-

The safe operation of flights has received much attention in civil aviation. Aircraft weight and balance (AWB) is a vital part of ensuring the safe operation of flights. A qualified load plan not only ensures the safe operation of flights but also improves economic efficiency. When passenger flights are loaded, the load plan is determined primarily by the allocation of passengers' seats in the section and their average weight. Therefore, the passenger is a significant calculated element in the load plan of passenger flights.

However, the AWB planning does not distinguish body weight differences between men and women normally. Airlines regard the body weights of all passengers as a fixed value (e.g.75 kg), which ignores the differences in the weight of various passengers. It leads to the potential deviation of the center of gravity (CG) in passenger flight loading and increases the risk to the operation of flights. Besides, when making passenger seat allocation plans, airlines usually hope that the CG of flights (BCG) is as aft as possible for saving fuel and reducing costs. However, due to the CG envelope, airlines will provide a target CG (TCG) within the envelope. It is required that the BCG is as close as possible to the TCG. The potential deviation of the CG (|BCG − TCG|) due to the passenger weight discrepancy may lead to additional fuel consumption and increasing operation costs.

Therefore, the motivation of this paper is to provide an approach to reduce the deviation of CG caused by body weight uncertainty of passengers.

A stochastic programming model with two stages was given based on the questions mentioned above. The model was developed to permit the flight plan to adapt to different passenger weight scenarios, resulting in a decrease in the impact of passenger weight uncertainty on flight operations. In the first stage, the load plan of each cargo hold was determined. In the second stage, the expectation of passenger seat allocation solution was given based on the random weight of passengers and the recourse of the deviation of CG was in the first stage. Through numerical experiments, it was demonstrated that the model can control the deviation of CG in each scenario in a safe range and reduce the deviation of CG caused by passenger weight uncertainty.

The contribution of this paper is to consider passenger weight uncertainty to develop a load and balanced model that reduces the potential bias in the CG of an aircraft.

-

Airlines' primary business initiative is air transportation, and AWB is a crucial component of it. This research reviews the literature from three perspectives: the uncertainty of AWB, the aviation weight and balance, and the uncertainty optimization approach.

Aircraft weight and balance

-

The AWB of air cargo is to pick a collection of cargoes and allocate them to different predetermined holds and positions on an aircraft, taking into account the numerous position constraints, weight and balance limits, and operation needs, to maximize transportation profit while minimizing CG deviation. Several studies have been published, such as Limbourg et al.[1], Vancroonenburg et al.[2], Feng et al.[3], Lurkin & Schyns[4], Brandt & Nickel[5], Zhao et al.[6], Zhao et al.[7], and Desai et al.[8] are a few notable examples.

The current AWB of passenger flights can be simplified to a relatively simple one-dimensional assignment problem due to the common acceptance that the passenger's body weight has the same value. Therefore, the problem of allocating passenger seats has not been extensively studied, but it has been a common occurrence to combine it with other problems. Notomista et al.[9] introduced a procedure to minimize the turnaround time by speeding up the boarding time in passenger aircraft. Milne & Salari[10], proposed a mixed integer programming model that determines the number of luggage to be carried by passengers assigned to each seat. Schultz[11], provided a comprehensive analysis of the innovative approach of a Side-Slip Seat, which allows passengers to pass each other during boarding, and a validated stochastic boarding model is extended to analyze the impact of the Side-Slip Seat. Melis et al.[12] established analytical methods to explore the effects of passenger weight change on selected aircraft mission performance attributes. The results show that deviations from the average passenger weight owing to different obesity prevalence rates can significantly compromise safety margins. Schultz & Soolaki[13], focus on the time-critical process of aircraft boarding, where regulations regarding physical distances between passengers will significantly increase boarding time. Birolini et al.[14] developed an integrated optimization framework—referred to as the Integrated Connection Planning and Passenger Allocation Model—to support low-cost airlines in the early stage of connection planning, encompassing the definition of the most promising transfer airports and the set of optimal connecting itineraries to be rolled out over an existing network of flights. Ren et al.[15] investigated passengers' seat selection behavior and used the latent class conditional logit model to classify passengers based on seat selection preference, and construct a model of willingness to pay for seat selection through logit regression. Pardo González et al.[16] introduced a sophisticated Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model specifically designed to optimize revenue from seat change fees. Tang & Hsu[17], studied optimal aircraft seat assignment for infectious diseases in view of the stochastic risk of infection for a passenger assigned to a seat.

Uncertainty optimization

-

Nowadays, optimization methods for uncertainty-containing problems are primarily characterized as chance-constrained programming, two-stage stochastic programming, dynamic programming, resilient optimization, and so on. The two-stage stochastic programming technique with recourse requires the upper-level and operational-level decisions to be made in sequence. The model in the first stage is deterministic, yielding an initial solution (about cargo). Subsequently, the determined environment transitions into a stochastic setting, wherein in the second stage an expected optimal solution (about passenger) is identified. With recourse, the decision variables in the first and second stages are coupled, thus the upper-level decision will be affected by the operational-level decision. In other words, the solution in the second also influences the first stage in return. Finally, the result of the model will create a balance between cargo and passengers. Related works include Birge & Louveaux[18], Crainic et al.[19], Powell[20], Crainic et al.[21], Yilmazlar et al.[22], and so on.

Uncertainty optimization research in civil aviation

-

Uncertainty research in civil aviation normally improves the economics of flights and speeds up the efficiency of operations. Ferguson & Dantzig[23] illustrated an application of linear programming to the problem of allocation of aircraft to routes to maximize expected profits with the uncertain customer demand.

Wu[24] proposed a hybrid 0−1 integer model to determine the booking type and number of containers. A dual-response forwarding system is developed to address the uncertainty problem when precise information is unavailable at the time of booking. The initial step is to determine the booking type and quantity of containers. The second step involves being ready for various scenarios that could happen during shipment day, including the type and number of containers that will be needed or returned in each scenario, and the corresponding loading schedule. The calculation indicates that the stochastic model has the ability to provide a cargo transshipment system that is cost-effective, flexible, and responsive.

Zhao & Xiao[25] provided a row-based and section-based integer programming models for passenger allocation. The accuracy of CG control was evaluated by comparing the row-based and section-based allocation techniques, taking into account different bodyweights and numbers of passengers.

He et al.[26] used visual analysis and uncertainty measure theory, along with parallel coordinates and other charts, to offer data uncertainty analysis and visualization methods. It reveals hidden information for passenger service recommendations.

Yang et al.[27] considers uncertainties to accurately quantify the aviation carbon emission path, determines the gap with the emission—reduction target, and offers mitigation measures. The Delphi method identifies key carbon—emission drivers and sets uncertainty—considered scenarios. Backpropagation neural networks and Monte Carlo simulation quantify the path. Results show China's civil aviation can effectively help achieve carbon peaking and neutrality goals.

Currently, there is not enough research on uncertainty in AWB. There is uncertainty in the passenger body weight of every flight in civil aviation transportation. Airlines treat all passenger weights as a certain constant, which may cause the aircraft's CG to have a potential deviation towards uncertainty. This operation procedure results in the takeoff CG exceeding the CG envelope, which poses a risk to flight safety.

Therefore, the motivation of this paper is to investigate the relationship between passenger weight and aircraft CG by developing a two-stage stochastic programming model. By reducing the potential deviation of the aircraft's CG caused by the uncertainty of the passenger's weight, we can ensure that the aircraft's CG stays within the safe range.

-

Before a flight takes off, the loadmaster must prepare a load plan to assign passengers and cargo to different sections of the aircraft according to the target CG. Different loads are distributed to various compartments of the aircraft to maintain balance throughout the aircraft. The current method of passenger seat allocation for airlines can be characterized as follows:

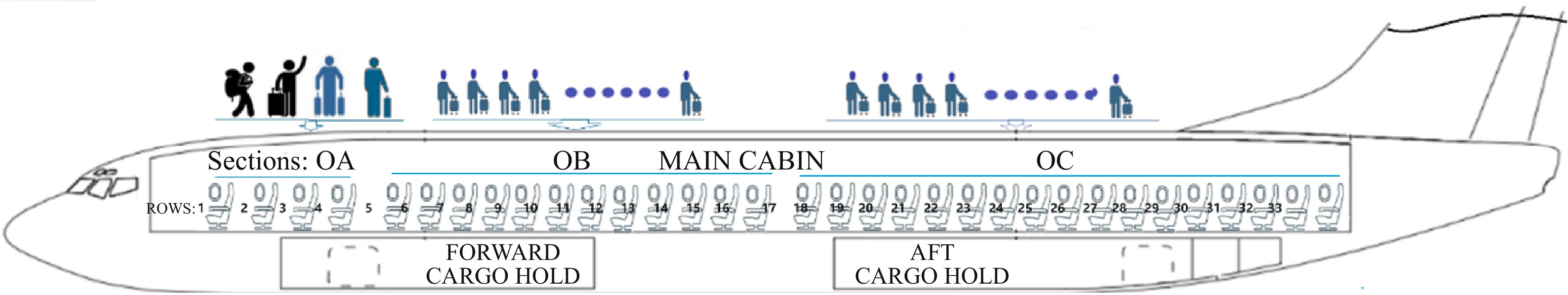

Given an aircraft with S sections in the cabin, and Ns seats available in the section s, and the balance arm of the section s is Bs, s = 1, 2, …, S. Moreover, there are H cargo holds in the aircraft. Bh and Wh denote the balance arm and the maximum loaded weight of the h hold respectively, h = 1, 2, …, H (sections and cargo holds shown as Fig. 1). Supposing that the aircraft will transport R passengers with the standard average body weight W0 (constant), and cargo with total weight Wcargo. Then the problem is to make a decision on the number of passengers to be assigned to each section of the cabin and the amount of cargo to be loaded in each cargo hold, and to minimize the deviation (|BCG − TCG|) between the position of the CG for takeoff (BCG) and the target CG (TCG), while meeting the loading balance constraints of the flight. Aircraft type data are presented in supplementary information: The B737-800 cabin has 29 rows of seats, four seats in the first two rows and six seats in each row behind; there are three divisions, OA, OB, OC; eight seats in OA; 84 seats in OB; and 78 seats in OC. As shown in Supplementary Table S1. The four cargo holds in B737-800 are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Let xs be an integer variable (

$ {\mathbb{N}^ + } $ $ {\mathbb{R}^ + } $ Then the current AWB problem in airlines can be described as:

$ \min \;\left| {{B_{{\text{CG}}}} - {T_{{\text{CG}}}}} \right| $ (1) ${\text{s.t.}}\quad {x_s} \leqslant {N_s}\quad s = 1,2, \cdots ,S $ (2) $ \sum\limits_{s = 1}^S {{x_s}} = R $ (3) $ {y}_{h}\leqslant {W}_{h}\quad h=1,2,\cdots ,H $ (4) $ \sum\limits_{h = 1}^H {{y_h}} {\text{ = }}{W_{{\text{cargo}}}} $ (5) $ \sum\limits_{s = 1}^S {{x_s}} {{\text{W}}_0} + \sum\limits_{h = 1}^H {{y_h}} \leqslant {{\text{W}}_{{\text{MPL}}}} $ (6) $ P_{{\text{FWD}}}^w \leqslant P_{{\text{CG}}}^w \leqslant P_{{\text{AFT}}}^w\quad w \in \left\{ {{W_{{\text{TOW}}}},} \right.\left. {{W_{{\text{ZFW}}}}} \right\} $ (7) $ {x_s} \in {\mathbb{N}^ + }\quad s = 1,2, \cdots ,S $ (8) $ {y}_{h}\in {\mathbb R}^+\quad h=1,2,\cdots ,H $ (9) The objective function (1) minimizes the deviation between the takeoff CG and the target CG, where TCG denotes the target CG position and PGG denotes the takeoff CG. The BCG can be obtained by dividing the total moment acting on the aircraft by the takeoff weight of the aircraft, which is calculated as follows:

$ {B_{{\text{CG}}}} = \dfrac{{\displaystyle\sum\limits_{h{\text{ = 1}}}^H {{B_h}} {y_{\text{h}}} + \sum\limits_{s = 1}^S {{{\text{W}}_{\text{0}}}{B_s}{x_{\text{s}}}} + {{\text{M}}_{{\text{OEW}}}} + {{\text{M}}_f}}}{{{{W} _{\text{OEW}}} + {{\text{W}}_f} + {W_{\text{H}}} + {{\text{W}}_{\text{0}}}R}} $ (10) where, W0 denotes the average standardized weight value of the passengers, which is a fixed value of 75 kg according to Aircraft Weight and Balance Control[26]. MOEW denotes the moment of operation empty weight of the airplane; Mf denotes the moment of the fuel; WOEW denotes the operation empty weight of the airplane; Wf denotes the weight of the loaded fuel. For a specific flight, all the above parameters are constants.

Constraints (2) ensure the assigned number of passengers in each section should be less than its number of seats. Constraints (3) guarantee all passengers have a seat. Constraints (4) confine the loading weight of cargo in a hold should be less than its maximum capacity Wh. Constraints (5) guarantee all planned cargo are loaded. Constraints (6) confine that the total weight of payload, cargo, and passengers, is not more than the aircraft bearing payload weight WMPL. Constraints (7) are the balance constraints. Constraints (8) and (9) limit the range of values of the two decision (xs and yh) variables.

$ B_{{\text{FWD}}}^w $ $ B_{{\text{AFT}}}^w $ $\in $ $ B_{{\text{CG}}}^w $ $ B_{{\text{CG}}}^\omega $ $ B_{{\text{CG}}}^{{\text{ZFW}}} = \dfrac{{\displaystyle\sum\limits_{h{\text{ = 1}}}^H {{B_h}} {y_{\text{h}}} + \sum\limits_{s = 1}^S {{{\text{W}}_{\text{0}}}{B_s}{x_{\text{s}}}} + {{\text{M}}_{{\text{OEW}}}}}}{{{{W} _{\text{OEW}}} + {W_{\text{H}}} + {{\text{W}}_{\text{0}}}R}} $ (11) It has been demonstrated that the airline passenger seat allocation based on sections, as shown above, is more likely to have a larger CG deviation than the row-based method in our previous study[25]. This is because the number of sections of the aircraft cabin is quite small. For example, B737-800 has three sections in the cabin as shown in Fig. 1. It is hard to achieve precise control over the CG. Moreover, the average weight of the passenger's reference, which is 75 kg, is used by airlines which also leads to an increased takeoff CG potential deviation.

Consequently, we reformulate the passenger seat allocation model from section-based to row-based. Simultaneously, adopting passengers' body weights as random variables, a two-stage stochastic programming model for row-based seat allocation for passengers is developed.

-

For the passenger allocation, we take rows to replace sections here, while the cargo holds remain the same with the section-based model. Given an aircraft with N rows in the cabin, and Nr seats available in row r, and the balance arm of the row r is Br, r = 1, 2, …, N. The aircraft will transport R passengers, and their average body weight is a random variable obeying a normal distribution. Let set Ω be the sample space of the random event, where ω

$\in $ Let xr replace xs to denote the number of passengers assigned to the row r. Replace the BCG in the deterministic model objective function (1) with the CG formula (8) as in Eqn (9).

$ \min \;\left| {\dfrac{{{{\text{M}}_{{\text{OEW}}}} + {{\text{M}}_{\text{f}}} + \displaystyle\sum\limits_{{\text{h}} = 1}^M {{B_h}{y_h}} + \sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}W(\omega )} }}{{{{\text{W}}_{{\text{OEW}}}} + {{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}} + {W_{\text{H}}} + W(\omega )R}} - {T_{CG}}} \right| $ (12) It can be reset as:

$\begin{aligned} \min &\Bigg| \displaystyle\sum\limits_{h = 1}^H {{B_h}{y_h}} + {{\text{M}}_{{\text{OEW}}}} + {{\text{M}}_{\text{f}}} - {\text{T}}_{{\text{CG}}}\left( {{{\text{W}}_{{\text{OEW}}}}{\text{ + }}{W_H}{\text{ + }}{{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}}} \right) + \\& \displaystyle\sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {B_r}{x_r}W\left( \omega \right) - {\text{T}}_{{\text{CG}}}W\left( \omega \right)R \Bigg| \end{aligned}$ (13) As MOEW, Mf, WOEW, and Wf are constants when making the AWB plan for a flight, TCG is a given target aircraft CG, and WH is the determined value of total cargo weight for transportation, let C = MOEW + Mf − TCG(WOEW + WH + Wf), the objective function can be rewritten as:

$ \min \;\left| {\sum\limits_{h = 1}^H {{B_h}{y_h}} + \sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}W\left( \omega \right) - {T_{{\text{CG}}}}W\left( \omega \right)R} + {\text{C}}} \right| $ (14) where,

$ \sum\nolimits_{h = 1}^H {{B_h}{y_h}} $ $ \sum\nolimits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}W\left( \omega \right)} $ $ \sum\nolimits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}W\left( \omega \right)} - {T_{{\text{CG}}}}W(\omega )R $ A two-stage stochastic programming formulation is used to model this row-based passenger seat allocation problem with body uncertainty. The first stage decisions to make an a priori plan for cargo allocation. Its model is formulated as:

$ \min \;\left| {\sum\limits_{h = 1}^M {{B_h}{y_h}} + {\text{C}} + {{\rm E}_W}\left[ {Q\left( {y,W(\omega )} \right)} \right]} \right| $ (15) ${\text{s.t.}}\quad {y}_{h}\le {W}_{h}\quad h=1,2,\cdots ,H $ (16) $ \sum\limits_{h = 1}^H {{y_h}} {\text{ = }}{W_{{\text{cargo}}}} $ (17) $ {y}_{h}\in {\mathbb R}^+ \quad h=1,2,\cdots ,H $ (18) where, Q(y,W(ω)) is inertia moment deviation caused by passenger seat allocation in the second stage of the problem, given the tactical plan yh and random variable W(ω). EW[Q(y,W(ω))] denotes the expected solution in the second stage. The objective function (15) minimizes the deviation of the inertia moment of the tactical cargo allocation plan and the expected extra moment deviation added during passengers' seat allocation. Constraints (16) is the maximum weight limit of every cargo hold. Constraints (17) ensure total cargo to be loaded. Constraints (18) impose the positive real number requirements on y.

The second stage determines the number of passengers in each row of seats when the passengers' weight is uncertain.

$ Q\left( {y,W(\omega )} \right) = \min \;\sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}W\left( \omega \right) - {T_{{\text{CG}}}}W\left( \omega \right)R} $ (19) $ {\rm {s.t.}} {x_r} \leqslant {N_r}\quad r = 1,2, \cdots ,{N_r}$ (20) $ \sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{x_r}} = R $ (21) $ \sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{x_r}} W(\omega ) + \sum\limits_{h = 1}^H {{y_h}} \leqslant {{\text{W}}_{{\text{MPL}}}} $ (22) $ B_{{\text{FWD}}}^w \leqslant B_{{\text{CG}}}^w \leqslant B_{{\text{AFT}}}^w\quad w \in \left\{ {{W_{{\text{TOW}}}},} \right.\left. {{W_{{\text{ZFW}}}}} \right\} $ (23) $ B_{{\text{CG}}}^{{\text{TOW}}} = \dfrac{{\displaystyle\sum\limits_{h{\text{ = 1}}}^H {{B_h}} {y_{\text{h}}} + \sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}W(\omega )} + {{\text{M}}_{{\text{OEW}}}} + {{\text{M}}_{\text{f}}}}}{{{{W} _{\text{OEW}}} + {{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}} + {W_{\text{H}}} + W(\omega )R}} $ (24) $ B_{{\text{CG}}}^{{\text{ZFW}}} = \dfrac{{\displaystyle\sum\limits_{h{\text{ = 1}}}^H {{B_h}} {y_{\text{h}}} + \displaystyle\sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}W(\omega )} + {{\text{M}}_{{\text{OEW}}}}}}{{{{W} _{\text{OEW}}} + {W_{\text{H}}} + W(\omega )R}} $ (25) $ {x_r} \in {\mathbb{N}^ + }\quad r = 1,2, \cdots ,N $ (26) The objective function (19) minimizes the deviation between the inertia moment produced by passenger seat allocation and the moment assuming that all passengers are assigned to the given target TCG. Constraints (20) make sure that passengers assigned to row r do not exceed the number of seats. Constraints (21) ensure all passengers be assigned. Constraints (22) are the maximum payload limit. Constraints (23)−(25) are the balance constraints. Constraints (26) impose positive integrality requirements on all second-stage variables.

-

To solve the problem, the first step is to obtain a manageable approximation of the function EW[Q(y,W(ω))]. Sampling is applied to obtain a set of representative scenarios. Assume that there are L possible scenarios for average body weight, the probability that scenario i occurs is Pi, and its value of the passenger's weight is Wi(ω). Let xir replace xr to denote the number of passengers assigned to row r in scenario i with probability Pi. The expected moment deviation associated with the second stage could be approximated.

$ \min \;\left| {\sum\limits_{h = 1}^H {{B_h}{y_h}} + {\text{C}} + \sum\limits_i^L {{P_i}} \left( {\sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}{W_i}\left( \omega \right) - {T_{{\text{CG}}}}{W_i}\left( \omega \right)R} } \right)} \right| $ (27) $ {\text{s.t.}}\quad {y}_{h}\le {W}_{h}\quad h=1,2,\cdots ,H$ (28) $ \sum\limits_{h = 1}^H {{y_h}} {\text{ = }}{W_{{\text{cargo}}}} $ (29) $ {x_r} \leqslant {N_r}\quad r = 1,2, \cdots ,N $ (30) $ \sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{x_r}} = R\quad $ (31) $ \sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{x_r}} {W_i}(\omega ) + \sum\limits_{h = 1}^H {{y_h}} \leqslant {{\text{W}}_{{\text{MPL}}}}\quad i = 1,2, \cdots ,L $ (32) $ B_{{\text{FWD}}}^w \leqslant B_{{\text{CG}}}^w \leqslant B_{{\text{AFT}}}^w\quad w \in \left\{ {{W_{{\text{TOW}}}},} \right.\left. {{W_{{\text{ZFW}}}}} \right\} $ (33) $ B_{{\text{CG}}}^{{\text{TOW}}} = \dfrac{{\displaystyle\sum\limits_{h{\text{ = 1}}}^H {{B_h}} {y_{\text{h}}} + \sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}{W_i}(\omega )} + {{\text{M}}_{{\text{OEW}}}} + {{\text{M}}_{\text{f}}}}}{{{{W} _{\text{OEW}}} + {{\text{W}}_{\text{f}}} + {W_{\text{H}}} + {W_i}(\omega )R}}\quad \quad i = 1,2, \cdots ,L $ (34) $ B_{{\text{CG}}}^{{\text{ZFW}}} = \dfrac{{\displaystyle\sum\limits_{h{\text{ = 1}}}^H {{B_h}} {y_{\text{h}}} + \sum\limits_{r = 1}^N {{B_r}{x_r}{W_i}(\omega )} + {{\text{M}}_{{\text{OEW}}}}}}{{{{W} _{\text{OEW}}} + {W_{\text{H}}} + {W_i}(\omega )R}}\quad \quad i = 1,2, \cdots ,L $ (35) $ {x_r} \in {\mathbb{N}^ + }\quad r = 1,2, \cdots ,N; $ (36) $ {y}_{h}\in {\mathbb R}^+ \quad h=1,2,\cdots ,H $ (37) Basic parameters

-

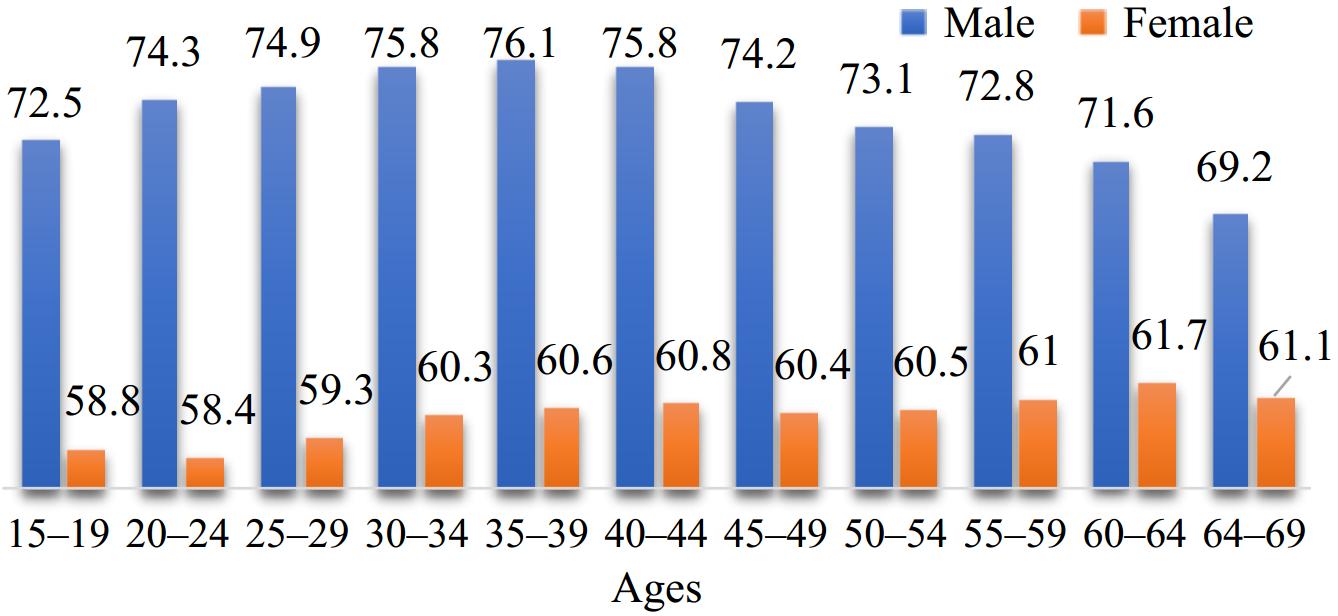

According to Aircraft Weight and Balance Control, 2019[28] and the Report on Health Data on Height and Weight of Chinese Residents in The Fifth National Physical Fitness Monitoring Bulletin[29]) in Fig. 2, setting the average weight of Chinese adults is 75 kg, and the variance is 15 kg. Therefore, W(ω)~N(75, 15) is assumed. The probability shown in Table 1 can be obtained by conducting 10 samplings according to the weight of 71~80 kg in 1 kg unit design.

Figure 2.

Average weight of Chinese adults/kg (data from The Fifth National Physical Fitness Monitoring Bulletin[29]).

Table 1. Traveler weight scenario setting.

Passenger weight Probability Passenger weight Probability 71 0.003 76 0.19 72 0.042 77 0.18 73 0.08 78 0.003 74 0.1 79 0.042 75 0.18 80 0.08 Test scenario design

-

Number of passengers scenario: {130, 140, 150, 160}, four cases.

Cargo scenarios: {5,000, 6,000, 7,000, 8,000}, four cases, yh is taken in 1,000 kg.

Target center of gravity: {20%MAC, 21%MAC, 22%MAC, 23%MAC}, four scenarios.

The center of gravity of an aircraft is usually expressed in balance arm and %MAC. In practice, %MAC is a relative expression of the center of gravity and is more convenient and versatile than the balance arm. It is defined as the ratio of the wing reference distance measured from the leading edge of the Mean Aerodynamic Chord (MAC) to the CG position to the length of the MAC chord. According to the principal equation of center of gravity calculation %MAC and balance arm are converted by Eqn (38).

$ {P_{{\text{CG}}}} = \frac{{({B_{{\text{CG}}}} - {L_{EMAC}})}}{{{L_{MAC}}}} \times 100{\text{%}} $ (38) where, PCG is the %MAC expression of CG; BCG is CG in the form of a force arm; LEMAC is Leading Edge Mean Aerodynamic Chord; LMAC is Mean Aerodynamic Chord.

Therefore, the CG deviation is expressed in terms of %MAC, which can be expressed as:

$ \Delta CG = |{P_{{\text{CG}}}} - {P_{{\text{TCG}}}}| $ (39) where, PTCG is the %MAC expression of TCG.

We consider the comparative analysis of the results with a stochastic model using a classical model (section-based model ) and our previously optimized row-based model[25]. The result is as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Aircraft loading results.

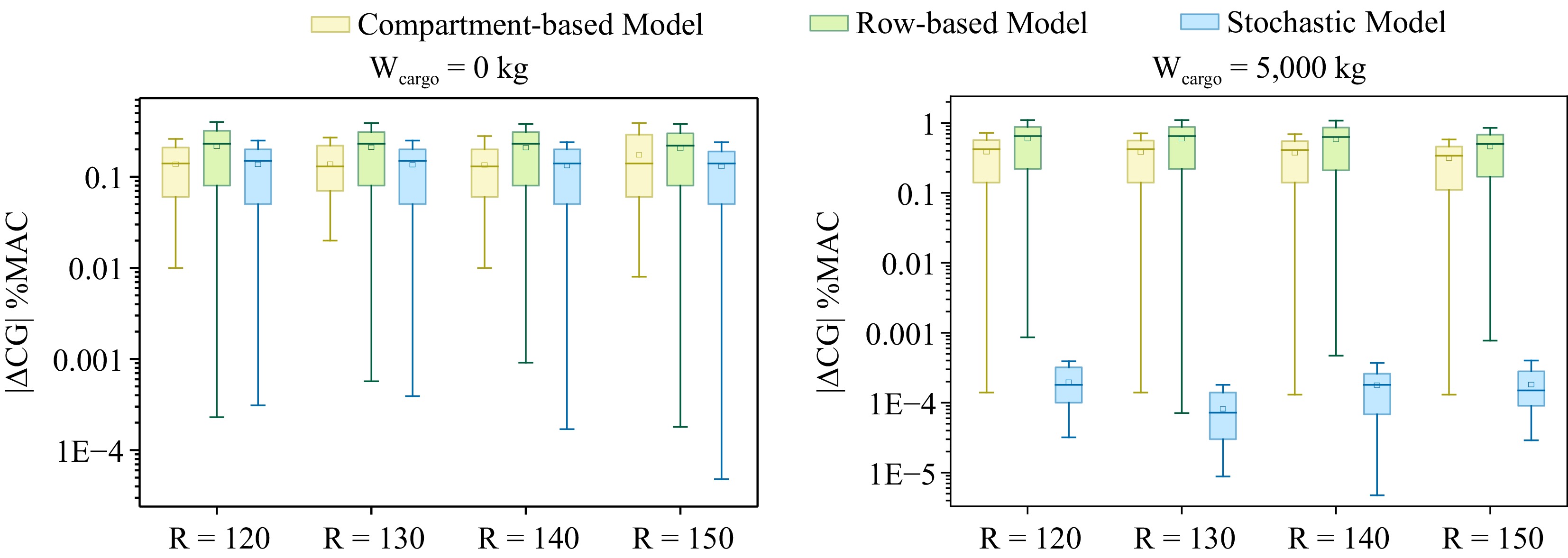

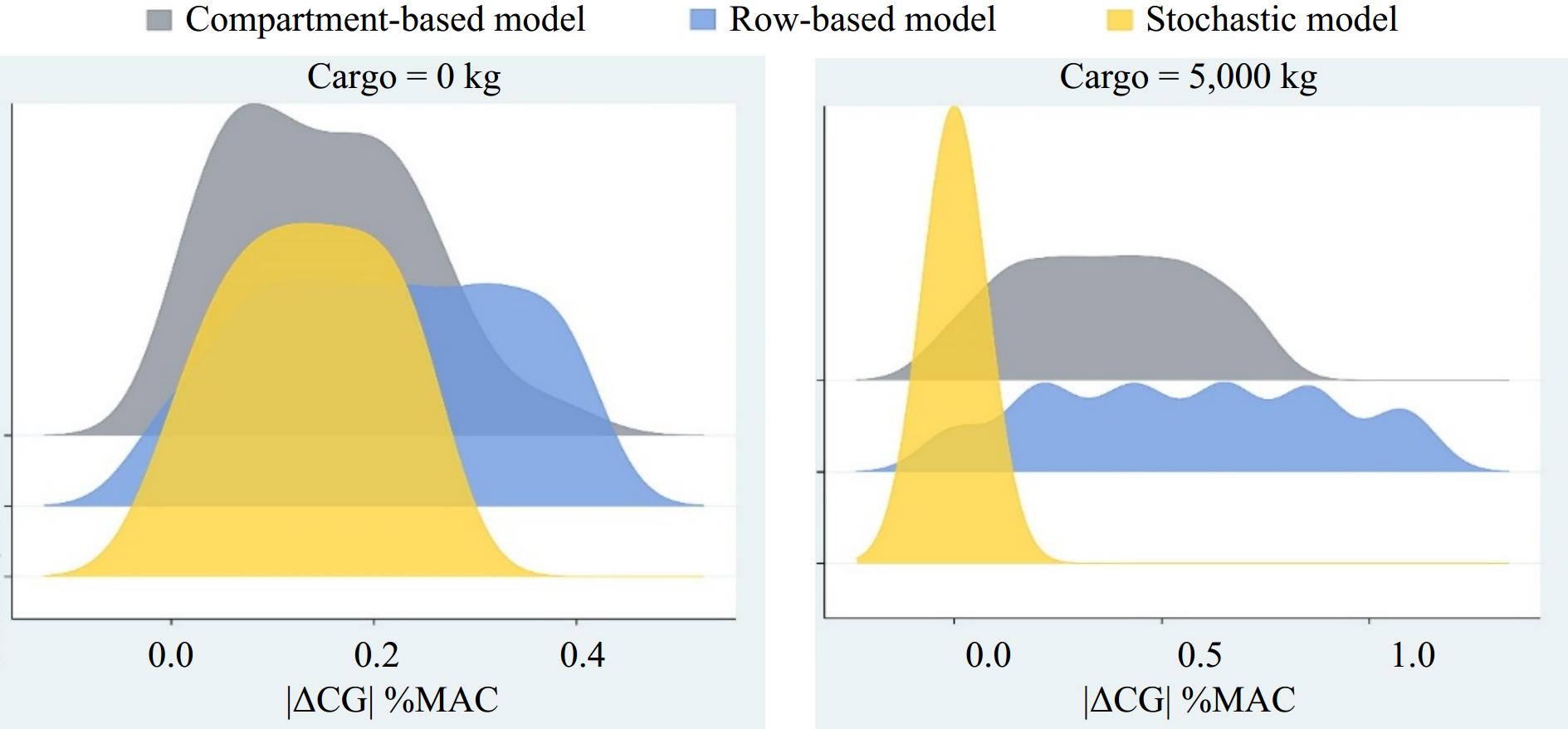

WCargo (kg) R Section-based model Row-based model (E-4) Stochastic model (E-2) TCG 20 21 22 23 20 21 22 23 20 21 22 23 0 130 0.04 0.001 0.03 0.04 1.46 3.65 5.72 0.61 4.48 4.48 7.96 9.70 140 0.10 0.10 0.06 0.05 7.15 6.17 9.07 10.1 4.42 4.42 7.84 9.55 150 2.52 0.96 0.22 0.16 1.40 5.46 1.76 8.98 4.35 4.35 7.73 9.43 160 8.01 6.45 4.89 3.33 4.17 2.89 1.60 0.31 4.30 4.30 7.63 9.29 Section-based model (E-6) Row-based model (E-4) Stochastic model (E-4) 5,000 130 4.20 0.36 0.09 0.54 2.07 4.70 0.71 4.05 1.18 3.95 2.47 6.43 140 4.77 0.75 3.26 0.52 6.25 8.31 4.66 5.71 2.19 3.69 1.42 0.82 150 4.11 0.37 2.12 1.69 4.88 2.73 7.65 9.82 1.29 4.74 3.23 3.62 160 0.28 2.89 1.03 2.76 5.95 6.67 9.05 0.59 3.54 3.08 2.89 6.35 6,000 130 0.33 1.88 0.10 0.56 3.07 2.44 9.04 3.50 0.46 0.56 2.37 1.62 140 0.31 1.45 2.10 0.56 6.69 9.23 6.63 7.88 5.21 1.15 0.56 0.74 150 0.29 5.07 3.33 4.91 6.91 7.48 6.04 9.52 0.57 2.59 1.59 2.36 160 4.00 0.36 1.14 4.78 8.99 0.97 3.97 0.42 5.08 4.00 0.77 1.42 7,000 130 0.34 0.32 3.16 1.63 1.86 6.82 6.71 2.93 1.37 3.31 2.47 3.83 140 3.99 0.75 0.10 0.54 7.99 4.87 6.86 0.33 4.59 2.72 3.71 2.05 150 2.89 0.73 4.36 2.68 7.72 6.75 5.41 4.84 0.29 2.58 1.77 1.84 160 8.4e+5 4.56 2.03 0.50 5.50 3.08 4.59 5.27 2.90 2.72 0.85 3.83 8,000 130 2.88 0.30 0.94 1.59 9.98 8.85 6.49 6.97 26.5 206.5 386.4 565.0 140 4.98 3.49 0.12 2.64 7.39 4.19 5.13 1.77 25.6 204.2 381.3 557.1 150 6.7e+5 1.37 2.20 4.72 6.67 4.62 3.20 2.57 26.1 201.9 376.3 550.7 160 3.8e+5 2.8e+5 1.8e+5 7.5e+5 4.89 2.58 3.45 2.54 25.3 199.7 371.5 544.5 As can be seen from Table 2, Figs 3, and 4, the results of the section-based model and the row-based model are better than the stochastic model, but the section-based model has potential force-arm error and passenger weight error in the real situation, which leads to inconsistency between the actual results and the calculated results. Therefore, we present in Table 3 a back-generation comparison of the actual results of the two models. The addition of cargo has a big influence on the CG of the airplane, so we divided it into the comparison between the CG without cargo and the CG for takeoff.

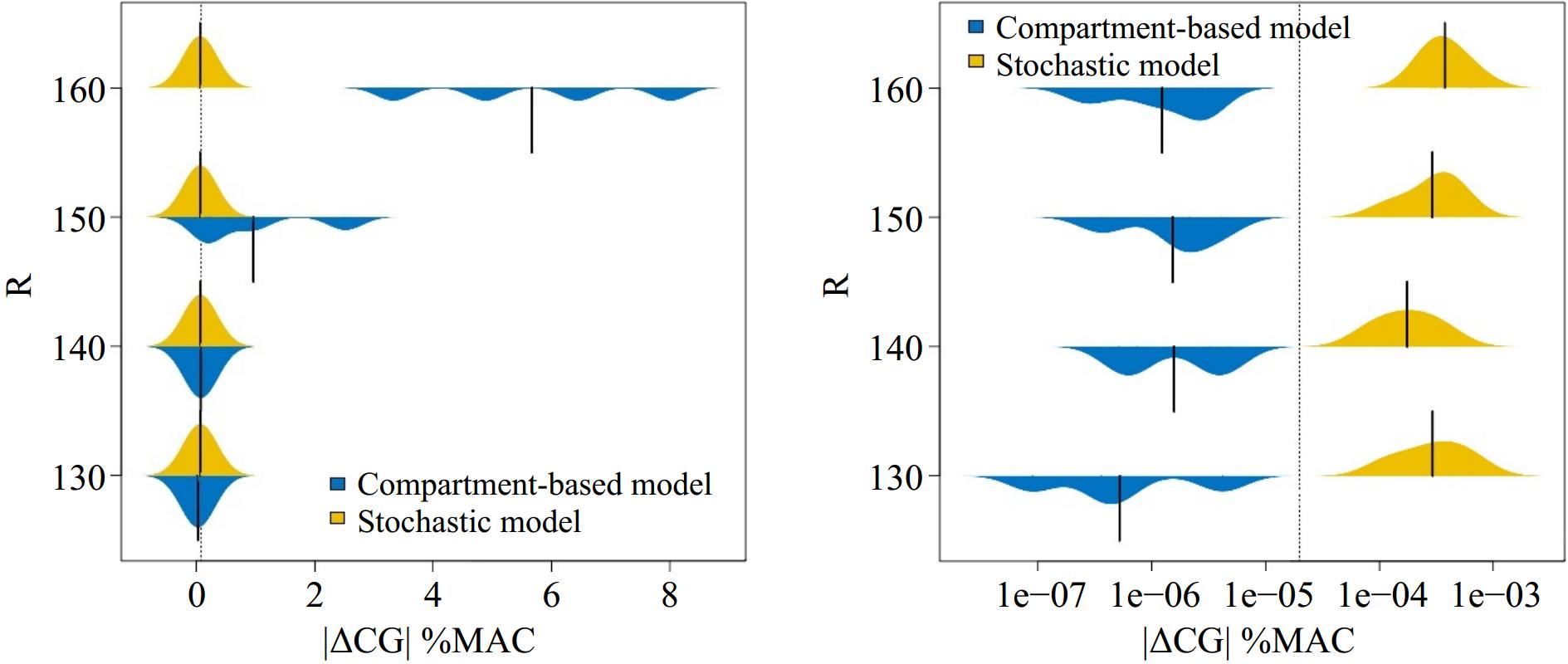

Figure 3.

Comparison of CG deviation between section-based model and stochastic model without cargo (left) and with cargo (right).

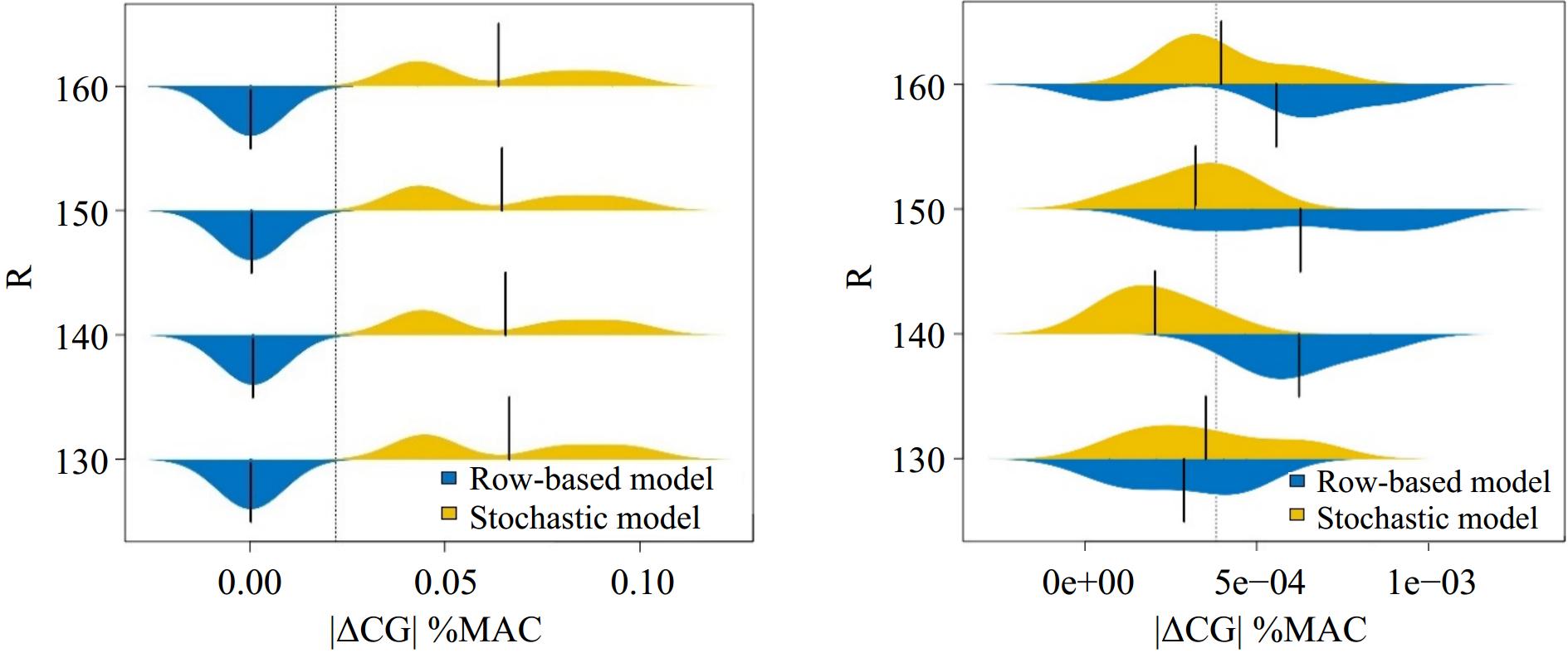

Figure 4.

Comparison of CG deviation between row-based model and stochastic model without cargo (left) and with cargo (right).

Table 3. Test |ΔCG| results of tests with TCG 22%MAC.

Wcargo

(kg)Model Wr R = 120 R = 130 R = 140 R = 150 CB RB SM CB RB SM CB RB SM CB RB SM 0 |ΔCG| 0.02 2.3e-4 0.08 0.03 5.7e-4 0.08 0.06 9.1e-4 0.08 0.22 1.8e-4 0.08 70 0.24 0.40 0.25 0.23 0.39 0.25 0.28 0.38 0.24 0.12 0.38 0.24 71 0.19 0.32 0.20 0.18 0.31 0.20 0.23 0.31 0.20 0.06 0.30 0.19 72 0.14 0.24 0.15 0.13 0.23 0.15 0.18 0.23 0.15 0.01 0.23 0.14 73 0.09 0.16 0.10 0.08 0.15 0.10 0.13 0.15 0.10 0.04 0.15 0.10 74 0.04 0.08 0.05 0.03 0.08 0.05 0.08 0.08 0.05 0.09 0.08 0.05 75 0.02 2.3e-4 3.1e-4 0.03 5.7e-4 3.9e-4 0.06 9.1e-4 1.7e-4 0.22 1.8e-4 4.8e-5 76 0.06 0.08 0.05 0.07 0.08 0.05 0.01 0.08 0.05 0.19 0.07 0.05 77 0.11 0.16 0.10 0.12 0.15 0.10 0.06 0.15 0.10 0.24 0.15 0.10 78 0.16 0.23 0.15 0.17 0.23 0.15 0.11 0.23 0.14 0.29 0.22 0.14 79 0.21 0.31 0.20 0.22 0.31 0.20 0.16 0.30 0.19 0.34 0.30 0.19 80 0.26 0.39 0.25 0.27 0.38 0.24 0.20 0.38 0.24 0.39 0.37 0.23 5,000 |ΔCG| 4.5e-6 8.6e-4 1.2e-4 9.3e-8 7.1e-5 7.4e-5 3.3e-6 4.7e-4 1.1e-4 2.1e-6 7.7e-4 1.2e-4 70 0.72 1.10 3.9e-4 0.71 1.10 3.4e-5 0.69 1.08 2.6e-4 0.58 0.85 4e-4 71 0.57 0.88 3.2e-4 0.56 0.88 1.3e-5 0.55 0.86 2e-4 0.46 0.68 3.4e-4 72 0.43 0.66 2.4e-4 0.42 0.66 8.8e-6 0.41 0.64 1.3e-4 0.35 0.51 2.8e-4 73 0.29 0.44 1.7e-4 0.28 0.44 3.0e-5 0.27 0.43 6.8e-5 0.23 0.34 2.1e-4 74 0.14 0.22 1.0e-4 0.14 0.22 5.1e-5 0.14 0.21 4.7e-6 0.12 0.17 1.5e-4 75 4.5e-6 8.6e-4 3.2e-5 9.3e-8 7.1e-5 7.2e-5 3.3e-6 4.7e-4 5.8e-5 2.1e-6 7.7e-4 9e-5 76 0.14 0.22 3.8e-5 0.14 0.22 9.4e-5 0.14 0.21 1.2e-4 0.11 0.17 2.9e-5 77 0.28 0.43 1.2e-4 0.28 0.43 1.1e-4 0.27 0.42 1.8e-4 0.23 0.33 3.3e-5 78 0.42 0.65 1.8e-4 0.42 0.65 1.4e-4 0.41 0.63 2.5e-4 0.34 0.50 9.4e-5 79 0.56 0.86 2.5e-4 0.55 0.86 1.6e-4 0.54 0.84 3.1e-4 0.45 0.66 1.5e-4 80 0.70 1.08 3.2e-4 0.69 1.07 1.8e-4 0.67 1.05 3.7e-4 0.57 0.83 2.2e-4 The CB is section-based mode. The RB is row-based model. The SM is stochastic model. In Figs 3 and 4 the stochastic model gives poorer optimization results than the other models in the fixed-weight environment, this is because the stochastic model considers the balance of decision-making in multiple environments, taking into account all the environments that may occur. Whereas the other models only consider one situation with a definite weight and ignore the multiple environments at an uncertain weight. To compare the optimization of the model in other environments, we recalculated the results according to the different weight cases, and the results are shown in Table 3.

It can be seen more intuitively from Figs 5 and 6 that the optimization effect of the stochastic model is not outstanding compared to the conventional model when no cargo is added. The reason lies in the fact that not all decisions within the two-stage stochastic model are fully implemented. Even when the passenger allocation outcomes are determined, the resulting optimization impact remains rather limited. For the takeoff CG (after adding cargo) the stochastic model has a significant improvement in optimization, keeping the deviation of the center of gravity in the range of 10−5−10−3 %MAC in all random environments. After the decisions in the first and second stages work simultaneously, the deviation of the aircraft's center of gravity is reduced by the synergistic effect of the optimized solutions for cargo and passenger loading. Besides, the other models are optimized well only at 75 kg, but at other weight environments the optimization declines. Whereas the results of the stochastic planning model are in a good range in all environments.

-

This paper discusses and investigates the passenger weight uncertainty that exists in the current AWB method in passenger flights of airlines. By comparing the data results of the two-stage stochastic model with the others, it is concluded that the two-stage stochastic model not only achieves balanced decision-making between cargo cabin allocation and passenger section allocation in multi-weight environments, but also optimizes the section-based AWB model and the row-based AWB model for other weight environments leading to potential aircraft CG deviation problems, and reduces the flight risk caused by passenger weight uncertainty. In summary, airlines should take passenger weight discrepancies into account when allocating passengers to passenger flights.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, analysis and interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation: Zhao X, Xiao W; data collection: Xiao W. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 B737-800 seat data.

- Supplementary Table S2 B737-800 cargo position data.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao X, Xiao W. 2025. Stochastic programming for seat allocation of passengers with body weight uncertainty in aircraft load optimization. Digital Transportation and Safety 4(2): 133−140 doi: 10.48130/dts-0025-0010

Stochastic programming for seat allocation of passengers with body weight uncertainty in aircraft load optimization

- Received: 29 October 2024

- Revised: 24 January 2025

- Accepted: 18 February 2025

- Published online: 27 June 2025

Abstract: Airlines use a fixed average value of passenger's body weight when making seat allocation plans. Due to the neglect of body weight differences among various passengers, there would be a potential deviation in the aircraft's center of gravity (CG) for a loading balance plan, that could impact flight safety and cost. The uncertainty about body weight is addressed to control the aircraft's CG deviation. The objective is to achieve an optimal CG position and avoid deviations. Computational experiments were conducted on the Boeing B737-800 in multiple body weight scenarios. The experimental findings show that the two-stage stochastic model significantly reduces potential CG deviations caused by passenger weight variations, which is a significant difference from the model used by airlines.