-

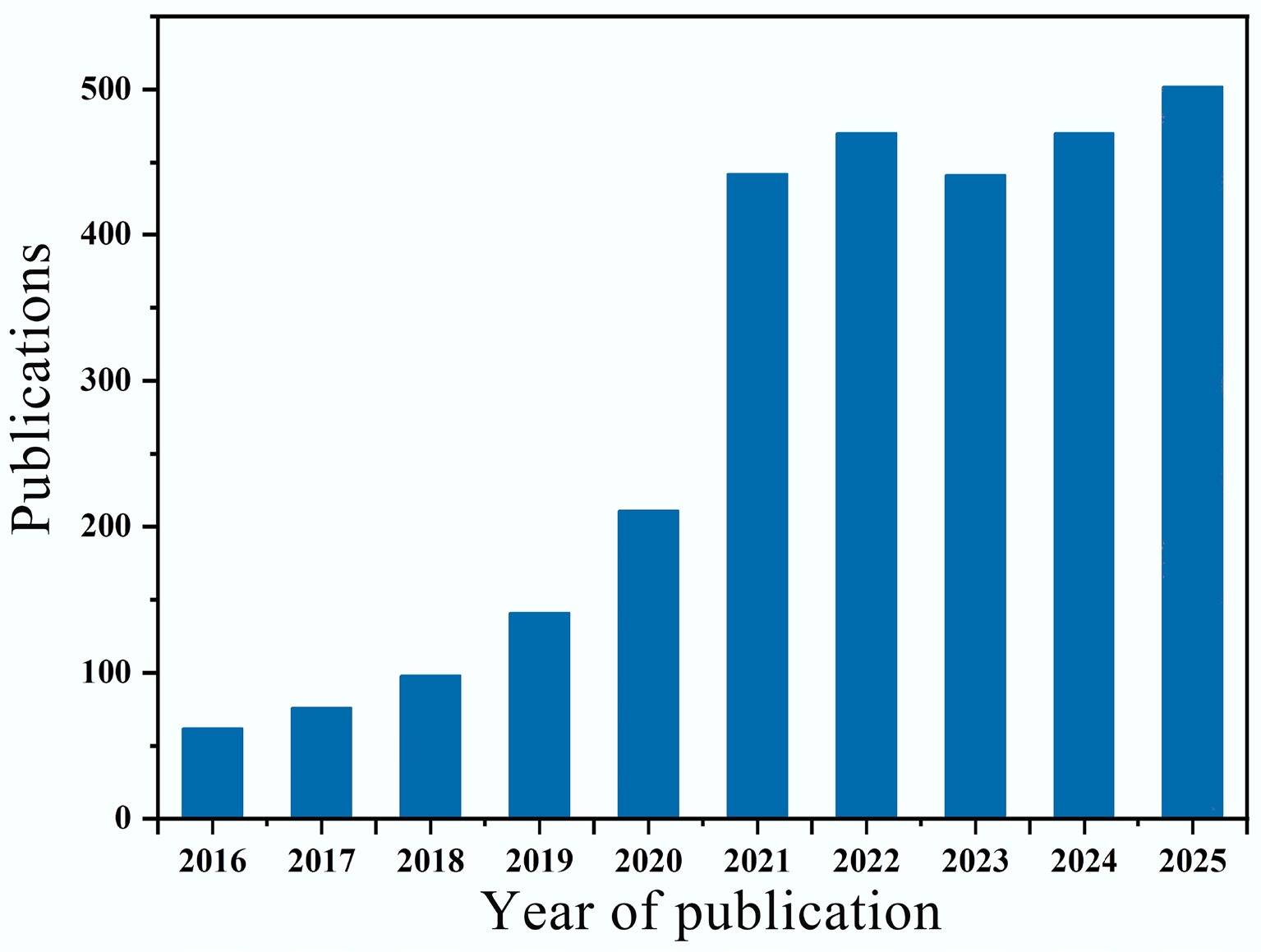

The ongoing global industrialization has posed formidable challenges to the control of new contaminants such as persistent organic pollutants (POPs), endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), and antibiotics. These trace contaminants are highly toxic, refractory, and bioaccumulative, posing potentially irreversible risks to ecosystems and human health[1,2]. Accordingly, the development of advanced and efficient remediation technologies is urgently required. Currently, technologies for controlling new contaminants are generally classified into four categories: chemical, physical, membrane-based, and biological approaches. Chemical methods mainly involve advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), including Fenton, photocatalytic, electrocatalytic, and mechanochemical oxidation[3]. Physical methods depend on adsorption and filtration, where contaminants are transferred from liquid to solid phases through interactions such as pore filling, electrostatic attraction, hydrophobic effects, ion exchange, hydrogen bonding, and π–π stacking. Membrane processes combine adsorption, ultrafiltration, and membrane bioreactors[4]. Biological techniques utilize metabolic pathways to decompose and transform pollutants. However, the inherent properties of emerging pollutants limit the effectiveness of physical, membrane, and biological methods, often resulting in incomplete removal, high costs, or secondary pollution. In contrast, AOPs have garnered significant scientific interest (Fig. 1) due to their ability to generate highly reactive species such as hydroxyl (•OH) and sulfate (SO4•−) radicals capable of degrading even complex and recalcitrant organic pollutants[5−7]. Nevertheless, the practical deployment of techniques like photo-, electro-, and mechano-catalytic oxidation is hindered by challenges such as weather dependency, substantial energy inputs, and inefficient energy conversion.

Among various AOPs, Fenton catalysis is widely used in the treatment of new contaminants due to its simple operation. However, to overcome the drawbacks of homogeneous systems—such as a narrow pH range and iron sludge formation—research now focuses more on heterogeneous catalytic systems. Persulfate (PS)-based oxidants, including peroxydisulfate (PDS) and peroxymonosulfate (PMS)[8], have emerged as promising alternatives to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Compared with H2O2, persulfates generate sulfate radicals (SO4•−) featuring a longer half-life (30−40 μs), higher redox potential (2.5−3.1 V vs NHE)[9], broader pH adaptability (pH 2−9), and superior reaction selectivity[10,11]. In addition, compared to liquid H2O2, solid PS offers practical advantages in terms of easier storage and transportation.

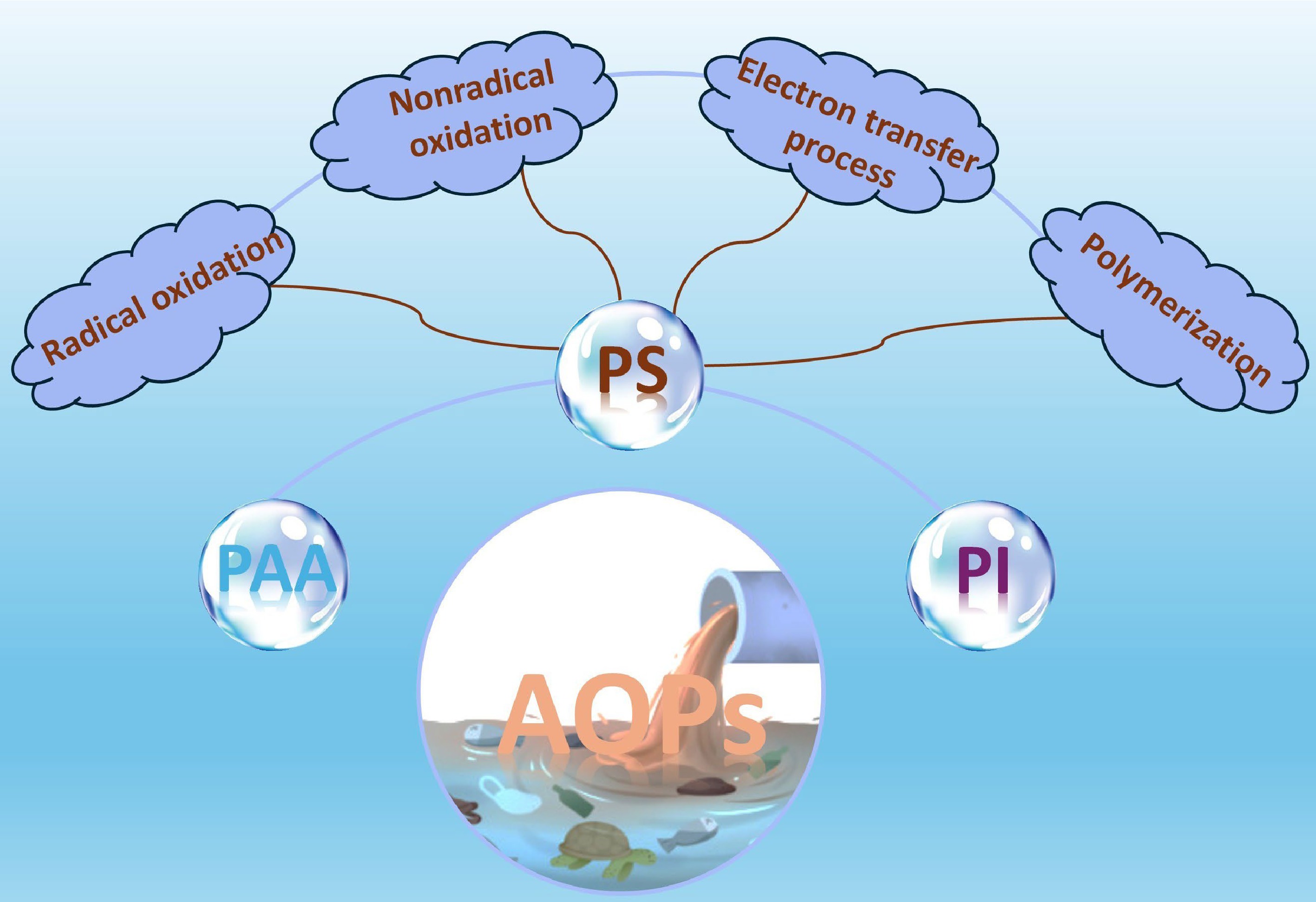

This perspective first provides a systematic account of heterogeneous PS-based AOPs and their four principal reaction pathways, followed by a concise discussion of recent studies employing peracetic acid (PAA) and periodate (PI) as alternative oxidants (Fig. 2). The concluding section offers an in-depth analysis of the key challenges confronting AOPs in safeguarding water quality and presents an integrated assessment of their current progress and future prospects.

-

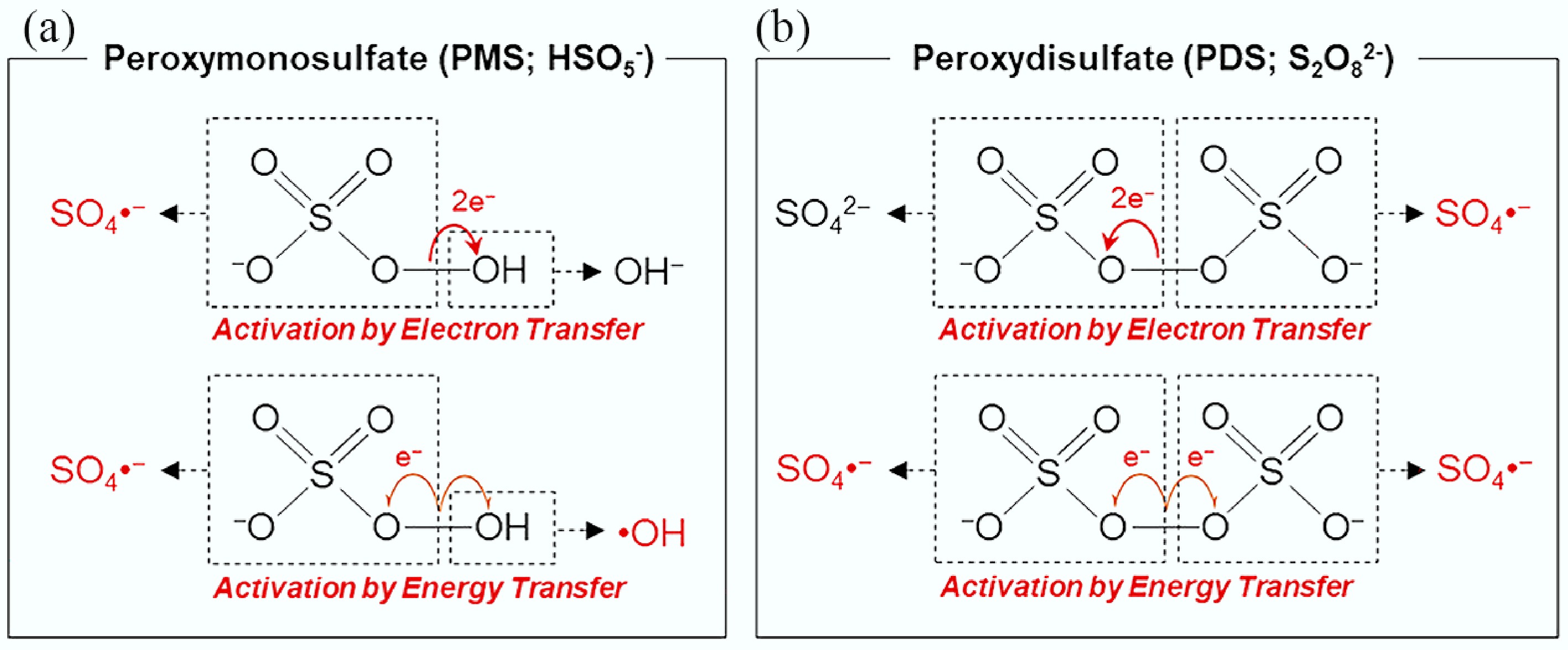

PS mainly includes PMS and PDS, which differ in both chemical structure and activation behavior (Fig. 3). Upon activation, they generate a variety of reactive species such as •OH, SO4•−, and singlet oxygen (1O2). PMS possesses an asymmetric structure (H−O−O−SO3−) and a relatively long peroxide O−O bond (1.326 Å)[12], with a pKa of approximately 9.4. It exhibits strong oxidative capability under acidic conditions and is commonly available as a triple salt, 2KHSO5·KHSO4·K2SO4[8]. The activation of PMS proceeds primarily through two bond cleavage pathways. The first involves O−O bond scission, directly yielding SO4•− and •OH, while the second involves O−H bond cleavage to form the SO5•− intermediate, which subsequently undergoes self-quenching to generate 1O2 (2SO5•− → 1O2 + 2SO42−)[13]. In contrast, PDS features a symmetric structure (−O3S−O−O−SO3−) with a slightly shorter O−O bond (1.322 Å), conferring higher structural stability. In the absence of electron donors such as organic pollutants, PDS can retain its oxidative potential for extended periods without substantial decomposition. In heterogeneous systems, electron transfer from transition metals promotes the cleavage of the peroxide bond in PDS, leading predominantly to the generation of SO4•−, which can further convert to •OH. Moreover, during hydrolysis, PDS may yield superoxide radicals (O2•−) via the reaction: 2S2O82− + 2H2O → 3SO42− + SO4•− + O2•− + 4H+[14], and subsequent disproportionation of O2•− ultimately gives rise to 1O2 (2O2•− + 2H+ →1O2 + H2O2). •OH, as a highly reactive and nonselective oxidizing species, possesses a standard redox potential of 2.80 V vs NHE[15] and can rapidly react with most inorganic and organic pollutants. However, its nonselective nature also renders •OH highly susceptible to quenching by coexisting water matrix components such as natural organic matter (NOM), effluent organic matter (EfOM), and common anions, thereby reducing its practical oxidation efficiency. In contrast, SO4•− exhibits a higher thermodynamic redox potential (approximately 2.5−3.1 V vs NHE) and not only displays stronger oxidative capability, but also maintains effective degradation performance toward target organics even in the presence of NOM or EfOM. Nevertheless, both SO4•− and •OH are short-lived species, and their reactivity in real aquatic environments can be significantly affected by background inorganic ions (e.g., HCO3−/CO32−, Cl−) and macromolecular organic matter, potentially leading to the formation of halogenated byproducts and secondary environmental risks[16]. In comparison, 1O2 is a longer-lived reactive species with a moderate oxidation potential (~0.81 V vs NHE)[17]. Owing to its unoccupied π* antibonding orbital, 1O2 exhibits pronounced electrophilicity and reaction selectivity[18], preferentially attacking electron-rich moieties in organic pollutants to achieve selective oxidation. Beyond these radical and nonradical oxidants, high-valent metal-oxo species (HVMOs) have emerged as important nonradical intermediates in heterogeneous PS-based AOPs[19]. These species typically possess high redox potentials (> 1.95 V vs NHE)[20], relatively long lifetimes, and elevated steady-state concentrations, while being less affected by common anions in water. As a result, HVMOs demonstrate superior selectivity toward electron-rich, recalcitrant contaminants. At present, the removal of emerging pollutants is generally considered to proceed through four possible mechanisms in heterogeneous PS-based AOPs: radical oxidation, nonradical oxidation (including 1O2 and HVMOs), catalyst-mediated electron transfer, and polymerization pathways.

Figure 3.

Activation of (a) peroxymonosulfate (PMS), and (b) peroxydisulfate (PDS). Reprinted from Lee et al.[10] with permission. Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society.

Radical oxidation

-

In heterogeneous PS-based AOPs, •OH and SO4•− are generally recognized as the predominant reactive species. The lifetime of •OH is extremely short, on the order of 10−9−10−3 s[21,22], and its steady-state concentration in natural waters is typically within 10−17−10−15 mol L−1. Nevertheless, owing to its high redox potential, •OH can rapidly and nonselectively oxidize a wide spectrum of organic micropollutants within a short reaction window. The degradation pathways of •OH generally involve three principal routes: electrophilic addition, hydrogen abstraction, and single-electron transfer[21,22]. In electrophilic addition, •OH acts as an electrophile that attacks electron-rich moieties such as unsaturated alkenes or aromatic rings, initiating addition reactions. Hydrogen abstraction occurs when •OH targets the C−H bonds of organic pollutants, removing hydrogen atoms and facilitating structural cleavage and degradation. The single-electron transfer mechanism is often observed in reactions between •OH and common inorganic anions (e.g., Cl−, NO3−, PO43−, SO42−), yielding less reactive anionic radicals. This phenomenon explains the susceptibility of •OH to background water constituents during practical treatment applications.

In contrast, SO4•− is typically produced from PS or sulfite precursors upon activation by external energy inputs such as heat, ultraviolet irradiation, or transition metals. With a half-life of approximately 30−40 μs, SO4•− exhibits longer persistence compared to •OH and demonstrates pronounced substrate selectivity during oxidation. The rate constants for its reactions with electron-donating compounds are often several orders of magnitude higher than those with electron-withdrawing compounds, demonstrating its strong selectivity. However, this characteristic is a drawback in the design of AOP-based treatment devices/facilities, which should account for the different treatment times of different pollutants. The mechanistic pathways of SO4•− likewise encompass radical addition, hydrogen abstraction, and single-electron transfer[23,24]. Radical addition primarily occurs at aromatic rings or C=C double bonds, involving the formation of transient radical adducts. Hydrogen abstraction mainly targets C−H bonds in aliphatic compounds, where longer bond lengths generally favor dehydrogenation, though •OH typically exhibits higher reactivity in such processes. Single-electron transfer is prevalent for organics bearing electron-rich functional groups (e.g., amino, amido, or aromatic structures), whose electron-donating characteristics facilitate efficient electron transfer between the pollutant and SO4•−.

Nonradical oxidation

-

Nonradical AOPs have recently attracted extensive attention owing to their low sensitivity toward nontarget substrates, high electrophilicity, and specific affinity for electron-rich pollutants, thereby providing an ideal strategy for the selective degradation of new contaminants. Among the various nonradical oxidants, 1O2 has shown remarkable advantages in AOPs due to its mild oxidative reactivity, relatively long lifetime, and pronounced selectivity toward electron-rich organic structures. Moreover, its selective oxidation behavior effectively suppresses the formation of toxic halogenated byproducts, making 1O2 a highly promising reactive species for contaminant-specific degradation. However, several challenges still hinder its practical implementation: (1) the inherently low selectivity of 1O2 generation; (2) coexistence and competitive reactions with other reactive oxygen species; and (3) facile deactivation under heterogeneous conditions via nonradiative relaxation and mass transfer limitations.

It has been reported that alkaline conditions (pH > 9.3) favor the nonradical pathway in PMS systems, where PMS undergoes self-decomposition to produce 1O2, and the accumulation of quinone intermediates further promotes its generation[25]. Most current studies have thus focused on improving the 1O2 yield through catalyst design and reaction environment optimization. For example, the asymmetric coordination and spin-state modulation of catalysts are crucial yet challenging strategies for efficient 1O2 production. Construction of asymmetric Fe−S−Co catalytic structures has been shown to induce low-spin states at Co sites, enabling precise control over S−O bond cleavage in PMS. This process facilitates spin-state conversion of molecular oxygen, forming 1O2 through electron inversion or spin-pairing mechanisms[26]. Alternatively, nonmetallic boron doping has been proposed to modulate Fe 3d orbital energy levels, enhancing d-p orbital coupling to promote PMS activation and selective 1O2 formation[27]. Defect engineering of carbon-supported single-atom catalysts (CS-SACs) has also been demonstrated as an effective means to tailor the electronic structure of Co sites, strengthening PMS-catalyst interactions and driving efficient 1O2 production. A turnover frequency (TOF) of up to 9.37 min−1 has been achieved in 4-chlorophenol degradation[28]. Incorporating sulfur atoms into a high-coordination Fe-NSC structure can alter the spin state and electronic environment of Fe sites, thereby optimizing the adsorption-desorption behavior of oxygenated intermediates and achieving nearly 100% 1O2 selectivity[29]. Similarly, iodine single atoms anchored on N-doped carbon substantially reduce the energy barrier for SO5•− formation and drive its disproportionation to yield 1O2 with high efficiency[30]. The above-mentioned studies demonstrate that nonmetal atom doping or single-atom catalysts likewise represent promising approaches for tuning catalyst electronic configurations and improving 1O2 selectivity. In addition, employing electronic delocalization strategies provides an effective spin channel for intermolecular electron transfer in PMS, allowing the intermediates SO4•− and SO5•− to convert with up to 98.4% 1O2 selectivity[31]. The nanoscale confinement effect has also been increasingly exploited to enhance the reactivity, selectivity, and stability of AOP systems. In this context, the directional regulation of 1O2 generation has benefited significantly from confined catalytic architectures. For example, Wang et al.[16] constructed MnO2 nanotubes with phase-controlled crystal structures, where geometric strain and spatial confinement jointly enabled nearly complete PMS conversion to 1O2.

In nonradical oxidation systems, besides 1O2, HVMOs have also attracted extensive attention because of their relatively long lifetime (~10−1 s), high steady-state concentration (~10−8 M), and strong resistance to scavenging by coexisting substances such as natural organic matter[19]. The generation rate of HVMOs is closely correlated with the degradation efficiency of new contaminants, while their formation is often limited by several intrinsic factors, including restricted interfacial electron transfer, weak substrate adsorption, and sluggish redox cycling of metal centers. To address these challenges, recent studies have devoted great efforts to the precise modulation of catalyst electronic structures and coordination environments. For instance, Pan et al.[32] constructed a CoLaOx-HC composite catalyst with finely coupled La−O−Co interfacial orbitals, which optimized the electronic configuration of Co sites, facilitated PMS adsorption and charge transfer, and effectively reduced the energy barrier for Co(IV)=O formation. Chen et al.[33] further introduced oxygen atoms into the secondary coordination shell to create a Fe−N4−C6O2 single-atom catalyst with a locally enhanced electric field. This design preserved structural symmetry while reinforcing Fe-N bond stability, leading to markedly improved Fe(IV)=O generation efficiency, faster pollutant degradation, and sustained catalytic activity exceeding 240 h. In another study, Zou et al.[34] introduced sulfur atoms into the secondary coordination layer of Fe single atoms to subtly regulate the electronic configuration of active centers, promoting the occupation of Fe−O antibonding orbitals within Fe−PMS* complexes, thereby enabling nearly 100% selective generation of Fe(IV)=O. These advances collectively demonstrate that atomic-level coordination tuning and interfacial electronic structure engineering can effectively overcome both kinetic and thermodynamic barriers associated with M(IV)=O formation, offering new directions for developing efficient and stable pollutant degradation technologies.

Nevertheless, the chemical complexity of real water matrices often demands synergistic participation of multiple reactive oxygen species, whereas the conventional 'single catalyst−single reactive species' paradigm is insufficient to meet this requirement. To this end, Yang et al.[35] developed a dual-site catalyst with electric-field responsiveness, enabling temporally controlled and selective generation of Fe(IV)=O and 1O2 within a single PMS activation system. By simple switching between power-on and power-off states, two reactive species could be produced directionally with high selectivities of 96.0% and 90.5%, respectively, providing a promising route for efficient contaminant removal under complex water conditions. In addition, Zeng et al.[36] reported that oxygen-doping-induced work function difference significantly enhanced PMS binding and reduced the energy barrier for *O formation, thereby favoring the concurrent high-yield production of both 1O2 and Fe(IV)=O species.

Electron transfer process

-

The electron transfer process (ETP) involves the interaction between a catalyst (e.g., carbon materials, metal single atoms) and an oxidant (e.g., PS) to form a highly oxidized active complex (e.g., Cat-PS*). This complex can directly oxidize organic pollutants without generating traditional free radicals. The core of this process relies on efficient electron transfer among the catalyst, oxidant, and pollutants, enabling selective oxidation. ETP exhibits distinct advantages over other reaction mechanisms. Unlike 1O2 and HVMOs pathways, which require prior activation of the oxidant, ETP directly facilitates electron transfer at the catalyst interface without the need for any pre-activation process[37]. In contrast to the radical-involved oxidation, in ETP systems, PMS accepts electrons from pollutants to form oxidative complexes (PMS*) with a moderate redox potential (0.6−1.2 V vs NHE) at the catalyst surface, rather than decomposing into radicals that can undergo inefficient self-scavenging or other quenching processes in the solution. Moreover, premixing PMS and catalysts markedly suppresses pollutant degradation in radical-based systems due to spontaneous radical decay, whereas in ETP systems, such premixing exerts negligible influence on removal efficiency. Additionally, ETP exhibits high selectivity toward electron-rich pollutants and maintains stable activity across a wide pH range, making it a more efficient and selective pathway for pollutant degradation[38−40]. However, the development of the ETP pathway still faces key scientific challenges: the dual electron donor-acceptor properties of PS trigger competitive reactions at the catalyst interface, resulting in the coexistence of ETP with the radical pathway. This multi-pathway phenomenon severely restricts the selectivity and efficiency of ETP, and designing catalysts to achieve a pure ETP pathway has become a critical research focus. Reports indicate that by enhancing the adsorption affinity for PDS through inert silicate layer defect engineering strategies, utilizing the lattice-confined Fe(II)/Fe(III) redox cycle to promote charge transfer across the interface, and employing the coordination confinement effect to suppress metal leaching, nearly 100% ETP-dominated degradation has been successfully achieved[41]. Other studies suggest that doping with high electronegativity fluorine (F) to modulate the spin state of Co3O4 enhances the adsorption affinity of active sites for PMS, thereby promoting the formation of selective PMS* complexes that mediate the ETP process[42].

Polymerization

-

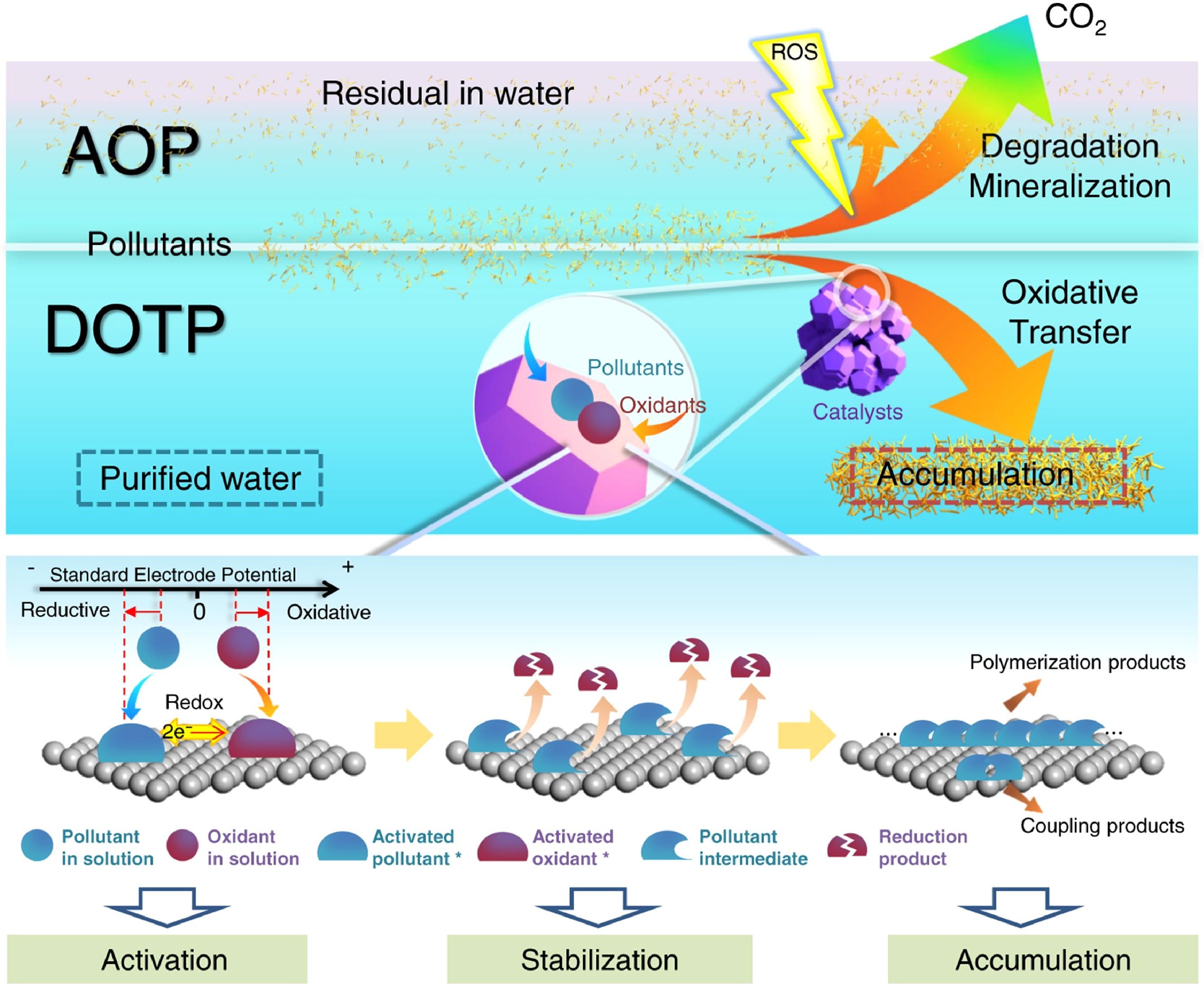

To address the ambiguity in reaction mechanisms and the contradiction of electron disequilibrium in heterogeneous PS-based AOP systems, Zhang et al.[43] conducted an in-depth investigation and, in 2022, a newly discerned AOP pathway was proposed in which the removal of organic pollutants is primarily governed by a direct oxidation transfer process (DOTP). Distinct from conventional mineralization mechanisms, this new pathway does not aim for complete pollutant degradation, but instead selectively activates both PMS and pollutants through catalyst surface-mediated electron transfer, forming active monomers that subsequently polymerize into macromolecular products on the catalyst surface (Fig. 4). DOTP exhibits three notable advantages: (1) low oxidant consumption; (2) strong resistance to interference from background water constituents; and (3) transformation of pollutants from 'removal' to 'resource fixation', advancing water treatment toward carbon sequestration-oriented sustainability[44,45]. It should be emphasized that this pathway shows minimal dependence on the catalyst surface area; its core lies in constructing efficient electron-transfer interfaces that stabilize reactive intermediates and promote surface polymerization. Nevertheless, key challenges persist in practical applications, particularly the lack of a clear understanding of the relationship between catalyst electronic structure and interfacial electron-transfer kinetics, as well as the difficulty in directing the reaction pathway toward polymerization instead of mineralization.

Figure 4.

The surface (heterogeneous nanocatalysts) functions (i.e., activation, stabilization, and accumulation) of DOTP and the comparison with AOP for water purification. Reprinted from Zhang et al.[43] with permission. Copyright © 2022 Nature.

To address these challenges, researchers have developed several strategies: (1) Electronic structure modulation. By introducing boron dopants to construct asymmetric Fe–N5 coordination and electron-rich carbon auxiliary sites, the d-band center was downshifted and long-range electron polarization channels were established, thereby redirecting bisphenol A degradation from radical mineralization to interfacial polymerization[46]. (2) Coordination microenvironment design. Asymmetric Co–N2O3 micropores engineered on Ti3C2Tx MXenes promoted the reduction of dissolved O2 to •O2−, which subsequently drove pollutant self-coupling reactions for polymerization-based removal[45]. (3) Multisite synergistic activation. High-entropy alloy (HEA) nanoparticles supported on N-doped carbon enabled multisite PMS activation, generating highly active PMS* complexes that guided phenolic compounds toward polymerization in a nonradical HEA–PMS system. This pathway significantly reduced oxidant consumption and achieved an exceptional electron utilization efficiency of 213.4%[47]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that through coordination engineering and electronic-structure regulation, it is possible to direct pollutant conversion toward controlled polymerization, providing a multifaceted route to advance water treatment technologies toward resource-efficient and low-carbon development.

-

PAA, an organic peroxyacid, has gained widespread application in wastewater treatment, the textile industry, and food processing owing to its high disinfection efficiency and low potential for generating toxic byproducts[48,49]. It has been recognized as a preferred disinfectant in wastewater treatment plants across Europe and the United States. In recent years, PAA has demonstrated remarkable advantages in AOPs due to its high redox potential (1.06–1.96 V vs NHE) and relatively low O–O bond energy (159 kJ mol–1). Compared with PMS (377 kJ mol–1) and H2O2 (213 kJ mol–1)[40,50], PAA can be more readily decomposed to yield a variety of reactive species, including •OH, organic radicals (e.g., CH3COOO•, CH3COO•), and 1O2. Among these, 1O2 has been identified as the ideal reactive species for selective pollutant degradation in PAA-AOPs, owing to its high oxidation selectivity and minimal interference from background constituents. Recent studies[51] have revealed that the directional adsorption of the terminal oxygen atom (ATO) in PAA serves as a key descriptor governing the generation of 1O2. Based on this understanding, defect engineering and related strategies have been employed to tailor the surface electronic structure of catalysts, facilitating ATO-dominated adsorption configurations, effectively reducing the activation barrier for 1O2 formation, and thereby enhancing the selectivity of nonradical oxidation pathways. Furthermore, the research focus of PAA-AOPs has gradually shifted from single-pathway activation to a cooperative mechanism involving both radical and nonradical processes. To address the intrinsic drawbacks of Fe-based catalysts—such as low valence cycling efficiency and limited electron-transfer capability—metal doping strategies have been applied to modulate the valence distribution of Fe species and accelerate their redox cycles[52]. This not only improves PAA adsorption and charge-transfer efficiency but also enables the simultaneous activation of radical and nonradical pathways. In addition, localized reductive microenvironments can be constructed through hydrodynamic vortex-induced piezoelectric polarization or nonmetal doping, which continuously regenerate active Fe2+ sites and sustain the steady generation of multiple reactive species[53]. Meanwhile, in magnetic porous biochar-based catalysts, sp2-hybridized carbon structures and carbonyl (C=O) groups have been identified as the principal active sites for the generation of 1O2 and organic radicals, respectively[54]. These findings provide both theoretical guidance and material design principles for the directional regulation of PAA activation systems.

-

Traditional oxidants suffer from inherent drawbacks in practical applications. Liquid peroxides, such as H2O2 and PAA pose risks in storage and transportation; ozone exhibits limited mass-transfer efficiency and is prone to rapid decomposition, while PS-based systems may lead to sulfate accumulation, which can subsequently cause water and soil acidification. In contrast, PI (IO4–), owing to its stable physicochemical properties and facile activation characteristics, has emerged as a promising oxidant in AOPs. Although PI possesses a high intrinsic redox potential (1.6 V vs NHE), its direct oxidation of organic pollutants is kinetically constrained, necessitating activation to generate a variety of reactive species for efficient degradation[55]. To overcome the limited activation efficiency of PI, several innovative strategies have been developed. For instance, Fe(III) systems chelated with nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) can effectively resolve the intrinsic contradiction in traditional Fe-based activation—namely, the rapid deactivation of Fe(II) and the low reactivity of Fe(III)/PI interactions[56]. Furthermore, MnxCo3-xO4 spinel catalysts with precisely modulated spin states have been shown to enhance electron-transfer capability, thereby markedly improving the activation performance of PI[57]. In addition, solar irradiation can activate PI to generate IO3• species with strong electron delocalization effects, enabling targeted attacks on key carbon sites within the quinone ring of 6PPD-quinone[58]. This process induces hydroxylation and ring-opening reactions, ultimately leading to molecular fragmentation and complete mineralization of pollutants. Collectively, these studies provide valuable insights into the design of efficient and controllable PI activation systems, highlighting their potential as sustainable alternatives in next-generation AOPs.

-

In this perspective, AOPs driven by diverse oxidants including, PS, PAA, and PI are discussed, with a particular focus on four representative mechanistic pathways in PS-based systems: radical oxidation; nonradical oxidation; electron transfer process; and polymerization. Corresponding strategies are proposed to address the key issues encountered in current studies. Looking ahead, under the guidance of 'carbon peaking' and 'carbon neutrality' strategies, the development of AOPs still face several critical challenges that require in-depth exploration in the following aspects.

(1) Data-driven catalyst design for next-generation AOPs

Traditionally, the selection of catalysts and oxidants in AOPs relies on iterative batch experiments, where optimal reaction conditions and catalytic performances are identified through extensive trial and error. However, such empirical approaches are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and economically inefficient. Future research should emphasize the intelligent design of catalysts that can maximize catalytic activity while minimizing resource consumption. Machine learning models based on global optimization strategies offer a promising solution by learning from both experimental and computational datasets to extract intrinsic patterns and correlations. Through this data-driven approach, the structure–activity relationships linking catalyst composition, oxidant category, and AOP reactivity can be accurately predicted, paving the way for rational and cost-effective catalyst development.

(2) Interactions among multiple types of pollutants

Most current studies emphasize the degradation or transformation behavior of single pollutants and the identification of reactive species. However, real wastewater typically contains diverse coexisting contaminants, whose synergistic or antagonistic effects may result in limited catalytic performance and ambiguous mechanisms compared with idealized laboratory systems. Therefore, future research should focus on elucidating the interaction mechanisms among multiple pollutants in complex aqueous environments and on developing precise in situ characterization and multidimensional analytical strategies to bridge the gap between model studies and real-world applications, thereby providing theoretical and practical support for the engineering implementation of AOPs.

(3) Scalability and stability of catalysts

Most high-performance catalysts are synthesized at the milligram scale with high cost and limited durability. Subsequent efforts should be directed toward developing scalable and cost-effective fabrication processes, while enhancing catalyst stability and longevity under realistic aquatic conditions.

(4) Environmental relevance and systematic evaluation

The environmental relevance of many studies remains largely confined to the discussion sections without solid experimental validation. Future work should incorporate targeted experimental designs to systematically assess environmental applicability, energy consumption, byproduct formation, and ecotoxicity, thereby ensuring a holistic evaluation of AOPs performance.

(5) Regulation of reactive oxygen species types and pollutant selectivity

Radicals, with their high redox potentials, preferentially attack electron-deficient pollutants, whereas nonradical species selectively oxidize electron-rich compounds through electrophilic pathways. Although several studies have attempted to manipulate radical and nonradical routes, systematic strategies for precisely controlling the type of reactive oxygen species generated—and achieving efficient matching with the electronic properties of target pollutants—are still lacking and should be prioritized in future investigations.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Maoxi Ran: draft manuscript preparation, formal analysis, conceptualization; Tingqi Gong: formal analysis; Zhenwu Tang: formal analysis, conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data used in this article are derived from public domain resources.

-

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22506157), and Research Funding for Central Universities of Southwest University (Grant No. SWU-KQ25013).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ran M, Gong T, Tang ZW. 2025. Removal of new contaminants from wastewater through advanced oxidation processes - a perspective. New Contaminants 1: e020 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0020

Removal of new contaminants from wastewater through advanced oxidation processes - a perspective

- Received: 29 October 2025

- Revised: 08 December 2025

- Accepted: 12 December 2025

- Published online: 31 December 2025

Abstract: Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have been widely applied to remove new contaminants in aquatic environments; however, a systematic understanding of the underlying removal mechanisms is still lacking. This perspective provides a brief review of AOPs based on persulfate (PS), peracetic acid (PAA), and periodate (PI), with a particular focus on PS-AOPs and the four principal reaction pathways involved in the degradation of new contaminants: radical oxidation (mainly by sulfate and hydroxyl radicals); nonradical oxidation (e.g., singlet oxygen and high-valent metal-oxo species); electron-transfer process; and polymerization. Through a critical analysis of representative case studies, this paper examines the challenges associated with each reaction pathway and discusses potential solutions. In the future, the complexity of real wastewater matrices demands that further research tackles two fundamental issues: first, how to precisely design highly efficient catalysts to achieve effective removal of new contaminants while remaining cost-effective for practical application; and second, how to effectively identify key mechanisms within intricate reaction systems and establish systematic strategies for targeted regulation. Breakthroughs in these two aspects will collectively advance the transition of AOPs from laboratory research to engineering applications.

-

Key words:

- Advanced oxidation processes /

- New contaminants /

- Persulfate /

- Peracetic acid /

- Periodate /

- Reaction pathway