-

With the continuous improvement in living standards, ornamental plants, as the main objects of landscaping and house gardening, have attracted our attention, providing us with spiritual enjoyment. International trade and economic globalization have led to a gradual expansion in ornamental plant production and consumption[1], stimulating the ornamental plant industry to create new varieties to meet demand. Long ago, after accidentally unveiling the mystery of natural hybridization, humans began to simulate natural pollination, crossing plants with different phenotypes for one or several traits to obtain better varieties. Later, due to the development of modern science and technology, ‘transgene’ technology became a direct method used to modify the plant phenotype. Compared with traditional cross-breeding, transgenic technology greatly shortens the breeding duration, improves breeding efficiency, and can more precisely target certain traits in a breeding program[2].

Gene editing is a recent emerging biotechnology, and its advantage is that it is able to precisely edit one or more specific genes to control gene function, gene expression and epigenetic state. However, compared with crops, vegetables and fruits, research on and application of gene editing in ornamental plants is in its infancy. Nevertheless, we can learn gene editing strategies from other species, which opens up new possibilities for molecular breeding of ornamental plants.

-

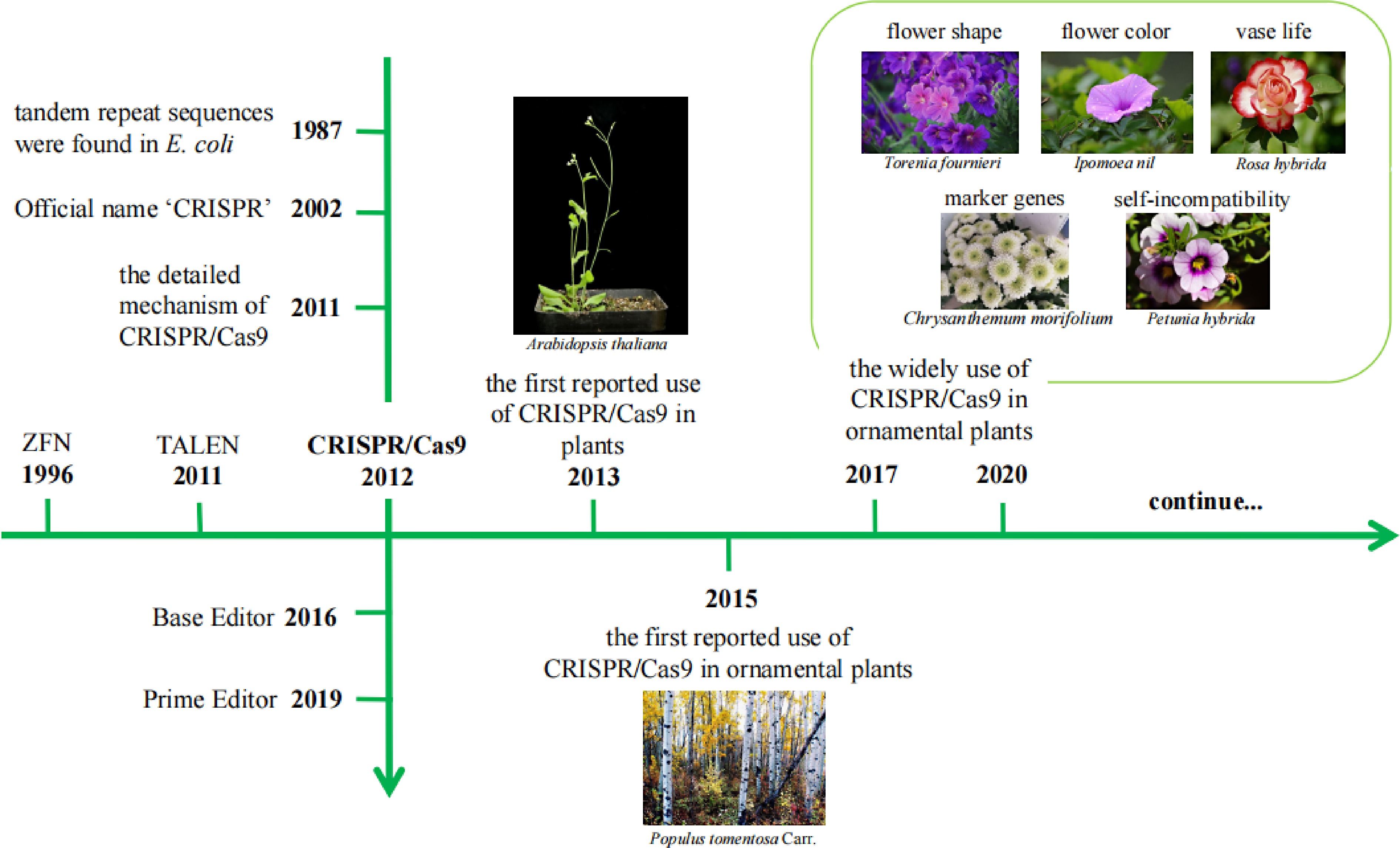

Gene editing technology has been developed for several generations, and includes zinc finger nuclease (ZFN)[3], transcriptional activator-like effector nuclease (TALEN)[4] and the CRISPR/Cas9 system[5]. Gene editing was first identified in 1996, ZFN was developed and designed to treat the human disease AIDS CCR5[6]. The first gene editing plant using ZFN was Arabidopsis thaliana in 2005[7]. In 2011, the second-generation gene editing technology TALEN appeared and was listed as one of the top ten scientific breakthroughs of the year by Science[8]. In the same year, TALEN was first applied to A. thaliana[9]. CRISPR/Cas9 emerged as a gene editing technique in 2012, but originated in 1987, when tandem repeat sequences were found in E. coli, and it was officially named CRISPR until 2002[10].

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is one of the most commonly used systems currently. The system was first discovered in bacteria and archaea as a means of immunity to resist foreign virus invasion[11]. Upon viral invasion, the Cas9-encoded protein scans the foreign virus and identifies the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) region and then uses the DNA sequence near the PAM as a candidate protospacer sequence. The Cas9 protein can subsequently cut off this sequence from the foreign DNA and insert the protospacer sequence downstream of the adjacent CRISPR sequence leader region with the assistance of other enzymes. The DNA is then repaired, closing the open gap. In this way, a new sequence of foreign spacers is inserted into the genome sequence[12].

In artificially designed gene editing experiments, double strand breaks (DSBs) generated by cutting after recognizing the PAM sequence can be repaired by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). NHEJ often leads to base insertion or deletion, thus resulting in an open reading frame (ORF) frameshift, which is commonly used for gene knockout. In contrast, HDR is an accurate repair mechanism that is commonly used to produce point mutations or fragment knock-ins[13]. In recent years, researchers have developed several emerging gene editing techniques based on CRISPR/Cas9, including Prime editor[14], Single base editor[15], Double base editing techniques[16] and Gene targeting[17], etc, which can create base conversion, insertion or deletion of short fragments efficiently and accurately without reliance on DSBs and donor DNA. The discovery of a Single base editor technology was in 2016, and another hot technology, Prime editor, appeared in 2019. Since gene editing technology was developed, the technical means have been constantly innovated and the application range has been gradually more extensive. CRISPR/Cas9 was first used in plants in 2013 in A. thaliana and Nicotiana benthamiana[18], while the first reported use of CRISPR/Cas9 in ornamental plants was in woody spices Populus tomentosa Carr. in 2015[19]. Then it began to be widely used in a variety of ornamental plants. (Fig. 1)

Before gene-editing technology was applied to ornamental plants, scientists used it for the improvement of crop traits, mainly focusing on plant resistance, quality and yield. For example, the ALS (acetyllactate synthase) gene was edited, and chlorsulfuron-resistant corn was obtained[20]. The targeted knockout of the OsBADH2 (betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase) gene using TALENs could increase the aroma of rice[21]. After mutating all three homoeologues of the rice TaGW2 gene by CRISPR/Cas9, a 16.3% increase in rice grain length and a 20.7% increase in grain weight were found[22]. Compared with crops, researchers also place different emphases on gene editing in ornamental plants due to their different characteristics and application directions.

-

Because ornamental plants usually have large genomic sizes and/or high heterozygosity, the application of gene editing in ornamental plants is less common than that in other crops. Reports to date have mainly focused on several important horticultural traits. Next, we summarize the recent research on gene editing in ornamental plants in terms of flower shape, flower color, vase life, marker genes and other traits (Table 1).

Table 1. List of current research of gene editing in ornamental plants.

Plant species Target trait Target gene Material Method Phenotype References Torenia fournieri Flower type RAD1 Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationA violet pigment pattern on dorsal petals [23] Phalaenopsis equestris Flower type MADS Explant Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationInfluence floral organ initiation and development [25] Torenia fournieri Color F3H Leaf Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationFaint blue (almost white) and pale violet flowers [26] Petunia Color F3H Protoplast PEG-mediated

transformationPale purplish pink flower [27] Petunia Color CCD4 Embryo-derived secondary embryo Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationPale yellow petals [28] Japanese Gentian Color GST1 Leaf Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationAlmost white or pale blue [29] Ipomoea nil Color DFR-B Embryo Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationGreen stems and white flowers [30] Ipomoea nil Vase life EPH1 Embryo Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationPetal senescence delay [31] Rosa hybrida Vase life EIN2 Somatic embryos Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationFlower opening completely blocked [32] Petunia hybrida Vase life ACO1 Protoplast PEG-mediated transformation Increased flower vase life [33] Chrysanthemum Marker gene YGFP Young leaf Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationGFP fluorescence [34] Lilium

Longiflorum & Lilium pumilumMarker gene PDS Embryogenic

calli and scalesAgrobacterium-mediated

transformationAlbino, pale yellow and albino green [35] Dendrobium officinale lignin synthesis C3H, C4H, 4CL,

CCR, IRXProtocorm Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationAffected the lignin biosynthesis [36] Petunia inflata reproduction SSK1 Leaves Agrobacterium-mediated

transformationInhibit the growth of pollen tubes [37] Flower shape

-

As one of the most important horticultural traits of ornamental plants, flower shape is an important breeding objective. Su et al. created loss-of-function TfRAD1 (RADIALIS1) lines of Torenia fournieri and observed a similar phenotype to TfCYC2 (CYCLOIDEA2)-RNAi lines, showing a violet pigment pattern on dorsal petals, but only the lateral petals became ventralized in shape[23]. The MADS gene family was reported to be associated with floral organ initiation and development[24]. The MADS gene of phalaenopsis (Phalaenopsis orchids) was edited and, except for individual lines, indel mutations were detected in all other lines, and 60% of them were nonchimeric triple MADS-null mutants[25].

Flower color

-

Color is the most studied trait of ornamental plants and an important trait to which people pay the most attention. Flower color can often give us the most intuitive visual experience, but some colors do not occur naturally, so many studies have aimed to create more colorful flowers. For example, the flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) encodes a key enzyme in the flavonoid synthesis pathway, and after using CRISPR/Cas9 to edit the T. fournieri F3H gene, mutant plants with different flower colors were obtained. Compared with the violet control, 62.5% of the colors changed to faint blue (almost white) and 12.5% to pale violet[26]. A gRNA that can simultaneously target two F3H genes (F3HA, F3HB) has also been designed in the petunia cultivar 'Madness Midnight', and after transforming into protoplasts through PEG, it produced 9.99% to 26.27% indel mutations. Only one double-knockout mutant in all 67 protoplast-regenerated plants showed marked flower color changes, changing from purple to pale purplish pink[27]. A gene associated with carotenoid degradation, carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 4 (CCD4), was knocked down using CRISPR/Cas9 and then transformed into the immature embryo-derived secondary embryo of the white-flowered cultivar Ipomoea nil cv. AK77, and as a result, the knockout mutant plants showed pale yellow petals and a 20-fold increase in carotenoid content compared with wild type[28]. Tasaki et al. performed gene editing of the Japanese gentian flower glutathione S-transferase 1 (GST1) gene and generated loss-of-function GST1 alleles; only 7.5% of the plants underwent editing at the target site and produced two mutants with different phenotypes, severe (almost white) and mild (pale blue)[29]. Dihydroflavonol-4-reductase-B (DFR-B) is a gene encoding the anthocyanin biosynthetic enzyme. After CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and transforming into the secondary embryos of Ipomoea nil, the mutation rate reached 75% after detection. Compared to the wild type with violet stems and flowers, biallelic mutants showed green stems and white flowers, and only a few monoallelic mutants showed green stems with violet flowers or violet stems with pale flowers[30].

Vase life

-

As the most important trait of fresh cut flowers, vase life greatly affects their quality and value, which has important research significance. EPHEMERAL1 (EPH1) is a gene that plays a key regulatory role in petal senescence. A target site mutation was detected in edited Japanese morning glory T0 lines, which is heritable, and T1 lines showed a significant delay in petal senescence[31]. The knockout of RhEIN2(ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE2) influenced the response of rose (Rosa hybrida) to ethylene, and the flower opening of the mutant was almost completely blocked[32]. After editing the 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase 1 (ACO1) gene using CRISPR/Cas9, the T0 mutant showed reduced ethylene production and increased flower vase life[33].

Marker genes

-

Marker genes are ideal candidate targets for constructing and optimizing gene editing systems. Transgenic fluorescent chrysanthemum flowers with multicopy genes and target fluorescent proteins were used as markers for visual assessment during gene editing, and mutant buds were obtained after the first successful application of the CRISPR/Cas9 system to chrysanthemum using the PcUbi promoter and fluorescent protein[34]. Two 20-nt target sequences were selected to knock out the phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene in the ORF region of LpPDS, and the vector was transformed into the embryogenic calli of Lilium pumilum and scales of Lilium longiflorum via Agrobacterium. The editing efficiency measured by PCR was 69.57% and 63.64% and produced 30% and 5.17% of the mutant plants with distinct phenotypes, respectively, and completely albino, pale yellow and albino–green chimeric phenotypes were observed[35].

Other traits

-

Kui et al. edited five genes involved in the lignin synthesis pathway using the CRISPR/Cas9 system, coumarin acid 3-hydroxylase (C3H), cassia bark acid 4-hydroxylase (C4H), 4-coumarin acid: coenzyme A ligase (4CL), cassia bark acyl coenzyme A reductase (CCR) and IRREGULAR XYLEM5 (IRX). After transforming to the original stem, base insertion, deletion and substitution was detected, affecting the lignin biosynthesis of Dendrobium officinale[36]. The piSSK1 gene of the Skp1 subunit in the Petunia SCF-SLF complex was edited using the CRISPR/Cas9 system and then transformed into leaves to research the effect of piSSK1 on self-incompatibility, and the loss of piSSK1 in transgenic pollen grains inhibited the growth of pollen tubes[37].

-

After constructing the gene editing vector, another important issue is how to express the editing system in plants. For ornamental plants, the genetic material delivery system of the species is not perfect due to the diversity of species and the high heterozygosity of the genome. Many kinds of ornamental plants lack a stable genetic transformation system, hampering further research[38]. At present, the three most commonly used genetic material delivery methods in ornamental plants are Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, protoplast transformation, and particle bombardment. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is one of the most commonly used methods, in which plant tissues are infected by Agrobacterium and then the Agrobacterium Ti plasmid integrates foreign DNA fragments into the plant genome. The advantages of this method are the high transformation efficiency and genetic stability, but most monocotyledons are insensitive to Agrobacterium, prohibiting the use of this method[39]. The protoplast transformation method requires preparing plant protoplasts, introducing exogenous DNA into the protoplast, and then regenerating the plants through protoplast culture technology. This technical process is relatively simple but requires the support of a perfect culture and regeneration system[40]. Particle bombardment technology requires the use of physical forces, such as gunpowder explosion, compressed gas or high-pressure discharge, to bombard plant tissue with external DNA through the medium microbomb and then transform it into recipient plants. This method has been widely applied but has high randomness and poor genetic stability[41]. Therefore, developing a more efficient delivery system for genetic material is an important direction that researchers need to explore next.

-

There are several difficulties hampering the use of gene editing in ornamental plants. First, the genetic material delivery system (genetic transformation system) of most ornamental plants is not yet mature and is inefficient, making it one of the main bottlenecks at present[42]. Second, the high heterozygosity of ornamental plant genomes also poses difficulties for the isolation of gene-edited vector fragments in the future. Third, a fragment may always have multiple copies in the genome, and multiple copies are often not completely consistent, so it is not easy to edit the ideal DNA fragment. Because of the prevalence of gene redundancy, even if multiple genes are edited, the expected phenotype may not appear.

In view of the above problems, we propose that the following strategies developing from other crops could be modified and applied in ornamental plants.

Improving editing efficiency

-

There is a report that the editing efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 in grapes increased proportionally with increasing sgRNA GC content, with the highest editing efficiency observed when the GC content was 65%[43]. Another method to optimize the original CRISPR/Cas9 system is to change the promoter. The endogenous U6 promoter was used to drive the expression of gRNA in Sorghum bicolor (sorghum), the vector was delivered into the callus through bombing, and create homozygous/biallelic editing sorghum, with an editing efficiency of more than 90%, which could be extended to other cereal crops[44]. The UBA (ubiquitin-associated domain) was used to enhance the stability of the Cas9 protein, and fusion of the UBA domain did not affect the cleavage mode of the Cas9 protein and effectively improved the editing efficiency of STU-SpCas9 at the target site[45]. In ornamental plants, we can also use the above methods to improve the editing efficiency of the CRISPR/Cas9 system by modifying and optimizing the gRNA or Cas9 protein.

Editing the gene regulatory region

-

X13 is a resistance gene that can regulate rice bacterial blight, because gene editing of the coding area will affect other important agronomic traits and fertility. Li et al. designed a 149-bp deletion in the promoter region, which included a 31-bp pathogen induction element. After editing, the rice mutant had improved bacterial blight resistance but fertility was not affected[46]. Gene editing technology accurately targeted multiple yield and quality trait control gene coding regions and regulatory regions of Solanum pimpinellifolium, promoted yield and quality traits accurately without sacrificing natural resistance to salinity and scab disease, and accelerated the artificial domestication of wild plants[47]. At present, editing by the CRISPR/Cas9 system mainly focuses on gene coding regions, and there are few studies on noncoding regions such as promoter regions, UTRs (untranslated regions), and/or introns. However, as mentioned above, because some genetic changes can greatly affect other important agronomic traits, research on noncoding region editing is also necessary.

Creating more chromosomal variation

-

Because spontaneous repair of DSBs leads to different types of chromosome rearrangement in nature, Schwartz et al. delivered a preassembled Cas9/gRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex into the immature embryo cells of maize through particle bombardment. Then, a 75.5-Mb center inversion occurred on chromosome 2 of the maize inbred line mediated by CRISPR/Cas9, which provided a new opportunity for maize breeding[48]. A target site of Staphylococcus aureus SaCas9 nuclease was designed at 0.5 Mb from the end of the long arm of Arabidopsis Chr1 and Chr2, two DSBs were artificially induced, and then the genetic material was delivered by Agrobacterium-mediated floral dipping. The ectopic frequency between the two cuts was 0.01%, providing the possibility of artificially creating chromosomal variation[49]. Due to the large genome size, polyploidy and high heterozygosity of most ornamental plants, if chromosomal variation can be created, it may be easier to bring more trait diversity to ornamental plants.

Creating the function gain mutant

-

GRAIN SIZE ON CHROMOSOME 2 (GS2) and encoding growth-regulating factor 4 (OsGRF4) positively regulate rice grain size, and the posttranscriptional regulation of miR396 can inhibit the function of GS2. In this regard, a CRISPR/Cas9 construct targeting the miR396 binding site of GS2 was designed and introduced into cultivated rice X12. Editing lines deleting three base pair deletions were identified and selected, allowing preserved GRF4 protein translation but inhibiting miR396 function at the mRNA level. This led to increased grain size and yield in the edited mutant[50]. In the application of gene editing in ornamental plants, we often use gene knockout but rarely create functional gain mutants, which is another strategy that should be researched.

-

At present, gene editing in ornamental plants is still in its infancy, but the good news is that an increasing number of researchers are engaged in the research and application of gene editing[51]. Although there are many limitations of gene editing for ornamental plants, we believe that many obstacles will be resolved with the advancement of gene editing theory and technology.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32172609, 32230098), College Students' Innovative Entrepreneurial Training Plan Program (202214YX890) and a project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institution.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2023 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Tang J, Ye J, Liu P, Wang S, Chen F, et al. 2023. Ornamental plant gene editing: Past, present and future. Ornamental Plant Research 3:6 doi: 10.48130/OPR-2023-0006

Ornamental plant gene editing: Past, present and future

- Received: 04 January 2023

- Accepted: 09 February 2023

- Published online: 15 March 2023

Abstract: With the rapid development of biotechnology, gene editing has become more widely used as a powerful tool to regulate plant traits directionally and efficiently. Here, we summarize the recent research progress in ornamental plant gene editing, including flower type, flower color, vase life, marker genes and other traits. We also discuss the application potential of other crop gene editing methods in ornamental plants and explore the diversity and feasibility of gene editing techniques in plant breeding to promote the molecular breeding of ornamental plants.

-

Key words:

- Gene editing /

- Ornamental plants /

- Research progress /

- CRISPR/Cas9