-

Autonomous driving (AD) on highways is a critical component of intelligent transportation, significantly contributing to improving road safety, reducing traffic congestion, and enhancing driving efficiency[1−3]. However, the highway environment is complex, including high density of vehicles, large speed variations, and the occurrence of emergencies, all of which demand a safer decision-making ability of AD systems. Lane changing is a quite basic but significant driving task of autonomous vehicles (AVs). Ensuring safety and efficiency in lane-changing scenarios has become a key issue[4−7].

In the domain of lane-changing decision-making of AVs, recent studies have made some progress based on deep reinforcement learning, especially based on Deep Q-Network (DQN), which provides a variety of methods to solve this problem[8−10]. By merging Q-learning and deep neural networks, DQN algorithms can deal with high-dimensional state space issues, thus are widely used in AD decision-making. In a recent study, Clemmons & Jin[11] proposed a Deep Q-Network-based reinforcement learning (RL) algorithm with reward functions to control an AV in an environment with multiple vehicles. The RL algorithm can be easily adapted to different traffic scenarios, and the DQN improves the efficiency of lane-changing. Wang et al.[12] combined DQN with rule-based constraints and achieved safer AD lane change decision-making tasks. In this study, with the setting of state representation and reward function, the AV can behave appropriately in a simulator, and the results outperform other referred methods. Zhang et al.[13] proposed an improved Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN), where the state values are integrated into two neural networks with different parameter update frequencies. The results show that the DDQN improves the convergence speed of the network.

Traditional DQN approaches do however exhibit some limitations when dealing with lane-changing decisions in high-speed scenarios[14,15]. Specifically, during training, DQN performs numerous sample replays that lack prioritization, leading to reduced learning efficiency. Since the DQN algorithm does not focus on critical samples during the experience replay process, this might affect the model’s training stability and the quality of decision-making. In addition, partial reward functions may not adequately reflect the safe driving demands. To address these issues, the Priority Experience Replay (PER) mechanism has been introduced[16−18], which optimizes the sample selection process by assigning each experience sample a priority score, thereby improving the learning efficiency and the stability of DQN. Approaches that integrate DQN with PER have shown superior performance to traditional DQN in various studies, particularly in dealing with lane-changing decisions in high-speed scenarios[19−22]. Yuan et al.[19] divides the reward function into three subfunctions, aiming for higher driving speed, fewer lane changes, and collision avoidance. However, the configuration of the reward function is somewhat one-sided, as it does not take into account potential dangers during lane changes, such as being too close to the vehicle in front. These factors will be considered in our study. Therefore, designing appropriate reward functions and integrating critical safety constraints are significant in improving the safety of lane-changing decisions. In this study, we design a multi-reward structure that considers driving speed, overtaking, and lane-changing behaviors, allowing for the enhancement of the safety of lane changes.

-

In RL, the design of state space and action space directly affects the learning effect and behavioral outcomes of intelligent agents. This study details the design of the state space and action space as follows.

Definition of state space

-

The state space in RL contains critical information about the current environment, which is pivotal for decision-making in AVs. Here, the highway lane-changing problems are formulated as Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), with the state space consisting of 14 different states under the current environmental conditions, respectively:

1 - The speed of the AV right before lane change, Ve;

2 - The acceleration of the AV, ae;

3 - The forward angle of the AV,

$\theta $ 4 - The distance to the preceding vehicle, d;

5 - The speed of the prior vehicle, Vp;

6 - The acceleration of the prior vehicle, ap;

7 - The distance to the prior vehicle in the left lane, dl;

8 - The speed of the prior vehicle in the left lane, Vpl;

9 - The acceleration of the prior vehicle in the left lane, apl;

10 - The distance to the prior vehicle in the right lane, dr;

11 - The speed of the prior vehicle in the right lane, Vpr;

12 - The acceleration of the prior vehicle in the right lane, apr;

13 - The vehicle density in lane i, Di;

14 - The average speed in lane i,

$ V_i^{avg} $ These states provide a comprehensive description of the current traffic environment and offer sufficient information for intelligent agents to make decisions.

Definition of action space

-

The action space defines the actions that an intelligent agent (IA) can take, which directly influence IA’s behavioral choices and decision-making. This study designs the action space to contain five basic actions and each maps to a distinct value while enabling the IA to make corresponding decisions based on the environment states.

Specifically, the action space is defined as follows:

0 - Maintaining current lane and speed;

1 - Changing lanes to the left;

2 - Changing lanes to the right;

3 - Acceleration;

4 - Deceleration.

By designing five basic actions, the IA can gain a sufficient set of choices, which allows it to make flexible decisions based on the current environment states, ultimately achieving safe and efficient AD lane changes.

Design and optimization of the reward function

-

Reward functions play a crucial role in RL, and directly influence the learning and behaviors of IAs. In our study, a preliminary reward function has been designed to promote the efficiency and comfort of the AV. The reward function includes efficiency reward and comfort reward. Meanwhile, to improve the safety of the AV, this study has added rewards of collision avoidance and lane changes in safety distance to optimize the preliminary reward function.

Design of the preliminary reward function

-

The preliminary reward function has been set up with two components, namely efficiency reward and comfort reward.

Efficiency reward

-

Aiming to increase the efficiency of AD, thereby promoting smooth traffic flow. The definition is shown as follows:

$ {r_e} = \left\{ \begin{gathered} \dfrac{{{V_e} - {V_{\min }}}}{{{V_{\max }} - {V_{\min }}}},{\text{ if }}{V_e} \lt {V_{\min }} \\ \dfrac{{{V_{\max }} - {V_e}}}{{{V_{\max }} - {V_{\min }}}},{\text{ if }}{V_e} \gt {V_{\max }} \\ \dfrac{{{V_e}}}{{{V_{\max }}}},{\text{ other}} \\ \end{gathered} \right. $ (1) where, Ve is defined as the mentioned speed right before lane change, Vmax denotes the maximum speed limit, Vmin denotes the minimum speed limit.

According to the efficiency reward function, a negative value will be obtained if the speed of the AV exceeds the maximum speed limit or falls below the minimum speed limit. Conversely, when the speed is between the maximum and minimum speed limits, the reward value will increase with the growth of the speed, reaching a maximum value of 1 at the maximum speed limit. This aims to incentivize the AV to drive at a speed close to, but not exceeding, the maximum speed limit, thereby improving driving efficiency under the premise of ensuring safety.

Comfort reward

-

Aiming to improve passengers’ comfort by avoiding overly aggressive acceleration or deceleration. The definition is as follows:

$ {r_{com}} = \left\{ \begin{gathered} 1,{\text{ if }}{a_{cc}} \lt 0.6 \\ - 1,{\text{ if }}{a_{cc}} \geqslant 0.6 \\ \end{gathered} \right. $ (2) where, acc denotes the rate of acceleration change for AVs.

According to the comfort reward function, a positive value is obtained to improve comfort if the rate of acceleration change is lower than 0.6 m/s3; conversely, a negative value is obtained to penalize excessive acceleration changes if the change rate is greater than or equal to 0.6 m/s3.

Therefore, the complete formula of the reward function r is defined as follows, where both the efficiency reward and the comfort reward are weighted equally at 1:

$ r = {r_e} + {r_{com}} $ (3) Design of the safety reward function

-

To enhance the safety of AVs, this study defines collision avoidance reward and safe distance reward between the AV and the prior vehicle after a lane change, to form the safety constraints.

The collision avoidance reward is specifically defined as follows:

$ {r_c} = \left\{ \begin{gathered} - 10,{\text{ collision}} \\ 0,{\text{ no}} {\text{collison}} \\ \end{gathered} \right. $ (4) When a collision occurs, a large negative value is obtained to penalize the unsafe behavior; while no collision occurs, the penalty is zero. Such a setup helps the model learn that collisions are unacceptable and effectively avoids such risky behaviors by providing strong negative feedback.

The safety distance reward after a lane change is specifically defined as follows:

$ {r_{cld}} = \left\{ \begin{gathered} - 5,{\text{ if }}{V_e} \geqslant {d_L} \\ 2,{\text{ if }}{V_e} \lt {d_L} \\ \end{gathered} \right. $ (5) where, dL denotes the distance between the AV and the prior vehicle after lane changes.

According to the safety distance reward function, if the distance between the AV and the prior vehicle after the lane change is less than the safe distance traveled in one second at the current speed, it is considered as an unsafe lane change that could potentially lead to danger, and an extremely low negative value for potential collisions is obtained; if the distance is greater than the safe distance traveled in one second at the current speed, it is considered as a safe lane change and a positive reward is obtained. But if the reward value when Ve < dl for a safe lane change is too high, the model may excessively prioritize lane changes, thereby increasing driving risks. Therefore, we have set this reward to 2.

The comprehensive reward function after optimization is defined as follows:

$ r = \left\{ \begin{gathered} {r_c},{\text{ collision}} \\ {r_e} + {r_{com}} + {r_{cld}},{\text{ no}} {\text{collision}} \\ \end{gathered} \right. $ (6) Specifically, if a collision occurs in the corresponding state, the final reward function is the collision avoidance reward. If no collision occurs, the final reward function is the sum of the efficiency reward, the comfort reward, and the safety distance reward after lane change, and their reward weights are all set as 1. Taking safety, efficiency, and comfort into account, the entire reward function promotes appropriate decision-making of AVs in traffic scenarios, leading to safe and efficient driving behaviors.

It is worth noting that the parameter tuning in Eqs (1)−(6) has undergone adequate experiments and self-learning iterations, ultimately achieving optimal strategy.

-

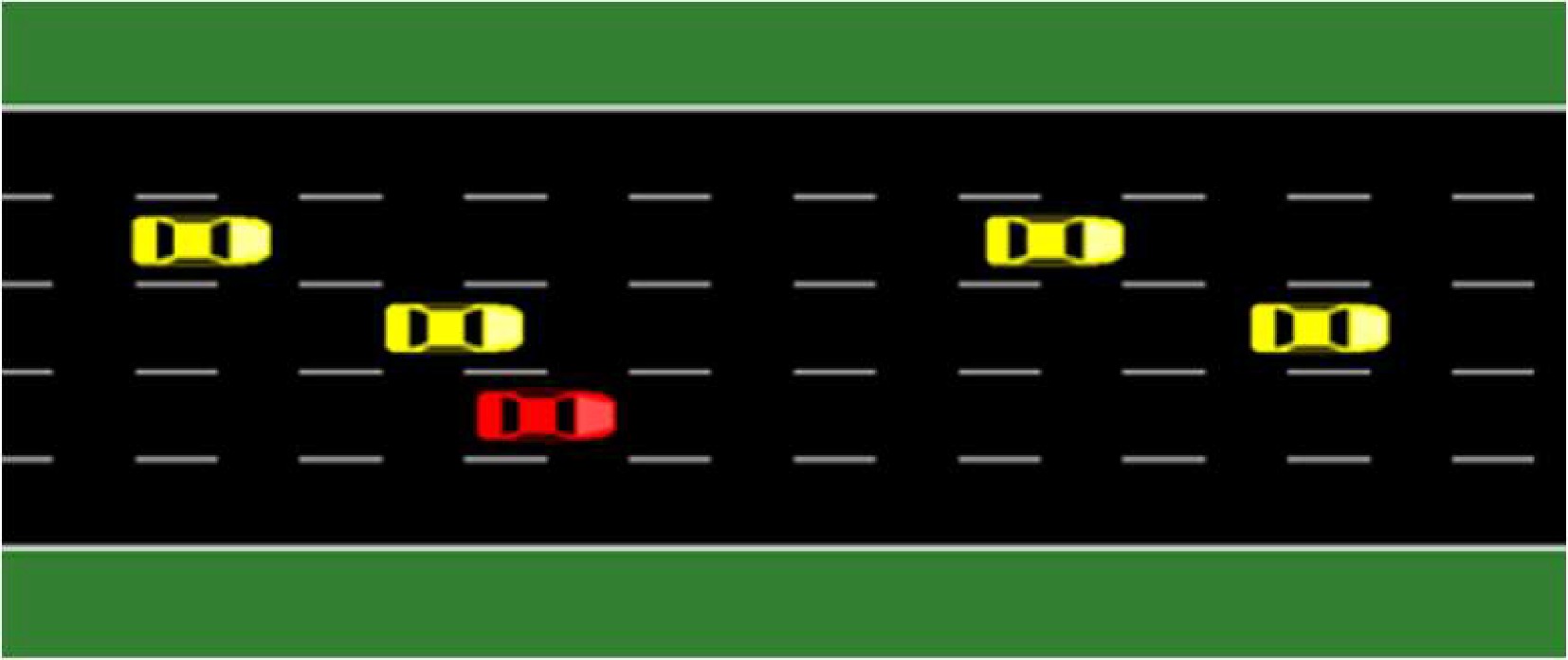

In our project, we use the Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO) platform[23] to simulate lane changing in highway dense traffic scenarios, as shown in Fig 1. The red car is the host AV. In this paper, we designed a customized RL Gym environment to integrate the SUMO simulator with the RL framework. This environment is not only able to interact with the SUMO simulator, obtaining state information and executing actions, but also to compute reward functions. Through such an environment, we can integrate the driving behaviors of AVs into the RL framework and enable the optimization and training of driving strategies.

To construct the customized Gym environment, the following activities have been performed:

1. Optimization of the real-time interaction performance: Optimization of the interaction with the SUMO simulator aims to improve the responsiveness and stability of the simulation environment, thus more effectively supporting the training process of the RL algorithms.

2. Integration of enhanced visualization function: a real-time visualization function has been integrated to enable to observe the driving states of AVs and their interaction with other vehicles.

The simulation system was designed for lane changing on highways, using a combination of SUMO and an RL Gym environment. The SUMO environment is set up as follows:

1. Road and lane design: Three consecutive road segments were designed, denoted as E0, E1, and E2, each of which consists of five lanes. Considering traffic safety, emergency stopping strips were set up on each side of the road with green marks to cope with emergencies. The length of road E0 and E1 was set at 1,000 m, while the length of E2 was set at 8,000 m. Such a design considers the functions and traffic flow of different roads, allowing simulation of a variety of traffic scenarios on roads that span different lengths.

2. Vehicle setup: The Reinforcement Learning Intelligent Agent (RLIA) is designated as an AV, named as 'av_0'. Here are the critical parameters that have been taken into account for the configuration of the AV:

(1) Departure lane and initial position: To simulate the real traffic scenario, the departure lane and initial position of the AV are set randomly while ensuring its departure lane is free to avoid initial traffic congestion.

(2) Speed limit: The maximum speed of the AV is set at 120 km/h, and the minimum speed is set at 90 km/h. Such a speed range promotes a smooth and safe flow of high-speed traffic.

(3) Acceleration and deceleration limits: To ensure the smooth driving behaviors of the AV, its maximum acceleration is limited to 2.6 m/s², and its maximum deceleration is limited to ~9 m/s², allowing it to adapt to varying speeds in different traffic situations.

For the background vehicles, a slow traffic flow lasting a total of 3,600 s was set up from the road segments E0 to E2, with a total number of 2,100 vehicles. Such a setting can enhance the realism of traffic simulation, and consider the mix of background vehicles with varying speeds on the road. By reasonably setting up the AVs, the background traffic flow, and the highway dense traffic scenario, we can provide a reliable numerical simulation basis for the subsequent experiments.

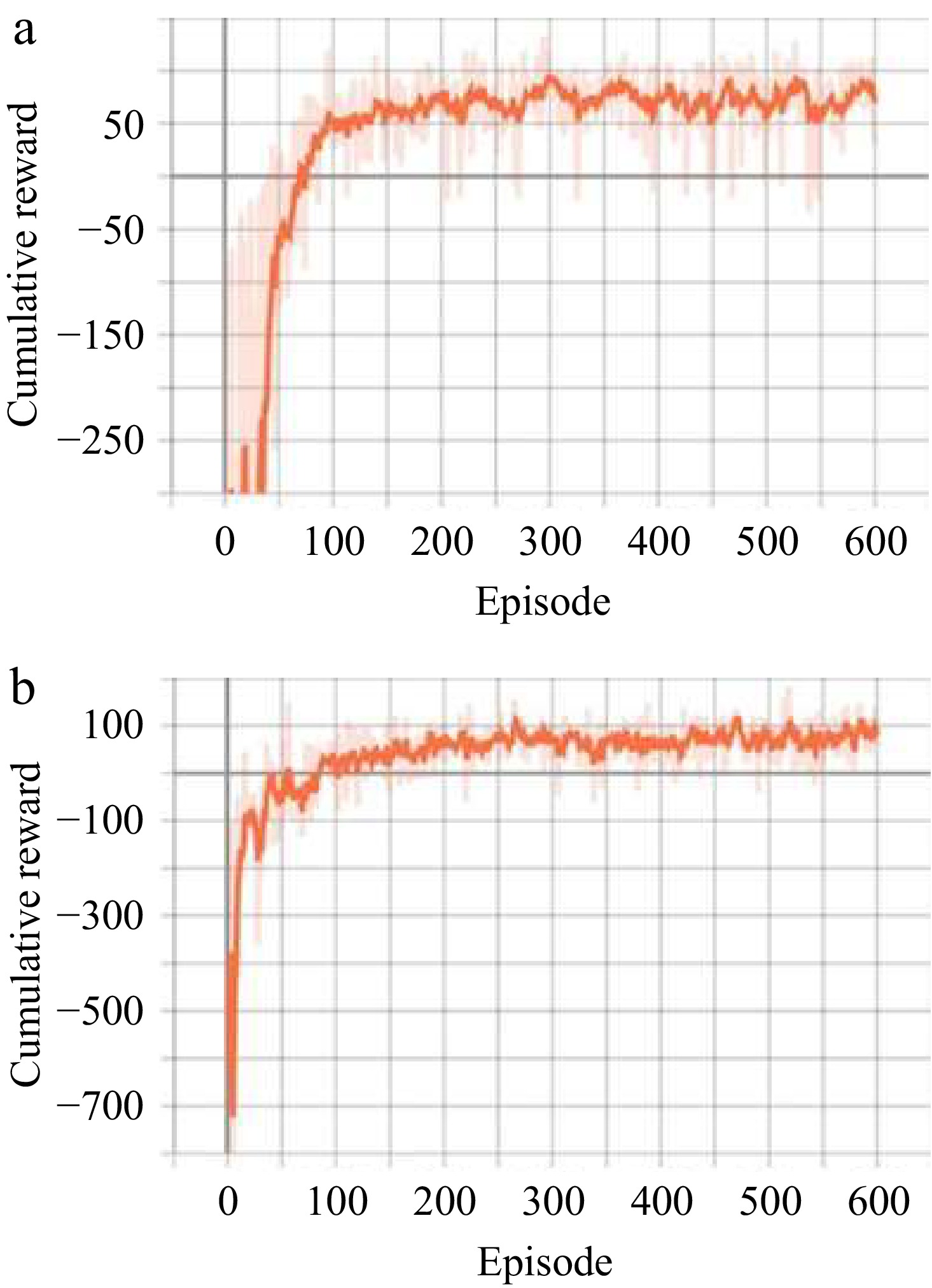

In the experiment, we compare the cumulative reward value, the unsafe lane change rate, collision frequency, and the total number of collisions in each training episode, and the total number of collisions in 600 episodes, before and after integrating the safety reward.

The cumulative reward values for the 600 training episodes before and after integrating the safety reward are shown in Fig 2. Figure 2a shows the cumulative reward values changing along with per training episode without the safety reward function, and Fig. 2b shows the cumulative reward values training episode after integrating the safe reward function. As the number of training episodes increases, the cumulative reward values in both conditions shows an upward trend and eventually stabilize. Specifically, after integrating the safety reward, the cumulative reward value stabilizes at approximately 100, which is significantly higher than that without the safe reward function. Additionally, the training process with the safe reward function integrated converges more rapidly and reaches a stable state more quickly.

Figure 2.

Cumulative reward values. (a) Without safe reward function. (b) Safe reward function integrated.

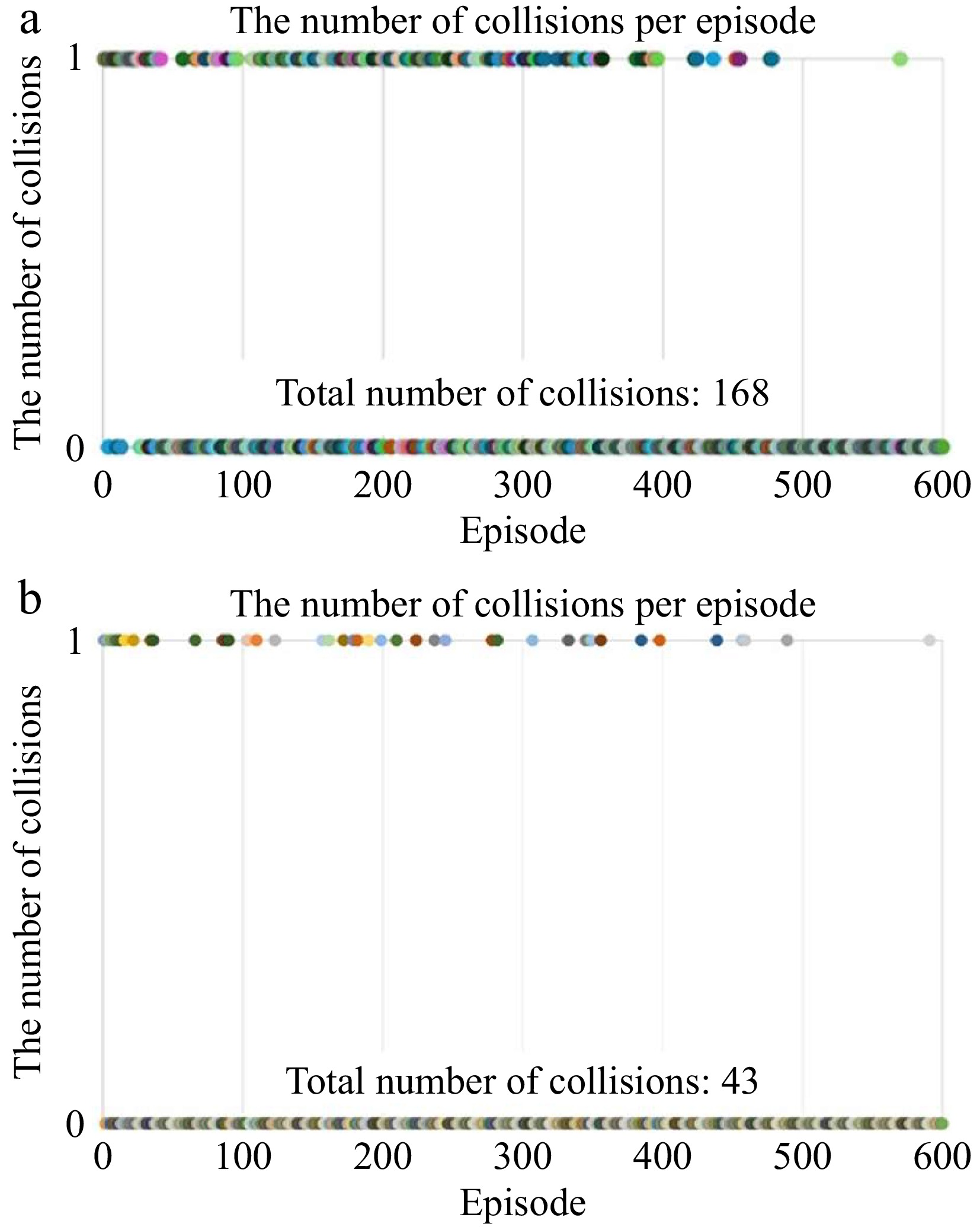

The number of collisions per episode and the total number of collisions in 600 training episodes before and after integrating the safety reward are shown in Fig 3. Figure 3a shows the number of collisions per episode and the total number of collisions in 600 episodes without the safety reward function. Figure 3b shows the number of collisions per episode and the total number of collisions in 600 episodes after integrating the safety reward function.

Figure 3.

Number of collisions per episode and cumulative collisions for 600 episodes. (a) Without safe reward function. (b) Safe reward function integrated.

An in-depth analysis of the experimental results shows that integrating safety rewards in the RL training of AVs significantly reduces collisions. Specifically, in the 600 training episodes without the safety rewards, a total number of 168 collisions occurred. However, when safety rewards were introduced, this number was significantly reduced to 43. This significant downward trend demonstrates that the safety reward function plays a crucial role in reducing collisions.

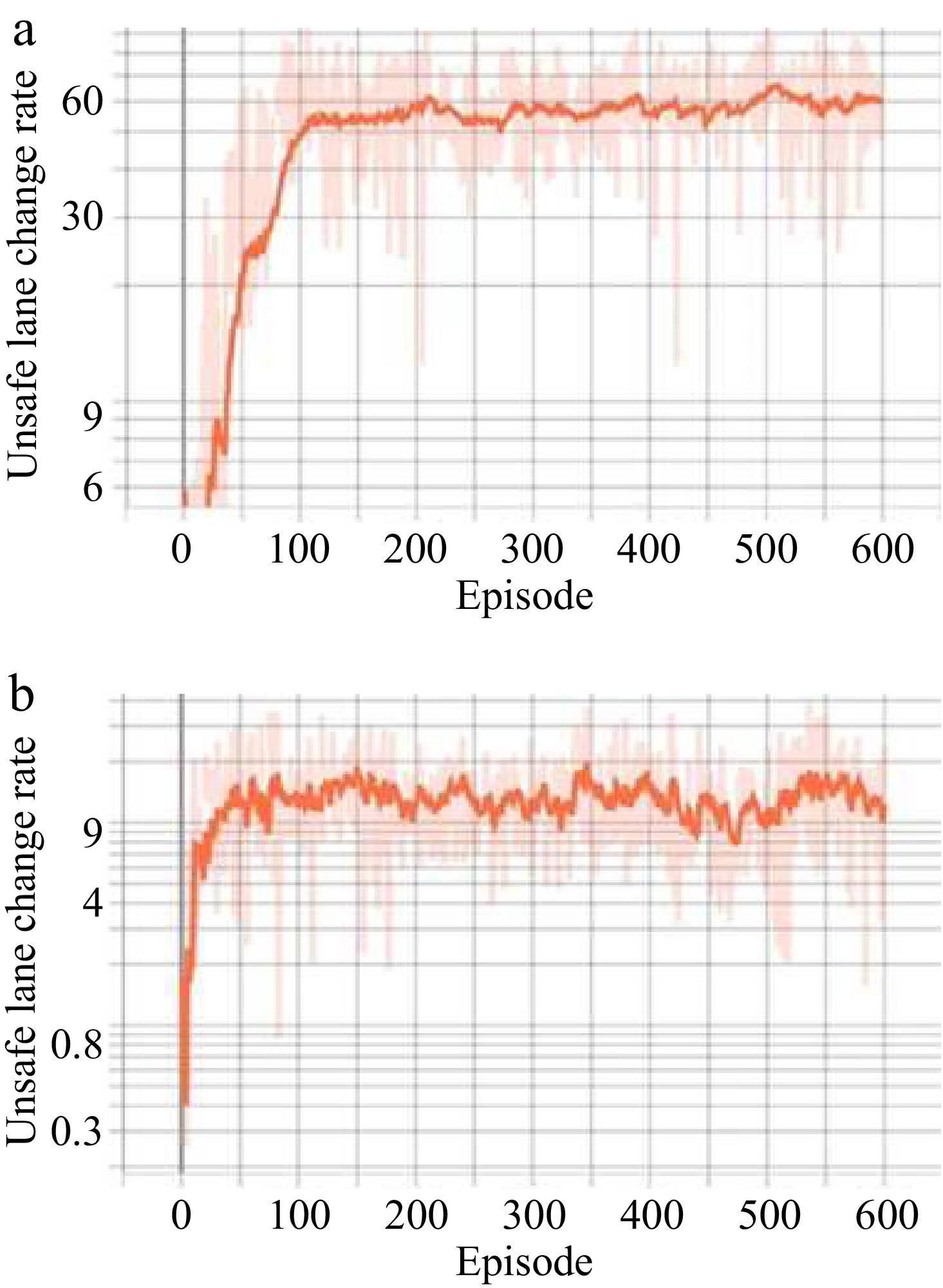

The unsafe lane-change rate changing along with episodes before and after integrating the safety reward is shown in Fig 4. Figure 4a shows the unsafe lane-change rate changing along with episodes without the safety reward function, and Fig. 4b shows the unsafe lane-change rate changing along with episodes after integrating the safety reward function.

Figure 4.

Unsafe lane change rate per episode. (a) Without safe reward function. (b) Safe reward function integrated

According to the results of Fig 4, unsafe lane-changing behavior was also effectively mitigated by our approach. After the integration of the safety reward function, the rate of unsafe lane changes per episode dropped from approximately 60% to 10%, namely about a 50% reduction was shown. This positive change further confirms the outstanding performance of our approach in improving AVs safety.

To further demonstrate the advanced performance of our approach, a comparison is carried out between our model and other three related models, namely the Lane Change Decision model (called LCD)[21], the Bayesian RL integrated randomized prior function model (called BRL-RPF)[22], and the LC2013 model provided by SUMO[24]. We compared the average lane-change (LC) duration, unsafe LC rate, and LC collision number of the three models during 600 training episodes. The best results are shown as bold text in Table 1.

Table 1. Model performance comparison.

Approaches Ave. LC duration (s)↓ Unsafe LC rate ↓ #LC collision ↓ LC2013 8.3 37.89% 115 LCD 3.4 12.91% 41 BRL-RPF 6.7 9.8% 40 Our model 2.7 9.4% 43 Bold values indicate the best performance in each column. As illustrated by Table 1, our model holds the shortest average LC duration and lowest unsafe LC rate, which outperforms the other three referred models. Additionally, the LC collision number of our model is nearly twice less than that of LC2013 and almost equivalent to that of LCD and BRL-RPF models. In a nutshell, our model has better performance compared with the existing related models.

-

Our study proposes a dense RL approach based on the safety reward function to improve the safety of AVs in complex dense traffic highway environments. Specifically, the safety reward function consists of a collision penalty and a safety distance reward between the AV and the prior vehicle after changing lanes. Moreover, the customized RL Gym experimental simulation is developed. Experimental simulation results show that by developing and integrating the safety reward function, the collision rate and unsafe lane changing rate of AVs are significantly reduced. Namely, by comparing the number of collisions and the rate of unsafe lane changes per episode, before and after integrating the safety reward function, it is concluded that the developed safety reward function can significantly improve the safety of lane changes of AVs, which demonstrates the effectiveness of our proposed approach.

Despite significant advancements of the proposed lane change approach attested within a simulation environment, several challenges remain when transferring our approach to real-world applications. One of the primary concerns is that the driving scenarios generated in simulations are limited and do not fully capture the extreme situations that AVs may encounter in the real world, such as long-scale contrast, high-scale cover, strong illumination, or adverse weather conditions (so-called corner cases). This lack of critical scenarios can result in suboptimal performance during real-world operations, potentially leading to collisions. To address this issue, future research will incorporate multi-modal data, utilizing data from various sensors such as radar, lidar, and cameras to enhance the realism and breadth of the simulation environment. Vehicle parameters, including maximum speed and acceleration, will be adjusted to simulate slippery road conditions during rain or snow. The safety distance parameters within the car-following model will be modified to simulate driving behaviors under different lighting conditions. A dedicated dataset of extreme scenarios will be created to train the model's adaptability to diverse scenarios and corner cases, thereby improving its robustness.

Additionally, AVs need to interact with other road users, such as human-driven vehicles and pedestrians. Such interactions among heterogeneous road users can also affect the generalization of our approach. The unpredictable behavior of human drivers and pedestrians, including their tendency to violate traffic rules significantly increases road safety risks and poses challenges to the accuracy and safety of lane-changing decisions. To address this, AVs need to adopt more conservative lane-changing strategies, such as delaying or abandoning lane changes. Furthermore, practical considerations necessitate a differentiated design of reward function, prioritizing pedestrian safety by assigning different rewards for collisions with vehicles vs collisions with pedestrians.

Therefore, future work would explore integrating heterogeneous interaction rules into our approach, and constructing more complicated scenarios, such as corner cases, for training and validating our approach, to enhance the adaptability and safety of our approach when applied in the real world.

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52402493), Heilongjiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LH2024E059), and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (HIT.NSFJG202426).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liang C; data collection: Ran Q, Liu P; analysis and interpretation of results: Ran Q, Liu P; draft manuscript preparation: Liang C, Ran Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are confidential.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ran Q, Liang C, Liu P. 2025. A safe lane-changing strategy for autonomous vehicles based on deep Q-networks and prioritized experience replay. Digital Transportation and Safety 4(3): 170−174 doi: 10.48130/dts-0025-0013

A safe lane-changing strategy for autonomous vehicles based on deep Q-networks and prioritized experience replay

- Received: 05 September 2024

- Revised: 20 February 2025

- Accepted: 09 March 2025

- Published online: 28 September 2025

Abstract: Autonomous vehicles (AVs) still face many safety issues in lane change scenarios in dense highway traffic. This paper proposes a dense reinforcement learning approach based on deep Q-Network (DQN) and prioritized experience replay (PER), aimed at enhancing the lane change safety of AVs in dense highway traffic. By developing safety constraints and designing safety-first multi-dimensional reward functions, the proposed approach significantly improves lane-change safety in dense highway traffic. Furthermore, the conducted numerical simulation experiments demonstrate the outstanding performance of our approach.