-

In living plants, bioactives like polyphenols, proteins, and polysaccharides are strictly confined in defined conformations within specific intracellular vesicles, following strict spatial and biochemical regulations[1−3]. These constituents are modulated by intricate biosynthetic pathways and are further influenced by the physicochemical parameters and environmental constraints[4−6]. Food processing generally disrupts plant tissue structure, leading to exposure and interaction of intracellularly segregated macromolecules[7,8]. Food processing releases polyphenols from vacuolar confinement, facilitating their binding to cell wall-associated proteins and polysaccharides. Meanwhile, the compromised integrity of cell membranes exposes intracellular constituents to oxidation, leading to adsorption, oxidation, solubilization, and migration[9]. The speed of oxidation is compounded by the activation of oxidases from thylakoid membranes[10]. The interactions throughout physical and chemical processing lead to the formation of structures of binary or ternary complexes and the acquisition of new biological functions.

The interactions between food nutrients occur inherently and efficiently within food matrices, encompassing processes including food processing, mastication, and gastrointestinal digestion. In recent years, in wine and juice production (Fig. 1 case 1), the release of polyphenols from tissues into beverages has been significantly affected by cell wall-polyphenol binding levels[11−13]. In the field of oenology, the importance of interactions between grape cell wall polysaccharides and polyphenols, with anthocyanins being crucial for the color of wine, has been systematically evaluated[14,15]. The pink discoloration in canned pear slices (Fig. 1 case 2) is attributed to cell wall-polyphenol interactions in the cellular matrix, which may cause the noted color change[16]. The degradation of pear procyanidins resulted in the formation of colorant anthocyanidins, which were subsequently associated with the cell wall structures[16]. The interactions were so robust that solvent extractions and enzymatic cell wall degradation failed to fully release the colorant. During food chewing, polyphenols have a significant impact on sensory attributes such as astringency and bitterness. For example, in Fig. 1 case 3, astringency arises from a complex interaction between salivary proteins and polyphenols, leading to the formation of insoluble complexes, reduced salivary lubrication, and a sense of dryness and constriction in the mouth[17−19]. Interactions between food nutrients not only affect the organoleptic properties of the food but may also alter the bioavailability of the nutrients, thus having a significant impact on the nutritional value and health effects of the food.

Figure 1.

The interactions in plant-based food systems. This figure illustrates the interactions formed between plant macromolecules through adsorption, migration, solubilization, and oxidation reactions during plant tissue processing treatments. Case 1 reveals the release of polyphenols from plant tissues and into beverages during the production of wines and juices, a process significantly influenced by the degree of polyphenols binding to the cell wall. Case 2 describes the interaction between procyanidins and cell walls, a key phenomenon that leads to pink discoloration in the canning of pear slices. Case 3 shows how salivary proteins are involved in the interaction of macromolecules in food during oral mastication. Case 4 illustrates the process of food in the digestive system and the interaction between polyphenols and gut microorganisms. The bottom of the figure shows the food sources, processing history, and applications of plant macromolecule interactions in food and how these macromolecules relate to regulating the gut microbial community.

The impact of food processing[20] on nutrients is critical throughout the food production cycle, from source to consumption. Plant-based foods, including fruits, vegetables, and grains, are abundant in polyphenols, polysaccharides, and proteins[21]. Food processing can alter the chemical composition and physical structure of plant macromolecules, as well as their physicochemical properties (e.g., softening of texture due to degradation of pectin[22] or browning due to oxidation of polyphenols[23]) and create opportunities for complex interactions within the food matrix[24]. In the production of wine and juice, the polyphenol content of fruits and vegetables is markedly decreased[25], leaving most polyphenols in the pomace, while some of the initially solubilized polyphenols precipitate during storage. However, by adding polysaccharides and proteins, the stability of polyphenols can be enhanced[26−28], thus improving the quality of the product. These processed foods play a role in regulating the gut microbiota after consumption. As shown in Fig. 1 case 4, the presence of interactions may affect the bioavailability of polyphenols in the human digestive tract[24, 29], which in turn affects the balance of the gut microbiota with its composition[30]. Conversely, gut microbiota can convert the insoluble and non-bioavailable polysaccharides and polyphenols into bioavailable metabolites (short-chain fatty acids, phenolic acids) known for beneficial health effects. Therefore, systematic elucidation of the changes and interactions of these complex components during processing can be effective in achieving precise processing of fruit and vegetable products and producing high-quality plant-based foods.

The aim of this review is to develop a practical, simplified, but unambiguous, and comprehensive graphical guide to this demanding topic, which is expected to promote the optimization of interaction experiments and analysis strategies. In addition, this research is also committed to providing a valuable reference for further exploration of the interaction between macromolecular substances in plants.

-

Preparation of plant macromolecule complexes (Fig. 2) includes selecting raw materials rich in the molecules of interest, pretreating via washing, drying, and grinding, extracting macromolecules with solvents, ultrasonic/microwave methods, and purifying through centrifugation, filtration, dialysis, chromatography[31,32]. Ultimately, binary complexes (e.g., protein-polysaccharide, protein-polyphenol, polysaccharide-polyphenol) or more complex polysaccharide-polyphenol-protein ternary complexes can be formed. Complex formation can be optimized by careful selection of pH, temperature, and time via non-covalent/covalent bonding and characterized using spectroscopic/chromatographic analyzes, leading to pilot and industrial-scale production based on lab-scale success[11,33].

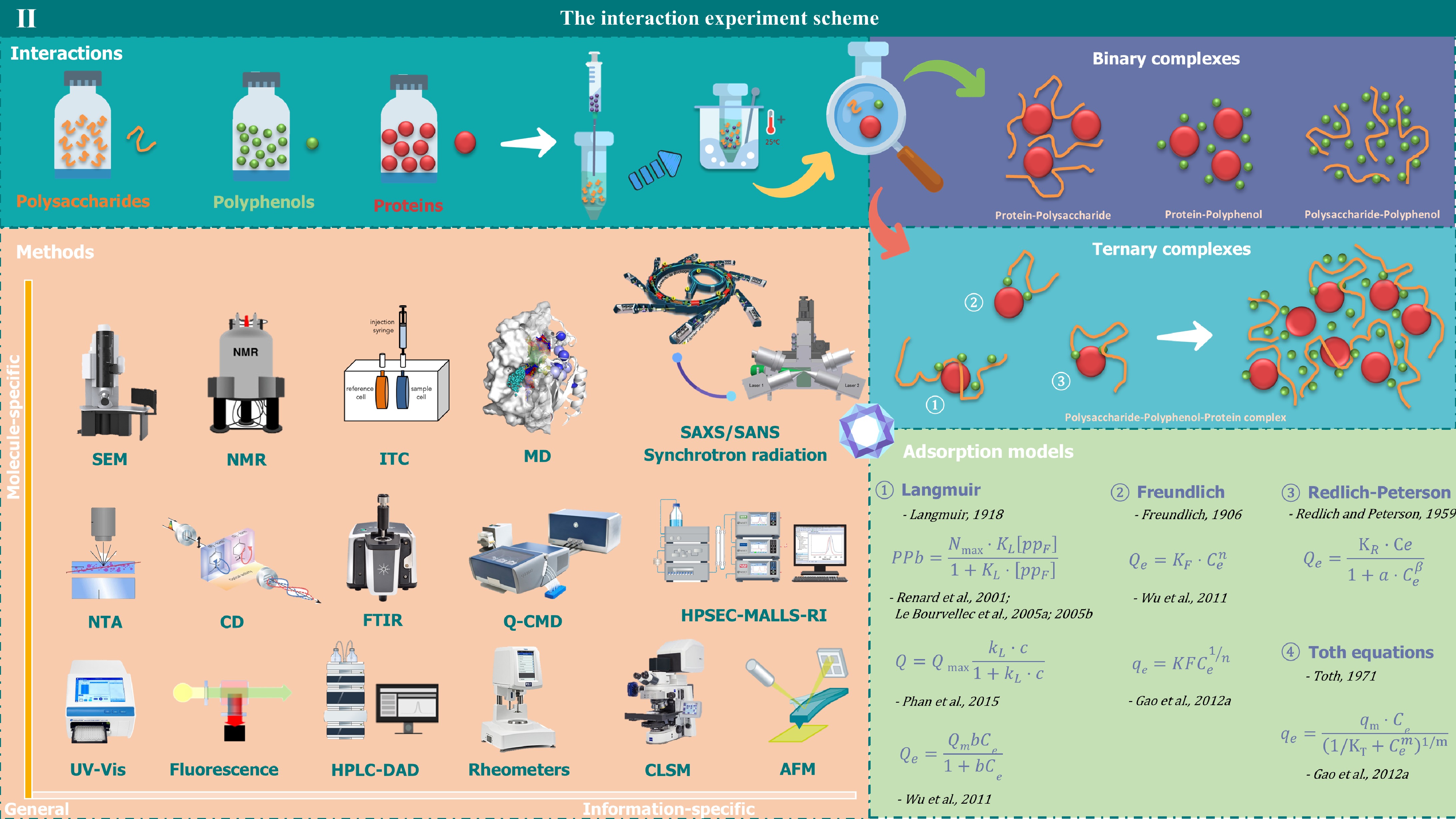

Figure 2.

The interaction experiment scheme. Under specific conditions, polysaccharides, polyphenols, and proteins can interact with each other to form binary or ternary complexes. In the initial state, these molecules exist as separate entities in solution. However upon mixing, they spontaneously interact and form complexes. After being heated in a water bath and with adjustments to environmental factors, these complexes can further interact with surrounding components, thereby constructing a complex and well-structured system. The figure displays the measurement methods for their interactions and the adsorption models. Interactions are measured by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), Molecular Dynamics (MD), Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA), Circular Dichroism (CD), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation Monitoring (Q-CMD), Ultraviolet-visible Spectroscopy (UV), Fluorescence Spectroscopy, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection (HPLC-DAD), Rheological Measurement Instruments, Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM), Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), Small Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS), Small Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS) and High-Performance Size-Exclusion Chromatography combined with Multi-Angle Laser Light Scattering (HPSEC-MALLS-RI) and Refractive Index detection. The adsorption models have Langmuir, Freundlich, Redlich-Peterson, and Toth equations.

Macromolecule binding can occur through covalent or non-covalent interactions, with covalent bonds being stronger and non-covalent weaker. Binding modifies the physicochemical and functional properties of interacting molecules[34,35]. Common methods of covalent binding plant macromolecules include physicochemical methods and enzyme catalysis. In the free radical grafting method, hydroxyl radicals are generated through the interaction of H2O2 and ascorbic acid. These hydroxyl radicals attack the hydroxyl, amino, and thiol groups in the protein molecule, leading to the formation of free radicals on the protein. These free radicals then react with the polyphenol molecules to form covalent complexes to realize the grafting of polyphenols on proteins. Polyphenol-polysaccharide conjugation is also induced by free radicals[36]. The free radical system includes Vc-H2O2, ceric ammonium nitrate, and potassium persulfate, which are used to promote polyphenol-polysaccharide covalent reactions[11]. Alkali treatments and enzymatic methods generate o-quinone primarily through the use of enzymes, free radical systems, or autoxidation (alkali + O2). This o-quinone then reacts with proteins. The o-quinone reacts with the nucleophilic groups of the protein to form C-N and C-S covalent bonds, forming a stable covalent complex[37].

The non-covalent interaction between polyphenols and polysaccharides or proteins can encompass a variety of forces, such as hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, and hydrophobic interactions. These interactions can be finely regulated by adjusting factors such as their concentration ratios and environmental conditions, which in turn affect the formation and stability of the complexes. The precise modulation of these non-covalent interactions involving plant macromolecules through dynamic and reversible processes is essential for cellular adaptation and the fulfillment of biological functions. Adjusting the concentration of reactants can significantly affect the efficiency and stability of the formation of complexes[38]. Under high concentration conditions, intermolecular interactions are enhanced, contributing to higher complex generation. Changes in temperature modulate intermolecular thermodynamic behaviour and interaction forces, including the robustness of hydrogen bonding. For example, heating proteins in advance can augment the stabilizing effects of anthocyanins[39]. During the construction of non-covalent complexes involving macromolecules, the pH of the solution affects the overall charge as well as the individual ionizing group charge, thus affecting the electrostatic interactions between the molecules. For example, measuring the affinity between polyphenols and proteins using calorimetry reveals an increased affinity when the pH is close to the isoelectric point of the protein[40]. The pH range is the main determinant affecting the interaction between cellulose and certain polyphenols, including cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, ferulic acid, and (+/−)-catechin[41,42]. During the formation of non-covalent complexes, the addition of salts or other ions modifies the ionic strength of the solution, thus affecting the shielding effect of the charges as well as the electrostatic interactions between the molecules[43]. In plant macromolecular complexes, differences in solvent polarity and dielectric constant affect intermolecular hydrophobic forces as well as hydrogen bond formation[44]. Therefore, recording or modulating these conditions is of high importance to modulate the non-covalent interactions and should be systematically reported in research articles.

Effects of different conditions

-

When studying the interactions between molecules, their original environment in the food, such as pH, inorganic salts, temperature, etc., should be simulated as much as possible. Under different conditions, they produce their own unique effects on the complex formation process. Dialysis removes low-mass impurities, shifting molecular weight distribution to higher masses for complex purification, potentially altering structure, solubility, stability, and bioactivity[45]. In the blending of plant macromolecules, key processing factors like temperature, agitation, and food matrix simulation are vital for intermolecular bonding and node creation[3,21,46]. The process may favor evolution from binary to ternary complex formation, producing high-performance, multifunctional plant composites through precise tuning of non-covalent and covalent interactions[47,48]. Temperature is a key parameter in polyphenol oxidation and complex formation, which plays an important role in affecting polyphenol oxidase activity, reaction rate, product distribution, enzyme stability, as well as complex formation and properties[49]. Appropriate temperature control is essential for optimizing product properties and improving preparation efficiency[38]. The hydrophobicity of polyphenols is positively correlated with their affinity for proteins, with higher solubility in water corresponding to weaker protein binding[50]. Conversely, lower hydrophilicity facilitates the formation of particles between polyphenols and proteins due to the fact that hydrophobic polyphenols are more inclined to aggregate, which promotes their interaction with proteins.

Reversibility of complexes

-

Reversibility of complexes refers to the fact that these complexes can be formed through the cooperation of non-covalent bonds and that these non-covalent bonds can be broken under the right conditions, allowing the complexes to be re-separated into their original macromolecular components[13,51]. To prevent the development of overly dense complexes, it is generally necessary to manage reaction conditions, alter the composition of the complex, or employ specialized processing techniques. By adjusting the reaction conditions, one can opt for a lower temperature to decelerate the reaction rate, thereby diminishing the formation of dense complexes[52]. Modifying the pH can affect the charge state of molecules, reducing electrostatic attractions, and reducing the ion concentration in the solution can diminish the screening effect of ions on intermolecular interactions[53]. Adjusting the ratio of polyphenols to polysaccharides[33] and incorporating specific chemicals can also help to minimize the formation of dense complexes. Specialized processing techniques, such as mechanical disruption[54] or chemical depolymerization[55], can disrupt the structure of the complex, allowing it to disintegrate.

Interaction detection methods

-

In order to delve deeper into the mechanisms of interactions between plant macromolecules, researchers have used a variety of measurement methods based on different principles. The information and outcomes derived from these approaches are mutually reinforcing, collectively offering a rich dataset that aids in deciphering these interactions. Figure 2 displays the measurement methods for their interactions and the adsorption models.

Thermodynamic measurements

-

Thermodynamic analysis is crucial for probing plant macromolecular interactions and assessing molecular forces via energy and system state changes. The technique of isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) has become the gold standard for studying molecular interactions in solution. ITC is a developed microcalorimetry method for measuring solution interaction metrics like binding constants. The binding parameters include the association constant (Ka), sites (n), and thermodynamic functions (ΔH, ΔS, ΔG)[56]. The entropy contribution (ΔS) and enthalpy change (ΔH) are mainly manifested in non-covalent interactions[21]. The application of ITC to plant macromolecular interactions suggests that such interactions typically involve hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding[57,58]. The binding free energy (ΔG) between non-pectin and pancreatic lipase is −8.79 kcal·mol−1, confirming the presence of non-covalent binding between them[59]. The enthalpy change ΔH for the interaction between persimmon tannin and inulin is −0.11 ± 0.02 kJ·mol−1, and the Gibbs free energy ΔG is −20.29 kJ·mol−1[60]. The negative values indicate a spontaneous and exothermic reaction. When different studies are compared with each other, differences resulting from the use of different computational bases are taken into account. The technique of differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analyzes a substance's thermal properties by measuring heat flow changes between the sample and reference during thermal cycling[61,62]. This technique focuses on the study of ligand-protein interactions[63]. DSC thermograms of gluten mixtures of apple pectin and citrus pectin showed a peak for pectin at approximately 245 °C, confirming that the pectin was not washing out of the gluten dough and interacting with gluten proteins[64]. Another application of the DSC technique is the ability to demonstrate a temperature profile of the melting temperature of a complex. The intensity of the heat flow signal of the olive phenolic compounds complexed with the apple cell wall exceeded the intensity of the apple cell wall alone. DSC analysis revealed significant changes within the complex due to the intervention of the olive phenolics under high-temperature conditions[65]. DSC methods are rapid, sensitive, and trustworthy but should be paired with other methods for more intricate molecular data.

Spectral measurements

-

The application of spectroscopy in the study of intermolecular interactions focuses on the interactions between biological macromolecules and small molecules. Turbidimetry was one of the first methods used to detect the interactions. These include fluorescence spectroscopy, UV-Vis spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and circular dichroism. UV-Vis spectrophotometry determines turbidity by measuring the loss of intensity of light as it passes through suspended particles[66,67]. Additionally, UV-Vis spectrophotometry enables the calculation of binding constants between macromolecules[68]. It also confirms interactions through changes in absorbance[69]. Polyphenols and polysaccharides do not normally absorb at 650 or 600 nm, which are usually chosen to measure turbidity[21]. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) technology can characterize changes in chemical bonds and functional group concentrations by collecting and analyzing infrared spectral changes of samples before and after interactions. It also reveals the types, strengths, and dynamic processes of intermolecular interactions by assessing the molecular microenvironment changes[70,71]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is an essential method for probing macromolecular interactions, allowing for exact mapping of binding locations, processes, site counts, and Kd values and linking structural shifts to biofunctions[72−74]. NMR spectroscopy can be used for structural analysis of plant components (e.g., proteins, polyphenols, polysaccharides, etc.), metabolite flux analysis, and understanding biosynthetic pathways[75,76]. NMR studies showed that the interaction between hesperidin and chitooligosaccharides could improve water solubility and antioxidant activity and also confirmed that the aromatic ring of hesperidin binds to chitooligosaccharides through hydrogen bonding[76]. Small Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS), Small Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS), and Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) with synchrotron light are powerful techniques for revealing nanostructural details by employing small-angle scattering to characterize biomacromolecular complexes in solution[77−79]. SAXS/SANS allows the study of solution structures in complexes, providing structural details of the solution. Using the SANS technique, the molecular structure of pea isolate proteins and dietary fibers in pasta processed at high temperatures was investigated, as well as the increase in molecular scattering distances due to substitution[80]. Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy is employed to assess secondary structure alterations due to biomolecule interactions, offering insights into the motifs and outcomes of their associations[81,82]. CD analysis showed that by studying the secondary structure of whey protein-pectin complexes formed by glycosylation, it was found that the glycosylation reaction altered the secondary structure of whey proteins and decreased the α-helix content[83]. This structural change in the spatial conformation of the protein resulted in a decrease in the hydrophobicity of the protein surface. Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) assesses the Brownian motion of particles for measurement of hydrodynamic diameter, serving as a robust method for aggregation research. It enhances DLS by offering greater resolution and the ability to track aggregate development.

Morphometric measurements

-

Morphology studies concentrate on high-resolution imaging and quantitative evaluation of a material's surface and internal architecture to expose its micro features and gauge surface integrity. In Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), an e-beam scans the sample's surface for sub-1-nm imagery, enabling visualization of solids regardless of thickness or conductivity, providing intricate surface morphologies of biomolecules like proteins and polysaccharides and their aggregates[84,85]. Silva et al.[86] observed a denser potassium network with smaller pores, suggesting less electrostatic repulsion between pea proteins and gellan gums; on the other hand, in the presence of calcium ions, the pores were larger, which could be attributed to interactions. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) surpasses SEM in resolution and magnification, ideal for analyzing material morphology and structure, yet it is restricted to ultra-thin samples (< 100 nm), offering 2D projections[87,88]. Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) captures sub-micron images for 2D/3D reconstructions but is limited for dynamic tracking due to slow scan speeds and lower resolution[89,90]. Fluorescent labeling of polyphenols or cell walls aids in interface visualization. Some polyphenols are autofluorescent in CLSM conditions, notably the phenolic acids, and can therefore be detected with minimal disruption of the natural structures. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) is used in the study of plant macromolecular interactions, primarily focusing on the structure and function of biomolecules and the forces between them[91,92]. With AFM, the three-dimensional morphology of plant macromolecules at the nanoscale can be observed, and the intermolecular forces can be measured. The AFM technique is able to reveal the high-resolution chain morphology of pectin or pectin complexes under absolute dry conditions, thus identifying structural features such as stretching, aggregation, branching states, and supramolecular assembly[93].

Indirect 'wet chemistry' methods

-

Indirect 'wet chemistry' techniques may not be able to directly describe the nature of the complex itself but can provide quantitative information on bound or free molecules. These methods offer adaptability for adjusting conditions, probing mechanisms, and altering structures to clarify structure-function relationships. However, they are limited by incomplete interaction mechanism exploration. Typically, the functioning of these techniques includes facilitating the interaction of macromolecules and subsequently isolating unbound polyphenols using filtration, equilibrium dialysis, or centrifugal separation. Subsequently, the separated unbound polyphenols are quantitatively analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography with a diode array detector (HPLC-DAD)[94], ultra-HPLC-DAD-mass spectrometry and/or spectrophotometry[21], gel permeation chromatography (GPC) [95,96], and high-pressure size exclusion chromatography (HPSEC)[97]to obtain structural information. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and gel exclusion chromatography confirmed the formation of covalent complexes, and the highest binding content of ferulic acid (FA) was achieved when the mass ratio of β-lactoglobulin (β-LG) to FA was 10:6[98]. The addition of FA significantly enhanced the emulsification properties of β-LG, revealing the effect of structural changes on the functional properties. Combining affinity and GPC with immunoassay techniques, pectinolytic enzyme treatment significantly altered the composition of polysaccharides in the range of 100−1,000 kDa and reduced polysaccharide content by 85−105 kDa and 1,050−6,000 kDa in Cabernet Sauvignon wines[99]. To date, the data collected using these methods are comparatively limited in quantity.

Modelling the interactions

-

The adsorption models for the interaction of plant macromolecules mainly focus on the adsorption behavior of macromolecules such as polyphenols, polysaccharides, and proteins at the interface (such as solid-liquid interface and solid-gas interface) in plants. These models are designed to explain and predict how these macromolecules interact with other molecules or surfaces and the effects of these interactions on plant physiological processes. Figure 2 summarizes the common adsorption models.

The Langmuir model is a classical theory that describes the adsorption of gas or solute molecules on a solid surface, assuming uniform adsorption, monolayer, dynamic equilibrium, and no intermolecular interactions[51,57,58]. The mathematical expression involves the relationship between surface coverage and adsorbate concentration, as well as the adsorption constants. In the study of plant macromolecules, the approach has been employed to explain adsorption behavior and to gain insights into the mechanisms of macromolecule-cell wall interactions. Additionally, it has been used to depict the adsorption process by fitting two key parameters, affinity and saturation, to experimental data[11].

The Freundlich model is suitable for describing the case of multilayer adsorption, where there are interaction forces between the adsorbed molecules[100]. The model is highly practical, particularly for depicting the adsorption of biomacromolecules on solid surfaces[101,102]. By fitting the Freundlich model with experimental data, the adsorption constant K and exponent n (constant related to adsorption strength, usually greater than 1) can be obtained, which can provide insight into the adsorption process and mechanism. Hasanvand et al.[103] depicted the adsorption behavior of Patulin (PAT) with Seleno-chitosan-phytic acid (Se-CS-PA) nanocomplexes by Langmuir and Freundlich models, and the data showed that the adsorption capacity was elevated with the increase of the initial PAT concentration. The adsorption process was consistent with the two models, revealing the mechanisms involved in the physical adsorption of multimolecular layers and the chemical adsorption of monomolecular layers[103].

The Redlich-Peterson equation is an empirical adsorption isotherm equation that is used to describe the adsorption behavior of a gas on a solid or liquid surface. The equation merges the features of both the Langmuir and Freundlich models, making it ideal for depicting multilayer adsorption scenarios with intermolecular interactions and heterogeneous adsorption sites. For example, Redlich introduces a power correction to the concentration but is, in fact, very close to Langmuir; this power allows us to better model a less flat plateau. In practical applications, the Redlich-Peterson equation is particularly valuable for describing the adsorption behavior of biological macromolecules on solid surfaces[104−106].

The Toth equation is an empirical adsorption isotherm equation that extends the Langmuir and Freundlich models to describe the adsorption behavior of gases on solid or liquid surfaces. The Toth equation considers the heterogeneity of the adsorption site and the characteristics of multilayer adsorption and is suitable for describing the adsorption behavior of biological macromolecules on solid surfaces[107]. By fitting the Toth equation with experimental data, the adsorption constants and exponents can be obtained, which can provide insight into the adsorption mechanism. In practical application, the Toth equation is helpful in optimizing the design of adsorbent materials and the improvement of adsorption processes and provides a theoretical basis for the design of biosensors[108,109].

The Langmuir model is suitable for adsorption in monolayers with a uniform surface, although it is based on the assumption of a perfectly uniform surface and does not take into account the phenomenon of multilayer adsorption, which makes the prediction inaccurate at high coverage[110]. The Freundlich model is used for adsorption on non-uniform surfaces and is applicable over a wide range of concentrations[100]. However, it is not suitable for describing all regions of adsorption isotherms, especially at low concentrations. The Redlich-Peterson equation is suitable for cases that exhibit both monolayer and multilayer adsorption characteristics[111]. However, the equation is complex, and the parameters are difficult to determine, making it less intuitive than simpler models. The Toth equation fits multilayer adsorption, accounting for surface saturation and secondary layers. However, it is complex with many parameters, requiring extensive data for calibration. Overall, the choice of model depends on the specific characteristics of the adsorption system and the support of the experimental data; different models are suitable for different adsorption scenarios and have their own advantages and limitations.

-

In some conditions, plant macromolecules in solution, such as polyphenols, proteins, and polysaccharides, exhibit weak interaction forces that are insufficient to overcome the thermal motion of the molecules themselves, preventing the phenomenon of intermolecular aggregation[112−114]. Therefore, as shown in Fig. 3 case 1, these macromolecules remain separate and dispersed in solution and do not form aggregates. Although non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobicity, and electrostatic interactions are prevalent between biomolecules, in this case, they are not strong enough to trigger molecular aggregation, preventing the formation of more complex structures[3]. Sometimes, there is encapsulation, e.g., with cyclodextrins, as the interactions give a less hydrophobic complex. As a result, the solution is maintained in a transparent state, showing a uniform distribution of molecules without the formation of any large particles or aggregates, ensuring homogeneity and stability of the solution[115,116]. This independent presence of molecules greatly facilitates biochemical reactions and material processing, as it promotes effective contact between reactants and a smooth progression of reactions.

Figure 3.

The proposed interaction mechanisms. Case 1 describes a non-covalent interaction between polysaccharide and polyphenol. Common non-covalent forces include hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and van der Waals forces. Non-covalent interactions lead to three possible consequences: maintaining a non-aggregated and soluble state, formation of aggregates leading to turbidity, and formation of insoluble precipitates. Case 2 describes a covalent interaction between polysaccharide and protein. The Maillard reaction, chemical cross-linking, and enzymatic covalent binding are the primary factors that determine covalent bonding between polysaccharides and proteins. This figure depicts the effect of thermodynamic quantization ((ΔH) and (ΔS)) on the interaction, and also depicts the physical constraints that act as regulators of interactions. Porosity and pore morphology have a major impact on macromolecular interactions in plants.

Formation of aggregates resulting in turbidity

-

When a solution becomes turbid, it indicates that aggregates (typically 1 micron or more) have formed but remain in suspension. In this particular case, the interaction forces between the plant macromolecules are at a moderate level, which is sufficient to induce aggregation of the molecules to form relatively small aggregates or particles[117,118]. As shown in Fig. 3 case 1, the size of these aggregates is moderate enough to have a scattering effect on light, which results in a cloudy appearance of the solution. These interaction forces consist primarily of hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and weaker electrostatic interactions[44,119,120]. These interactions induce molecular aggregation under specific circumstances, yet the size, density, and stability of these aggregates are insufficient for them to sediment to the bottom of the solution. As a result, these aggregates exist in solution in a suspended state, forming an unstable suspension system. The suspension state may arise as a consequence of alterations in solution parameters, including modifications in temperature, pH levels, or ionic concentration, influencing the equilibrium of interactions among macromolecules[121−123].

Formation of insoluble precipitates

-

Under certain conditions, the forces between plant macromolecules are significantly increased, leading to the formation of large and stable aggregates. As shown in Fig. 3 case 1, the density of these aggregates exceeds that of the solution itself, and thus, they gradually settle and eventually deposit at the bottom of the container, forming a visible precipitate. Such strong interactions may involve covalent cross-links[124−126], such as those formed via the Maillard reaction[127,128], or cooperative non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, ionic bonding, or hydrophobic interactions[129]. These strong interactions ensure the robustness and stability of the polymer structure, making it difficult to be broken down or redispersed under conventional experimental conditions. Thus, once precipitates are formed, they remain solid and resistant to dissolution and no longer dissolve in solution, even under gentle stirring or temperature changes. The irreversibility of such precipitates[130] is an important consideration in many areas of biochemistry and applied sciences, as it affects the handling, separation, and purification processes of the material.

The interaction between polysaccharides and polyphenols is a specific example of non-covalent interaction. Hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and van der Waals forces are common types of non-covalent forces (Fig. 3 case 1).

Hydrogen bonds

-

Hydrogen bonds are weak dipolar interactions involving hydrogen atoms interacting with highly electronegative atoms such as oxygen and nitrogen. Such interactions, although not as strong as covalent bonds, play an essential role in biological and chemical processes. Hydrogen bonding is one of the types of van der Waals forces. For example, polysaccharide molecules contain a large number of hydroxyl (-OH) or carbonyl (-CO) functional groups, which are key sites for hydrogen bond formation[131]. At low temperatures, these functional groups are able to form stable intra-chain networks within polysaccharide chains or inter-chain networks between different polysaccharide chains through hydrogen bonding. This network structure not only affects the conformation and stability of polysaccharides but also has a significant impact on their physical properties, such as viscosity and solubility[132]. By preparing quinoa protein nanomicelles and successfully loading hydrophobic flavonoids, the solubility, and stability of the latter were significantly enhanced, revealing hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding as the main intermolecular interaction forces[133]. The cell wall, through hydrogen bonding interactions between cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin, forms a structure that is both strong and flexible, giving the cell the necessary mechanical support and regulating its physical properties to adapt to growth and environmental changes[1].

Hydrophobic interactions

-

Hydrophobicity is a phenomenon in which water molecules repel non-polar molecules through a network of hydrogen bonds, causing them to aggregate with each other. The thermal stability of chlorophyll (Chl) was significantly improved by the addition of soybean isolated protein (SPI), which binds to chlorophyll to form a stable complex mainly through hydrophobic interaction. Hydrophobic interaction is the main driver of the binding between SPI and Chl, and this process is spontaneous and manifests itself as a negative Gibbs free energy change (ΔG < 0). This is further supported by the calculated positive enthalpy change (ΔH = 6.4208 kJ·mol−1) and positive entropy change (ΔS = 0.1124 kJ·mol−1·K−1) at 25 °C. When Chl interacts with SPI, the hydrophobic phytol residues of Chl enter and bind tightly to the hydrophobic ring of SPI, causing a conformational change that is highly consistent with the blue shift observed in the fluorescence spectra[134]. Dai et al.[44] found that the surface hydrophobicity of SPI decreased significantly with increasing concentrations of catechins, down to one-fourth of the original SPI value. Conformational changes and structural openings occurred when SPI interacted with catechins, resulting in the exposure of hydrophobic groups and the introduction of new hydrophilic groups (hydroxyl and carboxyl), which in turn decreased the surface hydrophobicity[44]. Liu et al.[135] found that the interaction of procyanidin DP79 with pectin is mainly driven by an increase in entropy due to hydrophobic interactions and water release, with entropy contributions ranging from −12 to −19 kJ·mol−1, and that the binding mode is complex and accompanied by significant exothermic reactions. Liu et al.[136] found that the enthalpy change contribution of arabinoxylan (AXLB) was larger (ΔH of −14 kJ·mol−1), suggesting that the interaction between procyanidins and pectin was mainly formed through hydrogen bonding. Meanwhile, the lower entropy change contribution of AXLB relative to other hemicelluloses suggests that hydrophobic interactions play a more critical role in the high-affinity interaction between pectin and proanthocyanidins[136].

Electrostatic interactions

-

Electrostatic interactions, also known as Coulomb interactions, are forces between charged particles that attract or repel each other due to the presence of electric charge. Polyphenols may exhibit binding selectivity for different polysaccharides of plant cell wall (PCW)[137]. For example, ferulic acid and anthocyanin-3-glucoside bind to PCW and cellulose with different degrees of affinity, suggesting that electrostatic interactions and cell wall microstructure play an important role in these bindings. Electrostatic interactions influence acid-induced hydrogel formation [138]. At pH below the isoelectric point (pI) of proteins (pI 4.0), proteins and xanthan gum form hydrogels via electrostatic interactions without the need for cross-linking agents. In contrast, at pH above pI (5.5), incompatibility between charged biopolymers increases, promoting soft hydrogel formation dominated by hydrophobic interactions, with electrostatic forces playing a secondary role. Electrostatic interactions improve the functional properties of plant proteins through the formation of a cohesive layer [139], including increased solubility near the isoelectric point, surface activity and stability, and controlled release of active ingredients. In addition, the cohesive layer masks the bitter flavor of plant proteins and helps in the preparation of meat substitutes.

Covalent interactions

-

Covalent bonding of polysaccharide-protein is mainly determined by the Maillard reaction, chemical cross-linking, and enzymatic covalent binding (Fig. 3 case 2).

Maillard reaction

-

The Maillard reaction is a complex reaction pathway that may result in covalent bonds between reducing carbohydrates and amino acids. The Maillard reaction involves monosaccharides and free amino acids; the mechanism extends to polymers but is poorly understood, and the results are observable but structurally poorly studied. In the early stages of the Maillard reaction, the carbonyl group in the polysaccharide reacts with the amino group in the protein by carbonylation to form an imine bond[140]. The imine bond reacts with other amino acid residues in the protein in a condensation reaction to form an amidine bond. The formation of these imine and amidine bonds prompts the formation of new covalent bonds between the protein and the sugar. As the reaction continues, these covalent bonds are further linked to form a cross-linked network structure, which affects the solubility, thermal stability, and mechanical strength of the protein. This reaction results in the formation of new macromolecules and has important implications for interfacial stabilization properties and nutritional value[141,142]. The Maillard reaction significantly improves the performance of biomolecules in stabilizing emulsions and enhancing functionality through covalent bonding[143], bringing more efficient and safer emulsifier options to the food industry.

Chemical cross-linking

-

Chemical cross-linking is the process of forming covalent bonds between two or more molecules or chains of macromolecules through a chemical reaction. This cross-linking can be either intramolecular or intermolecular. Polyphenol-polysaccharide conjugates are generally prepared using the 1-Ethyl-3-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl) Carbodiimide (EDC) method[144]. EDC can react with carboxylic acids to form highly reactive intermediates, which can react with amine/hydroxyl groups to form polyphenol-polysaccharide conjugates[145]. Polysaccharides or polyphenols without carboxyl groups need to be converted to intermediates before coupling[146]. The reaction is typically facilitated with the aid of N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) or hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt). NHS is known to enhance the production of conjugates by reducing ancillary reactions like the degradation of the intermediate, while HOBt serves to deter racemization[11]. Chemical cross-linking through graft copolymerization of chitosan (CS) with phenolic acids (PAs), the solubility, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and physical properties of chitosan-based films are significantly enhanced, thereby increasing their potential for food packaging film (PF)/coating applications[147]. Chemical cross-linking effectively enhanced the stability of egg yolk low-density lipoprotein (LDL)/polysaccharide nanogels in the gastrointestinal tract and improved their performance as an oral delivery system while maintaining particle size and morphology, decreasing surface charge, and enhancing the encapsulation and slow release of curcumin[148].

Enzyme activation

-

Enzymatic conjugation is a biochemical process in which enzymes act as catalysts to promote covalent binding between two or more molecules. In plant macromolecular interactions, this process can involve biomolecules such as proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids, as well as small molecule compounds such as polyphenols and fatty acids. Enhanced collagen-polyphenol binding strength by laccase activation improved the emulsification and antioxidant properties of the complexes, as well as their thermal stability and digestibility[149]. These results suggest that through enzyme-activated polyphenols, collagen can be used as a functional food ingredient in the food industry, providing new possibilities and improved directions for food processing and applications. For example, using polysaccharides and proteins as raw materials, hydrogels mediated by o-quinones have mild reaction conditions, high cross-linking efficiency, and low toxicity[150].

Physical constraints as modulators of interactions

-

Porosity and the morphology of pores significantly influence the interactions of macromolecules within plants, as depicted in Fig. 3. In the case of complexes, an encapsulation effect may be observed, where polyphenols are sequestered within the hydrophobic regions of a macromolecule. This inclusion can affect the macromolecule's specific organization, potentially acting as nucleation sites for structural changes. The relationship between cell wall polysaccharides (CPS) and polyphenols serves as a striking illustration. CPS displays a range of molecular structures, forms, sizes, and surface characteristics[1,2]. In general, pores are categorized into three sizes: large pores, having a pore radius (r) greater than 50 nm; mesopores, ranging from 2 nm to less than 50 nm in radius; and micropores, with a radius smaller than 2 nm[151]. Inside cell walls, the presence of micropores and mesopores is predominant, typically displaying pore diameters that fall between 3.5 and 5 nm[152]. The characterization of pores extends beyond their dimensions and may also be classified based on their geometric morphology. This classification encompasses various forms, including slit-shaped, spherical, fissure-type, conical, and columnar structures (Fig. 3). Insoluble CPS or cell walls show varying abilities to adsorb polyphenols based on pore shape, which can greatly affect the total amount adsorbed. For example, in the case of slit-shaped pores, polyphenol molecules are confined to adsorbing in a monolayer or a stacked arrangement. When the dimensions of the polyphenol molecules are less than the pore dimensions, they are capable of penetrating into the cavity of the polysaccharide matrix through surface diffusion or pore diffusion mechanisms[153]. Ultrasonic treatment enhances the contribution of surface diffusion to the total diffusion mechanism; increased porosity corresponds to a more facile diffusion process[154].

Quantification of thermodynamics

-

An ITC curve plots heat changes caused by interactions during substance titration into a solution at constant temperature. By examining the ITC curve, accurate measurements of ΔH and ΔS can be ascertained (Fig. 3). In ITC measurements, an exothermic peak indicates heat liberation due to ligand-receptor interaction, depicted as a negative peak on the curve. Its magnitude calculates ΔH, and its area correlates with moles bound[155]. The Van't Hoff equation is commonly utilized to ascertain the standard ΔH for a reaction by leveraging equilibrium constants that have been empirically determined across a range of temperatures. Different interactions affect ΔH and ΔS uniquely: van der Waals and H-bonds mainly contribute to binding enthalpy, while hydrophobic effects boost binding entropy[156,157].

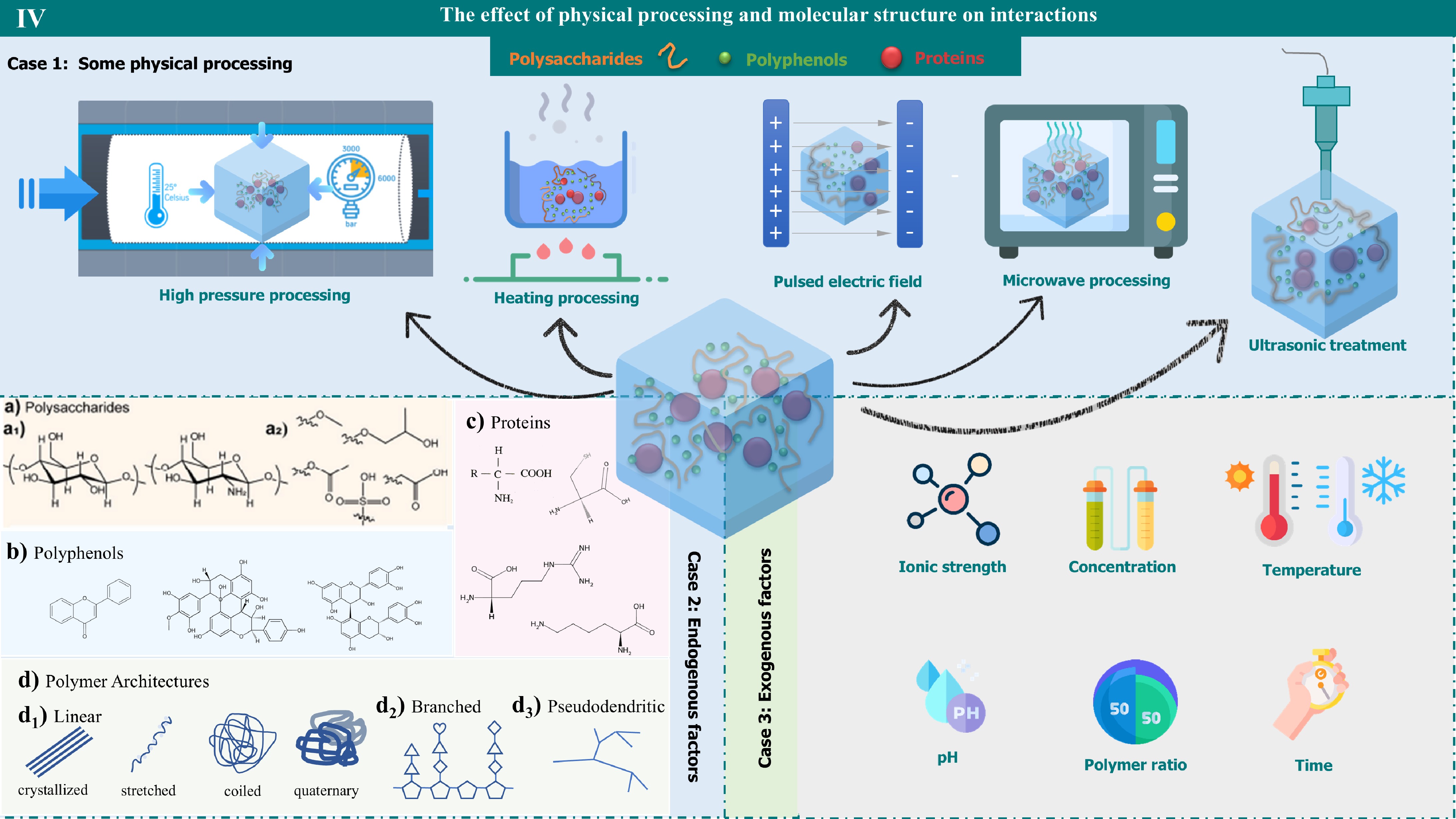

-

High-pressure processing (HPP) is widely used in the production of high-quality food products as a non-thermal food processing technology that uses 100 MPa or higher pressure and is able to process food while maintaining its original flavor and nutrients[158]. The reaction mechanisms of foodstuffs in high-pressure environments involve Le Chatelier's principle and the principle of microstructural rearrangement[159,160]. HPP alters the tertiary and quaternary structures of proteins, potentially leading to changes in their functional properties and stability[159]. HPP induces structural changes in the anthocyanin-protein (or multimeric enzyme) complex, thereby altering its stability and biological activity[161]. HPP can enhance bonding and influence the interactions between macromolecules by altering non-covalent effects. After HPP treatment (≤ 450 MPa), the resistant starch content was significantly increased, forming globular starch-protein-cell wall complexes, while dietary fibre composition remained unchanged[162]. The limitation of HPP is the inability to fully inactivate enzymes in industrial processing and storage, leading to oxidation and phenolic degradation, shortening shelf life[163].

Heating processing

-

In food processing, heat treatment is commonly used to change the nature of food, kill and inhibit microorganisms, and enhance food safety and shelf life. Under high-temperature processing conditions, various chemical reactions can occur and change the composition of the food. Heat processing alters the solubility of proteins in solution and affects their interactions with other molecules[164]. Whey protein-polysaccharide complexes prepared by dry heat treatment enhance the thermal stability of whey proteins in stabilizing emulsions[165]. Heat processing likewise alters the structure and solubility of polysaccharides[46]. Heat processing techniques can alter the structure of polyphenols and enhance non-covalent interactions between polyphenols and proteins or polysaccharides. Polyphenols may undergo isomerization, decomposition, and polymerization to produce novel compounds that typically carry a lower intensity of bitter or astringent flavor. Degradation of anthocyanins to aldehydes and benzoic acid derivatives at high temperatures and high pH significantly shortened their half-life with increasing temperature[166]. Heat treatment technology enhances the safety and stability of food products by altering the structure and interactions of proteins, polysaccharides, and polyphenols in food processing.

Mild pulsed electric field

-

Pulsed electric fields (PEF) are techniques that act on matter with brief, high-intensity electrical pulses. PEF technology is widely used in food processing, especially for fruit and vegetable juice extraction, offering benefits like safety, stability, freshness, speed, low temperature, and energy savings[167]. PEF technology enhances the bioaccessibility of carotenoids and phenolics in carrots via cell membrane modification[168]. PEF treatment increases rice bran protein extraction by 20.71%–22.8% when applied at 2.3 kV for 25 min, improving functional properties such as oil retention and emulsification while maintaining the molecular weight and amino acid composition unchanged[169]. It also improves foaming, digestibility, and radical scavenging, validating PEF as a protein extraction optimizer. PEF can electroporate cell membranes, thereby increasing extraction rates and reducing the degradation of heat-sensitive compounds in the sample[170]. PEF and mild heat treatments significantly affect the pectin extraction rates and ionic cross-linking in carrots, potentially maintaining tissue texture during cooking processes[171]. PEF technology, due to its unique non-thermal characteristics and efficient, energy-saving processing features, shows great potential in the field of food processing.

Microwave processing

-

Microwave technology refers to the use of microwave energy for heating, cooking, sterilizing, drying, puffing, thawing, and processing food. This technology utilizes the unique penetrating power and rapid heating properties of microwaves to achieve a variety of processing objectives in the food industry[172]. Microwave extraction technology enables precise and rapid extraction of active ingredients while ensuring the stability of heat-sensitive ingredients[173]. Microwave extraction technology can promote the rapid diffusion of plant polyphenols to the solvent, thus reducing the adverse effects of high temperature on the oxidative properties of polyphenols. Microwave-assisted extraction was used to obtain polyphenols from chestnut shells, and the results showed that the aqueous extract contained the highest total phenolic content and the most antioxidant capacity[174]. Microwave treatment enhanced the stability and activity of polysaccharide nanoparticles and improved the stability and plasticity of the emulsion[175].

Ultrasonic treatment

-

Ultrasonic treatment in the food industry is defined as a technology that uses the mechanical vibration and cavitation effects of ultrasound[176] to change the physical and chemical properties of food or to extract useful components from food. Ultrasonic cavitation occurs when ultrasonic vibrations in a liquid create alternating high and low-pressure areas, causing tiny bubbles to form, grow, and eventually burst[177]. This process generates very high (and concentrated) pressures and extreme temperatures. Ultrasound changes the structure of proteins through acoustic chemical and acoustic mechanical effects, affecting their function, and can be used as a support material in microsphere formation, while enzymes need to be protected from acoustic waves to maintain catalytic efficiency[178]. Ultrasonic technology primarily alters the conformational structure of proteins to enhance the emulsifying properties of peanut proteins[179]. Ultrasound treatment intensifies glycosylation, thereby increasing the hydrophobicity of protein-polysaccharide complexes[180]. The extraction of polyphenols from mango was assisted by ultrasonic technology, which successfully preserved the integrity of their antioxidant functions. Ultrasound technology accelerates the ageing process of wines, thus shortening their production cycle[181].

Molecular structure

Polysaccharides

-

The structure of polysaccharides influences the interactions of plant macromolecules (Fig. 4 case 2a). Polysaccharides are complex molecules formed by the interconnection of numerous monosaccharide units through glycosidic bonds. The diversity of these molecules is seen in monosaccharide types, connection modes (functional groups and stereochemistry), and molecular weight variations. The molecular structure of arabinoxylan influences the interaction between pectic polysaccharides and polyphenols[69]. Pectin has a high affinity for polyphenolic compounds[21]. Reticulated pectin binds proanthocyanidins more efficiently, whereas cellulose and reticulated xyloglucan exhibit higher apparent saturation due to structural features[57]. Removal of cell wall material from pectin reduced the binding capacity for proanthocyanidins. The open structure of pectin provided more binding sites, whereas differences in pectin content in the cell wall affected the adsorption capacity of different tissues for proanthocyanidins. In CPS-polyphenol interactions, cell wall porosity and surface area are key factors affecting polyphenol adsorption[21]. Physical modifications such as different drying methods can significantly change these properties, which in turn affect the adsorption effect. It has been shown that the molecular weight of polysaccharides influences their interaction with polyphenols, but structural properties and composition are also crucial, and the presence of side chains may hinder adsorption. The binding capacity of polysaccharides to polyphenols can be improved by modifying them. The interaction of pectin with polyphenols showed significant differences depending on the degree of acetylation. When the degree of acetylation of pectin was reduced, the number of surface-available dissociated galacturonic acid residues (COO-) and hydroxyl groups increased, which contributed to the aggregation of anthocyanins on the pectin surface[21]. The structural complexity and modification of polysaccharides, such as pectin, significantly affect their interaction with polyphenols, with factors like molecular weight, branching, and acetylation playing key roles in determining adsorption capacity.

Figure 4.

The effect of physical processing and molecular structure on interactions. It reveals how the physical treatment steps and molecular structure affect the interactions. A variety of physical treatment techniques, including high-pressure, heating, pulsed-electric fields, microwaves, and ultrasound, are demonstrated. In addition, the role of molecular structure in interactions can be divided into two main categories: endogenous and exogenous. Endogenous factors involve the structural properties of polysaccharides, polyphenols, proteins, and polymer architectures, while exogenous factors include the effects of ionic strength, concentration, temperature, pH, polymer ratio, and time.

The structure of natural polymers is inherently linked to their interaction with plant macromolecules, as depicted in Fig. 4 case 2d. Polymer structures are classified as linear, branching, and pseudo-dendritic. Linearly structured polymers can exhibit different morphologies, such as crystallization, stretching, curling, and the formation of quaternary structures. The specific sequence and spatial arrangement of linear polymers can specifically recognize and bind to polysaccharides, proteins, and other macromolecules in the plant cell wall, thereby affecting the structure and function of the cell wall[182]. The affinity of linear pectin for proanthocyanidins is greater, as demonstrated through comparisons of plant sources and across various extraction conditions[135]. In the case of branched polymers, their structure allows for an increased surface area, which can enhance cross-linking between the polymers themselves and with other cell wall components[183,184]. This structural feature also plays a role in regulating the porosity of the cell wall, which is essential for its mechanical strength and permeability. The type of natural polymer, therefore, directly influences the nature of these interactions and the resulting impact on the plant cell wall's integrity and function.

Polyphenols

-

Polyphenols are a class of secondary metabolites that are widely found in plants and have a structure in which one or more hydroxyl groups are directly attached to an aromatic ring. The structure of polyphenols influences the interactions of plant macromolecules (Fig. 4 case 2b). The greater the number of hydroxyl groups in a polyphenol molecule, the stronger its interaction force with other macromolecules, as more hydroxyl groups can form hydrogen bonds[185]. The position of the hydroxyl group on the aromatic ring determines the redox properties and spatial configuration of the polyphenols, and these factors influence the mode of binding of polyphenols to plant macromolecules[186]. The type and position of the substituent group can affect the hydrophobicity and polarity of polyphenols, which in turn affects their interaction with plant macromolecules. For example, glycosylation can increase the solubility of polyphenols, making them more likely to interact with cell wall components. The high reactivity of polyphenols and the large number of reactive sites make it imprecise to accurately characterize and quantify their interactions with food components[38]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop specialized pre-treatment techniques that will help improve analytical accuracy. Meanwhile, in combination with advanced analytical techniques such as ITC and SAXS, interactions can be more accurately detected and quantified, providing a deeper understanding of polyphenol effects.

Proteins

-

The structure of proteins has a profound effect on the nature and efficiency of their interactions with plant macromolecules (Fig. 4 case 2c). Polyphenol-binding proteins are characterized by their high content of basic residues, significant levels of proline, considerable molecular size, hydrophobic nature, and inherently flexible and open conformational structure[187]. In the binding of whey isolate proteins to polyphenols, it was found that this process enhances the antioxidant properties and thermal stability of polyphenols and simultaneously reduces their surface hydrophobicity[186].

-

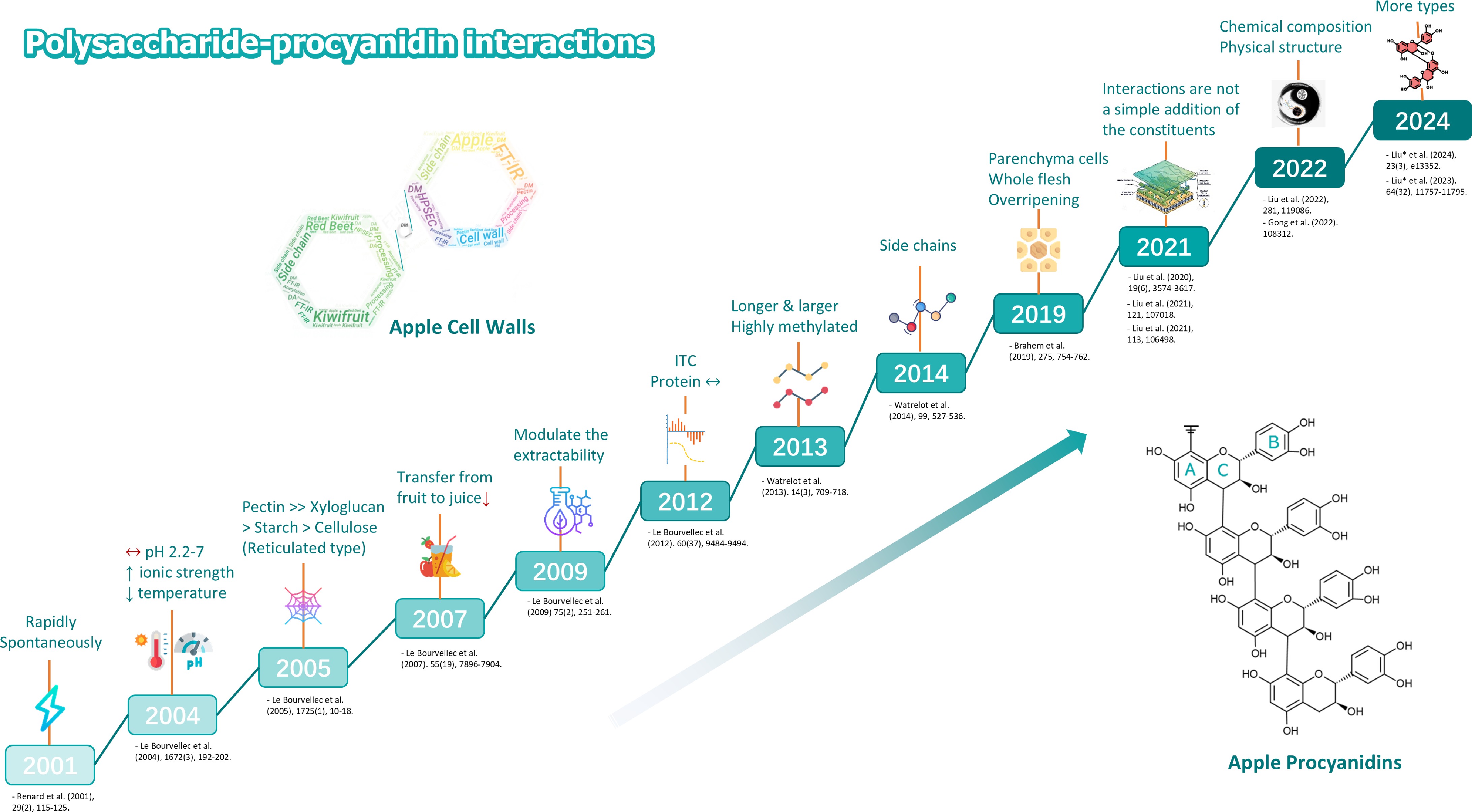

Weak interactions between plant intracellular polyphenols and cell walls have long been recognized by practitioners, but until the late 1990s, it was difficult to analyze procyanidins and quantify the phenomena. This was also due to the low affinity of cell wall-polyphenol complexes, making them difficult to quantify. However, with the arrival of new analytical methods and adequate models, it became possible to advance in this area. Research on the interaction between apple cell walls and procyanidins has seen significant advancements from 2001 to 2024 (Fig. 5). In the seminal study by Renard et al.[51], it was observed that apple procyanidins spontaneously and immediately attach to cell wall material (CWM) derived from apples. Procyanidins were found to bind weakly but rapidly to cell walls, with a higher binding affinity observed at higher molecular weights. Subsequent studies, in particular, the work of Le Bourvellec et al.[13] and Le Bourvellec et al.[188], showed that pH and ionic strength affect their non-covalent interactions and polysaccharide extraction yields. The assembly of complexes involving procyanidins and CWM remained unchanged across a pH spectrum from 2.2 to 7[13]. The adsorption rate rose in correlation with higher ionic strength and fell as the temperature rose. The procyanidins mainly bind to pectins, restricting their depolymerization[188]. Furtherstudies by Le Bourvellec et al.[57], Watrelot et al.[190], Watrelot et al.[191], and Brahem et al.[192] have detailed the specific binding affinities and mechanisms of the different polysaccharides, as well as the effects of fruit maturity and tissue type. Le Bourvellec et al.[58] studied the adsorption of procyanidins on solid polysaccharides, taking into account the effects of polymerization and galloylation degrees. The binding affinity of polysaccharides is ranked as follows: pectin >> xyloglucan > starch > cellulose. Watrelot et al.[190] and Watrelot et al.[191] conducted research on interactions between procyanidin and specific pectin substructures, revealing that DP30 tannins have a greater affinity for highly methylated pectin compared to DP9. They also found that the binding to pectin's hairy regions is influenced by sugar side chains, with DP30 binding more strongly, aggregating more; this is correlated with the content of arabinan and galacturonic acid[191]. Brahem et al.[192] demonstrated that maturity and tissue type of pear pulp affect procyanidin-cell wall interactions, with higher adsorption of highly polymerized procyanidins by overripe pulp cell walls.

Figure 5.

As an example: Cell wall polysaccharide-procyanidin interactions. At beginning study by Renard et al.[51], the apple cell walls experiences immediate and automatic attachment to procyanidins originating from apples. Le Bourvellec et al.[13] explained that environmental factors (pH, ionic strength, temperature) affect the non-covalent interactions between procyanidins and apple cell walls. Le Bourvellec et al.[58] studied the adsorption of procyanidins on cell walls, taking into account the effects of polymerization degree. Le Bourvellec et al.[43] explored the interaction between apple procyanidins and cell walls and its role in the transformation from the fruit state to the juice phase. Le Bourvellec et al.[188] identified that the interaction of procyanidins with the cell walls influences the yield of polysaccharide extraction. Le Bourvellec et al.[189] examined how the cell wall composition and structure of apples influence the binding of procyanidins. Watrelot et al.[190] examined the interaction between procyanidins and pectin using isothermal titration calorimetry and turbidity analysis, focusing on the impact of pectin methylation and side chain length. Watrelot et al.[191] revealed that the binding of procyanidins to pectin's hairy regions depends on the neutral sugar side chains' makeup and structure. Brahem et al.[192] investigated that maturity and tissue type of pear pulp affects procyanidin-cell wall interactions, with higher adsorption of highly polymerized procyanidins by overripe pulp cell walls. Liu et al.[136] was conducted to evaluate the interaction properties between xylose-containing hemicelluloses and procyanidins. Liu et al.[193] investigated that the total interactions are not a simple summation of different component interactions. Physical factors are as important as chemical ones for interaction[193]. They[194,195] also summarize the physicochemical and structural changes of A-type proanthocyanidins during extraction, processing and storage. Future work would be devoted to the interaction between more types of polysaccharides and polyphenols.

Le Bourvellec et al.[43] explored the interaction between apple procyanidins and cell walls and its role in the transformation from the fruit state to the juice phase. The Langmuir model with refined CWM and procyanidins explains a 60%−90% loss in apple-to-juice conversion[43]. Le Bourvellec et al.[189] investigated the manner in which the composition and structure of apple cell walls affect the binding of procyanidins. This study found that protein content did not affect procyanidin binding, while pectin had a strong interaction with procyanidins, and the binding process was mainly entropy-driven[189]. Le Bourvellec et al.[16] showed that the pink discoloration of canned pears is related to pH and degradation of condensed tannins and that condensed tannins may form stable covalent bonds with the cell wall, making extraction difficult. The previous studies revealed that the interaction of tannins with the cell wall during the processing of apples and pears had a significant effect on juice quality and color changes.

The study by Liu et al.[196] investigated how cell wall structure and pH affect cell wall modification and polysaccharide solubilization in different plant sources by simulating fruit and vegetable processing. Their study highlights cell wall response variations at different pH levels and explains sugar degradation mechanisms[196]. Liu et al.[135] further refined the factors dependent on the binding of procyanidins to pectin, including the structure and size of the pectin and the degree of polymerization of procyanidins. It provides a basis for understanding the strength of procyanidin binding to the cell wall under specific conditions. They extend these findings by exploring the binding properties of procyanidins to the cell walls of different plants, emphasizing the influence of cell wall structure and composition on the binding capacity[193]. The study notes differences in procyanidin adsorption between original and altered cell walls, highlighting key structural features[193]. Liu et al.[136] also studied interactions between xylose-containing hemicelluloses and procyanidins. They clarified how different hemicelluloses bind to procyanidins and their preference for high DP procyanidins[136]. They[194,195] also summarize how A-type proanthocyanidins change in physicochemistry and structure during extraction, processing, and storage. Future work would be devoted to the interaction between more types of polysaccharides and polyphenols. The entire research timeline demonstrates a progressive and in-depth exploration of the effects of environmental factors, cell wall composition, polysaccharide type, maturity and tissue type, and cell wall structure on proanthocyanidin binding, beginning with the initial discovery.

-

This review provides insights into the complex mechanisms of interactions between plant macromolecules and their impact on food properties and health benefits. Interactions between plant macromolecules are mainly categorized into two types: non-covalent and covalent. Non-covalent interactions are commonly characterized by hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, and van der Waals forces, whereas covalent interactions are mainly realized through the formation of covalent bonds. By comprehensively analyzing the effects of experimental protocols, assay methods, and processing factors, it was found that food components not only form stable complexes with each other but also affect their solubility, stability, bioactivity, and interactions with the intestinal microbiota. These findings provide an important theoretical basis for optimizing food processing, improving food quality, and developing functional foods. In the future, as research into food ingredient interactions continues, it will be possible to predict and optimize these interactions more accurately and develop more foods and nutritional supplements with health benefits. In the future, more technological tools should be integrated to probe deeply into the interactions among plant macromolecules. In addition, comparison and validation of the results of in vitro digestion models using different animal and cellular models would assist in gaining a deeper understanding of the bioavailability of the complexes.

In conclusion, this graphical review is intended to assist researchers involved in the challenging task of food component interactions and appeal to others in the field, contributing to their learning curve by adopting the graphical guides and the resources collected here as essential knowledge to enter this field of interaction.

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32202022), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2025A1515010497), Hong Kong Scholars Program (XJ2023050).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: literature research, Writing - Original Draft: Xue Y; field experience and critical review of the manuscript:Renard CMGC, Le Bourvellec C, Hu Z, Liu X; validation, formal analysis: Zhao L, Wang K, Wu JY; funding acquisition: Hu Z, Liu X; conception, visualization, methodology, editing of the manuscript, project administration: Liu X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xue Y, Le Bourvellec C, Renard CMGC, Zhao L, Wang K, et al. 2025. Food component interactions: a hitchhiker's guide. Food Innovation and Advances 4(3): 304−320 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0027

Food component interactions: a hitchhiker's guide

- Received: 26 November 2024

- Revised: 22 February 2025

- Accepted: 26 February 2025

- Published online: 23 July 2025

Abstract: The interactions between food nutrient constituents/matrixes (e.g., polysaccharides, proteins, and polyphenols) carry on spontaneously and rapidly in the food system (e.g., processing, chewing, and digestion). Understanding the variability of these interactions throughout the food chain/industry in terms of patterns and mechanisms is a challenging task, as the structures of these biomolecules are highly complex, and the binding forms and sites are quite flexible, which hinders their accurate identification and analysis. The comprehensive attribution of modern physical analysis techniques presents enormous strengths: it reveals the chemical composition and physical structure of components, the way in which they interact, their influence on matrix properties, and paves the way for other and more complex interactions in food systems. The aim of this review is to develop a practical, simplified, but unambiguous and comprehensive graphical guide to this demanding topic. It might advance the strategies applied to interaction experiments and analyzes, pinpointing the key home messages disclosed by each representation and proposing effective explanations for their mechanisms of interaction, as well as other key resources in the investigation of these biomacromolecular interactions.

-

Key words:

- Biopolymers /

- Polysaccharides /

- Polyphenols /

- Proteins /

- Food chains /

- Nature