListexTM P100, a commercial anti-listerial bacteriophage, has been applied in the production of rakfisk[59]. This anti-listerial bacteriophage and has been approved in many regions, such as Australia, Canada, the European Union, New Zealand, and the United States[74]. Compared with the sample without pretreatment, the addition of 108 and 109 PFU/sample of ListexTM P100 prior to vacuum-packing reduced the number of Listeria monocytogenes by 0.6 and 1.2 log, respectively[59]. More bacteriophages should be tested on fermented fish products in the future.

Apart from the addition of bacteriophage, the effects of spice addition (paprika, fennel, and cinnamon) and starter culture inoculation on the quality and safety of suanyu during 90 d of storage were studied[17]. The authors reported that the samples with both spices and starter culture had significantly lower total biogenic amine content (95.76 mg/kg) than those with only starter culture (153.91 mg/kg) or without any additives (588.44 mg/kg). The possible explanation might be the phytochemicals present in the spices that inhibited the growth of biogenic amine-producing bacteria[17]. The antimicrobial effects of spices can vary significantly. For example, fermented tilapia with black pepper showed the most potent inhibition against Bacillus cereus, while the product with chili demonstrated the highest efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella Typhimurium[75]. The discrepancy in antimicrobial activity can likely be attributed to the diverse chemical compositions of different spices. Further research is needed to explore the synergistic effects of different preservation methods, develop novel and sustainable packaging materials and technologies, and assess the potential of natural preservatives and biopreservation strategies for the fermented fish industry.

General discussion on preservation and storage

-

Previous studies have mainly focused on the storage of solid fermented fish products (Fig. 6), while the preservation of fish sauce has received less attention. Fish sauce, being a liquid product, may have different storage requirements and challenges compared to solid fermented fish products. Additionally, various non-thermal pre-treatments (e.g., ozonation, pulse electric field, non-thermal plasma, and ultraviolet radiation) may also be applied to these products to assess their effects on sensory profiles and shelf-life. Furthermore, the development of rapid, non-destructive, and cost-effective methods for monitoring the quality and safety of fermented fish products during storage is another important research gap that needs to be addressed. The development of freshness indicators or intelligent colorimetric packaging is favored to monitor spoilage[76]. As the fish meat spoils during storage, the gradually generated total volatile basic nitrogen and ammonia increase the pH of the nanofibers, causing a color change that indicates the extent of spoilage[77]. Ultimately, further research is necessary to investigate the synergistic effects of various preservation methods and to develop novel, sustainable packaging materials and technologies. Crucially, these advancements should not compromise the sensory quality and nutritional value of these products.

-

Fermented fish products hold profound cultural and nutritional significance as staples of culinary heritage across diverse regions. These foods are celebrated not only for their unique flavors and role in sustainable food preservation but also for their contribution to global gastronomic diversity. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the challenges and opportunities in enhancing the safety and quality of fermented fish products. It highlights critical issues, including the accumulation of biogenic amines, excessive salt content, and perishability during storage. Strategies such as employing targeted starter cultures, optimizing fermentation conditions, and integrating advanced preservation techniques are discussed as effective approaches to address these concerns. The review consolidates current knowledge on these topics, serving as a valuable resource for researchers and industry professionals aiming to improve fermented fish products. By offering insights into these interconnected challenges, this work underscores the importance of innovative approaches in ensuring product safety, maintaining sensory quality, and preserving the cultural significance of these traditional foods.

This review identifies several significant research limitations and knowledge gaps. First, most studies on starter cultures focus on laboratory-scale fermentation, with limited validation in industrial settings. Many studies also lack comprehensive investigations into the synergistic effects of these strategies. Additionally, the diversity of microbial communities and their strain-specific contributions to fermentation remain insufficiently explored, particularly for less-studied fermented fish products from different regions. There are also insufficient long-term studies on the stability of modified products using new preservation technologies. These gaps underscore the need for further interdisciplinary research to achieve a more holistic understanding of the field. Future research should focus on developing starter cultures optimized for specific fermentation conditions to minimize biogenic amine accumulation while enhancing the sensory and nutritional attributes of fermented fish products. Additionally, exploring natural salt substitutes, such as potassium chloride or yeast extracts, could address the pressing issue of sodium reduction without compromising product safety. Advanced preservation technologies, including active packaging materials, natural antimicrobial agents, and intelligent freshness indicators, hold significant promise for extending shelf-life and improving consumer confidence. Collaborative efforts among researchers, industry stakeholders, and policymakers are essential for overcoming the technical and economic barriers to implementing these strategies. By focusing on these innovative solutions, the fermented fish industry can better meet evolving consumer demands while maintaining its cultural and economic importance.

Li G was supported by the Taishan Scholars Program (Grant No. tsqn202306285) and Shandong Excellent Young Scientists Fund Program (Overseas) (Grant No. 2024HWYQ-077).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization, writing – review & editing: Li H, Zhu F, Li G; writing – original draft: Li H; supervision: Zhu F, Li G; funding acquisition: Li G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li H, Zhu F, Li G. 2025. Advancing safer and healthier fermented fish products through innovative processing strategies. Food Innovation and Advances 4(3): 293−303 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0029

Advancing safer and healthier fermented fish products through innovative processing strategies

- Received: 22 October 2024

- Revised: 29 March 2025

- Accepted: 31 March 2025

- Published online: 22 July 2025

Abstract: Fermented fish products are an integral part of the culinary heritage, celebrated for their unique flavors. However, these traditional foods face significant challenges related to safety and health, including biogenic amine accumulation, high salt content, and perishability during storage. This review synthesizes current research on addressing these issues through innovative approaches such as employing targeted starter cultures, optimizing fermentation parameters, and integrating advanced preservation technologies. Controlling biogenic amines, reducing sodium levels without compromising product quality, and extending shelf-life through natural preservatives and novel packaging methods are emphasized as key strategies. While promising, these approaches require further development to ensure feasibility and affordability for widespread application. The review underscores the importance of tailoring solutions to specific fermentation ecosystems and product types. By providing a roadmap for improving safety and health outcomes, this work aims to support the development of fermented fish products that balance cultural significance with modern consumer demands and health considerations.

-

Key words:

- Food safety /

- Salt reduction /

- Histamine /

- Microbial fermentation /

- Fish sauce