-

The observation of floral opening and closure has a long history. In ancient Egyptian civilization, the water lily (Nymphaea), which blooms at dawn and closes at dusk, was revered as a 'symbol of the sun god Ra'. Since the mid-18th century, Carl Linnaeus systematically documented diurnal movements of floral organs in Philosophia Botanica[1], while renowned naturalists such as Augustin Pyramus de Candolle and Charles Darwin began investigating the physiological mechanisms underlying these floral rhythms[2]. Floral opening and closure are important features of the reproductive syndrome, facilitating pollen removal in male and bisexual flowers, as well as pollination, fertilization, and seed set in female and bisexual flowers[3]. The flowers of Arabidopsis thaliana open in the morning and close in the afternoon—a phenomenon so commonplace that it has long been overlooked—the biological significance underlying this phenomenon remains unexplored until now. A recent study by Liu et al. unveils an elaborate two-step self-pollination mechanism in Brassicaceae, dependent on petal closure, where coordinated growth and movement of petals, stamens, and pistils collectively enable this process[4]. This discovery challenges the conventional views of autogamy as a single, static event, elucidates how plants maximize fertility under pollen-limiting conditions and holds profound implications for both evolutionary biology and agricultural productivity.

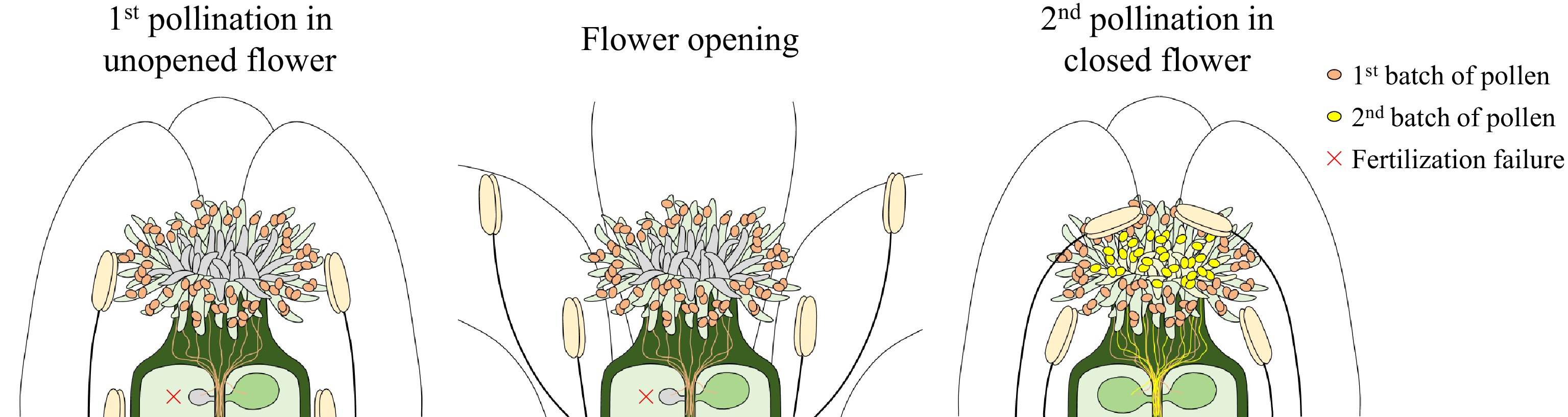

The study focuses on A. thaliana, a model self-pollinating species, and reveals that pollination occurs in two distinct phases. Initially, pollen is deposited on the lateral regions of the stigma within unopened flowers (pre-anthesis cleistogamy). Approximately 7 h after flower opening, petals close, pressing dehiscent anthers toward the central region of the stigma for a second self-pollination (Fig. 1). This sequential process almost doubles pollen deposition and expands the effective pollination area from 55.2% to 91.8%. While the first pollination alone suffices for a nearly full seed set under optimal conditions, the second step becomes critical when pollen viability or quantity is compromised. Using mutants with delayed anther dehiscence (myb108) or gamete fusion defects (hap2/gcs1+/− and dmp8/dmp9), the authors demonstrate that the second pollination rescues fertility by increasing pollen tube targeting efficiency and enabling fertilization recovery[5,6] (Fig. 1). For instance, in myb108, seed set surged from 8.6% to 85.8% when the second pollination occurred. Similarly, under heat stress (35 °C), which reduces pollen viability[7,8], the two-step process elevated the seed set from 56.3% to 78.6%. These findings emphasize the adaptive value of sequential pollen deposition in mitigating environmental and genetic challenges. The mechanism is conserved in two other self-pollinating Brassicaceae species, Capsella rubella and Cardamine flexuosa, where the two-step self-pollination process similarly enhances stigma coverage and pollen quantity. However, outcrossing relatives like Arabidopsis lyrata and Brassica rapa lack coordinated flower closure or stamen-pistil realignment, suggesting that this strategy is tailored to selfing species[4,9]. The absence of this trait in outcrossing species aligns with their reliance on external pollinators and mechanisms to avoid self-fertilization, such as spatial separation of reproductive organs[10,11].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of two-step self-pollination by flower closure in Arabidopsis. The initial pollination occurs in unopened flowers, and the dehisced long stamens come into contact with lateral regions on the stigma's surface (left panel). When the flowers open, both the lengths of the stamens and pistil increase, but the long stamens become slightly longer than the pistil (middle panel). Approximately 7 h after the initial pollination, the closure of petals forces the long stamens into contact with the pistil again so that the second pollination occurs, doubling pollen deposition in the central region of the stigma's surface (right panel). This acts as a backup mechanism so that fertilization recovery is triggered in case unfertilized ovules remain. Notably, the second pollination is crucial for maximizing fertility under unfavorable conditions.

This study bridges gaps in our understanding of how self-pollinating plants balance reproductive assurance with resource efficiency[12]. By decoupling pollination events, plants achieve two goals: (1) securing baseline fertility through the initial pollination before the flower buds open; and (2) reserving a 'backup' pollen supply to counteract fertilization failures under unfavorable environmental conditions[13]. The 7 h interval between the two batches of pollinations coincides with the timing of fertilization recovery[5], indicating that the second pollination caused by petal closure not only supplements pollen but also coordinates with the plant's intrinsic rescue mechanisms. From an evolutionary perspective, this strategy may represent a refinement of delayed selfing, a reproductive assurance mechanism that occurs after opportunities for outcrossing diminish[14]. However, in Arabidopsis, the second pollination acts as a contingency rather than a delayed tactic, ensuring maximal fertility. This nuanced adaptation highlights the plasticity of plant reproductive strategies in response to ecological pressures.

Interestingly, this study elucidates in detail the critical contribution of flower closure (primarily petal closure) to the success of self-pollination. The traditional view holds that the main functions of petals are to attract pollinators or protect the internal reproductive organs. Certain lineages have even evolved highly elaborate petals to enhance their attractiveness to pollinators[15−17], whereas the functional significance of simple petals has been underestimated to some extent. Liu et al. revealed that the second round of self-pollination in Arabidopsis is achieved through physical pressure generated by petal closure, which forces the elongated anthers into direct contact with the stigma, thereby doubling pollen deposition—a mechanism analogous to that observed in Podophyllum hexandrum (Berberidaceae)[18]. Moreover, the spatial alternation of pollen deposition areas in the two pollination events aligns precisely with the basipetal senescence of papilla cells of stigma[19]. Following the initial pollination, papilla cells at the stigma periphery senesce, while those at the central region retain high receptivity and just await to receive the second batch of pollen delivered by petal closure[19] (Fig. 1). Such exquisite coordination highly depends on the synergistic regulation among floral organs including petal, stamen, and pistil, which reminds us that even the quietest flowers harbor intricate strategies for survival.

The discovery also holds promise for crop improvement, particularly for staple crops vulnerable to climate change-induced pollen limitation. For example, heat stress during flowering—a growing threat under global warming—severely decreases pollen viability in cereals and legumes[7]. Engineering crops to enable multiple pollen deliveries through natural floral opening and closure holds immense potential for mitigating yield losses caused by extreme climate changes. Moreover, the conservation of this mechanism across Brassicaceae suggests that key regulatory genes (e.g., those controlling petal closure or stamen elongation) may be identified and adapted for application in other plant species.

While Liu et al. provide compelling evidence for the two-step self-pollination mechanism and its adaptability, there are still several unresolved questions. First, why do flowers open at all if the initial pollination occurs in closed buds? The authors hypothesize that transient flower opening may allow infrequent outcrossing, a reproductive assurance to balance inbreeding depression[20], which still needs to be verified in natural populations. Second, the molecular drivers of stamen-pistil coordination and petal closure are unclear. Identifying the genetic and hormonal regulators of these processes could lay the foundation for the development of new biotechnological tools. Finally, the universality of this mechanism outside Brassicaceae is unknown. Comparative studies in other selfing clades (e.g., Solanaceae or Fabaceae) could reveal whether this is a lineage-specific innovation or a convergent evolutionary strategy under pollen limitations.

HTML

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32221001).

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: draft manuscript preparation: Yao X, Shan H, Kong H; diagram drawing: Yu D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Yao X, Yu D, Shan H, Kong H. 2025. A two-step dance: maximizing fertility through sequential self-pollination in Brassicaceae. Seed Biology 4: e011 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0011 |