-

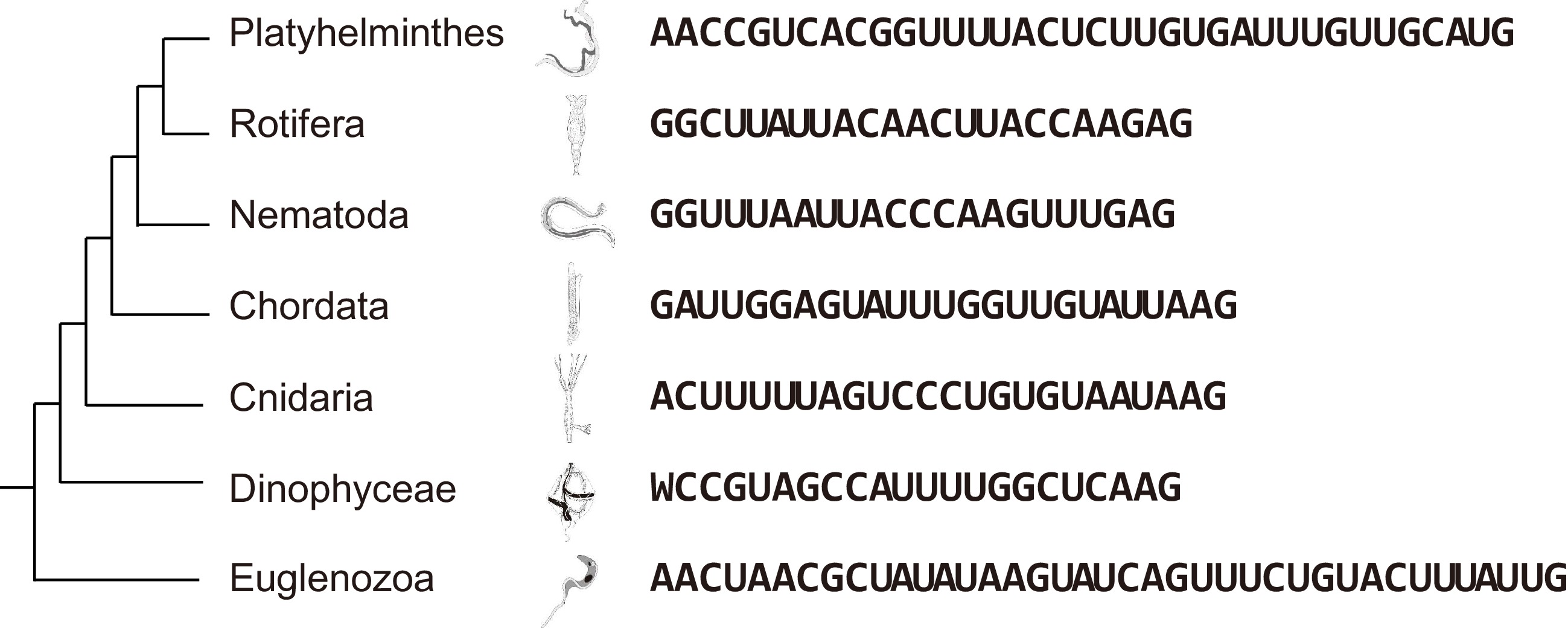

Trans-splicing has been documented in many lineages that are widely distributed phylogenetically, including nematodes, flatworms, cnidarians, rotifers, chordata, dinoflagellates, and euglenozoans (Fig. 1). The addition of a spliced leader (SL) sequence is required for the maturation of mRNAs in these organisms, many of them, such as trypanosomes, flatworms, and nematodes, are pathogenic to humans and some others, such as Dinoflagellates, are crucial in marine ecosystem as endosymbionts of coral or causal algae of harmful blooms. The functions of SL's are varied among different lineages and can involve polycistronic RNA processing, translation initiation, and alternative splicing of open reading frames (ORFs). For example, the 3'-terminal AUG of the flatworm SL provides a start codon to recipient mRNAs[1]. The nematode SL contributes a N-2,2,7-trimethylguanosine cap (TMG-cap) to more than 70% of the recipient mRNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans and Ascaris suum, and both the TMG-cap and the SL itself are required for efficient translation of mRNAs[2]. In Trypanosoma brucei, SL addition can have different consequences depending on the site of SL insertion. These consequences can include trimming of the start codon, truncation of ORFs, alteration of subcellular location by altering signal peptides, interruption, or introduction of upstream ORFs (uORFs), and creation of alternative ORFs[3]. Current thinking is that the SL function in translation initiation is sequence-dependent, with AUG addition requiring the presence of an AUG at the 3' terminal of SL, and TMG-cap addition requiring a guanine at the 5' terminal of SL sequences. However, SL sequences vary substantially between these lineages (Fig. 1), and most SL sequences do not contain a 5' end guanine or a 3' end AUG[4], suggesting these reported functions might be only specific to certain species and the general function of SL in many other organisms is still poorly understood. We have noticed that the 3' end of SL sequences all end with guanine and most are rich in A/G at this end (Fig. 1). This latter feature is reminiscent of the Kozak consensus sequence (gccRccAUGG) required for the selection of start codons for translation initiation. We therefore hypothesized that SL sequences could be involved in translation initiation by providing an improved Kozak consensus.

To test this hypothesis, we collected ribosome protected footprints (RPFs) of nematodes (C. elegans, C. brennei, and C. remanei), a euglenozan (T. brucei), and a dinoflagellate (Lingulodinium polyedra) from the literature[5−7] for comparison (Supplementary Table S1). RPFs with partial SL sequences allowed the identification of SL-containing RPFs (SL-RPFs) in L. polyedra (proportion of SL-RPFs: 1.08E-4), C. elegans (proportion of SL-RPFs: 0.75E-4), C. brennei (proportion of SL-RPFs: 5.17E-4), and C. remanei (proportion of SL-RPFs: 4.18E-4) but very few SL-RPFs were found in T. brucei (proportion of SL-RPFs: 0.05E-4) (Supplementary Table S2). Therefore, the T. brucei SL may not be involved in translation initiation but instead may help restructuring ORFs on the recipient mRNAs[3].

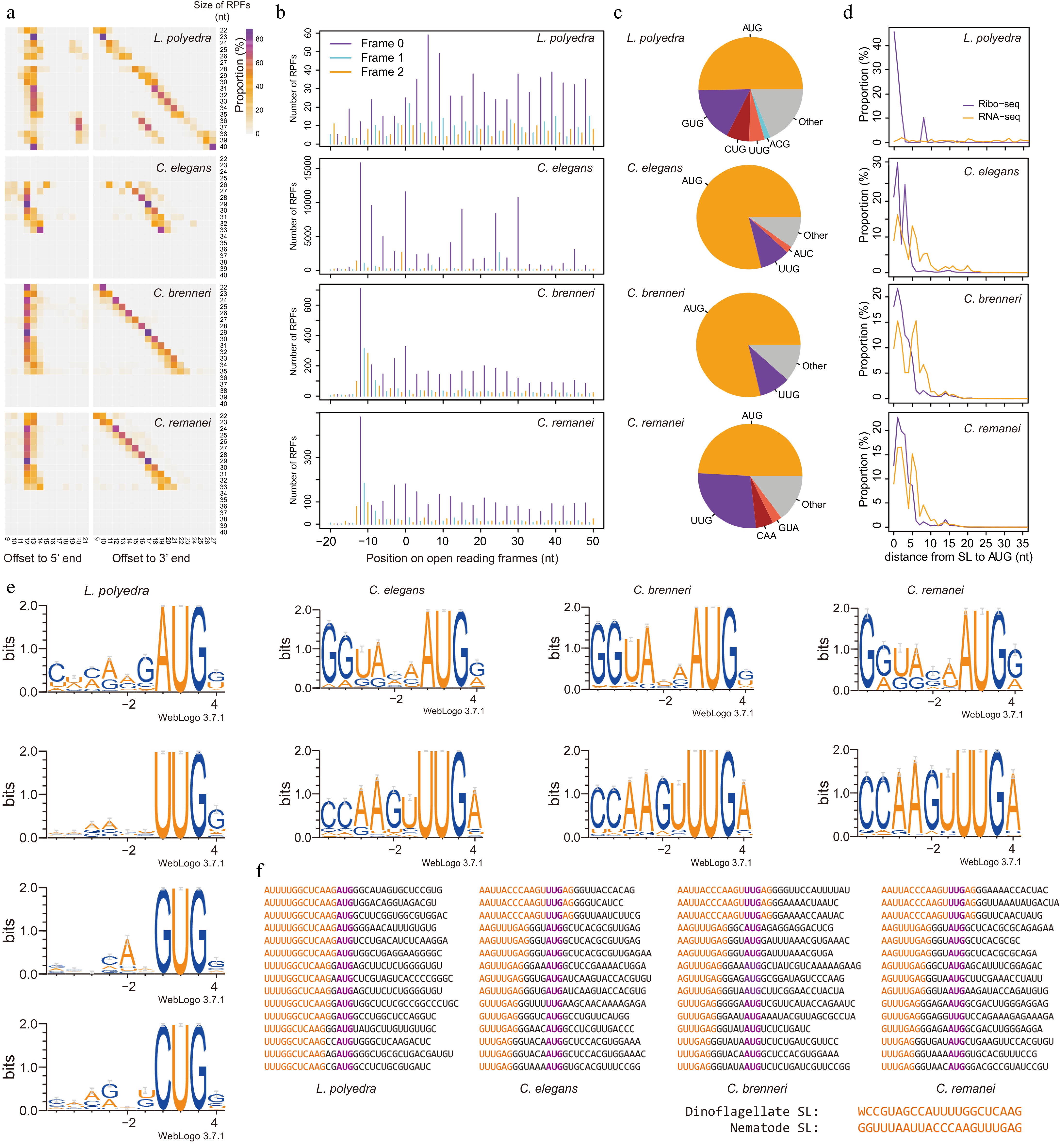

Since RPFs preferentially contain coding sequences, the presence of a 5' end SL sequence in RPFs suggests proximity to the initiation site. Interestingly, roughly half the dinoflagellate SL-RPFs contained an AUG immediately downstream of the SL. By calculating the number of nucleotides between the AUG and the 5' end or the 3' end of RPFs (Supplementary Methods), we identified a constant offset for P-sites from the 5' end of RPFs as −13, −12, −12, and −12 nt for L. polyedra, C. elegans, C. brennei, and C. remanei, respectively, independent of the RPF length (Fig. 2a). This could be explained by a consistent placement of the AUG within the ribosome and a consistent trimming at the 5' end of RPFs, leaving the same partial SL sequence. The single nucleotide difference in the 5' offset of L. polyedra and nematodes could be due to in RPF preparation processes, such as the different RNases used for digestion[5−7]. In contrast to the 5' end, offsets from the 3' end increase in concert with the size of RPFs (Fig. 2a), a pattern suggesting a differing efficiency of digestion at the 3' end. To assess the accuracy of the offsets, we mapped the RPFs onto the well annotated ORFs in reference genomes of C. elegans, C. brennei, and C. remanei, and calculated the offsets between the annotated AUG to the 5' end of RPFs (Fig. 2b). These offsets were again identified as −12 nt for nematodes (Fig. 2b), confirming that the AUG in our SL-RPFs correspond to authentic start codons. A total of 73.6%, 68.9%, and 81.6% of the SL-RPFs were mapped to annotated start codons in the genomes of C. elegans, C. brennei, and C. remanei, respectively, with those not mapped to annotated start codons possibly resulting from incorrect annotations or use of alternative translation initiation sites. We also attempted a similar analysis using the SL-RPFs of L. polyedra. As there is no annotated reference genome, we identified potential start codons as the most upstream AUG in the transcriptome assemblies[8] for 6,628 sequences whose reading frames were defined by proteomic analyses[9]. However, this did not show a clear offset from the potential start codon to the 5' end of RPFs (Fig. 2b), possibly due to incomplete or mis-assembled transcripts or proteins.

Figure 2.

SL provides Kozak consensus for the selection of start codons in dinoflagellates and nematodes. (a) Offsets from P-site to the 5' and 3' end of RPFs. All the RPFs were mapped to the genomes or transcriptome (L. polyedra) and the RPFs overlapped with the annotated start codons were used to count the offsets from their 5' and 3' ends to the annotated start codons (P-sites). (b) The mapping positions of RPFs on open reading frames display strong 3-nt periodicity, suggesting a high quality of these datasets. Frame 0 represents translating frames of genes and frame 1 and 2 represent the frames shifted 1 or 2 nt. The X-axis show the position of RPFs on the open reading frames, where position 0 represents the position of start codons. (c) The usage of start codons in different species. (d) Distance from SL to start codon in RPFs and RNA-seq reads. (e) Kozak consensus of different start codons identified from SL-RPFs. (f) Examples of SL-RPFs in dinoflagellates and nematodes. The start codon is colored in purple and the SL sequence is colored in orange.

The SL-containing RPF sequences also suggested the use of alternative start codons. We extracted all codons found at the experimentally determined offsets (−13 for dinoflagellate, and −12 for nematodes in this study) within SL-containing RPF sequences, reasoning that these would function as start codons if these SL-RPFs represent footprints at initiation sites (Supplementary Methods). AUG is the most predominant codon found at the offset position for all species, but a wide variety of other codons are also found (Fig. 2c). GUG has the second-largest usage in dinoflagellates, while UUG is the second-largest in nematodes.

To explore the roles of SL in translation initiation, we inspected the spacing between the end of the SL to the nearest AUG codon. The SL is preferentially added at an AUG (a peak at 0 nucleotides) in dinoflagellate SL-RPFs. However, the SL of nematodes tends to be added just upstream from the start codon in the RPFs (Fig. 2d), with a peak at 1 nt in all species tested. Interestingly, two peaks (1 nt and 5 nt) of a gap between the SL and the AUG in SL-RPFs were observed using SL-containing RNA-Seq reads instead of RPFs for C. brenneri and C. remanei (Fig. 2d). The peak at 5 nt essentially disappeared in SL-containing RPFs, suggesting this spacing may not be favored by the translation initiation machinery. In the dinoflagellate L. polyedra, we note a discrepancy between RNA-seq reads and RPFs, which suggests there may be a second group of transcripts containing initiation sites further downstream from the trans-splicing site.

The nucleotide context surrounding the codons at the offset position was also extracted from SL-RPFs for each type of the predicted start codons (Fig. 2e). As shown by the sequence logos, predicted AUG start codons in all species have a context that is G-rich at the +4 position and A/G-rich at the −3 position, as expected for a typical Kozak consensus context[10]. The dinoflagellate SL sequence can be unambiguously identified in the sequence logo upstream from the AUG (Fig. 2e), meaning the nucleotide at the −3 position is defined by the dinoflagellate SL sequence (5'-WCCGUAGCCAUUUUGGCUCAAG-3'). As there are three A/G nucleotides at the 3' end of dinoflagellate and nematode SL sequences, a good Kozak context could be provided for downstream start codons within three nucleotides. Indeed, AUG further than 3 nt from SL was rarely seen in dinoflagellates SL-RPF (Fig. 2d, f). Nematode SL-RPFs had AUG further than 3 nt (within 5 nt) because nematode SL was usually followed by 'GG', which was identified as a part of SL in some studies[4], providing another two nucleotides for Kozak background. Interestingly, we found the second most frequently used start codon in nematodes, UUG, was from the SL sequence itself (Fig. 2e & f), suggesting that in these cases the SL may supply the start codon.

Overall, our results reveal different potential roles of SL in translation initiation in different lineages. Both dinoflagellate and nematode SL can help provide a good Kozak context, thus promoting the selection of a nearby AUG codon for translation initiation, while euglenozoa probably cannot because its 3' end had fewer A/G. Nematode SL can also supply a potential start codon, UUG, which may result in the translation of alternative reading frames. The function of SLs in different species seems to strongly rely on their sequences. Given that the SLs in rotifera, cnidaria, and chordata are also rich in A/G at their 3' end[4], they may also work as a Kozak consensus supplier, similar to the roles revealed in this study. More investigation will be required to understand the roles of SL addition across different species and the addition of SLs should be considered in the annotation of ORFs in these species[11].

HTML

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31601042 to B.S.) and by the National Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (No. 171382 to D.M.).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Song B, Morse D; data colletion and analysis: Ye Z, Song B; data visualization: Wu Z; draft manuscript preparation and revision: Ye Z, Song B, Morse D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The reads of RNA-seq and Ribo-seq used in this study were collected from previously published literature. These datasets are publicly available on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra), and the accession entries for RNA-seq and Ribo-seq data of different species are as follows: L. polyedra (SRR330443, SRR13386980), C. elegans (SRR914328, SRR914328), C. brenneri (SRR914367, SRR914373), C. remanei (SRR914355, SRR914361), and T. brucei (SRR1272139, SRR1272130). For more details, please refer to Supplementary Table S1.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplemental Table S1 The data sources of RNA-seq and Ribo-seq reads used in this work.

- Supplemental Table S2 The number of SL-RPFs in each organism.

- Supplementary Methods Supplementary methods used in this study.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Ye Z, Wu Z, Morse D, Song B. 2025. Ribosome footprinting reveals potential roles for spliced leader sequences in translation initiation. Genomics Communications 2: e008 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0008 |