-

Cistanches Herba (commonly known as Roucongrong in Chinese) is a traditional medicinal herb with a long history of use in Chinese medicine. It is renowned for its functions in supplementing the kidney (yang), restoring essence and blood, and facilitating bowel movement to relieve constipation. Recognized as one of the 'Nine Main Chinese Herbs', it is also honored as 'desert ginseng' due to its significant health-promoting properties. Two species, Cistanche deserticola Y. C. Ma, and C. tubulosa (Schenk) Wight, are commonly used and authenticated in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia[1]. According to traditional Chinese medicine classics, the original botanical source of Cistanches Herba is primarily C. deserticola, which is recognized as the high-quality variety[2].

As a root-parasitic plant, the host specificity and selectivity of C. deserticola have long been a focus of research interest. Before 2017, Haloxylon ammodendron (C. A. Mey.) Bunge (Amaranthaceae) was the only confirmed host plant involved in studies on C. deserticola. In 2017, Atriplex canescens (Pursh) Nutt. (Amaranthaceae) was reported as a new host, also susceptible to parasitism by C. deserticola[3]. This discovery expanded the known host range of C. deserticola. Consequently, the distribution of C. deserticola has been extended from the desert margins in northwestern China to the North China Plain, including regions such as Beijing, Cangzhou (Hebei Province), and Weifang (Shandong Province). In 2024, root-parasitic plants were discovered on Salsola tragus L. within a H. ammodendron - C. deserticola cultivation base in Qiemo County, Xinjiang. Morphologically, the parasites exhibit characteristics consistent with those of the genus Cistanche. Although the sown seeds were collected from the base field, their identification as C. deserticola remains unconfirmed. Furthermore, the potential occurrence of other wild Cistanche species in the surrounding area has not been thoroughly investigated. Thus, the identity of these root parasites as C. deserticola needs confirmation through further study.

S. tragus is a C4 annual herb widely distributed across temperate grasslands and desert regions of Eurasia[4]. In China, its range includes Northeast, Northwest, North China, as well as Xizang, Shandong and Jiangsu[5]. Commonly referred to as 'tumbleweed', it is characterized by its tendency to break off at the base of the stem and separate from the roots upon maturity and drying, enabling wind-driven dispersal across the landscape. This species demonstrates exceptional tolerance to saline-alkali stress, drought, high temperatures, and aeolian sand abrasion[6]. In the United States, S. tragus is an invasive plant that disrupts native ecosystems and increases fire risks[7]. In China, S. tragus is an indigenous species that serves as fodder due to its high palatability to camels, sheep, and goats[8]. It also holds a recognized position in the pharmacopeias of traditional Chinese and Mongolian medicine, particularly for the treatment of hypertension and neurasthenia[9]. Meanwhile, S. tragus serves as a dominant species in artificial enclosure grasslands in semi-arid areas[10]. Given its broad ecological adaptability and widespread distribution, the discovery of Cistanche-like parasites on this resilient species carries considerable scientific and practical implications. If confirmed as C. deserticola, this host-parasite association could overcome current resource bottlenecks in industrial production and substantially expand the potential planting area for C. deserticola.

To verify the accuracy of the unexpected discovery, traditional morphological identification was first performed on the root parasites. C. tubulosa and C. sinensis can be readily distinguished from C. deserticola based on differences in vascular bundle arrangement. However, distinguishing between C. deserticola and C. salsa morphologically presents greater difficulty. According to the Flora of China[5], the bracts of C. deserticola are relatively long, being equal to, or slightly exceeding, the length of the corolla, while the calyx measures approximately half the length of the corolla. In contrast, C. salsa has shorter bracts, about half the length of the corolla, and a calyx that is roughly one-third the length of the corolla. Anatomical analysis of stem cross-sections revealed that both species share a similar tissue organization, consisting of an epidermis, cortex, vascular bundles, and pith. Their vascular bundles are fusiform and collateral, forming a wavy circular shape[11]. The main difference is that the vascular sheath is caudate in C. deserticola, but triangular or semi-circular in C. salsa[3].

DNA barcoding is a widely adopted molecular identification technique that utilizes short, standardized genomic regions to accurately distinguish species. Initially proposed for animal taxonomy in 2003[12], the method was subsequently adapted for use in medicinal plants in 2008[13]. Unlike traditional morphological identification, DNA barcoding relies on conserved genetic sequences that exhibit stability across developmental stages, tissue types, and environmental conditions[14]. Due to the low mutation rates and limited sequence divergence of the mitochondrial genome in plants, research on plant DNA barcoding has mainly focused on chloroplast and nuclear genomes[15]. Over the past two decades, several single-locus barcodes have been proposed, including ITS, ITS2, matK, rbcL, trnL intron, and psbA-trnH[16,17]. However, studies have demonstrated that no single barcode can reliably identify all plant species, necessitating the use of multi-locus combinations for robust discrimination[18−21]. Based on these findings, this study employed a combination of ITS2, rbcL, and trnL intron as barcode markers.

In addition to species identification, the quality assessment of active ingredients is essential. To investigate the impact of host plants on the medicinal quality of C. deserticola, we compared its phytochemical composition when parasitizing three different host species: S. tragus, A. canescens, and H. ammodendron.

-

Sample collection was conducted at two commercial Cistanche plantations: (1) Yuanhengqizheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. in Qiemo County (Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China), and (2) Huiqin Biotechnology Co., Ltd. in Jingtai County (Gansu Province, China). Qiemo County exhibits a warm temperate continental arid desert climate (mean annual precipitation: 18.6 mm)[22], while Jingtai County is characterized by a temperate continental arid climate (mean annual precipitation: 185 mm)[23]. Detailed collection information is provided in Table 1. Specimens used for morphological identification were immersed in FAA fixative. Those for molecular identification were stored at −20 °C in the Medicinal Plant Seed Laboratory, College of Agronomy, China Agricultural University. For component determination, Cistanche specimens were collected from the annual S. tragus's main roots. Multiple small specimens were combined to form one biological replicate, then frozen at −80 °C followed by freeze-drying. Sample diameter data are provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Table 1. Details of C. deserticola sample collection.

Collection number Host Collection time Collection location SC20240719-1 S. tragus 2024.7.19 Qiemo County, Xinjiang, China SC20240719-2 S. tragus 2024.7.19 Qiemo County, Xinjiang, China SC20240719-3 S. tragus 2024.7.19 Qiemo County, Xinjiang, China HC20240719 H. ammodendron 2024.7.19 Qiemo County, Xinjiang, China HC20241021 H. ammodendron 2024.10.21 Jingtai County, Gansu, China AC20241021 A. canescens 2024.10.21 Jingtai County, Gansu, China Tissue staining and observation of C. deserticola

-

The cross-sections of the samples were prepared using the semi-thin sectioning method[3]. The sections were stained with 1% safranine O at 40 °C for 1 h, and 0.5% fast green for 1 min. The slides were observed and imaged with a Motic K-400L stereoscope and an Olympus CX31RTSF microscope.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and gene sequencing

-

The genomic DNA of the samples was extracted using the FastPure Plant DNA Isolation Mini Kit (Nanjing Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd, Nanjing, China). The gene amplification primers and reaction conditions are shown in Table 2. Each gene in each specimen was repeated three times. The PCR products were sent to Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. for sequencing.

Table 2. Gene amplification primers and reaction conditions.

Gene name Primer sequence Reaction conditions ITS2 F: ATGCGATACTTGGTGTGAAT

R: GACGCTTCTCCAGACTACAATInitial denaturation: 95 °C 3 min;

Denaturation: 95 °C 15 s;

Annealing: 60 °C 15 s;

Extension: 72 °C 60 s;

Denaturation, annealing and extension were repeated for 35 cycles;

Final extension: 72 °C

5 minrbcL F: CCAAAGATACTGATATCTTGGCAGCAT

R: AGACATTCATAAACAGCTCTACCGTtrnL intron F: CGAAATCGGTAGACGCTACG

R: GGGGATAGAGGGACTTGAACDetermination of the concentration of medicinal ingredients

Preparation of reference substances and test substances

-

Standards were weighed and melted in 50% methanol to prepare mixed reference solutions of 0.8 mg/mL echinacoside, and 0.2 mg/mL acteoside. The freeze-dried samples were ground into powder (< 0.2 mm), then the powder was mixed into 50 mL 50% methanol in a 100 mL brown conical flask, and the test solutions were obtained after subjecting the mixture to shaking, soaking, sonication, standing, and filtration[1].

Liquid chromatography conditions

-

The chromatographic column was an Agilent ZORBAX SB-C18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm), with methanol (A) - 0.1% formic acid solution (B) as the mobile phase. Gradient elution: 0–17 min, 26.5% A; 17–20 min, 26.5%→29.5% A; 20–40 min, 29.5% A; flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, column temperature was 35 °C, detection wavelength was 330 nm, injection volume was 10 μL.

-

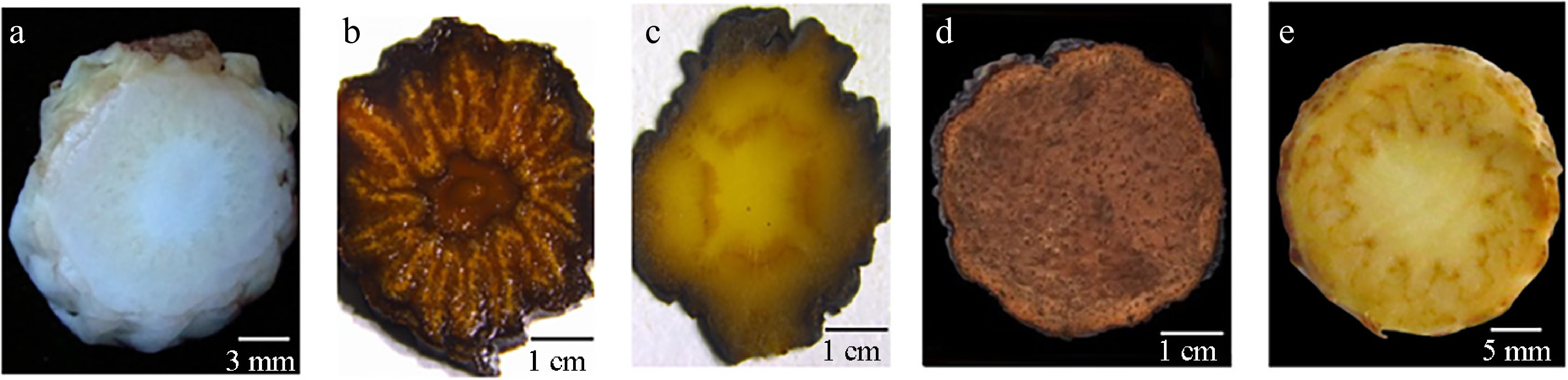

The root parasites on S. tragus were discovered within the sowing furrows of C. deserticola (Fig. 1a–c). These specimens exhibited characteristic morphological traits consistent with the genus Cistanche, including: (1) a pronounced fleshy main stem with numerous lateral branches emerging proximal to the parasitic attachment site; and (2) densely arranged broad-ovate scale leaves toward the stem base, transitioning to sparse lanceolate phyllotaxy in upper regions (Fig. 1d). To clarify the specific Cistanche species parasitizing S. tragus, comparative analysis of stem cross-sections were performed (Fig. 2). While the arrangement of the vascular bundle readily distinguished C. tubulosa and C. sinensis from C. deserticola, it was remarkably similar between C. deserticola and C. salsa, with both species exhibiting a wavy, curved, and circular pattern.

Figure 1.

Root parasites on S. tragus. (a) S. tragus growing in the C. deserticola sowing furrows. (b), (c) S. tragus - root parasite complex. (d) Enlarged view of the root parasite on S. tragus.

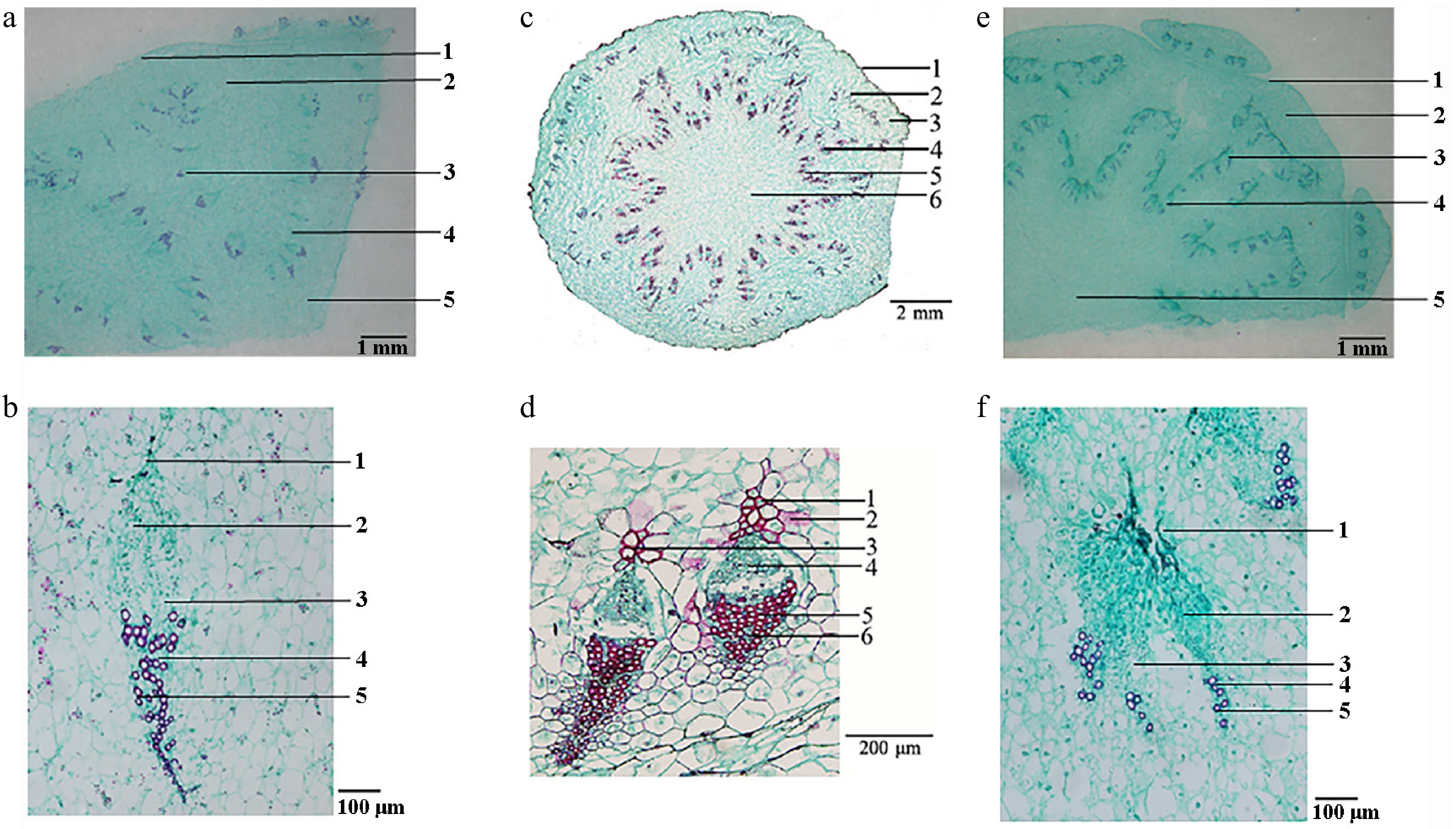

Semi-thin sections revealed that both species possessed similar stem anatomy, comprising epidermis, cortex, fusiform collateral vascular bundles, and a distinct pith (Fig. 3). The most reliable distinguishing characteristic was the morphology of the vascular sheath: C. deserticola exhibited caudate sheaths, in contrast to the triangular or semi-circular sheaths observed in C. salsa. Microscopic examination of the S. tragus-parasitizing specimens revealed caudate vascular sheaths, confirming their identity as C. deserticola.

Figure 3.

Histological characters of the fleshy stems of different varieties of Cistanche. (a) C. deserticola (host: H. ammodendron): 1. epidermis, 2. cortex, 3. vascular bundle, 4. medullary ray, 5. pith. (b) Enlarged view of the vascular bundles of C. deserticola (host: H. ammodendron): 1. vascular bundle sheath, 2. phloem, 3. cambium, 4. xylem, 5. vessel. (c) C. salsa: 1. epidermis, 2. leaf trace bundle, 3. cortex, 4. vascular bundle, 5. medullary ray, 6. pith[3]. (d) Enlarged view of the vascular bundles of C. salsa: 1. vascular bundle sheath, 2. poreline cell, 3. fiber, 4. phloem, 5. vessel, 6. xylem[3]. (e) Cistanche (host: S. tragus): 1. epidermis, 2. cortex, 3. vascular bundle, 4. medullary ray, 5. pith. (f) Enlarged view of the vascular bundles of Cistanche (host: S. tragus): 1. vascular bundle sheath, 2. phloem, 3. cambium, 4. xylem, 5. vessel.

Molecular identification of the root parasite on S. tragus

-

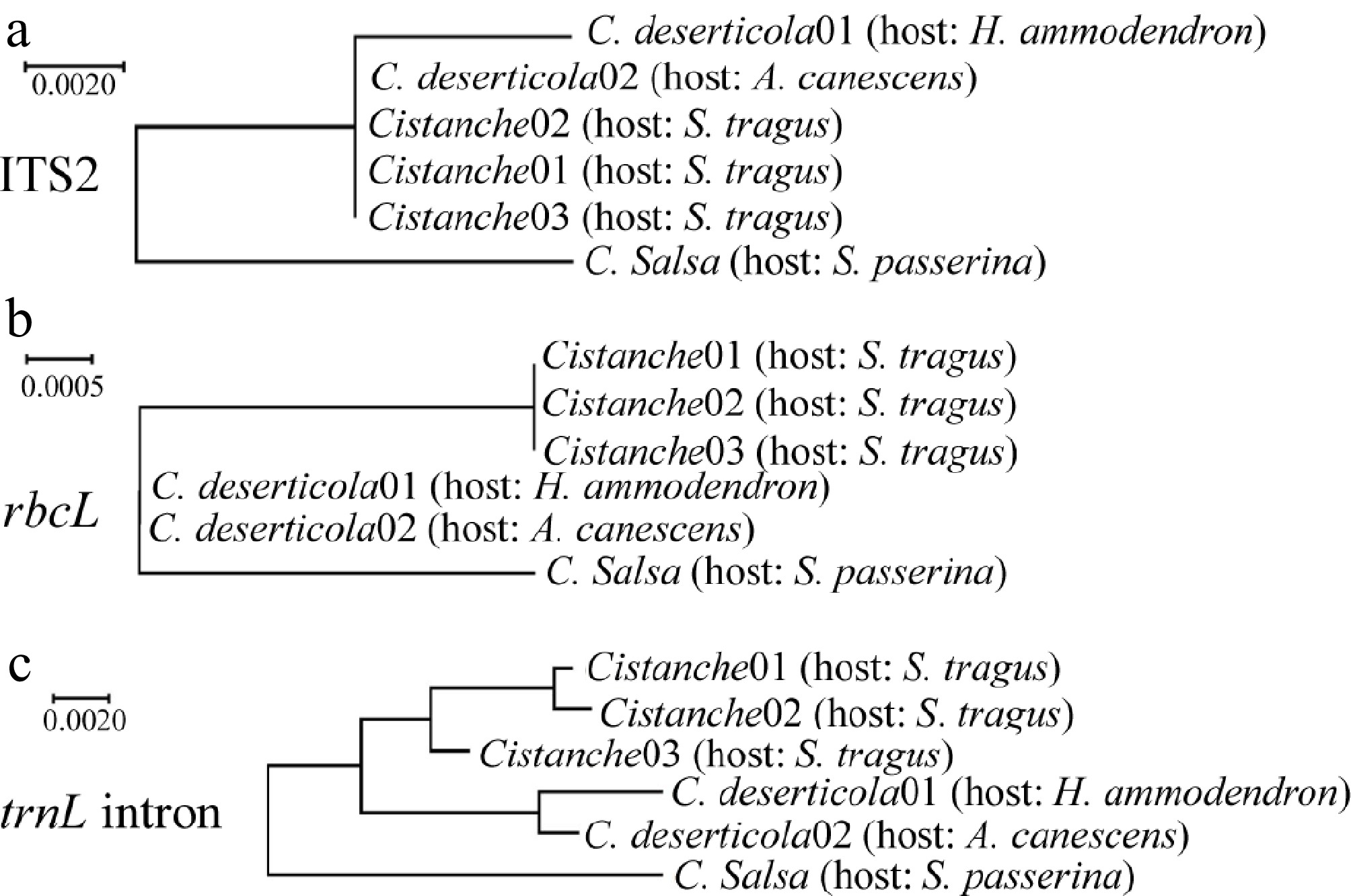

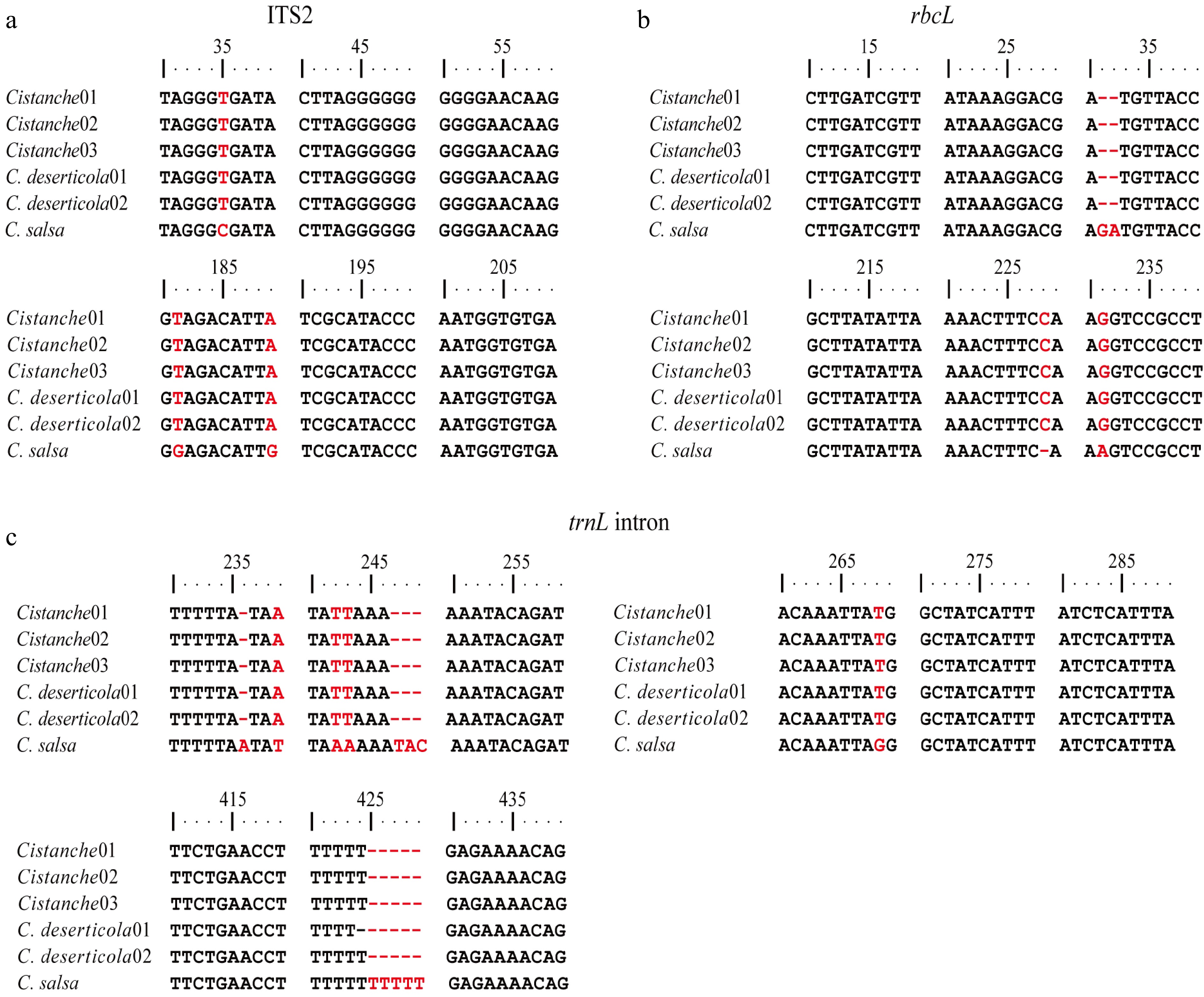

To complement morphological identification, molecular identification was conducted using three DNA barcode regions: ITS2, rbcL, and trnL intron. Following PCR amplification and sequencing, phylogenetic trees were constructed for each marker (Fig. 4). The Cistanche specimens parasitizing S. tragus consistently cluster with C. deserticola in all three phylogenetic trees, providing robust molecular support for their taxonomic classification as this species. Comparative sequence alignment revealed distinct nucleotide differences between C. deserticola and C. salsa (Fig. 5). The locus information that can be used to distinguish between the two species was analyzed. Specifically, three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified within the ITS2 region at positions 35, 181, and 189. Within the rbcL gene, three discriminatory sites were detected, including one SNP and two insertion-deletion (InDel) mutations. The most significant divergence was observed in the trnL intron, which exhibited seven sequence variations, comprising four SNPs, and three InDels. Notably, 94.12% of the variable sites in the S. tragus-parasitizing specimens matched those of C. deserticola, further confirming their taxonomic assignment. Furthermore, a thymine-rich mononucleotide repeat motif (beginning at position 419) was identified within the trnL intron, which exhibits potential for the development of a species-specific simple sequence repeat (SSR) marker to distinguish between C. deserticola and C. salsa.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of Cistanche species. (a) Phylogenetic tree based on ITS2 sequences. (b) Phylogenetic tree based on rbcL sequences. (c) Phylogenetic tree based on trnL intron sequences.

Figure 5.

Major gene divergences among Cistanche species. Cistanche01–03 represents Cistanche (host: S. tragus); C. deserticola01 represents C. deserticola (host: H. ammodendron); C. deserticola02 represents C. deserticola (host: A. canescens). (a) ITS2. (b) rbcL. (c) trnL intron.

Although the root parasites on S. tragus matched C. deserticola at all major differential sites, minor sequence variations were observed at several secondary sites (such as rbcL -40, trnL intron -3) (Supplementary Figs S2 and S3). The proportion of such secondary variations in the S. tragus-parasitizing specimens was calculated to be 0% in ITS2, 0.30% in rbcL, and 1.34% in the trnL intron.

Measurement of the medicinal components of C. deserticola parasitized on S. tragus

-

The principal bioactive components in C. deserticola specimens parasitizing S. tragus were quantitatively analyzed (Supplementary Fig. S4). HPLC quantification revealed that the total content of echinacoside and acteoside exceeded the threshold (0.30%, as stipulated by the Chinese Pharmacopoeia) by 14- to 26-fold (Table 3). Despite seasonal fluctuations in bioactive compounds and the 4-month age of the present samples, we believe the observed total content range (4.4%–7.9%), higher than that commonly seen in C. deserticola parasitizing H. ammodendron (0.2%–2.0%) and A. canescens (1.1%–3.8%)[3,25−30], strongly suggests its significant quality potential.

Table 3. Concentration of important medicinal components of C. deserticola parasitizing S. tragus.

Sample Echinacoside Acteoside C. deserticola01 7.69% 0.29% C. deserticola02 5.51% 0.12% C. deserticola03 4.36% 0.08% -

C. deserticola was historically considered to exclusively parasitize H. ammodendron until 2017, when its parasitism on A. canescens was reported, challenging the traditional paradigm of its host specificity. In this study, the known host range of C. deserticola is expanded through comprehensive morphological and molecular analyses, confirming its successful parasitism on the roots of S. tragus. Although all three host species (H. ammodendron, A. canescens, and S. tragus) belong to the Amaranthaceae family, the present findings indicate that C. deserticola exhibits species-selective parasitism, which we hypothesize may be mediated by host-derived signaling molecules. S. tragus, a native species in China, demonstrates extremely strong resistance to environmental stresses and high adaptability. The identification of S. tragus as a new host for C. deserticola reminds us that other species within the genus Salsola may also serve as viable hosts. Although S. tragus is an annual plant, the genus Salsola includes life forms such as perennial herbs, semi-shrubs, and shrubs[31], all exhibiting robust ecological adaptability. Additionally, several Salsola species, including S. richteri and S. paletzkiana (which can reach 3 m in height[32]), demonstrate remarkable biomass potential. A systematic screening of Salsola species to identify optimal hosts, coupled with the establishment of appropriate cultivation protocols, could alleviate the current resource bottleneck in C. deserticola production. This approach would not only extend the suitable cultivation region of C. deserticola, but also promote the resource utilization of marginal lands, including saline-alkali and sandy soils.

C. deserticola and C. salsa exhibit high morphological similarity, which challenges reliable differentiation using traditional identification methods. The present comprehensive analysis of three DNA barcode regions (ITS2, rbcL, and trnL intron) revealed multiple diagnostic molecular markers, including both SNP and InDel variations, that effectively differentiate these two species. Among these regions, the trnL intron exhibited a greater number of polymorphic sites, indicating its superior discriminatory power and robustness as a DNA barcode for distinguishing C. deserticola from C. salsa. The combined use of all three barcodes provided complementary discrimination power, significantly enhancing the accuracy and reliability of species identification. Multilocus analysis confirmed that the S. tragus-parasitizing specimens shared 94.12% of the diagnostic sites with C. deserticola, providing strong support for their taxonomic classification within this species. Meanwhile, minor sequence variations at secondary sites may reflect intraspecific genetic diversity within C. deserticola, host-induced adaptive evolution, or potential hybridization events with related species. These findings establish a robust molecular framework for distinguishing these morphologically similar species, with important implications for quality control in the production of Cistanches Herba, conservation of wild resources, and further studies on host-parasite coevolution.

Extensive research has demonstrated that host identity significantly shapes the secondary metabolite profiles of parasitic plants[33,34]. This study reports the novel discovery of C. deserticola parasitizing S. tragus, representing the first documented case of its parasitism within the genus Salsola. Thus, it is critically important to assess the quality variations in C. deserticola associated with different hosts, namely Haloxylon, Atriplex, and Salsola. The present results demonstrate that C. deserticola grown on S. tragus exhibits markedly superior medicinal quality compared to that parasitizing H. ammodendron or A. canescens. Specifically, the combined content of echinacoside and acteoside exceeded the pharmacopoeia threshold by 14- to 26-fold. Hence, the present findings provide a theoretical basis for the host screening strategy in the industrial cultivation of C. deserticola.

-

The host range of C. deserticola was originally believed to be limited to H. ammodendron until the recent finding of its parasitism on A. canescens. Previously, it was found that the C. deserticola seeds, collected from the cultivation base in Qiemo, successfully parasitized another Amaranthaceae species, S. tragus. Through integrated morphological and molecular identification, we confirmed the successful parasitism of C. deserticola on S. tragus. Notably, the content of the main active ingredient was higher in C. deserticola parasitizing S. tragus than in those associated with H. ammodendron or A. canescens.

The discovery of this new host species indicates a broader host adaptability in C. deserticola than previously recognized, although its regional representativeness requires further study. The present findings provide a certain promoting effect on further expanding the artificial cultivation of C. deserticola, which could, in turn, help protect wild Cistanche resources and its native ecosystem.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Dong X, Guo Y, Xiang Q; data collection and draft manuscript preparation: Xiang Q; analysis and interpretation of results: Xiang Q, Li P; manuscript revision: Li P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated in this study are available in the paper and supplementary information files.

-

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Cunqin Jia (Huiqin Biotechnology Co., Ltd) and Mr. Xinyu Li (Yuanhengqizheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd) for kindly providing C. deserticola and S. tragus resources. We acknowledge Prof. Qun Sun (China Agricultural University) for critical reading of the manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 The stem diameter of C. deserticola parasitizing S. tragus. Asterisks represent significant differences (*p < 0.05), based on paired t-test.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Comparative sequence analysis of rbcL. Cistanche01-03 represents Cistanche (host: S. tragus); C. deserticola01 represents C. deserticola (host: H. ammodendron); C. deserticola02 represents C. deserticola (host: A. canescens).

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Comparative sequence analysis of trnL intron. Cistanche01−03 represents Cistanche (host: S. tragus); C. deserticola01 represents C. deserticola (host: H. ammodendron); C. deserticola02 represents C. deserticola (host: A. canescens).

- Supplementary Fig. S4 HPLC-UV map of reference substance (a) and test substance for C. deserticola parasitizing S. tragus (b). 1. echinacoside, 2. acteoside.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang Q, Li P, Guo Y, Dong X. 2025. Salsola tragus: a new host for Cistanche deserticola. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e040 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0037

Salsola tragus: a new host for Cistanche deserticola

- Received: 26 July 2025

- Revised: 10 September 2025

- Accepted: 26 September 2025

- Published online: 17 December 2025

Abstract: Cistanche deserticola is a holoparasitic perennial plant, highly valued in traditional Chinese medicine for its tonic properties, particularly for reinforcing the kidney (yang), tonifying essence and blood, and relieving constipation by promoting bowel movement. Historically, it was believed that C. deserticola exclusively parasitized Haloxylon ammodendron. However, the discovery of Atriplex canescens as a host in 2017 expanded the known host range of C. deserticola. In this study, both morphological and molecular analyses confirmed that C. deserticola can also successfully parasitize Salsola tragus, a species renowned for its extreme resilience to saline-alkali, drought, high temperatures, wind, and sand. The adaptability of S. tragus is comparable to that of A. canescens and superior to that of H. ammodendron, and the concentration of bioactive compounds in C. deserticola parasitizing S. tragus was found to be higher than in those parasitizing H. ammodendron and A. canescens. These results provide a theoretical basis for further expanding the artificial cultivation of C. deserticola.

-

Key words:

- Cistanche deserticola /

- Salsola tragus /

- Holoparasitic /

- DNA barcoding /

- Host specificity