-

Biochar is a charcoal-like substance, which is a lightweight black residue, highly porous with a relatively large surface area, and often fine-grained when applied (Chen et al., 2019). It is produced by burning biomass, such as crop or forest residues, in an oxygen-limited environment – a process called pyrolysis. During pyrolysis, the unstable carbon in the biomass is mostly converted into a stable form of carbon that is then stored in the biochar (Mašek et al., 2013). Due to the high temperature and low oxygen environment during pyrolysis, biochar contains high levels of carbon and low levels of hydrogen and oxygen, making it resistant to biodegradation (Schmidt & Noack, 2000). Thus, converting waste biomass into biochar is regarded as a potential carbon-negative process, likely contributing to carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere (Wu et al., 2019).

HTML

-

Adding biochar to the soil has been identified by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as one of the most cost-effective and environmentally friendly solutions towards managing soils as carbon sinks (Masson-Delmotte et al., 2019). While biochar is not in itself a fertilizer, its porous structure and large surface area allow it to absorb up to five times its weight in nutrients and water, which enhances plant productivity and soil health for more soil organic carbon sequestration (Lehmann & Joseph, 2015). When biochar is added to soil, it stores carbon in a secure condition for decades, hundreds or even thousands of years since biochar is biologically non-attackable (Lehmann et al., 2015). Despite the fact that biochar addition is one of the most promising technologies for enhancing soil organic carbon storage, the effects of biochar addition on soil organic carbon storage vary across different temporal and spatial scales, limiting the evaluation and prediction of soil organic carbon storage over various ecosystem types (Liu et al., 2016; Schmidt et al., 2021; Han et al., 2022). For example, biochar addition decreased soil organic carbon decomposition within one year in both Alfisol and Andisol (Herath et al., 2014), while it tended to increase recalcitrant soil organic carbon decomposition after seven years of continuous application in an alluvial soil (Sun et al., 2021). To apply biochar technology over large areas, we need to better understand the effects and underlying mechanisms of biochar addition on soil organic carbon storage across various ecosystems.

Recent studies have shown that soil microorganisms play crucial roles in determining the direction and magnitude of the effects of biochar addition on soil organic carbon storage (Zhang et al., 2018; Sarfraz et al., 2019). For example, biochar-induced shifts in soil microorganisms can enhance plant nutrient acquisition, improve stress tolerance, and reduce soil organic matter decomposition (Liu et al., 2024). However, since a spoonful of soil contains billions of microorganisms, the task of linking the dynamics of specific soil microorganisms with soil organic carbon dynamics is daunting, especially when considering the intricate interactions between plants and soil microorganisms (Lehmann et al., 2015). For example, there was no significant relationship between the abundance of functional genes and the soil organic carbon decomposition in fertilized farmland (Wood et al., 2015). Therefore, it remains challenging to establish direct linkages between the specific soil microorganisms and soil organic carbon cycling (Chen & Sinsabaugh, 2021).

-

Soil extracellular enzymes are produced by plant roots and microorganisms to break down organic matter and acquire nutrients and energy in the soil. Plant roots and soil microorganisms preferentially invest metabolic resources for extracellular enzyme production to acquire nutrients that are limiting their growth and proliferation (Chen et al., 2018b). Soil extracellular enzymes catalyze the decomposition of soil organic matter, which deconstruct plant and microbial residues and break down large macromolecules into simple molecules. Furthermore, extracellular enzymes are basically proteins, and their production is carbon-, nitrogen- and energy-costly, having crucial direct and indirect effects on soil organic carbon cycling (Chen et al., 2018b; Chen et al., 2020; Gunina & Kuzyakov, 2022). Thus, these enzymes will likely provide us with a novel window for understanding the intricate nature of plant-soil-microbial feedback.

Various kinds of extracellular enzymes are synthesized to target the decomposition of different soil organic carbon pools, including ligninase (e.g. phenol oxidase and peroxidase) targeting structural complex macromolecules and cellulase (e.g., β-1,4-Glucosidase and α-1,4-glucosidase) degrading simple micro-molecules (Margida et al., 2020). For example, several recent studies have found that cellulase and ligninase responded differently to experimental warming (Chen et al., 2018a), enhanced nitrogen deposition (Chen et al., 2017), altered precipitation (Ren et al., 2017), and natural forest conversion (Xu et al., 2020). The activities of these enzymes can serve as indicators for monitoring the decomposition of different soil organic carbon pools. Therefore, an improved understanding of these extracellular enzymes, particularly, cellulase and ligninase, will help advance the mechanistic understanding of microbially mediated soil organic carbon cycling.

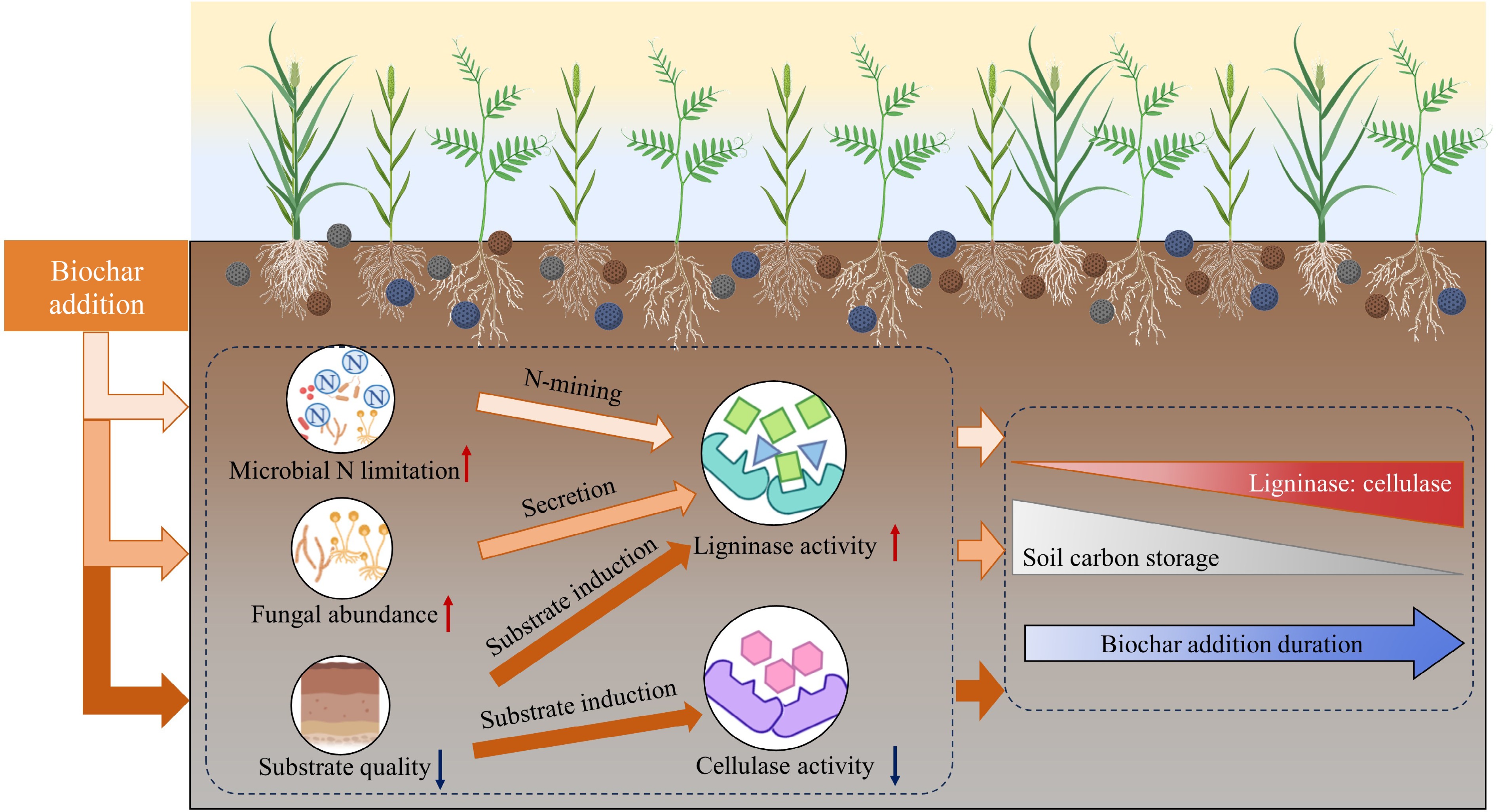

Biochar addition may have differential impacts on cellulase and ligninase activities because of variations in the chemical composition of soil organic matter and shifts in microbial community structure resulting from biochar addition (Muhammad et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018). For instance, the condensation of cellulose and hemicellulose into humic-like macromolecules on the surface of biochar could induce the secretion of ligninase but suppress cellulase activity, as enzyme-catalyzed reactions are commonly assumed to follow the Michaelis-Menten mechanism (German et al., 2012). This shift in carbon-degrading enzyme activity may have substantial but understudied effects on soil organic carbon storage following biochar addition. Although some recent studies indicated that soil organic carbon storage can vary significantly with biochar addition duration, biochar production conditions, and site-specific conditions (e.g. climate and soil as well as plant/crop properties), the comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms remains largely underexplored (Zhang et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2023). In particular, direct evidence is lacking on biochar-induced changes in key soil extracellular enzymes (e.g. cellulase and ligninase), as well as the implications for the long-term performance of biochar on soil organic carbon storage across wide environmental gradients.

To explore the links between soil extracellular enzyme and soil organic carbon storage under biochar addition, Feng et al. (2023) built a global database with more than 900 observations on the effects of biochar addition on soil organic carbon storage and soil extracellular enzyme activity across different ecosystems (Fig. 1). In their analysis, biochar addition increased the extracellular enzyme activity targeting the degradation of complex carbon macromolecules and suppressed the extracellular enzyme activity targeting the decomposition of readily decomposable carbon compounds. The contrasting responses of extracellular enzymes targeting the decomposition of different soil organic carbon pools accounted for the majority of variations of changes in soil organic carbon storage across various climatic and edaphic regions (Feng et al., 2023). Due to the shifts in plant and microbial enzyme production over time with biochar addition, long-term biochar addition had a smaller positive effect on soil organic carbon storage compared to short-term biochar addition. Their results indicate that biochar addition is likely effective for short-term soil organic carbon storage. However, in the long term, more carbon compounds are broken down and released than previously estimated due to the significant increase in enzyme activity targeting the decomposition of relatively recalcitrant carbon pools, leading to lower soil organic carbon storage capacity with long-term biochar addition (Du et al., 2014; Suman et al., 2018). Previous studies may have overestimated soil organic carbon storage capacity with long-term biochar addition if they did not consider changes in soil microorganisms and extracellular enzymes over time.

-

Shifts in soil extracellular enzyme activity alone cannot fully account for the variations in soil organic carbon sequestration since the net change in soil organic carbon storage is determined by the balance of carbon inputs and outputs. Vegetation-derived carbon inputs can directly contribute to soil organic carbon formation through rhizo-deposition of diverse compounds, including low molecular weight compounds, while these processes were independent of microbial and enzymatic transformations (Liang et al., 2017; Xiong et al., 2021). Thus, changes in soil extracellular enzyme activity may advance the mechanistic understanding of soil organic carbon decomposition rather than revealing the full picture of soil organic carbon dynamics. To further clarify soil organic carbon dynamics, more research on the carbon input and output processes is needed.

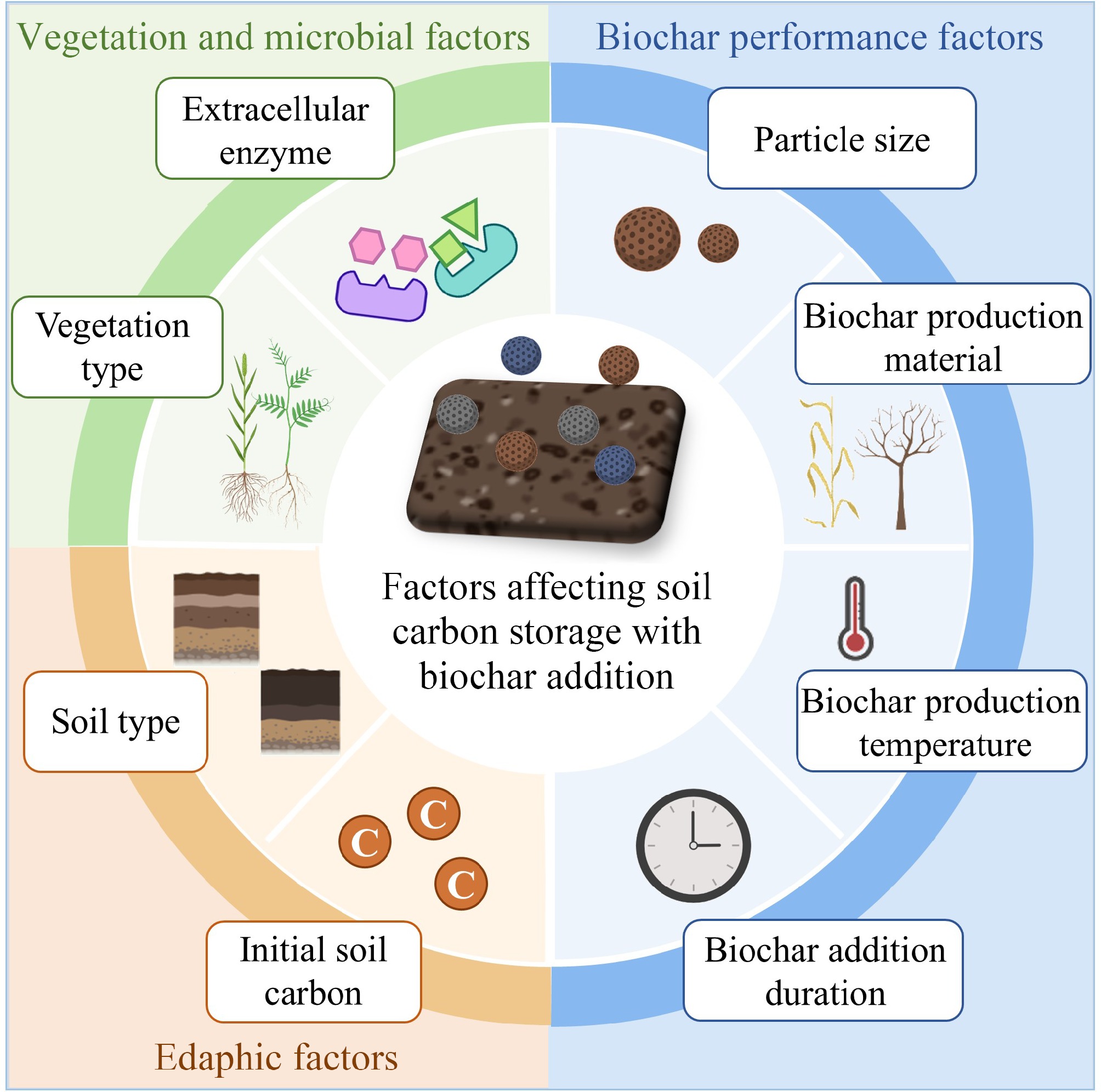

There are many variables that can potentially affect the biochar performance on soil organic carbon storage, including the selected raw organic material, pyrolysis temperature and residence time in pyrolysis flow (Fig. 2). For example, biochar produced at higher temperatures commonly has a larger degree of recalcitrance than biochar produced at lower temperatures (Zhang et al., 2015). Meanwhile, biochar made from wood fibers is likely to have a higher degree of aromaticity than biochar derived from crop residues (Weber & Quicker, 2018). In addition, a range of other factors can affect the direction and magnitude of the impact of adding biochar on soil organic carbon storage, including soil type, vegetation type, and initial soil organic carbon content (Maillard & Angers, 2014; Tian et al., 2015) (Fig. 2). Furthermore, these above-mentioned variables will likely have interactive effects on the biochar-induced changes in soil organic carbon dynamics. It will, therefore, be challenging to give universal suggestions for future biochar management strategies since the performance of biochar will likely depend on a range of variables relevant to climatic, edaphic, environmental and biochar production procedures. It becomes even more complex if the interactions between these variables are considered. These divergent impacts suggest that there will be a large potential to improve the role of biochar on soil organic carbon storage if we can better understand the interactive effects of biochar properties in relation to the surrounding environmental factors.

In addition to soil organic carbon storage, biochar is beneficial to soil health by modifying a range of soil physiochemical properties. For example, biochar addition can alleviate soil acidification, increase soil cation exchange capacity, enhance soil water holding capacity and nutrient availability, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions (Weber & Quicker, 2018). Considering these advantages, biochar addition can also increase crop yield, representing a potential win-win strategy to meet the dual challenges of climate mitigation and food security facing the current cropping systems (Xiang et al., 2017; Nan et al., 2022; Xia et al., 2024). In addition, biochar is also recommended as a cost-effective solution for ameliorating soil and water pollution. Taken together, biochar technology indicates a promising future in mitigating climate change, improving food security, improving soil physiochemical properties, recycling organic waste, and producing clean energy. From this standpoint, biochar technology should be added to the global climate change toolkit of carbon-negative, energy-saving, and renewable options (Lorenz & Lal, 2015; Smith, 2016). With the worldwide application of biochar across different ecosystems, it will be possible to lower the cost of biochar production. Given the wide range of expertise required, extensive interdisciplinary collaborations between engineers, agronomists, microbiologists, and data analysts are urgently needed.

-

Several implications were proposed for investigating soil organic carbon storage with biochar addition in future. First, the contrasting responses of cellulase and ligninase to biochar addition revealed distinct microbial nutrient acquisition strategies that regulate soil organic carbon storage. However, establishing mechanistic linkages between carbon-degrading enzyme activities and microbial community structure and diversity remains challenging. Thus, the necessity for future studies is emphasized to employ novel methodologies such as advanced genomic sequencing and probe-based techniques to improve understanding of microbial controls on soil organic carbon storage with biochar addition. Second, current models for predicting biochar-induced carbon sequestration exhibit substantial discrepancies (Lehmann et al., 2021). These uncertainties likely stem from variations in representations of soil carbon mineralization processes and simulated temporal scales. Thus, we propose integrating enzyme-mediated catalytic processes of fast- versus slow-cycling organic carbon fractions into biochar models (Chen et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2022) rather than treating soil carbon mineralization as a first-order reaction (Woolf & Lehmann, 2012). This advancement would enhance realism in modeling mineralization processes. In addition, incorporating temporal dynamics of extracellular enzyme activities could substantially improve model predictions of biochar-induced carbon sequestration. Thus, expanded datasets documenting extracellular enzyme activities and soil organic carbon dynamics across diverse ecosystems and temporal scales under biochar addition are strongly encouraged. Such multidimensional data would enable parameter optimization and ultimately strengthen model robustness in predicting soil organic carbon (Luo & Schuur, 2020).

This study is granted by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42361144886) and the Shaanxi Province Natural Science Foundation for Distinguished Young Scholar (Grant No. 2024JC-JCQN-32).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Chen J, Zhou J, Smith P, Pan G; draft manuscript preparation: Chen J (lead), Zhou J, Smith P, Pan G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Chen J, Zhou J, Smith P, Pan G. 2025. Soil organic carbon storage from biochar addition falls over time: a perspective of shifts in soil extracellular enzyme activity. Soil Science and Environment 4: e002 doi: 10.48130/sse-0025-0001 |