-

Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum × morifolium Ramat. ex Hemsl.) is a globally renowned ornamental plant, celebrated not only for its exceptional esthetic appeal and profound cultural significance but also for its rich content of nutrients and bioactive compounds[1]. These characteristics have led to its extensive applications in various fields, including medicine, food, and beverages[2]. In recent years, with the growing demand for high-value plant-based products[3], research on the genetic resource innovation and breeding of chrysanthemum has gained considerable attention. However, the evolutionary history of the Asteraceae family, to which chrysanthemum belongs, is highly complex[4]. Within this family, the genus Chrysanthemum is particularly challenging because of its intricate intraspecific relationships. This complexity arises from the remarkable species diversity within the genus and its capacity to adapt to various ecological environments, which reflects a multi-dimensional and multi-layered evolutionary history[5]. These taxonomic and phylogenetic ambiguities significantly impede the effective utilization and commercialization of the genetic resources[6].

Traditionally, the classification of Chrysanthemum species has relied on morphological traits[7]. Although this approach has provided insights into basic interspecies relationships, it has several limitations[8]. First, morphological traits are often influenced by environmental factors[9], leading to inconsistent classification results. Second, morphological taxonomy is subjective, labor-intensive, and less efficient, making it inadequate for the precision and efficiency demanded by modern botanical studies[10]. These issues are particularly pronounced in the study of cultivated chrysanthemum and its closely related species. As a product of extensive hybridization, chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum × morifolium Ramat. ex Hemsl.) exhibits a complex genetic background[11], making it difficult to classify accurately on the basis of morphological characteristics alone. Therefore, to better understand the phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of Chrysanthemum species, it is imperative to adopt more scientific, systematic, and precise methodologies.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized plant phylogenetics, particularly through chloroplast genome studies, by offering significantly enhanced resolution for reconstructing plant taxonomy and evolutionary relationships[12,13]. This advancement has been particularly impactful for deciphering the history of taxonomically complex and economically important genera like Chrysanthemum. Given this evolutionary complexity and the resulting taxonomic challenges, certain chloroplast molecular markers have shown strong discriminatory power at the species level, with comparative plastome analyses revealing lineage-specific variations that illuminate phylogenetic relationships and resolve taxonomic ambiguities[14]. Indeed, such studies have clarified the phylogeny of the tribe Anthemideae[15], established that Chrysanthemum itself is not monophyletic and should be circumscribed to include the genus Ajania[9], and identified the core mechanisms propelling its diversification. These include frequent whole-genome duplications (WGDs), complex polyploidization events, extensive gene flow[16,17], and geographic isolation[18]. In summary, evolutionary research on Chrysanthemum, leveraging both chloroplast and nuclear genomic tools, has consistently highlighted the promotional roles of WGDs, geographic isolation, and hybridization in driving diversification[19]. These evolutionary insights have converged on the complex origin of cultivated chrysanthemum. Integrated analyses of chloroplast genomes and nuclear genes, such as LFY, suggest that cultivated chrysanthemum arose from a complex hybridization-driven domestication process. Specifically, while cultivated C. × morifolium shares high structural similarity with wild relatives, it also harbors specific variants likely shaped by artificial selection[20]. The collective evidence indicates a maternal origin from an extinct wild lineage, with paternal contributions from multiple extant species such as C. indicum and C. zawadskii[14,20]. However, despite this progress, the parental origin of cultivated chrysanthemum has not yet been fully revealed, as the precise identity of this maternal progenitor remains speculative due to incomplete sampling of wild populations and its presumed extinction.

In this study, we assembled the complete chloroplast genomes of nine Chrysanthemum accessions de novo and performed comprehensive phylogenomic analyses to elucidate interspecific relationships and evolutionary patterns within the genus. By leveraging the structural conservation and phylogenetic informativeness of chloroplast genomes, our research aimed to provide new insights into the origin, evolution, and taxonomy of Chrysanthemum, thereby contributing to the development of genomic-assisted breeding and the sustainable use of its genetic resources.

-

Chrysanthemum species are widely distributed across diverse geographical regions and exhibit significant ecological adaptability. In this study, nine accessions representing four species preserved in the Chrysanthemum Germplasm Resource Preserving Centre (Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) were selected, including six wild accessions of C. indicum from different geographical regions (Henan, Hubei, Nanjing, Shennongjia, Wuyishan, and Yuntaishan), and C. dichrum, C. potentilloides and C. rhombifolium.

Chloroplast genome assembly and annotation

-

Chloroplast genome sequences were deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the accession numbers SRR17853973 (C. dichrum), SRR17853975 (C. potentilloides), SRR17853978 (C. rhombifolium), SRR17853981 (Henan population of C. indicum), SRR17853979 (Hubei population of C. indicum), SRR17853977 (Nanjing population of C. indicum), SRR17853976 (Shennongjia population of C. indicum), SRR17853974 (Wuyishan population of C. indicum), and SRR17853972 (Yuntaishan population of C. indicum). Additional details for these accessions are provided in Supplementary Table S1. The raw sequencing data were assembled using GetOrganelle software[21]. The published chloroplast genome of C. × morifolium (NCBI accession: MH165289.1) was used as a reference for collinearity analysis with MUMmer[22]. On the basis of the alignment results, chloroplast genome sequences were corrected using CPStools[23] to ensure structural consistency for subsequent analyses. The corrected genomes were then annotated using CPGAVAS2[24], with the published chloroplast genome of C. indicum (syn. C. nankingense, NCBI accession: MT919682.1) as the reference.

Comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes

-

GenBank files generated by CPGAVAS2 were submitted to Geseq[25] to produce chloroplast genome maps. Overall sequence variation among the chloroplast genomes was analyzed using mVISTA[26]. The boundaries between inverted repeat (IR) regions and single-copy (SC) regions were compared using CPJSdraw[27]. Repetitive sequences, including forward, reverse, complement, and palindromic repeats, were identified using the REPuter online tool[28]. Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were detected using MISA-web[29]. The distribution and characteristics of repetitive sequences were visualized using ggplot2[30].

Phylogenetic analysis

-

Phylogenetic relationships were reconstructed on the basis of 42 complete chloroplast genomes, comprising 32 previously published Chrysanthemum genomes (Supplementary Table S2) and nine genomes newly assembled in this study. A total of 74 protein-coding genes (CDS) were extracted for phylogenetic inference, with Artemisia annua designated as the outgroup. Detailed species information and GenBank accession numbers are listed in Supplementary Table S2. The K3Pu + F + I substitution model was selected as the best fit for the data by ModelFinder[31] and used for all subsequent phylogenetic analyses. Maximum likelihood (ML) analysis was conducted in IQ-TREE v2.0.3[32] with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Bayesian inference (BI) was carried out using MrBayes v3.2.7a[33] on the CIPRES Science Gateway platform[34]. For the BI, Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms were run for 2 million generations and sampled every 1,000 generations. The stationary phase was considered to have been reached when the average standard deviation of split frequencies fell below 0.01. The phylogenetic tree was visualized with Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6[35].

-

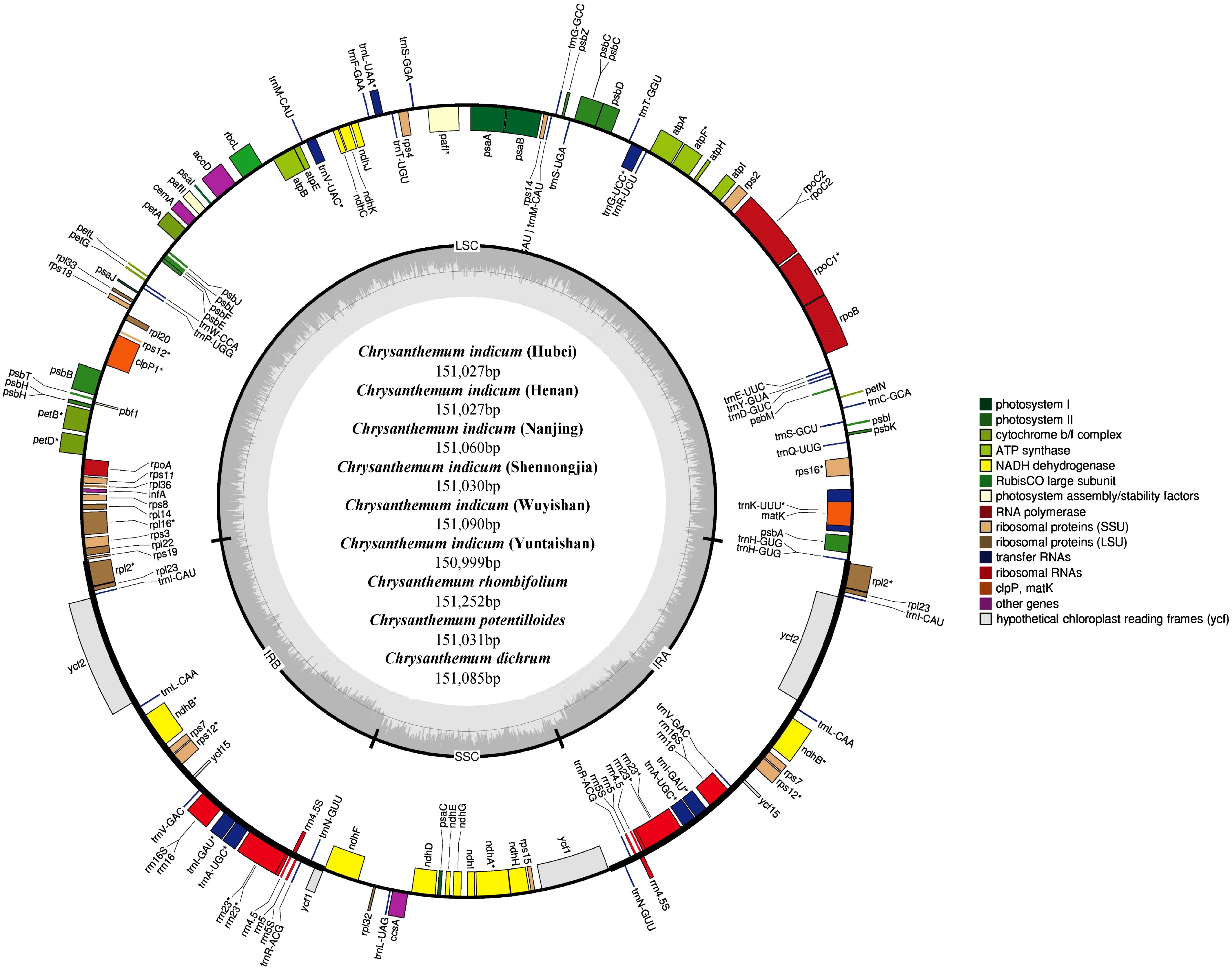

In this study, we successfully conducted de novo assembly of the complete chloroplast genomes for nine Chrysanthemum accessions, including C. dichrum, C. indicum (Henan), C. indicum (Hubei), C. indicum (Nanjing), C. indicum (Shennongjia), C. indicum (Wuyishan), C. indicum (Yuntaishan), C. potentilloides, and C. rhombifolium (Fig. 1). All genomes exhibited the typical quadripartite circular structure characteristic of most angiosperm chloroplasts, comprising a large single-copy (LSC) region, a small single-copy (SSC), and two inverted repeats (IRa and IRb). This conserved structural organization reflects a high degree of evolutionary conservation across the Asteraceae family.

Figure 1.

The genome map of nine Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes. Genes outside the circle were transcribed clockwise and those inside were transcribed counter-clockwise. Different gene functions are represented by different colors.

The total genome sizes ranged from 150,999 to 151,252 bp, indicating striking uniformity among the nine species. Each chloroplast genome encodes 128 unique genes, including 85 CDS, 35 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes, and 8 ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, underscoring the functional integrity of the assembled genomes. The GC content exhibited minimal variation, ranging from 37.45% to 37.46% (Table 1), further supporting the genomic conservation across species. The gene content and architecture were highly conserved across all nine Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes, a stability likely maintained by strong purifying selection on essential genes for photosynthesis and self-replication (Table 2)[36,37]. This conserved genomic framework not only underscores the evolutionary cohesion within the genus but also provides a valuable resource for future functional and comparative studies.

Table 1. Comparison of the chloroplast genome's characteristics in nine Chrysanthemum accessions.

Species Geographical region Total chloroplast DNA size (bp) Intergenic GC (%) Number of genes CDS tRNAS rRNAS Chrysanthemum indicum Hubei 151,027 37.47 128 85 35 8 Chrysanthemum indicum Henan 151,027 37.47 128 85 35 8 Chrysanthemum indicum Nanjing 151,060 37.45 128 85 35 8 Chrysanthemum indicum Shennongjia 151,030 37.48 128 85 35 8 Chrysanthemum indicum Wuyishan 151,090 37.46 128 85 35 8 Chrysanthemum indicum Yuntaishan 150,999 37.48 128 85 35 8 Chrysanthemum rhombifolium Chongqing 151,252 37.45 128 85 35 8 Chrysanthemum potentilloides Shaanxi 151,031 37.48 128 85 35 8 Chrysanthemum dichrum Hebei 151,085 37.47 128 85 35 8 Table 2. Gene composition in nine Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes.

Category of genes Group of genes Name of genes Genes for photosynthesis Subunits of ATP synthase atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF, atpH, atpI Subunits of Photosystem II psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ Subunits of (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) NADH-dehydrogenase ndhA, ndhB(2), ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK Subunits of cytochrome b/f complex petA, petB, petD, petG, petL, petN Subunits of Photosystem I psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ Subunit of Rubisco rbcL Self replication Large subunit of ribosome rpl14, rpl16, rpl2(2), rpl20, rpl22, rpl23(2), rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 DNA-dependent RNA polymerase rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1, rpoC2 Small subunit of ribosome rps11, rps12(2), rps14, rps15, rps16, rps18, rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7(2), rps8 Other genes Subunit of acetyl-Coenzyme A (CoA)-carboxylase accD C-type cytochrome synthesis gene ccsA Envelope membrane protein cemA Protease clpP Translational initiation factor infA Maturase matK Genes with unknown functions Conserved open reading frames ycf1, ycf15(2), ycf2(2), ycf4, ycf3 Variation analysis of Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes

-

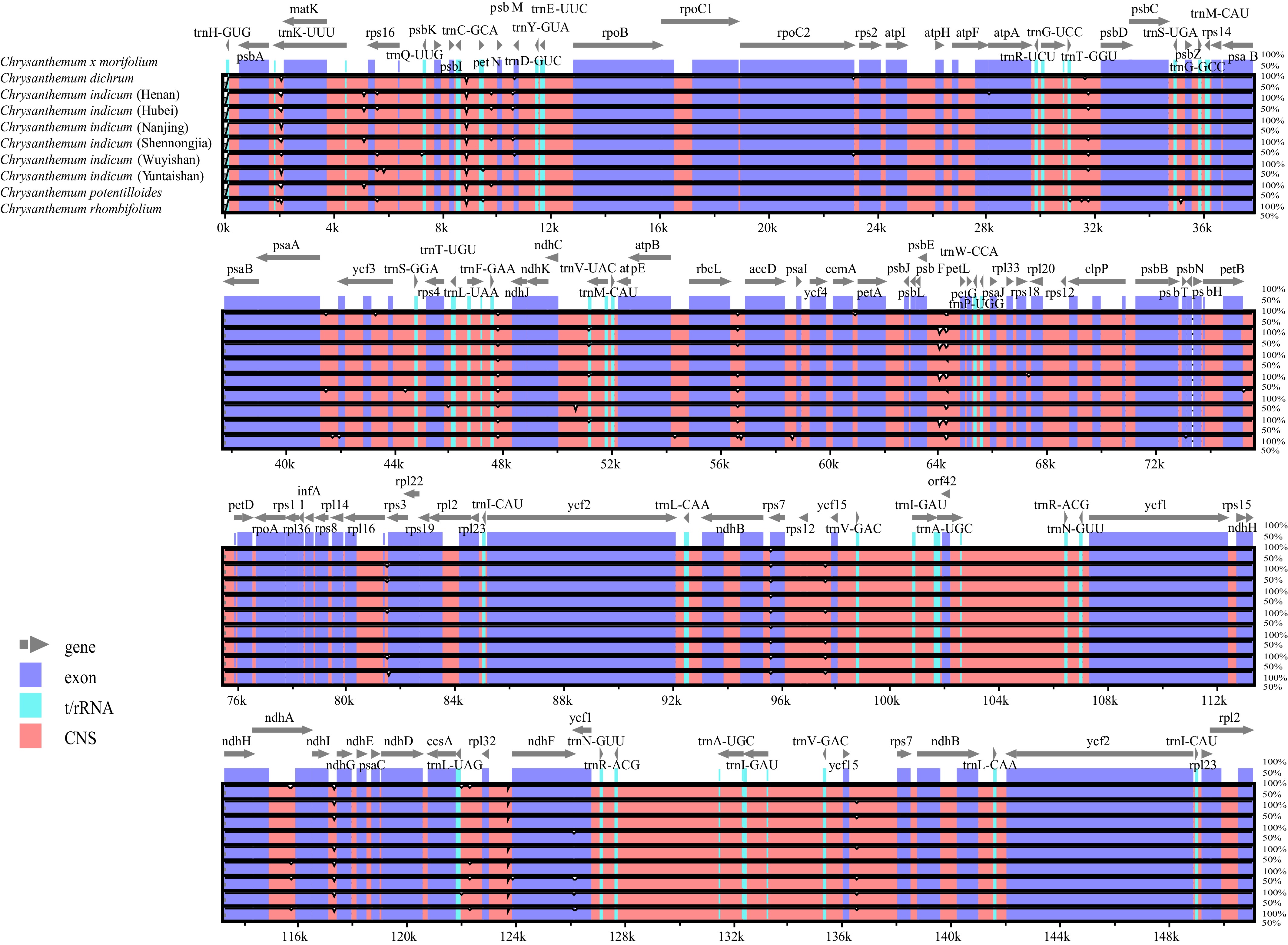

Comparative analysis using mVISTA revealed high collinearity across the nine Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes, though specific hotspots of divergence were identified, particularly in the single-copy regions (Fig. 2). As expected, sequence divergence was significantly higher in the large and small single-copy (LSC/SSC) regions than in the highly conserved IR regions. This well-documented pattern is attributed to the homogenizing effects of concerted evolution within the IRs, which resists the accumulation of mutations [14,38]. Similarly, noncoding regions (intergenic spacers and introns) exhibited substantially more variation than protein-coding regions.

Figure 2.

Comparison of nine Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes using the mVISTA program. Exons are presented in purple, t/rRNA is presented in blue, conserved non-coding sequences (CNS) are presented in pink.

This is likely due to relaxed selective constraints in noncoding DNA, which would allow neutral or nearly neutral mutations to persist over evolutionary timescales[39]. These subtle variations may contribute to our understanding of the evolutionary dynamics within the genus and provide useful molecular markers for phylogenetic and population genetic analyses within Chrysanthemum.

Boundary analysis of Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes

-

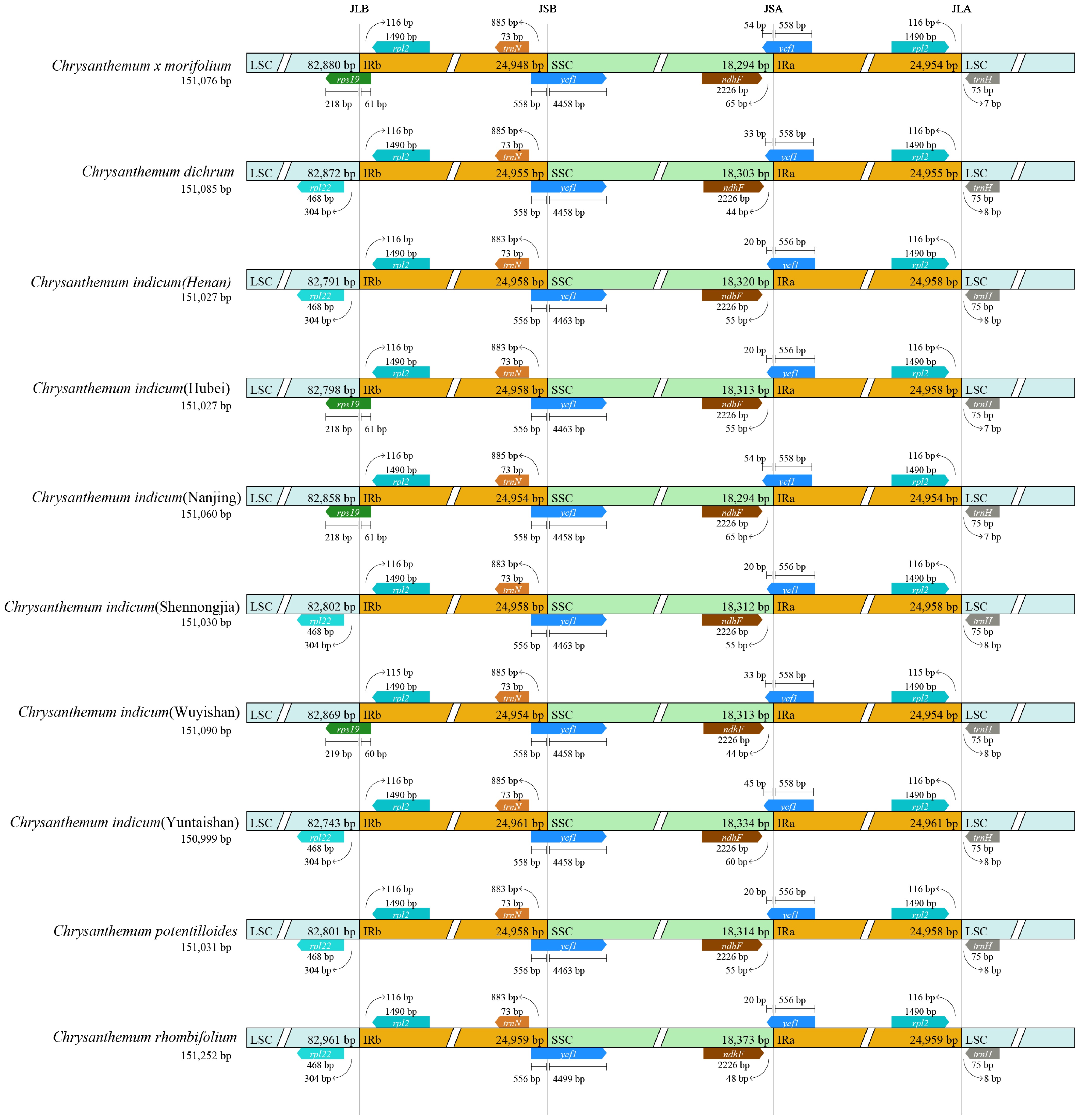

CPJSdraw was used to analyze the boundary regions of the chloroplast genomes, including the junctions between the LSC and IRa, between IRa and SSC, between SSC and IRb, and between IRb and LSC (Fig. 3). This comprehensive analysis provided detailed insights into the structural organization of the chloroplast genomes across the nine Chrysanthemum accessions.

Figure 3.

The boundaries for comparing the inverted repeat (IR) and single copy (SC) regions among the chloroplast genomes of nine Chrysanthemum populations.

The overall genomic structure was highly conserved across the analyzed Chrysanthemum species, with only minor variations detected at the IR–SC boundary regions. Notably, the three C. indicum populations (Hubei, Nanjing, and Wuyishan) showed the highest structural identity to the C. × morifolium reference genome. This pronounced structural conservation suggests significant evolutionary stability, likely reflecting a low frequency of large-scale genomic rearrangements within the genus.

Repeat sequence analysis of Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes

-

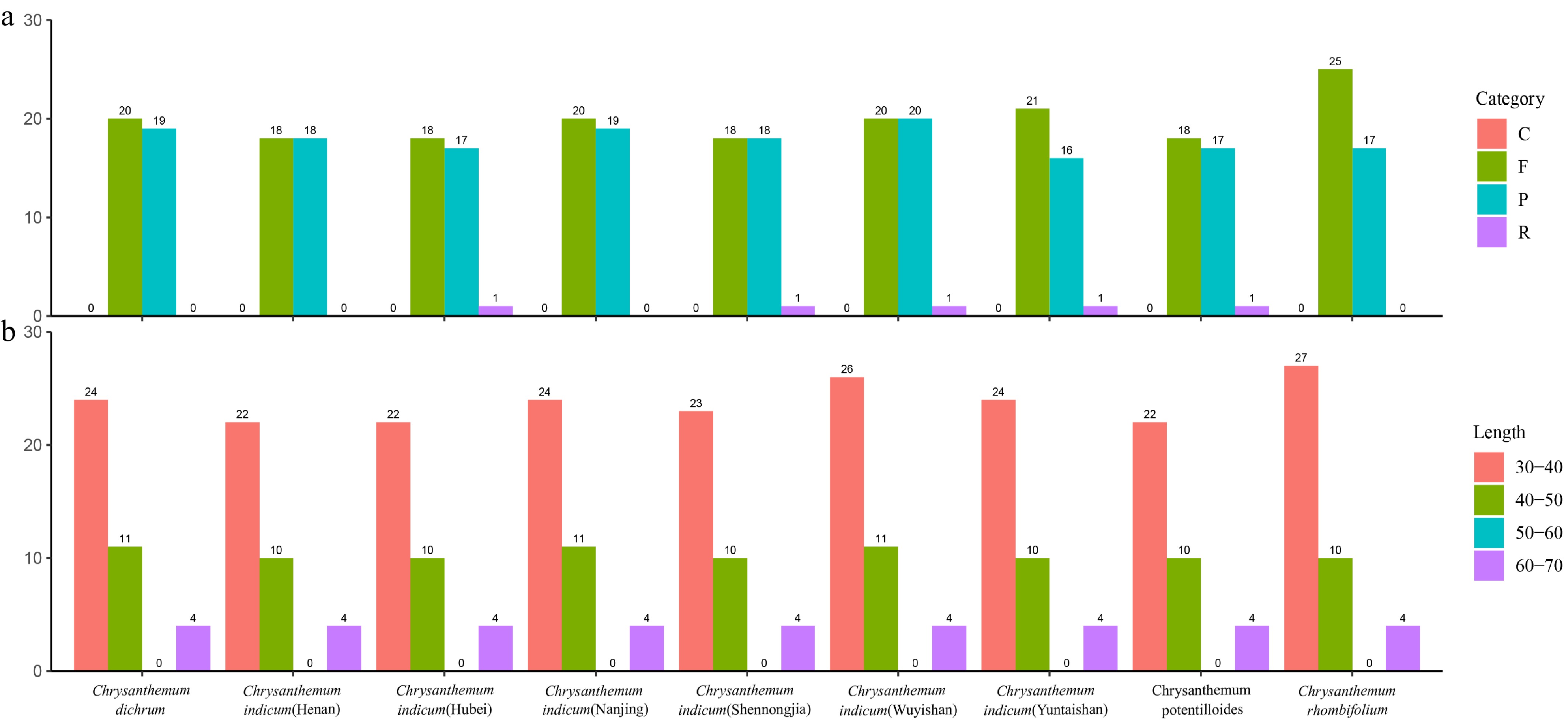

Analysis of the nine Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes identified 344 long repeats, comprising 178 forward, 161 palindromic, and 5 reverse types. While no complementary repeats were detected, the five reverse repeats were taxon-specific, with one each found in of C. potentilloides and four distinct populations of C. indicum (Henan, Shennongjia, Wuyishan, and Yuntaishan) (Fig. 4a). This distribution pattern is consistent with previous studies in Chrysanthemum[40,41], suggesting that the composition and distribution of repetitive elements in chloroplast genomes are subject to conserved evolutionary constraints. The majority of long repeats ranged from 30 to 40 base pairs in length (Fig. 4b), indicating a consistent length distribution pattern across the species. These repeat sequences may facilitate genome rearrangements and promote genetic diversity, consistent with previous findings on plants' plastome evolution[42].

Figure 4.

Long repeat sequence analysis. (a) Palindromic repeats are presented in pink, forward repeats in green, reverse repeats in blue, and complement repeats in purple. (b) Repeats with a base length of 30–40 bp are presented in pink, repeats with a base length of 40–50 bp in green, repeats with a base length of 50–60 bp in blue, and repeats with a base length of 60–70 bp in purple.

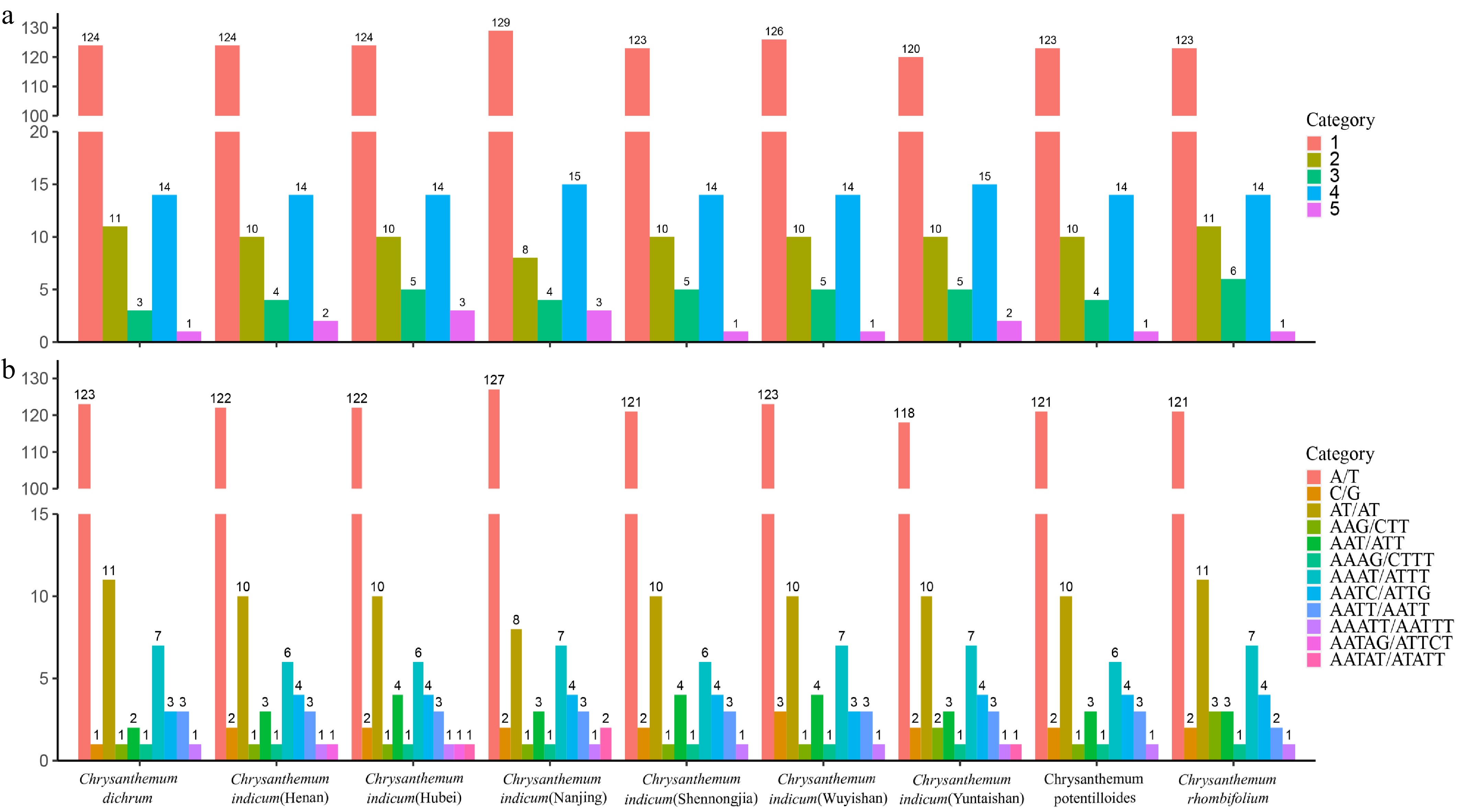

Analysis of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) revealed a predominance of A/T-rich mononucleotide repeats, which constituted 76.8% of all identified SSRs and far outnumbered the other repeat types (Fig. 5a). This A/T bias is a characteristic feature of angiosperm chloroplast genomes[6,43]. Higher-order repeats (di-, tri-, tetra-, and pentanucleotides) were also overwhelmingly composed of A/T motifs (e.g., AT/AT, AAT/ATT) (Fig. 5b). The prevalence of these A/T-rich repetitive sequences is thought to contribute to genomic plasticity and stability, with their specific motifs and distribution patterns likely reflecting evolutionary pressures that shaped the Chrysanthemum genome for adaptation and divergence[42−45].

Figure 5.

Simple sequence repeat (SSR) analysis. (a) Number of different SSR types detected in the chloroplast genomes of nine Chrysanthemum genera. (b) Frequency of identified SSR motifs in the chloroplast genomes of nine Chrysanthemum genera.

Despite the high degree of sequence conservation observed in Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes, variations in repetitive sequences, GC content, and boundary regions provide valuable genetic resources for practical applications. These variations can serve as reliable molecular markers for species identification, cultivar discrimination, and phylogenetic studies, offering tools for unraveling genetic relationships within the genus[14,40]. Furthermore, systematic characterization of the repetitive elements establishes baseline genomic parameters for comparative analyses and provides a foundation for future studies on the chloroplast genome's evolution and functional genomics in Chrysanthemum.

Phylogenetic analysis of Chrysanthemum chloroplast genomes

-

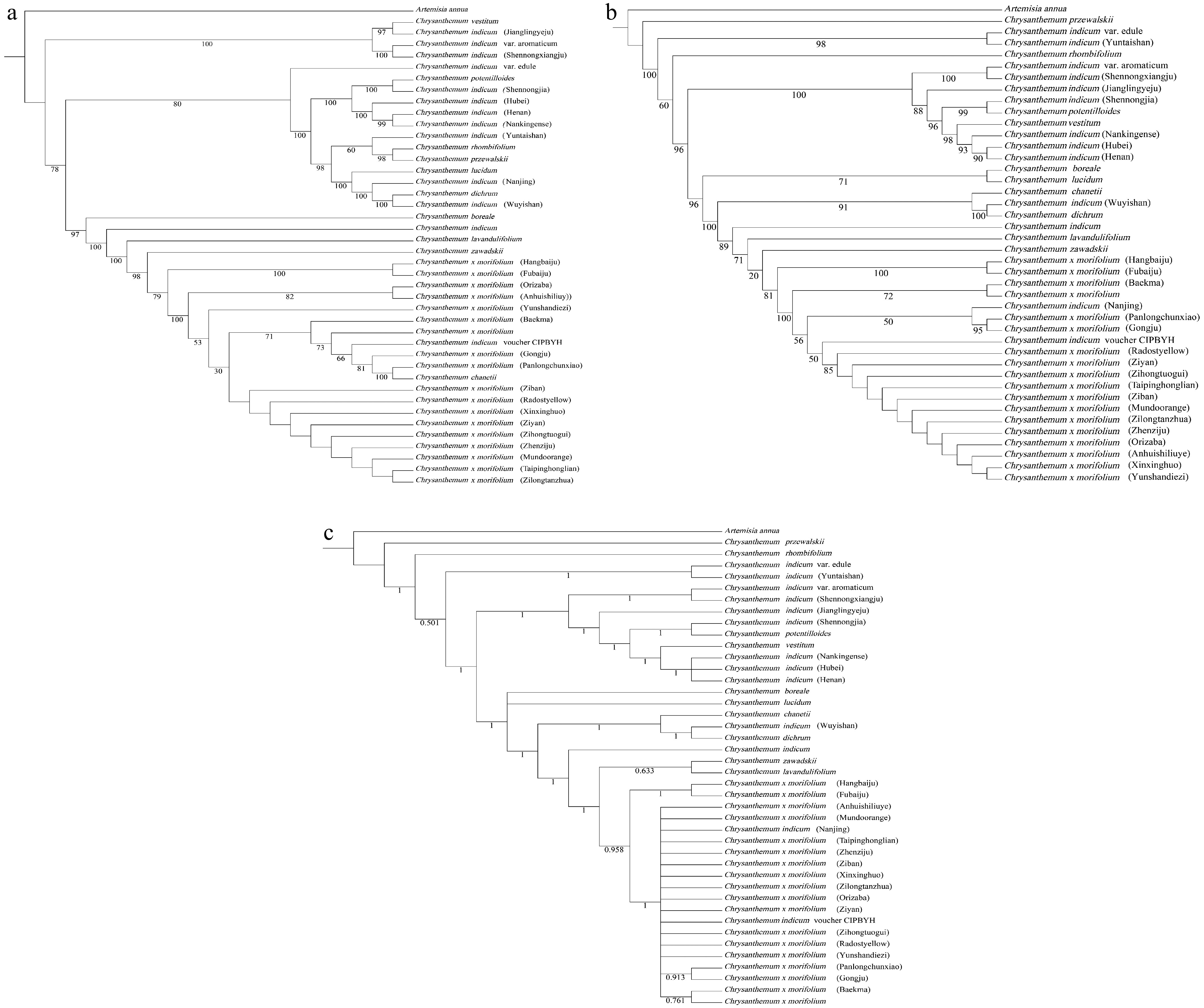

The phylogenetic tree constructed in this study (Fig. 6) provides a clear overview of the evolutionary relationships among the nine Chrysanthemum accessions, revealing distinct clades that broadly correspond to their geographical distributions and morphological characteristics. These patterns highlight the close association between phylogenetic groupings and the ecological or biological traits of Chrysanthemum species. Our results show that all individuals of C. × morifolium clustered together, suggesting that chloroplast genome-based phylogenetic analysis may have limited resolution for distinguishing among cultivated varieties. This finding is in accordance with the previous studies[20] and reflects the reduced genetic diversity of chloroplast genomes within domesticated lines, likely due to shared maternal origins.

Figure 6.

The phylogenetic tree was constructed using maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods, and was based on the complete chloroplast genome and chloroplast CDS of 41 Chrysanthemum species. Artemisia annua was used as the outgroup for the analysis. (a) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Chrysanthemum plants using complete chloroplast genomes. (b) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Chrysanthemum plants using chloroplast CDS. (c) Bayesian inference phylogenetic tree of Chrysanthemum plants using chloroplast CDS.

Furthermore, the phylogenetic relationships inferred from both BI and ML analyses based on chloroplast CDS were highly consistent. Both approaches clearly resolved two major clades, separating cultivated chrysanthemums (Chrysanthemum × morifolium Ramat. ex Hemsl.) from its wild relatives (C. indicum and related species), as expected in light of the evolutionary history and domestication processes. Additionally, our phylogenetic tree based on complete chloroplast genome sequences revealed that C. indicum is most closely related to C. × morifolium, corroborating previous findings by Ma et al.[20]. Moreover, among all sampled C. indicum populations, the accession from Nanjing exhibited the closest genetic relationship to C. × morifolium, suggesting a potential role of C. indicum (Nanjing) in the domestication or hybrid origin of cultivated chrysanthemums. Interestingly, our results differ from those of Song et al.[2], who reported a closer relationship between C. rhombifolium and C. × morifolium on the basis of nuclear gene data. In contrast, our chloroplast genome analysis indicated a more distant relationship between C. rhombifolium and C. × morifolium, when compared with other species. Given the maternal inheritance pattern of chloroplasts, this discrepancy suggests that C. rhombifolium may have contributed to the paternal lineage of cultivated chrysanthemums, providing indirect evidence for its role in the hybrid origin of domesticated varieties. Additionally, phylogenetic analysis of Chrysanthemum species closely related to cultivated chrysanthemum using maximum likelihood (ML) and based on complete chloroplast genomes revealed a strongly supported clade (bootstrap [BS] > 98%) comprising C. zawadskii, C. lavandulifolium, and C. × morifolium (Fig. 6a). Concordantly, both ML and Bayesian inference (BI) phylogenies from chloroplast CDS data recovered this monophyletic clade (Fig. 6b, c), confirming its robustness. This clade was also replicated in the BI phylogeny of Xu et al.[14] using complete chloroplast genomes, supporting closer evolutionary relationships among these species, which supports the hypothesis that C. zawadskii played a significant role in the evolutionary history and diversification of C. × morifolium, consistent with its proposed status as one of the ancestral contributors to the cultivated gene pool. The complete chloroplast genome phylogeny further indicates that C. chanetii clusters within the C. × morifolium clade, suggesting its possible contribution to the origin of C. × morifolium, consistent with previous studies[14,20].

Additionally, the interpretation of our phylogenetic findings is fundamentally constrained by the genetic system under investigation. In most angiosperms, the chloroplast genome is strictly maternally inherited[46]. Consequently, the phylogeny presented here exclusively reconstructs the maternal lineage and evolutionary history of cultivated chrysanthemum and its wild relatives. The cultivated chrysanthemum is understood to have originated from complex hybridization events[11], which necessarily involve paternal genetic contributions. Although they are good enough for tracing maternal ancestry, our chloroplast-based analysis cannot resolve the paternal lineages within this intricate hybridization network. Therefore, while our results strongly implicate the C. indicum population from Nanjing as a key maternal progenitor, this finding illuminates only the maternal facet of the chrysanthemum's complex ancestry. To fully elucidate the reticulate evolutionary history of C. × morifolium, future investigations must incorporate biparentally inherited nuclear markers[47]. Analyses employing whole-genome will be instrumental in identifying paternal progenitors and, ultimately, in reconstructing the comprehensive evolutionary network that gave rise to this vital ornamental crop.

Among the Chrysanthemum varieties used for tea or medicinal purposes, the closest genetic relationship was observed between C. × morifolium (Fubaiju) and C. × morifolium (Hangbaiju), reflecting their strong genetic similarity and shared evolutionary history. This finding aligns with previous research by Yao et al.[48] and supports the traditional classification of these varieties based on morphological and medicinal characteristics. Overall, these phylogenetic insights provide valuable insights into the evolutionary history, genetic relationships, and domestication processes within the Chrysanthemum genus. Furthermore, the results offer valuable information for guidance for future studies on species differentiation, genetic diversity, and targeted breeding strategies.

-

In this study, we successfully assembled the complete chloroplast genomes of nine Chrysanthemum accessions and performed a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis by integrating newly generated and published chloroplast genome data from related taxa. The results revealed a high degree of structural conservation across the analyzed chloroplast genomes, underscoring their evolutionary stability and providing reliable references for species delimitation and phylogenetic inference. Phylogenetic reconstruction demonstrated a close evolutionary relationship between C. indicum and C. × morifolium, consistent with previous reports. Notably, the C. indicum population from the Nanjing showed a stronger phylogenetic affinity to C. × morifolium than to conspecific populations from other geographic regions, suggesting a possible contribution of C. indicum (Nanjing) to the ancestral gene pool of cultivated chrysanthemums. This observation offers preliminary evidence for the involvement of geographically specific wild populations in the domestication and origin of C. × morifolium, which merits further investigation using additional nuclear and genomic data. The comparative chloroplast genomic framework established in this study provides valuable resources for exploring the evolutionary dynamics, species relationships, and functional genomics within the Chrysanthemum genus. These findings lay a foundation for future studies on species evolution, molecular marker development, and breeding strategies aimed at improving ornamental, medicinal, and agronomic traits in chrysanthemums.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32522095, 32172609), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (YDEX2025038), the Traditional Chinese Medicine Interdisciplinary Cultivation Project, the 'Blue Project' of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, and a project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Song A, Dong Y, Wang Z, Chen S, Chen F; data collection: Dong Y; analysis and interpretation of results: Dong Y; draft manuscript preparation: Dong Y, Cao Q, Yu K. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. The SRA accession numbers for the whole-genome sequencing datasets of the nine studied Chrysanthemum genus accessions are documented in Supplementary Table S1. These raw data files (FASTQ format) can be retrieved from NCBI SRA using the provided accession codes under BioProject PRJNA796762. No special credentials or approvals are required for access.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 SRA accession numbers for samples used in de novo chloroplast genome assembly.

- Supplementary Table S2 GenBank accession numbers for materials analyzed in this study.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Dong Y, Cao Q, Yu K, Wang Z, Chen S, et al. 2025. Chloroplast phylogenomics reveals the maternal ancestry of cultivated chrysanthemums. Genomics Communications 2: e019 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0019

Chloroplast phylogenomics reveals the maternal ancestry of cultivated chrysanthemums

- Received: 15 July 2025

- Revised: 02 September 2025

- Accepted: 03 September 2025

- Published online: 25 September 2025

Abstract: Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum × morifolium Ramat. ex Hemsl.), a globally important ornamental plant originating from China, possesses significant economic and cultural value. However, its complex genetic background—shaped by extensive hybridization, polyploidization, and artificial selection—has obscured its parental origins. To elucidate its maternal lineage, we sequenced and assembled the complete chloroplast (cp) genomes of nine accessions de novo from four key Chrysanthemum species: C. dichrum, C. indicum (representing six distinct geographical populations), C. potentilloides, and C. rhombifolium. Comparative analysis revealed highly conserved quadripartite structures across all nine cp genomes, with sizes ranging from 150,999 to 151,252 bp and a GC content of approximately 37.46%. Crucially, phylogenetic analysis, incorporating data from 32 additional published Chrysanthemum cp genomes, revealed that all cultivated chrysanthemum accessions formed a single, monophyletic clade deeply nested within the genetic diversity of wild C. indicum. This finding strongly indicates that C. indicum is the primary maternal progenitor of the cultivated chrysanthemum. Collectively, this research clarifies the genetic diversity and complex evolutionary history of Chrysanthemum, providing a valuable genomic resource for future genetic conservation and breeding programs.

-

Key words:

- Chrysanthemum /

- Chloroplast genome /

- Structural analysis /

- Phylogenetic analysis