-

Medicinal plants serve as one of the significant sources of biologically active molecules such as artemisinin, sappanone A, and paclitaxel, which play a vital role in the treatment of human diseases[1−3]. Although there is significant market demand for these natural products, low abundance, and the difficulty of extraction and purification have resulted in premium pricing for related products and very low utilization rates.

The ultimate goal of medicinal plants is to create high contents of active ingredients. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to elucidate the pathways of these compounds and highly improve biosynthesis efficiency. With the rapid development of high-throughput sequencing, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), and multi-omics approaches, it is now possible to uncover genetic elements[4]. These methods however have rendered the identification of candidate genes low-efficient and unreliable. Currently, Artificial intelligence (AI) in the field of biology has demonstrated significant potential applications to mine candidate genes[5].

Enzyme modification and rational design are also critical components for the efficient synthesis of medicinally active ingredients. Various techniques such as X-ray crystallography, homology modeling, and site-directed mutagenesis are commonly employed for enzyme structure prediction and modification[6]. Currently, Large Language Models (LLMs) such as AlphaFold 3 (AF3), Evolutionary Scale Modeling (ESM), and Evo have revolutionized the field of high-precision protein structure prediction, which might significantly promote the discovery of super-active enzymes[7−9].

Here, this review systematically elaborates on AI technology in the application of biological elements. We investigate current advances in plant natural product biosynthesis, AI-driven discovery, and modification of biological elements in medicinal plants, future trends and challenges of precision medicinal plant breeding, and biosynthesis using AI.

-

The active ingredients in medicinal plants, such as terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids, play a crucial role in the treatment of numerous diseases[10,11]. With the swift development of genome sequencing, key enzymes or pathways of some significant active ingredients have been clarified (Table 1).

Terpenoids are important active substances for medical application in humans[10]. The biosynthesis of terpenoids is mainly through the Mevalonic Acid (MVA) Pathway. The precursors of QS-21, Limonoids, and Astragaloside are all synthesized via the MVA pathway. β-amyrin synthase and three cytochrome P450 enzymes generated core skeleton quillaic acid (QA) for QS-21[10]. In addition, seven key enzymes and four different types of enzymes enabled the synthesis of QS-21. Melianol Oxide Isomerases (MOIs) are responsible for the conversion of melianol to different limonoids skeletons via epoxidation intermediates[12]. The biosynthesis pathway from cycloastragenol to astragaloside IV encompasses four key steps: C-3 oxidation, 6-O-glucosylation, C-3 reduction, and 3-O-xylosylation[13].

Alkaloids are a class of biologically active nitrogen-containing organic compounds that have a variety of physiological effects on the human body[14]. The main alkaloid biosynthesis pathways are the amino acid derivation pathway, the isoprenoid pathway, and the dopamine pathway. The alkaloids are diverse, with Paclitaxel and Colchicine coming via the mevalonate pathway, and Amaryllidaceae alkaloids, and Strychnine being amino acid derived pathways. Two missing key enzymes 'T9αH' and 'TOT' were discovered and characterized, thus elucidating the mechanism of paclitaxel oxetane formation[2]. The critical role of the enzymes CYP96T1 and CYP96T6 in the biosynthesis of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids was demonstrated in this study[14]. GsCYP71FB1 generated N-formyldemecolcine via an atypical oxidative ring expansion reaction, a key step in colchicine backbone synthesis[15]. SnvWS and SnvAT generated Wieland-Gumlich aldehyde and N-malonyl Wieland-Gumlich aldehyde, respectively, which are key steps in the generation of the stilbene backbone[16].

Flavonoids are currently the prominent small molecules of significant interest. Although flavonoids are structurally diverse, their basic skeletons are synthesized via the Phenylpropanoid Pathway. Three key genes were identified in the anthocyanin synthesis pathway in Camellia sinensis: flavanol synthase (FLS), dihydroflavonol-4 reductase (DFR), and anthocyanin synthase (ANS). Homoisoflavonoids represent a rare and unique subclass of flavonoids, distinguished by their extended carbon skeleton (C9) between the B and C rings. Unlike the widely distributed isoflavonoids, homoisoflavonoids are limited to only a few species, most notably Caesalpinia sappan and Polygonatum cyrtonema, making them exceptionally valuable in natural product research. ChOMT from Medicago truncatula catalyzed methylation of Isoliquiritigenin, which might be an initiation step in the synthesis of homoisoflavonoids[17]. An apiosyltransferase GuApiGT from Glycyrrhiza uralensis could efficiently catalyze 2″-O-apiosylation of flavonoid glycosides[18]. CreOMT3, CreOMT4, and CreOMT5 p-hydroxyflavones exhibited multisite O-methylation activity, generating seven Polymethoxyflavones (PMFs) in vitro and in vivo[19].

Table 1. Recent progress in dissecting natural product pathways in medicinal plants.

Types Active ingredients Enzymes Plant source Medicinal activity Ref. Terpenoid QS-21 CCL1, PKSIII, KR, ACT2/3, UGT73CZ2 Quillaja Saponaria Vaccine adjuvant [3,10] Limonoid OSC, CYP71CD1, MOI2, L21AT, SDR, L1AT, AKR, LFS Citrus sinensis,

Melia azedarachBiopesticide [12,20,21] Astragaloside AmOSC3, AmCYP88D25, AmCYP88D7, AmCYP71D756 Astragalus membranaceus Anticancer [13] Alkaloid Paclitaxel TOT1, T9αOH, TS, T5αOH, T13αOH, T10βOH, TAT, T7βOH, T2αOH, TBT, DBAT, T1βOH Taxus chinensis Anticancer [2,22] Amaryllidaceae alkaloid CYP96T1, CYP96T6, CYP96T5, NtSDR2, NtODD2, NtOMT1, NtNMT1, NtAKR1 Narcissus tazetta Treating Alzheimer's disease [14] Colchicine GsOMT1, GsNMT, GsCYP75A109, GsOMT2, GsOMT3, GsCYP75A110, GsOMT4, GsCYP71FB1 Gloriosa superba Antigout [15] Strychnine SnvGO, SnvNS1, SnvNO, SnvWS, SnvAT, AAE13, Snv10H, SnvOMT, Snv11H Strychnos nux-vomica Biopesticide [16] Flavonoid Homoisoflavonoid ChOMT Medicago truncatula Anti-neuroinflammatory [17] Liquiritin apioside GuApiGT Glycyrrhiza uralensis Cough suppressing [18] Polymethoxyflavone CreOMT3, CreOMT4, CreOMT5 Mandarin Anticancer [19] Although several biosynthesis pathways of active ingredients have been elucidated, biological elements in medicinal plants remain largely unknown.

-

As human society enters a new era of AI, the mining of medicinal plant elements is undergoing historic transformations. Discovery and characterization of biological elements will advance rapidly supported by integrating technological advantages from life sciences and information sciences, including high-throughput sequencing, bioinformatics, gene editing technologies, synthetic biology, and machine learning technologies. The core concept of 'AI-driven discovery of Biological Elements' is proposed that lies in applying AI to precision prediction with enzyme function, gene networks, protein structure, and interaction. Building on this foundation, innovative models are being developed to further enhance our understanding of biological elements.

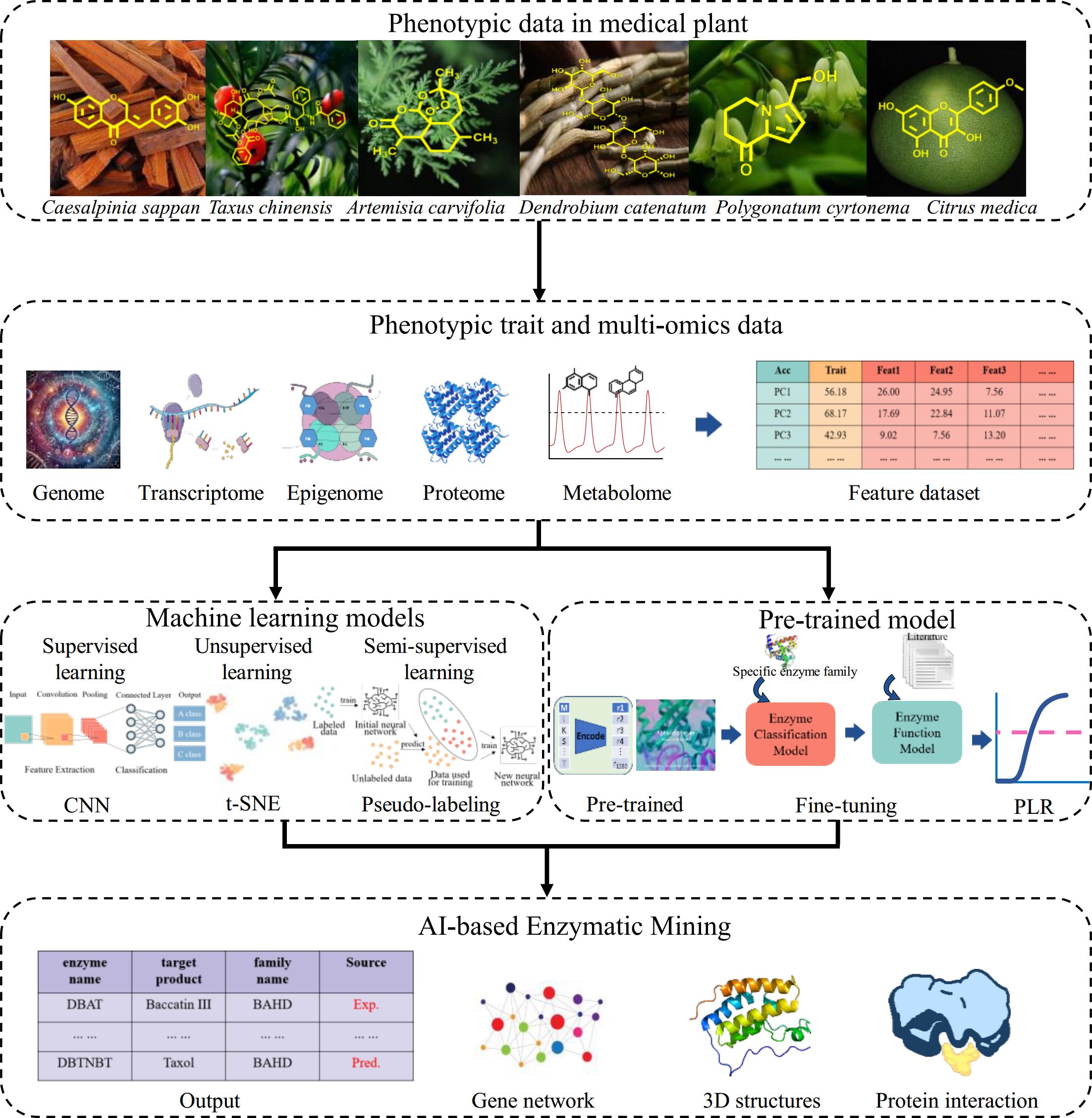

An analogy of 'fishing' that means mining of trait-related genes or genetic mechanisms could be used to clarify the difference between AI-based and traditional gene-mining methods. QTL mapping or GWAS is like 'single-line fishing' that usually contains one or several major markers by identifying broad regions in the genomes associated with traits but often lacks resolution and precision, whereas multi-omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, epigenomics, metabolomics) resembles using 'wide-net fishing' methods that captures a wide range of genetic information and many trait-related genes or pathways. However, large false positive results are acquired from this analysis. Compared to traditional mining of biological elements, AI-driven discovery provides more precise and efficient ways to predicate active ingredient-related enzymes. The ways to mine candidate genes can be called 'smart wide-net fishing', such as a generative model EMOGI based on graph convolutional networks that identified 165 previously undiscovered cancer genes[5]. The four main steps where AI holds the potential to dissect the genetic mechanism of active ingredients are : 1) the collection of phenotypic data for active ingredients in medicinal plants; 2) feature extraction of multi-omics data; 3) biological elements mining using machine learning models or pre-trained model; and 4) AI-based predicative biological elements (Fig. 1). A crucial initial step is to collect phenotypic resources including the chemical structure and content of active ingredients. Then these phenotypic data are integrated with multi-omics data such as transcriptome, epigenome, proteome, and metabolome to form a feature dataset, which is further used for building machine learning and pre-training models to precision predictive biological elements.

In addition, the study of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) can significantly accelerate the pathway discovery of specific metabolites. Traditional methods for identifying natural product BGCs primarily rely on rule-based approaches and statistical learning techniques, such as MetaBGC, Plant Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell (PlantiSMASH), and PRediction Informatics for Secondary Metabolites (PRISM)[23,24]. These methods excel at detecting known BGC classes but are less effective in identifying novel BGC types or unclustered pathways. In contrast, AI approaches offer significant advantages for predicting new gene clusters. For instance, ClusterFinder, which is based on Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), efficiently identifies new gene clusters and makes functional predictions by comparing known metabolic gene clusters with new data. The MetaBGC approach is a reads-based algorithm that identifies, quantifies, and aggregates microbiome-derived BGCs at the level of individual macro-genomic reads, using community portrait-based HMMs. GECCO is a Conditional Random Field (CRF)-based gene cluster prediction method that accurately identifies gene clusters by combining genome sequences with known gene cluster structures. The method identified 107,856 gene cluster families, half of which are found in microorganisms highly prevalent in the human gut[25]. However, a deep learning-based model DeepBGC enhances genomic data mining by learning patterns and features of gene clusters to identify previously uncharacterized clusters. These AI-driven methods are trained on features such as gene sequences, functional domains, and enzyme information, allowing them to efficiently predict unknown gene clusters and reduce reliance on manual annotation[26].

The training of machine learning models can be broadly divided into three categories: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and semi-supervised learning. Supervised learning models can achieve significantly high accuracy with a large amount of data and high-quality labels, which has been widely used in classification and regression tasks, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Vision-Language Models (VLMs)[27−29]. Traditional CNNs mainly work with images or videos, but VLMs can handle both images and text together. As a result, VLMs are better suited for complex cross-modal tasks. CNNs focus on gene data, while VLMs use images and text to link genes to their functions[30]. VLM can also learn the 3D structural features of proteins and predict their functions. The model performs well on the task of protein structure and function prediction, significantly improving the accuracy of the predictions[31]. However, the scale of the training data and the sampling scope limit the model's generalization performance in supervised machine learning. In contrast, unsupervised learning can directly process the raw data without labels to uncover underlying patterns and data structures, making it particularly useful for dimensionality reduction, clustering, and other similar tasks. Notable algorithms in this category include t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), Generative Adversarial Network (GAN), Self-Organizing Map (SOM)[32−34]. Semi-supervised learning is a method that co-trains models using a small amount of labelled data along with a large amount of unlabeled data. This approach combines the advantages of supervised and unsupervised learning, playing a crucial role in enhancing models while reducing the cost of labelling. Nowadays, some machine learning methods have been used to mine candidate genes in the biosynthetic pathways of medicinal plants. Machine learning methods were applied to identify genes associated with flavonoids and terpenoids in medicinal plants[35]. SVM and Random Forest machine learning methods identified four new feature genes (PcCHS1, PcCHI, PcCHS2, and PcCHR5) for the accumulation of flavonoid compounds in P. cyrtonema Hua[36].

Recently, LLMs related to the biological field have accelerated the development of structural biology and functional genomics (Table 2). Based on a transformer architecture, AlphaFold 2 (AF2) which has trained on 200 million protein sequences extracts features from evolutionary information and utilizes multiple sequence alignments (MSA) to generate alignment matrices, capturing relationships between residues to indirectly predict protein structures[37]. AF3 model with a substantially updated diffusion-based architecture is capable of predicting the joint structure of complexes including proteins and small molecules. As a result, it can be applied to high-precision protein interaction network predictions and structural modeling of protein complexes[7]. ESM-2 is a Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) based LLM, trained on approximately 65 million unique protein sequences with the Masked Language Modeling (MLM) approach, which can predict protein structures from single protein sequences accurately[38]. In contrast to the AF2 model which relies on multiple sequence alignments, the ESM-2 model focuses on a single protein sequence with a known three-dimensional structure and can be up to 60 times faster. Compared with ESM-2, ESM-3 achieves significant improvements in both accuracy and speed through a deeper transformer architecture and larger-scale training data, making it more effective in predicting protein structures from single sequences[8]. Similarly to AF3, ESM-3 is capable of performing tasks such as protein function prediction and protein-protein interaction analysis. Based on the transformer architecture, ProtT5 is a bilingual model trained on protein sequences and structures[39]. It encodes protein structures as token sequences using the 3Di-alphabet introduced by the 3D-alignment method Foldseek, enabling structure-based structure prediction. The 3Di sequences predicted by ProtT5 outperformed traditional sequence-based alignment methods in identifying distantly related proteins and offer structure-level search sensitivity to sequence-searches orders-of-magnitude faster. Additionally, RNA sequences and DNA sequences can also be utilized to develop AI models. The Enformer algorithm based on the transformer architecture can predict genome long-range interactions up to 100 kb. On the other hand, the RNABERT algorithm based on the BERT architecture can also compare and cluster RNAs[40,41]. In terms of whole genome sequences, Evo is an LLM based on the StripedHyena architecture, which has an advantage over other transformer architecture prediction models when dealing with genomic data with longer genomic sequences. It combines attention mechanisms with data-controlled convolution operators to efficiently process and recall patterns in long sequences, ranging from single nucleotides to entire genomes. This enables it to predict and generate DNA, RNA, and protein molecules and also demonstrates strong performance in predicting DNA sequences' function[9].

Table 2. Biological pre-trained models.

Data type Models Architecture Data sources Ref. Protein sequence ESM-2/3 BERT UniRef50, UniRef90, PDB [8,29] AlphaFold2/3 Transformer (attention mechanism) PDB, BFD, UniRef90, MGnify, RFam, RNAcentral, JASPAR [7,37] Protein sequence and structure ProtT5 Transformer PDB, AFDB [39] DNA/RNA Enformer Transformer Gencode [40] RNABERT BERT Rfam, BRAliBase2.1 [41] Whole-genome Evo StripedHyena GTDB, IMG/VR, IMG/PR, NCBI RefSeq, MGnify, MGRAST, UHGG, JGI IMG [9] LLMs have potential revolution for identifying biological elements by harnessing their natural language understanding abilities. Based on pre-training models such as ESM and AlphaFold, fine-tuning of transformer architecture is performed with data from accuracy databases like specific enzyme families and relevant literature. Pre-trained models are initially trained on large amounts of unsupervised textual data to capture features like language patterns and contextual information. In contrast, fine-tuning a language model involves supervised training on a specific task or dataset, building upon the knowledge gained from the pre-trained model. DeepVariant employs deep learning models, particularly CNNs, which are pre-trained on extensive genomic datasets to learn robust feature representations of genomic sequences. Through fine-tuning, DeepVariant demonstrates exceptional performance in genomic variant detection tasks, thereby markedly enhancing the precision of variant identification[42]. Finally, feature importance is evaluated as the model's output, which helps us to understand the model's decision-making process, thereby improving a models interpretability and guiding further experimental verification. A novel CNN-based AI framework, DeepMineLys, is also proposed which successfully identified lysosomes with potential antimicrobial properties[43]. The most promising candidate is 6.2 times more active than hen egg white lysozyme (HEWL) which is the most active lysine found in the human microbiome to date. The antimicrobial lysosomes identified through AI offer new possibilities for antimicrobial therapy. This paves the way for advancements in precision medicine. Another LLM GPS-SUMO 2.0 model collecting 145,545 non-redundant lysine modification sites from the CPLM 4.0 database learns the contextual information between lysine modification sites and other residues on protein sequences, thereby constructing a language model for lysine modifications. It is fine-tuned by multiple non-redundant phosphate sites and phosphorylation-dependent interaction motifs. Additionally, penalized logistic regression and deep neural networks are employed to learn the physicochemical properties adjacent to phosphorylation sites, enabling precise learning of both 'contextual + adjacent' information[44].

In conclusion, AI-assisted mining of biological elements will definitely accelerate the biosynthesis of active ingredients in medicinal plants. From the interpretation of AI models to the characterization of key biosynthesis enzymes, AI is gradually becoming the unignorable driving force to efficient biosynthesis of natural products.

-

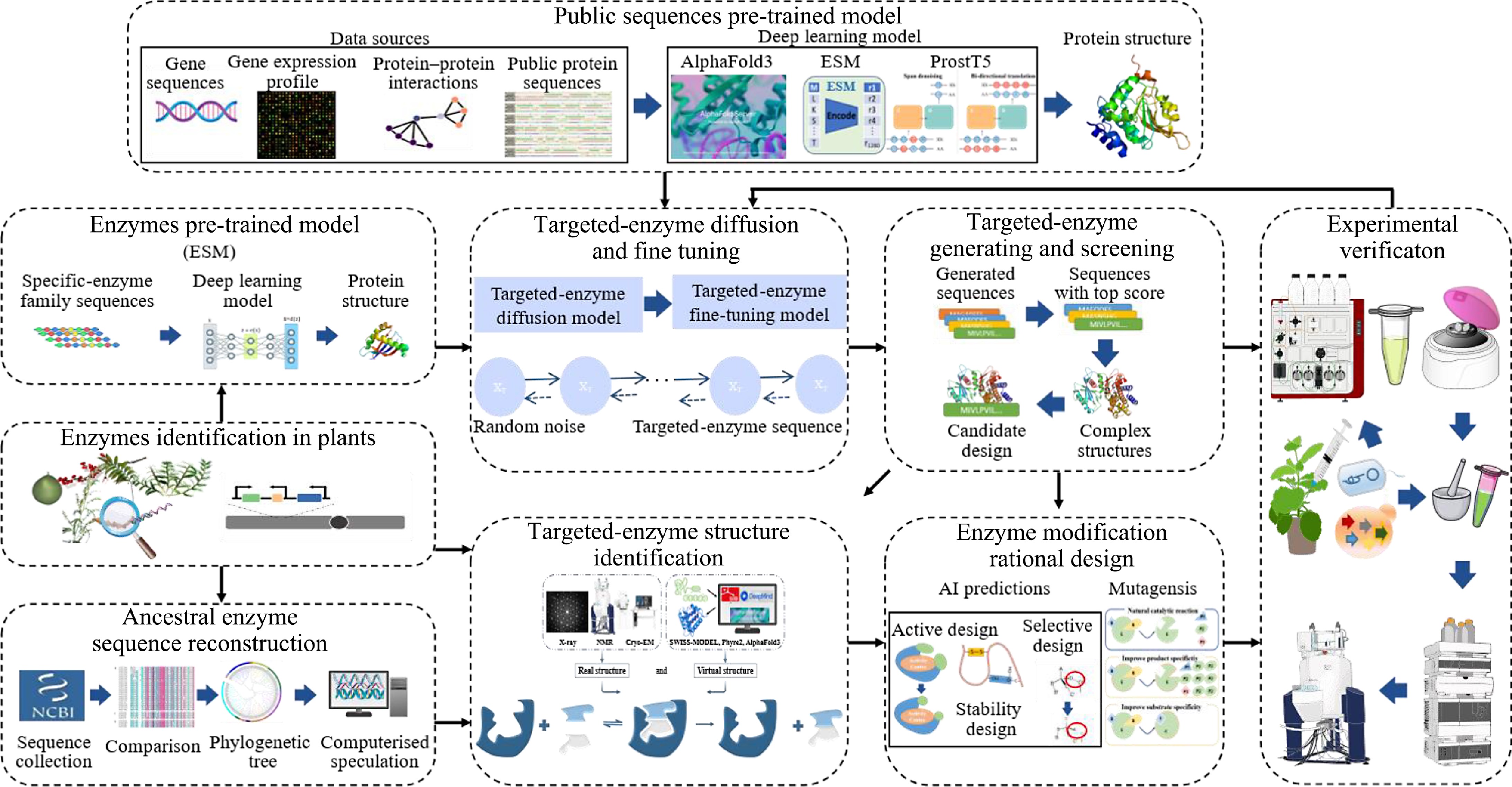

Enzyme modification and rational design are also crucial for the efficient and high-quality synthesis of natural products. AI prediction and biological experimental methods are often applied for the modification and rational design of enzymes (Fig. 2). The targeted enzyme can be predicted by a pre-trained model, and then the structure of the high-active enzyme can be generated by diffusion and fine-tuning. The protein structure also can be obtained through the ancestral enzyme sequence reconstruction method, and the desired protein conformation is achieved by rational design. Finally, the functions of the obtained proteins are experimentally verified and the validated proteins are reapplied to fine-tune the pre-trained model.

The AI method can be used to design the enzyme in terms of activity, selectivity, and stability. Based on pre-trained LLMs, the next step is to further optimize the models by targeted-enzyme diffusion and fine-tuning. Gaussian noise is gradually added to the enzyme sequence through the forward diffusion process until it becomes random noise. In the reverse generation process, the sequence is denoised starting from the random noise, and the enzyme sequence is regenerated[45]. After several rounds of training, the model can generate a diverse range of sequences with some functional similarities to our targeted-enzyme. Furthermore, by performing structural alignment, more reliable protein sequences with functional similarities to the targeted enzyme can be identified from the sequences generated by the model. These sequences can be used for structural identification, rational design, and final experimental validation of the enzyme. A generative pipeline combining diffusion modelling and variational autocoders (VAE) enables the design of novel antimicrobial peptides (AMPs)[46]. It designs nine highly active candidate peptides. These AMPs demonstrate significant in vivo therapeutic efficacy in multiple mouse models, highlighting their potential as promising lead molecules for the development of new antimicrobial agents. The accurate and efficient discovery of AMPs leveraging generative AI holds significant potential to address the global challenge of antibiotic resistance.

Enzyme ancestral sequence reconstruction is also performed to mine ancestral enzymes with high active performance[47]. Based on pre-trained screening sequences, ancestral enzyme sequences, and identified plant enzyme sequences, the three-dimensional structure is determined by experimental and computational methods. The actual structure of the protein is directly resolved by X-ray Crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and Cryo-EM. Alternatively, virtual structures can be obtained through homology modeling of enzyme sequences using tools like SWISS-MODEL and Phyre2 or through protein structure prediction using AF3.

After acquiring optimized enzymes, experimental methods, typically involving targeted mutagenesis experiments, are conducted by introducing amino acid substitutions, insertions, or deletions at specific positions to optimize enzyme activity, heat resistance, or substrate specificity. Then prokaryotic (E. coli) or eukaryotic (yeast and tobacco) expression systems are usually used to express and validate the functions of modified proteins. Finally, product characterization and quantification are performed using Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) or Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), and structure resolution is performed using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR). The characterized enzymes are also used as inputs to the diffusion and fine-tuning to optimize AI models.

-

Generative AI is rapidly transforming operations in biological and medical fields, leveraging its advanced natural language processing capabilities for applications such as target identification, virtual screening, and de novo design. Generative AI is capable of developing potential therapeutic drugs by identifying novel drug targets, analyzing complex biological networks, and constructing multi-omics data networks. Furthermore, it can predict ligand spatial transformations, generate complex atomic coordinates, and learn the probability density distribution of receptor-ligand distances to generate binding poses, thereby identifying potential lead compounds or drug candidates. Despite the tremendous advantages of generative AI, the complexity of biology needs an approach that can flexibly break down complex problems into actionable tasks. In healthcare, agent AI can assist physicians in formulating treatment plans and monitoring patient health by making decisions and planning based on real data. Agent AI enhances the efficiency of routine tasks and automates continuous, high-throughput research[48].

Generative AI and agent AI have diverse and impactful applications in the biomedical field. GPS 6.0 utilizes public phosphorylation sites (ssKSRs) to predict kinase-specific phosphorylation sites, which also provides biologists with a user-friendly online service for predicting kinase-specific phosphorylation sites and offers comprehensive annotations of the prediction outcomes[49]. BioChatter is an open-source Python framework that includes several modules, such as the LLM provider Application Programming Interface (API), database public API, knowledge management systems, and various software components. Users can customize the entire process, from prototyping to packaging and deployment, based on their specific needs using the different modules. This flexible and modular architecture supports a wide range of biomedical research contexts, making BioChatter an ideal tool for facilitating generative AI applications in the biomedical field[50]. OpenPath is a generative AI model fine-tuned through comparative learning. It was pre-trained using Pathology Language-Image Pre-training (PLIP) on an extensive dataset comprising 208,414 de-identified pathology images paired with corresponding natural language descriptions, both sourced exclusively from Twitter. The model demonstrates the capability to classify new images without requiring additional training, thereby assisting clinicians in disease diagnosis. Furthermore, OpenPath supports case retrieval through image-based or natural language-based searches, significantly enhancing knowledge sharing and clinical decision-making[51]. DrBioRight 2.0 is an agentic AI platform powered by a large language model. It integrated approximately 8,000 samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) patient tumors and 900 samples from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) cell lines for training. Leveraging OpenAI GPT-4/4O and Llama 3 models, it generates answers to user queries. The tool is designed to reduce technical barriers and facilitate seamless analysis of protein-centric canceromics data. Users from diverse backgrounds can effortlessly access, analyze, and visualize data through intuitive natural language queries[52]. Artificial intelligence, particularly generative AI and agentic AI, is revolutionizing the biological research or medical field. For the mining and modification of pathway genes in medicinal plants, generative AI also can identify novel genes and metabolic pathways efficiently. Agentic AI streamlines data analysis and automates tasks, optimizing research efficiency, which will provide a new research paradigm.

-

The main active ingredients of medicinal plants have been demonstrated in multiple studies to exhibit significant clinical efficacy. Despite progress in the study of biosynthetic pathways for active components in medicinal plants, a substantial number of pathway enzymes remain unidentified, which seriously hinders the efficient biological synthesis in non-native species. Traditional methods, such as GWAS, QTL, and multi-omics data analysis for gene mining, often suffer from low precision and generate a high number of false positives. With the rapid advancement of various high-throughput omics technologies, a shift in mining paradigm is moving towards an AI-driven era. AI technologies could potentially revolutionize biological element mining in medicinal plants. With continuous advancements in optimization algorithms, big data analysis, and deep learning technologies, an increasing number of AI-based methods have been applied to direct enzyme engineering. By integrating LLMs the approach aims to achieve AI-driven discovery and modification of enzymes in medicinal plants. Leveraging a curated database of DNA/protein sequences and metabolite bioactivity correlations, this model integrates AI-driven causal inference algorithms to perform automated homology-based comparative analysis of unknown DNA sequences, enabling the prediction of potential bioactive metabolites and their functional activities. In addition, we present a multimodal deep-learning framework combining protein sequences with metabolite annotations. Using function-focused transfer learning on small datasets, a pre-trained language model extracts enzymatic catalytic features and substrate specificity, followed by attention-guided adaptive fine-tuning to transfer biosynthetic patterns to large compound libraries.

AI in biology still faces several challenges, notably the lack of large, well-managed, and publicly accessible datasets, limitations in computational power, poor generalization to datasets, and insufficient model interpretability. To address these issues, it is crucial to standardize the development of open platforms, ensure consistent and high-quality data annotations, and optimize algorithms to enhance computational efficiency and model performance. Additionally, integrating multimodal data such as genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics can improve the generalization ability of models. Furthermore, methods like attention mechanisms, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), and Layer-wise Relevance Propagation (LRP) should be utilized to enhance model interpretability.

In the future, a complete AI-predicted pathway for active compound development will enable more efficient mining processes in medicinal plants: 'precision net fishing' of gene clusters or biological elements, more accurate prediction of biological elements' function, substrates, and products, and better assessment of the bioactivity of active ingredients. AI in biology can also be used to optimize multiple metabolic pathways to enhance the content of active components in medicinal plants. Additionally, generative AI is revolutionizing bioscience by enabling de novo enzyme design and rapidly identifying hidden metabolic pathways in medicinal plants. Agentic AI automates data analysis and optimizes experiments, boosting research efficiency. Research field-specific AI chatbots (e.g., ChatGPT-like interfaces) can also simplify complex problem-solving through natural language interactions. Together, these innovations accelerate drug discovery, metabolic engineering, and sustainable biomanufacturing, promising transformative breakthroughs in medicine and green industries. In summary, AI serves as a core driving force in medicinal plant applications, that could provide potentially promising transformative breakthroughs in efficient biosynthesis dissection of bioactive compounds and precision medicinal plant breeding.

This research was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD2200600), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32200214).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, manuscript review and supervision: Han Z, Dong C; draft manuscript and figure preparation: Zhang J, Yang Y; manuscript review: Si J, Chen D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Jing Zhang, Yixin Yang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang J, Yang Y, Si J, Chen D, Dong C, et al. 2025. Artificial intelligence in the discovery and modification of biological elements in medicinal plants. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e012 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0010

Artificial intelligence in the discovery and modification of biological elements in medicinal plants

- Received: 17 December 2024

- Revised: 13 March 2025

- Accepted: 21 March 2025

- Published online: 16 April 2025

Abstract: Active ingredients extracted from medicinal plants are important natural sources in the field of pharmaceutical and industrial products. However, the low abundance and quality of these compounds have consistently posed a significant barrier to the full utilization of these ingredients. The discovery of enzymes in related pathways, enzyme activity modification, and pathway optimization are key to solving this problem. The emergence of large-scale multi-omics data has provided new opportunities to enhance this progress. But a new big challenge in analyzing the massive amounts of biological data lies before us. Artificial intelligence (AI) is state of the art for its process in big data and pattern recognition that has already had a revolutionary impact on biological fields. Here, we summarize recent advancements in pathway analysis and research ideas in AI-mediated discovery and modification of biological elements. Future directions and challenges for applying AI in precision medicinal plant breeding, and the biosynthesis of optimized, stable, and cost-effective natural products are also discussed.

-

Key words:

- Artificial intelligence /

- Medicinal plants /

- Enzyme discovery /

- Enzyme modification