-

Bigels[1] act as better alternatives to the conventionally used solid fats[2], as conventional saturated fats have been found to be harmful to human health. Bigels are semisolid substances formed by a mixture of an aqueous and an oil phase[3]. They trap liquid oil in a three-dimensional gel matrix-like structure, offering a texture that is very similar to conventional saturated trans fats[4]. Bioactive bigels[4] enhance the texture of a compound, with the additional benefits of drug delivery and antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, and they act as a healthier alternative with high nutritious value. There is an alarmingly increasing demand for ingredients that harmless and also add additional health benefits[5], a criterion which most conventionally used saturated fats fail to fulfill. Bioactive bigels are considered to be a better alternative to conventionally used unhealthy saturated fats[6], as they have significantly reduced saturated fatty acids, enhanced nutritional value, and good oil-binding capacity. Recent efforts to replace saturated fats have explored bigels derived from rice bran wax or beeswax as butter substitutes and fat replacers in bakery products[7]. However, bigels prepared with conventional wax-based oleogelators often exhibit excessive adhesiveness and firmness[8], which may limit consumer acceptance. To overcome these drawbacks, researchers have begun investigating preparation techniques that avoid synthetic emulsifiers or traditional oleogelators by, for example, incorporating nonconventional starches with beeswax[9]. However, studies that completely eliminate conventional wax oleogelators while enhancing functional properties through using bioactive plant sources remain scarce. The present work is the first to report bigels formulated without any conventional wax oleogelators, instead using phytoflavone-rich jamun (Syzygium cumini or S. cumini) seed waste and Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (H. rosa-sinensis) petals to achieve both structural integrity and biofunctional enhancement. Though most previous studies have focused mainly on textural, physical, or baking performance[10], very few have investigated direct butter substitutes for direct consumption (rather than for use in baking[11]) that combine a plant-derived hydrogel such as aloe vera with rice bran oil (RBO) as the continuous oil phase. Our approach therefore provides a novel pathway to develop consumer-acceptable, plant-based bigels with superior antioxidant and antimicrobial functionality, advancing the field of healthy fat replacements. In this research, jamun (S. cumini) seed extract and hibiscus (H. rosa-sinensis) flower petal powder extracts were used[12]. Jamun[13] is known for its antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory properties; hibiscus is rich in antioxidants and is beneficial to the cardiovascular system. These biological extracts improve the stability, texture, smell, and taste of bigels[8], thus reducing the requirement for an artificial extract that causes harmful effects on the human body following its consumption[12]. In food formulations, bigels are becoming more and more popular as healthy substitutes for trans and saturated fats[14]. Gel stability and performance are influenced by structural characteristics. Jamun[15] and hibiscus were chosen because of their antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. Rice bran oil is used because of the presence of oryzanol, which has strong antioxidant properties[16]. Here, the physical, chemical, and oxidative stability are assessed over time under various environmental and storage circumstances as part of the stability studies. Stability is evaluated using antioxidant studies, which help in assessing ability of bigels to prevent the oxidation of the oils and active ingredients, preserving their physical, chemical and therapeutic properties. Optimizing the formulation techniques for targeted distribution, enhanced shelf life[17], and functional performance requires an understanding of stability over various gel dimensions. Antimicrobial studies were done to ensure that the bigel can resist contamination by microbes during storage, which ultimately enhances shelf life and user safety[18]. Evaluating its ability to scavenge free radicals and to inhibit common microbial pathogens aids in assessing their multifunctional capability to be used as an alternative in the food, pharmaceutical, biomedical, and even skin care industries[19]. Bioactive bigels[20] retain the properties of solid fats while being an unsaturated plant oil, thereby offering health benefits[21]. Incorporating these bioactive bigels may enhance their ability to act as a fat replacement for daily use[22]. Their structure and properties are influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic parameters, and these factors are vital to achieve the desired texture to make it marketable.

-

Fresh hibiscus flower petals and jamun seeds were collected locally, washed, and shade-dried. RBO was used as a liquid base for preparation of both the bigels. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) were procured from certified suppliers. Nutrient agar, Muller Hinton agar, and standard common bacterial strains (Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli) were used for antimicrobial testing.

Preparation of extracts

-

Jamun (S. cumini) seeds were shade-dried and crushed to obtain jambolan extract, whereas hibiscus flower petals were shade-dried and crushed into powder. Ten grams of each component was weighed and stored separately. Additionally, aloe vera gel was extracted from fresh aloe vera leaves and added to the hibiscus petal powder.

Bigel formation

-

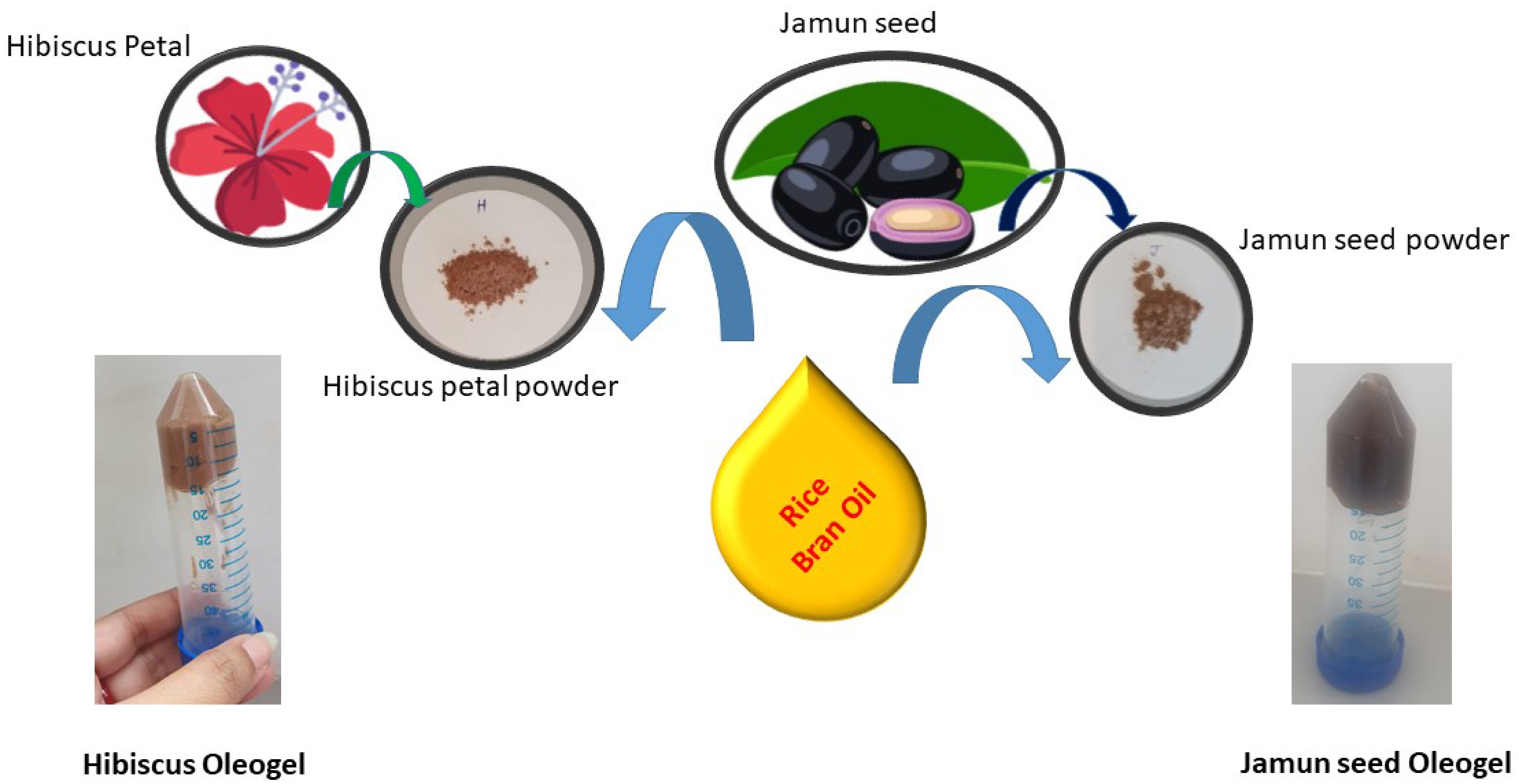

Two separate bigel formulations were developed: a jamun seed-based bigel (JBg) and a hibiscus-based bigel (HBg). Both were produced by sequential preparation of the oleogel and hydrogel phases, followed by controlled mixing. The schematic illustration of Bigel preparation is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Oleogel Phase: For JBg, the oleogel was prepared by dispersing jamun seed waste (8%–9% w/w) and soluble starch (a structuring/stabilizing agent) in RBO (91%–92% w/w) containing 10 mL glycerin. The mixture was heated to 80 °C under continuous stirring at 500 rpm until complete dissolution, following the procedure of Shakouri et al.[8], with minor modifications. The HBg oleogel was prepared identically, substituting hibiscus petal powder for jamun seed waste.

Hydrogel Phase: Fresh aloe vera gel (10 g) was dispersed in 50 mL of deionized water and heated to 70 °C under constant stirring at 1,000 rpm for 1 h. Propyl paraben (0.02% w/w) was incorporated as a preservative to inhibit microbial growth.

Bigel Formation: After overnight cooling of both phases, the hydrogel (HG) was gradually incorporated into the oleogel (OG) at oil–hydrogel (OG : HG) ratios of 30:70, 50:50, and 70:30. Mixing was performed with a mechanical hot plate stirrer at 600–1,000 rpm for 2 min at ambient temperature to achieve uniform emulsification.

Storage and Stability: The resulting bigels were transferred to sterile plastic containers, stored at 4 °C for 24 h to ensure structural setting, and subsequently maintained at 25 °C prior to testing. Their structural integrity and the absence of phase separation were confirmed by tube inversion analysis.

The response surface methodology (RSM) was used to optimize the concentrations of bioactive extracts and rice bran oil, and to evaluate the interactive effects of the formulation variables. This statistical approach enabled a systematic understanding of the compositional interactions, minimized experimental redundancy, and provided insights into the structural behavior and performance of the developed bigels. The RSM was used to check the oil-binding capacity of the Hbg. Here, the main parameters that were considered were the amount of the oleogel phase (rice bran oil, i.e., 0.2–5.0 g) and the hydrogel phase (aloe vera, i.e., 0.3–7.5 g, and oil-binding capacity (OBC), which was physically measured in the laboratory. We varied both the phases, keeping the amounts of hibiscus petal powder, glycerin, and soluble starch the same in each run for 30 times using Design-Expert 8.0.6. This method will be useful for future research to understand which composition will have higher oil-binding capacity, and laborious steps in laboratory experiments can be avoided by directly using that composition from the furnished results, as OBC is one of the prime characteristics of bigels or oleogels that could be used for further applications.

-

The microstructure of the bigel plays a vital role in maintaining texture, stability, functionality, spreadability and oil-binding capacity. It can be visualized via optical microscopy. This method has the advantage of being a rapid method for observing the internal structure. It provides real-time monitoring. A drop of the prepared bigel was placed on a glass slide with a coverslip and was observed under an optical microscope. Digital pictures of the sample were taken to analyze the structure, uniformity, and density.

Oil-binding capacity

-

The OBC of the bigel evaluates the ability of the bigel to retain oil within its structure without separation. A higher OBC indicates better structural integrity, which is essential for the stability and shelf life of the formulation. For this, 2 g of the prepared bigel was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 30 minutes. After centrifugation, the clear supernatant oil was removed carefully and weighed. The results were calculated using the following formula:

$ \rm OBC\;({\text{%}})=[(W_2- W_3)/(W_2-W_1)]\times 100 $ where, W1 is the empty centrifuge tube's weight (g), W2 is the weight of the tube and bigel before centrifugation (g), and W3 is the weight of the tube + gel after removing the released oil (g).

The RSM, an optimization process technique, was also run to check the approximate accuracy of oil-binding capacity (see Supplementary Fig. S1), considering the quantity of aloe vera and rice bran oil as crucial parameters in these biphasic gels[23].

Spreadability

-

Spreadability was assessed by placing 10 g of the prepared bigel on a horizontal glass slide. A standard weight of 500 g was placed on the glass slide on top of the bigel and allowed to rest for 1 min to ensure uniform spreading. The distance by which the bigel spread per second was measured with respect to the amount of bigel placed. The values were applied to the following formula to obtain the values of spreadability:

$ \rm Spreadability\;(S)=(M\times L)/T $ where, S is the spreadability (g·cm·s−1), M is the weight applied to the upper slide (g), L is the length to which the sample spread (cm), and T is the time taken to spread (s).

Swelling ratio

-

The density and porosity of the bigel is determined by its capacity to absorb water. For this 1 g of the bigel was placed in 10 mL of distilled water at room temperature for 1 hour and left undisturbed. Later, the bigel was carefully blotted on filter paper to remove excess water, and the swollen sample was weighed. The swelling ability of the bigel was calculated using the following formula:

$ \rm Swelling\;Ratio\;({\text{%}})=[(W_2 - W_1)/W_1]\times 100 $ where, W1 is the initial weight of the undisturbed bigel (g) and W2 is the final weight of the swollen bigel after immersion (g).

FTIR

-

FTIR (Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy) analysis was performed to determine which functional groups were present and to verify whether the plant-based bioactive chemicals were incorporated into the bigel matrix.

Antioxidant activity

-

The antioxidant activity of hibiscus and jamun seed bigels was evaluated by DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging assays. For DPPH, a 0.1-mM stock solution of DPPH was prepared in methanol and freshly diluted to 20 µM for each test. Different concentrations of bigel methanolic extracts (10–50 µg·mL−1 as the final concentration) were added to 200 µL of the DPPH working solution in 96-well plates and incubated for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm against a methanol blank. The percentage scavenging activity was calculated as [(Acontrol – Asample)/Acontrol × 100], where Acontrol is the absorbance of the DPPH solution without the sample. For the ABTS assay, ABTS radical cations (ABTS+) were generated by reacting 7 mM ABTS in 50% ethanol with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate in water and storing the mixture for 24 h in the dark at 4 °C, then diluting it with 50% ethanol to an absorbance of 1.0 ± 0.02 at 734 nm. In 96-well plates, 250 µL of this ABTS+ solution was mixed with 20 µL of bigel extract (10–50 µg·mL−1 as the final concentration) and incubated for 10 min in the dark. The absorbance was recorded at 734 nm using 50% ethanol as a blank. The percentage inhibition was determined as [(Abs0 – Abs1) / Abs0 × 100], where Abs0 is the absorbance of the blank and Abs1 is the absorbance with the bigel extract. Ascorbic acid at the same concentrations served as the positive control for both assays. All the experiments were recorded in triplicate.

Antimicrobial efficacy

-

The agar well diffusion method was used to measure the antibacterial activity of the prepared bigels in order to determine their potential as natural antimicrobial agents for use in food preservation. Gram-positive S. aureus and Gram-negative E. coli, two representative bacterial strains frequently linked to foodborne disease and skin infections, were chosen for the investigation.

Fresh bacterial cultures were cultivated for 18–24 h in a nutrient broth before being standardized to a turbidity of a 0.5 McFarland standard, or roughly 1.5 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU) mL−1. The corresponding bacterial suspensions were produced and evenly inoculated into Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) plates using sterile cotton swabs. A sterile cork borer was used to punch wells with a diameter of 6 mm into the agar. Then, 25, 50, or 100 µg·mL−1 of each bigel formulation was added to the three agar wells. The plates were incubated in a mechanical incubator in an aerobic environment for 24 h at 37 °C to observe the microbial growth. Using a digital vernier caliper, the diameter of the zones of inhibition surrounding each well was determined in millimeters after incubation. Antimicrobial activity was demonstrated by a distinct inhibitory zone. For the antibacterial activity test amoxyrite was used as a standard, and for the antifungal activity test, fluconazole was used. For this experiment, 100 µL of the microbial culture was swabbed onto petri dishes. Biosafety was maintained as per safety guidelines, as the whole experimental procedure was conducted in clean ultraviolet (UV) laminar chambers with proper regulations.

Application of HBg and JBg

-

In order to explore the practical usability of the formulated oleogels, the HBg and JBg were evaluated as potential butter substitutes. The gels were directly applied on freshly baked bread slices slices to assess their spreadability, texture, color, and sensory appeal in comparison with commercial butter. This preliminary application study aimed to evaluate the consumer acceptability and functional behavior of the developed gels under real food conditions before considering their large-scale production.

Ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometry test of stability test

-

The stability of the samples was evaluated using UV–visible spectrophotometry. Both freshly prepared JBg and 6-month-old JBg samples were analyzed to assess any possible degradation or formation of oxidation products. The absorbance spectra were recorded within the wavelength range of 200–700 nm. This analysis aimed to determine the presence or absence of primary, secondary, or conjugated diene oxidation products, which serve as indicators of oxidative or structural changes over the storage period. Visual, pH, and microstructural changes were recorded.

Statistical analysis

-

All experiments were carried out in triplicate. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software. Mean differences were determined with a significance level of p < 0.05.

-

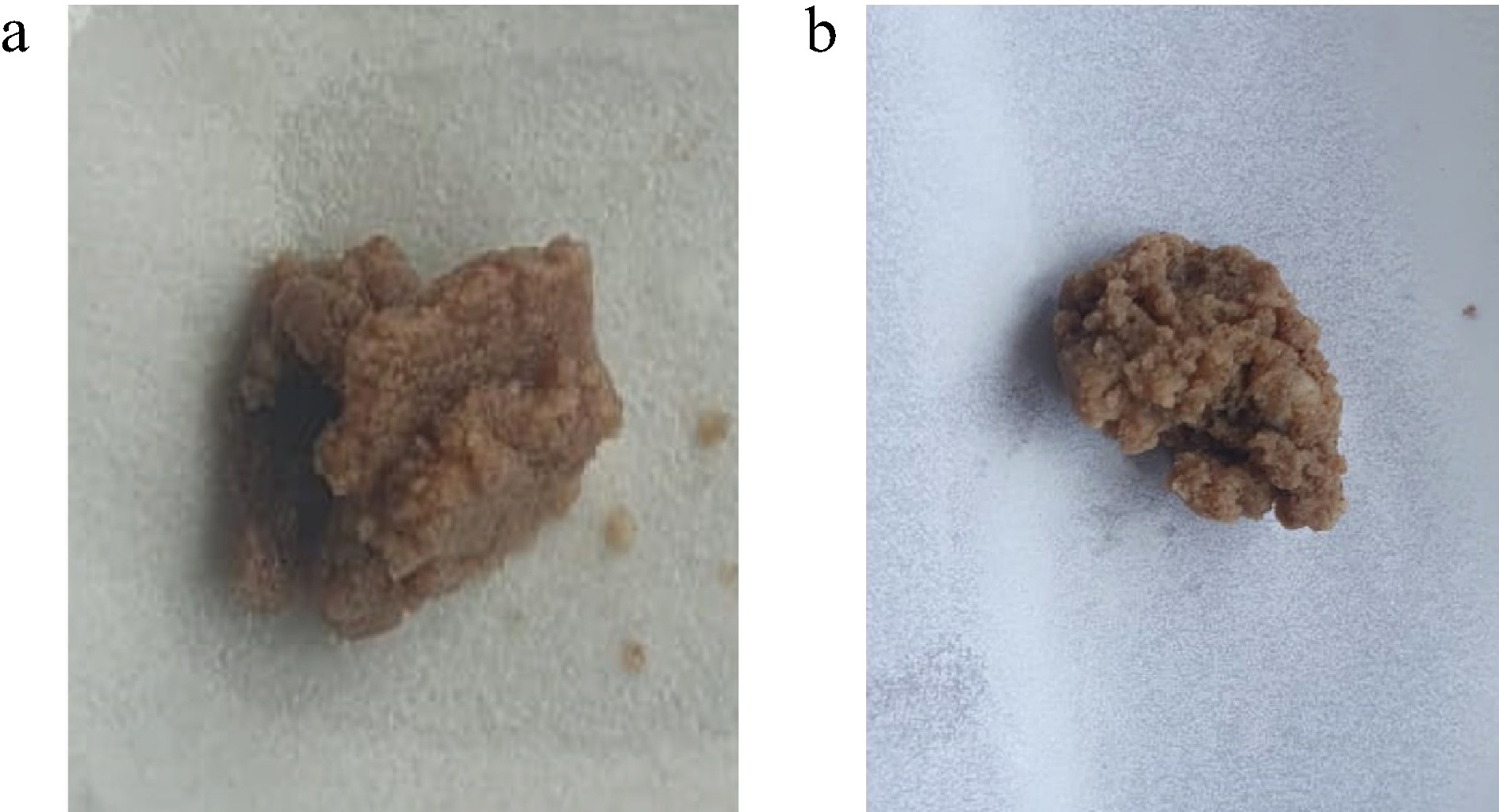

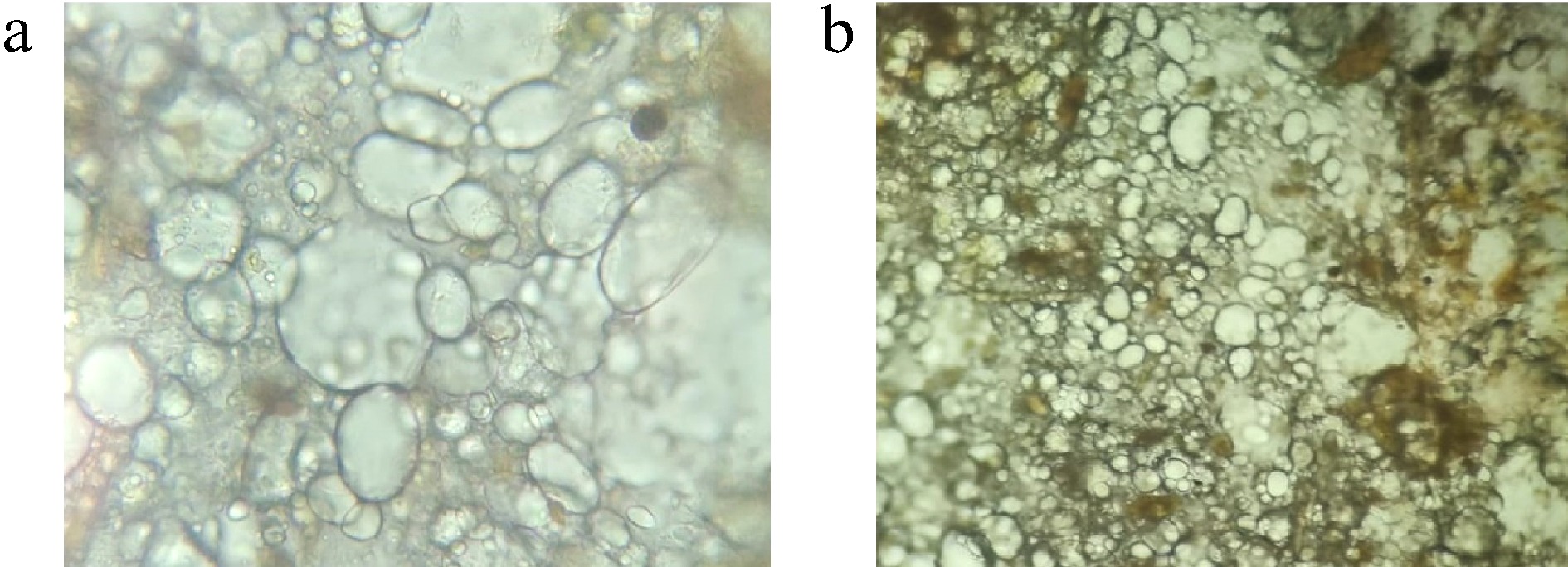

Under optical microscopy, HBg has even, spherical, transparent globules with an appealing structure that is suitable for consumption, and no aggregation was observed (Fig. 2a). JBg showed thick, coarse, spheroid, irregular, and uneven globules that are not suitable for consumption (Fig. 2b). A similar smooth globular structure was observed in soya lipophilic protein-based oleogel in which thyme essential oil was encapsulated, as reported by Sun et al.[24]. Our report also aligns with Andonova et al., where the smooth morphology of a bigel prepared from carbopol hydrogel/sorbitan monostearate almond oil was reported[25].

Figure 2.

(a) Optical microscopic picture of the morphological characteristics of HBg. (b) Optical microscopic picture of the morphological characteristics of JBg.

Oil-binding capacity and spreadability

-

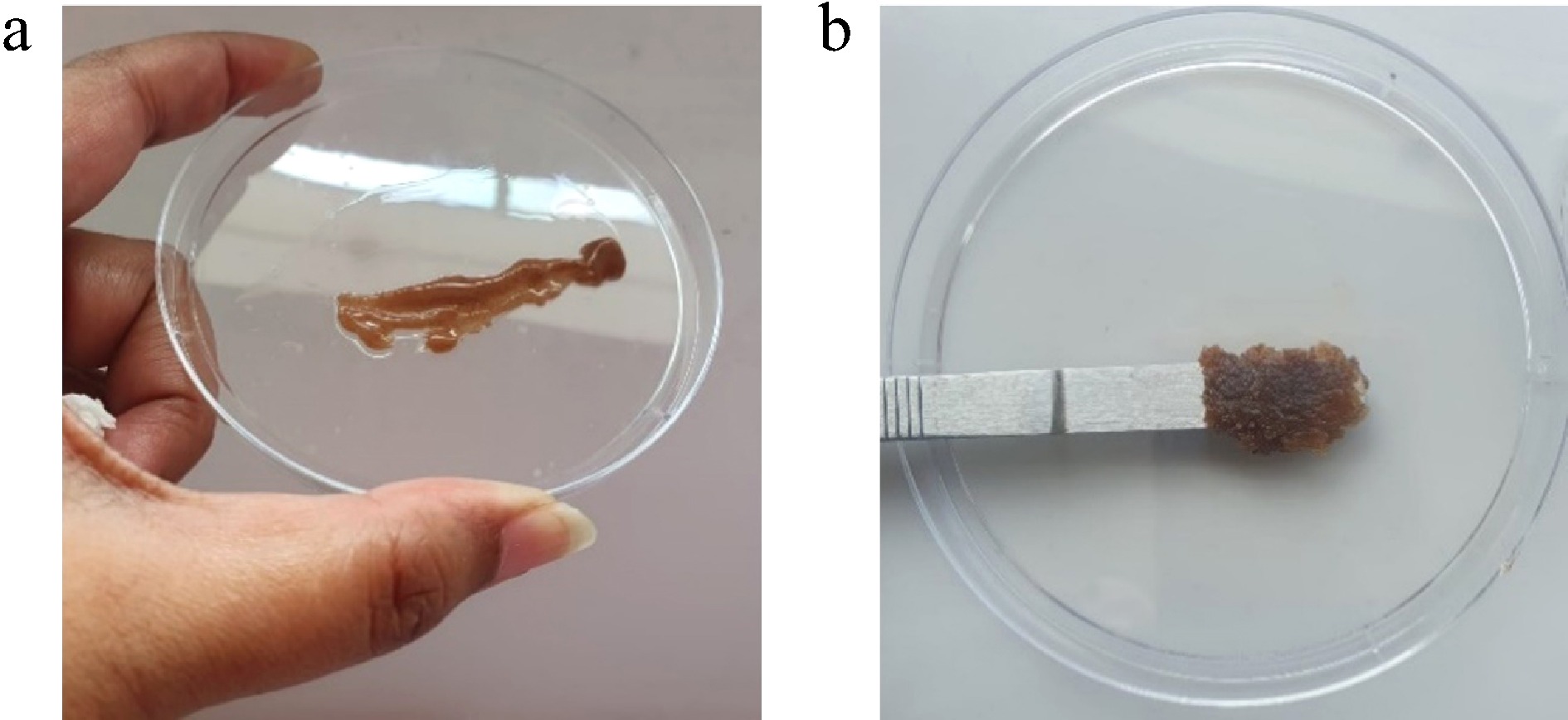

Hibiscus bigel binds 79% of oil, making it suitable for consumption as a fat replacement. The OBC of hibiscus bigel increased with an increase in the quantity of RBO (Fig. 3a). There was a clear influence of RBO on the OBC of the bigel. The highest OBC was observed with high RBO and low aloe vera (Supplementary Fig. S1). Compared with JBg, HBg demonstrated a greater spreadability value (Table 1). This could be explained by the fact that hibiscus bigels exhibit a finer and more consistent microstructure when viewed bia optical microscopy, which facilitates the gel's easier deformation under pressure. A softer texture and better application indicate higher spreadability. Jamun seed bigels, on the other hand, may have a somewhat lower spreadability because of a denser and more compact gel matrix, which increases internal flow resistance, asobserved in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

(a) HBg's spreadability is smooth and homogeneous. (b) JBg's spreadability showed coarse granules and it was difficult to spread.

Table 1. The spreadability of both bigels.

Bigel type Distance moved (cm) Time (s) Applied weight (g) Spreadability (g·cm·s−1) Hibiscus petal bigel 11.2 15 500 (500 × 11.2) / 15 = 373.33 Jamun seed bigel 9.6 15 500 (500 × 9.6) / 15 = 320.00 Swelling ratio

-

The swelling ratio shows how well the bigel absorbs water, which is a reflection of the gel network's hydrophilicity and crosslinking density. In this investigation, the swelling ratio of HBg was higher than that of JBg (Table 2). Because of the nature of the polyphenolic interactions of the hibiscus flower petal powder, this implies that the gel matrix has a more open or absorbent network. A greater swelling index indicates improved fluid retention, which is beneficial for consumers' acceptance of the products[26]. Conversely, JBg exhibited less swelling behavior, which could lead to increased mechanical stability and resistance to structural degradation when exposed to moisture. Figure 4 presents the swelling ratio of both the bigels. Our results align with those of Zhou et al.[27], who observed that the ratio of oleo gels and hydrogels impact the physical properties of the gels.

Table 2. The swelling ratio of the bigels.

Bigel type Initial weight

(W0)Weight after swelling (Wt) Swelling ratio (%) HBg 1.00g 2.85 (2.85 − 1.00) / 1.00 × 100 = 185% JBg 1.00g 2.30 (2.30 − 1.00) / 1.00 × 100 = 130% Antioxidant assay

-

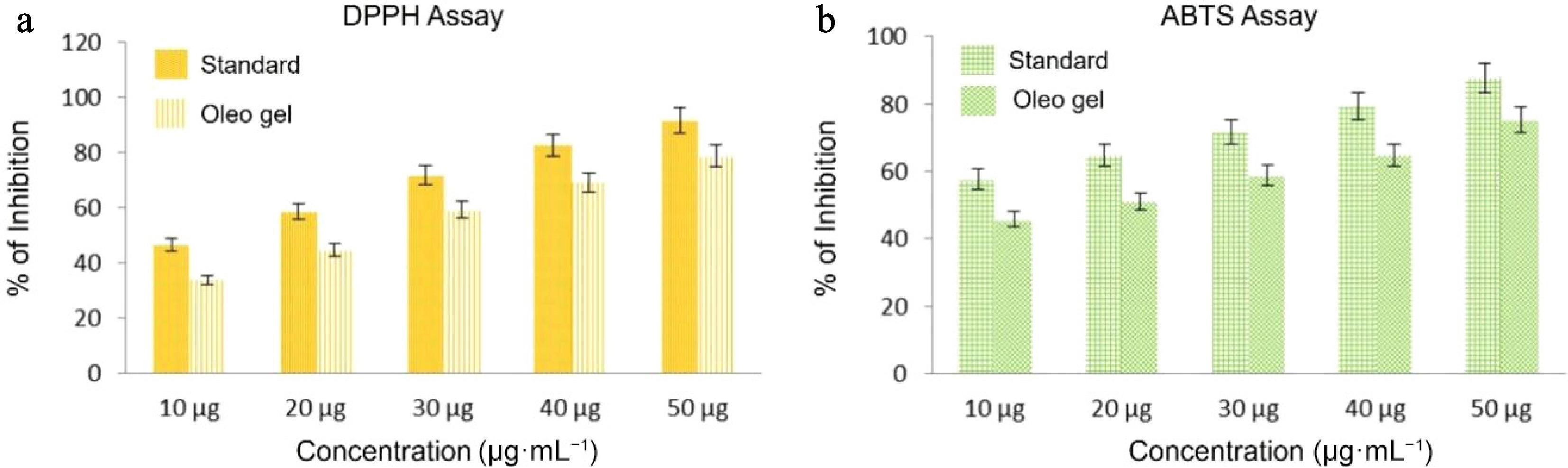

The DPPH assay results indicate that the antioxidant activity of the HBg and the standard increased in a concentration-dependent manner. With increasing concentration, the HBg demonstrated progressively greater inhibition, as Table 3 and Table 4 illustrate. The Hbg showed 33.88% inhibition at 10 µg·mL−1, rising to 78.83% at 50 µg·mL−1 for DPPH as shown in Fig. 5a. This is similar to the standard at this dose (91.81%). As a result, Hbg has significant ability to scavenge radicals, which is comparable with the effectiveness of the common antioxidant used as a benchmark. It has been suggested that hibiscus extracts can offer antioxidant protection at different dosages because the activity was much decreased at lower concentrations (10 and 20 µg·mL−1) but still showed some degree of antioxidant potential.

Table 3. DPPH assay.

Concentration (µg·mL−1) Standard (%) Bigel (%) 10 46.72 33.88 20 58.65 44.9 30 71.85 59.29 40 82.64 69.21 50 91.81 78.83 Table 4. ABTS assay.

Concentration (µg·mL−1) Standard (%) Bigel (%) 10 57.65 45.71 20 64.81 51.06 30 71.65 58.82 40 79.33 64.69 50 87.61 75.16 There was a similar concentration-dependent rise in inhibition in the ABTS assay data, as shown in the image (Fig. 5b). The inhibition of the HBg was 45.71% at 10 µg·mL−1 and 75.16% at 50 µg·mL−1. With the inhibition approaching that of the standard at higher concentrations, these findings imply that HBg has a potent ability to neutralize ABTS radicals. The finding that hibiscus bigels are strong antioxidants with good efficacy at moderate to high concentrations is supported by the constant pattern of the inhibitory trend from 10 to 50 µg·mL−1. The reported DPPH scavenging activity in the present case is better than that found by Akl et al.[28]. These researchers reported 74.4% scavenging activity for a pumpkin seed oil-based bigel fortified with various extracted canola bioactives which is less than than of our HBg sample, which reported 78.8%. However, in the case of ABTS scavenging activity, their pumpkin seed bigel reported 15% higher efficacy than our HBg[28]. Similar strong antioxidant activities in glyceryl monostearate-based oleogels encapsulated with tea polyphenols were reported by Chen et al.[29]. In their research on a dihydroquercetin and epicatechin-encapsulated diacylgylcerol-based oleogel, Hu et al.[30] observed very strong free radical scavenging activities in DPPH and ABTS assays. Almost 60%–80% efficacy was observed in both cases. HBg outperformed the norm in both tests, demonstrating that it is a dependable alternative. Because of the increased demand for naturally derived antioxidants, this is particularly crucial for applications in fat replacers or fortified consumer products. Another interesting finding was reported by Baltuonytė et al., namely that pure oleogels are more susceptible to oxidation than bigels; i.e., they have more better oxidative stability when the hydrogel is re-enforced with carnauba wax oleogel[31], which aligns with our report, as our bigels are composed of two phases (aloe vera as the aqueous phase and RBO as the oil phase).

Antimicrobial efficacy

-

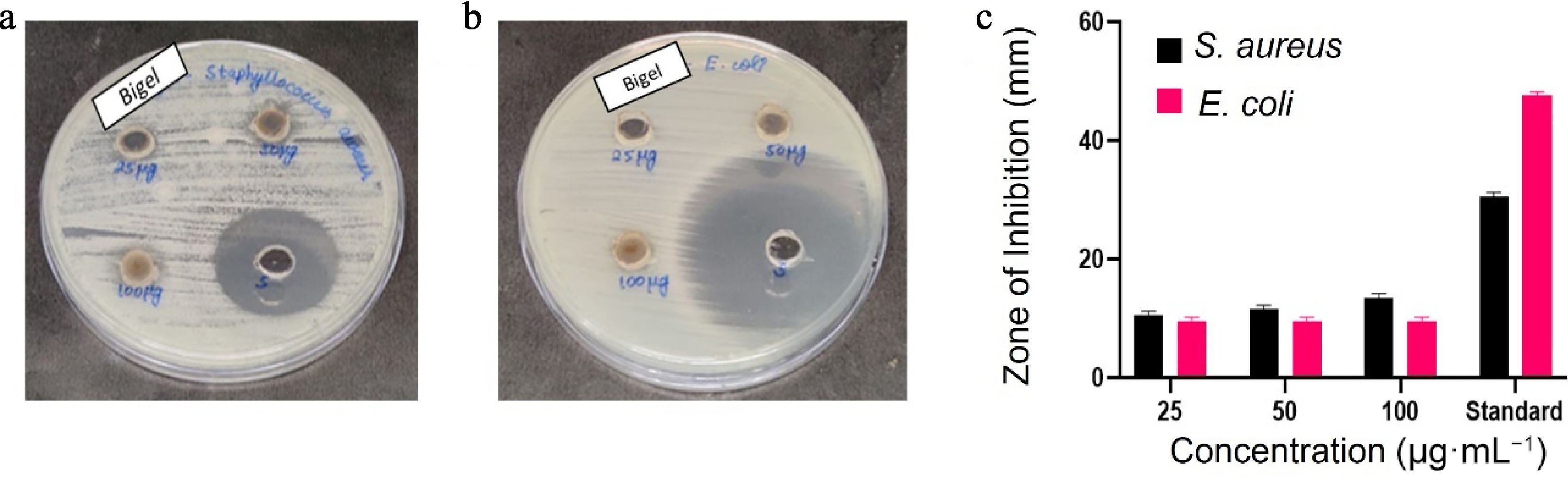

Compared with E. coli, the HBg was more effective against Staphylococcus aureus and showed modest, concentration-dependent antibacterial activity (Fig. 6a, b). In the well diffusion assay, E. coli inhibition zones stayed at 9 mm at all concentrations, whereas the S. aureus inhibition zones grew from 10 (25 µg·mL−1) to 13 mm (100 µg·mL−1). This implies that Gram-positive bacteria are more sensitive, most likely as a result of bioactive chemicals penetrating more readily (Table 5). The positive control was amoxicillin, for which the concentration was a bit high, so the control zone was much greater than that of the test samples.

Figure 6.

(a) Zone of inhibition in S. aureus. (b) Zone of inhibition in E. coli. (c) Bar graph showing different zones of inhibition at different concentration of HBg.

Table 5. Zones of inhibition for S. aureus and E. coli for various concentrations of HBg and the standard.

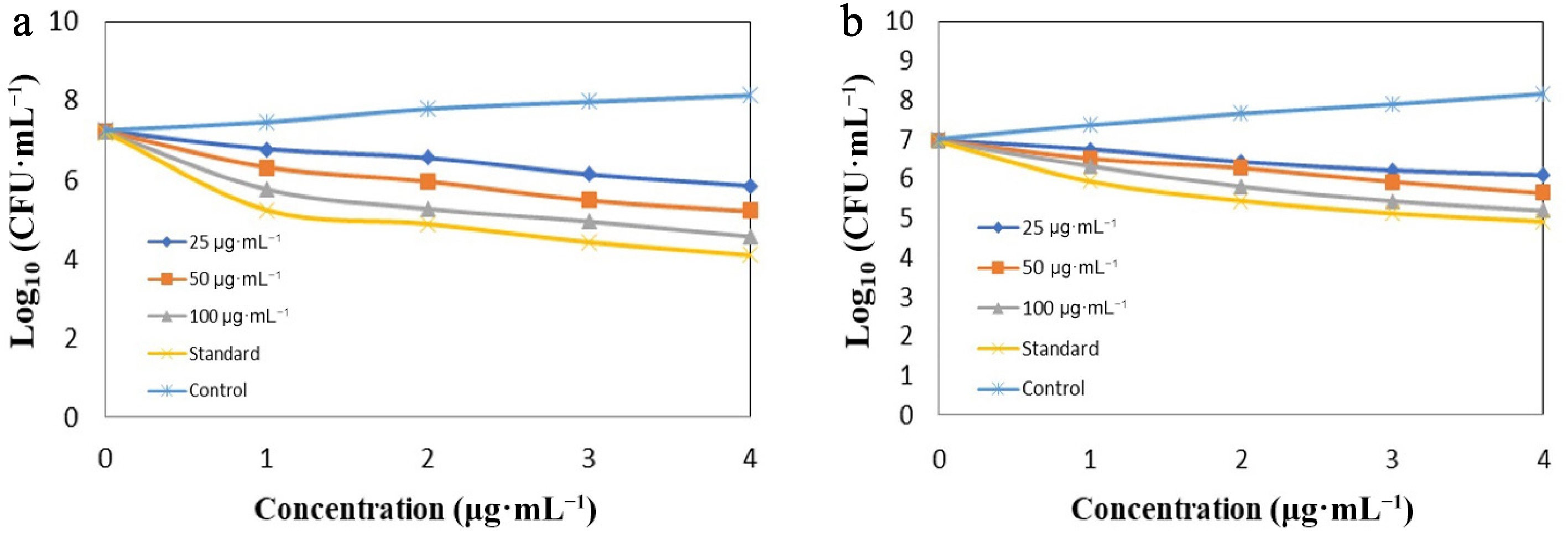

HBg 25 (µg·mL−1) 50 (µg·mL−1) 100 (µg·mL−1) Standard (µg·mL−1) S.aureus 10 11 13 30 E.coli 9 9 9 47 Our report aligns with that of Zhang et al., where the bigel exhibited more inhibition in case of S. aureus (the zone of inhibition was 14–16 mm) compared with E. coli (10–14 mm)[32]. In contrast to the case of E. coli, which exhibits very mild sensitivity under the same conditions, HBg exhibits quick, concentration-dependent bactericidal activity against S. aureus, achieving a decrease of 3 log10 CFU mL−1 in 4 h at 100 µg·mL−1, according to these time-to-kill experiments. In contrast to the lipopolysaccharide barrier of Gram-negative bacteria, the peptidoglycan-rich cell wall of the former is known to facilitate polyphenolic penetration, which is consistent with the increased activity against the Gram-positive strain[33]. These kinetics support HBg's potential as a topical antibacterial or natural preservative in situations where Gram-positive contamination is an issue by demonstrating that it can actively decrease S. aureus populations rather than just preventing growth. These results were further supported by time-to-kill studies, which showed that the bigel greatly decreased the growth of S. aureus in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 7a), although only a slight decrease in values was shown for E. coli (Fig. 7b). These outcomes demonstrate the bigel's potential for usage in antimicrobial formulations, namely for the purpose of focusing on Gram-positive microorganisms in applications connected to food and medicine[34].

Figure 7.

(a) Time-to-kill assay for S. aureus in the test sample of HBg. (b) Time-to-kill assay for E. coli in the test sample of HBg.

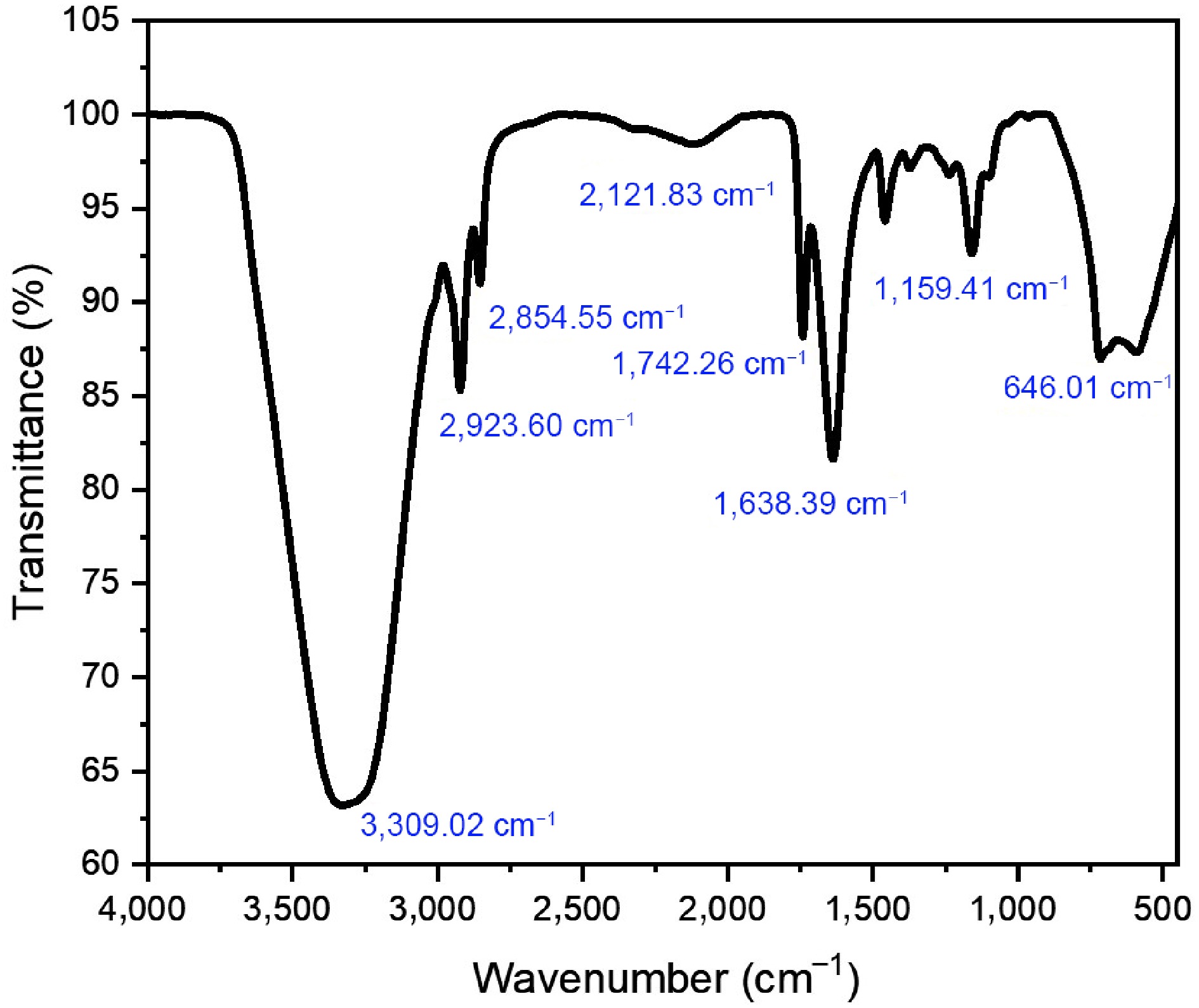

FTIR

-

FTIR spectroscopy was used to examine the functional groups in the bigel formulation. A number of unique peaks in the FTIR spectrum (Fig 8.) were indicative of the phytochemical ingredients and the carrier oil. A broad and strong absorption band at 3,309.02 cm−1 indicated the presence of antioxidant-rich plant extracts because it matches the O–H stretching vibration, which is typical of the hydroxyl groups found in phenolic and flavonoid compounds. The asymmetric and symmetric C–H stretching vibrations of the methylene (–CH2–) groups were responsible for the peaks at 2,923.60 and 2,854.55 cm−1, which confirmed the presence of aliphatic hydrocarbon chains in RBO.

The C=O stretching vibrations that created the strong band at 1,742.26 cm−1 were probably caused by ester or carboxylic acid groups that were present in both the base oil and the plant components. A noticeable peak at 1,638.39 cm−1, which is associated with aromatic rings spanning C=C, also supports the existence of polyphenolic compounds. The C–O stretching vibrations of ethers or esters were also linked to the band at 1,159.41 cm−1, whereas the out-of-plane bending of aromatic C–H bonds may be connected to the peak at 646.01 cm−1. Compared with individual components, the presence of these functional groups and the observed alterations in band locations indicates that the bioactive chemicals were successfully incorporated into the bigel system.

Fat replacements

-

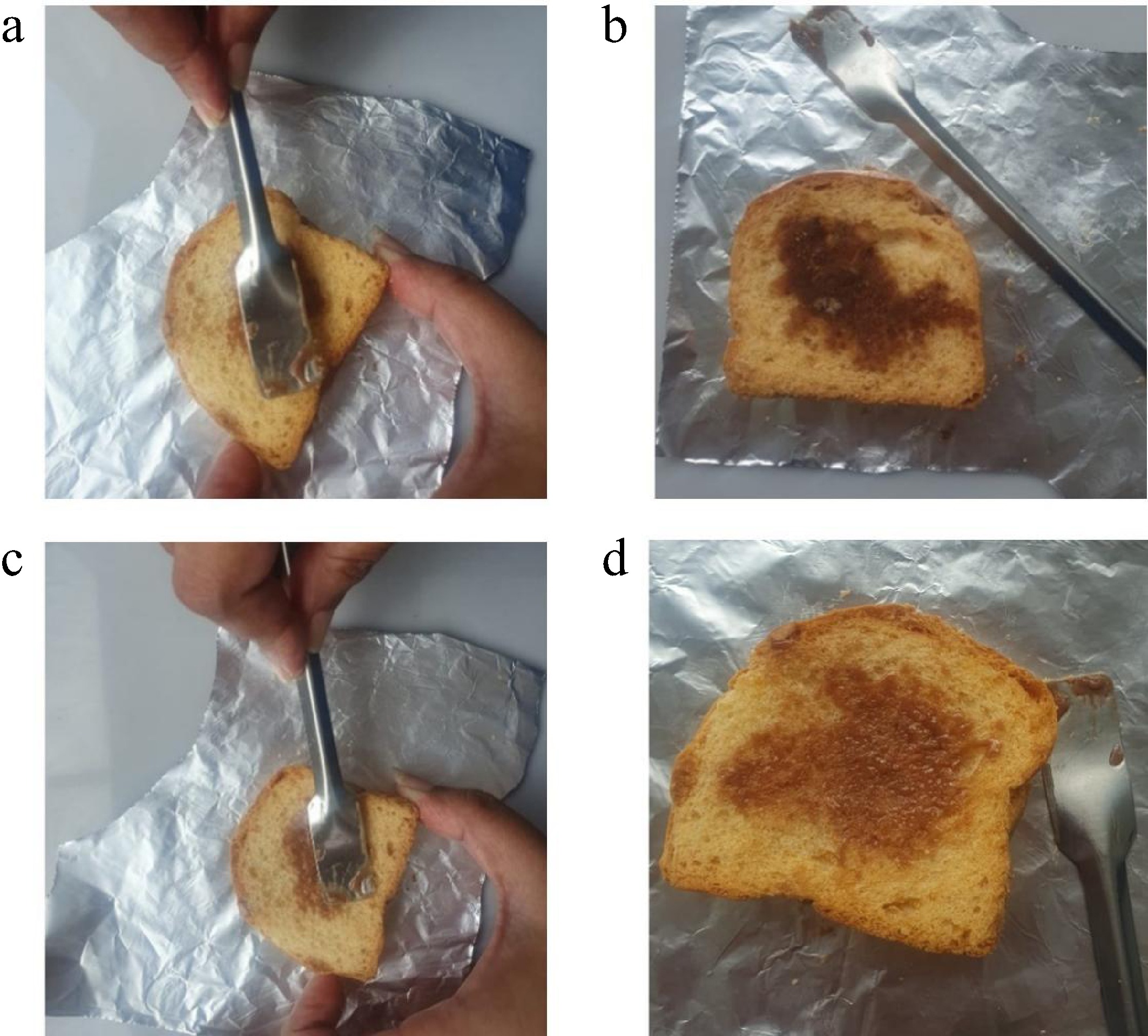

According to the visual observations in Fig. 9, the spreadability and aesthetic appeal of HBg and JBg were evaluated on the surface of a toast slice. The first image clearly illustrates the limitations of the JBg, where the bigel shows poor spreadability, resulting in visible friction marks and uneven dispersion. The accumulation of JBg on the surface produces a coarse, grainy texture that compromises both its visual and sensory acceptability. In contrast, the second image showcasing HBg reveals a smoother, more uniform application with minimal resistance. The bigel spreads gently across the toast's surface, achieving a visually appealing, glossy finish that mimics commercial butter spreads. This superior spreadability of HBg can be attributed to its optimized lipid network and globule-like microstructure, which promotes cohesive flow and adhesion. Notably, no oil exudation was observed in our bigels, unlike the partial oil separation reported in a recent study by Sun et al.[35], where fish oil-based bigels used in low-fat mayonnaise showed slight exudation despite offering excellent antioxidant properties. Thus, from a functional and consumer acceptance standpoint, HBg outperforms JBg, making it a promising butter substitute for health-conscious and plant-based food applications.

Figure 9.

(a) Application of JBg to a toast slice. ( b) The look of the toast after spreading JBg. (c) Application of HBg to a toast slice. (d) The look of the toast after spreading HBg.

Stability test

-

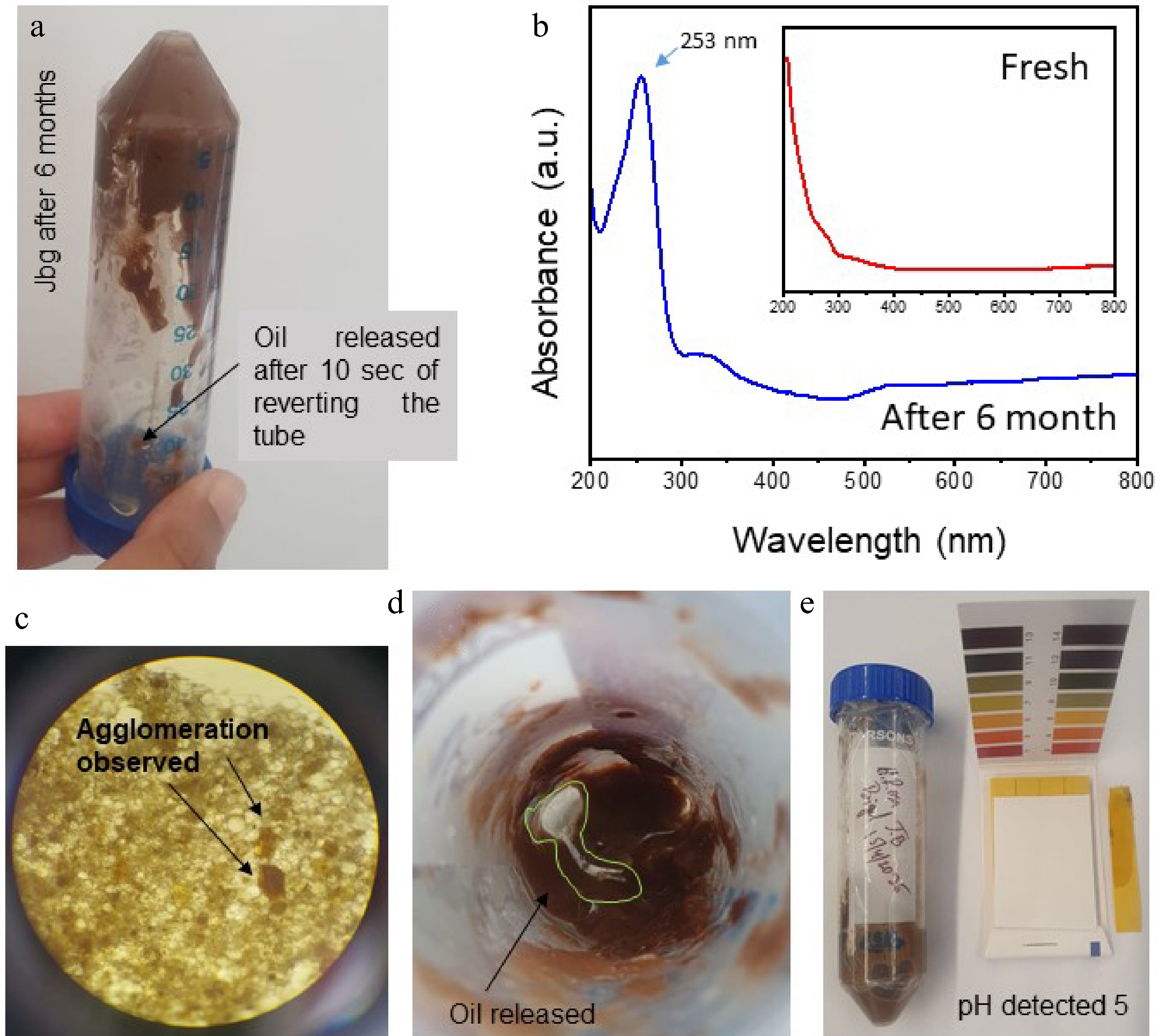

The visual inspection (Fig. 10a) showed that the 6-month-old Jbg released oil within 10 s upon inversion, indicating phase separation caused by reduced structural integrity. The stability of JBg stored at 4 °C was examined using UV–visible spectroscopy and visual, microstructural, and pH analyses. The UV–visible spectra (Fig. 10b) revealed a distinct absorbance band near 250–253 nm in the freshly prepared JBg, corresponding to the presence of conjugated dienes of fatty acids. This observation is consistent with the findings of Sidorov et al.[36], who reported that conjugated diene isomers derived from algae fatty acids exhibit absorption in the 218–253 nm region. However, in the sample stored for 6 months, a noticeable shift and increased absorbance at 250–253 nm were observed, indicating the formation of secondary oxidation products and confirming partial oxidative degradation during storage. Microstructural analysis (Fig. 10c) further confirmed the presence of flocculation and agglomeration, which are indicative of instability and particle coalescence after prolonged storage. Correspondingly, visible oil release was evident on the gel's surface (Fig. 10d), reinforcing the occurrence of emulsion breakdown. The pH evaluation (Fig. 10e) revealed a value of approximately 5, suggesting mild acidification of the system over time, likely caused by oxidative reactions and the degradation of lipid components.

Figure 10.

(a). The 6-month-old JBg, when inverted, released oil after 10 s. (b) UV–visible spectra showed an absorption peak at 260 nm for conjugated dienes as secondary oxidation products are observed in the sample stored for 6 months, whereas no distinct oxidation was observed in the fresh sample. (c) The microstructural observation reported flocculence or agglomeration caused by lengthy storage. (d). Visual oil release is observed on the surface of the JBg. (e) The pH was observed to be 5 as per the color chart.

Overall, these results collectively indicate that although the freshly prepared JBg exhibited good structural stability and oxidative resistance, prolonged storage at 4 °C led to noticeable physicochemical changes, including diene oxidation, agglomeration, oil release, and pH reduction, signifying reduced gel stability.

-

This study demonstrates that HBgs prepared with RBO, soluble starch, and aloe vera achieves a combination of desirable physicochemical and bioactive properties that position them as credible fat-replacement systems. The Results section details individual measurements, although their broader significance emerges when examined collectively and in relation to current bigel research.

The fine globular microstructure of HBg directly supports its superior OBC (79%) and spreadability compared with JBg. This interfacial synergy between the hydrogel (aloe vera) and oleogel (RBO) phases indicates efficient network formation and reduced syneresis, a recurring challenge in edible bigels. Importantly, the absence of oil exudation even at high RBO levels suggests that the polyphenolic constituents of hibiscus petals may contribute to enhanced interfacial stabilization, an effect seldom quantified in prior food-grade bigel studies. These findings expand the scope of natural bioactives as not merely fortificants but also as structural co-stabilizers.

HBg displayed strong radical scavenging activity up to 78.8% DPPH inhibition, surpassing reports on pumpkin seed oil bigels and approaching the values observed for dihydroquercetin-enriched oleogels. This potency can be attributed to the synergistic presence of hibiscus anthocyanins and RBO's γ-oryzanol, both of which are known to mitigate lipid oxidation and provide cardiometabolic benefits. The modest but consistent antimicrobial action, particularly against S. aureus, adds a food safety dimension that complements the antioxidant profile. Few edible bigels have been evaluated simultaneously for both antioxidant and antibacterial efficacy, marking a key novelty of this work.

Whereas most reported food bigels rely on synthetic or refined hydrogelators (e.g., carbopol, carrageenan) and wax-based oleogels, our formulation integrates agro-waste-derived hibiscus petals and jamun seeds with a health-promoting oil. This upcycling approach addresses the sustainability concerns raised in recent reviews. Moreover, the butter-like spreadability achieved without wax additives represents a practical advancement for consumer products that aim to reduce saturated fat while maintaining texture.

The higher swelling ratio of HBg (185%) implies a more open hydrogel network, likely driven by polyphenol–polysaccharide interactions that increase its water affinity. This structural hydration not only improves mouthfeel but may facilitate the controlled release of bioactives, a hypothesis that is supported by the strong FTIR signals for hydroxyl and phenolic groups. These mechanistic insights suggest that the hibiscus components act as multifunctional agents (texturizers, antioxidants, and emulsifiers) within the bigel matrix.

Several limitations warrant attention. First, this work is confined to laboratory-scale preparation and short-term testing; the bigels' shelf life under commercial storage conditions remains unknown. Second, sensory evaluation was limited to visual inspection; structured consumer panels and rheological assessments are necessary to validate market acceptance. Third, although in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial assays are informative, the in vivo bioavailability and the metabolic fate of encapsulated compounds require verification. Our research aims to incorporate accelerated oxidation studies, gastrointestinal digestion models, and pilot-scale production trials to confirm scalability and regulatory compliance.

Collectively, these findings position hibiscus-based bigels as a versatile platform for plant-based butter substitutes, functional spreads, and nutraceutical carriers. By valorizing agro-waste streams and integrating naturally antioxidant oils, this work contributes to the goals of a sustainable food system while meeting consumer demand for clean-label, health-oriented fats. The coordination demonstrated between structural performance and bioactivity highlights the potential for next-generation bigels that simultaneously address sustainability, health, and sensory quality.

-

This study successfully used the RSM to optimize the formulation parameters influencing the OBC of plant-based bigels derived from hibiscus flower petals and jamun seeds. Comparative analysis revealed that HBgs demonstrated superior functional performance, attributed to their compact, globular microstructure observed under optical microscopy. The results underscore the potential of bigels formulated from agro-waste as sustainable lipid-structuring agents, with significant implications for food, nutraceutical, and pharmaceutical applications.

The bioactive richness of hibiscus, including anthocyanins and flavonoids, contributes to its antioxidant, hepatoprotective, antihypertensive, and hypolipidemic properties, enhancing the health-promoting potential of the bigel. Coupled with RBO, a lipid source enriched with γ-oryzanol and known for its oxidative stability, these formulations present a promising alternative to conventional saturated fats.

The incorporation of semisolid bigels enriched with bioactive constituents not only improves the structural and oil retention properties but also provides added physiological benefits. Future work should focus on advanced characterization of the microstructure, molecular composition, and long-term functional stability, paving the way for next-generation bigels as effective and health-conscious fat substitutes.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: concept: Manikandan D, Bhattacharya T; data curation, data validation, formal analysis, original draft writing, and review and editing : Devilakshmi M, Das T, Bhattacharya T; visualization: Das T, Bhattacharya T; supervision: Bhattacharya T. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The dataset generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 RSM surface plot of the oil Binding capacity experiment.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Manikandan D, Das T, Bhattacharya T. 2026. Development and characterization of plant-based bigels for fat replacement using Hibiscus rosa-sinensis petals and Syzygium cumini (jamun) seed waste. Food Materials Research 6: e002 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0026-0002

Development and characterization of plant-based bigels for fat replacement using Hibiscus rosa-sinensis petals and Syzygium cumini (jamun) seed waste

- Received: 08 August 2025

- Revised: 17 November 2025

- Accepted: 19 January 2026

- Published online: 04 February 2026

Abstract: Bigels are biphasic formulations composed of two distinct structured phases with differing polarities, namely an oleogel phase and a hydrogel phase. Recently, increased demands for saturated fat substitutes and consumers' health consciousness have drawn attention to new bioactive rich bigels. This study aimed to develop and characterize anthocyanin-enriched plant-based bigels from Hibiscus rosa-sinensis petals and Syzygium cumini (jamun) seed waste as sustainable substitutes for saturated fats. Bigels were prepared by integrating aqueous jamun seed waste and hibiscus petal extracts separately into a rice bran oil–aloe vera bigel matrix by homogenization at 600 rpm to prepare synthetic emulsifier-free bigels, which were evaluated for their physicochemical and biofunctional properties. Microscopic analysis revealed that hibiscus bigels exhibited smooth, round, well-defined globules, achieving a spreadability of 373.3 g·cm·s−1 and a swelling ratio of 185%, whereas jamun seed bigels showed coarse, irregular spheroids with a spreadability of 320 g·cm·s−1 and a 130% swelling ratio. Antioxidant activity, determined by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assays, was significantly higher in hibiscus bigels (84.6% ± 2.1% and 78.8% ± 1.9% radical-scavenging, respectively) than in jamun seed bigels (62.3% ± 1.7% and 55.4% ± 2.0%). Antimicrobial testing using the agar diffusion method demonstrated broader inhibition zones for hibiscus bigels against Escherichia coli (9 mm) and Staphylococcus aureus (13 mm) compared with jamun seed bigels (10 ± 0.4 mm and 12 ± 0.5 mm). These findings indicate that hibiscus-based bigels offer superior structural integrity, antioxidant capacity, and antimicrobial efficacy, highlighting their promise as health-promoting, plant-derived fat replacements for functional food and nutraceutical applications.

-

Key words:

- Syzygium cumini /

- Hibiscus rosa-sinensis /

- Bigels /

- Antioxidant /

- Antimicrobial /

- Fat replacer