-

Apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) is an economically important fruit tree crop cultivated worldwide. As both the largest producer and consumer of apples globally, China plays a dominant role in the industry. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) statistics, global apple production reaches approximately 82 million tons annually, with China accounting for more than 42 million tons of this output. Fruit appearance, characterized by bright coloration and a smooth surface, is a key determinant of consumer preference and marketability[1,2]. Therefore, the appearance quality of apple fruits is a critical determinant of their commercial value. A major factor compromising this quality is fruit russeting, a common physiological disorder characterized by the formation of a suberized outer skin that replaces the original epidermis, creating a continuous but rough protective layer[3]. This process typically occurs during fruit growth and expansion, where stress-induced cuticular rupture leads to periderm development and a coarse surface texture[4], ultimately diminishing the marketability of the fruit.

Apple russeting represents a well-documented physiological disorder in fruit, with a long-standing history of scientific investigation[5]. The etiology of russeting is multifactorial and can be broadly attributed to two main aspects. The first category encompasses cultivation-related physiological conditions, including excessive moisture[6], high humidity[7], low-temperature frost damage[8], exposure to certain pesticides[9] and growth regulators[10], application of surfactants[11], as well as various forms of abiotic stress[12,13]. The second aspect involves the genetic basis underlying apple cultivars[14]. Phenotypic analysis of hybrids derived from full russeting, non-russeting, and partially russeting cultivars, conducted by Alston et al., revealed that the non-russeting phenotype was governed by multiple genetic factors[15]. Recent genetic studies have further elucidated the hereditary mechanisms associated with russeting across various fruit tree species. A significant genetic locus associated with russeting was mapped to linkage group 12 in 'Renetta Grigia di Torriana'[16]. Furthermore, in a cross between 'Golden Delicious' and 'Braeburn', seven QTLs linked to russeting were identified on chromosomes 2 and 5[17]. Additionally, Powell et al. reported two major QTLs for russeting spots (located on LG2 and LG6) and five potential loci in a 'Honeycrisp' progeny, demonstrating that haplotype combinations influence phenotypic severity[18]. Subsequently, based on 947 SNPs genotyped across 1,009 progeny (based on) and phenotypic data collected over three years, a genomic prediction model achieved moderate predictive accuracy (R = 0.28−0.35)[19]. Together, these findings indicate that hybrid populations represent valuable materials for investigating fruit russeting, providing distinct phenotypic variations suitable for further genetic analysis.

Current research on the molecular mechanisms of fruit russeting in horticultural crops has primarily centered on pears, grapes, and apples. For instance, a comparative transcriptomic study between the pear cultivar 'Dangshansuli' and its russeting mutant 'Xiusu' revealed that signal transduction pathways related to lignin synthesis, polyamines, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) are involved in the development of pear fruit russeting[20]. In apple studies, comparative transcriptomic analyses between three non-russeting and three russeting apple cultivars led to the identification of a MYB family transcription factor, MdMYB93. Subsequent ectopic expression in tobacco resulted in elevated levels of xyloglucan and its precursors, phenylpropanoids, and lignin monomers, indicating that MdMYB93 acts as a positive regulator in the formation of apple russet[21]. Additionally, multiple MYB family transcription factors have been implicated in the regulation of genes related to xylem development and extracellular lipid biosynthesis, thereby influencing xylem formation and the synthesis and accumulation of lignin[22−24]. Studies have shown that the peel of russeting apples contains comparatively high levels of phenolic compounds[25]. Correspondingly, the expression of MdPAL, an upstream regulating gene in phenolic biosynthesis, was found to be significantly upregulated, underscoring its critical role in the formation of fruit russeting[26]. The inhibition of fruit russeting was observed after bagging, accompanied by a reduction in both the expression levels and enzyme activities of PAL, 4CL, C4H, CAD, and POD, which are associated with lignin biosynthesis[27]. These findings indicate that the formation of fruit russeting is primarily driven by the excessive deposition of lignified tissues and lignin within the cell layers. This accumulation process is closely linked to the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway. As the initiating and rate-limiting enzyme of this pathway, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) plays a pivotal regulatory role[28].

Current approaches to mitigating apple russeting include bagging techniques[29] and the application of plant growth regulators, notably gibberellins[30,31]. While research indicates that russeting initiation is largely confined to the early phases of fruit growth and development[3,8], the precise developmental window for its onset remains inadequately defined. The morphological characteristics of the cuticle in the early stages of apple fruit development are not yet fully characterized.

In this study, three russeting-susceptible and three russeting-resistant apple cultivars were characterized to investigate their physiological and biochemical traits, along with cuticular modifications, during early fruit development. This approach enabled the identification of the key developmental window for russeting initiation and the associated morphological changes in the cuticle. This study clarifies the key period of apple fruit russeting and characterizes the accompanying morphological changes in the cuticle. These findings establish a foundation for subsequent research into the molecular mechanism underlying russet formation and provide a theoretical basis for developing targeted control strategies in orchard management.

-

This study investigates common russeting-resistant and russeting-susceptible cultivars, comprising three russeting-susceptible cultivars ('Venus', 'Golden Delicious', 'Fuji') and three russeting-resistant cultivars ('Red Chief', 'Luli', 'Dailv'). The field experiment was conducted in an orchard at the Tianping Lake Experimental Base of the Shandong Fruit Research Institute in Tai'an City, Shandong Province. Apple sampling was collected at 20, 35, 50, 65, and 80 d after flowering. To ensure sample consistency and quality, the following selection criteria were applied: (1) no mechanical damage on the fruit peel; (2) no visible physiological disorders; and (3) uniform fruit size. This sampling strategy provided representative material for analyzing different developmental stages.

Aniline blue staining experiment

-

Harvested apples were briefly rinsed to remove surface contaminants, and then immersed in 0.2% (m/v) aniline blue solution within a vacuum desiccator. Vacuum was applied and maintained at 0.06 MPa for 60 s, returned to atmospheric pressure, and immersed for another 60 s followed by release to atmospheric pressure and an additional 60 s immersion. After staining, samples were rinsed, gently blotted dry, and the stained area ratio was quantified. Classify results using grading criteria. Fruit russeting is categorized into six grades based on the extent of russet coverage: Grade 0 indicates no russet, Grade 1 corresponds to ≤ 5% russet coverage, Grade 2 covers 6%–10%, Grade 3 encompasses 11%–15%, Grade 4 includes 16%–20%, and Grade 5 represents > 20%[32]. The formula for calculating the staining index is as follows:

${\begin{split}&\rm Staining\;Index=\\&\rm \dfrac{\sum (The\;representative\;value\;of\;each\;level \,\times\, The\;no.\;of\;fruits\;in\;that\;level)}{Total\;fruit\;count \,\times\, Heaviest\;grade\;value}\\& \times 100{\text{%}}\end{split} }$ Microscopic observation

-

Pericarp was collected from fruits of different cultivars at different developmental stages. To ensure statistical robustness, three independent biological replicates (i.e., fruits from different trees) were sampled for each cultivar–stage combination. Samples were first rinsed with distilled water, after which a circular segment approximately 10 mm in diameter was excised from the pericarp using a scalpel. Each segment was then mounted on a glass slide for surface observation under a stereomicroscope. For quantitative analysis, five random fields of view were documented per segment.

Tissue section analysis

-

Based on previously established methods with minor modifications, the fruits of each cultivar were gently rinsed with distilled water. Small segments of epidermal tissue (approximately 5 mm long × 1 mm thick) were then excised from the equatorial region and fixed in FAA fixative for 48 h. After fixation, the samples underwent gradient alcohol dehydration followed by xylene clarification. The clarified samples were then placed in paraffin embedding molds, embedded using a paraffin tissue embedding machine, and allowed to solidify rapidly at −20 °C. The embedded samples were sectioned into continuous slices of 3 μm thickness using a microtome, and the sections were mounted onto glass slides. The slides were subsequently dewaxed in a series of graded xylene-ethanol mixtures. Finally, the sections were stained with a 1% aniline blue methanol solution and mounted with neutral resin. For each biological replicate, at least two non-consecutive sections (technical replicates) were prepared and observed to ensure representative sampling and methodological consistency. Observations were performed under a Leica inverted microscope, and images were acquired with an attached imaging system for measurement of wax layer thickness and epidermal cell counts. Five random fields of view were captured and measured per section. Images were acquired with an attached imaging system.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) analysis

-

Following the research methods of predecessors[33,34], epidermal tissues from fruits of different cultivars and at various developmental stages were collected. For each combination of cultivar and developmental stage, three independent biological replicates were processed. The samples were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently transferred to a vacuum freeze-dryer (FDU-1110, EYELA, Tokyo, Japan) for dehydration over a 48-h period. Afterward, the samples were coated using an ion sputtering instrument and finally observed under a JSM-6610 SEM (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) environmental field scanning electron microscope. During imaging, five random fields of view were captured for each technical replicate to obtain representative morphological data.

Determination of enzymatic activity of antioxidant system and metabolism of reactive oxygen species

Determination of reactive oxygen species levels

-

The content of superoxide anion (O2−) was determined as follows: the frozen tissue (2 g) was homogenized in 5 mL of ice-cold phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.8) and centrifuged (12,000 × g, 10 min, 4 °C). The supernatant (1 mL) was mixed with 1 mL hydroxylamine-HCl (1 mM) and 1 mL PBS, then incubated at 25 °C for 60 min with gentle agitation. For chromophore development, 1 mL sulfanilamide (17 mM) and 1 mL α-naphthylamine (7 mM) were added, followed by 20 min incubation at 25 °C. Absorbance was measured at 530 nm (UV-1800, Shimadzu).

For the determination of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content, the pericarp tissue samples (1 g) were cryogenically pulverized in 10 mL pre-chilled acetone and centrifuged (12,000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C). The clarified supernatant (1 mL) was reacted with 100 mL 10% TiCl4 and 0.2 μL NH4OH, forming a yellow peroxotitanium complex. Following precipitation (10,000 × g, 5 min), the pellet underwent triple acetone washes before dissolution in 3 mL 2 M H2SO4. After 10 min stabilization at 25 °C, absorbance readings at 412 nm (UV-1900, Shimadzu) were referenced against freshly prepared H2O2 standards[35].

Antioxidant enzyme activity determination

-

The activity levels of antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT), were determined using assay kits manufactured by Suzhou Keming Biotechnology Co. Ltd. For detailed methodologies, please refer to the instructions provided in the kit documentation.

Determination of lignin content and enzyme activities of phenylalanine metabolic pathway

Lignin content

-

Frozen pericarp sample (1 g) powder was acid-digested with 7.5 mL 72% sulfuric acid through continuous stirring (25 °C, 2 h). The hydrolysate was diluted to 3% acid concentration with 270 mL deionized water and subjected to autoclave treatment (121 °C, 60 min) in foil-covered Erlenmeyer flasks. The acid-insoluble fraction was vacuum-filtered through pre-weighed Kiriyama SB-40 glass microfiber filters, followed by exhaustive hot water rinsing until neutral pH. The retained lignin was oven-dried (105 °C) to constant mass[36].

Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity detection

-

The experimental protocol for phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) assay involved processing fresh pericarp material (1 g FW) through mechanical disruption in ice-cold extraction medium (2 mL) prepared in 50 mM borate buffer (pH 8.8). The buffer solution was supplemented with 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol as a reducing agent and 1% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone for protein stabilization. Following cold centrifugation at 15,000 × g (20 min, 4 °C), the clarified fraction was collected for enzymatic analysis. The reaction system contained 10 mM L-phenylalanine as substrate in a temperature-controlled environment (37 °C) with 30-min incubation. Acidification with 0.1 mL concentrated HCl (6 M) effectively terminated the enzymatic conversions. Enzyme quantification standards were established where one activity unit corresponds to ΔA290 nm = 0.01 min−1·g−1 FW in the specified cuvette configuration (1 mL total volume).

Cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase (C4H) activity analysis

-

C4H activity was determined using a kit from Suzhou Keming Biotechnology Co. Ltd, China. The determination method shall be performed in accordance with the procedure outlined in the manual. Regents were added as instructed. C4H activity was expressed as U/g FW, where U = 0.01 OD340 min–1.

RT-qPCR analysis

-

RNA was isolated from fruit peels using an RNA extraction kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized with an RNA reverse transcription kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Sample preparation and RT-qPCR machine settings were carried out following previously reported methods[37]. 18S (apple) was employed as the internal reference gene for normalization. To ensure data reliability, the experiment was designed with three biological replicates (each consisting of a pooled sample from three distinct apples of the same cultivar), and each biological replicate was measured with three technical replicates. All the gene primer sequences involved in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Data analysis

-

The experiment design followed a completely randomized layout. Data were organized using Microsoft Excel 2003. Statistical analyses, including significance testing (p < 0.05), principal component analysis (PCA), and correlation analysis, were performed with SPSS 25.0. All figures were prepared using Origin 2018. Each experiment included at least three biological replicates, with three technical replicates measured per biological replicate.

-

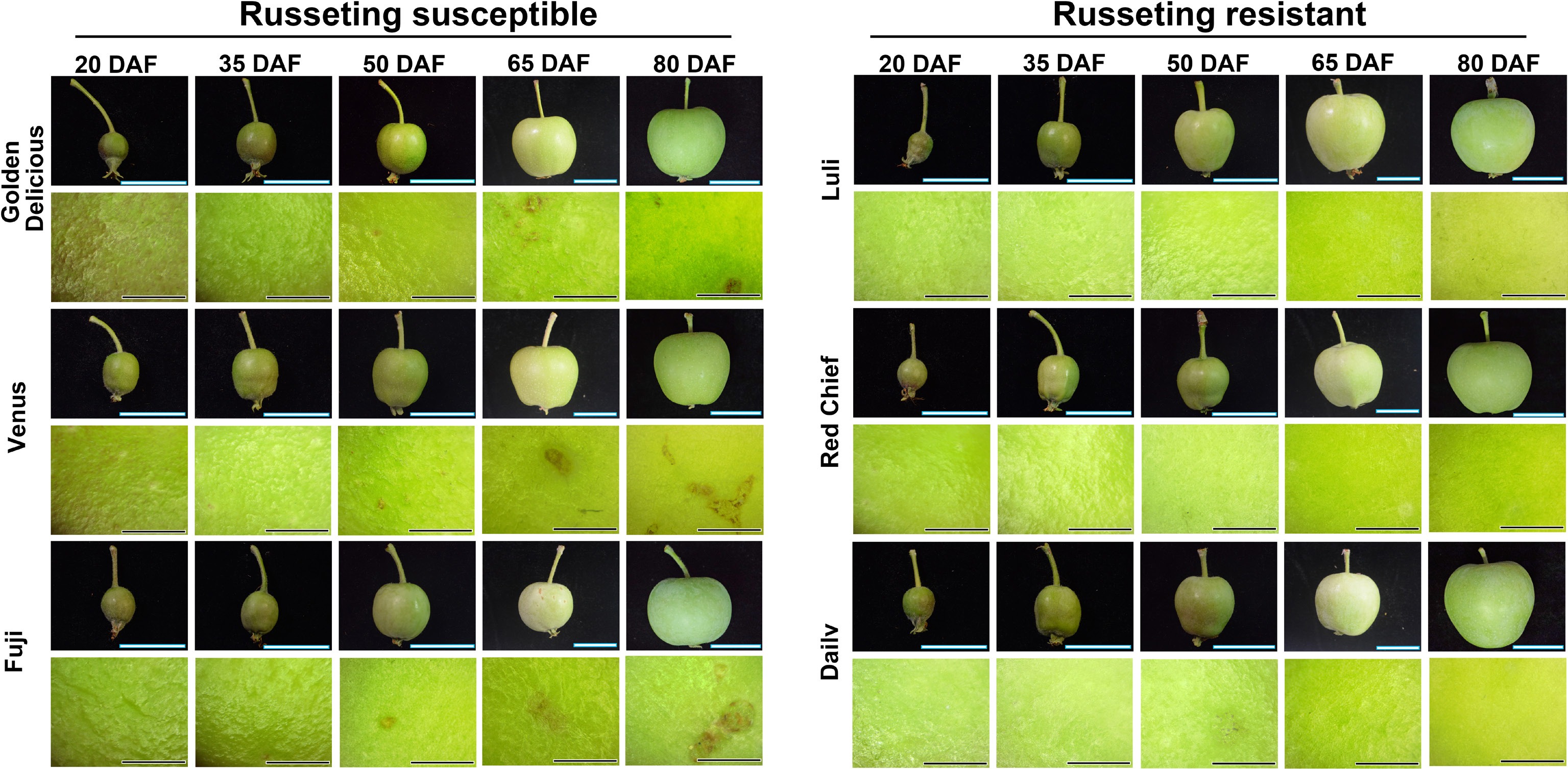

To identify the critical phase of fruit russeting development across apple cultivars, three commonly grown, russeting-susceptible cultivars and three russeting-resistant ones for comparison, were selected. As illustrated in Fig. 1, microscopic observations revealed that at the 50 DAF stage, the fruits of 'Golden Delicious', 'Venus', and 'Fuji' exhibited distinct blackish-brown patches, whereas the skins of the other three cultivars remained relatively smooth and intact.

Figure 1.

Dynamic changes of fruit russeting in different apple cultivars observed by stereomicroscope. Fruit development was documented at 20, 35, 50, 65, and 80 d after flowering (DAF). Scale bars represent 1 cm. Observation of fruit russeting on the equatorial region under a stereomicroscope at 4x magnification. Scale bars represent 1 mm.

Dynamic changes of epidermal cuticle during the growth and development of different cultivars of apples

-

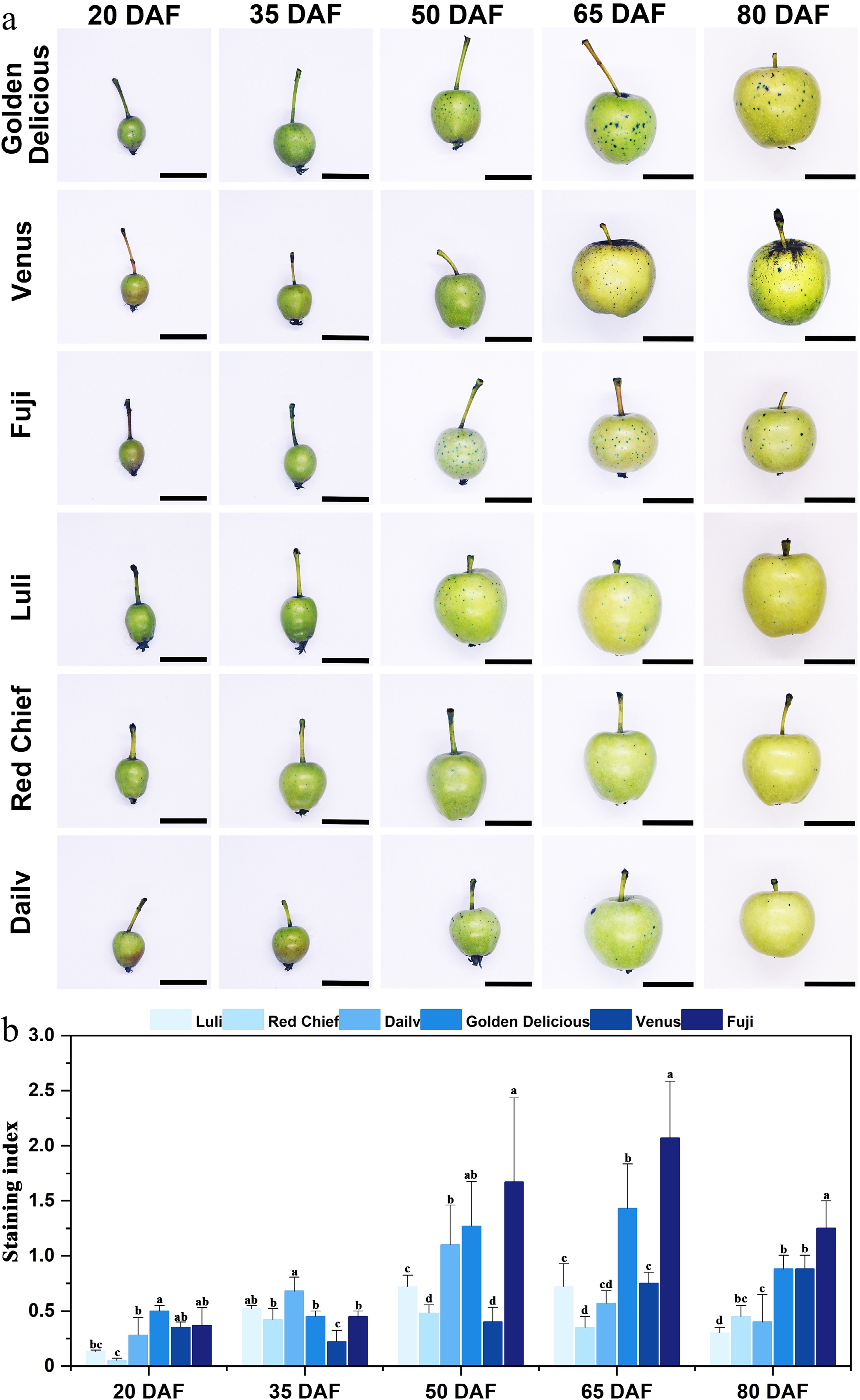

As shown in Fig. 2a, fruit surfaces were stained with aniline blue during development to assess cuticular integrity. Among the russeting-susceptible cultivars, 'Golden Delicious' exhibited distinct spots after 50 (DAF), with the coverage rate of russeting spots reaching approximately 40%–50% at 80 DAF. At 50 DAF, 'Venus' fruit displays sporadic light brown spots in localized areas of the epidermis (near the fruit stalk or body), arranged in a dot-like pattern. By 65 DAF, the number and intensity of spots increase significantly, and the color deepens to brown. Additionally, the top of this variety's fruit is particularly prone to severe russeting. In 'Fuji' fruit at 50 DAF, pinpoint russeting spots approximately 1 mm in diameter appeared sparsely on the fruit shoulder or body. At 80 DAF, the number of russeting spots increases, and some spots extend to the calyx depression; however, the size of individual spots does not expand significantly. In contrast, the three russeting-resistant cultivars, 'Luli' and 'Red Chief', exhibit smooth fruit skins throughout all developmental stages, with no significant russeting symptoms detected. In contrast, 'Dailv' fruit shows minor stained spots starting at 50 DAF, which were markedly fewer than those observed in the highly susceptible cultivars.

Figure 2.

Observation and analysis of aniline blue staining on fruits of different apple cultivars. (a) Aniline blue staining of apple fruits across cultivars and developmental stages. Scale bars represent 1 cm. (b) Staining index. Error bars represent the means ± SD (n = 3) taken from three independent biological replicates. Different letters represent significant differences (one-way ANOVA, Tukey-Kramer test, p < 0.05). DAF = days after flowering.

The staining index of different apple cultivars exhibits significant differentiation during the developmental stage (Fig. 2b). The resistant cultivars 'Luli' and 'Red Chief' consistently maintained relatively low levels throughout the observation period, with a brief peak occurring at 50 DAF ('Luli': 0.72 ± 0.09; 'Red Chief': 0.48 ± 0.08). In contrast, the highly sensitive cultivars 'Golden Delicious' and 'Fuji' demonstrated rapid accumulation characteristics. The staining index of 'Golden Delicious' progressively increased from 50 DAF (1.27 ± 0.40) to a peak of 65 DAF (1.43 ± 0.38), subsequently declining to 0.9 at 80 DAF. 'Fuji' exhibited a sharp rise from 50 DAF to a peak of 65 DAF (2.07 ± 0.51). 'Dailv' and 'Venus' exhibited an intermediate susceptibility profile. For instance, 'Dailv' showed a peak in symptom intensity at 50 DAF, followed by a gradual decrease through 80 DAF. Together, these observations indicate that the critical developmental window for the onset of fruit russeting lies between 50 & 65 DAF.

The changes in epidermal structure during the growth and development of different cultivars of apples

-

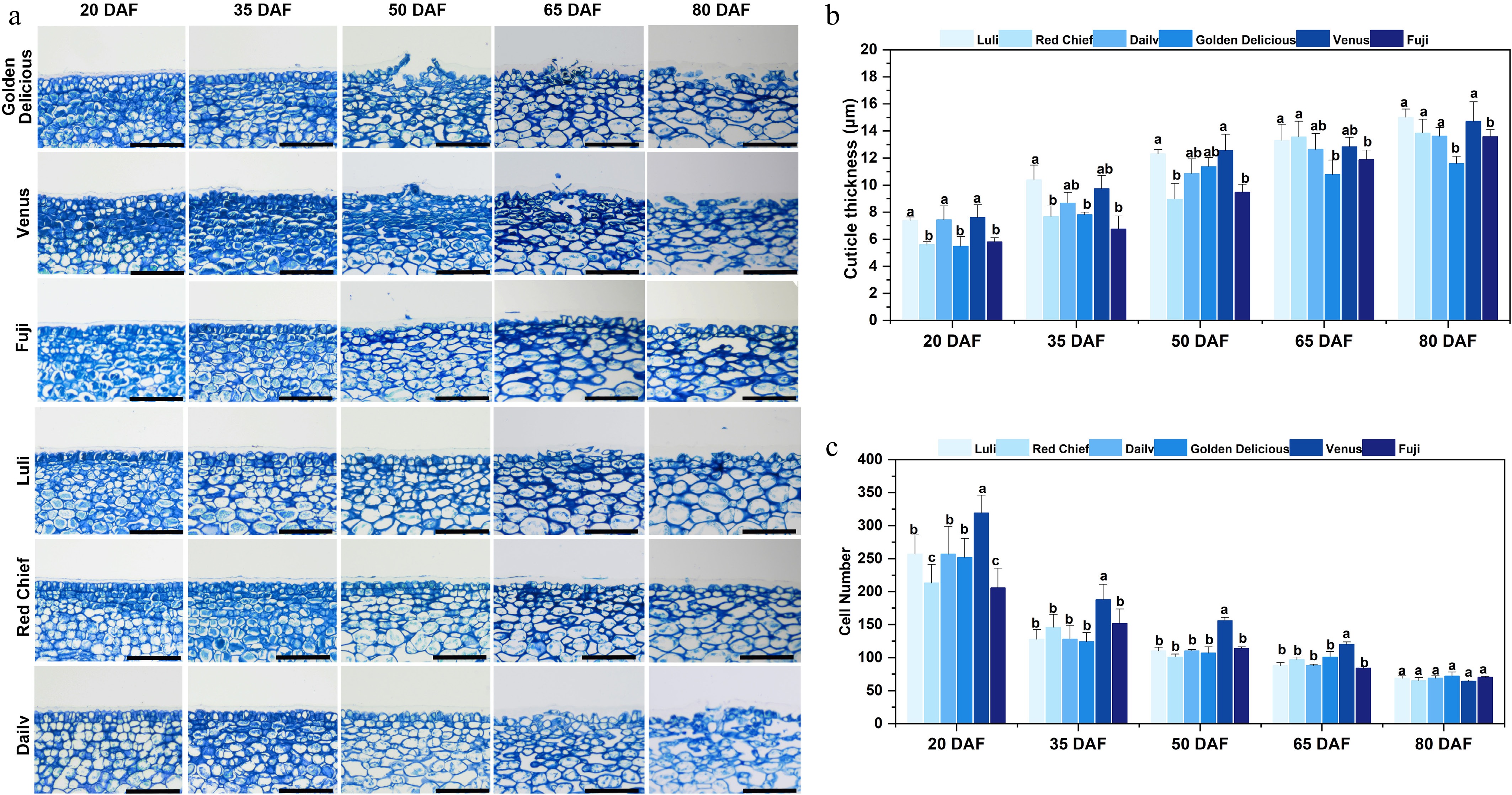

To examine cuticular changes during fruit development across different apple cultivars, pericarp paraffin sections were prepared and stained with aniline blue (Fig. 3). Notable differences in epidermal cell architecture were evident among cultivars during development (Fig. 3a). At 20 DAF, the epidermal cells of the susceptible cultivars 'Golden Delicious', 'Venus', and 'Fuji' were compactly arranged. However, as development advanced beyond 50 DAF, susceptible cultivars displayed increasing disorganization of epidermal cell layers, with locally widened intercellular spaces. In contrast, the resistant cultivars 'Luli' and 'Red Chief' maintained a uniformly compact epidermal cell arrangement throughout development, exhibiting stable cellular morphology and no evident structural disruption. After 50 DAF, the epidermal cells of 'Dailv' fruit showed localized loosening in their arrangement. However, this structural alteration was less pronounced than in highly susceptible cultivars such as 'Golden Delicious', and no large-scale tissue disruption was observed.

Figure 3.

Microscope observation and cuticle analysis of fruit epidermis of different apple cultivars. (a) Optical microscope image of a vertical section of the equatorial fruit epidermis stained with aniline blue. Scale bars represent 100 µm. (b) Cuticle thickness. (c) Cell number. Error bars represent the means ± SD (n = 3) taken from three independent biological replicates. Different letters represent significant differences (one-way ANOVA, Tukey-Kramer test, p < 0.05). DAF = days after flowering.

Fruit cuticle thickness varied significantly (p < 0.05) across developmental stages and cultivars (Fig. 3b). Specifically, Resistant cultivars 'Luli' (7.39–15.02 μm) and 'Red Chief' (5.6–13.83 μm) remained consistently thin and exhibited stable changes throughout development (20–80 DAF). In contrast, the cuticle thickness of the susceptible variety 'Golden Delicious' showed a marked increase at 50 DAF (11.37 ± 0.66 μm) and 65 DAF (10.77 ± 1.06 μm). The cuticle of another susceptible variety, 'Venus', reached a notably low mean thickness of 0.35 μm by 80 DAF. Notably, the cuticle thickness of 'Fuji' at 65 DAF (11.88 ± 0.70 μm) was significantly greater (p < 0.05) than that of the resistant cultivars, though it remained lower than that of 'Golden Delicious'. The number of epidermal cell layers gradually decreased across all cultivars as development proceeded (Fig. 3c). However, by 80 DAF, no significant differences in layer number were observed among the cultivars. It is also noteworthy that before 65 DAF, the susceptible cultivar 'Venus' exhibited a significantly higher epidermal cell density per unit area compared with the other varieties examined.

As shown in Fig. 4, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis revealed pronounced varietal differences in cuticle integrity and wax crystal morphology during fruit development. In highly susceptible cultivars ('Golden Delicious', 'Venus', 'Fuji'), the cuticle, initially intact at 20 DAF, progressively with development. Irregular cracking and deep fissures became apparent by 35 DAF and expanded to cover approximately one-third of the pericarp surface by 80 DAF. Concurrently, the epicuticular wax crystals in susceptible cultivars underwent distinct morphological shifts: initially appearing as dense, uniform rod-like structures (20–35 DAF), they progressed to fragmented plates by 50 DAF and eventually formed amorphous aggregates by 80 DAF. In contrast, resistant cultivars ('Luli', 'Red Chief', 'Dailv') maintained intact cuticles throughout development, with wax crystals preserving their initial tabular morphology. Cultivars with intermediate susceptibility, such as 'Fuji' and 'Venus' developed localized micro-cracks after 50 DAF, accompanied by partial wax crystal fusion and a rod-to-plate transition, yet without complete structural disintegration.

Figure 4.

Scanning electron microscope observation and analysis of fruit epidermis of different apple cultivars. Representative scanning electron microscopy images are shown. For each of the three biological replicates (independent fruits) per cultivar, multiple regions were examined, and the presented images best illustrate the typical morphological features observed. WL: Wax Layer. Cu: Cuticle. Mc: Microcrack. LAC: Large Area Crack. Scale bars represent 50 µm. DAF = days after flowering.

The changes in reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and antioxidant enzyme activity during the growth and development of different cultivars of apples

ROS levels

-

Russeting-resistant cultivars exhibited transient peaks or stable levels of superoxide anion content, with 'Luli' peaking at 65 DAF before declining to 45.61 nmol·g−1 by 80 DAF, whereas 'Dailv' maintained low concentrations throughout the developmental period (Fig. 5a). In contrast, susceptible cultivars displayed continuous accumulation, For instance, 'Venus' surged to 117.40 nmol·g−1 at 65 DAF, and 'Fuji' stabilized at 76.06–76.78 nmol·g−1 post-50 DAF. Key distinctions included peak values that were 2–4-fold higher in susceptible cultivars (e.g., 'Venus': 117.40 nmol·g−1 vs 'Luli': 64.82 nmol·g−1) and persistent high levels in 'Venus' versus significant reductions in resistant cultivars. Moreover, basal superoxide anion levels at 20 DAF were markedly higher in susceptible cultivars ('Venus': 57.51 nmol·g−1; 'Fuji': 56.89 nmol·g−1) than in the resistant cultivar 'Dailv' (15.59 nmol·g−1).

Figure 5.

Active oxygen metabolism and epidermal lignin/enzyme activities altered in apple cultivars during russeting. (a) Superoxide anion content. (b) H2O2 content. (c) SOD activity. (d) POD activity. (e) CAT activity. (f) Lignin content. (g) PAL activity. (h) C4H activity. Error bars represent the means ± SD (n = 3) taken from three independent biological replicates. Different letters represent significant differences (one-way ANOVA, Tukey-Kramer test, p < 0.05). DAF = days after flowering.

Russeting-resistant and susceptible apple cultivars exhibited distinctly different patterns of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulation throughout fruit development (Fig. 5b). Resistant cultivars demonstrated tightly regulated H2O2 dynamics. 'Luli' exhibited a transient peak at 35 DAF (22.25 µmol·g−1) before rapidly declining to basal levels by 80 DAF; 'Red Chief' reached its peak at 50 DAF and subsequently decreased to 4.26 µmol·g−1 by 80 DAF. While 'Dailv' gradually increased from 7.91 µmol·g−1 at 20 DAF to 14.06 µmol·g−1 at 80 DAF. In contrast, susceptible cultivars showed progressive H2O2 accumulation throughout development. 'Golden Delicious' and 'Venus' reached their peaks between 65 & 80 DAF, while 'Fuji' displayed the most pronounced increase, rising from 25.65 µmol·g−1 at 20 DAF to 74.30 µmol·g−1 at 80 DAF. Key differences included the timing and magnitude of the H2O2 peaks: resistant cultivars peaked earlier at lower concentrations, whereas susceptible cultivars peaked later at 2- to 3-fold higher levels. By 80 DAF, resistant cultivars had reduced H2O2 to near-basal concentrations (4.26–14.06 µmol·g−1), while susceptible cultivars maintained persistently elevated levels (58.29–74.30 µmol·g−1), corresponding to a 4- to 18-fold difference between the two groups. Notably, even at 20 DAF—the earliest sampling stage—the susceptible cultivar 'Fuji' already showed a substantially higher basal H2O2 level (25.65 µmol·g−1) compared with the resistant cultivar 'Dailv' (7.91 µmol·g−1).

Antioxidant enzyme activity

-

Russeting-resistant cultivars exhibit a V-shaped pattern, marked by mid-phase suppression followed by a rebound in later development (Fig. 5c). Specifically, 'Luli' and 'Dailv' showed reduced SOD activity during the middle developmental phase (50–65 DAF), which then increased significantly by 80 DAF. 'Red Chief' maintains moderate activity throughout, with a pronounced rise toward the final stage. In contrast, susceptible cultivars, such as 'Golden Delicious' and 'Fuji', displayed progressive or sustained increases in SOD activity: 'Golden Delicious' peaked at 80 DAF, whereas 'Fuji' demonstrated a steady upward trend from 20–65 DAF.

Russeting-resistant cultivars reached peaks in POD activity early (Fig. 5d) in development (20–50 DAF). 'Luli' reached its maximum activity of 363.51 U·g−1 at 20 DAF before stabilizing at reduced levels, while 'Dailv' displayed the highest early activity followed by a sharp decline to 141.44 U·g−1 by 65 DAF. In contrast, susceptible cultivars showed progressive increases in POD activity, peaking at later stages (65–80 DAF). Notably, 'Fuji' surged to 1,052.19 U·g−1 at 65 DAF, representing the highest activity across all cultivars.

Russeting-resistant cultivars exhibited more stable and developmentally coordinated patterns of CAT activity change (Fig. 5e), with 'Luli' maintaining stable activity from 20–65 DAF (27.34–34.86 nmol·min−1·g−1) before declining to 21.02 nmol·min−1·g−1 at 80 DAF. 'Red Chief' showed fluctuating activity, reaching a trough at 35 DAF and peaking at 65 DAF (46.62 nmol·min−1·g−1, a), while 'Dailv' displayed maximal activity at 35 DAF followed by a gradual reduction to 30.10 nmol·min−1·g−1 by 80 DAF. In contrast, susceptible cultivars displayed elevated yet more variable CAT activity patterns. 'Golden Delicious' and 'Venus' both showed steadily increasing activity up to 50 DAF, with 'Venus' reaching the highest activity level observed among all cultivars. Despite a lower peak, 'Fuji' aligned with susceptible trends.

Changes of epidermal lignin content and key enzyme activities during the growth and development of different apple cultivars

-

Resistant cultivars exhibited a gradual or delayed pattern of lignification accumulation, 'Luli' showed steady increases in lignin content, from 0.92 ± 0.40 mg·g−1 at 20 DAF to 2.30 ± 0.34 mg·g−1 by 80 DAF (Fig. 5f). 'Red Chief' experienced a 35 DAF trough (0.87 ± 0.24 mg·g−1) before rising steadily to 2.17 ± 0.20 mg·g−1 at 80 DAF, while 'Dailv' maintained stable levels until a late-stage increase to 1.87 ± 0.34 mg·g−1. In contrast, susceptible cultivars exhibited an accelerated and intense lignification accumulation. 'Golden Delicious' exhibited the most pronounced increase, rising from 1.51 ± 0.31 mg·g−1 at 20 DAF to 5.91 ± 0.15 mg·g−1 by 80 DAF. 'Venus' and 'Fuji' also reached substantial peaks, with lignin contents of 4.13 ± 1.08 mg·g−1 and 3.78 ± 0.47 mg·g−1, respectively.

Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity differed markedly among apple cultivars and developmental stages (Fig. 5g). Among the russeting-resistant cultivars, 'Luli' exhibited an initial increase from 198.03 ± 13.14 U·g−1 at 20 DAF to 267.86 ± 5.89 U·g−1 at 50 DAF, followed by a sharp decline to 123.86 ± 32.98 U·g−1 at 80 DAF. 'Red Chief' displayed relatively high activity at 20 DAF with fluctuations throughout, while 'Dailv' showed a peak at 20 DAF followed by a gradual decline. In contrast, the susceptible cultivars generally showed increasing trends. 'Golden Delicious' and 'Venus' exhibited progressive increases, with 'Venus' reaching the highest activity at 80 DAF (436.02 ± 34.68 U·g−1). 'Fuji' also showed an ascending pattern, peaking at 329.39 ± 16.78 U·g−1 at 80 DAF.

Cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H) activity exhibited distinct temporal patterns across apple cultivars, with clear differentiation between russeting-resistant and susceptible types (Fig. 5h). Russeting-resistant cultivars displayed earlier peaks in C4H activity at 50–65 DAF, with 'Luli' reaching 424.05 nmol·min−1·g−1 and 'Red Chief' peaking at 436.10 nmol·min−1· g−1. These peaks were followed by a decline by 80 DAF. In contrast, susceptible cultivars showed delayed peaks, with 'Golden Delicious' reaching a maximum of 922.06 nmol·min−1·g−1 at 65–80 DAF, indicating prolonged activation of phenylpropanoid metabolism under russeting stress. Russeting-resistant cultivars exhibited moderate peak activity, while susceptible cultivars displayed significantly higher enzyme activity, suggesting a stronger defense response to russeting infection. At 20 DAF, susceptible cultivars already showed elevated basal activity compared to their resistant counterparts. By 80 DAF, this disparity was further accentuated: susceptible types maintained high activity levels, whereas resistant cultivars showed a pronounced decline.

The changes of key genes involved in reactive oxygen metabolism and lignin synthesis during the growth and development of different cultivars of apples

-

This study profiled the expression of seven genes associated with russet formation (MdPOD, MdPPO, MdPAL, MdCCR, Md4CL, MdCAD, MdC4H) across five developmental stages (Fig. 6). Notably, the russeting-resistant cultivars showed higher transcript levels of oxidative stress-related genes as early as 20 DAF. MdPOD peaked in 'Luli' at 20 DAF, declining progressively to by 80 DAF. Similarly, MdPPO showed initial high activity in resistant types, contrasting with delayed activation in susceptible cultivars. Genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway (MdPAL, MdC4H, and Md4CL) were markedly up-regulated in susceptible cultivars, particularly after 50 DAF.

Figure 6.

Expression analysis of fruit russeting related genes during the growth and development of different apple cultivars. Error bars represent the means ± SD (n = 3) taken from three independent biological replicates. Different letters represent significant differences (one-way ANOVA, Tukey-Kramer test, p < 0.05). DAF = days after flowering.

Resistant cultivars activated early antioxidant defenses, as reflected by the elevated expression of MdPOD and MdPPO, which was inversely correlated with subsequent russeting severity. In contrast, susceptible cultivars displayed insufficient ROS-scavenging capacity during the early developmental phase, a deficiency that coincided temporally with the visible onset of russeting at approximately 50 DAF. While both groups activated lignin biosynthesis genes (MdCCR and MdCAD), susceptible cultivars displayed hyperactivation: MdC4H in 'Fuji' rose 6-fold from 20−50 DAF, exceeding resistant cultivars by 3.5-fold (p < 0.05). Md4CL showed stage-progressive induction in susceptible cultivars, whereas resistant types exhibited transient peaks. This reflects differential modulation of 4-coumarate-CoA ligase activity in phenolic metabolism.

Principal component analysis (PCA) and correlation analysis

PCA analysis

-

The experiment data for all cultivars were compiled and subjected to principal component analysis (PCA). As shown in Fig. 7a, b, principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) accounted for 35.3% and 13.6% of the total variance, respectively, indicating that PC1 captured the major source of variation in the dataset. The key variables contributing to PC1 were H2O2 content (0.33), lignin content (0.35), MdPAL expression (0.33), and MdCAD expression (0.33). These loadings collectively highlight the coordinated relationship between oxidative stress (reflected by H2O2 accumulation) and the transcriptional activation of lignin-biosynthesis genes. For PC2, the main contributing variables were cell number (0.46), MdPPO expression (0.44), and cuticle thickness (–0.47). These loadings collectively reflect a biological axis linked to epidermal proliferation and differentiation: higher cell number and elevated MdPPO expression are positively associated, while both show a negative correlation with cuticle thickness. Furthermore, the two groups, the russeting-resistant cultivars and russeting-susceptible cultivars, formed clearly separated clusters, indicating distinct multivariate profiles. This observation also suggested that there were statistically significant differences in the variables between the two groups.

Figure 7.

Principal component analysis between russeting-resistant and russeting-susceptible apple cultivars. (a) Principal component analysis (PCA). (b) Radar plot showing the scaled activities of TAPFs.

Correlation analysis

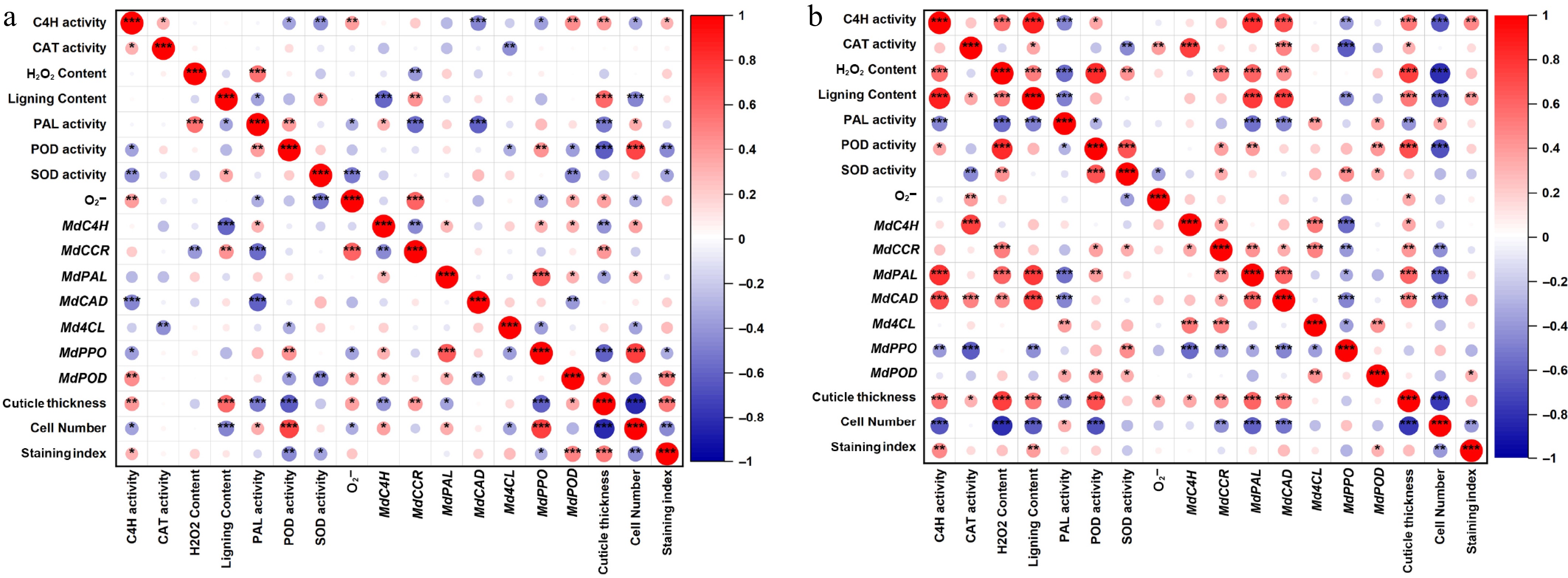

-

Correlation analysis revealed distinct regulatory patterns between russeting-resistant and susceptible apple cultivars (Fig. 8). In resistant cultivars (Fig. 8a), a tightly coordinated defense response was observed: CAT activity showed a strong positive correlation (p < 0.001) with H2O2 content, reflecting efficient ROS scavenging that maintains redox homeostasis. Concurrently, lignin content was significantly associated (p < 0.01) with the expression of its biosynthetic genes (MdPAL and MdCAD). Conversely, susceptible cultivars (Fig. 8b) exhibited a dysregulated correlation network, characterized by more extensive and stronger inter-variable associations, including notable inverse relationships, such as the significant negative correlation (p < 0.001) observed between cuticle thickness and epidermal cell number. The staining index showed strong associations with MdPPO expression, SOD activity, and the O2− levels. Notably, in susceptible cultivars, lignin biosynthesis genes (Md4CL and MdC4H) were only weakly correlated (p > 0.05) with actual lignin deposition, indicating a transcriptional-metabolic decoupling that was not observed in resistant cultivars.

-

Apple fruit russeting is a common physiological disorder characterized by a multifactorial etiology, involving both genetic determinants and environmental influences[38]. Apple russeting is commonly described as the formation of a hardened, suberized epidermal tissue that develops after the fruit's cuticle layer is compromised[32]. It is generally recognized that apple russeting develops during two distinct periods: the first period occurs during the cell division phase approximately 30 d after full bloom, and the second period takes place in the subsequent rapid fruit expansion phase (Fig. 1). This phenomenon occurs because during the peak growth phase of apple fruits, specific physiological changes cause pulp cells to expand more rapidly than the cuticle can accommodate. This discrepancy in growth rates leads to the formation of microcracks and, ultimately, to ruptures in the cuticle layer[3]. These ruptures lead to the degradation of epidermal cells on the fruit surface. In response, the damaged regions of the epidermis rapidly accumulate suberized cork cells to replace the compromised tissue and minimize water loss. The deposited cork layer, exhibiting a characteristic brown and rough texture, forms a russeted suberin-rich layer or small granular protrusions on the peel surface[39]. In this study, phenotypic assessment was conducted on three russeting-susceptible and three russeting-resistant cultivars during early fruit development (Fig. 1). Aniline blue staining of fruits and microscopic examination of paraffin-embedded epidermal sections revealed a clear divergence in russeting susceptibility among the cultivars. The critical window for russeting initiation was delineated as beginning after 50 DAF (Fig. 2).

The plant cuticle, a hydrophobic layer covering the aerial surfaces of terrestrial plants, serves as a key interface between the plant and its environment. It is essential for normal organ development and provides a critical barrier against diverse environmental stresses[40]. The apple fruit cuticle, composed of cutin polymers and waxes (including triterpenes), plays a critical role in development by preserving fruit integrity, mitigating water loss, and providing a barrier against pathogen invasion and other environmental stresses[41,42]. Cuticle formation in apple fruit is primarily regulated by transcription factors such as MdSHN3[17], while cuticle damage induces a compensatory response, where suberin deposition mediated by MdMYB93 leads to the development of russeting phenotypes[21]. Aniline blue (C32H25N3Na2O9S3) is an acid dye that exhibits solubility in water and limited solubility in ethanol. Its aqueous solution appears blue and is commonly employed as a staining agent for cells and tissues, specifically for staining the cell nucleus blue. This method assesses cuticle integrity by quantifying the surface-stained area on apple fruits, providing a predictive indicator for the risk of lenticel breakdown during storage[32]. In this study, through the observation of paraffin-embedded epidermal sections indicated that resistant cultivars, such as 'Luli' and 'Red Chief' maintain an intact epidermal structure, characterized by uniform cell arrangement and a thin, evenly distributed cuticle, which collectively contribute to their resistance phenotype (Fig. 3). In contrast, russeting-susceptible cultivars such as 'Golden Delicious' and 'Venus' displayed pronounced structural vulnerability, which was associated with disrupted epidermal development. This was evidenced by an abnormally thickened cuticle, a significant decrease in cell density, and a loosely organized tissue architecture. Furthermore, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the epidermal surface showed that susceptible cultivars developed progressive cracks in the epicuticular wax layer after 50 DAF. In contrast, the epidermis of resistant cultivars remained largely intact and smooth, which aligns with the phenotypes described earlier (Fig. 4). A critical structural divergence became evident at 50 DAF, correlating with the visible onset of russeting. This period was marked by accelerated cuticular fissuring and disorganized wax crystals in susceptible cultivars. Such structural vulnerabilities are likely to promote water loss and pathogen entry, whereas the stable cuticular architecture and well-ordered wax crystallinity in resistant cultivars provide robust and durable epidermal protection.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism is integral to multiple physiological processes in plants, including growth, development, and adaptation to environmental stress. Research has found that signaling pathways involving lignin synthesis, polyamines, and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) influence the formation of brown spots on pear fruits[20]. During epidermal lignification in fruit, ROS modulate this process by regulating the expression of key genes and the activity of associated enzymes[27,43]. ROS metabolism and antioxidant enzyme activities in the fruit peel tissues of different cultivars were measured across five developmental stages. The results revealed distinct dynamic trends between russeting-resistant and russeting-susceptible cultivars (Fig. 5a–e). These findings demonstrate that susceptible cultivars experience oxidative stress due to sustained accumulation of superoxide anions, whereas resistant cultivars maintain effective scavenging capacity, particularly during later developmental stages. Specifically, resistant cultivars maintain an equilibrium between ROS scavenging and metabolic homeostasis through finely tuned regulation of SOD, POD, and CAT activities. In contrast, susceptible cultivars exhibit a compensatory response characterized by the persistent upregulation of these enzymes to counteract escalating oxidative stress.

Fruit russeting develops primarily from excessive lignin deposition through the phenylpropanoid pathway, in which PAL catalyzes the synthesis of cinnamic acid and thereby promotes lignin biosynthesis. As the pathway's initiator, PAL coordinately regulates the production of both antioxidative scavengers and lignin precursors, thereby linking metabolic flux to russeting susceptibility[28,44]. Lignin produced via the phenylpropanoid pathway undergoes polymerization into lignin, catalyzed by POD and PPO. As a key enzyme in lignin biosynthesis, POD activity has been shown to significantly promote the intracellular accumulation of lignin[27,45]. 4-coumaric acid: CoA ligase (4CL) is a key enzyme in the phenylalanine pathway, acting as a central node that channels hydroxycinnamic acids (such as p-coumaric, caffeic, and ferulic acids) toward lignin biosynthesis. It catalyzes the formation of their corresponding CoA esters, thereby driving the production of lignin monomers[45]. This study reveals key distinctions in epidermal lignin metabolism between russeting-resistant and russeting-susceptible apple cultivars. Resistant cultivars maintain metabolic homeostasis through developmentally staged regulation of phenylpropane enzyme activities, whereas susceptible cultivars undergo excessive lignification as a result of pathway imbalance (Fig. 5f–h). In resistant cultivars, early peaks in PAL and C4H activity at 50–65 DAF likely strengthen the epidermal barrier through precisely timed lignin deposition, followed by a decline that prevents over-accumulation. Conversely, in susceptible cultivars, PAL and C4H activities rise persistently, driving a substantial increase in lignin biosynthesis. This excessive lignification is proposed to induce epidermal hardening and microcracking, ultimately compromising cuticular integrity (Fig. 6). Significantly, the delayed peak of C4H activity (65–80 DAF) in susceptible cultivars correlates with sustained oxidative stress, indicating that ROS may promote lignification through the upregulation of phenylpropane metabolism. Furthermore, multivariate analyses revealed fundamental divergences in russeting resistance mechanisms. PCA clearly separated resistant and susceptible cultivars (Fig. 7), a differentiation primarily attributed to the coordinated activation of H2O2 and lignin biosynthesis pathway. This functional coordination was further validated in resistant cultivars by the tight coupling between CAT activity and H2O2 levels, together with correlated induction of lignin biosynthesis (Fig. 8). In contrast, susceptible cultivars display dysregulation of this integrated metabolic network. Collectively, these results establish coordinated phenylpropanoid-ROS homeostasis as a defining characteristic of russeting resistance, whereas susceptibility stems from disrupted developmental regulation, ineffective gene-metabolite coordination, and persistent oxidative imbalance.

-

This study demonstrates that apple russeting results from genotype-by-environment interactions that lead to multidimensional physiological dysregulation. The principal findings are as follows: (1) The period around 50 DAF represents a critical developmental window, during which coordinated cuticular reorganization, ROS accumulation, and genetic variations collectively impair epidermal integrity in susceptible cultivars; (2) In susceptible cultivars, delayed or insufficient antioxidant responses fail to neutralize ROS surges, allowing ROS levels to exceed cellular tolerance thresholds and thereby induce programmed cell death; (3) Resistant cultivars deploy a biphasic defense strategy: an early phase of efficient ROS scavenging to maintain redox homeostasis, followed by a subsequent downregulation of lignification-related genes to prevent excessive suberization; (4) These findings offer practical implications for apple production, including the use of cuticular microcrack indices and MdPAL expression levels as biomarkers for russeting resistance. Additionally, timed interventions—such as applying ROS scavengers or employing gene-modulating strategies around the critical 50 DAF window—could help mitigate disorder incidence. This work not only informs future apple breeding programs but also contributes to the development of more sustainable orchard management practices.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2023YFD2301000), Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (Grant No. ZR2024JQ036), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32272683), and China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (Grant No. CARS-27).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wang X, Li L; experimental work and technical assistance: Li C, Wang Y; data collation and analysis: Li C, Sun YL, Qin XH, Su J; sample culturing and collection: Li C, Li X, Dong H, Zhang W; draft manuscript preparation and revision: Li C, Yue QY, Zhang T, Wang HB, Li L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Primers used in this study.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li C, Wang Y, Sun YL, Qin XH, Su J, et al. 2026. The periodicity of fruit russeting occurrence and the morphological changes in the epidermis across different stages of apple growth. Fruit Research 6: e005 doi: 10.48130/frures-0025-0044

The periodicity of fruit russeting occurrence and the morphological changes in the epidermis across different stages of apple growth

- Received: 12 November 2025

- Revised: 08 December 2025

- Accepted: 15 December 2025

- Published online: 02 February 2026

Abstract: Russeting is a significant limiting factor affecting the superficial quality of apple fruits, and it is important to understand the formation mechanism of apple russeting for improving fruit appearance quality. In this study, six representative cultivars were selected to systematically investigate the russeting formation during early fruit development through multidimensional analyses. Findings demonstrated that russeting predominantly manifests at 50–65 d after flowering (DAF), a period coinciding with dramatic cuticular reorganization. Susceptible cultivars exhibited disintegration of wax crystals and disordered epidermal cell arrangements, whereas resistant cultivars maintained stable cuticular morphology. A critical redox imbalance was observed in susceptible cultivars, characterized by excessive hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulation and dysregulated antioxidant enzyme activities, indicating a collapse of reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging systems. Notably, susceptible cultivars exhibited hyperactivation of lignin biosynthesis genes. While the resulting lignin deposition showed a positive correlation with the severity of epidermal damage, suggesting that such maladaptive or excessive lignification disrupted a relatively stable physiological state. Overall, these findings offer potential molecular markers for breeding programs and a theoretical foundation for developing targeted control strategies.

-

Key words:

- Apple russeting /

- Cuticle /

- Key period