-

Globally, the food industries produce extensive quantities of food waste and by-products, mostly from fruit and vegetable resources. Postharvest handling and storage generate significant waste due to improper processing, creating many by-products[1]. These materials have potential for utilization in food packaging, due to their organic and nutritional composition. These food waste and by-products have organic compounds like polysaccharides, polyphenols, fiber, proteins, vitamins, and minerals, and lipids, which can offer health benefits and improve food products' nutritional, functional, and technological quality[2].

These waste and by-products' bioactive compounds enable the production of sustainable food packaging material with functional polymers that are environmentally friendly[3]. Food waste depletes critical resources, such as water, land, and energy, resulting in food loss. Globally, addressing this issue and governments, including the EU, acknowledge its significance and advocate for strategic measures to reduce food waste, such as waste legislation and food waste management, which can lower production costs and enhance food system efficiency[4]. Waste valorization of by-products into fuels, biomaterials, and chemicals is essential for a circular economy, and the food sector prioritizes food waste prevention and reduction. Recycling food waste creates value-added goods for animal feed, biofuels, organic fertilizers, and energy production[5]. Food residues are edible portions of food materials discarded due to insufficient storage, transportation challenges, suboptimal processing techniques, and consumer behavior, at various stages including harvesting, processing, distribution, and consumption[6].

These by-products are mostly generated by industrial processes, such as the production of wine from grapes, oil from olive pomace, and various fruit-based products like juices, jams, and jellies. In addition, the processing of vegetables, including potatoes, tomatoes, fennels, artichokes, and carrots contribute to the formation of these byproducts. These fruits and vegetable by-products contain naturally organic compounds, and vital bioactive molecules such as tocopherols, flavonoids, carotenoids, vitamins, and aromatic compounds have beneficial antioxidant and antiviral properties[7].

Food by-products are used in biodegradable packaging to improve film quality, extend shelf life, and enhance the safety and recyclability of food items, contributing to the production of environmentally friendly, decomposable packaging[3]. Around 40%−50% of garbage comprises roots, tubers, and other by-products from fruits and vegetables. Generally, 10%−35% of unprocessed fruits and vegetables, including elements such as seeds, pulp, skin, and pomace, are eliminated as by-products[8]. Currently, researchers have been exploring the use of fruit waste and by-products as nutritional additives in various food items.

This investigation assessed the application of food industry waste and by-products in packaging materials to moderate global microplastic pollution. Various techniques for extracting bioactive compounds from food waste have been examined. The incorporation of these substances into packaging materials enhances their safety, durability, and preservation. This study shows the recent advancements in functional packaging materials and their advantages. It concentrates on the reuse of industrial food waste to enhance packaging performance and biodegradability, emphasizing the role of by-product extracts in improving film characteristics.

-

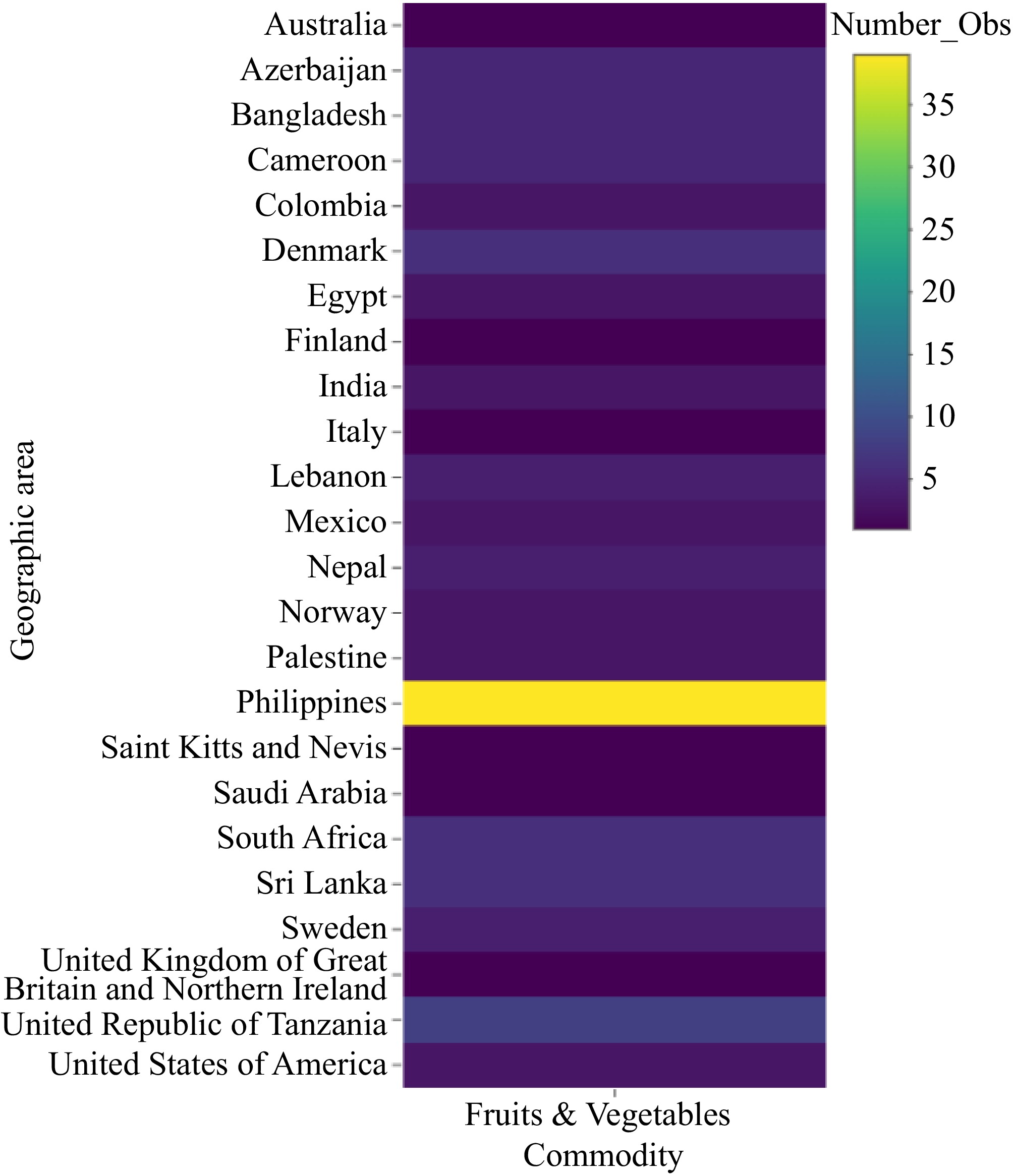

A systematic methodology was employed to thoroughly collect and analyze the literature related to fruit and vegetable waste and by-products. A systematic review was performed using established databases including Google Scholar, PubMed, Academia, and other valued resources. The search keywords such as 'fruit and vegetable by-products', 'food by-products extraction', 'fruit by-products bioactive compounds', 'utilization in biodegradable material', and 'utilization in food packaging'. The relevance and quality of the literature that was collected were guaranteed by carefully defining inclusion criteria. This published knowledge of food waste utilization is effective and up-to-date (2018-2025) because it includes peer-reviewed studies, scholarly publications, and the latest credible academic sources.

-

Fruit and vegetable waste and by-products contribute significantly to economic losses in the food and agricultural sector. The fruit and vegetable industry produces millions of tons of residues annually, causing substantial financial obstructions[9]. According to the World and Agriculture Organization, one-third of edible food intended for human consumption is lost or wasted, representing approximately 1.3 billion tons per year, valued at around USD

${\$} $ The most common waste of fruit and vegetable by-products, including seeds, pulp, skins, or pomace, which make up 10%–35% of the raw mass, as well as roots and tubers, with residues ranging from 40%–50% of the total discards[11]. Interestingly, the waste generated from fruit and vegetable processing contains valuable bioactive substances with functional properties, such as antioxidants and antibacterial compounds. This presents an opportunity for economic recovery through the utilization of these wastes in various industries. For instance, fruit and vegetable waste can be used as ingredients, food bioactive compounds, and biofuels[9] .

On a global scale, fruits and vegetables rank the most wasted food categories, with over 40% lost annually due to deterioration, inefficient supply chains, and consumer behaviour. The World Resources Institute has emphasized that curtailing such waste could result in savings of up to USD

${\$} $ Fruit and vegetable waste significantly influences economic and environmental losses in the US. According to the USDA's '2030 Champions' initiative, the US food industry faces substantial challenges with post-harvest and retail-level food losses, particularly for perishable items like fruits and vegetables. In 2022 alone, programs such as Amazon Fresh and Whole Foods diverted over 108,000 tons of food waste from landfills, transmitting it to sustainable uses, such as composting or anaerobic digestion. These efforts support broader goals to decrease food waste by 2030, reflecting a focus on optimizing distribution systems, enhancing food recovery, and minimizing waste through technological advancements[12].

Although fruit and vegetable wastes and by-products result in significant economic losses, there is a need to establish their potential value. Implementing circular business models and sustainable waste management practices can mitigate these losses and create new economic opportunities[13].

-

By-products from fruits and vegetables are rich in beneficial compounds including phenolics, carotenoids, and other bioactive substances. These residual materials contain phytochemicals that provide a range of health benefits such as antibacterial, antidiabetic, and cardioprotective effects, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticarcinogenic properties that contribute to their diverse health benefits[14]. Bitter gourd, a traditional vegetable, has byproducts peel, flesh, and seeds with significant involvement in antibacterial, antihyperglycemic, and antihyperlipidemic. Pharmaceutical foods capable of promoting health can also benefit from these products[15].

Byproducts of pomegranates and grapes are rich in phenolic compounds and antioxidants and are commonly used in abundant food products. Incorporating these byproducts into foods increases the content of bioactive substances and dietary fiber, helping to minimize oxidation inhibit microbial growth, and increase the compositional and sensory evaluation of food products[16]. Among all food wastes, roots, tubers, and oilseeds account for the largest portion, accounting for approximately 25% of all vegetables and fruits, constituting 21% of the total food consumption. The next highest contributors are cereals and pulses, accounting for 14% of dietary intake[17].

Grapefruit pomace, abundant in antioxidants, such as phenolics, flavonoids, and carotenoids, shows considerable promise as a functional ingredient that can be incorporated into various food products[18]. The concentration of phenolic compounds varies depending on the specific part of the material in avocados, the seed or pulp has less, and peelings have a higher phenolic compound[19]. Bioactive compounds are rich in the seeds of fruits, and mango peels exhibit significantly higher total phenolic content (92.6 mg GAE/g) than flesh (27.8 mg GAE/g), regardless of fruit ripeness[20].

The food production sector produces between 40% and 50% of plant-related waste and byproducts. These include various parts of fruits and vegetables such as peels, skins, shells, roots, branches, stones, and seeds[21]. Among all fruits and vegetables, mangoes produced the most waste (60%), followed by citrus fruits (50%), fury fruit (45%), ananas (33%), and both pomegranates and legumes (40%). Bananas, apples, grapes, potatoes, and tomatoes also contribute to overall waste production in this industry[22].

Almost 30% of date palm crops are lost during harvest, storage, and conditioning. Lower-grade dates and inedible components recovered during harvest can provide economic benefit to farmers and the food industry economically by integrating nutritional content into products[23]. Including these waste and by-products into the food supply addresses economic and ecological concerns, while potentially enhancing consumer appeal through beneficial components. However, most studies have evaluated the in vivo effects, bioavailability, and toxicity of these novel products, which are essential factors for determining their safety and possible health benefits[22].

-

Fruit and vegetable by-products are assessed on their nutrients and health-promoting compounds in their natural form. However, the waste produced from these foods has become a major issue, leading to environmental issues, economic losses, and wasted nutritional value[24]. Extraction technologies suitable for bioactive compound processing, such as microwave-assisted extraction, pressurized liquid extraction, and subcritical water extraction provide extra advantages and can be a substitute for traditional methods because of their efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and eco-friendliness[25].

Microwave-assisted extraction

-

Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) is a highly effective technique for extracting bioactive chemicals from fruit and vegetable waste and by-products. The primary use of this method is extraction, as it effectively minimizes the amount of solvent needed, decreases energy consumption, shortens extraction periods, and enhances extraction efficiency and selectivity. As a result, it yields high-quality target products[26]. Different studies have utilized MAE methods to extract pectin from various fruit waste materials, such as longan seed, tomato skin waste[27], apple pomace[28], banana skin[29], pitaya and passion fruit peel[30], lemon, mandarin, and kiwi peel[31].

The study found that the highest microwave power used on the fruit waste, specifically sour cherry pomace, was 700 W[32]. This process can also be used to obtain other biochemical substances, including antioxidants from black carrot pomace, and mango seed kernels as well as pitaya peel, and flavonoids from jocote[33]. Table 1 represents the utilization in recent studies on fruit and vegetable byproducts for the extraction of bioactive compounds.

Table 1. The utilization of MAE of fruit and vegetable waste for bioactive compounds.

Fruit and vegetable

by-productsBioactive compounds Process conditions Agent Optimum yield Ref. Dragon fruit peels and passion fruit peel Pectin 10–12 min, 75 °C,

(153–218) WMethanol and specific pH (2.9–3.0) Red dragon fruit (17.01% ± 0.32%), white dragon fruit: (13.22% ± 1.42%), passion fruit: (18.73% ± 0.06%) [30] Black carrot pomace Antioxidants, anthocyanins, phenolics 5 min, 110 °C,

output 20%, 900 WHot acidic water and

pH 2.5Phenolic compounds (1692 ± 79.4 mg GAE/l) and antioxidants: (60 ± 9.6 MTE/mL) anthocyanins value is (456.8 ± 38.2 mg/L) [34] Longan seeds Pectin 3.5 min, 700 W 50% ethanol as a processing agent Good yield of pectin and 64.95 + 20.56 mg GAE/g dw phenolic contents [35] Peels of lemon, mandarin, and kiwi Pectin 1–3 min, 60–75 °C,

360–600 WNitric acid (HCl) Lemon: 7.31%; mandarin: 7.47%; kiwi: 17.97% [31] Apple, orange and mango peel, carrot pulp Pectin 10–180 min, 90 °C,

50–200 WWater orange peel: 12.9% ± 1.0%; mango peel: 14.7% ± 0.6%; apple pomace: 14.7% ± 0.1%; carrot pulp:

6.3% ± 0.7%[36] Black carrot pomace Phenolics, flavonoids, and anthocyanins 9.8 min, 348.07 W 20% ethanol used as a processing agent Polyphenolic (264.9 ± 10.02) mg GAE/100 mL; flavonoid: (1662.2 ± 47.3) mgQE/L; anthocyanins (753.4 ± 31.6) mg/L [33] Lemon peel Essential oil, pigment 50 min, 20 °C/min, 500 W 80% methanol Essential oil: 2 wt.%; pigment: 6 wt.% [37] Mango peel extract Phenolic compound, antioxidant 360 W for 20 s Ethanol : water ratio of 20:80 The total phenol content and antioxidant activity of the extracts increased significantly [38] To achieve the maximum amount of the desired molecule, microwave-assisted extraction is suggested instead of conventional or domestic microwave ovens. Microwave-assisted extraction allows for the monitoring of important parameters such as pressure and temperature[39]. The study examined the impact of microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), and ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) on pectin extraction and chemical properties in banana peels. The impact of microwave power on MAE examined the effects of extraction time on pectin production and quality. Increased microwave power and extraction time led to higher pectin production and chemical properties. Yield percentages ranged from 20.93% to 22.91% for microwaves at 300 W for 5−15 min. MAE-extracted pectin contained moisture, ash, esterification, methoxyl, and galacturonic content of 8.98%, 5.40%, 75.50%, 12.00%, and 57.80%, respectively. The study examined the impact of temperature and sonication time on pectin yield and quality in ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE)[40].

Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE)

-

UAE is an efficient and rapid method for enhancing pectin and other organic compounds yield. In UAE, the collapse of bubbles of cavitation induced by the movement of sonic waves produces a substantial force of shear. The biological membranes rupture, causing extractable chemicals to be swiftly discharged into the medium as the bubble collapses. The solvent effectively infiltrates cellular materials, which improves mass transfer, shortens processing times, and boosts the overall yield[41]. This method also leads to a decrease in the average molecular weight of the compounds involved, changes the level of methylation, breaks down neutral sugar side chains, enhances antioxidant activity, and alters both the flow properties and pectin structure[42].

Different studies suggested that high amounts of pectin from different resources with Algerian dates[43], apple peel[44], custard apple peel[45], and walnut processing wastes[46]. Specifically from apple peels and jackfruit rind, organic acids have demonstrated great pectin production[47] durian and citrus peels responded better to mineral acids[48,49]. The use of citric acid along with ultrasound-assisted extraction showed increased pectin production from lime and mango peels[50]. Another study found that using citric acid from satsuma mandarin peels, combined with high hydrostatic pressure, resulted in a higher pectin yield compared to traditional methods[51].

It was found that utilizing hot water for extracting pectin from sweet lime peels produced excellent outcomes, with nearly 24% of the pectin and a suitable gallic acid (71%) content[52]. The study compares the effectiveness of hydrochloric acid (HCl) and UAE (unsaturated fatty acid) in enhancing pectin yield from sweet lime and grapefruit peels. HCl yields high and compact pectin, while UAE enhances its bioactivity. The study also compares the structural, functional, antioxidant, hypoglycemic, and rheological properties of the extracted pectins[48,53]. Coriander leaves, flowers, and seeds are abundant in their nutritional components and bioactive compounds. Microwave drying and ultrasonic-assisted extraction are effective techniques for optimizing the retention of these constituents in powder and ethanolic extracts, respectively[54].

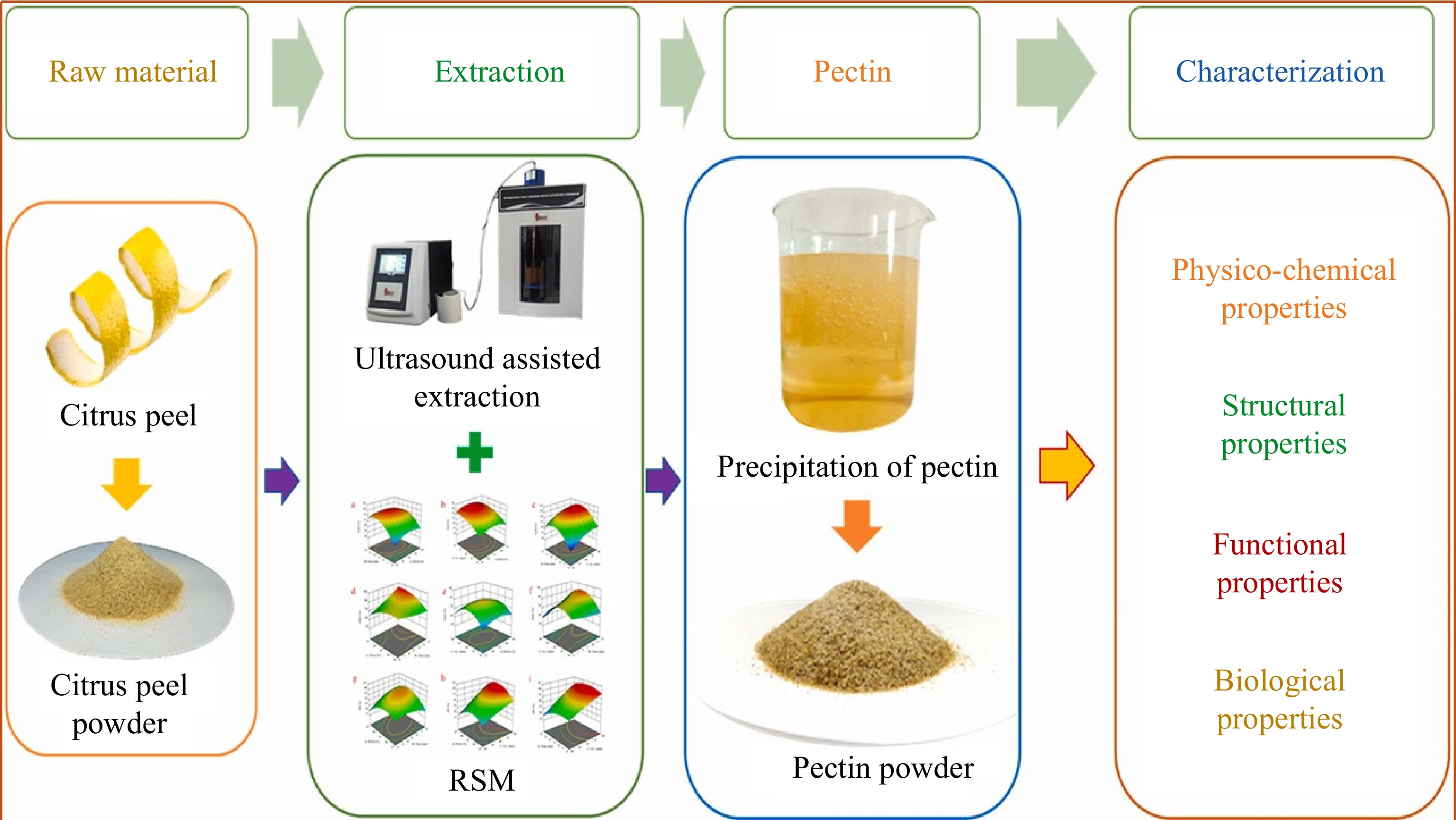

Figure 2 shows that the combined use of fine grinding, hydrochloric acid, and ultrasound-assisted extraction was determined to enhance pectin recovery. The UAE procedure was effectively optimized by applying the Response Surface Methodology, yielding high pectin (26.35%), high galacturonic acid content, (69.11%), and a low degree of methylation (22.14%) from pummelo peels. The fast extraction of pectin (9.38 min) by a combined approach utilizing ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and hydrochloric acid (HCl) may reduce the adverse effects of acid on the structural integrity and quality of pectin[55]. Conversely, the use of industrial potato peel by-products resulted in higher yields of antioxidant extraction compared to combinations with ultrasound treatment[56]. UAE extraction efficiently extracts bioactive compounds from fruit and vegetable waste, offering high yields, purity, and bioactivity, beneficial for the food, and pharmacy industries[56].

Figure 2.

Ultrasound-assisted extraction for pectin from citrus peel[55].

Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE)

-

PLE is an eco-friendly and efficient method for extracting bioactive components from fruit and vegetable residues and by-products[57]. The PLE method was used for bioactive components from pomegranate peel using a mixture of pressurized water and ethanol to identify the ideal PLE conditions, specifically the ethanol concentration and processing temperature, to achieve a pomegranate peel extract with maximal total phenolic content, punicalagin concentration, and antimicrobial activity. The total phenolic content and punicalagin concentration of PPE-PLE acquired under optimum circumstances were 164.3 ± 10.7 mg GAE/g DW and 17 ± 3.6 mg/g DW, respectively. Our findings indicate that PLE is effective for TPC recovery, but not for punicalagin recovery. The antimicrobial activity against S. aureus was 14 mm[58].

The acai by-product constitutes 80%–90% of the berry's bulk. To repurpose the by-product, pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) was employed at elevated temperatures (115 ºC) using a solvent mixture of ethanol and water (75 wt%) to enhance the acquisition of antioxidant extracts. The PLE conditions were subjected to kinetic analysis and economic assessment. The conclusion of the initial theoretical extraction period (t CER) yielded the extracts' lowest cost of manufacturing (COM). PLE has demonstrated both technological and economic viability in extracting acai by-product extracts with verified antioxidant properties[59]. Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) and enhanced solvent extraction (ESE) are two applications for jute fiber that generate bioactive food packaging materials. The extraction yield and antioxidant capacity of red grape pomace extract (RGPE) were achieved using two different methods: ESE (enhanced solvent extraction) and PLE (pressurized liquid extraction). The changes were validated by altering the pressure (10 and 20 MPa), temperature (55−70 °C), and co-solvent conditions (C2H5OH : H2O). PLE yields the maximum bioactive extract at a pressure of 20 MPa, temperature of 55 °C, and time of 1 h. The extraction solvent utilized is a combination of C2H5OH and H2O, which showed antibacterial activity against pathogens such as E. coli[60]. Table 2 demonstrates several studies of fruit and vegetable waste and by-product extraction of bioactive components by pressurized liquid extraction.

Table 2. Studies of fruit and vegetable by-products PLE extraction for organic compounds.

Fruit and vegetable

by-productsOrganic compounds Extraction condition Solvent Optimum yield Ref. Skin and seed of grape pomace Polyphenols and antioxidants contents 5 min, 100–160 °C, 10 atm, 250 s nitrogen purge 20%–60% ethanol Phenolic compounds of skin: 1.98 mg GAE/g DW, seed: 12.54 mg GAE/g DW [61] Pomegranate peel Punicalagin and total phenolic content 200 °C 77% ethanol TPC: 164.3 mg GAE/gDW, punicalagin: 17 mg/g DW [62] Olive pomace Total phenolic and flavonoid content, aminooxy acetic acid, 65–180 °C, supercritical CO2 80%–92% ethanol TPC: 280.37 mg GAE/g DE, AOA: 6.88 MTE/g DE [58] Beetroot by-products and residues TPC, aminooxy acetic acid 7.5–12.5 MPa, 3 mL/min, 40 °C 70%–100% ethanol Total phenolic content in leaves: 252 mg GAE/g, AOA: 823 MTE/g [63] Sub-critical water extraction (SWE)

-

Subcritical water extraction is an advanced technology that offers remarkable benefits in the potential to efficiently process fresh raw materials to produce natural valuable products sustainably. The effectiveness of this approach in extracting lipophilic components from plant biomass using water is well recognized and has recently produced renewed interest[64]. The sub-critical water extraction method produces high-quality extracts and is cost-effective, quick, and betters traditional extraction methods[64,65].

The conditions for SWE were optimized to get the highest pectin yield from cocoa pod husk (CPH). The features of CPH pectin extracted using SWE were then compared with those of CPH pectin produced using conventional extraction (CE) with citric acid. The optimum extraction conditions of 120 °C for 10 min with 1:15 g/mL resulted in a maximum pectin yield of 6.58%, which closely matched the expected value of 7.29%. In comparison to CE, SWE exhibited a greater yield and provided a better level of esterification, methoxyl content, and anhydrouronic acid value, but with a reduced equivalent weight[65].

Another study examined how extraction temperature (95−155 °C), and time (20−100 min) affected yield and purity. The crude extract and a concentrate at 1/6 of the original volume were tested for yield and purity according to extract pH and alcohol content. Ultrafiltration through ceramic hollow fiber membranes is concentrated. After precipitation with 70% alcohol, the concentration was purest at 96%. SWE extraction and ultrafiltration can produce hemicellulose from fruit waste for material uses[66]. Table 3 shows the different studies of fruit and vegetable by-products involving sub-critical water extraction.

Table 3. Progress studies of fruit and vegetable waste involving SWE extraction.

Fruit/vegetable

by-productsBioactive compounds Process conditions Agent Optimum yield Ref. Grape pomace Phenolics, flavonoids 50-190 °C Water Extract phenolic compounds: 29 g/100 g extracts [67] Citrus peel Total flavonoid content 145–175 °C, 15 min Water

TFC: 59,490 g/gdb[68] Dates by product

(seed)Total phenolic content, aminooxy acetic acid, TFC, dietary fiber 120–180 °C for 10–30 min, and 144 °C for 18.4 min Aqueous mixture TPC: (9.97 mg GAE/g), TFC: (3.52 mg QE/g), AOA:(1.67 mg TE/g) and dietary fibers: 29 g/mg [69]

Peel of kiwifruit

Aminooxyacetic acid, total phenolic and flavonoid content120–160 °C for 5–30 min, and 160 °C for 20 min Aqueous mixture TPC: (51.24 mg GAE/gdw), TFC:

(22.49 mg CE/gde),

AOA: (269.4 mM TE/gdw)[70] Tamarind seed Xyloglucan component, TPC, aminooxy acetic acid 100–200 °C (175 °C), 5.03–13.55 min Water Xyloglucan (62.28%),

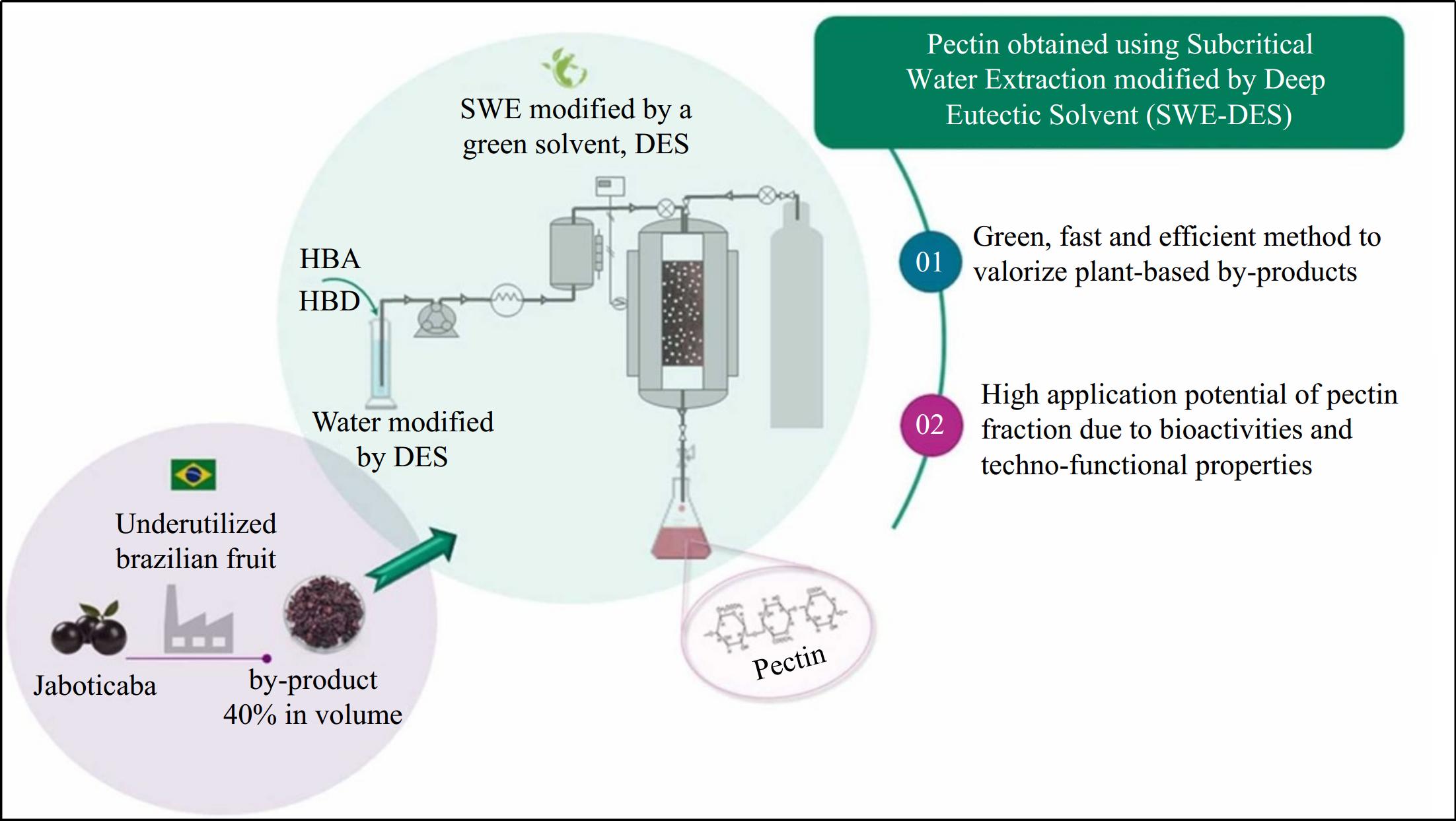

TPC: (14.65–42.00 gGAE/g), and AOA: (1.93–3.20 MTE/g)[71] Figure 3 demonstrates the extraction of pectin from jaboticaba by-products using the subcritical water extraction modified with deep eutectic solvent (SWE-DES). The operational parameters were optimized using response surface methods, resulting in 122 °C, 8% DES, and a flow rate of 2 mL/min. SWE yields are 1.5 to 1.8 times greater than those from standard extraction methods. When SWE-DES was used and increased the yield of pectin, the galic acid content, antioxidant capacity, and stability of the emulsion were all higher than in the control group[72].

Figure 3.

High-potential of extrtacting pectin from plant-based by-products[72].

-

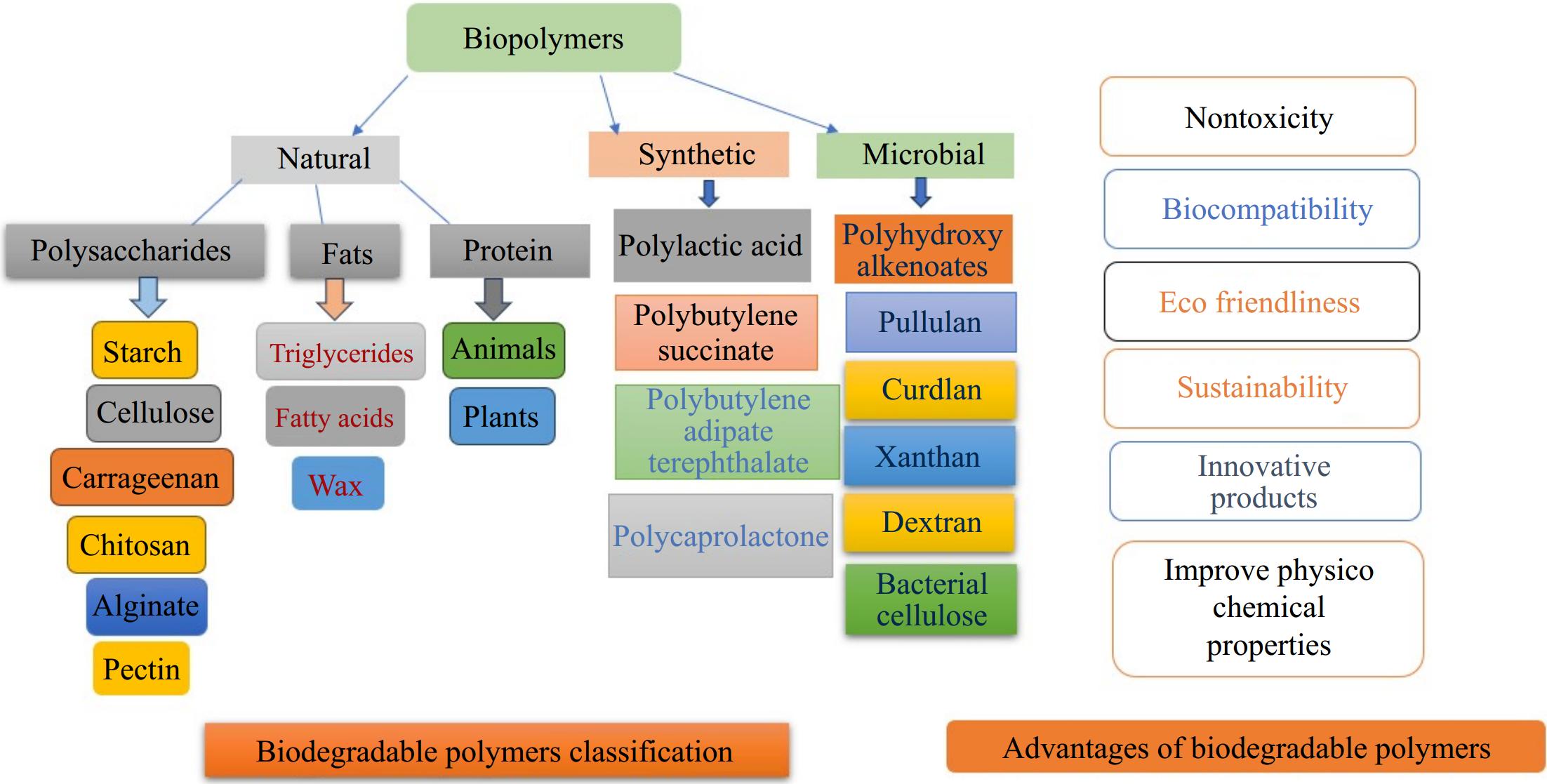

The selection of suitable materials is essential for producing eco-friendly, biodegradable films, and coatings. The best biomaterials including polysaccharides, starch, pectin, chitosan, cellulose, and alginates, biodegradable proteins, such as gelatin, casein, gluten[73], lipids, oils, and waxes enhance the effectiveness of packaging materials[74]. Sustainable alternatives to nondegradable packaging materials have emerged as biodegradable packaging materials derived from biopolymers, attracting significant concentration[75]. The classification of polymers is determined by their origin from natural, synthetic, and microbial fermentation have some advantages, which are also listed in Fig. 4[76,77].

Biopolymer packaging films provide significant benefits to the food industry due to their non-toxic nature and efficient regulation of water vapor, oxygen, and fat in food products, thus enhancing agricultural markets by preserving food quality extending shelf life, and assisting the delivery of active elements such as antimicrobials, antioxidants, and nutrients are key advantages of biopolymers[78]. Fruit and vegetable processing yields valuable byproducts that are used as biodegradable biopolymers to enhance artificial materials with bioactive compounds and nutrients in food products[79].

Polysaccharides, which are complex molecules derived from carbohydrates, are chains of monosaccharide subunits. They, along with proteins, are crucial in films/coatings owing to their biodegradability[80]. Important polysaccharides, including cellulose, starch, xanthan, chitosan, inulin, pectin, and sodium alginate, act as barriers. Cellulose, which is found in high-fiber plants by-products such as sugarcane, fruit and vegetable peels, and starch in sweet potatoes, beans, peas, and algae. Cellulose is cost-effective, microscopic crystals extracted from various plant-based waste materials exhibit desirable mechanical properties and eco-friendly attributes[7]. The potential of bioplastics composed of chitosan and cellulose nanocrystals, derived from mango waste and combined with polyvinyl alcohol, as effective films for packaging[81].

Although certain bioplastics may exhibit adverse effects related to moisture sensitivity, future research should focus on operational improvements. These limitations have prompted a global shift towards environmentally benign materials or biocomposites comprising a mixture of food waste. The utilization of various fruit- and vegetable-based substances as potential films for bio-packaging has gathered significant attention from researchers aiming to develop viable alternatives to conventional plastics[82].

The research developed a biodegradable packaging film using orange peel that has high cellulose content and is plasticized with glycerol, shows promising results, exhibiting strong durability, flexibility, and biodegradability, even in stained conditions, as indicated by its rough surface[83]. In polysaccharide-based systems, essential oils contribute antioxidant and antibacterial properties. Polysaccharide-based biodegradable materials improve mechanical, and thermal qualities while lowering production costs[84].

Starch, which is widely available in nature, is a crucial energy source for both animals and humans. It is composed of two main elements: amylose, which consists of D-glucose residues connected in straight alpha-(1-4) configurations, and amylopectin, which accounts for approximately 6% and is distinguished by alpha-(1-6) bonds that create branches in the primary structure. When exposed to specific conditions involving plasticizers, high temperatures, and mechanical forces, starch displays thermoplastic qualities, comprising water-insoluble components with various forms, structures, and crystalline arrangements[85].

Research found that making bioplastic varieties derived from banana peel starch, incorporates potato peel powder, and wood dust powder, along with glycerol as a plasticizing agent. The findings showed enhanced water absorption and the weakest tensile strength across 12 specimens, each containing varying quantities and mixtures of fillers and plasticizers[86].

Starch is recognized for its cost-effectiveness and adaptability and starch-made films face several challenges, incorporating limited thickness, pliability, clarity, poor mechanical characteristics, and high permeability to water vapour. These drawbacks have hindered the extensive application of starch-based films in manufacturing[87]. Biodegradable starch-based food packaging helps to reduce waste and environmental pollution. Enhancing starch-derived products needs further exploration with regards to biopolymer or additive addition, and different manufacturing techniques[87].

Plant cell walls contain numerous colloidal pectin heteropolysaccharides, which are commonly found in waste from food processing and biomass by-products. Pectin extracted from waste materials acts as a polymeric substance for active packaging, offering additional advantages[87]. It increases viscosity, provides stability, improves texture, and forms gel-like structures[88]. Pectin also enhances the antioxidant and antibacterial properties of substances added to functional packaging and is compatible with proteins, lipids, and polysaccharides[3].

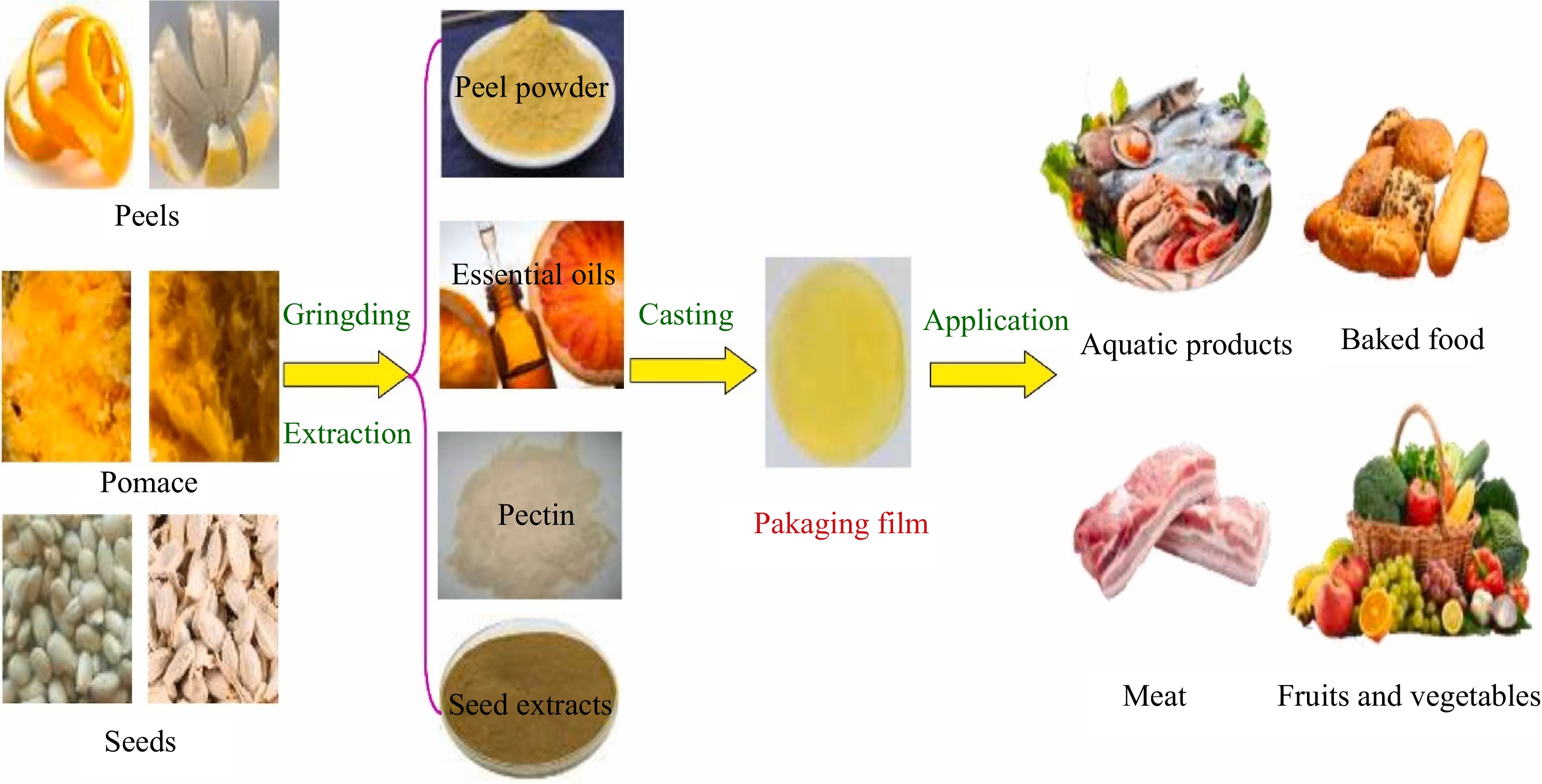

Commercial pectin is primarily derived from byproducts of fruit juice production and citrus peels. Research indicates that pectin can be extracted from various sources, including citrus peels, apple pulp, beet pulp, watermelon peel, pomegranate peel, and pumpkin[89]. Figure 5 illustrates that citrus peels and pomace are rich in pectin and can be used as a matrix for food packaging films. Citrus pectin provides good solid support for natural active compounds. Packaging films have a wide range of applications in extending the shelf-life of food products.

Figure 5.

Citrus peels/pomace rich in pectin and used as food packaging films[90].

Food packaging films have been developed using the peel powder of citrus fruits such as oranges, lemons, limes, and pomelos. The high pectin and cellulose contents in citrus peel powder allow it to function as a film matrix. When used in smaller quantities, citrus peel powder increases the tensile strength of the films owing to the adhesive interactions with the matrix. However, extreme quantities can indicate particle clumping, potentially reducing the films' tensile strength and their ability to stretch water vapor and oxygen[90]. Higher concentrations of citrus peel powder increase light barrier properties, thermal stability, and antioxidant and antibacterial capabilities[91].

A molding technique is used to produce edible composite films using a combination of egg albumin, casein, and pectin extracted from red pomelo peel. Composite films were formed by varying the proportions of the three components. The incorporation of pectin into the composite films resulted in crack-free structures, indicating proper homogeneity without phase separation and a decrease in the level of disorder within the films the addition of pectin enhanced their thermal stability[92].

-

Packaging films can be manufactured using biopolymers extracted from fruit and vegetable wastes. These packaging films normally demonstrate good mechanical and physical characteristics. Towards these limitations, the addition of bioactive components attained from food waste and these components may boost and enhance the inferior properties[92]. Several variables contribute to the external forces and pressures that affect biopolymers. these include the physical configuration, chemical composition, crystalline structure, molecular mass, and kind of polymer[93].

The physical-mechanical properties of films are modified when various polymers are incorporated through each other. The quality of composite films is enhanced by combining proteins like milk protein, collagen, gelatin, and gluten with polysaccharides such as chitosan, alginate, and cellulose[94]. Pomegranate and grape seed, peel waste improved the functional properties of the films obtained from silver carp surimi gels. These films present decreased solubility, increased filminess, less elasticity, and higher tensile strength, suggesting a link between the phenolic compounds and the film matrix and lower water absorption[95].

A film was created with a mixture of proteins, pectin, CeO2 nanoparticles, and cardamom extract. It showed strong mechanical properties, moisture resistance, and photocatalytic characteristics, resulting in improved stability and antimicrobial effects and providing a sustainable and adaptable alternative for packaging[96]. The combination of different materials such as emulsifiers, surfactants, plasticizers, and strengthening agents enhances the physiological properties, improved stability, increased flexibility, and enhanced characteristics of biodegradable films[94]. To prevent polymer collapsing, non-volatile substances are used as plasticizers decreasing intermolecular hydrogen bonding, strengthening and linking polymer chains, and promoting plasticity, and extension[97].

A previous study examined films composed of chitosan and peel extracts from blueberries red grapes and carboxymethyl cellulose. The peel extracts have antioxidant and antibacterial properties and improve the physical, mechanical, and barrier properties of edible films. The biodegradable films showed excellent antioxidant capabilities and effectively controlled oxygen permeabilities[98]. A nanocomposite film was created using apple peel pectin, potato starch, and zinc oxide particles with Zataria multiflora essential oil encapsulation. This film showed antimicrobial and antioxidant potential, prolonging the shelf life of meat products and enhancing their physical characteristics[99].

Researchers have extracted, analyzed, and applied starch from jackfruit seeds (JSS) and xyloglucan from tamarind kernels (XG) to develop biodegradable packaging materials. JSS/XG nanocomposite films were fabricated by incorporating zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZNPs). The combination of JSS and XG reduced the hydrophilic properties of the composite films and improved their mechanical strengths[100]. Date palm pit extract was combined with alginate at different concentrations. Incorporating DPPE into alginate films decreased their solubility and surface wettability by 37%−64%. Additionally, it enhances the resistance to vaporization, flexible strength, and elongation at break and high solubility. The film containing 40% DPPE exhibited the least decline in phenolic content, antioxidant activity, and FRAP after three months[101].

-

Edible films serve as protective layers and advanced packaging solutions by altering various properties, such as strengthening mechanical features, decreasing permeability, enhancing barrier functions, generating an active antibacterial surface, and boosting heat-resistant[102]. The application of these films and coatings allows consumers to integrate them into food items, thus minimizing the negative impacts on food quality. For safety and biocompatibility reasons, edible materials are preferable for film production[103]. Packaging of food products serves multiple purposes, including inhibiting bacterial growth, enhancing protection against environmental factors and oxidation, preserving flavor, and masking unpleasant smells[104]. Contemporary innovation in packaging materials involves the incorporation of active components to enhance the quality and prolong the lifetime of the product[105].

However, the primary method for delaying and improving product durability using synthetical antioxidants, but their harmful impact on human well-being and high costs[106]. There is significant value in natural antioxidants and antimicrobial agents as bioactive elements in the development of packaging and edible coatings[107]. Biodegradable packaging materials can be developed through the integration of natural biopolymers from fruit and vegetable waste and by-products. This approach improves the functionality of packaging films and provides sustainable and eco-friendly packaging[108], and valuable resource natural polysaccharides[6]. The addition of fruit waste and by-products into packaging has numerous advantages, extended product shelf life, quality preservation, improved antioxidant capability, increased nutrient content, decreased lipid oxidation, and the preservation of sensory characteristics[109].

Consumable coatings, such as Arabic gum, garlic, ginger, and aloe vera gel, enhance the post-harvest quality and storage durability of the Gola guava. A mixture of garlic extract and gum Arabic particularly decreases discoloration and mass reduction, so extending the shelf life of guava and increasing total soluble solids[110]. A further study utilized finely milled vegetable waste to create a powder that, when treated with an HCl solution, showed mechanical qualities comparable with standard materials such as plastic, showing the importance of specific moisture control and mass reduction[111]. The research found that combining different ratios of corn starch and date pit powder increased film thickness, elasticity, phenolic content, and antioxidant properties while reducing the water solubility and vapour permeability. Scanning electron microscopy revealed that up to 30% date pit powder improved the morphological features of the films, ensuring that all films were environmentally degradable[112].

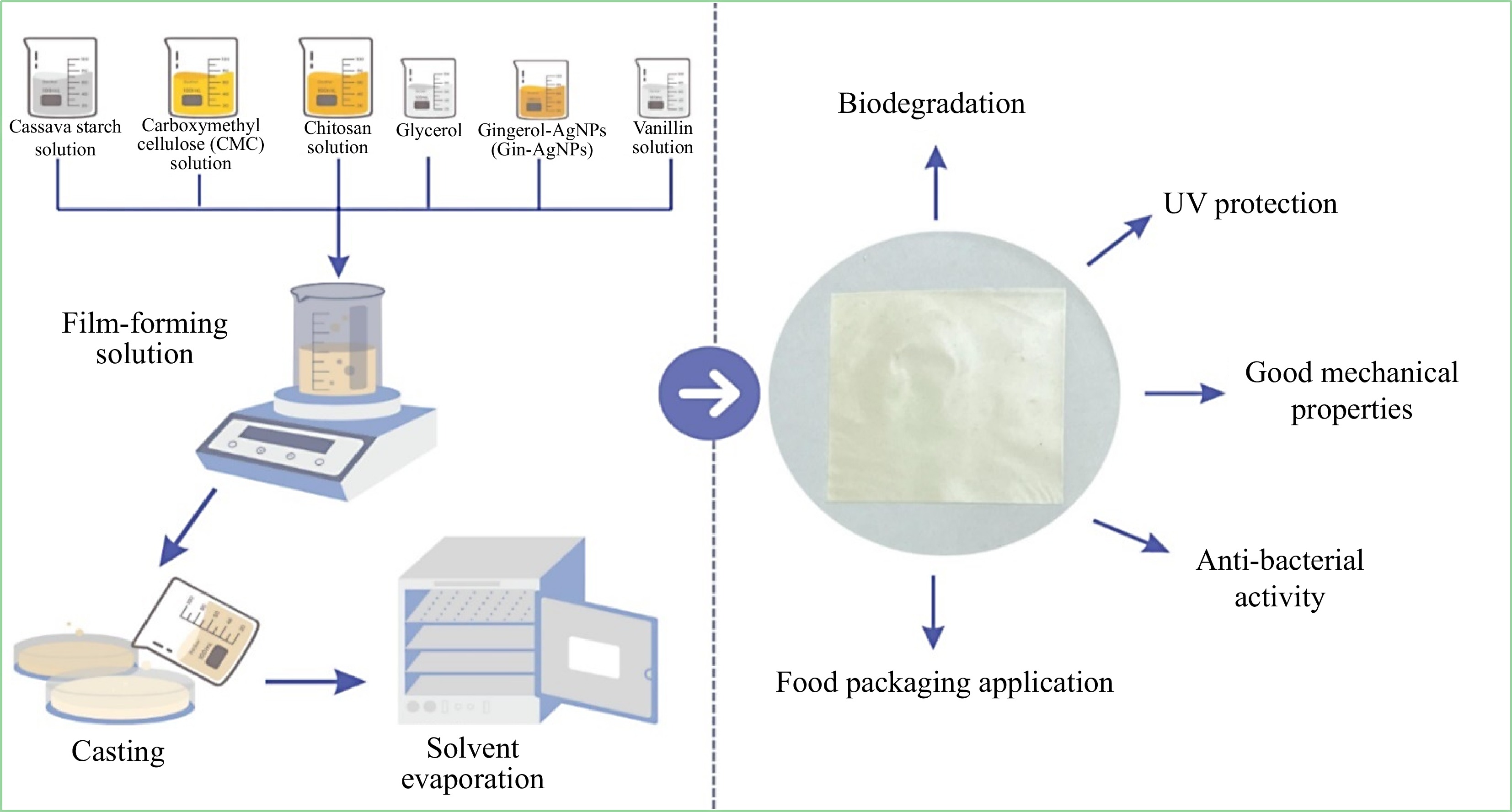

The development of antioxidant-enriched edible films derived from papaya with suitable drying parameters and incorporated Moringa leaf extract and ascorbic acid. A dehydrator was chosen for film production because of its efficient drying time and its ability to maintain its natural properties. The addition of both bioactive compounds affected the shelf-life stability of minimally processed pears, with ascorbic acid particularly influencing sensory acceptance[113]. Figure 6 shows that packaging films using cassava starch, chitosan, and carboxymethyl cellulose with glycerol as the plasticizer. These films need modifications to enhance their mechanical properties. The films for modification added vanillin as the crosslinking agent and gingerol extract-stabilized AgNPs. With these films, CT/CV/V/CMC/Gin-AgNPs1 showed superior mechanical and antibacterial properties. Table 4 illustrates the utilization of fruit and vegetable waste by-product biopolymers in films/coatings, highlighting their properties.

Table 4. Fruit and vegetable by-product polymers for increased properties of packaging materials.

Fruit/vegetable by-products Packaging film/

coating materialProperties of films Ref. Mulberry leaf Pectin Improve mechanical properties, effectiveness as barriers, antibacterial and antioxidant activity, extending storage life. [114] Citrus peel Pectin, cellulose nanofibrils Bioplastics have flexibility, gas barrier properties, antimicrobial activity, and an extended shelf life for bananas and mangoes. [115] Red pomelo peel pectin Casein, egg albumin The reduction of water vapour permeability and the increase in strength tension have enhanced film thermal stability. [92] Skin and seeds of pumpkin Protein, pectin improved mechanical and barrier properties [116] Palmyrah fruit fiber Cellulose nanofiber, starch Starch films with improved tensile strength, reduced water vapour transmission, and excellent biodegradability. [117] Fruit pectin Rubus chingii Hu. Pectin, Tara gum Increased water resistance, thickness, and mechanical properties. [118] Oil palm fruit bunch carboxymethyl cellulose Biodegradable microcarriers with enhanced mechanical stability, swelling properties, and biodegradability are applicable for therapeutic and industrial uses. [118] Orange peel Fish gelatin, pectin Increased resistance to spoilage, better preservation for cheese packaging. [119] Pumpkin seed Pea starch Enhance gas permeation resistance and stretchability while reducing tensile strength, and moisture absorption. Adding pumpkin seed starch improved water repellency and decreased film spreading out. [120] Berry leaf Material used sodium alginate Enhanced physicochemical characteristics, increased phenolic compounds, greater yield strength, and reduced length. [121] Bagasse extract Gelatin The shelf life of frozen beef is prolonged using active films. These functional films influence adequate physical and barrier properties, effectively inhibiting the oxidation of beef lipids and proteins. [122] Kiwifruit peel Pectin The film with watermelon peel pectin had superior tensile strength and Young's modulus. Increasing the kiwi peel extract concentration increased film turbidity, elongation, and water vapour permeability. [123] Pineapple peel Alginate /peel extract The preservation of bovine red meat colour was effectively attained through improved antioxidant and antibacterial properties. [103] Grape seed Pectin/seed extract Extended storage durability, enhanced physical attributes, increased antimicrobial activity and oxidative stress, and reduced sourness. [124] Sesame pulp Starch/pulp Reduction in spoilage indicators, and improved shelf life of beef under extremely low temperatures. [125]

Figure 6.

Cassava starch and other biopolymer films used for food packaging[126].

-

The addition of bioactive compounds derived from fruits and vegetables into packaging materials, such as films or wraps, inhibits microbial growth, and extends the food's product shelf-life[127]. Biodegradable packaging has an important role in food preservation and increases the storage durability of food products[128]. By utilizing by-products to create edible films or coatings, a protective layer developed on food surfaces and helps to reduce moisture loss, control gas exchange, and prevent microbiological contaminants[129].

Pectin, a by-product of fruit processing, is used to make edible film to encapsulate fruits and extend their storage life. Over 16 d of storage, fruit characteristics were evaluated and showed that guava fruit coated with these films remained fresh, reduced weight loss, and extended shelf life, although the uncoated fruit suffered from weight loss[130]. Another study integrated gelatin, chitosan, pectin, and fennel essential oil, which enhanced the film's peak elongation and tensile index. The films achieved elasticity from (14.03%−31.61%) and strength from (0.40−0.50 N·m/g), however, maintained the yellowish color and high filminess, extending food shelf-life, and reduced the risk of foodborne illnesses[131].

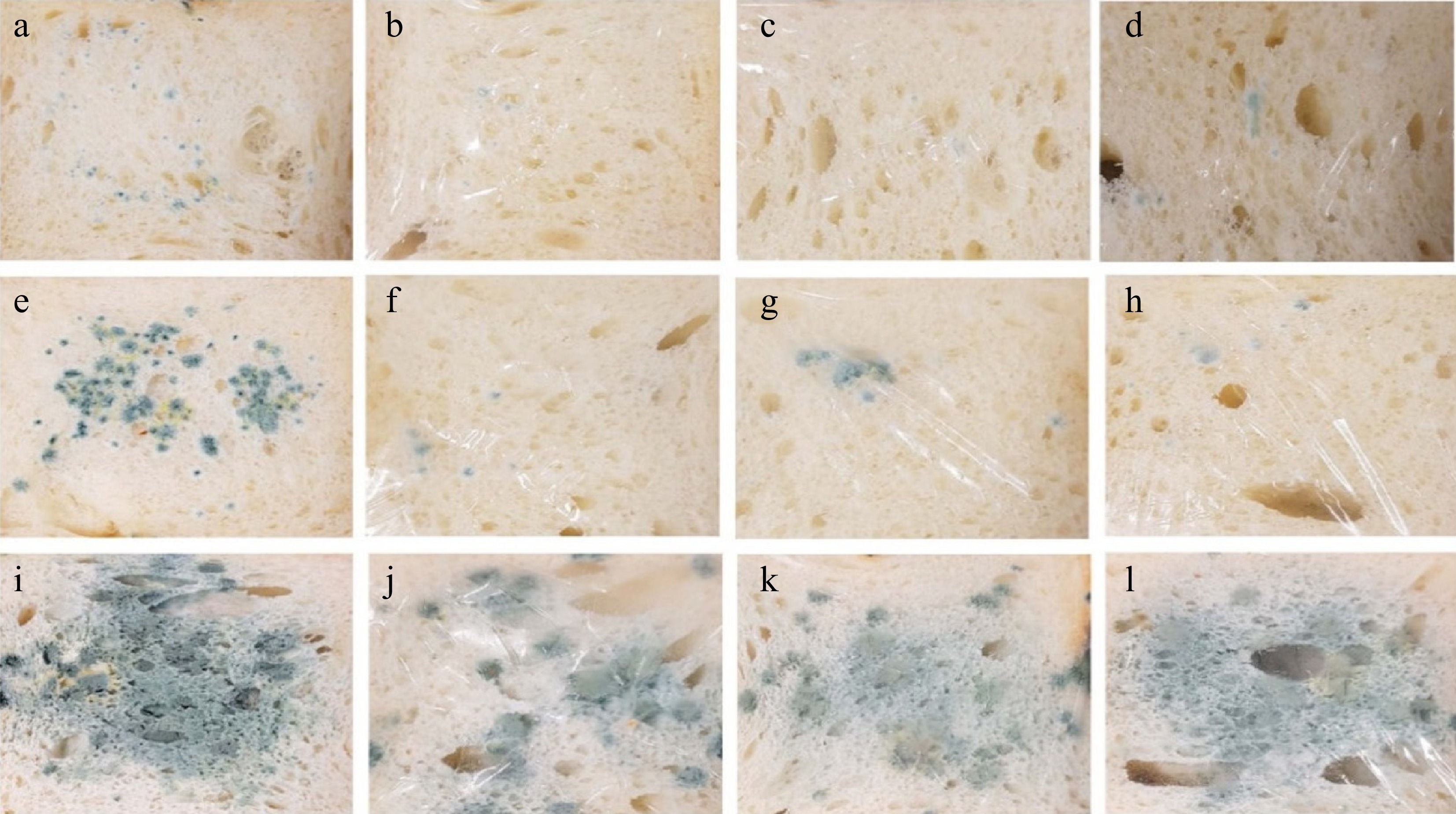

Moringa oleifera and its by-products are a versatile herbal used human food and a medical alternative all worldwide[132]. Figure 7 shows the effect of preparing a packaging film using moringa leaf/deep eutectic solvents/lactic acid (LA)/glycerol (GLY) and observed the self-life study (6, 7, and 11 d) of bread along with the fungus. The results showed the methylcellulose films enriched with moringa by-products cannot affect the storage of bread over a long time period[133].

Figure 7.

Growth of fungi in wheat bread: (a), (e), (i) control (unpacked); (b), (f), (j) with 2% film; (c), (g), (k) covered with DES-10% film; (d), (h), (l) with MO-10% film. (a)–(d) 6 d, (e)–(h) 7 d, (i)–(l) 11 d[36].

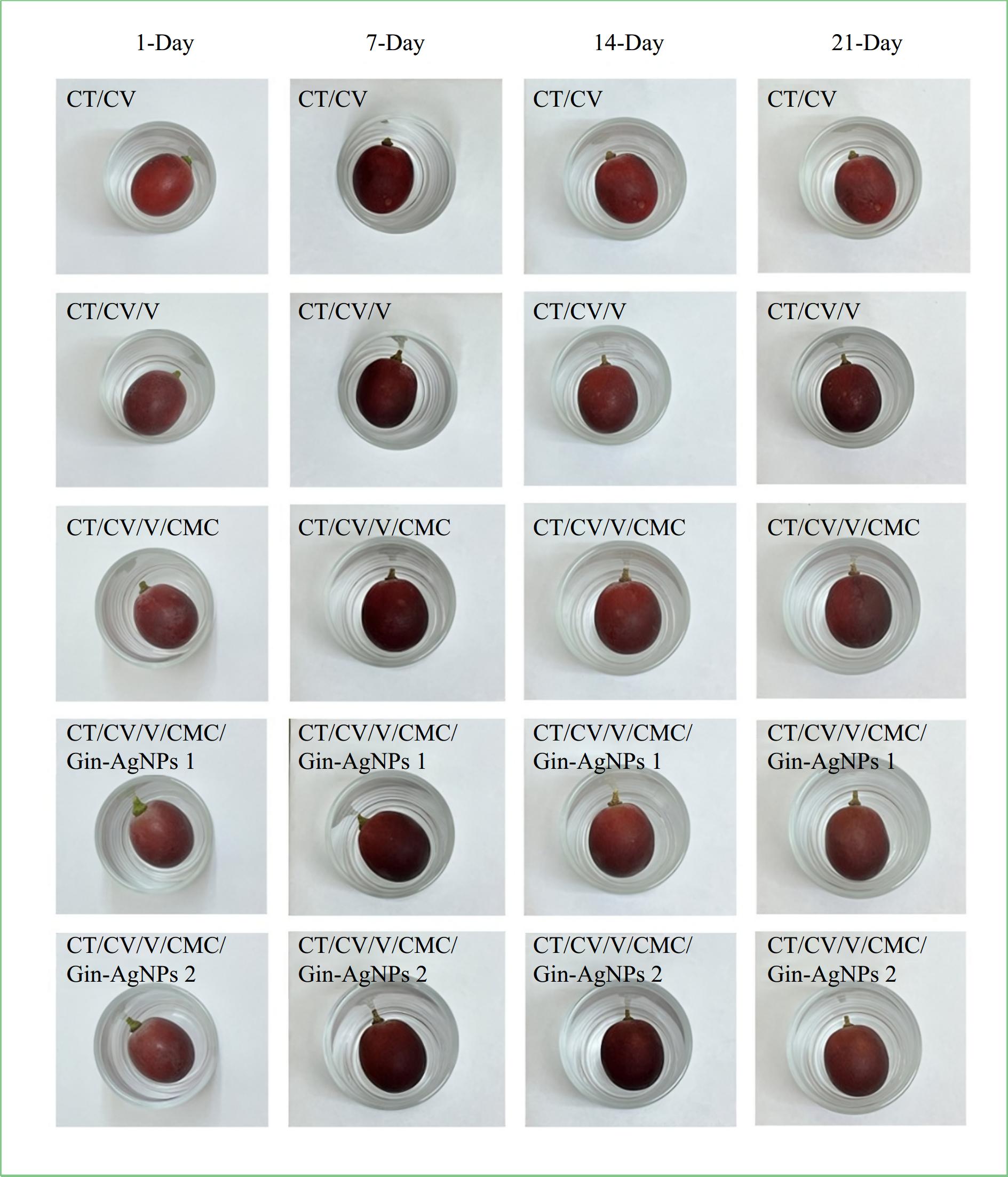

For developing packaging films (Fig. 8) using a combination of cassava starch (CV), chitosan (CT), and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), incorporating glycerol as a plasticizer. Among the various formulations tested, CT/CV/V/CMC/Gin-AgNPs1 stood out, displaying superior mechanical characteristics. This film also demonstrated significant antibacterial properties against both S. aureus and E. coli bacteria. Furthermore, it demonstrated excellent biodegradability, with over 50% weight loss after 21 d of soil burial. Additionally, the film effectively preserved the grapes at 4 °C for 21 d[126].

Figure 8.

Preserved grapes with CT/CV, CT/CV/V, CT/CV/V/CMC, CT/C V/V/CMC/Gin-AgNPs 1, and CT/CV/V/CMC/Gin-AgNPs 2 films for 1, 7, 14, and 21 d[126].

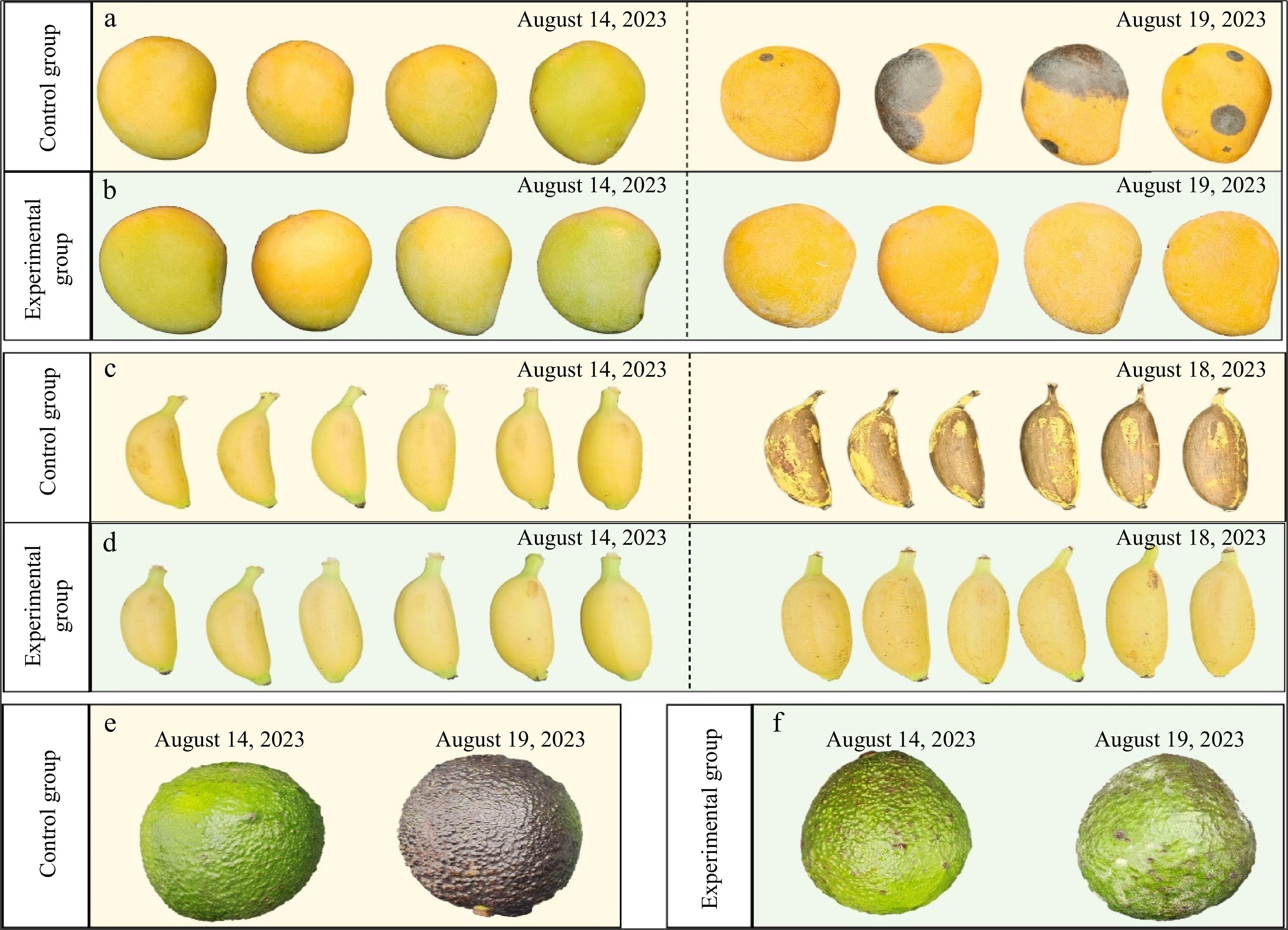

Biodegradable antimicrobial bioplastics for food packaging solutions to address environmental pollution and food safety issues associated with petrochemical plastics and food spoilage. Figure 9 demonstrates that naturally active bioplastic derived from citrus peel biomass can be used for preserving perishable fruits. These innovative plastics are observed by their nanoscale structure, which features linked and recombined hydrogen bonds among pectin, polyphenols, and cellulose micro/nanofibrils. The resulting material has good flexibility, tensile strength, gas barrier properties, and antimicrobial capabilities. After application in food packaging, these bioplastics effectively extend the shelf life of perishable fruits such as bananas and mangoes[115].

Figure 9.

Citrus peel biomaterials increase the shelf life of fresh fruits[115].

In another study, nanocomposite films derived from jackfruit seed starch and tamarind kernel xyloglucan demonstrated good antimicrobial properties. After application in tomato storage studies, it effectively slowed quality degradation and prolonged shelf-life. These nanocomposite films showed eco-friendly packaging materials for extending food product durability[100]. Further investigations are required for other foodstuffs, such as cheese and baked goods, focusing on packaged items' flavor and sensory characteristics. Essential oils from oregano, cinnamon, thyme, and rosemary contain natural compounds that efficiently inhibit Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and fungi[134].

-

The incorporation of organic compounds from fruit and vegetable byproducts enhances the properties of biodegradable films. These edible and biodegradable films and coatings have been developed as alternatives to non-biodegradable packaging materials. Biopolymer-based food packaging, including polysaccharides, carbohydrates, lipids, etc, are environmentally friendly options to plastics. By-products from industrial food processing have become valuable sources for generating cost-effective, biodegradable packaging materials. Advanced and green extraction technologies, such as microwave-assisted extraction, pressurized liquid extraction, and subcritical water extraction, provide additional benefits such as their efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and eco-friendliness. Incorporating food waste and by-products into packaging films enhances their fundamental characteristics, facilitates in controlling microbial growth, extends shelf life, and maintains the quality of packaged products. These packaging films or coating materials have good characteristics involving increased shelf life, food safety, biodegradability, recyclability, and environmental friendliness.

Some challenges however need to be overcome: enhancing the mechanical resistance, heat resistance, barrier characteristics, and production scalability of these by-products remains crucial. Researchers have investigated the combination of various protective substances such as nanoparticles, nanofibres, and essential oils to design multilayered biodegradable coating/films that address these limitations. Moreover, the combination of these by-products with other polymers and the use of extrusion techniques have been explored for industrial applications. Subsequently, the use of food waste and by-products to produce edible films from natural sources is considered safe and sustainable. Future advancements in this area should focus on enhancing the interactions between food and packaging while utilizing food discarded materials and by-products as effective sources.

The Faculty of Chemical and Process Engineering Technology, University of Malaysia Pahang, Al-sultan Abdullah, supported this work (Grant No RDU222802 & UIC220818). The authors thank Dr Noormazlinah Binti Ahmad for contributing to this work.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: writing - original draft, graphs, and tables: Ali MQ; Editing and review of the article, graphs, and tables: Ahmad N, Azhar MA, Munim MSA, Ruslan NF. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ali MQ, Ahmad N, Azhar MA, Munaim MSA, Ruslan NF. 2025. Fruit and vegetable by-products: extraction of bioactive compounds and utilization in food biodegradable material and packaging. Food Materials Research 5: e004 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0003

Fruit and vegetable by-products: extraction of bioactive compounds and utilization in food biodegradable material and packaging

- Received: 01 October 2024

- Revised: 02 January 2025

- Accepted: 17 February 2025

- Published online: 22 April 2025

Abstract: The detrimental effects of food waste and its by-products on the environment, economy, and society are significant. A sustainable solution to this problem implies the extraction of organic compounds from waste and by-products, with the development of food packaging materials. The use of edible and functional food packaging, food waste, and natural materials offers a sustainable method to minimize waste and plastic consumption. Fruit by-products are particularly valuable food wastes containing beneficial compounds such as polyphenols, vitamins, and minerals. Edible and biodegradable films composed of proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids can be utilized as substitutes for non-biodegradable packaging. By-product compounds are used in biodegradable packaging films because of their accessibility, low cost, eco-friendliness, physical properties, unique sensory and nutritional characteristics, and improved functionality. This study explored the potential applications of biopolymers, packaging materials, edible films, and coatings as substitutes for conventional food packaging. To enhance the physical, mechanical, and antimicrobial properties of packaging systems and improve synthetic and bio-based films enhanced with by-product compounds and their role in biodegradable food packaging.