-

Artificial Intelligence (AI), which leverages computational power to mimic human behavior, includes subfields like machine learning, deep learning (DL), and natural language processing. It demonstrates its utility in diverse sectors such as medicine and agriculture, revealing boundless potential for innovation[1]. Vegetables are an indispensable source of nutrition in global diets, supporting the diversity and stability of the world's food systems, accounting for a production volume of 11.5 billion tons from 27 major crops worldwide in 2020, driving substantial economic impact. However, issues such as rising labor costs and low production efficiency have, to some extent, constrained the high-quality development of the vegetable industry. As the 21st century progresses, the development of technologies such as high-throughput sequencing has driven advancements in vegetable science at the molecular level[2]. Inefficiencies in vegetable production, particularly in phenotypic data collection, the complexity of handling omics big data, the lack of intelligent production systems, and prolonged breeding cycles, have become increasingly prominent. Notably, the evolution and application of AI technologies in related areas have significantly alleviated these challenges[3].

AI technology has permeated various aspects of vegetable research. Firstly, the efficient identification of phenotypic traits is crucial for the rapid and accurate determination of superior vegetable quality, with image processing and intelligent detection technologies driving advancements in this field[4]. Secondly, the rapid development of high-throughput detection technologies has generated massive datasets, while the optimization of AI algorithms such as machine learning and DL has provided efficient tools for in-depth research and application of multi-omics data[5]. Thirdly, the continuous exploration of data-driven cultivation techniques has facilitated the advancement of technologies such as intelligent robots and smart irrigation systems[6]. Fourthly, in the face of protracted breeding cycles or the limitations of molecular marker-assisted breeding for quantitative traits, the integration of AI with machine learning and DL algorithms has opened new vistas for more precise breeding designs, holding significant research value for accelerating genetic improvement in the future[7].

Here, the application of AI in vegetable planting will be systematically reviewed from the aspects of phenotypic data acquisition, multi-omics data analysis, intelligent vegetable production, vegetable breeding, etc., simultaneously, and reasonable recommendations are proposed.

-

In the realm of vegetable breeding and cultivation management, the precise collection of phenotypic data has become increasingly critical, encompassing multifaceted traits such as plant morphology, yield, and resistance. However, traditional manual data collection methods have been constrained by their inefficiency and subjectivity, limiting their practical application[8,9]. With the growing demand for high-precision, large-scale phenotypic data in vegetable breeding, traditional approaches struggle to meet the requirements of actual development[10]. In light of this, AI technologies, particularly computer vision (CV) and DL have provided innovative solutions for the automation, dynamism, and precision in the collection of phenotypic data (Table 1). These two technologies have played an important role in aspects such as high-efficiency phenotypic identification[11,12]. The former typically requires carrying out tasks such as color-based pixel thresholding or pixel counting according to user-designed algorithms, whereas the latter can typically be executed without user-defined algorithms, building models based on big data to make independent decisions or predictions[13]. DL is an important part of machine learning, including neural networks (RNN), generative adversarial networks (GAN), graph convolutional networks (GCN), etc. Compared with traditional machine-learning methods such as GBLUP, support vectors, and random forests, it can handle more complex non-linear problems. Although the interpretability of DL models is relatively poor, they have achieved remarkable results in fields such as image recognition, speech recognition, and natural language processing, and are suitable for integrated analysis with CV data[14].

Table 1. Comparative analysis of four common AI techniques.

Method Typical algorithms Applications Pros Cons Model complexity Machine learning Linear Reg., Log. Reg., DT, RF, SVM, KNN, etc. Classification, Regression, Clustering, Rec. Systems, etc. Algorithm simplicity, interpretability Limited handling of high-dimensional and non-linear problems Low Deep learning CNN, RNN, LSTM, GAN, etc. Image Recognition, NLP, Speech Recognition, Video Analysis, etc. Automatic feature extraction, effective for high-dimensional and non-linear problems Requires large datasets and computational power, complex models Very high Computer vision Edge Detection, SIFT, SURF, YOLO, SSD, Mask R-CNN, etc. Image Classification, Object Detection, Segmentation, Face Recognition, etc. Specialized for image processing, strong algorithmic focus Relies on manually designed features, limited generalization Medium Image learning Image Enhancement, Repair, Generation (e.g., GAN),

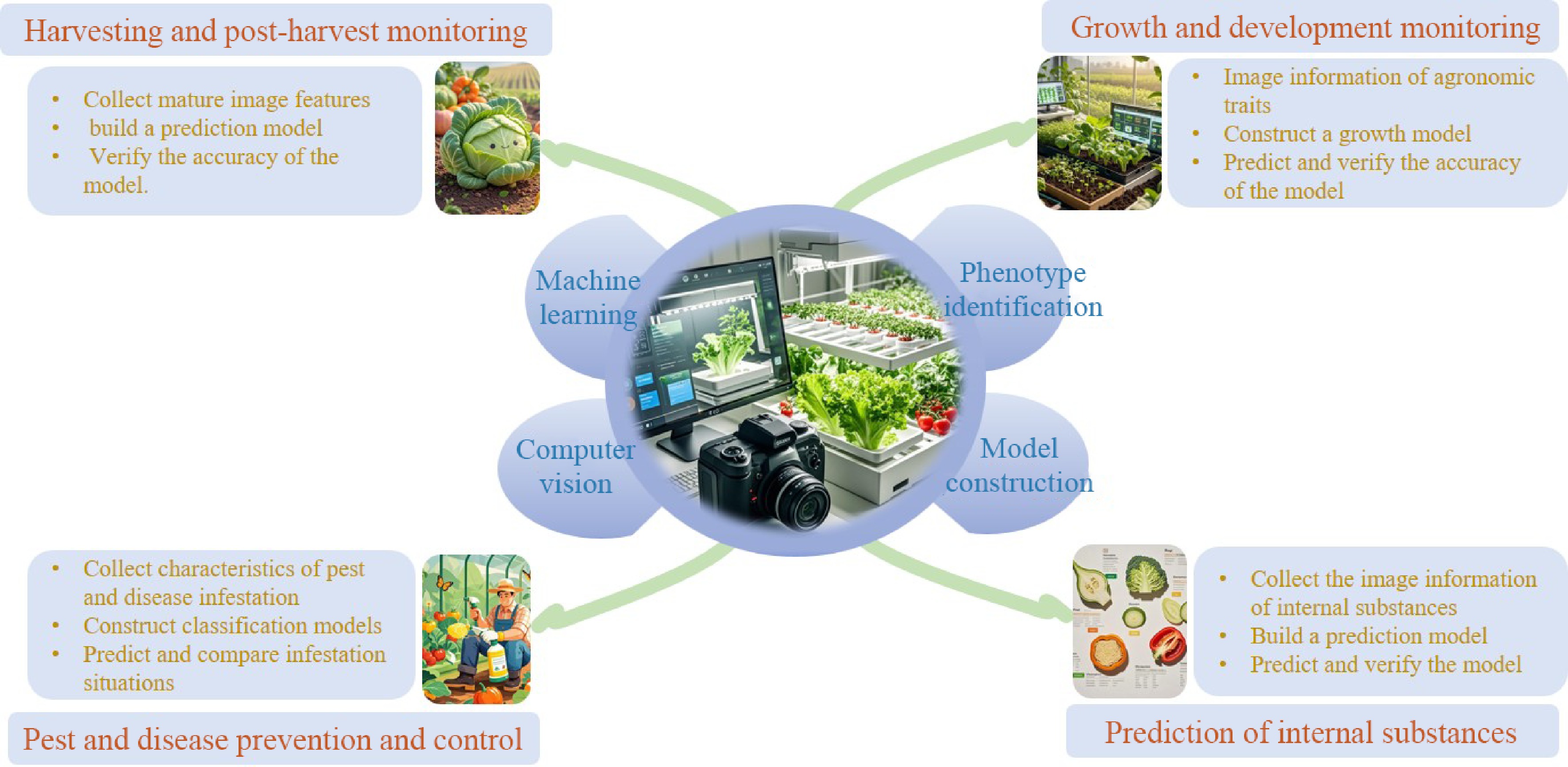

Super-Resolution, etc.Image Enhancement, Repair, Generation, Medical Image Analysis, etc. Focuses on image data, generates high-quality images Requires large datasets, high computational complexity High The integration of CV and DP has made significant advancements in the fields of vegetable growth, harvesting, pest and disease control, and prediction of internal substances (Fig. 1). Firstly, in vegetable growth and development research, researchers have utilized object detection and stereo cameras to acquire color images and depth maps, enabling non-contact classification and length measurement of important solanaceous crops such as cucumber (Cucumis sativus), eggplant (Solanum melongena), tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum), and pepper (Capsicum annuum) within a 60 cm range[15]. Similar studies have been applied to cucurbit crops, where improved YOLO sequence detection algorithms have achieved high-efficiency detection of the growth status of bitter melon (Momordica charantia), cucumber, muskmelon (Cucumis melo), and other varieties[16,17]. Additionally, in lettuce (Lactuca sativa), significant progress has been made in estimating key phenotypic traits using RGB images and Mask R-CNN[18]. More interestingly, the development of a plant-organ-growth monitoring system based on flexible wearable strain sensors (Patent: CN202210510752.7) will further provide an efficient tool for intelligent growth monitoring of vegetables. Secondly, in post-harvest vegetable research, Zarnaq et al.[19] extracted color and texture features from images of parsley (Petroselinum crispum) and processed these feature data using Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and combining various machine learning algorithms, including Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) neural networks, they found that the LDA feature selection method combined with MLP yielded the best detection results, thereby achieving efficient freshness detection of parsley. Thirdly, CV and DP technologies have also played crucial roles in pest and disease detection. Studies utilizing CNN, MC-UNet, and EffiMob-Net models have made significant advances in detecting vegetable pests and diseases[20,21]. The combination of high-throughput phenotyping system PlantArray and transcriptome data provides an effective tool for elucidating the mechanisms underlying leguminous plants' response to drought stress[22,23]. This system has been applied in crops such as watermelon water-use monitoring[24]. Fourthly, based on image information and model construction, it is also possible to predict the internal composition of vegetables, Ariza et al. [25] found that the MTSC method significantly improves the accuracy of predicting concentrations of 11 elements (such as Cd, K, B, Fe) in tomatoes, while Malounas et al.[26] achieved efficient prediction of dry matter in broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica), leeks (Allium tuberosum), and mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus). It is noteworthy that, with the accumulation of abundant data, further strengthening the construction of intelligent platforms has become imperative. For example, The Climate Corporation's Climate FieldView platform, and Huazhong University's AutoGP system serve as exemplary models for long-term efficient phenotyping[22]. In vegetable crop research, which lags in this area, the development of the CucumberAI system provides a good example[27]. Overall, the combination of CV and DP technologies holds promise for achieving efficient detection of vegetable crop growth stages, which will undoubtedly play a larger role in advancing the industry.

-

The rapid development of omics technologies has generated massive datasets, making efficient data processing an important research topic. AI technology provides effective tools for this work, achieving significant progress in areas such as genetic mechanism analysis and developmental regulation[28]. In genomics research, the Deep Neural Network Genomic Prediction (DNNGP) model has shown strong potential, effectively integrating multi-omics data to improve the accuracy of predicting agronomic traits in plants, particularly suitable for large-scale breeding data[5]. The sequencing of the spinach genome has provided a crucial foundation for downy mildew resistance research, while the PhytoExpr framework has enabled precise prediction of cis-regulatory sequences[29]; these advancements have also been applied to studies on tomatoes and peppers[30]. In transcriptomics research, combining high-throughput phenotyping tools with machine learning algorithms has significantly improved breeding efficiency and the development of systems biology[31,32]. In metabolomics research, the integration of machine learning techniques with sensory evaluation has enabled the precise identification of flavor compounds in crops like Solanum nigrum, screening out key metabolites that influence flavor, and providing new criteria for breeders[33]. Additionally, the establishment of greenhouse tomato flowering rate prediction models using LASSO regularized linear regression accurately predicts flowering rates, identifies metabolic markers, and reveals links between metabolome and agronomic traits[34]. In proteomics research, DL techniques have been applied to characterize and redesign patatin, the major storage protein in potatoes, offering new possibilities for protein improvement in the food industry[35]. Epigenetics research has seen AI applications revealing the critical roles of DNA methylation and histone modifications in plant development processes, significantly enhancing research efficiency[36]. However, in related research, due to the differences in various algorithms, it is necessary to conduct comparative analyses combining multiple methods to obtain the optimal model, thereby achieving more effective in-depth mining of omics data (Table 2). Despite significant advances in AI-driven multi-omics research in vegetables, challenges remain in terms of cross-species and cross-environment model generalization capabilities, big data acquisition and processing, and AI model interpretability. With continuous algorithm optimization and data accumulation, these issues are expected to be gradually resolved, promoting overall progress in vegetable science.

Table 2. Summary of research progress in vegetable crop multi-omics studies based on AI technology.

Omics field Research topic Research subjects AI methods Application scenarios Key findings Methodological differences Ref. Genomics Novel Whole Genome Selection Method DNNGP Tomato, and others Deep neural network (DNN) Enhancing agronomic trait prediction accuracy DNNGP outperforms on large-scale datasets Higher accuracy but slightly higher computational complexity compared to traditional methods [5] Genomics GS-based tomato fruit quality trait prediction Tomato, pepper, and others Regression models (rrBLUP), classification models (RF, SVC) Optimizing breeding strategies Multi-trait GS model shows stronger prediction for certain traits Random forest and SVM excel in classification tasks, while rrBLUP is more stable in regression tasks [30] Genomics Identification of powdery mildew resistance loci in spinach Spinach GWAS, machine learning (Bayesian B, rrBLUP) Identifying resistance markers Bayesian B model exceeds in resistance prediction High accuracy but longer computation time for Bayesian B model [29] Transcriptomics De novo genome construction of garden mustard Garden mustard Gene prediction (AUGUSTUS), machine learning (logistic regression) Providing genomic resources for breeding and evolutionary studies Identification of 599 potential resistance genes and 459 pre-miRNA encoding sites Logistic regression performs significantly in miRNA site prediction but requires extensive training data [31] Metabolomics Exploration of biological markers for cruciferous vegetable consumption Broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, radish, mustard, and others Machine learning (random forest classifier) Discovery of food consumption biomarkers Successful identification of metabolites associated with specific cruciferous vegetable consumption High accuracy of random forest classifier in identifying marker metabolites, but risk of overfitting [34] Proteomics Redesign of potato tuber storage proteins Potato Deep learning (alphaFold2, rosetta) Improving functional properties of potato flour Engineered patatin variants significantly enhanced dough viscosity and nutritional value AlphaFold2 provides accurate structure prediction, whereas Rosetta's designed variants are computationally intensive [35] Epigenomics Rational design of plant cis-regulatory sequences Tomato, sunflower, soybean, spinach among 17 plant species Deep learning (transformer) Modeling and designing cis-regulatory variations PhytoExpr model achieves over 85% top-1 accuracy in cross-species mRNA abundance prediction Transformer model excells in multi-task learning but requires substantial computing resources [36] -

In the transition and upgrading of modern agriculture, intelligent technologies play a crucial role in enhancing agricultural precision and efficiency, driving the transition toward sustainable and smart farming. Key research in this area primarily manifests in the following ways:

Integration and application of intelligent monitoring and agricultural remote sensing technologies

-

Remote sensing enables real-time monitoring of crops across 'ground-level, low-altitude, and satellite' dimensions[37], in the vegetable industry, the integrated application of intelligent monitoring and agricultural remote sensing technologies has notably improved the precision and efficiency of vegetable production. For instance, researchers combine remote sensing technology and machine learning to achieve accurate prediction of viruses in vegetable crops such as tomato[21,38], and combine LiDAR point cloud and DL technology to achieve the prediction of the plant height and canopy area of tomatoes, eggplants, and cabbages[39]. The continuous advancement of remote sensing technologies, such as optical remote sensing (including LiDAR, spectral analysis, infrared imaging, and visible light detection)[40,41], smart drone technology[42], satellite remote sensing[43], and ground-based sensors[44] has been rapidly evolving, accelerating the development and utilization of intelligent monitoring tools. By further integrating big data analytics and other advanced methods, these technologies have, to a certain extent, addressed the issues of high labor intensity and low efficiency in traditional agriculture. This progress has provided robust support for the sustainable development of modern agriculture.

Innovative practices in smart agricultural machinery and agricultural robots

-

The development and application of smart agricultural machinery and agricultural robots have significantly advanced the automation and intelligence of vegetable production. Yan et al.[45] developed grafting robotics technology that combines machine vision and automation, considerably enhancing the efficiency and survival rate of vegetable crop grafting. Paradkar et al.[46] designed an automated metering device for vegetable transplanters, enabling precise transplanting of vegetable seedlings and advancing vegetable cultivation towards higher efficiency and precision. Furthermore, the design and implementation of smart agricultural robots like the automated harvester Vegebot[47], the intelligent weed control system[48], and the growth monitor TerraSentia have significantly decreased the reliance on manual labor and resources.

Construction and application of precision agricultural management systems

-

Precision agriculture management is a technology-driven approach to agricultural management[49]. Firstly, in terms of environmental monitoring and control, Lestari et al.[20] utilized CNN algorithms to classify vegetable pests, validating their high accuracy through cross-validation. Additionally, Internet of Things (IoT)-based intelligent pest management systems for precision agriculture are continuously improving[50]. Secondly, in the area of vegetable growth monitoring and data-driven regulation, combining image acquisition with DL and other technical means enables real-time monitoring of crop growth status. Significant progress has also been made in full-chain quality monitoring using IoT, such as the image processing-based Android application developed by Tata et al.[51], which can perform real-time quality classification and grading of vegetables, ensuring their quality and market competitiveness. On this basis, building efficient platforms facilitates comprehensive monitoring of the entire vegetable industry chain from sowing to harvesting, thereby strengthening and advancing the research and application of precision agriculture in vegetable production.

-

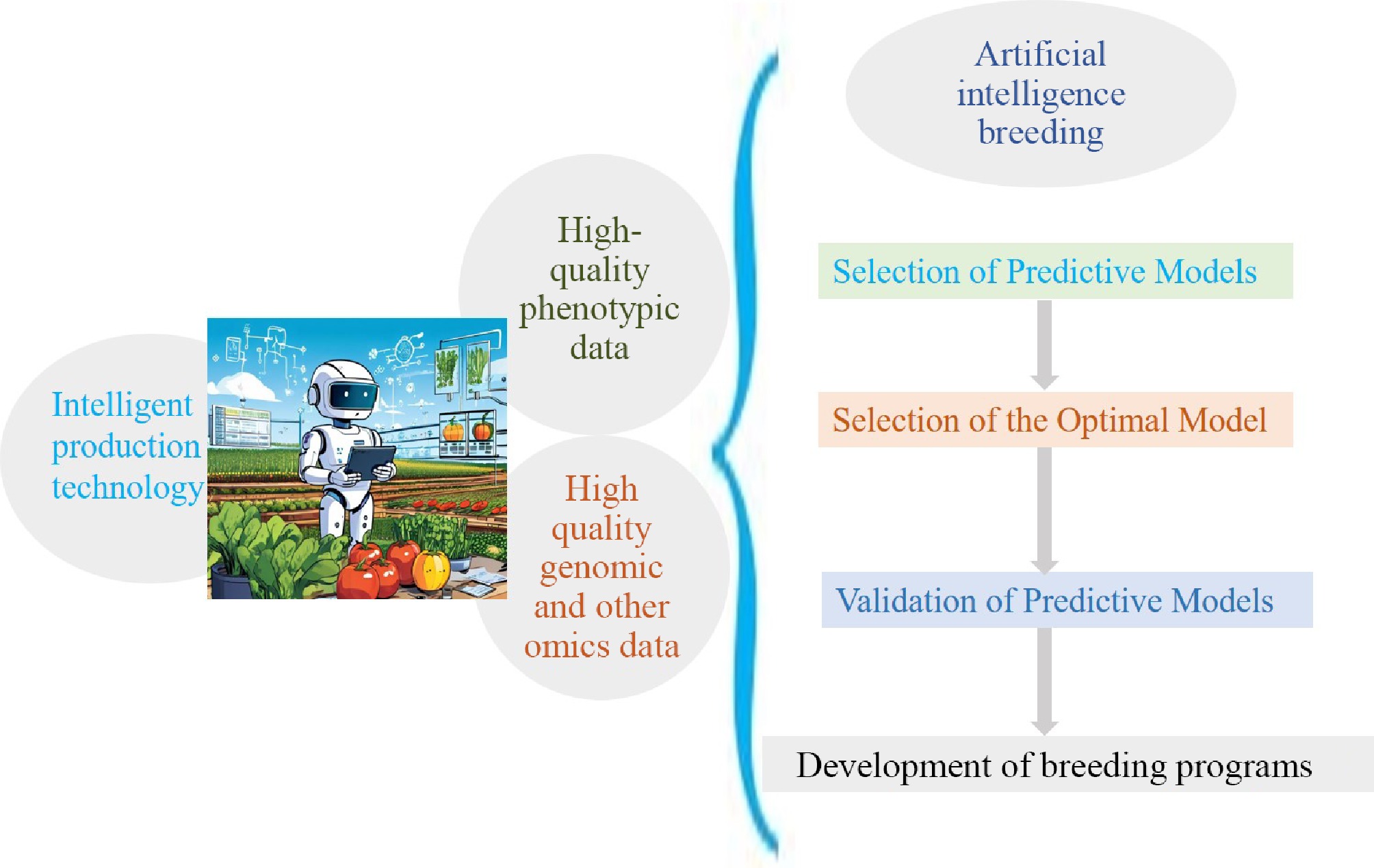

Within the specialized domain of vegetable breeding, the integration of AI has precipitated a transformation of unparalleled magnitude (Fig. 2). At the heart of this evolution is the application of genomic selection, a critical technique that harnesses AI to decode the intricate genetic blueprint of plants. The seminal work by Bhat et al.[7] underscores the transformative potential of AI in vegetable breeding, as it elucidates the meticulous process of identifying genetic markers with a high degree of precision. In a correlational study, Kim et al.[52] utilized genomic selection models to predict capsaicin content in chili peppers, demonstrating the formidable capabilities of AI algorithms in trait prediction and their potential for swift application in breeding programs. This underscores the substantial efficacy of AI technology in optimizing vegetable traits and augmenting genetic gains, serving as a pivotal scientific foundation for informed breeding decisions.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram illustrating research on the application of AI technology in breeding and related areas.

The issue of multifactorial influence is a significant challenge in model prediction, making the selection of predictive models crucial. It often requires the integration of multiple models to achieve the best predictive outcomes. For instance, Lara et al.[53] combined various predictive models to investigate the predictive power of genomic selection in polyploid species, elucidating how these models are affected by factors such as genetic heterogeneity and environmental adaptability.

Validation of models is an indispensable phase in the AI-assisted breeding process, ensuring the reliability and precision of predictions. Researchers typically employ rigorous cross-validation methodologies to evaluate the performance of predictive models[54]. In the study by Guo et al.[54], tenfold cross-validation was utilized to verify the accuracy of different predictive models in the context of crop trait expression, facilitating the subsequent refinement and optimization of the models. Through the iterative enhancement of these models, researchers can progressively fortify their predictive capabilities, aligning them with the practical requisites of breeding while navigating the dynamic landscape of vegetable genomics.

-

Under the rapid development of AI, the vegetable industry is poised for significant upgrades. Based on the opportunities and challenges outlined above, it is crucial to prioritize big data mining and large-scale model construction. Proactive measures and solutions must be implemented to address these challenges.

Data acquisition

-

Accurate phenotypic data acquisition remains a major challenge due to the variability in the growth and development of different vegetable crops across diverse environments. Additionally, environmental factors often interfere with phenotypic data collection using sensors and image processing technologies. To address these issues, integrating multi-source data such as imaging sensors and satellite remote sensing can enhance the collection and identification of phenotypic data. Long-term, multi-location monitoring, combined with region-specific requirements, can further improve the accuracy of phenotypic data acquisition.

Noise and interference in phenotypic data can reduce model accuracy. Therefore, advancing data denoising and preprocessing technologies is another critical focus in vegetable phenomics research. The lack of standardized data-sharing platforms also limits comprehensive phenotypic data acquisition. Establishing robust phenotypic data-sharing platforms and unifying data collection protocols will facilitate higher-level data sharing and utilization.

Model construction

-

Single models are often insufficient, and the complexity of DL models makes them difficult to interpret. Therefore, it is essential to compare and analyze multiple prediction methods and develop more adaptable, efficient, and user-friendly machine learning technologies. In breeding research, model predictions often overlook the experience of breeders, relying instead on procedural and data-driven analyses. Future research should emphasize interdisciplinary collaboration to incorporate diverse expertise, thereby enriching the breadth and depth of models and enhancing the application of machine learning in vegetable research.

Future prospects

-

The potential of AI in the vegetable industry is vast, with breakthroughs expected in multiple areas. In AI-driven cultivation models, region-specific unmanned management solutions can be developed, potentially achieving integrated and fully automated vegetable production. In AI-powered whole-genome design breeding, combining breeder expertise, genomic data, phenotypic data, and gene-editing technologies can enable targeted improvements in agronomic traits, significantly enhancing breeding efficiency. Additionally, non-destructive testing technologies can enable high-efficiency monitoring of internal metabolites and proteins in vegetables, further promoting the production of high-quality crops. Cross-disciplinary collaborations with meteorology, microbiology, and other fields will unlock endless possibilities for industry advancement.

In conclusion, leveraging AI technologies in the vegetable industry will drive innovation and efficiency, paving the way for a more sustainable and productive future.

This work was supported by the Jiangsu agricultural science and technology innovation fund [CX(24)3019]; the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (BK20230751), China Agriculture Research System, (CARS-23-G42), and Jiangsu key R&D plan (BE2023349).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: formal analysis, data curation, writing – original draft: Gong C; funding acquisition, data curation, writing – review and editing: Diao W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Gong C, Diao W. 2025. Artificial intelligence in vegetable crops: recent advances and prospects. Vegetable Research 5: e014 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0012

Artificial intelligence in vegetable crops: recent advances and prospects

- Received: 18 November 2024

- Revised: 20 February 2025

- Accepted: 11 March 2025

- Published online: 20 May 2025

Abstract: Vegetables play a critical role in the agricultural economy, food security, and ecological sustainability. The acceleration of productivity enhancement in high-quality vegetable industries should align with the development of the new era. Notably, artificial intelligence (AI) technology demonstrates significant potential in vegetable industry applications. This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of emerging AI-driven innovations in vegetable crop research, exploring their key applications in phenotypic data acquisition, genomics, intelligent production, and high-quality variety breeding. Additionally, reasonable suggestions are provided for data collection and model construction. In summary, by integrating cutting-edge progress and prospective analysis, this review provides a practical technical path for the construction of accurate and sustainable vegetable production systems driven by AI technology.

-

Key words:

- Vegetables /

- Artificial Intelligence /

- Advances /

- Prospects /

- AI