-

The development of efficient and sustainable advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) is essential to address the growing environmental challenges posed by emerging and persistent organic pollutants[1−3]. Currently, non-radical pathways, including singlet oxygen and direct electron transfer, offer higher selectivity for antibiotic pollutants such as sulfamethoxazole (SMX), in real wastewater, but their reactions rely on specific catalytic materials and conditions[4,5]. In contrast, hydroxyl radicals (•OH) play a central role in AOPs with high oxidation potential and non-selective reactivity, achieving effective degradation of a variety of organic pollutants[6−8]. Notably, conventional •OH-based AOPs frequently rely on external oxidants such as H2O2, which pose challenges due to non-selective reaction pathways and potential environmental concerns[9,10]. Currently, Fe-based catalysts mediate the activation of molecular oxygen through one-electron or two-electron transfer, to produce •OH and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) provide a green and cost-effective alternative for contaminant oxidation[11−13]. In particular, the cooperative oxidation cycle between zero-valent iron (Fe0), and ferrous iron (Fe2+) has demonstrated great potential in oxygen activation and ROS production[14−16]. The key to enhancing such H2O2-free AOPs lies in developing catalysts with abundant Fe0/Fe2+ species and efficient electron transfer pathways. Embedding Fe species into carbonaceous materials with excellent electrical conductivity can address the limitations of slow electron transport, Fe leaching, and poor catalyst stability[17,18]. However, conventional methods for preparing iron/carbon (Fe/C) composites, such as pyrolysis or chemical deposition, usually involve multi-step chemical processes[19,20]. These approaches often result in poorly graphitized carbon structures and limited control over the dispersion and valence structure of Fe, thereby restricting efficient electron transfer.

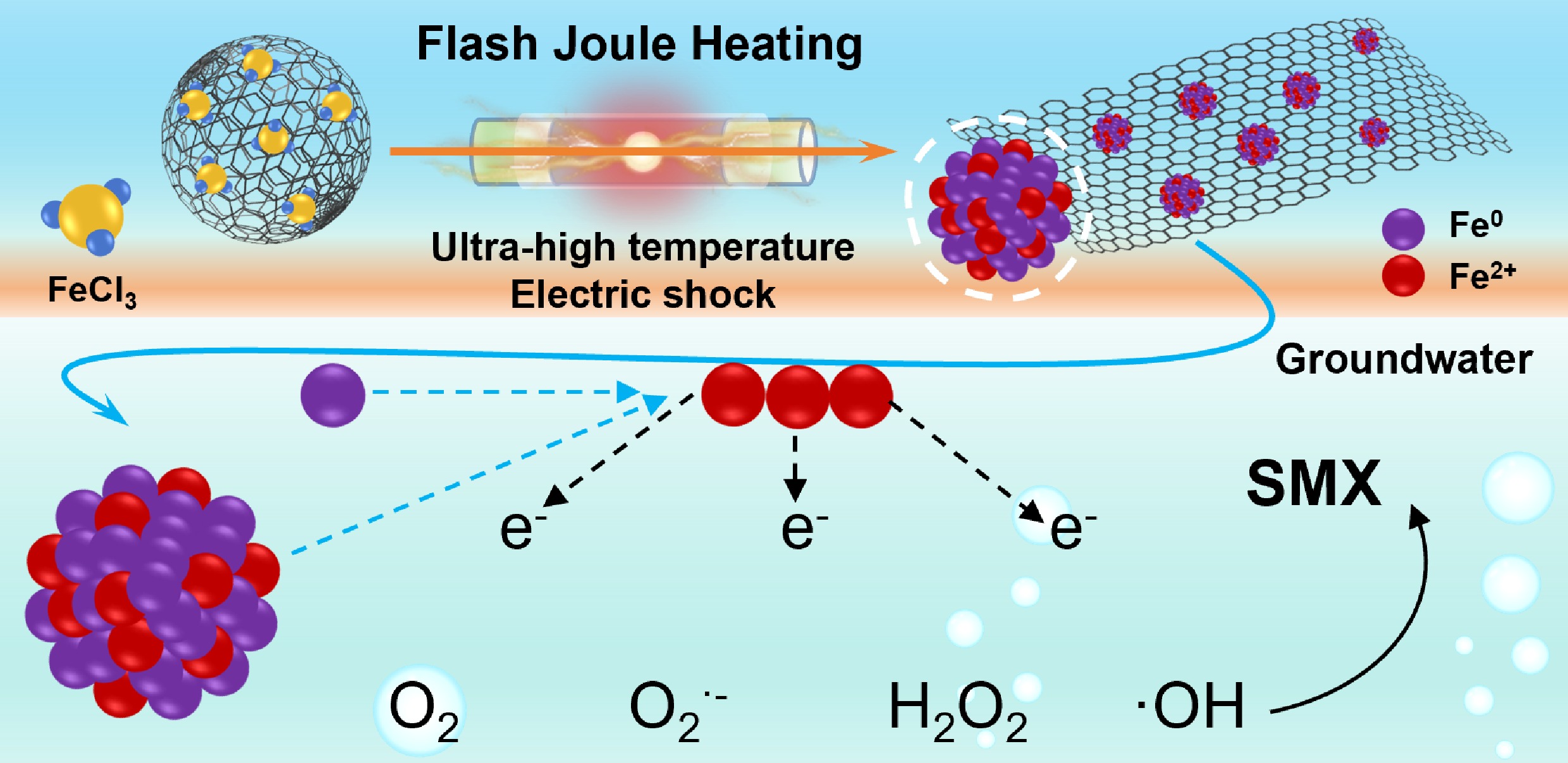

Flash Joule heating (FJH) is an emerging materials processing technique that provides a revolutionary approach to synthesizing Fe/C composites with tailored redox properties[21,22]. By applying a pulse of transient high temperature (> 3,000 K) in a targeted manner, the chemical bonds of the Fe-containing precursor are broken to generate Fe0- and Fe2+-rich species[23,24]. Meanwhile, this process promotes a high degree of graphitization of the carbon substrate, which is dispersed around the Fe species to enhance their stability. As a result, the resulting conductive carbon framework potentially facilitates electron transfer between Fe0 and Fe2+, thereby enabling molecular oxygen activation and sustained •OH generation.

In this work, Fe/C composite catalyst containing Fe0/Fe2+ species were constructed, assisted by FJH technology and the effects of FJH parameters on its structure systematically explored. The oxygen activation mechanism was investigated using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), and radical quenching experiments, with particular focus on the •OH formation. Furthermore, the degradation performance of Fe/C composite catalyst for SMX in water and soil environments were also evaluated. This study provides a green and scalable strategy for preparing high-performance AOP catalysts, deepens the mechanistic understanding of Fe-mediated oxygen activation, and demonstrates great potential for remediating organic pollutants in complex environmental systems.

-

Sources of chemicals are listed in Supplementary Text S1. Soil samples were collected from paddy fields (0–20 cm topsoil) in Shangrao, China. During collection, litter, herbs, and mineral soil were removed from the samples, which were further collected into a large single composite sample to maximize representativeness. These soils were transported directly to the laboratory, and then air dried, and homogenized with visible plant debris or rocks removed. To minimize physical-protection mechanisms of aggregation, the soils were ground to pass through a sieve with a 2-mm sieve mesh and stored in amber bottles under ambient conditions.

Preparation of Fe/C composites by FJH reaction

-

The sawdust-derived biochar and FeCl3 used as a precursor (6 mmol Fe: 1 g biochar), were uniformly mixed in anhydrous ethanol by oscillation, then dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C. In a typical FJH treatment procedure, 0.1 g of the above precursor was placed in a quartz tube (tube thickness: 2 mm, inner diameter: 6 mm, length: 45 mm) and compacted with copper electrodes to achieve a resistance of ~20 Ω, enabling successful initiation of the FJH reaction. The system was subjected to mild vacuum (~0.6 psi) and maintained under a nitrogen atmosphere to prevent oxidation. Notably, the content of Fe0 and Fe2+ can be tailored by adjusting the pulsing voltage (150–250 V). After the appropriate treatment time (100 ms), the desired FJH-derived Fe/C composites were obtained.

Characterization of Fe/C composites

-

The carbon layer structure of the Fe/C composites was observed using high-resolution electron microscopy (HR-TEM, Tecnai G2 F20 S-Twin, FEI, USA). HR-TEM coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDX) and high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images were used to investigate elemental distributions and surface morphology. The composition and crystalline phase of the Fe/C composites were collected by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D/max-2200PC, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation. The Fe species resulting from the reaction of Joule heating were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Thermo Scientific K-Alpha, USA). Raman spectra were collected and fitted using Lab-Spec6.4 software with three Lorentzian peaks at D (~1,350 cm−1), G (~1,580 cm−1), and 2D (~2,700 cm−1) bands.

Degradation of SMX by Fe/C composites activating O2

SMX degradation in aqueous solutions

-

Degradation of SMX was performed in a batch reactor. The Fe/C composites (25 mg) were added to a centrifuge tube with 25 mL SMX solutions (10 mg·L−1), and the initial pH was about 5. The carbon substrate of Fe/C composites was added independently into a centrifuge tube with 25 mL SMX solutions (10 mg·L−1) as controls. Afterward, the centrifuge tube was put in an oscillation box with 150 rpm at 298 K. The solutions were taken at a specific time, filtered through a 0.22 μm filter, and added immediately with an equal volume of methanol to prevent a reaction before measurements. The concentrations of SMX were detected rapidly by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) at a wavelength of 265 nm, 1 mL·min−1 mobile phase (the volume ratio of formic acid to methanol was 4:6), and the column temperature was 298 K.

SMX degradation in the paddy soil slurry

-

Degradation of SMX was similarly performed in a batch reactor. The Fe/C composites (25 mg), and red paddy soil (2,500 mg) were added to a centrifuge tube with 25 mL SMX solution (10 mg·L−1) without pH adjustment. The soil was added into a centrifuge tube with 25 mL SMX solution (at 10 mg·L−1), without Fe/C composites as controls. Afterward, the degradation process was the same as that of SMX degradation in aqueous solutions.

Analysis of reactive intermediates by Fe/C composites activating O2

-

5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) was used as the •OH trapping reagent, and 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-4-piperidone (TEMP) was used as the 1O2 trapping reagent. Generally, the Fe/C composites (25 mg) were added to a centrifuge tube with 25 mL chloramphenicol solutions (60 mg·L−1). Subsequently, the centrifuge tube was placed in an oscillation box at 150 rpm. The solutions were taken at 5 min, filtered through a 0.22 μm filter, and tested for radicals by an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrometer (Bruker EMXplus).

Quenching experiments were conducted using methanol for •OH, catalase (CAT) for H2O2, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) for O2•-, respectively. Benzoic acid was used as a probe to quantify •OH production. Upon reaction with •OH, p-hydroxybenzoic acid (p-HBA) was formed and quantified by HPLC. The cumulative •OH concentration was calculated according to the literature using the following equation[25].

$ \rm Cumulative\;[\cdot OH]\;produced=[p{\text -}HBA]\times 5.87 $ (1) The concentration of dissolved Fe2+ was determined according to the 1,10-phenanthroline method using an ultraviolet–visible (UV/vis) spectrophotometer at 510 nm[26]. Further details are provided in Supplementary Text S2.

-

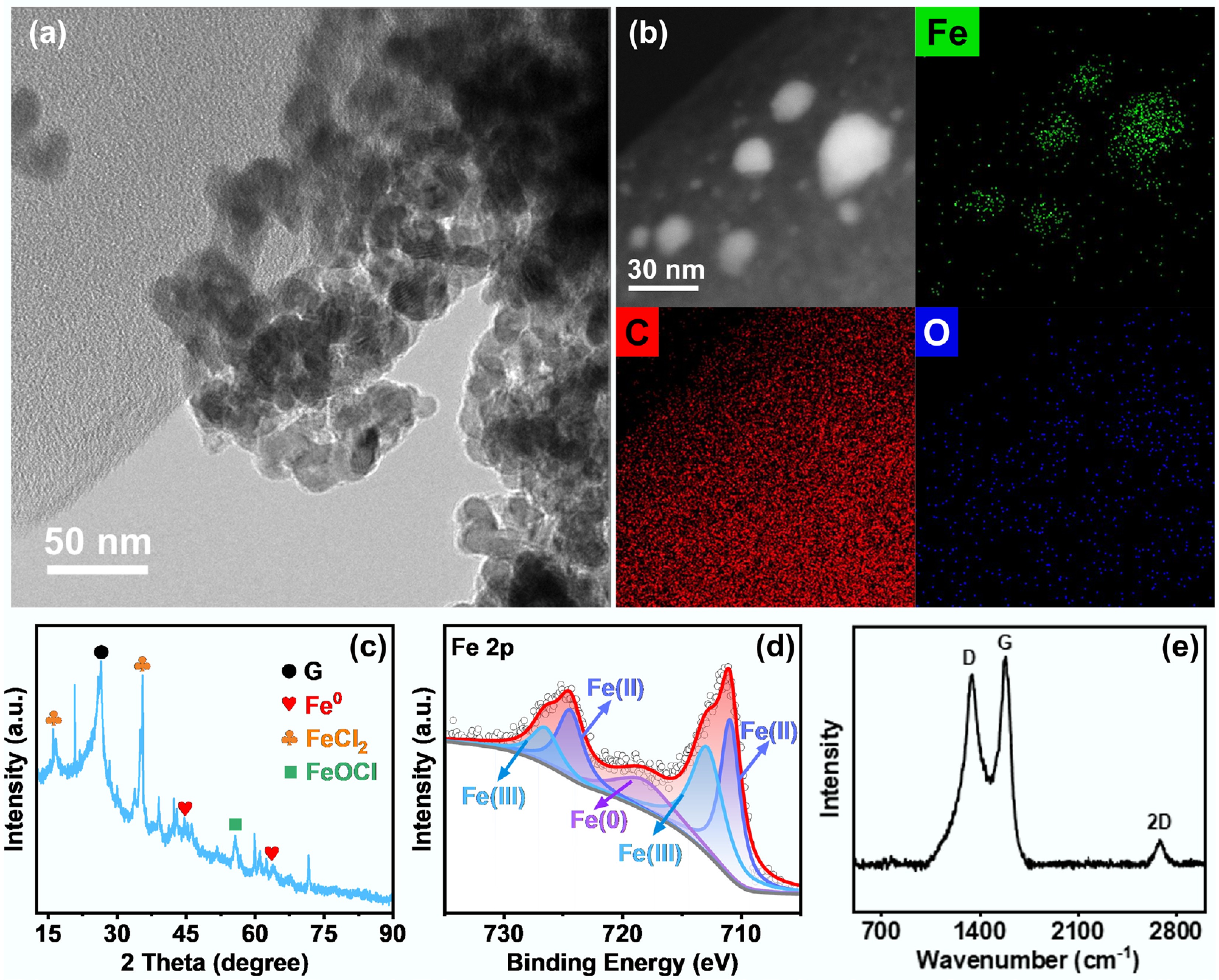

To obtain the desired Fe/C composite catalyst, a precursor composed of FeCl3, biochar, and carbon black was conventionally subjected to the FJH process (Supplementary Fig. S1a). As expected, the transient and variable current generated intense Joule heating, rapidly elevating the temperature to approximately 4,000 K (Supplementary Fig. S1b and S1c). As shown in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S2, the structural evolution of the Fe/C composite catalyst after the FJH process was systematically analyzed. The results indicated that spherical Fe nanoparticles, with an average diameter of 34.4 nm, were uniformly distributed on the carbon substrate, providing abundant catalytic sites. In the HAADF image, the Fe spheres in the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst exhibited no significant color differences, strongly indicating the absence of the Fe-oxide shell (Fig. 1b). This observation was further supported by the oxygen element mapping, which showed a dispersed oxygen distribution without dense surface rings. These findings suggest that the extreme thermal shock facilitated the cleavage of Fe–Cl and Fe–O bonds in the Fe-containing precursor, resulting in the formation of reductive Fe0 and Fe2+ species, as further confirmed by the XRD patterns (Fig. 1c). Moreover, the XPS spectra also revealed an abundance of Fe species in the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst, mainly consisting of Fe0 and Fe2+ (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1.

(a) Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images, (b) high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images, and the corresponding EDS-mapping images of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst. (c) X-ray diffraction spectra, (d) Fe 2p X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra, and (e) Raman spectra of the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst.

Simultaneously, the FJH process facilitated the graphitization of the carbon substrate and formed few-layer graphene during electrical shock exfoliation, as verified by Raman spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 1e, the D band (~1,350 cm−1) indicates structural defects or edge disordered regions within the carbonaceous framework[27]. The observed strong G peak (1,580 cm−1) originates from the in-plane stretching vibration of sp2 hybridized carbon atoms, indicating that the Fe/C composite catalyst has a well-graphitized structure. Furthermore, the presence of a relatively weak 2D peak around 2,700 cm−1 indicated the formation of few-layer graphene sheets in the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst[24]. The formed graphene layer was expected to encapsulate the Fe species, enhancing the electrical conductivity and structural stability of the Fe/C composite catalyst. Notably, the ultrafast heating and cooling rates favored the formation of uniformly dispersed Fe nanoparticles in the Fe/C composite catalyst, which can be effectively controlled by tuning the applied FJH parameters.

In summary, the conductive carbon framework may promote electron transfer between Fe0 and Fe2+ species. This acceleration of one-electron or two-electron transfer pathways enables effective O2 activation, promoting the generation of •OH and other ROS, thereby enhancing contaminant degradation.

SMX degradation by Fe/C composite catalysts via molecular O2 activation

-

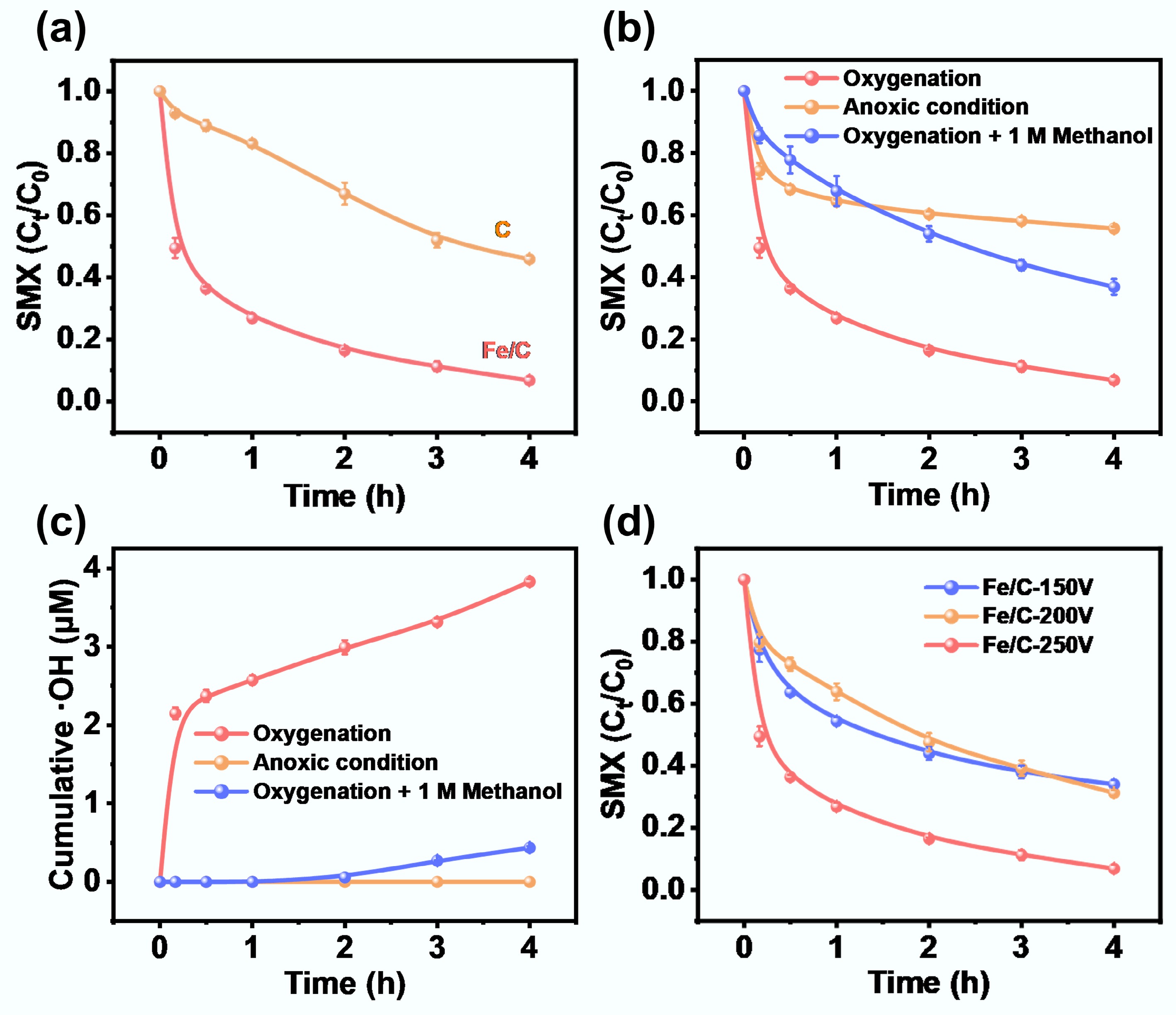

As shown in Fig. 2a, the degradation performance of SMX by Fe/C composite catalyst was evaluated in the presence of different systems. In the O2 system, the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst showed an excellent removal efficiency for SMX within 4 h, reaching up to 94.6%. In contrast, the removal efficiency (45.4%) of SMX by the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst in the anoxic system was significantly reduced, which was similar to the adsorption effect of SMX by adding only carbon material (Fig. 2b). After the addition of 1 M methanol (•OH quencher), the SMX removal efficiency of the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst in the O2 system decreased to 63.2%, suggesting that •OH played a dominant role in the SMX degradation process via O2 activation.

Figure 2.

(a) Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) removal performance of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst and carbon substrate (Note: carbon substrate represents individual biochar treated by C-FJH at 250 V). (b) SMX removal performance and (c) cumulative concentrations of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) in various systems with Fe/C-250V composite catalyst. (d) SMX removal performance of Fe/C catalysts fabricated by FJH treatment with different initial voltage. (Reaction conditions: SMX = 10 mg/L, Fe/C catalysts or carbon substrate = 1.0 g/L, pH = 7, temperature = 298 K).

The key role of •OH in the degradation process was investigated in Fig. 2c. Specifically, the accumulated •OH concentration increased significantly over time in the O2 system, reaching approximately 4 μM within 4 h. In contrast, •OH generation was negligible in the anoxic system (< 0.5 μM), underscoring the essential role of molecular O2 in facilitating •OH production. The presence of methanol markedly suppressed •OH levels in the O2 system, confirming its effective quenching capability. Interestingly, despite the presence of methanol, approximately 40% of SMX was still degraded, suggesting the involvement of alternative oxidation pathways, such as those mediated by superoxide radicals (•O2−). These results demonstrated that the removal of SMX by the Fe/C composite catalyst involved multiple mechanisms, primarily relying on O2 activation to promote •OH generation, which in turn enabled efficient SMX degradation.

In addition, the Fe/C composite catalysts were synthesized at different voltages to explore the SMX removal efficiency. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S3, the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst produced the highest •OH concentration, which was significantly higher than that of the Fe/C-200V and Fe/C-150V composite catalysts, confirming that high-voltage treatment amplified the oxidative potential of the catalyst. This improved reactivity directly contributed to superior SMX degradation performance. Thus, the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst showed a superior removal efficiency (94.6%), while Fe/C-150V and Fe/C-200V catalysts presented inferior removal efficiencies of 64.1% and 69.2%, respectively (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. S4). These findings confirmed the hypothesis that the amount of •OH generated by the Fe/C composite catalysts was positively correlated with the SMX removal efficiency. Consequently, Fe/C composites represent a compelling and potentially transformative catalyst design for the degradation of antibiotics, particularly within the context of wastewater treatment applications, offering a pathway toward more efficient and sustainable remediation strategies.

Environmental adaptability of Fe/C composite catalyst

-

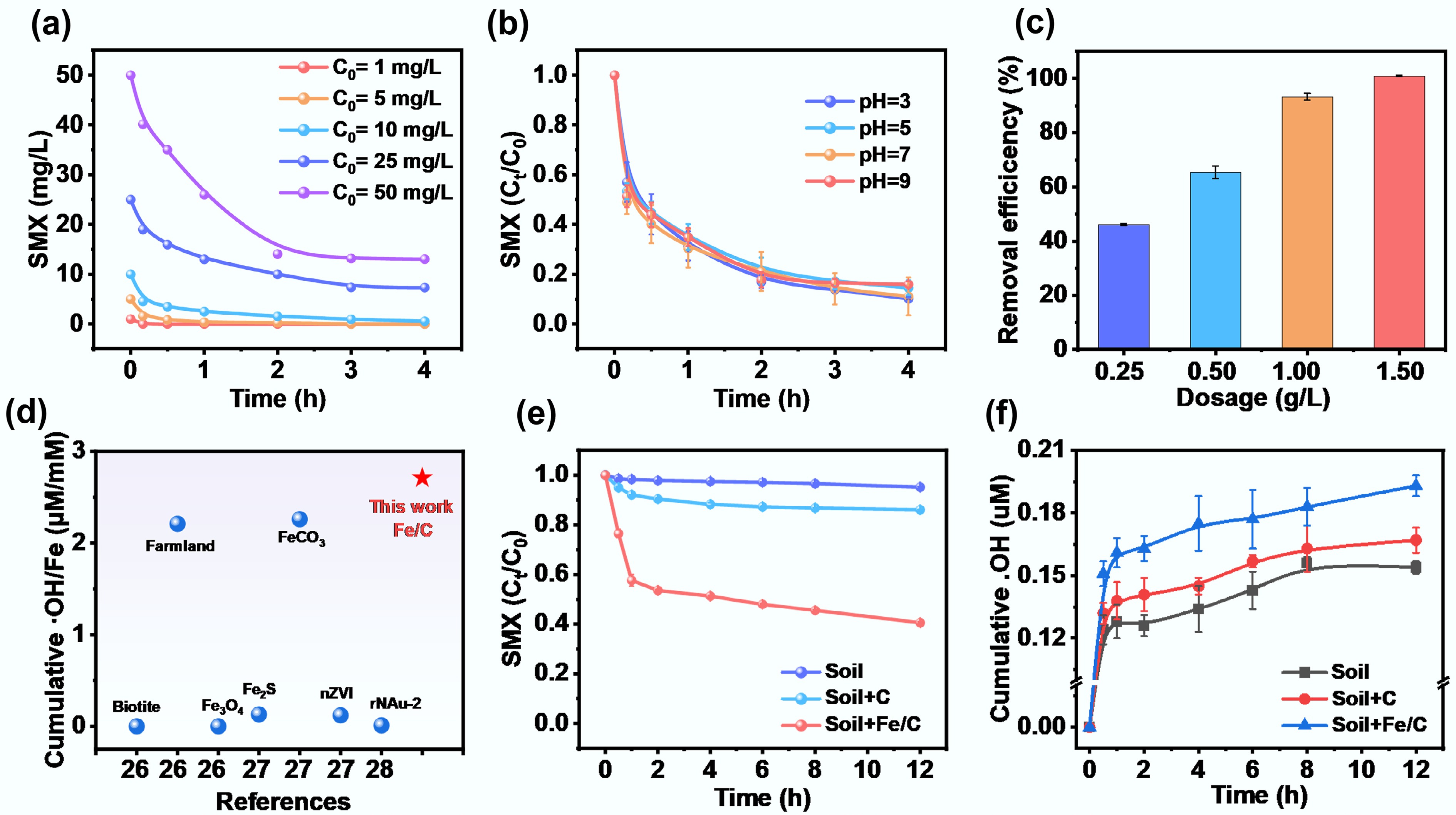

The environmental adaptability of the Fe/C composite catalyst is also a key indicator for wastewater treatment. As shown in Fig. 3a, the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst achieved almost complete removal at low concentrations, which may be due to the abundant Fe species accelerating O2 activation to produce sufficient ROS. However, its removal efficiency of SMX was greatly weakened at higher concentrations, and the reaction rate gradually slowed down over time. Figure 3b illustrates the influence of initial pH on SMX degradation by Fe/C-250V composite catalyst. Although a similar pH-dependent reactivity was observed for the Fe/C composite catalyst, it still exhibited an excellent SMX removal ability at different pH values, indicating that this catalyst has a wide range of applicability under different pH solution conditions. Notably, the removal efficiency of SMX by the Fe/C-250V composite catalyst under alkaline conditions was slightly lower, decreasing to 85.2%. The observed decrease in efficiency under alkaline conditions was attributed to two primary factors inherent to the iron-based system[1]. First, Fe2+/Fe3+ species precipitated as Fe(OH)2/Fe(OH)3 at elevated pH, which reduced the availability of soluble catalytic centers. Second, •OH underwent enhanced self-quenching, which diminished the effective oxidative capacity. Despite these challenges, the Fe/C composite still retained high performance. The carbon matrix likely facilitated the dispersion and stabilization of Fe species, inhibited aggregation and passivation, and promoted alternative catalytic pathways (such as surface-bound radicals or non-radical oxidation). These effects ensured that the Fe/C composite remained highly active even under alkaline conditions.

Figure 3.

(a) Effect of initial SMX concentration on the performance of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst for SMX removal (Reaction conditions: SMX = 1−50 mg/L, Fe/C-250V catalyst = 1.0 g/L, pH = 7, temperature = 298 K). (b) Effect of pH on the performance of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst for SMX removal (Reaction conditions: SMX = 10 mg/L, Fe/C-250V catalyst = 1.0 g/L, pH = 3−9, temperature = 298 K). (c) Effect of different dosages of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst on SMX removal efficiency (Reaction conditions: SMX = 10 mg/L, Fe/C-250V catalyst = 0.25−1.50 g/L, pH = 7, temperature = 298 K). (d) Comparison of cumulative •OH/Fe with other previous reported materials in the literature. More details can be found in Supplementary Table S1. (e) SMX removal performance and (f) Cumulative •OH generation kinetics of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst in aqueous solutions containing cinnamon soil (Reaction conditions: SMX = 20 mg/L, Fe/C-250V composite catalyst or carbon substrate = 1.0 g/L, cinnamon soil = 100 g/L, pH = 7, temperature = 298 K).

In addition, the effect of Fe/C composite catalyst dosage (0.25–1.50 g·L−1) on the cumulative generation of •OH was systematically investigated to elucidate the quantitative relationship between catalyst concentration and oxidation efficiency. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S5a, increasing the dosage from 0.25 to 1.50 g·L−1 led to a corresponding rise in cumulative •OH concentration from 1.02 to 5.48 μM. The slow increase observed with a catalyst dosage of 0.25 g·L−1 suggests that the limited number of active sites constrained the efficiency of activated O2 to •OH. However, within the higher catalyst range of 1.0–1.50 g·L−1, an accelerated increase in •OH was observed. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. S5b, the concentration of the Fe/C composite catalyst exerted a significant modulatory effect on the degradation kinetics of SMX. All groups experienced a rapid degradation phase within the first hour, with the 1.50 g·L−1 group showing the fastest degradation rate and the 0.25 g·L−1 group the slowest. This suggests that high catalyst loadings provided more active sites for promoting oxidative degradation. Correspondingly, the SMX removal efficiency increased significantly to 99.9% with 1.50 g·L−1 of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst (Fig. 3c). The unique carbon support structure also plays a pivotal role in facilitating the continuous generation of •OH by accelerating the Fe0/Fe2+/Fe3+ redox cycle. As a result, the cumulative •OH/Fe molar ratio in the Fe/C composite system reached 2.71 μM·mM−1, significantly surpassing that of conventional Fe-based materials (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table S1)[28−30], indicating superior utilization of active sites and electron transfer efficiency.

To further assess the Fe/C composite catalyst's performance in real environmental matrices, a comparative study was conducted in soil systems. As illustrated in Fig. 3e, the native soil, with limited reductive Fe species and negligible SMX adsorption capacity, exhibited minimal removal efficiency (5.01%). The addition of carbon materials led to only a slight improvement (< 15.2%), primarily due to adsorption. Additionally, the native soil exhibited a relatively weak •OH generation, with only 0.15 μM accumulated over 4 h (Fig. 3f). However, the implementation of an Fe/C composite catalyst resulted in a significant increase in •OH yield, reaching 0.20 μM. Correspondingly, the SMX removal efficiency improved markedly, with a rapid degradation phase during the first hour, followed by a slower reaction rate. Notably, owing to the quenching of ROS and the blockage of catalytically active sites by soil organic matter[31,32], the removal efficiency of SMX by the Fe/C composite decreased to only about 60.0% after 12 h. These findings substantiated that the Fe/C composite catalyst can persistently activate O2 to generate •OH even in complex soil environments, providing a cost-effective method for antibiotic pollution management.

Mechanistic insights into O2 activation and •OH generation

-

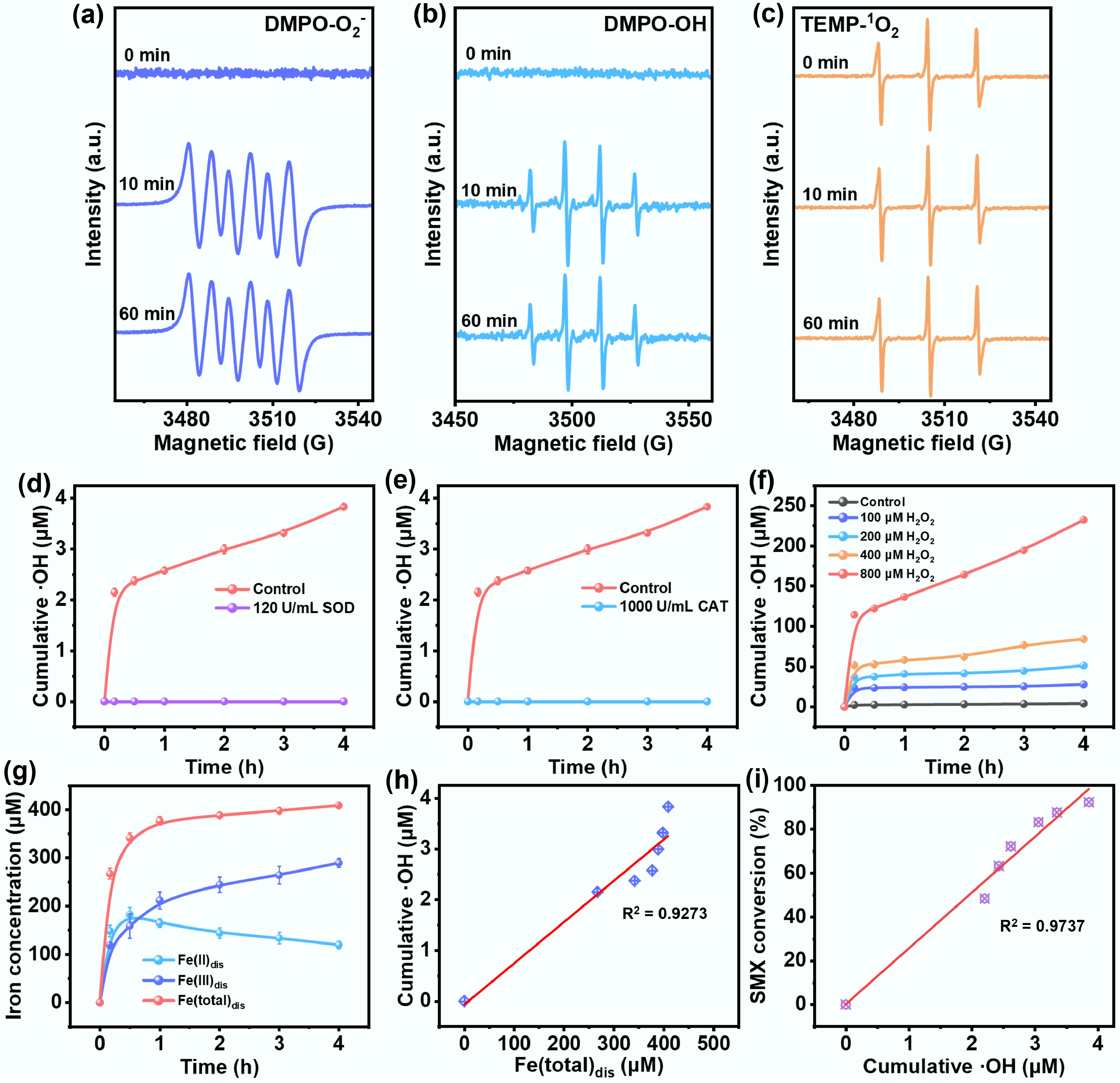

To confirm the generation pathway of ROS in the Fe/C composite catalyst system, the EPR test was systematically carried out. A characteristic triplet signal with a 1:1:1 intensity ratio was observed in Fig. 4a. The signal intensity increased significantly with reaction time (0–60 min), confirming the continuous generation of O2•−. Figure 4b displays the distinctive quartet signal (1:2:2:1) associated with the DMPO-OH, indicating the presence of •OH. Notably, no change in the singlet oxygen (1O2) signal was detected in the TEMP–1O2 test throughout the reaction, indicating that1O2 was not involved in the reaction pathway (Fig. 4c). These results demonstrate that Fe/C composite catalyst selectively promotes the activation of O2 to O2•− via a two-electron transfer pathway and further to •OH through a three-electron transfer pathway, while the generation of1O2 is limited by the surface properties or energy barriers.

Figure 4.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra recorded for the reactive oxygen species (a) O2•−, (b) •OH, and (c) 1O2 from the reaction of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst with oxygen. Cumulative concentrations of ·OH produced by Fe/C-250V composite catalyst after the addition of (d) 1,000 U/mL CAT and (e) 120 U/mL SOD. (f) Cumulative concentrations of •OH after the addition of different concentration of H2O2. (g) Evolution of dissolved Fe species. (h) The line fit of •OH concentration and total dissolved Fe. (i) The line fit of •OH concentration and SMX removal (Reaction conditions: SMX = 10 mg/L, Fe/C-250V catalyst = 1.0 g/L, pH = 7, temperature = 298 K).

The key role of O2•− and •OH in SMX degradation was further investigated through radical quenching experiments. As shown in Fig. 4d, the O2•− concentration in the control group (without scavenger) reached 3.83 μM. In contrast, the addition of 120 U·mL−1 superoxide dismutase (SOD) completely inhibited •OH generation, indicating that O2•− serves as a precursor in •OH formation. In Supplementary Fig. S6, the degradation kinetics of SMX showed a significant correlation with •OH concentration. The introduction of SOD as a scavenger significantly reduced the SMX removal efficiency to 45.4%, indicating that the conversion of O2•− to •OH was inhibited. These findings indicated that O2•− plays a dual role in the SMX degradation process, both as a direct oxidant and as a precursor to •OH.

To further elucidate the role of H2O2 in the reaction mechanism, catalase (CAT, 1,000 U·mL−1) was introduced to quench H2O2. As shown in Fig. 4e, the •OH concentration in the control group steadily increased over time, whereas the CAT-treated group showed near-complete suppression of •OH generation (< 0.1 μM), due to the rapid decomposition of H2O2. These results confirmed that H2O2 was a crucial intermediate in the ROS pathway, indicating that O2 was sequentially reduced to O2•−, then to H2O2, and finally to •OH through a three-electron transfer route. Further substantiating this mechanism, the SMX degradation kinetics presented in Supplementary Fig. S7 revealed that the control group exhibited a significant removal efficiency, which was attributed to the promotion of •OH formation via O2 → O2•−→ H2O2 → •OH[33,34]. Interestingly, CAT treatment did not completely inhibit SMX degradation, suggesting the existence of a direct electron transfer pathway on the Fe/C surface that is independent of H2O2 decomposition. These results demonstrate that Fe/C composite activated O2 follows a typical stepwise reduction pathway, in which H2O2 is an essential intermediate for the generation of •OH.

Additionally, the role of H2O2 as a direct oxidant in •OH generation was examined. As shown in Fig. 4f, the absence of H2O2 in the control group led to negligible •OH production. As the concentration of H2O2 increased from 100 to 800 μM, the generation of •OH showed a significant dosage-dependency: the 100 μM group accumulated only about 27.6 μM within 4 h, while the 800 μM group reached about 232 μM (Fig. 4f), confirming the key role of H2O2 as a precursor of •OH. Furthermore, the •OH accumulation curve exhibited a rapid increase during the first hour, followed by a plateau, indicating that excessive H2O2 may result in self-quenching or inefficient radical generation. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S8, •OH accumulation showed a strong linear correlation with H2O2 concentration (R2 = 0.97) up to 250 μM, confirming that the Fe/C composite provides abundant active sites for efficient H2O2 activation.

The variation of Fe species during the SMX degradation process was also monitored (Fig. 4g). Initially, the concentrations of dissolved Fe(II) (Fe(II)dis) and Fe(III) (Fe(III)dis) rapidly increased, reaching 190 μM and 180 μM, respectively. This phenomenon can be attributed to the preferential oxidation of Fe0 on the catalyst surface (Fe0 → Fe(II)dis + 2e−), in conjunction with the incomplete dissolution of Fe(III) oxides under acidic conditions. Over time, Fe(II)(dis) decreased to 120 μM, while Fe(III)(dis) increased to 280 μM, suggesting progressive oxidation of Fe(II) to Fe(III). This change between Fe species can be clearly observed in the Fe 2p XPS spectrum, which can also be confirmed by the XRD patterns (Supplementary Figs S9 and S10). Notably, the total dissolved Fe(total)dis concentration was positively correlated with •OH production, highlighting the importance of Fe dissolution in ROS generation. Moreover, the SMX degradation exhibited a strong linear correlation with cumulative •OH concentration (R2 = 0.97), directly indicating that the oxidation reaction involving •OH was the main mechanism of SMX degradation.

-

In summary, an FJH-assisted strategy to synthesize high-performance Fe/C composites through current-induced rapid self-heating is reported, enabling efficient degradation of SMX in both aqueous and soil environments. The FJH process promoted the in-situ formation of reductive Fe0/Fe2+ species uniformly anchored within a partially graphitized carbon matrix. This configuration enhanced the electron transfer capacity and structural stability of the catalyst, contributing to effective O2 activation and sustained •OH generation. The catalytic activity was strongly influenced by the FJH voltage, which governs the distribution of Fe species and the formation of active sites. EPR spectroscopy elaborated the radical generation pathways implicated in the degradation process. The overall degradation mechanism was observed to exhibit multi-mechanistic characteristics, encompassing contributions from both •OH-mediated, and O2•− involved pathways. This work contributes to the development of design principles for Fe/C composites employed in environmental remediation, emphasizing the importance of multi-pathway oxidation mechanisms and structural stability considerations for real-world applications.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/scm-0025-0006.

-

Xiangdong Zhu conceived the initial idea and experimental design. Aodi Li and Hua Shang performed the experiments and characterizations with the assistance of Chao Jia. All authors contributed to the analysis and discussion of the data. Chao Jia and Hua Shang wrote the original draft of the manuscript. Yong Jiang, Jibiao Zhang, and Xiangdong Zhu reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22276040).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Rapid self-heating process for synthesizing Fe/C composites containing Fe0/Fe2+ species.

Electron transfer between Fe0 and Fe2+ was promoted by the conductive carbon framework.

This composite exhibited efficient molecular oxygen activation and sustained •OH generation.

The degradation of sulfamethoxazole was achieved in both aqueous and soil environments.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Supplementary Table S1 The comparison of cumulative •OH/Fe by different Fe-containing material.

- Supplementary Text S1 Chemicals.

- Supplementary Text S2 Detection of iron species.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 (a) Schematic diagram of the process of preparing Fe/C catalysts by flash Joule heating (FJH) technology. (b) Recording of (b) voltage, current and (c) temperature changes of the synthesized Fe/C-250V composite catalyst during the FJH reaction.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 (a) High-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images and (b) size distribution histogram of Fe particle in Fe/C-250V composite catalyst.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 The ability to produce hydroxyl radicals (•OH) of Fe/C catalysts fabricated by FJH treatment with different initial voltage.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 (a) −ln(C0/Ct) of SMX versus time and (b) Kobs of SMX degradation of Fe/C catalysts fabricated by FJH treatment with different initial voltage.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 (a) Cumulative •OH and (b) the removal efficiency of SMX of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst with different dosages.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 SMX removal performance of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst after the addition of 120 U/mL SOD.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 SMX removal performance of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst after the addition of 1,000 U/mL CAT.

- Supplementary Fig. S8 The line fit of •OH concentration and H2O2 addition.

- Supplementary Figs S9 Fe 2p X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy spectra of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst at different reaction times (Reaction conditions: SMX = 10 mg/L, Fe/C-250V catalyst = 1.0 g/L, pH = 7, temperature = 298 K).

- Supplementary Fig. S10 X-ray diffraction spectra of Fe/C-250V composite catalyst at different reaction times (Reaction conditions: SMX = 10 mg/L, Fe/C-250V catalyst = 1.0 g/L, pH = 7, temperature = 298 K).

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jia C, Li A, Shang H, Jiang Y, Zhang J, et al. 2025. Rapid self-heating synthesis of Fe/C composites for molecular oxygen activation toward organic contaminant degradation. Sustainable Carbon Materials 1: e005 doi: 10.48130/scm-0025-0006

Rapid self-heating synthesis of Fe/C composites for molecular oxygen activation toward organic contaminant degradation

- Received: 26 June 2025

- Revised: 28 August 2025

- Accepted: 11 October 2025

- Published online: 27 October 2025

Abstract: The development of efficient advanced oxidation processes for organic pollutant degradation remains a significant challenge. Herein, we report a rapid self-heating strategy to synthesize iron/carbon (Fe/C) composites for molecular oxygen activation. The flash Joule heating process promotes thein-situformation of reductive Fe0/Fe2+ species uniformly anchored within a partially graphitized carbon matrix, which enhances electron transfer and structural stability. The Fe/C-250V composite catalyst exhibits excellent catalytic performance in activating molecular oxygen to generate hydroxyl radicals (•OH), achieving 94.6% removal of sulfamethoxazole (SMX). The degradation process involves multiple pathways, primarily through •OH-mediated oxidation supplemented by superoxide radical (O2•−) participation. Notably, the Fe/C composites demonstrate robust environmental adaptability, maintaining effective degradation performance across different pH conditions, and showing promising results in both aqueous and soil environments. This work provides valuable insights into the design of high-performance Fe-based catalysts for environmental remediation applications.