-

Cordyceps, initially identified in the 18th century by Jesuit missionaries in China, gained attention in the 1950s when Chinese scientists isolated cordycepin, revealing its antitumor and antiviral capabilities. Since then, extensive research has investigated its health advantages, such as enhancing the immune system, anti-aging effects, and potential in cancer therapy[1]. This organism is classified within the Kingdom Fungi, Division Ascomycota, also referred to as 'Sacfungi', Class Sordariomycetes, Order Hypocreales, Family Cordycipitaceae, Genus Cordyceps, and Species C. militaris, encompassing around 600 species[2]. Most Cordyceps spp. are parasitic, primarily targeting arthropod insects[3], and other fungi, with some exhibiting a high degree of host specificity. The meiotic or mitotic spores invade the larva, proliferating through the insect via hyphae, leading to biomass accumulation that ultimately kills and mummifies the host. The fungus ruptures the host's body, forming a sexual stroma that extends above the soil while remaining connected to the dead larva below. The fungus emerges from the underground cadaver, producing a 1–8 cm long orange fruiting body covered by stroma. The spores are septate, hyaline, long filiform, and smooth. For centuries, Cordyceps, a remarkable entomopathogenic fungus, has been utilized in traditional Chinese medicine. Recent scientific advancements have enabled the successful cultivation of C. militaris on artificial media in laboratory settings. It is now recognized in Western countries for its immune-boosting, anti-aging, and aphrodisiac properties. Numerous nutraceutical products on the market contain Cordyceps spp., such as didanosine derived from C. militaris. Cordyceps spp. are found worldwide, with significant markets in China, Nepal, Japan, Bhutan, Vietnam, Korea, and Thailand[4]. Cordyceps militaris is utilized in the production of various medications due to its rich array of essential biochemicals. It contains higher levels of the nucleosides cordycepin and adenosine compared to Cordyceps sinensis. Additionally, C. militaris includes—ergothioneine, aminobutyric acid (GABA), and several biologically active compounds such as D-mannitol (cordycepic acid), sterols (ergosterol), xanthophylls (including carotenoids like lutein and zeaxanthin), phenolic compounds (including phenolic acids and flavonoids), statins (lovastatin), vitamins, and essential minerals (magnesium, selenium, potassium, and sulfur)[5]. The primary active constituents of C. militaris are cordycepin, cordymin, and adenosine. Notably, cordycepin exhibits antibacterial and antiviral properties that bolster various immune responses in humans, while adenosine plays a role in altering cellular responses, by apoptosis, cell differentiation, etc. Furthermore, C. militaris is gaining recognition as a potential biocontrol agent in agriculture. Cordyceps militaris exhibits antimicrobial[6] properties, with various components demonstrating activity against both bacterial and fungal pathogens. While its effectiveness against a broad spectrum of human pathogens is recognized, its application in managing plant diseases remains limited. Some studies have explored its impact on soil-borne plant pathogens, confirming its efficacy due to specific antimicrobial compounds. Among the secondary metabolites of C. militaris, cordycepin is significant for its role in insect control. Conversely, cordymin has been shown to combat numerous plant pathogens, such as Mycospharella arachidicola, Rhizoctonia solani, and Bipolaris maydis, by inhibiting their mycelial growth. Additionally, the polysaccharides in C. militaris serve as bioactive compounds that engage with the host immune system to combat various insect pests and diseases. Research on methanol extracts and culture filtrates of C. militaris, particularly cordycepin, has demonstrated strong growth-inhibiting effects on bacteria such as Clostridium sp. The antifungal properties of C. militaris were evaluated against several fungi, revealing the highest inhibitory effects against Aspergillus spp., Penicillium funiculosum, Penicillium ochrochloron, and Trichoderma viride[7].

Due to the distinct physical and chemical characteristics of nanoparticles, they are increasingly attracting interest in agriculture, particularly in crop production and protection. Various methods exist for synthesizing nanoparticles, including chemical reduction, photochemical techniques, thermal decomposition, gamma irradiation, mechanical milling, green biosynthesis, sol-gel processes, and colloidal methods[8]. These nanoparticles, which range in size from 1 to 100 nm, find uses across diverse fields such as electronics, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, biotechnology, and medicine[9]. Researchers are particularly interested in nanoparticles due to their high surface-to-volume ratio and their ability to interact effectively with other particles[10]. Among these, green nanoparticles stand out as a single-step, eco-friendly approach that is both economically advantageous and environmentally safe[11]. In recent decades, the green synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles has emerged as a prominent area of research with significant applications. The green synthesis of nanoparticles offers several benefits, including cost-effective production methods, compatibility with other control strategies, and environmental friendliness[12]. This method involves generating nanoparticles using various living organisms, including bacteria, algae, fungi, plants, etc[13]. Bioactive compounds extracted from natural sources possess self-capping and stabilizing agents, allowing them to maintain stability without the need for external stabilizers. In this sense, C. militaris has been identified as capable of producing various nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), silver nanoparticles (AgNPs)[14], zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs)[15], etc. Although chemicals are utilized in this process, their nano size, reduced quantities, and altered chemical properties mitigate their potential harm to the environment. For many decades, it has been recognized that nanoparticles can effectively control plant pathogens. However, the potential of green nanoparticles derived from C. militaris in managing plant diseases remains underexplored. Therefore, further research is essential to bridge the existing knowledge gap in this field.

The main aim of this review is to investigate the diverse biological and agricultural importance of C. militaris and its developing role in green nanotechnology. This paper seeks to offer a thorough understanding of the fungus, starting with its historical discovery, macroscopic and microscopic features, and extending to its significant pharmacological relevance driven by powerful bioactive compounds. It emphasizes the distinctive medicinal attributes of C. militaris, including its involvement in RNA chain termination, anticancer mechanisms, and entomopathogenic properties that render it both a therapeutic and ecological wonder. The review also examines the principles of green nanoparticle synthesis utilizing C. militaris extracts, providing details on their physicochemical characterization through sophisticated analytical techniques such as ATR-FTIR, SEM, and DLS. Attention is directed towards the various biocidal properties of nanoparticles derived from C. militaris, including their potential applications as eco-friendly bioherbicides, biopesticides, bactericides, fungicides, and nematicides. The paper's scope further includes an assessment of how these green nanomaterials contribute to sustainable agricultural practices by minimizing chemical inputs and improving plant and soil health. In conclusion, it offers future insights on the integration of Cordyceps-based nanobiotechnology into modern biocontrol and medical approaches, highlighting its potential as a next-generation bioresource for sustainable development.

-

Cordyceps militaris is a prominent entomopathogenic fungus with a significant historical presence in both traditional medicine and modern research. For centuries, it has been utilized in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and Tibetan medicine as a natural treatment for respiratory issues, fatigue, and to boost the immune system. While often regarded as a substitute for the highly esteemed C. sinensis, C. militaris contains similar bioactive compounds, establishing it as an important medicinal fungus[4]. The earliest scientific reference to C. militaris can be traced back to Carl Linnaeus in 1753 in his work Species Plantarum[16]. Scientific exploration of Cordyceps spp. began approximately 300 years ago, when C. militaris was classified under the name Clavaria due to its Clavaria like stromata[17]. Linnaeus continued to use the name Clavaria and noted several Cordyceps spp. in his influential work Species Plantarum[17]. Since then, it has garnered the interest of notable mycologists such as Persoon[18], Fries[19], Link[20], Berkeley[21], Tulasne et al.[22], Saccardo[23], and Massee[24], who described it under various generic names. Historical literature suggested several generic names for Cordyceps, including Clavaria, Sphaeria, and Torrubia, until Link[20] established Cordyceps as the definitive generic name. Interest in this fungus surged in the 20th century as researchers discovered cordycepin, a bioactive compound with promising antibacterial, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory effects. Recent studies have emphasized its pharmacological advantages, such as immune modulation, antioxidant properties, and enhancement of endurance. Unlike C. sinensis, C. militaris can be cultivated in controlled environments, making it more feasible for large-scale production and pharmaceutical use. Recent advancements in biotechnology have enhanced the cultivation of C. militaris, maximizing the production of bioactive compounds. As scientific validation grows, this fungal species remains a significant asset in the fields of medicine and health sciences[4].

-

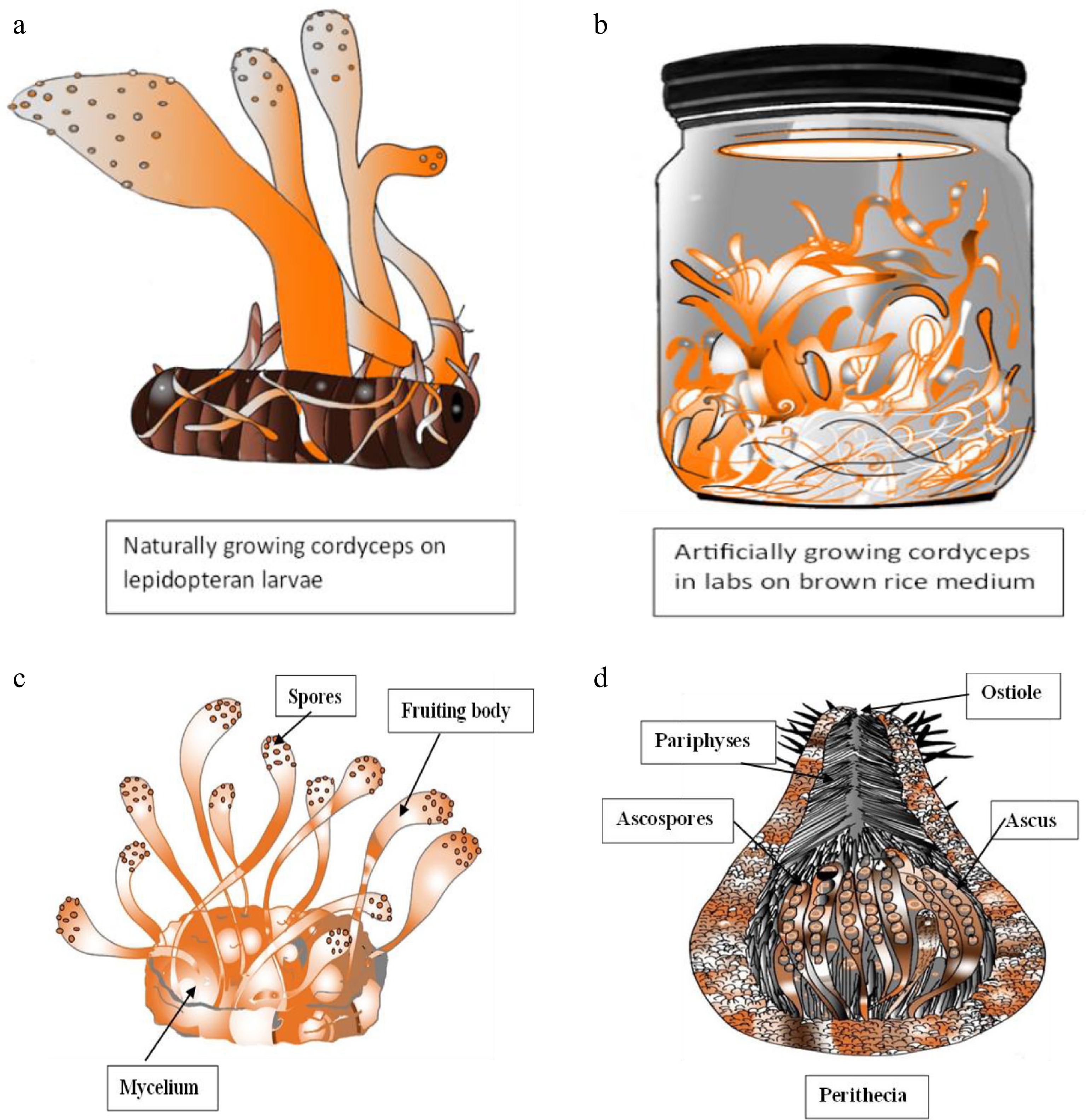

Cordyceps are classified within the Kingdom Fungi, Division Ascomycota, commonly referred to as 'Sacfungi', and falls under the Class Sordariomycetes, Order Hypocreales, Family Cordycipitaceae, Genus Cordyceps, and Species C. militaris[2]. The macroscopic characteristics of C. militaris include bright orange to reddish-orange fruiting bodies, which are either club-shaped or cylindrical, typically ranging from 2 to 6 cm in height (Fig. 1a–c). Microscopically, these structures contain perithecia, which are flask-shaped fruiting bodies located within the orange club-like stromata (Fig. 1d). Each perithecium has a small opening at the top, known as an ostiole, for spore release and is composed of asci and paraphyses, the latter being sterile filaments. The ascospores are fragmented, with each perithecium housing asci that contain eight ascospores. The asci are cylindrical or clavate, eight-spored, and feature a distinct apical cap. Upon maturation, spores are expelled through the ostiole. The hyphae are colorless and septate, leading to the formation of conidiophores. On these conidiophores, hyaline, flask-shaped phialides are produced, which subsequently generate barrel-shaped conidia[25].

-

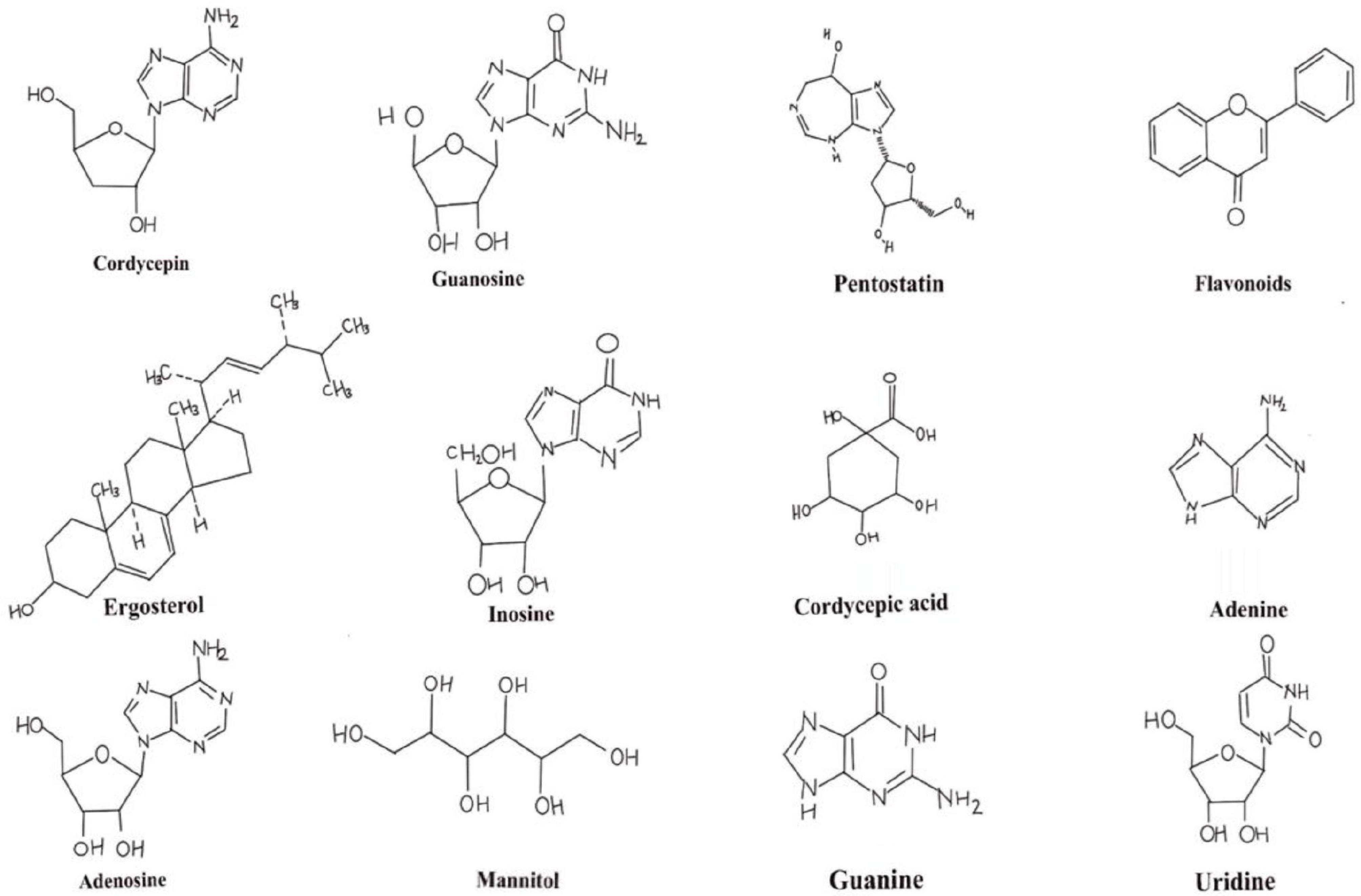

Due to its high medical significance, Cordyceps has been widely used in the production of medicines. It consists of various bioactive metabolites like cordycepin, adenosine, inosine, mannitol, sterols, polysaccharides, pentostatin, and cordymein, which has been considered very useful in cancer treatment, improving cardiovascular health, and various other activities[26] (Fig. 2). Cordycepin exhibits potent anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral properties by inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, making it valuable in treatments for leukemia and other cancers, while also reducing inflammation[27,28]. Adenosine supports cardiovascular health by acting as a vasodilator, widening blood vessels to improve circulation and benefiting heart health[29]. Inosine enhances immune function and neural health by promoting antibody production and offering neuroprotective effects, which can be beneficial for neurological diseases and immune support[30]. Mannitol serves as both a diuretic and an antioxidant, helping to lower blood pressure by promoting urination and reducing oxidative stress through the elimination of free radicals. Sterols aid in cholesterol management and inflammation reduction, helping to lower LDL cholesterol levels and contributing to cardiovascular health[31]. Polysaccharides play a crucial role in boosting immune function and exhibiting anti-tumour effects by enhancing immune cell activity and inhibiting tumour growth, making them valuable for cancer treatments and general immune support[32]. Pentostatin is widely used in cancer treatment as it inhibits adenosine deaminase, a crucial enzyme for certain cancer cells' survival, making it particularly effective in treating specific types of leukemia[33]. Superoxide dismutase acts as an antioxidant enzyme that neutralizes free radicals, reducing oxidative stress and aging related damage. Cordymin is a protein that exhibits antifungal and immunomodulatory characteristics, aiding in antimicrobial defense[34]. Flavonoids are known for their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardiovascular-protective benefits. Extract of C. militaris reduces melanin synthesis and inhibits tyrosinase activity, hence preventing age spots, lightening skin tone, and promoting more even and smoother skin[35]. Nucleosides such as guanosine and uridine are involved in cellular metabolism and neuroprotection[5]. The various other compounds with their medicinal properties are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Medicinal properties of different chemical compounds present in C. militaris.

Sl. No. Biomolecule Therapeutical effects Mechanism Ref. 1 Cordycepin (3′-deoxyadenosine) Anti-fatigue or Ergogenic It activates AKT/mTOR and AMPK signalling pathways, thereby lowering ROS and lactate levels, while also acting as an indirect precursor of NO and ATP. [36] Anti-cancer activity It induces apoptosis in cancer cells by suppressing telomerase and CXCR4 (reducing migration in liver cancer). It also down-regulates Bcl-xL and Bcl-2, and activates Fas. [37] Immunomodulatory activity It activates the iNOS, COX-2 and NF-κB pathways and stimulates macrophages to release TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6 and PGE2. [38] Anti-inflammatory activity It suppresses the expression of iNOS and COX-2, and lowers MDA, IL-1β and TNF-α levels. [39] Antiviral It is found to be effective against SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 virus. [40] 2 Phenolic compounds Antioxidant property Activity of radical scavenging is provided. [41] 3 Ergothioneine Antioxidant property It protects he cell and radical scavenging. [42] 4 Selenium (Se) Antioxidant property When grown in selenium enriched medium it increases the antioxidant properties. [43] 5 Glycoproteins Nutritional property When it is taken as a food supplement, it helps in improving health. [44] 6 CMIMP (C. militaris Immunomodulatory Protein) from FIP (Fungal Immunomodulatory Protein) family Immunomodulatory property It enhances immune cell function and proliferation and stimulates the production of cytokines. [45] 7 Ergosterol Blood coagulant property Estrogen leads to shortening of PT and APTT and reduction of fibrinogen levels thus enhancing clotting of blood. [46] 8 TCTN3 (Tectonic-3 protein) Anti-cancer property Cordyceps militaris downregulates it leading to apoptosis in lung cancer cells. [47] 9 Polysaccharides

(e.g., CBP-1, P70–1)Anti-inflammatory Modify oxidative stress indicators and pro-inflammatory cytokines. [48] Antioxidant (P70–1 and CBP-1) It scavenges DPPH, hydroxyl and ABTS radicals, chelates Fe2+, increases GPx, SOD and catalase activities, and reduces MDA levels. Immunomodulatory It boosts phagocytosis and activates macrophages and lymphocytes to enhance immune responses. [49] Anti-fatigue It boosts antioxidant-enzyme activity and ATP levels while reducing oxidative stress. [50] -

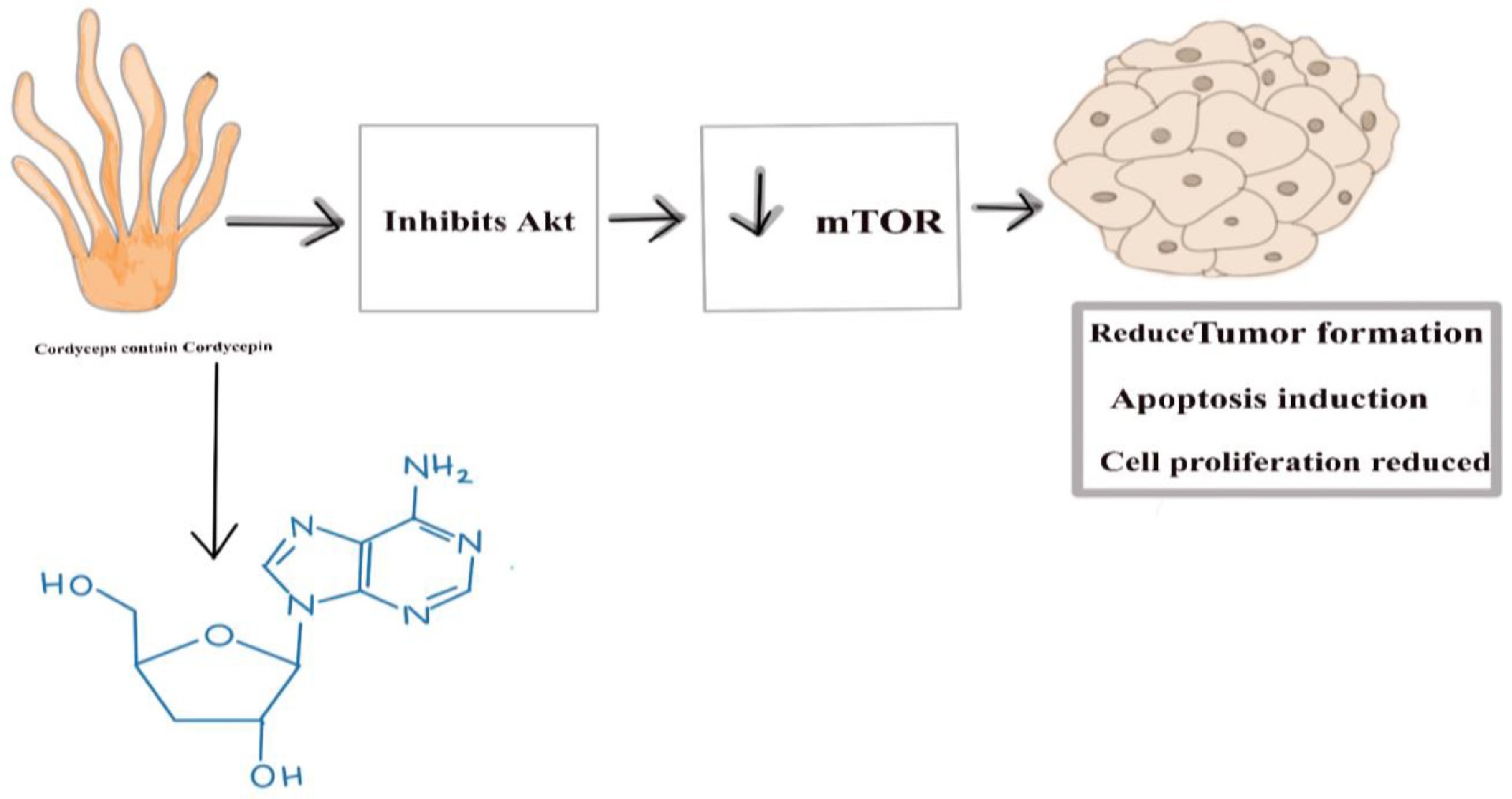

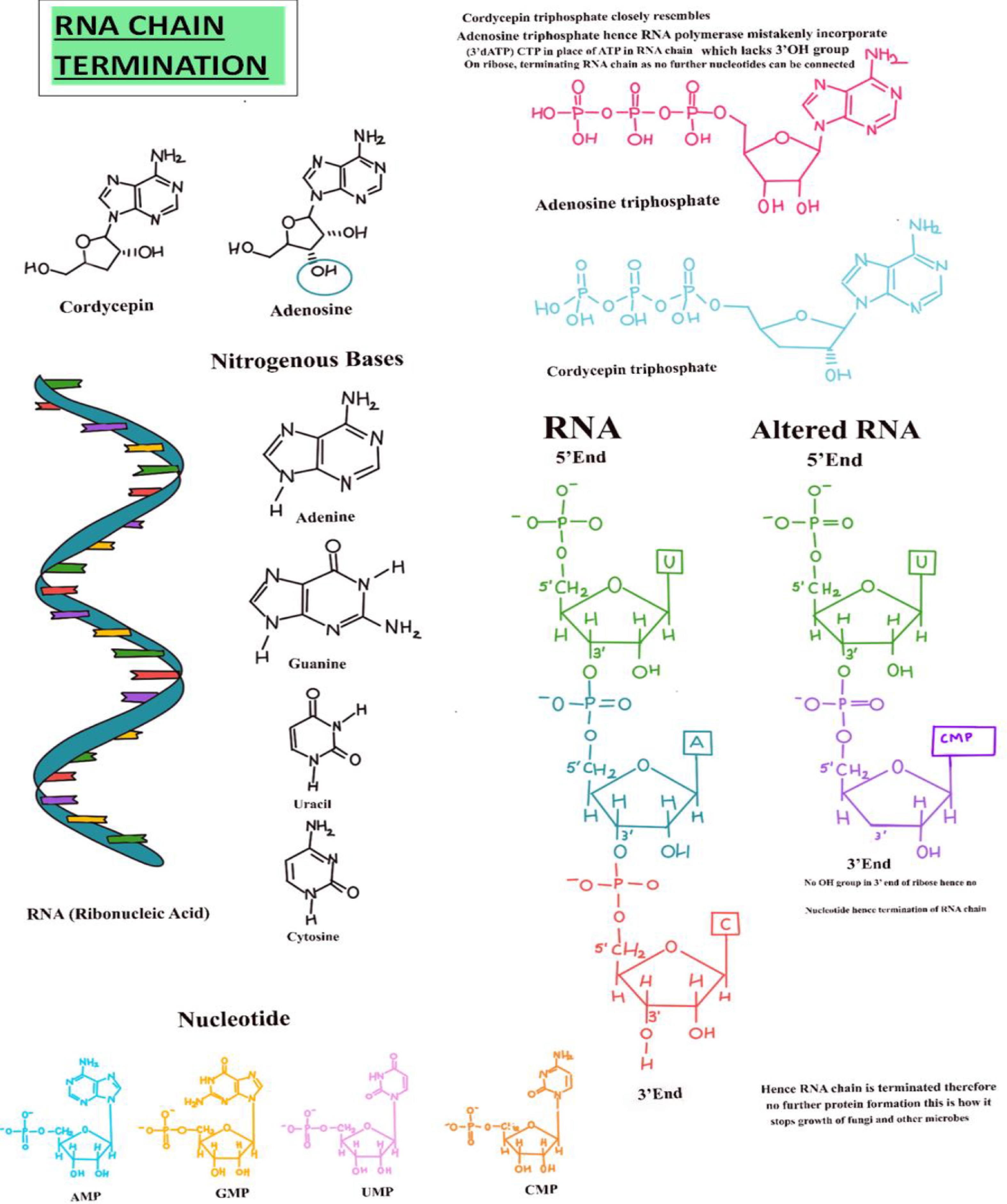

Cordycepin (3'-deoxyadenosine) is a nucleoside analog structurally like adenosine, distinguished by the absence of a hydroxyl (-OH) group at the 3' position of its ribose sugar. Once inside the cell, cordycepin undergoes phosphorylation by cellular kinases, transforming it into its active triphosphate form, 3'-deoxyadenosine triphosphate (3'-dATP). This active form is structurally like adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the standard substrate for RNA polymerase during transcription. During RNA synthesis, RNA polymerase incorporates nucleotide triphosphates into the growing RNA strand. When 3'-dATP is present, RNA polymerase may mistakenly incorporate it into the RNA chain in place of ATP due to their structural similarity. This incorporation involves the cleavage of the two terminal phosphate groups (pyrophosphate) from 3'-dATP, resulting in the addition of cordycepin monophosphate (3'-dAMP) to the 3' end of the RNA strand. However, unlike the regular adenosine monophosphate (AMP), 3'-dAMP lacks the critical 3'-OH group necessary for forming the subsequent phosphodiester bond with the next nucleotide. The absence of this hydroxyl group prevents the addition of further nucleotides, effectively terminating RNA chain elongation prematurely (Figs. 3 and 4). This mechanism disrupts normal RNA synthesis, leading to the inhibition of mRNA production and, consequently, protein synthesis within the cell[51]. This inhibition of the RNA chain also prevents the growth of microbes, as no protein formation takes place. Along with the termination of the RNA chain, cordycepin inhibits Protein Kinase B (Akt) phosphorylation, thereby inactivating Akt. Since Akt activates mammalian targeting of rapamycin (mTOR), its inhibition leads to mTOR downregulation. mTOR controls cell growth, protein synthesis, and survival. The final result is reduced cell proliferation, increased apoptosis, and suppressed tumor growth[52].

-

Cordymin, a peptide derived from C. militaris, has shown promising antiviral and antifungal properties in in vitro studies. It effectively inhibited the growth of various fungi, including Bipolaris maydis and Candida albicans, and suppressed HIV reverse transcriptase. Numerous studies have confirmed its anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects. Furthermore, methanolic extracts from the fruiting bodies and fermented mycelia of C. militaris exhibit potent antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Research indicates that cordycepin and its derivatives possess antiviral effects against several viral strains, including dengue virus[53], enterovirus A71[54], HIV[55], herpes simplex virus, epstein barr virus[56], and influenza virus[57]. The antiviral mechanism of cordycepin is linked to its ability to inhibit viral RNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase[58]. In silico analyses have revealed significant interactions between cordycepin and SARS-CoV-2, particularly with the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein and the major protease. Its capacity to restrict viral replication aligns with its anti-SARS-CoV-2 actions[59], and further investigations suggest that cordycepin can inhibit the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of SARS-CoV-2[60].

-

The primary natural hosts of C. militaris are lepidopteran larvae (caterpillars) and pupae, with less common hosts including coleopteran, hymenopteran, and dipteran insects. Lepidopteran hosts are classified into 12 distinct families. Other hosts from different orders include Ips sexdentatus, Lachnosterna quercina, and Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera), Cimbex similis (Hymenoptera), and Tipula paludosa (Diptera). Additionally, over 25 species of higher heteroceriid lepidopterans and unidentified hymenopteran species have recently been identified as hosts for C. militaris. Research on the artificial cultivation and stroma production of C. militaris has been conducted using various insect pupae and larvae, with the silkworm Bombyx mori being the most frequently utilized. Other insects employed for artificial stroma production include Antherea pernyi, Mamestra brassicae, Tenebrio molitor, Ostrinia nubilalis, Heliothis virescens, H. zea, Spodoptera frugiperda, Andraca bipunctata, Philosamia cynthia, Spodoptera litura, and Clanis bilineata. The Daeseungjam variety has been identified as the most effective for stroma formation of C. militaris[61]. Cordyceps militaris primarily targets the larvae of Lepidoptera, commonly known as caterpillars. The infection process initiates when the spores of C. militaris, either conidia or ascospores, settle on the cuticle of a compatible insect host. These spores possess adhesive properties, allowing them to stick to the insect's surface with ease. Under favorable environmental conditions, such as adequate moisture and temperature, the spores germinate and form an appressorium, which is the organ of attachment which then initiates the infection peg. The infection peg penetrates the insect's exoskeleton by exerting mechanical pressure and utilizing enzymes like chitinases and proteases that break down the cuticle. Once inside, it differentiates into hyphae, which are thread-like structures of the fungus and helps in the absorption of the nutrients from the host. The fungus invades the insect's hemocoel, or body cavity, and thrives by consuming the host's tissues. It also employs various secondary metabolites to evade or suppress the insect's immune system, leading to the mummification of the insect (Fig. 5). Following the mummification process, C. militaris develops a fruiting body, characterized by its orange club-like shape, which protrudes from the cadaver of the insect, usually from the head or thorax. These fruiting bodies generate and release new spores into the environment, facilitating the infection of additional hosts[7].

-

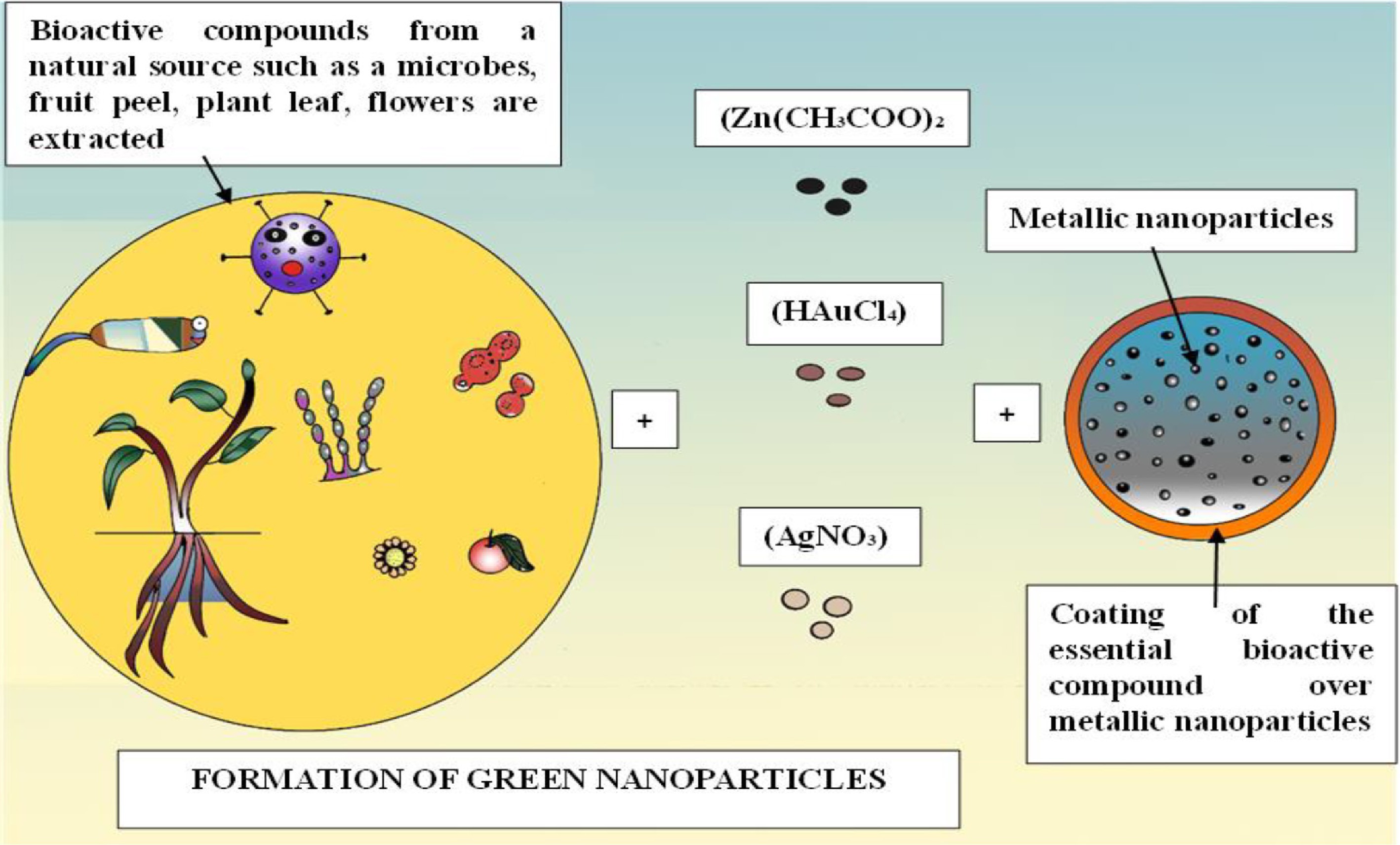

Due to their antimicrobial properties, C. militaris can be utilized to produce environmentally friendly nanoparticles that serve as a biological control mechanism against plant pathogens, thereby safeguarding plants from diseases. Nanoparticles are minuscule materials measuring between 1 and 100 nm and can be classified into various categories, including metal nanoparticles such as silver and gold, metal oxides like zinc oxide and titanium dioxide, carbon-based nanoparticles including fullerenes and nanotubes, as well as polymeric and lipid-based nanoparticles. Additionally, these nanoparticles can be categorized based on their origin (natural or synthetic), composition (inorganic, organic, or hybrid), shape (spherical, rod-like, etc.), and dimensionality (0D, 1D, 2D, or 3D structures)[62]. Among the different types, green nanoparticles have gained attention as a viable alternative due to their eco-friendly synthesis methods. These nanoparticles are produced using biological resources such as plant extracts, microorganisms (including bacteria and fungi), algae, or agricultural waste. These natural materials function as reducing and stabilizing agents, thereby eliminating the necessity for toxic chemicals and high-energy inputs typically associated with conventional chemical synthesis techniques. Green nanoparticles are regarded as more advantageous than traditionally synthesized nanoparticles for various reasons. They are non-toxic, biodegradable, biocompatible, and created through sustainable practices, making them particularly ideal for use in medicine, agriculture, and environmental cleanup[13]. Additionally, their production costs are considerably lower since green synthesis employs plentiful and renewable biological materials, often derived from waste (Fig. 6). The process of creating green nanoparticles generally involves extracting bioactive compounds from natural sources like plant leaves or fruit peels, which are then combined with a metal salt solution. These natural compounds facilitate the reduction of metal ions to form nanoparticles while also stabilizing them. The final nanoparticles are purified through methods such as filtration or centrifugation. This straightforward, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly approach aligns with the principles of green chemistry and presents a promising avenue for future applications in nanotechnology[14].

-

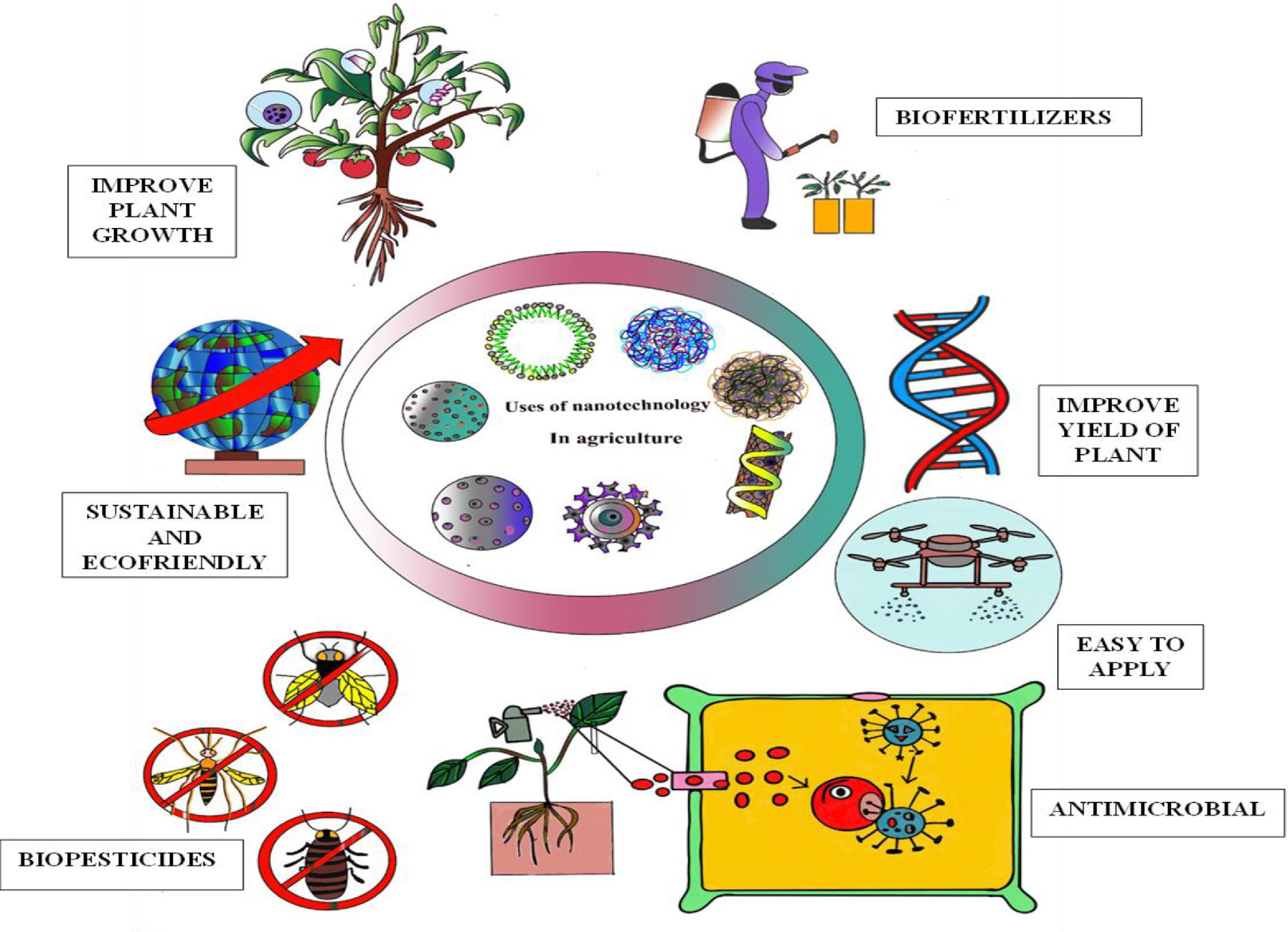

Eco-friendly green nanoparticles, produced through biological methods utilizing plant extracts, microbes, or fungi, are crucial for advancing sustainable agriculture. Unlike traditional chemical nanoparticles, these green alternatives are safe for the environment, biodegradable, and less toxic, thereby decreasing the ecological impact of agricultural practices. They improve crop yields by the target delivery of the nutrients and agrochemicals, which reduces losses from leaching or volatilization, and enhances resource efficiency (Fig. 7). In managing pests and diseases, green nanoparticles possess antimicrobial and insecticidal properties, providing a safer substitute for synthetic pesticides and lowering the risk of resistance. Their controlled-release characteristics ensure lasting effectiveness, which minimizes the need for frequent applications and reduces overall costs. Furthermore, these nanoparticles support soil remediation by neutralizing contaminants and boosting soil microbial activity. By fostering plant growth, enhancing stress resilience, and increasing yields while limiting environmental damage, green nanoparticles support sustainable agricultural practices and contribute to long-term food security and environmental protection[63].

-

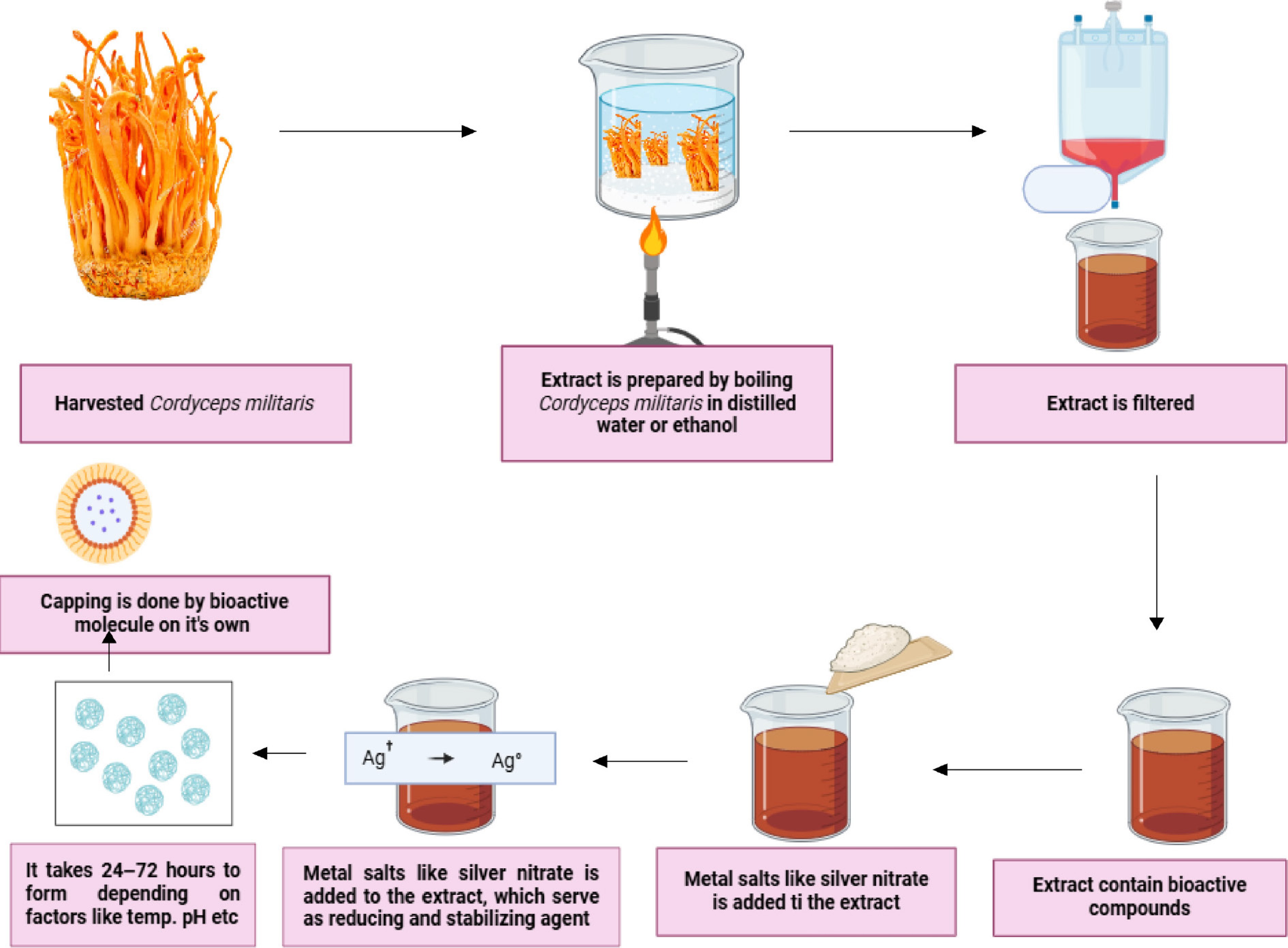

Fresh C. militaris mushroom was harvested, cleaned, and kept in a tray-drier at 45 °C for 24 h to completely remove the moisture. Dried mushroom was powdered using a mixer grinder and sieved through a 600 mm sieve. Then kept in a deep freezer at −20 °C. The refrigerated sample was procured and 10 g measured. 100 ml methanol was also taken in a beaker. To prepare for extraction via Soxhlet apparatus the sample was kept in a Whatman No.1 filter paper covered with a cotton and kept in the glass tube. Extraction was carried out with methanol as the extractant for 3−5 h. After 3−5 h the extractant was boiled to obtain the mushroom extract, which was then transferred to 4 ml sample tubes, and kept in the refrigerator at 4 °C[15]. The other process was that fine powder of dried mushroom (10 g) was stirred with 100 ml of Milli-Q (Millipore, USA) water at room temperature, at 150 rpm for 24 h and filtered through Whatman No. 4 paper. The liquid extract was evaporated at 35 °C by vacuum distillation, and stored at 4 °C for further analysis. The resultant filtrate extract of mushroom was used for the synthesis of silver, gold, or zinc nanoparticles. The mushroom extract was mixed with an aqueous solution of 2 mM AgNO3 (in general 1:10 parts of extract and metal solution taken), and kept at room temperature under dark conditions for 24–96 h[64]. The change of colour started within 5 h from colourless to reddish brown in the presence of AgNO3. The solution was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min to collect the nanoparticles (Fig. 8). The nanoparticles were then washed with distilled water 2–3 times to remove unreacted materials. The collected nanoparticles were then air-dried or a simple oven at 40 °C was used for a few hours, or the sample was freeze dried using a lyophilizer, and then stored in a freezer until further use.

-

The analysis of nanoparticles employs sophisticated methods such as ATR-FTIR, SEM, and DLS to evaluate their chemical and physical characteristics. Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR), is utilized to ascertain the functional groups and surface chemistry of nanoparticles by examining their infrared absorption spectra. This technique requires the sample to be in contact with an internal reflection crystal, where an infrared beam produces an evanescent wave that penetrates a few micrometers into the sample, enabling the detection of molecular vibrations. For optimal analysis, the ATR crystal must possess a significantly higher refractive index than the sample to facilitate total internal reflection (TIR) within the crystal. TIR is crucial for generating the evanescent wave that interacts with the sample's surface. The spectral range typically spans from 4,000 to 400 cm−1 (mid-infrared), although some instruments may extend from 6,000 cm−1 (near-infrared) down to 50 cm−1 (far-infrared), depending on the sample and equipment specifications. A standard resolution of 4 cm−1 is commonly used for general characterization, while higher resolutions (2 or 1 cm−1) are employed for identifying fine spectral features, and lower resolutions (8 or 16 cm−1) are utilized for rapid scans. The selection of the ATR crystal is contingent upon the sample type: diamond (refractive index 2.4) is preferred for hard materials due to its robustness and extensive spectral range (45,000–10 cm−1), zinc selenide (n = 2.4) is more appropriate for general or softer samples with a broader spectral range than germanium, and germanium (n = 4.0) is best suited for high-refractive index samples. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) is employed to analyze the surface morphology and topography of nanoparticles. For the SEM analysis, freeze-dried silver nanoparticles were re-suspended in distilled water, applied to a glass slide, dried, and then coated with platinum to enhance surface conductivity. Imaging was performed under high vacuum conditions (10−5 torr) with an accelerating voltage ranging from 10 to 20 kV. Additionally, Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) was utilized to assess the hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential of the nanoparticles, which is based on light scattering resulting from Brownian motion. The measurements were carried out using a Malvern Zetasizer after diluting the lyophilized sample tenfold in phosphate-buffered saline (0.15 M, pH 7.2), with readings taken at a scattering angle of 90° at 25 °C. These integrated techniques provide comprehensive insights into the structure, size distribution, surface chemistry, and stability of nanoparticles[64].

-

Cordyceps militaris, a medicinal fungus known for its entomopathogenic properties, has emerged as a versatile biological agent in sustainable agriculture, functioning as a bioherbicide, biopesticide, fungicide, bactericide, and nematicide. Its efficacy is largely due to its diverse range of secondary metabolites, especially cordycepin (3′-deoxyadenosine), and its capacity to facilitate the green synthesis of metal nanoparticles like silver (AgNPs), zinc oxide (ZnONPs), and gold (AuNPs), which further bolster its antimicrobial and pesticidal properties[7, 13]. As a bioherbicide, C. militaris utilizes cordycepin as an allelochemical that mimics adenosine, disrupting RNA synthesis in competing plant species and consequently inhibiting cell division and protein synthesis. It also affects the electron transport chain and antioxidant defense mechanisms in plant cells, resulting in oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation, and inhibition of photosynthesis. In radish (Raphanus sativus) seedlings, cordycepin at a concentration of 0.04 mg/mL was shown to decrease seed germination and shoot/root elongation by 3.3 to 3.7 times more effectively than glyphosate, by reducing chlorophyll and carotenoid levels, increasing malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations, and causing electrolyte leakage, all of which are signs of membrane damage and ROS-induced cellular death[65]. Cordyceps militaris exhibits strong antifungal properties against Alternaria alternata, Fusarium solani, and Rhizoctonia solani, which were isolated from infected Withania somnifera plants[66]. The methanolic extracts of C. militaris, rich in cordycepin, flavonoids, and phenolic acids, effectively inhibited mycelial growth and spore germination through various mechanisms, including disruption of DNA/RNA synthesis, increased membrane permeability, induction of oxidative stress, and apoptosis-like death of hyphae. Scanning electron microscopy showed signs of hyphal deformation, collapse, and cytoplasmic leakage. Additionally, green-synthesized silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), and zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) further boosted antifungal efficacy by penetrating fungal cell walls, producing intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), and damaging organelles. As a bactericide, nanoparticles derived from C. militaris and cordycepin exhibit broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against pathogens like Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. These substances disrupt bacterial cell membranes, interfere with peptidoglycan biosynthesis, inhibit DNA replication, and generate ROS, resulting in metabolic arrest and cell[14, 67]. In addition to C. militaris, a variety of other mushrooms have been investigated for their ability to green synthesize nanoparticles that display significant antimicrobial properties. For example, the medicinal fungus Ganoderma lucidum has been utilized to generate silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) by reducing silver ions with fungal mycelial extracts. The resulting biosynthesized AgNPs exhibited considerable antibacterial and antifungal activities against several pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Candida albicans[68]. Likewise, Ganoderma applanatum has been employed for the biosynthesis of AgNPs, which showed strong antimicrobial effects against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, emphasizing its potential as a source of environmentally friendly antimicrobial agents[69]. Furthermore, Agaricus bisporus, commonly referred to as the white button mushroom, has been used to produce silver nanoparticles that effectively inhibit foodborne bacterial pathogens, highlighting its relevance in food safety[70]. Additionally, Termitomyces spp., recognized for their symbiotic association with termites, have been investigated for the biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles. These nanoparticles demonstrated antimicrobial properties against various bacterial strains, indicating the potential of Termitomyces as a sustainable source for nanoparticle production[71]. These instances exemplify the broad potential of mushroom-mediated nanoparticle synthesis as a sustainable method for developing antimicrobial agents. As a biopesticide, C. militaris infects insect hosts by penetrating their cuticles and proliferating within the hemocoel. Cordycepin inhibits insect immune responses[72] by downregulating genes involved in the prophenoloxidase cascade and antimicrobial peptides. Insects such as Galleria mellonella[73], Plutella xylostella[74], and Leptinotarsa decemlineata[75], etc., experience delayed development, reduced reproductive success, and increased mortality rates. Furthermore, green-synthesized nanoparticles exhibit direct cytotoxic effects on gut epithelial cells, hindering nutrient absorption and metabolic functions. Cordyceps militaris also serves as an effective nematicide, demonstrating notable efficacy against plant-parasitic nematodes, primarily due to the metabolite cephalolidedifuran A, which is derived from a hybrid of C. militaris and C. cicadae. This macrolide functions by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase (AChE), leading to an accumulation of acetylcholine at neural synapses. This accumulation results in hyperexcitation, paralysis, and ultimately the death of nematodes such as Panagrellus redivivus. Beyond its neurotoxic effects, cephalolidedifuran A also interferes with mitochondrial respiration, disrupting the proton gradient across the mitochondrial membrane, which hinders ATP production and causes oxidative damage. Nematodes treated with this compound display decreased mobility, vacuolation, shrunken cuticles, and tissue necrosis, thereby confirming both neurotoxic and metabolic action modes[76]. These mechanisms, along with the environmentally friendly characteristics of fungal metabolites and green nanotechnology, position C. militaris as a promising option for comprehensive and sustainable pest and disease management in agricultural practices[7].

-

Looking forward, the application of C. militaris, along with its green-nanoparticle formulations in agriculture offers a highly promising opportunity. This strategy has the potential to integrate sustainable crop protection methods with advanced nanobiotechnology and metabolomics, facilitating the precise adjustment of nanoparticle synthesis for enhanced stability, targeted delivery, and controlled release of biocides and bioactives. Nevertheless, to convert this potential into practical application, several critical gaps must be addressed. Firstly, the green synthesis processes require standardization and optimization—existing variability in extract composition, reaction parameters, and nanoparticle properties (size, shape, stability) obstructs reproducibility and scalability. Secondly, the mechanistic understanding of how biomolecules facilitate reduction, capping, and stabilization remains inadequate, complicating the design of engineered systems with predictable results. Thirdly, while green-synthesized nanoparticles are more economical and environmentally friendly compared to traditional chemical or physical methods—due to the utilization of renewable bio-resources, reduced energy consumption, and minimal toxic waste—there are still considerable cost barriers related to purification, stabilization, formulation, and large-scale production. Fourthly, for agricultural application, the integration into precision agriculture platforms, seed coatings, nano-carriers, and synergistic formulations with beneficial microbes or biocontrol agents will be vital to expand the spectrum of pests and diseases addressed, as well as to ensure efficacy in the field and compliance with regulations. Lastly, achieving cost-effective production of metabolism-enhanced strains (for instance, through genetic engineering to increase key metabolites such as cordycepin), and fostering public and farmer awareness alongside regulatory frameworks will be crucial for widespread adoption. Overall, the future is centered on enhancing green-nanoparticle systems derived from C. militaris, transitioning from laboratory-scale proof-of-concepts to practical field-scale applications, guaranteeing reproducibility and cost-effectiveness, integrating them into precision agriculture frameworks, and ensuring preparedness in regulatory, manufacturing, and societal aspects.

-

The combination of C. militaris and its metabolite-enhanced green nanoparticles presents a sustainable, eco-friendly, and biologically effective alternative to synthetic agrochemicals in contemporary agriculture. The biosynthesized silver, gold, and zinc oxide nanoparticles, facilitated by C. militaris extracts, create a green nanotechnology platform that improves the efficacy of pesticides, fungicides, bactericides, herbicides, and nematicides without leaving chemical residues in the environment. These nanoparticles operate through multiple mechanisms, such as disrupting cell walls, inducing oxidative stress, interfering with nucleic acid synthesis, and inhibiting metabolism across various pathogens and pests. Notably, this environmentally compatible method reduces non-target toxicity, enhances soil and plant health, and supports integrated pest and disease management strategies. With the increasing global demand for residue-free and sustainable crop protection methods, green nanoparticles derived from C. militaris emerge as a valuable bioresource for promoting environmentally friendly and resilient agricultural practices.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Makhija M: literature survey and writing - original draft; Archana TS: conceptualization and reviewing. Kumar D: reviewing, writing and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

No datasets were generated or analyzed during this study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Makhija M, Archana TS, Kumar D. 2026. Multifaceted biocidal activities of Cordyceps militaris and synthesis of green nanoparticles: a comprehensive review. Studies in Fungi 11: e001 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0034

Multifaceted biocidal activities of Cordyceps militaris and synthesis of green nanoparticles: a comprehensive review

- Received: 02 August 2025

- Revised: 10 November 2025

- Accepted: 13 November 2025

- Published online: 14 January 2026

Abstract: An innovative green technology for improving sustainable agricultural practices involves utilizing Cordyceps spp. to generate nanoparticles (NPs). The entomopathogenic fungus Cordyceps has garnered significant interest due to its capability to facilitate the environmentally friendly production of metallic nanoparticles, including silver (AgNPs) and gold (AuNPs), as well as other nanostructures. This biological approach effectively avoids the health and environmental risks associated with traditional chemical synthesis. The nanoparticles derived from Cordyceps spp. serve as efficient biocontrol agents due to their distinctive physicochemical characteristics. These Cordyceps-based nanoparticles possess bactericidal, fungicidal, herbicidal, insecticidal, and nematicidal properties, which are crucial for their biocontrol effectiveness, as they provide protection to crops against detrimental microbes such as Aspergillus and Fusarium, and bacterial wilt pathogens, as well as competitive weeds, destructive insects like Plutella xylostella, and devastating nematodes. Their ability to disrupt microbial cell walls and biofilms further enhances their role as biological pesticides. The multifunctional nature of nanoparticles produced by Cordyceps presents a holistic approach to decreasing reliance on synthetic fertilizers and chemical pesticides. By fostering sustainable agricultural practices, they contribute to soil health, environmental preservation, and increased crop yields. This paper emphasizes the significance of green nanoparticles synthesized from Cordyceps militaris and their potential to revolutionize sustainable agriculture through the development of eco-friendly biocontrol solutions.

-

Key words:

- Entomopathogenic /

- Integrated pest management /

- Sustainable /

- Bioherbicide /

- Nematicide /

- Fungicide