-

Aquaculture has emerged as the fastest-growing sector in food production, achieving a yearly increase of 7.5% since 1970 to meet the continuously rising demand for fish[1]. Higher fish consumption and stagnant yields from capture fisheries have driven this increased demand, leading to greater reliance on cultured fisheries. To sustain current fish consumption levels, worldwide aquaculture output needs to reach 109 million tons by 2030[2]. Notably, experts recognize the intensification of aquaculture systems as a promising strategy to meet substantial fish demand, particularly as land resources become increasingly limited. Moreover, the success of aquaculture largely depends on the quality of the cultural environment, as well as the physiology and health status of the fish. Over time, the widespread use of pesticides, antibiotics, and synthetic growth promoters has become commonplace in aquaculture aimed at boosting production levels. However, the indiscriminate application of these synthetic chemicals has resulted in environmental imbalances, stress, and disease outbreaks, which in turn have led to immune suppression in aquatic animals[3].

In intensive aquaculture, infectious diseases have led to substantial financial setbacks[4]. Antibiotics and chemotherapeutics incorporated into aquafeeds may treat certain bacterial pathogens; however, numerous countries have prohibited the incorporation of antibiotics into animal feed. This ban is primarily due to the worldwide increase in antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, weakened immune systems, concerns regarding antibiotic residues in fish tissues, and detrimental environmental impacts[3,5]. Dietary additives have emerged as effective alternatives to boost the immune response in aquatic species and reduce disease incidence. These additives are considered safe, non-toxic, cost-efficient, and environmentally sustainable[6]. Consequently, there has been a movement towards developing safer, ecologically sound, and economically viable organic components and alternatives to antibiotics in feed, including probiotics and prebiotics, to manage microbial diseases in aquaculture[7,8].

Prebiotics are mostly carbohydrates, which cannot be broken down. These include inulin, xylooligosaccharides (XOS), galactooligosaccharides (GOS), fructooligosaccharides (FOS), and mannanoligosaccharides (MOS). Naturally, prebiotics help the growth of good gut microbiota, which then stops the growth of pathogenic microorganisms by lowering the number of places where pathogens can attach, changing the pH of the gut, making antimicrobials like bacteriocins, lowering the ability of pathogens to infect others, and boosting the host immune system[9,10].

Recent research has increasingly focused on XOS owing to their potential applications in this field[11,12]. XOS is a naturally occurring prebiotic composed of xylose-based sugar oligomers that cannot be digested and are linked by β1-4 glycosidic bonds. The lower gastrointestinal tract can break down these substances into short-chain fatty acids, which promote the proliferation of beneficial bifidobacteria and lactobacilli, and improve immune responses in fish species. In poultry, XOS has been shown to decrease Salmonella colonization in a dose-dependent manner, and in vitro studies have indicated that XOS can reduce the adhesion of this pathogen to intestinal epithelial cells[13]. While there is limited evidence regarding the immune-modulating effects of XOS, some studies suggest that they may enhance lymphocyte proliferation and attenuate inflammatory responses. Compared with other prebiotics, research on the effects of XOS in fish remains limited. This review aims to outline the effects of XOS prebiotics and explain their mechanisms of immune response, antioxidant capacity, inflammatory signals, and intestinal microbiota in fish species.

Production methods of XOSs

-

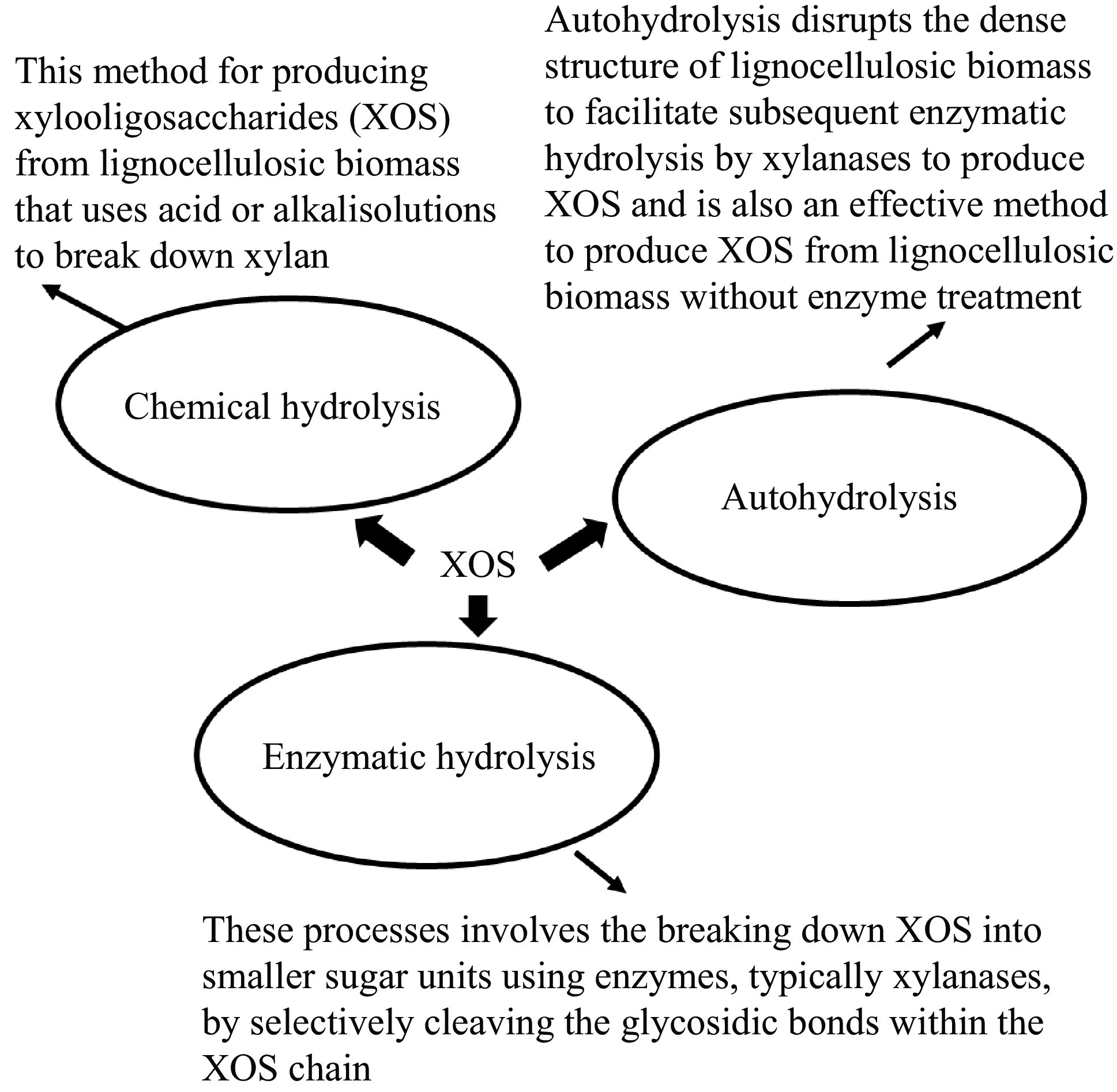

Xylooligosaccharides (XOS) are composed of xylose oligomers linked by β-(1,4)-linkages. They are derived from xylan-rich lignocellulosic biomass using methods such as autohydrolysis (high-temperature steaming), chemical hydrolysis, and enzymatic hydrolysis (Fig. 1). The choice of technique for XOS production and purification depends on factors such as the quantity and intended use[14]. XOS are efficiently produced through a combination of chemical, thermal, and enzymatic processes, minimizing by-products and monosaccharides. The process begins with alkali treatment to extract xylan from the biomass, followed by hydrolysis using xylanase enzymes to produce XOS[15].

XOS have a lower viscosity, which helps minimize water activity and increase water retention[16]. XOS are water-soluble, so it is recommended that they be pelleted before feeding to fish. High-quality pellets are more water-resistant and less likely to disintegrate, helping the feed retain nutrients until consumption. The structure of XOS varies based on the source of xylan, as well as factors such as monomeric units, polymerization degree, linkage type, and side group interactions[16]. Incorporating side groups such as arabinose, acetyl groups, or glucuronic acid creates varied XOS profiles with distinct biological characteristics and properties[16]. XOS have been produced from a variety of xylan-rich lignocellulosic biomasses, including corncobs, bamboo shoots, citrus peels, sugarcane bagasse, barley husks, rice hulls, softwood and hardwood materials, and various agricultural residues like wheat straw, corn husks, and cotton stalks[16].

-

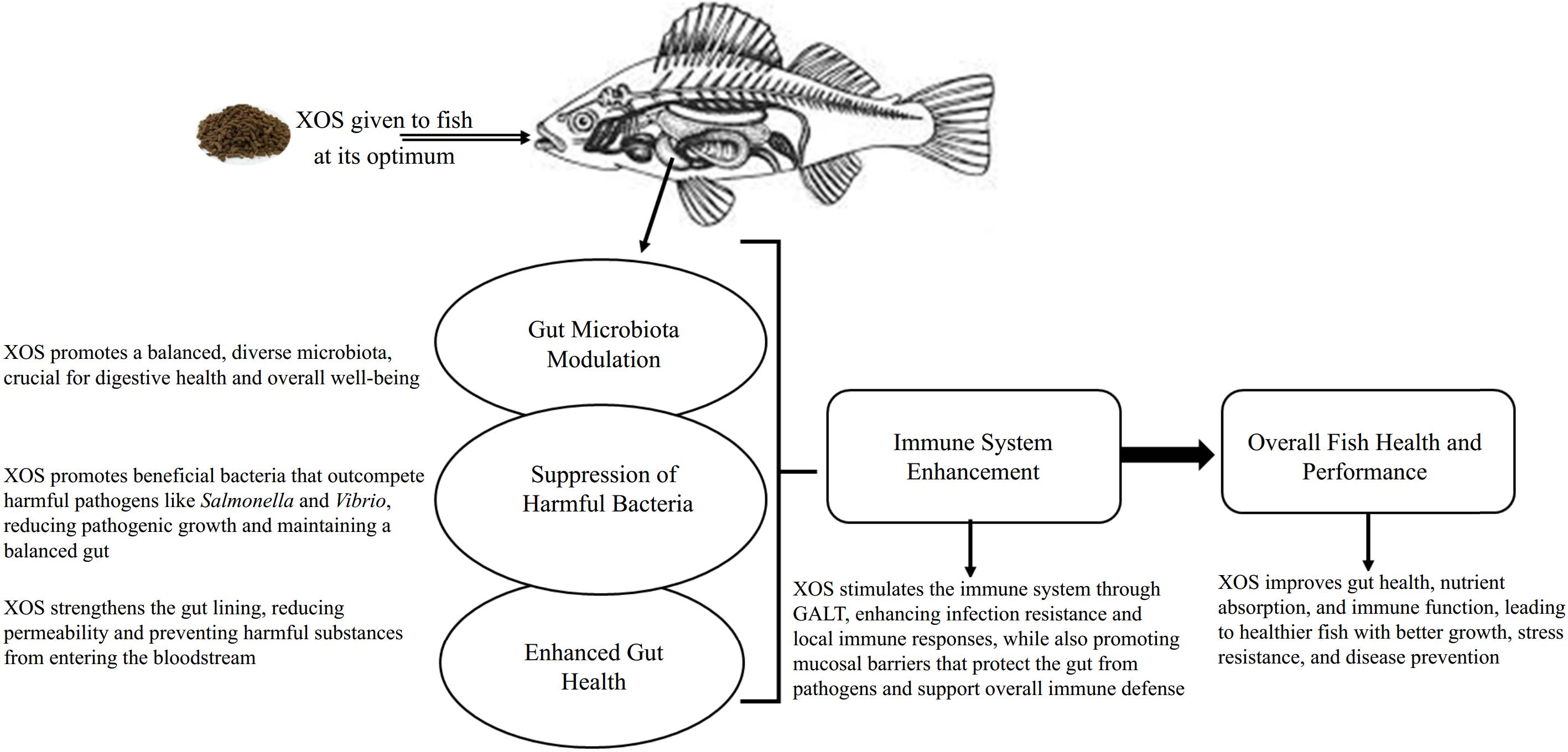

The inclusion of XOS in aquafeeds represents an innovative approach to enhancing the health and nutrition of aquatic species. As an emerging additive in aquafeeds, XOS has attracted attention for its potential to improve fish health, growth performance, and overall aquaculture sustainability (Fig. 2)[17]. Below are some detailed insights into how XOS works in aquafeeds and the benefits it offers.

Effect of dietary XOS on growth performance, feed utilization, and digestive enzymes in aquatic species

-

Digestive enzymes are essential for linking growth performance and feed utilization, as they break down nutrients in food, enabling the body to absorb and use them effectively for growth[18]. Increased digestive enzyme activity improves nutrient absorption, leading to better growth and more efficient feed use. In aquaculture, 'growth performance' refers to how efficiently farmed aquatic organisms, such as fish or shellfish, gain weight over time[19]. This is typically measured by parameters like specific growth rate (SGR), weight gain, feed conversion ratio (FCR), and survival rate, which reflect the overall health and productivity of the cultured population[20].

Dietary XOS may enhance fish growth by fermenting in the gut, where beneficial microbiota produce microbial biomass or metabolites that the host can use. For example, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced during fermentation are absorbed by epithelial cells, providing energy and improving glucose and lipid absorption and metabolism[21]. Additionally, XOS fermentation helps prevent the growth of harmful gut pathogens and provides energy from the simple sugars produced. Fermentation by beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium species and lactic acid bacteria (LAB), boosts glycolysis and digestive enzyme activity, which leads to better growth and body composition in fish[21]. The effect of XOS on growth performance is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Effect of dietary XOS on growth performance, feed utilization, and intestinal health in aquatic species.

Aquatic species Dosage in the experiment Species weight (g) Time of culturing Experimental outcome Ref. D. labrax European seabass 1% XOS 60 49 d Significantly increases weight gain (WG), feed conversion ratio (FCR), protein efficiency ratio (PER) among dietary treatment [10] Megalobrama amblycephala Blunt snout bream 0.5%, 1.5%, 2.3%, and 3% XOS 46.85 ± 0.34 8 weeks 1.5% XOS increased the daily growth index, feed efficiency ratio, nitrogen, and energy retention, and enhanced intestinal enzyme activities, including lipase, alkaline phosphatase, Na+K+-ATPase, protease, carboxypeptidase A, aminopeptidase N, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase. [22] Megalobrama amblycephala Blunt snout bream 0.5%, 1.5%, 2.3%, and 3% XOS 46.85 ± 0.34 8 weeks Fish fed 1.5% XOS had higher FW, WG, and PER, but a lower FCR. [7] Cyprinus carpio Common carp 5, 10, 20, and 30 g/kg XOS 19.61 ± 0.96 8 weeks Fish fed 10−20 g/kg XOS showed higher FW, WG, SGR, and PER, with a lower feed conversion ratio. [17] Cyprinus carpio Common carp 0.5%, 1%, 2%, and 3% XOS 19.61 ± 0.96 56 days Fish offered 1% -2 XOS supplementation significantly obtained a higher body mass index and feed efficiency ratio, intestinal protease, lipase, creatine kinase, and sodium/potassium ATPase activities compared to other groups. [23] Rutilus frisii kutum fry Caspian white fish 1%, 2%, and 3% 1.54 ± 0.03 8 weeks Although fish fed 3% XOS had the highest final weight, weight gain, SGR. and lowest FCR, no statistically significant differences were observed between final weight, weight gain, SGR, CF, and FCR of fry fed control or XOS supplemented diets [9] Litopenaeus vannamei White leg shrimp 1, 2, 4, and 6 g/kg 0.10 ± 0.01 60-d Supplementing 4–6 g/kg of xylooligosaccharides improved feed efficiency, survival rate, and intestinal villi length and area, with no significant change in FBW or weight gain rate. [24] Ctenopharyngodon idella Grass carp 0.002%, 0.004%, 0.006%, 0.008%, and 0.010% 167.46 ± 0.61 60 d Enhanced growth performance (and intestinal growth (intestinal length (IL), intestinal weight (IW), and Intestosomatic index ISI). [25] Ctenopharyngodon idellus juvenile Grass carp 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.4%, and 0.6 % 3.05 ± 0.01 8 weeks Fish fed dietary 0.05%, 0.1%, and 0.2% XOS displayed significantly higher final body weight, weight gain and specific growth rate compared to the control group. [20] Oreochromis niloticus × O. aureus Blue tilapia 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 g/kg 5.00 ± 0.02 8 weeks XOS supplementation significantly improved WG and nutrient retention while reducing FCR. The 2 g/kg XOS group showed the highest WG and lowest FCR. [26] Oreochromis niloticus) fingerlings) Nile tilapia 5, 10, and 20 g/kg CDXOS 20.72 ± 0.02 4 and 8 weeks In the CDXOS groups, FW, WG, SGR, and FCR were significantly improved, with the greatest improvement in the 10 g/kg CDXOS treatment. [27] Triploid Oncorhynchus mykiss f Rainbow trout 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, and 10.0 g/kg 20.85 ± 0.48 56 d Fish fed 10 g/kg XOS showed significantly improved weight gain, enhanced intestinal lipase and amylase activity, and increased villi height in intestinal histology. [28] juvenile Pelodiscus sinensis Chinese softshell turtle 50, 100, 200, and 500 mg/kg XOS 12.26 ± 0.32 30 d XOS supplementation improved P. sinensis growth, with 200 mg/kg showing the highest growth rate. All trials had lower FCR and higher intestinal enzyme activity than the control. Amylase activity was highest in 100 mg/kg XOS, while protease activity was slightly higher. The optimal XOS supplementation is 100–200 mg/kg. [21] Carassius auratus gibelio Crussian carp Diet 1: 50 mg/kg; diet 2: 100 mg/kg; diet 3: 200 mg/kg 16.88–17.56 45 d The study found significant differences in RGR and DWG between diets 1–3 and the control, with no effect on survival rate. Fish fed diet 2 showed significantly different amylase and protease activity in their intestine and hepatopancreas compared to the control and diet 3. [29] Sparidentex hasta Silver black porgy 5 and 10 g of XOS per kg 35.64 ± 0.30 8 weeks XOS supplementation did not affect sobaity seabream growth or feed utilization. However, protease activity significantly decreased in fish fed 0.5% XOS, while lipase and amylase activities remained unaffected. [12] Labeo rohita Rohu 0.5%, 1%, and 2% 25 ± 0.05 90 d Adding 1% XOS to a 75% RPC-based diet significantly improved the growth, weight gain, specific growth rate, protein efficiency ratio, and feed conversion ratio of rohu fingerlings. Intestinal shape and digestive enzyme activity also improved. Polynomial regression indicated optimal growth at 1.25% XOS. [30] Apostichopus japonicus Selenka Japanese sea cucumber 0.015%, 0.030%, 0.045%, 0.060%, and 0.075% 6.80 ± 1.05 75 d Adding 0.030% to 0.060% XOS to juvenile sea cucumber diets increased digestive enzyme activity and promoted growth. The optimal XOS supplementation is 0.044%, with a recommended duration of about two months. [31] juvenile Litopenaeus vannamei. White leg shrimp 200, 400, and 600 mg/kg 0.67 ± 0.02 6 weeks The results showed that the WGR, SGR, ER, and protein deposition rate (PDR) were greatly enhanced while the FCR was dramatically decreased by adding 200 mg/kg in the diet. [32] Effect of XOS on immune response in aquatic species

-

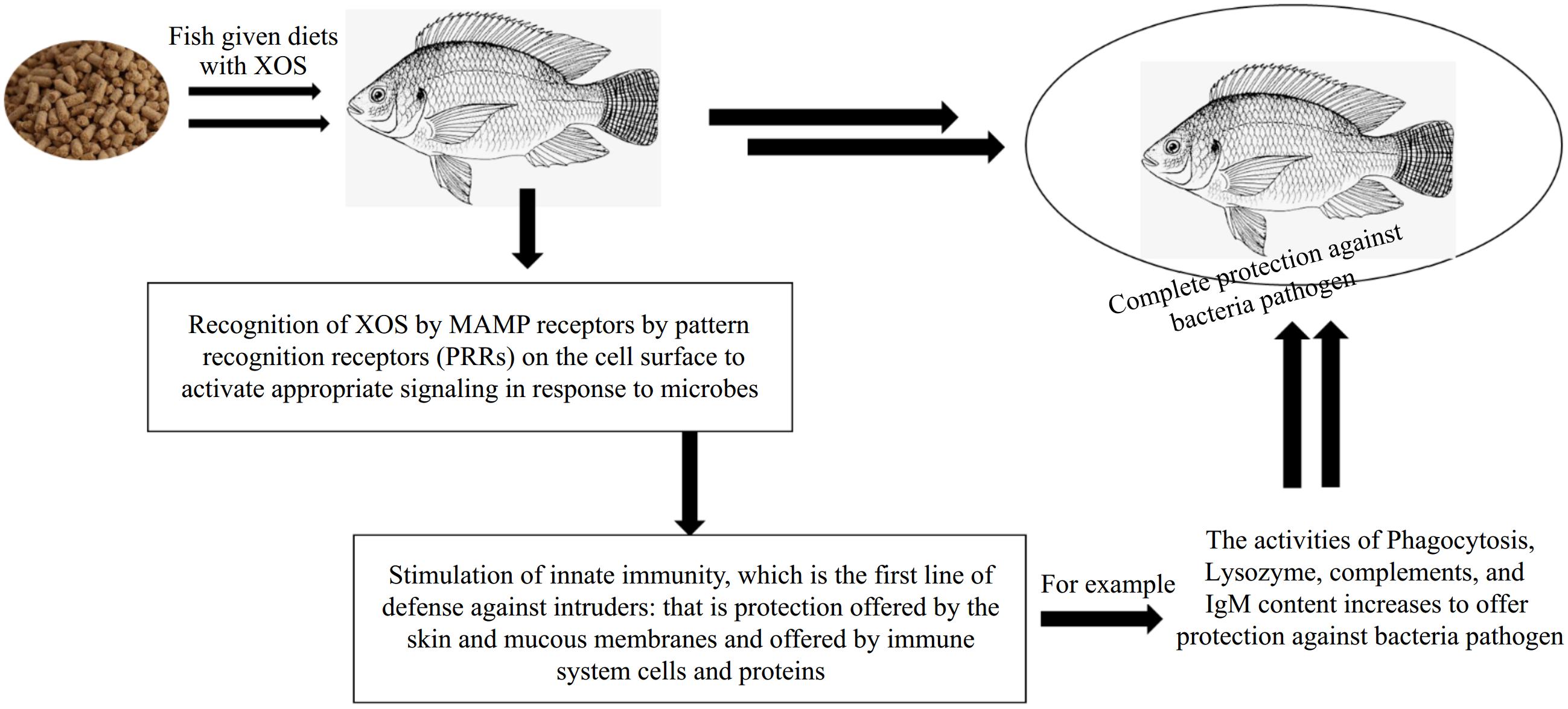

Teleost fish possess two types of immune systems: innate and adaptive. Both systems react to infection via cellular and humoral mechanisms[33]. Complement systems, lysozymes, phagocytic activity, respiratory activity, and cytokines are examples of non-specific immune processes in fish[34]. The main line of protection against diseases caused by viruses and poisons is innate immunity. Its immune-modulating effects are caused by the direct interaction of XOSs with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) expressed by macrophages. These PRRs include the β-glucan and dectin-1 receptors. The contact between the ligand and receptor triggers signaling molecules such as Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB), which in turn activates immune cells[35]. Microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) are another way in which saccharides may interact with PRRs and cause an immunological reaction (Fig. 3). Therefore, it seems that XOS stimulates the innate immune system in two different ways: first, by directly activating it and second, by promoting the development of commensal microbiota.

Figure 3.

The systematic presentation of XOS in immune response, producing protection against bacterial pathogens by activating the immune system cells through pattern recognition.

XOS can modify both humoral and innate immunity, thereby improving mucosal integrity, boosting overall immunity, and increasing disease resistance[23]. Several studies have shown that consuming XOS can greatly increase the activity of several enzymes, such as respiratory enzymes, myeloperoxidase content, and phagocytic activity in fish species. In one study, researchers fed experimental diets containing varying amounts of XOS (1%, 2%, and 3%) and a control diet (0%) to Caspian whitefish fry (Rutilus frisii kutum) for eight weeks. The skin mucus of these fish showed high levels of protein and antibacterial activity. Fish treated with 3% XOS exhibited the highest levels[9]. Additionally, after bacterial infection, the levels of acid phosphatase (ACP), alkaline phosphatase (AKP), lysozyme (LYM), complement 3 and 4, myeloperoxidase (MPO), and IgM significantly increased in blunt snout bream compared to those in fish fed a control diet without any XOS supplements, indicating their enhanced ability to fight off infections[7]. Higher levels of these parameters typically indicate enhanced immune competency, which protects fish during the initial phases of wound healing[36]. In addition, XOS fermentation byproducts, including acetate, propionate, butyrate, and lactic acid, are essential for health because they help produce bifidobacteria and modulate the immune system of the host[16].

Fish that were fed a high-fat diet (HFD), on the other hand, had much lower amounts of MPO, acid phosphatase, lysozyme activity, and immunoglobulin content. This suggests that the HFD may weaken the immune system. However, supplementation with 1.5% XOS reversed this parameter[23]. The goal of another study was to determine how XOS (0, 5, and 10 g of XOS per kg) affects the immune and blood systems of juvenile Sobaity seabream (Sparidentex hasta) for eight weeks. The results showed that varying doses of the prebiotic did not significantly affect haematological or immunological markers, but they did notice a significant variation in complement activities[12]. In another study, fish that were fed 0.1% XOS had higher plasma lysozyme activity after eight weeks than the control group of juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)[20].

In fingerlings of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) that received diets enriched with 10% CDXOS, there was a significant increase in skin mucus LYM and peroxidase activities, coupled with serum immune parameters (LYM, respiratory burst activity, phagocytosis index, peroxidase, and alternative complement activities), after 8 weeks of feeding[11]. Another study found that after 8 weeks, the activities of AKP, ACP, LYM, complement 3 and 4, and IgM levels in the serum of crucian carp increased significantly[37]. Over 60 d, Sun et al.[24] showed that shrimp fed 4 and 6 g/kg of XOS diets had higher levels of phenoloxidase and lysozyme activities than individuals in the control group. This study suggests the use of XOS as a feed supplement in the practical diet of juvenile L. vannamei.

In sobaity (Sparidentex hasta) fingerlings that were fed different diets (Lactobacillus plantarum (LP) and XOS) showed no impact on the activity of total immunoglobulin and lysozyme[38]. Differential hemoglobin concentration, white blood cell (WBC) count, hematocrit content, and red blood cell count were not notably influenced by differing levels of dietary XOS, but notable variations were seen in the total white blood cell counts between the experimental and control groups. After eight weeks of feeding, fish fed 5 g/kg XOS and those given 10 g/kg XOS had the highest and lowest WBC counts, respectively[12]. Another study revealed that dietary XOS enhanced the immune status of white sea bream (Diplodus sargus) by increasing lysozyme levels, total immunoglobulin, and alternative complement pathway activity (ACH50). However, it had no effect on hemoglobin, red blood indices, total blood cell counts, hematocrit, or differential white blood cell counts[24].

In summary, the immunostimulatory effects of XOS are likely linked to its ability to recognize patterns or to its indirect support of beneficial gut bacteria, which may have immunostimulatory roles[7]. Therefore, XOS appears to activate the immune system either through direct activation of the innate immune response or by promoting the proliferation of beneficial microbiota.

Effect of dietary XOS on antioxidant capacity in aquatic species

-

The molecule O2, which is essential for the survival of numerous organisms on Earth, is involved in all oxidation reactions that are characteristic of aerobic cellular metabolism. In the electron transport chain, it serves as the final electron acceptor, enabling the mitochondria to produce ATP. These processes result in the reduction of O₂ to water. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen species are reduction intermediates formed when electrons react directly with O₂. These include hydroxyl radicals (·OH), superoxide radicals (·O2−), peroxynitrite (ONOO−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and other radicals[39,40]. It is estimated that approximately 3% of the O₂ utilized by the cell is improperly reduced.

Organisms have developed an antioxidant defense mechanism consisting of two main types of antioxidants: (1) the enzymatic antioxidant system, which encompasses various enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx), glutathione reductase (GR), catalase (CAT), and superoxide dismutase (SOD); and (2) the non-enzymatic antioxidants, which include substances like glutathione, thioredoxin, vitamin C, and vitamin E[39]. As noted by Martínez-Álvarez et al.[41], these elements of the antioxidant defense mechanism help to maintain a balance between the production and removal of reactive oxygen species under normal physiological conditions. A breakdown in this system and the resultant oxidative stress can occur if homeostasis is disrupted; thus, the integrity of this system is essential[42−44].

Therefore, the process by which XOS reduces the excessive formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) may be related to their composition, which includes ester-linked phenolic acids such as ferulic acid. These compounds can neutralize and absorb free radicals, break down peroxides, and inhibit chain reactions[45]. For instance, fish fed a high-fat diet (HFD) exhibit significantly lower levels of SOD, CAT, and GPX. However, this effect was reversed in common carp fed an HFD supplemented with XOS after eight weeks[23]. Additionally, dietary supplementation with Bacillus subtilis and XOS significantly increased the activities of CAT, GPX, SOD, and total antioxidant capacity, while significantly decreasing malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in crucian carp (Carassius auratus)[37]. CAT activity was further reduced in fish fed plant-based (PF) diets supplemented with XOS, while prebiotics also decreased SOD activity. The activity of all antioxidant enzymes declined with XOS supplementation in fish-fed fish meal (FM) diets. Lipid peroxidation (LPO) levels and gut morphology were largely unaffected by dietary supplements containing XOS and short-chain fructooligosaccharides (scFOS). Nevertheless, dietary XOS decreased antioxidant enzymatic activity in both PF and FM diets, suggesting a beneficial effect on the reduction of reactive oxygen species formation in the liver[10].

Fish fed 0.1% XOS exhibited significantly lower plasma MDA levels but did not affect liver SOD activity or GPX content. However, MDA levels were significantly reduced by 0.4% and 0.6% in juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)[20]. In the liver, all XOS groups exhibited a significant improvement in SOD activity, but the X-3 and X-4 groups of tilapias (Oreochromis niloticus × O. aureus) showed a considerable increase in catalase activity. Additionally, liver SOD, CAT, and GPX activities were significantly increased, whereas the opposite pattern was observed in MDA content in blunt snout-bream-fed XOS supplemented with rice protein concentrate for eight weeks[7]. A significant decrease in plasma MDA was observed at the 1% XOS level in 75% RPC-based diets in Labeo rohita after 90 d of feeding[30]. In comparison to the control group, the activities of SOD and peroxidase (POD) in the serum and hepatopancreas, as well as serum total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) in the G200 group, were notably elevated. T-AOC in the hepatopancreas of the experimental groups was also significantly elevated, and the activity of hepatopancreatic anti-superoxide anion radical (Anti-O2−) in the 400 mg/kg group was significantly increased. In contrast, hepatopancreatic MDA content in the 400 mg/kg group and serum MDA content in the experimental groups were significantly reduced in juvenile Litopenaeus vannamei after six weeks of feeding[32].

Effects of dietary XOS on disease resistance in aquatic species

-

Disease resistance refers to the ability to prevent or reduce the incidence of diseases in susceptible hosts[46]. This resistance can arise from genetic or environmental factors including incomplete penetrance. Disease tolerance is defined as the ability of a host to mitigate the impact of disease on health[47]. In fish, stimulation of the innate immune system by XOS is believed to be the primary defense mechanism against opportunistic infections. In three experiments, European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) exhibited a significant increase in disease resistance owing to dietary XOS. Notably, dietary XOS substantially enhanced the resistance of Nile tilapia to Streptococcus agalactiae, with survival rates of 55% and 60% recorded in each study[11]. Compared to the groups receiving 5 g of XOS per kg, 20 g of XOS per kg, and the control group, Nile tilapia fed a diet comprising 10 g of XOS per kg showed significantly higher relative survival rates and increased resistance to S. agalactiae[27].

In the European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), 10 g of dietary XOS significantly increased disease resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila, showing the highest level of disease resistance. A similar result was observed in blunt snout bream fed a diet supplemented with 2% XOS and RPC[7], as well as in Ctenopharyngodon idella fed 0.1% XOS[20], compared to the control diet. Furthermore, dietary XOS significantly reduced cumulative mortality in tilapia following injection with Aeromonas hydrophila[26]. Among the supplemented groups, the inclusion of 10 g/kg CDXOS resulted in significantly higher relative percentage survival (RPS) and resistance to Streptococcus agalactiae than the other groups[27]. Additionally, supplementing diets with 4–6 g/kg of xylooligosaccharides improved survival rates and enhanced the resistance of juvenile Litopenaeus vannamei against Vibrio alginolyticus[24]. According to Guerreiro et al.[48], prebiotics may improve disease resistance by boosting mucosal immunity and promoting beneficial gut flora that prevents pathogenic bacteria from colonizing the stomach. Although innate immunity stimulated by dietary XOS may also enhance fish resistance to illnesses, its potential direct effects are still unknown.

Effect of dietary XOS on anti-inflammatory activity signals in aquatic species

-

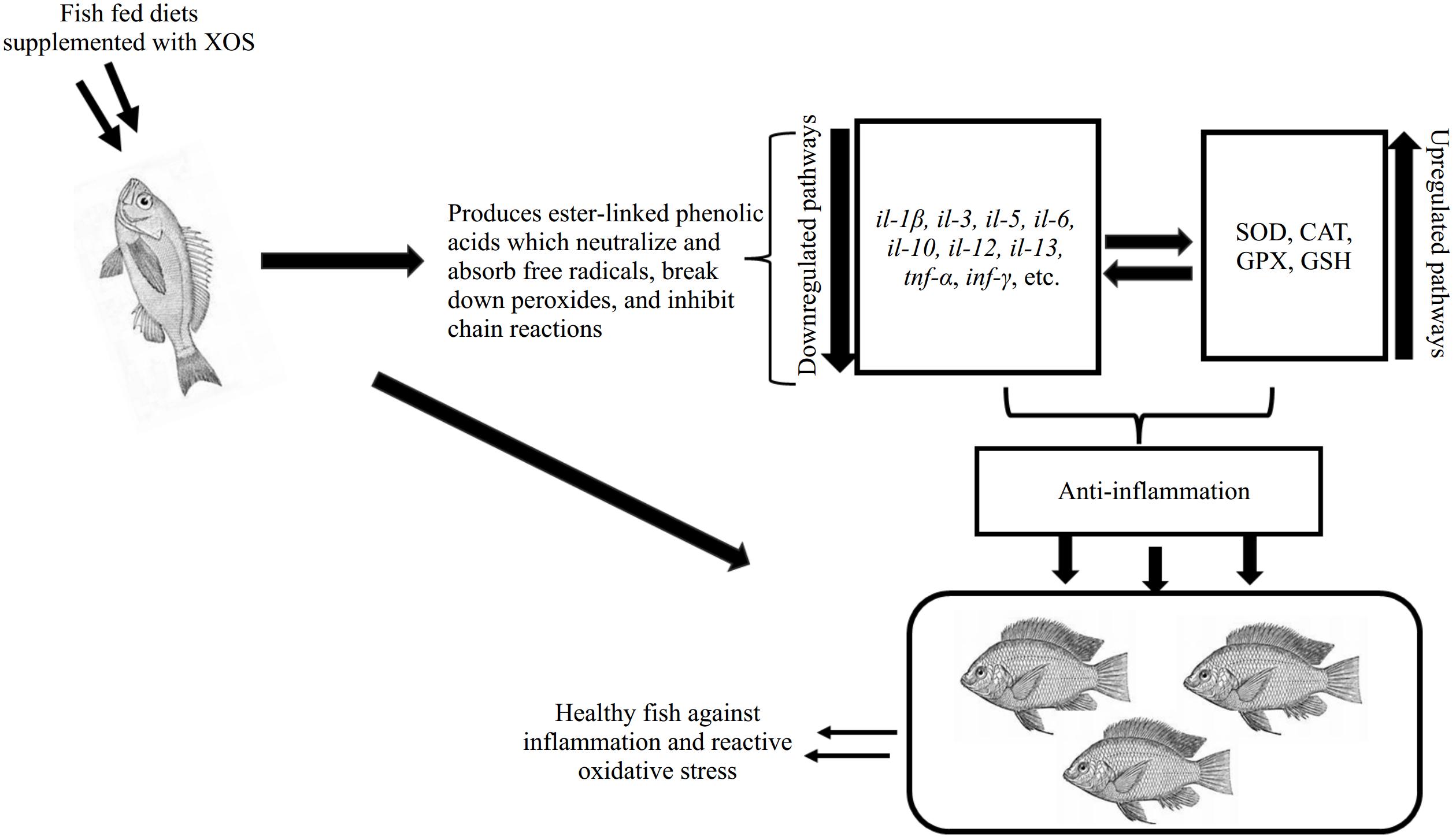

Cytokines play a crucial role as mediators of the immune response during inflammation. The balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines is essential for an effective immune response, whether in a state of homeostasis or during inflammation related to various diseases (Fig. 4)[49]. Deregulation of cytokines is linked to numerous diseases, including autoimmune disorders and infections. Abnormal production or signaling of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukins plays a significant role in chronic inflammation and tissue injury. Excessive or uncontrolled release of cytokines, a phenomenon referred to as cytokine storm, can result in severe inflammation and organ damage, ultimately leading to immune suppression and increased mortality[50].

Figure 4.

Systematic presentation of XOS inhibiting inflammatory signals through the up-regulatory mechanism involves in antioxidant expression.

Research suggests that the immunomodulatory effects of XOS are associated with its antioxidant properties, which help to maintain the balance between the two types of cytokines. However, this was reported to be linked to phenolic compounds, which absorb free radicals and break down excessive ROS production, leading to excess cytokine reactions[45]. This has been demonstrated in both livestock and aquatic species. For instance, in fish species, XOS feeding increased il-10 and tgf-β expression in Carassius auratus intestines while suppressing the expression of myd88, hsp90, tnf-α, il-1β, and tlr4[37]. Furthermore, in the intestinal tissue of triploid Oncorhynchus mykiss, Wang et al.[28] showed that dietary XOS (0.75% and 1%) boosted the expression of the il-10 gene while reducing the expression of tnf-α and il-6, in contrast to the control group. Fish given 7.5–10.0 g/kg of XOS exhibited a significant increase in the expression of the claudin-1 and zo-1 genes[28]. This indicated that XOS supplementation may enhance the stability and integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier by increasing the expression of genes encoding tight junction membrane proteins. Taken together, these results suggest that dietary XOS can both preserve and improve the integrity of the gut mucosa by promoting tight junction formation and altering gene expression to modify the immune response.

Compared with the control group, the high-fat diet (HFD) group exhibited increased intestinal expression of il-1β, il-8, tnf-α, ifn-γ, caspase-3, and caspase-9. Conversely, a decrease in the expression of sod, gpx, lym, complement 3, and mucin 5b (muc5b) was observed, but this effect was reversed when the diet was supplemented with XOS at 1%–3% in common carp after eight weeks, suggesting the stimulation of the transcriptional activation of specific pro-inflammatory genes that perform specific functions, such as tissue repair or antimicrobial activity[23]. Nevertheless, the authors linked this result to the concentration of SCFAs in the intestine, generated by the thriving gut microbiota, which engages with G protein receptors on immune cells, thereby reducing pro-inflammatory signals. In a separate study, Liu et al.[37] found that in crucian carp (Carassius auratus), the expression levels of tgf-β and il-10 were significantly higher in the bacillus subtilis, XOS, and bacillus subtilis+ XOS groups compared to the control group, while the expression levels of tnf-α, heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), tlr4, il-1β, and myd88 were significantly lower in crucian carp (Carassius auratus).

Additionally, Azeredo et al.[51] found that plant proteins supplemented with XOS in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) downregulated immune gene expression in the gut and partially enhanced the systemic response. In contrast, the FOS prebiotics showed the opposite effect. The varying results from substituting fishmeal with plant protein (PP)-based ingredients underscore the necessity for additional research that takes into account both local and systemic responses. The different outcomes of prebiotic supplementation suggest site-specific effects without definitive interaction with protein sources. Interestingly, XOS supplementation did not affect the mRNA levels of caspase-8, bcl-2, and factor-related apoptosis ligand in the proximal intestine, and jnk, caspase-9, bax, or apaf-1 in the distal intestine in comparison to the control group in grass carp[25].

Effects of dietary XOS on intestinal microbiota in aquatic species

-

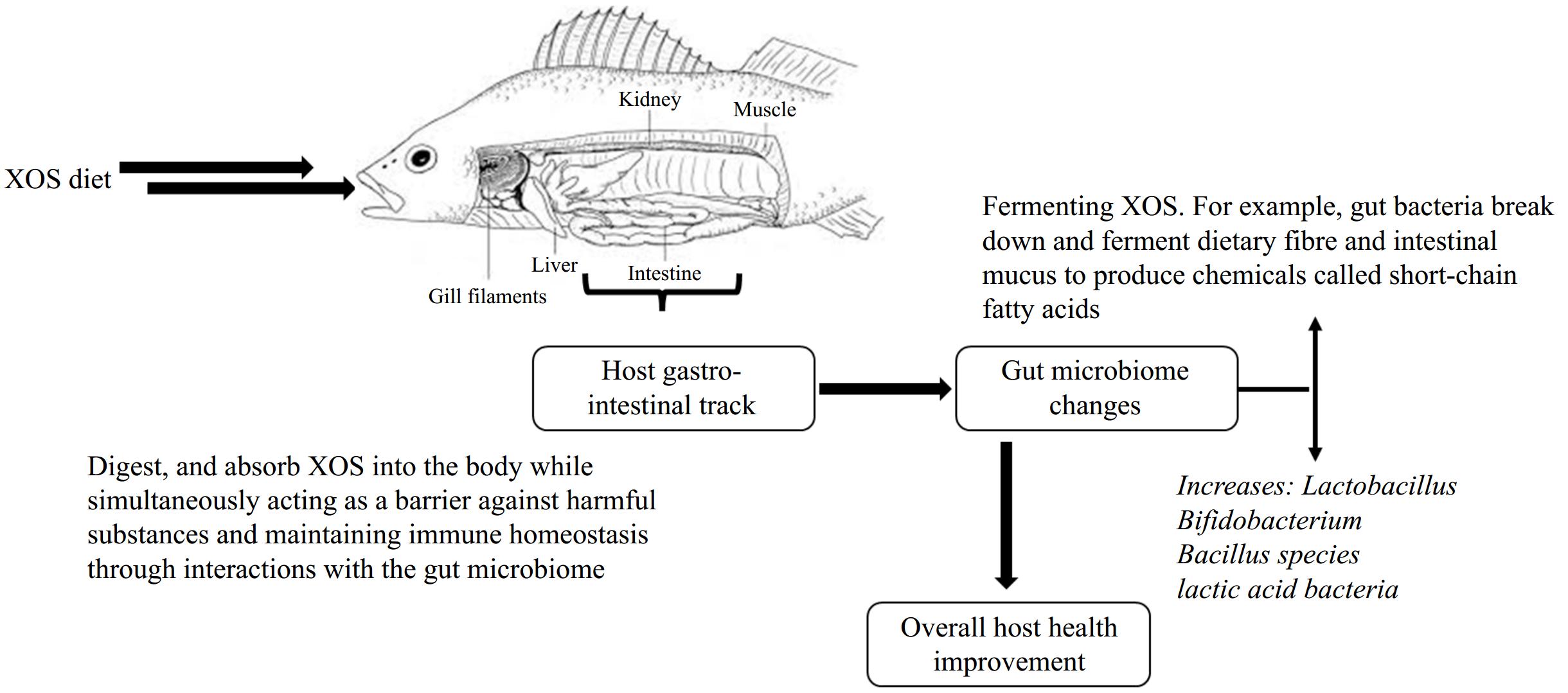

The ongoing interactions between hosts and gut bacteria are essential for regulating a variety of biological processes, including physiological responses and functions in humans, animals, and fish[52]. A balanced gut microbiota is crucial for preventing the proliferation and invasion of pathogenic bacteria, as it outcompetes them for nutrients and attachment sites while producing metabolites that inhibit their growth. This dynamic not only promotes growth performance and enhances innate immunity but also increases disease resistance in fish[53]. Thus, preserving gut microbiota balance is vital for the health and development of fish. Numerous studies have indicated that XOS supplementation significantly modifies gut microbiota composition by increasing the prevalence of beneficial genera such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium (Fig. 5). This alteration enhances immune regulation, boosts antioxidant capabilities, and preserves gut morphology and barrier function in weaning piglets and broiler chickens. As a result, these effects contribute to improved growth performance in these animals[54−56]. Such findings underscore the critical role of prebiotics like XOS in optimizing animal health and productivity, illustrating the intricate relationship between diet, gut microbiota, and overall physiological function.

Figure 5.

An overview of XOS prebiotics from host gastrointestinal track to gut microbiome changes that lead to overall host health improvement in fish species.

In fish species, Poolsawat et al.[26] reported that there was no meaningful distinction observed between the XOS-fed group and the control group regarding the microbial community diversity index (Shannon) and richness metrics (ACE and Chao) in hybrid tilapia (O. niloticus × O. aureus). Nonetheless, the Simpson diversity index was significantly elevated in the groups receiving XOS. Furthermore, studies conducted by Hoseinifar et al.[56], Guerreiro et al.[48], Poolsawat et al.[26], and Sun et al.[24] indicate that XOS helps reduce the relative abundance of adhering heterotrophic bacteria and pathogenic bacteria. In research employing 16S rRNA gene sequencing, juvenile Siberian sturgeons (Acipenser baerii) fed XOS diets exhibited an increase in Firmicutes, while the levels of Fusobacteria decreased[57]. The abundance of Proteobacteria, however, remained relatively stable when compared to the control group. Additionally, specific species, including Aeromonas spp., Rhodobacter spp., Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, and Cetobacterium somerae, showed significant reductions. In contrast, other species such as C. beijerinckii, Clostridium colicanis, C. baratii, Candidatus arthromitus, and Lactococcus raffinolactis. Eubacterium budayi, L. lactis, and L. aviaries displayed notable increases in abundance[57,58]. Notably, the relative abundance of L. lactis did not differ significantly between the groups fed XOS and the control groups [57,58]. Similarly, Guerreiro et al.[48] observed that the inclusion of XOS in the diet increased the Margalef species richness index in European sea bass, though it did not have a significant impact on the Shannon diversity index.

Despite these observations, there is a limited number of studies investigating the impact of dietary XOS on the gut microbiome of different fish species. The gut microbiota in fish can differ significantly due to factors such as geographic location, diet, habitat, feeding habits, management practices, and the physiology of the digestive tract[52, 59]. Consequently, understanding the specific beneficial autochthonous gut flora of the specific fish species is crucial before the administration of XOS. Additionally, differences in the documented gut microbiota may result from the different methodologies used to evaluate microbial diversity and abundance. For example, Sun et al.[25] utilized culture-dependent methods to assess viable and probiotic counts between fish groups fed XOS and those on a control diet. Their findings indicated that XOS significantly decreased the numbers of E. coli and Aeromonas in the intestines of grass carp while promoting an increase in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium spp. However, this method may capture only a limited aspect of the entire microbial community, as it predominantly targets culturable bacteria.

Researchers found that the overall number of culturable viable intestinal bacteria was comparable in both the XOS-fed groups and the control group in a study on hybrid catfish (Pangasianodon gigas × P. hypophthalmus)[60]. However, the levels of autochthonous lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were significantly greater in the fish receiving the XOS diet compared to those on the control diet. Similarly, Hoseinifar et al.[9] found that XOS supplementation in Oscar fry (Astronotus ocellatus) and Caspian white fish (Rutilus frisii kutum) led to a notable increase in the total count of autochthonous heterotrophic gut bacteria and LAB. Additionally, Poolsawat et al.[26] reported that providing XOS to Nile tilapia resulted in an increase in LAB and Bacillus species while decreasing the abundance of E. coli. Another study found that an increase in Lactobacillus species was correlated with dietary XOS supplementation of 0.5% to 1%. This suggests that XOS could promote healthy gut microbiota or encourage the establishment of specific probiotic strains[28]. The inconsistent results observed across various studies regarding the impact of XOS can be attributed to administration methods used, concentrations, prebiotic fermentability, and most importantly, the unique microbiota and intestinal architecture present in the fish populations being investigated[18].

The baseline host microbiome can be significantly influenced by various factors, which can, in turn, affect the effectiveness and results of functional feed supplements. These factors include the aquatic habitat, fish species, and developmental stages used in the tests[61]. Moreover, the methodologies employed in microbiota investigations may also impact the results; for instance, culture-dependent approaches limit the evaluation to cultivable microbes. In contrast, non-culture techniques, including high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, have shown that the prebiotic effects of XOS can vary depending on the taxonomic level. Based on their 16S rRNA sequencing data, Guerreiro et al.[48] found no notable variations in the richness and diversity of the microbial community between the XOS-supplemented groups and the control group. To gain a deeper understanding of the impact of dietary XOS on fish gut microbiota, further research utilizing metagenomic and full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing techniques is essential. It is believed that XOS, like other prebiotics, may influence the composition role of the intestinal microbiome through indirect pathways, even though the exact mechanisms by which they exert prebiotic impacts on the intestinal microbiome of fish are not yet fully understood. Conversely, MOS appears to operate through an immediate process by binding to pathogenic bacteria and inhibiting their ability to colonize the mucosal epithelium. Therefore, further investigation is needed to clarify any potential direct impact of dietary XOS on the intestinal microbiome of fish.

Effect of dietary XOS on overall liver health in fish species

-

Liver activity in aquaculture refers to a fish's role in metabolism, detoxification, and nutrient storage[62]. Monitoring liver activity is crucial for assessing health and identifying potential environmental stressors or dietary issues. XOS has been shown to lower blood glucose and lipid levels, regulating metabolism and preventing liver diseases. However, the effectiveness of dietary supplementation with XOS in aquatic species remains limited.

Chen et al.[63] studied the effects of 1.0% XOS supplementation on the growth and glycolipid metabolism of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) fed a high-carbohydrate (HC) diet. The results showed that XOS supplementation improved liver glycogen content, and the expression of key enzymes involved in glucose transport and metabolism (such as GLUT2, glucokinase, pyruvate kinase, and others). It also decreased liver and muscle lipid contents, plasma triglycerides, total cholesterol, and glycated serum protein (GSP) levels. Overall, 1.0% XOS supplementation enhanced growth performance and glycolipid metabolism by promoting glucose transport, glycolysis, glycogenesis, and fatty acid β-oxidation while reducing gluconeogenesis and fatty acid biosynthesis.

Diet supplemented with HFD exhibited lower hepatic expressions of pparα, aco, cpt i, and cd36 and plasma HDL with the opposite seen in lpl, and plasma AST, ALT, TG, TC, LDL, and NEFA levels however, this effect was reversed with HFD + 10 g/kg XOS, in common carp after 56 d of feedings[17]. These results suggested that high-fat feeding could lead to the pathogenesis of various lipid disorders and impair fatty acid uptake but were reversed in feeding the XOS diet. Taken together, these results suggested that dietary supplementation of XOS can suppress lipid storage and steatosis in the liver of common carp fed HFD.

Four experimental diets were formulated for fish, similar to control diets (PPC; FMC), but with the addition of 1% short-chain fructo-oligosaccharides (scFOS) or 1% xylo-oligosaccharides (XOS), creating the diets (PPFOS, PPXOS, FMFOS, and FMXOS). The results showed that glucokinase activity was higher in fish fed the FMFOS and FMXOS diets compared to those fed the FMC diet. Fish on XOS-enriched diets exhibited lower lipogenic enzyme activities (malic enzyme, fatty acid synthetase, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) than other groups. Additionally, fish on FM diets had higher glycolytic and lipogenic enzyme activities, and lower gluconeogenic activity compared to those on PP diets. Overall, XOS reduced lipogenesis and improved growth in fish fed PP diets while increasing glycolytic activity in FM diet-fed fish. XOS demonstrated potential as an effective prebiotic for European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax)[64]. Zhang et al.[20] also reported a significant reduction in TG content with no changes seen in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) in grass carp fed an XOS diet. In a study on rohu (Labeo rohita), the lowest total cholesterol was found in fish fed a 1% XOS-supplemented diet at 75% RPC levels. However, the serum activities of ALT and AST, as well as plasma levels of triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) showed no significant differences across the treatments[30].

-

The effects of dietary XOS in fish can vary significantly depending on several factors, including whether the fish are cold-water or warm-water species, as well as whether they have scales or are scaleless. These distinctions are important because they influence the digestive physiology, gut microbiota, and overall response to dietary changes.

Warm-water fish vs cold-water fish

-

Warm-water fish (e.g., tilapia, catfish, and carp), thriving in higher temperatures, have more efficient digestive systems suited to active microbial activity, allowing XOS to enhance gut health by stimulating beneficial bacteria (e.g., Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium), leading to improved nutrient absorption, growth, and feed conversion[65]. Additionally, the immune-boosting properties of XOS may offer better disease resistance and reduce antibiotic reliance. In contrast, cold-water fish (e.g., salmon, trout, and cod) experience slower metabolism, digestion, and lower gut microbiota activity, making XOS's prebiotic effects less pronounced. While XOS can still improve gut function and feed efficiency, especially in plant-based diets, its benefits are more moderate in cold-water species due to reduced microbial activity[66]. Thus, warm-water fish are likely to benefit more from XOS supplementation due to the more active microbial environment at higher temperatures.

Scaly fish vs scaleless fish

-

Scaly fish (e.g., tilapia, carp, and salmon), with their protective outer layer of scales, benefit from enhanced gut health and immune function through XOS supplementation. The scales offer physical protection and support a stronger gut flora, which XOS can enhance by boosting good bacteria. This improves food absorption and digestive effectiveness[67]. Furthermore, especially in high-density aquaculture environments, XOS can improve gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), promoting disease resistance. Scaleless fish, such as catfish and eels, are more dependent on their gut microbiota for pathogen defense due to their delicate skin and lack of external protection. In contrast, fish scales provide a protective barrier and contribute to a healthier gut microbiota, which XOS can further enhance by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria[68]. This leads to improved nutrient absorption, digestive efficiency, and stronger disease resistance through the boosting of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), especially in high-density aquaculture systems[69]. XOS supplementation offers significant benefits to scaleless species by improving immune function and supporting overall health. As a result, scaleless fish experience greater improvements in gut health and immune function from XOS, while scaly fish benefit to a lesser extent due to their natural physical protection.

-

Various literature suggests that XOS can improve the health, growth, and immune system of aquatic species. While the short-term growth benefits of XOS supplementation are well-established, longer-term research is needed to fully understand its effects on reproductive health, sustainability, and overall performance. XOS has great potential to increase aquaculture productivity by enhancing gut health and reducing disease risks, but more long-term studies are necessary to confirm its sustained benefits[70]. Although there is limited information available for species such as mollusks or cold-water fish, current literature indicates that XOS is most beneficial for tilapia, shrimp, and salmon. Due to their gut microbiota profiles, tropical fish and shrimp may benefit the most from XOS supplementation, but further research is needed to assess its effects on a wider range of aquatic organisms, including those with different feeding habits or in colder climates.

Although XOS can enhance gut health and reduce the need for antibiotics, its cost remains an issue, and more research is needed to determine whether it is economically feasible for large-scale use. Before recommending XOS as a common solution in aquafeeds, cost-effectiveness comparisons with other additives or alternative approaches, such as improved feed formulations or probiotic supplementation, should be conducted. A deeper understanding of the most effective dosages, potential risks, and sustainable usage patterns is necessary to make XOS a viable component of aquafeeds on a large scale. Lastly, future research should focus on long-term studies on the effects of XOS supplementation on reproduction, disease resistance, and overall survival rates, as well as studies on a wider range of species with different feeding habits or living conditions. Economic assessments for large-scale implementation and environmental impact evaluations are also essential to ensure that XOS remains sustainable over the long term, despite its optimal dosage varying depending on species and environmental conditions.

-

In several fish species, dietary XOS have proven to provide positive benefits; however, conflicting results have also been reported in the literature. The noted benefits include enhanced innate immunity, improved disease resistance, modulation of intestinal gene expression, increased intestinal barrier integrity, balanced intestinal microbiota, and enhanced digestive capacity. Divergent outcomes among certain fish species may arise from variations in species, XOS characteristics, and the indigenous host microbiota. More comprehensive research employing modern techniques within a single fish species is necessary to elucidate the prebiotic effects of XOS on the antioxidant properties, immune system, anti-inflammatory, and gut microbiota, given the variability of the gut microbiome across distinct fish species. In addition, before selecting and administering XOS, a comprehensive and systematic study on the in vitro fermentability of probiotics or gut-resident host bacteria is necessary on distinct fish species, considering factors such as composition, source, and manufacturing techniques.

-

Not applicable.

This research was financially supported by the earmarked fund for Agriculture Research System of China (CARS-45-12).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: conception, writing – review & editing: Abasubong KP; writing – original draft: Jiang GZ, Liu WB, Li XF, Cao XF, Desouky EH. All authors examined the findings and gave their approval for the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Abasubong KP, Jiang G, Cao XF, Liu W, Li XF, et al. 2025. A significant role of dietary xylooligosaccharides prebiotics in aquatic species: progressive advances beyond growth - a review. Animal Advances 2: e007 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0006

A significant role of dietary xylooligosaccharides prebiotics in aquatic species: progressive advances beyond growth - a review

- Received: 27 November 2024

- Revised: 14 January 2025

- Accepted: 23 January 2025

- Published online: 07 March 2025

Abstract: Recently, increasing attention has been paid to the importance of a high-quality diet. Feed supplements such as prebiotics offer significant nutritional and health benefits. Among the various types of prebiotics, xylooligosaccharides (XOS) stand out because of their exceptional properties in preventing systemic disorders. XOS are among the prebiotics being investigated in fish diets; however, their effects and mechanisms of action have not been thoroughly assessed compared to other prebiotics. Several studies have indicated that dietary XOS can enhance fish health by promoting the growth of beneficial gut microbes, which improves the immune response and disease resistance in various fish species. Similar to all prebiotics, XOS work by selectively stimulating beneficial gut microbiota, which helps outcompete pathogens and generate metabolites that influence the immune responses of the host. Reports of improved immune responses in fish fed XOS may stem from the ability to recognize patterns or indirectly support beneficial gut bacteria, which may play immune-stimulating roles. The impact of dietary XOS on fish performance varies by species and by the specific structure of XOS. Nevertheless, further research is crucial to determine the optimal dosage and substitution levels required for immune responses, antioxidant properties, and gut health in different fish species. This review emphasizes the influence of XOS as a prebiotic on the immune function response, antioxidants, and disease resistance.

-

Key words:

- Xylooligosaccharides /

- Disease resistance /

- Antioxidant /

- Immune response /

- Fish species