-

The metabisulphite ion is a chemically reactive nucleophile that acts as an inhibitor of microbial development, food spoilage, color enhancement, enzymatic activities, and oxidative processes in biological systems[1−5]. It has a high probability of affecting the nutritive value of food by interacting with folic acid, thiamine, nicotinamide, and pyridoxal vitamins found in it, hence stimulating its degradation[6]. Baker et al.[7] reported that sulfite from the metabisulphite preservative in the 2,6-diisopropyl phenol (propofol) blend generates an oxidative medium when this blending is opened to air, leading to the dimerization and decolorization of the product, which was attributed to the swift development of the reactive sulfite radical. The study of the possible toxic effects of Na2S2O5 on human foreskin cells in vitro revealed that there was a reduction in cell viability on varying the concentration of the antioxidant and an increment in the reactive oxygen species levels in the treated cells. Indicative of significant exertion of toxic effects on human cells via several mechanistic routes such as atom transfer, electron transfer, atom and electron transfer, free radicals facilitated, and intermediates promoters' routes by the sodium metabisulphite[8].

Zohra et al.[9] documented the consequence of subchronic incorporation of Na2S2O5 on lipid peroxidation, protein, and enzymatic antioxidants in the gastric tissue and splenic Wister rat. It was observed that the subchronic intake of Na2S2O5 had a hostile consequence on the spleen and stomach by initiating oxidative impairment, leading to an acceleration in lipid peroxidation and an adjustment of enzymatic activity. The effect of a 28-amino acid acylated peptide esterified with octanoic acid on Ser 3 (Ghrelin) given to the Wister rat on sulfite initiated oxidative and apoptotic change in its intestinal mucosa, resulting in a notable decrease in intestinal total oxidant status. The sodium metabisulphite initiated a notable rise in the total oxidant status and number of apoptotic cells. The action of Ghrelin in the process reduced the number of apoptotic cells[10]. The influence of Na2S2O5 as an antioxidant in overwhelming the drug release change from aged polyox tablets was reported. It was observed that the presence of Na2S2O5 steadied the release of the drug from polyethylene oxide (PEO) matrices, and the absence of it caused a surge in drug release from polyox matrices when stored at 40 °C. Thus, the concentrations of Na2S2O5 investigated were able to restrain the structural alterations of polyox samples and steadied the drug release[11]. Because food additives are liable to initiate allergic reactions that implicate an immune mechanism, there is a need to have a detailed understanding of their redox behavior and mechanistic routes in a regulated medium.

In addition, a molybdenum framework with bismuth has been explored as a catalyst in the photo-degradation process of methylene blue dye (MBD), as convened by Alahmadi et al.[12]. The team asserted that the Bi-Mo nano-framework (Bi2O3/MoSe2) enhanced the MBD degradation more than the individual species (Bi2O3 and MoSe2) due to its improved surface area and crystallinity, which is characterized by smaller particle size.

The study of the effect of charged micelle generators on a reaction medium is key to understanding the realities of solvent effect on the rate of reactions. The micelle media are sustainable, recoverable, and have a direct drive on reaction rate, and they position surfactants as a more reliable medium than organic solvents might take part in the reaction by oxidizing or reducing themselves[13−15]. CTAB and SDS with cationic and anionic polar heads respectively, have demonstrated useful interaction/binding traits with substrates. Quantitatively, their influence on the reaction rate has been determined using Piszkiewicz's, Berezin's, and Pseudophase ion-exchange models. The models presume the distribution of the substrates over the whole bulk of the micelles[16−18]. However, Srivastava and coworkers[19] pointed out the non-supportive character of CTAB and SDS in the oxidation of acid-red-13 dye with peroxydisulphate and neutrality of triton X-100 on the catalysis of the dye degradation process was obvious. In the oxidation system of l-phenylalanine with chromic acid, triton X-100, and SDS facilitated the oxidation process, whereas CTAB dragged the reaction rate due to the charge state of the substrates at the slow step[20]. In the same vein, CTAB elevated the oxidation of l-phenylalanine with Fe(III)-cyano complex, which was attributed to hydrophilic supremacy[21]. In a system where opposite charge species dominate such as oxidation of l-leucine with Fe(III)-cyano complex, CTAB also adequately accelerated the process and SDS championed an opposite influence[22]. A similar observation was reported in the oxidation of L-glutamic acid with the complex[23]. On the other hand, The analogue of CTAB, cetylpyridinium chloride was employed to accelerate the oxidation of l-phenylalanine with Cu(III)-periodate complex and the impact was massive with four-fold increment in reaction rate compared to surfactant-free system[24]. The same analogue of CTAB replicated the influence on the oxidation of l-glutamic acid with Fe(III)-cyano complex and impediment was noticed at high concentrations of the surfactant due to ion saturation[25].

The impact of molybdenum, as a constituent of nitrogenase enzymes, on the oxidation of nitrogen to ammonium during nitrogen fixation in plants, and the alteration of ruminant animal skin color when it is in excess holds promise for a better understanding of its redox mechanistic route[26]. Hence, a need to have detailed information on the mechanistic pathway of their electron transfer reaction and quantitatively determine the micelle-substrates hydrophobic and hydrophilic effects.

-

Sigma Aldrich, Germany: syn-2-pyridinealdoxime (99% pure), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (99% pure), molybdenum(IV) oxide (99.9 % pure), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (99% pure) were used. Na2S2O5 (97% pure), HCl (37% pure), NH4Cl (99.5% pure), HCOONa (98% pure), SnCl2 (97% pure), K2Cr2O7 (99.5% pure), BaCl2 (99% pure), H2SO4 (98% pure), KSCN (98% pure), NaCl (99.9% pure), ethanol (95% pure), methanol (99.5% pure), acrylamide (98.5% pure), sodium ascorbate (98% pure), sodium nitroprusside (98% pure), and diethyl ether (99% pure) were purchased from Fisher Chemical (Nigeria).

Synthesis of molybdenum-oxime complex

-

The approach by Konidaris et al.[27] was engaged in the synthesis of the MOC and the synthetic detail is recorded in our previous work on the redox reaction of allylthiourea with MOC[18], and it was characterized with an FTIR Spectrometer (Model-8400S, Shimadzu), UV spectrometer (Cary 300 Series), and conductivity meter (HACH Sension5).

Rate measurement

-

The reactant's mole contribution was learned as described beforehand[28−30] using photo-titrimetric at a constant electrolyte concentration and temperature. The point of interpolation on the display of absorbance against mole proportionality signaled the reaction stoichiometry.

A 721 PEC Medical ultraviolet-spectrometer model was involved in the kinetic surveys by noting the drop in concentration using change in absorbance of the molybdenum-oxime complex following the pseudo-first-order protocol with [S2O52−] in a ten-fold multiple over the [MOC][31−38]. The adjustment in the salt concentration (μ), medium polarity (D), and the [H+] involvement in the oxidation was probed by varying one at a time while upholding the other parameters at a fixed amount[39−42]. The observed rate constant (kob) was assessed from the slope of the relationship between InA vs t [Eqn (1)], and the rate constant (k2) was secured from the segmentation of kob with [S2O52−] [Eqn (2)]. Discovery of free radicals was made possible by the inclusion of acrylamide solution (0.15 cm3) and methanol (5 cm3) in the reaction in progress[43−46].

$ \mathrm{InA=InA}_{ \mathrm{0}} \mathrm+ \mathit{k} _{ \mathit{ob} } \mathrm{t} $ (1) $ \mathit{k} _{ \mathit{2} } \mathrm= \mathit{k} _{ \mathit{ob} } \mathrm{/[S}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O}_{ \mathrm{5}}^{ \mathrm{2-}} \mathrm{]} $ (2) Micelle formation and kinetic model

-

Micelle formation was verified via the critical micelle concentration, CMC, of the surfactants, which was obtained by measuring the specific conductivities of various [surfactant] solutions. The conductivity meter was attuned using 0.02 molar sodium chloride. The interjection point in the conductivity-concentration graph was considered as the CMC[47,48]. Piszkiewicz’s model was explored following its scientific equation [Eqn (3)].

$ k_{ob} = \dfrac{{k}_{w}{K}_{D}+{k}_{m}{\left[D\right]}^{n}}{{K}_{D}+{\left[D\right]}^{n}} $ (3) Thus, KD is the detachment constant of the micelle back to its free components. kw and km are the reaction rate constants in the absence and presence of surfactant accordingly. n is the number of surfactant molecules (D) and kob is the pseudo-first-order rate constant. [D] is the surfactant concentration[14,49].

-

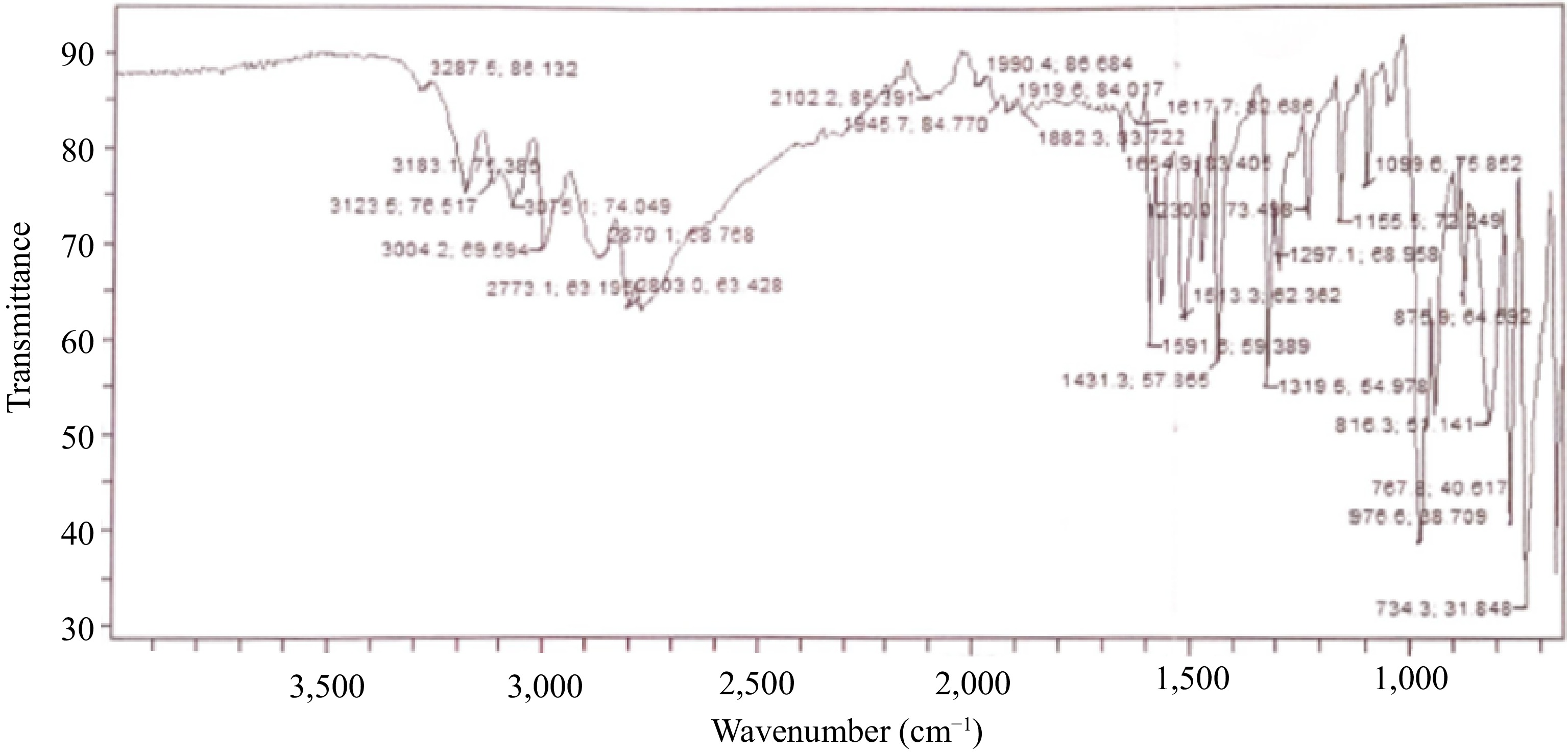

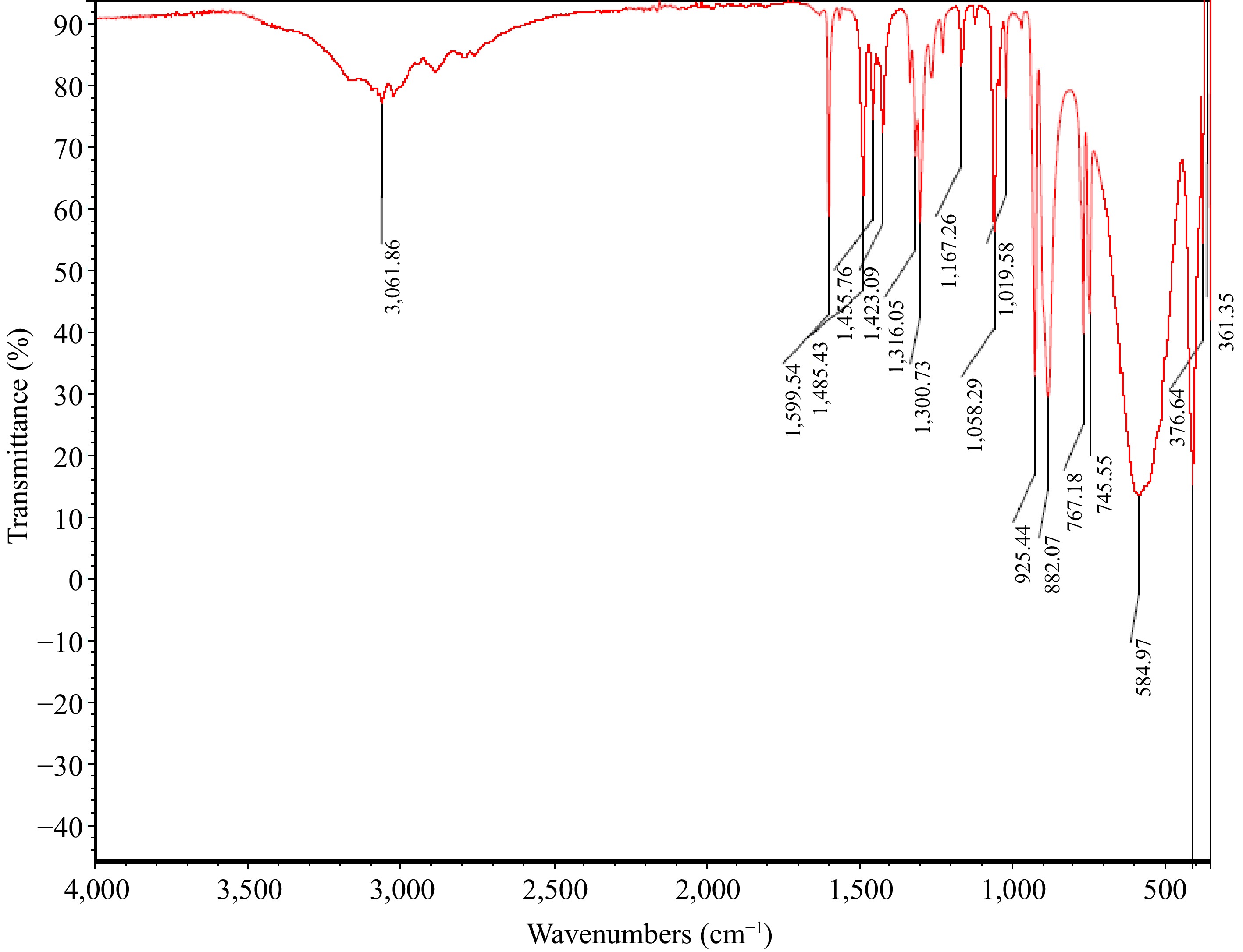

The UV/visible spectrophotometer of the MOC produced a maximum wavelength of 560 nm. The FTIR spectra of the oxime-ligand and the MOC are presented in Figs 1 and 2, respectively. The molecular vibrations of the MOC and ligand, and the conductivity measurement of the MOC are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Molecular vibrations of interest for the MOC and its molar conductivity.

Item Band (cm−1) Assignment Ligand 1,654.9 C=N (stretching) 1,591.8 N-O (bending) MOC 767.1 & 745.5 Mo=O (stretching) 584.7 Mo-N (stretching) 1,300.7 C-N (stretching) 1,599.5 N-O (bending) Molar conductivity 133 S·cm2·mol−1 The observed molar conductivity of 133 S cm2·mol−1 (Table 1), depicts the electrolytic nature of the MOC in solution[50−52].

The band observed at 3,075.1 cm−1 from the FTIR spectrum of the ligand (Fig. 1) is assigned to C-H stretching and 1,654.9 cm−1 band is assigned to C=N stretching, which shifted to 1,300.7 cm−1 in the MOC as a result of the C-N vibrational mode (Fig. 2). Indicative of complexation of the imine group with the central metal ion. The bands observed at 767.1 and 745.5 cm−1 in the spectrum of MOC are assigned to Mo=O stretching, indicating symmetrical and anti-symmetrical vibrations of MoO2 with a cis-MoO2 orientation, as a trans-MoO2 component would typically show one Mo=O band due to the asymmetry stretch, while that at 584.7 cm−1 is assigned to Mo-N stretching[53].

Stoichiometry

-

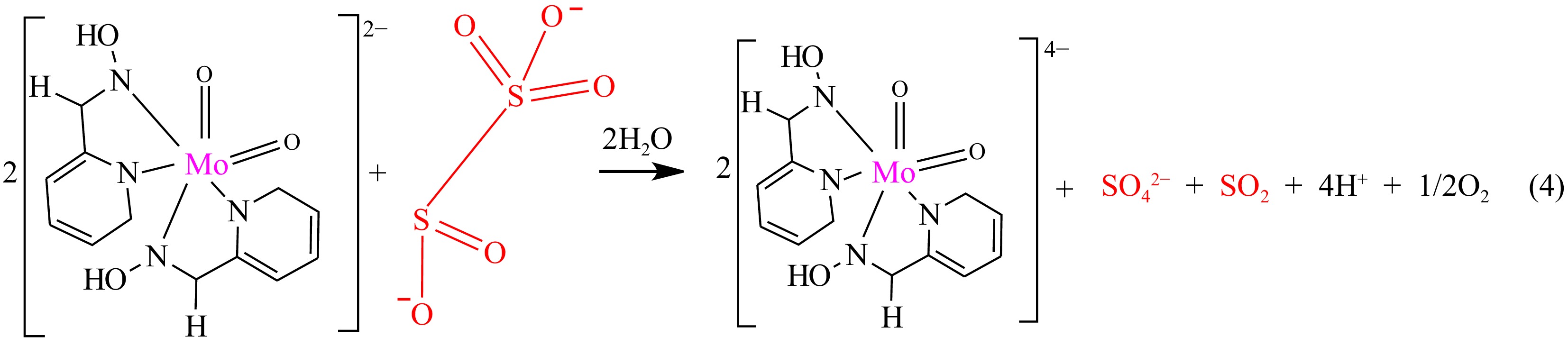

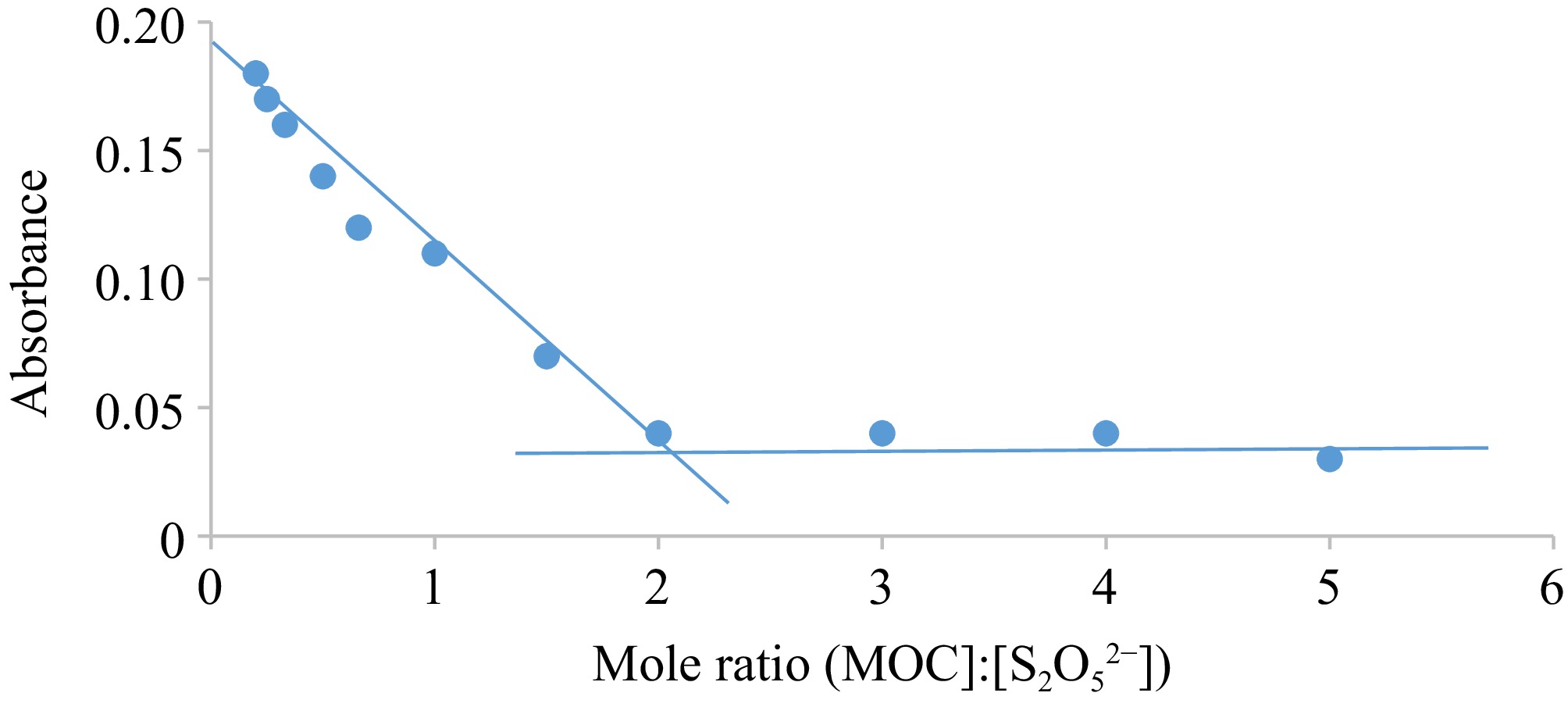

The resultant mole proportionality describes a two-electron contribution from a mole of the S2O52− ion to the 2 moles of the MOC (Eqn. (4) as shown in Fig. 3). The place of interjection in Fig. 4 establishes the number of moles implicated in the reaction.

Figure 4.

Graph of Abs vs mole ratio for the oxidation of S2O52− by MOC. Condition: [MOC] = 1.9 × 10−3 mol·dm−3, [S2O52−] = (0.4.18 – 95.0) × 10−4 mol·dm−3, [H+] = 0.02 mol·dm−3, T = 301 K, λmax = 560 nm.

The involvement of an unequal mole of the reactants results in the realization of SO42− ion, SO2, and Mo2+ products, which are confirmed classically. The appearance of an insoluble white precipitate on the addition of BaCl2 solution and in excess HCl confirms the presence of SO42− ion[54]. The change of the damp filter paper dipped in acidified potassium dichromate from orange to green indicates the presence of SO2[55]. The formation of a red color on the addition of three drops of KSCN solution (0.3 M) and two drops of acidified SnCl2 solution (0.14 M) infers the manifestation of the Mo2+ ion product [Eqn (4) shown in Fig. 3][56].

Kinetic investigations

-

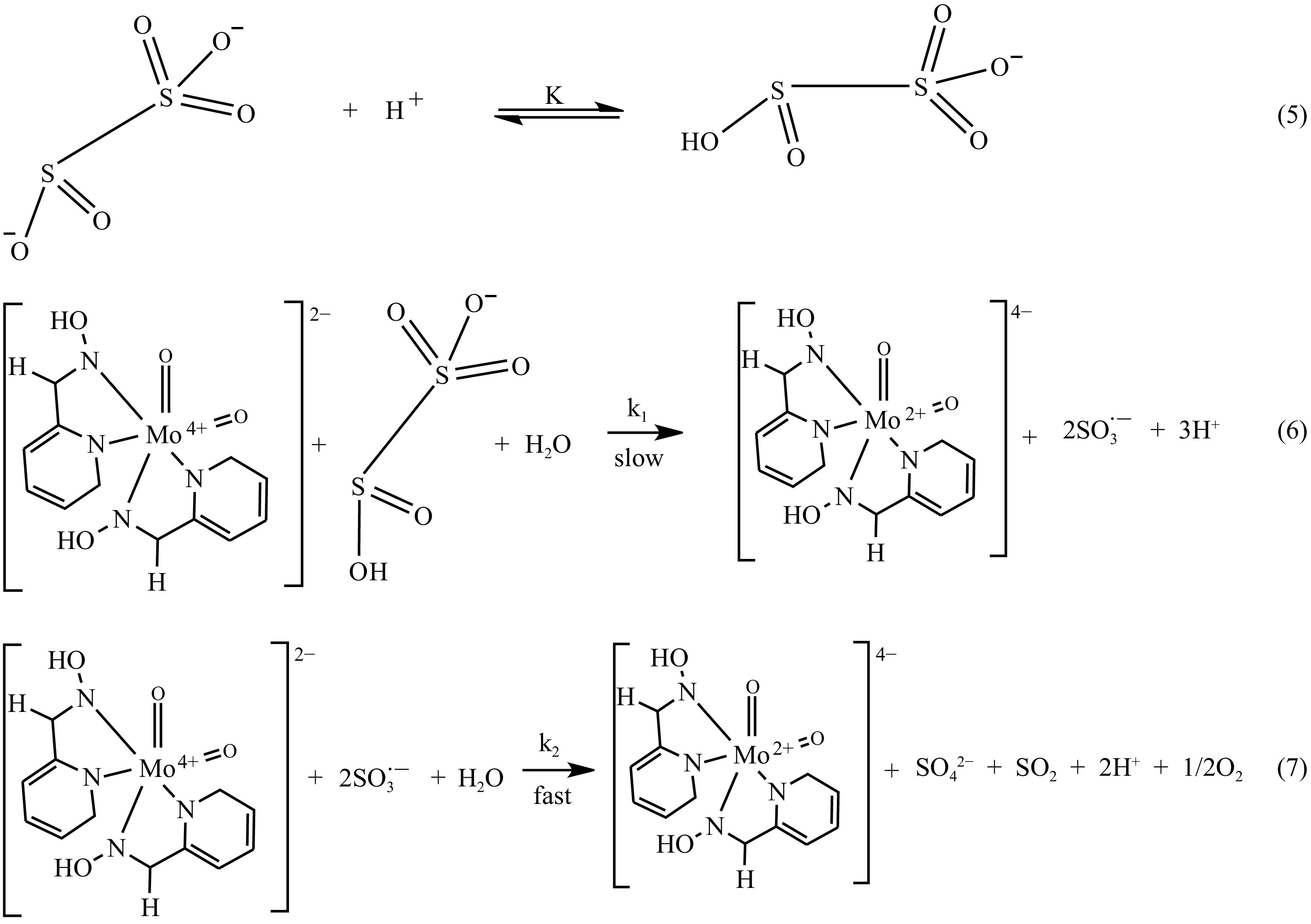

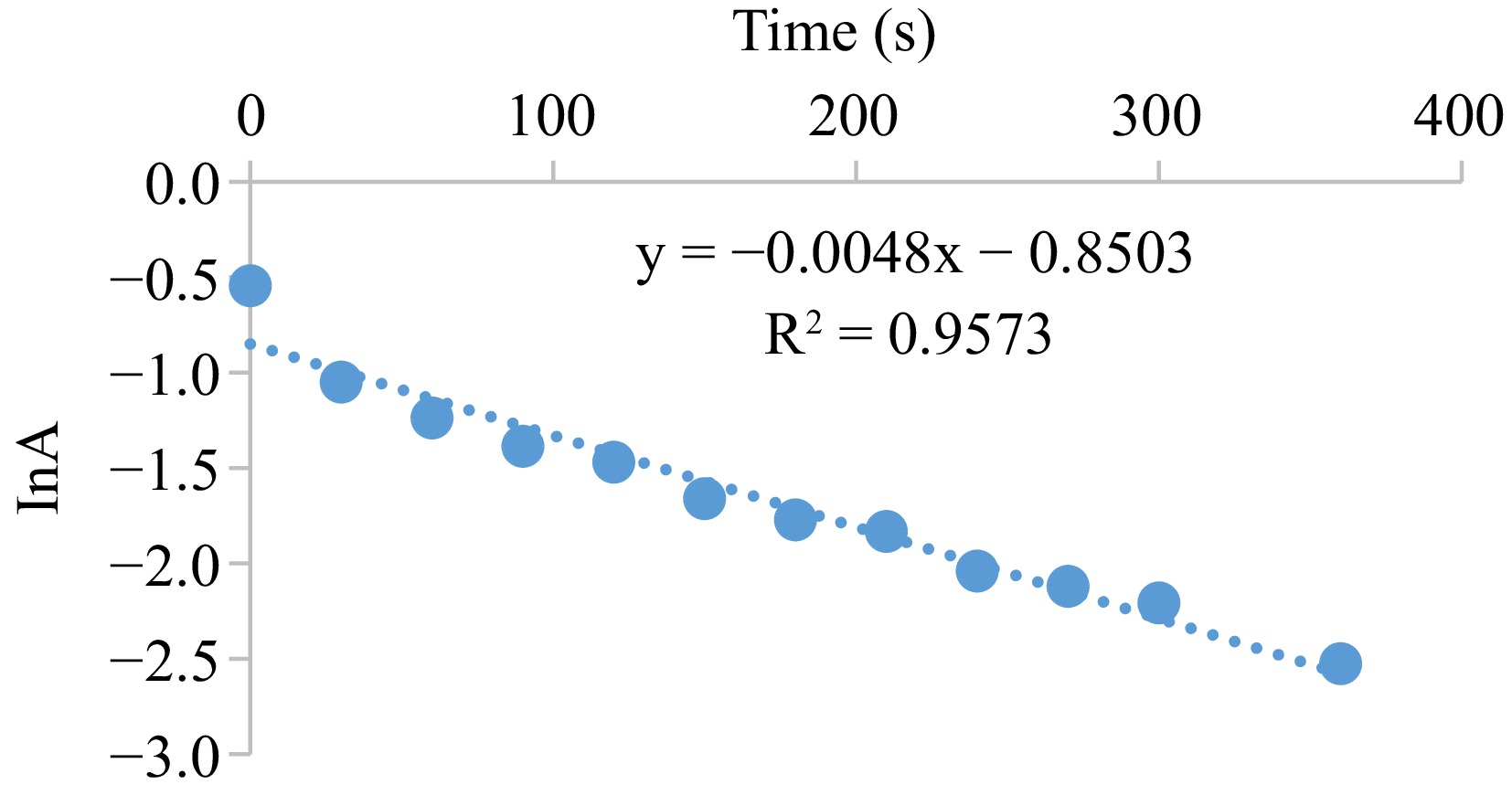

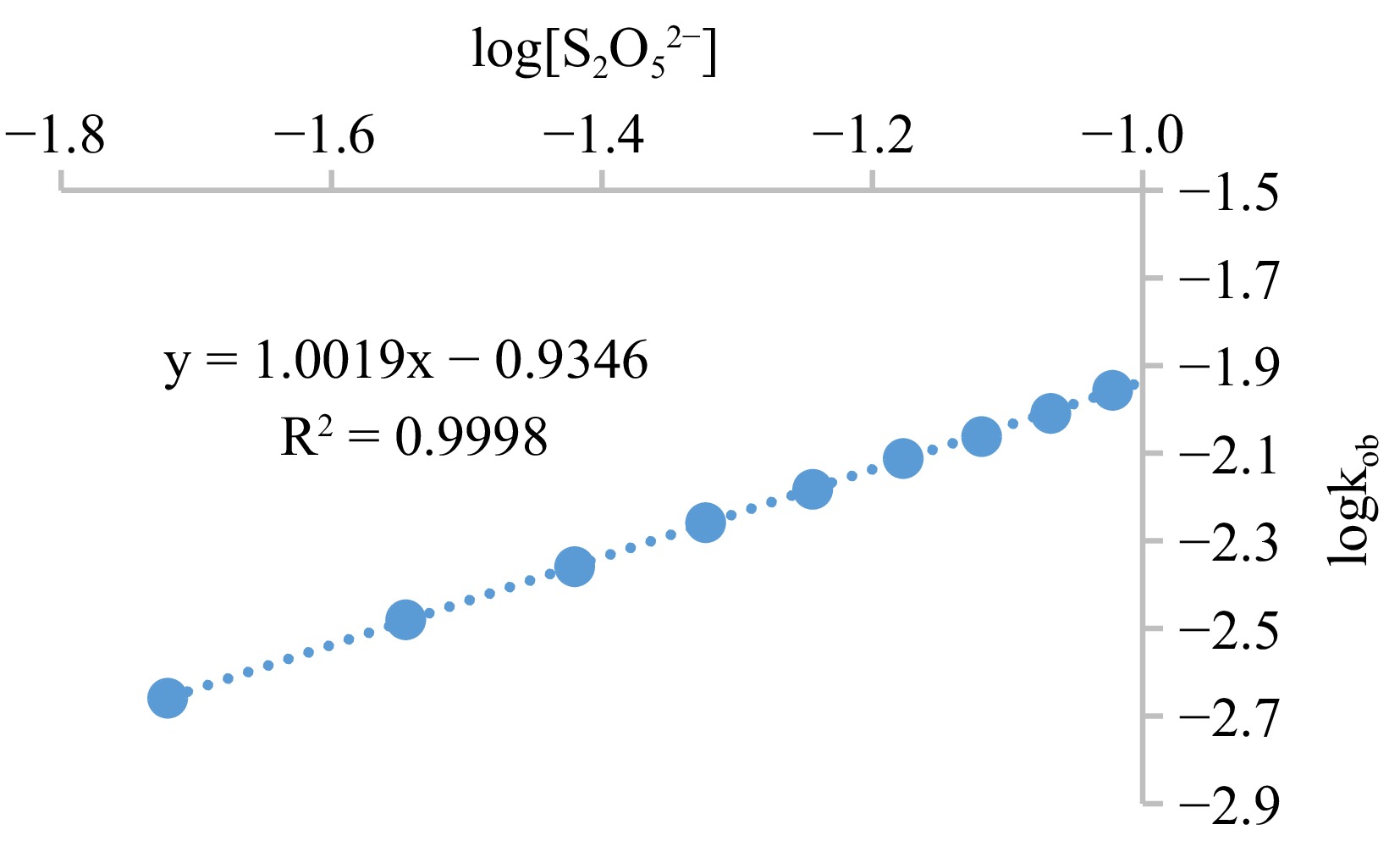

The probing of the observed rate constant, kob, through the graph that relates absorbance with time (Fig. 5), the output discloses a straight path that authenticates an oxidation with a single-order in the MOC concentration. The incline (1.0019) of the curve of log kob against log [S2O52−] (Fig. 6) also suggests a single-order in the [S2O52−]. Protonation of the S2O52− ion [Eqn (5) shhown in Fig. 11] is accommodated in the process, which necessitated an increase in the rate of the reduction-oxidation process as the [H+] is amplified (Table 2). The redox-rate is accelerated as the electrolyte concentration in the system is adjusted, originating from the collision of identical-charged species at the slow step [Eqn (6) shhown in Fig. 11], and this is reinforced by the deceleration of the oxidation speed on the change in the reaction system dielectric constant from 77.2–71.2 with ethanol (Table 3). There is a manifestation of the association of similar charged moieties at the slow step when the oxidation of S2O52− ion is catalyzed and inhibited by the inclusion of NH4+ and HCOO− ions, respectively (Table 4), standing as an indicator of an interaction involving an outer sphere mechanism. However, the generated sulfite radicals were essential in the formation of sulfur dioxide and reduction of the MOC [Eqn (7) shown in Fig. 11].

Figure 5.

Typical pseudo-first order plot for the oxidation of S2O52− by MOC. Condition: [MOC] = 1.9 × 10−3 mol·dm−3, [S2O52−] = 9.5 × 10−2 mol·dm−3, [H+] = 0.02 mol·dm−3, T = 301 K, λmax = 560 nm.

Figure 6.

Graph of logkob against log[S2O52−] for the oxidation of S2O52− by MOC. Condition: [MOC] = 1.9 × 10−3 mol·dm−3, [S2O52−] = (1.9 − 11.4) × 10−2 mol·dm−3, [H+] = 0.02 mol·dm−3, T = 301 K, λmax = 560 nm.

Table 2. Rate constants for the oxidation of S2O52− ion by MOC.

102[S2O52−] (mol·dm−3) 102[H+] (mol·dm−3 ) μ

(mol·dm−3 )103kob

(s−1 )102k2 (dm3·mol−1·s−1) 1.9 2.0 0.40 2.53 11.53 2.9 2.0 0.40 3.92 11.61 3.8 2.0 0.40 4.61 11.52 4.8 2.0 0.40 5.99 11.61 5.7 2.0 0.40 7.14 11.53 6.7 2.0 0.40 8.52 11.62 7.6 2.0 0.40 9.21 11.40 8.6 2.0 0.40 10.13 11.45 9.5 2.0 0.40 11.05 11.64 10.5 2.0 0.40 12.21 11.68 11.4 2.0 0.40 13.13 11.52 9.5 2.0 0.40 11.05 11.64 9.5 2.5 0.40 11.52 12.12 9.5 3.0 0.40 12.21 12.84 9.5 3.5 0.40 12.44 13.09 9.5 4.0 0.40 12.89 13.58 9.5 4.5 0.40 13.13 13.82 9.5 5.0 0.40 14.05 14.79 9.5 5.5 0.40 14.74 15.51 9.5 6.0 0.40 16.58 17.45 9.5 6.5 0.40 17.50 18.42 9.5 7.0 0.40 17.96 18.91 9.5 2.0 0.35 9.21 9.69 9.5 2.0 0.40 11.05 11.64 9.5 2.0 0.45 11.98 12.61 9.5 2.0 0.50 12.67 13.33 9.5 2.0 0.55 14.05 14.79 9.5 2.0 0.60 16.59 17.45 9.5 2.0 0.65 18.65 19.63 9.5 2.0 0.70 21.42 22.55 9.5 2.0 0.80 25.33 26.67 9.5 2.0 0.85 34.55 36.36 Condition: [MOC] = 1.9 × 10−3 mol·dm−3, [H+] = 0.02 mol·dm−3, T = 301 K, λmax = 560 nm. Table 3. Effect of medium polarity on the oxidation speed of S2O52− ion by MOC at λmax = 560 nm.

D 103kob (s−1) 102k2 (dm3·mol−1·s−1) 77.2 11.05 11.64 76.5 9.44 9.94 75.9 9.21 9.69 75.2 7.83 8.24 74.5 7.14 7.52 73.9 6.45 6.79 73.2 5.53 5.82 72.5 4.61 4.85 71.9 4.38 4.61 71.2 3.92 4.12 Condition: [MOC] = 1.9 × 10−3 mol·dm−3, [S2O52−] = 9.5 × 10−3 mol·dm−3, [H+] = 0.02 mol·dm−3, T = 301 K, λmax = 560 nm. Table 4. Effect of counter-ions on the oxidation speed of S2O52− ion by MOC at λmax = 560 nm.

Ion 103[Ion]

(mol·dm3)103kob

(s−1)102k2

(dm3·mol−1·s−1)NH4+ 0.00 11.05 11.64 8.00 12.21 12.85 12.0 12.46 13.43 16.0 12.89 13.58 20.0 13.36 14.06 24.0 14.05 14.79 28.0 11.95 15.76 HCOO− 0.00 11.05 11.64 8.00 9.90 10.42 12.0 8.06 8.42 16.0 7.37 7.76 20.0 5.76 6.06 24.0 5.07 5.33 28.0 4.38 4.61 Condition: [MOC] = 1.9 × 10−3 mol·dm3, [S2O52−] = 9.5 × 10−3 mol·dm−3, [H+] = 0.02 mol·dm−3, T = 301 K, λmax = 560 nm. Relatively, the metabisulphite oxidation with hexacyanoferrate(III), HCF, in buffer system convenes inverse [H+] impact on the rate constant with the generation of hydrogen sulfite and sulfite radicals that recombined to form dithionate ions in a fast mode. Oxidation was favored by high solvation of active ion species, which made the outer coordination of HCF a center for interaction and implicated an outer-sphere mechanism, as supported by a large entropy of activation (−205 J·K−1·mol−1)[57].

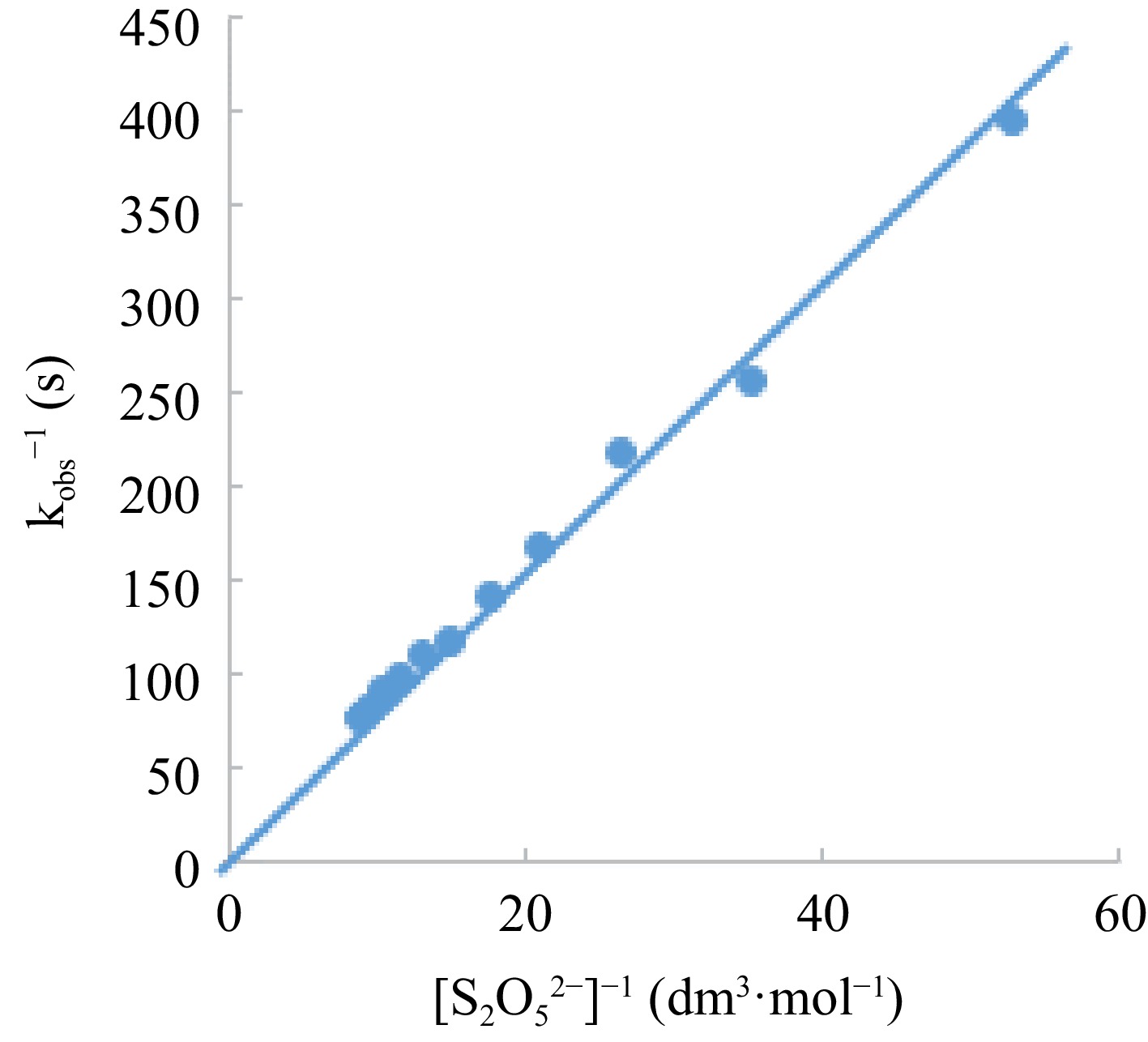

Kinetically, the intermediate formation is confirmed by using a Lineweaver-Burk plot, a modification of Michaelis-Menten plot (Fig. 7), where lack of intercept is an indication of non-availability of intermediate species and vice versa. Thus, the structural integrity of the complex remains intact due to the stability emanating from the crystal field stabilization energy, the metal ion, and the strong field ligand at an average temperature.

Figure 7.

Lineweaver-Burk plot of Michealis-Menten’s plot modification for intermediate determination.

Effect of micelle generators

-

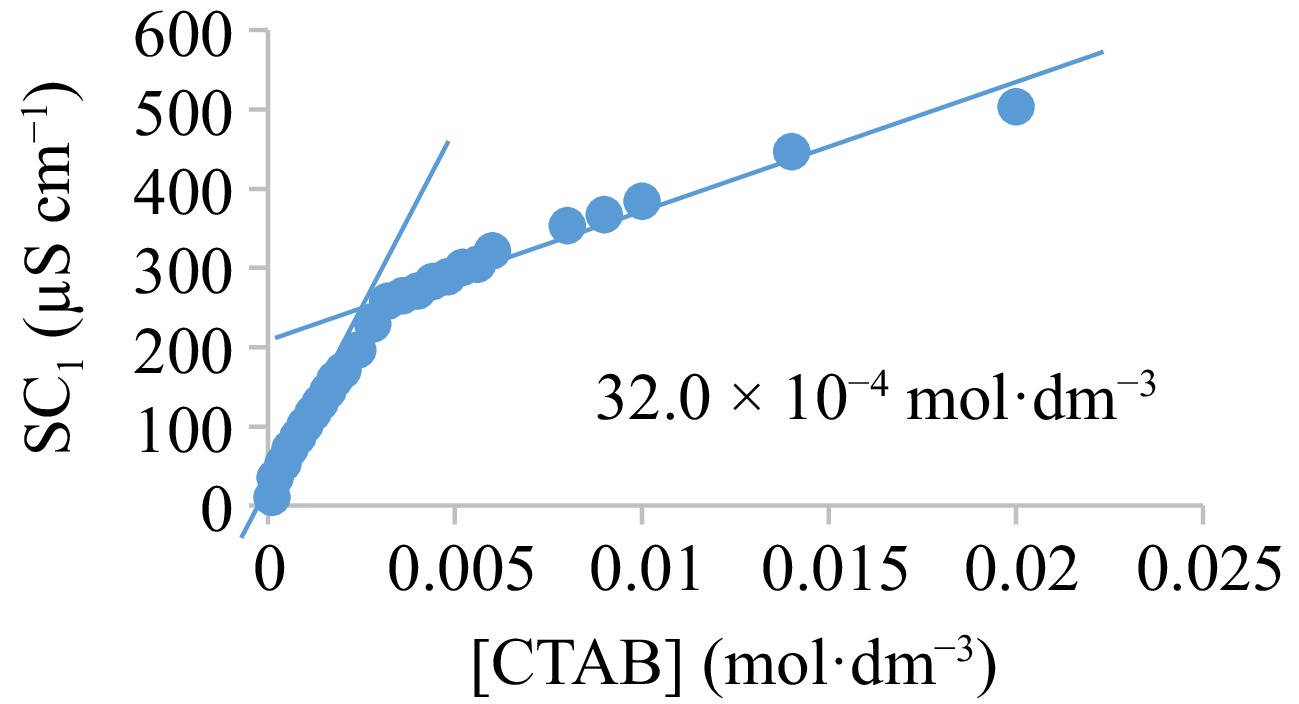

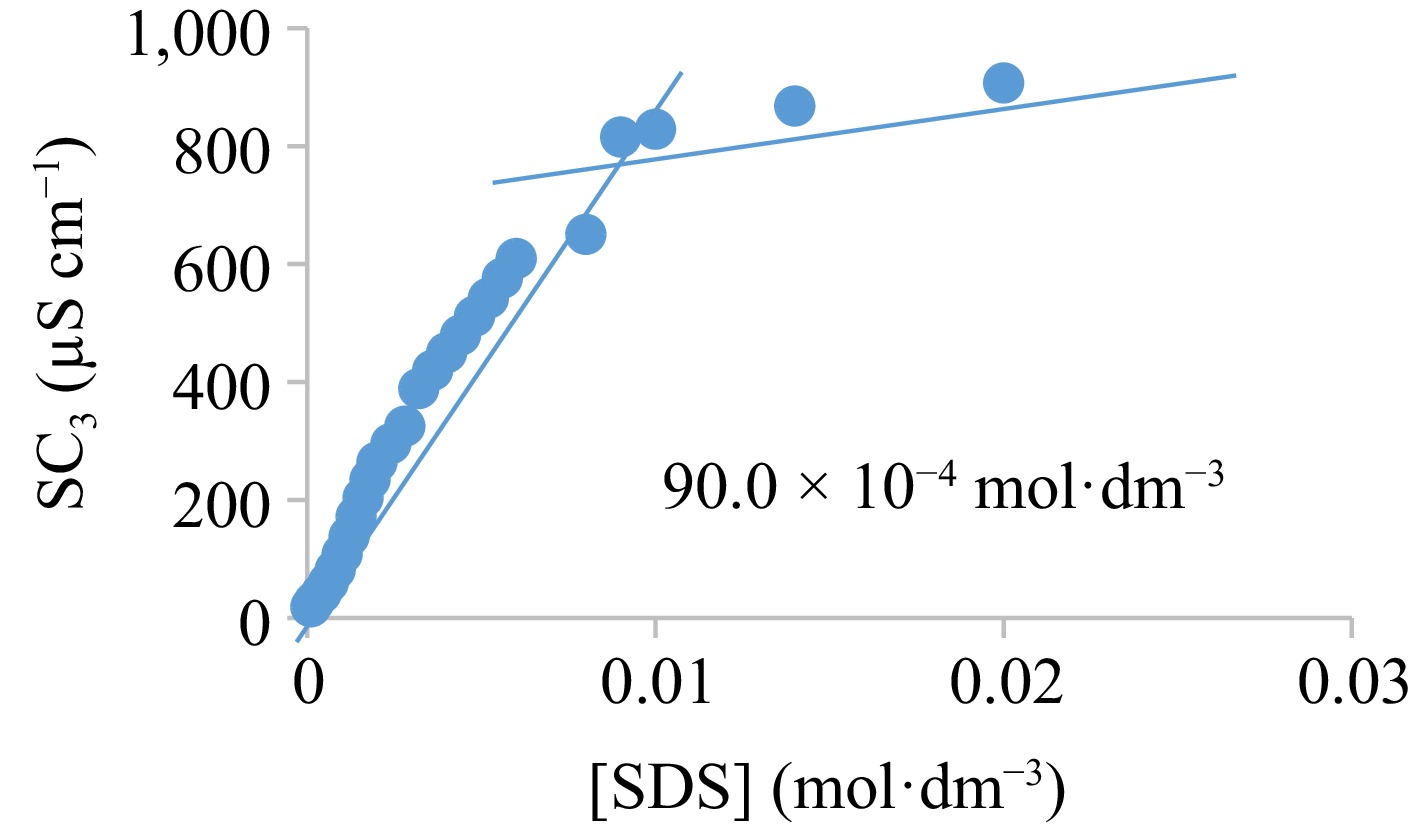

The CTAB and SDS micelles generation in H2O:ethanol mixture at 301 K is confirmed from the point of interjections (32.0 × 10−4 and 90.0 × 10−4 M, respectively) at the conductivity-concentration graphs (Figs 8 and 9), which depict the concentration at which surfactants aggregate to form micelles. Comparative investigation showed that in the presence of 0.1 M KNO3, CMCs of 4.0 × 10−3 and 7.0 × 10−4 M were reported for SDS and CTAB, respectively. The presence of salt concentration in surfactant solutions was attributed to the decline in the CMCs[58]. Wei et al.[59] reported CTAB CMC of 9 × 10−4 and 0.24 M in water and ethanol, respectively at ambient temperature. Thus, CMC decreases by shrinking the repulsive action between the charged-head groups of the surfactant monomers and it works against micelle formation, making micelles form at a reduced surface-active agent concentration[36].

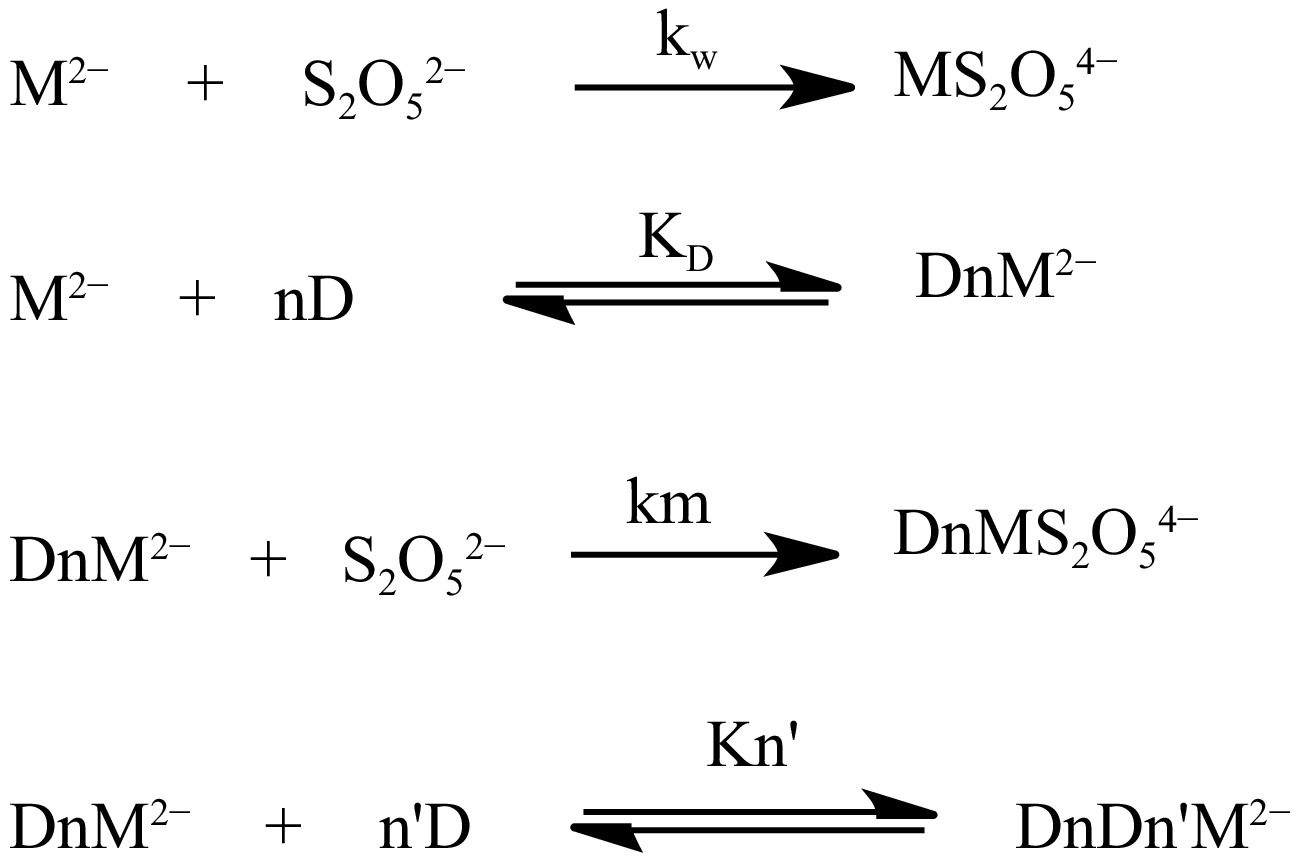

The influence of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide on the oxidation rate of the S2O52− ion by which the Piszkiewicz model is examined illuminates a substantial binding (KD−1) and cooperativity (n > 1) prevailing between the substrate and micelle, which results in an increased oxidation rate. This effect can be attributable to the associative mode that is assumed by the CTAB's polar head with the charged MOC on the Stern stratum of the CTAB aggregates, which is well-thought-out to possesses a great ionic concentration of the CTAB and reduced polarity. The catalytic micelle – substrate model of Piszkiewicz's concept based on enzymatic bimolecular oxidation of metabisulphite ion by MOC is presented in Fig. 10, wherein M2− is the MOC, Kn' is the association constant of the extra interactions, and n' is the extra number of CTAB monomers. The undeviating minimum-squares style is employed in estimating the factors of Eqn (3) (Table 5).

Table 5. Factors of Piszkiewicz kinetic model.

Micelle

generatorn KD KD−1 km

(dm3·mol−1·s−1)r2 kw

(dm3·mol−1·s−1)CTAB 1.4955 0.6114 1.6355 0.8623 0.9898 0.1164 SDS 2.2751 0.8367 1.1951 0.0155 0.9451 0.1164 Furthermore, the result of SDS on the oxidation speed of S2O52− ion expresses weak ionic and non-ionic collaborations between the SDS and the S2O52− - MOC at the Gouy-Chapman district of the micelle. This is perhaps connected to the association of similar charged moieties at the speed-limiting phase [Eqn (6) shown in Fig. 11], indicating that the S2O52− - MOC moieties associated inadequately with the SDS aggregates that occasioned an unfavorable collision between them. The control of the inhibitory effect above the catalytic action of SDS on the oxidation rate is strengthened by a lower associative constant (1.1951) of the micelle with the substrates compared to the associative constant (1.6355) of the CTAB micelle with the substrate. The stratum of this interaction can be assumed to be a district of lower ionic concentration and lower aggregate separation. Thus, CTAB and SDS increase and decrease the rate by 7-fold and 8-fold, respectively, compared to aqueous: ethanol medium and the result recommends that Piszkiewicz’s approach is pertinent in this redox route. The usage of the model gives substantial evaluation coefficients (r2) and the km is higher than the corresponding kw value, which marks the model as effective.

Owing to the above kinetic evidence, a mechanism without an intermediate is proposed [Eqns (5)−(7)] as offered in Fig. 11.

$ \rm{Rate\;law} = k_{{1}} {[MOC][HS}_{ {2}}{O}_{ {5}}^{-} ] $ (8) $ \rm{where \,[HS}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O}_{ \mathrm{5}}^{ \mathrm-} \mathrm{]=K[S}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O}_{ \mathrm{5}}^{ \mathrm{2-}} \mathrm{][H}^{ \mathrm+} \mathrm{]} $ (9) inserting Eqn (9) into (8);

$ \rm{Rate\;law} = Kk_{ \mathrm{1}} \mathrm{[H}^{ \mathrm+} \mathrm{][MOC][S}_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O}_{ \mathrm{5}}^{ \mathrm{2-}} \mathrm{]} $ (10) $ \rm{Rate\;law}=k[MOC][S_{ \mathrm{2}} \mathrm{O}_{ \mathrm{5}}^{ \mathrm{2-}} \mathrm{]} $ (11) where k = Kk1[H+] and the rate law support the first-order actualization in the redox moieties and a single acid-dependent route. The rate law derived from the mechanism underpins first-order kinetics with respect to [MOC] and [S2O52−] and proton assistant in the reaction, reinforcing the generated kinetic data.

-

The application of charged micelle generators on the oxidation of the metabisulphite ion by MOC uncovers a 2:1 stoichiometry and kinetics of first order in [S2O52−] and [MOC]. The realization of sulfur dioxide product is moved by the involvement of sulfite radicals. The variation of salt concentration within the system progression incited a positive kinetic-salt-effect that describes a redox reaction stemming from like-charged molecules at the speed-limiting level of the oxidation, and the fall in the system dielectric constant retarded the rate. The catalysis initiated by the counter-ion (NH4+) is possible due to the involvement of negatively-charged moieties at the slow phase. The Piszkiewicz quantitative data generated exposes the great role of cationic micelles in the reaction, with a compelling binding constant that credits the impact observed in the process. The overlap of redox groups with the CTAB and SDS micelles implicated electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions as uncovered by the observed cooperativity-index. Piszkiewicz’s model is appropriate in this study as it aids in informing the underlying forces of the reaction in a medium-dictated system.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Nkole IU, Idris SO, Abdulkadir I; data collection and analysis: Onu AD, Nkole IU, Idris SO; drafted manuscript preparation, critical manuscript revision (for important intellectual content): Nkole IU, Idris SO, Abdulkadir I, Onu AD. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data from the study are available on request from the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Nkole IU, Idris SO, Abdulkadir I, Onu AD. 2025. Application of charged micelle generators on the oxidation of metabisulphite ion by molybdenum-oxime complex: Piszkiewicz kinetic model. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e009 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0009

Application of charged micelle generators on the oxidation of metabisulphite ion by molybdenum-oxime complex: Piszkiewicz kinetic model

- Received: 10 February 2025

- Revised: 25 March 2025

- Accepted: 09 April 2025

- Published online: 15 May 2025

Abstract: The chemical characteristics of sulfur oxyanions as antioxidants is an interesting course worth probing, and understanding their mechanistic pathway is key. Hence, the application of charged micelle generators on the oxidation of the metabisulphite ion by the molybdenum-oxime complex (MOC) is suggested. Piszkiewicz's model is checked, and its dynamics are explored to offer explanations on the implication of the surfactants' involvement in the redox behavior of metabisulphite with the MOC. The reaction reveals a strong dependence of reaction rate on the positively charged micelles of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) compared to the negatively charged micelles of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) due to the high cooperativity order exhibited by the CTAB with the substrates, which are supported by a remarkable binding constant that exists between them within the Palisade-Stern layer region of the micelle. The inhibitory results exerted by SDS on the reaction rate infers a probable repulsion between it and the reactant at the head polar layer of the micelle. The influence of cationic (NH4+) and anionic (HCOO−) counter-ions on the oxidation rate supplements the role of the surfactant's interaction with the redox partners at the slow phase. The contribution of ion concentration to the oxidation rate depicts a reaction proceeding through a positive Brønsted salt effect, and the variation in the oxidation-environment polarity strengthened the outcome of the varied ion concentration on the oxidation rate, which is clarified better by Piszkiewicz’s model. Sulfur oxyanion radical was imperative in the reduction route of the coordinated MOC by the metabisulphite ion.

-

Key words:

- Metabisulphite ion /

- Kinetic model /

- Oxime complex /

- Micelle /

- Oxidation