-

Ovarian granulosa cells (GCs), as one of the important somatic cells of the follicle, provide a special microenvironment for oocyte development and maturation by releasing hormones and various factors[1]. Dysregulation of GC metabolism and apoptosis can negatively affect oocyte quality and embryo formation. For example, under acute heat stress in vitro, BGCs may show decreased cell viability, increased oxidative stress, and apoptosis rates[2]. Oxidative stress not only affects oogenesis, follicular development, maturation, and rupture but also affects the quality of oocytes and embryos as well as the development of early embryos. H2O2-induced apoptosis of rat ovarian GCs is associated with cellular oxidative stress levels[3]. Studies have shown that GC death is the main cause of follicular atresia and is closely regulated by apoptosis[4,5]. Therefore, GCs are essential for follicular formation, and changes in GC apoptosis and oxidation balance may alter the fate of GCs in follicular atresia.

Chemerin, as a chemotactic adipokine, mainly acts on chemokine-like receptor-1 (CMKLR1) through autocrine or paracrine pathways to achieve its biological function[6]. Chemerin is mainly involved in the regulation of the immune system, adipogenesis, and energy metabolism[7]. Moreover, chemerin is expressed not only in the white adipose, brown adipose, liver, kidney, and pancreas but also in the pituitary, placenta, ovary, and testis[8,9]. It has been suggested that chemerin may affect ovarian steroid production in pigs by modulating the activity of steroid-producing enzymes[10]. Patients with polycystic ovary syndrome have shown increased serum chemerin concentrations[11]. In rats, chemerin removes the stimulatory effect of follicle-stimulating hormone on the secretion of progesterone and estradiol in pre-antral follicles and GCs[12]. In BGCs, chemerin also inhibits the expression of cholesterol transporter, STAR, P450 aromatase, and cholesterol de novo synthesis[13]. These data suggest a potential role of chemerin in reproduction.

In addition, Xie et al. have demonstrated that chemerin can induce autophagy in skeletal muscle cells by increasing ROS levels and reducing mitochondrial membrane potential, as well as regulating mitochondrial remodeling[14]. Consistent with this, Maraldi et al. showed that increased ROS content accelerated oocyte aging and decreased its antioxidant capacity[15]. ROS produces excessive activation of the ERK1/2 pathway and induces mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress[16]. It has been shown that high levels of visfatin activate the ERK1/2 pathway and promote malignant transformation of the endometrium[17]. Although there is evidence linking chemerin to reproduction, its role in oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in BGCs has not been studied intensively. In this study, we investigated the effect and mechanism of chemerin on H2O2-induced apoptosis of BGCs.

-

Recombinant mouse chemerin was purchased from R&D Systems (2325-CM-025, MN, USA). Antibodies against ERK1/2 (#4695), p-ERK1/2 (#4370), and α-tubulin (#2125) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, USA); antibodies Bax (#N-20) and Bcl-2 (#H-62) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (CA, USA); anti-chemerin (#bs-60386) was from Bioworld Technology (MN, USA); anti-Cleaved-caspase-3 (#bs-0081R) was from Bioss (Beijing, China); and anti-FSHR (BC118548) was purchased from Proteintech (Chicago, USA).

Cell culture and treatment

-

The ovaries were collected from Holstein cows from local slaughterhouses, packed in an aseptic thermos containing 32−35 °C phosphate buffer saline (PBS), and transported to the laboratory within 4 h for further processing[18]. The ovarian tissues were soaked in 75% alcohol for 30 s, then washed twice in a sterile beaker containing PBS buffer (including double antibody) for 30 s each time. The follicle was gently punctured with the needle of a disposable syringe (5−8 mm), the follicle fluid was absorbed and placed in a 15 mL centrifuge tube, centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 min, and washed twice with PBS. BGCs were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium / F12 supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum and antibiotics (100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The medium was changed every two days, and the cell density was adjusted according to the experimental requirements. The cells were divided into three groups: the control group, the H2O2-treatment group (600 μM H2O2), and the co-treatment group (600 μM H2O2 + 0.1 μg/mL chemerin).

Cell viability assay

-

The cell viability of BGCs was detected by the CCK-8 assay (Nanjing Jian Cheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China, G021-1-1). The BGCs were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/mL into 96-well plates and treated with different concentrations of H2O2 (0, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1,000 μM) for 2 h. Ten microliters of CCK-8 solutions were added into each well (ensuring no bubbles were produced), and cells were incubated for 4 h in a 5% CO2 incubator. The absorbance was measured with a microplate reader at 450 nm.

siRNA gene silencing

-

At approximately 70% confluence, BGCs were transfected with chemerin-specific siRNA and negative control siRNA (NC, Gene Pharma Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) respectively, using lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) referring to the instruction of the manufacturer. The concentration of siRNA used for transfection was 20 μM. At 48 and 72 h after transfection, RNA and protein were extracted in sequence for subsequent analysis. The sequences of siRNAs are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Sequences of chemerin and negative control (NC) siRNAs.

Gene Forward (5′-3′) Reverse (5′-3′) si-NC UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT ACGUGACACGUUCGGACAATT si-Chemeirn-1 GGGAAGAUAUCCUGCUUUATT UAAAGCAGGAUAUCUUCCCTT si-Chemerin-2 GCCACAGGAGCUUUACCAATT UUGGUAAAGCUCCUGUGGCTT si-Chemerin-3 UCGUCAUGAUCACGUGCAATT UUGCACGUGAUCAUGACGATT ROS detection

-

The BGCs were cultured at a density of 2.5 × 105 cells/mL into 35 mm plates, and ROS production was assessed with the DCFH-DA (Nanjing Jian Cheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China, E004-1-1). After treatment, cells were incubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min in a 5% CO2 incubator, washed with PBS three times, and fluorescence images were observed under confocal laser-scanning microscopy. The fluorescence intensities of cells were analyzed by the Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software.

Flow cytometry detection of apoptosis

-

Apoptosis of BGCs was detected with the annexin V/PI double-staining apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences, USA, 559763). The BGCs were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 into 6-well plates and treated accordingly. Then, the cells were collected into a centrifuge tube, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in a binding buffer. Subsequently, 5 µL of annexin V solution was added, and the cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Thereafter, 5 µL of propyl iodide solution was added, followed by 400 µL of PBS, and the samples were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA).

Determination of antioxidant parameters

-

The BGCs were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates and then subjected to appropriate treatments. The activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD, A001-3-2), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-px, A005-1-2), and the levels of malondialdehyde (MDA, A003-2-2) were measured using the relevant detection kits (manufactured by Nanjing Jian Cheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Immunofluorescence staining

-

The cells were plated on glass cell sheets in a 24-well plate until they reached 80% confluence. Subsequently, the cells were washed three times with preheated phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min, and then permeabilized with a 0.5% Triton X-100 solution for 20 min. Following permeabilization, the cells were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 1 h and incubated overnight at 4 °C with a follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) antibody with a dilution of 1:500. Following three washes with PBS, the cells were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The samples were then co-stained with Hoechst 33342 for 10 min, and washed three times with PBS. Finally, the samples were mounted on glass slides and visualized using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM 700 META).

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

-

Total RNA was extracted from BGCs using Trizol reagent, following the manufacturer's guidelines. The RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan), according to the provided instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted using the Applied Biosystems 7500 HT Sequence Detection System. PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s, and a final melt curve analysis at 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 60 s, and 95 °C for 10 s. The relative expression levels of target genes were determined using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method. Primer sequences are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Primer sequences for Quantitative real-time PCR.

Gene Forward (5′-3′) Reverse (5′-3′) Chemerin GGAGGAGTTCCACAAGCATC CTTGAACTCCAGCCTCACAA CMKLR-1 GGCGGTCTACAGCGTCATCT CGCCAGGTTGAGGAACCAGA Bax CCAGCAAACTGGTGCTCAAGG AGCCGCTCTCGAAGGAAGTC Bcl-2 AGCATCGCCCTGTGGATGAC CAGCCTCCGTTGTCCTGGAT Caspase-3 CTGAGGGTCAGCTCCTAGCG GCTGCAGCTCTGCTGGACT β-actin CATGCCATCCTCCGTCTGGA CTCTCGGCTGTGGTGGTGAA Western blot analysis

-

The treated cell samples were collected in RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, P0013B), combined with phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, ST506), denatured by heating at 100 °C for 10 min. Equal amounts of protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes by an electrophoretic ally. The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk for 1 h, followed by incubation at 4 °C overnight with goat monoclonal anti-chemerin (1:500), Bax (1:500), Bcl-2 (1:500), Cleaved-caspase-3 (1:500), p-ERK1/2 (1:1,000), ERK1/2 (1:1,000), and internal reference α-tubulin (1:3000) antibodies. After washing three times in tris-buffered saline with tween, the membranes were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Next, the membranes were washed three additional times, treated with Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP substrate, and the protein was visualized using a chemiluminescence gel imaging system (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Protein expression levels were quantified using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

-

All experimental data were expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan's multiple comparisons test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All experiments were repeated at least three times, with three technical replicates per trial.

-

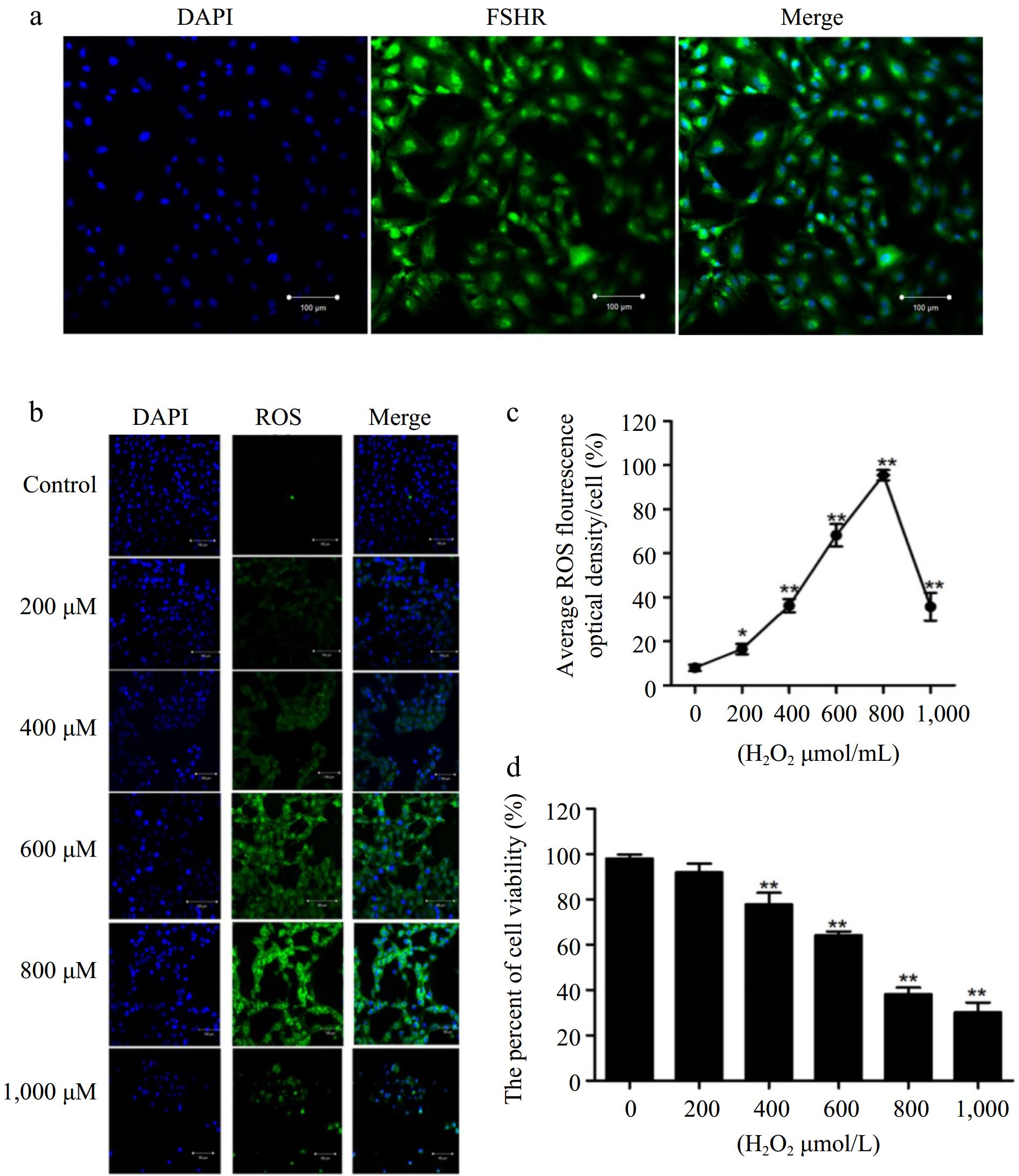

Previous studies have demonstrated that FSHR is exclusively expressed in granulosa cells (GCs) and testicular Sertoli cells[19]. As shown in Fig. 1a, the positive staining of the GCs marker FSHR was found in the purified cells. To establish an oxidative damage model of BGCs, cells were treated with H2O2 (ranging from 0 to 1,000 μM) for 2 h. As shown in Fig. 1b, c, DCFH-DA staining revealed that H2O2 significantly increased ROS levels in a concentration-dependent manner. Notably, ROS levels were significantly elevated in cells treated with 600 μM H2O2. Next, CCK-8 assay results indicated that cell viability was remarkably reduced in a concentration-dependent manner. At 600 μM H2O2, cell viability was reduced, the cell survival rate was approximately 60%, and the cell morphology remained intact under the microscope (Fig. 1d). Therefore, H2O2 at a concentration of 600 μM, was utilized for subsequent studies, as it effectively induced oxidative damage while maintaining physiological conditions.

Figure 1.

Establishment of oxidative stress model in BGCs. (a) The BGCs were cultured in vitro and identified by immunofluorescence against FSHR. (b) Immunofluorescence labelling of ROS in the BGCs. (c) Quantification of intracellular ROS levels. (d) Cell viability of BGCs after exposure to H2O2 (0 to 1,000 μM) for 2 h. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. * p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.001. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Chemerin promotes oxidative stress of BGCs

-

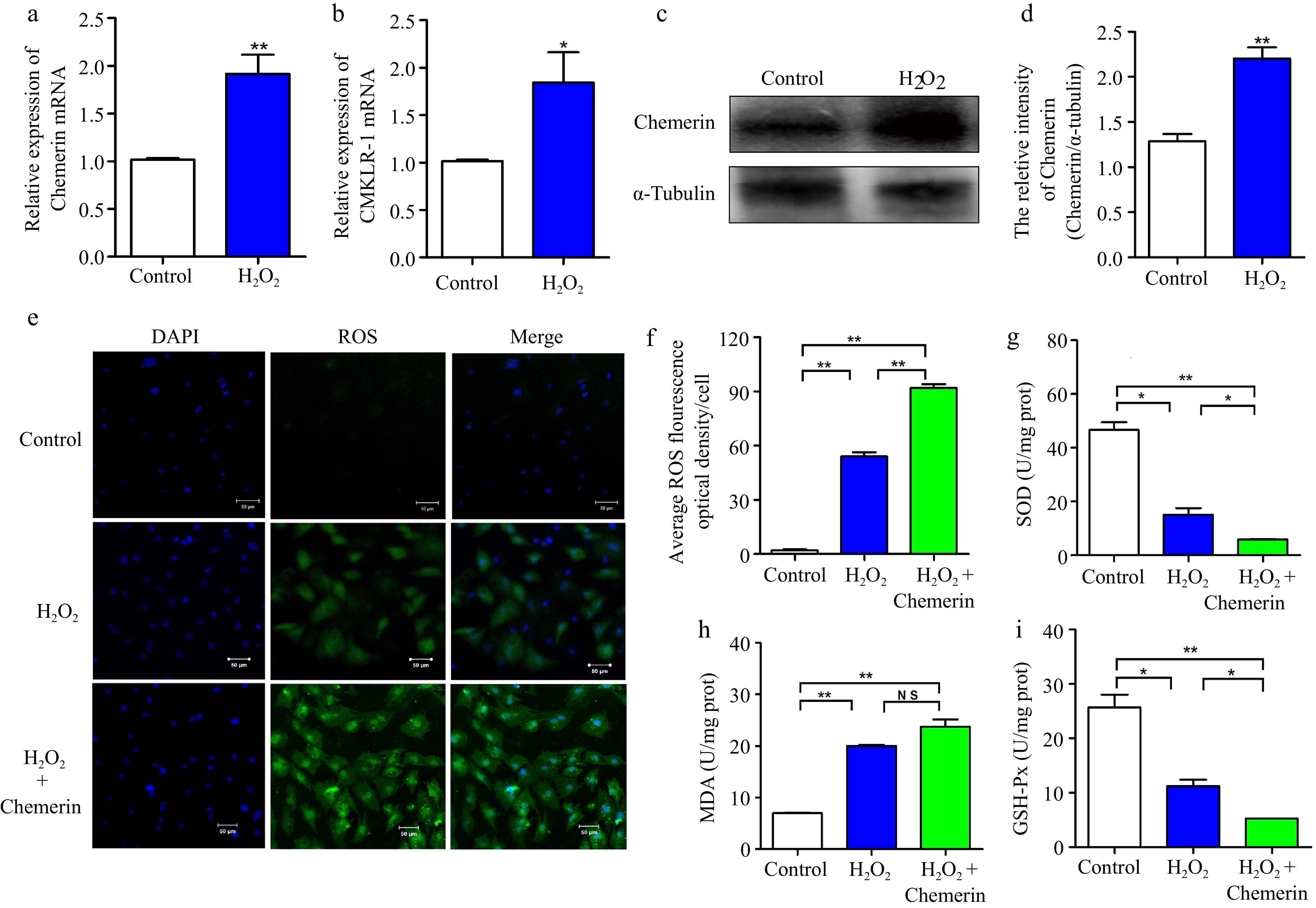

Next, we investigated the effect of chemerin on oxidative stress in BGCs. RT-qPCR results showed that H2O2 significantly increased the expression of chemerin and CMKLR-1 genes (Fig. 2a, b). Additionally, the protein level of chemerin was significantly elevated following H2O2 treatment (Fig. 2c, d). To evaluate the impact of chemerin on ROS levels, cells were co-treated with H2O2 and chemerin. As depicted in Fig. 2e, f, H2O2 remarkably promoted ROS production, and co-treatment with H2O2 and chemerin further enhanced ROS content compared to H2O2 alone. In addition, H2O2 treatment decreased the activation of SOD and GSH-px and increased the level of MDA in comparison to the control group, a trend that was further enhanced by chemerin (Fig. 2g−i). These results indicate that H2O2 induces cellular oxidative stress, and co-treatment with chemerin and H2O2 further intensifies ROS generation and oxidative stress in BGCs.

Figure 2.

Chemerin promotes oxidative stress in BGCs. (a), (b) Detection mRNA expressions of chemerin and CMKLR-1 after H2O2 treatment in BGCs by RT-qPCR. (c), (d) Detection protein expression of chemerin in BGCs by western blotting. α-Tubulin was used as the internal control for protein level normalization. (e) DCFH-DA assay for detection ROS content in BGCs exposed to H2O2 with or without chemerin. (f) Relative fluorescence intensity of ROS. (g)−(i) Effect of chemerin on the antioxidant enzymes in H2O2-induced BGCs. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. * p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.001, ns denotes not significant. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Chemerin promotes apoptosis of BGCs

-

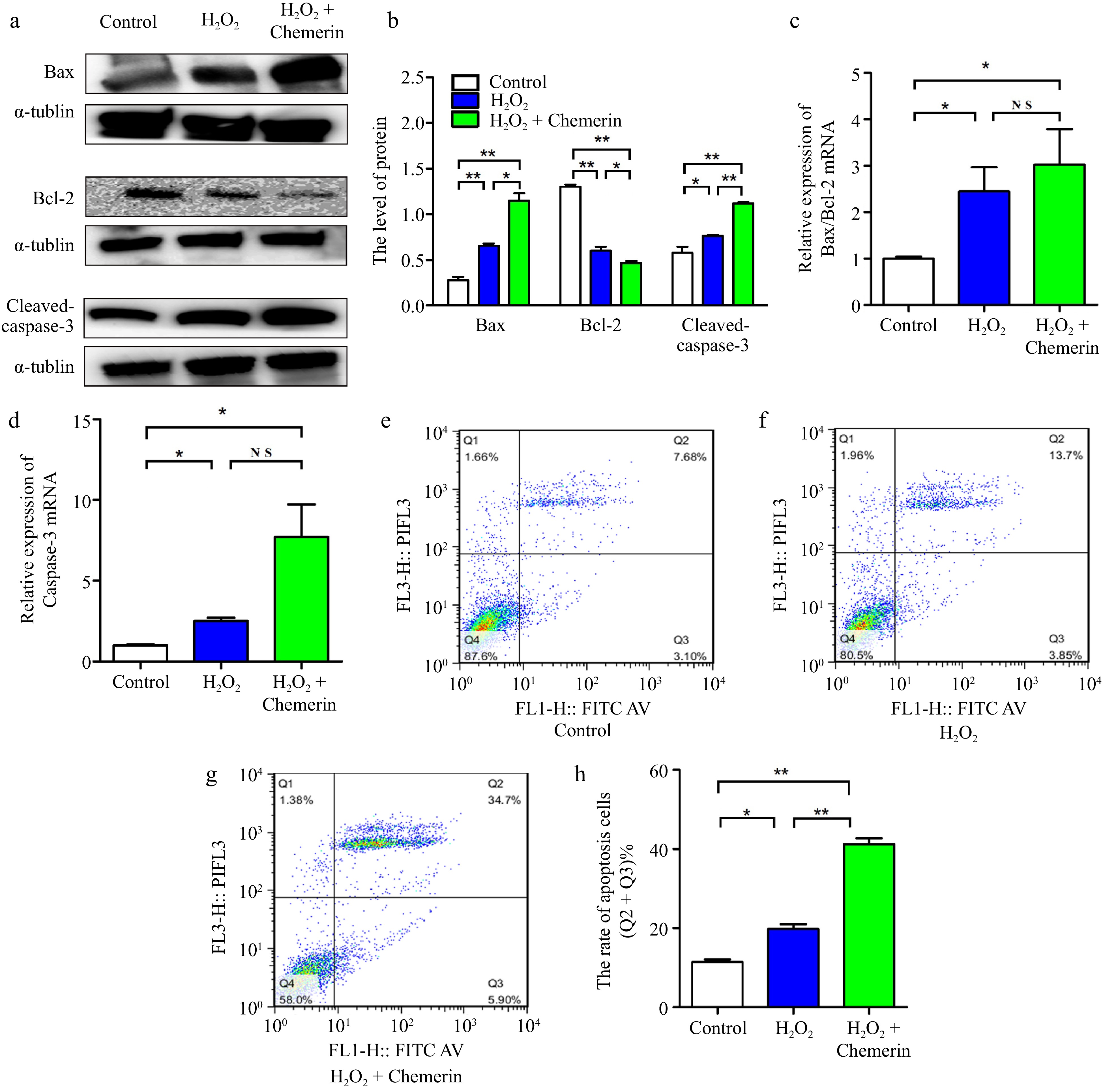

It has been shown that elevated levels of oxidative stress induce apoptosis[20]. As depicted in Fig. 3a, b, H2O2 exposure significantly increased the levels of pro-apoptotic proteins (Bax and Cleaved-caspase-3) and decreased the expression of the anti-apoptotic protein (Bcl-2) in comparison to the control group, and chemerin treatment enhanced the apoptosis. Consistently, compared to the control, the combination of H2O2 and chemerin remarkably increased the mRNA expression of Caspase-3 and Bax/Bcl-2 (Fig. 3c, d). To further assess the impact of chemerin on apoptosis, flow cytometry was employed to measure the apoptosis rate. As depicted in Fig. 3e−h, compared with the control, H2O2 treatment significantly increased the apoptosis rate (19.5%), and the apoptosis rate was further increased in the H2O2 and chemerin co-treated group (42%). In conclusion, our findings suggested that chemerin enhanced H2O2-induced apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Chemerin promotes apoptosis in BGCs. (a), (b) Cells were treated with H2O2, chemerin plus H2O2. Western blotting analysis of apoptosis-related proteins (Bax, Bcl-2, and Cleaved-caspase-3) expression and relative quantification in BGCs. (c), (d) RT-qPCR analysis of the relative mRNA expression levels of Bcl-2, Bax, and Caspase-3. (e)−(h) Flow cytometry analysis of cell apoptosis rate. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. * p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.001, ns denotes not significant.

Chemerin gene silencing inhibits apoptosis in BGCs

-

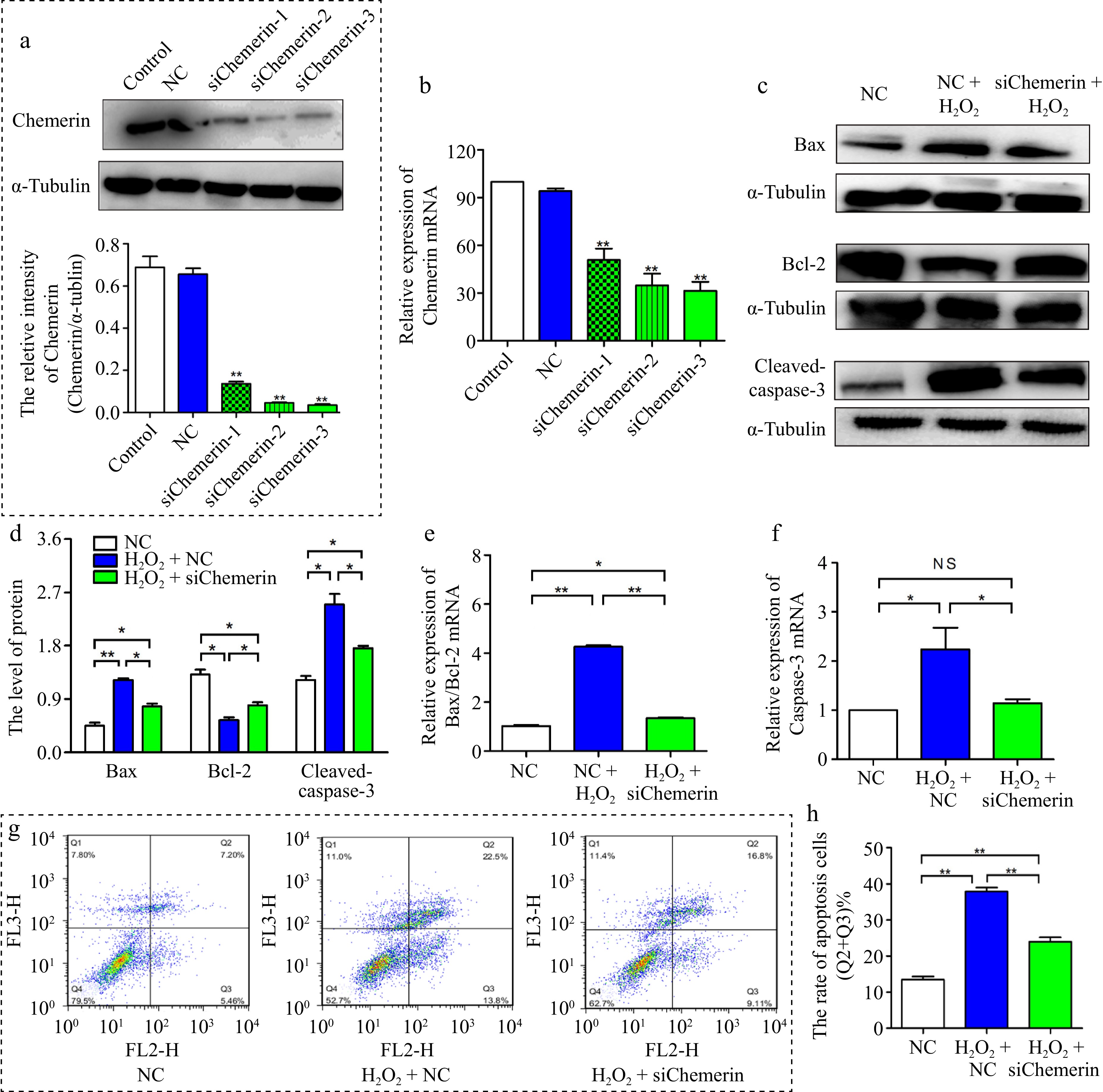

To further evaluate the effect of chemerin on apoptosis, we designed three small interfering RNAs of chemerin, and the interference efficiencies of si-chemerin-3 were more than 70%, so si-chemerin-3 was selected for subsequent study (Fig. 4a, b). As shown in Fig. 4c, d, compared with the H2O2 plus NC treatment, the pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and Cleaved-caspase-3 were down-regulated, and Bcl-2 was up-regulated under the si-chemerin plus H2O2 treatment. In agreement, si-chemerin plus H2O2 treatment remarkably decreased the mRNA expression of Bax/Bcl-2 and Caspase-3 (Fig. 4e, f). Flow cytometry results showed that si-chemerin significantly down-regulated H2O2-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4g, h). These results showed that chemerin gene silencing relieved the H2O2-induced apoptosis in BGCs.

Figure 4.

Interfering chemerin inhibited oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in BGCs. (a), (b) BGCs were treated with si-NC, si-chemerin-1, si-chemerin-2, and si-chemerin-3. The interference efficiency of chemerin was detected at 72 and 48 h by Western blotting and RT-qPCR. (c), (d) Western blotting analysis of Bax, Bcl-2, and Cleaved-caspase-3 proteins expression in BGCs treated with H2O2 plus si-NC or si-chemerin-3. (e), (f) RT-qPCR analysis the levels of apoptosis-related genes (Bax, Bcl-2, and Caspase-3). (g), (h) Flow cytometry analysis the apoptosis rate in BGCs. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 3. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.001, ns denotes not significant.

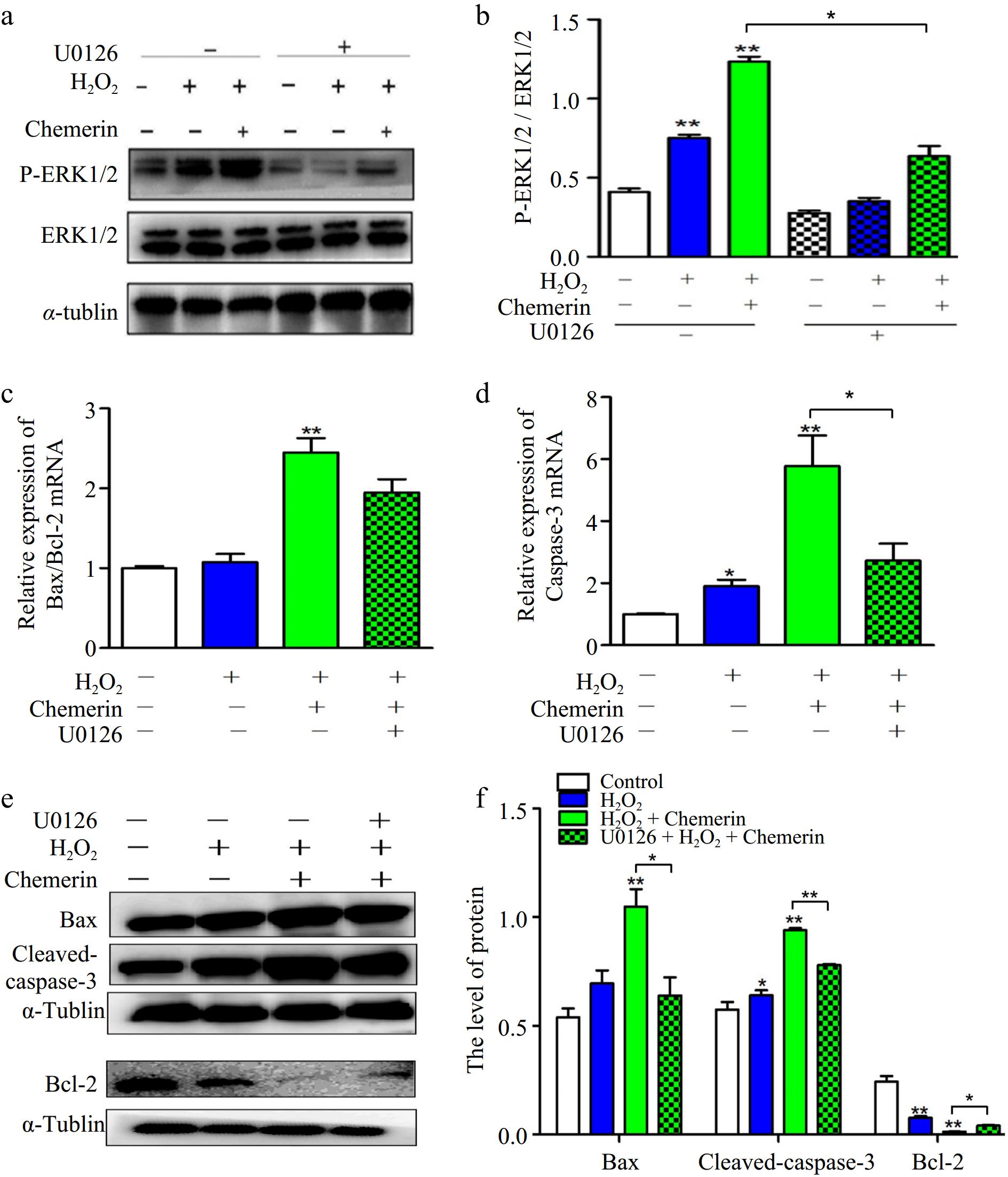

Chemerin regulates apoptosis via ERK1/2 pathway in BGCs

-

ERK1/2 signaling is essential in mediating apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, chemerin promoted the level of p-ERK1/2 in contrast to H2O2 alone. To elucidate the role of ERK1/2 in chemerin-induced apoptosis, U0126, a selective ERK1/2 inhibitor, was chosen to block ERK1/2 signaling activity. The results demonstrated that U0126 pretreatment significantly inhibited ERK1/2 activation induced by chemerin (Fig. 5a, b). In addition, supplementation with U0126 decreased the mRNA expression of Caspase-3 and Bax/Bcl-2 ratio compared to H2O2 plus chemerin treatment (Fig. 5c, d). Consistently, increased Bax and Caspase-3 expression levels, along with reduced Bcl-2 expression levels, were observed in the H2O2 plus chemerin-treated group, whereas U0126 treatment reversed these protein expression patterns (Fig. 5e, f). These results suggest that the ERK1/2 pathway is involved in chemerin-induced apoptosis.

Figure 5.

Chemerin promoted oxidative stress-induced apoptosis via ERK1/2 pathway in BGCs. (a), (b) BGCs were treated with H2O2, U0126 plus H2O2, and H2O2 in combination with chemerin and U0126. Protein expressions of p-ERK1/2 and ERK1/2 were measured by Western blotting. (c), (d) The mRNA expressions of Bax/Bcl-2 and Caspase-3 were tested in BGCs by RT-qPCR. (e), (f) Western blotting analysis the protein expressions of Bax, Bcl-2, and Cleaved-caspase-3 and relative quantification in BGCs. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3. *p < 0.05, and **p < 0.001.

-

The growth, development, and quantity of GCs directly affect the development, ovulation, fertilization, and embryo implantation of oocytes. It has been confirmed that oxidative stress damages the physiological state of GCs, leading to follicular developmental disorders[21]. Cai et al. found that H2O2 treatment significantly increased the levels of ROS and MDA, and decreased the activation of SOD in GCs[22]. SOD and GSH-px are recognized as oxidative stress markers[23]. MDA, a lipid peroxidation product, is used as an indicator reflecting cell oxidative damage. Consistently, our study found that H2O2 promotes the levels of ROS and MDA, inhibits the contents of SOD and GSH-PX, and inhibits cell viability in BGCs. Chemerin is an adipokine, and it has been reported that chemerin induces mitochondrial ROS generation and autophagy in C2C12 cells[14]. Here, we found that H2O2 promoted the expression of chemerin and CMKLR-1, and chemerin treatment further exacerbated H2O2-induced oxidative stress in BGCs. This indicates that chemerin plays an important role in oxidative stress-induced granulosa cell damage.

Excess ROS leads to oxidative stress, causing damage to organelle proteins, lipids, enzyme activity, and biofilms, ultimately activating the apoptotic pathway[24]. Oxidative stress is known to be an important factor contributing to the apoptosis of GCs[25]. The balance of apoptosis-related proteins (Bax and Bcl-2) expression is the key to cell survival. An imbalance in the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio can render tumor cells more resistant to cell death stimuli[26]. Caspase-3, a common caspase, plays a crucial role in apoptotic processes[27]. Activation of Caspase-3 can be triggered by up-regulation of Bax, leading to cell apoptosis[28].In our study, we observed that H2O2 treatment promoted apoptosis in BGCs, as evidenced by increased Bax and Caspase-3 levels and decreased Bcl-2 levels. In a rat model, dihydrotestosterone treatment significantly increased the expression of chemerin and its receptor CMKLR-1, which in turn promoted GCs apoptosis by increasing active Caspase-3 content and DNA fragmentation[29]. Consistent with this, we found that chemerin increased H2O2-induced apoptosis in BGCs, and interference with chemerin reversed the expression of apoptosis-related factors.

Oxidative stress can activate the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, and ERK, a subunit of MAPK, plays an important role in MAPK signaling[30]. Previous studies have reported that MAPK/ERK1/2 pathways act as signal transducers and regulate cell growth, survival, and apoptosis. Activation of the MAPK pathway has been shown to induce oxidative stress and apoptosis in cells[31]. In this study, we discovered that co-treatment with H2O2 and chemerin resulted in increased phosphorylation of ERK when compared to H2O2 alone. Geng et al. have revealed that oxidative stress might induce apoptosis via regulation of the ERK1/2 pathways, and supplementation with U0126 or PD98059 could alleviate oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in cells[32]. In agreement with the report, our result proved that chemerin treatment remarkably increased H2O2-induced apoptosis in BGCs by promoting the phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Additionally, when U0126 was added to inhibit the activation of the ERK1/2 pathway, the expression of Bax and Caspase-3 decreased, while Bcl-2 expression increased in BGCs under oxidative stress conditions. Interestingly, the study by Wang et al. suggested that the activation of ERK1/2 may also hinder apoptosis by reducing Bad expression and increasing Bcl-2 levels, which could be attributed to different cellular mechanisms[33].

-

In summary, the results demonstrated that chemerin promoted H2O2-induced apoptosis partly through regulating the ERK1/2 pathway. These findings provide useful evidence for the role of chemerin in apoptosis-induced GCs damage and further provide a scientific basis for the treatment of follicular dysplasia during production.

-

The ovaries used in the experiment were collected from local slaughterhouses (Nanjing Qiling Meat Industry Co., Ltd.). No ethics review application is required, as the experimental bovine ovaries are slaughterhouse by-products obtained through standardized procedures, and their use involves no additional animal harm or welfare issues.

We appreciate the experimental equipment and technical support provided by the Experimental Center of the School of Animal Science and Technology, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32472963).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception, design & research: Liu Y; sample collection, molecular studies: Duan YP; data analysis, draft manuscript preparation: Li H. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

-

The data used in this study were provided by the research group and collected from previously published sources.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yuan Liu, Yin-ping Duan

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu Y, Duan YP, Li HX. 2025. Chemerin promotes H2O2-induced apoptosis via regulation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in bovine ovarian granulosa cells. Animal Advances 2: e024 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0020

Chemerin promotes H2O2-induced apoptosis via regulation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in bovine ovarian granulosa cells

- Received: 19 February 2025

- Revised: 02 April 2025

- Accepted: 21 April 2025

- Published online: 02 September 2025

Abstract: Extensive evidence indicates that oxidative stress plays an important role in animal reproduction. Chemerin, an adipose hormone found in tissues such as the pituitary gland, placenta, and ovary, plays a role in regulating energy metabolism and reproductive functions. The specific mechanism by which it regulates reproduction, however, remains unclear. This study aimed to determine the effects of chemerin on hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)-induced apoptosis in bovine ovarian granulosa cells (BGCs). The results showed that H2O2 treatment significantly promoted oxidative stress and apoptosis, which were further enhanced by chemerin. Silencing chemerin reverses the expression of apoptosis-related genes and proteins (Bax, Bcl-2, and Caspase-3), and reduces the apoptosis rate, suggesting that chemerin increases H2O2-induced apoptosis. In addition, chemerin enhanced the activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinases (ERK) 1/2, which was reversed by U0126 co-treatment, and accompanied by the increases of apoptosis, indicating that chemerin promoted H2O2-induced apoptosis partially through the ERK1/2 pathway. In summary, these results suggest that chemerin may enhance H2O2-induced BGCs apoptosis by activating the ERK1/2 pathway, providing a theoretical basis for exploring the regulatory relationship between fat-secreted factors and animal reproductive performance.

-

Key words:

- Chemerin /

- Oxidative stress /

- Apoptosis /

- Bovine ovarian granulosa cells /

- ERK1/2