-

Pork is one of the most popular and significant sources of protein that people consume[1]. Fresh meat must have improved quality, flavor, and nutritional value to increase production capacity and match customer quality demands[2]. Among these, flavor, which relates to the consumer's whole sensory perception, including taste and smell, is an important feature in evaluating the quality of pork[3]. Non-volatile flavor compounds create forms to excite taste neurons, whereas volatile flavor molecules produce the latter to activate olfactory nerves. Variety[4], nutrition regulation[5], feeding management[6], and slaughter procedure[7] are all elements that influence pork flavor. Changing the level of calories, protein, fat, and antioxidant chemicals in feed could have an impact on nutrient content and, as a result, the overall flavor of pork[8]. It is now a research center in the meat industry. The flavor of meat often has a potential connection with its nutritional value[9]. In recent times, there has been a surge in consumer demand for nutritious and good-quality pork meat[10]. The nutritional value of pork may be closely related to the nutritional management of pigs before slaughter, and many studies have confirmed that changing the composition of feed improves the nutritional quality of pork[11]. The direct addition of polysaccharides, vitamins, and certain plant extracts to feed has been proven to improve the nutritional quality of pork by improving the nutritional status of pigs[12,13].

Feeding fermented feed is an emerging nutritional regulation method for pigs[14]. There are microbial cell proteins, bioactive small peptides, amino acids, active probiotics, and compound enzymes in fermented feed[15]. These substances may cause changes in the proportion of amino acids, fatty acids, and nucleotides in muscle after being metabolized by pigs. Adding 8% fermented maize and soybean meal to the standard diet could substantially boost the concentrations of inosinic acid, ω-6, and ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in fattened pork, therefore increasing the flavor and nutritional value[16]. However, compared to the currently most widely used solid fermented feed, wet fermented feed (WFF) can stimulate the appetite of pigs, improve feed digestibility, and promote pig growth[17,18]. Additionally, wet fermented feed reduces feed dust and inhibits the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella, thereby lowering disease incidence[19]. Therefore, its application in pig farming has been on the rise in recent years. However, most current research focuses on the effects of wet fermented feed on the growth status and intestinal function of finishing pigs[17,20,21], while studies on the impact of wet fermented feed on the flavor and nutritional value of finishing pigs remain limited.

Hence, in this study, Duroc × Landrace × Yorkshire pigs were fed both ordinary feed (OF) and WFF. It was hypothesized that feeding WFF can serve as a nutritional regulation tool for pigs, increasing the accumulation of flavor substances in muscles. By comparing the flavor and nutritional value of the two types of pork, the influence of WFF on the pork was explored. This research will help improve the quality of pork during the fattening phase in the feed dimension.

-

Duroc × Landrace × Yorkshire pigs were provided by Han Shiwei Food Group (Ma'anshan, Anhui, China), and fed with ordinary feed (soybean meal : corn : bran = 6.5:1.5:2, OF) and fermented feed (containing 10% OF fermented by Bacillus subtilis and lactic acid bacteria, WFF) from Anhui Tianbang Biological Company (Ma'anshan, Anhui, China). Nucleotide standards: cytosine nucleotides (CMP), guanine nucleotides (GMP), adenine nucleotides (AMP), hypoxanthine nucleotides (IMP), inosine (In), and hypoxanthine (Hx) were purchased from Maibo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). The fatty acid mixed standard products were purchased from Anpu Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Other chemicals were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA).

Feeding management and sample collection

-

Initially, 240 healthy Duroc × Landrace × Yorkshire pigs aged 115 d were randomly separated into two groups with three replications (40 pigs per replication), with no significant difference in initial body weight (approximately 45 kg). Pigs in the control group were fed with OF, whereas those in the experimental group were fed WFF. All pigs were allowed to eat and drink water during the trial. The regulations of the company were followed for daily management and immunization. They were fed four times a day and raised until they were 175 d old.

Slaughter and sampling was carried out at Shifenweidao Food Co., Ltd. (Huai'an, Jiangsu, China). In each repetition, 20 pigs in each group were randomly selected and fasted for 12 h. Pigs were stunned using high concentrations of carbon dioxide before humane slaughter. The loin (30 g) was placed in a frozen storage tube immediately after slaughter, then it was kept in an ultra-low-temperature refrigerator at −80 °C to determine the taste and odor compounds.

Determination of free amino acid content

-

The method of Zhang et al.[22] with minor changes was used. Chopped loin (4 g) was added to 20 mL of sulfosalicylic acid solution (30 mg/mL), and homogenized three times in an ice bath for 20 s each. Then, a high-speed freezing centrifuge (Avanti J-C, Beckman Coulter, USA) was used to centrifuge the supernatant for 15 min (4 °C, 10,000 × g), 2 mL of n-hexane was added, and fully shaken. After static stratification, the lower water phase was filtered through a 0.22 μm aqueous phase membrane. An automatic amino acid analyzer (SD33D, Shenzhen Sykam Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) was used to evaluate the relative amounts of various free amino acids.

Determination of flavor nucleotide content

-

HPLC was used to determine the flavor nucleotide content, which was slightly modified from the method of Zou et al.[23]. Minced loin (4 g) was added to 20 mL of a 5% perchloric acid solution, and homogenized three times in an ice bath. Then, the supernantant was centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C, and 10,000 × g. The sediment was centrifuged again with 10 mL of a 5% perchloric acid solution. The supernatant was combined at a pH of 4.5, and filtered through a 0.22 μm aqueous phase filter membrane into a 1 mL brown liquid phase screw vial at 4 °C.

For detection, a high-performance liquid chromatograph (Agilent, USA) with an ultraviolet detector and a C18 chromatographic column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) was utilized. The mobile phases were potassium dihydrogen phosphate (0.05 M, pH = 4.5), and methanol, and the column temperature was 30 °C. The following elution technique must be followed: with a flow rate of 1 mL/min and a sample injection volume of 10 μL, the potassium dihydrogen phosphate buffer dips to 85% for 5 min after 15 min, and then climbs to 98% for 9 min after 21 min.

Determination of fatty acid composition

-

The fatty acid profile of the samples was evaluated according to the modified method of Li et al.[24]. Minced loin (6 g) was added to 30 mL of chloroform-methanol solution (2:1, V/V), homogenized three times at 8,000 r/min, and placed in a fume hood for 24 h. The samples were filtered, 8 mL of physiological saline (0.9%) was added to the filtrate, and centrifuged for 20 min at 4 °C (5,000 r/min). A nitrogen-blowing device (N-EVAP-12, Shanghai Ample Scientific Device Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was used to dry the lower organic phase liquid.

For saponification and methylation, the approach of Chen et al.[25] was used. 0.1 g of grease was placed in a 50 mL centrifuge tube, 4 mL of sodium hydroxide-methanol solution (0.5 M) was added, and the tube was heated for 10 min in a 70 °C water bath. Then 5 mL of boron trifluoro-methanol solution (14%), 7 mL of n-hexane, and 10 mL of saturated sodium chloride solution were added. The samples were whirled for 15 s and centrifuged for 5 min (15,000 × g, 4 °C), then the supernatant was sucked into the injection bottle using the 0.22 μm organic filter membrane.

The following are the gas chromatography working conditions: injector temperature was set to 270 °C, and the detector temperature was set to 280 °C. The strong polar stationary phase of poly(dicyanopropylsiloxane) siloxane (100 m × 0.25 mm, 0.20 μm) was used. The initial temperature during detection was 100 °C and lasted 13 min. The temperature was raised to 180 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min and held for 6 min, then to 200 °C at a heating rate of 1 °C/min and held for 20 min, then to 230 °C at a heating rate of 4 °C/min and held for 10.5 min. The injection volume and flow rate were 1.0 μL and 1.0 mL/min, respectively. The external standard was a mixed standard solution of 37 fatty acids.

Determination of volatile flavor substances

E-nose analysis

-

The method of Bassey et al.[26] (with slight modifications) was used to evaluate the flavor profile of the samples. Minced meat (5 g) was put into a headspace container, sealed, and cooked in a 50 °C water bath for 30 min before balancing it at room temperature for 30 min. The data acquisition period was set to 120 s, and the cleaning time to 60 s on the electronic nose detector to absorb the headspace gas.

Gas Chromatography-Ion Migration Spectroscopy analysis

-

The samples were determined using the method of Zhou et al.[3] by GC-IMS with little adjustment. A 20-mL headspace bottle was filled with 3 g of minced meat. After sealing, Gas Chromatography-Ion Migration Spectroscopy (Flavour Spec®, Gesellschaft für Analytis cheSensor Systeme mbH [G.A.S.], Dortmund, Germany) was used to examine the entire flavor profile.

Statistical analysis

-

A completely randomized design with two feeding groups (WFF and OF), and three replicates was adopted. The hypothesis was used to evaluate the significance of the difference between distinct groups, with p < 0.05 being significant. A mixed model was designed to evaluate differences in pork flavor, including electronic nose and GC-IMS data. Feed types (OF and WFF) and flavor substances were used as fixed effects, while loin, slaughter batches, and repeated measurements were used as random effects. The design concept of the content model for free amino acids, free fatty acids, and flavor nucleotides was similar to the flavor evaluation model, with loin, slaughter batches, and repeated measurements as random effects. In the free amino acid content model, the types of amino acids, feed types (OF and WFF), and their interactions were used as fixed effects. In the free fatty acid content model, the types of fatty acids, feed types (OF and WFF), and their interactions were fixed terms. Nucleotide types, feed types (OF and WFF), and their interactions serve as fixed effects for the flavor nucleotide content model. The data were analyzed by SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., USA). The data were presented as mean ± standard error (SEM). Post-hoc tests were carried out using Duncan's multiple-range analysis. Data visualization was performed by GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). The results of the electronic nose measurement were analyzed by PCA using its matching Win Muster software, and the radar chart was drawn in Excel. For qualitative and analytical examination of volatile taste compounds, Library Search software (with built-in NIST 2014 database and IMS database) and Laboratory Analytical Viewer (LAV) were utilized, and the built-in plug-in of LAV was employed to develop volatile compound fingerprints.

-

Some essential amino acids like glutamic acid, aspartic acid, phenylalanine, alanine, glycine, and tyrosine are considered delectable amino acids in meat because of their distinct flavor[27]. Their composition and concentration have a direct impact on the flavor of meat. Aside from the wonderful flavor, the sweetness of meat is an important taste in forming the meat flavor. Glycine, threonine, and lysine are sweet amino acids that contribute to sweetness[28]. Table 1 shows the relative concentration of free amino acids in this investigation. The relative concentration of taste amino acids was considerably higher in the WFF group than in the OF group, showing that pork from pigs fed fermented feed was more palatable in general. The percentage of sweet amino acids (glycine, threonine, and lysine) in the WFF group was considerably greater than in the OF group (Table 1), indicating that the meat in the WFF group was sweeter and more palatable.

Table 1. Composition of free amino acids in loin.

Amino acids (%) OF WFF SEM p-value Aspartic acid 0.21 0.27 0.01 0.63 Threonine 3.59 8.59 0.40 < 0.01 Serine 1.65 2.25 0.07 0.19 Glutamate 2.38 5.64 0.27 0.01 Glycine 4.98 11.47 0.53 0.03 Alanine 8.62 20.97 1.01 < 0.01 Cysteine 0.21 0.63 0.03 < 0.01 Valine 1.60 2.10 0.05 0.07 Methionine 0.56 0.44 0.01 0.10 Isoleucine 1.04 1.10 0.02 0.56 Leucine 1.85 1.90 0.02 0.71 Tyrosine 0.81 0.85 0.01 0.42 Phenylalanine 1.59 2.24 0.05 0.02 Lysine 1.60 3.02 0.12 0.03 Histidine 1.01 1.86 0.09 0.14 Arginine 0.78 1.29 0.04 0.01 Essential amino acid 11.27 18.95 0.62 0.04 Flavor amino acid 18.59 41.44 1.84 < 0.01 γ-aminobutyric acid 0.54 0.32 0.03 0.19 OF: composition of free amino acids in the loin of pigs fed with ordinary feed; WFF: composition of free amino acids in the loin of pigs fed with wet fermented feed. It is worth noticing that the relative concentration of essential amino acids and arginine in the WFF group was much higher than in the OF group, implying that pork from pigs fed WFF had a higher nutritional value. Amino acids, being the basic component of protein, contribute to physiological and biochemical events such as protein synthesis, and they play a vital role in human nutrition and metabolism[29]. There are eight amino acids called essential amino acids[30], and their contents in the WFF group were significantly higher than those in the OF group, especially the contents of phenylalanine, threonine, and lysine, which were significantly different in the two groups of samples (Table 1). Phenylalanine is the necessary raw material for the body to synthesize adrenaline, thyroxine, and other neurotransmitters and hormones[27]. Threonine promotes the synthesis of phospholipids and the oxidation of fatty acids[9], while lysine has important nutritional significance for growth and development and normal physiological activities[10]. According to the findings of this study, the relative concentrations of essential amino acids in the WFF group were significantly higher, indicating that wet fermented feed improves the flavor and nutritional value of pork. The reason could be that moist, fermented feed is easier for pigs to digest and absorb.

Feeding WFF increased the content of flavor nucleotides

-

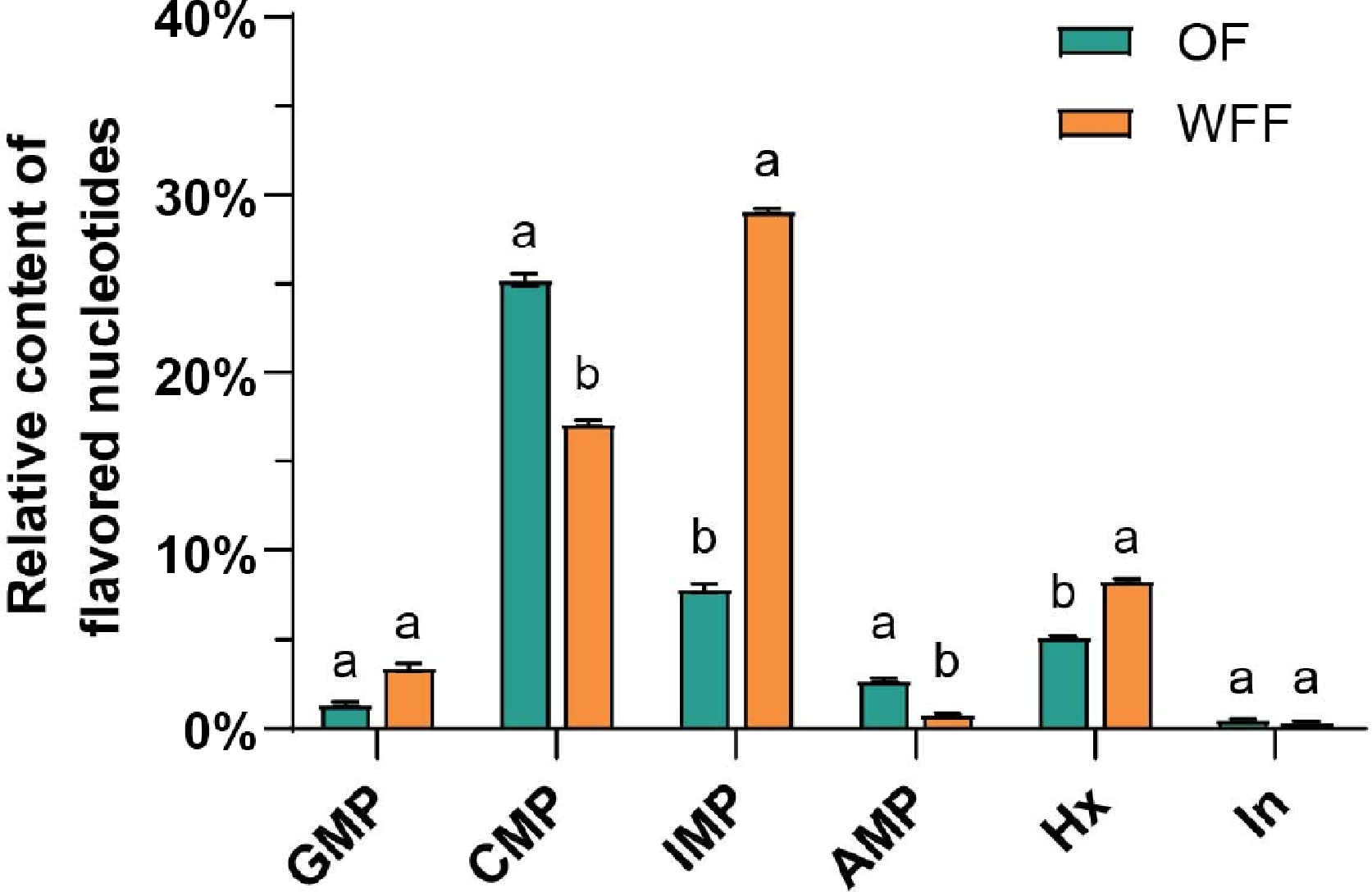

Nucleotides are a vital active substance in living organisms with numerous biological roles[31]. Some nucleotides have a distinct flavor. Ionosine-5'-monophosphate (IMP) and Guanosine-5'-monophosphate (GMP) have the power to block salty, sour, bitter, fishy, and burnt tastes, and hence have a strong ability to improve the taste of pork[32]. In this study, the percentage of GMP and IMP content in the loin of the WFF group was significantly greater than that of the OF group, while the relative content of other nucleotides decreased (Fig. 1). This finding suggests that giving WFF could improve pork flavor by altering the composition ratio of flavoring nucleotides via nutritional management. In a previous study, this phenomenon was attributed to WFF upregulating the expression of flavor nucleotide synthesis-related genes[10].

Figure 1.

Percentage of different flavor nucleotides in the loin. Data are presented as mean ± SE. The difference between the two groups of data was compared by independent sample t-test. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between the two groups of data (p < 0.05). Abbreviations: GMP: Guanylic acid; CMP: Cytidine acid; IMP: Inosine acid; AMP: Adenylic acid; Hx: Hypoxanthine; In: Inosine; OF: ordinary feed; WFF: wet fermented feed.

Feeding WFF increased the relative content of monounsaturated fatty acids

-

One key way of producing meat flavor is lipid oxidation[3]. The principal fatty acids in this study are palmitic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, and linoleic acid (Table 2), which is consistent with the findings of most studies on the fatty acid composition of pigs[33]. Palmitic acid, a fatty acid with a favorable correlation with meat flavor[34], is considerably greater in the WFF group than in the OF group. The content of saturated fatty acids in the WFF group was lowered by 9.23%, whereas the content of monounsaturated fatty acids increased by 9.32%. Furthermore, the relative level of linoleic acid in the WFF group increased by 24.91%, and arachidonic acid was exclusively found in the WFF group. These findings support the conclusions by Lu et al.[35] that giving WFF can greatly enhance the relative percentage of monounsaturated fatty acids in pork. It also demonstrates that WFF pork contains more oxidizable lipids, resulting in a richer scent. Furthermore, some research has indicated that an excessive intake of saturated fatty acids is harmful to human health and can lead to fat deposition, which might cause hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cardiovascular disease, and cerebrovascular illness[36]. Unsaturated fatty acids may improve the metabolism of liver lipoproteins, remove thrombus, lower blood lipids, prevent cardiovascular disease, and fight cancer[37]. As a result, the relevant fatty acid component research results suggest that pork from pigs fed WFF has increased nutritional value and is favorable to human health.

Table 2. Composition of fatty acids in loin.

Fatty acids (mg/100 g loin) OF WFF SEM p-value Caprylic acid C8:0 22.55 – 0.13 – Capric acid C10:0 115.21 49.20 5.29 < 0.01 Lauric acid C12:0 91.43 38.95 4.21 < 0.01 Myristic acid C14:0 6.56 6.15 0.35 0.11 Pentadecylic acid C15:0 24.60 33.21 0.73 < 0.01 Palmitic acid C16:0 666.25 795.40 10.34 0.04 Pearl acid C17:0 216.48 109.47 8.57 < 0.01 Stearic acid C18:0 577.69 537.51 12.72 0.67 Arachic acid C20:0 77.90 76.26 0.47 0.54 Docosate C22:0 83.64 58.63 3.31 0.05 Saturated fatty acid (SFA) 1,923.31 1,745.78 20.02 0.02 Myristic acid C14:1 95.12 161.95 5.35 0.65 Palmitoleic acid C16:1 112.34 205.82 7.50 < 0.01 Heptacenoic acid C17:1 164.41 150.88 2.55 0.79 Oleic acid C18:1n9c 1,243.53 1,265.67 1.78 0.85 Eicosenoic acid C20:1 16.81 – 0.06 – Monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) 1,632.21 1,784.32 12.43 0.09 Trans linoleic acid C18:2n6t 20.09 6.56 1.69 < 0.01 Linoleic acid C18:2n6c 357.11 446.08 7.79 0.04 α-Linolenic acid C18:3n3 41.82 28.70 1.06 0.39 Eicosadienoic acid C20:2 40.59 26.24 4.44 0.05 Eicosatraenoic acid C20:3n6 29.93 37.31 0.66 0.05 Eicosatraenoic acid C20:3n3 24.60 11.89 8.13 < 0.01 Arachidonic acid C20:4n6AA – 31.98 0.13 – Docosahexaenoic acid C22:6n3DHA 35.67 27.88 1.64 0.06 Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) 549.81 616.64 15.10 0.59 OF: composition of fatty acids in the loin of pigs fed with ordinary feed; WFF: composition of fatty acids in the loin of pigs fed with wet fermented feed. The difference between the two groups of data was compared by independent sample t-test. "–" indicates that the substance was not detected. Feeding WFF improves the pork flavor profile

E-nose analysis

-

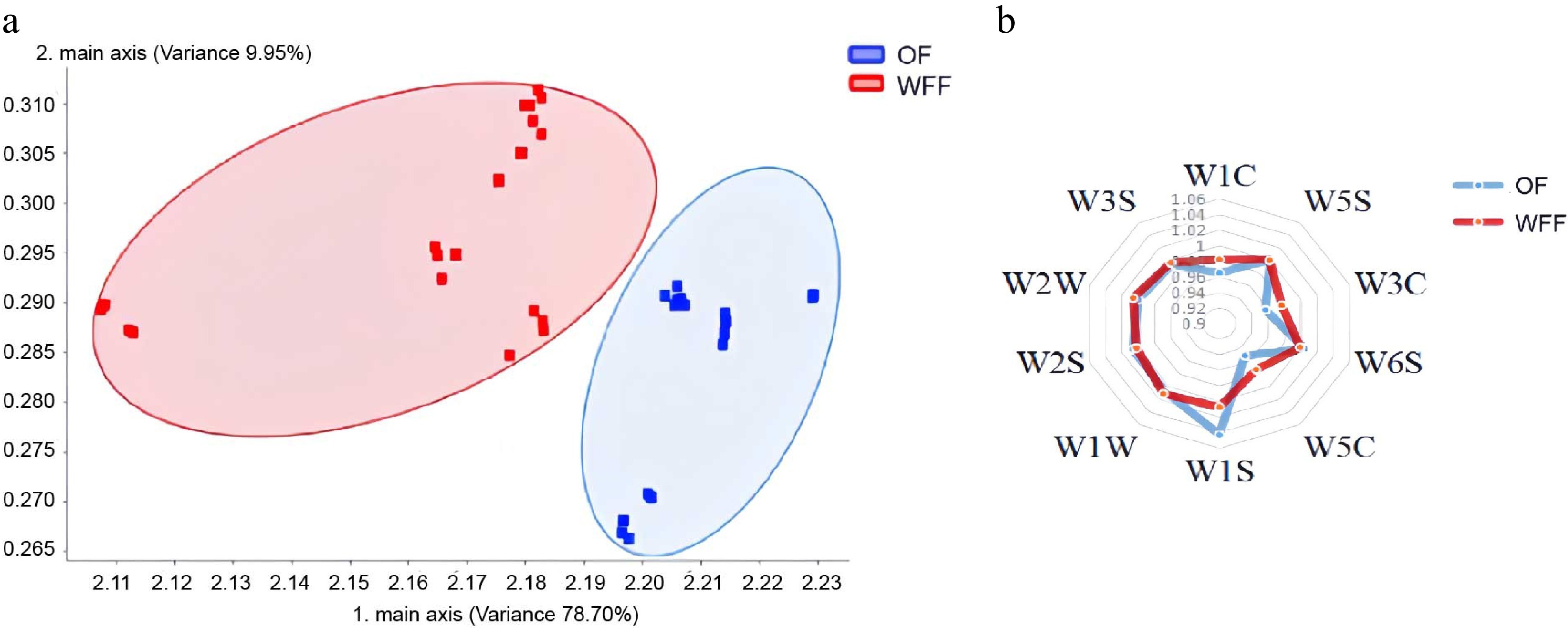

E-nose analysis is a bionics method to quickly perceive food flavor profiles[38]. Figure 2a depicts the principal component analysis (PCA) of the two loins detected by E-nose. The first principal component (PC1) accounts for 78.7%, the second principal component (PC2) accounts for 9.95%, and the sum of the contribution rates of PC1 and PC2 equals 88.65%, which might explain the majority of the sample taste information. OF and WFF were strongly separated in the PC1 dimension, indicating that there are considerable differences in the flavor of the two groups. The source of the flavor variation might be detected further using a radar map (Fig. 2b). The W5C sensor (short-chain alkane aromatic components) has a higher response value to WFF samples than the W1S sensor (methyl)[26]. This shows that the flavor of the OF sample tends to be methane, while that of the WFF sample tends to be alkane. It could mean that the taste composition in the WFF sample is more complex and the carbon chain is longer.

Figure 2.

The flavor profile of loin obtained by E-nose. (a) Principal component analysis (PCA) of the loin flavor of pigs fed with two kinds of feed. (b) Radar map of the loin flavor of pigs fed with two kinds of feed. Abbreviations: OF: ordinary feed; WFF: wet fermented feed.

Gas Chromatography-Ion Migration Spectroscopy analysis

-

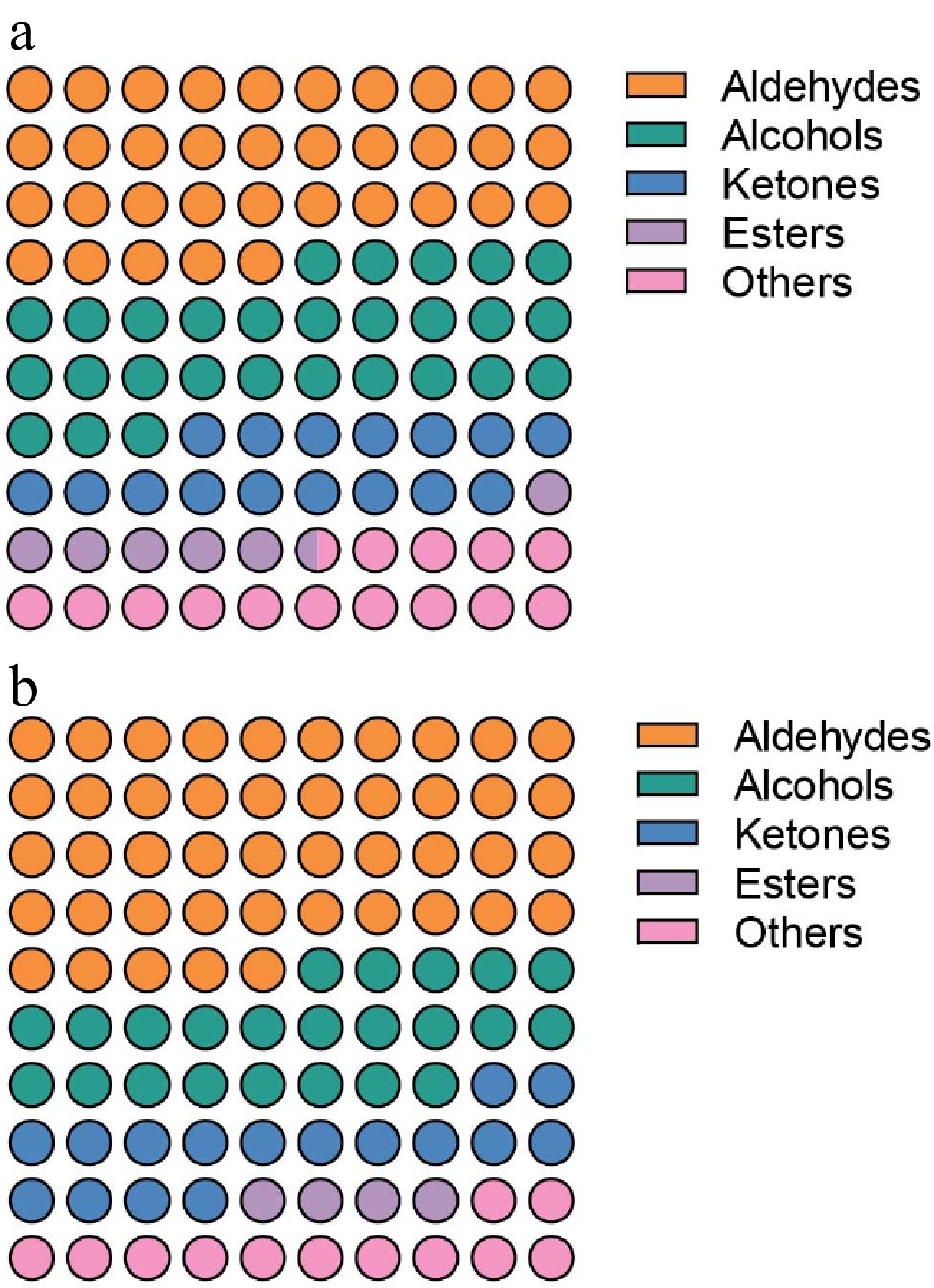

A cutting-edge analytical approach, Gas Chromatography-Ion Migration Spectroscopy, has shown exceptional results in examining complicated samples[39]. It does not require pretreatment and has good repeatability when used to determine loin flavor[3]. The study found 57 chemicals, including 11 aldehydes, 17 alcohols, 13 ketones, seven esters, six acids, one sulfur compound, one phenol, and one terpene (Table 3). The predominant volatile components in the sample include aldehydes, alcohols, and ketones, which are consistent with prior research findings[24].

Table 3. The relative content of volatile organic compounds in loin.

Number Compound RI Rt Dt OF WFF SEM p-value Aldehydes (11) 1 N-butyraldehyde 592.7 155.956 1.1227 3.17 14.96 0.95 0.03 2 Pentanal 691.1 215.162 1.1916 3.09 3.42 0.03 0.42 3 Pentanal-D 688.7 213.467 1.4233 0.91 0.63 0.02 0.22 4 Hexanal 801.5 319.848 1.274 1.44 1.30 0.01 0.01 5 Hexanal-D 802.7 321.219 1.5533 0.77 0.66 0.01 0.50 6 Heptaldehyde 906.5 464.281 1.3434 6.62 7.62 0.08 < 0.01 7 2-Hepteneal 966.6 575.278 1.2576 1.17 0.87 0.02 0.02 8 Octenal 1,055.8 794.090 1.3369 0.44 0.37 0.01 0.50 9 Nonanal 1,099.2 924.726 1.4816 10.68 11.53 0.09 0.13 10 Benzaldehyde 997.4 642.268 1.1368 4.42 3.82 0.02 < 0.01 11 Methylpropionaldehyde 544.1 134.071 1.0913 0.06 0.26 0.02 < 0.01 Alcohols (17) 12 Propanol 530.5 128.641 1.1139 3.04 0.74 0.19 < 0.01 13 Butanol 662.2 195.764 1.1764 2.31 1.93 0.03 0.10 14 Butanol dimer 661.2 195.098 1.3793 0.26 0.26 0.01 0.06 15 Amyl alcohol 762.0 274.140 1.2526 5.71 6.68 0.08 0.06 16 Pentanol-D 759.0 271.311 1.5119 3.03 3.31 0.04 < 0.01 17 N-hexanol 874.4 414.223 1.3223 2.68 1.90 0.06 < 0.01 18 N-hexanol-D 876.1 412.716 1.6478 0.61 0.22 0.03 < 0.01 19 Heptanol 984.6 611.704 1.4035 0.33 0.50 0.01 0.25 20 Octanol 1,070.4 838.377 1.4765 0.28 0.24 0.01 0.06 21 Octanol-D 997.6 639.692 1.4334 3.10 2.60 0.05 0.13 22 Sugar alcohol 871.0 407.499 1.3693 0.31 0.42 0.01 0.06 23 Isobutanol 638.9 181.000 1.1706 0.89 0.63 0.02 0.17 24 3-Methyl-1-Butanol 725.0 241.335 1.2484 0.50 1.01 0.04 0.03 25 2,3-Butanediol 535.0 130.395 1.1691 0.49 0.61 0.01 0.06 26 Ethyl hexanol 1,035.2 735.440 1.4242 0.24 0.30 0.01 0.06 27 Vinyl alcohol 856.0 388.079 1.1847 0.52 0.32 0.02 < 0.01 28 Nonenol 1,159.1 1,146.169 1.8282 1.81 1.41 0.03 0.17 Ketones (13) 29 2-Butanone 622.4 170.746 1.2438 5.28 4.36 0.08 < 0.01 30 2-Pentanone 686.1 211.572 1.392 0.53 0.19 0.03 < 0.01 31 2-Pentanone-D 675.9 204.492 1.3648 0.61 0.48 0.01 < 0.01 32 Heptanone 896.9 446.869 1.6324 0.35 0.25 0.01 < 0.01 33 3-Hydroxy-2-Butanone 721.9 241.704 1.3309 1.05 2.47 0.11 0.09 34 Hydroxyacetone 634.8 178.298 1.0597 0.41 3.54 0.25 < 0.01 35 Hydroxyacetone-D 628.2 175.427 1.2121 0.37 0.16 0.02 0.50 36 2,3-butanedione 535.0 130.395 1.1691 2.29 2.45 0.02 < 0.01 37 2,3-butanedione-D 535.0 130.395 1.1691 0.58 0.54 0.01 0.50 38 Acetophenone 1,064.0 814.998 1.1915 0.32 0.27 0.01 0.06 39 Cyclohexanone 894.4 438.590 1.152 0.36 0.27 0.01 < 0.01 40 Methyl isobutyl ketone 739.2 256.784 1.1709 0.36 1.25 0.07 0.06 41 2,3-Pentanedione 664.6 196.962 1.3190 2.66 0.23 0.20 < 0.01 Esters (7) 42 Ethyl acetate 611.9 165.825 1.0958 1.83 0.49 0.11 < 0.01 43 Ethyl acetate-D 612.4 166.094 1.3377 0.39 0.23 0.01 0.06 44 Ethyl propionate 680.9 207.899 1.1525 0.46 0.13 0.03 0.50 45 2-Methyl 680.9 207.899 1.1525 0.39 0.54 0.01 0.50 46 methylpropionate 917.4 482.754 1.0885 0.55 0.46 0.01 0.12 47 Butyrolactone 891.3 433.702 1.2631 1.66 1.58 0.01 < 0.01 48 Propyl butyrate 1,014.6 682.867 1.415 0.85 0.82 0.01 < 0.01 Acids (6) 49 Acetic acid 598.6 158.918 1.0599 4.41 4.72 0.03 0.17 50 Acetic acid-D 618.4 169.338 1.1466 0.24 0.26 0.01 0.50 51 Caproic acid 1,008.4 667.921 1.3127 0.50 0.27 0.02 < 0.01 52 Caproic acid-D 982.7 609.280 1.6433 0.42 0.26 0.01 0.17 53 2-Methylpropionic acid 777.9 293.139 1.1434 0.19 0.37 0.01 0.50 54 Methyl butyric acid 826.3 349.278 1.4798 1.42 0.94 0.04 0.09 Sulfur compound (1) 55 Dibutyl sulfide 1,086.0 888.807 1.3045 0.59 0.51 0.01 < 0.01 Phenols (1) 56 Maltol 1,086.6 883.783 1.2258 0.13 0.11 0.01 0.50 Terpenes (1) 57 Basilene 1,018.6 692.794 1.6864 5.72 4.62 0.10 0.23 RI, retention index; Rt, retention time; Dt, drift time; OF, the relative content of volatile organic compounds in the loin of pigs fed with ordinary feed; WFF, the relative content of volatile organic compounds in the loin of pigs fed with WFF. Aldehydes have high volatility and a low flavor threshold, which are important for the development of loin flavor[40]. High levels of nonanal and heptaldehyde were discovered in both feeding groups in this investigation, with no significant difference. However, n-butyraldehyde had an aroma of banana and green, and its relative level in the WFF group was much higher than that in the OF group[24]. It is generally believed that aldehydes are produced by fat oxidation; considering the higher content of monounsaturated fatty acids, especially linoleic acid, in the WFF group, this might be the main reason for the difference in aldehyde content between the two groups[39].

Although alcohols have less of an impact on meat flavor than aldehydes, they are nevertheless important[3]. Higher levels of pentanol and n-hexanol were found, and they frequently had a fruity flavor[41]. Furthermore, the relative level of heptanol in the WFF group increased by 51.51%, enhancing the flavor of pork. The formation of alcohols is often related to the metabolism of sugars and amino acids, and many amino acids were found extensively in the WFF group, which explains the origin of some alcohols[10].

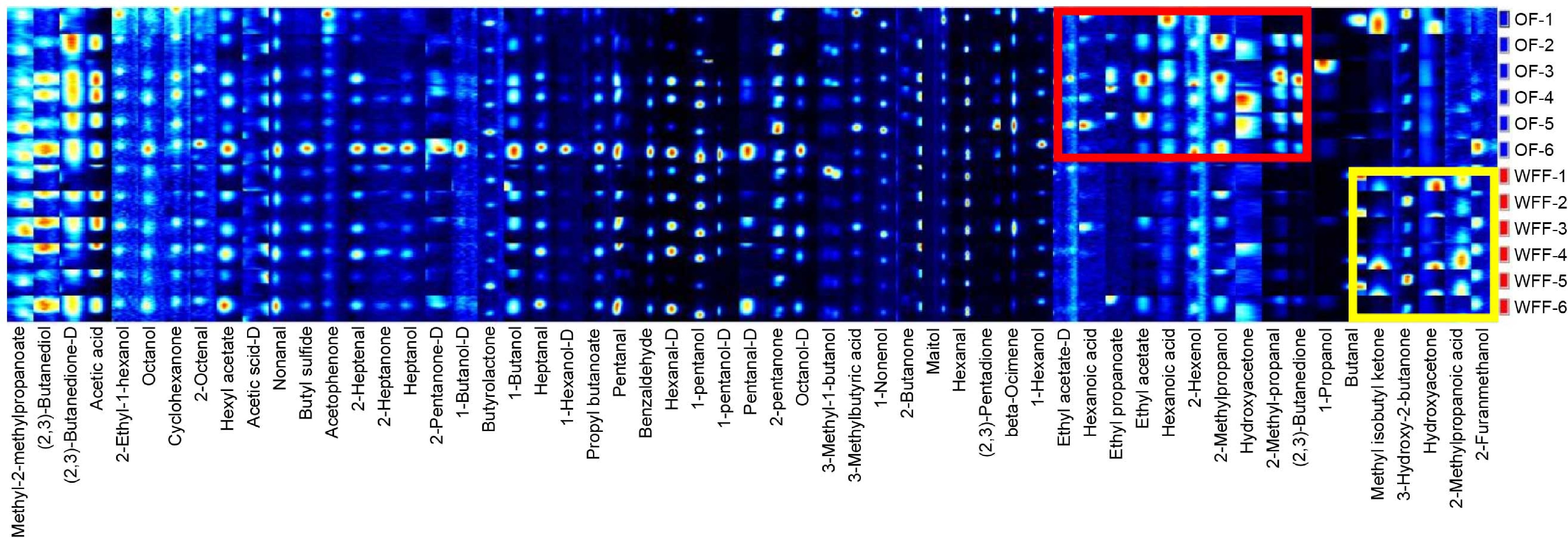

Ketones have a synergistic effect on the smell of pork[30]. The relative content of 2-butanone in the WFF group was not substantially different from the OF group, but the relative content of 2,3-pentanedione was drastically reduced. There are both common and specific chemicals between different feeding groups, according to the fingerprint (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Gallery plot of volatile organic compounds in the loin. Each row represents a sample. Each column represents a volatile compound. The color scale represents the concentration of the volatile compound ("D" means dimer). The content of substances in the red box is higher in the OF group, while that in the yellow box is higher in the WFF group. Abbreviations: OF: ordinary feed; WFF: wet fermented feed.

Nonanal, heptanal, amyl alcohol, n-hexanol, 2-butanone, 2,3-pentanedione, propyl butyrate, hexyl acetate, and other volatile organic chemicals that have a higher impact on the flavor of pork are present in both groups of samples at high concentrations[42]. However, the relative concentration of aldehydes is larger in the WFF loin than in the OF loin, whereas the relative content of alcohols, esters, and other compounds is lower (Fig. 4). The composition and content of volatile organic compounds significantly affect the flavor of pork, so aldehydes are the basis for the improved flavor of the loin of pigs fed fermented feed, according to volatile organic compounds.

-

This study shows that feeding pigs with WFF during the fattening stage helps improve the flavor and nutritional components of their meat. As a feasible nutritional improvement method, the nutritional status of pigs during the fattening stage has been improved by feeding WFF. Pigs fed WFF have higher levels of amino acids, free fatty acids, and flavor nucleotides. This contributed to the development of aldehydes and alcohols in them. It also indicates that WFF improves the flavor and nutritional value of pork.

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Agriculture Science and Technology Innovation Fund (JASTIF) (CX(22)2046), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1600101), the Jiangsu Provincial Key Research and Development Program (BE2020693), and the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (CARS-35).

-

All the procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee of the Experimental Animal Center of Nanjing Agricultural University. The ethical committee number for the study is NJAU.No20230601092.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Hou Y, Zhou T, Ren X, Wu J, Li C; data collection: Hou Y, Zhou T, Ren X, Ibeogu IH, Bako HK; analysis and interpretation of results: Hou Y, Zhou T, Ren X, Wu J; draft manuscript preparation: Hou Y, Zhou T, Ren X, Wu J, Li C. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Hou Y, Zhou T, Ren X, Ibeogu IH, Bako HK, et al. 2025. Assessment of the effect of wet fermented feed in contrast to ordinary feed on pork flavor and nutritional value. Food Materials Research 5: e025 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0021

Assessment of the effect of wet fermented feed in contrast to ordinary feed on pork flavor and nutritional value

- Received: 09 April 2025

- Revised: 17 August 2025

- Accepted: 23 October 2025

- Published online: 31 December 2025

Abstract: The fattening stage is crucial for the development of pork flavor, and employing fermented feed for nutritional management during this phase has been shown to greatly improve pork quality. The purpose of this study was to determine how wet fermented feed (WFF) affected the flavor and nutritional quality of pigs throughout the fattening stage. Duroc × Landrace × Yorkshire pigs were fed a WFF comprising fermented soybean meal, fermented corn, and fermented bran for 60 d for related research. WFF pork loin had significantly higher quantities of necessary amino acids, arginine, inosinic acid, and taste amino acids (p < 0.05). The E-nose demonstrated that the flavor of pork altered according to the diet, with WFF pork having a better flavor. The sensors W5C and W1S could be used to distinguish flavor differences between groups. According to GC-IMS, the relative level of aldehydes in WFF pork was higher than that in the control group, and the relative content of butanal and heptanol was significantly higher (p < 0.05). The saturated fatty acid level of WFF pork decreased by 9.23%, while its monounsaturated fatty acid content increased by 9.32%, there was a 24.91% rise in the relative content of linoleic acid. The results showed that adding WFF considerably improved the flavor and nutritional value of pork.

-

Key words:

- Wet fermented feed /

- Fattening stage /

- Flavor /

- Nutritive value /

- Pork