-

With growing consumer emphasis on food safety and nutrition, food quality and safety assurance have emerged as a critical research focus[1]. Key quality indicators including food shelf life, visual quality, and nutritional content[2] are receiving increasing attention. However, the high moisture content of agricultural products makes them particularly susceptible to microbial spoilage and quality deterioration. In several developing countries, particularly those in Southern Africa, approximately 30%−40% of fruits and vegetables are wasted annually due to postharvest decay[3], resulting in significant economic losses. The African Postharvest Losses Information System (APHLIS) estimates that 18% of maize in Ghana is lost due to improper postharvest storage, resulting in an economic loss of USD

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ Drying is a common and important processing method to extend the shelf-life of agricultural products[6], which reduces microbial activity by lowering the water content in the material thereby prolonging the storage time. Sunlight drying, the most traditional method for agricultural products, is low-cost and widely accessible. However, traditional open-air drying techniques fail to adequately prevent the deterioration and contamination of dried products, resulting in substantial income losses for farmers, reaching up to 34%[7]. Beyond economic impacts, suboptimal drying practices also lead to aflatoxin contamination, posing significant risks to food safety and public health[8]. Drying, as an important technology for processing in the food processing field, not only has to consider energy loss and economy but also needs to ensure product flavor, appearance, texture, color, rehydration rate, and nutrient retention to produce high-quality products[9,10]. Drying is an energy-intensive unit, with its energy consumption accounting for 20%−25% of food processing, and drying is also widely used in other industries. For every 1% reduction in energy consumption, profits may increase by 10%[11−13].

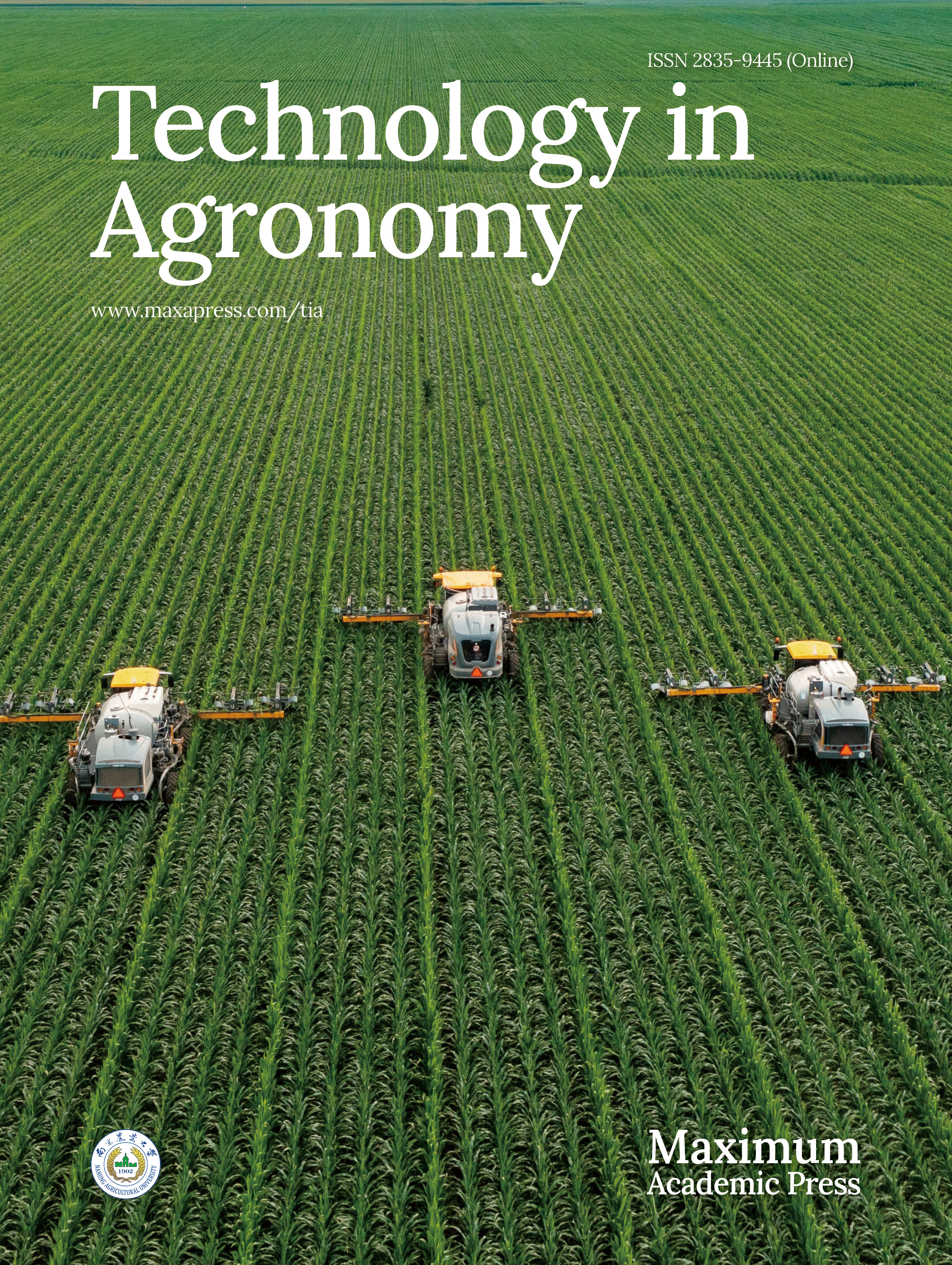

As shown in Fig. 1a, hot air drying not only requires prolonged processing duration, but also induces undesirable changes such as color alteration, surface hardening, and shape deformation, thereby compromising product quality[14]. The study by Santos & Silva[15] demonstrated that ascorbic acid (vitamin C) undergoes sequential degradation during drying: it first decomposes into dehydroascorbic acid, which is subsequently oxidized into 2,3-diketogulonic acid, resulting in significant nutrient loss. Drying kinetic analysis (Fig. 1b) reveals rapid and relatively constant dehydration rates during the constant-rate period. However, the falling-rate period exhibits progressively slower drying kinetics accompanied by quality deterioration, with a particularly accelerated rate decline in the second falling-rate phase. As shown in Fig. 1c, the study by Jiang et al.[16] demonstrated significant differences in the visual quality (e.g., color uniformity, surface integrity) and microstructural characteristics (e.g., pore size distribution, cell wall deformation) of sweet potatoes under different drying processes and strategies, highlighting the critical impact of drying techniques on final product quality.

Figure 1.

Drying process analysis. (a) Hot air drying defects, high energy consumption and poor quality. (b) Drying quality under different drying strategies. (c) Drying rate curve, rate change at each stage[16]. (d) Water mass transfer process.

Regarding moisture migration mechanisms (Fig. 1d), in the drying preheating and constant speed drying stage, the external diffusion rate V1 is less than the internal diffusion rate V2[17], the drying rate of this process remains basically unchanged and is mainly controlled by the external environment. When V1 > V2, it enters the deceleration drying stage (including the first drying stage deceleration and the second drying stage deceleration), at this time, a layer of dry area is formed on the surface of the material, which will not only lead to the hardening of the surface of the material but also increase the resistance of the internal moisture migration of the material to the outside[18]. The drying rate of this stage is mainly controlled by the internal diffusion rate of the material, but it also involves energy consumption and quality issues. Research by Savitha et al.[19] indicates that during the initial stage of moisture loss, the tissues and cells undergo contraction, and as dehydration progresses, the pores eventually collapse, leading to the onset of the falling rate period.

Significant variations in moisture migration mechanisms and material-water binding energy exist across different drying stages[18]. Implementing stage-specific drying strategies therefore represents the most scientifically rigorous approach to optimize drying processes[20]. To detect the optimal moisture excess threshold, it will be necessary to monitor the entire drying process. The development of rapid, non-destructive online methods for monitoring and controlling the drying quality of agricultural products has advanced significantly. Several cutting-edge nondestructive monitoring technologies, such as dielectric properties[21], near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)[22], hyperspectral imaging (HSI)[23], and computer vision systems (CVS), have been applied to diverse monitoring scenarios. Furthermore, multi-sensor data fusion approaches are increasingly being adopted for joint evaluation[24]. This paper focuses on the application of new rapid nondestructive testing techniques such as the dielectric constant method, near-infrared spectroscopy, HIS, CVS, etc., for drying process monitoring. A comparative analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of various detection methods are presented, along with an examination of their respective applicable scenarios. The discussion is further enriched by an exploration of the challenges associated with integrating innovative detection technologies with the drying process of agricultural products.

-

Dielectric properties quantitatively characterize a material's capacity to absorb, transmit, and reflect electromagnetic energy[25]. In agricultural products, these properties establish critical correlations between electromagnetic field interactions and material composition[18]. Multiple factors influence food dielectric behavior, principally electromagnetic frequency, temperature, moisture content, bulk density, and chemical constituents - particularly ionic components (e.g., salts) and non-polar substances (e.g., fats)[26].

The dynamic relationship between dielectric parameters (permittivity ε' and conductivity σ) and moisture content enables real-time monitoring of water migration during drying. As demonstrated in fragrant rice drying[27], tracking dielectric variations (ε', σ) allows precise determination of moisture transition points. The complex permittivity (

$ \varepsilon _{\text{r}}^ * $ $ \varepsilon _r^\prime $ $ {\varepsilon }_{r}^{\prime\prime} $ $ \begin{array}{l}{\varepsilon }_{\text{r}}^{\ast }={\varepsilon }_{r}^{\prime }-j \times {\varepsilon }_{r}^{{\prime\prime}};\\ {j}^{2}=-1\end{array} $ (1) The relative permittivity (

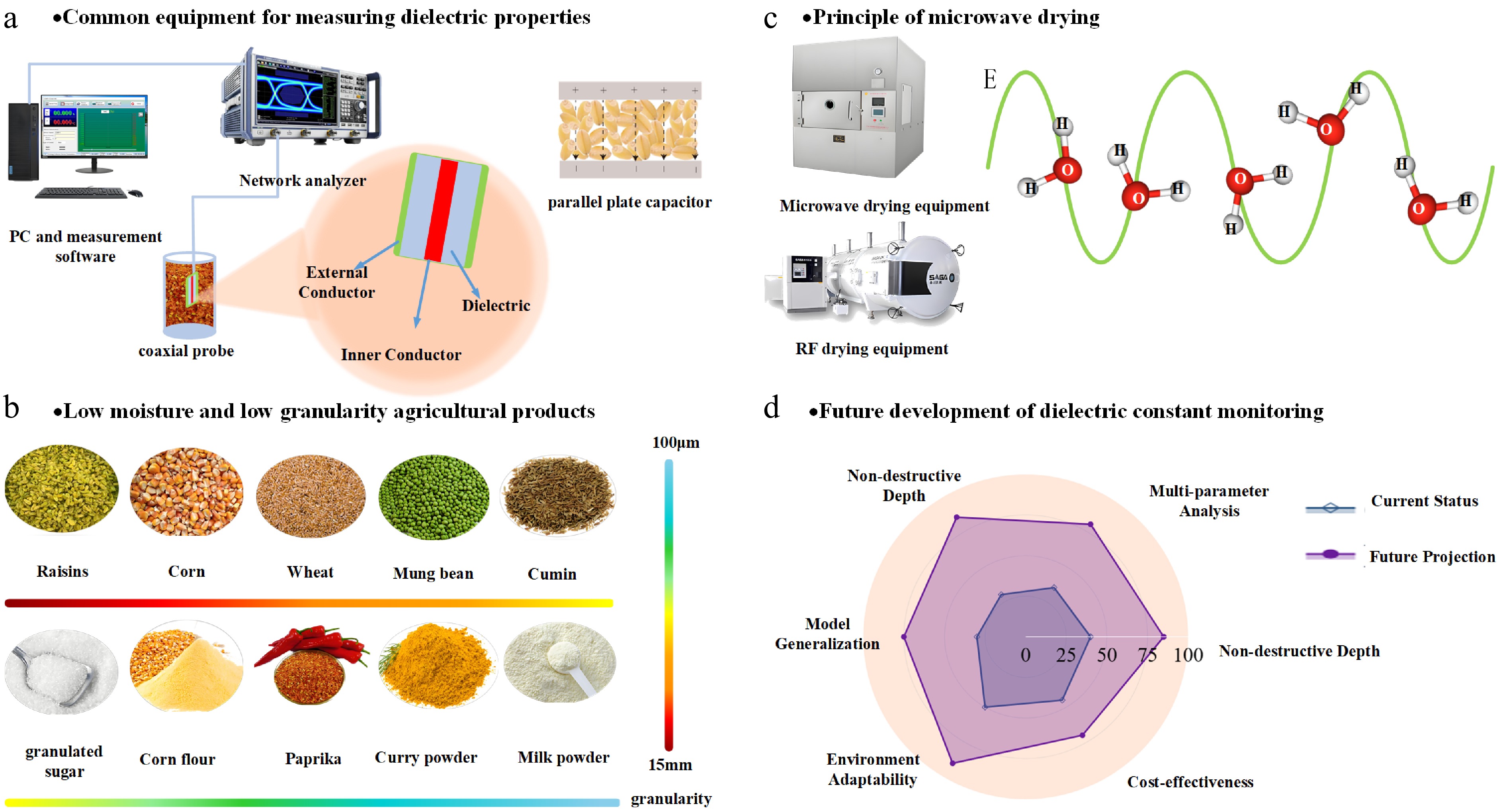

$ \varepsilon _r^\prime $ $ {\varepsilon }_{r}^{\prime\prime} $ Common techniques for measuring dielectric properties of agricultural products and foods, are shown in Fig. 2a, including the coaxial probe method[28], the parallel plate capacitor method[29], and resonance methods. A typical coaxial probe measurement system consists of an appropriate network analyzer, measurement software, and a coaxial probe. This method requires tight contact between the probe tip and tested material, making it particularly suitable for granular agricultural products with fine particle sizes, such as chili powder, milk powder, and wheat flour (Fig. 2b). Liquid and semi-solid materials generally achieve better contact with the probe surface. In their study on radio frequency (RF) drying of in-shell peanuts, Lei et al.[28] employed the coaxial probe method (as shown in Fig. 2a) to measure the dielectric properties of peanut shells and kernels during the drying process. The open-ended coaxial probe requires tight contact with the sample; however, the irregular geometries of peanut shells and kernels posed significant challenges. To address this, the researchers ground and compacted the samples to match the density of intact peanuts, and then measured them within a cylindrical container.

Figure 2.

The dielectric property detection drying process. (a) Common equipment for measuring dielectric properties. (b) Low moisture and low granularity agricultural products. (c) Principles of microwave drying.

The parallel plate capacitor method involves sandwiching the test material as a dielectric medium between parallel plates, with dielectric constant calculated through capacitance measurements. To optimize contact between probes/plates and material surfaces, researchers often develop customized test cells tailored to specific materials. For instance, when measuring the dielectric properties of corn leaves, Sun et al.[30] designed a clamping-enhanced measurement device that addressed the pressure control limitations of conventional parallel plate capacitors, enabling secure leaf fixation. As dielectric properties are influenced by multiple factors, measurements are typically conducted under controlled conditions. In studies of wheat dielectric characteristics, Lin & Wang[31] created an adjustable-height sample holder to maintain consistent density and pressure during testing.

A material's dielectric properties determine its polarization degree in microwave and radiofrequency (RF) electric fields. Consequently, accurate measurement of these characteristics becomes crucial for microwave drying and RF drying applications[31]. As illustrated in Fig. 2c, under electric field exposure, polar molecules rotate and oscillate rapidly in alignment with the field direction. This molecular friction converts electromagnetic energy into thermal energy, enabling material heating and drying. Materials with higher relative permitivity exhibit greater polarization capacity, demonstrating enhanced microwave/RF energy absorption and more efficient thermal conversion. Investigating dielectric properties facilitates understanding of electromagnetic field-material interactions, which informs the development and optimization of microwave applicators[32]. By adjusting operating parameters such as output power and frequency in microwave/RF systems, precise control over energy absorption and drying kinetics can be achieved, accommodating diverse materials and different drying phases.

The calculation of the depth of penetration during microwave drying is predicated on the prediction of the dielectric properties. This provides a novel approach to the drying of agricultural products. For instance, in the drying process of rice, the monitoring of the dielectric constant was used to establish a model to appropriately increase the drying temperature and increase the drying rate[33]. By analyzing the dielectric properties and other physicochemical properties, an optimized drying process was established for the drying of tiger nuts[34] and shelled peanuts[28].

However, the current dielectric characterization methods employed for monitoring the drying process of agricultural products encounter certain challenges. The interference of environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, on the measurement of dielectric constant introduces bias in the measurement results. The methods and equipment utilized for measurement are constrained by limitations, including the applicable frequency range and the types of samples that can be measured. Furthermore, during the drying process of agricultural products, the dielectric constant is interrelated with multiple parameters, such as moisture content, temperature, and drying time, which complicates the processing and analysis of the resulting data.

To address these challenges (Fig. 2d), future advancements in technology, equipment innovation, and data processing and analysis are imperative. Technological breakthroughs in measurement technology are anticipated to include developments that adapt to environmental changes and automatically correct for various interference factors. It is foreseeable that the scaled-up application of dielectric property monitoring in agricultural product drying processes will need to overcome three core challenges: environmental robustness, cost control, and system integration. The incorporation of artificial intelligence algorithms into measurement strategies is expected to autonomously adjust to mitigate the impact of environmental factors and sample variations on measurement outcomes, thereby facilitating high-precision and -stability in the measurement of dielectric constant.

-

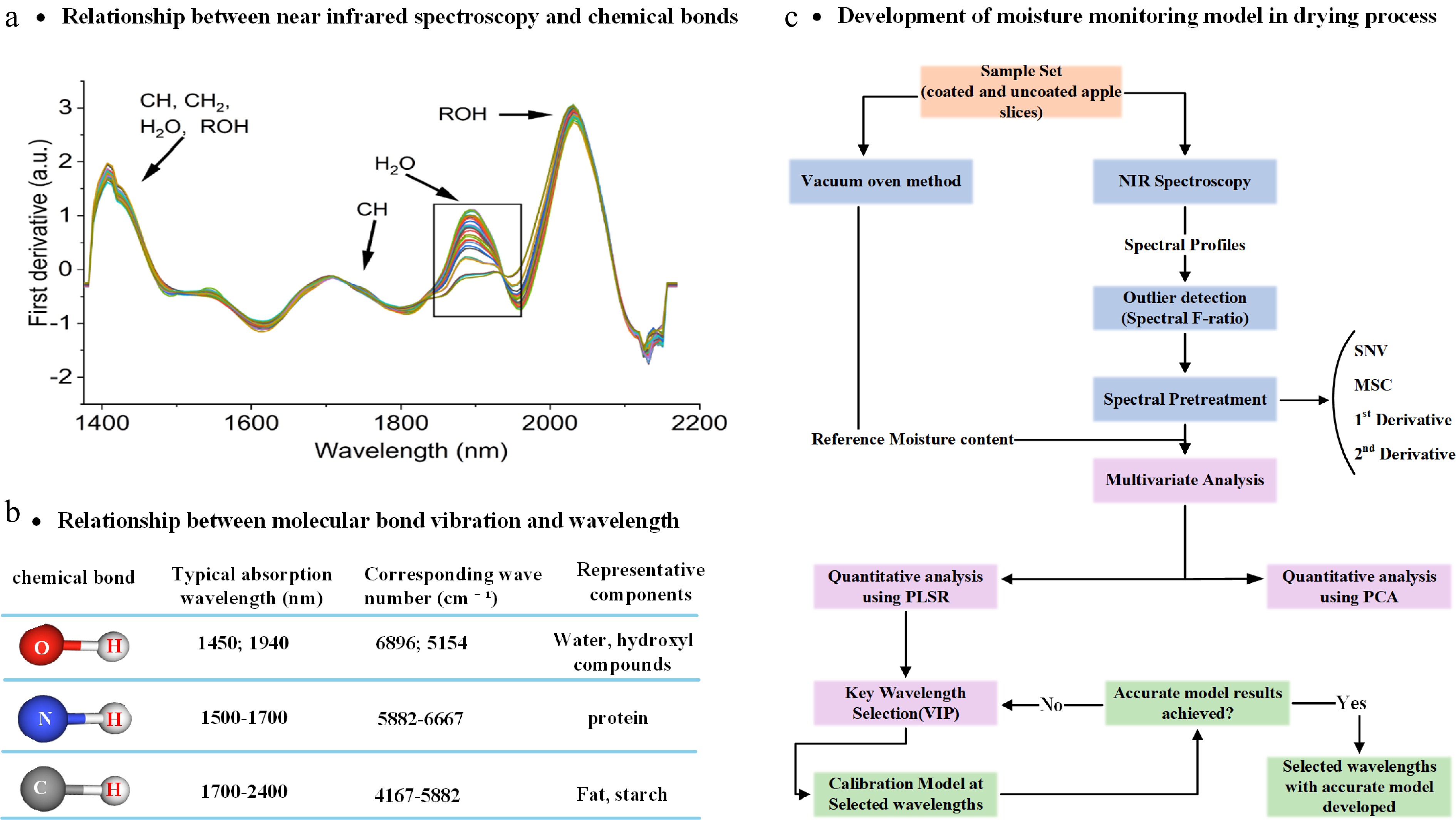

Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy is a technique based on the absorption of electromagnetic radiation in the wavelength range of 780–2,526 nanometers (nm). In recent years, it has gained recognition as a powerful analytical method for monitoring drying processes due to its advantages, such as rapidity and non-destructiveness[35]. At the molecular level, food or agricultural products are maintained by various molecular bonds. The electromagnetic wave's passage through the food sample leads to a change in its energy, resulting from the bending or stretching vibration of chemical bonds, such as O-H, C-H, and N-H. As demonstrated in Fig. 3a and b[36], the NIR spectra of agricultural products contain information regarding the vibrational behavior of molecular bonds, including C-H, O-H, and N-H. Through the interpretation of these spectra, the moisture content[37,38], protein, fat[39], and cellulose content of the agricultural products can be determined.

However, due to the multitude of chemical bonds present in food products, a single spectrum is often unable to accurately determine the characteristics of specific chemical components. To address this challenge, researchers have extensively explored the potential of integrating chemometric analysis with NIR spectroscopy to assess the moisture content and quality of agricultural products. In a notable study, Kapoor et al.[40] utilized near-infrared spectroscopy in conjunction with chemometrics to examine the edible coating of apple slices. Their findings demonstrated that NIR spectroscopy combined with chemometrics could effectively monitor the drying process, and they were able to accurately differentiate between coated and uncoated apple slices by analyzing the difference in absorption bands of sugar and water. The authors further delineated a methodological framework for the development of a calibration model and the selection of critical wavelengths. This framework is illustrated in Fig. 3c and offers a reference point for the application of NIR spectroscopy in the analysis of the drying process. Additionally, the integration of Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy with machine learning algorithms has become a highly active research area. Jiang et al.[41] employed NIR spectroscopy coupled with machine learning algorithms to authenticate traditional Chinese medicinal materials and identify their geographical origins. Their results demonstrated that NIR combined with Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) achieved optimal performance in authenticity verification, while the Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) exhibited superior capability in distinguishing plant sources. A salient feature of NIR spectroscopy is its adaptability to variations in environmental factors, such as daytime temperature, relative humidity, and light, making it suitable for use in both laboratory settings and field or outdoor environments. For instance, Wokadala et al.[42] demonstrated the effectiveness of NIR spectroscopy for rapid and nondestructive detection of moisture content during sunlight drying of mango.

NIR spectroscopy can be utilized to determine the drying endpoint, enhance drying process understanding and monitor the drying process in real-time. This approach involves the application of linear techniques, such as partial least squares regression (PLSR) and multiple linear regression (MLR), to facilitate the analysis. Nonlinear techniques such as support vector machines and neural networks have also been employed. Aoki et al.[43] employed NIR spectroscopy and acoustic emission technology for real-time monitoring of particles during fluidized bed drying, and the endpoint of the fluidized bed drying process was determined automatically by using the partial least squares regression (PLSR) discriminant analysis. The process of spray drying is comprised of four sequential steps: the preparation of the spray solution, primary spray drying, the collection of the spray-dried powder, and secondary spray drying. The determination of the secondary drying endpoint offline poses numerous challenges. Near-infrared spectroscopy can be utilized to characterize spray drying[22]. Ikeda et al.[44] employed near-infrared spectroscopy to ascertain the secondary drying endpoint. An online analysis method was developed to enhance the understanding, control, and troubleshooting of the secondary drying process.

The utilization of near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy in the context of agricultural product drying exhibits distinct advantages, though it should be noted that its application is constrained to the realm of spectral analysis. In the subsequent research endeavors, the integration of NIR spectroscopy with alternative data analysis methodologies and detection technologies will persist as the predominant research paradigm. This integration may manifest through the amalgamation of NIR spectroscopy with mid-infrared (MIR) spectroscopy to discern the chemical composition of agricultural products[45], or with electronic nose (E-nose) technology to assess the aroma quality of tea during the drying process[46]. The cost of benchtop NIR spectrometers is a significant barrier to wider adoption, suggesting a future trend toward the use of portable NIR spectrometers by researchers. At present, most portable devices operate within 900–1,700 nm[47] (vs benchtop NIR's 780–2,500 nm), limiting detection of key molecular bonds (e.g., O-H stretching at 1,900–2,500 nm) critical for low-moisture phases (< 5%). Field conditions (dust, humidity > 80%, temperature fluctuations) degrade signal-to-noise ratios by 15%–20%, necessitating frequent recalibration. Portable near-infrared spectrometer can realize real-time and field deployable quality monitoring of small- and medium-sized operations through cost-effective miniaturization, artificial intelligence-driven edge computing, and multi-mode sensor fusion, which is expected to be widely used in the field of agricultural drying.

-

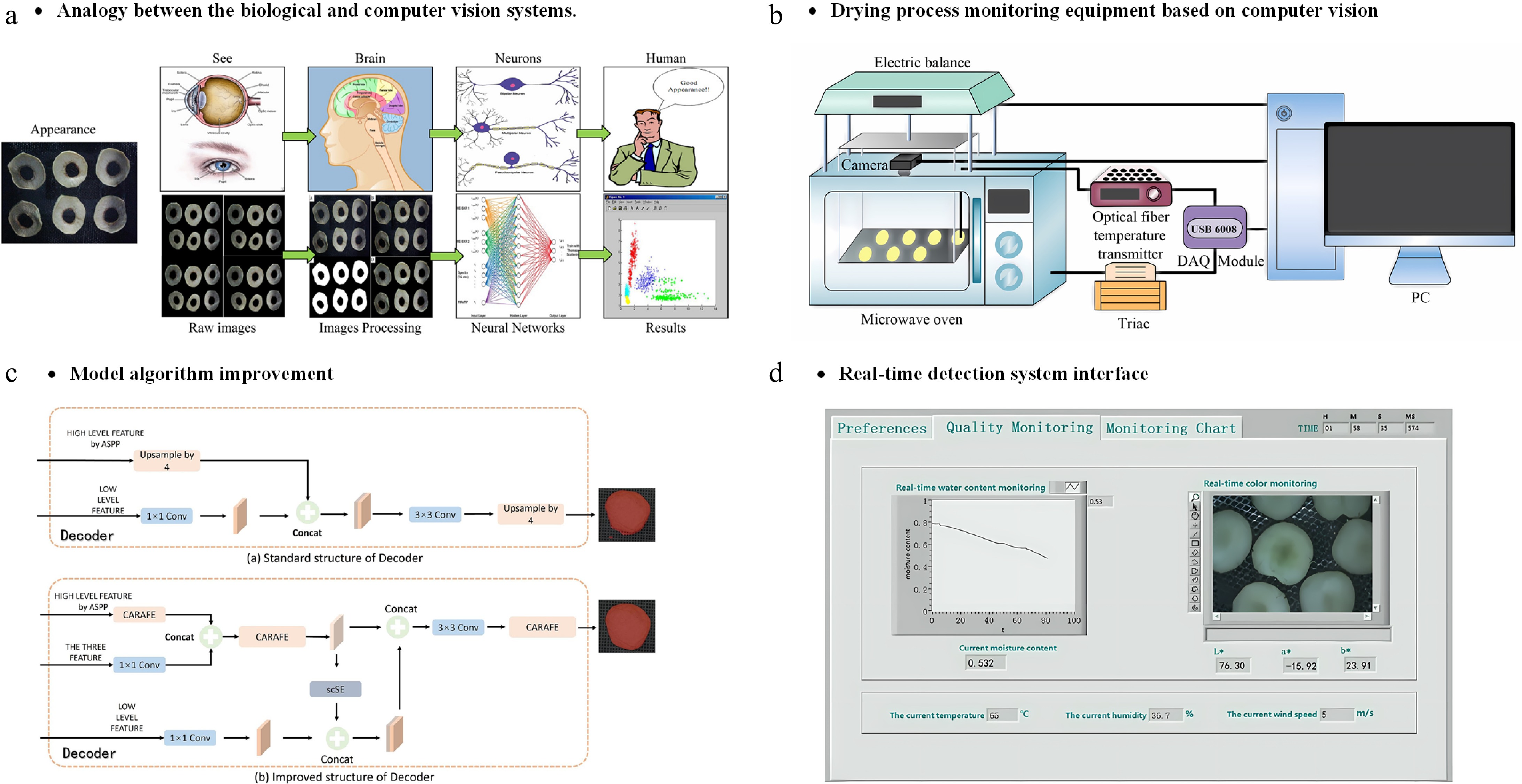

As previously described and illustrated in Fig. 1a, the drying process induces numerous alterations in the mechanical, sensory[48], and nutritional characteristics of produce. Due to their non-destructive, efficient, and in-line nature, computer vision systems have emerged as a significant concern in the food industry for analyzing drying image changes. Figure 4a[49] demonstrates the remarkable similarity between biological and artificial vision systems. Computer vision systems are engineered to emulate the processing and behavior of biological systems with the utmost fidelity. The primary processes encompass image acquisition, image preprocessing, image segmentation, feature extraction, and prediction.

Computer vision systems have been utilized to oversee the drying process of agricultural products. Zhu et al.[50] developed a computer vision online monitoring microwave drying system (Fig. 4b). This system comprises an industrial camera, a microwave drying oven, an online quality inspection unit, a temperature sensor, and vision processing software. These components can also be employed in other continuous drying processes, such as hot air drying and superheated steam drying. Online recognition via computer vision critically relies on model improvements. As shown in Fig. 4c, Guo et al.[51] modified the DeepLabv3+ model to achieve real-time monitoring of the visual quality of king oyster mushrooms. Additionally, human-machine interaction interfaces enhance the accessibility of drying progress tracking. As shown in Fig. 4d, Zang et al.[52] developed an interactive platform for real-time monitoring of color and moisture changes during jujube slice drying, enabling simultaneous observation of drying curves and chromatic transitions.

The study by Xu et al.[53] elucidates the detailed workflow for training computer vision recognition models, demonstrating a systematic approach from data preprocessing to model optimization. Experimental data on image sequences and mass variations of potato slices during drying were systematically collected. As drying progressed, the potato slices exhibited characteristic changes, including dimensional shrinkage, color evolution, and surface hardening. Based on the drying rate curve, the process was categorized into three distinct phases: the constant-rate drying stage (CS), the first falling-rate drying stage (J1), and the second falling-rate drying stage (J2). By refining the YOLOv7-tiny model, an optimal recognition model was developed, enabling real-time image analysis to accurately identify the current drying stage. This advancement facilitates process optimization to enhance product quality, reduce drying duration, and minimize energy consumption.

During the drying process of agricultural products, color, shrinkage, texture, moisture content, and cosmetic defects are all key characteristics of the final product. These characteristics are indicative of biochemical reactions that occur during processing. Therefore, Chakravartula et al.[54] developed an intelligent monitoring system for carrot drying. This system utilizes computer vision to monitor the color and size of the drying process. In a similar vein, Wang et al.[55] achieved continuous monitoring of color change and shrinkage during the peony flower drying process, thereby enhancing the drying quality through measurement control. In the hot air drying process of shiitake mushrooms, computer vision was able to obtain the change of wrinkling surface area ratio[56], which was then used as a basis to improve the drying process. Furthermore, the technology has been employed to monitor foreign matter and defects of particles in the freeze-drying process[57]. Additionally, it has been utilized to monitor the texture of apple slices during the drying process[58], the shrinkage of sweet potatoes[59], the moisture content of sea buckthorn fruit[60], and the color change of bananas or papayas[61,62].

The integration of computer vision with machine learning algorithms has demonstrated significant potential in agricultural drying monitoring. Jia et al.[63] developed predictive models for moisture content variation and color changes in apple slices during drying using machine learning algorithms. Their results indicated that the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network achieved superior performance, while other models such as the Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN), and Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) also demonstrated effective predictive capabilities. In a study on blueberry drying with far-infrared-assisted pulsed vacuum technology, Liu et al.[64] used the SALP swarm algorithm and extreme learning machine (ELM) to establish a prediction model for effectively predicting the shelf life of blueberries in the study of far-infrared assisted pulsating vacuum drying of blueberries.

The integration of computer vision with artificial intelligence[65−67] holds considerable promise as a future development, serving as a promising tool for the intelligent and accurate monitoring of food drying processes. A significant untapped potential exists in the image data captured during various agricultural drying and processing operations[49]. The integration of computer vision techniques with real-time regulation of drying parameters through intelligent control methodologies, such as fuzzy control[68,69], holds considerable promise. This approach is poised to infuse novel insights and capabilities into the realm of intelligent drying[70]. As demonstrated by Cao et al.[71], an online monitoring platform for the drying process was developed by integrating machine vision and automatic weighing technology, achieving the online prediction of nutritional quality. However, it is important to acknowledge the inherent challenges posed by the complexity of the drying environment, including elevated temperatures, superheated steam, and dust interference, which serve as significant limitations to the full potential of computer vision technology. Additionally, the algorithm generalization is inadequate, as the appearance of different varieties and origins of agricultural products varies significantly, making it challenging for a single model to adapt.

-

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) represents a sophisticated technique that integrates the strengths of spectroscopy and computer vision techniques[72]. It possesses the capability to capture internal spectral data and external images of target samples across diverse spectral bands[35]. At the molecular level, hyperspectral techniques can ascertain compositional information of samples based on molecular bond energy changes in agricultural products. At the macro level, electromagnetic waves can be reflected and transmitted akin to light. The analysis of reflected waves provides insights into the external quality of the sample, including surface texture, color, shape, and defects. In contrast, the transmission mode enables the acquisition of information regarding the internal qualities, such as the chemical composition, of the sample. The integration of reflective and transmissive modes facilitates the acquisition of more precise data, thereby circumventing limitations imposed by thickness.

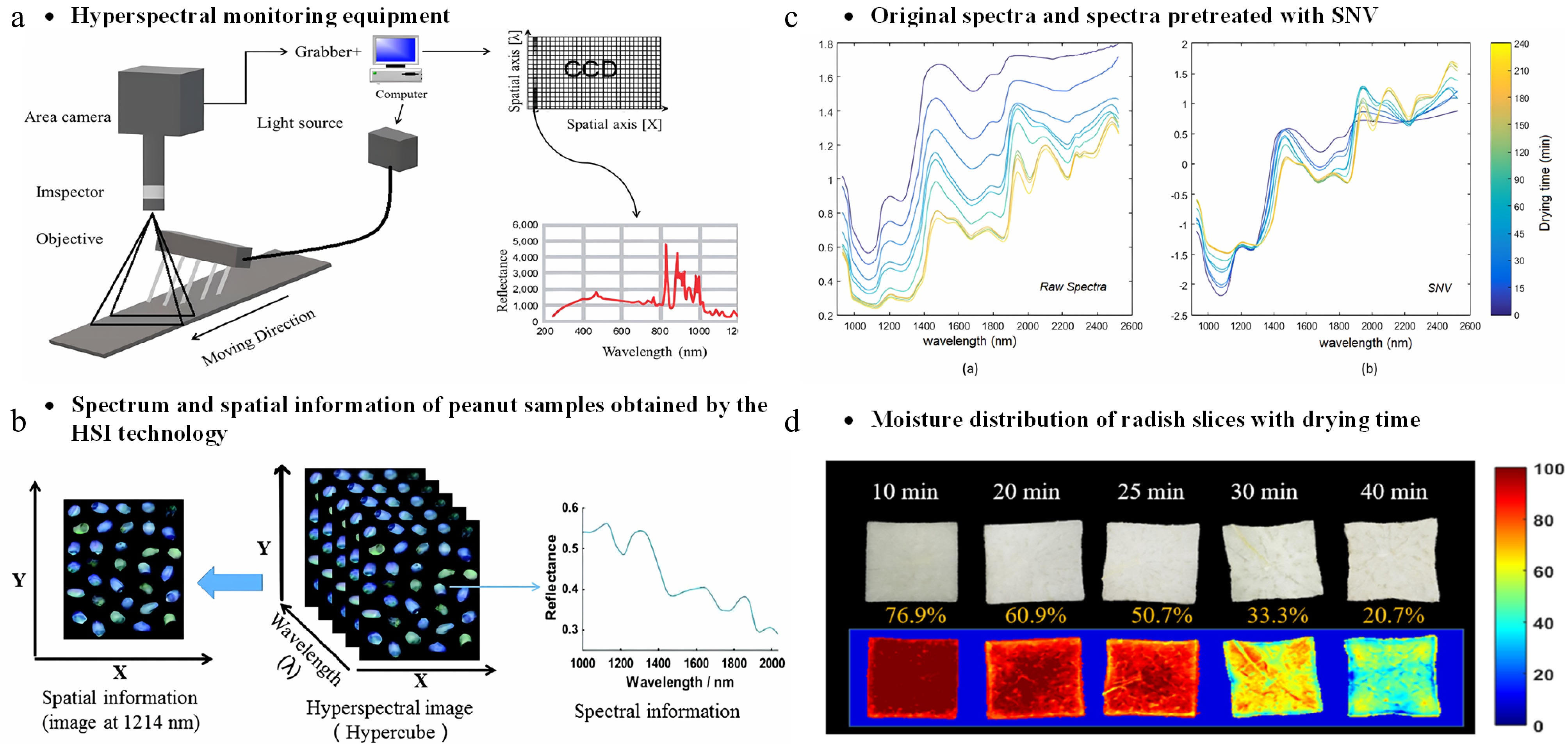

The composition of the hyperspectral imaging system is typically characterized by a series of components, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. These components include an imaging spectral camera, a lens, a halogen light source, a computer, and the associated software. The acquisition process is conducted within a closed and opaque black box environment, facilitating the acquisition of original hyperspectral images. As illustrated in Fig. 5b, the HSI technique facilitates the acquisition of both spectral and HSI images, thereby elucidating the chemical composition and physical properties of agricultural products. In recent years, HSI has seen significant advancements in its application for the monitoring of the drying process, with a particular focus on moisture, nutrient content, and rehydration prediction. In a seminal study, Taghinezhad et al.[72] employed hyperspectral imaging to assess the moisture content of the drying process and reported the optimal wavelengths capable of accurately predicting the moisture content. Lee et al.[75] developed a model to visualize the moisture content of radish slices during the drying process by processing hyperspectral images (Fig. 5d). Hyperspectral imaging has also been employed to detect color, moisture content, and texture in banana chips during the drying process[76]. Furthermore, hyperspectral imaging has been employed for rehydration rate detection in the context of dehydrated beef[77]. In a similar vein, Xu et al.[78] utilized hyperspectral techniques to predict the nutrient content and geographic origin of goji berries.

Figure 5.

Hyperspectral detection of drying process. (a) Hyperspectral monitoring equipmentr[73]. (b) Spectrum and spatial information of peanut samples obtained by the HSI technology[74]. (c) Original spectra and spectra pretreated with SNV[79]. (d) Moisture distribution of radish slices with drying time[75].

In addition, in recent times, the combination of hyperspectral detection and data processing methods to construct a recognition model has become a prevalent research approach. As illustrated in Fig. 5c, the preprocessing of spectra using SNV (standard normal variation) can effectively eliminate or minimize irrelevant information. The identification of fruit quality was achieved through the integration of hyperspectral imaging with the LS-SUM classification algorithm. Yu et al.[80] employed hyperspectral imaging (HSI) technology to detect the moisture content of soybeans. They proposed an algorithm termed BFWA (Best-Feature Wavelength Algorithm) for extracting optimal wavelengths from spectral data. After selecting 12 critical wavelengths, a moisture prediction model was established using Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR), which demonstrated superior accuracy and stability compared to other wavelength selection algorithms, such as the Successive Projections Algorithm (SPA) and Uninformative Variable Elimination (UVE). The processing of hyperspectral images using deep learning[81,82], and artificial intelligence[83] techniques to predict moisture and nutrient changes in the drying process of agricultural products is also a popular research area. In their study on the hot air drying of red dates, Liu et al.[82] employed hyperspectral imaging (HSI) technology combined with a deep learning model to predict quality parameters across different drying stages. The results demonstrated that the developed deep learning model outperformed standalone Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) models in predicting red date quality, achieving visualization of the spatiotemporal distribution of quality parameters throughout the drying process. The spectral data processing methods of hyperspectral and near-infrared spectroscopy have similarity, as evidenced by the use of chemometric methods[84], combined with electronic nose technology[85] for quality detection.

Despite the numerous advantages and enhanced detection accuracy afforded by hyperspectral technology, it is currently confronted with several challenges. These include the prolonged data acquisition time, the intricate data processing procedures, and the complex drying environment, which collectively restrict its application in online processing. Moreover, the substantial expense of hyperspectral instrumentation hinders its promotion in industrial settings. To overcome these obstacles, there is an imperative for the advancement of hyperspectral technology and the enhancement of its data processing capabilities. This can be achieved through the development of portable hyperspectral equipment, the development of integrated intelligent drying equipment, and the increased use of machine learning[86].

-

This paper presents a summary of recent advancements in monitoring techniques for the drying process of agricultural products. Specifically, it explores the successful application of dielectric property detection techniques, near infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, computer vision, and hyperspectral techniques in the monitoring of moisture content, moisture distribution, defects, and quality during the drying process of agricultural products. The paper also discusses the development of a drying process monitoring system with innovative monitoring methods, which is of great significance to the development of agricultural products drying technology. The system has been implemented to enhance product quality, reduce drying energy consumption, and improve understanding of drying processes and procedures.

Despite the achievements of these technologies in monitoring the drying process of agricultural products, numerous difficulties and challenges remain to be addressed for their full implementation. Non-destructive testing technologies, for instance, encounter complex environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, present in the drying equipment when integrated with drying technologies. Additionally, the online application of these technologies necessitates substantial data processing, particularly in the case of hyperspectral and computer vision technologies. The resolution of these challenges necessitates the development of cost-effective, portable inspection equipment. In addition to enhancing the computing capabilities of computers, the integration of fuzzy control, multi-parameter, and multi-modal data processing methods, machine learning, genetic algorithms, and other artificial intelligence techniques is imperative to facilitate precise online monitoring. The synergistic innovation of multiple NDT technologies will usher in a new era of intelligence and precision for the drying of agricultural products.

The authors express their appreciation to the Tianjin Science and Technology Project (Contract No. 23YDTPJC00630), the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia (Grant No. 2023QN03060), the Scientific Research Projects of Tianjin Municipal Education Commission (Contract No. 2023ZD002), and Development Fund Project for Young Scientific and Technological Talents of Tianjin Agricultural College (Grant No. 2025QNKJ13).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xu X, Liu J, Xu Q, Wang R; methodology and investigation: Xu X, Liu J, Xu Q; literature search, analysis: Xu X, Liu J, Wang R; visualization: Xu X; writing-original draft: Xu X; supervision, resources, writing-review, and editing: Liu J, Xu Q, Wang R. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xu X, Liu J, Xu Q, Wang R. 2025. Recent developments on detection technology for the drying processes of agricultural products. Technology in Agronomy 5: e013 doi: 10.48130/tia-0025-0008

Recent developments on detection technology for the drying processes of agricultural products

- Received: 25 February 2025

- Revised: 25 April 2025

- Accepted: 21 May 2025

- Published online: 26 September 2025

Abstract: Fresh agricultural products are prone to post-harvest decay due to their high water content and high endogenous enzyme activity. Drying is a critical step in the storage and value-added processing of agricultural products. However, conventional drying methods do not account for the variations in drying stages, and the empirical model has inherent limitations that fail to accurately reflect the actual drying state of the material. This results in prolonged and inefficient sample drying, leading to suboptimal quality outcomes. To address these challenges and enhance the drying efficiency and quality of agricultural products, this review systematically examines innovative monitoring technologies applied during the drying process. It analyzes the characteristics, applicability, and limitations of dielectric properties, near-infrared spectroscopy, computer vision, and hyperspectral imaging. A critical evaluation of the advantages, disadvantages, and interconnections among existing monitoring technologies was conducted, synthesizing them into an integrated framework. Finally, prospects for future research directions in agricultural product drying processes are proposed, focusing on the development of multimodal coupled models based on artificial intelligence algorithms, with the aim of providing a reference for further AI applications in this field.

-

Key words:

- Drying /

- Agricultural products /

- Nondestructive testing /

- Quality monitoring