-

Retinal detachment (RD) is defined as a separation of the neurosensory retinal layer from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in the presence of a full-thickness retinal break[1]. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) is the most common type of RD, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 10,000 individuals[2,3]. The pathogenesis of RRD primarily involves the formation of a retinal hiatus (RH) due to the exertion of a certain pull force[4]. The liquefied vitreous body enters the upper cortex of the retinal nerve through the hiatus and causes the retinal neuroepithelium and RPE to continue to separate[5,6]. RRD constitutes one of the most common sight-threatening ophthalmic surgical emergencies[7]. Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) is a surgical intervention employed for the repair of RRD, which involves the removal of the vitreous that induced traction on the retina, thereby leading to RH and RD[5].

The selection of an endotamponade agent for PPV is a pivotal consideration in retinal surgery. Commonly utilized tamponade agents include gases with varying durations of intraocular retention and silicone oil (SiO)[8]. Gas is an indispensable material for eye filling in PPV, as it must be transparent, non-toxic, sufficient in size, and maintained for a considerable time. Gas bubbles provide high surface tension, effectively sealing retinal breaks against the eye wall. This enables the RPE to pump subretinal fluid into the choroid and maintain retinal attachment until the retinopexy scars form[5]. Commonly used long-acting gases include sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), hexafluoroethane (C2F6), and perfluoropropane (C3F8), with durations ranging from several weeks to 1–2 months[9,10]. Air is generally not used due to its short half-life, which is insufficient to achieve effective tamponade pressure[11,12]. SF6 has a low expansion coefficient and an effective peak pressure lasting approximately 10 d, which minimally impacts vitreous and intraocular pressure. In contrast, C2F6 and C3F8 exhibit a larger expansion coefficient, requiring 1−2 months to fully absorb postoperatively[13−15]. Among these gases, C3F8 is a relatively ideal gas and has been used internationally since 1983.

Currently, clinical drug research is mainly conducted through RCT studies, which is the standard method for drug clinical evaluation. However, there is no unified standard for the research methods used to evaluate medical devices. In this study, we first designed a prospective randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of C3F8 in the experiment and control groups. The results of this study would provide strong evidence to support the adoption of experimental C3F8 as a safe and effective alternative for intraocular tamponade in clinical practice, which would offer clinical ophthalmologists more options and enhance accessibility for patients.

The experimental perfluoropropane for ophthalmic surgery, chemical structure - molecular formula: C3F8, is a colorless and transparent gas suitable for vitreous cavity filling. Both in vitro and in vivo experiments showed that the product was non-toxic (Report Nos G20200006, G20200007, G20200008, G20200009, G20200010, and G20200011). At present, the product has successfully passed the evaluation conducted by the Hangzhou Medical Device Quality Supervision and Inspection Center of the State Food and Drug Administration (Report No. G20200114), and the test result is qualified.

This study primarily aims to compare the safety and efficacy of experimental C3F8 with control C3F8 through a prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT), offering valuable insights for ophthalmologists regarding C3F8 selection.

-

A prospective, multicenter, randomized, single-blind, parallel-controlled clinical trial was conducted in six centers in China. All patients with RD were from Shanghai General Hospital, Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University, Shandong Eye Hospital, Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital, Tianjin Medical University Eye Hospital, and Tianjin Eye Hospital. The comparison type was a non-inferiority design. This clinical trial was designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of experimental C3F8 from Shanghai Jessi Medical Technology Co., Ltd (China) compared with control C3F8 from AL.CHI.MI.A.Srl (Italy, 20193160289). This trial was registered with the Shanghai Medical Products Administration (Record No.: 20210205).

Participants

-

Patients were enrolled in the study if they met the following key inclusion criteria: (1) aged between 18 and 75 years old (inclusive), irrespective of gender; (2) RRD requiring C3F8 assisted vitrectomy with intraocular gas tamponade; (3) proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) of grade A or B; (4) volunteer to participate in this clinical trial and sign the informed consent form of the subjects.

Exclusion criteria encompassed the following conditions were present: (1) bilateral retinopathy requiring simultaneous surgery (excluding laser surgery); (2) open ocular trauma with retinal detachment; (3) patients with a history of retinal detachment surgery; (4) severe glaucoma with obvious visual field defect and cup-to-disc ratio greater than 0.6; (5) patients with a history of severe uveitis; (6) patients with macular hole; (7) those who plan to travel at high altitude (including but not limited to air travel) within the past 3 months; (8) allergic to the product component (C3F8); (9) patients with silicone intraocular lens; (10) unable to maintain the treatment position after surgery due to mental or physical reasons; (11) pregnant, lactating or planning to get pregnant within 6 months; (12) patients with a history of epilepsy or severe mental illness; (13) those who participated in other interventional clinical trials within 1 month before this trial; (14) other persons considered by the investigator to be unsuitable for clinical trial participation.

It should be noted that patients were withdrawn from this trial when any of the following conditions occurred: (1) patients themselves withdrew from the clinical trial; (2) adverse events or serious adverse events (SAE) occurred, which prevented the patient from continuing to participate in the trial; (3) patients failed to follow-up according to the trial protocol due to poor compliance or loss of follow-up; (4) it is necessary for the investigator to stop the trial from a medical point of view.

Sample size

-

In this study, the sample size was calculated with the retinal reattachment rate as the main efficacy evaluation indicator. A survey of relevant literature[13,14] found that C3F8 has a good effect on clinical use. Therefore, this study assumed that the retinal reattachment rate PC of the control product was 96.5%, and the effective rate PT of the test product was expected to be equivalent to that of the control product. According to the non-inferiority sample size formula:

$ \mathrm{n}_{\mathrm{T}}=\mathrm{n}_{\mathrm{C}}=\dfrac{\left(\mathrm{Z}_{1-\alpha / 2}+\mathrm{Z}_{1-\beta}\right)^{2}\left[\mathrm{P}_{\mathrm{C}}\left(1-\mathrm{P}_{\mathrm{C}}\right)+\mathrm{P}_{\mathrm{T}}\left(1-\mathrm{P}_{\mathrm{T}}\right)\right]}{(\mathrm{IDI}-\Delta)^{2}} $ PT and PC were the expected event rates of the trial group and the control group, respectively. |D| is the absolute value of the expected rate difference between the two groups, |D| = |PT−PC|, and Δ is the noninferiority margin, which is taken to be −10%. The type I error α = 0.05 (two-sided), and the type II error β = 0.20. Fifty-four patients were enrolled in each group, and 108 patients were enrolled in the two groups. Considering the 20% dropout rate and the block length, there were 136 cases in the experimental group and the control group, and the number of subjects in the experimental group and the control group was 1:1.

Randomization and masking

-

Random number tables were generated using a stratified method by a third-party statistics company. All the patients were randomized before surgery on day 0. To avoid selection bias, the assigned numbers were sealed in opaque envelopes, ensuring that neither clinicians nor participants were aware of the treatment assignment. For enhanced patient safety and timely management of potential incidents, the study employed a single-blind design, masking treatment assignment from patients. Investigators dispensed two types of C3F8 during the trial, and any patients who became unmasked were withdrawn from the study.

Intervention

-

Demographic data collection, past medical history collection, vital signs collection, laboratory tests, and ocular examinations were performed during the screening period. Eligible patients (one study eye per patient) were randomized in a 1:1 ratio into the control group or the experimental group. All patients underwent surgery on day 0 and were followed up on days 1, 7, 14, 28, and 60 after surgery. During the surgery, investigators removed the vitreous body, closed RH with photocoagulation or cryotherapy, and infused C3F8 to fill the vitreous cavity. According to patients' conditions, lens extraction and intraocular lens implantation were completed at the same time in some patients.

Procedures

-

The primary outcome of this study was retinal reattachment rate 7 d after surgery. The secondary outcomes included retinal reattachment rates 1, 14, 28, and 60 d after surgery. We also observed the retention of C3F8, changes in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), and intraocular pressure (IOP) at 1, 7, 14, 28, and 60 d after surgery. Performance indicators were also evaluated during surgery by the operating investigator.

Retinal reattachment was assessed in a blinded manner by a senior ophthalmologist designated at each center who was not involved in the trial. Fundus examination was performed with a slit lamp preset lens, indirect ophthalmoscope, or three-mirror lens. According to the examination results, whether the hole was closed and the retina was completely reattached was evaluated. The proportion of C3F8 bubbles in the vitreous cavity, that is, the retention of C3F8. Evaluation criteria: (1) the optic disc could not be seen, and about 75% of gas was retained; (2) half of the optic disc was observed, and about 50% of the gas remained; (3) when the gas exceeded the upper boundary of the optic disc, about 30% gas remained; (4) the bubbles in the eye disappeared and the gas was absorbed. BCVA was measured with an international standard visual acuity chart and converted to LogMAR visual acuity. BCVA of the eyes in different follow-up periods after surgery was compared with that of the eyes in the screening period. At the same time, BCVA was compared between the two groups at each follow-up point. Intraocular pressure was measured by a non-contact tonometer. The performance indicators included (1) whether the sterile packaging was complete; (2) whether the contents of the device label and instructions were clear, complete, and easy to identify; (3) whether the gas was colorless and transparent; (4) whether the device was easy to operate and inject.

Safety assessments

-

Safety was assessed through the collection and summary of ocular and non-ocular AEs, SAEs, ocular assessments, deaths, laboratory results, and vital signs. At each study visit, nondirective questioning was used to elicit AE reports from patients. All AEs and SAEs, whether volunteered by the patient, discovered by study site personnel during questioning, or detected by examination, laboratory testing, or other means, were recorded in the patient record and case report forms.

Statistical analysis

-

Efficacy analyses were performed on the basis of the full analysis set (FAS) and the per-protocol set (PPS). All baseline demographic analyses will be performed on the basis of the FAS, and safety evaluations were performed on the safety analysis set (SS).

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant (unless otherwise specified). Description of quantitative indicators will calculate mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum values. The number of cases and percentage of each category were used to describe the classification indicators.

For general information and baseline characteristics, according to the numerical characteristics of the variables, t-test/corrected t-test was used to compare the quantitative data, such as age and blood pressure, between the two groups of subjects. The chi-square test/exact probability method was used to compare the qualitative variables, such as gender and past medical history, between the two groups. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the ordered categorical data between groups.

For efficacy and safety indicators, quantitative data were compared between groups using t-test/corrected t-test/Wilcoxon rank sum test. The chi-square test/exact probability method was used for qualitative data comparison between groups, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test or CMH chi-square test was used for ordinal classification data.

-

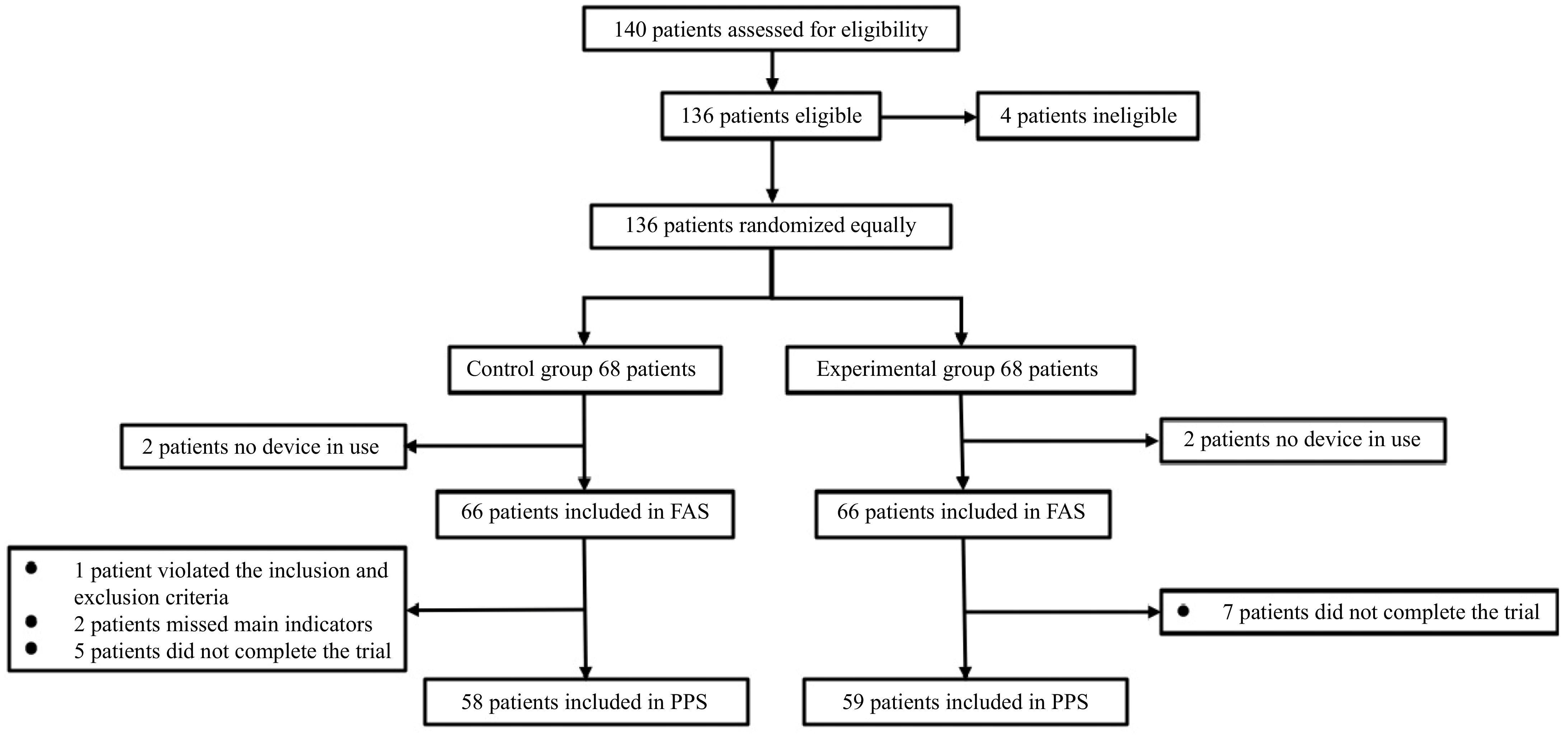

A total of 140 eligible participants were recruited from December 29, 2021, to March 02, 2023, and 136 were successfully enrolled. One hundred and thirty-six patients were randomly assigned equally to the experimental and control groups for surgical treatment. In this clinical trial, four patients did not use the study device, so 132 subjects were included in the FAS and SS analyses. Among the subjects who completed the study, two cases were missing the main indicators, and one case did not meet the inclusion criteria. Twelve subjects dropped out, so 117 cases were included in the PPS analysis (S2), accounting for 88.64% of FAS (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Table 1. Enrolled patients and safety and efficacy analysis population.

Observation item Experimental group Control group Actual enrollment 68 (100.00%) 68 (100.00%) Completing the trial 61 (89.71%) 59 (86.76%) Without the use of device 2 (2.94%) 2 (2.94%) Violation of criteria 1 (1.47%) 0 (0.00%) Efficacy analysis population FAS 66 (97.06%) 66 (97.06%) PPS 58 (85.29%) 59 (86.76%) Safety analysis population SS 66 (97.06%) 66 (97.06%) FAS: full analysis set, PPS: per-protocol set, SS: safety analysis set. Baseline

-

The patients in the control and experimental groups were generally well balanced to baseline demographics (Table 2) and the studied eye characteristics (Table 3), including the history of prior treatment (Supplementary Data S1).

Table 2. The demographic data at baseline (FAS).

Observation item Experimental group Control group Statistical approach Statistical magnitude p value Age (year) N (nmiss) 66 (0) 66 (0) T-test 0.289 0.773 Mean ± SD 54.71 ± 10.56 54.17 ± 11.15 Sex N (nmiss) 66 (0) 66 (0) Chi-square test 1.107 0.293 Male 40 (60.61%) 34 (51.52%) Female 26 (39.39%) 32 (48.48%) Table 3. The studied eye characteristics at baseline (FAS).

Observation item Experimental group Control group Statistical approach Statistical magnitude p value BCVA (LogMAR) N (nmiss) 66 (0) 64 (2) Wilcoxon −0.332 0.740 M (Q1, Q3) 0.52 (0.22,2.00) 0.82 (0.22, 2.00) IOP N (nmiss) 66 (0) 66 (0) T-test −0.418 0.677 Mean ± SD 12.74 ± 3.06 12.96 ± 3.11 Choroidal detachment N (nmiss) 66 (0) 66 (0) Exact probability method 1.00 No 65 (98.48%) 64 (96.97%) Yes 1 (1.52%) 2 (3.03%) BCVA: best corrected visual acuity, LogMAR: Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution, IOP: intraocular pressure. Retinal reattachment rate

-

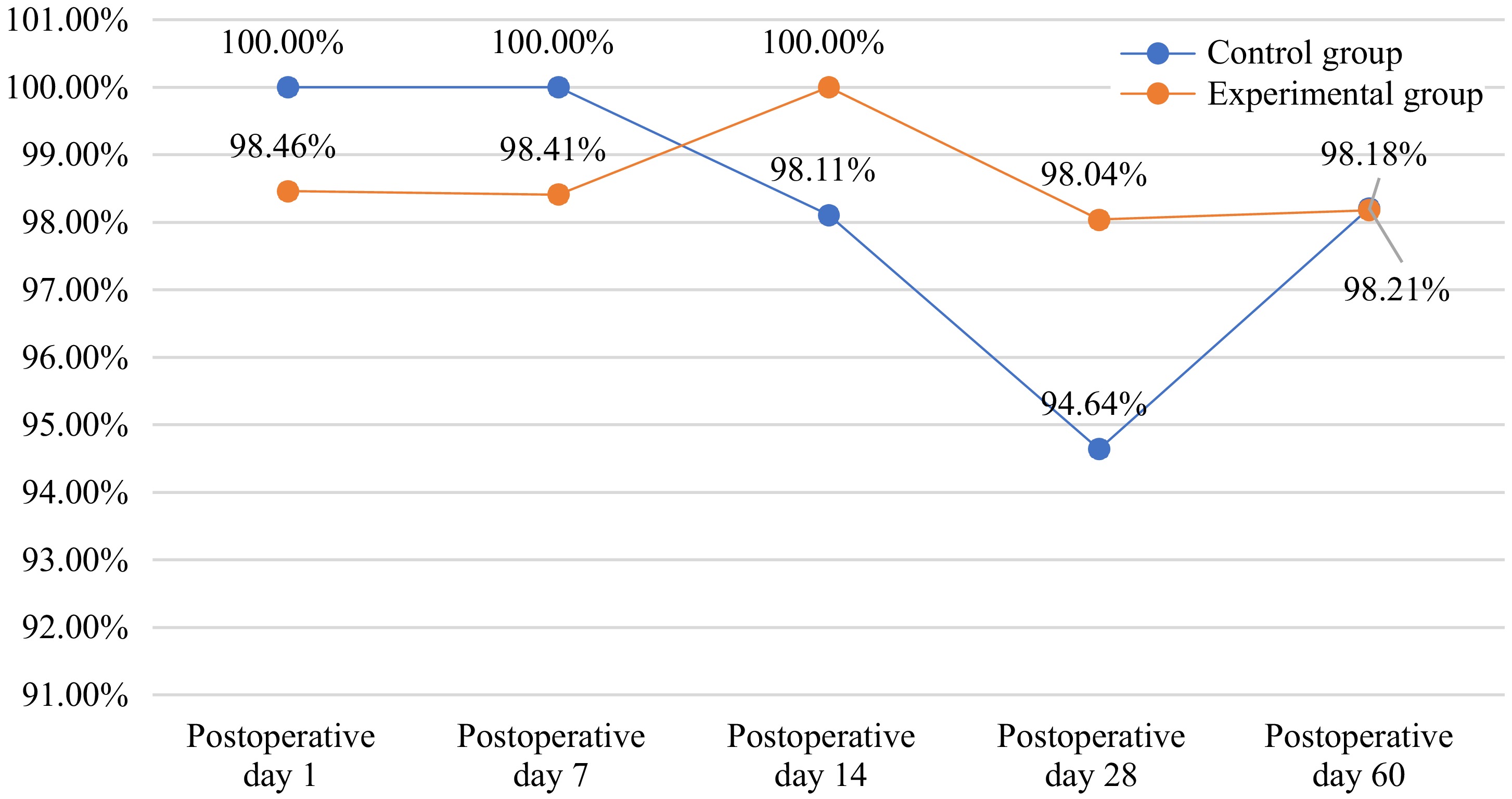

The complete retinal reattachment rate 7 d post-surgery was 100% in the control group and 98.41% in the experimental group (p > 0.05). The difference and 95% confidence interval of the retinal reattachment rate 7 d after surgery between the experimental group and the control group were −1.59% (−4.67%, 1.50%). At 1, 14, 28, and 60 d after surgery, retinal reattachment rates were 100%, 98.11%, 94.64%, and 98.21% in the control group, while retinal reattachment rates were 98.46%, 100%, 98.04%, and 98.18% in the experimental group (Fig. 2). There were no significant differences between the two groups (Table 4).

Table 4. The complete retinal reattachment rates after surgery (FAS).

Observation item Experimental group Control group Statistical approach p value 1 d after surgery N (nmiss) 65 (1) 65 (1) Exact probability method 1.000 Yes 64 (98.46%) 65 (100.00%) Not applicable 1 (1.54%) 0 (0.00%) 14 d after surgery N (nmiss) 54 (12) 53 (13) Exact probability method 0.495 No 0 (0.00%) 1 (1.89%) Yes 54 (100.00%) 52(98.11%) 28 d after surgery N (nmiss) 51 (15) 56 (10) Exact probability method 0.620 No 1 (1.96%) 3 (5.36%) Yes 50 (98.04%) 53 (94.64%) 60 d after surgery N (nmiss) 55 (11) 56 (10) Exact probability method 1.000 No 1 (1.82%) 1 (1.79%) Yes 54 (98.18%) 55 (98.21%) BCVA

-

There were no significant differences in postoperative BCVA between the two groups at each follow-up point. Compared with the preoperative BCVA, the BCVA of the two groups decreased at 1 d and 7 d post-surgery but improved at 28 d and 60 d post-surgery (Table 5).

Table 5. BCVA at 1, 7, 14, 28, and 60 d after surgery (FAS).

Observation item Experimental group Control group Statistical approach Statistical magnitude p value 1 d after surgery N (nmiss) 50 (16) 49 (17) Wilcoxon 1.436 0.151 M (Q1, Q3) 2.00 (2.00,2.00)*** 2.00 (2.00,2.00)*** 7 d after surgery N (nmiss) 59 (7) 64 (2) Wilcoxon −1.144 0.253 M (Q1, Q3) 2.00 (0.96,2.00)*** 2.00 (2.00,2.00)*** 14 d after surgery N (nmiss) 54 (12) 52 (14) Wilcoxon −0.507 0.612 M (Q1, Q3) 0.70 (0.30,2.00) 0.82 (0.41,2.00) 28 d after surgery N (nmiss) 52 (14) 55 (11) Wilcoxon 0.144 0.885 M (Q1, Q3) 0.40 (0.22,0.70)* 0.40 (0.17,0.70)*** 60 d after surgery N (nmiss) 60 (6) 56 (10) Wilcoxon −0.069 0.945 M (Q1, Q3) 0.30 (0.10,0.52)*** 0.30 (0.10,0.52)*** */***: Postoperative visual acuity was statistically different from preoperative visual acuity. * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001. IOP

-

After surgery, 19 patients in the control group and 17 patients in the experimental group had elevated IOP, and all of them were cured after treatment. There was no difference between the two groups (Supplementary Data S2).

Gas retention

-

The retention of gas in the vitreous cavity plays an important role in retinal support and intraocular pressure. During fundus examination, the gas was considered to be about 75% when the optic disc was not visible, about 50% when half of the optic disc could be seen, and about 30% when the bubble exceeded the upper boundary of the optic disc. The gas was completely absorbed when the bubbles disappeared. There was no significant difference in postoperative gas retention between the two groups (Supplementary Data S2).

Safety evaluations

-

The most common ocular AEs were surgery-related IOP elevation, corneal edema, and posterior subcapsular feathery opacification of the lens (Table 6). There were 39 (59.09%) AEs in the control group and 30 (45.45%) in the experimental group. Of these, nine (10.71%) were related to the study device in the control group and 9 (14.06%) in the experimental group (Table 7). Safety indicators, including vital signs, laboratory examinations, and occurrence of AEs and SAEs, had no significant differences between the two groups (Supplementary Data S3).

Table 6. Ocular adverse events.

IOP elevation Corneal edema Cataract Anterior chamber gas Experimental group 17 4 8 3 Control group 19 2 8 1 Table 7. Occurrence of adverse events (SS).

Observation item Experimental group Control group Statistical approach Statistical magnitude p value AEs N (nmiss) 66 (0) 66 (0) Chi-square test 2.460 0.117 No 36 (54.55%) 27 (40.91%) Yes 30 (45.45%) 39 (59.09%) Severity N (nmiss) 62 (0) 64 (0) Wilcoxon −0.537 0.591 Mild 46 (74.19%) 47 (73.44%) Moderate 15 (24.19%) 14 (21.88%) Severe 1 (1.61%) 3 (4.69%) Relationship to the device N (nmiss) 62 (0) 64 (0) Wilcoxon −0.537 0.591 Certainly relevant 9 (14.52%) 9 (14.06%) May be relevant 28 (45.16%) 23 (35.94%) May not be relevant 10 (16.13%) 18 (28.13%) Certainly not relevant 15 (24.19%) 14 (21.88%) Outcomes of AEs N (nmiss) 62 (0) 64 (0) Exact probability method 0.512 Persistence 10 (16.13%) 15 (23.44%) Deterioration 1 (1.61%) 1 (1.56%) Recovery/cure 49 (79.03%) 48 (75.00%) Recovered but had sequelae 2 (3.23%) 0 (0.00%) Withdrawal due to AEs N (nmiss) 66 (0) 66 (0) Exact probability method 0.440 Yes 5 (7.58%) 2 (3.03%) No 61 (92.42%) 64 (96.97%) AEs: adverse events. -

In this study, we found that the difference in retinal reattachment rate between the experimental group and the control group 7 d post-surgery was −1.59% (95% CI: −4.67%, 1.50%). No significant differences were observed in safety indicators, including vital signs, laboratory tests, and AEs between the two groups.

RRD is a serious condition that can result in significant ocular morbidity if not treated promptly. Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) has become the standard treatment for RRD[16]. Vitreous substitutes used in PPV must possess appropriate physical and biological properties that make them suitable for use in clinical applications[17−19]. These substitutes must remain stable when injected through a small syringe, as well as ensure adequate surface tension in the attempt to seal the retinal breaks. Additionally, they must be non-toxic to retinal tissues[20−22].

SiO, a commonly used intraocular tamponade, has been associated with complications such as transient or permanent retinal ischemia and thinning of inner retinal layers[23]. Additionally, patients who have used SiO are at higher risk of emulsification, elevated IOP, and lens opacification compared to patients using other tamponade agents[24,25]. Due to its non-absorbable nature, SiO necessitates secondary surgical intervention for removal following retinal reattachment. In contrast, inert gases as intraocular tamponades reduce both the incidence of postoperative complications and the need for additional surgeries. The use of intraocular gas was first described by Ohm in 1911[26]. It is effective in unfolding and stabilizing the retina, enhancing postoperative visualization, and replacing the globe volume to prevent fluid ingress into retinal breaks[27]. C3F8 is currently a commonly used intraocular substitute, with a duration ranging from 4 to 12 weeks (mean 7.2 weeks), where 31% of cases report 8 weeks and 27% report 6 weeks[13].

C3F8, used in ophthalmic surgery, is a colorless and transparent gas. To assess its safety and efficacy, we conducted a clinical trial involving 136 patients with RD across six centers. Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental or the control groups.

In terms of efficacy, there were no significant differences in retinal reattachment rate or changes in BCVA between the experimental and the control groups. Throughout the clinical trial, RD recurred in four patients in the experimental group and five patients in the control group, respectively. These recurrences were primarily attributed to the contraction and traction caused by extensive fibrous proliferative membranes on the retinal surface and behind the vitreous[28]. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) has been identified in the literature as the primary cause of failure in RRD surgery[29]. Compared with the preoperative BCVA, BCVA of the two groups decreased at 1 d and 7 d post-surgery. This is because a large amount of C3F8 was present in the vitreous cavity and blocked the macula at 1 d and 7 d post-surgery, which made the BCVA of the two groups decrease. With the gradual absorption of C3F8, the BCVA returned to the preoperative level at 14 d post-surgery and improved at 28 d and 60 d post-surgery compared with the preoperative BCVA. Previous studies have also reported that patients may experience poor visual outcomes following PPV, even after achieving retinal morphological reattachment[30].

In terms of safety, elevated IOP (> 21 mmHg) was observed in 17 patients in the experimental group and 19 patients in the control group. Postoperative IOP levels increased in both groups compared to preoperative measurements. In the control group, IOP reached its maximum on postoperative day 7, subsequently declining in both groups. By postoperative day 60, IOP in both groups have returned to levels close to the preoperative baseline. Elevated IOP is a common complication following PPV, associated with factors such as hypertension, glaucoma, postoperative medication, and other factors[31]. Glucocorticoids, commonly used after PPV to reduce ocular inflammation, can trigger signaling cascades that lead to increased IOP[32]. Additionally, the expansile properties of C3F8 can contribute to postoperative gas inflation, further elevating IOP. However, as the gas is gradually absorbed and glucocorticoid dosages are tapered, IOP decreases over time.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, all participants were recruited from plain regions, with no representation from the plateau or basin regions, necessitating further investigation of C3F8 in these geographic settings. Secondly, this study included only patients with RRD, and the efficacy of C3F8 has not been evaluated for other retinal diseases requiring surgical intervention and vitreous cavity tamponade. No systemic AEs or SAEs were observed in this study. The most common ocular AEs were related to surgical procedures, including evaluated IOP and corneal edema. Other ocular AEs, such as endophthalmitis, uveitis, and suprachoroidal hemorrhage, were not detected. Although no new AE was observed, the limited sample size may not have been sufficient to identify all gas-related AEs. Post-marketing studies are necessary to further monitor the safety profile of C3F8.

-

In summary, this clinical trial demonstrated that experimental C3F8 is as effective and safe as control C3F8 in ophthalmic surgery. These results provide strong evidence to support the adoption of experimental C3F8 as a viable, cost-effective alternative for intraocular tamponade in clinical practice.

-

The Ethics Committees of Shanghai General Hospital (Approval No. 2021-111), Fudan University Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Hospital (Approval No. 2021124-1), Shandong Province Eye Hospital (Approval No. 2021004), Tianjin Eye Hospital (Approval No. TJYYLCSYSCLL-2021-31), Tianjin Medical University Eye Hospital (Approval No. 202202), and Shanghai Tenth People's Hospital (Approval No. SHSY-IEC-4.1/21-223/01) approved this study. The research adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants or their legal representatives reviewed and signed written informed consent forms. This trial was also registered with the Shanghai Medical Products Administration (Record No.: 20210205).

National Science and Technology Major Project of China (2017ZX09304010), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82171071), Characteristic Shanghai leading talents training Program (02.06.01.21.06).

-

data analysis, draft manuscript preparation: Jiang Y, Shi X; clinical diagnosis and treatment: Jiang C, Jiang R, Gu R, Yuan G, Liu C, Han Q, Wang Y, Li X, Hu B, Wang F, Liu K, Xu X; project design and supervision: Liu K, Xu X. The authors jointly confirmed the authenticity of the data and jointly revised the final manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Yan Jiang, Xin Shi

- Supplementary Data S1 Screening period data.

- Supplementary Data S2 Efficacy evaluation.

- Supplementary Data S3 Safety evaluation.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang Y, Shi X, Jiang C, Jiang R, Gu R, et al. 2025. Prospective, multicenter, randomized, single-blind, parallel-controlled clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of perfluoropropane for ophthalmic surgery. Visual Neuroscience 42: e003 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0002

Prospective, multicenter, randomized, single-blind, parallel-controlled clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of perfluoropropane for ophthalmic surgery

- Received: 20 December 2024

- Revised: 25 January 2025

- Accepted: 06 February 2025

- Published online: 19 March 2025

Abstract: Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (RRD) is a common sight-threatening ophthalmic emergency requiring surgical intervention. This study aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy of experimental perfluoropropane (C3F8) for intraocular tamponade during vitreoretinal surgery. A prospective randomized controlled trial was designed to assess the efficacy and safety of the experimental C3F8. A total of 136 patients with RRD requiring C3F8-assisted treatment from six centers in China were randomized in a 1:1 ratio into the control group or the experimental group. The control group used C3F8 from AL.CHI.MI.A.Srl (Italy), whereas the experimental group utilized C3F8 from Shanghai Jessi Medical Technology Co., Ltd (China). Follow-up assessments were conducted at 1, 7, 14, 28, and 60 d postoperatively. The primary outcome was retinal reattachment rate at 7 d post-surgery. The secondary outcomes included retinal reattachment rates at 1, 14, 28, and 60 d post-surgery, changes in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), intraocular pressure (IOP), and gas retention. Safety assessments included systemic and ocular adverse events. Differential analysis of these indicators between the two groups were performed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the experimental C3F8. At 7 d post-surgery, the complete retinal reattachment rate was 100% in the control group and 98.41% in the experimental group (P > 0.05). No significant differences were observed between the two groups across all follow-up time points in secondary outcomes and safety indicators. In patients undergoing pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) for retinal detachment, experimental C3F8 demonstrates non-inferior to control C3F8 as an intraocular tamponade. Both variants are safe and well-tolerated.

-

Key words:

- Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment /

- C3F8 /

- Retinal reattachment rate /

- Safety /

- Efficacy