-

Plastics are characterized by their lightweight nature, durability, and low cost, and have been extensively utilized across various fields since their invention[1]. Research indicates that global cumulative plastic consumption reached 5 billion metric tons by the end of 2025[2]. Under the influence of various environmental factors, plastics break down into micro-particles, which Thompson et al. defined as microplastics (MPs) with a diameter of less than 5 mm[3]. The widespread use of plastics has led to the generation of large quantities of MPs. Eriksen et al. investigated the abundance of plastic particles in the surface waters of the Southern Hemisphere and found that MPs (< 4.75 mm) accounted for a striking 92.4% of the total[4]. In the natural environment, MPs persist and can enter organisms through contaminated soils and aquatic systems. For animals, ingestion of MPs can cause histopathological alterations in gastrointestinal tissues, induce oxidative stress, and impair antioxidant defense systems, thereby compromising their health[5]. In contrast, exposure of plants to MPs can result in mechanical damage to cellular structures and elevate intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, leading to cellular injury and suppression of chlorophyll synthesis essential for photosynthesis[6,7]. MPs can also bioaccumulate along food chains and ultimately enter the human body, where potential health risks include endocrine disruption, inflammatory responses, and carcinogenicity[8]. Beyond their inherent toxicity, MPs can act as vectors for other environmental contaminants, thereby exacerbating combined ecological impacts[9].

One study reveals that only 9% of globally produced plastic waste is recycled, 12% is incinerated, and the remaining 79% is either landfilled or released into the natural environment[10]. However, neither landfilling nor incineration represents an ideal solution for MP waste management. Due to their high chemical stability and the presence of added plasticizers, MPs can persist in natural environments for extended periods, with half-lives ranging from 0.19 to 5,000 years, depending on polymer type[11,12]. Landfilling not only consumes substantial land resources but also compromises long-term soil fertility, hindering sustainable land use. Furthermore, leachates generated during degradation can infiltrate and contaminate groundwater[13,14]. While incineration can completely remove MPs from the environment, it readily induces secondary pollution, including air contamination and the release of hazardous additives such as highly toxic dioxins[15,16]. Alternative waste management through microbial-mediated biodegradation has attracted considerable research interest due to its potential to thoroughly remove both conventional plastics and smaller MPs while avoiding secondary pollution.

Microbial degradation of MPs refers to the process in which microorganisms (such as bacteria and fungi) secrete specific enzymes to catalyze a series of biochemical reactions, depolymerizing the high molecular chains of MP polymers into smaller molecules (e.g., monomers and oligomers), and ultimately metabolizing these small molecules into compounds such as carbon dioxide (CO2), water (H2O), and biomass. Compared with conventional degradation methods, microbial degradation is considered a more promising approach due to its simpler operation and lower energy consumption. It is an environmentally friendly technology that achieves the dual goals of resource recovery and detoxification[17]. In 2016,Yoshida et al. isolated the bacterium Ideonella sakaiensis 201-F6 from the natural environment, which secretes specific enzymes capable of depolymerizing polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and mineralizing it into CO2 and biomass—providing the first compelling evidence for the feasibility and environmental compatibility of microbial MP degradation[18]. Subsequently, an increasing number of microorganisms have been identified as capable of degrading MPs, including bacteria[19], fungi[20], microalgae[21], and mixed microbial consortia from environmental acclimation or artificial construction[22,23]. Compared with traditional methods, microbial degradation is typically carried out under ambient temperature and pressure, with simple operational requirements and markedly lower energy consumption, making it a promising green and sustainable technology for MP remediation[17].

However, the advancement of MP biodegradation technologies is hindered by several persistent challenges, among which temperature is one of the key determinants. Temperature modulates microbial activity through both direct and indirect pathways[24]. The direct effects follow a typical thermal performance curve: microbial activity generally increases with rising temperature up to an optimum, beyond which activity declines sharply[25]. Indirect effects occur when elevated temperatures alter environmental parameters, such as reducing moisture content, thereby impairing microbial function. Moderate warming may selectively enrich thermotolerant MP-degrading microorganisms, reshaping bacterial community diversity and richness[26]. Conversely, extremely high temperatures can inactivate native PET-degrading enzymes (e.g., PETase), diminish the degradation capacity of non-thermophilic strains, and even disrupt microbial community structure by reducing the abundance of functional taxa[27]. Moderate temperature increases can enhance the activity and efficiency of some MP-degrading microorganisms, whereas excessively high temperatures—particularly during extreme heat events—are more likely to inhibit microbial degradation processes. Furthermore, under the context of global warming, the duration and frequency of extreme heat events such as heatwaves and droughts are continuously increasing[8,28]. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) predicts that the global annual average temperature between 2025 and 2029 will be 1.2–1.9 °C higher than pre-industrial levels. Another recent study indicates a significant increase in the likelihood of extreme heat events occurring in multiple countries between May 2024 and May 2025[29]. The marked upward trend in global average temperatures driven by climate change may have substantial implications for the microbial degradation of MPs.

To investigate the impact of high temperature environments on microbial degradation of MPs, this review synthesizes previous studies to provide a detailed overview of the mechanisms involved and the microorganisms responsible. It systematically examines the effects of thermophilic conditions on degradation pathways and efficiency. Furthermore, it delves into microbial enhancement strategies aimed at mitigating thermal stress, with the goal of supporting the development of efficient and adaptable biodegradation technologies for MPs. This work also aims to offer theoretical insights and practical guidance for studying microbial degradation under extreme environmental conditions.

-

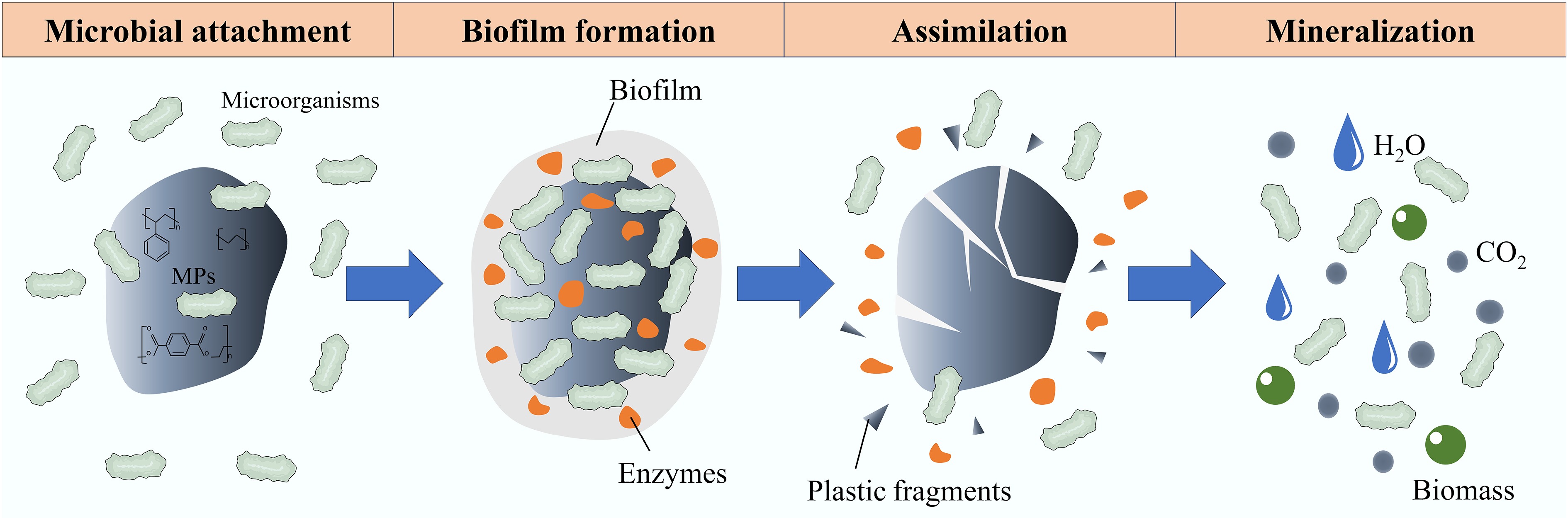

Microbial degradation of MPs is the process by which microorganisms metabolize MPs into CO2, H2O, and other intermediates[30]. As shown in Fig. 1, microorganisms attach to the surfaces of MPs via physicochemical interactions[31] and secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) to form a biofilm, which enhances attachment stability and alters MP surface properties[32,33]. The core degradation step is enzymatic depolymerization, where extracellular enzymes like hydrolases and oxidoreductases cleave polymer chains into smaller units[34,35]. For recalcitrant MPs, oxidases first introduce oxygen-containing functional groups to enable hydrolysis[36].

The resulting low-molecular-weight compounds are transported into cells[37], and mineralized via pathways like β-oxidation and the TCA cycle to produce energy and end products, which include CO2 and water under aerobic conditions, or methane and ammonia under anaerobic conditions[38−41]. While bacterial and fungal degradation both involve attachment, biofilm formation, and enzymatic breakdown, they differ in that bacteria use both surface-bound and intracellular enzymes synergistically, whereas fungi rely primarily on extracellular enzymes, leading to different metabolic products[42−44]. The process is influenced by MP properties, microbial types, and environmental conditions, though the effects of extremely high temperatures remain poorly understood.

Microbial species involved in degradation

Bacteria

-

Since Lee et al. first demonstrated the MP-degrading capability of bacteria under pure culture conditions, this field has garnered sustained research interest[45]. The biodegradation process typically begins with bacterial attachment to the MP surface, leading to biofilm formation. This process involves bacterial selectivity towards different MPs. For instance, a 2019 study showed that Alcanivorax borkumensis can colonize MP surfaces and secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) to form biofilms on low-density polyethylene (LDPE). The biofilm area formed on LDPE was significantly larger than on PET and polystyrene (PS), and the bacterium demonstrated substantial LDPE degradation[46]. Following biofilm formation, specific enzymes secreted by the bacteria play a crucial role in MP degradation. Yoshida et al. discovered Ideonella sakaiensis, a bacterium capable of completely degrading PET, and elucidated its complete degradation pathway. This pathway involves microorganisms utilizing MPs as a carbon source and degrading them through a series of enzymatic reactions. Their research clarified the roles and importance of PETase and MHETase(mono(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate hydrolase) in the stepwise degradation of PET, delineated the molecular pathway of bacterial PET degradation, and further revealed the potential of bacteria in mitigating MP pollution[18]. Additionally, alkane hydroxylase and reductase secreted by Pseudomonas strains have been confirmed to cleave carbon-carbon bonds in long chains, enabling targeted polyethylene (PE) degradation[47].

Bacteria are among the most ubiquitous and abundant groups of microorganisms on Earth, characterized by their wide ecological distribution, strong environmental adaptability, and rapid metabolic activity. Bacteria capable of degrading MPs originate from a wide range of environments, including marine habitats[48], soil ecosystems[49], landfill sites[23], and wastewater treatment plants[50]. For example, Shahnawaz et al. found that Streptomyces longisporoflavus, isolated from rhizosphere soil, can degrade PE[51]. Ameen et al. reported that Streptomyces gobitricini, isolated from heavy metal-contaminated soil, can degrade Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC)[52]. Chauhan et al. demonstrated that Exiguobacterium sibiricum and Exiguobacterium undae, isolated from wetland environments, can degrade PS[53]. Pathak & Navneet isolated Bacillus subtilis V8, Pseudomonas aeruginosa V1, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus V4, Pseudomonas putida C25, and Paracoccus aminophilus B14 from various garbage dumps, all of which significantly degraded PE, albeit with varying efficiencies ranging from 11.72% to 18.21%, highlighting differential degradation capabilities among bacterial strains for the same MPs[54].

Studies indicate that approximately 21% of bacterial taxa involved in MP biodegradation belong to Bacillus spp. and Pseudomonas spp.[55]. For instance, B. cereus and Bacillus gottheilii, isolated by Auta et al. from mangrove sediments in the Malaysian peninsula, demonstrated the potential to degrade MPs. Over a 40-day cultivation period, these strains degraded Polypropylene (PP), PE, PS, and PET, with weight loss rates reaching up to 7.4%[19]. In another study, Muhonja et al. used strains of Bacillus cereus and Pseudomonas putida isolated from a landfill, which reduced LDPE weight by 35.72% and 2.80%, respectively, under conditions of 37 °C over 16 weeks. Furthermore, Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis in that study revealed an increase in functional groups such as aldehyde, ether, and carboxyl groups, confirming that microorganisms can gradually break down the long-chain hydrocarbon structure of PE into smaller molecular compounds through metabolic activity[56].

Bacteria have emerged as highly promising agents for the biodegradation of MPs due to their environmental resilience, ease of cultivation, wide distribution across diverse habitats, and significant application potential.

Expanding the scope beyond conventional sources, Thapa et al. reported the isolation of a Pseudomonas sp. strain from Arctic samples that demonstrated notable efficacy in degrading 2-Hydroxyethyl terephthalate (HMET), an intermediate derived from PET degradation[57]. Their findings provide evidence that bacteria inhabiting extreme environments, including thermally extreme niches, may possess functional adaptability for MP biodegradation.

Fungi

-

Fungi play crucial roles in natural ecosystems by forming symbiotic relationships with other organisms, serving as a food source for higher trophic levels, and acting as decomposers of organic matter[58]. Due to their robust metabolic capabilities and ability to degrade recalcitrant structures, fungi are increasingly recognized for their potential in the biodegradation of MPs in the environment[59]. In a pioneering study, Oberbeckmann et al. identified diverse fungal communities colonizing the surfaces of PET plastic bottles in marine environments, with dominant phyla including Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria[60]. Several of these fungal groups are highly associated with MP degradation functions. For instance, some strains of Flavobacteriaceae secrete hydrocarbon-degrading enzymes[61], Cryomorphaceae produce dioxygenases and dehalogenases conferring MP degradation capabilities[62], and Alternaria alternata FB1 can degrade MPs by secreting monooxygenases and peroxidases[63].

Fungi exhibit several advantages in MP degradation. Firstly, they can secrete hydrophobins that facilitate attachment to the hydrophobic surfaces of MPs. Secondly, their filamentous hyphae can penetrate deep into substrates and secrete extracellular digestive enzymes that efficiently depolymerize MPs into smaller molecules for subsequent absorption and metabolism[64]. Additionally, fungi produce a wide variety of non-specific enzymes capable of catalyzing diverse chemical reactions; for example, lignin-degrading enzymes such as laccases, peroxidases, and redox enzymes can break down complex organic molecules[65]. Zhang et al. observed significant upregulation of two laccase-like multicopper oxidase (LMCO) genes (AFLA-006190 and AFLA-053930) in Aspergillus flavus during degradation, indicating the functional involvement of these enzymes in the process[66].

A wide range of naturally occurring fungi possess the ability to degrade various types of MPs. For example, Sheik et al. isolated Lasiodiplodia theobromae from within plants, which secretes laccase, forms biofilms on MP surfaces, and demonstrates degradation capabilities for both PE and PP[67]. Moyses et al. reported that Penicillium simplicissimum, isolated from industrial waste, significantly degrades PET due to its secretion of lipases[68]. Yanto et al. found that Pestalotiopsis sp. achieved a 74.4% degradation rate for PS, attributed to its production of highly active lignin peroxidase and laccase, which provide specific oxidative capacity to directly attack aromatic C–H and C–C resonance bonds[69].

Compared to bacteria, fungi often exhibit superior degradation capabilities for structurally complex polymers. For polyurethane (PU), which is resistant to degradation due to its ester bonds, Fusarium tricinctum shows higher degradation efficiency[70]. Conversely, Sun et al. found that Enterobacter hormaechei, isolated from soil, degrades poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT)—which contains aromatic ring structures—more effectively[42]. This suggests that fungi may hold greater potential for degrading certain recalcitrant MPs.

Compared to bacteria, fungi often exhibit lower substrate specificity and can grow over a broader pH range[71]. Notably, Zalerion maritimum, a marine fungus isolated by Paço et al. significantly reduced the mass of PE-MPs under oligotrophic conditions, achieving a degradation rate of 43% within just 14 d and continuing degradation over a 28-d period[72]. This finding not only further underscores the high efficacy of fungi in degrading MPs but also reveals their biodegradation potential under extreme conditions, such as nutrient-limited environments. Additionally, fungi often form symbiotic relationships with other organisms, such as plants, which may further enhance their potential as a tool for MP remediation.

Algae

-

The use of specific algal and cyanobacterial species for MP biodegradation represents an emerging biotechnological approach. Initial scientific interest was sparked by the ability of microorganisms like the cyanobacteria Oscillatoria subbrevis and Phormidium lucidum to colonize MP surfaces. Subsequent research indicates that algal-mediated biodegradation offers distinct advantages over bacterial or fungal systems. As photoautotrophs, algae require only light, CO2, and inorganic nutrients, avoiding competition for the MPs as a carbon source. Furthermore, they are generally non-toxic, minimizing the risk of environmental contamination from the process itself. Finally, the biomass generated can be valorized, for instance, as a feedstock for bioplastic production[73,74].

The degradation process typically begins with the colonization of the MP surface and the formation of a biofilm. The adhering cells, such as Oscillatoria subbrevis and Phormidium lucidum, isolated from wastewater, then secrete extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and specific enzymes[75]. This secretory cocktail facilitates the breakdown of polymer chains. For example, the cited cyanobacteria achieved a 30% degradation rate of PE within 42 d without pre-treatment. Similarly, research demonstrated that extracellular secretions from the cyanobacterium Cyanothece sp. could efficiently degrade PS, suggesting the action of potent, diffusible biocatalysts[76].

Beyond direct degradation, algae contribute to a plastic circular economy by synthesizing bioplastics intrinsically. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), a common bioplastic, is naturally produced as an energy reserve by over 100 algal species, with concentrations ranging from 0.04% to 80% of dry biomass[77]. This highlights the potential to integrate MP remediation with the sustainable production of biodegradable polymers.

Although research is expanding, current studies on algal MP degradation remain limited. A significant theoretical constraint is that algae, being predominantly mesophilic, have limited survivability under extreme conditions like high temperatures. Consequently, it is improbable that native algal species capable of efficient MP degradation would naturally proliferate in such environments, directing bioprospecting efforts toward temperate or engineered systems.

-

High temperatures can effectively alter the physical and chemical structure of MPs, thereby enhancing their susceptibility to microbial enzymes. When the ambient temperature exceeds the glass transition temperature (Tg) of a polymer, its molecular chains achieve maximum mobility and the structure becomes highly disordered[78]. According to the chain flexibility hypothesis proposed by Inderthal et al., the increased mobility and hydrophobicity of the polymer chains significantly enhance enzyme-substrate contact and catalytic efficiency, thereby substantially increasing the biodegradation rate[79]. Consequently, parameters such as the polymer's Tg, melting temperature (Tm), molecular weight (MW), and crystallinity can, to some extent, reflect the degradation rate of MPs. Key indicators for common MPs are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Approximate Tm, Tg, and density of common MPs[81]

Types of MPs Tm (°C) Tg (°C) Density (g·cm–3) LDPE 180–240 110 0.917–0.940 HDPE 210–270 110 0.940–0.970 PP 200–280 10 0.900–0.910 PS 170–280 90 1.040–1.050 PLA 170–180 50–80 1.25–1.27 PET 264 73–78 1.300–1.400 HDPE: High-density polyethylene; PLA: Polylactic acid. Taking PET as an example, when the ambient temperature surpasses its glass transition temperature, its structure transitions from a glassy state to an amorphous state. This enhances the mobility of the polymer chain segments, making them more vulnerable to attack by microbial enzymes[80]. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures induces thermal aging in MPs, leading to polymer chain scission and an increase in the carbonyl index. This results in a microstructure that is more amenable to enzymatic hydrolysis. For instance, pretreating PET at 70–80 °C can significantly reduce its crystallinity, thereby enhancing its biodegradation efficiency. Furthermore, elevated temperatures can strengthen hydrophobic interactions between microbial cells and the MP surface, promoting microbial adhesion and biofilm formation. Research has shown that under fermentation conditions at 75–85 °C, the rate of biofilm formation on MP surfaces accelerates markedly, thus hastening the degradation process[81]. Therefore, increasing temperature serves as an effective means to promote the degradation of MPs themselves.

The dual impact of high temperature on microorganisms

-

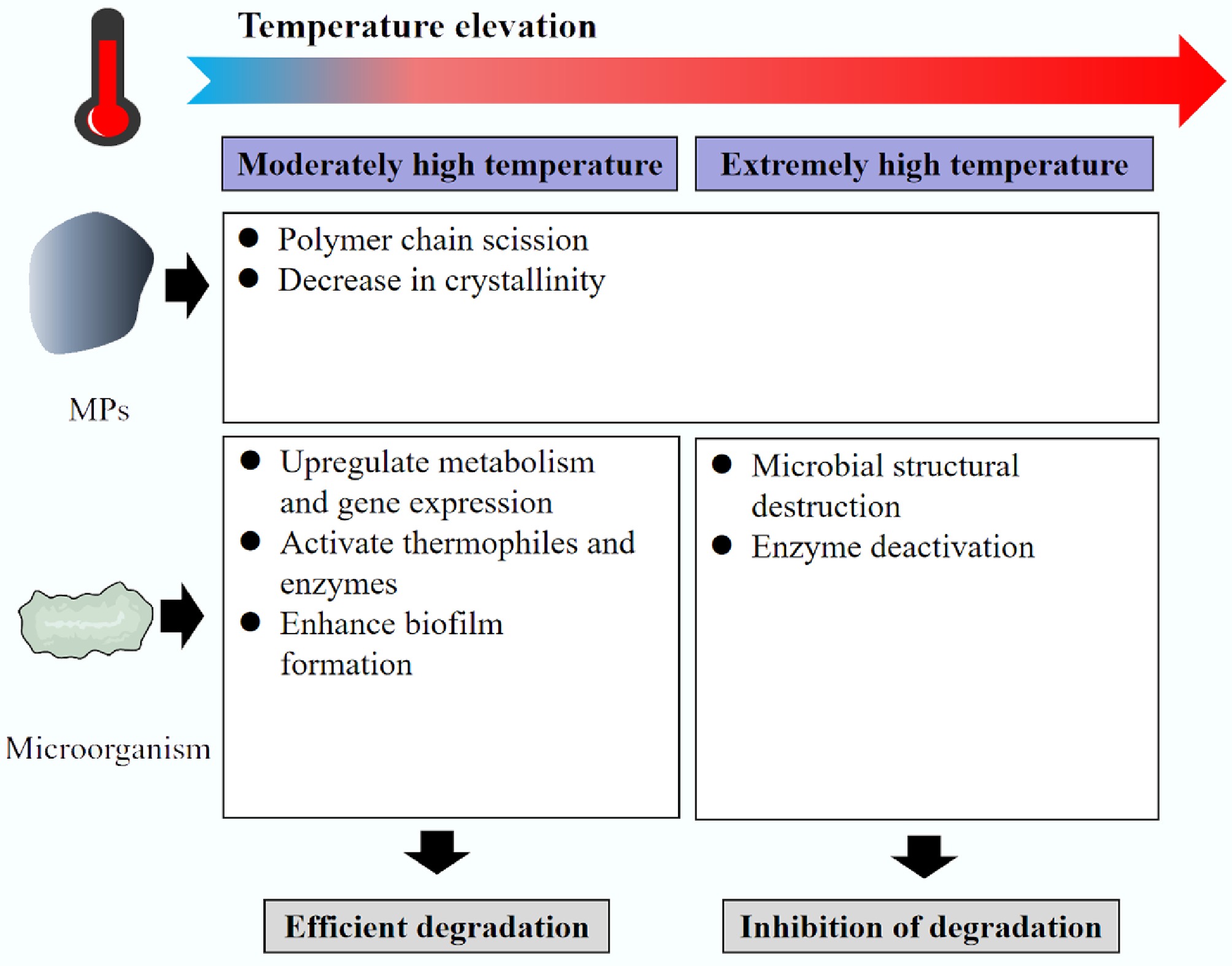

Microorganisms can be classified based on their optimal growth temperature ranges into mesophiles (20–45 °C), thermophiles (45–70 °C), and hyperthermophiles (70–121 °C)[82]. Within their suitable temperature range, microbial activity and metabolic rates are generally highest. Increasing the temperature within this optimal range not only stimulates microbial metabolism but may also upregulate the expression of functional genes associated with degradation. For example, Guo et al. demonstrated that at 25 °C, the abundance of metabolic functional genes involved in carbon and nitrogen cycles in soil reached its peak, accompanied by a corresponding increase in the MP degradation rate[83]. However, when the temperature exceeds the maximum tolerance limit of microorganisms, it can lead to the collapse of ordinary microbial communities. Exposure to temperatures beyond their upper tolerance limit causes denaturation and inactivation of microbial enzymes, disruption of cell membranes, and nucleic acid breakage, ultimately resulting in cell death and a sharp decline in microbial abundance and activity[84].

Thermophiles have evolved a series of adaptive mechanisms to cope with high-temperature environments, such as secreting heat shock proteins and forming more stable cell membranes. Some thermophiles capable of growing under extremely high temperatures have been confirmed to possess MP-degrading capabilities. Özdemir et al. isolated two Gram-positive thermophilic strains, Anoxybacillus flavithermus ST3 and Anoxybacillus sp. ST6, from hot spring sediments, which could degrade PE at 55–60 °C[85].

For thermophilic microorganisms capable of degrading MPs, the secretion of thermostable enzymes that maintain high catalytic activity at elevated temperatures is key to achieving degradation. These enzymes acquire exceptional thermal stability through mechanisms such as increased salt bridges and the formation of more compact protein structures. For instance, the esterase PpEst, derived from Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes, can degrade PBAT at 65 °C[86]; a protease PET2 from a marine microorganism can even degrade PET at 70 °C[87]. The Table 2 summarizes some thermophilic enzymes involved in the microbial degradation of MPs.

Table 2. Partially thermostable MPs-degrading enzymes

Name Source Optimal Temperature (°C) Degradable

MPs typesRef. LIP1 Pseudomonas chlororaphis PA23 40 PHA, PLA [88] LIP2 Pseudomonas chlororaphis PA23 45 PHA, PLA [88] Cut190 Saccharomonospora viridis 65–75 PET [89] Cutinase Bacillus sp. KY0701 50 PCL [90] EstB3 Moss-associated microorganisms 48 PBAT [91] EstC7 Moss-associated microorganisms 50 PBAT [91] PHA: Polyhydroxyalkanoates; PCL: Polycaprolactone As shown in Fig. 2, when temperatures enter the extreme high range, their impact on the microbial degradation of MPs becomes more complex, presenting a scenario where inhibition and potential promotion coexist. The influence of temperature on the microbial degradation of MPs represents a continuous spectrum. High temperatures systematically promote the degradation process primarily by optimizing the microbial growth environment and modifying the MP substrate. In contrast, extremely high temperatures act as a double-edged sword: on one hand, they prepare MPs, making them 'easier to digest' through strong thermal aging effects, select for MP-degrading thermophiles, and activate efficient thermophilic enzyme systems; on the other hand, they also pose a severe survival challenge to microbial communities themselves, potentially directly inhibiting degradation activity.

-

Geothermal environments, such as hot springs and hydrothermal vents, represent natural reservoirs of thermophilic microorganisms capable of degrading MPs. A study by Pavlov et al. on the Kuirau Park geothermal springs in New Zealand, utilizing 16S rRNA gene sequencing and metagenomic analysis, revealed a high abundance of putative MP-degrading microbial taxa in this high-temperature environment, including genera such as Flavobacterium, Pseudomonas, Sphingomonas, and Rheinheimera[78]. These microorganisms remain active at temperatures up to 80 °C, constituting valuable resources for research on high-temperature biodegradation of MPs. In another study, 34 bacterial strains were isolated from the El Tragadero and Quilcate hot springs in Peru, 11 of which demonstrated the ability to degrade PET, with Bacillus species identified as the dominant degraders[92]. Furthermore, Brevibacillus thermoruber, isolated from the Marikostinovo hot spring in Bulgaria, was shown to efficiently degrade PCL under high temperature[93]. Additionally, Actinomadura sp., a thermophilic strain isolated from soil by Sukkhum et al., exhibited the capacity to degrade PLA at 70 °C, further expanding the known ecological sources of MP-degrading thermophiles[94].

Geothermal environments harbor a rich diversity of microbial resources and have been confirmed to host numerous thermophilic microorganisms with MP-degrading potential, along with associated functional genes. These ecosystems serve as important natural repositories for the discovery of novel thermostable degrading enzymes and highly efficient microbial strains for MP biodegradation.

Industrial high-temperature environment microorganisms

-

In addition to naturally occurring thermophilic microorganisms, certain high-temperature industrial processes have also been found to enrich microbial taxa capable of degrading MPs. During an investigation of high-temperature composting systems, Li et al. detected microbial communities, including Acinetobacter and Bacillus, colonizing MP surfaces and confirmed their ability to degrade PET[95]. Similarly, Bacillus sp. BCBT21, isolated from agricultural waste compost by Dang et al.[96], was demonstrated to degrade various types of MPs with distinct chemical compositions under elevated temperatures. In a pioneering study, Chen et al. validated the efficient removal of MPs from sludge in a 200-ton hyperthermophilic composting (hTC) system, achieving a removal rate of 43.7% within 45 d. Their findings further revealed that the core degradation mechanism relied on the exceptional bio-oxidative capacity of ultra-thermophilic genera such as Thermus, Bacillus, and Geobacillus[97]. Other bacteria with degradation potential identified in high-temperature composting environments include Thermomonospora fusca[98] and Thermobifida alba AHK119[99]. In a study by Cazaudehore et al. using inocula from agricultural byproduct treatment facilities, the degradation efficiency of eight types of MPs was compared under thermophilic and mesophilic conditions. Results indicated faster degradation under thermophilic conditions, with community analysis revealing a predominance of Firmicutes, Coprothermobacter, and Euryarchaeota under high temperatures, whereas Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, Chloroflexi, and Desulfobacterota were more abundant under mesophilic conditions[100]. These findings underscore that high-temperature industrial settings also serve as significant sources of thermophilic microbial resources.

Genetically engineered thermophilic degrading strains

-

Genetic engineering offers novel strategies for developing heat-resistant microorganisms capable of degrading MPs. For instance, Kim et al. applied adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) to modify Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, resulting in a heat shock-tolerant mutant capable of surviving and effectively degrading MPs at temperatures as high as 135 °C. This mutant exhibited significantly improved survival rates and degradation efficiency compared to the wild-type strain, highlighting the potential of engineering approaches to enhance both thermal stability and degradation performance in microorganisms[101]. Additionally, protein engineering techniques have been widely employed to improve the thermal stability of MP-degrading enzymes, thereby enhancing their catalytic efficiency under high-temperature conditions[102,103]. Therefore, genetic engineering provides a crucial pathway for enhancing the thermal stability and efficiency of MP degradation systems, either through direct microbial modification or optimization of key enzymes. Beyond these biological approaches, the synergistic application of non-biological strategies, such as physicochemical intensification methods, holds significant potential to further broaden the practical application scenarios for MP degradation by thermotolerant microorganisms.

-

Thermophiles are capable of maintaining membrane integrity and preventing protein denaturation at high temperatures through specialized cell membrane structures (enriched with long-chain saturated fatty acids or glycerol dialkyl glycerol tetraether lipids) and the secretion of extremozymes with unique structural adaptations[104]. Thermophiles generally exhibit superior efficiency in MP degradation compared to mesophilic microorganisms. Research by Cazaudehore et al. demonstrated that the degradation rate of MPs under thermophilic conditions (58 °C) is significantly faster than under mesophilic conditions (38 °C)[100].

Thermophiles are widely distributed in natural environments (e.g., deep-sea hydrothermal vents, volcanoes, and hot springs) and artificial thermal environments (e.g., composting systems, food processing plants, and greenhouses). Geobacillus thermocatenulatus, isolated from soil by Tomita et al., can effectively degrade polyamide (PA) at 60 °C and represents one of the earliest reported thermophilic strains applied in PA degradation[105]. Beyond high-temperature environments, MP waste landfills are also considered rich sources of MP-degrading microorganisms. Under mesophilic conditions, Bacteroidota, Chloroflexi, Desulfobacterota, Firmicutes, and Euryarchaeota are dominant, whereas thermophilic conditions are predominantly characterized by Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Coprothermobacter[81]. Therefore, when searching for thermophilic consortia with MP-biodegrading capabilities, focus can be placed on these phyla, followed by subsequent high-temperature degradation experiments to validate their performance.

Furthermore, thermostable enzymes capable of MP-degrading can be identified by comparing their sequences with those of known degraders, enabling more precise and rapid discovery of thermostable enzymatic resources. For instance, comparing target protein sequences with known enzymes in specialized MP biodegradation databases, where a sequence similarity ≥ 30% is considered significant[81]. With advancing research, Erickson et al. constructed a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) based on a set of known thermostable MP-degrading enzymes, providing a more efficient method for screening thermostable enzymes through advanced computational modeling[106].

Thermal stability enhancement of degrading enzymes

-

The application of thermophiles helps address challenges such as enzyme inactivation and low microbial degradation efficiency under extremely high temperatures. Their widespread environmental distribution also suggests significant potential for future discoveries. However, thermophiles are not a universal solution for high-temperature MP degradation. For example, studies by Tomita et al. showed that while Geobacillus pallidus can degrade certain types of PA, it is ineffective against PA with higher crystallinity[105], indicating the need for additional technical approaches to enhance microbial strains.

Typically, when temperatures exceed an enzyme's maximum thermal tolerance limit, structural denaturation occurs. In such cases, enzyme engineering techniques can be employed to enhance thermal stability[81]. Even enzymes with inherent strong thermostability can be further improved through such methods. Taking IsPETase as an example, this wild-type PET-degrading enzyme derived from Ideonella sakaiensis exhibits extremely poor thermal stability, typically requiring reaction temperatures below 30 °C, which is far lower than the Tg of PET (60–70 °C). Through protein engineering, Son et al. designed an IsPETase mutant (S121E/D186H/S242T/N246D) targeting substrate-binding sites[107]. Compared to the wild-type enzyme, this mutant not only maintained activity for up to 20 d at 40 °C but also exhibited a 58-fold increase in degradation activity. To further improve the thermal stability of IsPETase, Bell et al. introduced disulfide bonds, optimized β-sheet structures, and fixed the conformation of Trp185, resulting in the variant HotPETase (Tm = 82.5 °C). This variant features a new disulfide bridge formed between the introduced Cys233 and Cys282 pair, substantially enhancing both thermostability and activity, enabling effective MP degradation at the Tg of PET[108]. Additionally, Tournier et al. enhanced the stability of a cutinase by introducing disulfide bonds and inducing a tyrosine-to-glycine mutation, enabling it to degrade 90% of PET at 72 °C[109]. These studies demonstrate that disulfide bonds and hydrogen bond networks within protein structures are critical targets for improving enzymatic thermal stability, and enzyme engineering serves as an effective strategy for enhancing the heat resistance of degrading enzymes.

Construction of thermotolerant engineered bacteria

-

To address the challenges of microbial MP degradation under extremely high-temperature conditions, in addition to exploring natural thermophiles, effective strategies include using genetic engineering and synthetic biology to construct heat-resistant engineered strains or to modify microorganisms to secrete degradation enzymes that remain structurally stable at high temperatures. In terms of engineering microbial strains, genomic modifications can be employed to enhance thermal tolerance. For example, Tang et al. engineered Bacillus subtilis to express a xylan-inducible lipase from Burkholderia cepacian for Bacillus degradation in high-temperature environments (120 °C). The resulting engineered strain exhibited significantly improved heat resistance and completely degraded PCL within 6–7 d in a composting environment, with a threefold increase in degradation efficiency compared to the wild-type strain[110]. In another study, Yan et al. adopted a genetic engineering strategy by introducing a gene encoding a thermostable cutinase derived from compost metagenomes into the thermophilic anaerobe Clostridium thermocellum, successfully constructing a thermophilic whole-cell biocatalyst. This engineered strain efficiently degraded PET films at 60 °C, achieving a weight loss of over 60% within 14 d, significantly outperforming mesophilic strains[111]. Wei et al. heterologously expressed the cutinase TfCut2 from Thermobifida fusca in both Bacillus subtilis and E. coli. The recombinant TfCut2 demonstrated higher thermal stability and more effectively degraded the mobile amorphous fraction (MAF) of PET[112].

These studies indicate that engineered strains constructed using genetic engineering technology can be designed to possess specific desired functions, substantially improving thermal stability and degradation efficiency under high-temperature conditions, thereby helping to better overcome environmental limitations.

Design and application of synthetic microbial consortia

-

Compared to single strains, microbial consortia generally demonstrate superior biodegradation performance and higher degradation efficiency due to their enhanced environmental adaptability, richer repertoire of enzymes, and synergistic metabolic interactions among community members[113]. A study investigating PBST-degrading microorganisms under high-temperature conditions (50 °C) revealed a 'collaborative mechanism' within the enriched microbial community. Among the strains isolated from the poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBST) surface, Paenibacillus was responsible for disrupting the surface integrity of the MPs, creating favorable conditions for subsequent enzymatic reactions. Bacillus served as the primary degrader, secreting esterases/lipases to cleave the ester bonds in PBST. Chromobacterium played a crucial role in metabolizing harmful byproducts generated during the degradation process, optimizing the degradation environment, and ensuring the cooperative efficiency of the community. This study uncovered the mechanism through which microbial consortia enhance efficiency and strengthen adaptive capacity via 'multi-strain collaboration' under high-temperature conditions, confirming the feasibility of constructing synthetic microbial consortia for MPs degradation in high-temperature environments[114].

-

Several strategies have been proposed to mitigate the impact of extremely high-temperature environments on microbial degradation of MPs. Protein engineering, particularly enzyme redesign and the construction of engineered strains, represents prominent approaches to address this issue. However, these techniques still face several challenges, such as the time-consuming, complex, and costly processes of protein engineering; short enzyme lifespans with difficulties in recovery and reuse; and similar limitations encountered in synthetically engineered microorganisms[115]. Furthermore, the diversity of MP types in the environment complicates degradation efforts. Current research predominantly focuses on PET, with limited microbial resources identified for other prevalent MPs such as PE[116] or PCL[117].

When the reaction temperature approaches the melting or Tg of MPs, increased molecular mobility can enhance enzymatic biodegradation. However, different MPs exhibit distinct optimal degradation temperatures—for instance, approximately 72 °C for PET, and 58 °C for PLA[81]. These variations necessitate tailored temperature strategies. Moreover, the thermal stability of enzymes must align with the reaction temperature to ensure efficient degradation while avoiding enzyme denaturation due to excessive heat. Beyond temperature, microbial activity is highly dependent on other environmental conditions, including pH, oxygen availability, and nutrient supply. Additionally, microbial remediation is typically a natural process that may require extended timeframes compared to other MP removal methods, thus limiting its applicability in scenarios requiring urgent remediation.

The highly dispersed nature of MPs in the environment limits their accessibility to microorganisms, thereby hindering degradation efficiency. Biochar loading technology offers a promising strategy to overcome this limitation through the simultaneous sequestration of MPs and provision of a protective habitat for degradative microbes.

Environmental impact assessment

-

The introduction of exogenous microorganisms may lead to resource competition with native microbial communities, potentially disrupting local ecological balance through unpredictable shifts in community structure. Although bioaugmentation techniques may enhance degradation capacity, horizontal gene transfer to indigenous microbes could occur, raising concerns over long-term ecological consequences and potential environmental risks. Furthermore, the addition of nutrients or surfactants to facilitate microbial activity may lead to environmental leakage, potentially causing secondary issues such as eutrophication. Finally, the introduction of thermophilic bacteria may alter local chemical conditions, potentially mobilizing enriched heavy metals and other contaminants, thereby exacerbating environmental pollution.

Future research directions

-

Future research should focus on the following aspects:

(1) Utilizing advanced cultivation techniques and metagenomic analyses of extreme environments to discover novel thermophilic degrading strains and expand the diversity of available microbial resources. Although numerous thermophiles have been identified from both natural and artificial environments, their application in MP degradation remains constrained—such as a limited range of degradable MPs and narrow microbial diversity. Future efforts should emphasize the exploration of environmental microbiomes to broaden the source and variety of thermophilic degraders.

(2) Leveraging advanced synthetic biology tools to optimize existing thermophilic strains, thereby enhancing their thermal tolerance, degradation efficiency, and environmental compatibility. Techniques such as DNA synthesis, genome engineering, protein synthesis, and cellular assembly have demonstrated potential in enhancing the capability of MP-degrading microbes to perform under extreme temperatures. However, the high cost and operational complexity of current methods limit their widespread application. There is a pressing need to develop new technologies that reduce costs and improve efficiency. For example, whole-cell biocatalysts offer advantages such as lower cost and simpler operation compared to purified enzyme systems[111]. Similarly, extremophiles may exhibit unique functionalities under specific conditions—for instance, halophiles can reduce glucose dependency in PHA production, lowering synthesis costs[118]. Likewise, thermophiles may hold significant potential in the field of MP degradation.

-

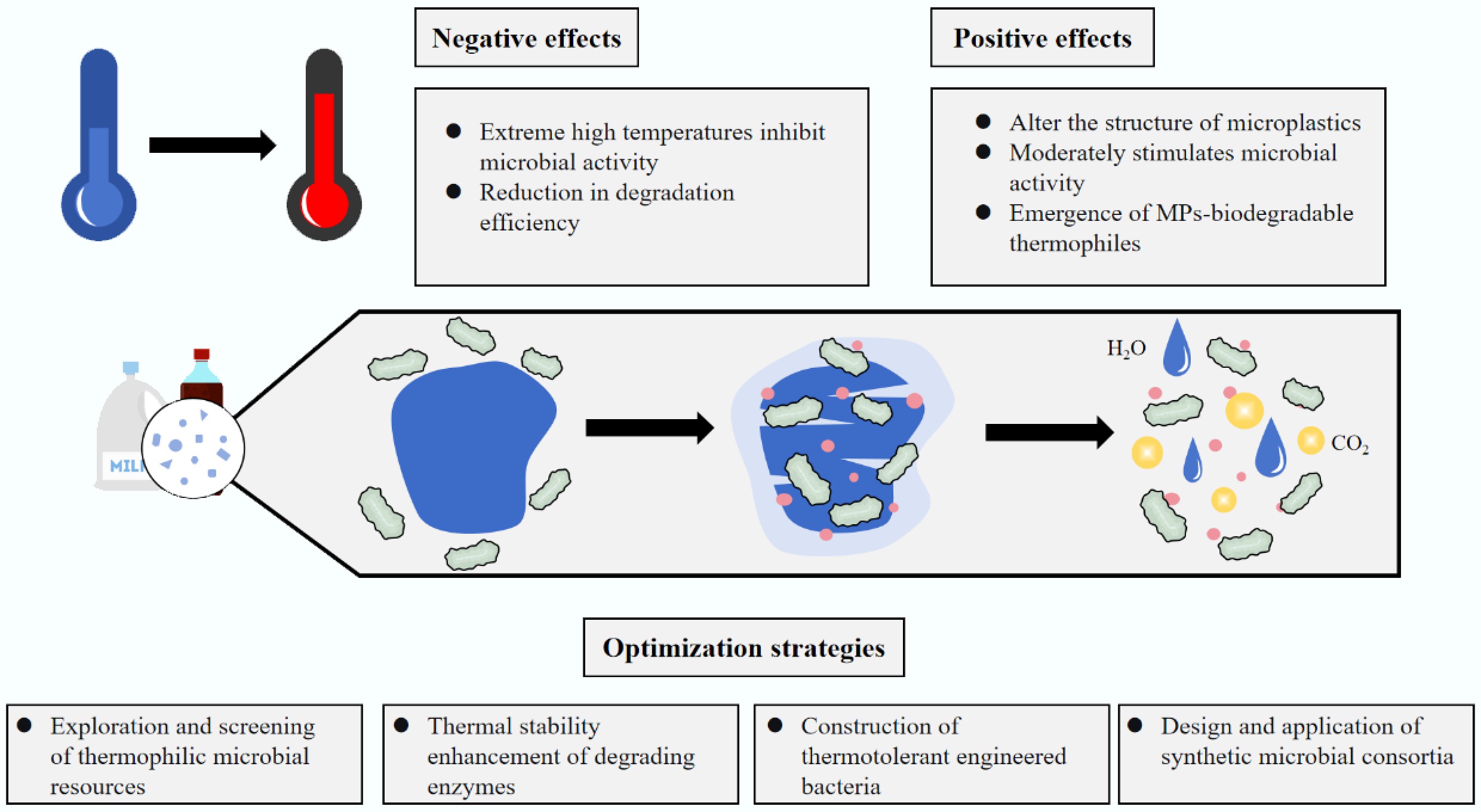

Among various MP removal methods, microbial degradation is regarded as one of the most promising approaches. Compared to traditional landfilling and incineration, this method is environmentally benign, free from secondary pollution, and highly specific, making it a current research hotspot in the field of MP pollution control. Microbial degradation is driven by enzymatic catalysis and is highly susceptible to environmental conditions. High-temperature conditions offer unique advantages for MP degradation, such as reducing MP hardness and crystallinity, thereby influencing microbial metabolic activity and enzymatic reaction rates under certain conditions. However, excessively high temperatures may also disrupt microbial community structures, cause irreversible protein denaturation, and lead to loss of enzymatic activity, thereby inhibiting degradation efficiency. This review focuses on the unique niche of extremely high temperatures and systematically summarizes the dual effects of temperature rise on microbial degradation of MPs: moderate high temperatures can enhance microbial community activity and enzymatic efficiency, while extremely high temperatures, although potentially facilitating microbial adhesion and degradation indirectly by altering MP surface properties, are more likely to suppress microbial abundance and activity, resulting in cell death and enzyme inactivation. Thermotolerant microorganisms, such as thermophilic bacteria, exhibit significant potential for MP degradation. In response to the practical needs for MP degradation under extremely high-temperature conditions, this review proposes multiple strategies, including exploring natural thermophilic microbial resources, enhancing the thermal stability and activity of degradation enzymes through enzyme engineering, constructing heat-resistant engineered microbial consortia, and developing composite microbial systems. It also highlights current limitations such as operational complexity, long processing periods, and high costs. Future research should focus on leveraging advanced technologies to discover more thermophilic microbial resources and genetically modifying existing thermophiles to improve their heat resistance and degradation capacity, thereby better addressing MP pollution under high temperatures.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design, writing—manuscript revision and editing were performed by Zheng Yuan, Yanzheng Gao, Lei Tang; data collection and analysis were performed by Zheng Yuan; the first draft of the manuscript was written by Zheng Yuan, Lei Tang, Rongxin Lv; the manuscript was polished by Fredrick Gudda, Ahmed Mosa, Patryk Oleszczuk, Tatiana Minkina. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data used in this article are derived from public domain resources.

-

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFE0110800), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42507036), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M761444).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

The dual regulatory mechanisms of temperature on microbial MP biodegradation: inhibition vs enhancement.

Thermophiles achieve efficient MP degradation via heat-resistant enzymes and membrane adaptations.

Integrated framework: environmental sampling, computational screening, enzyme engineering, and consortium design.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan Z, Lv R, Gudda F, Mosa A, Oleszczuk P, et al. 2025. Impacts of high temperatures on microbial degradation of microplastics and strategies for optimization. New Contaminants 1: e018 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0019

Impacts of high temperatures on microbial degradation of microplastics and strategies for optimization

- Received: 27 October 2025

- Revised: 14 November 2025

- Accepted: 27 November 2025

- Published online: 11 December 2025

Abstract: The extensive use and improper disposal of plastics have led to severe environmental pollution, with the potential for microplastic accumulation in humans posing significant health risks. Microbial degradation has emerged as a research focus in the control of plastic pollution due to its ecological sustainability and substrate specificity. The efficiency of microbial degradation is temperature-dependent. Moderate increases in temperature can decrease the hardness and crystallinity of microplastics (MPs), thereby facilitating microbial activity and degradation. However, excessively high temperatures may activate microorganisms and denature proteins, resulting in diminished degradation. Against the backdrop of global warming and rising temperatures, studying the impact of extreme heat on microbial degradation of MPs is important. Research has shown that under extremely high temperature conditions, certain naturally occurring thermophilic microorganisms exhibit considerable potential for MP degradation. To enhance the heat resistance of degrading microbial communities and improve microplastic degradation efficiency, this review proposes multiple strategies, including exploring natural thermophilic microbial resources, enhancing the thermal stability and activity of degrading enzymes through enzyme engineering, and constructing heat-resistant engineered strains and synthetic microbial consortia. Simultaneously, limitations of current technologies are summarized, and future directions for improvement are suggested, providing a reference for further research, and offering technical insights into the high-temperature biodegradation of other pollutants.

-

Key words:

- Microplastics /

- Biodegradation /

- High temperature /

- Thermophilic microorganisms /

- Enzyme engineering