-

In the USA, over 27% of adults age 18 or older have a disability, and over 12% of adults have a mobility disability[1]. Persons with disabilities (PwD) rely heavily on alternative forms of transportation and have a higher reliance rate on public transportation compared to the general adult population[2−4]. Of the population aged 18 to 44 years old, 4.5% have a mobility disability and individuals who are 65 or older, this prevalence rate is more than six times higher at 28%[1]. Thus, there is a critical need to increase the accessibility of transportation to accommodate the growing population who have mobility disabilities[5].

Common methods of transportation include public transportation, paratransit, on-demand vehicles, and rides from family members and friends[6−9]. Although alternative options of transportation exist, they do not always function at the level necessary to be considered accessible and useful for PwD[7]. Paratransit can have challenges such as fixed hours, excluding holidays, eligibility requirements and long waiting times, or scheduling well in advance[2,6,7,9−11]. It is important to note there are no 'Uber-type' options for PwD. Further, public transportation often operates on fixed routes and can have inaccessible pick-up and drop-off (PUDO) locations which can cause additional problems for PwD[2,6,7,11].

Inaccessible transportation methods can have significant negative effects on the lives of PwD. These negative results come from missed medical appointments[2,8,10], decreased involvement in social activities[2,3,8,10,12], and lost opportunities for schooling and employment[2,3,8,13]. Additionally, missing out on social activities can contribute to perceived feelings of isolation[12,14,15]. Recreational activities that require spontaneity are known to be problematic for PwD because of the requirement of advanced scheduling of rides[2,3,9,10]. These are all aspects of the lives of PwD that are affected or lost without accessible transportation.

Because of their ability to increase accessibility for those individuals with disabilities, autonomous vehicles as a form of accessible transportation have been the focus of many studies[4,6,8,16−22]. Importantly, autonomous vehicles require a robust PUDO process that ensures the safety of the passengers. The typical PUDO process for autonomous vehicles includes using an app to call the vehicle, identifying the vehicle in the street, loading quickly into the vehicle, and then safely exiting the vehicle after arrival at the drop-off location. The autonomous PUDO process can be much more complex for PwD and filled with challenges. First, how successfully PwD interface with apps and their preference for calling an AV is unknown. Some researchers have found that elderly adults and PwD can have trouble accessing and using technology that is not specifically designed to support their abilities, but it is unknown for the greater community and greatly varies from person to person[23−25]. Second, PwD experience difficulty identifying the vehicle due to a variety of reasons (e.g., visual impairments or being physically lower to the ground in a wheelchair)[9]. There is a dearth of research exploring preferences and needs for PwD to identify their transportation. Next, PwD's preference for PUDO zones (where a car stops so a person can load into a vehicle) is immensely important as it pertains to the safety of the loading process. PUDO zones have a variety of barriers including how far PwD have to travel to the zone, the amount of traffic, how much time it will take to load, and how much room it takes to load into a vehicle[26]. Some studies focused on the accessibility of current pedestrian infrastructure, such as handrails or sidewalk imperfections, for PwD, but very few had in-person interviews about these barriers[27−29]. Additionally, these studies rarely looked at transportation or PUDO barriers, rather they investigated pedestrian barriers. There is a paucity of studies that involve real-world, in-person evaluation associated with current and future PUDO zones that obtain real-time decision-making data directly from individuals as they navigate these areas.

Finally, how a person with a disability loads into a vehicle is a challenge, as autonomous vehicles will have to be fitted to accommodate a wide array of individuals and their travel companions. Some research has been conducted to understand the preferences of wheelchair users but has primarily focused on those who are operating the vehicle or riding in the front seat. These studies also do not explore the possibilities of travel in an AV[30]. Additionally, nearly all of the research surrounding preferences of PwD during the PUDO process has been conducted through survey data and did not have PwD complete in-person research in real-life settings. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to understand the preferences and decision-making process of PwD navigating the entire PUDO process, including requesting and identifying a vehicle, finding safe locations for PUDO zones, and identifying how they would load into a vehicle. This was achieved by bringing in individuals who had limitations with regard to their mobility and were assistive device users. Individuals were brought to an outdoor environment and spent approximately two hours navigating through different real-life scenarios and identifying the contributors that affected their decisions for navigation and transportation. This work has the potential to be implemented in transportation for PwD to improve the interface between PwD and technology, improve the safety of PUDO zones, understand the needs for AVs, and to better the experience of travel for PwD in the future.

-

Twenty five individuals participated in this study, all had mobility disabilities. There were 14 users of manual wheelchairs, five users of motorized wheelchairs (which included both motorized wheelchairs and scooters), and six users of walking aids (walkers, canes, crutches, or other mobility aids). The aim was to have a broad demographic to elicit a wide range of perspectives on the matters we investigated. There were 16 males and nine females. The age range of participants was 20 to 92 with an average age of 42 years (18 years standard deviation). For analysis, participants were separated into three age groups: under 32 (n = 9), 32 to 50 (n = 9), and over 50 years old (n = 7). These age ranges were selected based on the natural grouping of ages of our participants.

Study methods

-

Participants were asked to navigate through five real-world scenarios, which focused on multiple aspects of accessing a PUDO location and the loading process. The real-world scenarios were staged at Michigan State University's Spartan Village (MI, USA), which is a complex that has several existing PUDO zones for public transportation. For each scenario, participants were asked to complete a task, provide answers to the questions related to that scenario (or rank the situations based on their preference), and describe why that selection was made. The five scenarios are described in the next sections. Participants provided information about their age, sex (as assigned at birth), assistive device type, disability, and transportation methods they typically use. There was an option for each scenario that was safe, accessible, and compliant with The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), but the participants were encouraged to complete the scenario how they would in the real world, which may not have followed the route of ADA compliance. All data were recorded, deidentified, and then analyzed.

Study scenarios

Scenario one: pick up zone preferences

-

Participants were placed at a designated starting position and were given four locations for PUDO zones. Participants were asked to rank order the pick-up zones based on their personal preference. The zones were over the grass to a curb, an intersection, a bus stop, and a parking lot. These options were chosen because they represented common PUDO zones that are available on most streets. The designated starting position was purposefully located closest to the options with the greatest number of barriers and farthest away from the safest options (bus stop and parking lot) (Fig. 1). This scenario was used to better understand the priorities and preferences of device users, weighing safety and comfort against the distance or time it would take to travel to the PUDO zone. For example, choosing a closer, but larger hurdle would indicate prioritizing time over safety, whereas choosing a longer distance with fewer risks would indicate the opposite. Participants were asked to rank the four zones from most optimal to least optimal PUDO zone and provide their reasoning for the ranking. Participants were then asked if their answers would change under high-traffic conditions or poor weather (e.g., rain, snow).

Figure 1.

(a) PUDO location for the intersection (yellow flag) and bus stop (blue flag) from the starting point of scenario one. (b) PUDO location for the closest over grass location (red flag) and parking lot (purple flag) options from the starting point of scenario one. (c) Overhead image of scenario one with each PUDO location labeled.

Scenario two: vehicle identification

-

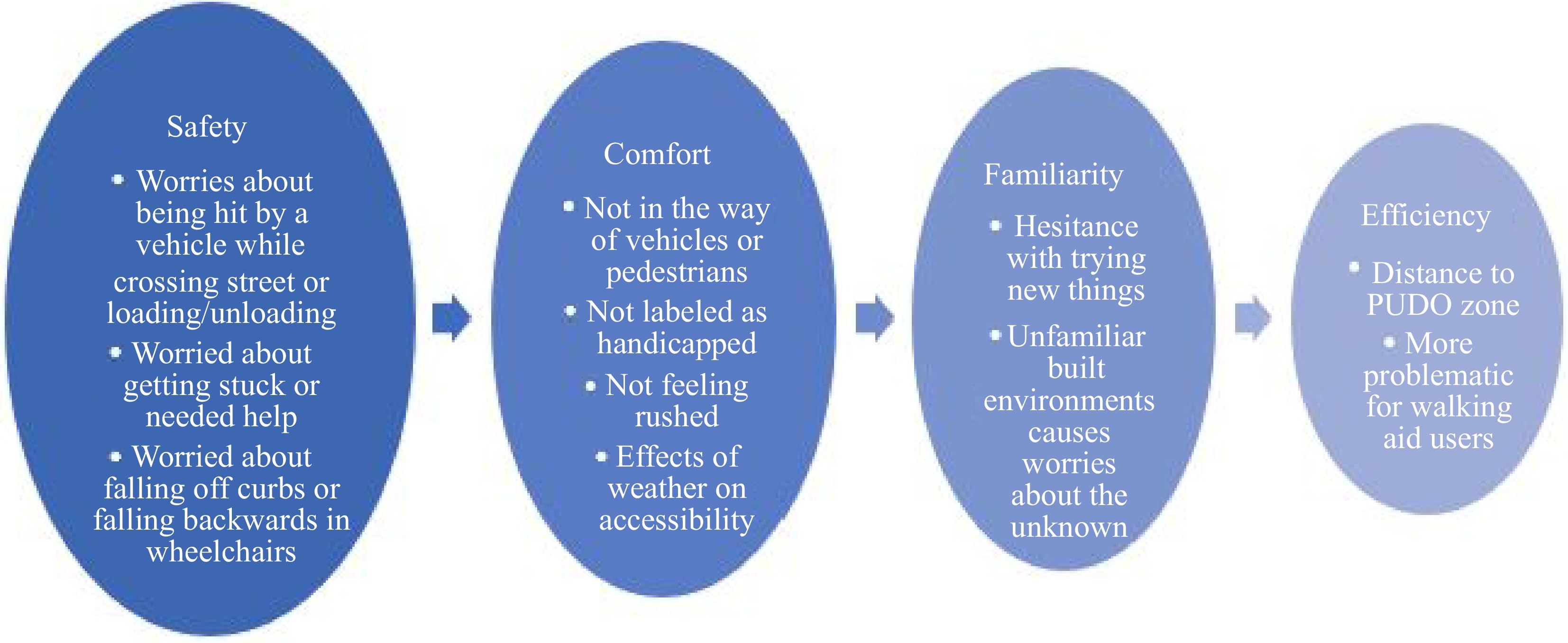

The goal of this scenario is to understand the challenges with current approaches of using license plates to identify vehicles for those who have disabilities as well as identifying preferable options and why those are preferred. Participants were asked to identify, from their perspective, the optimal way of identifying a potential PUDO vehicle. There were three types of identifiers: a number-letter combination, a shape, and a license plate (Fig. 2). For the number-letter identifier, it was one number followed by one letter. For the shape, there was one shape on the identifier, and the options included a star, square, and circle. For the license plate, it was similar to a standard Michigan license plate with a combination of three letters followed by four numbers, but on the side of the car in a larger font. All the identifiers had black text with a white background printed on a 30.48 cm by 22.86 cm (12 × 9 in) magnet and attached to the side of a car on the rear door. These identifiers were selected to have a range of complexity of identification and were placed on the rear door near the sidewalk due to challenges faced by PwD to access the rear of the vehicle to read the license plate. This information is critical to properly identify the correct vehicle as without a driver present in an autonomous vehicle there would not be someone to verbally confirm they are in the correct vehicle and the user could end up in the wrong location. Participants were also asked to identify their preference on how to be informed of their identifier/vehicle, either via a text message or a phone call. Based on their response, participants were sent a text message or received a phone call with their identifier. They were then asked to identify and navigate to the correct vehicle. They were also asked to rank three locations for the identifier and provide their reasoning: on top of the vehicle, the side, or on the rear of the vehicle (where the license plate is located).

Figure 2.

(a) Lineup with three cars as shown in scenario with the shape magnets on the car. (b) Example of the shape identifier. (c) Example of the number-letter identifier. (d) Example of the license plate identifier.

Scenario three: vehicle loading/unloading

-

The importance of this scenario was to gather information about the preferences of participants on the loading process both into and out of the vehicle. With each of these options, all of the currently available combinations of loading and unloading from an accessible vehicle were analyzed. The three different aspects were the direction of loading (perpendicular or parallel), preference between ramps and lifts, and location on the vehicle (rear or side). Participants were shown five different methods for loading into a vehicle that included combinations of loading type and orientation: perpendicular lift, parallel lift, rear lift, side ramp, and rear ramp (Fig. 3). The lift was 81.28 cm (32 in) wide by 121.92 cm (48 in) long. The ramp was 76.2 cm (30 in) wide and 177.8 cm (70 in) long. Participants were then asked to rank their preferred method of access from most preferred to least preferred and provide their reasoning.

Figure 3.

Lift and ramp methods for loading into the vehicle. (a) Perpendicular side lift. (b) Parallel side lift. (c) Side ramp. (d) Rear lift. (e) Rear ramp.

Scenario four: obstacle navigation

-

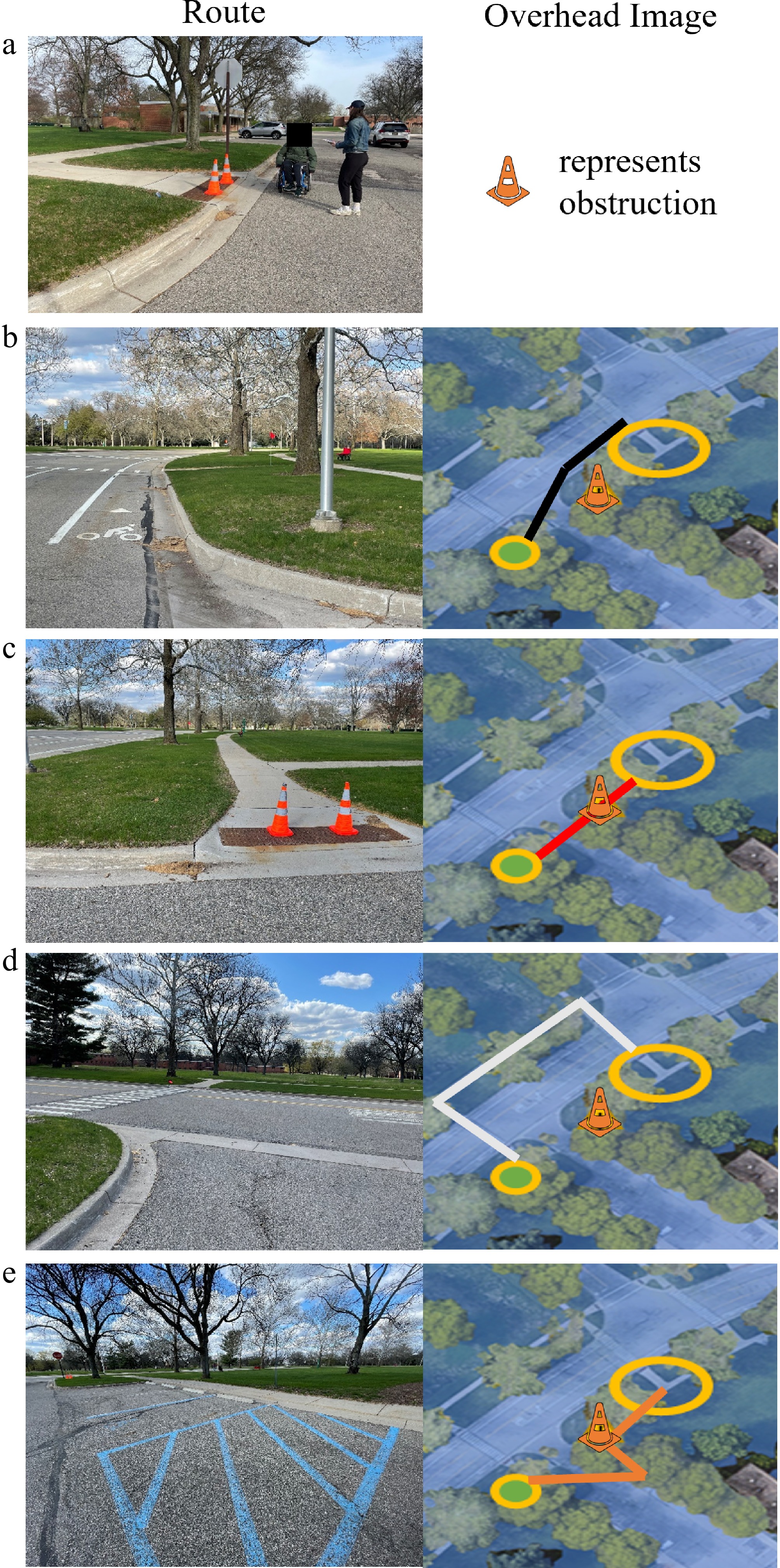

This scenario was important because it identified the approaches used to travel around barriers and the rationales for those decisions. Curb cutouts can become blocked for several reasons such as a tree limb falling into it, infrastructure damage, or construction blocking the path. When these curb cutouts are closed individuals need to assess the situation and choose the best path around it to get to their destination. The options that were presented to the participants were viable in most streets: going over the curb, using the bike lane, crossing the street and crossing back on the other side of the closure, or using the nearest curb cutout in a parking lot (Fig. 4). The starting location was similar to scenario one in that the closest option, going over the curb, would be the most challenging and dangerous and the furthest option, crossing the street twice, would take a long time and require extra energy. This was done to further understand the relationship between safety and time in the decision-making process. They were then asked to rank the prompted navigation methods from most preferred to least preferred and provide their reasoning.

Figure 4.

(a) Participant next to the blocked sidewalk at the starting point. (b) Bike lane option with a schematic of the route drawn on the overhead image of the area. (c) Over the curb option with a schematic. (d) Crosswalks used to cross the street twice with the schematic. (e) Parking lot option with a schematic.

Scenario five: distance

-

Finally, this scenario investigated how far participants were willing to travel to a designated PUDO zone from a waiting area if they needed one. Because popular PUDO zones include parking lots and bus stops, there is potential for high pedestrian traffic that can make it difficult or cumbersome to wait in that location as a device user. Other options that were further away, but away from traffic and people were explored. Understanding how far participants are willing to travel to designated PUDO zones is therefore critical because if a participant is not willing to travel the required distance, the PUDO zone is no longer an option. So, this scenario asked participants if they needed a bench and how far they would be willing to travel (there and back) to either sit on a bench or to wait near one. Three locations were shown (Fig. 5): one 3 m (~10 ft) past the pickup zone, the second was 24 m (~80 ft) past the pickup zone, and the third was 54 m (~180 ft) past the pickup zone. They were also asked whether or not they would travel to a covered bus stop in bad weather, such as rain, snow, extreme heat, or cold, that was even further – 110 m (~360 ft) past the pickup zone. The furthest location (the bus stop) was chosen at 110 m away because it is common for bus stops in larger cities to recur every 200 m and this point would be the maximum distance at half-way between stops[31]. The inclusion of the third bench location (around the half-way point to the bus stop) was to better analyze the effect the distance played on the participants desire to be away from pedestrian traffic. Participants were also asked how long they would like the vehicle to wait for them to access the PUDO zone and be prepared to load. Participants answered open-endedly.

-

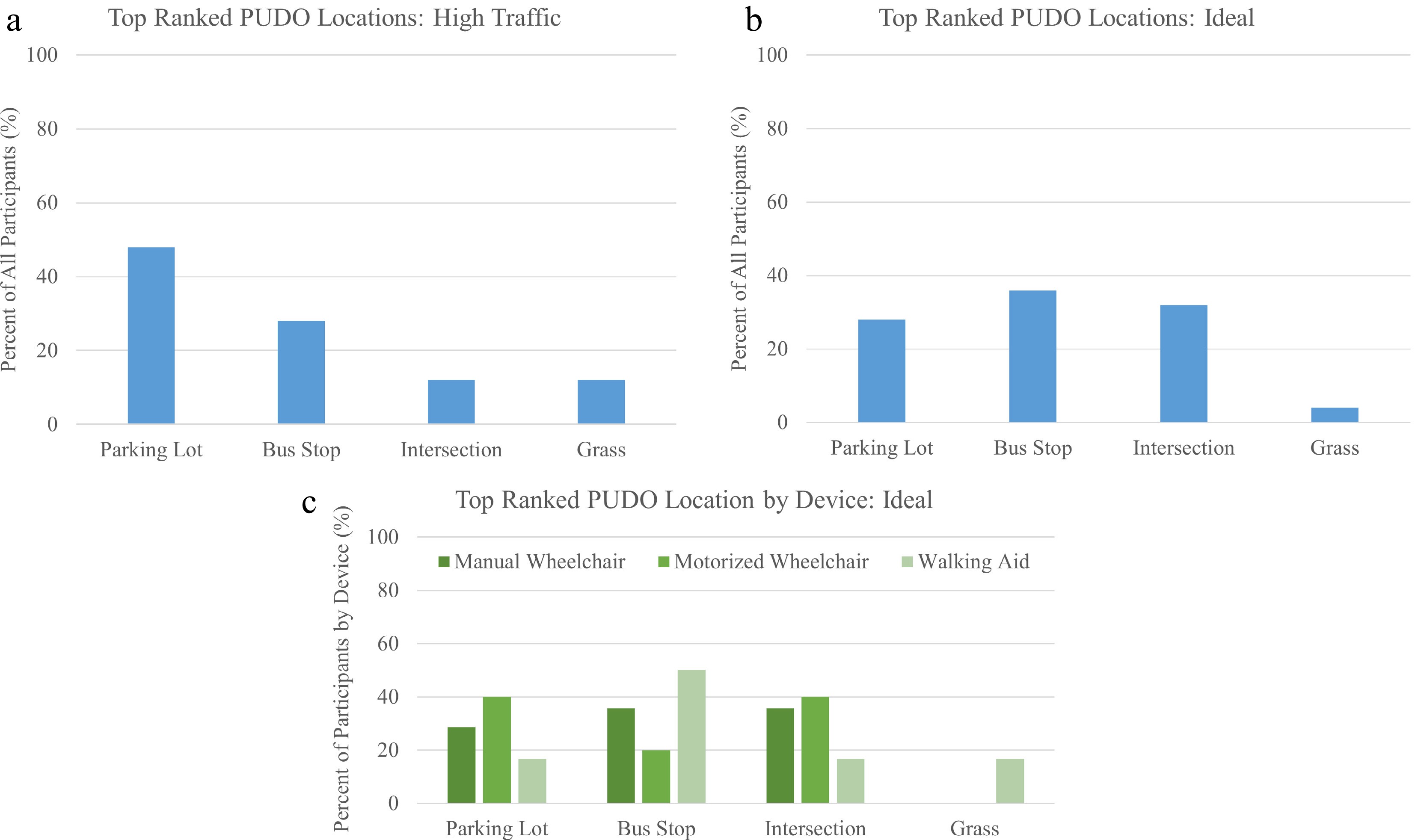

Participants were asked to identify their top choice from the four designated PUDO zones (Fig. 6a). Participants who chose the parking lot as their top choice decided to do so because it was the option with the least amount of possible traffic and they did not feel that they would be rushed to load into the vehicle. A challenge identified by users for the parking lot option was that they needed to cross the street to get there. Many expressed a concern about the possibility of being hit by another vehicle in the road or even in the parking lot. The reason participants selected the bus stop was because it was a paved area that was designed for a PUDO zone. However, a lack of curb cutouts, as well as competing with buses for this location were challenges. Participants who selected the intersection did so because it was a closer option with a curb cut out and there was no grass to traverse over, but some were worried that there may be foot traffic or impatient drivers at the intersection. The consistently positive reason for the 'over the grass' pickup was that it was the closest option. However, the majority stated they were not comfortable traveling on the grass and only one person (a walking aid user) selected it as their top choice for a regular traffic situation. In general, participants prioritized their safety and comfort over the time it would take to load.

Figure 6.

(a) Participant's preferred PUDO location. (b) Participant's preferred PUDO location in a high traffic situation. (c) Participants preferred PUDO location based on assistive device used.

Participants were asked if a high traffic situation would change their selection. All participants who chose the parking lot under typical traffic conditions maintained the parking lot as their preferred choice even in a high-traffic situation (Fig. 6b). Of the participants who chose the intersection as their initial preferred location, 75% changed their response in regard to high traffic. Of those who initially chose the bus stop, 22% changed their response. The most frequent location change for both the bus and the intersection selection was to the parking lot. Based on sex, females (67%) were more likely to change their location in the case of high traffic (primarily away from the intersection and toward the parking lot), while only 19% of males changed their answer in a high-traffic situation. These data indicated that in high-traffic situations, participants prioritized safety even greater than before, and females tended to see high-traffic situations as more problematic than males.

In the event of bad weather (e.g., rain, snow, cold, and excessive heat), 83% of participants indicated that access to the building in the parking lot would impact their choice of PUDO location and they would switch their preferred choice to the parking lot so they could utilize the building for shelter. Participants also stated that bathroom access in the building would be beneficial, particularly if the wait time for their transportation was long.

Overall, there are many factors that influence an individual's decision on PUDO zone, with some of the most crucial being weather and automobile traffic conditions. In worst-case scenarios (i.e., bad weather), the majority of participants were most comfortable with the safest option: the parking lot. The preferences for mobility device users are important for instructing future AVs where to pick up an individual. Ideally, future vehicles should incorporate real-time data, such as traffic flow and weather.

Scenario two

-

Participants preferred a text (82%) over a call (18%) when asked about how they would like to receive identifying information about the 'on-demand' vehicle. For participants under the age of 32, 89% preferred a text message, similarly, 88% of the 32 to 50 age range preferred a text message. However, only 57% of the over-50 age group preferred a phone call. Overall, participants' preference for vehicle identification was the number-letter combination (72%), followed by the shape (24%), and then the license plate (4%). Participants favored the number-letter combination because of the larger character size, simplicity, and ease of remembering. For the shape option, participants commented that it was easy to see and recognize, however, they were worried about the lack of variety, especially if there were multiple vehicles picking up different users in the same area. They also shared that the lack of variety in shapes could lead to the use of complex shapes that may be difficult to identify, unfamiliar, or hard to distinguish. Participants reported that there were too many characters to remember and the text was too small for the license plate identifier.

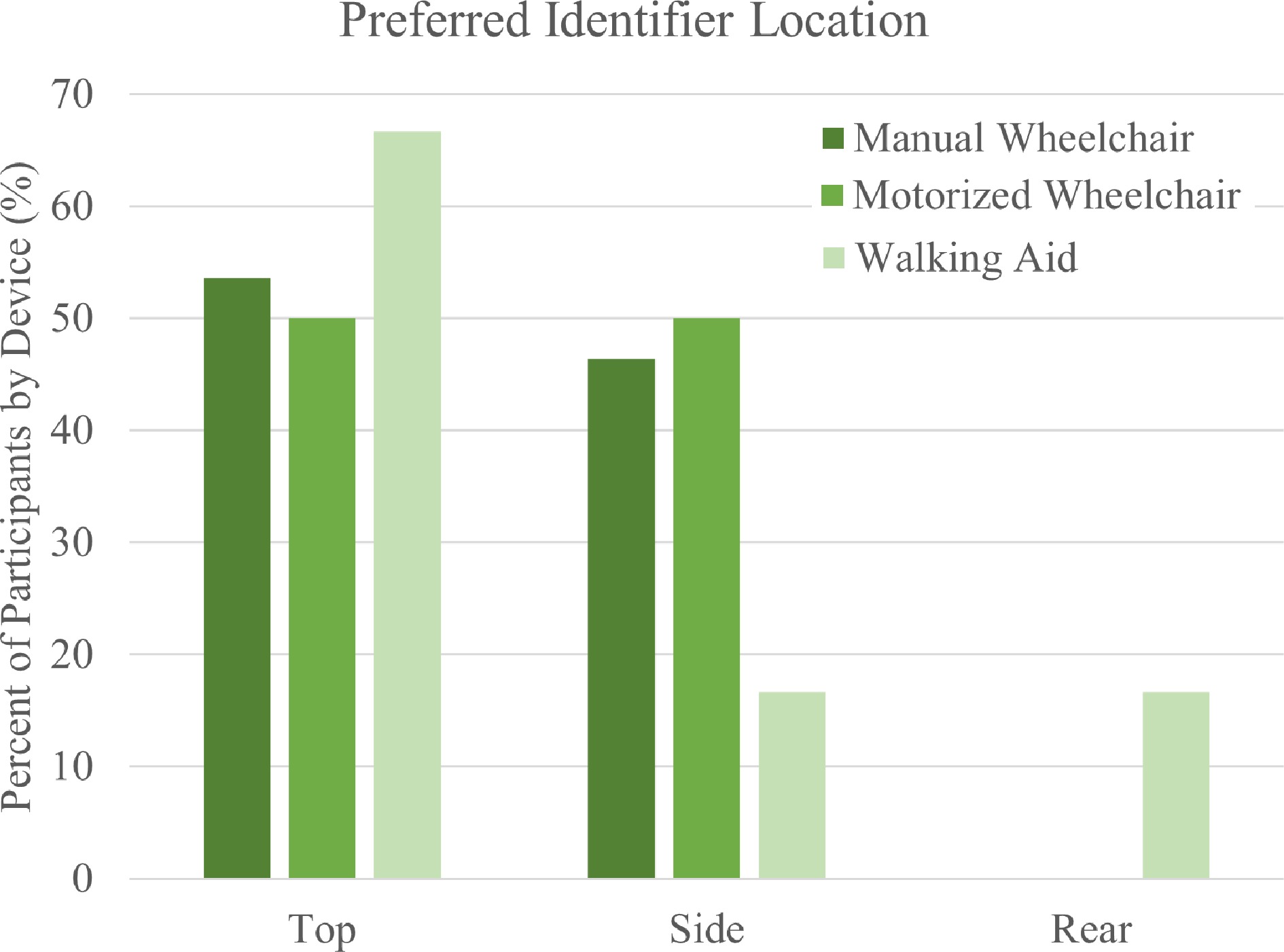

Fifty percent or more participants in each age group preferred the top of the vehicle as the location for the identifier (Fig. 7). Manual wheelchair and motorized wheelchair participants who sat lower to the ground had a lower percentage (50%−54%) compared to walking aid users who chose the top of the vehicle 67% of the time. Participants liked the top of the vehicle for the location of the identifier because it allowed them to see the vehicle from a further distance and it was easy to recognize, but there was concern about the vehicle being too tall to see the identifier, especially from a seated position, or if they could identify the vehicle in a busy area with lots of taxis or delivery drivers. A positive about the side of the vehicle was that it was at a location where they would be loading from, making it easier to confirm it was the correct vehicle. Additionally, the side had the space to accommodate a larger identifier. A possible drawback of the side location of the identifier is that they would need to be directly on the side of the vehicle to see the identifier. For the rear of the vehicle, many participants said that identifier location was often obstructed by other vehicles and that they did not want to have to navigate around the vehicle to see it, which could force them to go into the street.

Figure 7.

Percent of participants based on device used that preferred each vehicle identifier location.

Overall, there were trends among all users for the type of identifier (number-letter) and location on the vehicle (side/top). These changes can become especially important in locations where there is bad lighting or at night, in bad weather, or if the user was in a rush as it could be impossible for them to see the license plate on the rear of the vehicle. With this in mind, future vehicles should take into account the other options of identification depending on the area they would be operating in.

Scenario three

-

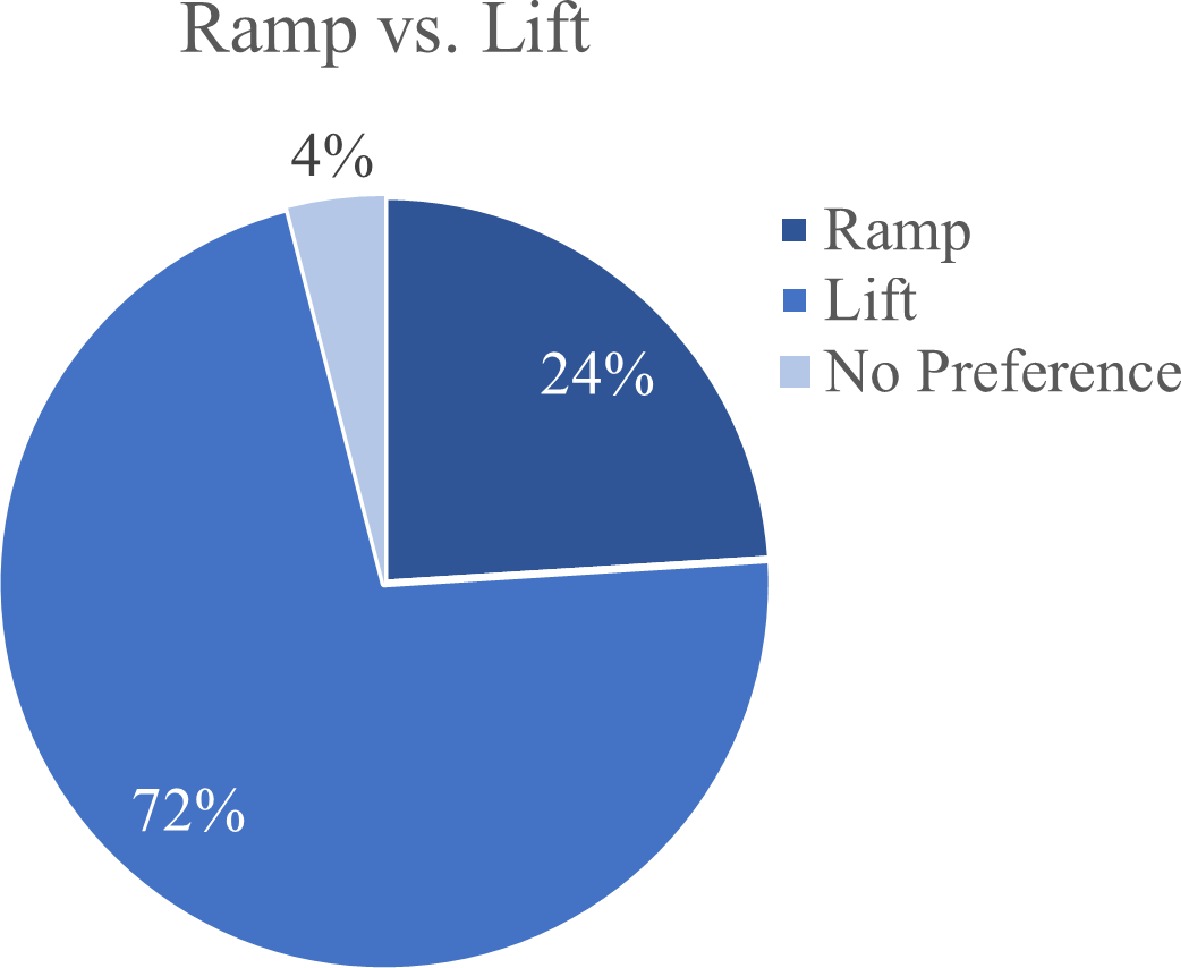

Participants were also asked about their preferences between a ramp and a lift with regard to loading into the vehicle. Overall, participants preferred the lift to the ramp loading systems (Fig. 8). The top selections were the perpendicular lift, followed by the parallel lift and the rear lift. There was no preference difference between the ramp loading location (rear or side). The reasons participants preferred the lift were the lack of slope and thus not having to 'fight against gravity' up a ramp and they felt more secure. Participants who preferred the ramp noted the shorter loading time, the feeling of increased control, and greater stability for some walking aid users.

All participants who were over the age of 50 preferred the lift, 78% of those in the youngest group (under 32 years) preferred the lift over the ramp, and 56% of 32 to 50-year-old participants preferred the lift over the ramp. Seventy-eight percent of the female participants preferred the lift, and 69% of the males preferred the lift.

Based on the assistive device used, both motorized wheelchair and walking aid users were more likely to try the parallel lift, even when they were unfamiliar with that loading method than the manual wheelchair users. Manual wheelchair users were more likely to choose the perpendicular lift.

Participants who chose the perpendicular lift indicated it was due to the ease of loading as well as familiarity. They stated a drawback to perpendicular lifts was having to maneuver and turn inside the vehicle after loading, as participants preferred to face forward while in the vehicle. They also preferred to rotate so they could face the direction they were exiting when it was time to leave the vehicle. Participants who selected the parallel lift indicated a positive of this approach was that they would already be facing forward inside the vehicle upon loading. A drawback to the parallel lift was being uncomfortable with the unfamiliarity of that loading method and that it could be harder to navigate into the lift and may have to navigate into the street to access the lift. Participants liked the extra space the rear lift provided, however, they did not like the abrupt turn to get into the vehicle (assuming they were at the side and had to navigate to the rear).

Aside from logistical issues loading into a vehicle, participants also noted social concerns about loading location that contributed to their decision. Fourty-two percent of participants reported that social aspects to rear loading also affected their desired loading method. Participants commented that the acceptability of rear loading would depend on the internal seating arrangement and how close they were to their friends. Being too far away from the other passengers was noted as a feeling of isolation or 'less important', especially if they were traveling with family and could not continue or be part of the conversation due to the seating arrangement. The other main social concern was feeling 'like cargo'. In contrast, participants reported feeling 'less handicapped' when side loading compared to rear loading.

Interestingly, when analyzed based on the assistive device used, 0% of motorized wheelchair users reported that there were definite social aspects to rear loading, whereas 33% of walking aid users, and 43% of manual wheelchair users did. When analyzing data based on age, only 11% of participants under 32 reported social aspects to rear loading, 14% of the over 50 group noted social issues, and 75% of the 32 to 50 years old participants reported social aspects to rear loading. Also, only 11% of females reported social aspects to rear loading compared to 47% of male participants.

Wheelchair users had specific feedback regarding ramps. Participants appreciated that a side ramp may not be to be as steep if it went onto the curb. Additionally, individuals indicated that ramps were more reliable than lifts. Participants who did not prefer the ramp indicated that they would need more space to gain enough speed to make it up the ramp. Individuals also commented on the possible narrowness of a ramp as a potential cause for concern, especially for motorized wheelchair users. Participants liked that they could roll in and out of the vehicle quickly and were already facing forward with the rear ramp, but did not like the possibility of being out in traffic to access the ramp.

Overall, participants' preferences were based on past challenges or preferences with the use of each method of loading. However, for many participants, the parallel lift orientation was unfamiliar, and without the use of in-person acted-out scenarios it would have been difficult to visualize how it could work. One of the biggest fears for persons with disabilities is getting stuck without a way to get out or needing to navigate out in an orientation that is uncomfortable for them (e.g., backward). Without a driver present in the vehicle, it was noted that the system needed to be reliable as there would not be any human intervention if something went wrong.

Scenario four

-

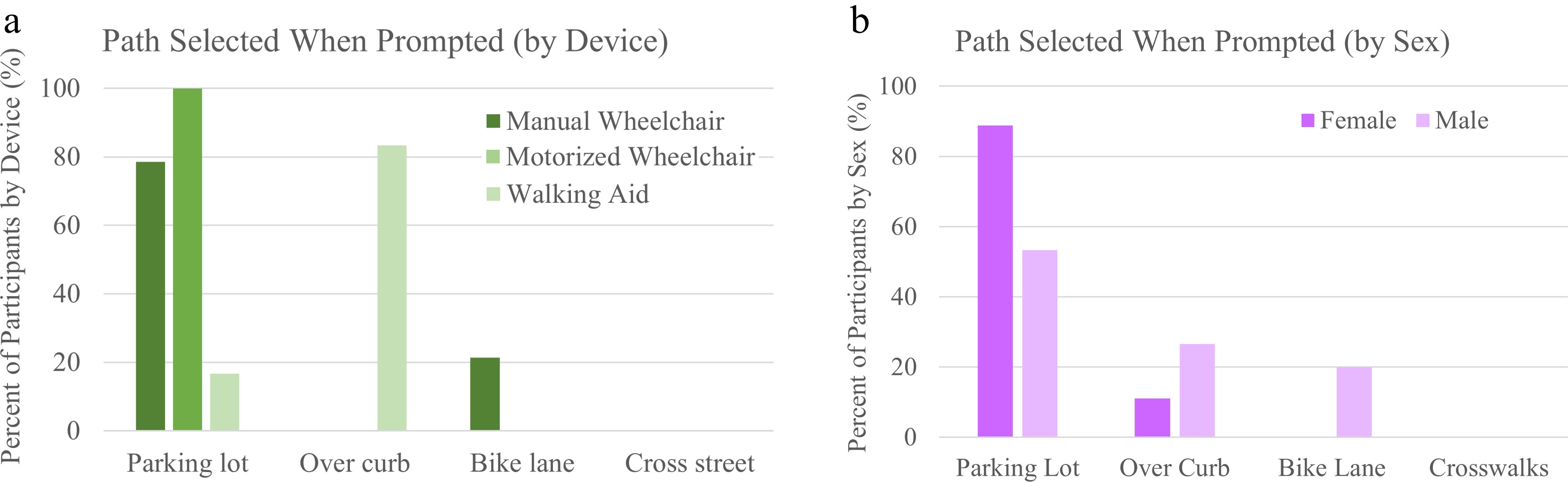

In this scenario, participants were asked to articulate how they would navigate to the PUDO location when faced with an obstacle (e.g., a sidewalk with a curb cut is blocked due to construction). As noted earlier, there were several accessible approaches around the obstacle. The most popular choice of the participants was to go back to the parking lot and access another sidewalk via a curb cut for their route (46% of participants), followed by using the bike lane (29%), then going directly over the curb onto the grass (21%), and one participant chose to use the crosswalks.

Next, the four available accessible paths were pointed out to them and then they were asked the question again. Of those who modified their responses, all of them changed to the parking lot curb cut option. Thereby making the parking lot curb cut the preferred choice (67%), followed by going over the curb (21%), and the bike lane (13%). The crosswalk option was not selected (Fig. 9). Again, participants selected safety over the time they thought it would take to navigate the path. The majority chose the parking lot even though it was longer than the curb or bike lane options due to the ensured safety.

Figure 9.

(a) Path the participant would take prompted by device used. (b) PUDO location access based on sex.

Based on the device (Fig. 9a), 83% of walking aid users chose to go over the curb and were the only device group to do so. The motorized wheelchair users all selected the parking lot option, and 79% of manual wheelchair users also chose the parking lot. The remaining 21% of the manual wheelchair users chose the bike lane and they were the only device group to use the bike lane (Fig. 9). These data indicated that when weighing safety and comfort, walking aid users did not view the barrier of a curb or grass as high as wheelchair users did. Based on sex, women were more likely to stay within the parking lot than men. Eighty-nine percent of females chose the parking lot curb cut option in comparison to 53% of males (Fig. 9b). Only male participants were willing to use the bike lane to get to their destination.

Participants liked the parking lot curb cut option because it was simple and was viewed as the option with the least amount of uncertainty. However, many commented that they did not like that it was a longer distance to get to the PUDO location. For the users who had walking aids, they were comfortable going over the curb and around the cones. They indicated that the parking lot option made them feel rushed. For most wheelchair users, however, going over a curb onto grass was impossible and had a high level of uncertainty, therefore they did not select that option. Wheelchair users, specifically, were worried about slipping or getting stuck in mud/soft grass, snow or ice. Wheelchair users also commented that the bike lane was the quickest and most direct option, but they worried about the proximity to traffic or that they could be hit by passing cars or bikers. Participants liked that the crosswalks were accessible, but they did not select that option because of the further distance from the PUDO location and that it required crossing the street multiple times.

Overall, there are many ways that PwD choose to navigate through the safest and most efficient route. Before they were prompted many participants were more likely to select the more efficient route with some aspects of safety, but upon the presence of a safer route of similar length, they decided to change their response to the safer option. This can be leveraged by AVs as the ideal PUDO location is selected to best avoid obstructions, while also ensuring the safety of the passengers to navigate to and from the PUDO location.

Scenario five

-

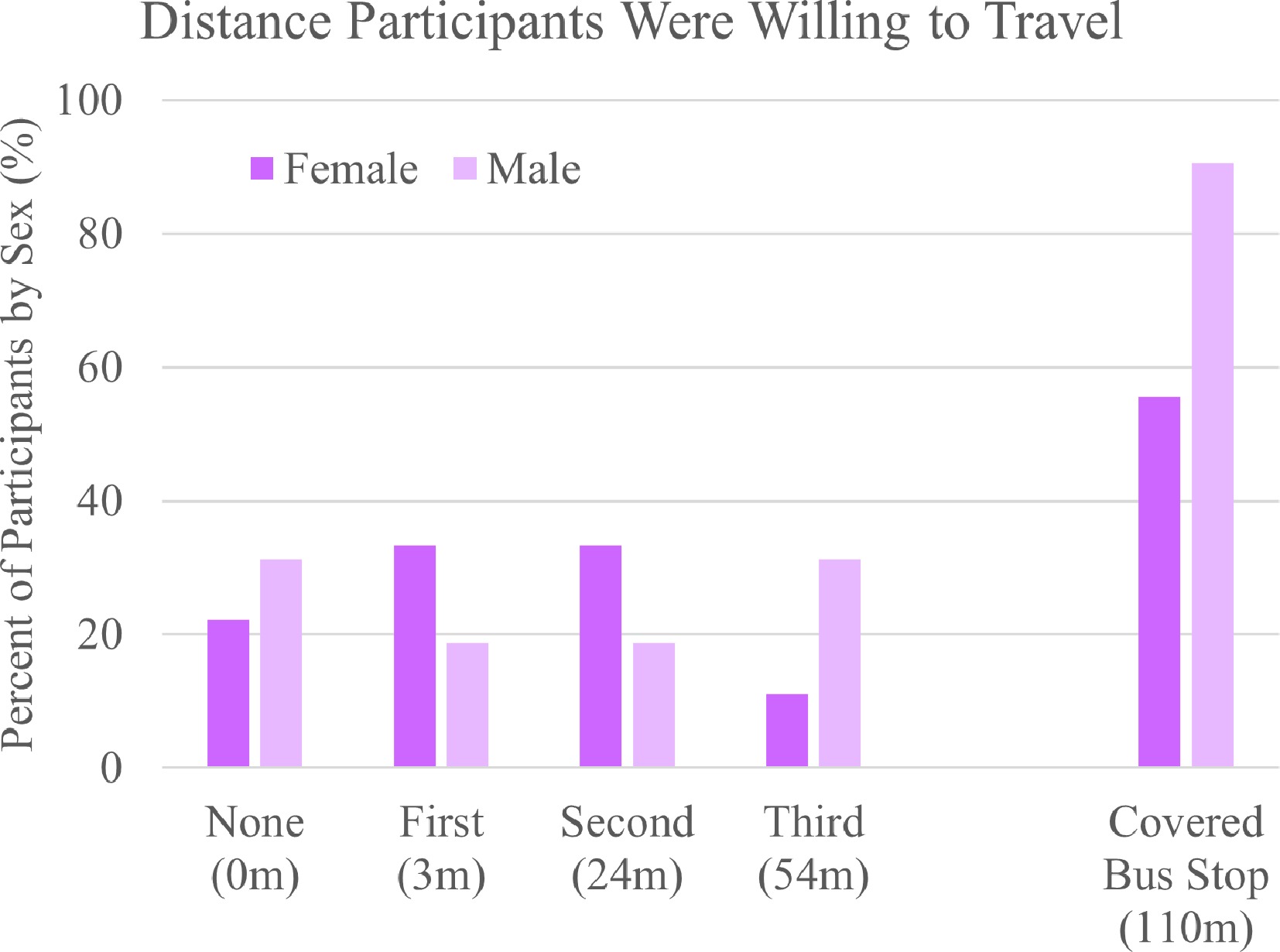

Participants were asked if they needed a place to sit while they were waiting for a vehicle to arrive or if they liked to be near a bench (for themselves or a caregiver) while waiting. Eighty-three percent of walking aid users needed a place to sit while waiting for the vehicle, 30% of manual wheelchair users needed a place to sit or wanted to be near a bench and 0% of motorized wheelchair users needed a place to sit or wait nearby. Many of the manual wheelchair users said they would remain in their chair but would like to wait near a bench. Many participants also reported that they traveled with a caregiver or family and friends who may need a bench or place to sit while waiting. Over half of the participants (52%) traveled with someone who would use a bench while waiting.

Participants were asked how far they would travel to have a bench to wait near or to use, 77% of participants were willing to travel to the bus stop even in bad weather. The bus stop was furthest away (360 ft). In general, about 45% of the participants indicated they were willing to travel to either the first or second stop. Thirty-one percent of male participants were willing to travel to the third bench to have a place to sit down while waiting and only 11% of females were willing to travel that far (Fig. 10). Also, 91% of males would travel to the covered bus stop in bad weather where only 56% of females said they would go that distance.

Figure 10.

Furthest bench participants were willing to travel to and if they were willing to travel to the covered bus stop in bad weather split by gender.

Overall, these results exemplified that for participants safety was the primary motivator for decision-making. Even participants who indicated they did not need a bench to sit by were willing to travel the furthest distance from a PUDO zone to take shelter from bad weather conditions (e.g., rain, snow, extreme heat/cold, etc.). Consequently, this is a positive result in conjunction with scenario one: the data suggest that PUDO zone locations will not have to change based solely on how far they are located from a bench or rest area.

-

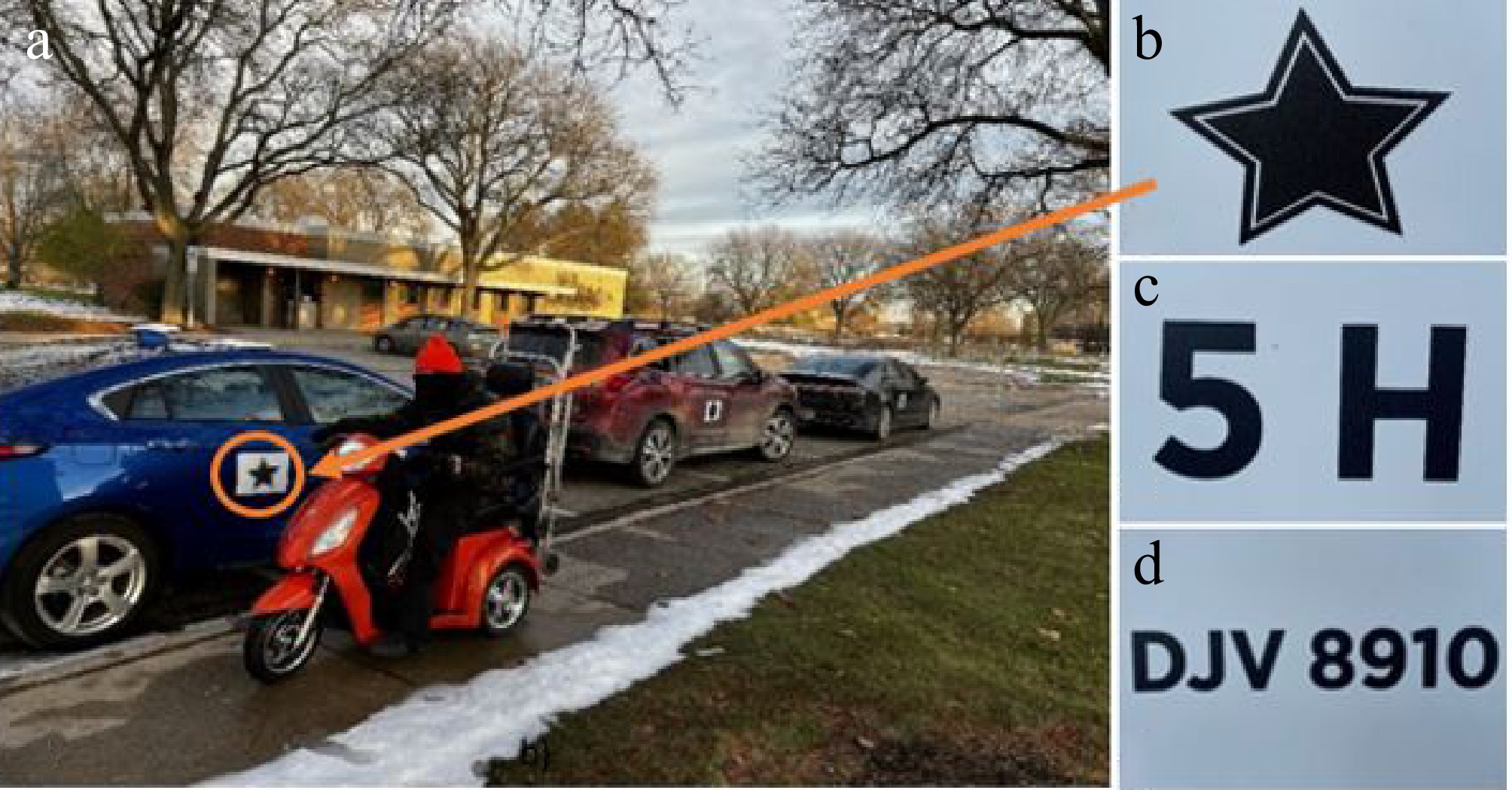

This study had a novel experimental approach in that it used real-world scenarios in conjunction with in-depth assessments and interviews to identify the reasons behind decisions made by PwD related to transportation PUDO zones. In a synthesis of the data collected, the main driving forces that were behind participant choices were safety, comfort, familiarity, and efficiency (Fig. 11).

Safety was the primary concern for most PwD when investigating the PUDO locations and loading/unloading options. Participants consistently chose further PUDO locations from their starting positions, such as the bus stop and the parking lot in scenario one, because they were deemed safer options than the closer PUDO locations. The further locations avoided heavy foot traffic, other vehicle traffic, and had curb cuts available. When faced with high-traffic situations, the majority of participants changed their optimal PUDO location to the parking lot option because of the safety that choice provided. Safety was also an important aspect of vehicle identification. Participants did not want to have to put themselves in an unsafe position to identify their vehicle. For example, if the identifier was on the front or the rear of the vehicle, they may have to navigate close to a curb or even go out into the street to be able to properly identify it. Safety was especially important when choosing a loading method. Specifically, there were concerns with the rear loading method and the possibility of loading from the street leaving them susceptible to being hit by another vehicle. Additionally, concerns with the safety of ramps were also expressed and the potential of rolling off the side of the ramp if the ramp was too narrow, or the inability to propel themselves up the ramp depending on their mobility and strength.

The feeling of comfort, from an emotional and social standpoint, of the participants with regard to the situation was the next most important aspect of the PUDO zone and location. Participants highlighted the importance of not feeling rushed throughout the PUDO process (e.g., the feeling of being in the way, or cars honking their horns because they were too slow when crossing a street) as it could lead to uncomfortable situations or even safety concerns. Weather played an important role in the decision of how far participants were willing to travel to a building or shelter. Bad weather prompted participants to choose further PUDO zones with the option of having a shelter to wait for their ride. Comfort continued to play a role in the loading methods for PwD. Participants reported that rear-loading created a disconnect from other passengers in the vehicle and felt as though they had been valued as less important than the other passengers. Participants also worried about the possibility of getting stuck during the entry to a vehicle requiring assistance from others, making them feel 'more disabled'.

Familiarity with situations was another aspect of PUDO zones that PwD focused on. Previous experiences shaped participants' responses, many indicated that they selected situations that avoided the 'unknown'. Identifying the vehicle could be a stressful event for some PwD, so knowing the make, model, and color of their vehicle could help them be more familiar with the vehicle. Older participants, over 50 years old, preferred to receive a phone call with identifying information because that is what they were more familiar using, while younger participants preferred a text message with the vehicle identifying information. When participants were asked to choose a loading method, ramp versus lift, they typically chose solutions that they had previously used. The unfamiliarity of the built environment also influenced participants' decisions regarding their path selection to access PUDO zones. The conditions or visibility of crosswalks, curb cuts, or the condition of the cement were all factors mentioned, and the unknown conditions caused hesitation with regard to some travel routes.

Those who participated in this research also wanted to be efficient in their travels, but did not want to sacrifice safety, comfort, or familiarity. Indirect travel, such as crossing the street multiple times or having to follow a sidewalk out of the way of the PUDO zone, was not ideal but would be done if safety was a concern for all participants. Although many indicated their willingness to sacrifice efficiency for safety, the most complete PUDO zones would require a safe zone that is also efficient.

In conclusion, the real-world interview data from PwD making real-time decisions and reporting preferences provided information on all aspects of the PUDO process: including determining the way to be notified of an approaching vehicle, how to identify the vehicle, the location to be picked up (in low/high traffic and/or inclement weather situations), and even how to load into the vehicle. This information can be used to inform and influence PUDO zone design, protocol for PUDO vehicles, and even design for PUDO vehicles, which is critical for having accessible transportation for PwD.

Additionally, differences in sex, age, and device used were seen throughout the study and should be taken into account when analyzing the needs of specific groups of PwD. These data and the experiences shared by our participants have provided significant guidance on where PUDO zones should be located, how vehicles should be identified, and the different vehicle access methods along with challenges that users have encountered with their current modes of transportation. Designing the PUDO zones and vehicles to be accessible for the mobility-challenged population will provide an advantage to any ride service or personal vehicle as many of these components are also relevant to the aging population as well as individuals with other disabilities.

-

This study was approved under Michigan State University’s Institutional Review Board (Study #00008428). All participants were guided through the consent process and provided written consent prior to the beginning of the study.

This work was funded by Ford Motor Company.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: investigation: Weidig G, Kanat S, Harth R, Bush TR; data curation: Kanat S, Harth R; conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis: Kanat S, Harth R, Bush TR; project administration, resources, supervision: Guzak K, Bush TR; writing-original draft: Weidig G, Kanat S, Harth R; writing - review and editing: Weidig G, Kanat S, Harth R, Guzak K, Bush TR; funding acquisition: Bush TR. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Weidig G, Kanat S, Harth R, Guzak K, Bush TR. 2025. Understanding needs and challenges with regard to pick-up and drop-off zones for persons with mobility disabilities: assessments via real-life street scenarios. Digital Transportation and Safety 4(3): 161−169 doi: 10.48130/dts-0025-0012

Understanding needs and challenges with regard to pick-up and drop-off zones for persons with mobility disabilities: assessments via real-life street scenarios

- Received: 06 December 2024

- Revised: 08 February 2025

- Accepted: 12 March 2025

- Published online: 28 September 2025

Abstract: Persons with Disabilities (PwD) face numerous barriers when it comes to transportation and have to navigate complex situations to reach vehicles. The goals of this work were to use real-world scenarios and activities related to transportation pick-up/drop-off (PUDO) zones to identify existing barriers, the decision process surrounding those barriers, and how to improve the process. Twenty five assistive device users were presented with five real-world scenarios to understand their decision-making and preferences surrounding PUDO zones. The scenarios revolved around navigation strategies, navigation if there were barriers, the method by which participants could be notified of an incoming vehicle/how they would identify the vehicle, and the preferred loading method/location. Participants preferred PUDO zones that had low traffic or already had infrastructure for loading (like bus stops). When barriers were introduced, the selection of participants was based on safety over proximity. In general, lifts were preferred to ramps for loading, and side-loading was preferred to rear. For vehicle identifiers with regard to potential future 'on call' transportation, participants preferred top or side identifiers to rear. The data collected and presented in this study are critical in informing safe and accessible PUDO protocols, including zones, vehicle identification, and loading.

-

Key words:

- Transportation /

- Accessibility /

- Disability /

- PUDO /

- Pick-up; Drop-off /

- Assistive devices /

- Mobility