-

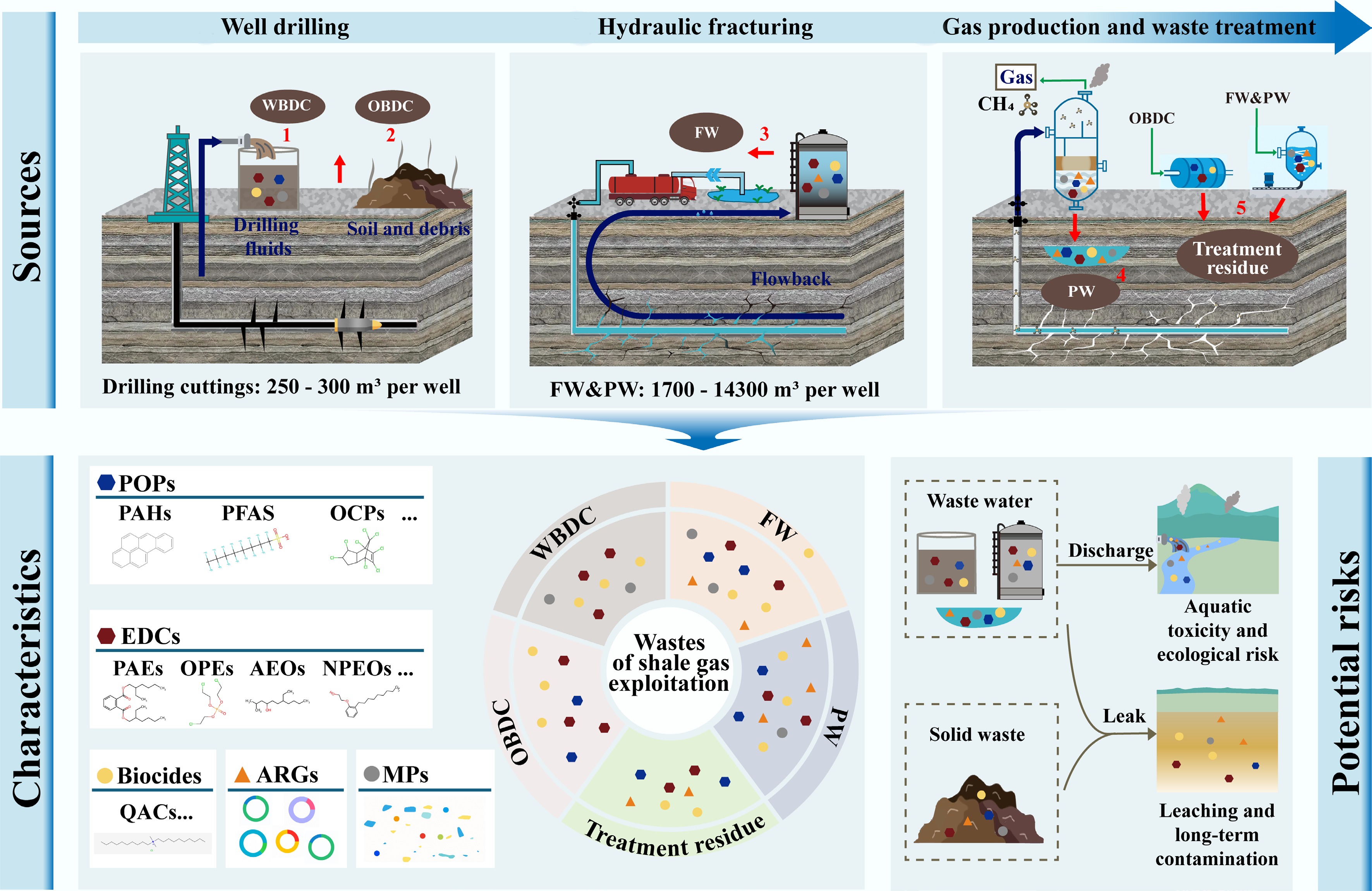

Shale gas, a representative unconventional natural gas resource confined within dense and low-permeability shale formations, has become an important component of the global energy transition owing to its substantial resource potential. Global annual shale gas production reached 8.55 × 1011 m3 in 2022, dominated by the United States, which accounted for approximately 94% of the total output[1]. China holds significant shale gas reserves estimated at 2.00 × 1013 m3, yet its current annual production represents only about 0.1% of its total reserves[2], underscoring substantial potential for accelerated development and a high cumulative growth rate in the coming years. Its economic feasibility primarily depends on the combined application of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technologies[3,4]. This integrated approach remains the only commercially demonstrated method capable of generating effective flow pathways and releasing natural gas from the impermeable shale matrix[5]. This process is a complex, multi-stage engineering operation that generates diverse waste streams across multiple environmental media[6]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, it comprises three major stages: (a) well drilling; (b) hydraulic fracturing; and (c) gas production and waste treatment, each producing specific types and considerable quantities of waste.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating emerging contaminant generation during shale gas extraction, showing primary waste streams at each stage (drilling, fracturing, and production/treatment), estimated generation volumes, and carrying emerging contaminant categories. Names of all the pollutant abbreviations listed above: POPs (persistent organic pollutants); PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons); PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances); OCPs (organochlorine pesticides); EDCs (endocrine disrupting chemicals); PAEs (phthalate esters); OPEs (organophosphate esters); AEOs (alcohol ethoxylates); NPEOs (nonylphenol ethoxylates); QACs (quaternary ammonium compounds); ARGs (antibiotic resistance genes); MPs (microplastics).

Specifically, the extraction process begins with well drilling, which involves an initial vertical section followed by an extended horizontal section. This stage primarily generates substantial solid waste, notably water-based drilling cuttings (WBDC) and oil-based drilling cuttings (OBDC). Following drilling, casing, and cementing, large volumes of fracturing fluid are injected into the formation under high pressure[7,8]. This operation typically consumes thousands to tens of thousands of tons of water, with 10%−70% of the injected fluid returning to the surface as flowback water (FW) and produced water (PW), which together constitute the primary liquid waste stream[9,10]. Due to the frequent difficulty in distinguishing between FW and PW in practice, they are collectively referred to as flowback and produced water (FPW) in the literature[11]. Treating this wastewater further generates sludge. Meanwhile, a common method for managing OBDC, pyrolysis, produces oil-based drilling cuttings ash (OBDCA). In addition, the gas production and surface treatment stages contribute significantly to gaseous emissions. These include greenhouse gases such as methane from fugitive leaks and venting, as well as volatile organic compounds and other pollutants released from combustion equipment[12,13]. The generation and management of such large and varied waste volumes pose substantial environmental challenges due to leakage, unintentional release, or disposal after invalid treatment.

Notably, the issue is further compounded by the fact that these wastes consistently harbor a wide range of emerging contaminants with demonstrated ecological and public health implications, including endocrine disruption, carcinogenic potential, and ecosystem toxicity[14,15]. For example, persistent organic pollutants (POPs) impair reproductive, growth, and immune functions in biota[16,17]. Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) exert diverse toxicities and endocrine-disrupting effects that may lead to cancer and physiological disorders[18,19]. Biocides disrupt mitochondrial function and can promote broader antimicrobial resistance in bacteria[20]. Microplastics can carry various contaminants[16]. It has been shown that two EDCs (di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate and di-n-octyl phthalate) have risk quotients (RQ) exceeding 1, classifying them as shale gas-related organic priority pollutants[21]. These compounds originate mainly from chemical additives used in drilling and fracturing fluids, such as surfactants, lubricants, and biocides, as well as from geogenic substances mobilized from the shale formation[22−24]. Their complex composition and multifaceted toxicity overwhelm conventional treatment methods, ultimately entering various environments[21]. In the context of global climate change, shale gas is poised for leapfrog development as a green, low-carbon energy resource; consequently, the associated waste streams represent a significant and unavoidable source of emerging environmental contaminants. Thus, this study systematically summarizes the occurrence, sources, and characteristics of these new contaminants throughout the stages of shale gas development, evaluates their potential environmental risks, and identifies key management strategies to mitigate their impacts.

-

Drilling operations, which establish wellbore access to shale formations, represent the most significant source of solid waste in shale gas development[6]. A typical shale gas horizontal well generates approximately 800 to 1,000 m3 (about 1,200 to 2,200 tons) of WBDC or 250 to 300 m3 (about 800 to 1,000 tons) of OBDC[24,25]. When normalized by gas production, this corresponds to 0.006 to 0.012 kg of WBDC, or 0.004 to 0.005 kg of OBDC per cubic meter of gas produced. This substantial waste stream, when improperly managed, transforms into a primary reservoir and long-term release source for a diverse suite of emerging contaminants originating from drilling fluid additives.

The systematic analysis of emerging contaminants in drilling operations is based on data systematically retrieved from the Web of Science core collection database. A comprehensive search of studies published over the past five years was conducted using keywords including: 'shale gas', 'drilling cuttings', 'emerging contaminants', 'polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon', 'endocrine disrupt', 'quaternary ammonium compound', or 'microplastic'. From an initial retrieval of 11 publications, the screening process identified six key studies that provided quantitative data on contaminant concentrations in drilling cuttings. These pollutants originate predominantly from the complex mixtures of chemical additives engineered into drilling fluids to fulfill specific operational requirements, such as lubrication, pressure control, and microbial inhibition[24]. Based on their environmental relevance, these contaminants can be broadly classified into four major categories, as detailed in Table 1. First, POPs, particularly polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) originating from diesel used in oil-based fluids, are prevalent in OBDC, with concentrations ranging from 1.25 to 2.37 mg/kg. They also exhibit considerable leaching potential, with reported leachate concentrations of 0.34–1.18 μg/L[26−28]. Their toxicity is primarily attributed to metabolic activation into genotoxic and carcinogenic intermediates, while their environmental persistence and bioaccumulation pose long-term risks to soil and aquatic ecosystems[29]. Second, EDCs are widely detected. Alcohol ethoxylates (AEOs) and nonylphenol ethoxylates (NPEOs), both derived from surfactant additives, are frequently observed, with AEOs occurring in WBDC at concentrations of 1.48–3.22 mg/kg and NPEOs present in OBDC at higher levels of 14.4–26.3 mg/kg[24]. Phthalates (PAEs), commonly associated with fluid formulations and plastic components, are also prominent in WBDC, reaching concentrations up to 877 μg/kg, whereas organophosphate esters (OPEs), used as flame retardants and plasticizers are consistently detected in WBDC at levels up to 527 μg/kg[24]. These EDCs can interfere with hormonal signaling pathways by mimicking or blocking endogenous hormones, leading to reproductive abnormalities, developmental disorders, and metabolic diseases in wildlife and humans. Their high lipophilicity facilitates bioaccumulation in tissues and biomagnification through the food web, posing long-term ecological and health risks, even at low concentrations[30]. Third, antibiotics, referring here to non-therapeutic biocides such as quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) and isothiazolinones employed for microbial control, are key additives[31]. QACs are detected in both WBDC (1.40–2.73 mg/kg), and OBDC (21.8–42.5 mg/kg)[24,31]. Their widespread use raises concerns over potential health impacts, including respiratory diseases, skin sensitization, and their environmental release may contribute to antimicrobial resistance development, and pose toxicity risks to aquatic organisms, highlighting the need for careful risk-benefit assessment in their application[32]. Fourth, microplastics are introduced through polymer-based additives such as polyacrylamide friction reducers and polystyrene lubricants, which may fragment and persist within the drill cuttings matrix[33,34]. Of particular concern are the microplastics introduced as polymer-based additives, which can fragment and persist in the environment. These particles not only cause physical harm through ingestion, but also act as long-term vectors for other contaminants, enhancing their bioavailability and ecological toxicity[35].

Table 1. Emerging contaminants detected in drilling cuttings from shale gas extraction

Category Contaminant Concentration Primary source Sample

sizeAnalytical method Region

(basin)Detection frequency Ref. POPs TPHs 26,700–79,300 mg/kg (OBDC) Base fluid (Diesel/Oil) 5 GC-MS Sichuan Basin, China 100% [26,28,36] PAHs 1.25–2.37 mg/kg (OBDC) 6 67% BTEXs 8.18–8.39 mg/kg (OBDC) 4 75% EDCs PAEs Up to 877 μg/kg (WBDC)

Up to 5.6 μg/kg (OBDC)Plasticizers, lubricants 8 (WBDC)

5 (OBDC)UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS Sichuan Basin, China 100% [24] OPEs Up to 527 μg/kg (WBDC)

Up to 18.5 μg/kg (OBDC)Flame retardants 100% AEOs 1.48–3.22 mg/kg (WBDC) Surfactants 100% NPEOs 14.4–26.3 mg/kg (OBDC) Surfactants 100% Biocides (like antibiotics) QACs 1.40–2.73 mg/kg (WBDC)

21.8–42.5 mg/kg (OBDC)Biocides 8 (WBDC)

5 (OBDC)UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS Sichuan Basin, China 100% [24] Microplastics Polyacrylamide polystyrene / Friction reducers, lubricants / / / / [33,34] '/' indicates that the corresponding information was not explicitly reported in the references. Although emerging contaminants generally occur at trace or ultra-trace levels in the original waste, the improper storage or disposal of drilling cuttings may still pose long-term and complex environmental risks. Based on the typical solid waste generation data per horizontal well, the combined drilling waste stream from a single shale gas well is estimated to release emerging contaminants, including PAHs (1.0–2.4 kg), EDCs (11.5–26.3 kg), and QACs (17.4–42.5 kg). The mixture of contaminants contained in drilling cuttings can be released into surrounding soils and aquatic systems through leaching and surface runoff[37], and their potential for leaching, bioaccumulation, and long-term chronic effects should not be underestimated. However, research on their long-term combined toxicological effects, migration mechanisms in subsurface environments, and cumulative health risks remains extremely limited. In addition, the lack of transparency in drilling fluid formulations further hinders accurate source identification and risk assessment. To promote the green and sustainable development of the shale gas industry, future research must prioritize the development of environmentally friendly drilling fluid additives, elucidate the long-term leaching behavior, and combine ecological impacts of contaminants from drill cuttings, and improve the transparency of chemical formulations used in drilling operations.

-

Hydraulic fracturing represents the most water and chemical intensive stage in shale gas extraction. Each horizontal shale gas well typically consumes between 7,500 and 77,000 m3 of water mixed with proppants and various chemical additives, such as biocides, surfactants, and lubricants, to create fracture networks that release natural gas[23,38]. Following hydraulic fracturing, the wastewater mixed with formation water and returned to the surface is collectively referred to as FPW. Over a well's production lifespan of 5 to 10 years, the cumulative FPW volume per well ranges from approximately 1,700 to 14,300 m3[11]. Given that FPW contains numerous chemical additives to meet engineering requirements, it serves as a significant carrier of emerging contaminants. Leakage, accidental spills, or improper discharge of FPW may therefore lead to the release of these pollutants into the environment.

The data presented were systematically retrieved from the Web of Science core collection database. A comprehensive search of studies published over the past decade was conducted using keywords including: 'shale gas', 'flowback and produced water', 'FPW', 'emerging contaminants', 'persistent organic pollutants', 'endocrine disrupting chemicals', 'biocides', 'antibiotic resistance genes', and their corresponding specific compounds. From an initial retrieval of 92 publications, the screening process identified seven key studies that provided quantitative data on contaminant concentrations in FPW, which form the basis for the summary in Table 2. The emerging contaminants detected in FPW can be classified into four major categories based on their sources and characteristics. POPs are widely present, with PAHs showing the highest concentrations, ranging from 1.5 to 65,671 μg/L[31]. They primarily originate from the thermal cracking of organic matter and additives in fracturing fluids, as well as release from the shale formation. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), such as perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA; 0–1.00 ng/L), perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS; 0–1.20 ng/L), and perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS; 0.17–2.00 ng/L), have also been detected in FPW, likely derived from the degradation of fluoropolymer materials used in equipment[39]. In addition, OCPs with concentrations between 15.33 and 29.22 μg/L, are thought to originate from the leaching of legacy pollutants trapped within shale formations[40], suggesting that hydraulic fracturing may act as a secondary release source for buried persistent contaminants. Furthermore, EDCs represent another major group. NPEOs is widely used as surfactants to reduce friction, are present at 211–12,400 ng/L, and can degrade into more toxic metabolites such as nonylphenol[24]. PAEs, associated with plasticizers and solvents in chemical formulations, have been detected at concentrations as high as 6,725 μg/L[21]. QACs are frequently detected in FPW at concentrations of 260.1 μg/L, reflecting their widespread use as biocides[41]. It is noteworthy that the geological characteristics of shale gas reservoirs, including mineral composition and burial depth, as well as formation-water chemistry such as salinity and ionic composition, together with variation across production stages, substantially affect the types and concentrations of contaminants in FPW[11,42,43].

Table 2. Emerging contaminants detected in wastewater from shale gas extraction

Category Contaminant Concentration Primary source Sample size Analytical method Region (basin) Detection frequency Ref. POPs PAHs 1.5–65671 μg/L Fracturing fluid, thermal cracking, Natural release / / Sichuan Basin, China, and Marcellus Shale, the United States / [31] PFAS PFOA Up to 1.00 ng/L Degradation of fluoropolymer materials 46 LC/MS/MS Permian Basin, the United States 100% [39] PFOS Up to 1.20 ng/L PFBS 0.17–2.00 ng/L PFHpA Up to 0.35 ng/L PFHxA Up to 1.20 ng/L PFTeA Up to 0.24 ng/L NEtFOSE Up to 0.98 ng/L OCPs 15.33–29.22 μg/L Leaching from formation strata 5 GC–MS/MS Sichuan Basin, China 100% [40] EDCs NPEOs 211–12,400 ng/L Surfactants 24 UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS Sichuan Basin, China 100% [24] PAEs Up to 6,725 μg/L plasticizers, solvents / HPLC/Q-TOF-MS the United States / [21] Biocides QACs 260.1 μg/L Biocides 1 HPLC-MS/MS Sichuan Basin, China 100% [41] ARGs ARGs 0.36 copies/cell - 16 Metagenomic sequencing Sichuan Basin, China 100% [44] Microplastics Polyacrylamide / Drag reducers / / / / [45] '/' indicates that the corresponding information was not explicitly reported in the references. In addition to chemical pollutants, FPW has been confirmed as a significant reservoir of biological emerging contaminants, particularly antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). Under long term selection pressure from high concentrations of biocides and antibiotics, unique microbial communities in FPW facilitate the enrichment and horizontal transfer of ARGs[44]. The present study has confirmed that the abundance of ARGs in FPW reaches approximately 0.36 copies per cell, about 1.8 times higher than in natural environments, with dominant types including polymyxin and multidrug resistance genes[44]. When introduced into soil, FPW can increase the total abundance of ARGs by approximately 30.8%, indicating a strong potential to alter environmental resistomes and accelerate the spread of resistance determinants[41]. Although no publicly available quantitative data on microplastics in FPW currently exist, their presence remains a significant environmental concern given the extensive use of synthetic polymers in fracturing operations. For example, polyacrylamide, a high molecular weight polymer, is commonly added to fracturing fluids as a drag-reducing agent[45]. During high pressure hydraulic fracturing, these polymeric additives are subjected to intense mechanical shear and abrasion, which can lead to fragmentation and the subsequent formation of microplastic particles. Additionally, plastic components used in well construction and operational equipment, including liners, seals, and protective coatings, may also release microplastics through mechanical wear and chemical degradation under downhole conditions.

Based on the estimated global FPW generation of 34–286 million m3, derived from the cumulative FPW volume per well (1,700–14,300 m3 per well)[11], and over 20,000 producing wells worldwide[46], combined with the reported concentration ranges of emerging contaminants, the potential mass load of these pollutants released into the environment can be substantial. The mass load for each contaminant category was calculated by multiplying the total FPW volume range by the respective concentration range. It is estimated that their cumulative environmental release amount of PAHs ranges from 51 to 18,783 tons[31], while releases of PAEs could reach up to 1,923 tons[21]. Similarly, QACs are projected to have release ranges of 8,843 to 90,576 tons[41], and OCPs are estimated at 521 to 8,357 tons[40]. These estimates highlight the significant and varied potential of FPW to act as a source of multiple emerging contaminants. The release of these FPW-associated pollutants poses multifaceted environmental risks. Many of these substances are persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic, with the potential to contaminate water bodies and soils, adversely affect aquatic organisms, and even enter food chains. Furthermore, the spread of ARGs may exacerbate the global challenge of antibiotic resistance, increasing public health risks. Therefore, the proper management and advanced treatment of FPW are essential to mitigate the environmental release and risks of these emerging contaminants.

-

Currently, treatment technologies for both solid waste, and wastewater generated from shale gas extraction are not specifically designed for the removal of emerging contaminants. For instance, the primary goal in treating OBDC is to reduce the oil content to below 0.3% to meet environmental disposal standards, with pyrolysis being a widely adopted technique due to its efficiency in base oil recovery and waste volume reduction[47]. Similarly, the treatment of FPW typically relies on membrane-based processes aimed at desalination and the removal of conventional pollutants such as oils, greases, and suspended solids[40]. However, these conventional treatment approaches are often ineffective in completely removing trace-level emerging contaminants and may even facilitate the formation of transformation products or secondary pollutants.

In the case of OBDC treatment, studies have indicated that high-temperature pyrolysis can lead to the transformation of PAHs into higher-ring structures, along with the generation of more complex aromatic compounds[48]. This suggests that OBDCA, often regarded as an inert and safe residue, may in fact act as a sink for POPs, particularly high molecular weight PAHs. Furthermore, Wang et al. detected Adsorbable Organic Halogens (AOHs) in the leachate of OBDCA[49], with concentrations ranging from 0.140 to 0.215 mg/L. The presence of AOHs raise concern, as it suggests the persistence or formation of halogenated organic compounds during pyrolysis, a group of substances known for their high environmental persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and toxicity[50]. Although pyrolysis at temperatures above 600 °C has been shown to remove over 99.8% of PAHs and other POPs in other waste matrices such as sewage sludge[51], the operational conditions in shale gas waste treatment are not always optimized for such complete degradation. Overall, treatment technologies, such as pyrolysis, exhibit limited efficiency for trace-level contaminants, as they fail to achieve complete removal and may even generate transformation products, including complex aromatic compounds and AOHs[47,49,52].

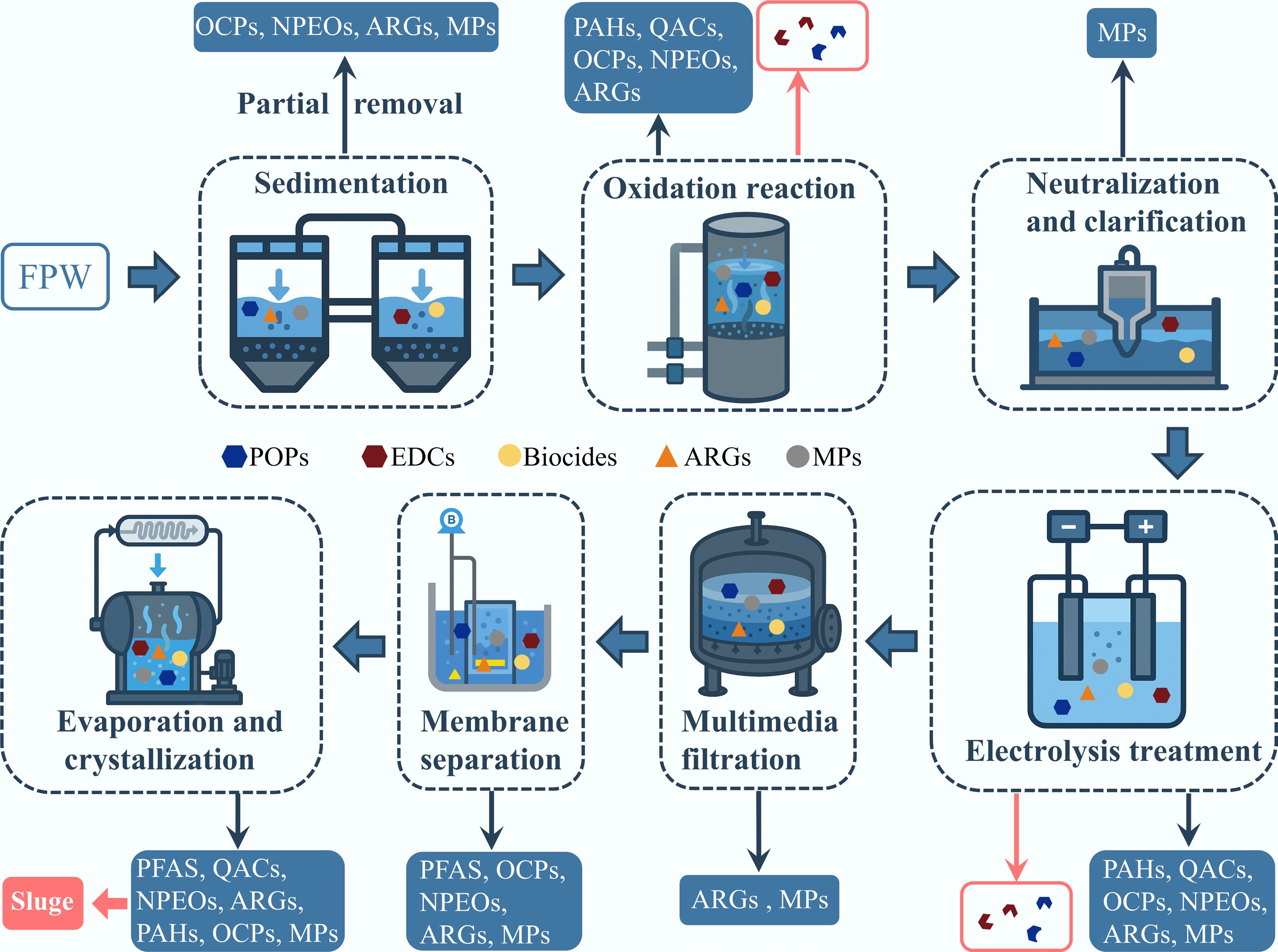

As for FPW, even advanced multi-stage treatment systems, such as the one illustrated in Fig. 2 from an FPW treatment plant in China, show limited effectiveness against many emerging contaminants. While these systems can remove particulate pollutants, oils, and certain heavy metals and nonvolatile organic compounds, the elimination of trace-level emerging contaminants remains challenging. Depending on specific operational parameters, most PAHs, QACs, PFAS, OCPs, NPEOs, and ARGs can be partially or substantially removed. Nevertheless, short-chain PFAS and low-hydrophilicity PFAS may be insufficiently eliminated without dedicated adsorption or ion-exchange pretreatment[53,54]. Moreover, oxidative processes can generate toxic byproducts. In the presence of halogenated species, NPEOs and PAHs may produce chlorinated intermediates during advanced oxidation and electrolysis stages[55,56]. Previous research has demonstrated that even after treatment, PAHs in FPW remained at concentrations of 1,531 ng/L, compared with the initial levels of 1,740–4,393 ng/L before treatment[40], underscoring the limitations of current processes in achieving complete contaminant mineralization.

Figure 2.

Process flow diagram of the FPW treatment plant in China. Blue boxes show emerging contaminants that can be removed by the treatment processes; red boxes represent new pollutants generated during these processes. Blue indicates harmless components; red denotes toxic products, including by-products formed during treatment processes and sludge concentrated through evaporation. Full names of all the pollutant abbreviations listed above: PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons); PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances); OCPs (organochlorine pesticides); OPEs (organophosphate esters); NPEOs (nonylphenol ethoxylates); QACs (quaternary ammonium compounds); ARGs (antibiotic resistance genes).

It is also noteworthy that a variety of hydrophobic or particle-associated emerging contaminants tend to partition into the sludge phase during physicochemical treatment stages. If not properly managed, such sludge may become a secondary reservoir and diffusion pathway for these contaminants, posing further environmental risks. More importantly, emerging contaminants in FPW are often not effectively mineralized into nontoxic products but instead become enriched or transformed into toxic derivatives, which subsequently accumulate in the evaporative residues. As a type of unconventional solid waste, these residues may act as secondary sources of emerging contaminants in the environment if not properly detoxified and managed.

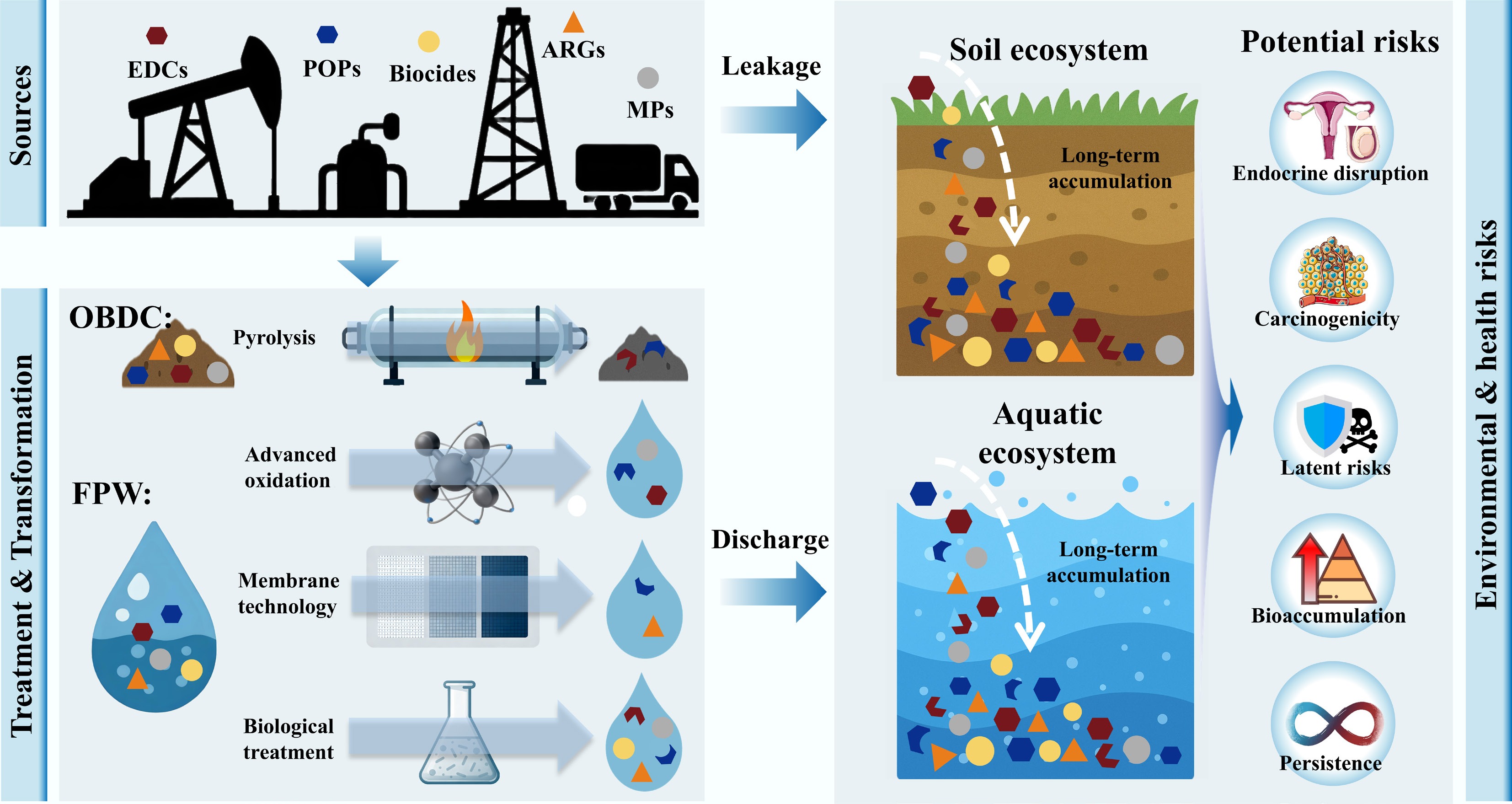

Without upgrades to current treatment technologies, shale gas extraction activities would become a persistent source of emerging contaminants. As depicted in Fig. 3, pollutants released due to inadequate treatment can migrate through environmental media and accumulate over time. Their concentrations may eventually reach thresholds that pose serious risks to ecosystem stability and human health, highlighting the urgent need for enhanced treatment methods and systematic long-term environmental monitoring.

Figure 3.

Sources, treatment methods, transformation, environmental fates, and release risks of emerging contaminants in shale gas extraction.

Effective management of emerging contaminants requires strategies informed by contaminant properties and a realistic appraisal of technologies. For solid waste, treatment primarily targets hydrophobic contaminants with high octanol-water partition coefficients, such as high-molecular-weight PAHs and certain OCPs. These pollutants are amenable to removal via adsorption or advanced oxidation processes. While pyrolysis effectively reduces waste volume and recovers base oil, its efficiency in removing trace-level contaminants is limited and may generate more toxic transformation products[48]. For wastewater, treatment focuses on hydrophilic contaminants, including short-chain PFAS and many QACs, which typically require membrane separation or ion exchange technologies. Additionally, high-molecular-weight polymers in wastewater can be removed by physical filtration, while charged species are suitable for electrochemical treatment. From a techno-economic perspective, membrane technologies achieve high removal efficiency but incur elevated per-unit treatment costs, whereas conventional methods like precipitation and adsorption are cost-effective but offer limited performance. Therefore, a modular and fit-for-purpose approach that strategically integrates processes (e.g., combining advanced oxidation with biological treatment) can balance removal efficiency with cost considerations[56−58].

Major shale gas-producing regions, such as the United States and China, demonstrate distinct pollution profiles, technological practices, and regulatory approaches, highlighting the importance of regionally tailored management strategies. For example, FPW in the United States contains higher concentrations of certain pollutants, with PAHs averaging around 433 μg/L compared to about 2 μg/L in China[31]. In contrast, China employs more intensive drilling techniques and deeper reservoirs, resulting in chemical additive usage approximately 20 times greater than that reported in the United States[59]. Regulatory frameworks also differ substantially. The United States follows a decentralized, state-led governance model that depends largely on industry self-regulation and lacks unified federal standards for emerging contaminants in shale gas wastewater. China, however, has implemented centralized policy instruments such as the List of Key Controlled New Pollutants (2023) and the Catalogue of Priority Controlled Chemicals. Despite these efforts, regulatory gaps of emerging contaminants remain in both countries, underscoring a shared need for more comprehensive and contaminant-specific controls. These regional distinctions reinforce that effective, fit-for-purpose treatment strategies must be rooted in local technical and regulatory contexts. There is a clear imperative to strengthen legal frameworks, enhance transparency in chemical disclosure, and foster collaboration across industry, research, and regulatory bodies to systematically reduce the environmental impact of shale gas development.

-

Shale gas extraction serves as an important energy source but also represents a major pathway for the release of various emerging contaminants into the environment. This review systematically identifies solid waste streams, including WBDC, OBDC, OBDCA, FPW and its sludge, as the primary carriers of these pollutants. The major contaminant groups include POPs such as PAHs and PFAS; EDCs such as NPEOs and PAEs; biocides such as QACs; microplastics; and ARGs. Due to their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and uncertain long-term ecological impacts, particularly through their effects on water and soil quality and their potential entry into food chains, these substances pose complex environmental challenges. Future efforts should prioritize these contaminants based on their emission loads, persistence, toxicity, and bioaccumulation potential to guide risk-based monitoring and resource allocation.

Current management practices face multiple critical challenges. The confidential compositions of drilling and fracturing fluids constitute fundamental barriers to accurate source identification and comprehensive risk assessment. Existing treatment technologies, such as pyrolysis for solid wastes and multi-stage processes for wastewater, show limited effectiveness in removing trace-level emerging contaminants and may generate transformation products with unknown toxicity profiles. Moreover, the widespread use of antimicrobial agents may promote the development and dissemination of ARGs in environmental systems, introducing additional risks.

Achieving sustainable shale gas development requires the establishment of a comprehensive management strategy that integrates multiple control measures. This includes stage-specific interventions such as adopting low-toxicity drilling fluids, enforcing source control of fracturing additives, and promoting the reuse of flowback and produced water. This strategy should include: (1) strengthening monitoring and assessment systems, potentially supported by adaptive real-time monitoring, to track the fate of key contaminants across environmental media; (2) formulating differentiated, fit-for-purpose treatment schemes and developing targeted technologies to prevent the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes; (3) implementing strict source control through regulatory requirements for chemical disclosure and the promotion of environmentally friendly alternatives; and (4) ultimately establishing a full life-cycle waste management framework based on science-informed risk assessment standards and robust environmental containment, such as impermeable liners and sludge stabilization, to reduce leaching. Future research should prioritize the development of novel intervention strategies, including advanced treatment technologies and materials for targeted contaminant removal, as well as integrated models to predict long-term environmental impacts. Only through coordinated efforts that combine preventive measures, technological innovation, and effective governance can the shale gas industry achieve a balance between energy production and environmental protection.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Yuejia Zhang: data curation and formal analysis, and writing − original draft; Kejin Chen: data curation and formal analysis, investigation and methodology, writing − original draft, and writing − review and editing; Yulian Zhang: data curation and formal analysis, and investigation and methodology, visualization; Lilan Zhang: writing − review and editing, supervision, project administration and funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42522712, 42377387).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yuejia Zhang, Kejin Chen

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang Y, Chen K, Zhang Y, Zhang L. 2026. Emerging contaminants in shale gas extraction: sources, characteristics, and potential risks. New Contaminants 2: e001 doi: 10.48130/newcontam-0025-0021

Emerging contaminants in shale gas extraction: sources, characteristics, and potential risks

- Received: 09 November 2025

- Revised: 12 December 2025

- Accepted: 23 December 2025

- Published online: 15 January 2026

Abstract: The extraction of shale gas, a vital unconventional resource in the global energy mix, predominantly relies on horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing. A consequential byproduct of this process is the generation of substantial quantities of solid and liquid waste. These waste streams present a potential hazard by functioning as primary vectors for a wide range of emerging contaminants, primarily including persistent organic pollutants such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, endocrine-disrupting chemicals like nonylphenol ethoxylates and phthalates biocides, particularly quaternary ammonium compounds, microplastics, and antibiotic resistance genes. These substances pose considerable threats to ecosystem and human health due to their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and inherent toxicity. This review systematically analyzes the sources and characteristics of these emerging contaminants across the entire shale gas lifecycle, from drilling to final waste management. It further evaluates their potential environmental risks and underscores the limitations of current treatment technologies, which frequently prove inadequate for the complete removal of trace-level pollutants, and may even generate toxic transformation products. Consequently, the study puts forward a set of integrated mitigation and management strategies. The overarching goal is to support the sustainable development of the shale gas industry by reconciling energy production with critical environmental protection requirements.

-

Key words:

- Shale gas /

- Emerging contaminants /

- Drilling cuttings /

- Flowback and produced water /

- Environmental risk