-

Dry peas (Pisum sativum L.), one of the most important leguminous crops, are the second most cultivated grain legume in the world, following dry beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), with production exceeding 16.2 million metric tons globally[1]. Dry peas contains high levels of protein, minerals, and vitamins and is mostly consumed fresh as a vegetable or processed as dry-shelled products for human and livestock[2,3]. Being a legume species, dry peas can fix approximately 50–150 kg nitrogen·ha−1·year−1 to the soil through symbiotic nitrogen fixation[4]. Furthermore, growing dry peas, particularly when integrated into crop rotation, can improve soil microbial biodiversity and soil fertility, increase soil organic carbon levels, improve water retention, and break disease cycles[5], thereby contributing to sustainable agriculture.

Pea is sensitive to soil salinity, a common problem in the Northern Great Plains (including North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Minnesota), a leading area of pea production in the U.S.[6,7]. Salinity causes osmotic stress (inhibition of water absorption), ionic toxicity (toxic effect of high ions such as Na+), and nutrient imbalance in plants, leading to reduced crop growth and yield[8]. For example, studies have shown that salinity reduces seed germination, inhibits plant growth, and increases sodium content in field peas[9−12]. In these researches, chloride salts (e.g. NaCl) were used to induce salinity stress; however, in the Northern Great Plains, sulfate salts (e.g, Na2SO4) are dominant in salt-affected areas[7,13]. Research has also shown that plant responses to sulfate- and chloride-salinity are different. For instance, chloride salts are more detrimental to soybean (Glycine max L.), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis L.) and rice (Oryza sativa L.)[14−16] and cause less stress impact to barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) and corn than Na2SO4[17,18]. While the effects of chloride salinity on legumes are well-documented, sulfate-induced salinity stress responses remain poorly characterized in dry peas, particularly under controlled environment conditions prevalent in the Northern Great Plains. Therefore, the objective of this research was to investigate how dry pea responds to sulfate-salt stress.

-

Two sizes of cone-containers, commonly used in research on wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and rice (Oryza sativa L.), were included in this experiment. The volume of the big container was 556 mL, with dimensions of 6.4 cm in diameter and 25.4 cm in length. The small container had a volume of 410 mL, with a 3.8 cm in diameter and 20.3 cm in length. Each big and small container was filled with 850 and 220 g of coarse sand, respectively. The electrical conductivity (EC) and pH of the sand were 2.33 and 6.45, respectively. Two seeds of a commercially available pea cultivar 'Agassiz' were sown in each container. Containers were placed in the tubs filled with half-strength Hoagland solution[19] (2.5 cm above the bottom of the cone-containers) overnight, then transferred and maintained in tubs filled with tap water to the depth as described above for seed germination.

After germination (7−10 d after seeding), seedlings were thinned to one plant per container. Subsequently, pea seedlings were subjected to saline treatments at 0 (control, tap water), 5, 10, 15, or 20 dS·m−1. Salinity was induced using a mixture of Na2SO4 and MgSO4·7H2O (Table 1). To prevent salinity shock, plants were hand-watered with salt solutions that were gradually increased at a rate of 1.25 dS·m−1 per time (50 mL per pot), 2 times per day. Upon reaching the final concentrations, plants/containers were kept in the tubs filled with salt solutions (2.5 cm above the bottom of the cone-containers) for four weeks. The pH of the salt solutions in the tubs was adjusted to approximately 6.0 to facilitate nutrient uptake. Salt solutions were added to the tubs every day to maintain the same water level, and the entire solution in the tubs was refreshed once weekly. All plants were manually fertilized with full-strength Hoagland solution on the first day of salt treatment and then once weekly during the course of saline treatment. The EC and pH of the salt solutions were measured before and after the solution refreshment to monitor the saline conditions and adjust when needed.

Table 1. Salt mixtures to achieve the targeted salt concentrations from irrigation.

Target salt

concentration (EC, dS·m−1)Na2SO4

(g·L−1)MgSO4·7H2O Na2SO4

(g·L−1)0 0.000 0.000 5 2.370 2.056 10 5.473 4.748 15 8.575 7.440 20 11.678 10.132 The research was carried out in a greenhouse. The experimental design was a split-plot design, with the main plot being the salt tub (arranged in a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with four replicates), and the subplot being the container size. Plants were sampled once weekly for four weeks. Phenotypic data, including root length (RL), shoot fresh and dry weight (SFW, SDW), root dry weight (RDW), absolute water content (AWC = SFW – SDW), specific root length (SRL = RL/RDW), and plant visual damage (VD, rated visually with a 1–5 score described in Table 2), were collected once weekly for four weeks. Shoot dry weight and RDW were recorded after oven-drying at 65 °C for 48 h. The EC and pH were measured from the saturated sand media following the method of the U.S. Salinity Laboratory Staff[20], using the EC/pH meter.

Table 2. Description of plant visual damage using a 1–5 scale score.

Score Description of plant visual damage 1 Healthy, green 2 No more than 25% of leaves are chlorotic/wilted, but no necrosis 3 Chlorosis, wilting, or necrosis on 50% of leaves 4 About 75% of the plants have chlorotic, wilted, or necrotic stem necrosis beginning 5 Plant is dead Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using PROC MIXED (SAS, V9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Least squares means (LSMEANS) were separated using the pdiff option at the 0.05 probability level. Correlations among the phenotypic traits were determined using PROC CORR (SAS, V 9.4, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

-

The medium electrical conductivity (ECe) was significantly affected by salt concentration and duration of saline exposure (Table 3). The ECe in the growing medium increased from 2.37 dS·m−1 in the non-salt treatment to 12.53 dS·m−1 in the medium treated with the 20 dS·m−1 salt solution when data were pooled across container size and duration of exposure. The medium ECe was steady from week one to week three, with an average of 6.51 dS·m−1. At week four, the ECe increased to 9.35 dS·m−1. In contrast, the medium pH was only affected by the duration of saline exposure. The highest pH was observed at week four (7.45), 9.8% higher than that at week one and week three, with an average of 6.79. There were no significant differences in ECe and pH between the two container sizes.

Table 3. The electrical conductivity (ECe) and pH of the growing medium as affected by salt concentration (SC), duration of exposure (DOE), container size (CS), and their interactions.

Treatment ECe (dS·m−1) pH Salt concentration (SC, dS·m−1) 0 2.37 ± 3.05e 6.98 ± 0.62a 5 4.59 ± 3.00d 7.01 ± 0.62a 10 7.04 ± 3.05c 7.06 ± 0.62a 15 9.58 ± 3.05b 7.03 ± 0.62a 20 12.53 ± 3.00a 7.14 ± 0.62a p values (Partial eta-squared, ηp2) < 0.0001 (0.82) 0.8745 (0.06) Duration of exposure (DOE, week) 1 6.44 ± 3.16b 6.73 ± 0.63c 2 6.24 ± 3.16b 7.16 ± 0.63b 3 6.86 ± 3.23b 6.84 ± 0.63c 4 9.35 ± 3.16a 7.45 ± 0.63a p values (Partial eta-squared, ηp²) < 0.0001 (0.37) < 0.0001 (0.04) Container size (CS) Big* 7.41 ± 3.76a** 7.02 ± 1.34a Small 7.04 ± 3.76a 7.07 ± 1.34a p values (Partial eta-squared, ηp²) 0.3502 (0.01) 0.5935 (0.01) SC × DOE 0.6269 (0.12) 0.0553 (0.15) SC × CS 0.6551 (0.03) 0.7319 (0.06) DOE × CS 0.8304 (0.01) 0.7315 (0.04) SC × DOE × CS 0.9370 (0.07) 0.8335 (0.15) * Big container = 556 mL (6.4 cm-diam. × 25.4 cm long); small container = 410 mL (3.8-cm diam. × 20.3 cm long). ** Values represent mean ± standard deviation. Values followed by a common letter within each column are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05. Effects of salt concentration, duration of exposure, and container size on plant growth

-

Root dry weight (RDW) and root length (RL) were negatively affected by salt concentration when data were pooled across container size and duration of salt exposure. In contrast, the specific root length (SRL) showed no response to salt levels (Table 4). The reduction in RDW and RL was first observed at 10 and 15 dS·m−1, respectively. Further reduction in RDW and RL was observed at 20 dS·m−1. Tissue biomass, area water content (AWC), and visual damage (VD) were similar at 0 and 5 dS·m−1, but became negatively affected when the salinity reached 10 and 15 dS·m−1. The plants under the 20 dS·m−1 treatment performed the worst.

Table 4. Growth of pea seedlings as affected by salt concentration, exposure duration, container size, and their interactions.

Treatment aVD SFW (g) SDW (g) AWC (g) aRDW (g) RL (cm) SRL (cm·g−1) Salt concentration (SC, dS·m−1) 0 1.28 ± 1.02c 3.87 ± 1.41a 0.65 ± 0.34a 3.23 ± 1.13a 0.11 ± 0.06a 11.83 ± 0.85ab 124.25 ± 164.95a 5 1.36 ± 1.02c 3.53 ± 1.41a 0.59 ± 0.34a 2.95 ± 1.13a 0.11 ± 0.06ab 12.58 ± 0.85a 147.55 ± 162.58a 10 1.87 ± 1.02b 2.24 ± 1.36b 0.45 ± 0.34b 1.80 ± 1.07b 0.08 ± 0.06bc 10.84 ± 0.85ab 195.38 ± 147.53a 15 2.14 ± 0.96b 1.79 ± 1.36b 0.36 ± 0.34bc 1.44 ± 1.07b 0.07 ± 0.06cd 10.31 ± 0.85b 209.53 ± 139.22a 20 2.76 ± 1.02a 1.06 ± 1.36c 0.25 ± 0.34c 0.82 ± 1.07c 0.05 ± 0.06d 8.37 ± 0.85c 239.96 ± 143.23a p values (Partial eta-squared, ηp²) 0.0002 (0.15) < 0.0001 (0.62) < 0.0001 (0.49) < 0.0001 (0.62) 0.0012 (0.35) 0.0054 (0.24) 0.0631 (0.15) Duration of exposure (DOE, week) 1 1.04 ± 0.95c 1.69 ± 1.33c 0.25 ± 0.32c 1.45 ± 1.08c 0.09 ± 0.06b 10.75 ± 4.05a 146.02 ± 136.42b 2 1.35 ± 1.01c 2.36 ± 1.39b 0.36 ± 0.38b 2.01 ± 1.14b 0.11 ± 0.06a 11.52 ± 4.24a 146.31 ± 136.42b 3 1.95 ± 1.01b 3.02 ± 1.39a 0.58 ± 0.38a 2.45 ± 1.14a 0.08 ± 0.06b 10.86 ± 4.36a 178.11 ± 134.46b 4 3.19 ± 1.01a 2.93 ± 1.39a 0.65 ± 0.38a 2.28 ± 1.08a 0.06 ± 0.06c 10.02 ± 4.24a 262.89 ± 131.55a p values (Partial eta-squared, ηp²) < 0.0001 (0.66) < 0.0001 (0.33) < 0.0001 (0.59) < 0.0001 (0.25) 0.0005 (0.22) 0.3304 (0.04) 0.0002 (0.24) Container size (CS) bBig 1.69 ± 1.07b 3.01 ± 1.61a 0.55 ± 0.45a 2.47 ± 1.16a 0.10 ± 0.09ac 11.61 ± 4.47a 156.35 ± 130.94b Small 2.07 ± 1.25a 1.99 ± 1.70b 0.37 ± 0.45b 1.63 ± 1.34b 0.07 ± 0.09b 9.97 ± 5.10b 210.31 ± 152.59a p values (Partial eta-squared, ηp²) 0.0064 (0.09) < 0.0001 (0.32) < 0.0001 (0.28) < 0.0001 (0.30) < 0.0001 (0.19) 0.0062 (0.09) 0.0111 (0.06) SC × DOE 0.0002 (0.36) < 0.0001 (0.41) 0.0002 (0.36) < 0.0001 (0.40) 0.7244 (0.12) 0.3009 (0.15) 0.2585 (0.18) SC × CS 0.9942 (0.01) 0.087 (0.08) 0.0519 (0.08) 0.1194 (0.07) 0.2794 (0.06) 0.2906 (0.05) 0.6338 (0.07) DOE × CS 0.0549 (0.08) 0.0331 (0.11) 0.1509 (0.06) 0.0315 (0.11) 0.4091 (0.05) 0.1709 (0.04) 0.1990 (0.02) SC × DOE × CS 0.8907 (0.07) 0.4813 (0.14) 0.4723 (0.14) 0.4980 (0.13) 0.1845 (0.21) 0.4981 (0.12) 0.3333 (0.17) aVD = visual damage rating (1–5 scale, 1 = healthy plants and 5 = dead plants), SFW = shoot fresh weight, SDW = shoot dry weight, AWC = absolute water content, RDW = root dry weight, RL = root length, SRL = specific root length. bBig container = 556 mL (6.4 cm-diam. × 25.4 cm long); small container = 410 mL (3.8-cm diam. × 20.3 cm long). cValues represent mean ± standard deviation. Values followed by the same letter within each column are not significantly different at p ≤ 0.05. The RL showed no change from week one to week four after the salt exposure, with an average of 10.8 cm when data were pooled across salt concentration and container size (Table 4). The SRL was steady from week one to week three after salt exposure with an average of 156.8 cm·g−1, which was 41.4% less than that in week four. The highest and lowest RDW were detected in week two and week four, respectively, after salt treatment. The result also showed that under the low saline conditions (≤ 10 dS·m−1), SDW and AWC was greater in week three and week four than that in week one and week two; however, under the high saline condition (15 and 20 dS·m−1), tissue biomass and AWC showed a limited change from week two to week four. The VD was 2.4 in the plants at 20 dS·m−1 at week two, which was significantly higher than those in other treatments. By week four, plants in the saline solution at 15 and 20 dS·m−1 were almost all dead (averaged VD = 4.3).

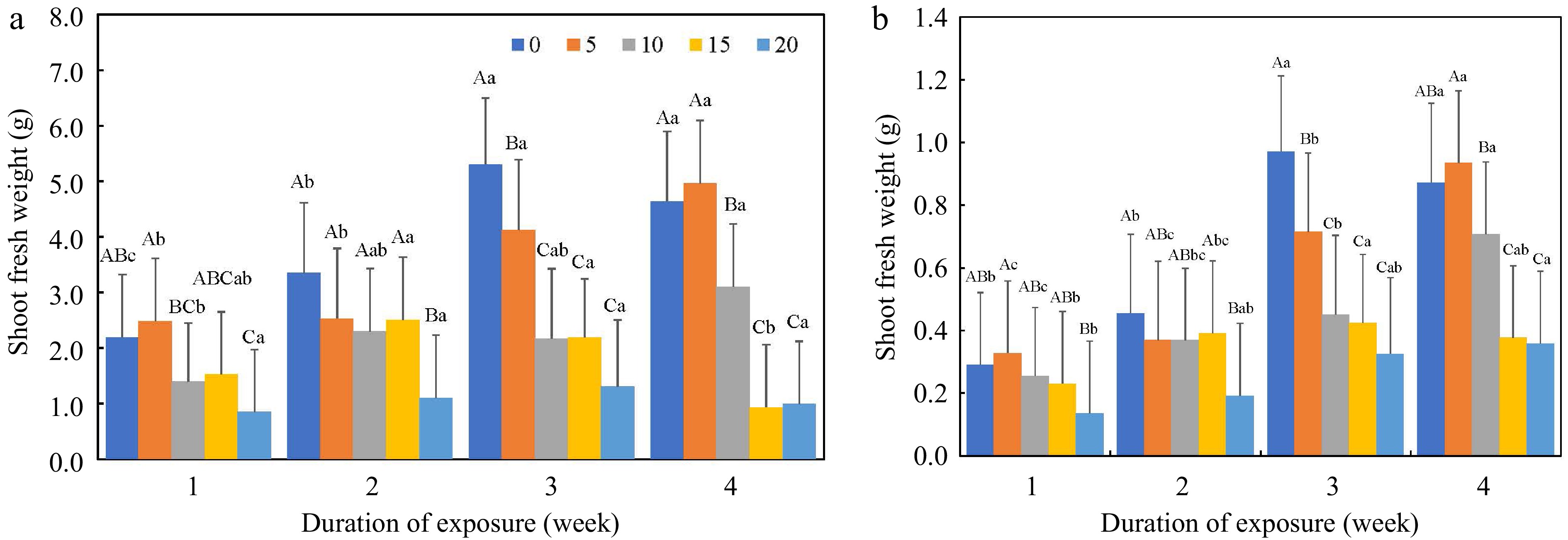

The two-way interaction, salt concentration × duration of exposure, was detected in SDW, AWC, and VD (Figs 1 & 2). Plants showed limited damage under 5 dS·m−1, followed by 10 dS·m−1, while 15 and 20 dS·m−1 severely inhibited growth at week three and/or week four. The differences among salt concentrations at weeks one and two were less pronounced compared to later weeks, except at 20 dS·m−1, due to short term of stress exposure.

Figure 1.

(a) Shoot fresh weight, and (b) shoot dry weight in grams (g) as affected by salt concentration (0–20 dS·m−1) and duration of saline exposure (week). Uppercase letters indicate differences among salt concentrations in the same week at p ≤ 0.05. Lowercase letters indicate differences among weeks at the same salt concentration at p ≤ 0.05.

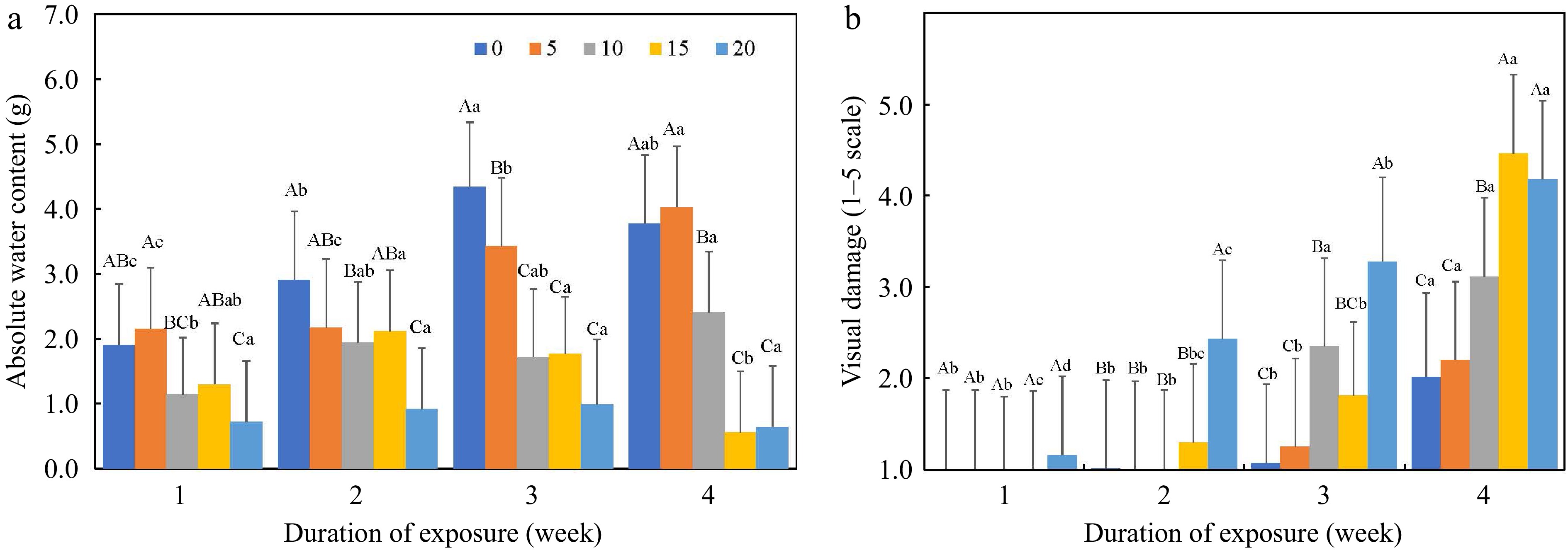

Figure 2.

(a) Absolute water content in grams (g), and (b) visual damage (1–5 scale, 1 = healthy plants and 5 = dead plants) as affected by salt concentration (0–20 dS·m−1) and duration of saline exposure (week). Uppercase letters indicate differences among salt concentrations within the same week at p ≤ 0.05. Lowercase letters indicate differences among weeks at the same salt concentration at p ≤ 0.05.

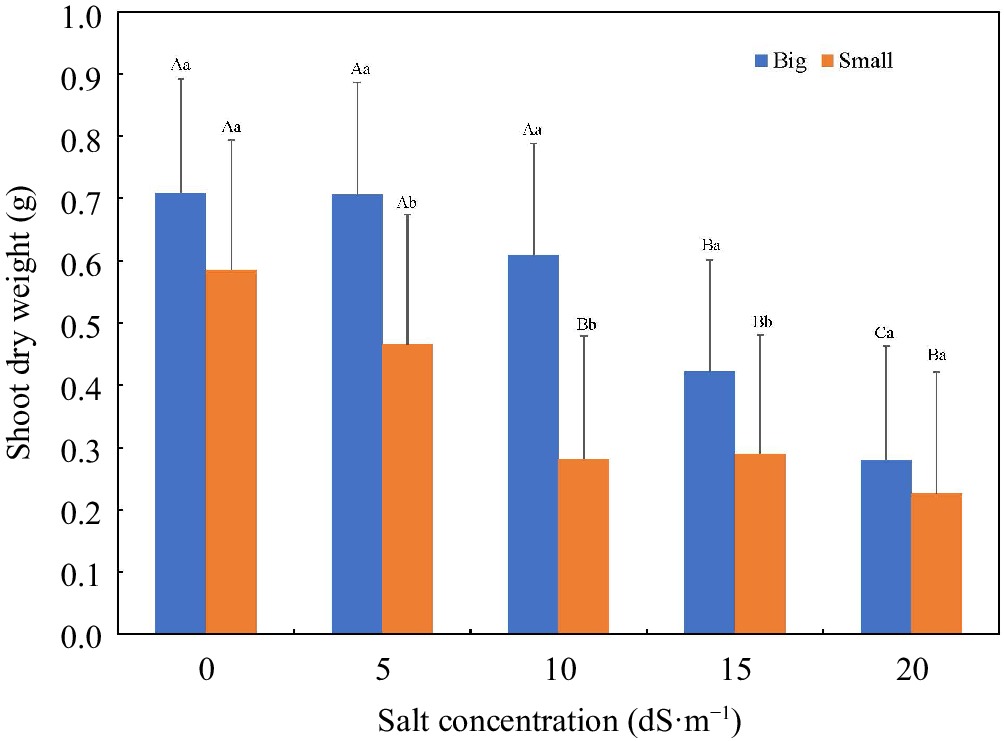

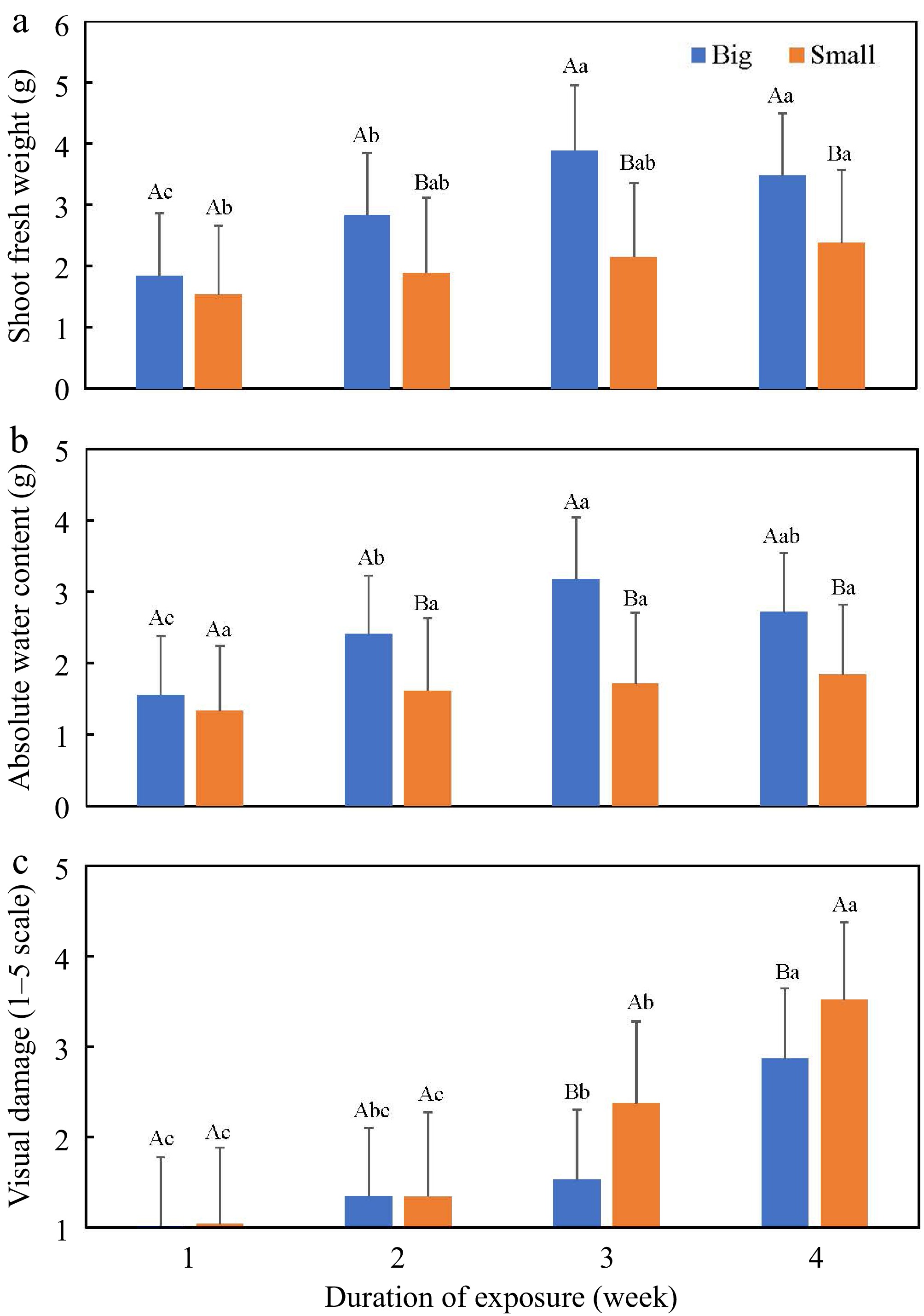

Container size significantly affected the plant growth. Plants grown in small containers exhibited lower values for each individual growth index than those in big containers, when data were pooled across salt concentration and duration of exposure, except SRL and VD (Table 4). The highest and lowest growth reduction was observed in AWC (34.0%) and RL (14.9%), respectively. A higher SRL (210.31 cm·g−1) in small containers was caused by a higher reduction of RDW (30.0%) than RL (14.1%) compared to those in big containers (Table 4). Plants grown in small containers showed more leaf yellowing/chlorosis in the lower portion of a plant, resulting in a higher VD than those in big containers. Similar trends were observed when the salt concentration × container size and the duration of exposure × container size interactions were detected, except at the extreme salt levels (0 and 20 dS·m−1) and during the initial stage of salt exposure (week one) (Figs 3 & 4).

Figure 3.

Shoot dry weight (g) as affected by salt concentration (0–20 dS·m−1) and container size (big and small). Uppercase letters indicate differences among salt concentrations in the same container size at p ≤ 0.05. Lowercase letters indicate differences between container sizes at the same salt concentration at p ≤ 0.05. Big container = 556 mL (6.4 cm diam. × 25.4 cm long); small container = 410 mL (3.8 cm diam. × 20.3 cm long).

Figure 4.

(a) Shoot fresh weight (g), (b) absolute water content (g), and (c) visual damage (1–5 scale, 1 = healthy plants and 5 = dead plants) as affected by container size (big and small) and duration of saline exposure (week). Uppercase letters indicate differences between container sizes in the same week at p ≤ 0.05. Lowercase letters indicate differences among weeks in the same container size at p ≤ 0.05. Big container = 556 mL (6.4 cm diam. × 25.4 cm long); small container = 410 mL (3.8 cm diam. × 20.3 cm long).

Correlations

-

All growth indices were associated with the medium salinity (p ≤ 0.05), in which SRL and VD were positively correlated with medium salinity, while other growth indices were negatively associated with the medium salinity (Table 5). Four growth indices showed correlations with medium pH (p ≤ 0.05), with correlation coefficients ranging from −0.20 in RDW to 0.27 in VD. The correlations among root characteristics (RL, RDW, and SRL) were lower than those among shoot characteristics (absolute water content (AWC), total aboveground weight (TAGDW), and total aboveground fresh weight (TAGFW)).

Table 5. Pearson correlation coefficient analyses (p-value) between electrical conductivity (ECe) and pH of growing medium and growth indices in pea seedlings.

ECe pH RDW RL SRL AWC SDW SFW VD ECe pH 0.22 (0.0173) RDW −0.45 (< 0.0001) −0.20 (0.0386) RL −0.42 (< 0.0001) −0.08 (0.4096) 0.64 (<0.0001) SRL 0.34 (0.0004) 0.24 (0.0156) −0.71 (0.0002) −0.33 (0.0002) AWC −0.49 (< 0.0001) 0.03 (0.7346) 0.61 (< 0.0001) 0.56 (< 0.0001) −0.44 (< 0.0001) SDW −0.26 (0.0050) 0.16 (0.0921) 0.48 (< 0.0001) 0.46 (< 0.0001) −0.29 (< 0.0001) 0.86 (< 0.0001) SFW −0.46 (< 0.001) 0.06 (0.5491) 0.60 (< 0.0001) 0.55 (< 0.0001) −0.42 (0.0011) 0.99 (< 0.0001) 0.90 (< 0.0001) VD 0.49 (< 0.0001) 0.27 (0.0043) −0.40 (< 0.0001) −0.30 (0.0005) 0.44 (< 0.0001) −0.37 (< 0.0001) −0.02 (0.8539) −0.31 (0.0003) ECe = electrical conductivity from saturated growing medium, RDW = root dry weight, RL = root length, SRL = specific root length, AWC = absolute water content, SFW = shoot fresh weight, SDW = shoot dry weight, VD = visual damage rating (1–5 scale, 1 = healthy plants and 5 = dead plants). -

Various research studies have shown that soil or medium salinity increases with the increasing salt concentration in irrigation water and the increasing duration of salt treatment[21−24], which is similar to the findings of the present research. Kim et al.[22] reported no significant pH difference in the soil-grown lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) and Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. subsp. pekinensis) that were irrigated with NaCl solution (0.3–1.9 dS·m−1) for 1–1.5 months. This study found that the medium pH was not affected by salt concentration and container size. Mahler et al.[25] reported that the soil pH increased from 6.73 to 7.45 over a four-week saline exposure, but it was still in the optimal range of 5.9 to 7.5 for pea growth. The previous and current research results suggest that soil salinity is more sensitive to saline irrigation than soil pH, which is in agreement with the result reported by Rahman et al.[26] that water soluble Na was a better indicator of soil salinity (r = 0.99) than soil pH (r = 0.27).

This study determined that seven of eight growth indices correlated with the medium salinity, while four growth indices correlated with the medium pH (Table 5). Furthermore, the correlation coefficients between the growth indices and ECe were higher than those between the growth indices and medium pH. It suggests that plant growth is more influenced by soil salinity (concentration and duration) than by soil pH. Ljubojević et al.[27] reported that VD and the growth indices of plant height, fresh weight, and root system volume are reliable criteria in evaluating the salinity tolerance of three Salvia species. In the present study, the correlation coefficients between VD, RDW, RL, AWC, and SFW and soil salinity were above |0.40| (Table 5), close to the threshold level [0.50 ≤ |r| ≤ 1.00)] for a strong correlation[28]. Severe damage induced by high salt concentration at 15 and 20 dS·m−1, especially at weeks three and four, may contribute to the relatively low correlation coefficients observed in this study. For example, the AWC of the plants under the high salt treatments (i.e. 15 and 20 dS·m−1) at week four was 0.60 g, 84.1% lower than the control treatment (0 dS·m−1) (Fig. 2a).

Absolute water content is an indicator of leaf size[29]. This study showed that AWC was significantly correlated with soil salinity and all growth indices (Table 5). Furthermore, AWC was the earliest response with the highest reduction to saline conditions (Table 4; Fig. 2a). Our results suggest that a 34% reduction in AWC at 10 dS·m−1 (Fig. 2a) may be used as a critical threshold value for irrigation management in saline-prone regions. Because salinity induces osmotic stress (or physiological drought) at the early stage of salinity stress, the initial plant responses of plants to salinity and drought are similar[30]. Cell enlargement (e.g., leaf size) is more sensitive to internal water content than to other growth indices, such as shoot and root dry weight, chlorophyll content, and photosynthetic rate[31,32]. This study also indicated that the SFW was the 2nd highest reduction (72.6%) in the growth indices as the salinity increased from 0 to 20 dS·m−1 (Table 4). This study found that VD and AWC showed a similar level of correlation to soil salinity (r = 0.49, p ≤ 0.05), although VD was not as closely related to other growth indices as AWC. Munns and Tester[30] reported that the VD changes, such as leaf chlorosis and defoliation, were more closely related to nutrient imbalance and toxicity, especially the Na/K ratio, which often occurs at the late stage of salinity stress. Therefore, AWC, TAGFW, and VD show the potential to be used as key criteria to evaluate plant responses to salinity.

Specific root length reflects the energy distribution in roots between water and nutrient uptake (i.e., RL) and carbohydrate storage (i.e., RDW)[33]. Ostonen et al.[34] suggested that SRL is a good indicator of root responses to environmental changes. In this study, the SRL was positively related to soil salinity (r = 0.34, p ≤ 0.05), consistent with the findings of Abbas et al.[35] and Rue & Zhang[36]. Chen et al.[37] and this study showed that RL was less affected by salinity than RDW, resulting in increased SRL under saline conditions. Furthermore, this study showed a stronger correlation between SRL and RDW (r = −0.71, p ≤ 0.05) than SRL and RL (r = −0.33, p ≤ 0.05) (Table 5). However, the correlation between SRL and medium ECe was not as strong as that between RDW, RL, and ECe (Table 5), suggesting that all three root characteristics must be taken into consideration to have a good understanding of the influence of salinity on root morphology[32,33]. Only RDW is affected by the duration of saline exposure (Table 4). Reduced RDW observed in weeks three and four is mostly due to the growth reduction at high salt concentrations (15 and 20 dS·m−1), especially in the small containers (data not shown). However, the relative higher reduction at high salinity is not sufficient to cause a concentration x duration interaction in RDW nor statistical differences in SRL.

Container size influences plant growth and development. Plant height, leaf size and number, and tissue biomass generally decrease with decreasing container size[38,39]. How small containers restrict plant growth and development is not well understood. Small pots have a lower holding capacity of different resources, such as water and nutrients, than big ones[38,39]. Plants grown in small pots have lower root length (i.e., vertical growth) and a larger fraction of roots close to the edge of the pot (i.e., horizontal growth), where environmental conditions may fluctuate frequently and dramatically[39]. Ronchi et al.[40] reported reduced photosynthetic rate in the coffee (Coffea arabica L.) plants as the container size reduced from 24-L to 3-L. It was likely due to lower tissue N content and its related characteristics (e.g., Rubisco activity and chlorophyll content) detected in the 3-L pots. No differences were observed in other nutrients (P, S, K, Ca, Mg, Cu, Zn, Fe, and Mn), chlorophyll fluorescence, and water status in pot sizes. Reduced photosynthesis leads to low shoot and root biomass, although shoot-to-root biomass ratios are sometimes not affected[39]. However, use of small pots may be an advantage as it implies an increased number of plants/replications and reduced cost in labor, time, space, and management (e.g., irrigation and fertilizers)[39]. It is particularly true when conducting research evaluating phenotypic traits in a large population, especially if space is a limiting factor. Therefore, it is important to identify an appropriate pot size that is small to maintain research and production efficiency, but without putting constraints on plant growth, interfering with research findings, and productivity. The effects of two sizes of cone-containers, 556 mL (big) and 410 mL (small), on pea growth under saline conditions were evaluated in the present study. Pea plants grown in small cone-containers had lower levels of shoot and root biomass, RL, and AWC, but higher levels of SRL and VD (Table 4). Similarly, Zhou et al.[41] observed an increase in plant height, stem diameter, and root length of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants grown in the 200 L container than in the 8−48 L containers under both saline and non-saline conditions. Broccoli (Rassica oleracea L. var. italica) grown in small containers (2 L) had lower curd fresh and dry weight than those in big containers (4 L), and the differences were more pronounced under salinity stress[42]. The physiological mechanisms of the effects of container size on plant stress tolerance need to be further studied. Two two-way interactions, salt concentration × container size and the duration of exposure × container size interactions, were detected in this research (Table 3). The differences between the two containers were more pronounced at 5–15 dS·m−1 and weeks three and four than other concentrations and weeks (Figs 3 & 4). The plants in big cone-containers were severely stressed by high salinity (15 and 20 dS·m−1) and long exposure duration (four weeks), therefore, the differences between container size were reduced at week four compared to week three. It is also possible that the pots were not large enough for peas to grow by week four. The plants grown in the small cone-containers (410 mL) at 0 dS·m−1 showed more rapid senescence of old leaves (VD = 2.7) by week four compared to those in the big cone-containers (556 mL) (VD = 1.3), suggested that the big-containers were able to support four-week normal growth of pea seedlings with no adverse effects from container size. The physiological mechanisms of container size, in addition to sulfate-salinity and duration of exposure, on plant stress tolerance need to be studied.

-

Dry pea is a nutritive leguminous crop mainly produced in the Northern Great Plains, where sulfate-salinity is a major obstacle to agricultural production. Therefore, it is critical to understand the effect of sulfate salinity on dry pea growth and development. Sulfate salinity negatively affects dry pea growth. Stress severity increases with increasing salt concentration and duration of exposure. Among the phenotypic data, AWC, SFW, VD, RL, RDW, and SRL are reliable indicators of plant tolerance to sulfate-salinity. In addition, container size is also a factor affecting plant response to salinity stress, in which big containers are likely to reduce stress damage.

Special thanks to ND Specialty Crop Block Grant Project (Grant No. 18-265) and USDA Hatch project (Grant No. ND01509) for funding this research.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhang Q; conducting experiment and data collection: Bredu ES; data analysis and interpretation: Zhang Q, Bredu ES; draft manuscript preparation: Zhang Q, Bredu ES. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Bredu ES, Zhang Q. 2025. Differential growth responses of dry peas (Pisum sativum L.) to gradient sulfate salinity stress in a controlled greenhouse setting. Technology in Agronomy 5: e012 doi: 10.48130/tia-0025-0007

Differential growth responses of dry peas (Pisum sativum L.) to gradient sulfate salinity stress in a controlled greenhouse setting

- Received: 12 February 2025

- Revised: 24 April 2025

- Accepted: 07 May 2025

- Published online: 05 August 2025

Abstract: Dry pea (Pisum sativum L.), an important cool-season legume species, is prone to salinity stress. Previous research mostly focused on chloride salt-induced salinity (chloride salinity). In the Northern Great Plains, the major production region of dry pea in the U.S., soil salinity is predominantly induced by sulfate salts. The objective of this research was to determine how dry pea responds to sulfate-induced salinity. The seed of cultivar Agassiz was sown in the two sizes of cone-containers (big cone, 556 mL and small cone, 410 mL) and exposed to sulfate-salinity (0−20 dS·m−1) through irrigation for four weeks at the seedling stage. Plants were sampled once weekly, and plant height, root and shoot growth, and visual damage were quantified. Plants treated with 5 dS·m−1 showed no damage, which was similar to the non-stressed plants (0 dS·m−1); however, plant growth was reduced by 50%−60% in tissue biomass in the 10 dS·m−1 salinity treatment, while plant was severely damaged or dead in the 15 and 20 dS·m−1 by week four. Among the evaluated traits, absolute water content, shoot fresh weight, and visual damage were mostly affected by the salinity stress. Plants grown in the big containers performed better than those in the small ones at 5–15 dS·m−1 and after three or four weeks of saline exposure. This research provided useful information to dry pea growers and breeders on salinity management, particularly sulfate-salinity stress.

-

Key words:

- Pisum sativum /

- Na2SO4 /

- MgSO4