-

Spices are phanerogamic and angiospermic seed-bearing crops cultivated in specific agroclimatic zones. The practice of cultivating spice crops dates back to the Indus Valley Civilization and the Mesopotamian Valley Civilization around 9000 BCE[1]. Farmer communities in countries such as India, Türkiye, Bangladesh, China, Indonesia, Pakistan, Ethiopia, Nepal, Colombia, and Myanmar are actively involved in the cultivation and management of these crops. Indian farmers contribute approximately 75% of the global production and supply of spices[2]. In India, a wide variety of spice crops, including Piper nigrum, Elettaria cardamomum, Cinnamomum verum, Zingiber officinale, Curcuma longa, Syzgium aromaticum, Myristica sp., Vanilla, Crocus sativus, and Allium sativum, are successfully grown across diverse agroecological zones[3]. Various parts of these plants—such as roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits—are processed into culinary powders, medicinal syrups, pastes, cosmetics, and disinfectants.

Spice crops contain bioactive phytochemicals such as polyphenols and flavonoids, which provide numerous health benefits, including anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, neuroprotective, antimicrobial, anti-diabetic, antioxidant, antiviral, and cardioprotective properties[4]. P. nigrum contributes to 13% of the daily recommended intake of manganese and 3% of vitamin K, essential for bone health, wound healing, and immune function. E. cardamomum offers anti-cancer, anti-ulcer, and anti-inflammatory benefits while promoting the release of natural antioxidants[5]. C. verum supports immune function, digestion, and circulation, helping regulate blood pressure and heart rate. Z. officinale aids in alleviating nausea, motion sickness, constipation, and osteoarthritis while supporting cardiovascular and immune health[6]. C. longa helps manage osteoarthritis, fever, depression, liver diseases, and high cholesterol. It provides curcumin, omega-3 fatty acids, and essential vitamins, reducing the risk of chronic diseases[7]. S. aromaticum contains eugenol, which alleviates pain and fights infections, aiding in dental health and digestion[8]. Myristica sp. possesses antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and liver-protective properties, helping with joint pain and inflammation[9]. Vanilla sp. is beneficial for fever, spasms, blood clotting issues, and gastrointestinal distress[10]. C. sativus supports cardiovascular health, reduces inflammation, and helps manage depression[11]. Allium sativum is known for its ability to lower blood pressure, prevent atherosclerosis, and reduce serum cholesterol. It enhances fibrinolytic activity and possesses antimicrobial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory properties[12]. Additionally, garlic may aid in the management of Alzheimer's, dementia, and arthritis. Regular consumption of these spices can significantly contribute to overall well-being by reducing the risk of chronic diseases and promoting a healthy immune system[13].

The overexploitation of spice crops during post-harvest processing has mitigated the effectiveness of vegetative propagating and seed materials[14]. The recalcitrant nature of seed germplasm in spice crops—characterized by high water content, susceptibility to desiccation, microbial invasion, and short lifespan—has further weakened seed viability[15]. Juvenile or immature vegetative propagating planting materials are often vulnerable to insect-pest invasions and abiotic stress responses, which can impact their growth and development[16]. The over-extraction and formulation of economic products, such as powdered spices and medicinal drugs, have led to a decline in the diversity of spice crops. Climatic variations, including changes in temperature, light, and wind, as well as factors like non-uniform light radiation, life cycle stages, and floral initiation, collectively influence the growth (including fruit ripening), production, and yield of spice crops[17,18]. Excessive use of agrochemicals can introduce heavy metals and xenobiotic compounds into the soil, which slow down the morphological and physiological maturity of the crops[19]. The invasion of resistant insects and microbes can cause necrosis and blight in the phenotypic parts of the crops. Additionally, high light intensity and the carbon dioxide compensation point can inhibit biochemical synthesis, pulp formation, and other physiological responses in spice crops[20]. The accumulation of heavy metals and xenobiotics in the morphological parts and fruit pulp of spice crops can lead to the presence of toxic chemicals, further affecting their quality and safety[21].

The integration of multi-omics resources such as gene transfer methods or the CRISPR/Cas system, alongside technologies like plant tissue culture, soilless culture, and speed breeding techniques has proven to be highly effective in advancing the improvement of spice crops[22]. The direct and indirect gene transfer methods as well as CRISPR/Cas systems and plant tissue culture techniques have successfully facilitated the transformed/non-chimeric plant regeneration for fulfilling the phenotypic improvements, population lines development, and biotic and abiotic stress tolerance in spice crops[23]. The comprehensive use of soilless culture and plant tissue culture techniques has effectively supported plant regeneration, the generation of population lines, and the prevention of tissue culture-induced plant loss in spice crops under a controlled environmental ecosystem[24]. The combined application of soilless culture or speed breeding techniques with gene transfer methods, CRISPR/Cas systems, and plant tissue culture techniques has efficiently led to non-chimeric plant regeneration, phenotypic improvements, population line advancement, and increased resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses in spice crops within advanced controlled environment ecosystems[25]. Plant tissue culture techniques such as cell culture, suspension culture, Bergmann plating technique, raft nurse tissue paper, seed culture, embryo culture, endosperm culture, ovary culture, ovule culture, anther culture, protoplast culture/somatic hybridization, and somaclonal variation are commonly used for the virus- and disease-free regeneration of spice crops[26]. These methods are often combined with direct or indirect gene manipulation techniques, including the CRISPR/Cas system, to develop crops with enhanced resistance to both biotic and abiotic stresses[27]. The integration of plant tissue culture methods with gene manipulation techniques has led to the generation of biofortified population lines, resistant population lines, and other specialized crop variants in spice crops[28]. These approaches also contribute to the creation of climate-adapted, uniform, or distinct phenotypic and genotypic profiles in spice crops[29]. Furthermore, plant tissue culture and gene transfer techniques, including CRISPR/Cas, are being integrated with soilless culture methods to develop regenerated plant populations in controlled environmental ecosystems[30]. Extensive research has been conducted on various species of spice crops, with a focus on integrating gene transfer and plant regeneration techniques to improve population lines, variety development, and trait enhancement. This review article highlights innovative approaches integrating plant tissue culture, genetic transformation, soilless culture, and speed breeding techniques to enhance plant regeneration, trait improvement, and variety development in spice crops.

-

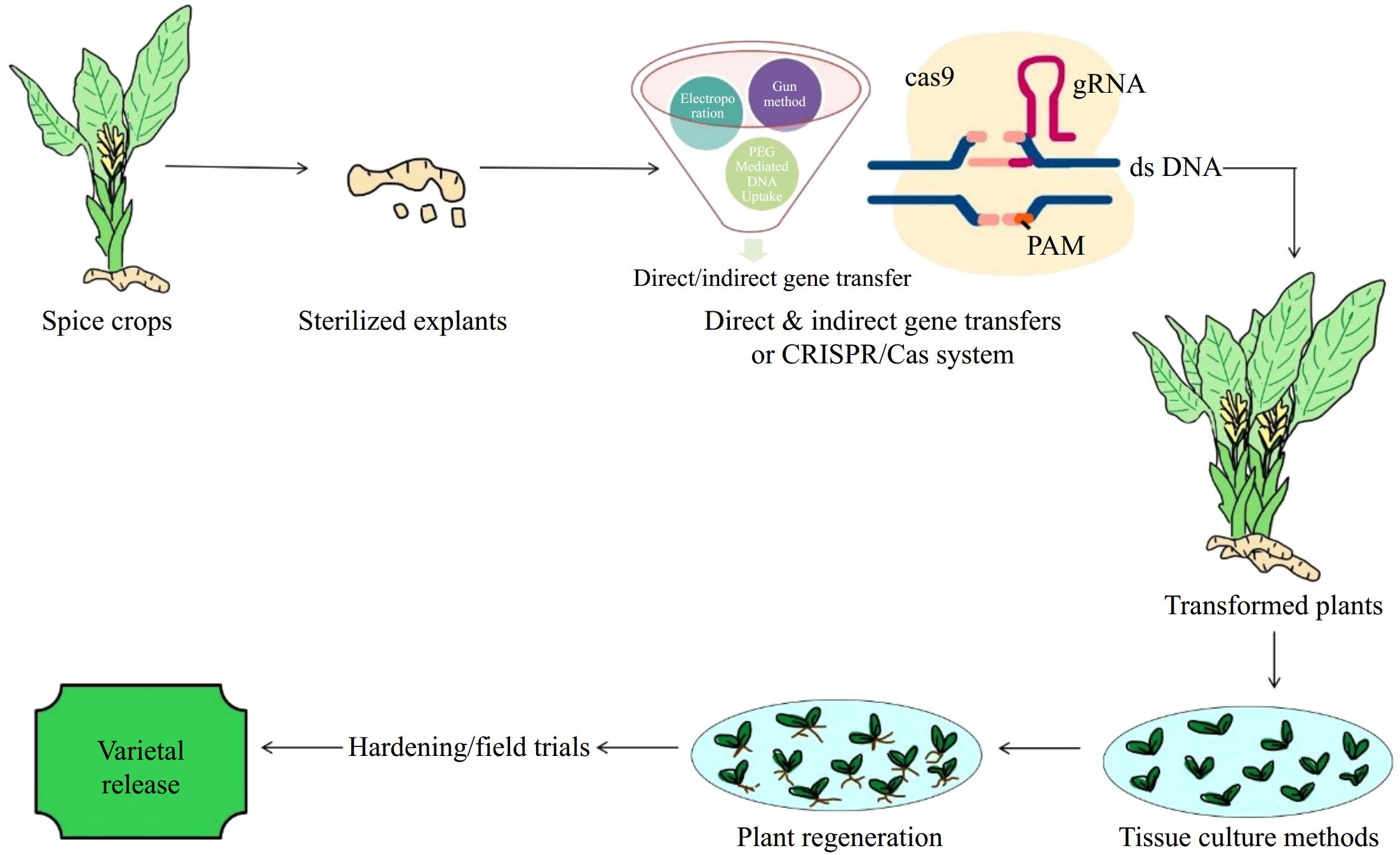

The sterilized morphological parts of spice crops, including root cells, shoot cells, leaf cells, flower cells, anthers, seeds, embryos, endosperms, ovaries, ovules, protoplasts, apical tips, axillary buds, and nodes, are subjected to genetic transformation using direct or indirect genetic engineering methods or the CRISPR/Cas system in isolated chamber systems[31]. The transformed plant parts are then inoculated onto various media, such as Murashige and Skoog (MS) media, N6 media, Gamborg (B5) media, Nitsch-Nitsch media, Driver and Kuniyuki Walnut (DKW) media, Woody Plant Media (WPM), and Schenk and Hildebrandt (SH) media, which contain appropriate concentrations of auxins. Under controlled culture conditions, callus induction is typically observed within 3 to 8 weeks[32]. The callus-derived plant parts are then transferred to media with specific concentrations of auxins and cytokinins, either combined or alone, to induce shoot regeneration, a process that generally takes 3 to 8 weeks[33]. The responding shootlets are subsequently placed in 1/2 strength MS media, N6 media, B5 media, Nitsch-Nitsch media, DKW media, WPM, or SH media containing auxins for root regeneration, which typically occurs within 2 to 6 weeks[34]. Afterward, the tissue-cultured plant lines are adapted and acclimatized in nutrient-rich growing systems under protected cultivation conditions. These regenerated plant populations are then grown in open environmental conditions to complete biological growth, as well as the development of population lines or varieties[35].

The unique and modified chemical compositions of organized media have significant potential to enhance plant regeneration within a shorter generation time[36]. Key factors such as the selection of appropriate explants, the chemical composition of the media, stable concentrations of auxins, cytokinins, and organic supplements, as well as the maintenance of standardized controlled conditions, play a crucial role in overcoming recalcitrant traits. These factors also promote improved plant regeneration and the synthesis of secondary metabolites in spice crops under controlled environment systems[37] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Prototype of gene transfers and plant regeneration in spice crops (CRISPR: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats; Cas: associated protein; gRNA: guide ribonucleic acid; ds DNA: doubled stranded deoxy ribonucleic acid; PAM: protospacer adjacent motif/short DNA sequence).

-

Molecular tools, including direct or indirect genetic engineering methods and the CRISPR/Cas system, combined with plant tissue culture techniques, have proven to be effective in promoting plant regeneration in spice crops[38]. Healthy and uniform external plant parts of spice crops are capable of achieving high rates of regeneration through the application of genetic engineering or CRISPR/Cas technologies, in conjunction with plant tissue culture methods[39]. Countries with favorable agroclimatic conditions and rich vegetation have successfully induced tissue-cultured plant regeneration in various spice crops, such as C. verum, Cuminum cyminum, E. cardamomum, C. longa, P. nigrum, Vanilla sp., S. aromaticum, Z. officinale, Myristica, C. sativus, and A. sativum, using direct or indirect gene transfer methods or the CRISPR/Cas system[40]. The use of distinct and stable organized media, appropriate concentrations of plant growth regulators, and controlled environmental conditions has enabled the successful development of transformed plants with accelerated regeneration cycles[41]. The use of plant tissue culture methods such as organogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, anther culture, and gene transfer techniques including direct gene transfer via gene gun/biolistic gun/particle bombardment or indirect gene transfer via Agrobacterium-mediated methods has proven effective in achieving transformed gene/non-chimeric plant regeneration within a short generation time in spice crops[42]. Additionally, the plant tissue culture technique of synthetic seed production has successfully facilitated the synthesis of artificial seeds in a relatively short period for spice crops[43].

The integration of CRISPR/Cas technology with tissue culture has opened new avenues for precise genome editing in spice crops, enabling targeted trait modifications such as disease resistance, enhanced phytochemical content, and improved post-harvest stability[44]. Significant progress has been made in developing transformation protocols for spice crops, particularly in species like Capsicum annuum, where Agrobacterium-mediated transformation combined with CRISPR/Cas9 has been successfully employed to edit genes related to pungency and fungal resistance[45]. Similarly, in C. longa and P. nigrum, researchers have explored protoplast-based CRISPR delivery systems to bypass the challenges associated with conventional transformation. The advancements in callus induction, somatic embryogenesis, and regeneration techniques have improved the feasibility of genome editing in some recalcitrant spice crops[46]. Additionally, the use of transient expression systems has allowed researchers to introduce CRISPR components without stable transformation, thereby reducing regulatory concerns associated with transgenic modifications[47]. The current application of plant tissue culture techniques, along with direct or indirect genetic engineering and the CRISPR/Cas system, has proven highly effective in developing plant populations resistant to biotic and abiotic stresses, as well as biofortified population lines in spice crops[22]. The integration of soilless culture with genetic modification methods, including direct or indirect gene transfer or the CRISPR/Cas system, has efficiently led to the production of genetically modified, tissue-cultured plant regenerations in spice crops under controlled environmental conditions[48]. Combining soilless culture and speed breeding techniques with plant tissue culture methods and gene transfer technologies has resulted in the successful development of biotic and abiotic stress-resistant, biofortified plant populations, as well as advancements in variety or seed development within controlled ecosystems[49]. Further research is needed to facilitate tissue-cultured plant regeneration in additional spice crops using plant tissue culture techniques and genetic engineering tools like CRISPR/Cas. This research should also focus on developing biotic and abiotic stress-resistant plants, biofortified population lines, climate-adapted varieties, and enhanced seed development through the integration of soilless culture and speed breeding techniques within controlled environmental systems. Investigations should aim to demonstrate transformed plant regenerations in spice crops by combining soilless culture, speed breeding, plant tissue culture methods, and genetic engineering tools, including CRISPR/Cas.

Despite significant advancements in CRISPR/Cas technology and tissue culture techniques, several knowledge gaps remain that hinder its effective application in spice crops[50]. One major gap is the lack of well-annotated reference genomes for many spice crops, making it challenging to design precise guide RNAs (gRNAs) for targeted gene editing. While some progress has been made in sequencing genomes of crops like C. annuum and P. nigrum, other economically important spices such as C. longa and Z. officinale have incomplete or poorly annotated genomic datasets[51]. Without comprehensive genomic resources, identifying functionally relevant genes, predicting off-target effects, and validating gene edits remain difficult[52]. Additionally, limited transcriptomic and epigenomic data for spice crops further restricts the understanding of gene regulatory networks, which is crucial for developing precise genome-editing strategies[53]. Another critical knowledge gap lies in the low transformation and regeneration efficiency of spice crops, which limits the successful application of CRISPR/Cas systems[54]. Many spice crops are recalcitrant to tissue culture due to their slow growth, high polyphenolic content, and susceptibility to oxidative stress during in vitro conditions[55]. While somatic embryogenesis and organogenesis protocols exist for some species, their efficiency is highly variable, and regeneration rates remain low[56]. Moreover, the mechanisms underlying recalcitrance and regeneration potential in spice crops are not well understood, making it difficult to develop universally applicable tissue culture protocols[57]. The role of hormonal regulation, epigenetic modifications, and stress responses in regeneration needs further exploration to enhance tissue culture-based CRISPR applications[58]. Additionally, there is a lack of research on alternative gene delivery methods such as nanoparticle-mediated or viral vector-based CRISPR systems, which could offer viable solutions for difficult-to-transform species[59,60]. Addressing these knowledge gaps through integrative studies involving genomics, transcriptomics, and innovative transformation technologies will be essential for unlocking the full potential of CRISPR/Cas in spice crop improvement (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Table 1. Integration of gene transformations and plant tissue culture techniques in plant regenerations in spice crops with medical importance.

S. No. Spices Medicinal importance Country Media + growth regulator levels Tissue culture methods Explants Callus induction, shoot regeneration, and root regeneration

(d: days, w: weeks)Transformation methods Regeneration and transformation efficiency Ref. 1 Nigella sativa Reduce blood pressure, cholesterol, triglyceride levels, improve insulin sensitivity and pancreatic beta cell function Iraq Hairy root: MS + 200/300/100 mg/L cefotaxime Hairy Root Culture Seeds NA, NA, 20−25 d Agrobacterium rhizogenes +

x-gluc + 35s33% of hairy root induction with 4.2 hairy roots/segment; 6.31 mg/g thymoquinone content in hairy roots which was higher compared to seed (4.19 mg/g) and normal seedlings (1.27 mg/g) [80] 2 Piper nigrum L. Regulate blood pressure, lower cholesterol levels, anticancer potential, neuroprotective effects, promotes fat burning and weight loss, regulates blood sugar levels India Callus: SM media + 1.5% sucrose + 100 μg/L cefotaxime + 25 μg/L kanamycin Direct somatic embryogenesis Mature Seeds 3−5 w, 4 w, NA Agrobacterium mediated + PCR

+ RAPDAverage of 9 hardened putative transgenic plantlets per gram of embryonic mass; Dot blot confirmed NPT II gene presence in 62 of 74 putative transformants. Southern analysis confirmed stable NPT II integration in six of 17 screened transformants [81] 3 India Callus + plant regeneration: MS + kinetin + NAA; shoot: MS + 1 mg/L IAA / 1 mg/L IBA; root: MS + 0.2 mg/L NAA Organogenesis + somatic embryogenesis Shoot tips, nodes, leaf NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 4 India Sterile water + 5% alginate Synthetic seeds Shoot buds NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 5 Elethania cardamomum Matra. Blood sugar regulation, neuroprotective effects, metabolic and weight management, aphrodisiac and hormonal balance India MS + 1 mg/L BAP + 0.5 mg/L IBA + 5% alginate Synthetic beeds Callus NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 6 Cinnamomum verum Persl. Regulation of blood pressure and heart rate India Shoot: MS + 0.5 mg/L NAA / 0.5 mg/L BAP Organogenesis Shoot tips NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 7 Cinnamomum verum Persl. Regulation of blood pressure and heart rate India MS + 3 mg/L BAP + 0.5 mg/L kinetin Synthetic seeds Shoot buds NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 8 Syzgium aromaticum L., Merr. & L. M. Perry For digestive health, antinfallmatory effects India Shoot: MS + 0.5 mg/L NAA / 0.5 mg/L BAP Organogenesis Shoot tips NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 9 Zingiber officinale Roscoe Treating nausea, motion sickness, constipation, and osteoarthritis, etc. India Haploid lines + callus- MS + 2−3 mg/L 2,4-D; plant regeneration: MS + 10 mg/L BA / 0.2 mg/L 2,4-D Anther culture Anthers - uninucleate stage NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 10 Shoot: MS + 4 mg/L BA Organogenesis Rhizome buds NA, 5 w, NA − NA [82] 11 MS + 1 mg/L BAP + 5% alginate Synthetic seeds Somatic embryo NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 12 Myristica fragrans Sedative and sleep aid, antimicrobial properties, cognitive support, digestive health, anti-inflammatory effects, etc India Shoot: WPM + 3 mg/L BAP / 1 mg/L kinetin Organogenesis Shoot tips NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 13 Curcuma longa L.) Management of osteoarthritis, fever, depression, liver diseases, and high cholesterol India Callus + shoot: MS + 10% coconut milk + 2.5 mg/L BAP Organogenesis Vegetative buds NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 14 C. longa L. Management of osteoarthritis, fever, depression, liver diseases, and high cholesterol India MS + 1 mg/L BAP + 0.5 mg/L IBA + 5% alginate Synthetic seeds Adventitious buds NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 15 Vanilla planifolia Jacks. For fever, spasms, blood clotting issues, and gastrointestinal distress India Plant regeneration: MS + 0.5 mg/L IBA Secondary metabolites-MS +

0.1 mg/L 2,4-D / 0.5 mg/L kinetin / 1 mg/L IBASomatic embryogenesis, suspension culure Aerial root NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 16 Vanilla planifolia Jacks. For fever, spasms, blood clotting issues, and gastrointestinal distress India Sterile water + 5% alginate Synthetic beeds Shoot buds NA, NA, NA − NA [82] 17 Camphor Cinnamomum camphora L. J. Persl., Cinnamomum verum Diagnosis in resuscitation, heat clearance, pain relief, fever, convulsions, stroke, sputum fainting, sputum coma, laryngeal pain, mouth pain, anthrax, bloodshot eye Mauritius Callus: MS + 1 mg/L BAP + 0.005-5 mg/L TDZ; Shoot: MS + 1 mg/L BAP + 2.5 mg/L TDZ Organogenesis Shoot tips, leaf 4 w, 6−8 w, 2 w − C. verum explants: Responded by sprouting. Rooting: 100% shoots rooted within two weeks on basic MS medium No Agrobacterium-mediated transformation was performed, so transformation efficiency is not applicable in this study [83] 18 Cumin Cuminum cyminum L. Reduce blood pressure, cholesterol, triglyceride levels, improve insulin sensitivity, and pancreatic beta cell function India Callus + shoot: B5 media + 2 μM BA + 0.5 μM NAA Indirect organogenesis Seeds-embryo NA, 29 d, NA Agrobacterium mediated + GFP + RT-PCR; gene gun method + GFP

+ RT-PCRExplants showed highest regeneration and transformation efficiency at 0.5 OD600 with 24 h co-cultivation, compared to other OD and time combinations. [84] 19 Zingiber officinale Roscoe Treating nausea, motion sickness, constipation, and osteoarthritis, etc. India Callus: B5 media + 2 μM BA + 0.5 μM NAA Organogenesis Seed- embryo NA, NA, NA Agrobacterium mediated + GFP + PCR Gene gun + PCR Regeneration efficiency of transformed explants was highest (96.2%) on 0.4 M sorbitol-containing media, with the lowest browning rate (4.07%) compared to 0.2 and 0.6 M sorbitol. The transformed cumin embryos showed 51.93% regeneration efficiency [84] 20 Cuminum cyminum L. Reduce blood pressyre, cholesterol, triglyceride levels, improve insulin sensitivity and pancreatic beta cell function Iran Direct somatic embryogenesis: B5 media + 1/10 μM TDZ Indirect somatic embryogenesis: callus: B5 media + 0.1−0.4 mg/L / 1 mg/L BAP + 0.2/0.4 mg/L NAA; shoot: MS + 0.4 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA, MS + 1 mg/L BAP + 0.1 mg/L NAA Direct ir Indirect somatic embryogenesis Mature seeds 14 d, 5 w, NA − Direct regeneration was highest (57.5%) at 10 μM TDZ and lowest (6.67%) at 1 μM, while indirect regeneration peaked (25.83%) with 0.1 mg/L NAA + 0.4 mg/L BAP; Shahdad and Afghanistan accessions showed superior response. [85] 21 Elethania cardamomum Matra. Blood sugar regulation, neuroprotective effects, metabolic and weight management, aphrodisiac and hormonal balance India Callus: MS + 9 μM 2,4-D / 2−3 μM kinetin − Rhizome 4−8 w, NA, NA Agrobacterium mediated + PCR + southern blot + dot blot No specific transformation or regeneration efficiency data [86] 22 E. cardamomum Matra. Blood sugar regulation, neuroprotective effects, metabolic and weight management, aphrodisiac and hormonal balance India Shoot: MS + 1 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L kinetin / 0.2 mg/L IAA / 0.1 mg/L calcium panthothenate + 5% cocnut milk Organogenesis Vegetative buds NA, NA, NA − NA [87,88] 23 Cinnamomum verum Persl. Regulation of blood pressure and heart rate Sri Lanka Shoot: ½MS + 1.5 mg/L BAP + 0.2 mg/L IAA; root: ½MS 0.1 mg/L NAA + 4 mg/L BAP Organogenesis Axillary buds NA, 14 d, 6 w − Stem elongation: 19.5 mm after 14 d; leaf initiation: 2.06 leaves/plantlet after 14 d; root length: 6.7 cm after 6 w (on full MS + 0.1 mg/L NAA + 4.0 mg/L BAP + 1 g/L activated charcoal) [89] 24 Syzgium aromaticum L., Merr. & L. M. Perry For digestive health, antinfallmatory effects India Shoot: ½MS salts + B5 media + 3 mg/L BAP / 0.5 mg/L NAA Organogenesis Nodes, shoot tips NA, 4−5 w, NA − 6−8 shoots were obtained when 3 mg/L BAP and 0.5 mg/L NAA used in medium. Furthermore, 1−3 mg/L BAP and 0.1 mg/L NAA proved most effective for promotion of shoot proliferation. [90] 25 Syzgium aromaticum L., Merr. & L. M. Perry For dental health, digestive aid, antimicrobial properties, blood sugar regulation, liver protection, aphrodisiac and reproductive health New Zealand Plant regeneration: white and voisey (CR) media + MS salts + B5 vitamins + 1 mg/L BAP + 1 mg/L NAA; root: white and voisey (CR) media + hormone free − Seeds NA, 4 w, 2−3 w Agrobacterium mediated + GUS

+ PCRNA [91] 26 Zingiber officinale Roscoe Treating nausea, motion sickness, constipation, and osteoarthritis, etc. India MS + 1 mg/L BAP/ 2 mg/L BAP; MS + 1 mg/L BAP + 0.5 mg/L NAA; MS + 1 mg/L BAP + 1 mg/L NAA; MS + 2 mg/L BAP + 1 mg/L NAA; MS + 3 mg/L BAP + 1 mg/L NAA Direct organogenesis AerialaStem- axillary meristem, apical meristem NA, 2 w, 2 w − 85% of plantlets were successfully hardened and established in the field, with 95% success from basal (axillary meristem) and 70% from middle (apical meristem) stem explants. [92−94] 27 India Callus: MS + 9−22.6 μM 2,4-D; shoot: 0.9 μM 2,4-D + 44.4 μM BA; root: MS + 5.4 μM NAA Indirect organogenesis Aerial shoot, young leaf 4 w, 4 w, 5 w − Organogenesis and regeneration occurred at 11.9 μM 2,4-D + 44.4 μM BA with 80% soil establishment; transformation efficiency not reported. [95] 28 Myristica fragrans Sedative and sleep aid, antimicrobial properties, cognitive support, digestive health, anti-inflammatory effects, etc. India Callus: WPM + 1 mg/L BA + 1 mg/L NAA Indirect organogenesis Matured unopened fruits NA, NA, NA − [95] 29 Z. officinale Roscoe Treating nausea, motion sickness, constipation, and osteoarthritis, etc. India − − − NA, NA, NA Agrobacterium mediated + GUS

+ PCRThe regeneration of hygromycin-resistant plantlets was confirmed, it does not include detailed regeneration efficiency [96] 30 Z. officinale Roscoe Treating nausea, motion sickness, constipation, and osteoarthritis, etc. India Shoot: ½MS + 1−10 mg/L 2,4-D / 3 mg/L BA Organogenesis Shoot buds. leaf discs, pseudostem 2−4 w, NA, NA Agrobacterium mediated + GUS

+ PCRUsing young bud as explant, transformation frequency ranged from 1.1% to 2.2%, with slow callus growth under antibiotic selection [97] 31 Allium sativum L. Management of heart health, immune boosting, digestive health, bone health, aphrodisiac amd reproductive health Korea, Croatia Callus: MS + 2 mg/L 2,4-D; shoot: MS + 0.1 mg/L BAP Indirect organogenesis Shoot tips 4 w, 14 w, NA − Regeneration declined with callus age, but healthy plantlets were obtained from callus up to 16 months old across all clones. [98,99] 32 Mexico, Turkey Callus: MS + 2.2−4.5 μM 2,4-D, MS + 2.2−4.5 μM 2,4-D + 2.2−4.6 μM kinetin; Shoot: MS + 4.4 μM kinetin Indirect organogenesis, root tip culture Root tips 8 w, 3−6 w, NA − Regeneration data showed a high efficiency—up to 170 plantlets per gram fresh weight (FW) of callus—when cultured on MS medium with 4.6 μM kinetin + 4.5 μM 2,4-D. [100,101] 33 Crocus sativus L. For cardiovascular health management, reduction in inflammation, and helps manage depression India Callus: MS + 0.5 mg/L 2,4-D + 1 mg/L BAP + 1 mg/L IAA; plant regeneration: 0.5 mg/L TDZ +1 mg/L IAA + 0.1 g/L activated charcoal Indirect somatic embryogenesis Corm slice 3−4 w, 4 w, NA Agrobacterium mediated + PCR

+ southern blot4% transformation efficiency with Agrobacterium, > 70% callus induction, and cormlet regeneration in 8 w using TDZ + IAA + activated charcoal [102] 34 Japan, India Callus: 2 μM BA + 2 μM NAA + 40, 60 g/L table sugar; root: 8.8 μM IBA + 40 g/L table sugar − Corms 8 w, NA, 12 w − Cormlet regeneration: 70.0 ± 0.30 cormlets per corm slice on ½ MS + TDZ (20 μM) + IAA (10 μM) + sucrose (40 g/L) Cormlet germination: 90% on MS + BAP (20 μM) + NAA (15 μM) Cormlet enlargement: Up to 2.5 g on MS + TDZ (15 μM) + IAA (12.5 μM) + sucrose (30 g/L) Flowering: 25% of 2.5 g cormlets flowered under greenhouse conditions [103−105] 35 Curcuma longa L., Curcuma mangga valeton & zijp Management of osteoarthritis, fever, depression, liver diseases, and high cholesterol Thailand Embryo: MS + 5 mg/L 2,4-D / 5 mg/L NAA; shoot: MS + 3 mg/L BA + 0.5 mg/L NAA + 3% maltose; root: MS + 3 mg/L NAA Organogenesis Rhizome buds NA, 5 w, 2 w Agrobacterium mediated + PCR Somatic embryo formation was highest on MS medium with 5 mg/L 2,4-D and 5 mg/L NAA, reaching 87.50% in Curcuma longa and 95.83% in C. mangga. Increasing NAA or 2,4-D to 8 mg/L reduced embryo formation to 4.2% and 8.3% in C. longa, and 4.2% and 12.5% in C. mangga, respectively [106] 36 Curcuma longa L. Management of osteoarthritis, fever, depression, liver diseases, and high cholesterol Sweden, India Callus: MS + 1 mg/L basta; shoot: 2.2 μM BA + 0.93 μM kinetin + 5% coconut water + 2% sucrose Indirect somatic embryogenesis Mature rhizomes 4 w, 3−4 w, NA Particle bombardment

gene gun method

+ GUS + PCRTransient GUS expression was observed in 91% of bombarded embryos after 24 h, while stable expression was detected in the shoot tips and roots of plantlets after 3 months [107,108] 37 India Cotyledon: B5 media + ½MS media; shoot: B5 media + 0.5 μM BA + 2.4 μM NAA; root: B5 media + 2.4 μM NAA Mature seeds NA, 25−30 d, 2−3 w Agrobacterium mediated + GUS + semi-quantitative RT-PCR The post-transformation regeneration efficiency was 2.9%, with a confirmed transformation efficiency of 1.5% (PCR-based) and a 36.4% survival rate after hardening [109,110] 38 Vanilla planifolia Jacks. For fever, spasms, blood clotting issues, and gastrointestinal distress India, Turkey, Indonesia Plant regeneration: 4.43 μM BA + 2.68 μM NAA Direct somatic embryogenesis Shoot Ttps NA, 45 d, 45 d Agrobacterium mediated + GUS + PCR + southern blot + northern blot The highest callus regeneration (80%) occurred in VK4, while 100% direct shoot regeneration was achieved in VK3 and VK6, with VK6 also yielding 50% rooting, 33.3% indirect shoot regeneration in VK2, and 71.4% globular-stage embryo formation in VK4. [111−113] 39 India − − − NA, NA, NA Agrobacterium mediated + GUS + PCR + southern blot + northern blot Transformation efficiency averaged 39.4% for the nptII gene and 23.4% for GUS across three independent experiments [87] 40 V. planifolia Jacks. For fever, spasms, blood clotting issues, and gastrointestinal distress Mexico Callus: MS + 50 mg/L cysteine HCl + 100 mg/L ascorbic acid + 0.45 μM TDZ; callus: MS + 0.45 μM TDZ, MS + 8.88 μM TDZ / 11.11 μM BA Cell suspension culture Immature seeds 4 w, NA, NA − In V. planifolia in vitro culture, B:R LEDs enhanced shoot elongation and chlorophyll synthesis during multiplication, while B LEDs promoted shoot elongation, root and leaf formation during rooting. All LED treatments increased photosynthetic pigment synthesis and achieved 100% acclimatization success [114] 41 Malaysia Shoot: MS + 1−10 mg/L BAP, ½MS + 1 mg/L BAP; root: ½MS + 1 mg/L BAP Organogenesis Nodes, shoot tips NA, 30−45 d, 30 d − Auxin-free half-strength MS medium with 1 mg/L BAP enabled 100% rooting and was optimal for shoot propagation and early differentiation, with stem nodal segments showing high regeneration potential [115] 42 Malaysia, Moroco Shoot + root: MS + 0.5 mg/L NAA + 1 mg/L BAP; Knudson C media (KC) + 0.5 mg/L NAA + 1 mg/L BAP; Vacin & went media (VC) + 0.5 mg/L NAA + 1 mg/L BAP Direct somatic embryogenesis Nodes NA, 2−6 w, 2−6 w − MS medium produced the highest shoot (2.37 ± 0.76 cm) and root (2.04 ± 0.95 cm) lengths with well-formed leaves and extended roots, significantly outperforming KC and VW media in V. planifolia nodal segment cultures [116,117] 43 Brazil Shoot: double culture system media + 1, 2, 3 mg/L BAP; root: double culture system media + 1, 2, 3 mg/L IBA Organogenesis Nodes, axillary buds NA, 30, 60, 90 d, 30, 60, 90 d − DPS medium with 1 mg/L BA yielded over a 2.5-fold increase in axillary shoot multiplication compared to SS medium after 90 d, with 100% rooting in full-strength MS (without IBA) and 100% acclimatization success. [118,119] NA: Not available. -

Several challenges persist in implementing CRISPR/Cas with tissue culture technology in spice crops[61]. One of the major hurdles is the low transformation efficiency in many spice crops, as they often exhibit recalcitrance to genetic modification due to complex tissue regeneration pathways[62]. Species like A. sativum and Z. officinale lack efficient in vitro regeneration protocols, limiting the ability to generate stable CRISPR-edited lines[63]. Moreover, prolonged tissue culture conditions can lead to somaclonal variations, which may introduce unintended genetic modifications, complicating the evaluation of CRISPR-induced edits[64]. Additionally, optimizing delivery methods for CRISPR reagents remains a challenge, as traditional Agrobacterium-mediated transformation and biolistic methods show variable success rates in spice crops[65]. The development of novel delivery approaches such as nanoparticle-mediated CRISPR delivery, electroporation of protoplasts, and viral vector-based systems may provide solutions to these limitations[66]. Another critical issue is the time-consuming and labor-intensive nature of tissue culture-based CRISPR workflows, making large-scale applications difficult[67].

To overcome the limitations associated with CRISPR/Cas genome editing in spice crops, it is crucial to refine transformation protocols and improve tissue regeneration efficiencies[68]. One approach is optimizing Agrobacterium-mediated transformation by identifying suitable explant tissues with high transformation potential, such as embryogenic calli or meristematic tissues[69]. The use of phytohormone combinations to enhance callus induction and somatic embryogenesis can significantly improve regeneration rates in recalcitrant spice crops like Z. officinale and A. sativum[70]. Furthermore, employing stress treatments such as osmotic conditioning and antioxidant supplementation can enhance explant viability and reduce oxidative stress during transformation, leading to better recovery of edited plants[71]. Protoplast-based CRISPR delivery systems, which eliminate the need for stable transformation, also show promise in editing species with low regeneration potential[72]. By optimizing polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated uptake of CRISPR components and integrating microfluidic platforms for efficient protoplast manipulation, transformation efficiencies can be improved. In addition to refining traditional transformation techniques, exploring non-tissue culture-based genome editing strategies such as in planta transformation offers a viable alternative for spice crop improvement[73]. In planta transformation bypasses the need for prolonged tissue culture by directly delivering CRISPR reagents into developing plant tissues, thereby reducing somaclonal variation and enhancing editing efficiency[74]. One promising method is the use of floral dip transformation, where Agrobacterium carrying CRISPR constructs is applied to flowering plants, leading to edited seed progeny[75]. While this technique has been extensively utilized in model plants like A. thaliana, its application in spice crops requires further optimization due to differences in floral structures and reproductive mechanisms[76]. Another emerging approach is nanoparticle-mediated CRISPR delivery, where functionalized nanoparticles are used to transport gene-editing components into plant cells without the need for transgene integration[77]. Additionally, viral vector-based CRISPR delivery systems can facilitate transient genome editing, enabling rapid trait modification without stable transformation[78]. These approaches not only enhance the feasibility of CRISPR in spice crops but also address regulatory concerns by minimizing foreign DNA integration[79]. Future research should focus on adapting these innovative methodologies to diverse spice crop species, ensuring their applicability for large-scale breeding programs and commercial applications.

-

Plant tissue culture methods such as anther culture, ethyl methyl sulfate (EMS) mutation, somaclonal variation, shoot tip/meristem culture, root tip culture, in vitro pollination, embryo rescue, and rhizome culture have been highly effective in achieving plant regeneration for traits improvement, population line development, and enhanced tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses in spice crops[120]. Additionally, plant tissue culture technique synthetic seed production has successfully facilitated the creation of artificial seeds, addressing challenges such as high water content, desiccation, microbial spoilage, and short seed lifespan in spice crops[121]. Plant tissue culture techniques have successfully enhanced biotic stress resistance, population line development, and phenotypic traits in various spice crops such as E. cardamomum, C. sativus, Z. officinale, P. nigrum, Amomum subulatum, Vanilla sp., C. longa, and A. sativum[122]. Key factors, including the selection of explants, appropriate concentrations of growth regulators, and controlled environmental conditions, play a crucial role in stimulating biological growth, physiological activity, and the regeneration of population lines. These factors also contribute to trait improvement and synthetic seed development in spice crops[123]. The careful selection of explants has been shown to effectively regulate gene expression, improving biotic stress resistance and promoting the synthesis of secondary metabolites in regenerated spice crop population lines[124].

Plant tissue culture techniques, along with consistent influencing factors, are highly effective in advancing trait improvement, population line development, synthetic seed production, and secondary metabolite synthesis in spice crops[125]. However, the integration of plant tissue culture methods with direct or indirect gene transfers, or the CRISPR/Cas system, has not yet fully contributed to morphological improvements, population line development, or variety and synthetic seed production. Further research is needed to explore the development of population lines, morphological improvements, and variety creation by integrating plant tissue culture techniques with gene transfer technologies, including CRISPR/Cas system. The combination of soilless culture with plant tissue culture methods can significantly enhance population line development, phenotypic improvement, variety and synthetic seed production, and secondary metabolite synthesis in spice crops under controlled environmental systems[126]. Studies are also required to improve traits, develop population lines or varieties, and enrich secondary metabolites in spice crops using soilless culture in combination with plant tissue culture techniques or gene transfer methods under controlled conditions. The integration of soilless culture and speed breeding techniques with plant tissue culture methods or gene transfer technologies holds great potential for developing population lines or varieties, creating biofortified populations, and improving resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses in spice crops within controlled ecosystems[127]. Further investigation is needed to address abiotic stress traits, improve population lines, develop biofortified populations, multiply varieties, enhance secondary metabolites, and form synthetic seeds in spice crops by combining soilless culture or speed breeding techniques with plant tissue culture methods or gene transfer technologies, including CRISPR/Cas, under controlled environment conditions. The application of soilless culture, speed breeding techniques, and gene transfer or CRISPR/Cas technologies is crucial to ensuring food security and enhancing germplasm resources (Table 2).

Table 2. Generations of population lines and variety in spice crops with plant tissue culture techniques.

S. No. Spices Country Tissue

cultured varietyTissue culture methods Traits improvement/

population line generationsExplants Ref. 1 Elethania cardamomum Matra. India − Anther Culture Homozygous Haploid Lines Anthers [128] 2 Crocus sativus L. India − EMS Mutation Mutant Population Lines Development Corm [129] 3 Zingiber officinale Roscoe China Wuling Somaclonal Variations Disease Free, High Performance Growth Parameters Or Yield Rhizome [130] 4 Z. officinale Roscoe USA Baby ginger Micropropagation Cold Hardy Ginger Lines, High Yield, Early Durations Rhizome [131] 5 Amomum subulatum Vietnam − Shoot Tip Culture Micropropagated Population Line Generations Shoot Tips [132] 6 Piper nigrum L. India − Somatic Embryo,

Meristem CultureVirus Free Population Lines Enhancement Shoot Tips [133] 7 E. cardamomum Matra. India − Micropropagation Virus or Disease Free Resistance Lines Such As Katte, Kokke Kundu, Nilgiri Necrosis, High Yield Population Lines Floral Buds [134] 8 Z. officinale Roscoe India − Somaclonal Variations, Invitro Pollinations,

Embryo RescueHigh Yield, High Quality Lines, Rhizome Rot or Bacterial Wilt Resistance Seed-Embryo [134] 9 Vanilla planifolia Jacks. India − Shoot Tip Culture,

Root Tip CultureRoot Rot Resistance Population Lines Development Shoot Tips, Root Tips [134] 10 Z. officinale Roscoe, V. planifolia Jacks., P. nigrum, E. cardamoum, Cuminum cyminum India − Synthetic Seeds Artificial Seed Productions Somatic Embryo, Shoot Tips [134] 11 Z. officinale Roscoe Malaysia − Micropropagation- Rhizome Culture

Disease Free Plants, Secondary Metabolites or Anti-Oxidants Synthesis Immature Rhizome Buds [135] 12 Z. officinale Roscoe China − Root Tip Culture High Yield, Autotetraploid Population Lines Generations, High Gingerol Contents Root Tip [136] 13 Curcuma longa L. India − Micropropagation High Yield, Rhizome Rot Resistance, Uniform Population Lines, High Curcumin Contents Rhizome [137] 14 Allium sativum L. Philippines − Shoot Tip Culture Onion Yellow Dwarf Virus, Leek Yellow Strip Potyvirus Resistant Lines, High Yield Medium Size Bulb, Shoot Tips [138] -

The phenotypic parts of spice crops are sterilized using appropriate protective stock solutions. Once sterilized, these parts are subjected to genetic engineering through the incorporation of direct or indirect gene transfers, or the CRISPR/Cas system, under controlled environmental conditions[139]. The transformed plant parts are then inoculated onto the organized and standard chemical composition media supplemented with stable concentrations of auxins or cytokinins to regulate both direct and indirect plant regeneration processes[140]. Callus induction typically occurs within 3 to 8 weeks, while plant regeneration is observed within 2 to 6 weeks in spice crops[141]. The regenerated plant population lines are then integrated into soilless or water-based culture systems to promote efficient biological and physiological growth under controlled environmental conditions[142]. These developed plant populations are further subjected to speed breeding techniques such as mass selection, bulk selection, pedigree methods, backcrossing, mutation techniques, clonal or asexual propagation, polyploidy, single seed descent (SSD), recombinant inbred lines (RILs), and near-isogenic lines (NILs) to facilitate the development of new varieties, seeds, and population lines[143].

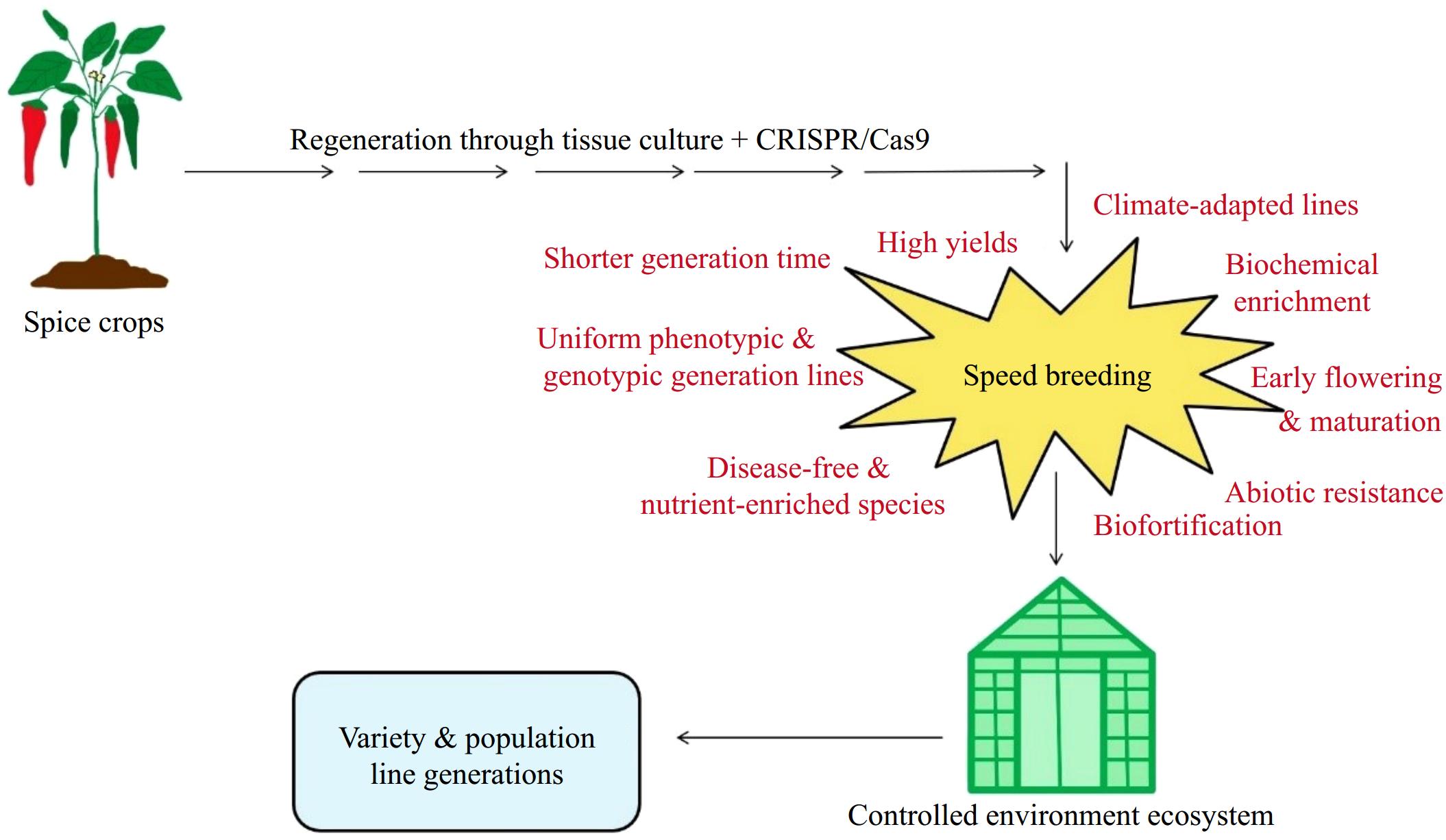

The integration of speed breeding techniques and soilless culture in plant regeneration for spice crops helps prevent the loss of regenerated plant population lines. By utilizing these techniques, spice crop varieties and population lines can be developed in a shorter generation time[144]. The combination of speed breeding techniques and soilless culture effectively supports the development of uniform phenotypic and genotypic plant population lines under controlled environmental conditions[145]. This integration has significant potential for developing biotic stress resistance (e.g., resistance to diseases, insects, and pests) and abiotic stress resistance (e.g., tolerance to water, light, temperature, heavy metals, frost, cold injury, problematic soils, and photo-insensitivity) in spice crops[146]. Furthermore, speed breeding techniques and soilless culture offer considerable promise for achieving biofortification, early flowering, early maturation, high yields, biochemical enrichment, metabolic enhancements, and climate-adapted lines in spice crops under controlled conditions[147]. However, the application of these techniques may also address morphological challenges such as self-incompatibility, male sterility, embryo abortion, pseudo-seed formation, seed setting issues, and the recalcitrant nature of some spice crops[148]. The use of speed breeding techniques and soilless culture can also prevent albino plant regeneration and help develop disease-free, nutrient-enriched species in controlled environments, contributing to climate restoration and food security[149]. Research is needed to promote plant regeneration, as well as the development of population lines or varieties, in spice crops through the integration of speed breeding techniques and soilless culture under controlled environmental conditions. Additionally, studies should focus on developing biotic and abiotic stress-resistant populations, biofortified or biochemically enriched population lines, and climate-smart lines using these integrated methods. Further investigations are required to explore plant regeneration in other spice crops by integrating soilless culture or speed breeding techniques with plant tissue culture methods or gene transfer technologies, including CRISPR/Cas, under controlled environmental conditions (Fig. 2).

-

The production and management of horticultural crops and tree species with the utilization of kitchen waste and wastewater in the surrounding home areas is referred to as home gardens. Other scientific terms for home gardens are kitchen garden or nutrient garden[150]. The home garden cultivates fruit crops—Magnifera indica, Musa sp., Manilkara zapota, Psidium guajava, Carica papaya, Citrus aurantifolia, Phyllanthus emblica, Punica granatum, Annona muricata, and Phoenix dactylifera; vegetable crops—Solanum lycopersicum, Solanum melongena, Capsicum annuum, Allium cepa, Abelmoschus esculentus, Momordica charantia L., Trichosanthes cucmerina, Luffa acutangula, Lagenaria siceraria, Amaranthus spp., Lablab purpureus, and Beta vulgaris; spice crops—Cucrcuma longa, Coriandrum sativum, and Trigonella foenum-graecum; medicinal plants—Aloe vera, Solanum spp., Acorus calamus, Centella asiatica, Mentha spp., basil, Ocimum tenuiflorum, Plectranthus amboinicus, Eclipta prostrata, Phyllanthu niruri, Cisscus quandrangularis, Soalnum trilobatum, Alternanthera sessilis, Phyla nodiflora, Solanum nigrum, and Chrysopogon zizanioides; flower crops—Rosa indica, Hibiscus rosa-sinersis, Jasminum officinale, and Nerium olerander; and trees—Callistemon acuminatus Cheel, Styphnolobium japonicum, and Bauhinia vahlii in the fenced surrounding areas[151]. Disposed plastic materials such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipes, PVC containers, and PVC buckets, along with natural fencing like bamboo terracing and metal terracing, and artificial fencing such as plastic pots/pits, cement pots/pits, and wooden containers are used in the application of kitchen waste and wastewater[152]. The utilization of home gardens recycles kitchen waste or wastewater and prevents waste disposal and microbial contamination. The application of home gardens effectively manages both biodegradable and non-biodegradable solid waste[153].

The convergence of tissue culture and genome editing technologies is revolutionizing the future of home gardening by enabling the development of high-yielding, disease-resistant, and nutritionally enhanced spice crops[154]. Tissue culture techniques, such as micropropagation and somatic embryogenesis, allow for the mass production of high-quality, pathogen-free spice plants like C. annuum, C. longa, and P. nigrum, ensuring a consistent supply of elite planting material for home gardeners[155]. These techniques also facilitate the rapid multiplication of rare or slow-growing spice crops that are traditionally difficult to cultivate in household environments[156]. With the integration of CRISPR-based genome editing, spice plants can be modified to exhibit desirable traits such as improved growth in confined spaces, enhanced resistance to common pests and diseases, and increased production of essential bioactive compounds. This ensures that home gardeners can grow robust, high-quality spices with minimal effort and reduced dependence on chemical pesticides or fertilizers[157].

The plant tissue culture methods and gene transfer techniques have effectively resulted in transformed/non-chimeric plant regeneration in home garden spice crops such as fenugreek and coriander[158]. The application of indirect gene transfer using Agrobacterium rhizogenes and plant tissue culture methods like hairy root culture or indirect organogenesis has effectively exhibited non-chimeric root regeneration in a short time period in fenugreek[159]. The use of indirect gene transfer with Agrobacterium tumefaciens and plant tissue culture techniques like indirect somatic embryogenesis has effectively stimulated embryo formation and non-chimeric shoot regeneration in coriander[160]. The comprehensive application of indirect gene transfers using A. rhizogenes or A. tumefaciens and plant tissue culture methods like organogenesis or somatic embryogenesis has successfully induced non-chimeric plant regeneration in home garden spice crops[161]. However, the application of the CRISPR/Cas system and plant tissue culture techniques have not yet been applied to home garden spice crops for plant regeneration, population line generation, morphological improvement, and biotic or abiotic stress resistance[162]. Studies may be required to explore plant regeneration and improvements in home garden spice crops using the CRISPR/Cas system and plant tissue culture techniques. Further investigation may be needed to improve efficient plant regeneration and mitigate regenerated plant loss in home garden spice crops with the application of soilless culture and plant tissue culture techniques, gene transfers, or the CRISPR/Cas system under a controlled environment ecosystem. Research may also be required to advance plant regeneration and improvements in home garden spice crops with the integration of soilless culture or speed breeding techniques, plant tissue culture methods, gene transfers, or the CRISPR/Cas system under controlled environmental conditions.

The advancements in tissue culture and genome editing technologies present several opportunities in the home gardening sector[163]. First, the development of dwarf or compact spice varieties through targeted genetic modifications can cater to urban gardeners with limited space, enabling efficient cultivation on balconies, rooftops, and indoor hydroponic setups[164]. Second, genome editing can enhance abiotic stress tolerance, allowing spice crops to thrive in diverse home environments with varying light, temperature, and humidity conditions[165]. Additionally, biofortified spice varieties with enhanced nutritional and medicinal properties-such as curcumin-enriched C. longa or capsaicin-enhanced C. annuum—can provide home gardeners with fresh, health-boosting spices tailored to dietary needs[166]. The commercialization of genetically improved spice plants through ready-to-grow tissue-cultured seedlings and CRISPR-edited seeds could open new markets for nurseries, biotech startups, and gardening enthusiasts[167]. As regulatory frameworks evolve, the accessibility of these advanced spice plants will further encourage sustainable, pesticide-free, and high-yield home gardening, ultimately contributing to food security and personal wellness[168,169] (Table 3).

Table 3. Approaches of genetic transformations and plant tissue culture techniques in non-chimeric plant regenerations in home garden spice crops.

S. No. Spices Country Media + growth

regulator levelsTissue culture methods Explants Callus induction, shoot regeneration, root regeneration (weeks) Transformation methods Regeneration and transformation efficiency Ref. 1 Trigonella foenum-graecum L. Greece Callus + root: 2.2 g/L MS salts + vitamins + 1% sucrose + 0.05% MES (2-N-morpolino ethanesulfonic acid); full strength McCowns WPM + 3% sucrose + 0.05% MES; full strengths Hoagland nutrient solutions Hairy root culture/Indirect organogenesis Seeds 2, NA, 2.5−3 Agrobacterium rhizogenes

+ GFP + PCRCallus responder transformed root at 12 d in solid or liquid media [159] 2 Coriandrum sativum L. India Callus: MS + 1 mg/L 2,4 D; embryo: MSH media (Murashige & Skoog, 1962 and Schenk and Hildebrandt, 1972) + 0.5 mg/L NAA + 1 mg/L 2,4 D; shoot: MSH media + 0.5 mg/L BAP Indirect somatic embryogenesis Seed: radicle: root tip NA, NA, NA Agrobacterium tumefaciens + GUS + PCR Embryo successfully exhibited plantlets [160] NA: Not available. -

Plant tissue culture methods, along with gene transfer techniques are highly effective in tissue-cultured plant regeneration and population line development in spice crops. Plant tissue culture methods and direct or indirect gene transfers have successfully facilitated the development of modified gene tissue-cultured plant regeneration in several spice crops, including Vanilla spp., C. sativus, E. cardamomum, P. nigrum, C. longa, garlic, C. cyminum, Myristica spp., C. verum, S. aromaticum, and Nigella sativum have been achieved through the use of distinct growth regulators, media chemical compositions, explant selections, organic supplements, and controlled environmental conditions. Plant tissue culture methods and direct or indirect gene transfers are essential for stimulating modified gene plant regenerations within a shorter generation time in spice crops. Plant tissue culture methods and gene transfers have proven successful in improving traits, developing population lines, producing varieties or seeds, enhancing biotic stress resistance, and increasing secondary metabolite production in spice crops. However, the full integration of plant tissue culture techniques and CRISPR/Cas systems has not yet been fully realized in modified gene plant regeneration, population line development, enhancement of biotic and abiotic stress resistance, and the creation of climate-adapted lines in spice crops. Further research is needed to explore tissue-cultured plant regeneration and population line development with the intervention of plant tissue culture techniques and CRISPR/Cas systems in spice crops. The integration of soilless culture or speed breeding techniques with plant tissue culture methods and gene transfer or CRISPR/Cas systems has been shown to efficiently promote plant regeneration, development of biotic and abiotic stress-resistant population lines, enhancement of biofortified population lines, and the generation of climate-adapted population lines and Donald concept-plant ideotype under controlled environmental conditions. Further research is needed to investigate modified gene plant regeneration, enhancement of biotic and abiotic stress-resistant population lines, and the development of biofortified and climate-adapted population lines in spice crops by combining soilless culture or speed breeding techniques with plant tissue culture methods, gene manipulations, or CRISPR/Cas systems under controlled environmental conditions. The comprehensive integration of these novel technologies holds great potential for addressing food security, combating undernourishment, and enhancing germplasm resources in spice crops within controlled ecosystem environments.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualizations: Sharma A, Pandey H, Misra V; draft manuscript preparations, compilation: Sharma A; evaluation, proofreading: Pandey H, Misra V, Chatterjee B, Sutradhar M, Kumar R, Heisnam P, Devadas VASN, Kesavan AK, Mall AK, Vashishth A, Tehri N, Longkho K, Sharma S; directions: Pandey H, Misra V, Sutradhar M, Kumar R, Heisnam P, Devadas VASN, Kesavan AK, Mall AK, Vashishth A, Tehri N; figure designing & making: Misra V. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Himanshu Pandey, Varucha Misra, Avinash Sharma

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Pandey H, Misra V, Sharma A, Chatterjee B, Sutradhar M, et al. 2025. Interventions of plant tissue culture techniques and genome editing in medicinally important spice crops. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e023 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0019

Interventions of plant tissue culture techniques and genome editing in medicinally important spice crops

- Received: 17 January 2025

- Revised: 09 April 2025

- Accepted: 15 April 2025

- Published online: 22 July 2025

Abstract: The recalcitrant nature and high water content of seed germplasm in spice crops contribute to pest infestation, desiccation, microbial contamination, and reduced lifespan. Vegetatively propagated spice crops also face biotic and abiotic stresses, limiting their yield potential. Over-extraction and formulation of value-added products have further reduced the efficacy of asexual propagation methods. This review explores the integration of plant tissue culture techniques with gene manipulation approaches, such as gene transfer and CRISPR/Cas systems, to overcome these challenges. Tissue culture methods, including organogenesis, somatic embryogenesis, anther culture, shoot tip culture, and in vitro pollination, have been effective in enhancing disease resistance, early maturity, and yield potential in crops like cumin, turmeric, ginger, vanilla, saffron, cardamom, and black pepper. Gene transfer techniques, such as biolistic transformation and agrobacterium-mediated methods, have successfully achieved non-chimeric plant regeneration and synthetic seed production, mitigating desiccation and microbial contamination. Somaclonal variation has improved growth, yield, and stress resilience, as seen in tissue-cultured Wuling ginger and micropropagated baby ginger. Despite these advancements, the application of CRISPR/Cas in spice crops remains underexplored. Future research should focus on integrating CRISPR/Cas with tissue culture for enhanced stress tolerance, biofortification, and climate adaptation. Additionally, soilless culture and speed breeding could accelerate spice crop improvement, aligning with the Donald concept of plant ideotype. This review provides insights into these advancements and their potential to transform medicinally important spice crop cultivation.

-

Key words:

- Medicinally important spices /

- Traits /

- Gene transfers /

- CRISPR/Cas /

- Speed breeding /

- Plant tissue culture