-

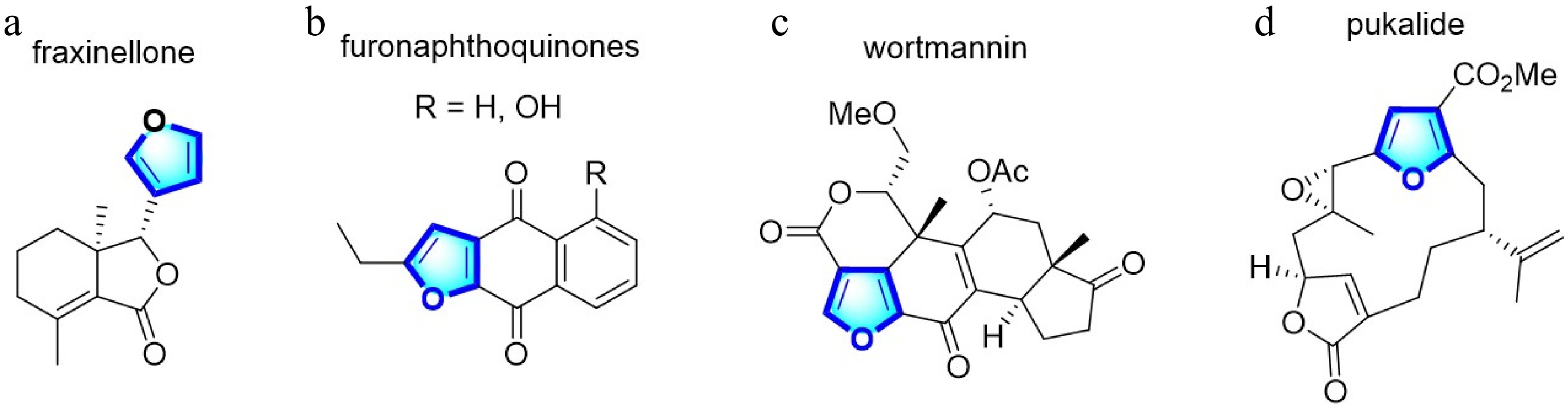

Furans are essential heterocyclic subunits extensively found as the synthetic building blocks of many natural products and are frequently detected in compounds of medicinal and agricultural interest[1]. For example, fraxinellone exhibits potential insecticidal activity[2], furonaphthoquinones show broad anticancer activities against human leukemia U937 and HL-60 cells[3], wortmannin is a highly selective inhibitor of phosphoinositide (PI) 3-kinases[4], and pukalide has emetic activity in fish (Fig. 1)[5]. Furans are an intriguing goal in organic synthesis. Many synthetic methods are proposed for preparing furan derivatives.

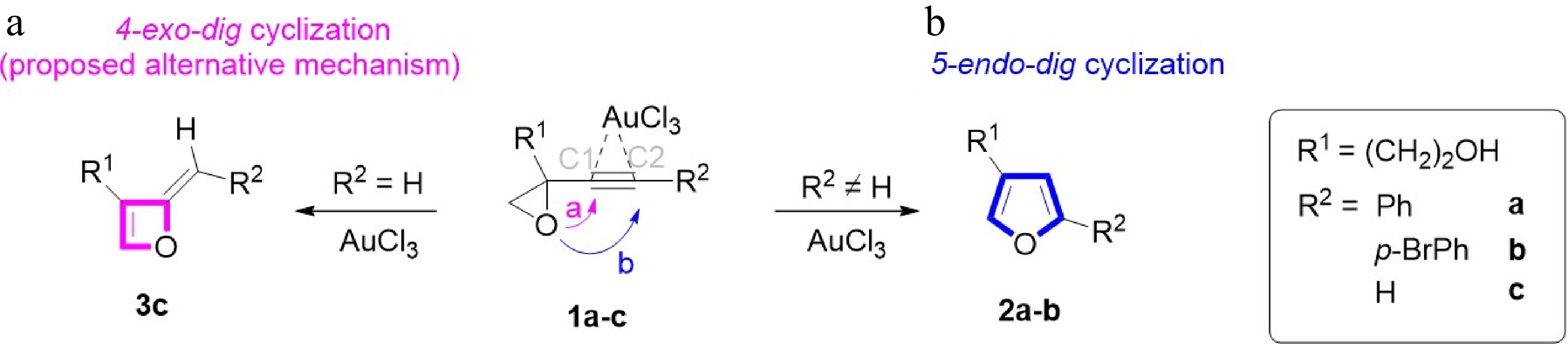

In this work, Hashmi's research group[6] designed furans experimentally, accompanied by a gold catalyst, as shown in Fig. 2. Hashmi et al. proposed a gold-catalyzed isomerization mechanism in their experimental study but did not explain it in detail. Firstly, 1,3-enynes synthesized from vinyl bromides and alkyne compounds via Sonogashira coupling, following epoxidation with m-CPBA (m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid), yielded the alkynyl oxirane derivatives 1[6]. Our prior studies show[7] that the regioselectivity of the product is affiliated with the R2 substituent. When an internal alkyne (R2 ≠ H, 2), the 5-endo-dig reaction takes place, but in the case of a terminal alkyne (R2 = H, 3), which Hashmi et al. did not study, the 4-exo-dig reaction may happen, as shown in Fig. 2.

Lately, we have determined a method of calculation to design oxazine and oxazepines[7]. Herein, we modeled and reported an experimentally proposed homogeneous gold-catalyzed isomerization mechanism to obtain furans from alkynyl epoxides. We also included the theoretical study of oxetene ring formation from alkynyl epoxide, accompanied by an AuCl3 (Fig. 2).

-

Calculations were conducted using Gaussian 09 (G09) software[8]. Density functional theory (DFT)[9−11] operations were carried out with the B3LYP[12] and M06-2X[13] functionals using the 6-31+g(d) and LANL2DZ[14]. Furthermore, in the theoretical experiments performed with LANL2TZ and LANL08[15] basis sets, calculation errors occurred due to the molecular deformation of the structures, and success was not achieved. Moreover, it was found that the CCSD(T)[16] functional was not suitable for this study. GaussView 6.0[17] was used to construct the compounds and to visualize and analyze the computational results obtained from Gaussian 09. The frequency calculations include exactly one virtual frequency for each optimized transition state (TS). The intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC)[18] method was selected to detect the energy minima of the reactants and products. Molecular images were created with CYLview software[19]. The polarizable continuum model (PCM)[20] using the integral equation formalism variant (IEF-PCM)[21] is the putative SCRF process in G09 was used as the solvent phase model, in which four solvents with different polarities (i.e., acetonitrile (ε = 37.5), methanol (ε = 32.7), acetone (ε = 20.7), and dichloromethane (ε = 8.9)) were chosen to compare with the research performed by Hashmi et al. This comparison was made to find the lowest energy barriers along the reaction coordinate and, thus, to determine the best solvent in which the high-yield reaction occurs. The solvent polarizations are implicitly taken into account in all figures. The M06-2X functional was used generally in the present study and compared to the B3LYP. Only a doublet state was considered in the electronic spin state of complexes.

-

Predicated on the research by Hashmi et al.[6], the catalyst AuCl3 was used to elucidate the formation of furans. The furans 2a-b with the five suggested TSs are formed via AuCl3-catalyzed isomerization of 1a-b (R1 = (CH2)2OH and R2 = Ph or p-BrPh) in acetonitrile, as shown in Scheme 1. The strained epoxide ring opens in TS1 after the gold catalyst coordinates with the alkyne. The oxygen of the alkoxide ion attacks the alkyne's C2 atom, resulting in ring closure in TS2, which is continued by proton movement in TS3, TS4, and TS5. Finally, the coordination of AuCl3 catalyst breaks in TS5 and thus forms furan derivatives 2a-b.

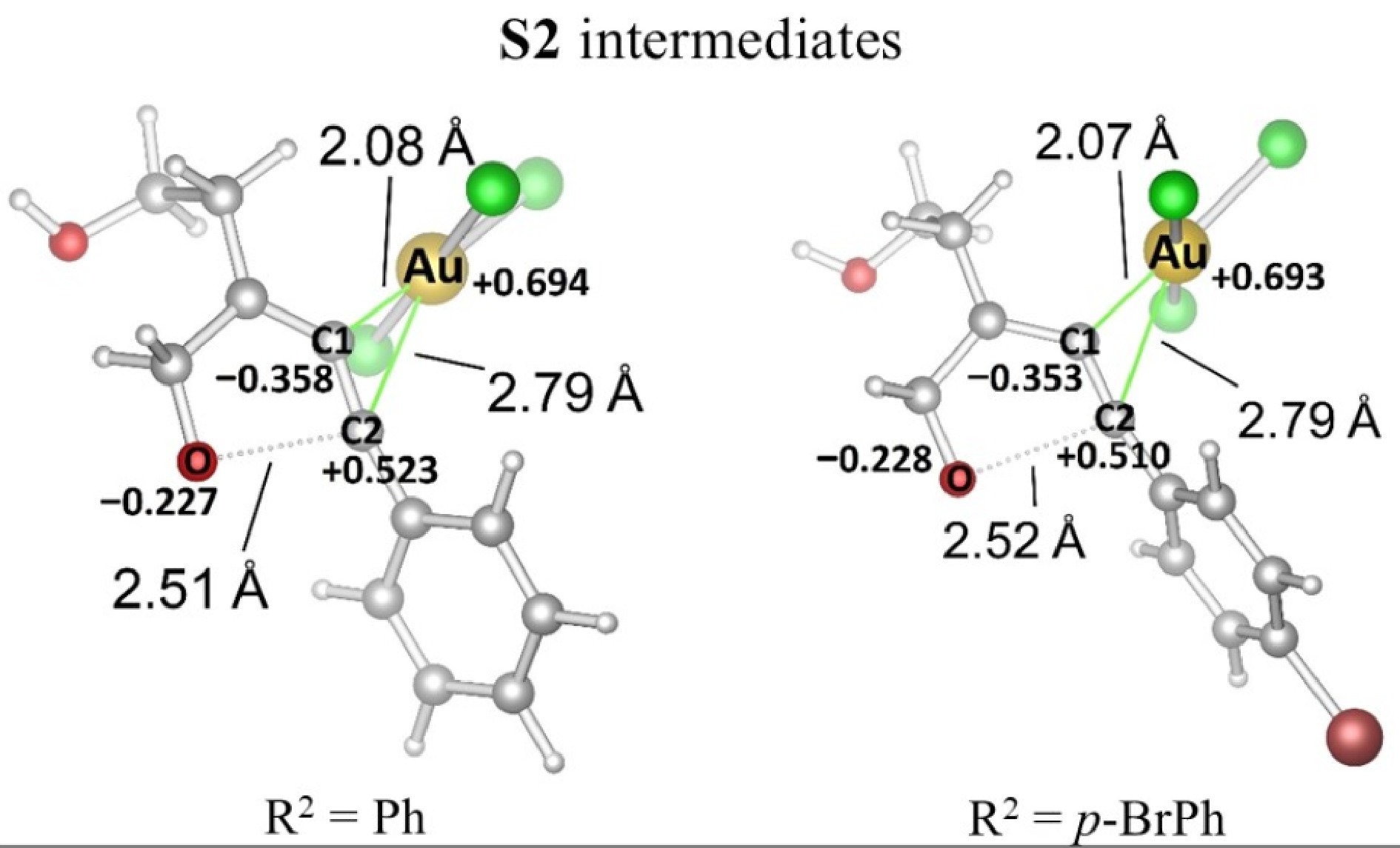

Natural population analysis (NPA)[22] was performed for intermediates in which the furan ring occurs (Fig. 3). As in the complex for R2 = Ph, the AuCl3 part is more proximate to the carbon C1 (2.08 Å) due to the negative charge (−0.358 au). However, since the positive charge is on the carbon C2 (+0.523 au), the distance to the gold unit increased (2.79 Å). The formation of the furan ring is triggered by the negatively charged (−0.227 au) oxygen atom and the positively charged carbon C2. The same tendency is also seen in the complex for R2 = p-BrPh. The AuCl3 part is close to the carbon C1 (2.07 Å) and far from the carbon C2 (2.79 Å), which have charges of −0.353 au and +0.510 au, respectively. It was determined that the bromine atom in the para position of the phenyl does not significantly affect the charge distribution because it is far from the alkyne group.

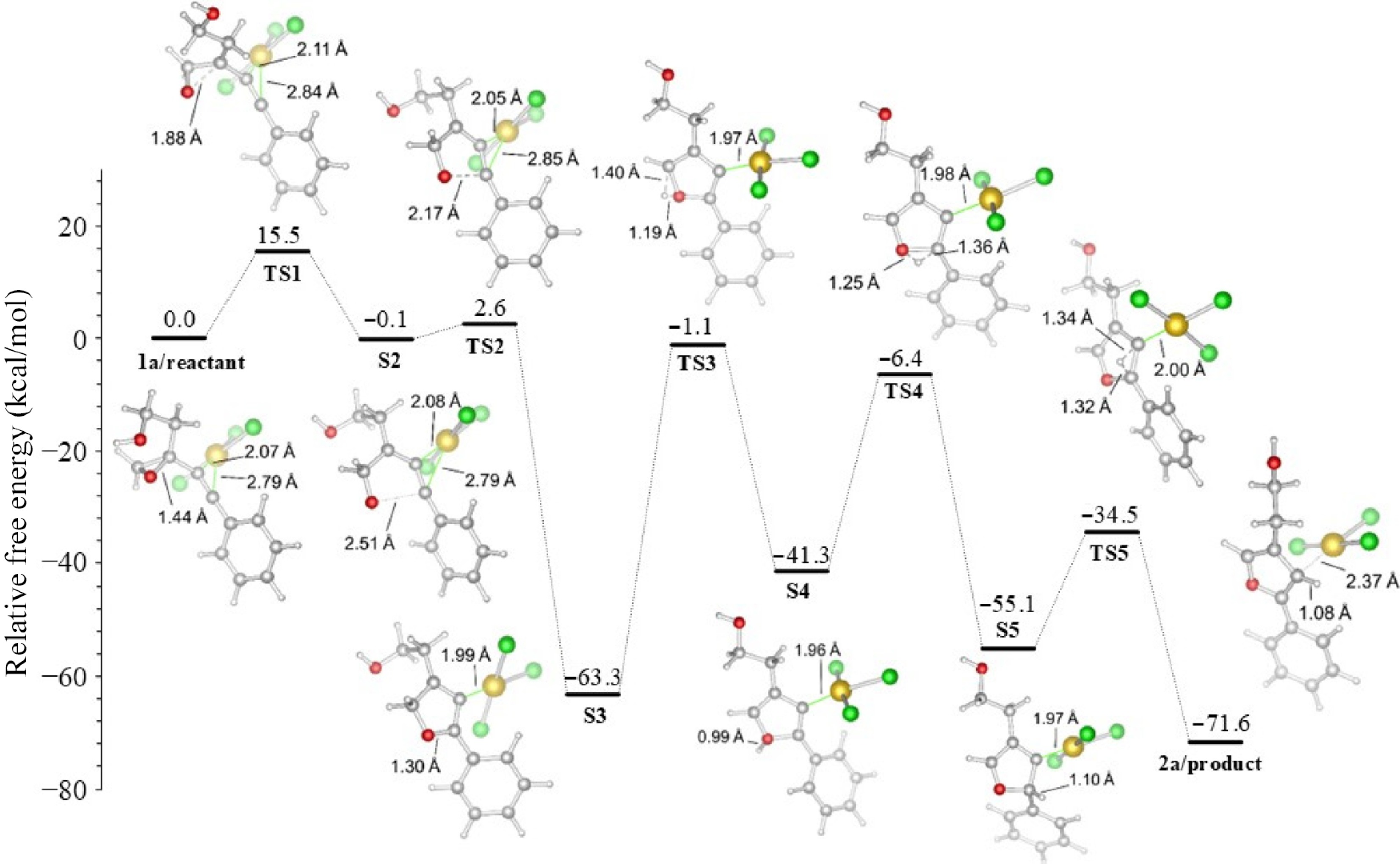

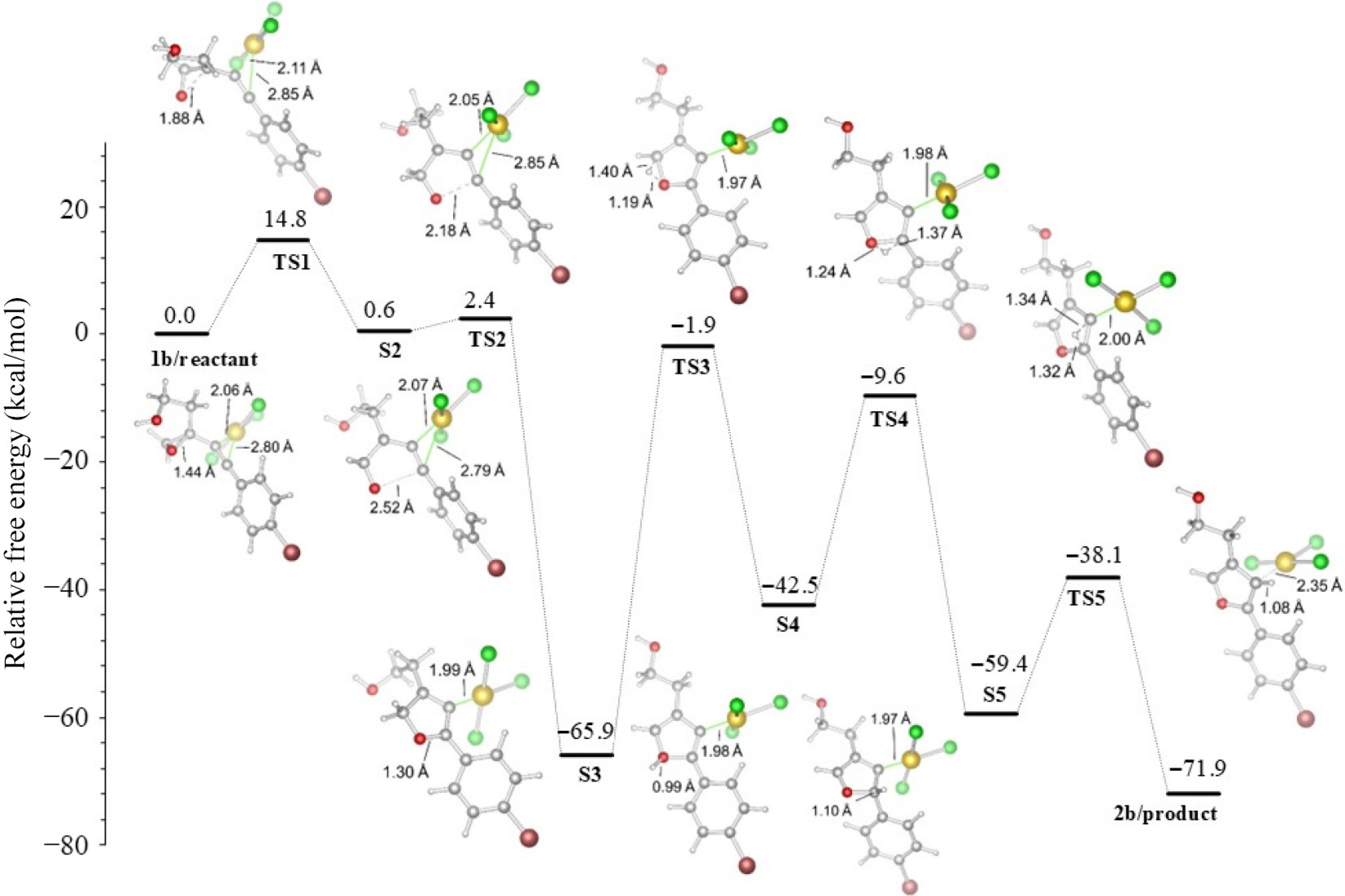

The energies of the furan-forming mechanisms are shown in Figs 4 and 5, and the values are collected in Table 1. Consistent with the experimental study, the R1 unit is kept constant as (CH2)2OH in these mechanisms, and only two derivatives, Ph or p-BrPh, are selected for the R2 position.

Table 1. Energies of reaction (in kcal/mol), (R1 = (CH2)2OH), with the M06-2X functional in acetonitrile.

R2 TS1 S2 TS2 S3 TS3 S4 TS4 S5 TS5 2a Ph 15.5 −0.1 2.6 −63.3 −1.1 −41.3 −6.4 −55.1 −34.5 −71.6 p−BrPh 14.8 0.6 2.4 −65.9 −1.9 −42.5 −9.6 −59.4 −38.1 −71.9 In the case of R2 = Ph, the gold part is consistently localized in TS1 on the negatively charged carbon C1 (2.11 Å). However, the positive charge exists on the carbon C2, and thus, due to positive charges pushing against each other, the distance [d(Au···C2)] extends to 2.84 Å. The strained three-membered epoxide ring opens at step TS1 and requires 15.5 kcal/mol free energy for this. In TS2, the negatively charged alcoholate oxygen atom makes a nucleophilic attack on the positively charged carbon C2 to present a five-membered furan ring with a small energy barrier of 2.7 kcal/mol, called reactant-like TS. During bond formation between O···C2 atoms, the distance [d(O···C2)] shortens from 2.51 to 1.30 Å. After the formation of the furan ring in TS2, the energy of the S3 intermediate product decreases to -63.3 kcal/mol. The stable structure of S3 can explain this decrease in energy, but the fact that the gold unit is still coordinated with the structure caused the mechanism to continue. In the following steps, TS3, TS4, and TS5, only proton transfer takes place, and they require energy barriers of 62.2, 34.9, and 20.6 kcal/mol, respectively. The highest barrier of free energy, 62.2 kcal/mol, was detected for TS3, which was the rate-limiting step of the reaction. This high-energy barrier is due to transferring one of the acidic character methylene protons. This transfer process begins with the movement of the proton to the oxygen atom in TS3. Then, the proton is transferred to the benzylic carbon atom in TS4. Finally, it passes to the carbon attached to the gold unit in TS5. It ends with separating AuCl3 from the structure and forming product 2a with an energy of −71.6 kcal/mol exergonically, as shown in Fig. 3.

No significant changes were observed in the R2 = p-BrPh case, as shown in Fig. 4. It was determined that the bromine atom in the para position of the aromatic ring did not contribute significantly to the cyclization process because that atom is far from the furan formation region. Furthermore, the charge distribution with and without the bromine atom on the C2 atom showed close values of +0.510 and +0.523 au, respectively (Fig. 3).

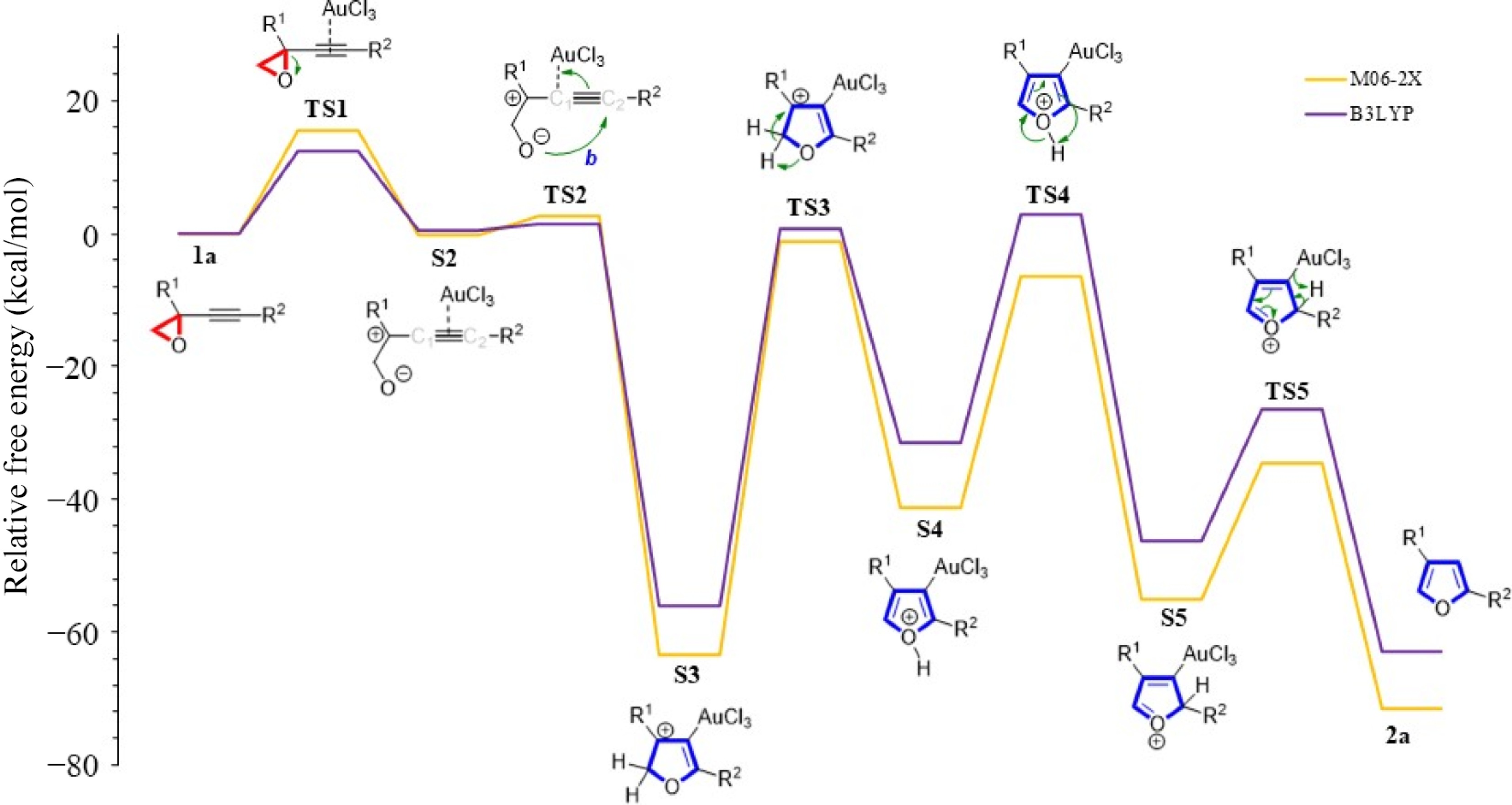

The M06-2X and B3LYP functionals were examined on furan formation using the 6-31+g(d) basis set (Fig. 6). The results, collected in Table 2, show that the energy barriers of the ring opening step (TS1) decreased by 15.5 and 12.5 kcal/mol, respectively. Both methods show a reactant-like TS step due to the geometric similarity. Of course, this will cause the energies to be close to each other, namely low energy barriers. The rate-limiting step for the M06-2X method is 62.2 kcal/mol and higher than that for the B3LYP method, which is 56.7 kcal/mol. Interestingly, this trend of energy between these methods continued in the following proton transfer steps of the mechanism. These energy values for the TS4 steps are 34.9 and 20.6 kcal/mol, and for the TS5 steps, 34.3 and 19.7 kcal/mol, respectively. Compared with the B3LYP method, compound 2a was calculated using the M06-2X method, which was obtained more exergonically with −71.6 kcal/mol.

Figure 6.

R2 = Ph and R1 = CH2CH2OH derived furan formation using various functionals in acetonitrile.

Table 2. Energies (in kcal/mol) with R2 = Ph and R1 = CH2CH2OH using B3LYP functional.

Method TS1 S2 TS2 S3 TS3 S4 TS4 S5 TS5 2a B3LYP 12.5 0.6 1.6 −56.0 0.7 −31.5 2.8 −46.2 −26.5 −63.1 Because the B3LYP method does not give accurate results for noncovalent interactions[23,24], and the M06-2X functional is parameterized for nonmetals[13], it was questioned which method would be used to continue working. In our calculations with M06-2X, we noticed that finding the TSs was easier than B3LYP, so M06-2X was utilized as the primary method. For example, when the TS2 step, which plays an essential role in the furan ring formation, is examined, the imaginary frequency of TS2 obtained with the M06-2X calculation method was found to be −191.87, while it was −55.90 in the calculation made with B3LYP (see Supplementary File 1).

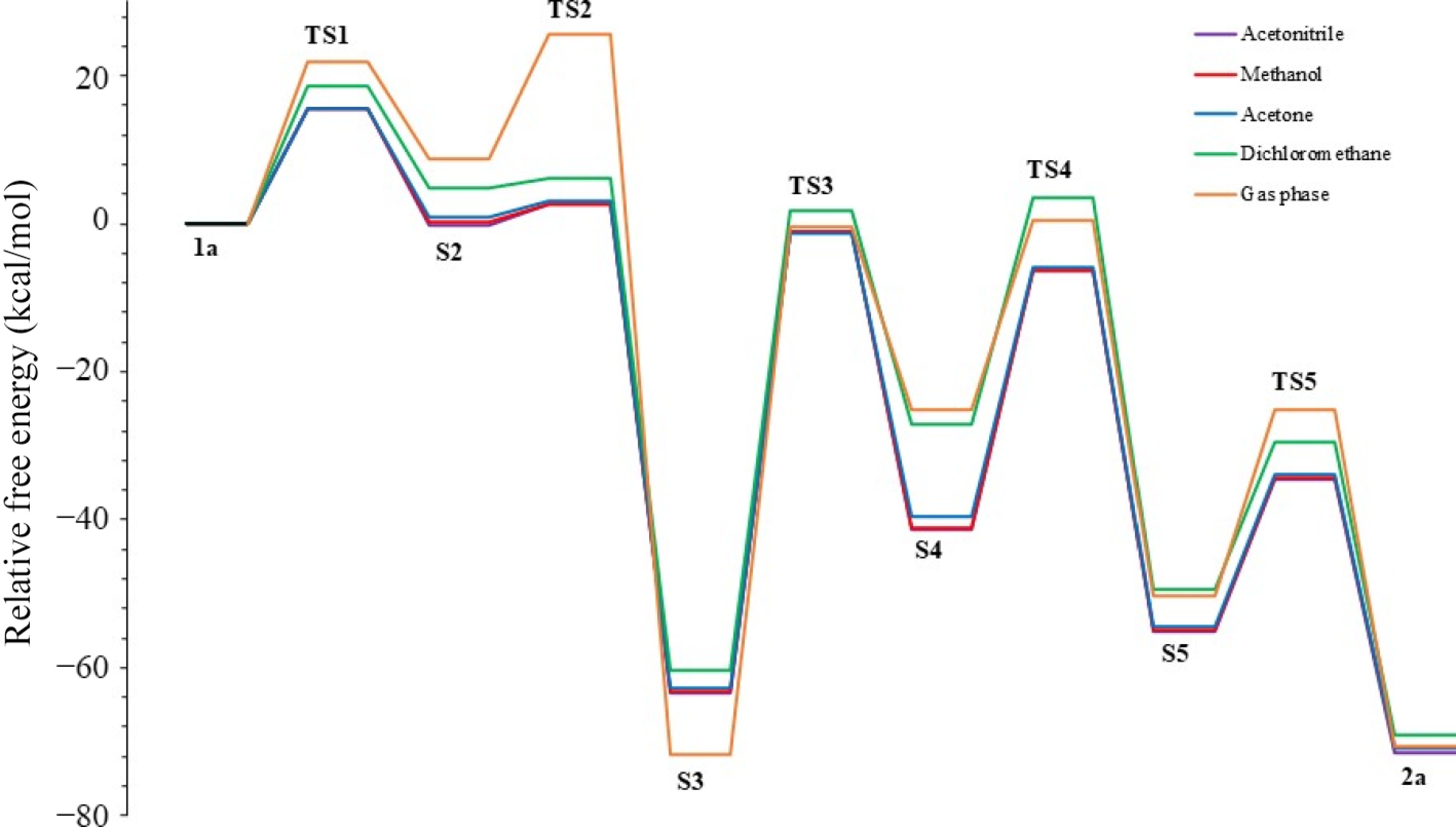

In the following part of the study, mechanism steps occurring in four solvents with different polarities were computed, and the energies were determined (Fig. 7) and collected in Table 3. The influence of solvents was analyzed using the M06-2X method. The default solvation model was chosen for the calculations made in the solvent phase. The energy barriers of furan formation in TS2 followed a course directly proportional to the dielectric constant, showing values of 2.7, 2.4, 2.0, and 1.4 kcal/mol, respectively. The rate-limiting step in all calculated solvents is the TS3 step, with a value of approximately 62.0 kcal/mol. Interestingly, in the calculations conducted with high polar acetonitrile and methanol, the energy values obtained were very close to each other, and the energy difference in some steps remained below 1.0 kcal/mol. This result shows that there will be no change in the energy barriers of the reaction in highly polar solvents. However, as the solvent's polarity decreases, such as with acetone and dichloromethane, the separations in the energy barriers along the reaction coordinate increase. Hashmi et al.[6] performed experimental work using high-polarity acetonitrile. Theoretically, the lowest relative free energy for compound 2a was obtained in acetonitrile with −71.6 kcal/mol. This theoretical result showed that the experimentally selected acetonitrile was probably the correct choice. Nevertheless, it is also possible that methanol can be used in experimental studies instead of acetonitrile.

Table 3. Energies of reaction steps (in kcal/mol) with R2 = Ph and R1 = CH2CH2OH substituents in various solvents.

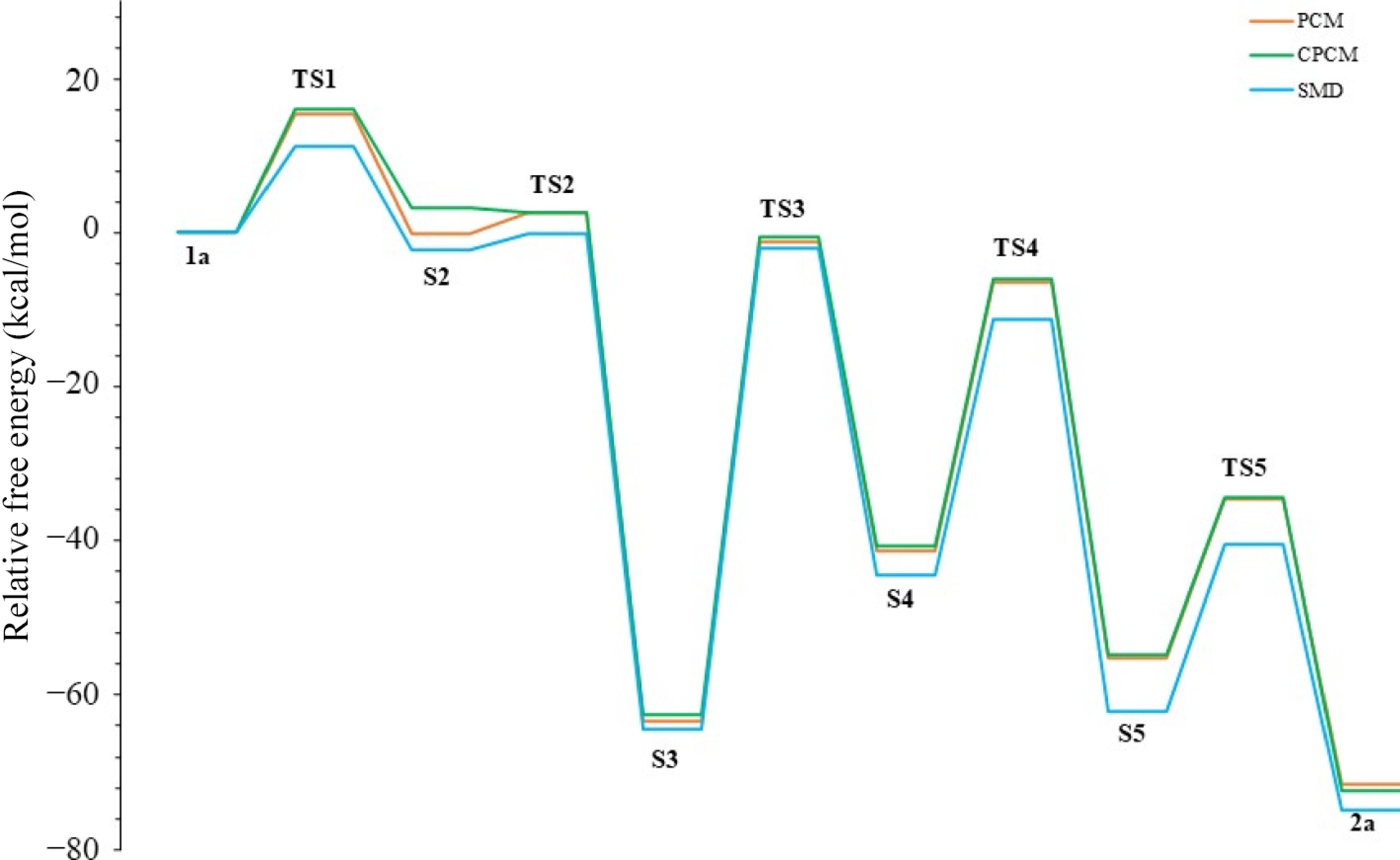

Solvent ε TS1 S2 TS2 S3 TS3 S4 TS4 S5 TS5 2a Acetonitrile 37.5 15.5 −0.1 2.6 −63.3 −1.1 −41.3 −6.4 −55.1 −34.5 −71.6 Methanol 32.7 15.6 0.3 2.7 −63.3 −1.1 −41.2 −6.3 −55.0 −34.0 −71.0 Acetone 20.7 15.5 1.0 3.0 −62.8 −1.3 −39.6 −5.8 −54.5 −33.9 −70.9 Dichloromethane 8.9 18.6 4.8 6.2 −60.3 1.7 −27.0 3.5 −49.4 −29.5 −69.1 Gas phase 0 22.0 8.7 25.6 −71.7 −0.4 −25.2 0.4 −50.3 −25.1 −70.7 Furthermore, we decided to calculate the transition mechanism of alkynyl epoxides to furans using different solvent models such as SMD[21] and C-PCM[25]. Our main goal was to determine the thermodynamic effect of the solvent model change on the mechanism (Fig. 8) collected in Table 4. However, when the energy barriers of the models were carefully examined, no significant change was observed. Only the energy barrier of TS2 calculated in the C-PCM model was relatively low compared to the others, i.e., −0.6 kcal/mol. Interestingly, the energy of S2 was slightly lower than that of TS2, and this was due to the S2 intermediate geometry being very similar to that of TS2 (S2 like TS2).

Table 4. Energies of reaction steps (in kcal/mol) (R2 = Ph and R1 = CH2CH2OH) in acetonitrile and various solvation models.

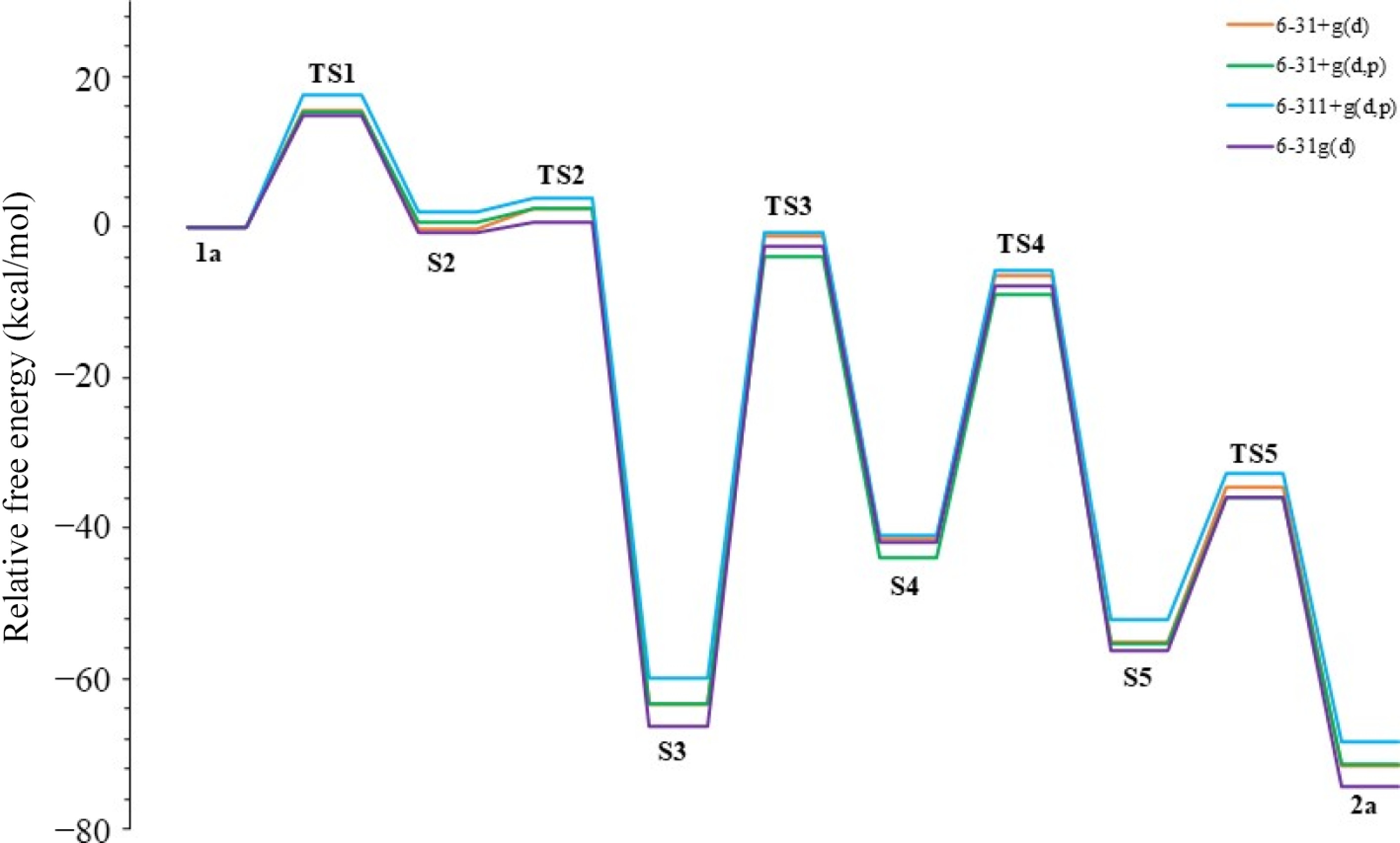

Solvation model TS1 S2 TS2 S3 TS3 S4 TS4 S5 TS5 2a PCM 15.5 −0.1 2.6 −63.3 −1.1 −41.3 −6.4 −55.1 −34.5 −71.6 C-PCM 16.0 3.3 2.7 −62.6 −0.6 −40.6 −6.1 −54.7 −34.4 −72.5 SMD 11.3 −2.2 −0.1 −64.4 −2.0 −44.5 −11.2 −62.1 −40.5 −75.0 We were also interested in testing the reaction mechanism with different basis sets of DFT using the M06-2X level in acetonitrile; therefore, the computed energy profiles and the results along the reaction coordinate using four basis sets such as 6-31+g(d), 6-31+g(d,p), 6-311+g(d,p), and 6-31g(d) are collected in Table 5 and shown in Fig. 9. In the calculations conducted with the 6-31+g(d,p) basis set, which includes the p-polarization function, lower energy barriers were obtained compared to the 6-31+g(d) basis set without a polarization function. However, no significant change was observed between the 6-31+g(d,p) basis set and the 6-311+g(d,p) results. There was only an energy difference of 2.3 kcal/mol between the barriers of TS1. Moreover, in the calculations with the 6-31g(d) basis set used to eliminate the diffusion function effect, the highest TS3 barrier energy reached was 63.9 kcal/mol. TS3 was also the rate-limiting step of the reaction for all basis sets. According to the results of the 6-31+g(d,p) and 6-311+g(d,p) basis sets, where diffusion and polarization functions were used, the TS3 energy barriers decreased by 59.3 and 59.1 kcal/mol, respectively. This determination for the TS3 step showed that it would be more appropriate to use diffusion and polarization functions in calculating the alkynyl epoxides to furan mechanism. However, a basis set should not be chosen only based on the TS3 step. In general, all basis sets gave similar results. In this context, due to the ionic character of the intermediates, only the diffusion function was added, and the 6-31+g(d) basis set was generally chosen for the present work. Furthermore, Table 6 summarizes the basis sets' computational costs (CPU time). Accordingly, the lowest-cost basis set is 6-31g(d), and the highest-cost is 6-311+g(d,p). Although this result makes the 6-31g(d) basis set advantageous over 6-31+g(d), it was not preferred in the rest of the study because 6-31g(d) does not contain a diffusion function.

Table 5. Energies of reaction steps (in kcal/mol) using various basis sets in acetonitrile.

Basis set TS1 S2 TS2 S3 TS3 S4 TS4 S5 TS5 2a 6-31+g(d) 15.5 −0.1 2.6 −63.3 −1.1 −41.3 −6.4 −55.1 −34.5 −71.6 6-31+g(d,p) 15.2 0.7 2.4 −63.2 −3.9 −43.9 −8.9 −55.4 −35.8 −71.3 6-311+g(d,p) 17.5 2.0 4.0 −59.8 −0.7 −40.9 −5.8 −52.2 −32.7 −68.3 6-31g(d) 14.9 −0.6 0.6 −66.3 −2.4 −41.8 −7.7 −56.3 −35.9 −74.2 Table 6. The computational cost (CPU time) for each basis set.

Basis set Job CPU time TS1 S2 TS2 S3 TS3 S4 TS4 S5 TS5 2a 6-31+g(d) 0 d 23 h

38 min 40.8 s1 d 3 h

55 min 22.9 s1 d 3 h

28 min 33.5 s1 d 4 h

0 min 53.6 s1 d 6 h

12 min 33.0 s1 d 8 h

7 min 2.3 s0 d 14 h

36 min 50.0 s0 d 16 h

58 min 7.2 s0 d 16 h

34 min 4.6 s0 d 15 h

54 min 57.4 s6-31+g(d,p) 1 d 6 h

6 min 9.9 s1 d 12 h

5 min 10.6 s1 d 13 h

50 min 18.4 s1 d 10 h

23 min 31.2 s1 d 14 h

7 min 27.6 s1 d 13 h

45 min 27.4 s1 d 1 h

46 min 46.4 s0 d 17 h

17 min 24.7 s0 d 18 h

51 min 57.7 s0 d 18 h

33 min 27.2 s6-311+g(d,p) 1 d 0 h

48 min 59.0 s1 d 2 h

3 min 56.9 s1 d 2 h

37 min 44.5 s1 d 5 h

23 min 41.2 s1 d 2 h

46 min 16.9 s1 d 5 h

12 min 7.6 s1 d 6 h

10 min 27.9 s1 d 5 h

27 min 23.0 s1 d 8 h

10 min 44.4 s1 d 2 h

55 min 8.0 s6-31g(d) 0 d 3 h

12 min 54.9 s0 d 3 h

12 min 50.8 s0 d 3 h

17 min 53.9 s0 d 3 h

22 min 20.4 s0 d 3 h

18 min 26.8 s0 d 3 h

13 min 54.5 s0 d 3 h

18 min 24.1 s0 d 3 h

23 min 56.9 s0 d 3 h

26 min 13.0 s0 d 3 h

22 min 26.0 sAuCl3-catalyzed formation mechanism for obtaining oxetene from alkynyl epoxides

-

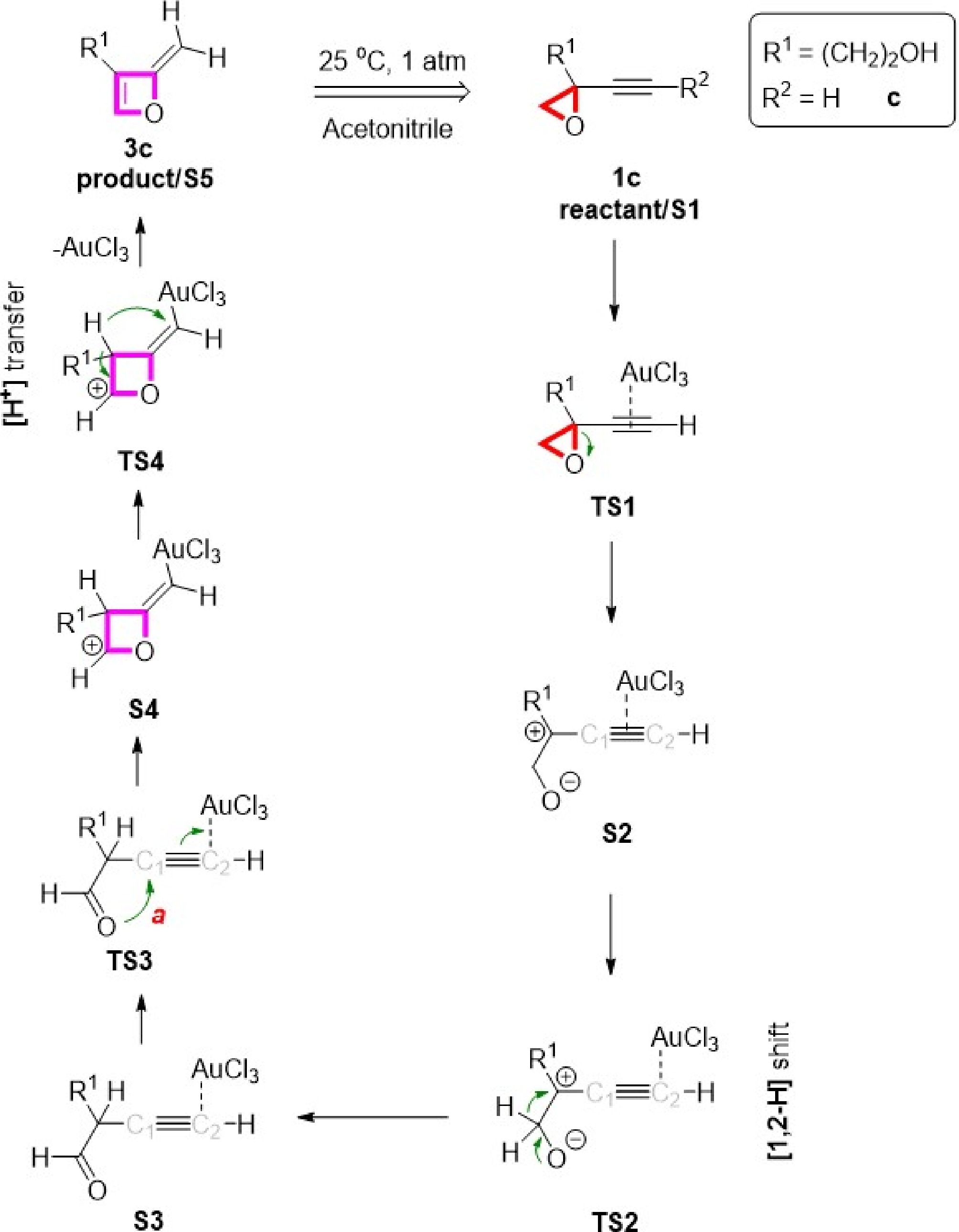

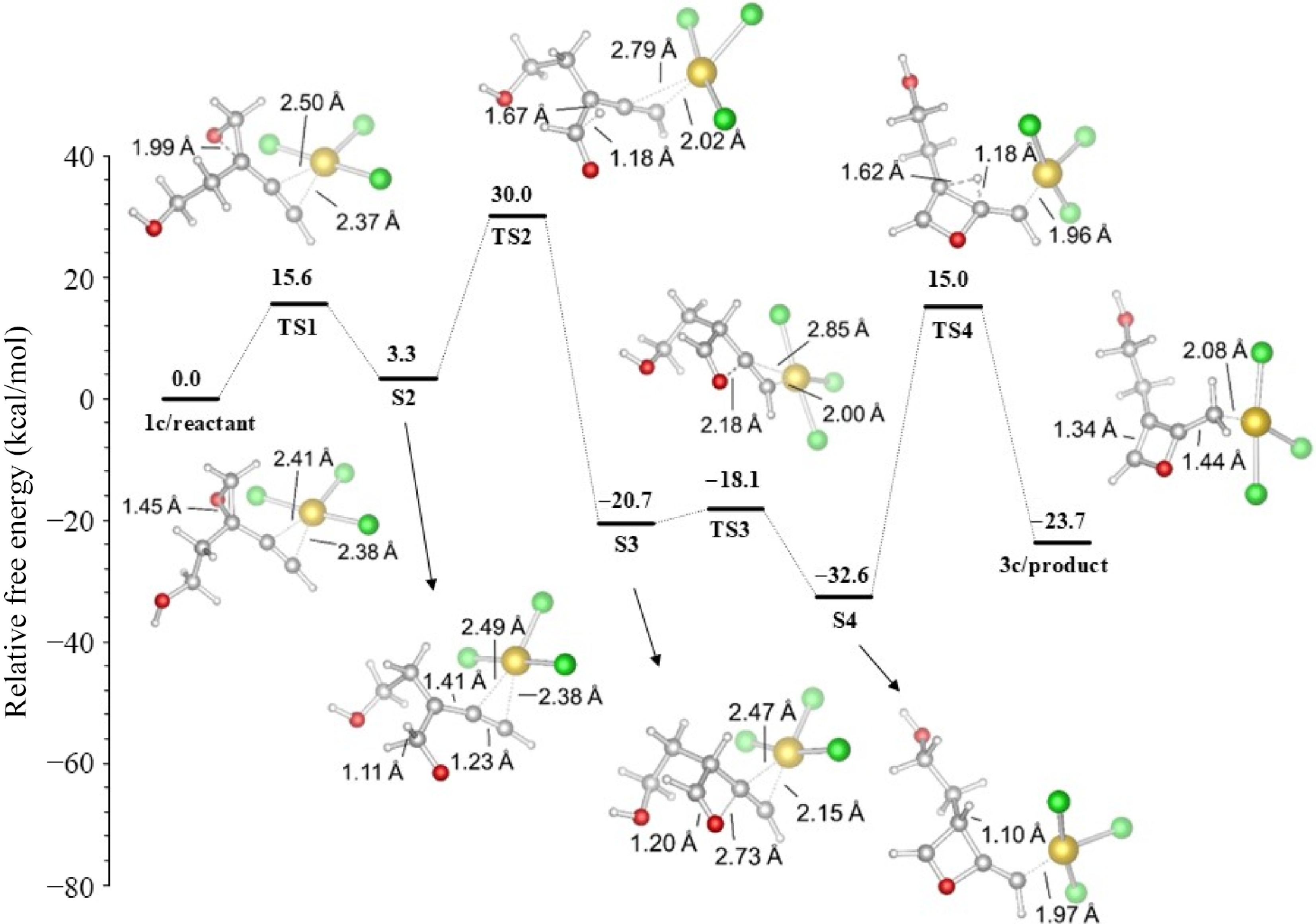

The AuCl3-catalyzed oxetene formation mechanism was not examined in the work by Hashmi et al.[6]. In our prior computational study[7], and knowledge in heterocyclic synthesis[26], we found that if the reactant includes a terminal alkyne unit (R2 = H), the reaction with the four steps takes place, as shown in Scheme 2. The first step begins with the ring-opening reaction. Subsequently, a [1,2-H] shift occurs to obtain aldehyde intermediate S3. Then, the carbonyl oxygen atom attacks the carbon (C1); thus, a ring is formed. In the continuation, the proton is moved to the alkene moiety, and the AuCl3 is separated to obtain the oxetene compound 3c.

The PCM was used in all calculations of the alternative mechanism. It is known that PCM has limitations where non-electrostatic effects dominate the solute-solvent interactions[27]. Since electrostatic solute-solvent interactions occur in PCM, electrostatic effects dominate the TSs and intermediates studied in acetonitrile. Moreover, instead of the explicit solvent model, which considers the actual solvent effects around the solute, the implicit solvent model was used in the calculations, and a continuous environment surrounding the solute was provided[20].

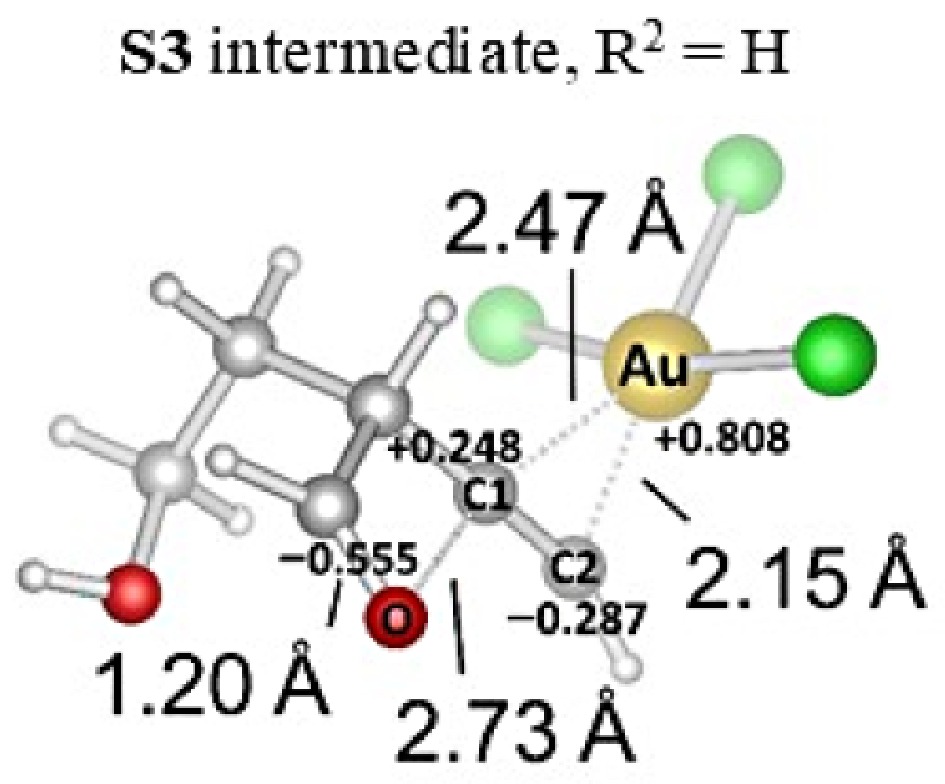

First, we calculated the NPA of the intermediate S3 that causes oxetene formation (Fig. 10). As indicated in the complex for R2 = H, the AuCl3 part is close-range to carbon C2 (2.15 Å) than C1 (2.45 Å). However, carbon C2 is charged negatively (−0.287 au), while carbon C1 is charged positively (+0.248 au). These distances and charge distributions differ from those calculated for complexes R2 = Ph and R2 = p-BrPh in Fig. 3. These results prove that the groups attached to the alkyne end affect the charge distribution and, accordingly, the distances.

Figure 11 shows the profile of the free energy of the proposed oxetene synthesis via the AuCl3. In step TS1, the epoxide ring is opened with an energy of 15.6 kcal/mol. In TS2, a [1,2-H] shift occurs with a free energy of 26.7 kcal/mol to form the aldehyde intermediate S3. The attack of the carbonyl oxygen on the carbon C1 and the formation of the four-membered ring occurs in TS3 with 2.6 kcal/mol. Then, the target product oxetene 3c formation is completed by proton transfer with 47.6 kcal/mol.

-

The mechanism for the isomerization of alkynyl epoxides to furans was successfully modeled. Moreover, an alternative mechanism for obtaining oxetene from alkynyl epoxides, accompanied by a gold catalyst, is proposed. Both mechanism modelings were performed with the M06-2X functional, which gives reliable results.

Thanks to the Hitit University Scientific Research Department for its financial support (BAP, Project No. FEF.19001.23.005) and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TUBITAK) for allowing the use of their ULAKBİM high-speed computing center.

-

The author confirms sole responsibility for all aspects of this study and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary File 1 Supplementary materials used in this study.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Basceken S. 2025. Computational analysis of the Au-catalyzed isomerization of alkynyl epoxides to furans. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e011 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0010

Computational analysis of the Au-catalyzed isomerization of alkynyl epoxides to furans

- Received: 17 February 2025

- Revised: 30 March 2025

- Accepted: 15 April 2025

- Published online: 10 June 2025

Abstract: The isomerization of epoxides to furans, accompanied by gold(III), was elucidated theoretically. The structural properties of the transition states (TSs) and intermediates were studied with B3LYP or M06-2X hybrid density functionals in various solvents. The electronic features of the substituents bonded to the alkyne part were significant in forming the furan rings. Details of the furan formations were explored, and the reactant's natural population analysis was conducted. Additionally, this computational work proposed an alternative mechanism for synthesizing oxetene rings.

-

Key words:

- Computational organic chemistry /

- Reaction mechanism /

- DFT