-

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is an attractive waste treatment method that can achieve waste management while recovering energy. It has other significant benefits, such as less sludge generation and the use of waste organic matter, and it helps offset the use of fossil fuels[1]. Nitrogen-rich wastes are suitable as AD substrates; however, they are frequently prone to low methane output, process instability, and occasionally total collapse, especially because of ammonia toxicity[2]. Ammonia nitrogen can surpass a threshold during the degradation of organic matter and become toxic to AD microbes, even though it supports their development at specific lower amounts. In particular, the microorganisms have no detrimental effects at 200–1,000 mg/L, but they are impacted at 1,500–3,000 mg/L ammonia concentrations, particularly in high pH anaerobic settings[3]. Furthermore, under all pH conditions, AD microbes are inhibited at varied levels when ammonia nitrogen levels surpass 3,000 mg/L. Methanogens are particularly sensitive to free ammonia nitrogen (FAN) due to the absence of peptidoglycan in their cell walls, which allows diffusion of FAN through the plasma membrane. Inside the cell, FAN disrupts the ionic balance, causes excessive uptake of K+, and affects the uptake and synthesis of osmoprotectants, and all of these occur at the expenditure of ATP. Metabolically incapacitated methanogens are unable to catabolize VFAs and hydrogen, leading to system inhibition via lowering of pH and an increase in hydrogen partial pressure[4]. Hence, it can be surmised that the primary reason for the collapse of AD due to ammonia accumulation is essentially the result of ammonia toxicity to methanogens.

The widely applied chemical and/or physical techniques to reduce ammonia inhibition involve regulating the ammonia concentrations through substrate dilution, carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio adjustment, pH modulation, and membrane distillation (for ammonia recovery). However, these techniques are difficult to implement, energy-intensive, and costly. Other techniques, such as bioaugmentation and acclimation, the addition of different supportive materials such as biochar, activated carbon, and magnetite, as well as the provision of trace elements and nanobubble water, have been tried to enhance biological processes[5]. Commercial AD systems are increasingly being monitored using automated monitoring and control techniques. Real-time monitoring of parameters such as ammonia levels, pH, volatile fatty acids (VFA) concentration, and methane output allows for quick modifications before significant inhibition takes place. By thoroughly examining the primary inhibitory indicators and facilitating prompt automated responses when the system exhibits indications of instability, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML) can improve bioreactor monitoring[6]. This review describes current advancements in ammonia inhibition mitigation techniques in light of these breakthroughs.

In recent years there have been review articles that have compiled several aspects of ammonia inhibition in AD. Adams[2] provided a review of syntrophic interactions and methanogenesis occurring during ammonia-stressed AD. Li et al.[7] summarised the effects of weak electrical stimulation for mitigating ammonia inhibition, focusing on the mechanisms. While Yang et al.[3] emphasized the effect of ammonia inhibition on the microbiological aspects of AD. However, these articles lack a comprehensive review of the latest developments in technology, underscoring the necessity of conducting a thorough assessment of the existing methods for ensuring the stability of the AD process while mitigating ammonia inhibition. Thus, the latest research on the effects of ammonia inhibition on the AD process is critically examined in this review, covering topics that have not been previously discussed, with particular attention to: (1) parameters influencing ammonia equilibrium in a reactor; (2) consequences of ammonia toxicity on methanogens and reactor output; (3) current mitigation strategies, including modulation of operational parameters, use of additives, bioaugmentation, novel reactor configurations, and use of ML and AI. The review concludes with a thorough discussion of the current challenges and future research directives. This article aims to serve as a compendium of the latest research and progress for mitigating one of the frequent challenges encountered during AD, namely, ammonia inhibition.

-

Within a reactor, ammonia can exist in two forms: one as aqueous (NH4+), and the other as gaseous, called free ammonia nitrogen (FAN). The amount of FAN at any given time, in proportion to TAN, depends on the pH and temperature of the reactor, Eq. (1)[8].

$ {\rm{FAN}} = {\rm{TAN}} \times \left(1+\dfrac{{10}^{-pH}}{{10}^{-\left(0.09018+\frac{2729.92}{T\left(K\right)}\right)}}\right) ^{-1} $ (1) where, pH is pH of the reactor; T (K) is temperature (Kelvin); concentrations of FAN and TAN are in mg/L.

As the temperature increases, the amount of FAN also increases. For instance, at a constant pH of 8 in a reactor, at 20 °C, FAN is only 4% of TAN. However, FAN increases to 13% at 40 °C[9]. This is critical as FAN has been identified as an inhibitor during AD[3]. As evident from Eq. (1), the accumulation of FAN exacerbates during thermophilic AD. In a study by Li et al.[10], when mesophilic AD (MAD) was compared to thermophilic AD (TAD), the amount of FAN in the thermophilic reactor was much higher than that in the mesophilic reactor. The biogas yield was much lower in TAD (84.81 ± 6.89 mL/g VTS) than in MAD (168.66 ± 38.05 mL/g VTS). At detected ammonia concentrations of 5.0 and 6.0 g/L in MAD and TAD, respectively, the biogas yield dropped further by 21% and 28% in MAD and TAD, respectively. However, bioaugmentation with acetate-oxidizing consortia and propionate-oxidizing consortia showed that TAD recovered from the ammonia inhibition faster than the MAD, even at high OLR. The authors attributed this to the increased abundance of Keratinibaculum and Tepidimicrobium, (proteolytic bacteria), Syntrophomonas (syntrophic VFAs-oxidizing bacteria), and Methanosarcina (hydrogenotrophic methanogen). Regarding the effect of pH, Salangsang et al.[11] reported that in a pH-controlled reactor maintained at 7.37 ± 0.03 with the addition of 0.5 N HCl, the FAN was maintained at 39.34 ± 3.92 mg-N/L, whereas in the reactor without pH maintenance, the pH rose to 7.98 (optimum range, 6.8–7.4), and the FAN exceeded the threshold of 100 mg-N/L within just 2 d of operation. The methane yield was higher in the pH-controlled reactor than in the non-pH-controlled reactor. The authors attributed this to a 1.7-fold increase in cell density in the reactor with pH control that enabled optimal degradation of organic matter. Here, it is crucial to note that the reactor operational parameters, pH, and temperature, also have a bearing on the physiology and metabolism of AD microbes[12,13], notwithstanding the levels of FAN. Maintenance of a specific or at least a narrow range of pH plays a critical role in AD. Each of the four stages of AD-hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis- needs a particular pH range to proceed smoothly. The pH range of 5.5–6.5 is optimal for hydrolysis and acidogenesis stages, while for acetogenesis and methanogenesis, the suitable range is 7.0–7.5[12]. Temperature influences the community structure within the reactor, such that an increase in temperature increases total VFA production, with an enhancement in the concentrations of propionic acid at the expense of acetic acid[14]. Hence, while regulating ammonia concentration is critical, pH, and temperature of the system also need careful monitoring and management.

-

The chemical relationship between ammonia and cells must be examined to comprehend the potential mechanisms of ammonia inhibition.

The energy balance in terms of ATP for most microbes is accomplished through the application of proton motive force (ΔμH+) across the cell membrane by proton-translocating ATPases. The energy in the trans-membrane pH gradient (ΔpH), and the trans-membrane electrical gradient (Δψ) contribute to the energy in the ΔμH+. Studies have shown that the transmembrane pH gradient (ΔpH) for methanogens in slightly alkaline environments is minimal or even negative; as a result, these microbes can thrive, even when the external pH is > 7, with a near-neutral cytosol[9].

Although the exact methanogen physiological pathway underlying ammonia toxicity is yet unknown, Kayhanian[15], provided a possible concept (Fig. 1). The model effectively explained the entry of NH3 into the cell and its subsequent internal buildup, based on transmembrane electrical and pH gradient theory. The model predicts that free ammonia molecules will easily permeate methanogen cells through their membranes, bringing the intracellular and external NH3 concentrations into equilibrium. However, ammonium (NH4+) is not able to permeate cell membranes with ease. Consequently, when a methanogen cell is exposed to a higher concentration of extracellular ammonia, the cytosolic concentration of un-ionized ammonia rapidly increases. In such a situation, the local pH, temperature, and NH3 concentration all affect the NH4+ concentrations, both extracellular and intracellular. Hence, cells with an internal NH4+ concentration higher than that of their surroundings would have an intracellular pH lower than the extracellular pH (negative ΔpH). In cells with an extremely negative ΔpH, cytosolic NH4+ may make up a significant portion of the intracellular cations. However, there is relatively little experimental evidence to support this theory because cation concentrations and intracellular pH are difficult to measure.

Two potential pathways of ammonia inhibition have been proposed once ammonia diffuses into cells. (1) Un-ionized ammonia's direct suppression of cytosolic enzyme activity. Kadam & Boone[16] investigated the activity levels of three ammonia-assimilating enzymes in three methanogen species belonging to the Methanosarcinaceae family: glutamate dehydrogenase, glutamine synthetase, and alanine dehydrogenase. The findings indicated that the three species had varying ammonia tolerances because they had distinct enzymatic outcomes in response to high ammonia accumulation in the growth environment. (2) Intracellular NH4+ accumulation. As free NH3 enters the cell, some of it is converted into ammonium (NH4+) by the lower intracellular pH. According to several earlier studies, the cell needs more energy for the K+ pump to maintain the intracellular pH via balancing of increased protons. Consequently, the higher energy demand may result in the suppression of other critical enzyme processes. Furthermore, when the cell is subjected to excessive ammonia and the K+ pumps are unable to function adequately, intracellular pH is disrupted, resulting in cytotoxicity[19]. It can be surmised that elevated ammonia may also impact the absorption of vital trace elements necessary for cellular metabolism, leading to a shortage of micronutrients[9]. Further, high pH accompanied by the accumulation of ammonia may have a combined harmful effect. A greater percentage of TAN is unprotonated at higher pH values (at 35 °C, around 0.5% at pH 7 but over 65% at pH 9, determined using Eq. [1]). The potential toxicity from NH4+ accumulation would also be larger if methanogens surviving at a higher pH maintain a more negative ΔpH for a near-neutral cytosol.

A strict syntrophic connection between VFA-degrading bacteria and methanogens in the AD environment is imposed by the universal requirement to follow thermodynamic laws. VFA oxidation is endergonic under normal circumstances, but the methanogens swiftly use the oxidation's byproducts, making the process exergonic. Under ammonia stress, suppressed methanogenic activity causes VFA and H2 to accumulate and upset the thermodynamic balance[20]. Furthermore, it has been reported that high ammonia exposure in syntrophic propionate- and butyrate-oxidizing bacteria results in the downregulation of important enzymes involved in the metabolism of propionate, including acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, pyruvate oxidoreductase, acetyl-CoA synthase, and succinyl-CoA synthetase, and in the metabolism of butyrate, including acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase, and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase[19]. The metabolic inefficiencies of syntrophic bacteria lead to VFAs accumulation, which impacts the methanogens. Incapacitated methanogens are unable to maintain a partial pressure of H2 that is lower than 10−4 atm, also causing H2 accumulation[4,21]. Hence, ammonia inhibition can induce thermodynamic imbalances resulting in the accumulation of VFAs and H2 in the reactors. Extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) contain electron-active compounds and redox functional groups that regulate essential enzyme activities; hence, they are necessary for stable AD[22]. In addition, EPS can recycle cell waste, exchange genetic material, absorb nutrients, and withstand environmental challenges, including fluctuating pH, temperature, and contaminants like heavy metals. By forming microbial aggregates, EPS secretion shields obligatory anaerobes from oxidative damage[23]. The structural integrity of EPS, particularly tightly bound-EPS (TB-EPS), has also been found to be impacted by high ammonia. Exposure to high levels of ammonia decreases the α-helix/β-sheet + random coil ratio, which is indicative of a looser protein structure[24]. This decreases intercellular adhesion and cell aggregate formation, which are crucial for optimal AD. Recently, Beraud-Martínez et al.[25] reported recovery from ammonia inhibition and a switch from acetoclastic to methylotrophic methanogenesis. A transition to methylotrophic metabolism was observed at 3.5 g TAN/L, as evidenced by a four-fold increase in Methanosarcina mazei abundance. TAN suppressed acetoclastic metabolism and methanogenic activity. Methanogenic capability could later be restored due to metabolic and taxonomic changes brought about by the gradual acclimation to TAN. The study emphasized the pertinence of applying suitable acclimation strategies to control anaerobic bioprocesses with high nitrogen loads in order to preserve the microbial community's methanogenic functioning.

Influence on reactor output

-

For designing practical strategies for increasing the methane yield during the AD process, it would be propitious to determine the exact effects of high ammonia accumulation. Table 1 lists the recent studies discussing the inhibitory effects of ammonia on reactor output. Methanogens are the most susceptible to ammonia toxicity among all other taxa within an AD reactor[19]. Among them, acetoclastic methanogens such as Methanosaeta have been shown to be less resistant to ammonia than hydrogenotrophic methanogens[26]. In addition to the microbial community, it has been reported that ammonia, either directly or indirectly, inhibits the action of some F420 enzymes, which have detrimental intracellular effects, including pH fluctuation and potassium imbalance[27]. Metabolomic analysis by Liu et al.[19], revealed that ammonia inhibited the catabolism of propionate and butyrate to acetate and methane by suppressing not only the acetoclastic methanogens but also the syntrophic fatty acids metabolizing taxa (Desulfovibrio). Ammonia accumulation had no impact on the overall relative abundance of the acidifying and hydrolyzing bacteria, but it increased the number of bacteria that were resistant to it. Ammonia inhibited the process of enzyme production by blocking the large ribosomal proteins (L3, L12, L13, L22, and L25), RNA polymerase (subunits A' and D), small ribosomal proteins (S3, S3Ae, and S7), and aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis (aspartate-tRNA synthetase) during translation. Ammonia also dramatically decreased the activity of several enzymes that control acetoclastic methanation, propionate and butyrate oxidation, including methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, acetyl-CoAC-acetyltransferase, and CH3-CoM reductase.

Table 1. Recent studies discussing the inhibitory effects of ammonia accumulation on reactor output

Ammonia-rich waste TS (%) VS (%) TCOD (g/L) TN (mg/L) TAN (mg/L) Inhibition effect Ref. Pig manure 2.67 ± 0.10 1.86 ± 0.08 21.3 197.48 197.48 ± 32.27 CH4 decreased 20% as ammonia concentration increased from 1,800 to 4,800 mg/L; complete methanogenic failure > 6,000 mg/L [28] Chicken manure 20.0 ± 0.5 17.0 ± 0.4 202 ± 1.1 1825 1,700 ± 10 Methane yield reduced by 18% (414−340 mL/g); inhibition TAN: 3.5−8.5 g NH4+-N/L [29] Cow manure 26.57 ± 0.84 19.27 ± 0.72 N/A N/A 1,510 ± 280 50% CH4 inhibition at 7 g/L TAN, failure at

> 8 g/L TAN[30] Primary sludge,

thickened waste

activated sludge8.2 5.3 85 4,100 1,400 CH4 yield reduced by 31% due to propionate

> 2.2 g/L; inhibition TAN 5.6−5.7 g N/L[31] Rice, rotten

vegetables, eggs57 51.34 27.64 405,120 3,700–4,946 CH4 yield reduced by 67% (from 321−106 mL/g)

and 99% (to 0.07 mL/g) at TAN 3.7–5.5 g/L[32] Chicken manure,

corn straw57.79 ± 0.82 32.64 ± 0.36 26.9 59,200 2,470–4,340 CH4 yield reduced by 71.14% (phase IV,

4,340.11 mg/L); inhibition TAN: 2,869.71–

4,340.11 mg/L, severe > 4,000 mg/L[27] Food Waste 5.2 90 46.8 39,000 2,360–3,200 CH4 yield reduced by 46.7% (0.08 L CH4/g COD added) at TAN 2.4 g/L and OLR 8 kg COD/(m3·d); inhibition TAN: 2.4–3.2 g/L [33] Chicken manure 29.2 ± 0.5 70.2 ± 3.0 65.38 3.8 3,775 ± 30 CH4 yield reduced by 50% at TAN 9,069 mg/L

and TVFA 33,646 mg-HAc/L[34] Chicken manure 92.46 ± 1.82 59.10 ± 0.39 1.29–24.85 2,293 ± 174 1,884 ± 154 CH4 yield reduced by 40% at TAN 1,884 mg/L [35] Chicken manure 35 68 N/A 27,000 8,500–9,000 CH4 yield reduced by 100% (control), 42% (hydrogenotrophic methanogen consortium to

184 mL/g VS), and 34% (syntrophic microbial consortium to 211 mL/g VS) at TAN > 4.2 g/L[36] Mesophilic sludge 13.22 ± 0.39 8.16 ± 0.24 1.06 g COD/(L·d) 1,430 900 CH4 yield reduced by 41% at TAN 2,500 mg/L [37] Chicken manure 29.3 ± 3.2 21.5 ± 2.1 139 14,360 2,493 → 6,162 CH4 yield reduced by 66% (from 445 to

153 mL/L·d) at TAN 2.5–6.3 g/L[38] Taihu blue algae 7.83 6.24 N/A 3,100 2,100–7,000 CH4 yield reduced by 71.2% (from 266.7 to

76.7 mL CH4) at TAN 7 g/L, and 40.8%

(to 157.9 mL CH4) at 5 g/L[39] Pig manure 31.51 ± 1.80 57.63 10.9 15,900 970–1,059 CH4 yield reduced by 21% (from 217.4 to

172.2 L CH4/kg VS) at TAN > 1,000 mg/L[40] Pig manure 24.59 19.19 N/A 1,574 700 CH4 yield reduced by 4.6% at TAN > 700 mg/L [41] In a recent study by da Silva et al.[42], raw swine manure was anaerobically digested in semi-continuous stirred tank reactors (CSTRs) at 37 °C, with a 12 L working volume. The authors reported FAN to be 300 mgN/L, leading to a 56% reduction in methane yield, emphasizing that the interaction of TAN, pH, and microbial adaptability affected FAN toxicity limits, which were context-dependent. During dry AD of chicken manure and corn straw in a gradient reactor for 138 d at 42 °C, He et al.[27] reported that when the amount of chicken manure was increased there was a significant decrease in methane yield to 41.85 ± 8.87 mL/(g·VS·d), a 69.63% decrease. In addition to the methane yield, the biogas CH4% also decreased, reaching 33.16 ± 2.81%. The amounts of CO2 and H2S also increased, reaching 58.47 ± 1.81% and 4,090 ± 218 ppm, respectively, indicating severe inhibition of methanogenic capacity. This could be the result of an improper feed ratio, which disrupted the physicochemical balance and impaired the microbial activity. In another recent study, Haroun et al.[33] reported semi-continuous flow anaerobic digestion of food waste and waste-activated sludge, with a low methane yield of 0.07 and 0.15 L CH4/g COD. The authors surmised a correlation between ammonia inhibition and methane generation and also acidification, as there was VFA accumulation (1.6 g/L) at ammonia concentrations of 3–3.2 g/L, and low COD removal efficiency (26%).

-

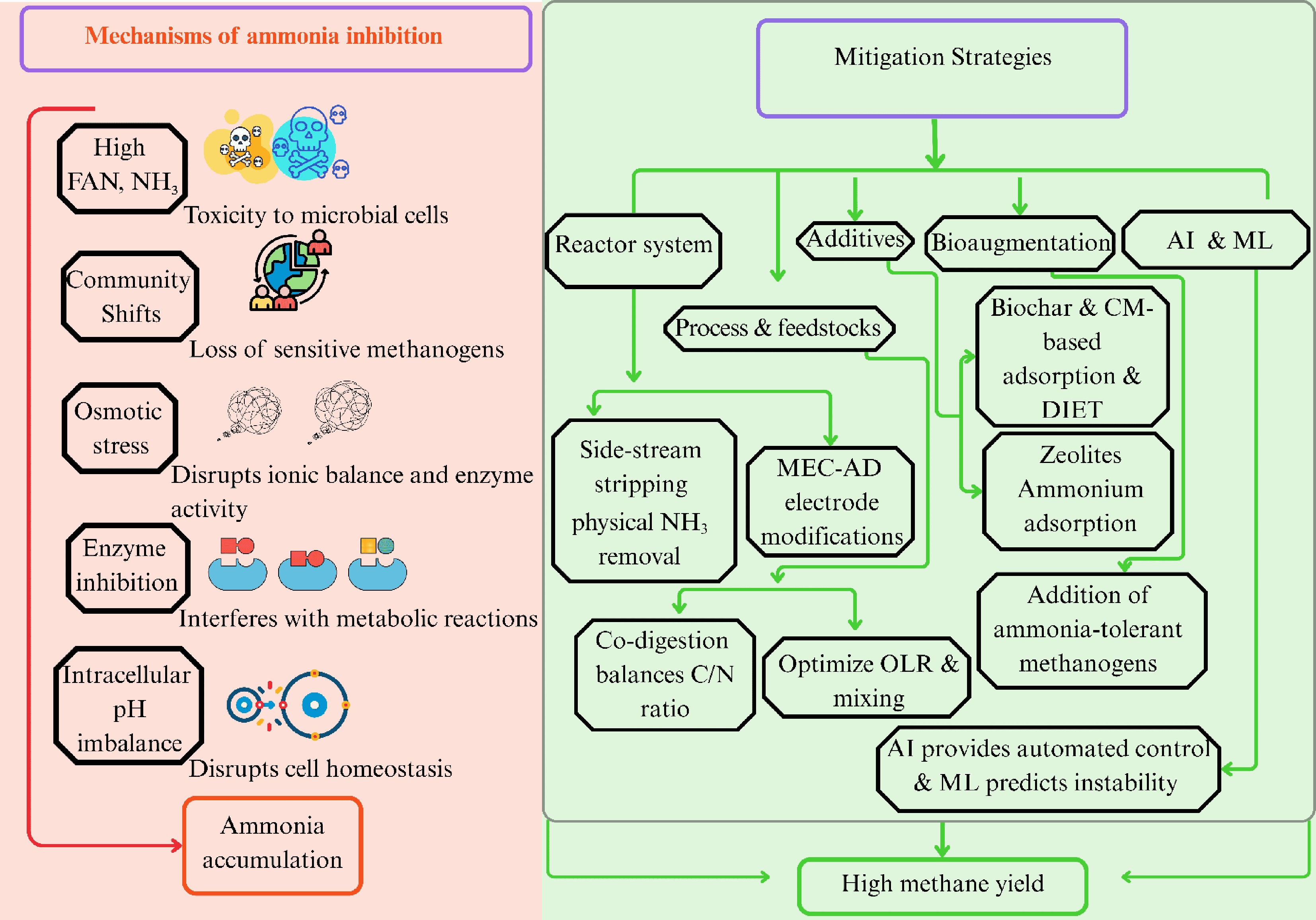

Numerous studies on mitigation techniques have been spurred by the persistent problem of ammonia toxicity in AD. Consequently, numerous biological, physical and chemical techniques have been employed to reduce ammonia inhibition, such as bioaugmentation, altering the pH and temperature, diluting the substrate, adjusting the carbon and nitrogen ratios, struvite precipitation, supplementing with micronutrients, adsorption, membrane distillation, acclimation, and use of conductive materials (Fig. 2). Most mitigation strategies can be broadly categorized into the following groups: (1) modulation of reactor configurations; (2) adjustments in operational parameters; and (3) use of additives.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the effect of ammonia inhibition on the microbes and mitigation strategies. FAN: free ammonia nitrogen; AI: artificial intelligence; ML: machine learning; CM: conductive material; DIET: direct interspecies electron transfer; MEC-AD: microbial electrolysis cell-anaerobic digestion; C/N: carbon to nitrogen; OLR: organic loading rate.

Modulating operational parameters

-

Modulation of operational parameters is usually the first approach at the onset of system instability. Malfunctioning can be promptly reduced, and more inhibition can be avoided by modifying parameters such as pH, temperature, OLR, mixing, and even micro-aeration. To prevent overfeeding, dosage modifications are typically used to reduce the OLR, and temperature control ensures it stays within the range. By enhancing the distribution of microbes and substrates, proper mixing helps avoid dead zones and associated inhibition. Further, such modulations can be applied using data from monitoring of early warning indicators of ammonia inhibition and associated AD instability, in real-time.

OLR optimization stands out among these operational parameters as being crucial for the functional stability of a reactor. The suitable OLR range is 2.0–5.0 kgVS/m3/d, and when exceeded, compounds such as VFAs, ammonia, etc., may accumulate, which are inhibitory at high concentrations, decreasing the methane output. The feedstock, digester (such as batch, plug flow, or continuous stirred tank reactor), and operation temperature (thermophilic or mesophilic) are some of the variables that affect the ideal OLR. Careful modification of operational parameters, such as appropriate mixing with the management of OLR, can alleviate microbial metabolism and aid in biogas production recovery in the event of ammonia-induced system instability[43]. Since hydraulic retention time (HRT) establishes the amount of time provided to microbes for the breakdown of organic matter, HRT and OLR are closely related. Methanogens need enough retention time to flourish because of their slow multiplication rate. Hence, during high ammonia accumulation, further suppression of methanogens may result in acidification if HRT is too short. VFA accumulation will increase critically if the OLR rises too quickly, as methanogens are unable to metabolize it. Further, increases in CO2 production cause a reduction in pH with a simultaneous reduction in the CH4/CO2 ratio[44]. Reducing the OLR can aid in the system's return to stable functioning in situations where the input of high-ammonia substrates (such as manure) causes AD instability and the abrupt increase in OLR causes inhibition. Reducing OLR, however, can be a short-term solution to stabilize reactor function and avoid microbial incapacitation if the ammonia toxicity is brought on by additional factors such as toxins or disruption in the carbon nitrogen ratios, even if this may lower system capacity and profitability. Therefore, to determine the root causes of instability, a thorough investigation is required. To maximize microbial activity, restore stability, and increase the efficiency of biogas generation, appropriate interventions are needed, that may be a combination of chemical, biochemical, and biological methods.

Mechanical mixing is just as crucial to preserving system stability as OLR management. To keep the digester homogeneous and guarantee that the nutrients, microbes, and substrates are dispersed equally, adequate stirring is necessary.

The rate of biodegradation and methane production is increased when there is adequate stirring because it guarantees improved contact between microorganisms and substrates. It prevents 'dead zones' from forming where organic waste might not decompose efficiently. Ammonia and other inhibitory compounds may accumulate as a result of stratification if there is insufficient stirring, which may result in process imbalances. However, excessive mixing can cause shear stress, which might upset the microbial population, especially methanogens that are susceptible to changes in the environment[45]. This may result in process failure and lower the efficiency of methane production; additionally, it may disintegrate microbial flocs, releasing proteins and extracellular polymeric materials into the reactor, leading to foaming. Mixing has an effect on foaming that goes beyond just producing more bubbles. Bubble entrapment, bubble nucleation, the creation of heterogeneous zones, and their impact on other parameters affecting foaming are all intricately intertwined. Controlling foaming requires achieving the ideal mixing level; too much mixing can enhance bubble production and entrapment, while too little mixing can cause stratification and localized foaming[46]. It has been demonstrated that intermittent mixing, as opposed to continuous mixing, reduces foaming. By allowing gas bubbles to escape during non-mixing periods, intermittent mixing helps to avoid foam formation and gas accumulation[47]. By reducing the shear force on microorganisms, this method also enables more stable digestion.

Although changes to operating parameters offer temporary stopgaps, long-term stability frequently necessitates the use of strategic feedstock management techniques for system stability. One of the widely acknowledged strategies to supply vital macro- and micro-nutrients, manage the carbon and nitrogen contents of the feedstock, and increase the buffering potential of the reactor in co-digestion. It can improve the bioavailability of nutrients by combining various feedstocks that include a variety of organic matter. This, in turn, promotes increased microbial functionality and consequently, improved reactor stability. In particular, co-digestion makes it possible to combine materials high in carbon, for example, kitchen waste, with feedstocks high in nitrogen (such as sewage sludge and animal manure), resulting in the ideal C/N ratio for microbial growth[48]. Balanced microbial activity is ensured by an ideal balance of carbon and nitrogen (20:1 to 30:1), which avoids ammonia buildup from nitrogen-rich substrates. Co-digestion lowers the possibility of overloading or process inhibition, boosts biogas output, and stabilizes the AD process[26]. This technique is also essential for maintaining an adequate supply of macro- and micro-nutrients for microbial communities in addition to maintaining the C/N ratio. The absence of vital micronutrients in some substrates frequently results in AD instability. Even with the ideal C/N ratio, inadequate micronutrients can result in poor methanogen activity, incomplete digestion, and ammonia buildup, which can cause process imbalances. Furthermore, maintaining steady pH levels in AD systems depends on buffer capacity. Rapid pH fluctuations can be avoided by co-digesting with substrates such as manure and sewage sludge, which naturally possess buffering qualities because of their ammonia and alkalinity content. For methanogens, which prefer a pH range of 6.5 to 7.5, this stability is especially crucial[4]. On the other hand, nitrogen-rich waste results in quickly broken-down TAN and FAN, which can cause abrupt pH changes, upsetting the AD process[49]. Microbial communities are unable to adapt to these changes in the absence of adequate buffering or nutrients from substrates such as manure or sludge, which leads to subpar performance and lower methane yields.

Recently, Zhou et al.[50] reported the application of a two-stage stripping method for the removal of ammonia while also limiting carbonate scale development, preventing crusting and blockage in the anaerobic system. To eliminate ammonia and raise the pH, which would allow Ca2+ and Mg2+ to precipitate from the wastewater, air stripping was first carried out at 55 °C with a gas flow rate of 1.5 L/min. Following settling, 1.5 L/min of biogas was added at room temperature to lower the pH while preserving the stability of Ca2+ and Mg2+ and avoiding scaling in the subsequent step. The findings showed that 480 min of air stripping increased the anaerobic digestion effluent's pH from 8.15 to 9.83, and resulted in a 90.69% ammonia removal efficiency. In another study, He et al.[27] reported the use of side-stream vacuum for ammonia recovery at an OLR of 3.8–4.5 kgVS/m3/d. The higher relative abundance of Methanosaeta and its incapacity to withstand vacuum caused a performance drop during initial operation, leading to a poor methane productivity (0.06 L/g CODfeed) and a significant soluble chemical oxygen demand buildup (12 g/L). Stability was restored by the increase in the relative abundance of Methanosarcinaceae under vacuum, which resulted in 53% VSS degradation. Ammonia stress was reduced, along with 47% TKN recovery, using ex-situ vacuum stripping, keeping the concentration of ammonia < 1 gN/L. The formation of a gradient within the reactor has also been reported to alleviate ammonia inhibition, which, with efficient intermittent stirring, transfers substrate from the horizontal end to the discharge end, precisely matching the HRT and avoiding the 'short-circuiting' problem[31]. Furthermore, the advantageous material density and internal friction of the reactor promoted material mixing and water absorption of dry straw, resolving the issue of floatation of wilting straw in CSTRs while increasing the generation of biogas. To assess recovery following ammonia inhibition and associated processes, the AD experiment was carried out over a period of 138 d in five phases, containing different quantities of corn straw (20% to 60% TS). The findings showed that a 5:5 ratio of manure to straw produced the maximum methane productivity (145.04 mL/g VS). Hence, while conventional techniques such as managing substrate input, OLR, and HRT are still the preferred mode of action, it would be prudent to apply some of the latest ammonia recovery methods to AD reactors suffering from high ammonia inhibition.

Use of additives

-

Supplementary materials and compounds can offer further support for system stability when feedstock management and operational changes are inadequate. AD processes can be stabilized with the application of supplemental compounds like biochar, magnetite, etc. (Fig. 3). Biochar is one of the most effective choices because it promotes the creation of biofilms among methanogens, acetogens, and acidogens, which improves VFA breakdown and increases methane production[51]. In AD systems, conductive materials (CMs) have been used to hasten the transport of electrons between syntrophs and methanogens. Table 2 lists some recent studies that reported alleviation of ammonia inhibition following the addition of CMs. The effectiveness of various CMs in reducing ammonia inhibition is largely dependent on their unique surface functions and features. For instance, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) prevent ammonia toxicity by forming K+ transport channels through the cell membrane, while the biochar surface's negatively charged surface functional groups make it an electrostatic attraction counterpart to free ammonia, thereby mitigating ammonia inhibition[2]. This was further demonstrated in a comparative meta-analysis study that looked into how various CMs affected methanogenesis (CH4 yield and production rate) in response to ammonia stress. Although their effects were statistically insignificant (p > 0.01), biochar, ZVI, PAC, and GAC additions were found to increase methane productivities by 37% to 71%[52].

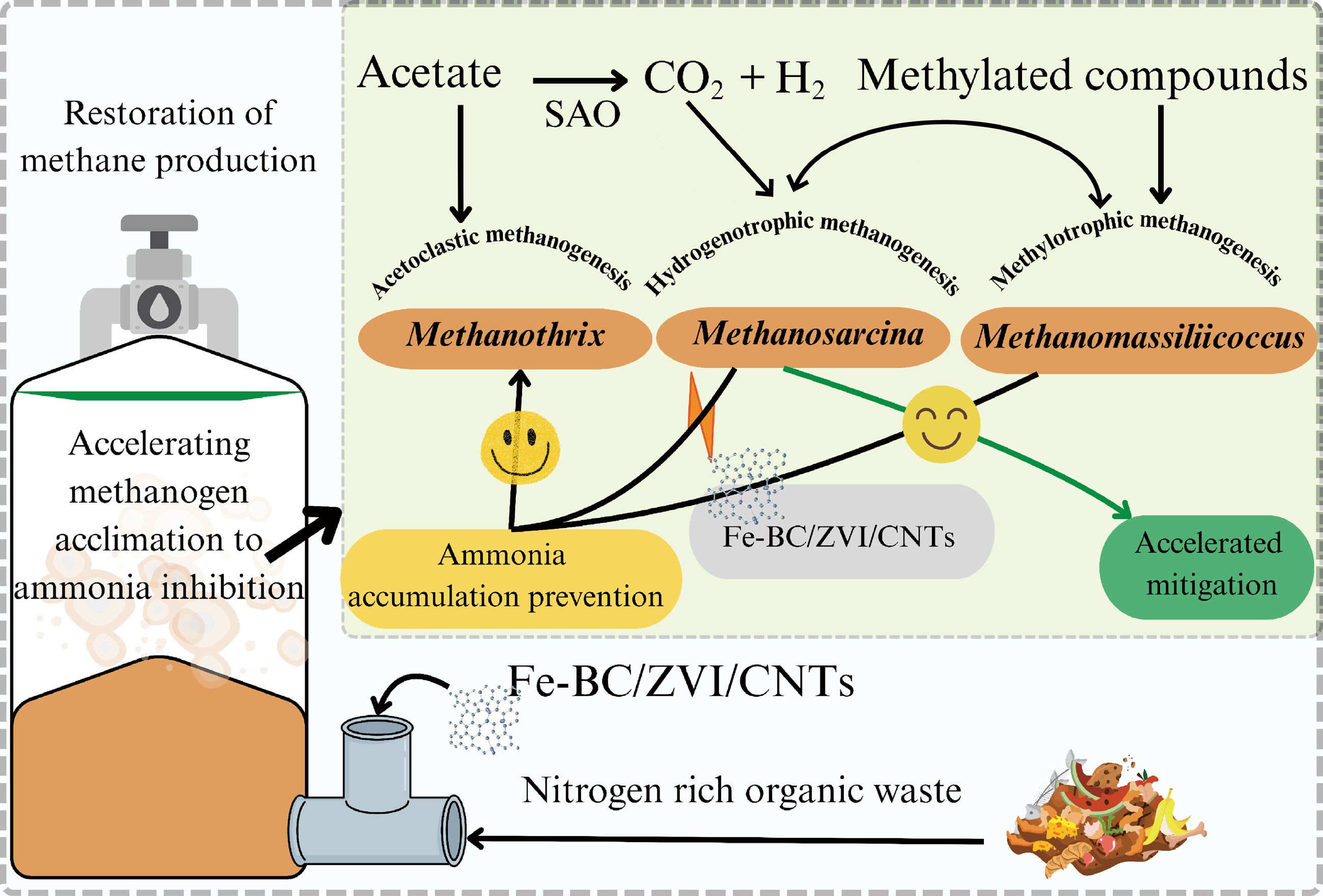

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the role of conductive materials in alleviating ammonia inhibition. Additives such as iron-biochar (Fe-BC), zero valent iron (ZVI), carbon nanotubes (CNTs) enable high methane yield while reducing the impact of ammonia accumulation. (The figure has been produced using input from references[53,54]).

Table 2. Recent studies reporting the role of conductive materials in alleviating ammonia inhibition

Reactor

typeTemperature

(°C)Ammonia

(mg/L)Conductive material CH4

enhancementEffect Ref. Batch 35 TAN 9.609 Corn straw biochar 121.3% BC800 improved conductivity (8.72 S/m), enhanced DIET, reduced VFAs, enriched Bathyarchaeia and Methanosaeta, and achieved a 35% reduction in TAN. [34] Batch 37 NH3–N 3,200

FAN 100Hematite, Goethite, Ferrihydrite Hematite: 22.8%

Goethite: 39.4%

Ferrihydrite: 56.3%Fe(III) oxides enhanced VFA conversion and methanogenesis, with Goethite and Ferrihydrite triggering Feammox (NH4+ → N2), reducing ammonia inhibition, and enriching reductive iron bacteria (FeRB and ammonia-tolerant methanogens, TAN ↓50%, FAN ↓40%. [56] Semi-continuous stirred reactor 35 TAN 1,200

FAN 100PAC, Magnetite, Graphite PAC: +39.1%

Magnetite: +42.5%Methanogenesis, enzyme activity (F420, AK, and protease),

DIET enhanced; microbial salt-tolerance improved (Na+/H+ antiporter, K+ uptake, osmoprotectant transport); microbial viability maintained (↑40%); TAN: ≤ 1,200 mg/L, FAN: ≤

100 mg/L (40% reduction).[57] Batch 37 FAN > 100 IP, BC BC: 18.9%

IP: 9.8%Biochar boosted acetate degradation; Methanobacterium enrichment; TAN controlled, FAN ≤ 100 mg/L. [58] Batch 37 NH3–N 1,500

TAN 4,000Biochar, GAC, Magnetite Biochar: 7.6%.

GAC: 17.6%.

Magnetite: 10.4%COD removal: > 90% (GAC); enhanced degradation of N-organics and inhibitors; enrichment of DIET microbes (Syntrophorhabdus, Syner-01, Mesotoga, Methanosaeta); Methane yield increase: +77% (magnetite), TAN: > 80% degradation (biochar), FAN: Controlled (GAC removal). [59] Batch 35–37 TAN 3,200

FAN > 100Ferrihydrite 84.8% Boosted COD removal to 88%–92% (vs 71% control), increased TN removal by 36.8%–52.5%, and shifted community toward Methanobacterium, Methanosarcina, and Methanosaeta. TAN: reduced from 3,200 to 2,086 mg/L, FAN: controlled below 100 mg/L. [56] Batch 26 22.5 ICB 83.70% Enriched ammonia-tolerant methanogens (Methanosarcina, Methanosaeta). TAN: reduced from 22.5 to 15.6 mg/L (30.7%). [60] Batch 37 NH4+-N 4,946 FeMn-MOF/G +201% Increased activity of coenzyme F420, NH4+-N reduced by 57.8% to 2,086 mg/L. Enriched Methanosarcina, enhanced acetoclastic methanogenesis pathway. [32] Batch 35 TAN 1,260 GO, MGO 284% GO/MGO facilitated DIET, enhanced microbial attachment, and boosted hydrolysis; TAN reduced from 1,260 to 1,050 mg/L. [61] Batch 35 TAN 4,527 Fe-Z 195% Promoted microbial activity, electron transfer, syntrophic oxidation, enrichment of electroactive communities like Anaerolineae and Methanosarcinaceae, and boosting metabolic pathways such as carbohydrate metabolism;

and TAN reduced to 1,177 mg/L.[62] Two-phase anaerobic digestion system 35 TAN 1,700 ZVI, activated carbon 143% ZVI improved hydrolysis and acidogenesis, while methanogenesis was enhanced through DIET; stabilized VFA/TA < 0.4, shifted dominant archaea from Methanoculleus to Methanosarcina. [63] Batch 35 TAN 5,000 Biochar (peanut shells pyrolyzed) 37% Lag phase halved (18 → 9 d), accelerated acetate use, enhanced DIET via pili and cytochrome C, enriched Sporanaerobacter, Blvii28, Methanobacterium and Methanosaeta, up-regulated NH4+ detox (glutamine synthetase); reduced TAN inhibition by 63% under 5.0 g/L ammonia stress. [64] Batch 35–45 NH4+–N 2,000 Fe–C Cumulative CH4

128.31% (MAD)

286.96% (STAD)Fe–C enhanced DIET, electron/proton transfer, and energy metabolism; enriched Chloroflexota, Methanosarcina, Methanoculleus; upregulated ATPase; ammonia < 2.0 g/L boosts methane, while > 2.0 g/L inhibits. [65] Semi-continuous anaerobic digestion 35 NH4+–N 600–3,300 RM 19.05% pH ↑3.97 → 6.27; enhanced hydrolysis and methanogenesis; promoted DIET, oxidative phosphorylation; enriched Candidatus Cloacimonetes, Bacteroidetes, Synergistetes, Methanosarcina, Methanothrix; up-regulated cytochrome c, e-pili (fixA, pilD, ccmE/F/G); enzymes (AK, phosphatases, CoA synthetase). [66] Batch 35 TAN: 1,500–2,082 Allophane 261%–350% Allophane mitigated ammonia inhibition through NH4+-N adsorption (capacity: 261.9 mg/g), enhanced DIET with increased Methanosaeta, Methanosarcina, and coenzyme F420 (up 103%–120%); TAN/FAN reduced below inhibitory thresholds (from 2,082 mg/L in control to < 1,500 mg/L). [67] Fe–C: Iron–carbon materials; PAC: Powdered activated carbon; IP: Iron powder; BC: Biochar; GO: Graphene oxide; MGO: Magnetite-decorated graphene oxide; Fe–Z: Fe-modified zeolite; ZVI: Zero valent iron; RM: Red mud; MAD: Mesophilic anaerobic digestion; STAD: Semi-thermophilic anaerobic digestion; FeMn-MOF/G: Metal–organic framework (MOF)-derived porous metal oxide/graphene nanocomposite. By inducing DIET-independent metabolism, particularly iron-based CMs, can function as an ion channel protein while also providing trace elements to withstand ammonia stress. For example, the response of microbes under ammonia stress was triggered by micronutrients (Co, Cu, Fe, and Ni) leached from biochar, and this resulted in a rise in CO2 reduction pathway enzymes[68]. The capacity of iron-based conductive materials to promote the growth of important syntrophs, such as Syntrophomonas, and particular hydrogenotrophic methanogens that are independent of DIET allows methanogenesis to continue even during ammonia stress[69]. The consequences of ammonia stress are mitigated by the addition of composite conductive materials, which stimulates methanogen proliferation, particularly Methanosarcina. For DIET, biochar promoted the association between Syntrophaccia schinkii and Methanothermobacter thermoautotrophicus, which increased the recovery of methanogenesis that ammonia accumulation had previously impeded[53,70]. Nevertheless, more research is still required to fully understand methanogenic enhancement via IET stimulation, especially in the presence of ammonia inhibition. In this context, technologies like metagenomics, metabolomics, metaproteomics, and metatranscriptomics might offer more molecular-level insights. Recently, Xiao et al.[34] reported the effects of biochar types on the dry AD of chicken manure under the combined stress of ammonia and VFAs. There was a 50% reduction in biogas generation at TAN 9,069 mg/L and total VFAs (TVFA) 33,646 mg-HAc/L. The supplementation of biochar prepared at 800 °C (BC800) enhanced biogas generation by 121.3% and decreased the lag phase by 38.6%. BC800's superior pore size and high surface area, and high electrical conductivity and specific capacitance value greatly enhanced its performance. Bathyarchaeia and Methanosaeta were enriched, promoting the utilization of VFAs while supporting acetoclastic methanogenesis. Haroun et al.[33] reported the impact of combining thermal pretreatment and supplementation of biochar in the mono- and co-digestion of kitchen waste with thermally pretreated thickened waste activated sludge (PTWAS). For 161 d, six semi-CSTRs were run with and without the addition of biochar at different OLRs of 2–8 kg COD/(m3·d). CH4 productivity increased to 0.15 L CH4/gCOD (87.5%) when biochar was introduced, and 30% FW + 70% PTWAS was co-digested. Importantly, this result was obtained when the reactors had 2.4 g/L ammonia and 8 kg COD/(m3·d) OLR. These findings suggest that a reduction in ammonia and VFA inhibition was possible by adding biochar to co-digestion of kitchen waste and TWAS, and also to enhance methane production. Different types of modified biochar are being successfully used to alleviate ammonia inhibition. Din Muhammad et al.[60] studied the effect of iron-containing biochar (I-CB) as a supplement for mitigating high-ammonia induced stress while improving biogas yield. The concentration of ammonia dropped from 22.5 mg/L (control) to 15.6 mg/L. I-CB reactor produced a biogas yield of 33.8 mL/g, an 83.7% improvement over the control reactor (18.4 mL/g). The involvement of iron in boosting microbial activity and electron transfer, as well as its porous structure, high surface area, and functional groups that promote ammonia adsorption, was linked to the improved performance of I-CB reactor during AD of food waste. Ye et al.[71] reported the efficiency of magnetic biochar in enhancing AD of swine wastewater under ammonia stress. The AD performance was optimized at ammonia nitrogen levels of 3,000 and 4,500 mg/L with a single addition of 15 g/L magnetic biochar. Compared to the control, magnetic biochar application demonstrated a 60% increase in maximal gas production rates, and a 16.2% increase in cumulative methane yield. According to the microbiological investigation, magnetic biochar optimized AD performance by increasing the abundance of acetogens and changing the dominant methanogens from sensitive Methanosaeta to the extremely ammonia-tolerant Methanosarcina. MnO2 modification is another strategy to enhance the effectiveness of biochar in alleviating ammonia inhibition. Li et al.[72] reported that MnO2-modified biochar, in the presence of 2 g/L ammonia nitrogen concentration, enhanced the cumulative methane yield by 12.74%, attributed to the redox potential of MnO2 in increasing the biochar capacitance, consequently enabling microbial electron transfer processes. In another recent study, a unique hybrid method for treating ammonia-inhibited AD was used that combined iron-modified zeolite (Fe-Z) with photonic treatment[53]. Fe-Z demonstrated a high ammonia adsorption (117.65 mg/g) and was distinguished by the presence of pores, abundant metal cations, and advantageous functional groups. Digesters with Fe-Z and ammonia concentration of 4,000 mg NH4+-N/L, showed a 48% enhancement in methane production (216 ± 19 mL/g DOCremoval). A methane production 1.3 times that of the control was achieved by further integrating optimal photonic stimulation (1.25 × 104 μmol/(L·d)). The authors attributed microbial metabolism and biosynthesis of critical enzymes to the kinetics of Fe transformation and methanogenesis. Furthermore, the hybrid system's selectivity for robust methanogens (Methanosarcinaceae and Methanosaetaceae), nitrate reducers (Epsilonproteobacteria and Betaproteobacteria), and syntrophic organic matter oxidizers (Anaerolineae and Clostridia) aided the efficient breakdown of VFAs, N reduction, and methane conversion. Furthermore, increased relative abundance of electroactive microbes (Methanosarcinaceae and Anaerolineae) supported an electron transport pathway that was energetically favourable for ATP generation intracellularly. Extracellular interspecies cooperation was also possible, which fuelled the metabolism pathways associated with methanogenesis. In order to increase the stability and methane production of chicken manure under ammonia inhibition, Liu et al.[67] reported application of synthetic allophane to AD. When compared to the control, the CH4 yield increased by 261%–350% when allophane at 0.5% to 1.5% was added. Allophane demonstrated an NH4+-N-adsorption capacity of 261.9 mg/g, and the activity of enzymes such as coenzyme F420 was also enhanced. The increase in Methanosaeta and Methanosarcina further supported the idea that the addition of allophane improved methanogenesis, possibly through DIET. Supplementation with additives such as osmoprotectants (MgCl2), trace elements and activated carbon rescued AD, which had TAN concentration > 8 g/L and a propionic acid concentration of 2.2 g/L[73]. The authors reported an enhancement in methane yield (28%) and a decrease in hydrogen partial pressure by up to 3-fold compared with the control. The findings indicate that, in spite of high propionic acid levels, osmoprotectants and the addition of activated carbon were associated with a decrease in the osmotic pressure in methanogens and an increase in direct interspecies transfer, respectively. AD of manure is frequently inhibited by high ammonia accumulation. To remedy this, Sun et al.[28] added ZVI at 10 g/L to the reactor and reported improved system resistance to high ammonia concentrations (4,800 mg/L) and a community shift in dominant methanogens. The cumulative methane yield increased significantly from 221.9 to 267.91 mL/gVSsubstrate and from 203.33 to 261.05 mL/gVSsubstrate after 56 d of supplementation with 10 g/L of ZVI at ammonia concentrations of 3,300 and 4,800 mg/L, respectively. Hence, adequate dosages of suitable additives have shown remarkable mitigation effects during high-ammonia induced system inhibition.

Bioaugmentation

-

Bioaugmentation has been reported to invigorate the stages of AD to alleviate ammonia inhibition. Reactor performance is improved through bioaugmentation, which introduces specialized microbes into the reactor to enhance a particular biochemical pathway. This technique has benefits, including quick and effective microbial community evolution and simplicity of use. Despite the various underlying mechanisms, bioaugmentation employing both pure and mixed cultures has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing ammonia stress during digestion. Following are some of the advantages offered by bioaugmentation in comparison to other techniques. (1) Economic viability and simplicity of use: In contrast to bioaugmentation, physical/chemical techniques like the C:N ratio and pH adjustment mandate substrate/pH regulators, while membrane distillation uses membrane modules, which are costly, complex, and energy-intensive to operate and maintain. (2) Quick microbial community response: Using microbe immobilization and/or acclimation as an alternative takes a long time for granulation or formation of biofilms, and for changes in species dominance and composition to take place. (3) Long-term stability: Following bioaugmentation, for instance, stable operation has been attained for more than 140 d. (4) Customization is simple: Case-specific strategies can be created by combining different strains and consortia with various ideal environmental conditions. Since hydrogenotrophic methanogens are known to be more resistant to high ammonia concentrations than other microorganisms involved, much more attention has been paid to enhancing hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis employing hydrogenotrophic methanogens as a bioaugmentation inoculum. Tian et al.[74] used the high-multiplying Methanoculleus bourgensis MS2T at extremely high ammonia concentrations (11 g NH4+-N L–1). When the inoculum was introduced, production of methane increased by 28%, and VFAs, particularly propionate, rapidly decreased. According to sequencing results, following bioaugmentation, the relative abundance of M. bourgensis increased by two times, and the acetoclastic methanogen, Methanosarcina soligelidi, predominated. The authors attributed the system's quick recovery of methane production to the fast decrease in hydrogen partial pressure, which improved the AD process overall by relieving the stress of the accumulated VFAs. The acetoclastic pathway's widespread use and the acetoclastic methanogen's strong affinity for acetate must enable research in bioaugmentation that aims to strengthen acetoclastic methanogenesis. Using an enhanced culture dominated by Methanosaetaceae (obligately acetoclastic), which comprised more than 90% of the archaeal groups, Li et al.[75] initiated the bioaugmentation. The non-bioaugmentation reactor (TAN 3 N/L) was inhibited under ammonia accumulation, but 45 d after dosing, an increased methane output of 70 mL/L/d, accompanied by a 51% enhancement in propionate degradation, were noted. Additionally, the failed reactor was able to recover effectively at 2× concentration of the bioaugmentation culture. Following bioaugmentation, microbial data revealed a notable rise in Methanosaetaceae, confirming the bioaugmentation culture's successful establishment. This study showed that even though acetoclastic methanogens are susceptible to ammonia, dosing the system with them can prevent and restore an ammonia-inhibited condition. Further research is necessary to determine whether the mitigating effect remains at greater ammonia levels, as a comparatively weak ammonia stress (3.0 g N/L) was chosen for this investigation. Furthermore, Yang et al.[76] evaluated a number of combinations of microorganisms known for varied functions within an AD reactor in order to identify the most effective method for reducing ammonia stress at TAN 4 g N/L. Thirteen methods were examined, and seven pure strains of microbes—including obligate and facultative acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogens, and syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria—were chosen. The results showed that bioaugmentation using the hydrogenotrophic methanogen Methanobrevibacter smithii and syntrophic acetate oxidizing bacteria Syntrophaceticus schinkii increased the methane productivity by 71.1%. Methane output was increased by 597.7% with bioaugmentation using facultative acetoclastic methanogen Methanosarcina barkeri alone.

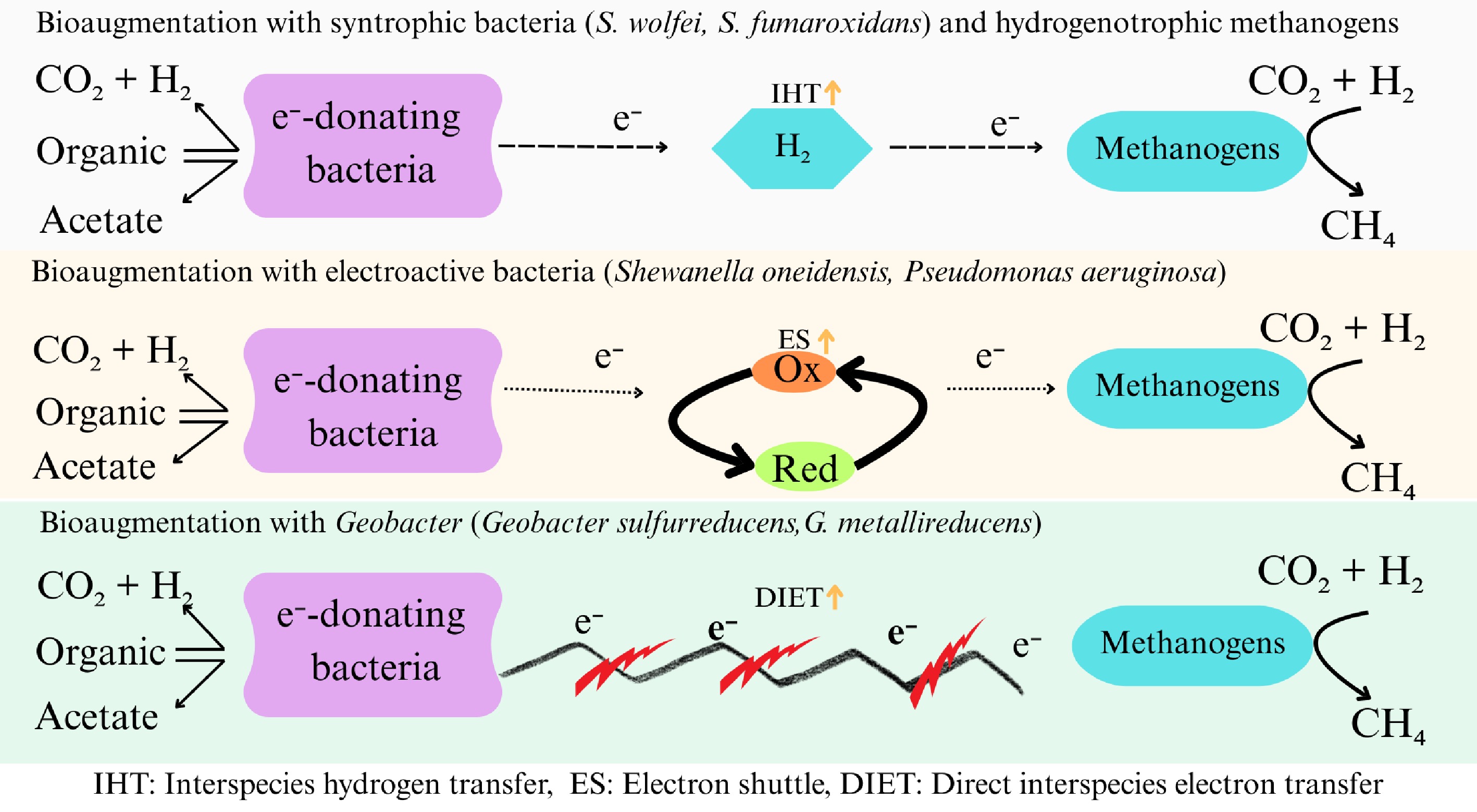

More recently, He et al.[27] determined the effectiveness of kitchen waste AD in two consecutive tests (R1, R2) with ammonia (3–9 g/L) and salt (5–15 g/L), to explore the processes of bioaugmentation involved in mitigating ammonia and salt stress. R1 and R2 were operated in succession, under the same operational parameters. To assess performance and microbial community evolution, domesticated sludge from the reactor with the highest exposure was combined with new inoculum (0%–50%) and reintroduced into R2 with exposure to 9 g/L ammonia and 15 g/L salt. The findings showed that as exposure levels in R1 increased, reactor performance decreased. However, R2 consistently performed better than R1 under the same exposure levels, suggesting that domestication of microbes improved reactor tolerance to both salt and ammonia within the measured concentrations. The methane yields of R2 were 10%–50% higher. Sequential exposure enhanced seven salt-tolerant and eight ammonia-tolerant taxa. However, only some of these resilient genera—4/7 in the groups exposed to salt and 3/8 in the groups exposed to ammonia—were able to effectively colonize the bioaugmented systems. In another study, the effectiveness of bioaugmentation using non-domesticated mixed microbial consortia was assessed, and under TAN 2.0 and 4.9 g-N/L, there was a notable improvement in methane production of 5.6%–11.7% and 10.3%–13.5%[77]. As the OLR rose from 0.5 g-VS/(L·d) to 1.0 g-VS/(L·d), methane production was noted following a quick recovery. During the steady state, the methane content varied between 58.0% and 62.9%, with an average methane production of 178 ± 11 NmL/g-VS. The pH steadily dropped from 8.06 to 7.75 throughout. By controlling the symbiotic interactions between methanogens and bacteria that oxidize propionate and acetate, the bioaugmented microbes enabled a shift in the methanogenesis, from acetoclastic to hydrogenotrophic at high ammonium levels (Fig. 4). This leads to the conclusion that the type of consortium and the dosage are important determinants of the efficacy of bioaugmentation, and non-domesticated mixed microbial consortia show promise as affordable bioaugmentation agents for reducing ammonia-induced inhibition.

Figure 4.

Role of bioaugmented bacteria in enhancing methanogenesis for alleviation of ammonia inhibition. Inoculation with suitable strains could enable electron transfer between the syntrophic partners resulting in enhanced methanogenesis while mitigating impacts of ammonia accumulation. (This figure was produced using input from references[78,79]).

Comprehensive large-scale studies are very rare, despite a wealth of research confirming the effectiveness of bioaugmentation in reducing ammonia inhibition. This may be because full-scale facilities often operate continuously with a huge working volume, which would require a substantial volume of bioaugmentation inoculum for experiments. As mixed cultures have comparatively lower cultivation requirements than pure strains, using them is advised to further lower the cost of obtaining bioaugmentation inoculum. Additionally, it is necessary to develop an efficient preservation method that permits the sophisticated preparation and low-cost long-distance transportation of bioaugmentation inoculum. Successful bioaugmentation may be achieved by applying membrane reactors that facilitate biomass retention and biofilm growth, as well as by adding supportive materials to reduce the washout effect.

Reactor configurations

-

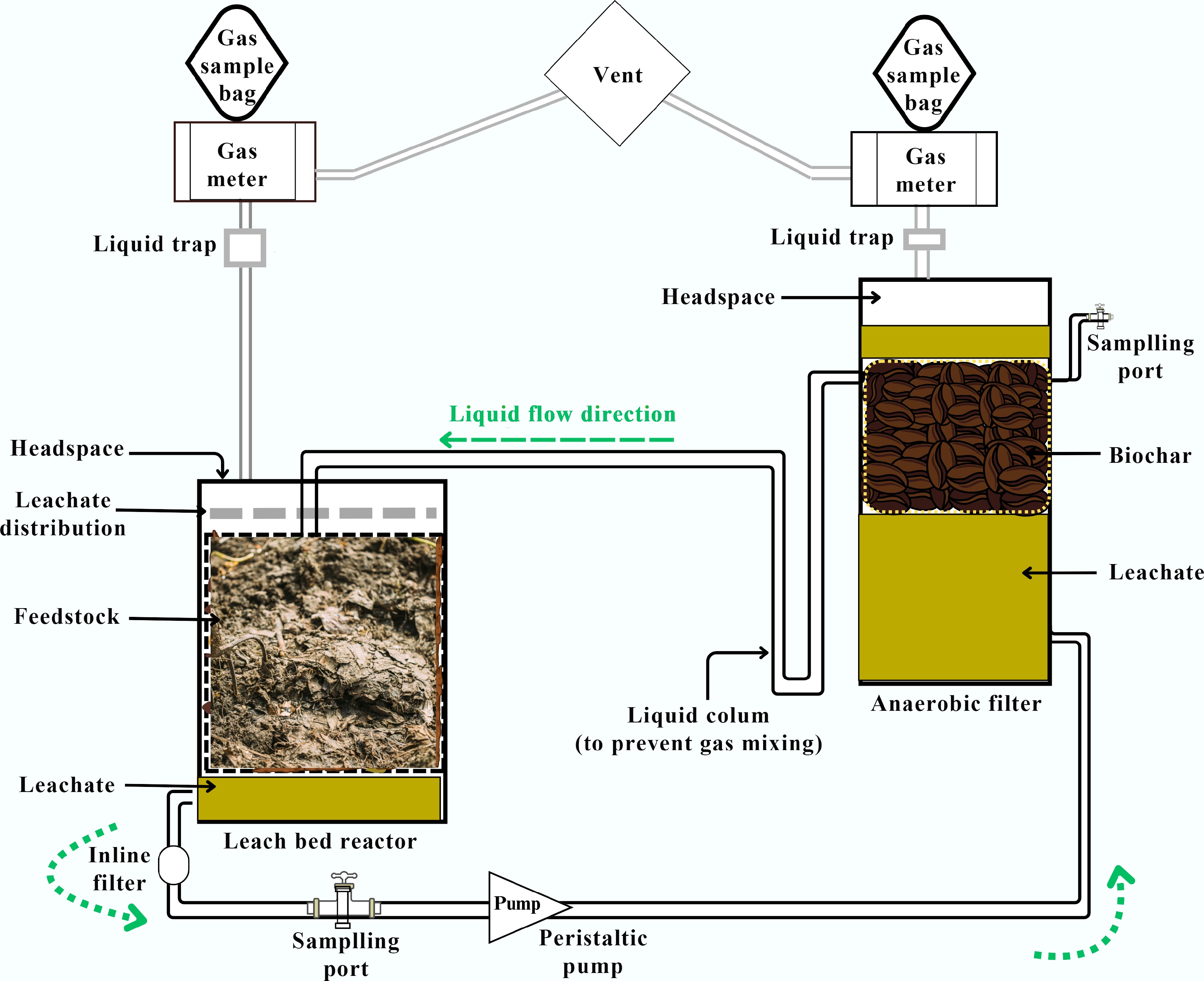

While most studies focus on prevention and mitigation of ammonia inhibition by regulating the operating parameters, some recently reported ingenious studies have demonstrated modifications to reactor configurations. Wang et al.[80] surmised that the tolerance of the AD system could be increased by enriching hydrogen-consuming microbes with exogenous H2 infusion. H2 supplementation in a side-stream digester offers a plausible alternative given the uncertainty involved in directly injecting H2 into the digestion. In the study, an amount of digestate from the primary reactor was pumped into the side-stream system each day as part of the side-stream hydrogen domestication (SHD) operation. This enables exposure to a hydrogen-rich environment for a fixed amount of time before the digestate is returned. This process lessens the negative impact of direct hydrogen input and would increase the bacteria' capacity to use hydrogen, which will increase their resistance to ammonia. At TAN 3.1 g/L, SHD was able to maintain a consistent methane production of 407.5 mL/g VS. On the other hand, at a TAN 2.3 g/L, the control group's methane production progressively dropped and eventually halted. The microbial population was altered by SHD, favouring homoacetogens and methanogenic archaea dominated by Methanosaeta. Methane generation, butyrate degradation, propionate degradation, and homoacetogenesis were among the important metabolic processes that were improved. A new type of batch dry AD system called a leach bed reactor (LBR) recycles leachate, or process liquid, that has seeped through the digestion mix (Fig. 5). By dispersing microorganisms, moisture, nutrients, and metabolites throughout the feedstock to compensate for the lack of mixing and moisture, recirculation promotes waste breakdown and conversion. Collins et al.[81] studied the impact of wood biochar made at various pyrolysis temperatures (450 to 900 °C) on the AD of chicken litter in an LBR connected to an anaerobic filter packed with biochar. For the types of biochar tested, the mean total cumulative methane outputs at 55 d varied between 152 and 164 mL CH4/g-VS. In another study, to prevent system failure that is common during dry AD, Zheng et al.[55] reported the application of a horizontal plug-flow AD reactor (HPFRAD). The OLR increased progressively to 2.80 kgVS/m3/d. The maximum CH4 production (1,059.14 L/kgVS) was obtained at a low OLR (1.90 kgVS/m3/d, whereas the largest cumulative biogas amount (3,278 L) was attained at OLR 2.80 kgVS/m3/d. In relevance to the discussion of the current review article, there was a positive correlation between the abundance of bacteria tolerant to high ammonia and VFAs concentrations. The archaea detected at high abundance were Methanosarcina. Zhao et al.[50] reported that an MEC-AD system, which combines anaerobic digestion (AD) and microbial electrolysis cells (MEC), can efficiently increase biogas yield while inhibiting ammonia. Glass was used to create a cylindrical single-chamber MEC-AD system with working capacities of 200 mL. Rectangular carbon felt measuring 3 cm in length and 2 cm in breadth served as the anode and cathode materials. The electrodes were connected to the external circuit using titanium wire (diameter: 1 mm), with a 1.5 cm gap between each electrode. The reference electrode was the saturated Ag/AgCl electrode. In the presence of 5.0 g/L ammonia stress, it was observed that CH4 production in the MEC-AD reactors was nearly three times higher than those in non-MEC-AD systems. Additional analysis showed that the activities of F420 and acetate kinase were enhanced, and in particular, DIET was robust in the MEC-AD systems. This was demonstrated by the enrichment of electroactive bacteria like Geobacter on the surface of the electrodes, the decrease in charge transfer resistance, and the increase in electroactive extracellular polymeric substance. Furthermore, proteomic research showed that in MEC-AD systems, proteins linked to ammonia detoxification were up-regulated, proteins related to ammonia transfer were down-regulated, and proteins associated with DIET, such as cytochrome c, were up-regulated. Song et al.[29] reported the construction of a CSTR with an ammonia absorption unit and a biogas recirculation ammonia stripping tank. The study ran a high-solid system for 650 d, and fed the system with chicken manure (20% TS). The authors observed that ammonia stripping decreased the TAN from 8.2 to 3.0 g/L. There was nearly a 3-fold increase in methanogenic activity, and this resulted in a high CH4 output of 0.3 L/g-VS with insignificant VFA concentration (0.6 g/L). In another innovative study, Rivera et al.[82] reported the benefit of membrane distillation (MD) on AD and ammonia recovery. A thermophilic CSTR (3 L) was paired with a membrane-based module for the digestion of urban wastewater mixed sludge. A HRT of 20 d was set, and the polytetrafluoroethylene membrane (flat sheet) module was constantly operated at 0.25 L/min of liquid recirculation rate. After 40 d MD was able to gradually lower the TAN from 0.4 ± 0.2 to 0.1 ± 0.1 g TAN/L. The NH3 extraction resulted in a three-fold increase in CH4 production. The removal efficiencies of volatile solids and chemical oxygen demand also increased by 1.4 and 1.8 times, respectively. Hence, innovative reactor configurations can play a crucial role in mitigating ammonia inhibition during AD by enhancing process stability and microbial resilience.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of a leach bed reactor. A leach bed is coupled to a biochar filter for anaerobic digestion of nitrogen-rich wastes. (The figure was adapted from reference[81]).

Machine learning and artificial intelligence

-

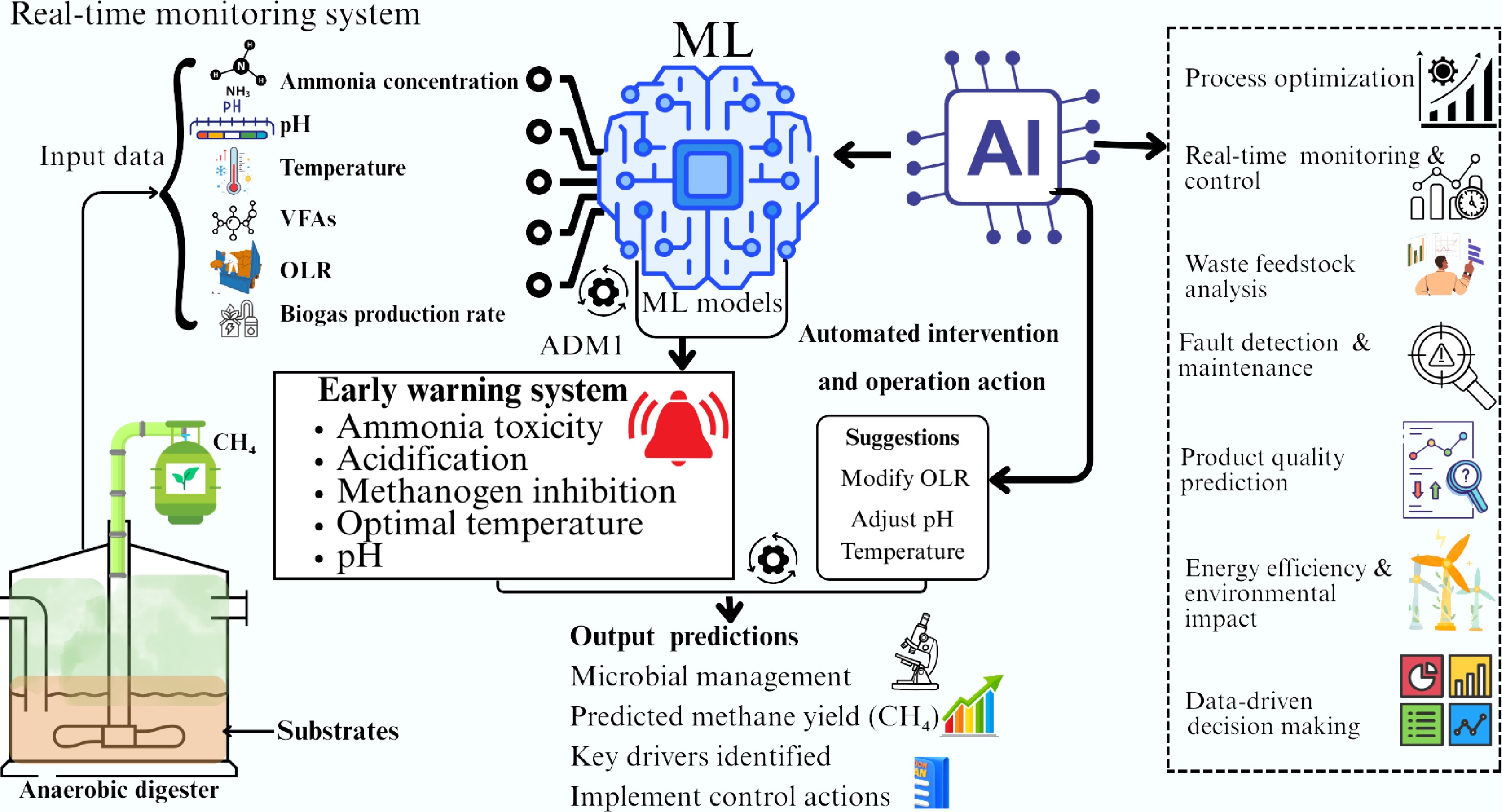

To perform high-accuracy prediction, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), which are strong new tools for data mining and model construction, can identify the possible interactions of numerous input features as well as output results. Training, validation, and testing are typically important processes in the machine learning process. Many ML algorithms, such as artificial neural networks (ANN), SVM, k-nearest neighbor, deep learning, decision trees (DTs) and ensembles, and nature-inspired optimization algorithms, have been developed to predict and optimize the operating parameters in AD systems[28]. Incorporating ML and AI can improve AD system monitoring by thoroughly determining the critical inhibition indicators and facilitating expedient automatic interventions when the reactor shows indications of instability. Figure 6 gives a schematic representation of the application of ML and AI for enhanced methane yield while monitoring and preventing system inhibition resulting from ammonia accumulation. Automated monitoring and regulation have been adopted recently for managing industrial AD reactors[83]. Real-time monitoring of chemical parameters including ammonia concentrations, and methane productivity allows for quick adjustments before serious inhibition occurs. Due to their ability to handle complicated and bulky datasets, neural networks and ML have emerged as crucial methods for forecasting the functionality and health of AD systems. These technologies foresee results, identify patterns, and maximize system performance. VFA levels and methane generation are two important indicators that can be predicted by sophisticated deep learning algorithms. These models, which are trained on historical AD data, reveal correlations between system performance and operational factors (such as pH, temperature, and OLR), allowing for accurate performance forecasts. By analysing trends that could cause a system failure, ML algorithms also play a crucial role in detecting any process imbalances or inefficiencies during the continuous fermentation process. These models can identify odd patterns in real-time sensor data that point to possible problems such as ammonia toxicity, acidification, or methanogen inhibition. ML models send operators alerts when certain criteria are surpassed, allowing for prompt failure prevention measures[84]. Tracking the changes in microbial communities and connecting them to system performance is made possible by integrating metagenomics data into machine learning models. Yu et al.[85], used a variety of machine learning models to forecast VFA, pH, and microbiological profiles in AD. Salinity and ammonia were identified as the main inhibitors by their SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis. Convolutional neural network performed exceptionally well for fatty acids, artificial neural network for Firmicutes, and extra trees for pH and microorganisms. A system for continuous AD simulation, Machine Learning-enhanced Computational Anaerobic Digestion Model No. 1 (M-CADM1) successfully integrated ML with AD Model No. 1 (ADM1) in the context of model design. VFAs and pH levels were the crucial parameters to gauge the robustness and stability of the M-CADM1 model, whereas R2 and root mean square error (RMSE) were the important parameters to assess the accuracy of the model[86]. The findings demonstrated that the pattern of pH fluctuations simulated by M-CADM1, the concentration of VFAs, and the inhibitory effects of FAN or H2 are all considerably similar to the experimental findings from reactors working in a continuous mode. ML and AI systems can offer useful data for process optimization by utilizing databases fed with substrate characterization information and large datasets gathered from real-time monitoring of industrial reactors. To guarantee effective and steady biogas production, these technologies assist operators in determining the underlying causes of instability and making prompt modifications. Real-time suggestions for modifying operational conditions are given by AI algorithms[87]. To avoid methanogen inhibition, for instance, the system can suggest lowering the OLR or modifying pH levels if an increase in ammonia is noticed. AI-integrated systems can optimize AD and biogas production while lowering the danger of system failure by adjusting operational factors (such as temperature and OLR) for better resource use and increased efficiency.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the application of ML and AI for enhanced methane yield while monitoring and preventing system inhibition resulting from ammonia accumulation.

Recently, Lian et al.[88], to determine the parametric influences on methane synthesis, used ML approaches such as feature engineering and models (k-nearest neighbors regressor, XGB regressor, linear regression, decision tree regressor and random forest regression). A greater goodness-of-fit value (0.99) was provided by the random forest model. With the lowest mean absolute error (MAE) of 296.62, the lowest root mean squared error (RMSE) of 432.46, and the greatest R2 value of 0.999, the gradient boosting regressor produced the best results, demonstrating its remarkable capacity for precise predictions. With a virtually flawless R2 of 0.99, Adaboost also demonstrated exceptional performance. This method gave each training instance a weight, focusing more on cases that were more difficult to forecast with each iteration. When compared to other applied regressor techniques, the k-nearest neighbors (KNN) regressor ranked lowest in potential, exhibiting much greater error rates and the lowest R2 of 0.98, indicating that it had difficulty with the complexity of the data. Overall, the most successful ML methods for this regression problem were ensemble methods like gradient boosting and Adaboost, which combined several weak learners to produce a powerful and accurate model with superior predictive performance. Chen et al.[39] developed a framework for automated machine learning (AutoML) and IterativeImputer to solve complex issues by automatically predicting, optimizing, and monitoring the stability of commercial-scale dry AD reactors. For data imputation, the IterativeImputer performed best (R2 = 0.91) while employing the KNN estimator. With an R2 of 0.92, the gradient boosting machine (GBM) model produced the noteworthy results for biogas prediction. A feature importance analysis revealed that the amount of biomass, liquid level, digestate amount, alkalinity (ALK), and COD, all had a major impact on the production of biogas, and provided avenues for focused optimization. Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis determined the ideal operating conditions for the 100 t/d dry AD reactor, which included biomass > 52 t/d, inoculation digestate volume of 10–20 t/d, ALK within 10,000–18,000 mg/L, and COD > 30,000 mg/L. Furthermore, an AutoML-based VFAs/ALK soft sensor was created to track system functionality, and the most important variables were found to be COD, digestate quantity, pH, and nitrogen levels. Analysis of partial dependency plots (PDPs) showed that digester failure could be successfully avoided by keeping pH above 8.2 or COD below 49,000 mg/L. This work offers a data-driven approach that is scalable to improve energy recovery from organic waste by implementing AutoML for control of complex parameters in commercial-scale DAD reactors. While several studies incorporate nitrogen content and C/N ratio in the feedstock, pH, temperature, and OLR as critical input parameters to determine system stability, to the best of our knowledge, studies that factor in an ammonia-inhibited state are unavailable. In a study by Ding et al.[89], the input data chosen were experimental variables associated with the methane yield (OLR, additive concentration, VFA, acetic acid, pH, and ammonia nitrogen). The experimental data was modelled and analyzed using two ML algorithms (RF and ANN) that are often utilized in AD. The authors found that in high OLR systems, the ammonia nitrogen concentration was controlled by the supplementation of additive, provided the OLR stayed below 2,500 mg/L. In another study, Zou et al.[90] created a soft sensor based on the VFA/ALK ratio for an optimal biogas prediction model, and evaluated eight common ML algorithms based on operational data gathered over 1.5 years from four full-scale dry reactors used for kitchen food waste treatment. The CatBoost (CB) algorithm outperformed the other eight tested models in terms of model fitting and prediction accuracy. In particular, using the test dataset, the CB model obtained a VFA/ALK R2 between 0.618 and 0.768 and a biogas production forecast accuracy (R2) between 0.604 and 0.915. The most important variables affecting the VFA/ALK indicator during dry AD were found to be FAN and COD, which together accounted for over 50% of the influence. The lack of ML-based studies focused on ammonia inhibition and mitigation is a serious research gap considering the pervasiveness of this challenge.

-

Ammonia inhibition in AD is a pervasive challenge. Notwithstanding the amount of research done to mitigate this, there still appears to be no concrete solution. This section aims to decipher the challenges associated with the currently utilized techniques, while providing possible solutions for undertaking them for better success. The determination of FAN is crucial to understand ionic strength; however, the concentration of solids also affects the pKa and produces a short-duration limit of solubility for ammoniacal substances (also known as 'salting out' of gases). As a result, it is challenging to estimate FAN, with some studies indicating that FAN is overestimated by up to 40% in various animal manures. The fluctuations in equilibrium due to mixing and time-dependent substrate input make it challenging to have a fixed range of ammonia concentration, in addition to the challenge of accurately estimating FAN. Numerous investigations have identified ammonia inhibitory thresholds in the circumstances of the given study, and the quantities measured vary greatly.

It is important to note that ammonia cannot be further broken down anaerobically for the anaerobic treatment of high ammonia waste in a standard CSTR. Studies have shown that ammonia can be removed by employing anaerobic ammonium oxidation (ANAMMOX) bacteria. However, because these slow-growing bacteria are unable to compete with the bacteria that denitrify in the anaerobic digester for the restricted amount of nitrite or nitrate, the ANAMMOX process may not occur within a reactor. Therefore, unless ammonia can be eliminated physically (such as by air stripping) or physico-chemically (such as by acid washing), the issue will typically continue once ammonia has accumulated to inhibitory levels in the digester. Further, hydrogenotrophic methanogens may not respond well to ammonia-reduction techniques such as pH and temperature modification. It has also been noted that dilution of the feedstock up to 0.5%–3% total solids can help reduce ammonia toxicity during AD. Despite this, substrate dilution raises waste amounts and drastically lowers the energy-generating potential of substrates, due to the cost of dewatering.

Conflicting studies have been presented about the functions of conductive materials under ammonia stress. For example, magnetite-powdered activated carbon (PAC) complex amendment led to inhibition of enzymes participating in the carbon dioxide reduction methanogenic pathway at 5.5 g NH4+-N/L, while magnetite supplementation produced a 36 % increase in CH4 at 5.0 g NH4+-N/L[69,91]. This disparity may be explained by distinct operating settings, and perhaps by different inoculum operational histories. Further, the magnetite-PAC amended reactors showed CO2 reduction methanogenic pathway genes downregulation when a 5.5 g N/L ammonia concentration was observed, probably suggesting DIET repression. Biochar, another favourite amendment, has a smooth surface and exceptionally small pore diameters, which could be unsuitable as a niche for microbes[92] and could have a poor ammonia alleviation effect. CMs such as carbon nanotubes (CNT) may cause inadequate stimulation of methanogenic activity due to a possible decrease in ATP synthesis and proton-motive force brought on by the obstruction of K+ transport by the CNT channels within the cell membranes[93]. Additionally, CNTs could rupture cell membranes and decrease enzyme function, as well as respiration[94]. Hence, knowledge of the many intracellular proteomic-level facilitative electron transport pathways of various CMs is pertinent. To further enhance the ammonia-inhibited reactor's performance, optimization of operational parameters is a crucial concern. One of the biggest obstacles to the long-duration use of CM-based technologies is the loss of the redox/conductive additives and associated biofilm through wash-out from the AD system. Strengthening their immobilization in the reactor may reduce such loss and produce long-lasting stimulatory effects. These immobilization techniques include attaching materials like carbon fibres in the reactors, the use of agar gel for bioaugmentation, and wrapping additives[52].

It is critical to determine the archaeal communities' response to elevated FAN concentrations, primarily due to a change in the methanogenic population following ammonia accumulation. The significance of adaptation must be taken into account in reactors where the substrates are constantly altered, such as alterations in the proportions of co-digestion substrates or addition of new influent streams; however, the microbial populations are rarely monitored in industrial reactors. Short-term VFA peaks are to be expected if feeding changes result in appreciable increases in FAN concentrations; if these peaks are not adequately controlled, they could cause reactor acidification. This is especially important in thermophilic reactors because, in contrast to mesophilic conditions, increases in the TAN input result in significantly greater FAN levels. Process stabilization and microbial adaptation may benefit from the introduction of additives, such as trace elements, to promote the growth and development of specific archaea.

Applying bioaugmentation in thermophilic AD systems is more difficult because, in comparison to mesophilic settings, thermophilic reactors are more prone to inhibition due to ammonia accumulation owing to the high operational temperatures. Further, bioaugmentation in continuous reactors remains difficult due to the requirement to prevent washout of the introduced microorganisms, even if it has proven successful in batch reactors. To date, there are only a few large-scale demonstrations, even though numerous studies have confirmed the effectiveness of bioaugmentation in reducing ammonia inhibition, possibly because full-scale facilities often operate continuously with a huge working volume, which requires a large volume of bioaugmentation inoculum. As mixed cultures have comparatively lower cultivation requirements than pure strains, using them is advised to further lower the cost of obtaining bioaugmentation inoculum. Additionally, it is necessary to develop an efficient preservation method that permits the sophisticated preparation and low-cost long-distance transportation of bioaugmentation inoculum. Successful bioaugmentation may be achieved by applying membrane reactors that facilitate biomass retention and biofilm growth, as well as by adding supporting materials to lessen the washout effect. For mature bioaugmentation to be a viable method that mitigates ammonia inhibition in AD, further large-scale studies are required. Further, another critical challenge is that methanogens have been historically less studied than bacteria[95], limiting available methodological capabilities in attempting to modulate their physiology. This is particularly stark for research on environmental microbiomes. Hence, more research initiatives should be directed towards understanding the detailed physiology of anaerobic methanogens that could lay the foundation for synthetic biology studies. In a recent study by Zhang et al.[96], the authors attributed the release of Fe2+ from ZVI to enhance microbial energy metabolism via contribution to the intracellular electron bifurcation process by enabling the formation of an electron bifurcation-coupled DIET, increasing the energy savings of hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis. Similar studies must be encouraged to provide insights into the energy-generation pathways in methanogens that could be tweaked for high ammonia stress tolerance. The role of quorum sensing (QS) in AD has gained much attention lately, and it has been reported to increase methane yield via enhancement in fatty acid oxidation, biofilm formation, syntrophic electron transfer, and modulation of the spatial distribution of microbes within a reactor[97]. The latest research has implicated the involvement of QS in the mitigation of ammonia inhibition. Chen et al.[39] reported that both 3OC6-HSL (0.5 μM), and a combination of 3OC6-HSL (0.1 μM) and biochar (4 g/L) could reduce ammonia inhibition (7,000 mg NH4+-N/L). To facilitate AD, exogenous 3OC6-HSL could control microbial social behaviors and increase EPS secretion. Additionally, microbial community structure modifications (Methanobacterium, Propionicicella, and Petrimonas) enabled the mitigation of ammonia inhibition through exogenous 3OC6-HSL and biochar. Following the addition of 3OC6-HSL and biochar, critical enzymes involved in both acidification and methanogenic processes were upregulated. Further, to reduce ammonia inhibition, low concentrations of 3OC6-HSL combined with biochar may have facilitated communication between the syntrophic bacteria and methanogens via DIET. Similar mechanistic results were obtained in another recent study by Lv et al.[98] in which it was reported that under high ammonia concentration (7,000 mg/L), iron-modified biochar (12 g) could enhance the secretion of QS molecules, primarily C4-HSL and C6-HSL, alleviating ammonia inhibition while enhancing methane yield five times more than the control. These studies demonstrate the possibility of stimulating QS mechanisms for mitigating ammonia inhibition. However, more research is needed to clarify the detailed metabolic pathways and physiological modulations under various practical situations to apply this strategy efficiently. The majority of research on IET stimulation to enhance CH4 synthesis under ammonia inhibition has been carried out in lab-scale bioreactors. To undertake techno-economic analysis and assess the long-term consequences of such technologies (e.g., conductive materials and bioaugmentation), more research focused on continuous operation of pilot scale reactors is required. Further research is required to determine efficient separation and recovery techniques for the altered additive, including conductive compounds.

In packed bed columns, the development of scaling and fouling as a result of residual particles from the AD effluent is one of the main obstacles. Effective separation of solids and liquids, and incorporating a lime softening protocol prior to stripping, are therefore essential; nevertheless, frequent cleaning and expensive maintenance would be needed. To address the aforementioned issue, stripping columns without internal packing have been developed; nevertheless, only a few have been used on a pilot or large scale[99].

The microbial communities predominant in the process of high ammonia MEC-AD could be systematically revealed by further studies that fully integrate macro-genomic, macro-transcriptomic, and macro-proteomic data. This would maximize ammonia mitigation through gene expression regulation and allow for a thorough examination of the relationship between voltage and microbial populations. Further, there is a need to create sophisticated intelligent algorithms to automate the recognition and evaluation of intricate genetic traits. This will increase the effectiveness, precision, and dependability of data processing and offer more accurate assistance for extensive genomic research.