-

Consumers favor kiwifruit for its premium taste, nutritional advantages, and appealing sensory characteristics. Notably, the Vitamin C concentration in kiwifruit pulp surpasses that found in most other fruits, further contributing to its popularity[1]. The global kiwifruit industry has experienced rapid growth and has become a commercially significant fruit on an international scale[2]. Kiwifruit is a typical climacteric fruit that usually requires a period of ripening after purchase before it becomes edible. However, kiwifruit that has undergone cold storage or treatment with preservatives may exhibit "zombie fruit" issues, where the fruit remains hard or decays soon after softening (quick overripening), significantly diminishing consumer confidence. "Ready-to-eat kiwifruit" refers to fruit that can be consumed immediately after purchase without additional ripening, which offers uniform flesh maturity with enhanced taste and flavor, allowing consumers to enjoy it right away. The market for ready-to-eat kiwifruit has grown considerably in recent years. The development and technologies for ready-to-eat kiwifruit are crucial for enhancing the quality of such industries, offering both practical benefits and economic value[3].

The application of plant growth regulators (PGRs) throughout cultivation affects fruit formation at various stages of plant development. This method helps regulate growth, boost stress resistance, enhance product quality, and guarantee stable crop yields[4]. Forchlorfenuron (CPPU), which is known chemically as 1-(2-chloropyridin-4-yl)-3-phenylurea, is classified as a phenylurea-based plant growth regulator. CPPU promotes fruit enlargement by enhancing cell division and expansion[5], including fruits like kiwifruit, watermelon, apples, grapes, and macadamia nuts[6]. CPPU is registered in numerous countries, and is extensively applied in the cultivation of kiwifruit[7]. It has been shown that applying CPPU to kiwifruit through spraying or dipping at concentrations of 5–20 mg/L after full bloom can effectively boost kiwifruit yield[8]. Ainalidou et al.[9] examined the impact of CPPU on Hayward kiwifruit under varying pollination conditions, and demonstrated that under favorable pollination conditions, CPPU effectively enhances the quality of kiwifruit products. Luo et al.[10] demonstrated that CPPU affects the photosynthesis core complex protein-coding genes' expression in kiwifruit. Although the application of CPPU can substantially increase kiwifruit yield[11], its effects on the quality of the edible period of ready-to-eat kiwifruit have not yet been documented, and its influence on both the shelf-life and the palatable qualities of ripe kiwifruit remains unclear.

This study utilized Xuxiang kiwifruit as the experimental material to investigate how CPPU treatment influenced shelf-life, quality indicators, enzyme activity, cellular structure, and metabolite composition during storage. The aim was to elucidate the underlying mechanisms through which CPPU affects the quality and storage duration of ready-to-eat kiwifruit.

-

The CPPU treatment process was conducted in a cooperative orchard located in Meixian County, Shaanxi Province (China). Immature Xuxiang kiwifruit after 20 days of pollination were immersed in CPPU (China Yangling Meiguo Biotechnology Co.,Ltd, China) at a recommended concentration of 10 mg/L for 2–3 s per sample, which was considered as the experimental group (EG). Samples without any treatment were considered as the control group (CG). Throughout the experiment, standard agronomic practices were employed in managing the plants, and there were no records of extreme weather events.

In early September 2023, kiwifruit were randomly selected and harvested from the vine, then transported to the laboratory within 24 h. Upon arrival, the kiwifruit were left at room temperature for 24 h before analysis. Two hundred regularly shaped, undamaged fruits were selected as experimental samples for each group. The storage of samples was conducted at room temperature, specifically at 24 ± 1 °C. During the storage period, kiwifruit were tested every 2 d.

Size and weight of kiwifruit

-

Kiwifruit size was determined using a Vernier caliper (Model 111-504, Sanzumi Co., Ltd., Japan). Ten kiwifruits were randomly chosen to calculate the average length, width, and height[6]. The average kiwifruit weight was determined with an electronic balance (Model YP10002, Shanghai Youke Instrumentation Co., Ltd., China), taking random 10 kiwifruit for the measurements.

Quality attributes of kiwifruit

Firmness

-

A digital fruit firmness tester (model AipliGY-4, manufactured by Quzhou Aipu Metrology Instrument Co., Ltd., China) was used to assess kiwifruit firmness. The measurement was conducted with an 8-mm diameter probe configured to exert a downward pressure to a depth of 10 mm. Measurements (N) were taken after peeling the equatorial region of each selected kiwifruit[12].

Total soluble sugars

-

A hand-held Brix meter (Model DIFLUID-002, Shenzhen Flow Counting Technology Co., Ltd., China) was employed to measure the total soluble sugars (TSS) in kiwifruit. After the juice had been extracted, it was centrifuged, and the resulting liquid was measured to determine the TSS.

pH

-

A portable pH meter was used to assess the pH (Model Testo 206 pH2, Dettol Instruments Shenzhen Co., Ltd., China), using the centrifugally separated kiwifruit juice.

Soluble solid content

-

To measure the soluble solid content (SSC) of the kiwifruit, a hand-held refractometer (Model RF001, Shenzhen Dee Times Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., China) was used, using the centrifugally separated kiwifruit juice[13].

Respiration intensity

-

To measure the respiration intensity (RI) of kiwifruit, a fruit and vegetable respirometer (Model 3051H, Hangzhou Greenbo Instrument Co., Ltd., China) was used. Each kiwifruit was placed inside a 2-L respiration chamber, and measurements were recorded at every 5 min, for a total of 10 readings. The average of these readings was calculated to determine the kiwifruit's RI.

Weight loss rate

-

The weight loss rate (WLR, in %) is based on the fresh weight of kiwifruit during storage and is calculated as follows[14]:

$ \rm{W}eight\; loss\; rate\; (\text{%})=\dfrac{\mathrm{I}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\; \mathrm{w}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{t}-\mathrm{Fi}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\; \mathrm{w}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{t}}{\mathrm{I}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\; \mathrm{w}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{t}}\times100 $ Dry matter

-

To evaluate the dry matter (DM) composition in kiwifruit specimens, thin sections approximately 2–3 mm in thickness were excised from the equatorial region of each fruit, and their initial mass was recorded. The prepared samples were subsequently oven-dried at 70 °C for 12 h to a constant weight. The DM content (%) was calculated using the ratio of the dehydrated sample mass to the fresh weight[15].

Vitamin C (Vc)

-

Vc levels in kiwifruit were analyzed according to the method described by Xu[16].

Enzyme activities

-

The kiwifruit was peeled and an appropriate amount of pulp was used for subsequent experimental measurements. Several enzyme activities were examined strictly in accordance with the Solarbio assay kit methods.

Catalase

-

The activity of catalase (CAT) was assessed on the basis of absorbance at 405 nm. One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that degrades 1 μmol of H2O2 per minute per gram of tissue, with the results presented in U/g.

Superoxide dismutase

-

The activity of the superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme within the reaction system was evaluated according to the absorbance reading at 560 nm. Enzyme activity was quantified as U/g when the reaction system's inhibition rate reached 50%.

Peroxidase

-

The enzyme activity of peroxidase (POD) was determined through measuring the absorbance at 470 nm at both 30 and 90 s. An increase of 0.005 in absorbance at 470 nm per minute, normalized per gram of tissue and per milliliter of reaction mixture, was regarded as one unit of enzyme activity and was quantified as U/g.

Polyphenol oxidase

-

The absorbance measurement of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) was conducted at 410 nm. An increase of 0.005 in the absorbance of the reaction system was equivalent to one unit of enzyme activity, which was denoted as U/g.

Alpha-amylase

-

The production of 1 mg of reducing sugar per minute per gram of tissue, as determined by the absorbance measured at 540 nm, was defined as one unit of alpha-amylase (α-AL) enzyme activity and expressed as U/g.

Starch, protopectin, and malondialdehyde content of kiwifruit

-

The starch, protopectin and malondialdehyde (MDA) content of kiwifruit were determined strictly in accordance with the Solarbio assay kit method.

Starch

-

The absorbance measurement was performed at 620 nm and are presented in units of mg/g.

Protopectin

-

The absorbance measurement was performed at 530 nm, and the results are presented using μmol/g as the unit.

MDA

-

The absorbance measurements at wavelengths of 450, 532, and 600 nm were recorded and reported in units of nmol/g.

Microstructure

-

The kiwifruit pulp was immediately placed into a fixative solution and maintained there for at least 24 h at room temperature. After that, the tissue was removed from the fixative within a fume cupboard. Using a scalpel, we carefully selected and flattened the desired portion of the tissue. Then the prepared tissue was placed into an embedding frame for further processing. The embedding frame was placed neatly into a dehydration box for dehydration sequentially. The wax blocks were initially cooled at −20 °C on a freezer table for several minutes, and they were then transferred to a paraffin slicer and processed into slices with a thickness ranging from 2 to 5 µm. These tissue sections were then placed in a warm water bath at 40 °C to facilitate their spreading. Once spread, the slices were carefully transferred onto slides and placed in an oven set to 60 °C to bake. This process allowed the water to evaporate and the wax to solidify, after which the slides were removed and prepared for staining. Plant tissue sections were washed using a staining solution for 3–6 min, and were examined using a microscope. Vegetative tissue sections were placed in the staining solution for 1–5 min and washed with 1% glacial acetic acid for differentiation and microscopic control of the degree of differentiation, then baked dry. The sections were immersed in xylene for 5 min to achieve transparency. Afterwards, they were removed and allowed to dry slightly before being sealed with neutral gum. The paraffin sections were observed under a fully automated hemocyte analyzer (BC-30Vet, Shenzhen Myriad Bio-Medical Electronics Co., Ltd., China) to evaluate their microstructure.

-

Using the organic reagent precipitation method, metabolite extraction was conducted on two groups of kiwifruit samples collected on Days 1, 5, 9, and 13. Simultaneously, multiple quality control (QC) samples were prepared by extracting aliquots from all samples. The collected samples were thawed on ice, and metabolites were extracted with a 50% methanol buffer. Specifically, 100 mg of each sample was mixed with 1 mL of pre-chilled 50% methanol, vortexed for 1 min, and then incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The extracts were then stored overnight at −20 °C. After spinning at 4,000× g for 20 min, the supernatants were moved to new 96-well plates. The samples were kept at −80 °C until liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis was carried out. For the creation of a mixed QC sample, equal parts of each extract (10 µL) were pooled together.

Statistical analysis

-

Data analysis was performed by SPSS Statistics software. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test significance at p < 0.05. Duncan's multiple range test was used to evaluate differences between treatment groups. Graphs were created in Origin 2021, while partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) were conducted with SIMCA (14.1).

-

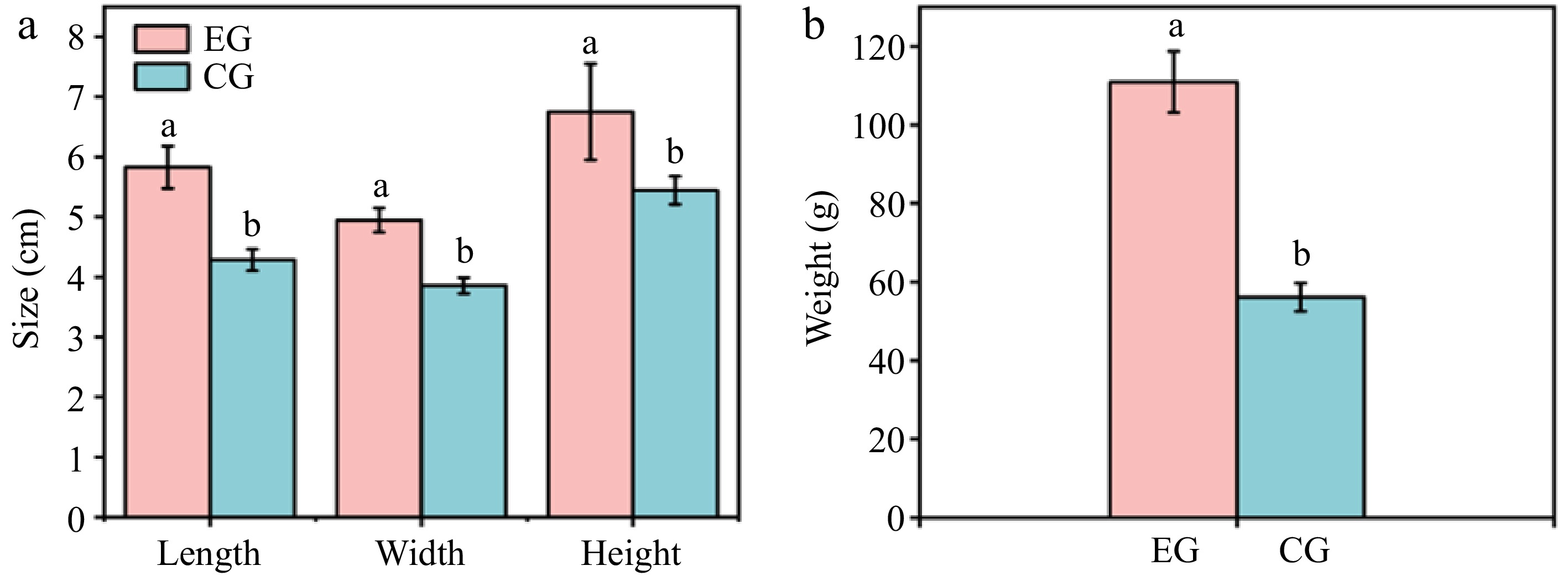

The weight of individual fruits is a key indicator of fruit quality, serving as a primary measure for evaluating the impact of plant growth regulators on fruit enlargement, directly influencing the commercial characteristics and economic value of kiwifruit. Fig. 1 shows the size and weight of the two groups of kiwifruits. After CPPU treatment, kiwifruit exhibited significantly greater dimensions and weight compared with the control sample. The use of CPPU increased the length of kiwifruit by 36.04%, width by 28.25%, height by 24.03%, and weight by 97.57%. This showed that applying CPPU to kiwifruit caused a significant rise in its size and weight. Such cell enlargement likely plays a key role in CPPU-induced size augmentation of kiwifruit. This was confirmed by the microstructure in subsequent experiments. This outcome aligns with the findings reported by Bi et al.[7], who discovered that for both Hayward and Xuxiang varieties, the use of CPPU led to a remarkable boost in fruit size and weight.

Figure 1.

Effect of CPPU treatment on (a) size and (b) weight of kiwifruit. EG, kiwifruit with CPPU treatment; CG, kiwifruit without CPPU treatment.

Quality attributes of kiwifruit

-

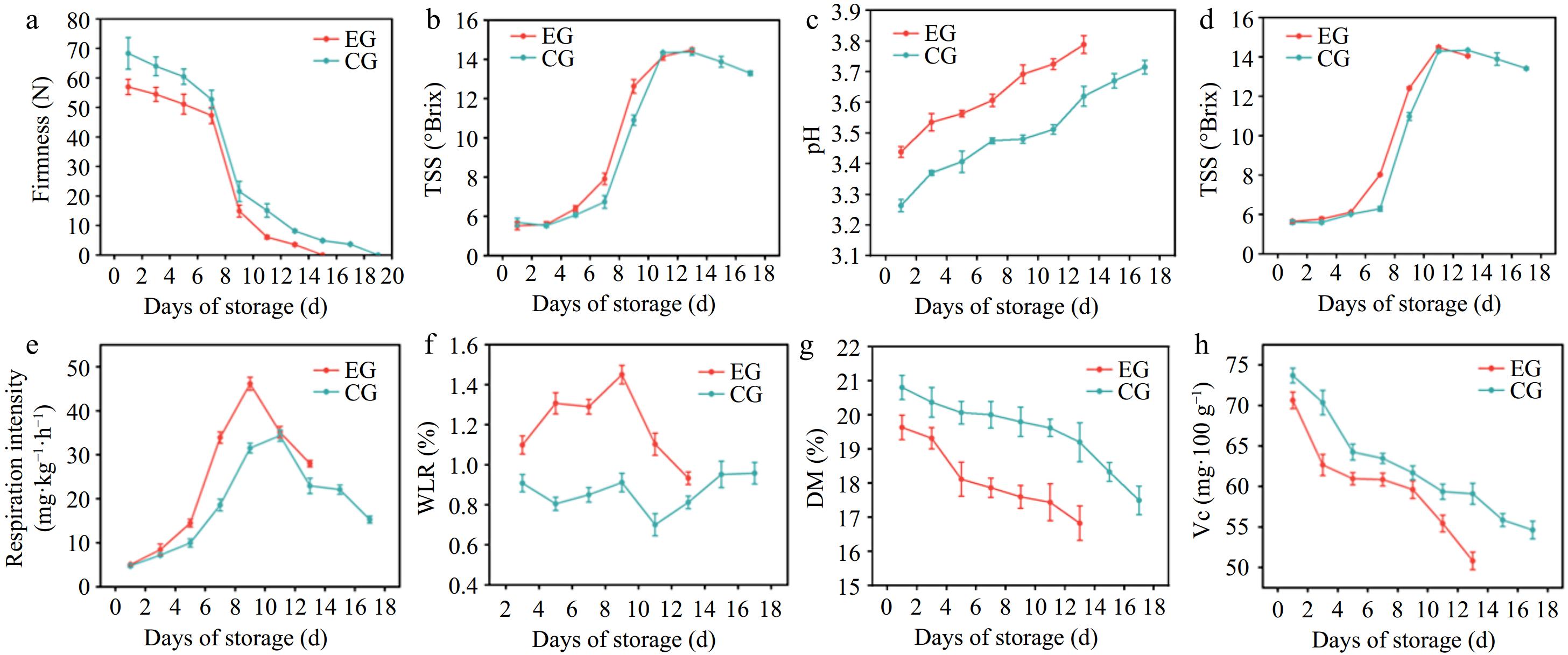

The quality attributes of kiwifruit, namely firmness, TSS, pH, SSC, RI, WLR, DM, and Vc are shown in Fig. 2. In the area of postharvest storage quality assessment, the firmness of fruit flesh is a critical determinant. Keeping adequate fruit flesh firmness is crucial for extending shelf-life. A decline in firmness is generally regarded as a key marker of the ripening phase in kiwifruit[17]. As kiwifruit ripens extensively in later stages, its decrease in firmness may be attributed to several factors. These likely contributors include diminished cell-to-cell adhesion, the breakdown of starch, and the altered composition and architecture of primary cell wall polymers[18]. Referring to Fig. 2a, kiwifruit in both groups showed a decline in firmness as storage time progressed. There was a slow decrease in the early stage, a rapid drop in the middle stage, and a gradual decrease in the later stage. However, the firmness of kiwifruit with CPPU treatment was always lower than that of the control group. Once the firmness of kiwifruit fell below 3 N, it was regarded to have achieved the sensory rejection threshold and was unsuitable for storage[19]. Therefore, a firmness threshold of less than 3 N was selected as the endpoint for the storage period. Compared with the control kiwifruit, kiwifruit with CPPU treatment were less hard, reached 3 N faster, and had a shorter edible shelf-life. Within the edible firmness range of kiwifruit, i.e., 3–15 N, it can be seen that at room temperature, kiwifruit with CPPU had an edible period of 5 days (Day 9 to Day 13), while kiwifruit without CPPU had an edible period of 7 days (Day 11 to Day 17). These results suggested that the use of CPPU reduced the shelf-life of kiwifruit. This was probably because CPPU hastened the ripening process of kiwifruit, accelerating the transformation of starch into soluble sugars and pectin into pectic acid, which, in turn, accelerated the decrease in firmness[19]. This finding was in agreement with the findings of Liu et al., who reported that firmness of kiwifruit with CPPU was lower than that of kiwifruit without CPPU, and that the greater the concentration of CPPU, the lower the firmness of the kiwifruit and the faster the decrease in firmness[20].

Figure 2.

Effect of CPPU treatment on (a) firmness, (b) TSS, (c) pH, (d) SSC, (e) RI, (f) WLR, (g) DM, and (h) Vitamin C in kiwifruit. EG, kiwifruit with CPPU; CG, kiwifruit without CPPU; TSS, total soluble sugar; SSC, soluble solids content; RI, respiration intensity; WLR, weight loss rate; DM, dry matter; Vc, Vitamin C.

Throughout the growth period, the starch in kiwifruit is transformed into monosaccharides by amylase, while the primary cell wall pectin is degraded by pectinase. These processes lead to a gradual increase in SSC content and a progressive decline in the firmness of kiwifruit[13]. As shown in Fig. 2b, d, the fluctuation patterns of SSC and sugar content were similar in terms of trends. During storage, the SSC content and Brix levels of kiwifruit in both groups initially rose quickly, then gradually slowed down and eventually stabilized with a slight decline during the later stages of storage. An increase in SSC content indicates quicker conversion of sugars and a reduced storage shelf-life for the fruit[21]. The SSC content and sugar level of kiwifruit with CPPU treatment were higher than those of the control samples. This may be because CPPU enhanced kiwifruit respiration and sped up polysaccharide conversion, thereby increasing the SSC content and sugar level of the fruit. Various studies have demonstrated that sugar accumulation, including fructose and glucose, is closely linked to cell enlargement. In kiwifruit treated with CPPU, sugars were found to promote the cell growth, thereby increasing the fruit's weight[22].

The pH level functions as a vital index for the respiration of fruit and its quality. As illustrated in Fig. 2c, when the storage time was extended, the pH of kiwifruit in both groups exhibited an upward trend, while acidity progressively declined. In the early stages, when the fruit is unripe, nutrient accumulation raises the acid content. As ripening progresses, acid transforms into sugars and other compounds, leading to an increase in pH[23]. During storage, the pH of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment showed a gradual increase from 3.26 to 3.72. Meanwhile, the pH of CPPU-treated kiwifruit also gradually increased, starting from 3.44 and ending at 3.79. The kiwifruit with CPPU treatment had a high respiration intensity and consumed more organic acids, so the acidity of kiwifruit with CPPU treatment was lower than that kiwifruit without CPPU.

Respiration in fruit is a physiological process where gas exchange continues even after harvest, involving oxygen intake and the release of carbon dioxide within the internal tissues. The primary function of respiration is to supply energy for sustaining physiological activities and metabolic processes, which help to maintain an optimal physiological state to prolong the fruit's freshness[24]. As the fruit matures and storage time extends, the respiration rate typically changes. An increase in respiration accelerates ripening and aging, which degrades fruit quality and negatively impacts both its storage stability and shelf-life[25]. As shown in Fig. 2e, the RI of kiwifruit in both groups exhibited an initial increase before decreasing. Nevertheless, the RI and peak RI of CPPU-treated kiwifruit were consistently higher than those of the control group; the peak RI of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment occurred on Day 9, while that of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment occurred on Day 11. During storage, the peak respiratory intensity of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment was 34.36 mg·kg−1·h−1, while that with the CPPU treatment was 46.14 mg·kg−1·h−1. It can be seen that the use of CPPU treatment increased the RI of kiwifruit; the peak RI increased and advanced, resulting in faster senescence and shorter shelf-life. Comparable findings of increasing the RI of kiwifruit were reported by Wang et al.[26]

The WLR is essential for evaluating the commercial value of kiwifruit, which serves as a key indicator of quality during postharvest storage. The primary factors influencing this are the respiratory rate and water loss of fruit due to transpiration, both of which directly affect the quality and taste of kiwifruit[27]. The weight loss not only reflects the freshness and preservative capacity of kiwifruit but also directly determines its shelf-life on the market[28]. Therefore, it is crucial to control weight loss. The weight loss of the two groups of kiwifruit is shown in Fig. 2f. It can be found that the weight of the two groups of kiwifruit decreased as storage time increased. The WLR of kiwifruit treated with CPPU was consistently higher than that of the control sample. The maximum weight loss was 0.96% for the control sample and 1.45% for the tested sample. Research has indicated that the primary reason for fruit weight loss is the transfer of water from the fruit to its surroundings. This process can lead to a reduction in the firmness and freshness of the fruit[29]. The high WLR of kiwifruit with CPPU treatment was probably the cause of the reduction in the firmness and freshness of kiwifruit.

The DM of a fruit represents the portion left after water is removed, reflecting the relative proportions of different organic and inorganic components within the fruit. DM serves as an important indicator of nutrient content and organic matter accumulation within the plant[30]. In general, a higher DM content suggests a greater concentration of nutrients within the fruit[31]. As shown in Fig. 2g, the DM content in both groups of kiwifruit declined as storage extended. This decrease in DM was attributed to a gradual depletion of organic matter and nutrients due to respiratory activities over time. Throughout the duration of storage, the DM content of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment gradually decreased from 19.64% to 17.50%, and that of kiwifruit with CPPU treatment decreased from 20.81% to 16.83%. The DM content of kiwifruit with CPPU treatment resulted in a greater decrease than that of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment, suggesting that the use of CPPU treatment on kiwifruit led to a decrease in the DM content of kiwifruit, which affected the flavor and quality of kiwifruit, causing nutrient loss[8].

Vc is an important nutrient in the kiwifruit that reflects the fruit's quality. Increased storage time causes nutrient loss in kiwifruit. As shown in Fig. 2h, the Vc content in kiwifruit declined over the storage period in both groups. However, kiwifruit without CPPU treatment consistently maintained higher Vc levels compared with those treated with CPPU. During storage, the Vc content of kiwifruit without CPPU decreased from 73.69 to 54.62 mg·100 g−1, while that with CPPU decreased from 70.63 to 50.81 mg·100 g−1. These results suggested that the use of CPPU on kiwifruit decreased the Vc content of kiwifruit, which affected the nutritive value and postharvest quality of kiwifruit. This may be related to the dilution of Vc as a result of CPPU-promoted expansion of kiwifruit. In addition, CPPU treatment resulted in an increase in the respiration of kiwifruit during storage, and Vc, as an antioxidant, was consumed in large quantities. These findings were consistent with the study by Kim et al.[32], who indicated that the application of CPPU led to a reduction in the Vitamin C content of kiwifruit. This particular investigation revealed a significant reduction in the Vc concentration in fruits subjected to CPPU treatment.

Enzyme activities

-

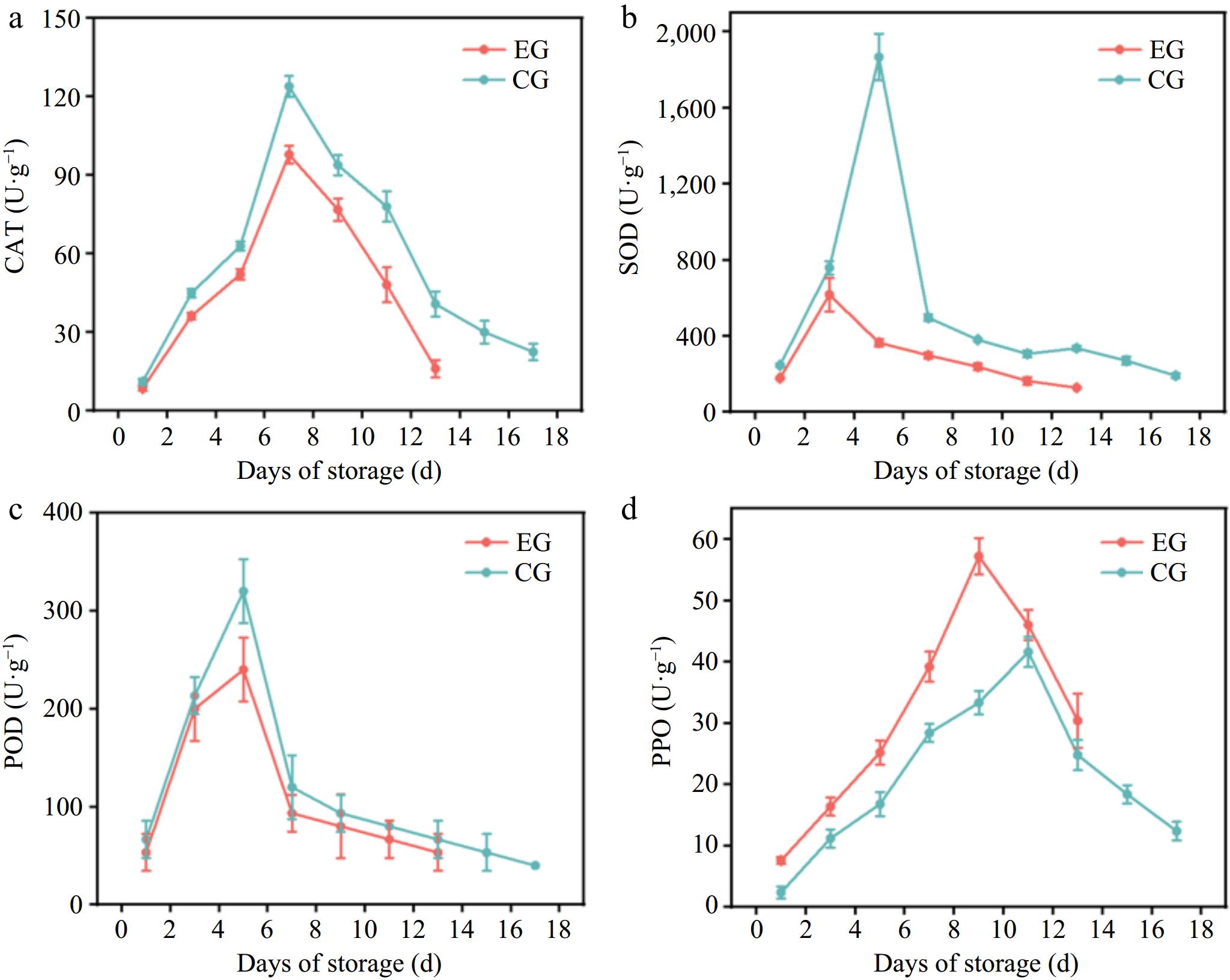

CAT, SOD, and POD are essential enzymes for oxyradical detoxification in plant tissues, especially under stress conditions. Plants typically enhance the activity of these enzymes,[33] and a reduction in enzymatic activity may correspond to a lowered ability to prevent cellular damage. The activities of antioxidant enzymes such as CAT and SOD play a crucial role in delaying fruit senescence by scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby reducing oxidative damage and maintaining the cell membrane's stability[34,35]. As mentioned in the study by Ma et al.[36], postharvest ripening combined with 1-MCP helps regulate these enzyme activities, effectively preserving the antioxidant capacity of kiwifruit and maintaining its quality during storage. This study assessed the impact of CPPU on antioxidant enzymes by evaluating the activities of CAT, SOD, and POD in the two groups of kiwifruit stored at room temperature. The effect of CPPU on the antioxidative metabolism of kiwifruit is shown in Fig. 3. During storage, the activities of CAT, SOD, and POD in both groups of kiwifruit first increased and then decreased. The peak activities of CAT, SOD, and POD in untreated kiwifruit were 123.90, 1,866.93, and 320 U·g−1, respectively. In CPPU-treated kiwifruit, the peak activities were 97.87, 617.12, and 240 U·g−1, respectively. The activities of antioxidant enzymes in CPPU-treated kiwifruit were lower than those in untreated kiwifruit. This suggested that CPPU treatment reduced the antioxidant capacity of cells, hindered the timely scavenging of reactive oxygen species, increased membrane lipid peroxidation and cell membrane damage, and accelerated the aging of kiwifruit[26].

Figure 3.

Effect of CPPU treatment on (a) CAT, (b) SOD, (c) POD, and (d) PPO activity of kiwifruit. EG, kiwifruit with CPPU; CG, kiwifruit without CPPU; CAT, catalase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; POD, peroxidase; PPO, polyphenol oxidase.

PPO catalyzes the oxidation of polyphenols to quinones, which subsequently polymerize into brown pigments, leading to browning in plant leaves and fruits[37]. Fig. 3d shows that during the storage period, PPO activity in kiwifruit from both groups first increased and then declined. The peak activity of kiwifruit PPO without CPPU treatment was 41.6 U·g−1, while that with CPPU treatment was 57.2 U·g−1. The higher PPO activity with CPPU treatment indicated that CPPU increased the PPO activity in kiwifruit, enhanced the degree of fruit browning with cold damage, and accelerated the senescence of kiwifruit, thus promoting oxidative senescence of kiwifruit. Similar results were found by Hou et al.[38], showing that CPPU treatment increased PPO activity in "Shine Muscat" grapes.

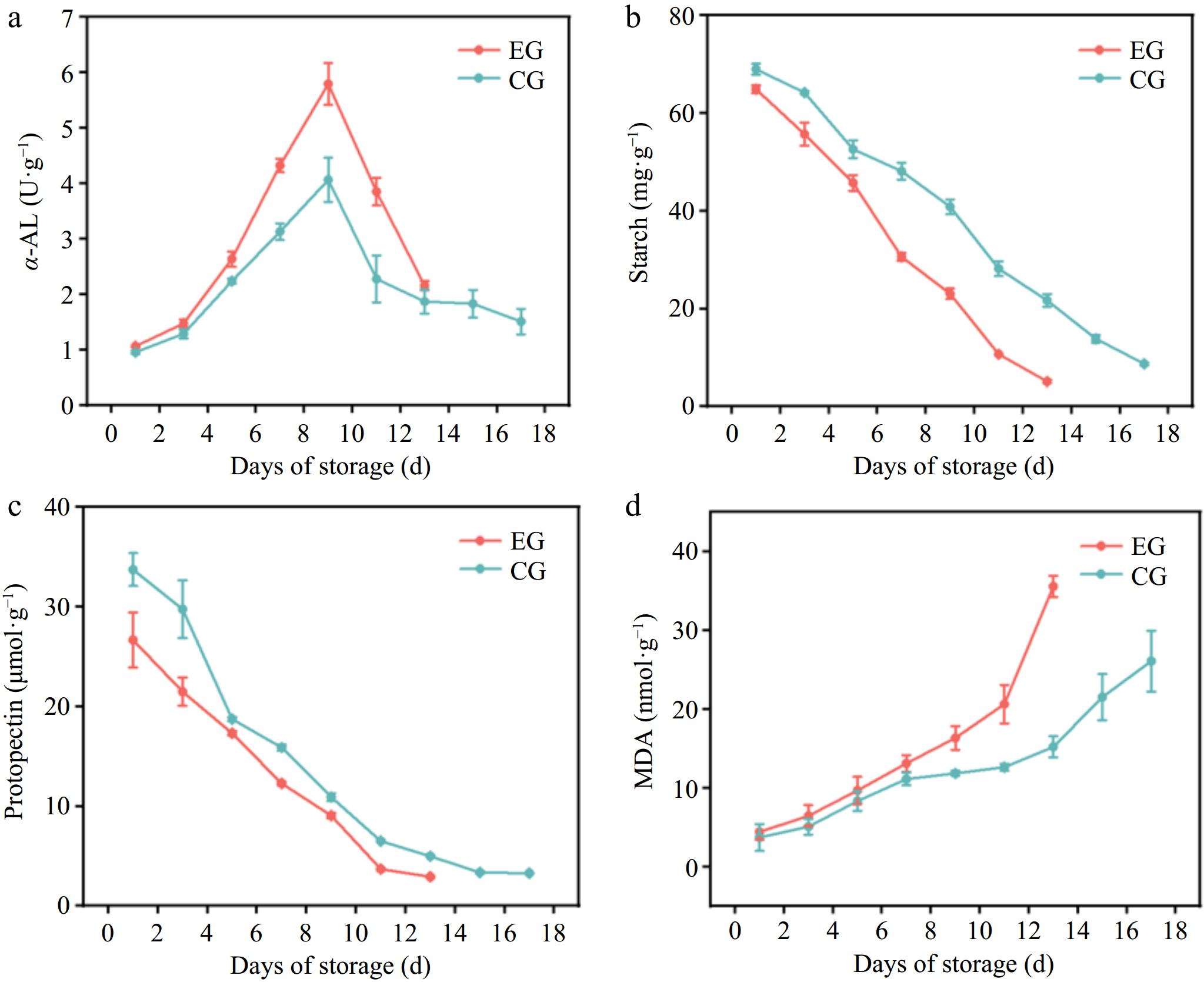

α-AL is widely found in animals, plants, and microorganisms, and is a crucial starch hydrolase. It randomly breaks α-1,4 glucosidic bonds within starch, glycogen, and oligo- or poly-saccharides, producing maltose, oligosaccharides, glucose, and other products[39]. As shown in Fig. 4a, during the storage process, the α-AL activity of both groups of kiwifruit initially rose and then declined. The peak α-AL activity of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment was 4.07 U·g−1, while that of the CPPU-treated kiwifruit was 5.79 U·g−1. The higher α-AL activity of kiwifruit with CPPU treatment was attributed to the fact that CPPU increased the α-AL activity of kiwifruit, promoting starch hydrolysis. Excessive starch decomposition may lead to reduced quality of kiwifruit in the later stages of storage, accelerated ripening, and a shorter ready-to-eat shelf-life. This also contributed to a higher SSC in kiwifruit with CPPU treatment than in the control sample.

Figure 4.

Effect of CPPU treatment on (a) α-AL activity, (b) starch, (c) protopectin, and (d) MDA content activity of kiwifruit. EG, kiwifruit with CPPU; CG, kiwifruit without CPPU; ɑ-AL, α-amylase; MDA, malondialdehyde.

Starch, protopectin, and MDA content of kiwifruit

-

Starch, a natural polymer created by the polymerization of glucose molecules, serves as the primary storage form of carbohydrates within cells. It serves an essential function during the entire growth and development process of plants[40]. Starch significantly influences the texture, flavor, and nutritional quality of fruits. Measuring starch content is essential for analyzing sugar metabolism in organisms and assessing the nutritional value of foods[41]. The conversion of starch into soluble sugars is a crucial sign of postharvest ripening in kiwifruit[42]. During the storage period, the starch content of both groups of kiwifruit demonstrated a downward trend, with the progression being relatively gradual. The breakdown of starch in harvested fruits resulted in softer and sweeter fruit. This suggests a significant positive correlation between starch content and fruit firmness. Starch accumulation in kiwifruit cells, with limited breakdown, contributed to maintaining cell turgor pressure and preserving the fruit's greater firmness[43]. Starch was converted to sugar with a corresponding decrease in swelling pressure and firmness. Kiwifruits with CPPU treatment had lower firmness and starch content than those without CPPU treatment; therefore, the use of CPPU accelerated the decline in the starch content and firmness of kiwifruit. These results reflect the fact that the CPPU-treated fruit matured earlier and senesced faster than untreated fruit[44].

Pectin, found in the primary and middle lamella of fruit cell walls, plays a role in enhancing intercellular adhesion and mechanical strength. The degradation of pectin is considered to be a key factor contributing to postharvest fruit softening[45]. Protopectin, a polysaccharide found in the plant cell wall, offers structural support and is essential in the softening process of kiwifruit[46]. During the postharvest softening process, the gradual decomposition of cell wall protopectin into water-soluble pectin may compromise the structural integrity of the cell wall. This breakdown leads to a softer fruit texture and reduced firmness[47]. In fleshy fruits, pectin's breakdown is closely associated with the softening process in kiwifruit[8]. During the storage period, both groups of kiwifruit showed a decline in protopectin content. Research has shown that there is a strong positive correlation between the firmness of kiwifruit and the content of protopectin. This implies that the breakdown of cell wall polysaccharides is closely linked to the softening of kiwifruit. The gradual breakdown of cell wall protopectin during post-ripening softening compromises the cell walls' integrity, leading to a softer fruit texture. During storage, the pectin content of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment decreased from 29.75 to 3.28 µmol·g−1, while that with CPPU treatment decreased from 26.67 to 2.92 µmol·g−1. The protopectin content in CPPU-treated kiwifruit was lower than that in untreated ones. This was because CPPU speeds up the degradation of protopectin, damages the cell walls' structure, and accelerates kiwifruit aging. From these results, it is clear that CPPU led to the degradation of raw pectin and starch in kiwifruit; both of which contributed to a decrease in firmness with accelerated senescence of the fruit.

The ripening of fruit is typically associated with damage to the cell membranes and excessive lipid oxidation[48]. MDA is an important marker of an organism's antioxidant potential, indicating both the intensity and rate of lipid peroxidation. It also provides an indirect measure of the extent of peroxidative damage within the tissues[49]. During fruit ripening, lipid oxidation intensifies, resulting in membrane damage, electrolyte leakage, and loss of cellular contents. This process leads to increased conductivity, compromised cell membrane integrity, and subsequent fruit softening[50]. As shown in Fig. 4d, the MDA content of both groups of kiwifruit rose throughout the storage period. The MDA content of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment increased from 3.71 to 26.08 nmol·g−1, while that with CPPU treatment increased from 4.42 to 35.55 nmol·g−1. A higher MDA in the kiwifruit with CPPU treatment was attributed to the CPPU treatment, which enhanced MDA accumulation, thereby accelerating lipid peroxidation in the cell membranes. This process reduced the defense against ROS with a compromised cellular structure, which hastened the aging process of the fruit.

Within-group correlation analysis of two groups of kiwifruits

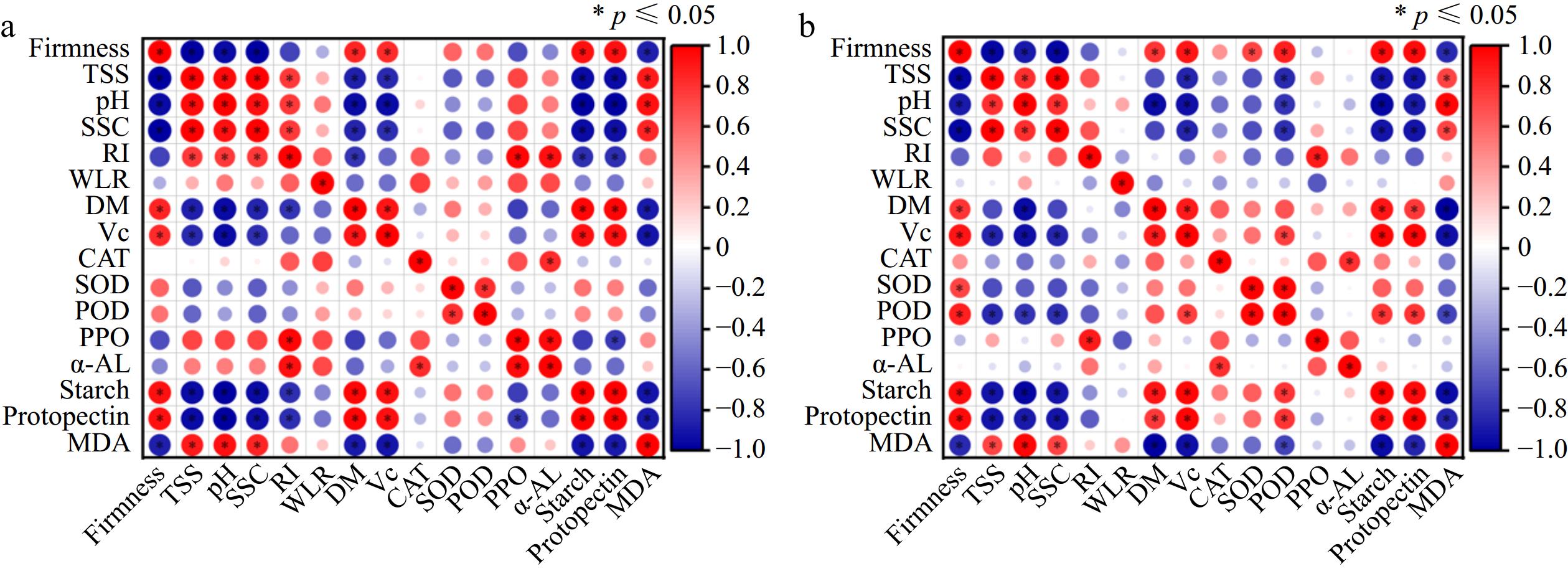

-

Fig. 5 presents the correlation analysis for both kiwifruit groups, with blue denoting a positive correlation and red indicating a negative one. Stronger correlations are represented by darker shades and larger circles. As can be seen, the firmness of kiwifruit in both groups was positively and statistically correlated with the content of Vc, DM, starch and pectin. Fruit firmness indicates the pulp's resistance to compression, serving as an indicator of the fruit's ripening and softening stages. Cell wall integrity is essential in influencing the firmness of fruit[51]. Pectin, a major component of the cell wall, dissolves as fruit ripens, thereby reducing or even eliminating the wall's structural support. This causes individual cells to deform gradually, with the intercellular spaces becoming loosely packed, leading to a progressive softening of the fruit and a reduction in firmness. With the degradation of starch, the fruit gradually ripened, firmness gradually decreased, nutrient content gradually decreased, and the content of Vc and DM decreased. The firmness of kiwifruit in both groups showed negative correlations with SSC, TSS, pH and MDA content. This could be attributed to the breakdown of starch during storage, which decreased firmness and increased sweetness while reducing acidity. Similar results have been reported Luo et al.[52], who indicated that kiwifruit firmness demonstrated highly significant negative correlations with weight loss, soluble sugars, and the solid–acid ratio; conversely, it showed highly significant positive correlations with Vc and cellulose content. The rise in MDA content damaged the cellular structure of kiwifruit, which also led to a decrease in firmness. In conclusion, the strong correlations between firmness, SSC, and other common indicators used to evaluate ready-to-eat kiwifruit quality offer a theoretical basis for defining quality standards for the two kiwifruit groups. These results provide significant insights for enhancing the harvest timing, storage methods, and consumption of kiwifruit. They also offer valuable guidance for developing quality control strategies within the kiwifruit industry[53].

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis of (a) kiwifruit with CPPU treatment and (b) kiwifruit without CPPU treatment.

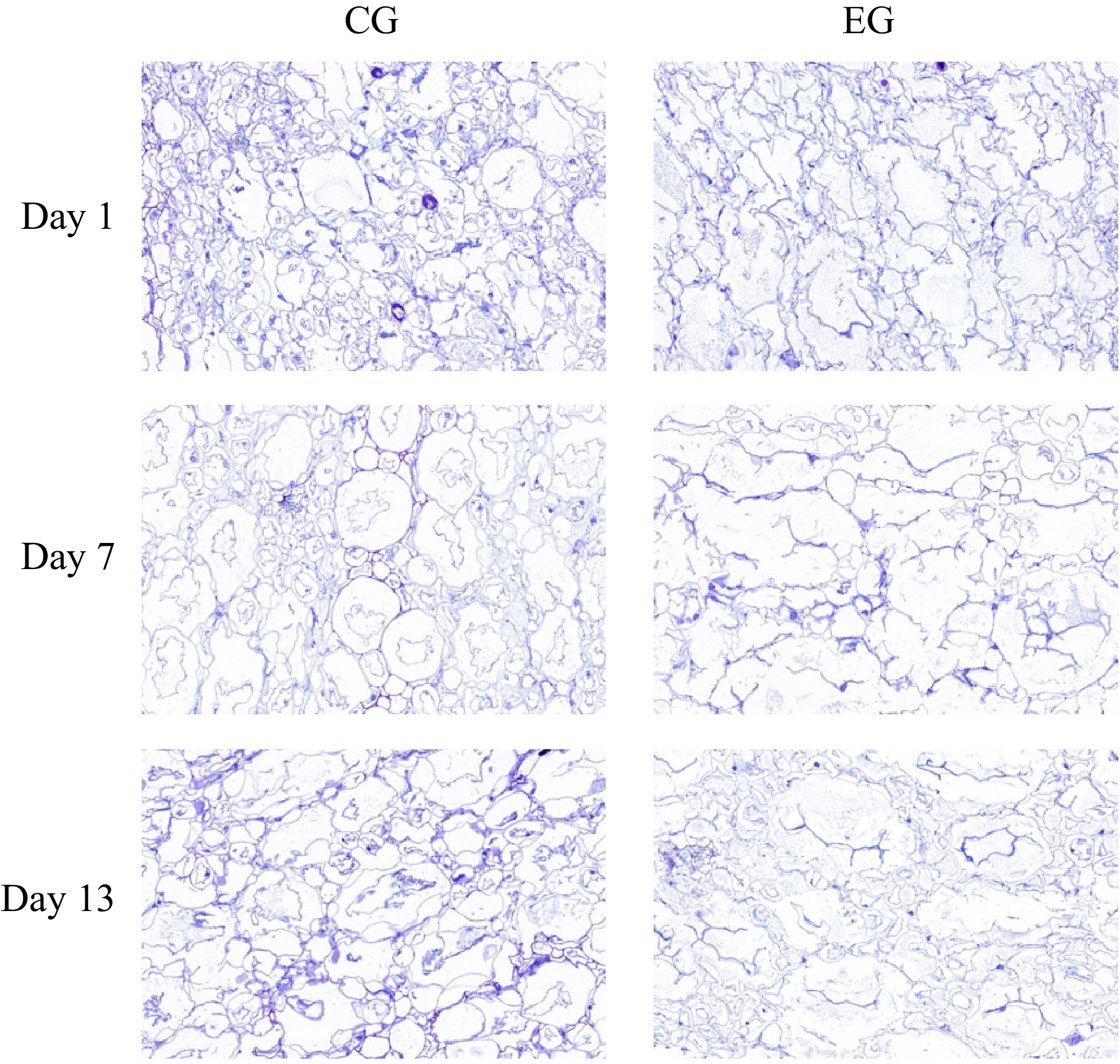

Microstructure

-

Fruit firmness is affected by changes in the composition of specific cell wall polysaccharides, such as cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin. In kiwifruit, the loss of firmness is induced by a reduction in cell wall polysaccharides, the breakdown of starch reserves, diminished intercellular adhesion, modifications to the polymeric framework of cells, and adjustments to the cytoplasmic ultrastructure[54]. As shown in Fig. 6, the cells of the two groups of kiwifruit became more and more dispersed, and the shape of the edges became progressively more irregular as the storage time increased. However, in general, the cell wall structure of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment was more stable with a more regular and orderly cell shape. In contrast, the cells of kiwifruit with CPPU treatment were dispersed, with irregularly shaped edges, and the cell volume was slightly larger than that of kiwifruit without CPPU treatment. With prolonged storage, significant degradation and breakdown of kiwifruit cell walls were observed. This effect was attributed to cell wall hydrolysis, driven by the activity of pectin methyl esterase, polygalacturonase, and cellulose enzymes[55]. CPPU stimulates cell division and/or expansion, leading to increased allocation of water and carbohydrates to the fruit, thereby enhancing its size[56]. Ainalidou et al.[57] confirmed that CPPU promoted kiwifruit growth primarily by enlarging small cells rather than stimulating cell division. Previous research demonstrated that CPPU enhanced fruit weight by promoting the expansion of "small" isodiametric parenchyma cells in the exocarp[58].

Figure 6.

Effect of CPPU treatment on the cellular structure of kiwifruit. EG, kiwifruit with CPPU; CG, kiwifruit without CPPU.

Metabolomics

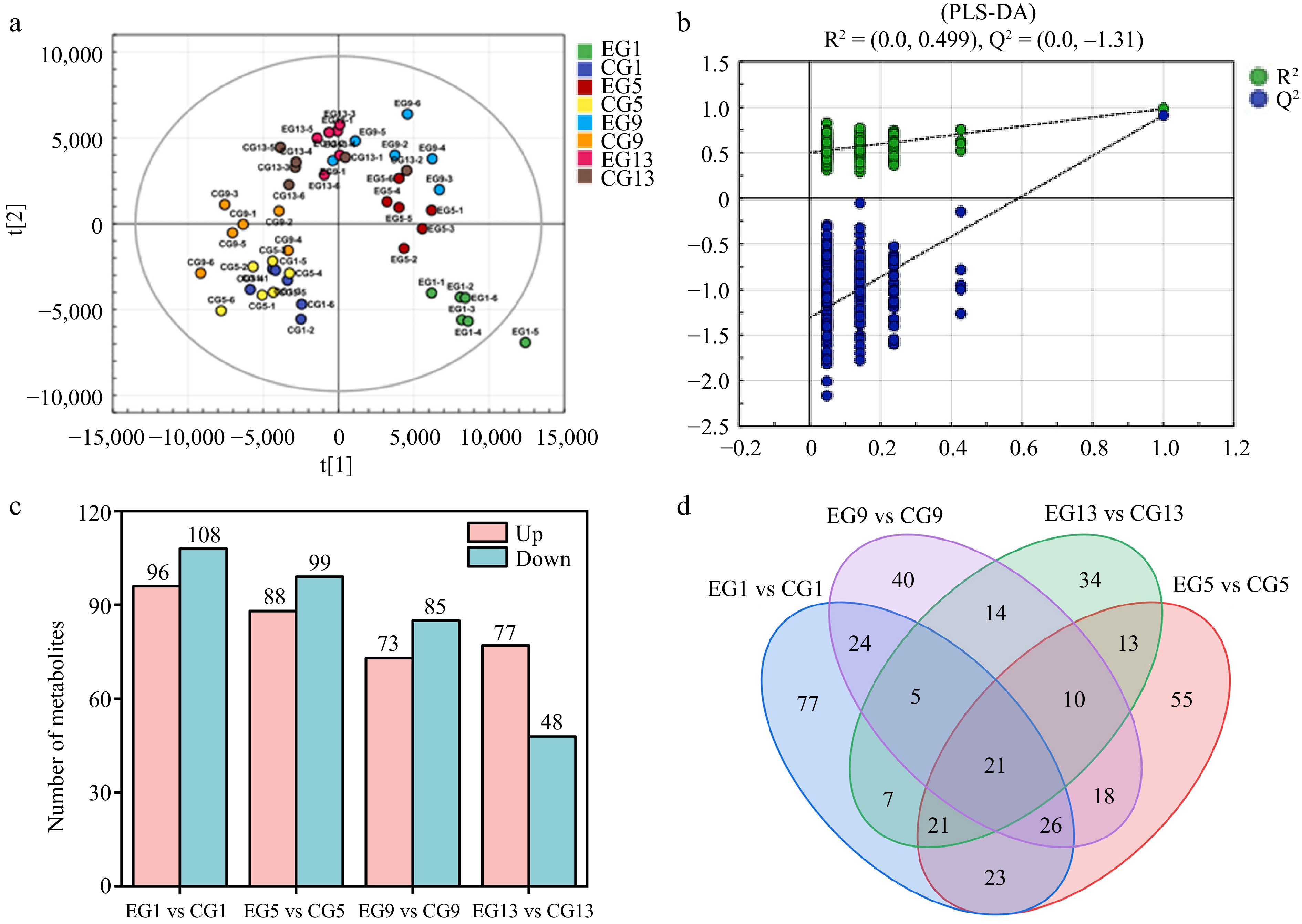

PLS-DA analysis

-

Samples EG1, EG5, EG9, and EG13 represent kiwifruit with CPPU treatment on Days 1, 5, 9, and 13, respectively, while Samples CG1, CG5, CG9, and CG13 represent kiwifruit without CPPU treatment on Days 1, 5, 9, and 13, respectively.

PLS-DA, a supervised analytical method, enhances differentiation between groups using partial least squares regression. It constructs a model to connect metabolic profiles with sample classifications, enabling effective sample classification. Additionally, the PLS-variable importance in projection (VIP) method is highly effective at identifying important predictor variables[59]. The analysis of metabolite changes in the two groups of kiwifruit during ripening was conducted using the PLS-DA model to assess the overall differences in the metabolites. In Fig. 7, each point represents a sample, with different colors indicating various subgroups. The relative position of each point reflects the degree of dispersion among the samples. Samples positioned closer together suggest more similar expression patterns. Fig. 7a shows the scatter plot of PLS-DA scores for the entire sample set. Thus, the results of the study were able to comprehensively demonstrate the differences in metabolites between kiwifruits using and not using CPPU, suggesting that the constructed PLS-DA model was stable and can be used for subsequent analyses of metabolite differences. Fig. 7b illustrates a distinct separation trend between the two groups, highlighting a strong classification effect. The results show that CPPU caused major shifts in both the kinds and relative levels of kiwifruit metabolites. To check how well the model works, we performed a random permutation test with 200 iterations. The results, with R2 = 0.499 and Q2 = −0.131, confirmed that the model was stable and interpretable and had a strong predictive capacity.

Figure 7.

(a) PLS-DA analysis chart, (b) replacement test chart, and (c) statistics of differential metabolites. (d) Venn chart of different metabolites: EG1, EG5, EG9, and EG13, Kiwifruit with CPPU on Days 1, 5, 9, and 13, respectively; CG1, CG5, CG9, and CG13, kiwifruit without CPPU on Days 1, 5, 9, and 13, respectively.

Differential metabolites

-

Metabolomics, when applied to kiwifruit storage and preservation, offers a comprehensive and precise approach to analyzing the dynamic changes in metabolites during postharvest ripening[60]. The determination of differential metabolites in each comparison group was conducted through quantification. Metabolites that are significantly upregulated are represented by red bars. Conversely, those that are significantly downregulated are shown by green bars. Figure. 7c shows that, on Day 1 of storage, there were 204 differential meta bolites in the EG versus CG comparison for the kiwifruit groups, with 96 being upregulated and 108 being downregulated. By Day 5, 187 differential metabolites were observed, with 88 upregulated and 99 downregulated. On Day 9, this comparison revealed 158 differential metabolites, with 73 upregulated and 85 downregulated. On Day 13, a total of 125 differential metabolites were identified, including 77 upregulated and 48 downregulated ones in EG compared with CG.

Venn diagram of differential metabolites

-

A Venn analysis was conducted to examine the differential metabolites in kiwifruit from the two groups, providing insights into both the shared and unique metabolites between them. This analysis highlighted the similarities and distinctions in the differential metabolites across the groups, where each circle represented a comparison group and each color represented an individual set with the number of differential metabolites in each set. A Venn diagram illustrating the differential metabolites among the four groups of kiwifruit from the two groups indicated that 91 differential metabolites overlapped between EG1 vs CG1 and EG5 vs CG5, 76 differential metabolites overlapped between EG1 vs CG1 and EG9 vs CG9, and 54 differential metabolites overlapped between EG1 vs CG1 and EG13 vs CG13. Among them, 21 differential metabolites overlapped in the four groups. The overlap of differential metabolites became less and less as the storage time increased, which was consistent with the results of previous studies.

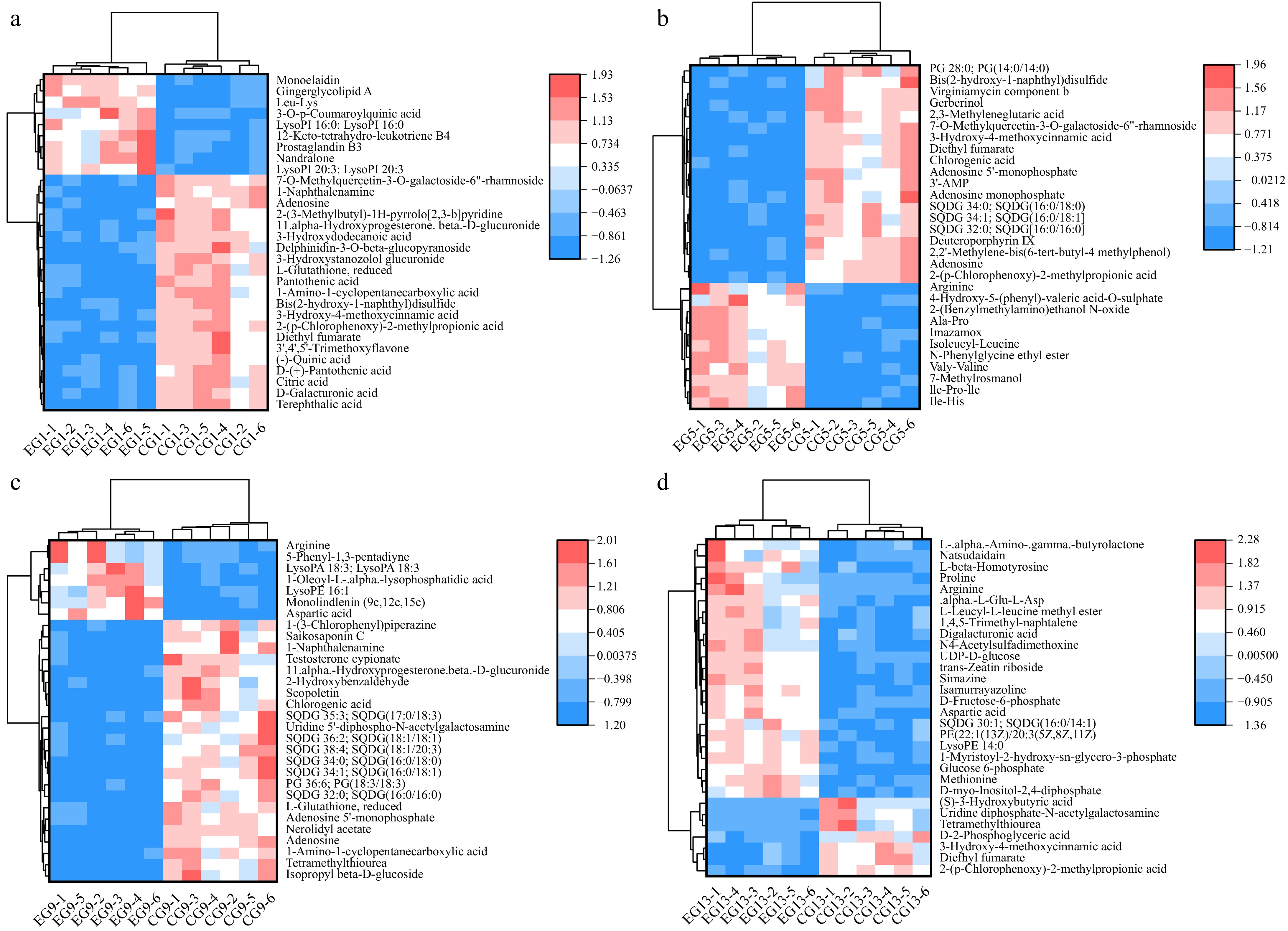

Heat map analysis of differentially expressed metabolites

-

The horizontal coordinates of the heatmap are the samples and the vertical coordinates are the differentially expressed metabolites screened. Fig. 8 shows the top 30 most differentially expressed metabolites in both kiwifruit groups throughout the storage period, with the colors representing the relative abundance levels of each metabolite. With VIP > 1.0 and p < 0.05 used to determine the components with significance differences, the metabolites that were differentially expressed in the two groups of kiwifruits during storage were 414 lipids and lipid-like molecules; 195 organic acids and their derivatives; 79 benzene compounds; 69 organic heterocyclic compounds; 43 phenylacetone and polyketone compounds; 41 organic oxygen compounds; 17 nucleosides, nucleotides, and analogues; 16 alkaloids and their derivatives; seven organic oxygen compounds; six hydrocarbons; five organic nitrogen compounds; and three others. Among the most common metabolites that differed between the two kiwifruit groups during storage were quinic acid, citric acid, pantothenic acid, 1-amino-1-cyclopentanecarboxylic acid, aspartic acid, and arginine.

Figure 8.

Heatmap of different metabolites. (a) Heatmap of different metabolites on Day 1; (b) heatmap of different metabolites on Day 5; (c) heatmap of different metabolites on Day 9; (d) heatmap of different metabolites on Day 13.

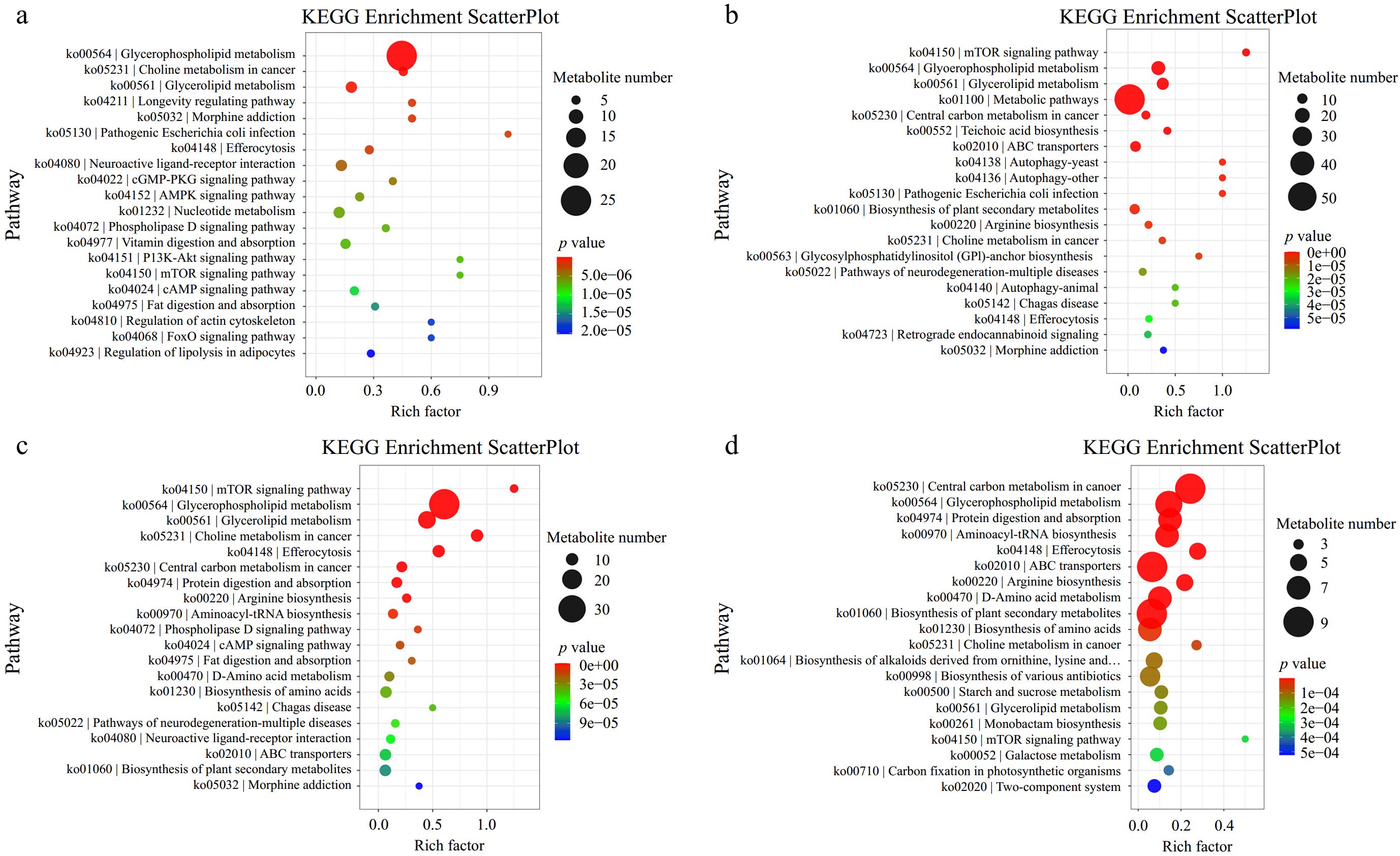

Differential metabolites' Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes metabolic pathway enrichment

-

The pathway with the lowest p-value among the top 20 was selected for visualization using a bubble plot, as shown in Fig. 9. The rich factor represents the proportion of differentially expressed metabolites in a specific pathway relative to the total metabolites in that pathway. A higher rich factor indicates more significant pathway enrichment. In the scatter plot, each dot's size reflects the number of differentially expressed metabolites in that pathway. The colors of the dots denote the p-value from the enrichment analysis, where varying colors correspond to differing levels of significance in the enrichment outcomes. The top 10 KEGG paths were filtered in order of p-value from the smallest to the largest. On the fifth day of storage, the first three Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways were mTOR signaling pathway, glycerophospholipid metabolism, glycerolipid metabolism. However, on the ninth day of storage, they were changed to the mTOR signaling pathway, glycerophospholipid metabolism, and glycerolipid metabolism. This suggested that CPPU treatment caused a differential metabolic pathway during the storage period, which needs to be deeply investigated further.

Figure 9.

KEGG enrichment graph of different metabolites. (a) KEGG enrichment plots of different metabolites on Day 1; (b) KEGG enrichment plots of different metabolites on Day 5; (c) KEGG enrichment plots of different metabolites on Day 9; (d) KEGG enrichment plots of different metabolites on Day 13.

-

The market for ready-to-eat kiwifruit has grown considerably in recent years due to the fruit's uniform flesh maturity with enhanced taste and flavor, allowing consumers to enjoy it right away. Although the effect of CPPU treatment on the yield of kiwifruit has been well documented, its effect on the edible window and shelf-life qualities remains unclear. This study focused on the impact of CPPU treatment on ready-to-eat kiwifruit. The results indicated that CPPU treatment decreased the shelf-life and lowered the activity of various antioxidant enzymes, and increased the respiration intensity and metabolism of ready-to-eat kiwifruit during storage. Observation of the cellular structure showed that CPPU accelerated the rupture and degradation of kiwifruit cell walls, closely related to the shorter ready-to-eat shelf-life of the fruit. CPPU resulted in significant differences in the types and relative concentrations of kiwifruit metabolites. This study provides valuable information on the development of ready-to-eat kiwifruit. Future research could delve deeper into the mechanism of CPPU treatment in shortening the shelf-life of ready-to-eat kiwifruit to support the rapidly developing ready-to-eat kiwifruit market.

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the National Key R&D project of China (2022YFD1600700), Key R&D Program (2024NC-YBXM-141, 2024NC-GJHX-25, 24NYGG0065), and Construction of Qin Chuangyuan's "Scientists + Engineers" Project (2024QCY-KXJ-070), which have enabled us to conduct this study.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: supervision: Liu Z, Mo H; investigation: Liu Z, Gong X, Xu D, Li H; project administration: Liu Z, Hu L, Mo H; visualization: Cheng P; conceptualization: Xu D, Mo H; data curation: Cheng P, Chitrakar B; formal analysis: Cheng P, Li H; methodology: Xu D, Hati S; validation: Gong X, Li H; writing − original draft: Liu Z, Cheng P; writing − review & editing: Chitrakar B, Hati S; resources, software: Wang W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu Z, Cheng P, Hati S, Gong X, Xu D, et al. 2025. Effects of forchlorfenuron treatment on the shelf-life quality of ready-to-eat kiwifruit and its mechanism. Food Innovation and Advances 4(3): 400−411 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0042

Effects of forchlorfenuron treatment on the shelf-life quality of ready-to-eat kiwifruit and its mechanism

- Received: 24 February 2025

- Revised: 19 May 2025

- Accepted: 24 June 2025

- Published online: 03 September 2025

Abstract: Ready-to-eat kiwifruit refers to kiwifruit with a uniform texture, maturity and favorable taste that can be consumed immediately after purchase without the requirement for a natural ripening process. Although extensive research has been conducted on the application of forchlorfenuron (CPPU) in kiwifruit cultivation, studies on its impact on the "edible window" of ready-to-eat kiwifruit and relevant mechanisms remain limited. In this study, to investigate the impact of CPPU treatment on the edible shelf-life qualities of ready-to-eat kiwifruit, we conducted an in-depth analysis of multiple aspects, including fruit qualities, enzyme activities, cellular structure, and metabolites. The results indicated that CPPU treatment increased the fruits' volume and weight, but decreased the firmness. During storage, CPPU treatment increased the respiratory rate of kiwifruit, with a peak respiratory intensity of 46.14 mg·kg−1·h−1 and 34.36 mg·kg−1·h−1 for the samples treated with or without CPPU, respectively. This suggested that CPPU accelerated the conversion of starch to sugar and the ripening of kiwifruit. At room temperature, the edible window of ready-to-eat kiwifruit not exposed to CPPU was 7 days, while the samples treated with CPPU was 5 days. This was probably attributed to the reduction in antioxidant enzyme activities like catalase and superoxide dismutase, and the increase in ɑ-amylase activity and malondialdehyde content after treatment with CPPU. The present study supplies useful information for developing ready-to-eat kiwifruit, especially for CPPU-treated kiwifruit.

-

Key words:

- Ready-to-eat kiwifruit /

- Forchlorfenuron /

- Shelf-life