-

Blueberries are perennial and berry-producing shrubs that belong to the Ericaceae family and the Vaccinium genus. Cultivated blueberries can be broadly classified into three main categories: highbush blueberries, lowbush blueberries, and rabbiteye blueberries. The most widely grown blueberry is tetraploid highbush (Vaccinium corymbosum), which are subdivided into three categories based on their chilling requirements: southern highbush, northern highbush, and half-highbush[1,2]. Blueberries are native to North America[3] and were introduced to China in the 1980s, where they are now widely cultivated. In addition to their palatability, blueberries are rich in flavonoid compounds, which can enhance immune function, reduce the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, improve memory, delay ageing, and enhance vision, among other health benefits[4].

Blueberries have three ploidy types, comprising diploids, tetraploids, and hexaploids[5]. Polyploid plants, which possess multiple chromosome sets, have the potential to exhibit more favorable genetic variants than their wild diploid relatives[6]. Plants with duplicated whole sets of chromosomes, although not always, often display distinctive characteristics, including modifications to their plant form, flower size and style, fragrance, vase life, and flowering period[7]. Blueberry polyploids can be produced during hybridization due to the formation of unreduced gametes[8]. Another approach for inducing polyploidy is the artificial chromosome doubling of somatic cells. This method has been successfully applied to chromosome doubling in diploid blueberries[9−12]. However, the impact of chromosome duplication on the growth and development of blueberry has yet to be investigated.

Artificial chromosome doubling is generally carried out by anti-mitotic chemicals, of which colchicine is the most effective and widely used mutagenic reagent. Colchicine has been used to induce chromosome doubling in diploid blueberry varieties, including V. stamineum[9], V. darrowii[10], and V. bracteatum[11]. Using the in vitro leaves of highbush blueberry (V. corymbosum), colchicine treatment had shown polyploid induction effects[13]. However, it has been proven that colchicine has a low affinity for plant microtubules and must therefore be used at relatively high concentrations[14,15]. As colchicine is toxic to humans and has a high affinity for vertebrate microtubules[16], scholars have begun to explore alternative reagents that can be used for plant chromosome doubling.

A class of microtubule depolymerizing herbicides, including oryzalin, trifluralin, amiprophosmethyl, and pronamide, were similar to colchicine in terms of their effect on chromosome doubling, but at concentrations approximately 100 times lower[17]. In blueberry, both oryzalin[18], and trifluralin[12] were proven to be efficiency agents for inducing chromosome doubling. Moreover, oryzalin exhibited a higher degree of efficiency than colchicine in inducing chromosome doubling in four blueberry species (V. corymbosum, V. smallii, V. vitis-idaea, and V. uliginosum)[18,19]. Oryzalin was found to be more toxic than colchicine to shoot regeneration from leaf explants of highbush blueberry[13]. As an anti-mitotic agent, trifluralin has been applied to the chromosome doubling of various horticultural plants such as wheat[20], Brassica napus[21], and cucumber[22], demonstrating favorable induction effects and practical applications. In comparison to colchicine, the effect of trifluralin on chromosome doubling in highbush blueberry remains to be elucidated.

The types and growth status of the recipient material is an important factor influencing chromosome doubling in plants. Seeds[9,11], in vitro stems[12,18], leaves[13], and callus[19] of blueberries can be used for chromosome doubling. Zheng found that leaf callus was a better recipient material than apical leaves or seeds[19]. The occurrence of chimeras is one of the obstacles to artificial chromosome doubling[23]. Through tissue culture techniques, chimerism can be avoided and it is easy to isolate monoploidy plants from mixoploidy chimeras[24].

This study employed trifluralin and colchicine to treat pluripotent calli that were induced from blueberry leaves on the shoot regeneration medium. Chromosome-doubled plants were screened from the regenerated shoots. The effects of trifluralin and colchicine on blueberry chromosome doubling were compared, and the phenotypic studies on chromosome-doubled blueberries were conducted. This approach aimed to establish an efficient and stable chromosome doubling method for application in blueberry polyploid breeding.

-

Aseptic tissue-cultured plants of the southern highbush blueberry cultivar 'Diana' were obtained through the in vitro culture of stem segments. The stems were trimmed to a length of approximately 2 cm before subculturing onto WPM (woody plant medium), which had been supplemented with 1.0 mg/L zeatin, 0.05 mg/L NAA (1-naphthaleneacetic acid), 0.5 mg/L calcium nitrate, 3.25 mg/L agar, 1.4 mg/L gelrite, and 20 g/L sucrose. The pH was adjusted to 5.0−5.2. The culture conditions were maintained at 25 °C, with a light intensity of 2,000 Lux and a photoperiod of 16 h/8 h. Subculturing was performed every two months.

Induction of pluripotent calli and shoots regeneration

-

The leaves were excised from the stems, which were sub-cultured on the new medium for a period of 15 d. Subsequently, one-third of the apical portion of the leaves was cut off, and the remaining leaves were employed as explants for induction of pluripotent calli and adventitious shoot regeneration. The leaf explants were inoculated abaxially in the regeneration medium, which consisted of WPM medium with CaCl2 removed, supplemented 1.0 mg/L calcium nitrate, 0.3 mg/L calcium gluconate, 4.0 mg/L zeatin, 0.05 mg/L NAA (1-Naphthaleneacetic acid), 3.25 mg/L agar, 1.4 mg/L gelrite, and 20 g/L sucrose. The pH of the culture medium was adjusted to 5.0−5.2. The medium was sterilized and then poured into Petri dishes (Ø 9 cm). Each dish was inoculated with 12 explants and placed in the dark at 25 °C for 15 d. Thereafter, the culture was transferred to light conditions with a light intensity of 2,000 Lux and a photoperiod of 16 h/8 h at 25 °C.

Trifluralin and colchicine treatment

-

The stock solution of trifluralin (Phytotech, USA) was prepared at a concentration of 5 g/L with DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) as the solvent. Following filtration through a 0.22 μm Millipore filter, the stock solution was stored at −20 °C for subsequent utilization. Once the temperature of the medium had fallen below 60 °C following autoclaving, an appropriate quantity of the trifluralin stock solution was added, with the final concentration set at five gradients (Table 1). Similarly, the stock solution of colchicine (Phytotech) was prepared with ddH2O as the solvent. The final concentration of colchicine was set at five gradients (Table 1).

Table 1. The effects of trifluralin and colchicine on shoot regeneration from leaves of blueberry.

Treatment agents concentration

(mg/L)No. of explants Survival rate

of explants %No. of shoots per explant No. of polyploid CK 0 36 100a 6.92 ± 0.804a 0 Trifluralin 0.5 36 100a 4.28 ± 0.746b 0 1.0 36 100a 2.97 ± 0.255c 0 2.0 36 86.11 ± 4.815b 1.89 ± 0.348d 6 5.0 36 77.78 ± 4.809c 0.61 ± 0.314e 6 10.0 36 55.56 ± 4.809d 0.25 ± 0.080e 3 Colchicine 10 36 100a 5.58 ± 0.217b 0 20 36 100a 3.94 ± 0.648c 0 50 36 88.89 ± 4.815b 3.44 ± 1.210c 0 100 36 75 ± 8.33c 1.11 ± 0.172d 0 200 36 52.78 ± 4.809d 0.42 ± 0.085d 3 Different lowercase letters indicate statistical significance (Duncan's new multiple range test, p < 0.05). The leaf explants were initially cultivated in the dark at 25 °C for 15 d. Subsequently, the explants were transferred to regeneration medium containing varying concentrations of trifluralin or colchicine, and treated for 2 d. They were then transferred back to the regeneration medium and subsequently cultured under light conditions with a light intensity of 2,000 Lux and a photoperiod of 16 h/8 h at 25 °C for 30 d. The survival rate of explants and the number of regenerated adventitious shoots per dish were counted.

Ploidy identification

-

Flow cytometry was used to identify the chromosome ploidy of the regenerated adventitious shoots following the methodology proposed by Ochatt[25], with some modifications. Approximately 0.2 g of tender leaves from the shoots were placed in a culture dish, followed by the addition of 500 mL of lysis solution. The leaves were rapidly chopped with a sharp blade to extract the complete cell nuclei. The mixture was filtered through a 50 μm micropore membrane into a centrifuge tube, and centrifuged at 5,000 rpm and 4 °C for 5 min, after which the supernatant was discarded. Two millilitres of DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) fluorescent dye were added to the final mixture for staining in the dark for 2 min. The ploidy of the chromosomes was then determined using the CyFlow Space flow cytometer (Sysmex Partec, Münster, Germany).

Biological characteristics of chromosome-doubled plants

-

The chromosome-doubled adventitious shoots were transferred to a rooting medium comprising WPM, supplemented with 0.5 mg/L IBA (indole butyric acid), 0.2 mg/L NAA, 3.25 mg/L agar, 1.4 mg/L gelrite, 20 g/L sucrose, and 0.2 g/L activated carbon. The pH was adjusted to 5.0−5.2. The culture conditions were 2,000 Lux light intensity and 16 h/8 h photoperiod at 25 °C. After a month of cultivation, the well-rooted seedlings were transferred to the greenhouse for acclimatization. The plants were cultivated in containers using substrate and integrated water and fertilizer management. The leaf stomatal structure was observed under a light microscope. Ten individual plants were selected from biennial tetraploid and octaploid blueberries respectively for the study of their morphological characteristics. The plant height, number of canes, blade length and width were measured. Additionally, a total of 20 fruits from tetraploids and octaploids respectively were used in the study of fruit phenotype. The weight and diameter of ripe fruits were measured.

Statistical methods

-

The data were subjected to statistical analysis using DPS (version 9.01)[26]. Differences among three or more experimental groups were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan's new multiple range test with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. Differences between two experimental groups (tetraploids and octaploids) were analyzed by an unpaired Student's t-test with a significance level of p ≤ 0.05.

-

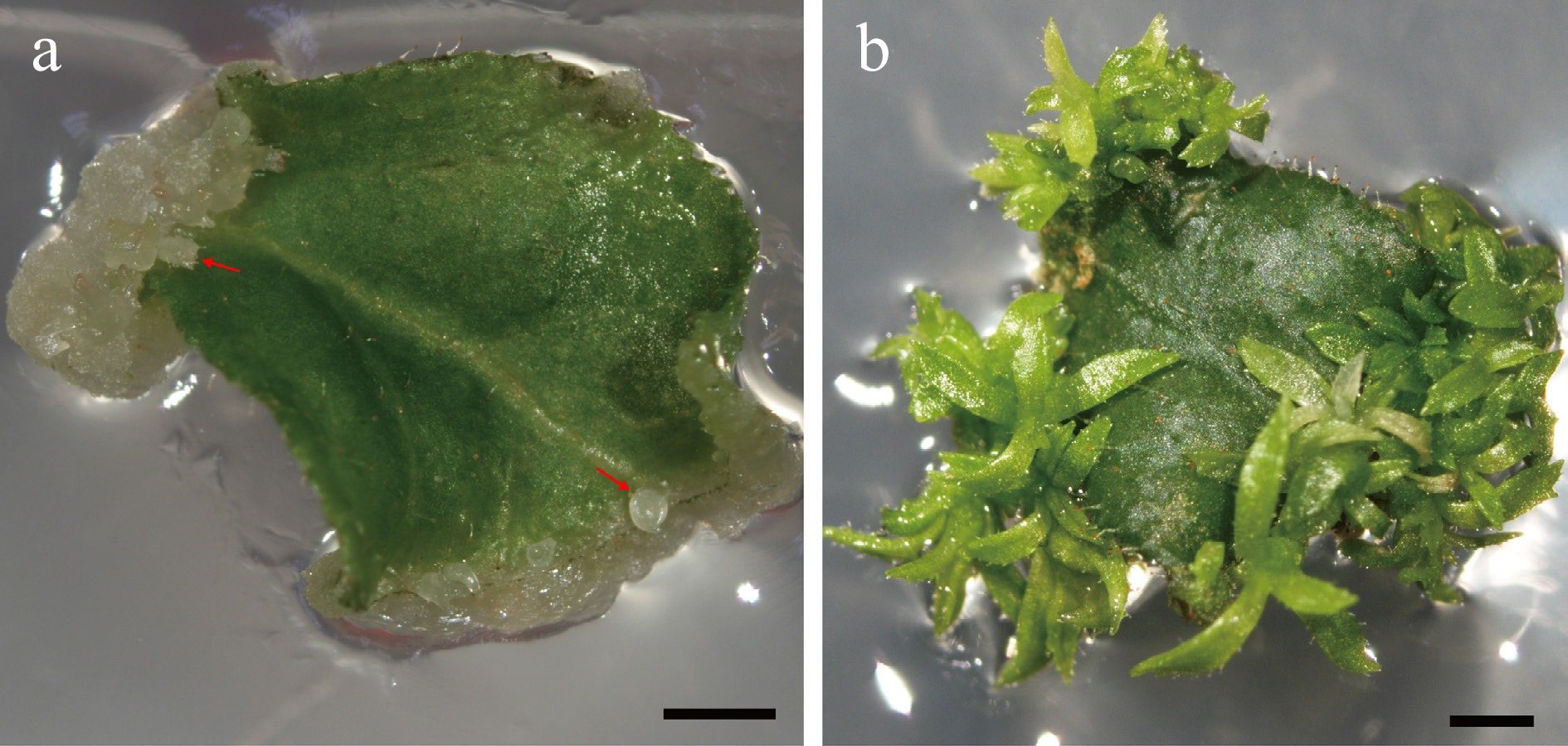

Pluripotent calli were induced from the edge of leaf explants cultured in the dark for 15 d. The shoot primordia and embryoid structures could be observed on the surface of the callus (Fig. 1a). Following the treatment of pluripotent calli with trifluralin or colchicine for 2 d, the specimens were subsequently transferred to a lighted environment for a further 30 d, after which the number of regenerated adventitious shoots (Fig.1b) was counted. The results (Table 1) indicated that as the concentration of trifluralin increased, the number of adventitious shoots gradually decreased. When the concentration of trifluralin exceeded 2.0 mg/L, a part of explants showed browning and death. When the concentration exceeded 10.0 mg/L, it was difficult to induce the adventitious shoots to regenerate. Similar results were obtained by colchicine treatment, with the number of adventitious shoots gradually decreasing as the concentration of colchicine increased. When the concentration of colchicine exceeded 50 mg/L, explants showed browning and apoptosis. Almost no adventitious shoots occurred under the concentration of colchicine exceeded 200 mg/L.

Figure 1.

Pluripotent calli and shoots regenerated from leaf explants of Vaccinium corymbosum 'Diana'. (a) Leaf explants were cultured on regeneration medium for 15 d under dark conditions, and the pluripotent calli were induced from the edge of explants. Arrows indicate the shoot primordia and embryoid structures. (b) Adventitious shoots were regenerated from leaves after transferring to light conditions for 30 d. Scale bar = 1 mm.

Identification and acquisition of polyploid plants

-

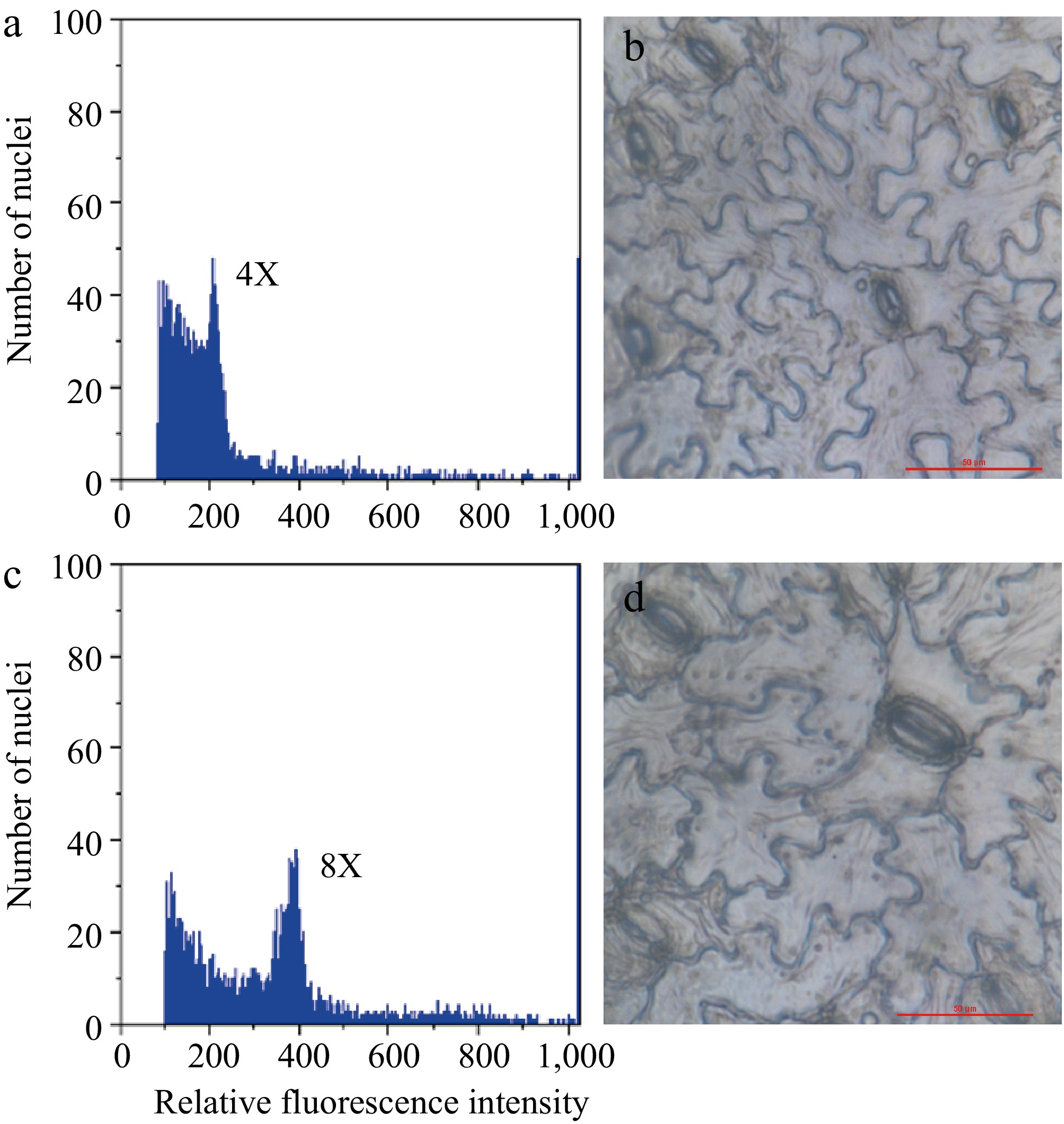

Following treatment with trifluralin or colchicine, a minor proportion of adventitious shoots exhibited notable morphological variations, and chromosome doubling may occur in these shoots. In comparison to the original plant, the putative chromosome-doubled shoots exhibited the following characteristics: shortened internodes, thickened stems and leaves. Flow cytometry was employed to ascertain the ploidy levels of the plants, and it was determined that the fluorescence peak value of 18 plants exhibiting notable morphological variations was twice that of the control, thereby confirming them as chromosome-doubled plants (Fig. 2a, c). Furthermore, the results demonstrated that all chromosome-doubled plants exhibited a single peak in their fluorescence profile, indicating that they were homozygous polyploid plants devoid of any chimeric elements. Given that the original plants were tetraploid (2n = 4x = 48), it can be concluded that the chromosome-doubled plants were all octoploid (2n = 8x = 96).

Figure 2.

Detection of chromosome ploidy by flow cytometry and microscopic observation of leaf stomata. Relative fluorescence intensity of plant chromosome nuclei of chromosome-doubled plant (c) and its progenitor (a). The size and density distribution of leaf stomata derived from tetraploid (b), and octoploid (d) was observed under a microscope (40×). Scale bar = 50 μm.

The generation of chromosome-doubled plants was observed when the concentration of trifluralin was within the range of 2−10 mg/L. However, when the concentration of trifluralin exceeded 10 mg/L, there was a marked reduction in the regeneration of adventitious shoots. The application of colchicine at a concentration of 200 mg/L was observed to induce chromosome doubling, although the rate of adventitious shoot regeneration was found to be markedly reduced (Table 1). The results revealed that trifluralin induced chromosome doubling in blueberries at 100-fold lower concentrations than colchicine. It can therefore be concluded that trifluralin is a more effective agent than colchicine for inducing chromosome doubling in blueberries under in vitro conditions.

Shoots rooting and leaf stomata observation of octoploid plants

-

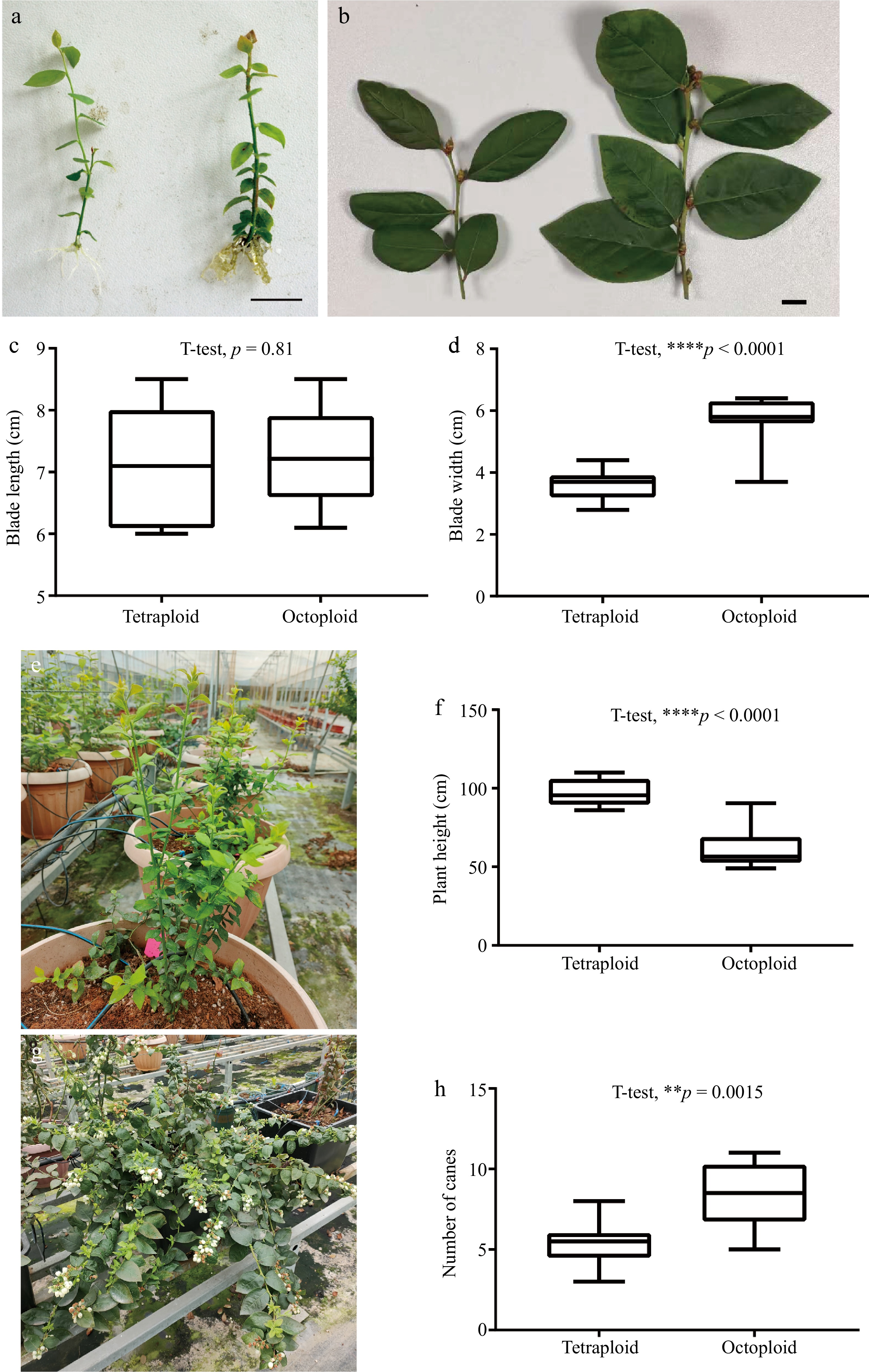

Roots were induced from octoploid shoots after one month of culture on rooting medium. In comparison to their tetraploid progenitor, the octoploid plants exhibited greater difficulty in undergoing root formation. The rooting rate of the octoploid plants was approximately 30%, while the rooting rate of the tetraploid plants was greater than 80% when they were cultured on the same rooting medium. The stems of the octoploid plants were observed to be thicker (Fig. 3a). Microscopic observation indicated that compared to the control, the leaf stomata size of octoploid plants was significantly larger, and the stomatal density distribution was reduced (Fig. 2b, d).

Figure 3.

Growth characteristics of chromosome-doubled blueberries. (a) Tissue culture seedlings of tetraploid (left) and octaploid (right) blueberries. (b) Comparison of leaf and flower buds between tetraploid (left) and octaploid (right) plants. (c) Blade length of tetraploid and octaploid plants was analyzed using Student's t-test. (d) Blade width. (e) Growth of annual octaploid plants. (f) Plant height. (g) Flowering status of biennial octaploid plants. (h) Number of canes. Scale bar = 1 cm. Asterisks indicate significant difference.

Phenotypic investigation of octoploid plants in greenhouses

-

Well-rooted seedlings were transplanted to a greenhouse for acclimatization and then cultivated in containers with substrate cultivation and integrated water and fertilizer management. It was observed that the vegetative and reproductive growth of the octoploid plants exhibited significant differences from that of the control. The octoploid blueberries displayed a more open plant structure with a notable increase in the number of canes, the shoots that emerge from the base of the plant (Fig. 3h). The larger leaf size was also observed in the octoploid plants (Fig. 3b), and the octoploid showed a substantially wider blade width (Fig. 3d). Nevertheless, octoploid plants exhibited a relatively slow growth rate, resulting in the development of dwarf plants (Fig. 3e, f). Following the transition into the reproductive growth phase, the biennial plants exhibited a substantial number of flower buds (Fig. 3g). The octoploid plants demonstrated a blooming period that was approximately one month earlier than the control. But it is noteworthy that the artificial octoploid blueberries exhibited a lower fruit set.

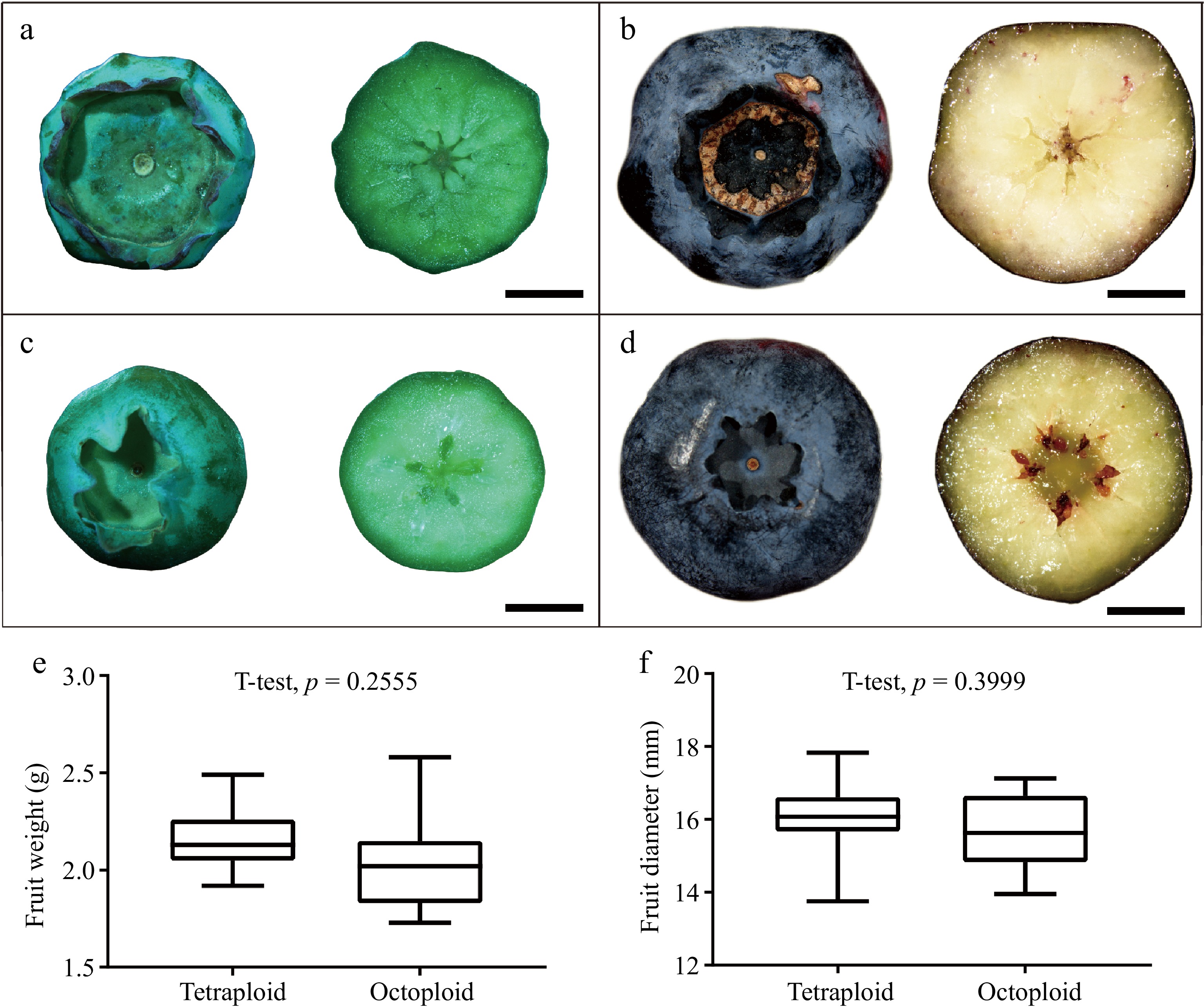

An observation of the fruit morphology revealed that the fruit ridges of the octoploid blueberries were prominently protruding, the calyx diameter was enlarged, and the number of sepals increased to six or eight. Cross-sectional observations indicated that the majority of octoploid fruits exhibited six to eight locules, which was consistent with the number of sepals. In contrast, tetraploid blueberry fruits typically displayed five sepals and five locules. Notably, fully developed seeds were not observed in the fruits of the chromosome-doubled plants, with only residual black marks remaining after seed abortion (Fig. 4). The weight and diameter of ripe fruits showed no significant difference between the tetraploid and octaploid plants (Fig. 4e, f).

Figure 4.

Comparison of fruit morphology between octaploid and tetraploid blueberries. Comparing the morphology and cross-sectional structures of (a), (b) octaploid fruits to the (c), (d) original tetraploid fruits, including (a), (c) green young fruits, and (b), (d) blue ripe fruits respectively. The (e) ripe fruit weight and (f) diameter in tetraploid and octaploid were analyzed using Student's t-test. Scale bar = 0.5 cm.

-

This study established a technology for efficiently and stably inducing chromosome-doubled blueberries using trifluralin, which is a herbicide with the advantages of low toxicity[12], and safety for human health[27]. Our study proved that the effect of trifluralin in inducing blueberry chromosome doubling is better than colchicine, and the concentration used is lower. The findings of this study will facilitate the advancement of ploidy breeding in blueberries. The trifluralin was also proved to be an efficient agent in chromosome doubling of diploid blueberry[12]. Studies on Anthurium andraeanum[28] showed that the induction efficiency of trifluralin is higher than that of oryzalin and colchicine. The study of pumpkin[29] also showed that trifluralin had low concentration, low toxicity, low price, and good effect on chromosome doubling. Therefore, trifluralin has great potential and application prospects in the chromosome doubling of horticultural plants.

The selection of the recipient material represents a pivotal element influencing chromosome doubling. Both stems and seeds can be employed as explants for chromosome-doubling induction in blueberry. The axillary meristems of stems are characterized by vigorous cell division and a robust regeneration capacity[30], rendering it a mostly selected recipient material for the induction of chromosome doubling. However, since plant regeneration originates from multiple cells of the axillary meristem, chimera formation may frequently occur when stems are used for recipient material. Previous studies have employed colchicine in the treatment of blueberry in vitro shoot stems, yet some of the resulting plants exhibited chimerism[18,31,32]. Furthermore, blueberry seeds treated with colchicine are also susceptible to the formation of chimeric plants[10]. In our study, the use of pluripotent calli as recipient material resulted in the direct development of a single chromosome-doubled cell into a complete plant, thereby inducing monoploid plants without the occurrence of any chimeras. Zheng also indicated that leaf callus is superior to apical leaves and dormant seeds in inducing chromosome-doubled Vaccinium uliginosum L[19]. A recent study[13] used the in vitro leaves as recipient material, but mixoploids plants also occurred. The protocol by Marangelli et al.[13] involved treating the leaves directly with colchicine, whereas our research treated the pluripotent calli induced from leaf explants. Consequently, pluripotent calli were regarded as the optimal receptor material for chromosome doubling induction in highbush blueberry, with the potential to mitigate the likelihood of chimerism.

Using our method of blueberry chromosome doubling, octoploid plants were obtained and developed. Significant distinct traits were revealed between tetraploid and artificial octoploid blueberries. Octoploid plants showed some excellent phenotypes such as thickener stems and larger leaves, more canes, and earlier flowering phase. These aforementioned genetic traits are of utility in the context of blueberry hybrid breeding. However, octoploid shoots showed difficulty in rooting, leading to dwarf plants. A previous study revealed that colchicine-induced tetraploid apple exhibited a dwarf phenotype due to a significant decrease in indole acetic acid and brassinosteroid hormone levels in tetraploid plants[33]. Recent research has found that with the increase of chromosome ploidy levels in Arabidopsis, the content of plant cell walls is reduced, along with the plant structure becoming unstable, which will lead to an adverse effect on plant growth and development[34]. It can be reasonably deduced that genome duplication in tetraploid blueberries will impede plant growth and development. However, further research is required to explore the underlying causes of the observed dwarfism in octoploid blueberries.

The reproductive organs of polyploids generally tend to exhibit larger morphology, but not always. In the present research, octoploid blueberries didn't produce the larger fruit as intended. The failure of seeds to mature properly leads to ineffective synthesis of plant hormones, failing to expand the fruit. The fruit set rate of the octoploid blueberry plants was lower, possibly because blueberries have low self-pollination compatibility and there is a lack of pollinated trees with equal ploidy level. The decrease in the fruit setting rate of octoploid blueberries may also be due to pollen developmental disorders. A study had revealed that the pollen tube tips of artificial tetraploid Arabidopsis have growth defects, leading to almost complete sterility of the plants[35]. Interestingly, we found that the number of sepals and carpels in the octoploid fruits increased compared to the control, and the specific mechanism of this occurrence needs further research.

-

Pluripotent calli were induced from leaf explants cultured on modified WPM medium with zeatin in the dark for 15 d. The explants were subsequently cultivated on a medium containing 2−10 mg/L trifluralin or 200 mg/L colchicine for 2 d, after which they were transferred to a regeneration medium and cultured under light for 30 d. This process was found to induce the occurrence of polyploid blueberries. The induction efficiency of trifluralin was higher than that of colchicine. The induced polyploid plants are all octoploid, and it can be observed that the stomata are enlarged and their density distribution is reduced. Compared with tetraploids, octoploid blueberry had thicker stems and larger leaves, more canes, and earlier flowering phase, but the chromosome doubling in tetraploid blueberries may hinder plant development, seed maturation and fruit setting. In summary, this study has established a method for inducing chromosome doubling in blueberries using trifluralin under in vitro conditions, characterized by safety, stability, and low likelihood of chimera formation, which provided an alternative protocol in blueberry polyploid breeding.

This work was supported by the Key Scientific Project of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (No. 17391900800) and the Shanghai Sailing Program, China (No. 23YF1439600).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li S, Zhang X; data collection: Li S, An H; analysis and interpretation of results: An H, Zhang J; draft manuscript preparation: Li S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li S, An H, Zhang J, Zhang X. 2025. Artificial induction of chromosome-doubled highbush blueberries from pluripotent calli by trifluralin and colchicine. Technology in Horticulture 5: e015 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0010

Artificial induction of chromosome-doubled highbush blueberries from pluripotent calli by trifluralin and colchicine

- Received: 28 December 2024

- Revised: 06 February 2025

- Accepted: 17 February 2025

- Published online: 09 April 2025

Abstract: Artificial chromosome doubling of somatic cells enables the production of polyploid plants, which can then be employed in the breeding of novel varieties exhibiting superior traits. To induce polyploids in highbush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum), pluripotent calli were regenerated from leaves of a tetraploid southern highbush blueberry cultivar 'Diana', and subsequently treated with trifluralin or colchicine. The chromosome ploidy level of the regenerated shoots was determined using a flow cytometer. The results demonstrated that following the inoculation of leaves onto regeneration medium and subsequent culturing in the dark for 15 d, the application of 2−10 mg/L trifluralin or 200 mg/L colchicine for 2 d could result in the generation of chromosome-doubled plants. Trifluralin was proven to be a more efficacious agent than colchicine. The test showed that 15 octoploids were obtained using trifluralin, while three octoploids were obtained using colchicine, and no chimera occurred. The leaf stomata are enlarged and the density distribution of stomata is reduced in chromosome-doubled plants. In comparison to the tetraploid blueberry, the octoploid plants exhibited thicker stems and larger leaves, more canes, earlier flowering, and an enhanced number of sepals and locules structures. Nevertheless, the chromosome doubling in tetraploid blueberries may result in the formation of dwarf plants, the inhibition of seed maturation, and a reduction in fruit set. In conclusion, a methodology for inducing chromosome-doubled blueberries has been established and characterized by safety, stability, and a minimal likelihood of chimera formation.

-

Key words:

- Blueberries /

- Polyploid /

- Chromosome doubling /

- Trifluralin /

- Colchicine