-

Population growth is driving an increase in global meat production, necessitating the use of efficient animal husbandry techniques to ensure economic viability and provide nutritious, high-quality food products[1]. Roughages are important feeds for ruminants to provide the carbon skeleton of energy and amino acids for rumen microbes, maintain rumen health, and control feed intake through physical filling[2−5]. Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) is a premium legume feed characterized by high crude protein content, diverse growth-promoting elements, and superior digestibility, rendering it a globally favored forage option[4,6]. The production of alfalfa in China is insufficient to meet animal husbandry needs, leading to an increase in imported alfalfa and a decline in industry profits[7,8]. Thus, it is important to seek alternative roughage for alfalfa to meet the demand and reduce the feed costs in the ruminant industry[9,10].

Yellow sweet clover, also known as Melilotus Officinalis L., is extensively utilized as a forage crop worldwide[11]. According to Al Sherif[12], these species evolved to withstand adverse conditions like saltiness, cold, and drought. Like alfalfa and other clovers, yellow sweet clover is a legume with a relative crude protein (CP) content (about 16%–25% DM), according to Çaçan et al.[13]. This plant is a good source of metabolizable energy for ruminants, with approximately 10 MJ/kg DM[11] because it digests well. According to Cornara et al.[14], legumes are well-known for their tranquilizer, diuretic, spasmolytic, antibacterial, and antiedematous characteristics.

Because of the coumarin material, melilotus species—which include sweet yellow clover—have been unable to be extensively utilized to produce fodder. Research has been done to lower the plant's coumarin content and utilize it as regular roughage[15]. While in flower, all Melilotus species have a unique, sweet scent that gets more aromatic and pleasant as they dry. Its coumarins are responsible for the distinctively sweet smell[16]. Mold fungus contamination in forage and silage products can occur during harvesting, transportation, or storage. Improper postharvest handling can cause spoilage. The fungus won't be able to grow and discharge its metabolites into the environment if the DM value falls below 14% throughout the forage drying phase[17].

Silage-making of sweet clover can prevent coumarin to dicoumarol conversion, resulting in high-quality silage[18,19]. Sweet clover feeding inhibits the mold fungus's ability to convert coumarin to dicoumarol. However, silage production can stop if the covering fermentation procedure is completed quickly[11]. Additionally, the yellow sweet clover herbage, rich in protein, energy, and alpha-linolenic acid, has similar in vitro digestibility across different phenological stages, making them valuable for producers[20].

The objective of this study was to investigate the effects on Hu sheep when they consume M. albus instead of alfalfa hay. Specifically, we aimed to examine how this dietary change impacts growth performance, the bacterial community, and carcass characteristics. The findings of this study will enhance our understanding of the microbial response to M. albus and promote its use in ruminants, helping to address the shortage of alfalfa.

-

Twenty healthy male Hu sheep weighing 30 ± 3.30 kg at four months were chosen and purchased from Jiangsu Yancheng Shuogi Agricultural Development (Jiangsu, China). The brucella test on Hu sheep was negative. Each sheep received experimental diets that were fully mixed in a 5:5 ratio of concentrates to roughage, and the experimental diets were prepared based on the specified guidelines of the 'Feeding Standard for Meat Sheep' (NY/T816-2004) based on the principle of nutritional balance. The feed components and chemical analyses of the trial diets are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Dietary composition and nutrient composition (dry matter basis).

Alfalfa M. albus Nutrient composition Corn 29.85 20.70 Alfalfa 30.00 0 M. albus 0 30.00 Wheat straw 20.00 20.00 Wheat bran 5.00 7.30 Soybean meal 9.50 9.20 Premix 2.00 2.00 DCP 1.15 3.50 Zeolite 0.50 2.69 Salt 1.00 1.00 CGM 0.00 2.61 Baking soda 2.00 2.00 Total 100 100 Nutrient composition ME (MJ/kg) 8.53 8.59 CP (%) 14.13 14.24 NDF (%) 32.43 32.14 ADF (%) 49.46 41.59 Calcium (%) 1.19 2.53 Phosphorus (%) 0.52 1.53 * Each kg of premix contains vit. A; 150−600 KIU, vit. D2; 30−100 KIU, vit. E; 600 IU, Vit. B; 12,000 g, vit. B; 225 mg, vit. B 625 mg, vit. B 1,230 g, niacinamide 100 mg, Manganese 1.0−3.6 g, vit. B; 1,230 g. Zinc 1.0-3.6 g, copper 0.1−0.8 g, iron 3.0−18.0 g, Selenium 5.0−12.0 mg, cobalt 3.0−50.0 mg, iodine 1.0−250.0 mg, total phosphorus 1.0%−5.0%, calcium 3.0%−25.0%, sodium chloride 6.0%−30.0%. * DCP, dibasic calcium phosphate; CGM, corn gluten meal; ME, metabolic energy; CP, crude protein; NDF, neutral detergent fiber; ADF, acid detergent fiber. Animal experiments were carried out at the Animal Testing Center of Nanjing Agricultural University. Before purchasing the test animals, the animal house was thoroughly cleaned and disinfected. Each experimental animal was housed in a cage measuring 1.0 × 1.2 m. The animals received their meals twice daily, at 5:00 p.m. and 8:00 a.m., when they were free to eat and drink.

Experimental design

-

Twenty sheep were weighed and randomly assigned to two experimental groups (each group of 10 sheep). The first group was the control group, fed concentrate and alfalfa hay. The second group was given concentrate mixed with M. albus. During the pre-feeding phase, seven days were dedicated, followed by 80 d during the formal feeding phase.

Measurements

Nutrient determination of forage

-

The diet samples were baked to constant weight at 65 °C, crushed, and screened with 40-mesh mesh, and stored in a ziplock bag for testing. The dry matter content was determined by the method of Mao et al.[21]. Dietary crude protein content was determined by the Kjeldahl nitrogen determination method, according to Krishnamoorthy et al.[22]. The crude fiber content was determined using the ANKOM 200i fiber analyzer (ANKOM, Germany) with reference to Van Soest et al.[23].

Growth performance

-

During the 80-d trial period, all the sheep were weighed in the morning before being fed. The weight recorded on the first day was taken as the initial weight, and the weight recorded on the 80th day was taken as the final weight. By keeping track of the body weight (BW) and feed intake (FI) of sheep, dry matter intake (DMI), average daily gain (ADG), and feed/gain weight ratio (F/G) were computed. Calculation formula: DMI = (Average daily supplement − Average daily surplus) × Dry matter content of feed; ADG = (Average final weight minus initial weight) / 80; F/G = DMI / ADG.

Carcass traits

-

Following the feeding trial, the sheep were killed using electric shock, followed by bloodletting and slaughter. The performance of the slaughter, as well as the development indexes of tissues and organs, are detected. Before the slaughter, the sheep were fasted for 16 h, and their live weight noted as the live weight before slaughter (LWBS). After removing the fur, head, hoofs, and viscera, the weight is recorded as the carcass weight, and the slaughter ratio is calculated. The liver, colon, and jejunum are then separated, and the weight of each organ is calculated as a proportion of the LWBS (organ index). Calculation formula: Slaughter ratio (%) = 100 × (Carcass weight / LWBS); Organ index (%) = 100 × Organ weight / Final body weight.

Apparent digestibility determination

-

The trial involved measuring feed amounts five days before feeding; the feed intake was noted, and the excretion amount of each sheep was collected twice a day (08:00 and 17:00) by the method of total manure collection after mixing 10% of the total faeces to create a sample, which was then stored in a zip-lock bag. The faeces samples were collected continuously for five days with 10% diluted sulfuric acid and 10 mL nitrogen fixation added to every 100 g of fresh faeces. All faecal samples of each sheep were mixed separately and frozen at −20 °C. After the digestion tests, the diets were crushed and filtered through a 40-mesh screen to determine the content of conventional nutrients. The formula is as follows: Apparent digestibility of nutrients = (Nutrient content in the diet at the amount of a solar eclipse) / (Nutrient content in the diet at the amount of a solar eclipse) × 100.

Rumen fermentation parameters and rumen epithelial tissue

-

Rumen fluid was collected on the 80th day of the trial from the mouths of 20 experimental animals before morning feeding; after filtering the chyme with four layers of gauze, the rumen fluid was obtained, then divided into 10 mL centrifuge tubes for storage in liquid nitrogen, and then transferred to −80 °C for storage.

A portable pH (Mettler Toledo, Sweden) meter determined the rumen fluid pH level. The pH value of the extract was determined using a portable pH meter. Volatile fatty acids, such as acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid, were analyzed using a Shimadzu high-performance gas chromatograph (GC-2014 AFsc). To prepare the sample, 1 mL of thawed extract was mixed with 0.2 mL of a 25% metaphosphoric acid and crotonic acid solution (using the internal standard method, where every 100 mL of the solution contains 0.6464 g of crotonic acid). This mixture was swirled and then placed in a refrigerator at −20 °C overnight. Before analysis, the samples were thawed and centrifuged at 4 °C and 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was then filtered using a 0.22 µm water-phase needle filter and was prepared for analysis with the gas chromatograph. The measuring conditions were as follows: column box temperature at 135 °C, inlet temperature at 200 °C, and flame ionization detector (FID) temperature at 200 °C. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas at a pressure of 0.06 MPa, according to Jin et al.[24].

According to Broderick's phenol-sodium hypochlorite colourimetric method, the concentration of ammonia nitrogen in a sample can be determined as follows: First, take 1 mL of the thawed extract and centrifuge it at 4 °C for 10 min at 4,000 rpm. Then, transfer 0.2 mL of the supernatant into a separate container, and add 0.8 mL of hydrochloric acid with a concentration of 0.2 mmol/L. Swirl the mixture to ensure it is well-mixed, and then add the prepared colour-developing solution for a full reaction. Simultaneously, it prepares standards with different concentration gradients to create standard curves. The absorbance values of both the samples and the standard solutions are measured at a wavelength of 700 nm using an enzyme analyzer. The concentration of ammonia nitrogen in the samples is calculated based on the formula derived from the standard curve. Additionally, a lactic acid kit (A019-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) is used to determine the concentration of lactic acid in the sample.

To obtain rumen epithelium, empty the rumen, rinse the inner wall twice and clip a 5 cm × 5 cm piece of tissue. Store in a centrifuge tube for determining rumen epithelial papillae indicators. Measure the structure of rumen papillae using an optical microscope. Randomly clip three pieces and count the surface papillae. The study randomly selected five rumen papillae from 1 cm × 1 cm rumen epithelial tissue and measured their length and width. The tissue was stained and morphologically observed under an optical microscope. Histomorphology was analyzed by blind inspection, and cell layer data was analyzed using Image-Pro Plus software. The thickness of the cuticle, granular layer, spinous process, and basal layer were measured. The slices were photographed and recorded.

Extraction of rumen microbial DNA

-

The following components were used to build the RT qPCR reaction system: 10 μL SYBR GREEN, 0.4 μL ROX, 0.4 μL primer F, 0.4 μL primer R, 6.8 μL distilled water, and 2 μL template. This construction approach was as suggested by Shen et al.[25]. The 16rRNA genes of bacteria, protozoa, fungi, and archaea were utilized as templates to create quantitative standard curves. The total number of microorganisms in the rumen fluid was quantitatively analyzed using real-time PCR.

High-throughput rumen bacterial sequencing and analysis

-

All sample sequencing processes are carried out in BGI. The specific processes are as follows: after passing the nucleic acid quality inspection, we took qualified samples and performed PCR amplification on them. The high-throughput sequencing primers are 515-F (5"-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3") and 806-R (5"-GGACTACCVGGGTATCTAAT-3"), which were sequenced with a fragment length of 291 bp. The amplified products were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads, followed by library quality tests, and qualified libraries were sequenced using the HiSeq platform. After the original results were obtained, the primer sequence and barcode were removed using cutadaptv2.6 software, and then QIIME2 was used for quality filtering, double-ended splicing, and decimalization. Finally, QIIME2 software was used to generate bacterial amplicon sequence variation (ASV) at a 100% similarity level.

Alpha diversity analysis was performed using QIIME2, including ACE, Shannon, Simpson index, and a data analysis depth of 44,000 bases. The similarity or difference in microbial community composition was demonstrated by the principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) chart. The abundance histogram at the microbial phylum and genus level was drawn by GraphPad Prism8.0 and the species diversity of rumen bacteria between groups was analyzed by LEfSe. tax4fun was compared in the KEGG database to predict the function of rumen bacteria, and LEfSe was used to screen the different pathways. SPSS two-factor analysis of variance was used to analyze the significance of rumen fermentation parameters. All data were expressed as mean ± standard error, and p < 0.05 was marked as a significant difference.

Measurement of coumarin in rumen fluid

-

Two ml of rumen fluid were deposited in a glass bottle, freeze-dried for 48 h, and subsequently retrieved for utilization. The freeze-dried powder was mixed with an equal volume of methanol and then passed through a 0.22 m filter membrane to be measured. With a ZorbaxSB-Aq column and a 1220A Infinity liquid chromatograph (Agilent, USA), the following parameters were used to measure coumarin: sample size of 20 uL, identification wavelength of 280 nm, column temperature of 35 °C, and mobile phase ratio of methanol to water (65:35). Beijing Solaibao Technology Co., Ltd. (China) supplied the coumarin standard, and a standard liquid with varying concentrations was made ready for the standard curve's drawing.

Meat quality assessment

-

At the end of the study, the sheep were killed using electric shock, and muscle samples of longissimus dorsi muscle, leg muscle, gluteus media muscle, and lateral femoral muscle were taken from each animal for meat quality determination. A pH meter was used to determine the pH of meat samples after slaughter.

Three meat samples were cut perpendicular to muscle fibers using a circular sampler. The initial weight was determined, then 18 layers of filter paper were placed, pressurized to 35 kg, and the weight was measured using an analytical balance with a 0.001 g accuracy. Calculation formula: Meat water holding capacity assessment = (Before weight − After weight) / Before weight × 100%. The meat sample was cut into strips, warmed in a water bath, and then cooled to measure shear force using a muscle tenderness meter after cooling. Meat samples' brightness (L*), redness (a*), and yellowness (b*) were measured using a color difference meter, with each part measured in three parts with a deviation of less than 5%.

To measure the FA profile, samples were collected by taking samples according to GBT 9695[25]. We weighed 0.5 g of dried and crushed meat, placed it in a 15 mL stopper test tube, added 4 mL of isooctane, shook and mixed it in a whirlpool mixer for 30 s, and shocked it in a constant temperature shaking bed at 37 °C overnight. 4 mL of 1.5 moL/L NaOH methanol solution was added and fully homogenized in a homogenizer until the tissue was completely broken; an ultrasonic cleaning machine was used for ultrasonic extraction for 15 min; then 4 mL of 1.5 mol/L H₂SO₄ methanol solution added to the vortex mix; and then an ultrasonic cleaning machine used for ultrasonic extraction for 12 min. 2 mL of n-hexane was then added, vortexed for 30 s, 5 mL of ultra-pure water then added, and let to stand until the liquid level was stratified. An appropriate amount of supernatant was absorbed with a syringe and injected into a chromatograph bottle through a 0.45 μL microporous filter membrane. Thirty seven kinds of fatty acids and 37 kinds of fatty acid methyl ester standards (Sigma, USA) were determined in the Agilent gas chromatograph 8890. Agilent DB-FastFAME was used for gas chromatography. The parameters were as follows: injector temperature 220 °C, detector temperature 280 °C. The detection process uses automatic sampling. After all the detection was completed, the data was copied and analyzed by Chromeleon 7 software. The table converts the detected fatty acid data to percentage values, representing the amount of fatty acid milligrams per 100 g of muscle.

Statistical analysis

-

The average variations were assessed using Duncan's multiple-range test after analyzing the data with the (SPSS. v 27) SPSS General Linear Model procedure. Using QIIME2, alpha diversity analysis was carried out, incorporating 44,000 bases of data analysis dominance, chao1, richness, and Shannon indexes. The Bray-Curtis NMDS analysis chart showed how the makeup of the microbial communities differed and how they were similar.

GraphPad Prism8.0 was used to create the abundance histogram at the microbial species and genus level, and LEfSe was used to assess the species diversity of rumen bacteria across groups. To anticipate the role of rumen bacteria, tax4fun was compared in the KEGG database, and LEfSe was utilized to screen the various pathways. Rumen fermentation characteristics were analyzed for significance using SPSS two-factor analysis of variance. p < 0.05 was designated a significant difference, and all data were presented as mean ± standard error.

-

Table 2 presents the effects of feeding M. albus on final body weight (FBW), body weight gain (BWG), feed intake (FI), and feed-to-gain ratio (F/G). The average initial body weight of the five-week-old sheep across all treatment groups was 30 ± 3.30 kg, indicating that the animals were randomly distributed among the experimental groups. When Hu sheep diets were compared to those with M. albus, especially when alfalfa hay was added, ANOVA results showed significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) in FBW, BWG, and F/G. These findings indicate that M. albus negatively impacted these performance parameters. In contrast, sheep-fed diets, including alfalfa hay, achieved the highest FBW, BWG, and F/G values compared to those receiving M. albus.

Table 2. Effects of feeding M. albus on the growth performance and apparent digestible energy of Hu sheep.

Item Group p value Alfalfa M. albus Initial body weight (kg) 27.70 ± 1.10 28.26 ± 1.08 0.719 Final body weight (kg) 40.78 ± 0.75 38.59 ± 0.65 0.042 Body weight gain (kg) 13.08 ± 0.45 10.33 ± 0.78 0.009 ADWG (kg/d) 0.16 ± 0.02 0.13 ± 0.03 0.009 DMI (kg) 1.12 ± 0.02 1.06 ± 0.02 0.044 Total feed intake (kg) 104.48 ± 7.03 98.88 ± 4.36 0.039 F/G 6.93 ± 0.27 8.59 ± 0.60 0.028 Dry matter (%) 0.75 ± 0.03 0.73 ± 0.04 0.160 Crude ash (%) 0.84 ± 0.04 0.81 ± 0.077 0.263 Crude protein (%) 0.74 ± 0.02 0.70 ± 0.02 0.002 NDF (%) 0.52 ± 0.04 0.41 ± 0.05 0.001 ADF (%) 0.55 ± 0.03 0.41 ± 0.03 0.001 ADWG = average daily weight gain, DMI = dry matter intake, F/G = DMI/ADWG, NDF = Neutral detergent fiber, ADF = Acid detergent fiber. Apparent digestibility

-

The results in Table 2 indicate the effect of feeding M. albus on apparent digestible (DM, CA, CP, NDF, and ADF). No substantial variations existed between M. albus and alfalfa hay in dry matter or crude ash. In contrast to the sheep fed M. albus, a substantial difference (p ≤ 0.05) was observed in the amount of raw protein for the alfalfa hay-fed sheep. A substantial variance (p ≤ 0.001) was observed in the neutral and acid detergent fibers when comparing the sheep-fed alfalfa straw to the sheep-fed M. albus.

Feed cost-effectiveness

-

The different treatments' feed cost-effectiveness (total feed cost/BWG) is presented in Table 3. The current investigation shows no statistically significant differences between M. albus and alfalfa hay in feed cost-effectiveness. Despite the low cost of the roughage and total feed cost used with M. albus compared to alfalfa hay, the effectiveness of nutrition did not have notable differences due to the weight gain of animals fed the alfalfa hay compared to those fed M. albus. It was also noticed that the relative profits decreased in M. albus, which were 86.48% compared to alfalfa 100%.

Table 3. Input/output analysis and economic efficiency of experimental groups.

Item Groups Alfalfa M. albus Total gain (kg) 13.08 10.33 Total feed intake (kg) 104 98 Feed cost (RMB)* 416.00 310.66 Gain price (RMB)** 654.00 516.50 Net revenue*** 238.00 205.84 Relative profit (%)**** 100 86.48 * = Total feed intake × price (the price of 1 kg diet was 4.0 RMB / alfalfa, and 3.17 RMB / M. albus). ** = Total gain × 50 (1 kg 50 RMB). *** = Gain price – Feed cost. **** = Net revenue for treatment / Net revenue for control × 100, according to Kamal et al.[67]. Carcass traits

-

Table 4 illustrates the impact of M. albus on the traits of the carcass. According to the analysis of variance, no statistically substantial variations were found among the treatments in terms of the jejunum proportion, jejunum weight, colon proportion, and jejunum weight. Specifically, carcass weight, dressing percentage, liver percentage, and liver weight were substantially (p ≤ 0.05) better in animals fed alfalfa hay diets than in M. albus.

Table 4. Effects of feeding M. albus on slaughter performance of Hu sheep.

Item Group p value Alfalfa M. albus Final body weight (kg) 40.78 ± 0.75 38.59 ± 0.65 0.042 Carcass weight (kg) 21.02 ± 0.46 18.62 ± 0.32 0.001 Dressing percentage* (%) 42.05 ± 0.04 39.19 ± 0.02 0.029 Liver proportion (%) 1.54 ± 0.03 1.38 ± 0.02 0.020 Liver weight (kg) 0.63 ± 0.01 0.54 ± 0.01 0.001 Jejunum proportion (%) 2.90 ± 0.23 3.25 ± 0.14 0.232 Jejunum weight (kg) 1.19 ± 0.09 1.25 ± 0.06 0.602 Colon proportion (%) 2.64 ± 0.13 2.88 ± 0.08 0.144 Colon weight (kg) 1.09 ± 0.08 1.12 ± 0.05 0.763 Rumen empty proportion (%) 0.73 ± 0.02 0.64 ± 0.01 0.003 Rumen empty weight (kg) 1.78 ± 0.04 1.66 ± 0.01 0.065 * Dressing percentage (%) = Carcass weight / Final body weight. Rumen papillae and papillary tissue morphology

-

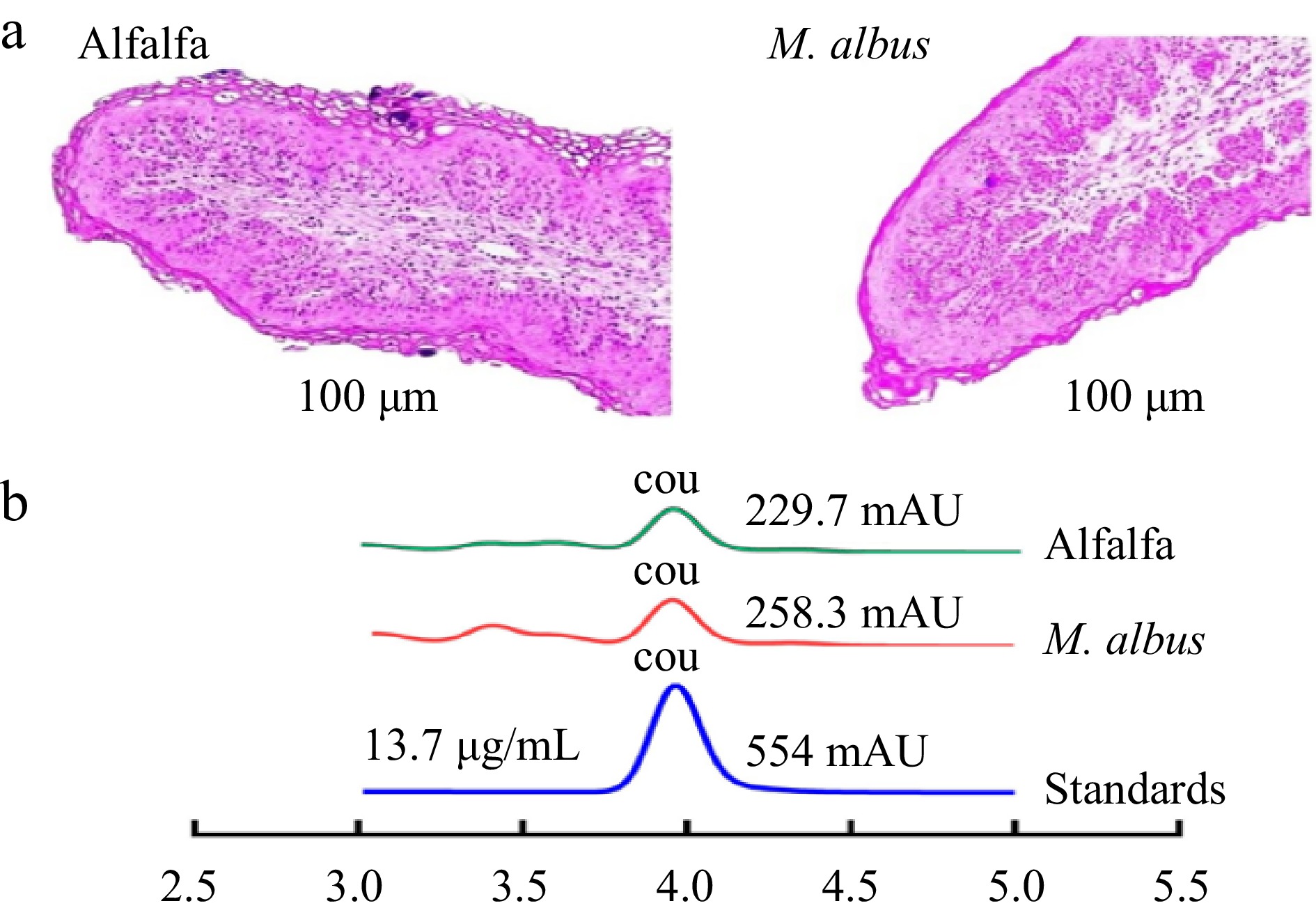

The effects of M. albus on papillae width and height, ruminal papillae, thickness, density, and total papillae surface are presented in Supplementary Table S1. According to optical microscope measurements, the current study did not find evidence of a significant impact of melilotus albus nutrition on papillae width or height, as noted in Supplementary Table S1 and Fig. 1a.

Figure 1.

(a) Tissue morphology of rumen epithelial papillae under optical microscope; (b) Peak coumarin in rumen fluid. (Peak coumarin at 4 min, COU: coumarin, Standard coumarin=13.7 µg/mL).

According to quantitative morphological examination, M. albus feeding wasn't shown to significantly influence the growth of the ruminal papillae (Supplementary Table S1). The rumen quickly adapted to alfalfa hay, as evidenced by a notable (p ≤ 0.001) increase in papillae's thickness, density, and total surface compared to sheep given M. albus.

Rumen fermentation

-

Supplementary Table S2 shows the impact of M. albus on rumen fermentation parameters. No apparent variations in pH, microbial protein, acetate, propionate, valerate, and acetate/propionate were observed between treatments, according to the ANOVA. However, NH3-N, total volatile fatty acid, and butyrate were substantially reduced (p ≤ 0.05) in the melilotus group compared to the alfalfa hay group. On the other hand, lactate, isobutyrate, and isovalerate were substantially (p ≤ 0.05) greater in the alfalfa hay group than in the M. albus group.

Coumarin measurement

-

Figure 1b demonstrates the effect of M. albus on the content of coumarin in rumen fluid. The content of coumarin in rumen fluid was measured. The peak area of the alfalfa hay and M. albus groups was the same, and the results showed that coumarin in rumen fluid was degraded.

Microbial abundance, composition, and communities

-

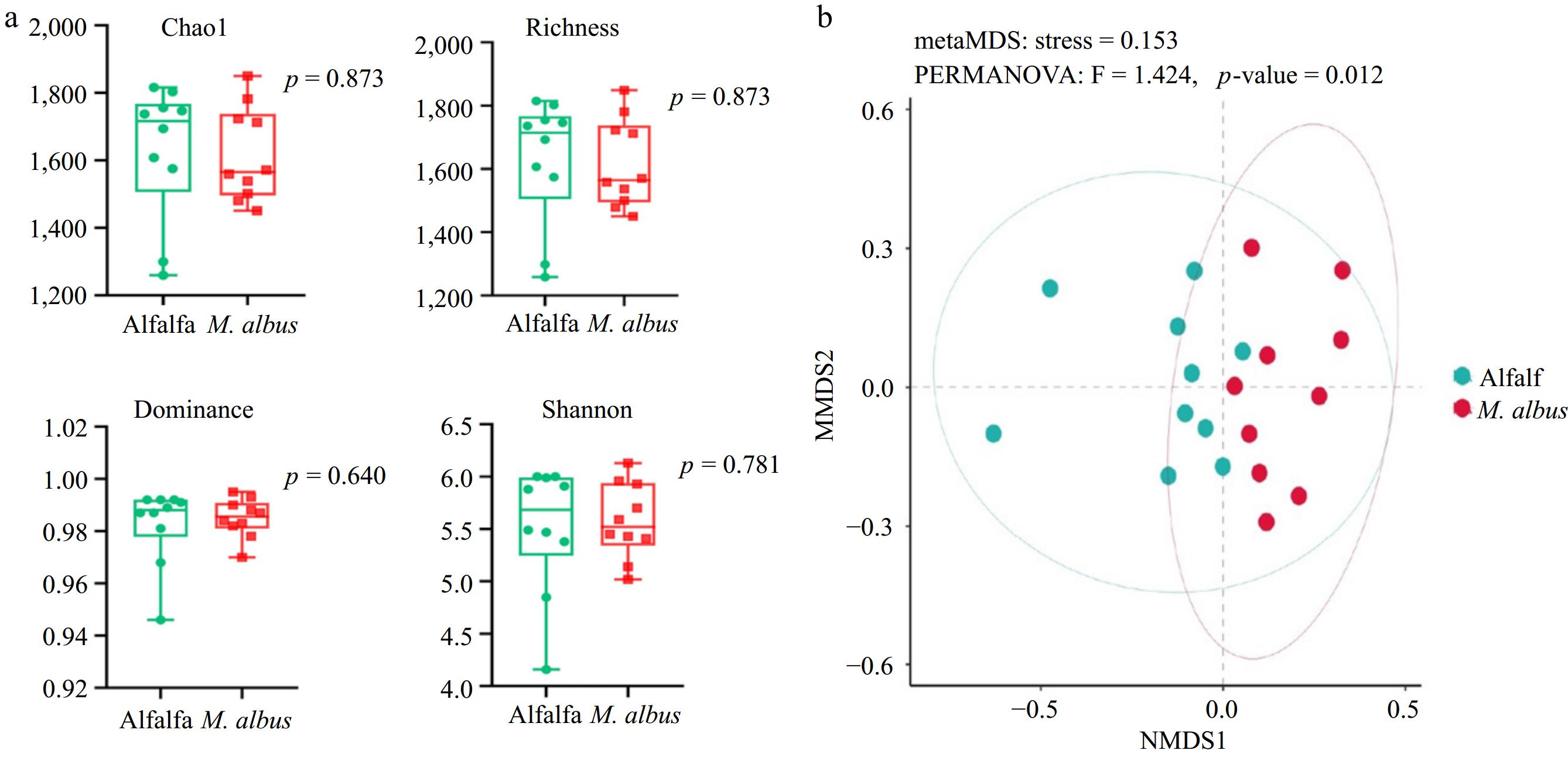

The impacts of feeding M. albus on the α diversity index of the rumen microbial communities of lake sheep are displayed in Fig. 2a. As the image illustrates, feeding M. albus did not significantly affect the alpha diversity index of rumen microbial communities (Chao1, richness, dominance, Shannon, p > 0.05). The distances between sample points in the graph represent the disparities between individuals or groups. The degree of resemblance increases with the proximity of the samples on the graph. As depicted in Fig. 2b, Bray-Curtis NMDS analysis based on Bray-Curtis distance revealed significant structural separation of rumen bacterial communities at the phylum and genus levels (p < 0.05) regarding β diversity.

Figure 2.

(a) Effects of feeding M. albus on alpha diversity of Hu sheep. (b) Bray-Curtis NMDS results of feeding M. albus on rumen microbial diversity of Hu sheep.

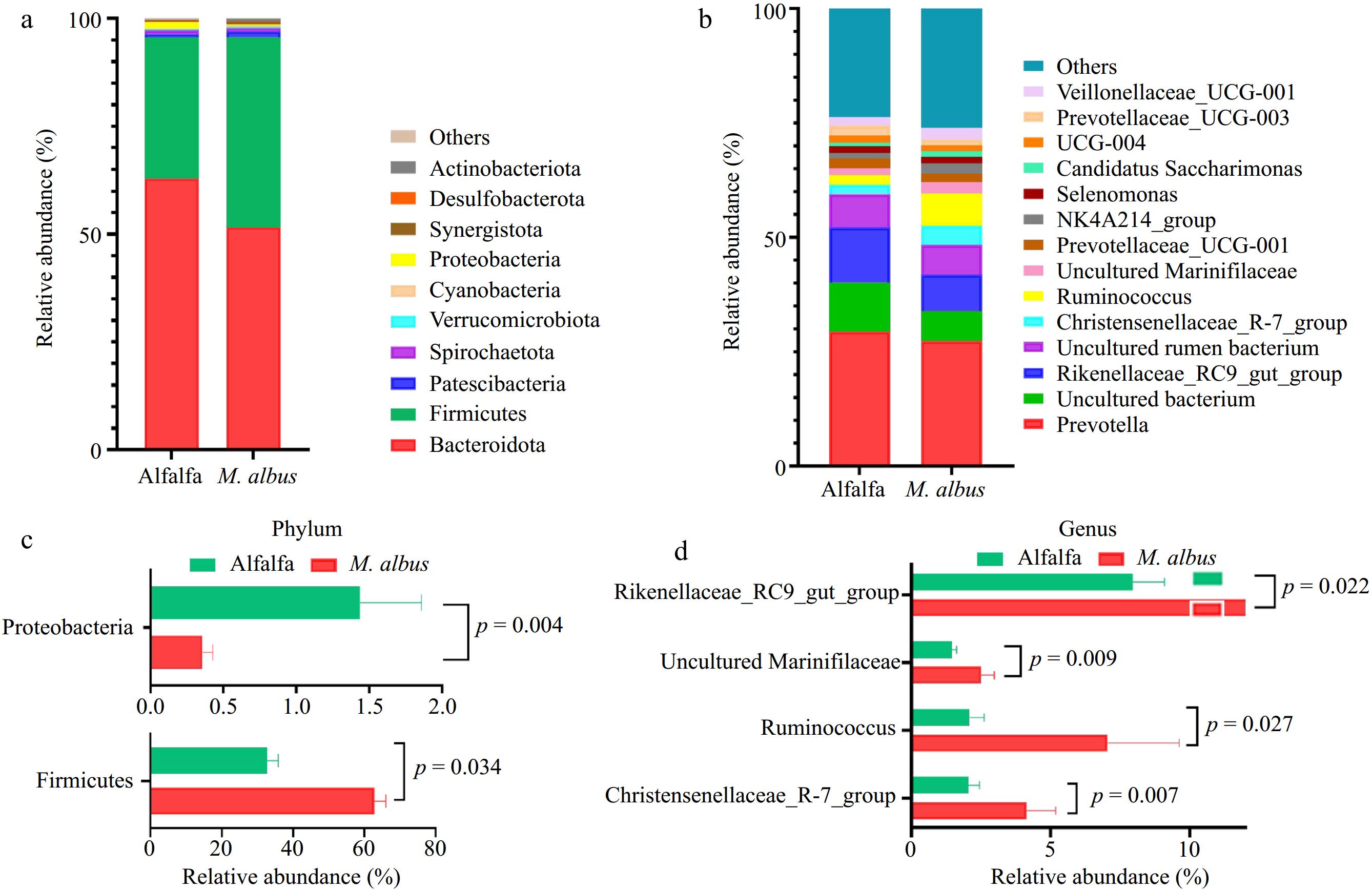

Figure 3a and b depicts the outcomes of Bacteroidota and Firmicutes, the predominant bacteria in the rumen at the door level. At the genus level, the dominant genera are Prevotella and Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group.

As shown in Fig. 3c, d, the LEfSe study of the rumen microbes of Hu sheep, ranging from the phylum level to the genus level. There were two distinct phyla and five distinct genera with LDA values larger than 3.5 compared to the alfalfa group. LEfSe analysis results showed that at the gate level, the relative abundance of Firmicutes in M. albus was significantly higher than that in alfalfa. In comparison, the relative abundance of Proteobacteria in group M. albus was significantly lower than that in alfalfa (p < 0.05). At the genus level, the relative abundance of Ruminococcus, Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut_group, Christensenellaceae_R-7_group, and uncultured Marinifilaceae in M. albus was significantly higher than alfalfa (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Microbial diversity analysis. (a) Relative abundance at the phylum level. (b) Relative abundance at the genus level. (c), (d) Relative abundance of differential bacterial genera analyzed by LEfSe.

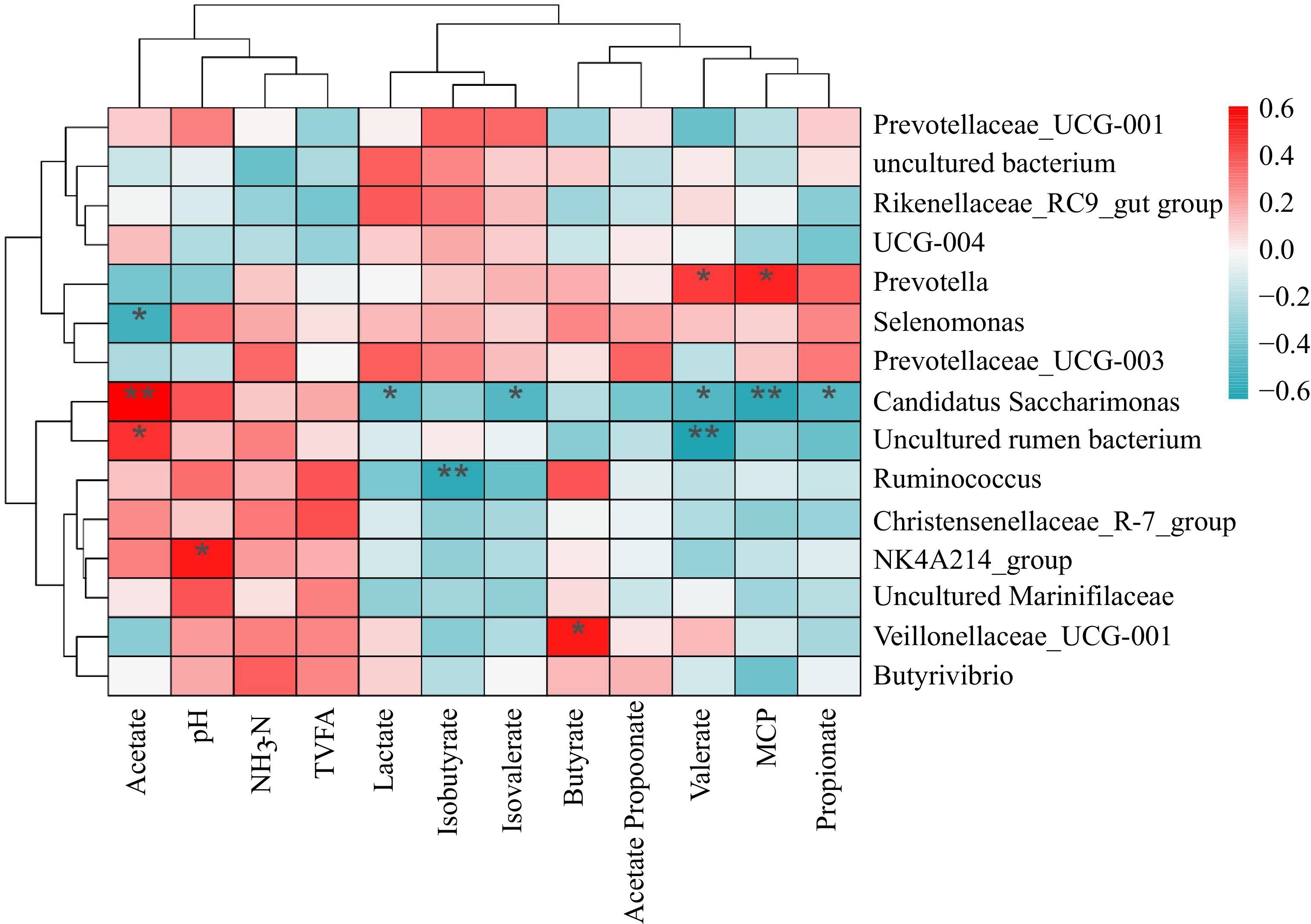

Heat maps were drawn based on the correlation between fermentation parameters and the relative abundance of the genus (> 1%) (Fig. 4). The results showed that Prevotella significantly correlates with microbial protein (MCP) and valerate. Candidatus Saccharimonas and uncultured rumen bacterium are significantly positively correlated with acetate. The NK4A214 group is significantly and positively correlated with pH.

Figure 4.

Heatmap of correlation between microbial genera and fermentation parameters. Note: Red represents positive correlation, blue represents negative correlation, * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01.

Meat quality

-

Supplementary Table S3 displays the impact of M. albus on the quality of lake mutton. Shear force was notably lower in alfalfa hay than melilotus in the longissimus dorsi. Still, the meat's pH, water-holding capacity, brightness, and yellowness showed little variation between the groups. In addition, M. albus produces less redness in meat than alfalfa hay. However, there wasn't any noticeable variation in most meat quality parameters between the sheep-fed alfalfa and the sheep-fed M. albus, except for shear force. Furthermore, there wasn't any apparent difference in the vastus lateralis muscle between the groups. Gluteus medius did not exhibit any statistically significant variations between treatments regarding pH, water-holding capacity, brightness, or meat redness. There were some substantial differences between the groups regarding shear force, brightness, and yellowness for the alfalfa treatment.

Table 5 presents the percentages of saturated fatty acids (SFA), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in the in vitro fermentation fluid of the sheep fed with M. albus and alfalfa hay. Our results found notable differences in the levels of SFA and MUFA between the two groups, although the percentages of PUFA and other fatty acids were similar.

Table 5. Effects of feeding M. albus on muscle fatty acids of Hu sheep.

Item Group p value Alfalfa M. albus SFA (%) C10:0 0.26 ± 0.05 0.24 ± 0.05 0.319 C12:0 0.30 ± 0.18 0.19 ± 0.04 0.090 C13:0 2.34 ± 0.40 2.10 ± 0.23 0.119 C14:0 4.68 ± 1.49 3.72 ± 1.06 0.113 C16:0 21.74 ± 2.32 22.27 ± 3.35 0.683 C18:0 23.34 ± 2.27 22.39 ± 2.74 0.410 MUFA (%) C14:1 0.77 ± 0.19 0.82 ± 0.12 0.440 C16:1 1.35 ± 0.49 1.67 ± 0.48 0.171 C18:1 C9 35.93 ± 2.13 37.89 ± 1.30 0.023 C20:1 0.31 ± 0.07 0.29 ± 0.09 0.585 PUFA (%) C18:2 n-6 7.72 ± 0.72 7.82 ± 0.43 0.741 C20:5 n-3 0.39 ± 0.02 0.39 ± 0.07 0.894 C20:4 n-6 0.86 ± 0.01 0.22 ± 0.08 0.001 SFA (%) 52.66 ± 2.23 50.90 ± 1.08 0.038 UFA (%) 47.34 ± 2.23 49.10 ± 1.07 0.043 MUFA (%) 38.36 ± 1.97 40.67 ± 1.60 0.004 PUFA (%) 24.08 ± 0.69 24.97 ± 0.73 0.142 SFA = saturated fatty acids, UFA = Unsaturated fatty acids, MUFA = monounsaturated fatty acids, PUFA = polyunsaturated fatty acids. -

Our research has shown that providing M. albus feed to Hu sheep did not improve their growth performance compared to the group that was given alfalfa hay. Their BWG and F/G indicated this. However, compared to alfalfa hay, the combination of inexpensive roughage and concentrate used with M. albus was superior. Therefore, due to its low cost and wide availability, M. albus is a good option.

These findings concur with those of Mouad et al.[26], who discovered no impact on the growth performance of young goats when M. officinalis is added to their diet. According to Bauman et al.[27], the FBW is considered a significant indicator of the weight and percentage of carcass characteristics. Also, adding varying amounts of sweet yellow clover extract to sheep's diets improved the biochemical makeup of their blood and increased the body's defense mechanisms. Sheep given 2.5 mg/kg of sweet yellow clover extract showed the best performance among all the groups, according to Ulrikh et al.[3]. Melilotus suaveolens L., a significant economic legume in China, has a higher saline-alkaline tolerance but is unsuitable for standalone livestock feed due to its high degradation rate; instead, it should be combined with other forages for feeding[28]. Masters et al.[29] found that coumarin levels do not significantly influence the Prima gland clover's feed intake, and its feeding value is comparable to that of the Dalkeith subterranean clover.

According to a study conducted by Habibi & Ghahtan[30], using 2% aloe vera, M. officinalis, and Oliveria decumbens can enhance growth performance and increase the shelf life of meat in Japanese quails. Additionally, a study by Hassan et al.[31]found that supplementing coumarin and sodium bentonite was effective in reducing toxicity caused by aflatoxin B1, and rabbits that were supplemented with coumarin showed better feed conversion and increased body weight gains, suggesting that coumarin is a more effective anti-toxigenic supplement. Also, Duskaev et al.[32] revealed that adding coumarin and coumarin + Bacillus cereus to the broiler diet improved growth rates and decreased feed consumption. Moreover, Al-Jebory et al.[33] demonstrated that adding aqueous extracts of Borage and Melilotus plants to drinking water for Lohmann Brown laying hens at a rate of 4 ml/L could improve some characteristics related to egg quality.

Sweet clover is widely utilized in conventional medicine due to its numerous beneficial effects, including antimicrobial, dermatological regeneration, hypotensive, antioxidant, and even neuro- and hepato-protective effects[34−36]. The plant's wide range of effects can be attributed to its various chemical compounds, such as phenolic acids, steroids, saponins, coumarins, volatile oils, and glycosides[36,37].

Our research found that in the M. albus treatment, there was no significant impact on any aspect of the carcass. This outcome is consistent with the discoveries of Mouad et al.[26], who found that M. officinalis did not significantly impact the carcass performance variables of young goats. According to El Otmani et al.[38], adding olive cake and cactus cladodes to native goat kids' diets did not negatively affect growth, carcass features, meat quality, or FA, indicating that feed could be a cost-effective substitute during drought or feed scarcity.

In contrast, Hamdi et al.[39] found that rangeland-fed lambs had enhanced sensory qualities and reduced fat content, while olive cakes did not affect their meat and carcasses. Pleşca-Manea et al.[40] showed that an extract of M. officinalis L. that contains 0.25% coumarin can reduce inflammation in male rabbits by stopping phagocyte activation and citrulline production. Also, Butler et al.[41] found that diets based on barley or alfalfa gave lambs similar daily gains, higher FBW, and thicker back fat.

Although alfalfa hay was more expensive than M. albus in terms of roughage and concentration used, our investigation revealed no appreciable variations in feed cost-effectiveness between the two. Mouad et al.[26] reported similar findings and proposed that breeders might consider using yellow sweet clover as a substitute to ensure a well-balanced diet throughout the year and reduce fattening expenses.

According to our research, there were few differences in the dry matter between M. albus and alfalfa hay. However, we found notable variations in the raw protein and neutral and acid detergent fibers in sheep-fed alfalfa hay. Litvinov et al.[42] found that M. officinalis helps regulate protein and dry matter disintegration in cow rumen by providing digestible protein. They recommend mowing green masses and preserving silage with benzoic acid, according to Webb et al.[43], dietary modifications may majorly affect the amount of ash. Additionally, Chen et al.[44] conducted an in vitro rumen fermentation experiment on three lines of M. offcinalis. They discovered that line 3 had higher NDF than CK-oGongnong, which could decrease microbial growth and NDS. However, variations in coumarin content may be responsible for higher gas production.

Based on our results, feeding alfalfa hay to sheep significantly alters their rumen by increasing its thickness, density, and surface area. However, feeding M. albus did not significantly impact the growth of ruminal papillae in a research project led by Ahmed et al.[45], the morphological changes in the rumen papillae of 24 sheep fed a combination of hay and concentrate diets were examined. Additionally, the papillae were greatly influenced by time and diet, with feeding for 4−6 weeks resulting in a significant change from small, tongue-shaped papillae to large, largely cornified, finger- and foliate-shaped papillae. Additionally, the morphometric analysis showed a rise in papilla length and number, with the total surface area of papillae doubling in sheep-fed concentrate. Furthermore, Alhidary et al.[46] showed that feeding alfalfa hay increased the rumen's structural capacity and contributed to the lambs' performance.

Wang et al.[47] indicate that particle size and VFA in low-quality fodder impact dairy cows' gene expression, cell proliferation, apoptosis, and nutrient absorption. Another study by Kyawt et al.[48] found that giving sheep bio-fermented feed considerably boosted the rumen papillae's height, width, and unit area, which could be related to the transport of nutrients through the ruminal wall. Additionally, Xu et al.[49] discovered that 50%–80% of the VFA in the rumen is absorbed and transported by the rumen epithelium and that the expression of transporters and the surface area of the epithelium have a strong correlation with the effectiveness of this transport.

Our investigation demonstrated no appreciable variations in pH, microbial protein, acetate, propionate, valerate, or acetate/propionate among treatments, in contrast to the significant reductions in NH3-N, total volatile fatty acid, butyrate, and lactate levels observed in alfalfa hay animals. Rumen microorganisms produce NH3-N from substrates, transforming them into MCP[50]. Compared to CK-MoGongnong, the level of NH3-N in Line 3 was significantly lower, but the concentration of MCP did not differ substantially[51]. Our findings indicate that the MCP has slightly increased. Rumen microbes may have produced greater MCP in the in vitro rumen by becoming more active because of the substrate's decreased coumarin content. The three primary forms of VFA are butyrate, propionate, and acetate[52]. Propionate proportions were substantially higher for Line 3, indicating that coumarin content reduction in M. officinalis might enhance rumen microbial fermentation and lead to higher MPC and potentially lower methane emissions. When comparing Line 3 to CK-MoGongnong, the concentration of isobutyrate and isovalerate, which are byproducts of amino acid breakdown, was much reduced[53]. Furthermore, Li et al.[54] reported that the microorganisms that degrade aflatoxin were screened using coumarin as a carbon source. There is conjecture that the rumen contains microorganisms capable of breaking down coumarin. The most prevalent species in the rumen is Prevotella, which primarily contributes to the metabolism of nitrogen and carbohydrates and makes a range of enzymes participating in the hemicellulose breakdown process[55].

Hassan et al.[31] found that rabbits fed on a diet contaminated with aflatoxin had a higher mean cecal pH and lower NH3-N, TVFA, and proportions. The reduced NH3-N and TVFA contents may result from reduced FI. However, adding sodium bentonite and coumarin reduced aflatoxin B1 residue concentrations, possibly due to DNA adducts and increased excretion, affecting groups with coumarin[56]. Additionally, Kintl et al.[57] found that white sweet clover and fodder mallow might be utilized to produce biogas. Still, because of their low biogas yields, legume silage cannot completely replace maize silage.

Our research shows rumen bacterial communities exhibit a considerable structural distinction at the phylum and genus levels when analyzed using the Bray-Curtis NMDS analysis. Feeding M. albus affects the diversity index α, but not the alpha. Zeng et al.[58] used the Illumina HiSeq sequencing platform to examine how adding oat hay affected the microbiota in the rumen of sheep by utilizing the Ace and Chao indices. He et al.[59] indicated that the rumen bacterial abundance is influenced by the type of roughage consumed; a higher oat hay content increases rumen bacterial abundance, while a bigger Shannon index value lowers the Simpson index value. Additionally, An et al.[60] found that higher roughage content in sheep's diet increases the diversity of rumen bacteria despite a lower Simpson index.

According to Chen et al.[51], lowering the coumarin level encourages microbial fermentation and the production of advantageous metabolites, and altering the coumarin content influences the rumen's predominant bacterial community. There are few studies on the microbial degradation of coumarin, but Li et al.[54] used coumarin as a carbon source to screen for the microbes that break down aflatoxin. According to Purushe et al.[55], rumen bacteria, particularly Prevotella, break down coumarin, a key component of nitrogen and carbohydrate metabolism, and produce enzymes for hemicellulose breakdown. Our results showed that prevotella was more prevalent, indicating that prevotella in the rumen is involved in the coumarin breakdown process.

Our research discovered that sheep fed alfalfa hay had a lower shear force in the longissimus dorsi muscle than those fed M. albus. However, the meat quality parameters were similar among the two groups. It was found that meat from sheep fed alfalfa hay had better redness. No significant differences were found in the vastus lateralis muscle or gluteus medius. These results are similar to those obtained by Mouad et al.[26], who discovered that adding M. officinalis to kid goat diets had no effect on performance or quality but improved tenderness, protein content, and intramuscular fat in carcass characteristics and meat quality. Additionally, Jacobson et al.[61] investigated the potential harm coumarin may cause to meat quality and its potential to reduce bacterial carcass contamination during slaughter.

Several variables affect meat texture, including sample preparation, feed impact, slaughter pH, slaughter carcass appearance, slaughter temperature, and muscle glucose concentration Cordova-Torres et al.[62]. There were no differences between the measurements taken on carcass lakes between the sheep fed with M. albus and the sheep fed with alfalfa hay, and this indicates that no variations exist in the nutritional content of the meat between the treatments. Our research revealed that M. albus had superior shear force to alfalfa. Furthermore, the meat of the lucerne group, Longissimus thoracis, was found to have a higher shear force after cooking than that of Melilotus. Nonetheless, both met the standard and produced exceptional results. These results could result from fat content loss brought on by cooking. Fat deposition affects the amount of glycogen available at slaughter[38]. Additionally, intramuscular fat may also influence the tenderness of meat[63].

Based on the results of our investigation, the percentages of SFA and MUFA differ between M. albus and alfalfa hay. Still, PUFA and other FA are not different in both groups. Our findings are consistent with those of Kara[20], who found that at various phenological stages, yellow sweet clover herbages and silages have the highest level of palmitic acid (C16:0) of all SFA. According to a previous investigation[64,65], the TFA levels of common forages used in the diet of dairy cattle were found to be 15%–30% for alfalfa, 16%–20% for perennial ryegrass, 14%–20% for red clover, 16% for white clover, and 16% for maize silage. Like other legume forages such as red, white, and alfalfa, Melilotus had 17%–20% TFA concentrations for various phenological stages[66,67]. According to Kara et al.[20], Melilotus silages and herbages have the highest MUFA content, with oleic acid percentages ranging from 4%–6%. Plant growth influences the increase in medium-chain fatty acids, while lipid peroxidation decreases unsaturated fatty acids.

Coumarin, found in M. albus, is important because it helps with health issues like slowing growth, fighting disease, absorbing proteins, making enzymes, and improving BWG, ADG, and FCR. It also boosts carcass weight through a higher FBW. Additionally, it favorably impacts muscle tissue, possibly due to lower oxidative stress and improved mitochondrial function. It enhances the quality of meat and muscle fatty acids.

-

The study investigated the effects of introducing M. albus to the diet of Hu sheep, focusing on carcass characteristics, meat quality, and growth performance. The results show that M. albus has no significant impact on meat quality or carcass performance parameters. Additionally, it does perform well in critical areas such as intramuscular fat, protein content, and tenderness. It promotes the development of rumen microbes and the stability of the sheep's rumen environment. Including sweet clover in the diet lowers feeding expenses. As a result, breeders may consider M. albus a possible substitute to ensure their animals have a balanced diet and reduce fattening costs.

National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1300302), National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A20216), The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (lzujbky-2022-ct04).

-

All procedures were reviewed and preapproved by the Animal Welfare and Ethics Committee of Nanjing Agricultural University, which has approved the use of animals. Identification number: NJAU.No20230215N11, approval date: 17/ 02/ 2023. The research followed the 'replacement, reduction, and refinement' principles to minimize harm to animals. This article provides details on the housing conditions, care, and pain management for the animals, ensuring that the impact on the animals was minimized during the experiment.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: writing – original draft: Kamal M; writing – review & editing: Kamal M, Gao J, Cheng Y; methodology: Kamal M, Gao Y, Gao J, Li N, Zhao X, Cheng L; conceptualization, visualization: Kamal M, Gao Y; formal analysis: Kamal M, Cao Y, Li N, Zhang J; validation: Gao J, Zhao X, Cheng L, Zhang J, Cheng Y; software: Cao Y; funding acquisition: Cheng Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets presented in this study can be found in the BioProject - NCBI repository, accession number PRJNA1117873.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Mahmoud Kamal, Yaxiong Cao

- Supplementary Table S1 Effects of feeding M. albus on rumen papillae and papillary tissue morphology of Hu sheep.

- Supplementary Table S2 Effects of feeding M. albus on rumen fermentation parameters of Hu sheep.

- Supplementary Table S3 Effects of feeding M. albus on the quality of Lake Mutton.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Kamal M, Cao Y, Gao J, Li N, Zhao X, et al. 2025. Effects of feeding Melilotus albus on growth performance, carcass traits, and meat quality of Hu sheep. Animal Advances 2: e010 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0008

Effects of feeding Melilotus albus on growth performance, carcass traits, and meat quality of Hu sheep

- Received: 30 October 2024

- Revised: 04 January 2025

- Accepted: 05 February 2025

- Published online: 24 April 2025

Abstract: This investigation sought to evaluate the effects of Melilotus albus (M. albus) instead of alfalfa hay on Hu sheep's growth performance, carcass traits, and physiological parameters. Twenty Hu sheep were randomly distributed into two dietary trials (n = 10) and fed a basal diet ad libitum for 80 d. One group was given a diet containing M. albus, while the other was given the basal diet, which involved alfalfa hay. According to the study, there were no significant differences in FBW, BWG, F/G, nutrition effectiveness, digestible energy, or ruminal papillae growth between animals fed alfalfa hay and M. albus. The research found no significant differences in pH, microbial protein, acetate, propionate, valerate, and acetate/propionate among treatments but significantly lower NH3-N, total volatile fatty acid, butyrate, and lactate levels in alfalfa hay animals. Also, the study revealed that animals fed M. albus had higher shear force in the longissimus dorsi but no significant differences in meat quality parameters like pH, water-holding capacity, brightness, and yellowness. Dynamic changes in microbial communities were discovered. Feeding M. albus affects the β diversity index but not the α diversity index. The LEfSe analysis revealed higher Firmicutes and Proteobacteria abundances in M. albus compared to alfalfa, as well as higher genus abundances of Ruminococcus, Rikenellaceae_RC9_gut, Christensenellaceae_R-7_group, and uncultured Marinifilaceae. Although melilotus clover has not affected the growth performance of Hu sheep compared with alfalfa, it is beneficial in improving the fatty acid composition of Hu sheep muscle. It affects the flavour and nutritional value of meat to a certain extent. Furthermore, the price of melilotus is low and can be supplied in large quantities to be used as an alternative to alfalfa.

-

Key words:

- Melilotus albus /

- Productive performance /

- Carcass traits /

- Fatty acids /

- Sheep